1. Introduction

Religious travel is not new, as the activity has been considered ancient for centuries. The sector is unique from other tourism segments and remains a big industry. Religious tourism is associated with pilgrimage travel for rituals and spiritual renewal rather than pleasure and leisure [

1]. The increase in religious and spiritually driven travel accords with tourism growth in the modern era. Millions of people are drawn to the world’s most prominent religious sites annually. However, tourism is one of the industries that was adversely affected by the lengthy global restricted movement and closed borders for travel due to the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) outbreak [

2]. Access to major holy sites was strictly limited or entirely denied and temporarily closed during the pandemic. For instance, the pandemic caused the cancellation of Hajj 2020, which impacted millions of Muslims worldwide.

Five years before the pandemic in 2020, religious tourism, such as pilgrimages, had expanded dramatically. Many Muslims choose to perform the Umrah pilgrimage to Makkah (which includes visiting Madinah) due to there being more access to cheaper travel packages and better economic conditions [

1,

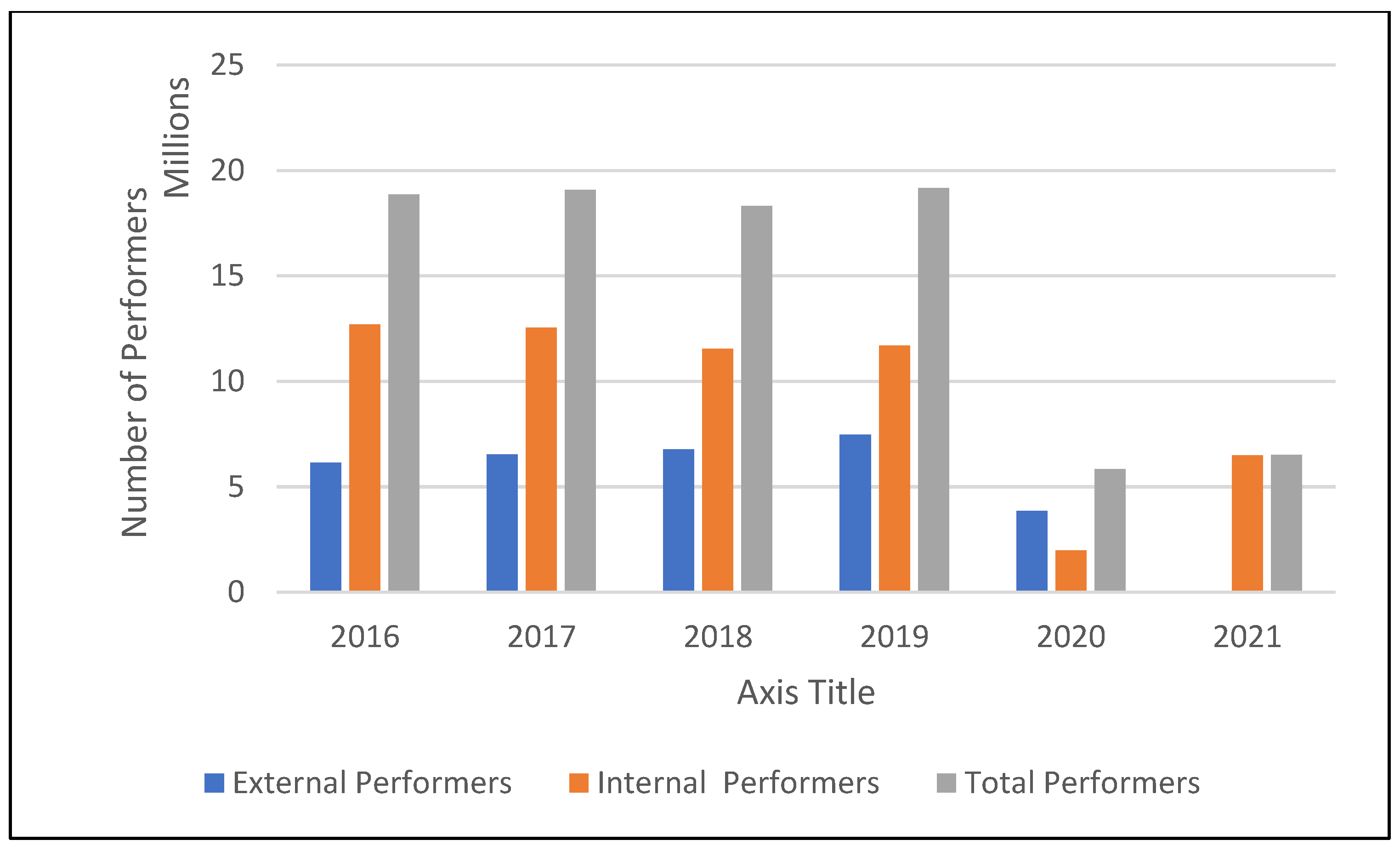

3]. According to statistics provided by the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, the number of people performing Umrah from both inside and outside the country grew up until the epidemic in the year 2020 [

4].

Figure 1 shows the number of Umrah performers from within and outside the country from 2016 to 2021.

In Malaysia, the number of Umrah pilgrims grew from 196,072 in 2014 to 250,809 in 2017 and 274,066 in 2019. The total Hajj and Umrah pilgrims in Malaysia increased by 24% annually from RM1.56 billion in 2014 to RM2.67 billion in 2017 [

5]. The report from DinarStandard, State of the Global Islamic Economy (SGIE), in 2018 highlighted that the global Muslim travel market segment is predicted to be worth USD 274 billion in 2024 [

6]. Nevertheless, the estimate decreased due to the three-year COVID-19 outbreak, which severely impacted the tourism industry. The latest SGIE 2022 report mentioned that Muslims spent USD 102 billion on travel in 2021, which would increase to USD 154 billion by 2022 and USD 189 billion by 2025 [

7]. Although religious tourism was affected by the pandemic, the sector is recovering as many countries allow global tourist travel. In 2022, for the first time after the pandemic, the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia permitted one million local and foreign pilgrims aged 18 to 65 to perform Hajj as long as they tested negative for COVID-19 and were fully vaccinated against the virus.

Although both Hajj and Umrah are performed at Mekkah, they are not the same. Hajj is more challenging and one of the five pillars of Islam. Because it must be conducted at a specified time of year, Muslims around the world will come to participate in performing Hajj. However, since the Government of Saudi Arabia has set the Hajj quota for each nation at 0.1 percent of the total population, not everyone is allowed to undertake Hajj. The official quota for Malaysia is around 31,600, based on the current population of approximately 32 million [

8]. As a result, even if a Muslim has adequate wealth and physical health, most Muslims are unable to go for Hajj due to the long waiting list. Thus, many Muslims choose to perform Umrah to fulfill spiritual and personal rewards, depending on their faith and beliefs, to express their devotion and submission to God. Although Umrah may include some leisure activities such as sightseeing and shopping, the primary purpose of the pilgrims is to perform religious Umrah rituals. Umrah rituals can also be repeated as many times as pilgrims desire while in Mekkah by traveling out to Miqat.

Current religious journeys involve various sub-niches ranging from the luxury trip market to backpacking and institutional religious travel for voluntary humanitarian experiences to assist the needy [

9]. Religious travel is a traditional type of traveling motivated by religious and spiritual commitment. According to Collins-Kreiner [

10], religion can be interpreted in various ways due to the complexity of religion and tourism, and they are often treated separately with little interrelated or comparative analysis, but the concept is changing. Although religion and tourism have different purposes and objectives, religious tourism is a type of tourism that combines both religious and tourism activities. Religious tourism is regarded as a spiritual journey rather than a traditional leisure break or vacation, and it depends on the spiritual ritual’s level of obligation, travel duration, rituals, and the number of people involved.

In addition, convergence and divergence of consumption patterns can be attributed to the development of new technologies and the process of globalization. Convergence and divergence of consumption behaviors exist due to technological improvement and globalization [

3]. These behaviors reflect the changing character of society, including economic growth, urbanization, and access to various cultures through modernization [

11,

12]. Correspondingly, Olsen and Timothy [

13] stated, “religion has played a key role in the development of leisure over the centuries and has influenced how people utilize their leisure time”. Although most religious tourists visit ancient sacred sites, many of the sites have evolved with modern infrastructure and services in recent decades.

The link between tourism activities and their implications is uniquely embedded in the tourism system [

14]. The three sources identified impact travel well-being: first, travel aids in activity participation; second, travel is associated with affective reactions; and finally, a travel organization determines the amount of time left to conduct activities and the amount of stress associated with those activities [

15]. Travelers’ attitudes and well-being are determined by the degree of traveler satisfaction, such as experience and activities during the trip related to anxiety, enjoyment, relaxation, stress, and other emotions formed during activities and traveling, which incorporate different affective responses [

3]. Although tourism studies focus on well-being through an extensive range of philosophical and psychological terms, such as quality of life and life satisfaction, tourism and individual well-being issues are understudied [

14,

16]. Research studies have explained how behavioral preferences impact travelers’ mental and physical well-being, the type of holidays, duration, and preference of a specific destination, and what level or even activity could significantly affect well-being outcomes [

17,

18]. Some examples of tourism that promote well-being are nature tourism [

19,

20,

21], spa tourism [

22,

23], social tourism [

24,

25,

26], and wellness tourism [

27,

28].

The experience gained through religious tourism improves travelers’ well-being and quality of life [

1,

16,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34]. Individuals’ past and current experiences are profoundly impacted by the trips they take throughout their lives, whether for a grant or therapeutic purposes [

29]. Religious travel involves acquiring an emotional, social, intellectual, spiritual, or physical experience [

1]. Each one of these components is essential to enhancing people’s quality of life as a whole. However, little evidence has outlined the holistic aspects of traveler well-being that measure all aspects of these dimensions. The subjective well-being (SWB) reflects the quality of life (QOL), where a higher QOL implies a more positive SWB associated with several other factors. Although the literature has advanced, the question of conceptualizing and quantifying well-being remains unresolved [

35]. A single concept could not measure well-being due to its multi-level and multi-dimensional structure [

35,

36,

37,

38]. Holistic conceptualizations of health and well-being based on multi-dimensional and synergistic constructs that capture the balance of quality of life have received little sustained empirical attention until the last few decades [

35,

37,

39]. In order to ensure travelers’ experience and satisfaction, it is essential to consider not just their physical and subjective well-being but every single aspect that will affect their experience throughout the journey.

According to Yeoh [

40], there is still a need for a scholarly exploration to enhance the scope of the psychology of pilgrimage practices among Muslims in Malaysia. In this study, well-being is conceptualized as a journey toward “holistic wellness”, which means balancing all the components to the best of one’s ability, such as well-being related to physical, emotional, intellectual, social, financial, and spiritual well-being, to optimize a rewarding journey. The study aims to develop an instrument to measure religious travelers’ well-being based on the concept of the wheel of wellness. The multi-dimensional wellness constructs are founded on six dimensions of well-being from the perspective of Muslim travelers who traveled to the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia to perform Umrah to gauge their level of well-being.

1.1. Islamic Perspective on Travel

“So travel through the land and see what the end of those who denied (the truth) was.” (Quran 6:11)

Traveling serves as a reminder for humankind. Islamic teaching has emphasized travel and its benefits for the body and soul, which increase one’s piety towards the Creator. The two principal origins of Islamic religion and life are based on the Holy Quran and Sunnah (the words and acts of the Prophet Muhammad, peace be upon him, acknowledged by his followers and his kin). The Quran mentions travel as “saiyr”, which means travel or move, and appears 27 times in the Quran with numerous phrases outlined as “Do travel”, “Tell them to travel”, or “Do they not travel?”. Prasetio et al. (2022) explained the impact of the pandemic on religious tourism by highlighting over eight examples of verses in the Quran that directly and indirectly use the word “travel”. Several Quranic verses promote traveling to achieve spiritual, physical, and social goals [

41]. In a Hadith on travel values, Abdullah bin Umar mentioned:

“Allah’s Messenger (peace be upon him) took hold of my shoulder and said, ‘Be in this world as if you were a stranger or a traveler’” [

42].

Imam as-Shafi was one of the four great Sunni Imams who emphasized the benefits of traveling, quoting:

“Leave your country in search of loftiness and travel! For in travel there are five benefits: Relief of adversity, earning of livelihood, knowledge, etiquette, and noble companionship.” (Imam as-Shafi) [

43].

Religious and spiritual journeys in Islam are divided into three forms of activities: Hajj, Rihla, and Ziyara [

44]. Hajj is the fifth Islamic pillar fundamental to Muslim practices and institutions. Hajj is a religious obligation for all practicing Muslims that takes place in Makkah between the 8th and 12th days of the Islamic lunar calendar month of Dhu al-Hijjah. Every physically and financially capable Muslim must perform Hajj at least once in their lifetime. Rihla, or the journey for knowledge, business, health, or learning, is the second type of spiritual journey. In comparison, Ziyara is the third journey to holy places such as shrines, mosques, or monasteries in pursuit of spiritual wisdom and showing devotion to eminent religious figures [

13]. Spiritual tourism denotes Muslim visitors who travel for spiritual growth (whether Rihla or Ziyara) and to connect with the Creator [

1,

44].

Umrah is a religious pilgrimage to Makkah performed throughout the year by Muslims worldwide [

3,

45]. Unlike Hajj, Muslims are not obligated to perform Umrah, which can be performed once or many times as long as the individual is physically and financially capable. Muslim travelers consider Umrah the perfect way to improve their spiritual existence and connection with the Almighty God. Umrah is a form of religious travel practice closely linked to Islamic principles comprising several ritual acts performed in a specific order. The first ritual is called Ihram, which is entering a state of purity and holiness that deters one from performing certain Halal (lawful) and Mustahabb (neither encouraged nor discouraged) duties. Second, tawaf involves revolving around the Kaabah seven times. Meanwhile, sa’I is to traverse seven times between Safa and Marwah. Tahallul is the final shaving or cutting of some part of the hair ritual to signify the end of the Ihram and the completion of Umrah. Muslims will also visit historical and holy places, such as Jabal Tsur, Arafah, Jabal Rahmah, and the Mountain of Jabal Nur in Makkah and Jabal Uhud in Madinah.

1.2. Well-Being from Wellness Dimensions Perspective

Well-being has been conceptualized in various ways, including from the perspectives of hedonic and eudaimonic well-being, quality of life, and wellness techniques. Measurement varies greatly depending on the nature and field of studies conducted [

35]. Well-being from the wellness approach focuses on optimal functioning as a person. Dunn (1961, p. 4) defines wellness as “an integrated method of functioning which is oriented toward maximizing the potential of which the individual is capable”. Hettler [

46] developed the wheel of wellness (WoW) model consisting of six types of wellness that must be present to achieve overall wellness, as each dimension is a critical component in enhancing individuals’ overall QOL.

The widely used definition defines wellness as a way of life oriented toward optimal health and well-being. The individual integrates body, mind, and spirit to live more fully within the human and natural community [

47]. Individual optimum wellness is an ongoing commitment to finding a balance related to personal responsibility for directing life toward optimum health and well-being. Myers, Sweeney [

48] specified that wellness is a multi-faceted concept that integrates mental and physical health with environmental and social aspects. Hence, wellness integrates physical, spiritual, and mental well-being [

49]. The following section discusses the dimensions of wellness, incorporating spiritual, physical, emotional, intellectual, social, and financial dimensions.

1.2.1. Spiritual Wellness

Spiritual health in human life relates to finding meaning and purpose while embracing and transcending one’s position in the world [

36]. Spiritual wellness denotes a constructive understanding of sense and purpose in life and acknowledging and uniting strengths of the mind and body [

50]. Spiritual well-being displays how well individuals live in harmony with themselves, others, nature, and God [

51]. The aspect entails understanding the intricacy and extent of life and natural forces in the cosmos or God, unity with the environment, and the communal domain includes values such as love, equity, optimism, and faith in humanity [

52]. In religious tourism, religious activities, such as pilgrimages, aim at creating a sense of importance in the human mind for a mutual goal of uniting humankind, avoiding non-religious desires, and eventually being attentive to the love of the Creator [

53]. Individuals perform religious rituals to purify from all sins and grow closer to God with pure intention and emphasis on achieving a purpose in life.

1.2.2. Physical Wellness

One of the six wellness components includes physical wellness, comprising all facets of lifestyle and physical self-choices. Physical wellness is the degree to which cardiovascular fitness, flexibility, and strength are maintained and improved [

54,

55]. The aspect reflects a person’s ability to maintain a healthy QOL without experiencing fatigue and physical stress to perform daily routines. Determining how behaviors significantly impact well-being and maintaining healthy habits while avoiding harmful ones can result in optimum physical wellness in religious traveling. Nonetheless, physical wellness involves many activities that are frequently stimulating to some extent [

55]. Most travel health and safety issues have occurred among individual travelers.

1.2.3. Emotional Wellness

Emotional wellness is an enduring ongoing process involving self-consciousness, constructive expression, reaction management, an optimistic approach to life, and a realistic self-evaluation [

54]. Moore and Leafgren [

56] defined emotional wellness as the capacity to recognize and accept the feeling and the degree to which a person feels optimistic about life and the ability to control their emotions and behave accordingly. Individuals with emotional well-being are adaptable, open to growth, capable of functioning independently, and aware of their constraints [

57]. Pilgrimages and other religious travel activities include processes that increase social interaction and support among pilgrims [

1]. The journey experience helps the travelers’ mental activity, including positivity and volunteerism, which reveal how to strengthen a person’s ability to manage stress and psychological issues. The travelers’ optimism and selflessness due to their religious activities throughout the journey will enable their ability to manage stress and psychological issues.

1.2.4. Social Wellness

Social wellness emphasizes individuals’ relationship with the environment. Keyes [

58] stated that social well-being is evaluating an individual’s situation and social performance. Hettler [

54] suggested that the significant advancement of a healthy environment and community improvement are incorporated into social wellness. Meanwhile, Adams, Bezner [

50] described that social well-being is based on individuals’ interaction instead of the broader community and environment. Specifically, a person’s social wellness is the value of contributing and accepting social support. Social wellness also involves the skills and comfort level expressed in the framework of interpersonal interactions, which entails the deed, intent, motivation, and perception of these interactions. In a nutshell, social wellness reflects the stability and integration of connection among individuals, nature, and society.

1.2.5. Intellectual Wellness

Intellectual wellness is the degree to which an individual can think creatively, engage in mentally challenging activities, and use resources to enhance knowledge [

54]. Horton and Snyder [

59] identified intellectual wellness as a person’s commitment to a lifetime of learning and knowledge sharing. The continuous acquisition, use, sharing, and application of knowledge were attained through the optimum level of activity innovatively and crucially for personal growth and societal improvement. Traveling to unfamiliar places increases personal experiences and intellectual wellness. Sirgy, Kruger [

32] suggested that tour operators should develop programs and services perceived as educational and intellectual accomplishments throughout the journey for intellectual well-being that positively impacts tourists’ life satisfaction.

1.2.6. Financial Wellness

Financial decision making is significant for any individual well-being and financial security. Joo [

60] defined financial well-being as “the state of being financially healthy, happy, and free of worries” based on personal assessments of an induvial financial state. Financial well-being refers to an objective and a subjective concept that assesses the current financial state [

61]. The combined concept contains objective and subjective dimensions, which involve comprehending an individual financial state and management. Money provides access to products and services and the desired choices and opportunities. Nevertheless, many believe they cannot survive without credit cards, which appears untrue in many instances. Traveling involves money, good knowledge of the destination, and currency, which aids travelers in managing the trip better.

2. Materials and Methods

Scale development studies were reviewed in the scale development process to develop a comprehensive traveler well-being scale [

62,

63]. The process involved three main phases: scale generation, refinement, and validation. The study started by examining previous studies, and in-depth interviews were conducted with 25 religious travelers who performed Umrah less than five years ago to provide essential input. Participants were asked to describe their travel experiences and how their journey influenced their overall well-being based on each wellness category. The participants’ responses were compared to the items from the literature review to generate the survey instrument. The 46 items were generated by, adapted, and rephrased from the previous literature and combined to measure wellness constructs for the survey instrument, which were for physical wellness [

60], emotional wellness [

64], spiritual wellness [

52,

65], intellectual wellness [

32], financial wellness [

32,

66], and finally social wellness [

58].

The instrument was developed through item reduction, entailing several steps. First, several marketing academics and postgraduate students were invited to form a panel to scrutinize the items further. Second, the qualitative data results were merged to select the final items. Several items were eliminated after further review based on face-validity considerations. The exploratory factor analysis was employed to identify the most explained variance structure. A main-loading item is an item with a factor loading of 0.5 or greater to refine and purify the items. Finally, the instrument contained 30 items with six wellness dimensions (see

Table 1. The items were translated into English to develop a definite version of the instrument. A bilingual speaker applied a back-to-back translation from Bahasa Malaysia to English to maintain its original meaning. Additionally, a Likert scale was used to measure each statement in the instrument ranging from “agree” to “strongly disagree” for each wellness dimension.

This study employed a non-probability purposive snowball sampling technique. The criteria used to select the unit of analysis for this study are that they must be Malaysian and have performed Umrah less than five years ago. Only those who met these qualifications could complete the self-administered questionnaire. Snowball purposive sampling approach can help ensure that respondents meet the stated criteria. The first part of the questionnaire contained screening questions, including general questions about the Umrah tour packages, the price of the packages, the duration, and the year they performed Umrah. The second part contains variables of wellness dimensions, while the last section is on the respondents’ demographic profile. Structural Equation Modelling (SEM) was used to interpret data, as the method allows researchers to assess the overall model fitness through confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) using AMOS 21.0.

3. Results

Research data were successfully gathered from 202 Muslims with experience traveling to Makkah and Medina in Saudi Arabia to perform Umrah. Observably, most respondents were females (65.8%) and married with three to four children (31.8%). Most respondents were over 45 years old (58.8%), followed by those between the ages of 30 and 44 (28.2%), while the remaining were under 30.

The convergent validity is determined by evaluating the average variance extracted (AVE), the loadings, and the combined reliability [

67].

Table 1 demonstrates that most item loadings exceeded 0.7, and the value of AVE exceeded 0.5, hence confirming that the measures used in the study are valid and reliable.

Table 2 suggests that all the diagonal values exceeded those in the rows and columns, thus indicating sufficient discriminant validity. The scale validity concepts proved satisfactory, as depicted in

Table 1 and

Table 2.

In order to achieve a good model fit, the Chi-square was standardized by the extent of freedom (χ

2/df), which should be ≤3, followed by the goodness fit index (GFI) of ≥0.9. Meanwhile, the adjusted goodness fit index (AGFI) was ≥0.8, the non-normed fit index (NFI) was ≥0.9, the comparative fit index (CFI) was ≥0.9, and the root-mean-squared error (RMSEA) was ≤0.08, respectively. Nonetheless, the

p-value was significant in the CFA analysis and other fit indices, such as χ

2/df = 2.214 (χ

2 = 628.844, df = 284), GFI = 0.805, AGFI = 0.758, CFI = 0.915, TLI = 0.903, and RMSEA = 0.079, thus indicating that the model fit was adequate. Four items were discarded from the model, as they exhibited low loading values.

Figure 2 illustrates the first-order model of wellness dimensions.

4. Discussion

The study developed the instruments of a well-being scale based on the wellness multi-dimensions for Muslim religious travelers who went to Makkah and Madinah for Umrah. Although there has been a steady increase in the number of instruments developed to measure various aspects of well-being from various perspectives [

35], relatively few studies have applied well-being to religious tourism [

1]. Mixed opinions exist in conceptualizing and measuring well-being from varied disciplines and fields. After enduring a spiritual journey, such as a religious pilgrimage, which requires physical strength and courage, health, finances, time, and social connections, the holistic wellness dimensions are essential for enhancing individuals’ overall well-being. The proposed measurement scales developed from this study will enable the measurement of travelers’ well-being pre-traveling, during traveling, and post-traveling by taking into account their state of mind across a wide range of wellness dimensions, including their mental, financial, physical, intellectual, social, and spiritual well-being. The wellness dimensions are significant for seeking and examining individual well-being outcomes in religious tourism. Each of the dimensions proposed is a critical factor in enhancing holistic well-being, which is aligned with the past literature which proposed that well-being should be measured using a multi-framework [

27,

35,

48]. Furthermore, some of these dimensions interact with and overlap to some extent in line within the tourism context by establishing the importance of social, intellectual, and spiritual dimensions [

29,

47,

49].

Spiritual wellness is about a search in human existence for purpose and meaning, where a religious journey strengthens one’s spiritual health. Religious travel often entails quiet contemplation, prayer, and reflection to increase self-awareness and spirituality. Spiritual wellness highlights a positive perspective on life, inner peace, and responsibility toward others and the environment [

51,

52]. Since the number of pilgrims for Hajj is limited, many Muslims perform Umrah to fulfil spiritual and personal rewards to show their devotion and submission to God. In addition, believers are allowed to reaffirm their belief in Allah and rededicate themselves to leading a pious and righteous life. Hence, spiritual well-being may be measured using the item developed, such as developing worship of the Creator, establishing a personal relationship with God, building oneness with the Creator, and fostering a regular prayer routine.

Emotional wellness reflects how much a person feels enthusiastic and optimistic in life and oneself. Emotional wellness is essential for overall well-being, and emotional well-being can substantially enhance religious travel. Umrah enables Muslims to connect with the Creator via spiritual activities, providing inner peace, comfort, and tranquility, fostering emotional well-being [

1,

2]. Travelers can also escape their daily lives and experience new cultures and traditions. Taking a break from regular stress helps lessen anxiety, despair, and other unpleasant feelings and enhance emotional well-being. Emotional well-being during religious travel involves self-reflection, observation, and support. The items developed for emotional wellness are to escape the demands of everyday life, to let go of worries and problems, to get away from everything, to reduce stress levels, to give time and space for reflection, and finally, to be refreshed. Thus, the traveler must be well-prepared to have emotional well-being, which includes emotional regulation, behavioral control, autonomous growth, and stress management.

Physical wellness relates to possessing or maintaining an adequate level of physical fitness to carry out ritual activities, as the trip comprises a variety of tasks that are physically challenging to some extent [

55]. Umrah rituals require much walking, particularly during the tawaf and sa’I. Thus, having an ideal of physical wellness allows pilgrims to fully immerse themselves in experiencing a spiritual journey. The urge to maintain physical fitness before and during the journey will enable the pilgrims to minimize the risk of illness. Pilgrims can lessen the likelihood of becoming ill by prioritizing maintaining their fitness levels before, during, and after the journey. This is especially important for pilgrims aged or with a medical condition and traveling during peak season. Thus, maintaining physical fitness, exercising regularly, being more active, controlling body weight, and improving health are all attributes of maintaining healthy and physically fit habits. Physical wellness is inextricably related to mental health. Hence, physically healthy pilgrims will be able to experience the Umrah journey, which provides a peaceful and serene environment that can help reduce stress and anxiety and promote overall physical and mental wellness. On the other hand, regardless of whether or not a traveler is experiencing physical issues, they are still emotionally and physically prepared for their journey.

Social wellness is positive relationships between nature and others, encouraging and engaging in activities that foster social connections. In religious tourism, people often travel in groups and participate in shared rituals. Performing Umrah, for example, can promote social wellness by fostering a sense of community, equality, generosity, forgiveness, and spiritual growth among Muslims. Umrah brings millions of Muslims worldwide that share the same faith and values. During Umrah, people from all walks of life come together, dress in simple white clothes, and stand shoulder to shoulder in prayer, regardless of race, ethnicity, or social status, promoting equality and social harmony. Hence, social wellness can be measured by how individuals feel like an important part of the community, believe people would listen to them, feel closer to others in the community, feel valued as a religious person, and feel their contribution impacts other people in the community. This is consistent with and reinforces the ideas presented by Fisher, Francis [

51], who identified four factors—self, community, environment, and God—that contribute to overall happiness.

Intellectual wellness denotes a person’s creativity and mentally stimulating activities [

54]. A religious journey concerning intellectual wellness enhances and expands a person’s knowledge and skills while acquiring possible religious knowledge. Umrah provides an opportunity to learn more about Islamic history, rituals, and traditions which can deepen Muslims’ understanding of Islamic teachings and practices [

1,

68]. Pilgrims can visit essential sites such as the Kaaba, Mount Safa, and Mount Marwah and learn about the significance of these locations. It is an individual commitment to a lifetime of learning and knowledge sharing [

59]. Umrah involves several spiritual practices, such as prayer, rituals, and contemplation, allowing pilgrims to reflect on their beliefs and values and gain a deeper understanding of their faith. Thus, having an intellectually fulfilling journey, gaining more knowledge of religion, and reflecting critically on eternal life for spiritual growth are all the measurements of intellectual wellness elements. In line with Sirgy, Kruger [

32], intellectual achievements throughout the journey are suggested to positively impact traveler life satisfaction.

Finally, financial wellness includes understanding a person’s financial state and management. Financial wellness is a state of being in which an individual can meet their financial obligations and manage their finances effectively during the trip. Financial wellness and traveling can be balanced with careful planning, budgeting, and saving money, which will help the traveler meet their financial well-being. Financial stress can lead to anxiety, depression, and other health problems. Hence, a positive financial state will provide peace and impact an individual’s overall well-being, including their physical and mental health, and free them from stress after returning home [

1].

5. Implication of the Study

The results have ramifications for the tourism industry, especially religious tourism, including travel agents, tour operators, hoteliers, and airlines, to improvise their service offerings, specifically in religious tourism. The wellness multi-dimension offers more comprehensive criteria to measure the consequence of the religious journey. Knowledge of travelers’ needs and well-being enables market segmentation to comprehend different travelers’ demands. In Malaysia, there are 573 licensed tour operators and Umrah tourism agencies [

8]. These agencies should incorporate their package into sustainable development practices, and marketing strategies should be focused on the experience based on the wellness dimensions. To improve their services, these agencies need to incorporate wellness dimension principles into their operations, and tourism businesses can provide travelers with transformative and meaningful experiences that contribute to their overall well-being. The scale can be used to assess a tourist destination’s ability to tailor themselves to travelers’ demands and ensure a satisfying journey.

Therefore, the study proposed that travel agents and service providers should comprehend varied tourism segments and the crucial determinants of travelers’ well-being before, during, and after a journey. Understanding how travelers gain knowledge is vital in developing effective communication campaigns and service delivery for marketing management decisions. The knowledge also facilitates service providers to create and customize adequate travel packages and form communication strategies for the religious market.

The information on travel needs is acquired by investigating a person’s well-being and travel behavior. Thus, the holistic well-being aspects will help the preventive measures and improve the travel experience and satisfaction. The wellness multi-dimension scale can be used to test religious travelers’ preparedness to carry out their religious trips. It may be utilized to create wellness programs that will assist the traveler in preparing and what to anticipate during the religious journey. Consequently, the developed scale of wellness dimensions provides experts with a comprehensive and consistent measure of travelers’ well-being upon returning from their journey.