Abstract

Economic crises and instability during the COVID pandemic have led to a significant additional workload and uncertainty for women. The COVID virus has spread extremely rapidly, and mobility and migration are severely limited, at least in the short term. The virus has a significant impact on the health of people from those considered to be migrants and refugees and their access to the labor market. According to Eurostat, 1.4 million people who previously resided in an EU Member State migrated to another Member State, and almost half of this population are women. Migrating women are particularly exposed to a number of specific consequences of the pandemic. Migrant women are disproportionately the first to be laid off and the last to be rehired. This is due to gender discrimination and precarious working conditions, such as low wages, the greater burden of care work, and alternative employment costs, especially given the gender wage gap and the difficulty of accessing the formal economy. This study examines the challenges many migrant women experienced in accessing the Eurozone labor market during the COVID pandemic. Based on this primary objective, the theoretical perspective of this research relies on the segmented labor market theory. Within the framework of documentary research, this work has chosen the path of descriptive analysis to achieve the study’s objectives. The findings presented in an intersectional framework suggest that the impact on migrant women workers during the COVID pandemic is exacerbated by a segmented labor market rooted in a capitalist context and by gendered structures of racism in the European labor market. In a capitalist context, migrant women would be over-represented in the informal economy due to segmented labor market policies and the effects of gendered racism. As a result, they would be at the forefront of redundancies during the pandemic because of their difficulty accessing the European labor market.

1. Introduction

In 2020, the population of the Eurozone (about 28 countries) was almost 460 million, of which 51% were women, with their share ranging from 49% to 53% in individual member states. In the same year, third-country nationals accounted for 5% of the population (an increase from 4% in 2016). In contrast to the total population, slightly more third-country nationals were men (51%). Between 2016 and 2020, Euro-area countries will issue nearly 11.5 million initial applications to third-country migrants, with a peak of 2.9 million (25%) in 2019. Paid employment (36%) accounts for the largest share of initial applications issued, followed by family reasons (28%), other reasons (23%), and education reasons (13%). In all countries, the number of initial applications decreased in 2020 compared to 2019, which may be due in part to the COVID pandemic and resulting travel restrictions. The first permits for paid work in Euro-area countries in 2016–2020 were issued mainly to male migrants. In contrast, the share of female migrants was higher among the permits issued for family reasons in Euro-area countries [1,2].

Experience with the early signs of labor market development during the current pandemic suggests that the COVID measures disproportionately affect immigrants. During the crisis, new immigrants are hit particularly hard in terms of their opportunities in the labor market. Adverse effects can be expected on their long-term employment prospects and the overall integration process. This is particularly the case for those who have not yet been able to gain a foothold in the labor market [3].

The consequences of the COVID crisis for immigrants must be considered from a gender perspective because even before this crisis, the access rate of female immigrants to the European labor market was below average (30% to almost 60%) compared to their peers [4]. However, the challenges associated with the COVID Crisis require a greater focus on immigrant women for several reasons. The influx of female immigrants has steadily increased since 2007. For example, the number of initial applications by female immigrants rose from 23,000 in 2008 to almost 140,000 in 2015, peaking at 250,000 in 2016. Thereafter, immigration declined significantly. Between January 2015 and December 2019, more than half a million women applied for asylum for the first time in countries such as Germany and Sweden, with around 56 percent of them of working age [5,6].

Moreover, migrant women are a particularly vulnerable group of migrants because they are where the specific challenges of migrants, refugees, and women converge. Indeed, they are “triply disadvantaged.” As migrants (including economic migrants) are disadvantaged in the labor market due to language skills and lack of target group-specific human capital, they face additional challenges within the migrant group due to forced migration. These include health problems, lower prior attachment to the host country, and often a lack of evidence of educational qualifications and work experience [7]. These challenges increasingly apply to immigrant women, especially those with family responsibilities, significantly reducing their chances of accessing the labor market. Immigrant women perform worse compared to male immigrants and native-born women. The employment rate of the female population from countries at war and in crisis in Europe was 17 percent on average in 2020. It was 37 percentage points lower than the employment rate of the male population from countries at war and in crisis and 34 and 55 percentage points lower than the employment rates of the female foreign and European populations, respectively [8].

The permanent precariousness of migrant women in the Euro labor market does not only mean a loss of resources but also has a decisive impact on their children’s successful access to the labor market. According to empirical studies, migrant women’s access to the labor market is crucial for their children’s educational success and future labor market position—even more so than for native mothers and children [9]. In particular, mothers’ employment seems to significantly impact their daughters’ employment and income. Moreover, it encourages sons’ participation in housework and childcare, which generally leads to more egalitarian gender attitudes and gender role behavior. Migration research also reaches similar conclusions [10,11,12].

Against this background, this article focuses on migrant women in the Eurozone as a group that seems particularly at risk of precarity and weak access to the labor market in the current COVID crisis. It builds on a large body of research on the integration of recent immigrants and complements it in two ways. First, it addresses the challenges posed by published documents and reports. Second, it analyzes the current crisis-related challenges in the labor market from an intersectional perspective.

2. Access to the Labor Market for Immigrant Women before the COVID Crisis

Despite the various challenges, a positive trend regarding migrants’ access to the European labor market can be observed. About 35 percent of migrants who arrived between 2013 and 2018 were employed. The average stay in the sample at that time was about three years. Five years after moving to Europe, 49 percent of migrants were employed [13].

There is a significant gap in the employment of migrant men and women. While 25 percent of men were employed two years after moving, this was the case for only 5 percent of women [14]. After five years of residence, the labor force participation of female migrants rises to 29 percent and men to 57 percent. At 29 percentage points, it is still significantly lower than the labor force participation of men with a migration background. This difference is related, among other things, to the family constellation and the care situation for (small) children: In particular, women with small children are rarely employed [15,16].

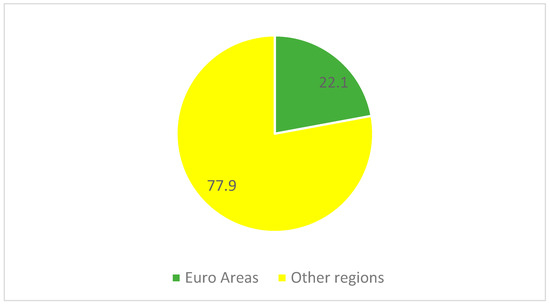

Migrant women also have a slower transition rate into their first job than men [17,18]. When analyzing entry into their first employment role since immigration, ILO data show that 24 months after entry, 22 percent of male migrants but only 6 percent of female migrants have started their first job. This gap widens with the length of stay: Five years after immigration, 76 percent of male migrants but only 31 percent of female migrants have started their first job in Euro-Area [15,19]. In terms of employment aspirations, 63 percent of female migrants who were not employed in 2018, and 86 percent of male migrants intend to take up employment in the future. A further 26 percent of women and 11 percent of men are likely to intend to do so. This makes it clear that the willingness to work is far above the actual level of employment (Figure 1), and thus, the employment potential of migrant women is far from exhausted [15,20,21].

Figure 1.

Distribution of migrant women workers in the Eurozone (percentage) [21].

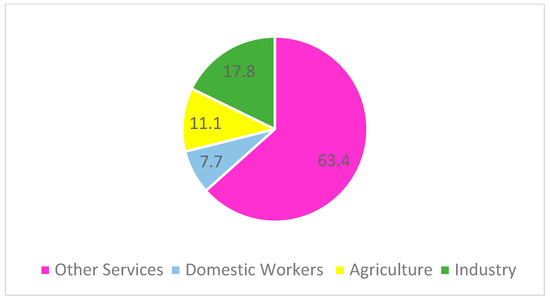

As for the distribution by occupational group, there is an apparent concentration among migrants. This is particularly true for women (Figure 2). Almost 60 percent of women work in five occupational groups. Women work mainly in cleaning, food preparation, education, social work, and remedial education; men, on the other hand, are most likely to work in stock management, post and delivery, food preparation, catering, and cleaning [15,21,22].

Figure 2.

Distribution of migrant women workers in different economic sectors in the Eurozone (percentage) [21].

Many migrants work in menial jobs, especially in the first years after their arrival [22]. This is also reflected in a comparative analysis of employment levels (see Figure 2); more than two-fifths (44 percent) of male migrants worked as helpers in the second half of 2018, half were skilled workers, and a further five percent were complex or highly complex specialist and expert jobs. In contrast, the employment structure of female migrants is more polarized. While 47 percent of migrant women worked as helpers in the second half of 2018, 14 percent held complex or highly complex specialist jobs [23].

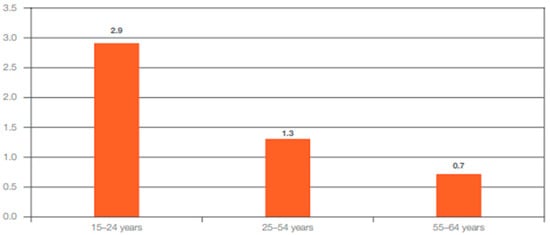

Looking at the type of employment relationship in (Figure 3), it is clear that most migrants—and thus also women—enter the Euro labor market through temporary work, agency work, or without a formal employment contract [24]. In the second half of 2018, women were more likely to be employed on fixed-term contracts, while migrant men were 3.5 times more likely to be employed in temporary or agency work. Moreover, women were twice as likely to work part-time, so-called mini-jobs, at 21 percent compared to employed men [19].

Figure 3.

Percentage of workers employed in temporary agency work by age [24].

3. Theoretical Perspective: Market Segmentation

Among recent labor market theories, insider-outsider theory, efficiency wage theory, and statistical disturbance theory are particularly relevant to our topic. However, these theories illuminate only one aspect of the problem of women’s work. There is no integrated perspective to understanding the relationship between these sub-aspects. It is interesting to note that essential elements of all three theories can be found in the industrial sociological segmentation theory as early as 1970 [25]. The concept of “labor market segmentation” goes back to some work by American industrial sociologists in the early 1970s; as Doeringer and Piore [26] mentioned, the labor market is essentially divided into two markets, one with lower wages, poor working conditions, poor career opportunities, etc., and another with higher wages, good working conditions, high and formalized career opportunities, and so on. The starting point was the observation that in large companies, part of the jobs is tied to internal promotion and mobility chains by administratively determined rules [27]. According to these rules, however, vacancies are mainly filled by company employees (internal labor market). Only at the lower end of the job hierarchy are so-called entry-level positions accessible from the outside. The wage structure in the internal labor market is determined by the characteristics of the jobs, their place in the hierarchy, and the seniority rules [28].

In the Euro-area literature, the conceptual pair of internal and external labor markets is often equated with the concepts of the core workforce (natives, not necessarily) and peripheral workforce (migrants, most likely), focusing on the difference in employment security. However, not all jobs where there is an economic interest in stable employment are necessarily associated with good promotion prospects and high wages. Conversely, high professional qualifications do not automatically mean qualifications in the company. This is particularly true in Europe, where a large proportion of vocational qualifications are acquired in the school and dual training system before entering the labor market. Career paths and mobility opportunities, and consequently the labor market, are more occupation-based and less company-based in structure than in the US.

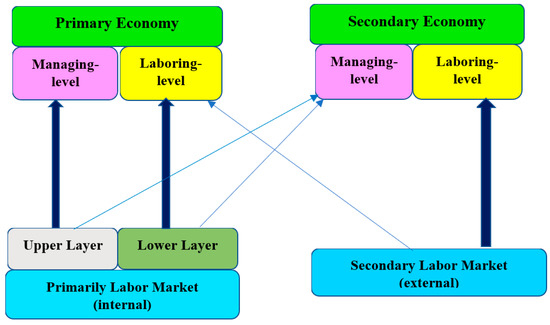

Piore [29] examines the economy’s evolution and the labor market segmentation. The technological and institutional structure of the primary sector of the economy requires and promotes employment structures in production and lower administrative departments, which we have called the lower layer of the primary labor market. Above this builds a pyramid top of predominantly administrative (upper) jobs in technical and administrative services. The necessarily variable and low division of labor and unstable technological and production structure in the secondary sector require and condition a predominantly administrative and secondary job structure. Beyond this basic scheme, various other classifications are possible. Often, “secondary workers” also find access to specific jobs in the primary sector (e.g., packers and transportation workers), or workers from the lower strata advance to secondary sector positions through further technical qualification and the acquisition of “general traits” (Figure 4).

This train of thought may be generalized as follows: On the part of the firm, there is a systematic allocation of different labor crisis groups to labor market segments. Such selective recruitment is rational from the firm’s point of view because the skills and behaviors required for the segments are particularly presupposed in the workers of specific population groups. This is a self-fulfilling expectation because the required behaviors and skills are at least partly generated or reinforced by the requirements of the job performed [30]. In the context of neoclassical labor market theory, this pattern of reasoning can be found in some models of statistical discrimination theory: the assumption is that employers cannot directly observe the aptitude of individual applicants for a particular type of job in hiring procedures. If they suspect this aptitude is lower in a particular population group than in others, they will tend to screen out that group and deny it access to that sub-labor market. As a result, people in that group also have no incentive to invest in their aptitude for those jobs since such investments are not adequately rewarded in the labor market. However, the very general terms ‘group’ and ‘aptitude’ suggest that these models are only concerned with the formal structure of the argument [31].

Figure 4.

The relationship between the economy and segmented market [32].

The segmentation literature proposes occupational typologies of varying scope, as opposed to the simple labor market dualism many authors still assume. Ultimately, the goal is always to move away from simple labor market dualism. In both internal and external segments, jobs tend to resemble a continuum of skills and wage levels to be described [33]. A central aspect of the literature on segmentation theory concerns the labor market behavior of migrant women as a marginalized group: from the point of view of companies, they were only considered for the relatively undemanding and precarious jobs in the external segment, as they were always assumed to be unreliable and to have a high turnover rate, and they also had low professional qualifications. On the other hand, they became used to these unstable working conditions, mainly because of the working conditions in the external segment itself [34].

Many studies attempt to explain the specifics of women’s work within the general framework of the segmentation theory described above [35,36,37]. However, they only use the division between internal and external labor markets, between permanent and marginal employees: women—together with other population groups such as young people or migrant workers—are predestined for jobs in the external segment. They are suitable as maneuvering masses for company employment policy because their alternative role as housewives and mothers means less resistance is expected in the event of redundancies. Conversely, it is not worthwhile for the company to invest in their qualifications because their long-term professional commitment appears too uncertain. In the words of neoclassical labor market theory, women remain predominantly outsiders in the labor market due to—from the company’s point of view—rational statistical discrimination in the selection of applicants for insider positions [38].

The feminist theory emphasizes the role of social norms governing the division of labor in the household as a source of segmentation. It is assumed that the traditional division of labor in the household puts women at a double disadvantage. Within the household, their work is unpaid and performed below market wages, while their participation in the labor market tends to be limited to activities that do not consistently lead to subsistence wages. Based on this double disadvantage, the different labor market experiences of male and female workers systematically work to the advantage of the former; this is reflected in occupational segregation and unequal access to training, job security, and employment-related benefits [39,40].

4. Methodology

The primary research approach is based on the documentary method. The documentary research method is considered a complete method to reinforce other qualitative methods in social science research. In this method, the researcher collects data about actors, events, and social phenomena using sources and documents [41,42].

In this study, based on the textual material (docs and reports) and thematically organized, a formulating and reflective interpretation is provided for an overview and comparison of selected passages (with emphasis on metaphors/ concepts). In formulating the interpretation, the researcher stays at the level of immanent meaning, i.e., WHAT has been said [41,42,43,44] is reformulated. This step serves to alienate the material and differentiate the thematic content (into main and subthemes), exclude any contextual knowledge, and include specifics of the studied in the reformulation (e.g., “immigrant women” or “access” as an expression for the labor market). The subsequent reflective interpretation of the material is the core of the documentary method. Here it is important to break away from the WHAT level of the text and focus on and describe the HOW, i.e., How [42,44], for example, is the “access of immigrant women to the European labor market” a concrete topic or problem that is dealt with by a person or a group. Therefore, special attention is paid to performance aspects, such as the arrangement of the actual documents and the concepts extracted from the collected data or text types. In two steps, the material is first interpreted sequentially (i.e., step by step) and then subjected to descriptive analysis (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Step to outputs in Documentary research (Source: Author’s conclusion).

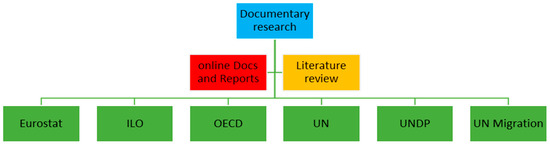

In the current study, the statistical research community incorporates various Literature and all documents and statistical reports published on the websites of EUROSTAT, ILO, OECD, UN, UNDP, and UN MIGRATION on labor market-related activities of migrants in Europe (Figure 6). The study refers to the period of the last two decades (2000–2022), during which the world has undergone significant changes both in the economic field and in the area of immigration.

Figure 6.

Statistical research community (Source: Research output).

The data analysis aims to connotatively describe the context of the labor market and the obstacles faced by migrant women in the Eurozone amid the COVID pandemic in terms of representative concepts. The keywords “migrant women,” “Europe,” “EU countries,” “covid,” “labor market,” and “employment” were used to search for documents and reports related to the objectives of the study. The result was 150 documents and reports, of which 30 documents and reports were selected as the most relevant. Analysis of the documents and reports examined revealed two main general themes, one related to challenges in the employment field and the other related to the significant decline in employment of immigrant women (Table 1). The following is a discussion of these themes.

Table 1.

Main themes and concepts as reviewing outputs (Source: Research output).

5. Remarks on Current Outcomes

5.1. Employment Challenges

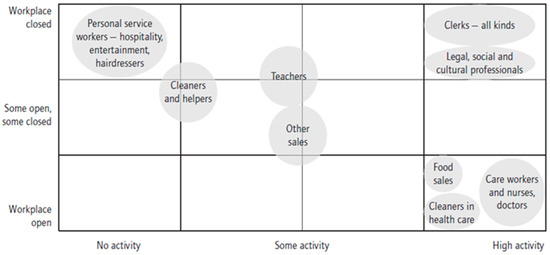

Across Europe, the economic stagnation caused by COVID is affecting different sectors very differently. In addition to manufacturing, many service sectors are disproportionately affected. Job losses primarily affect cleaning occupations, food and hospitality, and security and trade occupations. Workers who can work from home are far less affected by job losses. While demand increased in systemically important service occupations such as health care or food sales, workers in smaller firms and temporary employment were more affected by the containment measures [45]. The above-average employment of migrant women, especially in the affected sectors, such as catering, as well as their higher concentration in smaller firms and atypical employment, is, therefore, a possible explanation for the above-average increase in unemployment as a result of the COVID crisis [46].

Moreover, lockdown mainly affects manual and non-manual routine jobs and interactive non-routine jobs, i.e., jobs that can be done less efficiently in the home office. Immigrants are increasingly being hired for these jobs. If we take the skill level as a basis, the crisis substantially impacts helper jobs. People with immigrant backgrounds are more likely to work in system-relevant jobs. Still, surprisingly, these positions seem to be affected by job losses to a similar extent as non-system-relevant jobs. Ultimately, migrants are disproportionately affected by economic crises due to their below-average tenure and often unstable working conditions [47].

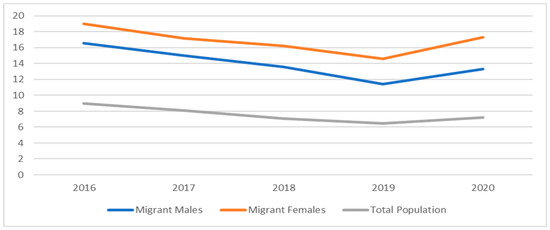

Unemployment rates (Figure 7) suggest that female third-country nationals still face many obstacles that may impede their overall integration. While unemployment rates for the overall population declined from an average of 9% in 2016 to nearly 7% in 2020 [6], third-country nationals as a whole lagged significantly, with average unemployment rates for female migrants remaining consistently higher than those for male migrants, and both experiencing more significant increases (+2%) between 2019 and 2020 than the overall population (less than 1%) [1,48].

Figure 7.

Average unemployment rates (%) 2016–2020 in Eurozone countries [6].

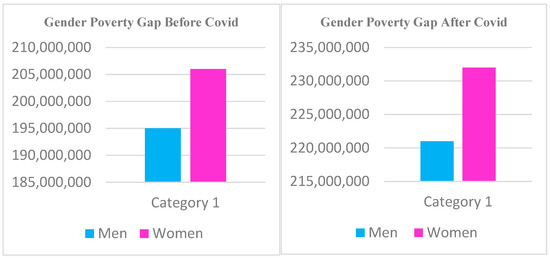

Several documents show that women are significantly more affected than men by the economic downturn resulting from the COVID crisis [49,50] (see Figure 8). In the spring of 2020, childcare facilities and schools were closed for several months, intensifying housework and childrearing, especially for women. This could likely have costly consequences, especially for women entering the labor market [51].

Figure 8.

The affection of the COVID Pandemic on Women’s Life [50].

Moreover, migrant women are generally expected to be more vulnerable to job losses, as they are mainly employed in helper, manual, and interactive non-routine jobs [24]. At the same time, they are more likely to work in atypical or precarious employment, for example, on a mini-job basis, and bear a more significant burden in terms of housework and childcare [4]. Exclusively marginal employment also automatically leads to the exclusion of the legal entitlement to a short-time allowance.

5.2. The Decline in the Employment and Multi-Facet Effects

The COVID crisis has made it clear that women perform exceptionally well: they make up the majority of workers in retail, nursing, and health professions. As such, they are the system maintainers in these difficult times, keeping society going. For the integration processes—in times of crisis, but also beyond—migrant women play a central role because they are considered essential multipliers and have a remarkable influence on the integration processes of their children. The promotion of women with a history of migration, therefore, not only serves to protect and empower women but is also an investment in the next generation. The European Union has repeatedly emphasized that the labor market integration of migrant women strengthens their individual capacities for self-preservation and those of their families. It also creates opportunities for cultural integration and boosts their self-confidence. Some recent studies presented above show that migrant women were particularly affected by the loss of their jobs due to the pandemic, mainly due to their above-average employment in specific sectors and activities [52,53].

During the COVID pandemic, this also contributed to the fact that they were subject to selective pressures. On the one hand, they often lost their jobs due to the collapse in demand in tourism, the hospitality industry, and, to some extent, commerce and body-related services; on the other hand, they were exposed to increased physical and psychological work pressure in the health and care sector and certain areas of commerce and the cleaning industry due to the unique demands of the pandemic. The switch to homeschooling also brought new challenges to the teaching profession, which employs an above-average number of women [8,46,49,54].

A high proportion of women engage in so-called system-maintaining activities, including many migrant women. As Statistics ILO’s COVID prevalence survey (2021) shows, 68% of employed women in the November 2020 survey could not work from home but had to go to their workplace. The state offered emergency care for the families particularly affected; there was also financial cushioning of the costs for families (e.g., a hardship fund for workers who lost their jobs or had to apply for short-term work due to the COVID crisis or a crisis fund for families who had already received unemployment benefits or emergency unemployment assistance before the crisis) as well as additional childcare days in case of illness (Figure 9).

Figure 9.

The share of migrant women in different sectors in 2020 [55].

Those women who have been able to use the home office have benefited from the experience in the long run, as more and more companies have realized that a culture of presence is not per se a prerequisite for successful work. However, there is a need to ensure that external, affordable, and high-quality childcare and school support for children is typical. To support workers in short-term crises, a statutory entitlement to particular care time has been introduced, allowing them to take up to 4 weeks of leave to care for children up to the age of 14, people with disabilities, or dependents in need of care [53].

Women of immigrant backgrounds are particularly likely to work in the industries most affected by the pandemic. In other economic services alone, which include cleaning services and temporary employment, 45% of employed women were foreigners in 2020; in accommodation and food services, the share of foreign women was equally high. In agriculture, almost half of female employees are also foreigners. But in so-called system-maintaining activities, such as teaching and education, the share of foreign women was also above average at 20%, compared to 18.7% of total female employment in 2020 (Table 2).

Table 2.

Employed immigrant women in different sectors (Eurozone) [2].

The impact of the COVID crisis on women’s access to the labor market, especially migrant women, makes it clear that women will only have more stable employment opportunities if they broaden their professional orientation. However, the COVID crisis has also shown that the professions that are often carried out by women (health/nursing/education), although systemically relevant, will only continue to be attractive in the future if working conditions are suitably attractive. This could additionally support the realization of equality.

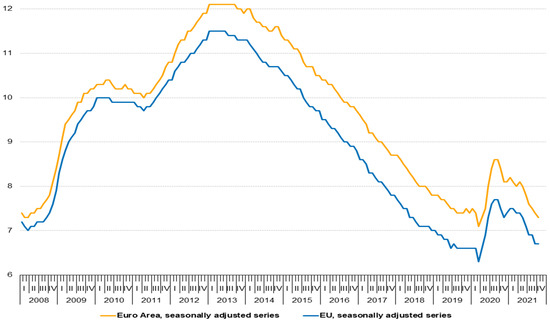

Based on Eurostat, the COVID effect for 2021, i.e., the difference in the change in the number of unemployed between the years 2008 and 2021, shows a significant decrease in unemployment in all working age categories, taking into account all persons potentially available to the Euro-area labor market (Figure 10).

Figure 10.

Unemployment rates, EU and EA (2008–2021) [6].

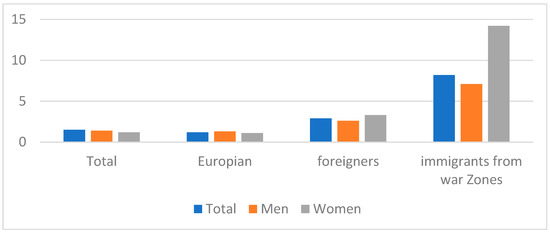

According to ILO data, the COVID effect in 2020 increased by 1.4 percentage points for all groups of people and by about 7 percentage points for people from countries at war and in crisis. Gender analysis also shows that foreigners, particularly female migrants or citizens from the eight main countries of origin of migrants (MENA), are significantly more affected by the crisis in terms of access to the labor market. Thus, the unemployment rate of female migrants in relation to their employment increased by a factor of 2 compared to male nationals from migrants’ countries of origin and by a factor of 14 compared to women with European nationality (Figure 11).

Figure 11.

Unemployment for several working-age groups Based on Gender and Nationality in Euro-area [52].

It should be noted, however, that the above-average increase in this indicator for people from migrants’ countries of origin is due not only to job losses but also to the phasing out or termination of policies. Although this observation provides a much more conservative estimate, especially for people from migrant countries, it is also clear here that people from migrant countries are disproportionately affected by the COVID crisis (Figure 6). While the stronger negative effect found above is no longer observed for migrant women, compared to migrant men, they are still more affected by the containment measures than other foreign women and native European women [23].

It should be analyzed whether the pandemic led to a retraditionalization of gender-specific roles and division of labor in Europe. In the absence of valid data, it cannot be stated whether the gender differences in housework and family work have increased. However, related European surveys indicate that the differences in housework and family work among families with children under 16 years of age became smaller in the 2020 pandemic. According to these figures, 65 % of men did more family work during the lockdown than before the COVID crisis [56].

Generally, a gender-equitable distribution of tasks in the close social sphere works better, especially in partnerships with an egalitarian conception of family and relationship. For them, the patriarchal gender order plays a lesser role. Socio-cultural milieus and cultural ideals about gender roles influence women’s choice of occupation, biography, and career, as well as their fundamental decision to seek part-time or full-time employment and to combine this with family responsibilities. Personal attitudes and norms are more important than educational attainment or financial factors. High part-time rates among employed migrant women and low wages also lead to various forms of dependence on spouses and other family members. Hence, a self-determined lifestyle is often not or hardly possible [10].

Traditional gender roles prepare the ground for unequal power imbalances in relationships and family structures and lead to economic dependencies. However, some studies on the lived experience of migrant women show that freedom, opportunities for development, and an egalitarian attitude towards partnerships in mainstream society open up a new perspective for many, which has a positive impact on their self-image [52,57]. While these opportunities are overwhelmingly liberating for women, they can be intimidating for male members of a culturally patriarchal milieu. Gender segregation is one of the “orientation values” that privilege and prefer men from patriarchal milieus as long as they submit to the collectivist dictates of communities and prove their loyalty. These different perceptions of gender roles and freedoms in mainstream society represent a neuralgic point in developing the potential for violence, as breakouts from traditional gender roles are sanctioned by the family and/or the community.

According to recent estimates from WHO, approximately 22% of women in the European Region who have ever been in a relationship have experienced sexual and/or physical violence at the hands of a partner, and approximately 5% of women over the age of 15 have experienced sexual violence at the hands of another partner [58]. A survey of experts from various aid and counseling institutions in direct contact with migrant women affected by violence in the course of their work, such as representatives of women’s shelters, violence protection centers, associations, and women’s and migrants’ counseling centers, revealed that domestic violence has also increased in families with a migration background due to isolation and distance regulations or has been exacerbated by cramped living conditions and social isolation. According to the study’s authors, the pandemic makes it more difficult to break out of violent relationships [59].

Dismissal and loss of job due to poor access to the labor market and financial dependence on the partner are some of the main reasons why migrant women do not report violence and remain in violent relationships. Fear, lack of self-confidence, and traditional role models prevent migrant women from achieving freedom and leading self-determined life. General insecurity and the economic crisis resulting from the COVID pandemic exacerbate this problem. In addition, for many victims of violence, the shame and fear of not conforming to the traditional role model of women and the possibility of continuing to be persecuted and punished if they leave the community play a crucial role. These specific challenges make it even more difficult for affected migrant women to turn to women’s counseling centers and seek an exit from violent relationships [60]. As there is generally less insight into people’s family situations due to the pandemic, it is to be feared that migrant women from traditionally shaped milieus will be more controlled by their male family members and restricted in their freedom of movement. Those affected are hesitant to turn to counsel centers out of fear and insecurity. The United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) predicts that the COVID pandemic will increase violence against women, child marriage, and genital mutilation worldwide by 2030 [61]. In addition to the rise in violence against women, it has also been observed since the beginning of the pandemic that young people, in particular, both with and without an immigrant background, repeatedly choose violence as an outlet in the European and international context [62].

6. Conclusions

An Intersectional Overview

Migrant women face additional barriers to accessing the labor market after arriving in one of the European host countries compared to migrant men and boys, as they often face structural barriers related to being both a migrant and a woman, including gender-specific barriers in their communities or host society [63,64]. Migrant women appear as family members rather than workers. In this case, they may be counted out from labor market policies upon arrival or afterward. As a result, they are excluded from the labor market or have limited access to it and promising opportunities. Such a condition, combined with family responsibilities, childcare, lack of professional networks, and inadequate knowledge of the language [65] and context of the host country, means that many migrant women are often employed in low-skilled jobs, which are usually positions that are culturally devalued [19,66].

According to the OECD, 26 percent of migrant women in Eurozone countries are employed in low-skilled positions, and Euro industries are more likely to hire migrant women in medium- and low-skilled positions. The gender gap in unemployment rates is exceptionally high among female migrants in Eurozone countries, at 63%, compared with 83.9% for their male counterparts. Many of these inequalities and discriminations have been exacerbated by the COVID pandemic. For example, in many European countries, migrant women and migrant workers, in general, have been excluded from government support measures related to the cow pandemic. In addition, many barriers remain arising from immigration and labor laws that result in the exclusion of many migrant workers, particularly women migrants, from programs that facilitate access to the labor market [3,63,67,68]. Many migrant women have part-time jobs in the host country or work in the service sector, such as in restaurants, hospitals, and nursing homes. During the COVID pandemic, many of these women were on the front lines of layoffs in the early stages of the pandemic, forcing them to stay at home to care for children and run the household without financial resources. For example, ethnic minority migrant women are more at risk in the United Kingdom than native-born women during the COVID pandemic (14% vs. 12%) [69]. In general, migrant women live in a precarious situation in the labor market, exacerbated by the COVID pandemic [59,70,71].

According to segmentation theory, migrant women can be considered as a marginal population of a larger periphery that includes different types of native women and men, as well as migrants in Euro countries. With regard to migrant women’s access to the labor market, the COVID pandemic policy must consider two systems of privilege and discrimination within the segmented market paradigm: gendered racism and capitalism. These two systems influence the labor market paradigm in terms of economic context and gender. Capitalism, especially late capitalism, also discriminates by scapegoating migrants when it comes to access to the labor market. It creates inequality and economic hardship. One of the apparent characteristics of capitalism is that there has never been a homogeneous working class.

On the contrary, workers have always had different cultural and social backgrounds, ambitions, and life strategies. In the workplace, employers have treated people as bearers of labor power but, at the same time, have divided the workforce by gender, race, ethnicity, age, origin, and legal status. In different eras, terms such as unfree labor, sexism, racism, discrimination, precarity, and denial of human and workers’ rights have been used by critics to characterize these processes. Nevertheless, at the core of the capitalist paradigm are the mechanisms of differentiation that lead to inequality and divisions among working people. Moreover, these mechanisms have been crucial at every stage of capitalist development, including the most recent, the neoliberal global labor market [72,73]. In this sense, labor has value only if it can be valued with money. The monetization of labor leads to domestic work being placed in the class of non-monetized labor and thus not included in the family’s economy. In such a neoliberal global market, the OECD has found that migrant women generally have less favorable labor market outcomes, both in absolute terms and compared to children of natives of the same gender [3,54].

In feminist literature, two main points of view on the reality of capitalism are held. First, capitalism functions through the transformation of wage labor into value and profit; in parallel with capitalism, patriarchy functions through the appropriation of women’s unpaid labor and energy to generate male power [74]. Both cases concern men’s control and the accumulation of women’s creativity, labor, and energy. Two causes of discrimination against women are their position in capitalist production (site of class domination) and their position in the family (site of gender domination). Historically, patriarchal social structures preceded the capitalist economic system and, at the same time, created the basis for its development outside the world of work (capitalism grew on patriarchy). Some authors describe the relationship to each other as quite conflictual because the logic of capital is gender-blind. Women are worse off primarily because capitalism is embedded in patriarchal social structures [75]. As a result, migrant women face higher levels of insecurity and have less access to the labor market. In addition, gender stereotypes exacerbate the status quo: 52% of men aged 16 to 19 and 54% of men aged 20 to 34 agree with the statement that “women should work less and spend more time taking care of their families,” according to recent findings from the UN Women [76].

Such a broad view of migrant women’s labor market access in a segmented market of a European country in the wake of the COVID pandemic portrays them as externalizers (low-skilled workers, e.g., in cleaning, restaurants, or other service sectors). Let’s make a comparison here so that internalizers (workers with high skills, e.g., in administration and emerging professions) see themselves as in control of the situation and believe that their efforts will lead to the desired results. It predicts that internalizers are more motivated than externalizers. Internalizers are significantly more engaged in their work, feel less alienated, and are more satisfied with their jobs. They are less likely to quit their jobs, presumably because they feel more engaged and motivated in their work environment. In fact, highly engaged individuals have significantly lower absenteeism and turnover rates, characteristics that are likely to be associated with highly motivated employees [34,77,78]. The fact that migrant women are such an externalizer in the segmented labor market of Euro countries leads migrant women to become almost disillusioned. On the other hand, migrant women take on the burden of housework and thus withdraw from their career advancement opportunities, making the dualism of disillusionment and housework a recurring dilemma in the lives of migrant women. This dilemma would be exacerbated in the wake of the covid pandemic, as these women must always fear the risk of infecting family members. Moreover, in some cases, patriarchal backgrounds strongly impact migrant women’s access to the labor market (mainly Muslim migrant women from the MENA region). Regression results from the most recent study in Europe show that employment of immigrants from Muslim countries varies more with the characteristics studied (incredibly individual religiosity) (R2 = 0.16) than the employment of immigrants from Christian countries (R2 = 0.06) [79].

According to Sengenberger and Wilkinson [80], segmented labour markets are based on power relations; on the other hand, gender researchers have long pointed out that gender racism is intertwined with other power relations-as in our discussion with capitalism and segmented labour markets [81]. Race and gender do not add up but intertwine, resulting in specific multiple discrimination [82]. Other scholars also point to the link between race and gender as an independent form of discrimination [83,84,85]. Racism is to be understood as a social relationship and not as individual misbehavior of individuals [86]. There are different types of racism, which can be distinguished according to the conditions under which they arose and according to their form and function, e.g., anti-Muslim racism and anti-Black racism [87,88]. According to Hall [89], racism contains three basic concepts: first, it does not refer to pre-existing objects but constructs them. The concept of the Other is represented as a homogeneous group along with biologizing and/or culturalizing pejorative attributions. Second, the construction legitimizes exclusionary practices toward these groups that keep racialized people out of economic, political, social, and cultural resources. Third, a majority society identity is enabled by the apparent differences between the majority society and the Other. Regarding gendered racism, Hall’s understanding of racism can also be partially applied to power relations in the context of gender, which relegate subjects to a socially inferior place through naturalizing assignments along seemingly visible characteristics [90]. Women are ascribed natural characteristics qua gender to devalue them and barely legitimize their social disadvantage. In this way, the internal differences are lost sight of the complex relationships, modes of existence, and experiences that are empirically the norm [91].

Gendered racism became evident against the backdrop of current social policies in Eurozone countries. For people in migration contexts, political regulations of migration, access to the labor market, and gender are particularly relevant [92]. Migration realities are socially produced not only through ethnicized or racialized but also through gendered processes. Racism produces itself in relation to present social conditions. This makes it necessary to speak of racism in the plural and to assume that it changes historically [93]. The results of the study show that migrant women are pushed either into the private sector or into precarious employment amid the COVID pandemic devalued by women. Applying labor market policies to migrant contexts promotes the importance of gendered racism and the associated mechanisms of inclusion and exclusion in the labor market [94]. Spatial segregation [95] in the context of the labor market did not merely serve to protect immigrant women from racism, as inevitably became the practice in the COVID Pandemic period. Although spatial segregation was necessary in part because of hostility, racism is not named but negated.

On the one hand, racism remains linked to other members of the majority society; on the other hand, the continuation of such a separation/divergence (cf. COVID Lockdown) [96] declares the everyday experiences of racism by migrant women to be untrue and makes them invisible. Ultimately, gendered racism remains an uncomfortable feeling because it is difficult (not only) for women to account for the racism they have experienced in the context of migration. Moreover, racism is clearly gendered: feelings are associated with femininity and often have negative connotations. Actions or reactions based on feelings are often perceived as illegitimate. (Female) feelings are constructed as the opposite of (male) reason. Feelings are not subject to any structure or system; they do not seem to relate to social conditions [97,98].

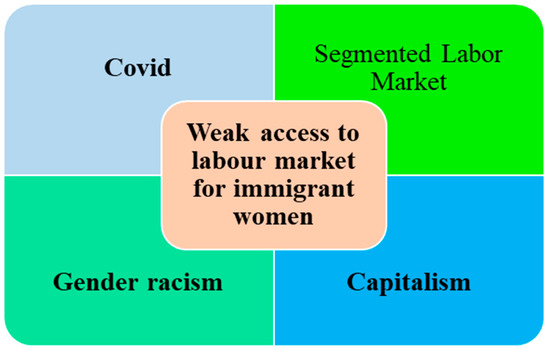

Against this backdrop, theorizing the intersection of multiple dimensions of inequality among migrant women in Europe, focusing on labor market access amid the covid pandemic, seems to pass through a multidimensional analysis framework. However, such a framework is achieved through an intersectional analysis that does not look at a single feature of human life but rather points to intersecting and interacting systems and structures of a society that shape a phenomenon. Intersectional approaches to migrant women’s access to the European labor market in the midst of the covid pandemic address the intertwining of covid (with a focus on migrant women) with other current power structures [99] as we have paid for a segmented labor market, capitalism, and gendered racism (Figure 12). The points resulting from this overlap may refer to any factor at the same time.

Figure 12.

The intersection of obstacles for migrant women in accessing the Euro labor market amid the COVID Pandemic (Source: Author’s conclusion).

The labor market segmentation can be used to explain why companies make it difficult for migrant women to access the upper part of the internal/external labor market segment. This is where their commonality with other so-called “problem groups” of the labor market is exhausted [100]. It is evident that the labor market segmentation by gender is in contradiction with different segmentation patterns and therefore requires additional explanations. However, in the segmentation paradigm, most jobs are tailored to male or female workers, i.e., they are specified by the job content and other explicit and implicit contractual elements in such a way that only applicants of one sex are eligible. This is true even when there are no legal requirements (e.g., health and safety laws) prohibiting the hiring of women and when there are no formal qualifications required that are only offered by men or only offered by women [101]. This is the honest answer to why many migrant women in Europe, such as Filipino or Arab women, work in the cleaning or care sector. Many of these women were laid off after COVID or, in some cases, were under high pressure to perform [102]. Such a situation is consistent with more pronounced segmentation in Eurozone countries with high youth unemployment and the capitalist market structure that divides jobs by gender, race, origin, age, etc., as a strategy of a neoliberal global market [103].

In a capitalist/segmented market economy, businesses and private employers assume that women are worth less than men as workers [81]. Mothers are supposed to spend time caring for young children. Therefore, they are considered less reliable workers and are paid less. Women’s domestic work has no value in the formal economy [104]. In such a context, the market can increase its profits because women give birth to and raise the next generation of workers and taxpayers for free. This is especially true for the immigrant community and for immigrant women (Especially from the MENA region) [105], who grow up in a profoundly patriarchal culture that assumes it is a woman’s job to bear and raise a child. So, it is a vicious cycle because it perpetuates the assumption that women are less reliable workers. For most immigrant women with a high birth rate in European countries, the role of the family is heavier than that of the labor market, so many workers shape their attitudes towards immigrant women in such a way that in times of crisis, such as the COVID, these women are the ones who give the order to be fired, simultaneously, such a prism, could make access to the labor market more difficult for migrant women (highly skilled or not) [6,54].

However, the labor market participation of men and women in the EU also differs outside the migration context. In addition to a labor market that is strongly gendered both vertically and horizontally and the care work still performed much more frequently by women, the regulation of women’s and mothers’ employment is contradictory [45,106].

On the one hand, women and mothers are to be activated for the labor market in the sense of an adult worker model; on the other hand, the conditions under which they must do so remain largely undisputed. While mothers are addressed as economic subjects, fathers are hardly mentioned as providers. At the same time, the family breadwinner model remains flanked in Eurozone countries, increasingly generating intersectional inequalities within gender groups and inevitably having gendered consequences for migrants [107]. Such a condition tends to worsen when it coincides with the covid pandemic, as it reinforces gendered racism in an intersection with the power relations of capitalism and the segmented labor market.

In such a context, migrant women are juxtaposed as “other” and native women as “normal.” At the very least, the notion of the broader labor market in Europe of migrant women (e.g., Filipino or Arab women) [102] follows such a stereotype of the “other” versus the “normal,” and labor market policies also follow this as a rule of thumb. Moreover, some empirical studies emphasize that gendered racism extends even into the second generation [83]. Indeed, gendered racism in the labor market is related to the human capital of immigrant women. It does not matter to migrant women whether they are low, medium, or highly skilled, but the social situation does. In addition, gender-based racism would affect the economic outcome of migrant women in Europe. These women “feel it” [97] and voluntarily settle for lower earnings and a lower position compared to their host country’s native counterparts. We can call this point “gender racism against oneself”, because migrant women reflect the effects of such discrimination on themselves on their requirements in the labor market and reduce them under the influence of this feedback. This is why migrant women are discriminated against or pressured to lose their jobs in situations like the COVID pandemic, regardless of their skill level.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- European Migration Network Study. Integration of Migrant Women. European Commission. 2022. Available online: https://home-affairs.ec.europa.eu/system/files/2022-09/EMN_STUDY_integration-migrant-women_23092022.pdf (accessed on 18 July 2022).

- Eurostat. EU Population in 2020: Almost 448 Million. Eurostat. 2020. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/documents/2995521/11081093/3-10072020-AP-EN.pdf/d2f799bf-4412-05cc-a357-7b49b93615f1 (accessed on 10 July 2022).

- OECD. What Is the Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Immigrants and Their Children? OECD. 2020. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/coronavirus/policy-responses/what-is-the-impact-of-the-covid-19-pandemic-on-immigrants-and-their-children-e7cbb7de/ (accessed on 13 November 2022).

- European Parliament. Precarious Employment in Europe: Patterns, Trends and Policy Strategies. 2016. Available online: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/STUD/2016/587285/IPOL_STU (accessed on 8 October 2022).

- Bevelander, P. The Employment Status of Immigrant Women: The Case of Sweden. Int. Migr. Rev. 2005, 39, 173–202. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/27645480 (accessed on 24 August 2022). [CrossRef]

- Eurostat. Translate Migrant Integration Statistics—Labour Market Indicators. Statistics Explained. 2021. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Migrant_integration_statistics_%E2%80%93_labour_market_indicators (accessed on 12 October 2022).

- ILO. Gender Equality at the Heart of Decent Work. 2009. Available online: https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/@ed_norm/@relconf/documents/meetingdocument/wcms_105119.pdf (accessed on 10 May 2022).

- ILO. Global Employment Trends for Youth 2020. 2020. Available online: https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---dgreports/---dcomm/---publ/documents/publication/wcms_737648.pdf (accessed on 8 May 2022).

- Lodovici, M.S. Making a Success of Integrating Immigrants in the Labour Market. 2010. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/social/BlobServlet?docId=8218&langId=en (accessed on 12 August 2022).

- Cerrato, J.; Cifre, E. Gender Inequality in Household Chores and Work-Family Conflict. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 1330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marks, J.; Bun, L.C.; McHale, S.M. Family Patterns of Gender Role Attitudes. Sex Roles 2009, 61, 221–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pailhé, A.; Solaz, A.; Stanfors, M. The Great Convergence? Gender and Unpaid Work in Europe and the United States. 2020. Available online: https://www.ed.lu.se/media/ed/papers/working_papers/LPED_2020_1.pdf (accessed on 27 September 2022).

- European Parlemant. Integration of Refugees in Austria, Germany and Sweden: Comparative Analysis. 2018. Available online: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/STUD/2018/614200/IPOL_STU (accessed on 5 October 2022).

- Reino, M.F.; Rienzo, C. Migrants in the UK Labour Market: An Overview. 2021. Available online: https://migrationobservatory.ox.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/COMPAS-Briefing-Migrants-in-the-UK-labour-market-an-overview.pdf (accessed on 15 October 2022).

- ILO. ILO Global Estimates on Migrant Workers: Results and Methodology; Special Focus on Migrant Domestic Workers. 2015. Available online: https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---dgreports/---dcomm/documents/publication/wcms_436343.pdf (accessed on 4 August 2022).

- OECD. How Are Refugees Faring on the Labour Market in Europe? Available online: https://ec.2016.europa.eu/social/BlobServlet?docId=16130&langId=en (accessed on 29 June 2022).

- Calmfors, L.; Gassen, N.S. Integrating Immigrants into the Nordic Labour Markets. Nordisk Ministerråd. 2019. Available online: https://norden.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:1317928/FULLTEXT01.pdf (accessed on 24 August 2022).

- Kil, T.; Neels, K.; Wood, J.; de Valk, H. Employment After Parenthood: Women of Migrant Origin and Natives Compared. Eur. J. Popul. = Rev. Eur. Demogr. 2017, 34, 413–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amo-Agyei, S. The Migrant Pay Gap: Understanding Wage Differences between Migrants and Nationals. ILO. 2020. Available online: https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---ed_protect/---protrav/---migrant/documents/publication/wcms_763803.pdf (accessed on 7 September 2022).

- ILO. ILO Global Estimates on International Migrant Workers Labour Migration; Results and Methodology. 2017. Available online: https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---dgreports/---dcomm/---publ/documents/publication/wcms_652001.pdf (accessed on 21 August 2022).

- ILO. Changing Attitudes and Behaviour towards Women Migrant Workers in ASEAN: Technical Regional Meeting. 2018. Available online: https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---asia/---ro-bangkok/documents/publication/wcms_715939.pdf (accessed on 15 August 2022).

- ILO. The Social Construction of Migrant Care Work. 2019. Available online: https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---ed_protect/---protrav/---migrant/documents/publication/wcms_674622.pdf (accessed on 11 May 2022).

- UN Migration. World Migration Report 2020. Available online: https://publications.iom.int/system/files/pdf/wmr_2020.pdf (accessed on 5 September 2022).

- ILO. Non-Standard Employment around the World. 2016. Available online: https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---dgreports/---dcomm/---publ/documents/publication/wcms_534326.pdf (accessed on 20 June 2022).

- Reich, M.; Gordon, D.M.; Edwards, R.C. A Theory of Labor Market Segmentation. Am. Econ. Rev. 1973, 63, 359–365. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1817097 (accessed on 2 July 2022).

- Doeringer, P.B.; Piore, M.J. Internal Labor Markets, Technological Change, and Labor Force Adjustment; D.C. Heath and Company: New York, NY, USA, 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Piore, M.J. On-the-Job Training in the Dual Labor Market: Public and Private Responsibilities in On-the-Job Training of Disadvantaged Workers; Industrial Relations Research Association: Champaign, IL, USA, 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Kalleberg, A.L.; Sorensen, A.B. The Sociology of Labor Markets. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 1979, 5, 351–379. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2945959 (accessed on 14 November 2022). [CrossRef]

- Piore, M.J. Notes for a Theory of Labor Market Stratification. 1972. Available online: https://dspace.mit.edu/handle/1721.1/64001 (accessed on 10 October 2022).

- Aigner, D.J.; Cain, G.G. Statistical Theories of Discrimination in Labor Markets. ILR Rev. 1977, 30, 175–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexis, M. A Theory of Labor Market Discrimination with Interdependent Utilities. Am. Econ. Rev. 1973, 63, 296–302. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1817089 (accessed on 23 August 2022).

- Freiburghaus, D.; Schmid, G. Theorie Der Segmentierung von Arbeitsmärkten: Darstellung Und Kritik Neuerer Ansätze Mit Besonderer Berücksichtigung Arbeitsmarktpolitischer Konsequenzen. Leviathan 1975, 3, 417–448. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/23983963 (accessed on 10 September 2022).

- Massey, D.S.; Arango, J.; Hugo, G.; Kouaouci, A.; Pellegrino, A.; Taylor, J.E. Theories of International Migration: A Review and Appraisal. Popul. Dev. Rev. 1993, 19, 431–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darity, W.A.; Goldsmith, A.H. Social Psychology, Unemployment and Macroeconomics. J. Econ. Perspect. 1996, 10, 121–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauvin, J.P. Gender-Segmented Labor Markets and the Effects of Local Demand Shocks; Inter-American Development Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hori, H. Labor Market Segmentation and the Gender Wage Gap. Jpn. Labor Rev. 2009, 6. Available online: https://www.jil.go.jp/english/JLR/documents/2009/JLR21_hori.pdf (accessed on 14 May 2022).

- Waddoups, J.; Assane, D. Mobility and Gender in a Segmented Labor Market: A Closer Look. Am. J. Econ. Sociol. 1993, 52, 399–412. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3487464 (accessed on 16 October 2022). [CrossRef]

- Bettio, F.; Verashchagina, A. Gender Segregation in the Labour Market; Root Causes, Implications and Policy Responses in the EU. European Commission’s Expert Group on Gender and Employment (EGGE). 2009. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/social/BlobServlet?docId=3799&langId=en (accessed on 25 May 2022).

- Deakin, S. Working Paper No. 52, ‘Addressing Labour Market Segmentation: The Role of Labour Law’. 9 October 2013. Available online: https://www.ilo.org/ifpdial/information-resources/publications/WCMS_223702/lang--en/index.htm (accessed on 10 November 2022).

- Grimshaw, D.; Fagan, C.; Hebson, G.; Tavora, I. A new labour market segmentation approach for analysing inequalities. In Making Work More Equal; Manchester University Press: Manchester, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J.W. Research Design. Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches; SAGE Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Tight, M. Documentary Research in the Social Sciences; Sage Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Henn, M.; Weinstein, M.; Foard, N. A Critical Introduction to Social Research; SAGE: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Mogalakwe, M. The Use of Documentary Research Methods in Social Research. Afr. Sociol. Rev./Rev. Afr. Sociol. 2006, 10, 221–230. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/afrisocirevi.10.1.221 (accessed on 8 August 2022).

- European Commission. Women in the Labour Market—European Commission. European Commission. 2021. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/info/sites/default/files/european-semester_thematic-factsheet_labour-force-participation-women_en_0.pdf (accessed on 15 May 2022).

- ILO. World Employment and Social Outlook. 2020. Available online: https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---dgreports/---dcomm/---publ/documents/publication/wcms_734455.pdf (accessed on 7 May 2022).

- Jesline, J.; Romate, J.; Rajkumar, E.; George, A.J. The plight of migrants during COVID-19 and the impact of circular migration in India: A systematic review. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2021, 8, 231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ILO. World Employment and Social Outlook|Trends 2022. 2022. Available online: https://www2019.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---dgreports/---dcomm/---publ/documents/publication/wcms_834081.pdf (accessed on 11 June 2022).

- OECD. Women at the Core of the Fight against the COVID-19 Crisis. 2020. Available online: https://read.oecd-ilibrary.org/view/?ref=127_127000-awfnqj80me&title=Women-at-the-core-of-the-fight-against-COVID-19-crisis&_ga=2.250024134.1514930723.1638746954-1587338467.1638457788 (accessed on 28 August 2022).

- UN Women. COVID-19 and Its Economic Toll on Women: The Story Behind the Numbers. 2020. Available online: https://www.unwomen.org/en/news/stories/2020/9/feature-covid-19-economic-impacts-on-women (accessed on 18 October 2022).

- Cain Miller, C. The Pandemic Created a Child-Care Crisis. Mothers Bore the Burden. The New York Times. 17 May 2021. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2021/05/17/upshot/women-workforce-employment-covid.html (accessed on 10 September 2022).

- ILO. COVID-19 and the World of Work. Seventh Edition. 2021. Available online: https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/@dgreports/@dcomm/documents/briefingnote/wcms_767028.pdf (accessed on 10 May 2022).

- WGEA (Workplace Gender Equality Agency). Gendered Impacts of COVID-19. 2020. Available online: https://www.wgea.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/Gendered%20impacts%20of%20COVID19_0.pdf (accessed on 10 October 2022).

- OECD. Labour Market Outcomes of Immigrants and Integration Policies in OECD Countries. International Migration Outlook 2020|OECD iLibrary. 2020. Available online: https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/sites/0c0cc42a-en/index.html?itemId=%2Fcontent%2Fcomponent%2F0c0cc42a-en (accessed on 12 October 2022).

- Rubery, J.; Tavora, I. The COVID-19 crisis and gender equality: Risks and opportunities. In Social Policy in the European Union: State of Play; UNDP: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 71–96. [Google Scholar]

- Derndorfer, J.; Disslbacher, F.; Lechinger, V.; Mader, K.; Six, E. Home, sweet home? The impact of working from home on the division of unpaid work during the COVID-19 lockdown. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0259580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. Women on the Move; Migration, Care Work and Health. 2017. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/259463/9789241513142-eng.pdf (accessed on 24 August 2022).

- WHO. Women and Children Experienced Higher Rates of Violence in Pandemic’s First Months. 2021. Available online: https://www.euro.who.int/en/health-topics/disease-prevention/violence-and-injuries/news/news/2021/11/women-and-children-experienced-higher-rates-of-violence-in-pandemics-first-months (accessed on 15 September 2022).

- European Institute for Gender Equality. Gender Equality and the Socio-Economic Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic. European Institute for Gender Equality. 26 May 2021. Available online: https://eige.europa.eu/publications/gender-equality-and-socio-economic-impact-covid-19-pandemic (accessed on 12 October 2022).

- United Nation Migration. Taking Action against Violence and Discrimination Affecting Migrant Women and Girls. 2018. Available online: https://www.iom.int/sites/g/files/tmzbdl486/files/2018-07/violence_against_women_infosheet2013.pdf (accessed on 12 August 2022).

- UNFPA (United Nations Population Fund). Millions more Cases of Violence, Child Marriage, Female Genital Mutilation, and Unintended Pregnancy Expected Due to the COVID-19 Pandemic. 2020. Available online: https://www.unfpa.org/news/millions-more-cases-violence-child-marriage-female-genital-mutilation-unintended-pregnancies (accessed on 6 September 2022).

- ESCAP (Moving Forward Together of United Nations). The COVID-19 Pandemic and Violence Against Women in Asia and the Pacific. 2021. Available online: https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/SDD_Policy_Paper_Covid-19-VAW.pdf (accessed on 8 October 2022).

- Foley, L.; Piper, N. COVID-19 and Women Migrant Workers: Impacts and Implications. International Organization for Migration. 2020. Available online: https://publications.iom.int/books/covid-19-and-women-migrant-workers-impacts-and-implications (accessed on 13 November 2022).

- UNICEF. Situational Analysis of Women and Girls in the Middle East and North Africa. UNICEF Middle East and North Africa. 1 November 2021. Available online: https://www.unicef.org/mena/reports/situational-analysis-women-and-girls-middle-east-and-north-africa (accessed on 10 October 2022).

- Ennser-Kananen, J.; Pettitt, N. I want to speak like the other people”: Second language learning as a virtuous spiral for migrant women? Int. Rev. Educ. 2017, 63, 583–604. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/44980150 (accessed on 12 August 2022). [CrossRef]

- Bolzani, D.; Crivellaro, F.; Grimaldi, R. Highly skilled, yet invisible. The potential of migrant women with a stemm background in Italy between intersectional barriers and resources. Gend. Work. Organ. 2021, 28, 2132–2157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, K.; Piper, N.; Mudaliar, S. Locked Down and in Limbo: The Global Impact of COVID-19 on Migrant Worker Rights and Recruitment. Fair Recruitment: Locked Down and in Limbo: The Global Impact of COVID-19 on migrant worker rights and Recruitment. 22 November 2021. Available online: https://www.ilo.org/global/topics/fair-recruitment/publications/WCMS_821985/lang--en/index.htm (accessed on 13 November 2022).

- Schieckoff, B.; Sprengholz, M. The labor market integration of immigrant women in Europe: Context, theory, and evidence. SN Soc. Sci. 2021, 1, 276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. The Unequal Impact of COVID-19: A Spotlight on Frontline Workers, Migrants, and Racial/Ethnic Minorities. OECD. 2022. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/coronavirus/policy-responses/the-unequal-impact-of-covid-19-a-spotlight-on-frontline-workers-migrants-and-racial-ethnic-minorities-f36e931e/ (accessed on 11 October 2022).

- European Institute for Gender Equality. Education and Training of Migrant Women: What Works? European Institute for Gender Equality. 13 May 2020. Available online: https://eige.europa.eu/news/education-and-training-migrant-women-what-works (accessed on 12 October 2022).

- European Institute for Gender Equality. COVID-19 Wave of Violence against Women Shows EU Countries Still Lack Proper Safeguards. 2021. Available online: https://eige.europa.eu/news/covid-19-wave-violence-against-women-shows-eu-countries-still-lack-proper-safeguards (accessed on 15 May 2022).

- Castles, S. Migration, Precarious Work, and Rights: Historical and Current Perspectives. In Migration, Precarity, & Global Governance Essay; Schierup, C.-U., Ed.; OXFORD University Press: Oxford, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Gimenez, M.E. Global Capitalism and Women: From Feminist Politics. In Marx, Women, and Capitalist Social Reproduction Marxist Feminist Essays; Haymarket Books: Chicago, IL, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Weeks, K. The Problem with Work: Feminism, Marxism, Antiwork Politics, and Postwork Imaginaries; Duke University Press: Durham, NC, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Mies, M. Patriarchy and Accumulation on a World Scale: Women in the International Division of Labour; Bloomsbury Academic: London, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- UN Women. Un Women Reveals Concerning Regression in Attitudes towards Gender Roles during Pandemic in New Study. UN Women—Headquarters. 22 June 2022. Available online: https://www.unwomen.org/en/news-stories/press-release/2022/06/un-women-reveals-concerning-regression-in-attitudes-towards-gender-roles-during-pandemic-in-new-study (accessed on 12 October 2022).

- ILO. Women and Men Migrant Workers: Moving towards Equal Rights and Opportunities. 2014. Available online: https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/@dgreports/@gender/documents/publication/wcms_101118.pdf (accessed on 12 May 2022).

- Sharp, M. The labour market impacts of female internal migration: Evidence from the end of apartheid. Reg. Sci. Urban Econ. 2021, 91, 103624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blekesaune, M. Employment among female immigrants to Europe. Acta Sociol. 2021, 64, 331–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sengenberger, W.; Wilkinson, F. ‘Globalization and labor standards,’ In Managing the Global Economy; Michie, J., Smith, J.G., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Hartmann, H. Capitalism, Patriarchy, and Job Segregation by Sex. Signs 1976, 1, 137–169. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3173001 (accessed on 2 August 2022). [CrossRef]

- Crenshaw, K. Mapping the Margins: Intersectionality, Identity Politics, and Violence against Women of Color. Stanf. Law Rev. 1991, 43, 1241–1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Browne, I.; Misra, J. The Intersection of Gender and Race in the Labor Market. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 2003, 29, 487–513. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/30036977 (accessed on 26 May 2022). [CrossRef]

- Smith, R.A. Race, Gender, and Authority in the Workplace: Theory and Research. Annu. Rev. Social. 2002, 28, 509–542. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3069251 (accessed on 22 October 2022). [CrossRef]

- Hogan, R. Class, Race, and Gender Inequality. Race Gend. Cl. 2001, 8, 61–93. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/41674972 (accessed on 19 September 2022).

- Salter, P.S.; Adams, G.; Perez, M.J. Racism in the Structure of Everyday Worlds: A Cultural-Psychological Perspective. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 2018, 27, 150–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, J.E. Islamophobia, Muslimophobia or racism? Parliamentary discourses on Islam and Muslims in debates on the minaret ban in Switzerland. Discourse Soc. 2015, 26, 562–586. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/26376401 (accessed on 10 September 2022). [CrossRef]

- Hill Collins, P. Black Sexual Politics: African Americans, Gender, and the New Racism, 1st ed.; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, S. Race Articulation and Societies Structured in Dominance. 1980. Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000040979 (accessed on 14 November 2022).

- Alexander, C. Stuart hall and ‘race’. Cult. Stud. 2009, 23, 457–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacKinnon, C.A. Toward a feminist theory of the State; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- ENAR. Racism & Discrimination in Employment in Europe 2013–2017. European Website on Integration. 2018. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/migrant-integration/library-document/enar-shadow-report-racism-discrimination-employment-europe-2013-2017_en (accessed on 14 November 2022).

- Bonilla-Silva, E. Rethinking Racism: Toward a Structural Interpretation. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1997, 62, 465–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabeer, N.; Razavi, S.; van der Meulen Rodgers, Y. Feminist economic perspectives on the COVID-19 pandemic. Fem. Econ. 2021, 27, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, M.R. “Race,” Space, and Power: The Survival Strategies of Working Poor Women. Ann. Assoc. Am. Geogr. 1998, 88, 595–621. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2564094 (accessed on 22 May 2022). [CrossRef]

- Powell, C. Color of Covid and Gender of Covid: Essential Workers, not Disposable People. Yale Law School Legal Scholarship Repository. 25 November 2021. Available online: https://openyls.law.yale.edu/handle/20.500.13051/7137 (accessed on 14 November 2022).

- Bonilla-Silva, E. Feeling Race: Theorizing the Racial Economy of Emotions. Am. Sociol. Rev. 2019, 84, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zinn, M.B.; Hondagneu-Sotelo, P.; Messner, M.A. Gender through the prism of Difference; Oxford University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- McCall, L. The Complexity of Intersectionality. Signs 2005, 30, 1771–1800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreckel, R. Unequal opportunity structure, and labour market segmentation. Sociology 1980, 14, 525–550. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/42852233 (accessed on 13 August 2022). [CrossRef]

- Samantroy, E.; Nandi, S. Gender, Unpaid Work and Care in India; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Addati, L.; Cattaneo, U.; Esquivel, V.; Valarino, I. Care Work and Care Jobs for the Future of Decent Work. 2018. Available online: https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---dgreports/---dcomm/---publ/documents/publication/wcms_633166.pdf (accessed on 15 May 2022).

- Eichhorst, W.; Marx, P.; Wehner, C. Labor Market Reforms in Europe: Towards more flexicure labor markets? SSRN Electron. J. 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimshaw, D.; Rubery, J. The motherhood pay gap: A review of the issues, theory and international evidence. ILO. 6 March 2015. Available online: https://www.ilo.org/global/publications/working-papers/WCMS_348041/lang--en/index.htm (accessed on 15 November 2022).

- Solati, F. Women, Work, and Patriarchy in the Middle East and North Africa; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Jobs and Economy during the Coronavirus Pandemic. 2021. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/info/live-work-travel-eu/coronavirus-response/jobs-and-economy-during-coronavirus-pandemic_en (accessed on 6 August 2022).

- Catarino, C.; Kontos, M.; Shinozaki, K. Family Matters: Migrant Domestic and Care Work and the Issue of Recognition. In Paradoxes of Integration: Female Migrants in Europe. International Perspectives on Migration; Anthias, F., Kontos, M., Morokvasic-Müller, M., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2013; Volume 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).