Markusen’s Typology with a “European” Twist, the Examples of the French Aerospace Valley Cluster and the Andalucia Aerospace Cluster

Abstract

1. Introduction: Industrial Clusters, Geography, and Institution Building

2. Cluster Prerequisites; or What the Main “Ingredients of a Cluster” Are

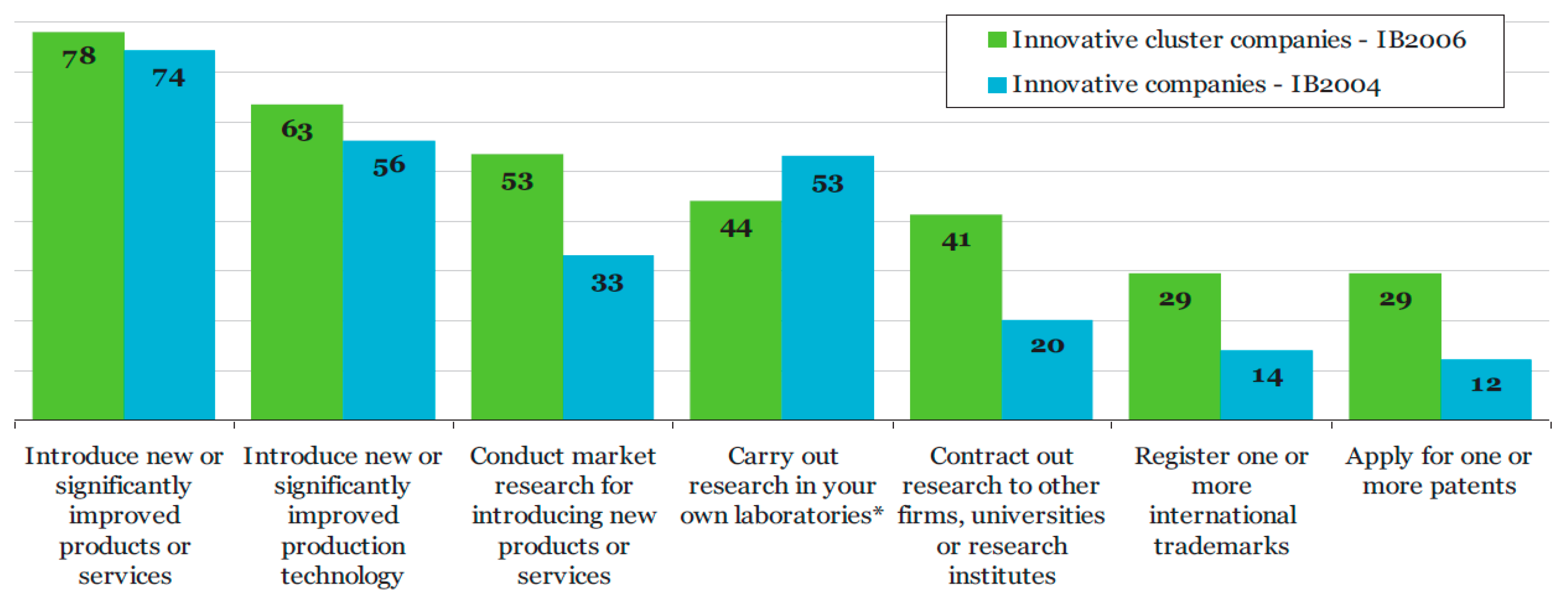

- Are more innovative than non-cluster firms: Over a specific period, 78% of cluster firms introduced significantly improved products/services, compared to 74% of non-cluster firms, during the same period. Similarly, 63% of innovative cluster firms introduced innovative production technology compared to 56% of non-cluster firms. In other words, innovation is spurred by such cluster initiatives where the “cross-pollination” of ideas occurs.

- Are more than twice as likely to source out research to other firms, universities, or public labs compared to the average non-cluster innovative European firms. This supports the view that clusters encourage knowledge dissemination/sharing, which stimulates innovation through cross-conception and exchange of ideas.

- Patent and Trademark their innovations more often: Over the same survey period, when only 12% of innovative non-cluster companies applied for a patent, the percentage of cluster companies that did the same was 29%.

- In 32% of the cases, the initiative to set up a cluster comes from the government. In 27% of the cases, the initiative comes primarily from the industry, in 5% from universities, while in 35% jointly from two or more parties (usually from government and industry).

- In financing, governments’ involvement and contribution are even more critical, as in 54% of the cases, the government is the primary funding source. In comparison, only 18% of clusters are primarily funded by industry, 1% by universities, 2% by international organizations, and 25% by two or more parties.

3. Methodology: Using Markusen as a Starting Point and a Methodological Reference

- The size and number of participating companies within the cluster and their organizational structure.

- The extent to which companies are integrated within the geographical or institutional entity of the cluster, as well as the connections they have developed within and beyond the region.

- The management of innovation within the cluster.

- The presence or absence of a public entity serving as an anchor for the cluster. Additionally, we will try to delineate any inter-European relation the clusters under discussion have by mainly analyzing two different parameters:

- Participation of cluster members in supported international (European) projects/innovation and/or research programs.

- Cooperation of the studied clusters with other European clusters and with institutions and/or structures of the E.U.

4. Clusters: Markusen’s Categorization

- Industrial-complex Model: These industrial complexes are characterized by sets of identifiable and stable relations among firms that are in part manifested in their spatial behavior. The connections are conceived primarily in terms of trading links, and it is these patterns of sales and purchases that are seen as principally governing their locational behavior.

- The Model of Pure Agglomeration: The pure agglomeration model assumes that actors within a cluster operate independently with no cooperation beyond their individual interests in a competitive and atomized environment. The model suggests that profitable local interactions occur through a combination of chance, the law of large numbers (which increases the likelihood of suitable partners being available), and the natural selection of businesses that benefit from the opportunities available.

- The Social-network Model: In this type of cluster, the relationships between the parties of the cluster are built on rules and regulatory norms that essentially cover the totality of the cluster behaviors.

- Marshallian clusters consist mainly of locally owned SMEs [43] and are characterized by significant cooperation levels among these SMEs [42]. Marshallian clusters are also characterized by low degrees of cooperation or linkage with firms external to the district and a high level of “embeddedness” to the district, which creates a unique local cultural identity [8]. The “bonds” created between the companies of the cluster are based on “interactions” that promote trust and a “sense of belonging”, reducing transaction costs and facilitating the exchange of information and knowledge through the existence of interpersonal relationships, enhanced by intensive exchanges of personnel between the firms of the cluster [44]. The cluster members create and share innovation [8], while knowledge transfer is both intended and unintended and is often the result of proximity and employees’ mobility between companies [45]. Cooperation is formally encouraged by government-sponsored industry organizations [46].

- Hub-and-spoke types of clusters have one or a few dominant firms surrounded by multiple smaller suppliers [18]. The clusters’ structure is hierarchical and unsymmetrical [22]. It is defined by the existence of companies with greater financial and institutional weight, which delineates the development and structure of the cluster [23], acting as a hub. The hub companies are located within the location of the cluster [47]. The importance of the hub companies in the formation and sustainability of a cluster is highlighted by the work of Carbonara [48] (2002), who researched clusters from Italy, concluding that the most dynamic of them modified their configuration and structure. The most prominent of the changes/modifications was the increasingly important role of large firms, with a leading/hub position within the cluster. A well-known example of a district with hub-and-spoke clusters is Seattle, where Boeing acts as the hub for the aerospace industry and Microsoft for the software industry, while the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Center and the University of Washington “shaped” the faith and structure of the local biotechnology industry [18]. Another example of a hub-and-spoke cluster is that of the East Midlands Aerospace cluster in the U.K. The cluster’s hub firm is the British engine manufacturer Rolls-Royce, and the spokes are its many second- and third-tier suppliers and other SMEs [49]. The leading firms of the hub-and-spoke clusters act as a “gatekeeper” for the clusters, enabling them to connect with global networks, affecting their sustainability [23], and also “regulating” and shaping the innovation process of the cluster [45]. Under this context, Malipiero, Munari, and Sobrero [30] conclude that hub companies act as “engines of innovation, internally generating new and sophisticated knowledge,” and by leveraging on their intellectual and social capital, they act as “technological gatekeepers” facilitating the absorption and internal dissemination of knowledge. Hub companies usually have stronger ties to national trade associations than local, as they tend to lobby more on the national than local level [18].

- Satellite platform: As in the hub-and-spoke type of clusters, the structure of a satellite platform cluster is somehow hierarchical and unsymmetrical [22], typically consisting of an assemblage/concertation of branch facilities of externally based multinational firms [50,51]. One of the satellite platform clusters that is frequently mentioned in the literature is that of the Research Triangle Park in North Carolina, which groups together several R&D centers of high-tech multinational firms [50,51]. Other examples of satellite platform clusters are the aerospace clusters of Mexico, such as the one situated in Baja California [52,53]. In such types of clusters, the remotely located “parent” company/ies make crucial decisions for the local companies consisting of the core of the cluster, thus “shaping” the structure and potentiality of the cluster [50]. The capabilities and knowledge provided by local companies lead to a form of cooperation between the local aspects of a cluster and externally based multinational firms, creating a “multiple diamond” cluster composition rather than a “single diamond” composition [54]. When it comes to innovation, the multinational “parent” companies are simultaneously a knowledge generator and a knowledge seeker, as Rugman and Verbeke [54] conclude, also playing the role of “global pipelines” diffusing knowledge [55]. Such pipelines are beneficial for the accumulation of knowledge only if the “local aspects/firms” of the cluster are either characterized by a “high-quality local buzz” or are weakly endowed in terms of knowledge as Morrison et al. [55] concluded. The local and/or national government’s role is to provide infrastructure, tax breaks, and other generic business inducements [8].

- State-anchored: While in the types mentioned above of clusters (Marshallian, Hub-and-spoke, Satellite platform) already discussed, the initiative for the creation and the management of them is mainly taken by companies (locally owned SMEs—Marshallian clusters, hub companies—hub-and-spoke clusters, and satellite “parent” companies—satellite platform clusters), in this type of clusters the activity of the member companies is “anchored” to one or several large, governmental institutions such as military bases, state or national capitals, large public universities, etc. [8]. We should not fail to notice that governmental help is provided to all types of clusters. The difference in the state-anchored cluster is, as Markusen and Park [56] concluded in their research on the case of the Changwon cluster, South Korea, the state’s role as the lead agent, a factor that lessens the importance of traditional locational aspects. The Changwon cluster was established because of the state’s dedication to building a military supply sector. State-anchored clusters are characterized by centrally coordinated innovation aligned with the public objectives of the anchor institution [20], while the creation of innovation is not significantly dependent on the members of the cluster [45] or on the development of the cluster.

- The size and number of participating companies within the cluster and their organizational structure.

- The extent to which companies are integrated within the geographical or institutional entity of the cluster, as well as the connections they have developed within and beyond the region.

- The management of innovation within the cluster.

- The presence or absence of a public entity serving as an anchor for the cluster.

5. Case Studies

5.1. Analyzing the French Aerospace Valley Cluster

- 130,000 industrial jobs;

- 1500 business establishments;

- 1/3 of France’s workforce in aeronautics and over 50% in the space sector;

- 8500 researchers;

- 2 of France’s 3 prestigious aeronautics and space engineering schools.

- Structures, Materials, and Processes;

- Energy and Electro-mechanical Systems;

- Air Transport Safety and Security;

- Navigation Telecommunications and Observation;

- Embedded Systems, Electronics, and Software;

- Man–Machine Interface;

- Maintenance, Repair, and Overhaul;

- Future Factory;

- Highly complex system design and integration.

- Creating strategic synergies between academia and the business sector: The Aerospace Valley cluster has created “strategic synergies” bringing together the business sector and academia enabling the creation of a strong innovation base, by enhancing access to new knowledge. It is worth repeating that two of France’s three most prestigious aeronautics and space engineering schools are members of the cluster. Enabling interpersonal relationships between the students of the schools and the companies has led to the creation of a “technological circle”, mostly based on the so-called “tacit knowledge”, the knowledge that is difficult to circulate, mainly due to the nature of the message it conveys and which is better diffused through face-to-face interactions.

- Creating jobs for highly qualified personnel: It is worth mentioning that the cluster mostly provides jobs for qualified personnel, as 1/3 of France’s aeronautics professionals and over 50% of those in the space sector work for companies that are members of the Aerospace Valley cluster.

- Forging strategic collaborations with other clusters: The Aerospace Valley cluster from its initial steps forged strategic collaborations/alliances with other European space clusters. The cluster has also formed partnerships with clusters from other industrial domains, such as agriculture and ICT. Since the applications/technologies developed by the cluster’s companies can be used in several industrial fields, the cluster can diversify its market reach.

5.2. Analyzing the Andalusian Aerospace Cluster

- -

- To promote a sustainable scientific and technological development of the Andalusian aerospace and industrial sector;

- -

- To contribute actively to the training and education of professionals in the sector;

- -

- To promote business excellence through synergies between partner companies;

- -

- To encourage and facilitate interactions between member companies in the aerospace industry;

- -

- To act as institutional representation vis-à-vis public institutions and organizations at the national and international levels.

- The goal of the ASSETs + project is to establish a sustainable supply chain of human resources and redefine the required skill sets in the military sector.

- AERIS aims to enhance the competitiveness of companies in the aeronautical sector in the Andalucía-Alentejo cross-border region by facilitating innovation and technology transfer.

- The objective of the prestigious project is to enhance collaboration among UAV clusters in Europe and assist SMEs in their international expansion.

6. Conclusion and Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Porter, M.E. Clusters and the New Economics of Competition. Harv. Bus. Rev. 1998, 76, 77–90. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Buciuni, G.; Pisano, G.P. “Can Marshall’s Clusters Survive Globalisation?” In Harvard Business School Working Paper. No. 15-088. 2015. Available online: https://dash.harvard.edu/handle/1/15548532 (accessed on 29 September 2021).

- Porter, M.E. The Competitive Advantage of Nations, Harvard Business Review. 1990. Available online: http://economie.ens.fr/IMG/pdf/porter_1990_-_the_competitive_advantage_of_nations.pdf (accessed on 25 November 2022).

- Krugman, P. Increasing returns and economic geography. J. Political Econ. 1991, 99, 483–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mytelka, L.; Farinelli, F. Local Clusters, Innovation Systems and Sustained Competitiveness. In Proceedings of the Local Productive Clusters and Innovation Systems in Brazil: New Industrial and Technological Policies for Their Development, Rio de Janiero, Brazil, 4–6 September 2000; UNU/INTECH Discussion Papers. The United Nations University, Institute for New Technologies: Maastricht, The Netherlands, 2000. ISSN 1564-8370. [Google Scholar]

- Gordon, I.R.; McCann, P. Industrial Clusters: Complexes, Agglomeration and/or Social Networks? Urban Stud. 2000, 37, 513–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerrieri, P.; Pietrobelli, C. Models of industrial districts’ evolution and changes in technological regimes. In Proceedings of the the DRUID Summer Conference “The Learning Economy. Firms, Regions and Nation Specific Institutions”, Rebild/Aalborg University, Aalborg, Denmark, 15–17 June 2000. The research leading to this paper has been supported by the European Commission through the DGXII TSER Project «SMEs in Europe and East Asia: Competition, Collaboration and Lessons for Policy Support» (Contract No. SOE1CT97-1065). [Google Scholar]

- Markusen, A. Sticky Places in Slippery Space: A Typology of Industrial Districts. Econ. Geogr. 1996, 72, 293–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gareev, Τ.R. Clusters in the institutional perspective: On the theory and methodology of local socioeconomic development. Balt. Reg. 2012, 3, 4–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, R.; Sunley, P. Deconstructing clusters: Chaotic concept or policy panacea? J. Econ. Geogr. 2003, 3, 5–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karaev, A.; Koh, S.C.L.; Szamosi, L.T. The cluster approach and SME competitiveness: A review. J. Manuf. Technol. Manag. 2007, 18, 818–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.K.; Garg, S.; Deshmukh, S.G. Strategy development by SMEs for competitiveness: A review. Benchmarking Int. J. 2008, 15, 525–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.K.; Garg, S.; Deshmukh, S.G. The Competitiveness of SMEs in a globalised economy: Observations from China and India. Manag. Res. Rev. 2010, 33, 54–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jankowska, B.; Götz, M.; Główka, C. Intra-Cluster Cooperation Enhancing SMEs’ Competitiveness—The Role of Cluster Organisations in Poland. J. Reg. Res. 2017, 39, 195–214. [Google Scholar]

- Keeble, D.; Wilkinson, F. Collective Learning and Knowledge Development in the Evolution of Regional Clusters of High Technology SMEs in Europe. Reg. Stud. 1999, 33, 295–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cumbers, A.; Mackinnon, D.; Chapman, K. Innovation, collaboration, and learning in regional clusters: A study of SMEs in the Aberdeen oil complex. Environ. Plan. 2003, 35, 1689–1706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, R.; Hunt, S. The Commitment-trust theory of relationships marketing. J. Mark. 1994, 57, 20–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, M.; Golob, E.; Markusen, A. Big Firms, Long Arms, Wide Shoulders: The ‘Hub-and-Spoke’ Industrial District in the Seattle Region. Reg. Stud. 1996, 30, 651–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albino, V.; Carbonara, N.; Giannoccaro, I. Supply chain cooperation in industrial districts: A simulation analysis. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2007, 177, 261–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jankowiak, A. The Cluster Initiatives and a Role of Government in the Development of Clusters. Challenges of the Global Economy; Working Papers, no 31; Institute of International Business University of Gdansk: Gdansk, Poland, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Kowalski, A.Μ. The Role of Innovative Clusters in the Process of Internationalisation of Firms. J. Econ. Bus. Manag. 2014, 2, 181–185. [Google Scholar]

- Lan, W.; Kai, W. The Multilevel Gray Evaluation of Innovation Capability of Hub-and-Spoke Enterprise Clusters. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Information Management, Innovation Management and Industrial Engineering, Washington, DC, USA, 26–27 December 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Randelli, F.; Lombardi, M. The Role of Leading Firms in the Evolution of SME Clusters: Evidence from the Leather Products Cluster in Florence. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2014, 22, 1199–1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birkinshaw, J. Upgrading of Industry Clusters and Foreign Investment. Int. Stud. Manag. Organ. 2000, 30, 93–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vass, L.T. Doing More Deals: Re-Envisioning the Use of Industrial Clusters to Target Regional Innovation Investments. 2008. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=1273592 (accessed on 19 July 2021). [CrossRef]

- European Commission; Directorate-General for Enterprise and Industry. The Concept of Clusters and Cluster Policies and Their Role for Competitiveness and Innovation: Main Statistical Results and Lessons Learned; Publications Office: Brussels, Belgium, 2008; Available online: https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2769/67535 (accessed on 29 July 2021).

- Rosenfeld, S. Industrial Strength Strategies: Regional Business Clusters and Public Policy; Aspen Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 1995; ISBN 0-89843-175-1. [Google Scholar]

- Rialland, A. Cluster Dynamics and Innovation; Report No. 270130.00.03; Norwegian Marine Technology Research Institute: Trondheim, Norway, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Giuliani, E.; Bell, M. The micro-determinants of meso-level learning and innovation: Evidence from a Chilean wine cluster. Res. Policy 2005, 34, 47–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malipiero, A.; Munari, F.; Sobrero, M. Focal Firms as Technological Gatekeepers within Industrial Districts: Evidence from the Packaging Machinery Industry. Ind. Corp. Chang. 2005, 21, 429–462. [Google Scholar]

- Morrison, A. Gatekeepers of Knowledge within Industrial Districts: Who They Are, How They Interact. Reg. Stud. 2008, 42, 817–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferretti, Μ.; Parmentola, A. Leading Firms in Technology Clusters: The Role of Alenia Aeronautica in the Campania Aircraft Cluster. Int. J. Bus. Manag. 2012, 7, 65–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mudambi, R.; Swift, T. Technological clusters and multinational enterprise R&D strategy. Adv. Int. Manag. 2010, 23, 461–478. [Google Scholar]

- Owen-Smith, J.; Powell, W.W. Knowledge Networks as Channels and Conduits: The Effects of Spillovers in the Boston Biotechnology Community. Organ. Sci. 2002, 15, 5–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M.E. Clusters of Innovation: Regional Foundations of U.S. Competitiveness; (Report); Council on Competitiveness: Washington, DC, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Maxwell stamp plc, Guidelines for Cluster Development A Handbook for Practitioners; Prepared for the Ministry of Economy, Labour and Entrepreneurship (MELE), and the Central Finance and Contracting Agency (CFCA); Government of the Republic of Croatia: Zagreb, Croatia, 2012. Available online: https://www.enterprise-development.org/wp-content/uploads/GuidelinesforClusterDevelopment.pdf (accessed on 25 July 2021).

- Barkley, D.L.; Henry, M.S. Advantages and Disadvantages of Targeting Industry Clusters; Research Report 05-2002-03; Clemson, South Carolina, US, Regional Economic Development Research Laboratory, Clemson University Public Service Activities; Clemson University: Clemson, SC, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Sölvell, Ö.; Lindqvist, G.; Ketels, C. The Cluster Initiative Greenbook; Ivory Tower: Stockholm, Sweden, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Gardes, Ν.; Dostaler, Ι.; Barredy, C.; Rouger, C. Aerospace Clusters and Competitiveness Poles: A France-Quebec Comparison. J. Traffic Transp. Eng. 2015, 3, 52–62. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, G. A typology for the case study in social science following a review of definition, discourse, and structure. Qual. Inq. 2011, 17, 511–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowley, J. Using case studies in research. Manag. Res. News 2002, 25, 16–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, J.; Huang, H.I.; Walsh, J.P. A Typology of “Innovation Districts”: What it means for Regional Resilience. In Proceedings of the Industry Studies Annual Conference, 28–29 May 2009; University of Illinois at Chicago: Chicago, IL, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Bell, S.; Tracey, P.; Heide, J. The Organization of Regional Clusters. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2009, 34, 623–642. [Google Scholar]

- Hervas-Oliver, L.; Sempere-Ripoll, F.; Estelles-Miguel, S. Rojas-Alvarado, R. Radical vs incremental innovation in Marshallian Industrial Districts in the Valencian Region: What prevails? Eur. Plan. Stud. 2019, 27, 1924–1939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, M.P.; Serra, F.A.R. Open and closed industry clusters: The social structure of innovation. Rev. Adm. E Contab. Unisinos 2009, 6, 193–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seeley, E. A New View on Management Decisions that Lead to Locating Facilities in Industrial Clusters. J. Bus. Inq. 2011, 10, 81–94. [Google Scholar]

- Basant, R. Knowledge Flows and Industrial Clusters: An Analytical Review of Literature; Working Paper No 2002-02-01; Indian Institute of Management: Ahmedabad, India, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Carbonara, N. New models of inter-firm networks within industrial districts. Entrep. Reg. Dev. 2002, 14, 229–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, D.; Ibrahim, G. Cluster Dynamics: Corporate Strategy, Industry Evolution and Technology Trajectories—A Case Study of the East Midlands Aerospace Cluster. Local Econ. 2006, 21, 362–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Fallah, H. The typology of technology clusters and its evolution—Evidence from the hi-tech industries. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2011, 78, 945–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boja, C.I.T. Clusters as a Special Type of Industrial Clusters. Inform. Econ. 2011, 15, 184–193. [Google Scholar]

- Gomis, R.; Carrillo, J. The role of multinational enterprises in the aerospace industry clusters in Mexico: The case of Baja California. Compet. Chang. 2016, 20, 337–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero, J.M. Centripetal forces in aerospace clusters in Mexico. Innov. Dev. 2011, 1, 303–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rugman, A.M.; Verbeke, A. Foreign subsidiaries and multinational strategic management: An extension and correction of Porter’s single diamond framework. Manag. Int. Rev. 1993, 33, 71–84. [Google Scholar]

- Morrison, A.; Rabellotti, R.; Zirulia, L. When Do Global Pipelines Enhance the Diffusion of Knowledge in Clusters? Econ. Geogr. 2012, 89, 77–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markusen, A.; Park, S.O. The state as industrial locator and district builder: The case of Changwon, South Korea. Econ. Geogr. 1993, 69, 157–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belussi, F. The international resilience of Italian industrial districts/clusters (ID/C) between knowledge re-shoring and manufacturing off (near)-shoring, Investigaciones Regionales. J. Reg. Res. 2015, 32, 89–113. [Google Scholar]

- Aguilera, C.M.; Guerrero, F. Strategic drivers in the evolution towards the advanced collaborative paradigm in the Andalusian Aeronautical cluster. In Proceedings of the 2006 IEEE International Technology Management Conference (ICE), Milan, Italy, 26–28 June 2006; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Aerospace Cluster Initiative. Available online: https://www.eacp-aero.eu/members/aerospace-valley.html (accessed on 29 September 2021).

- Aerospace Valley. Available online: https://www.aerospace-valley.com/les-projets (accessed on 29 July 2021).

- Aerospace Valley. Available online: https://www.aerospace-valley.com/page/nos-projets-europ%C3%A9ens-0 (accessed on 29 July 2021).

- Levy, R.; Talbot, D. Control by Proximity: Evidence from the “Aerospace Valley” Competitiveness Cluster. Reg. Stud. Taylor Fr. 2015, 49, 955–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regina, S. The Emerging Portuguese Maritime Mega Cluster: Endogenous Dynamics and Strategic Actions. In Proceedings of the 54th Congress of the European Regional Science Association: “Regional Development & Globalisation: Best Practices”, St. Petersburg, Russia, 26–29 August 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Etzkowitz, H. The Triple Helix of University—Industry-Government Implications for Policy and Evaluation; Working Paper 2002-11; Science Policy Institute: Stockholm, Sweden, 2022; ISSN 1650-3821. [Google Scholar]

- Etzkowitz, H.; Leydesdorff, L. Τhe Triple Helix—University-Industry-Government Relations: A laboratory for Knowledge Based Economic Development, European Association for the Study of Science and Technology. EASST Rev. 1995, 14, 14–19. [Google Scholar]

- Etzkowitz, H.; Leydesdorff, L. The Dynamics of Innovation: From National Systems and “Mode 2” to a Triple Helix of University–Industry–Government Relations. Res. Policy 2000, 29, 109–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikhaylov, A. Features of the Triple Helix Model in Cross-Border Clusters. World Appl. Sci. J. 2013, 21, 1734–1738. [Google Scholar]

- Irawati, D. Understanding The Triple Helix Model from The Perspective of the Developing Country: A Demand or a Challange for Indonesian Case Study? MPRA Paper No. 5829; BUSINESS SCHOOL—NEWCASTLE UNIVERSITY CITYWALL, 1st Floor-D-149, City gate-St. James Boulevard: Newcastle upon Tyne, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Herliana, S. Regional Innovation Cluster for Small and Medium Enterprises (SME): A Triple Helix Concept. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2014, 169, 151–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otero, J.L. Geography of Innovative Activities in the Andalusian Aeroespace Cluster. Rev. De Estud. Andal. 2014, 31, 127–156. [Google Scholar]

- Hélice Claims A400M Production Worth €130 Million to Andalusian Companies. Available online: https://www.aero-mag.com/hlice-claims-a400m-production-worth-130-million-to-andalusian-companies (accessed on 25 October 2022).

- Invest in Andalucia. Available online: https://www.investinandalucia.es/en/industries/aerospace/ (accessed on 25 October 2022).

- Andalucia Aerospace Cluster. Available online: https://andaluciaaerospace.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/ENG_Corp_Pres_Andalucia_Aerospace_Cluster_Abril2021.pdf (accessed on 25 October 2022).

- Faems, D.; Van Looy, B.; Debackere, K. Interorganizational collaboration and innovation: Towards a portfolio approach. J. Prod. Innov. Manag. 2005, 22, 238–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, G.; Pandit, N.; Lööf, H.; Johansson, B. The Influence of Clustering on MNE Location and Innovation in Great Britain; ERSA Conference Papers ersa10p1489; European Regional Science Association: Louvain-la-Neuve, Belgium, 2011; Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/254457530 (accessed on 23 June 2021).

- Kesidou, Ε. Knowledge Spillovers in High-Tech Clusters in Developing Countries, (Ecis) Eindhoven Centre for Innovation Studies, (TU/e) Technological University of Eindhoven. 2004. Available online: http://www.globelicsacademy.org/pdf/EffieKesidou_paper.pdf (accessed on 23 July 2021).

- Bathelt, H.; Li, P.-F. Global cluster networks—Foreign direct investment flows from Canada to China. J. Econ. Geogr. 2014, 14, 45–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Markusen’s Typology of Clusters: A Synopsis | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Marshallian | Hub-and-Spoke | Satellite Platform | State-Anchored | |

| Characteristics of the cluster’s members | Locally owned SMEs | One, or a few, hub firm/s, surrounded by multiple smaller suppliers | Assemblage/concertation of branch facilities of externally based multinational firms | A government-owned or supported entity surrounded by related suppliers (cluster members) |

| Innovation | Members of the cluster create and share innovation | Hub firms “regulating” and shaping the innovation process of the cluster, having the rule of knowledge “gatekeepers” | Multinational “parent” companies are simultaneously a knowledge generator and a knowledge seeker/“global pipelines” and “agents” of knowledge diffusion | Innovation is centrally coordinated, putting any activity in line with the objectives of the “anchor” institution |

| Governmental institutions | Government-sponsored industry organizations | Hub companies have stronger ties to national trade associations than local | Local and/or national government provide infrastructure, tax breaks, and other generic business inducements | Anchor institution/state is the lead agent |

| Cooperation with companies and/or other entities not part of the cluster | Low degrees of linkage with firms external to the district/high level of “embeddedness” to the district, unique local cultural identity | Defined by the hub firm/s | Defined by the “parent” multinational firm/s | Extended with the institution the cluster is “anchored” to |

| Aerospace Valley | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Members | Innovation | Governmental Institutions | Collaboration with External Structures |

| SMEs and large companies | Creating strategic synergies between academia and the business sector | Manages research projects funded by the French state | Developing extensive links with other French and European aerospace clusters |

| Andalusian Aerospace Cluster | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Members | Innovation | Governmental Institutions | Collaboration with External Structures |

| SMEs and large companies | Innovation is diffused to “auxiliary” companies by leading companies | Andalusian government has a Strategic Aeronautics Industry Plan Promoted the construction of scientific and technological parks specializing in the aerospace industry | Airbus plays a dominant role: Sales to airbus represents 86% of the total sales of the cluster |

| Cluster | Members | Innovation | Governmental Institutions | Collaboration with External Structures |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Andalusian Aerospace cluster | SMEs and large companies | Innovation is diffused to “auxiliary” companies by leading companies | Andalusian government has a Strategic Aeronautics Industry Plan Promoted the construction of scientific and technological parks specializing in the aerospace industry | Airbus plays a dominant role: sales to airbus represent 86% of the total sales of the cluster |

| French Aerospace Valley cluster | SMEs and large companies | Creating strategic synergies between academia and the business sector | Manages research projects funded by the French state | Developing extensive links with other French and European aerospace clusters |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kyriazis, V.; Metaxas, T. Markusen’s Typology with a “European” Twist, the Examples of the French Aerospace Valley Cluster and the Andalucia Aerospace Cluster. World 2023, 4, 185-201. https://doi.org/10.3390/world4010013

Kyriazis V, Metaxas T. Markusen’s Typology with a “European” Twist, the Examples of the French Aerospace Valley Cluster and the Andalucia Aerospace Cluster. World. 2023; 4(1):185-201. https://doi.org/10.3390/world4010013

Chicago/Turabian StyleKyriazis, Vasileios, and Theodore Metaxas. 2023. "Markusen’s Typology with a “European” Twist, the Examples of the French Aerospace Valley Cluster and the Andalucia Aerospace Cluster" World 4, no. 1: 185-201. https://doi.org/10.3390/world4010013

APA StyleKyriazis, V., & Metaxas, T. (2023). Markusen’s Typology with a “European” Twist, the Examples of the French Aerospace Valley Cluster and the Andalucia Aerospace Cluster. World, 4(1), 185-201. https://doi.org/10.3390/world4010013