World Population Growth: A Once and Future Global Concern

Abstract

1. History

- The first UN Conference on the Environment in Stockholm in 1972 [7];

- The first UN Conference on Population in Bucharest in 1974 [8].

- The United Nations Environmental Program, UNEP, based in Nairobi;

- The United Nations Fund for Population Activities, UNFPA, based in New York.

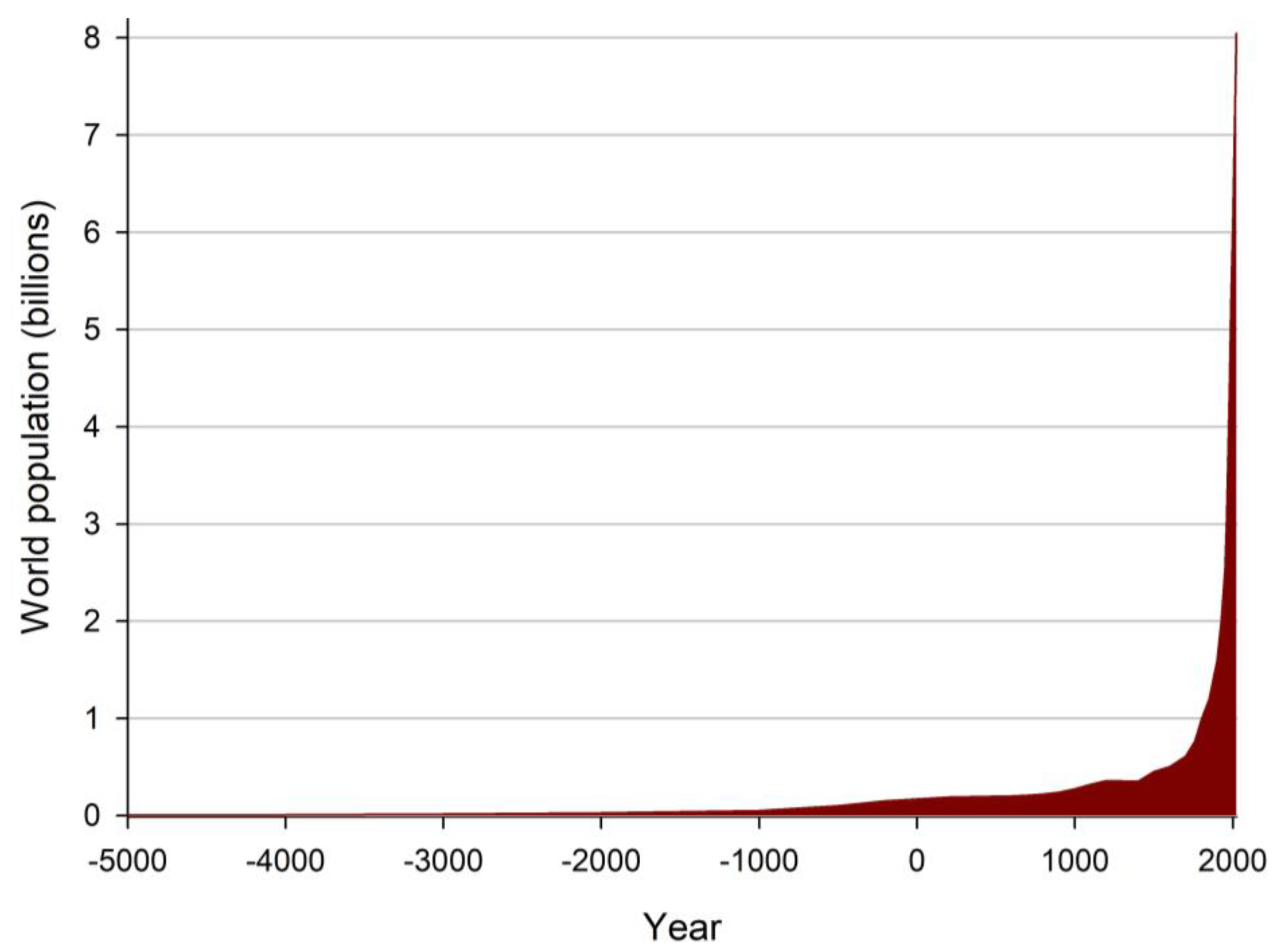

2. The Situation in 2023

3. The Case of Africa

4. How Many People Can the World Support?

5. The Opposition against Active Population Policies

- Development assistance executives, including from civil society organizations, who wanted to distance themselves from the Chinese type “authoritarian methods of birth control” and who felt obliged to avoid measures that could be seen as patronizing administrations of developing countries [55].

- Technology optimists saying that humanity will, as always, find solutions to new challenges [56]. According to them, the planet can easily house 10–12 billion people if not many more.

- Some women´s organizations who felt that “birth control” programs constituted neo-colonialist efforts to tell women in developing countries how to organize their lives [57].

- Evangelicals and similar radical Christian groups who, “in the Name of God”, were actively fighting against abortion and other family planning measures. These groups had a very strong influence on Republican Presidents of the USA, from Ronald Reagan, through George Bush and George W. Bush to Donald Trump. These Republican Presidents stopped American financial contributions to the UNFPA [58,59].

- Islamic States and other states with a Muslim population became ever more active opponents of family planning as representing cultural Westernization. These governments did not want population policies to encourage the empowerment of women, including her right to decide over her own body [60].

- The Vatican and the Catholic Church affirmed their opposition to modern contraception in the 1968 papal encyclical Humanae Vitae. To retreat from this position would require a retreat from the doctrine of papal infallibility [61]. The Vatican has used its considerable influence within the United Nations and elsewhere not only to oppose contraception and abortion care but also to undermine the idea that population growth may have negative consequences, thereby justifying family planning promotion [62].

6. The European Population Experience

European Demography Crisis?

7. The Challenges of Over-Population and Possible Solutions

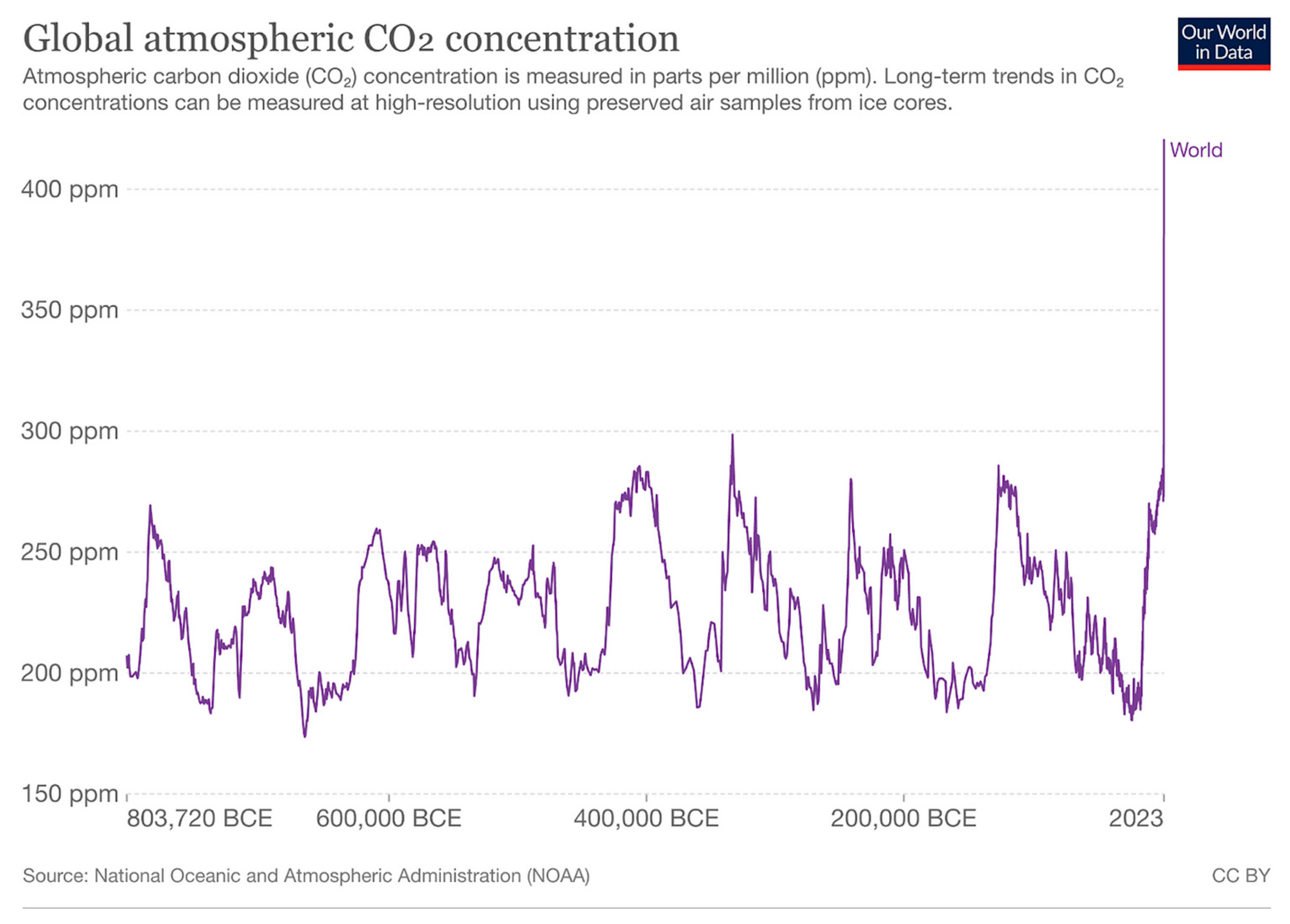

Challenges

- The Global Challenge: For the sake of climate stabilization, an active population policy needs to be re-introduced, enshrining voluntary, client-focused and rights-based family planning services as central to sustainable development. There are good role models. The successful programs of the 1970s and 1980s are well documented [78]. Without these programs, the world population would have been close to 9 billion today! The UNFPA needs a larger budget [77]. Many bilateral ODA donors would need new priorities and various civil society donors should follow the example of the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation in supporting voluntary family planning provision [79].

- The African Challenge: Christian and Muslim leaders in Africa must be persuaded that a population policy is necessary. This will be difficult but has been done elsewhere. If unconvinced about the benefits for economic development, they may be motivated by increasingly evident risks of extreme food and water scarcity.

- The National Challenge: The chances for a prosperous society are much better if population growth is under control. South Korea´s and Europe´s sensational development in the past 50 years stands as an example. The argument sometimes used by certain authoritarian leaders (see above), “Our population has to grow, in order to strengthen the power of our nation”, must be rejected.

- The Equality Challenge: More just and equal conditions both within countries and between poorer and richer countries can be achieved only if more gender equality is also introduced in poorer countries. Education of girls through all three school levels is necessary. Dropping out from school at an early stage must be avoided. Child marriage must be stopped.

- The Family Challenge: Children should not be a burden on a family but for poorer families the feeding of too many hungry mouths becomes impossible. Parents (particularly fathers) must realize that large families no longer represent a “guarantee for the future” when infant mortality is now low and employment opportunities require investing in a child’s education.

- The Child Challenge: Every child in the world should have the right to be really wanted and welcome—to be loved by parents and family. Every child should also have enough physical resources, at both the family and society level, for a chance to have a reasonably good life.

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Malthus, T. An Essay on the Principle of Population as It Affects the Future Improvement of Society, 1st ed.; J. Johnson in St Paul’s Church-Yard: London, UK, 1798. [Google Scholar]

- Carson, R. Silent Spring; Houghton Mifflin Company: Boston, MA, USA, 1962; ISBN 9780618249060. [Google Scholar]

- Borgström, G. The Hungry Planet: The Modern World at the Edge of Famine; Macmillan: New York, NY, USA, 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Ehrlich, P.; Ehrlich, A. The Population Bomb; Ballentine Books: New York, NY, USA, 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Meadows, D.H.; Meadows, D.L.; Randers, J.; Behrens, W.W. The Limits to Growth: A Report for the Club of Rome’s Project on the Predicament of Mankind; Universe Books: New York, NY, USA, 1972; ISBN 0876631650. Available online: https://archive.org/details/limitstogrowthr00mead (accessed on 20 August 2023).

- Engfeldt, L.G. Diplomati i Förändring (Diplomacy in Transformation); Ekerlids: Stockholm, Sweden, 2019; ISBN 109188849201. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. Report of the United Nations Conference on the Human Environment. In Proceedings of the United Nations Conference on the Human Environment, Stockholm, Sweden, 5–16 June 1972; Available online: https://www.un.org/en/conferences/environment/stockholm1972 (accessed on 15 September 2023).

- United Nation. E/CONF.60/19 Report of the World Population Conference. In Proceedings of the World Population Conference, Bucharest, Romania, 19–30 August 1974; Available online: https://www.un.org/en/conferences/population/bucharest1974 (accessed on 20 August 2023).

- Wahren, C. Loggbok från Aniara (Logbook from Aniara); Recito: Stockholm, Sweden, 2019; ISBN 9789177654209. Available online: https://www.bokus.com/bok/9789177654209/loggbok-fran-aniara-skisser-till-ett-tidsdokument/ (accessed on 20 August 2023).

- Masih, M.; Barpanda, S.; Wynne, Z. (Eds.) Mistreatment and Coercion: Unethical Sterilization in India; Human Rights Law Network: New Delhi, India, 2018; ISBN 81-89479-94-6. Available online: https://slic.org.in/uploads/2018/10/Mistreatment-and-Coercion-Unethical-Sterilization-in-India-3.pdf (accessed on 20 August 2023).

- Mullen, A. China’s One-Child Policy: What Was It and What Impact Did It Have? South China Morning Post, 1 June 2021. Available online: https://www.scmp.com/economy/china-economy/article/3135510/chinas-one-child-policy-what-was-it-and-what-impact-did-it (accessed on 20 August 2023).

- United Nations. Report from the International Conference on Population. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Population, Mexico City, Mexico, 6–14 August 1984; Available online: https://www.unfpa.org/sites/default/files/event-pdf/ICP_mexico84_report.pdf (accessed on 20 August 2023).

- United Nations. Our Common Future: Report of the World Commission on Environment and Development (Brundtland Report). 1987. Available online: https://www.are.admin.ch/are/en/home/media/publications/sustainable-development/brundtland-report.html (accessed on 20 August 2023).

- UNFPA. Programme of Action adopted at the International Conference on Population and Development. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Population and Development, Cairo, Egypt, 5–13 September 1994; Available online: https://www.unfpa.org/sites/default/files/event-pdf/PoA_en.pdf (accessed on 20 August 2023).

- UNDESA. Sustainable Development Goals: The 17 UN Goals for 2030. United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, undated. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/goals (accessed on 20 August 2023).

- Sörlin, S. Befolkning i Fokus (Population in Focus); KTH Library: Stockholm, Sweden, 2009; Available online: https://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:kth:diva-60922 (accessed on 20 August 2023).

- Coole, D. Too many bodies? The return and disavowal of the population question. Environ. Politics 2013, 22, 195–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosling, H. Factfulness: Ten Reasons We’re Wrong about the World—And Why Things Are Better than You Think; Sceptre: Stockholm, Sweden, 2018; ISBN 9781473637467. [Google Scholar]

- Berggren, C. The One-Sided Worldview of Hans Rosling. Quillette, 16 November 2018. Available online: https://quillette.com/2018/11/16/the-one-sided-worldview-of-hans-rosling/ (accessed on 20 August 2023).

- Cardini, A. Rosling’s fallacy: Conservation, biodiversity and the anthropocentrism of Hans Rosling’s Factfulness. Ecol. Citiz. 2022, 5, 117–122. Available online: https://www.ecologicalcitizen.net/pdfs/epub-055.pdf (accessed on 20 August 2023).

- Ripple, H.; Wolf, C.; Newsome, T.; Galetti, M.; Alamgir, M.; Crist, E.; Mahmoud, M.I.; Laurance, W.F. World Scientists’ Warning to Humanity: A Second Notice. Bioscience 2017, 67, 1026–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crist, E.; Mora, C.; Engelman, R. The interaction of human population, food production, and biodiversity protection. Science 2017, 356, 260–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guillebaud, J. Voluntary family planning to minimise and mitigate climate change. BMJ 2016, 353, i2102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- UNDESA. World Population Prospects, the 2022 Revision; Population Division, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2022; Available online: http://population.un.org/wpp (accessed on 20 August 2023).

- Worldometer. World Population by Year. Updated 2023. Available online: https://www.worldometers.info/world-population/world-population-by-year/ (accessed on 20 August 2023).

- Silver, L.; Huang, C. Key Facts about China’s Declining Population; Pew Research Center: Washington, DC, USA, 2022; Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2022/12/05/key-facts-about-chinas-declining-population/ (accessed on 20 August 2023).

- Worlddata. Asia 2023. Available online: https://www.worlddata.info/asia/india/populationgrowth.php (accessed on 20 August 2023).

- UNEP. Report from Biodiversity Conference (COP 15). In Proceedings of the Biodiversity Conference (COP 15), Montreal, QC, Canada, 7–19 December 2022; Available online: https://www.unep.org/un-biodiversity-conference-cop-15 (accessed on 20 August 2023).

- WWF. Living Planet Report 2022. Available online: https://wwf.org.au/what-we-do/living-planet-report/ (accessed on 20 August 2023).

- UNICEF. 10 Million Additional Girls Risk Child Marriage. Press Release, 8 March 2021. Available online: https://www.unicef.org/eap/press-releases/10-million-additional-girls-risk-child-marriage-due-covid-19-unicef (accessed on 20 August 2023).

- World Food Program. A Global Food Crisis. 2023. Available online: https://www.wfp.org/global-hunger-crisis (accessed on 20 August 2023).

- OECD. Development Co-Operation Report 2023; OECD, Development Assistance Committee: Paris, France, 2023; Available online: https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/development/development-co-operation-report-2023_f6edc3c2-en# (accessed on 20 August 2023).

- World Meteorological Organisation. Earth Had Hottest Three-Month Period on Record, with Unprecedented Sea Surface Temperatures and much Extreme Weather. 2023. Available online: https://public.wmo.int/en/media/press-release/earth-had-hottest-three-month-period-record-unprecedented-sea-surface (accessed on 20 August 2023).

- Falconer, R. NOAA: 2023 Worst Year on Record for Billion-Dollar Disasters; AXIOS: Arlington, TX, USA, 2023; Available online: https://www.axios.com/2023/09/12/disasters-weather-climate-record-2023-noaa (accessed on 20 August 2023).

- Kumari Rigaud, K.; de Sherbinin, A.; Jones, B.; Bergmann, J.; Clement, V.; Ober, K.; Schewe, J.; Adamo, S.; McCusker, B.; Heuser, S.; et al. Groundswell: Preparing for Internal Climate Migration; The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Our World in Data. Climate Change Impacts Explorer, Global Atmospheric CO2 Concentration, Long-Run Series. Available online: https://ourworldindata.org/explorers/climate-change (accessed on 20 August 2023).

- Bongaarts, J. Development: Slow down population growth. Nature 2016, 530, 409–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leke, A.; Chironga, M.; Desvaux, G. Africa’s Busininess Revolution; McKinsey & Company: New York, NY, USA; Harvard Business Review Press: Watertown, MA, USA, 2018; Available online: https://www.mckinsey.com/featured-insights/middle-east-and-africa/africas-business-revolution (accessed on 20 August 2023).

- Gerten, D.; Heck, V.; Jägermeyr, J.; Bodirsky, B.L.; Fetzer, I.; Jalava, M.; Kummu, M.; Lucht, W.; Rockström, J.; Schaphoff, S.; et al. Feeding ten billion people is possible within four terrestrial planetary boundaries. Nat. Sustain. 2020, 3, 200–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charpentier-Ljungqvist, F. Africa Still Waits for Its Green Revolution. Svenska Dagbladet, 6 July 2023. Available online: https://www.svd.se/a/wAka6M/afrika-vantar-annu-pa-sin-grona-revolution (accessed on 20 August 2023).

- Maja, M.M.; Ayano, S.F. The impact of population growth on natural resources and farmers’ capacity to adapt to climate change in low-income countries. Earth Syst. Environ. 2021, 5, 271–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molotoks, A.; Smith, P.; Dawson, T.P. Impacts of land use, population, and climate change on global food security. Food Energy Secur. 2021, 10, e261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Economic Commission for Africa. Africa’s Youth and Prospects for Inclusive Development: Regional Situation Analysis Report. 2017. Available online: https://www.ohchr.org/sites/default/files/Documents/Issues/Youth/UNEconomicCommissionAfrica.pdf (accessed on 20 August 2023).

- Cincotta, R.P.; Engelman, R.; Anastasion, D. The Security Demographic: Population and Civil Conflict after the Cold War; Population Action International: Washington, DC, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- UNICEF. Is an End to Child-Marriage within Reach? Latest Trends and Future Prospects, 2023 Update; UNICEF: New York, NY, USA, 2023; Available online: https://data.unicef.org/resources/is-an-end-to-child-marriage-within-reach/ (accessed on 20 August 2023).

- Ratcliffe, A.A.; Hill, A.C.; Dibba, M.; Walraven, G. The ignored role of men in fertility awareness and regulation in Africa. Afr. J. Reprod. Health 2001, 5, 13–19. Available online: https://www.ajrh.info/index.php/ajrh/article/view/878 (accessed on 20 August 2023).

- Dodoo, F.N.-A.; van Landewijk, P. Men, women, and the fertility question in sub-Saharan Africa: An example from Ghana. Afr. Stud. Rev. 1996, 39, 29–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbasi-Shavazi, M.J. Recent Changes and the Future of Fertility in Iran; UNDESA Population Division: New York, NY, USA, 2003; Available online: https://www.un.org/development/desa/pd/sites/www.un.org.development.desa.pd/files/unpd_egm_200203_countrypapers_recent_changes_and_the_future_of_fertility_in_iran_abbasi-shavazi.pdf (accessed on 20 August 2023).

- Ehrlich, P.R.; Holdren, J.P. One-dimensional ecology. Bull. At. Sci. 1972, 16, 18–27. [Google Scholar]

- Wackernagel, M.; Rees, W. Our Ecological Footprint: Reducing Human Impact on the Earth; New Society Publishers: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1996; 160p, Available online: https://faculty.washington.edu/stevehar/footprint.pdf (accessed on 20 August 2023).

- Global Footprint Network. Data Explorer. Available online: https://data.footprintnetwork.org/?_ga=2.76783701.1985416071.1695871927-1560685959.1695871927#/ (accessed on 20 August 2023).

- UNFCCC. The Paris Agreement: Treaty adopted by 196 Parties at the UN Climate Change Conference (COP21) in Paris, France, on 12 December 2015. Available online: https://unfccc.int/process-and-meetings/the-paris-agreement?gclid=EAIaIQobChMI5tuhtd-xgAMVU-fmCh2lFw1ZEAAYASAAEgKcnPD_BwE (accessed on 20 August 2023).

- UNFCCC. Report from Sharm El-Sheikh Climate Change Conference (COP 27). In Proceedings of the Sharm El-Sheikh Climate Change Conference (COP 27), Sharm El-Sheikh, Egypt, 6–20 November 2022; Available online: https://unfccc.int/cop27?gclid=EAIaIQobChMIgqik5uCxgAMV5jsGAB32kABvEAAYASAAEgJkI_D_BwE (accessed on 20 August 2023).

- Johnson, J.A.; Ruta, G.; Baldos, U.; Cervigni, R.; Chonabayashi, S.; Corong, E.; Gavryliuk, O.; Gerber, J.; Hertel, T.; Nootenboom, C.; et al. The Economic Case for Nature: A Global Earth-Economy Model to Assess Development Policy Pathways; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2021; Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10986/35882 (accessed on 20 August 2023).

- Measham, A.R. Birth control in the Third World—Is it Neo-colonialism in disguise? Popul. Dyn. Q. 1994, 2, 18. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12276794/ (accessed on 20 August 2023).

- Tupy, M.L.; Pooley, G.L. Superabundance: The Story of Population Growth, Innovation, and Human Flourishing on an Infinitely Bountiful Planet; Cato Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 2022; ISBN 9781952223396. [Google Scholar]

- Dodgson, R. Contesting Neoliberal Globalisation at UN Global Conferences: The Womens Health Movement, United Nations and the International Conference on Population and Development. Glob. Soc. 2000, 14, 443–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conger, K.H. A Matter of Context: Christian Right Influence in U.S. State Republican Politics. State Politics Policy Q. 2010, 10, 248–269. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/27867149 (accessed on 20 August 2023).

- McKeegan, M. The politics of abortion: A historical perspective. Women’s Health Issues 1993, 3, 127–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atighetchi, D. The position of Islamic tradition on contraception. Med. Law 1994, 13, 717–725. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7731352/ (accessed on 20 August 2023). [PubMed]

- Mumford, S.D. Infallibility and the Population Problem; Church and State: London, UK, 2016; Available online: https://churchandstate.org.uk/2016/03/infallibility-and-the-population-problem-2/ (accessed on 20 August 2023).

- Mumford, S.D. The Life and Death of NSSM 200: How the Destruction of Political Will Doomed a U.S. Population Policy; Church and State Press: London, UK, 1996; Kindle Edition, 2015; Available online: http://churchandstate.org.uk/2015/02/the-life-and-death-of-nssm-200-overpopulation-vatican/ (accessed on 20 July 2023).

- AP/Reuters. Erdogan: Birth Control not for Muslim Families. Deutsche Welle, 30 May 2016. Available online: https://www.dw.com/en/muslim-families-shouldnt-use-birth-control-says-erdogan/a-19293934 (accessed on 20 August 2023).

- Bajaj, N.; Stade, K. Challenging pronatalism is key to advancing reproductive rights and a sustainable population. J. Popul. Sustain. 2023, 7, 39–70. Available online: https://www.whp-journals.co.uk/JPS/article/view/819 (accessed on 20 August 2023).

- Finkle, J.L.; Crane, B.B. Ideology and Politics at Mexico City: The United States at the 1984 International Conference on Population. Popul. Dev. Rev. 1985, 11, 1–28. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/1973376 (accessed on 20 August 2023).

- Statista. Distribution of the Population of Sub-Saharan Africa as of 2020, by Religious Affiliation. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/1282636/distribution-of-religions-in-sub-saharan-africa/ (accessed on 20 August 2023).

- El Feki, S.; Maydaa, C. How to Live and Love under Oppressive Laws. Chatham House, 23 June 2023. Available online: https://www.chathamhouse.org/2023/06/how-live-and-love-under-oppressive-laws (accessed on 20 August 2023).

- Linder, D.H. Seksualpolitikk og Kvinnekamp: Historien om Elise Ottesen-Jensen (Sexual Policy and Fights for Women’s Rights); Tiden Norsk Forl. Libris: Oslo, Norway, 1996; ISBN 139788210039720. [Google Scholar]

- Guinnane, T.W. The historical fertility transition: A guide for economists. J. Econ. Lit. 2011, 49, 589–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eurostat. How Many Children Were Born in the EU in 2021? Eurostat, 9 March 2023. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/products-eurostat-news/w/DDN-20230309-1 (accessed on 20 August 2023).

- de Beauvoir, S. The Second Sex; Gallimard: Paris, France, 1967; ISBN 9782070205134. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. Report of the World Conference of the United Nations Decade for Women. In Proceedings of the World Conference of the United Nations Decade for Women, Copenhagen, Denmark, 14–30 July 1980; Available online: https://www.un.org/en/conferences/women/copenhagen1980 (accessed on 20 August 2023).

- Piketty, T. Capital in the Twenty-First Century; Goldhammer, A., Translator; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2014; ISBN 9780674979857. [Google Scholar]

- Tharoor, I. Does Europe Face a Demographic Crisis? Washington Post, 2 March 2023. Available online: https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/2023/03/02/europe-demographic-crisis-refugee-democracy-suica-dubravka/ (accessed on 20 August 2023).

- Kantorova, V.; Wheldon, M.C.; Ueffing, P.; Dasgupta, A.N.Z. Estimating progress towards meeting women’s contraceptive needs in 185 countries: A Bayesian hierarchical modelling study. PLoS Med. 2020, 17, 1003026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blanco, C. Acceso al control de la natalidad: Un estimativo mundial (Access to birth control: A world estimate). Profamilia 1988, 4, 17–24. (In Spanish). Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12281360/ (accessed on 20 August 2023). [PubMed]

- Sully, E.A.; Biddlecom, A.; Darroch, J.E.; Riley, T.; Ashford, L.S.; Lince-Deroche, N.; Firestein, L.; Murro, R. Adding It Up: In-vesting in Sexual and Reproductive Health 2019; Guttmacher Institute: New York, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, W.C.; Ross, J.A. (Eds.) The Global Family Planning Revolution; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2007; 496p, ISBN 0-8213-6951-2. Available online: https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/6788 (accessed on 1 May 2023).

- Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. Family Planning. Available online: https://www.gatesfoundation.org/our-work/programs/gender-equality/family-planning (accessed on 20 August 2023).

| Major Area Population (Millions) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 2022 | 2030 | 2050 | |

| World | 7942 | 8512 | 9687 |

| Sub-Saharan Africa | 1152 | 1401 | 2094 |

| Northern Africa and West Asia | 549 | 617 | 771 |

| Central and Southern Asia | 2075 | 2248 | 2575 |

| Eastern and Southeast Asia | 2342 | 2372 | 2317 |

| Latin America and the Caribbean | 658 | 695 | 749 |

| Australia/New Zealand | 31 | 34 | 38 |

| Oceania | 14 | 15 | 20 |

| Europe and North America | 1120 | 1129 | 1125 |

| Country | TFR |

|---|---|

| Congo (Dem. Rep.) | 5.96 |

| Mali | 5.92 |

| Niger | 7.15 |

| Nigeria | 5.41 |

| Somalia | 6.12 |

| African fertility average | 4.5 |

| Earth can take: | 1.6 hectares/person |

| But the footprint today: | 2.6 hectares/person |

| Bangladeshi footprint: | 0.7 hectares/person |

| Swede´s footprint: | 5.5 hectares/person |

| US-American footprint: | 7.8 hectares/person |

| China´s footprint: | 3.5 hectares/person |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Norrman, K.-E. World Population Growth: A Once and Future Global Concern. World 2023, 4, 684-697. https://doi.org/10.3390/world4040043

Norrman K-E. World Population Growth: A Once and Future Global Concern. World. 2023; 4(4):684-697. https://doi.org/10.3390/world4040043

Chicago/Turabian StyleNorrman, Karl-Erik. 2023. "World Population Growth: A Once and Future Global Concern" World 4, no. 4: 684-697. https://doi.org/10.3390/world4040043

APA StyleNorrman, K.-E. (2023). World Population Growth: A Once and Future Global Concern. World, 4(4), 684-697. https://doi.org/10.3390/world4040043