1. Introduction

The Australian construction industry’s resilience throughout the 2020 global COVID-19 pandemic is shown by the industry’s current 7.4% contribution to the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) [

1]. The industry is projected to grow considerably in the next decade and remain one of the nation’s largest industries [

2]. The construction industry in Australia is male dominated despite the increase in women studying and working in the industry in the recent two decades [

3]. Women who obtain a career in the industry are also challenged by the commonly known “glass ceiling”, where opportunities and promotions are even harder to achieve. The issues that women encounter in the Australian construction industry are ongoing and well researched with documented unsuccessful formal and informal strategies [

4].

A more constitutionalised approach with stricter legislative requirements is necessary to see significant improvements for women in the industry. Changes to Australia’s government-based construction contracts are required so that the internal tender review procedures and employee specific percentages are better accommodated to allow more female employees [

5]. These changes would assimilate a prerequisite for the percentage of women in public projects before tendering can be completed. This principle would increase the opportunities for women to acquire jobs while also making the problems women face while working in the industry more common and thus more likely to improve.

To encourage women’s participation in the construction industry, multiple interventions are required from the government, accrediting bodies, and the industry. This paper is a small but significant effort in proposing one policy that can push the industry to employ more women. The concept of putting gender on the tender of public projects in Australia is discussed throughout this paper. This study presents the current literature-based evidence of the reasons for low female participation in the industry and previous ineffective schemes to increase the number. This paper also explains the methods of review and discusses current organisations that support the concept and its benefits while providing recommendations on initiating the change of legislation.

2. Literature Review

This literature review section is based on 30 articles relevant to the study of putting gender on the tender. These articles have been divided into four themes: underrepresentation, barriers to career, education pathways, and opportunities. The four themes have represented both negative and positive influences on women’s attempts to be a part of and remain in the Australian construction industry. All four themes discussed further the importance of putting gender on the tender in Australian public projects.

2.1. Underrepresentation

The opportunities for women in the Australian construction industry have slightly increased throughout the recent decade; however, the overall representation of women is still evidently limited [

6]. The labelled “male” occupation in Australia is still far from breaking down the macho stereotypes that both degrade and discourage women’s participation [

2]. The construction industry as a whole has not officially acknowledged a concern for equal representation, which has the potential to resolve labour shortages [

6].

Various studies have suggested the main reason for underrepresentation is due to the associated gender discrimination practices common in the construction industry, such as sexual harassment and recruiting policies [

7]. These concerns are well researched especially in Australia, and multilevel government initiatives and investments have been implemented [

5]. Legislation such as The Workplace Gender Equality Act 2012 describes the Australian Government’s procurement policies that came into effect from 1 August, 2013. This policy requires public companies and non-public sector employers with 100 or more employees to supply a letter of compliance to the Workplace Gender Equality Agency (WGEA) with any tender submissions prior to contracting in Australia [

8]. The report must contain information on gender equality indicators (GEIs) that include the gender composition of the workforce [

8].

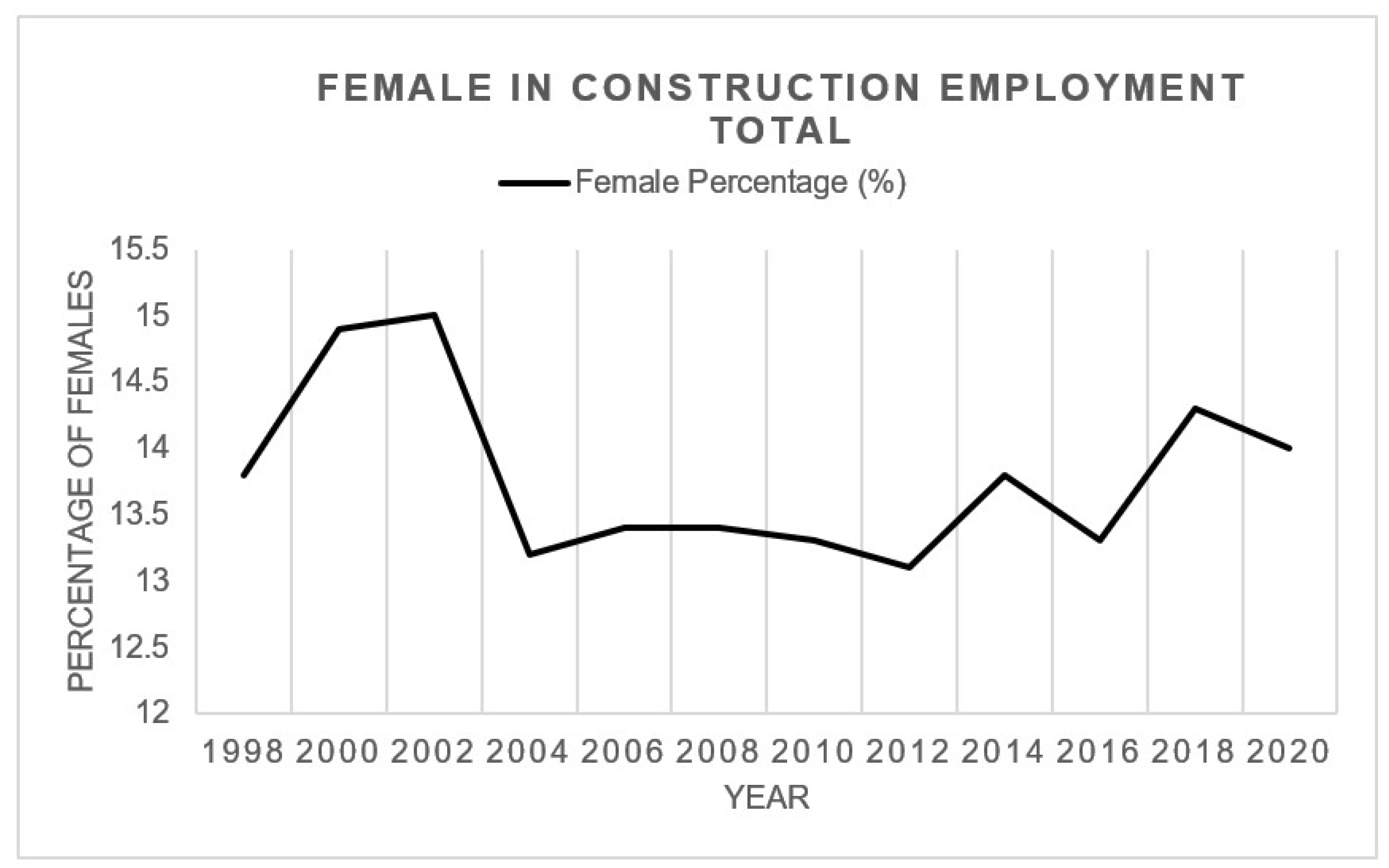

The GEIs shown in

Figure 1 reveal that women in Australia’s construction industry accounted for 13.8% of employees in 1998 and 14% in 2020 [

9]. This underrepresentation of women in the construction industry is reflected in other nations with 11.5% in Austria, 11.6% in the United Kingdom, 11.5% in Canada, 7.2% in Sweden, and 9% in the United States [

5]. Despite recent improvements for women in the Australian construction industry, they are still both numerically and hierarchically underrepresented, with the majority of the women in construction situated in lower-level jobs, such as secretarial and clerical work [

10]. Australia needs new legislative requirements that enforce new gender equity policies, such as setting a minimum gender percentage requirement on tendering documents for all public projects to change the female population’s representation [

3].

2.2. Barriers to Career

The Australian construction industry is known for its sexism in relation to limited female job opportunities [

11]. The non-traditional female career is dominated by networking influences when hiring for positions occurs [

4]. The industry’s lack of gender diversity has cyclic effects that further reduce opportunities for women to enter the profession [

12]. Common reoccurring barriers for women joining the industry as shown in studies are lack of training, disrespect to women, male-dominated networking, poor conditions of employment with undefined long hours, weekend work, and discouragement from taking time off [

13]. These barriers are combined with a culture of unencouraged flexible or part-time work arrangements, which are associated with women’s lifestyles [

2]. This un-friendly female environment pushes “male values” that encourage women in the industry to forgo potential children or family life to achieve a sustainable career [

6]. On the other hand, suitable work-oriented women in the Australian industry are ideal and yet are still susceptible to negative perceptions of their capability, lack of mentors, slow career progression with fewer developmental experiences, and a lack of recognition compared to their male counterparts [

14].

These barriers are still prevalent even after in 1990 Australia ratified ILO Convention 156, which obligates Australian employers to allow employees to engage in both work and family responsibilities without discrimination or conflict [

14]. New legislation in the form of gender percentage requirements on public tendering documents would eliminate a large portion of barriers for women. This legislation is supported by current Australian not-for-profit organisations, such as The National Association of Women in Construction (NAWIC), that are actively advocating for more women in construction to see change in the industry. The NSW Government in particular has recently implemented new strategies in 2021 to enhance training opportunities for women in NSW indicated in

Table 1.

2.3. Education Pathways

Despite initiatives to promote women in the Australian construction industry, a primary audience of young women are unaware of the opportunities in construction [

10]. All levels of education, especially schools and universities, impact the industry’s low female enrolments and discourage high female participation rates in the industry [

5]. The education system should be used to introduce women to the construction industry through pathways shown in

Table 2.

Universities in particular can play a vital role in increasing women in the industry as graduates are exposed to the culture of the industry and working in a male-dominated environment [

2]. This exposure and methods of having female role models and mentors in the construction industry can inspire and foster attributes for more women to want to work in the industry [

2]. Currently, the initiatives implemented in Australia to recruit and retain women in the construction industry and in courses such as construction management are not improving numbers [

16]. New legislation requirements for public projects in Australia, such as gender submission requirements, would see an increase in potential jobs and encourage more women to participate in construction-based education [

5].

Initiatives such as the Built for Women program currently run in NSW by the government also foster the idea of supporting more women in the industry through education. The strategy created 3000 fee-free job training placements for women in construction and other related fields [

17]. There are 154 full qualifications and 408 part qualifications available targeted to women ages 16 to 24 [

17]. This opportunity for women to have a construction career path promotes other gender equity provisions that encourage women to enrol.

2.4. Opportunities for Employment

The limited number of women in the Australian construction industry should promote better ideas on the methods of recruitment and retention that come from the industry itself [

18]. It has been shown that women are rarely presented with an opportunity to work in the industry, which reflects on the employers in the Australian construction industry [

2].

Table 3 describes how these opportunities could come from a national, organisational, and union level.

Opportunities within public companies in Australia would improve with action towards more women graduate recruitment and gender equality provisions in construction procurement processes [

3]. Organisations such as Women in Power based in QLD also support the idea of increasing women in the construction industry. They have spoken on the potential for the government to put gender on the tender for companies competing for government jobs [

19]. This idea would entail the government putting gender equality at the same level of importance as critical elements such as cost and design [

19]. Employers in the Australian construction industry should recognise the benefits of gender equality and better adhere to the implemented legalisation from state and federal sex and age discrimination laws [

5].

Legislation such as the Workplace Gender Equality Act 2012 that is administered by the Workplace Gender Equality Agency states that companies with 100 employees or more are required to report the nature and composition of gender in their workforce [

10]. This is supported by the Australian Securities Exchange through non-compulsory methods for Australian publicly listed companies to disclose equality policies and gender targets or otherwise be required to present a reason for non-disclosure [

5]. These opportunities encourage more women to participate in the construction industry and change employers’ cultures on women in their workforce [

3].

3. Methodology

A systematic literature review was conducted to identify the recurring themes in relation to women in the construction industry. A systematic review was initially completed to accumulate potential literature sources from the database Scopus. These potential scholarly sources were filtered through different phases of review. A total of 56 relevant sources were obtained, as shown in

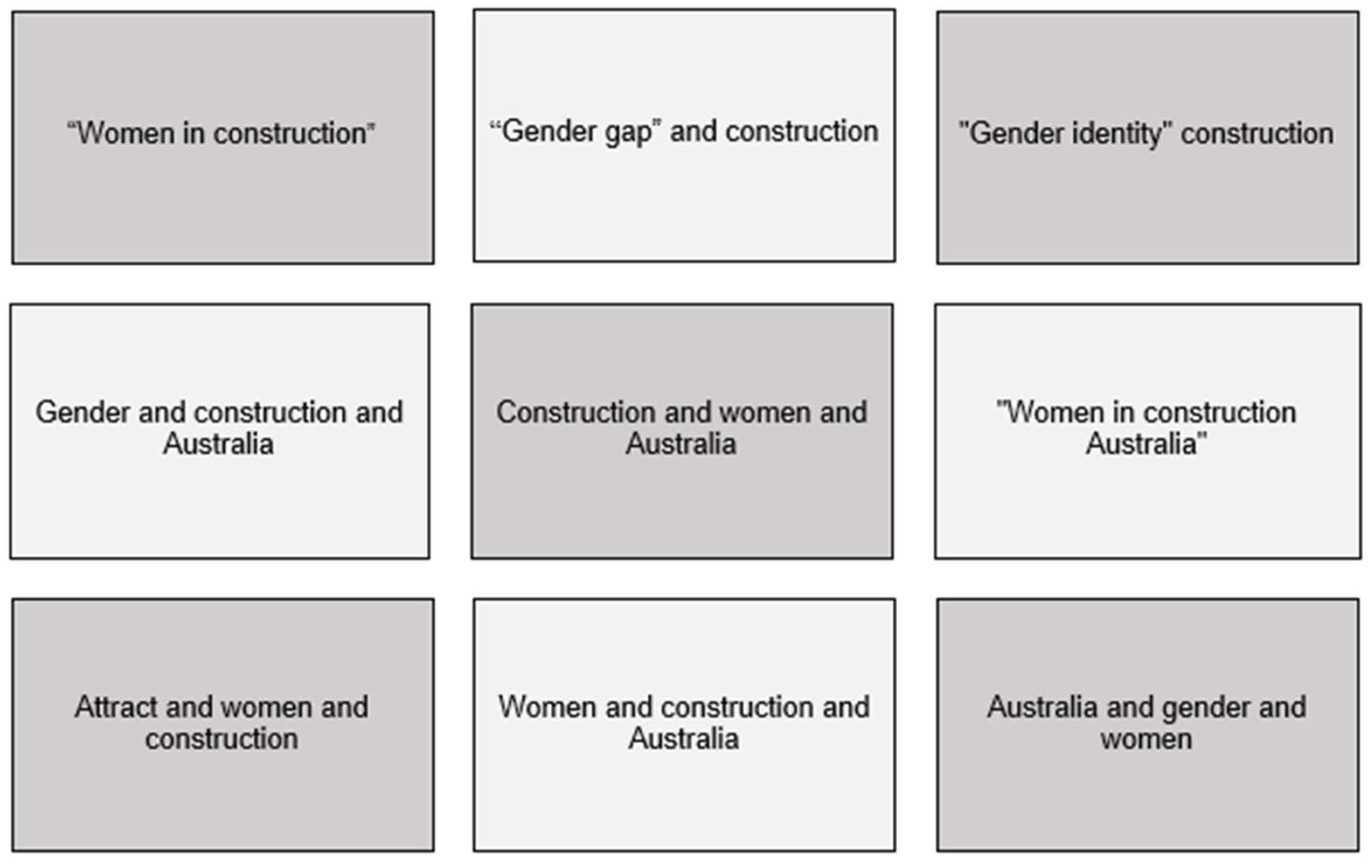

Figure 2, from the 9 keywords and phrases outlined in

Figure 3.

The limited number of sources (56) is likely due to the innovative nature of this study, as there is little documented information on effective change for women in Australia’s construction industry. The identified sources (56) were then screened for title and abstract. This meant that the research papers (56) had to be presented as an article with a structured summary synthesised to present an overview of the research and its relevance to women in Australia’s construction.

The screening eliminated 26 articles from the potential 56 for reasons such as no viable connection to women in Australia’s construction, no relevant characteristics, outdated sources of information, and assessments that have been surpassed. For the remaining 30 articles, eligibility criteria were assessed where the full text was assessed for relevance to both women in construction and building on the idea of putting gender on the tender. A further 5 articles were excluded from the 30 for having no potential links to the objective of this study.

A second screening was then conducted on the 25 remaining sources whereby the references of the sources were systematically reviewed for new potential articles. From the 25 articles an additional 7 likely sources were identified, screened, and assessed for eligibility where 2 of these new sources were excluded. The final sample size for the literature review was 30 articles as shown in

Figure 2.

Figure 3 shows the keywords and phrases used for the Scopus database were developed through trial and error whereby the 9 most successful and useful keywords and phrases were utilised.

The 30 scholarly sources were collated from the years 1999 to 2021 in a 22-year timeline that is shown in

Table 4, which revealed an obvious sequence of limited change for women in Australia’s construction industry.

The two decades worth of research was sourced from a variety of journals with differing methods of research. The 30 articles had similar points of origin with recurring journals represented in

Table 5; this showed there was repetition with the ongoing issues with women in construction or the lack thereof.

The volume of evidence was thoroughly analysed to establish four themes that reflected the impact the construction industry has had on women. These themes also provide the connection between what the Australian construction industry has been like for women and how change such as putting gender on tender legislation could improve the current environment (

Table 6).

4. Discussion

4.1. Evidence

There are no current legislative requirements for any of the sates in Australia to have gender considered when tendering. This means that a holistic approach must be taken to identify gender as a factor in any public project. Currently, there are the Workplace Gender Equality Procurement Principles introduced in 2013 by the Australian Government intended to amend legislation around gender equality.

However, the principles only encouraged organisations that were compliant to the Workplace Gender Equality Act 2012 to submit a letter of compliance with proposed tender submissions to work with the Australian Government. Potential public projects’ letters of compliance are required to include gender equality indicators, such as the composition of women on proposed works, but there are no requirements on the number of women or female representation [

34].

As there is no current prerequisite for tendering public projects anywhere in Australia that includes gender as a consideration before approval, there is a need for change. Changes to legislation, such as implementing gender minimum requirements on tender documents for public projects, would need the approval of the Office for Women. The Australian Government’s “Office for Women” provides policy advice and support to the minister for women and the prime minister. The OFW works on behalf of the government to deliver policies and programs that improve both gender equity and the lives of women in Australia [

35].

The Australian Government announced at the Women’s Budget Statement 2021–2022 that they were seeking feedback on the current Workplace Gender Equality Act 2012 to reconsider gender indicators, legislation, and employer reporting obligations [

36,

37].

The focus was on how the next ten years could achieve gender equality, and input was welcomed from a variety of sources:

Employers

Human rights institutions

Women’s sector

Non-government organisations

Academics

Government departments of all levels

A total of 155 submissions were received on the close of feedback on 24 November 2021 [

38,

39]. This recognition by the Australian Government proves that change is needed for gender equality and creates the potential for new legislative employer reporting obligations, such as introducing a minimum standard of women when a tender is proposed before it can be approved on any public works.

4.2. Benefits

Gender equality is represented as Goal 5 of the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals, where Target 5.C highlights the importance of enforceable legislation and the promotion of gender equality [

40]. The United Nation’s sustainable development Goal 5 should be better promoted by the Australian Commonwealth as the Australian Government’s procurement of public works is a large economic contributor to the GDP. Government tenders are a high value economic influence that have the potential to improve gender diversity in construction.

The Victorian Government has recognised the value government projects have by introducing the 2020 gender equality policy. The policy mandates at least 3% female representation for trade roles, 7% for non-trade positions, and 35% for management and supervisory positions [

41]. The policy represents action that must be taken by the government to mandate and enforce minimum female participation in public works. If the Australian Government took initiative from the Victorian Government by creating new legislative policies that put gender on the tender of public works, there would be several benefits [

41,

42]:

More women in construction to advocate for programs such as apprenticeships and scholarships;

More opportunities for women to obtain higher positions and be in a place to mentor;

Workplace gender inequity cultures of sexism and stereotyping more likely to be campaigned;

Would attract different levels of education to encourage young women to join construction with the promise of more female-specific jobs;

Traditional “pipelined” male networking for employment would no longer be sufficient for potential public works;

Discriminatory practices in the hiring process, such as deeming construction work too difficult for women, would be irrelevant;

Increasing the prominence and visibility of women in construction would make female work-related issues more of a concern for the majority;

Diversity in the workforce to bring different perspectives and methods on work;

Rigid workplace practices that do not value a family/work–life balance would gain more attention;

Current occupational health and safety hazards for women, such as inadequate bathroom facilities and inappropriate clothing, would become more likely to be addressed;

More women exposed to the construction industry would lead to better possibilities of retention.

The increase in potential jobs for women in the Australian construction industry would create overall leverage for change. Putting gender on the tender would start to introduce more women into the industry, thus also bringing to light the issues that have prevented women from obtaining a job in the industry.

5. Conclusions

There has been significant research conducted around the disadvantages and issues women in the Australian construction industry continue to face. Despite the reoccurring themes that affect these women, there is little research on strategies that would effectively improve the construction environment for them. The culture of the Australian construction industry that deters and prevents women from entering is unlikely to change within the next decade.

This study highlights the need for affirmative action to be taken by the Australian Government. To date, there are several bodies of research that suggest a combination of changing legislation and repercussions for non-compliance would be the most effective measure.

The results of this study suggest that including gender as a requirement on tenders, such as a minimum representation percentage of 2–5% before they can be approved by the government, would be the change the industry needs. This requirement would need both a change to the legislation and to be enforced to be effective. The trends of Australian construction shown in the literature review predict the industry will grow in both jobs and economic value. This means that changes to legislation must occur soon to benefit all the parties of interest.

The literature review methodology of this study did have some limitations, which included the present-day nature of the research meaning there was a shortage of relevant previous studies. The referenced sources were also influenced by their origin, as articles sourced from Australia were favoured. This also limited the outcomes of the study as the research is only relevant to women in Australia’s construction industry.

To overcome these limitations in future research, the scope of the study should be extended to other countries or nations. A larger scope would increase the potential sample size and create a better projection of the trends regarding women in the construction industry. It is recommended that future research be conducted on topics such as the Australian Government’s commitment to increasing women’s participation in construction, the impacts modern Australia’s construction industry could experience from an increase in women, and the required Australian state-specific legislation that promotes women in construction. The recent changes observed in parliament around the Workplace Gender Equality Act from late 2021 to early 2022 demonstrate the government’s ability to make legislative change and promote the need to see an increase in women in the Australian construction industry. Another direction could be researching how hegemonic masculinity affects professions in construction. Moreover, in comparison with the glass ceiling effect for women in construction, the glass wall effect, which may prevent women from entering and obtaining jobs in the construction industry, may also be worth exploring in further research.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, L.T., S.S. and L.S.; methodology, L.T. and E.S.; writing—original draft preparation, E.S. and L.T.; writing—review and editing, S.S., L.S. and M.W.; supervision, L.T.; funding acquisition, L.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Summer Research Internship Scheme of the College of Engineering, Science and Environment at the University of Newcastle.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the reviewers and editors for providing comments to improve the quality of the paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Reserve Bank of Australia. Composition of the Australian Economy. Snapshot Comparison. 2022. Available online: https://www.rba.gov.au/snapshots/economy-composition-snapshot/pdf/economy-composition-snapshot.pdf?v=2022-01-20-14-58-13 (accessed on 4 February 2022).

- Afolabi, A.; Oyeyipo, O.; Ojelabi, R.; Patience, T.-O. Balancing the Female Identity in the Construction Industry. J. Constr. Dev. Ctries. 2019, 24, 83–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, M.; French, E. Female underrepresentation in project-based organizations exposes organizational isomorphism. Equal. Divers. Incl. Int. J. 2018, 37, 799–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aboagye-Nimo, E.; Wood, H.; Collison, J. Complexity of women’s modern-day challenges in construction. Eng. Constr. Arch. Manag. 2019, 26, 2550–2565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carnemolla, P.; Galea, N. Why Australian female high school students do not choose construction as a career: A qualitative investigation into value beliefs about the construction industry. J. Eng. Educ. 2021, 110, 819–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fielden, S.L.; Davidson, M.J.; Gale, A.W.; Davey, C.L. Women in construction: The untapped resource. Constr. Manag. Econ. 2000, 18, 113–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro-Astor, E.; Román-Onsalo, M.; Infante-Perea, M. Women’s career development in the construction industry across 15 years: Main barriers. J. Eng. Des. Technol. 2017, 15, 199–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Workplace Gender Equality Agency. Workplace Gender Equality Procurement Principals; Australian Government. 2021. Available online: https://www.wgea.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/PMC-WGE-Procurement-Principles.pdf (accessed on 4 February 2022).

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. Labour Force, Australia, Detailed, Quarterly 2020. Available online: https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/labour/employment-and-unemployment/labour-force-australia-detailed-quarterly/latest-release (accessed on 4 February 2022).

- Zhang, R.P.; Holdsworth, S.; Turner, M.; Andamon, M.M. Does gender really matter? A closer look at early career women in construction. Constr. Manag. Econ. 2021, 39, 669–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, J.F.; Davidson, M.J.; Galeand, A.W. Women in construction: A comparative investigation into the expectations and experiences of female and male construction undergraduates and employees. Women Manag. Rev. 1999, 14, 273–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bridges, D.; Wulff, E.; Bamberry, L.; Krivokapic-Skoko, B.; Jenkins, S. Negotiating gender in the male-dominated skilled trades: A systematic literature review. Constr. Manag. Econ. 2020, 38, 894–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fielden, S.L.; Davidson, M.J.; Gale, A.; Davey, C.L. Women, equality and construction. J. Manag. Dev. 2001, 20, 293–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lingard, H.; Lin, J. Career, family and work environment determinants of organizational commitment among women in the Australian construction industry. Constr. Manag. Econ. 2004, 22, 409–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Training Services NSW. Trade Pathways Women’s Strategy: NSW Government. 2021. Available online: https://www.training.nsw.gov.au/programs_services/tpws/grants/index.html (accessed on 4 February 2022).

- Bigelow, B.F.; Bilbo, D.; Mathew, M.; Ritter, L.; Elliott, J.W. Identifying the Most Effective Factors in Attracting Female Undergraduate Students to Construction Management. Int. J. Constr. Educ. Res. 2014, 11, 179–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bigelow, B.F.; Bilbo, D.; Mathew, M.; Ritter, L.; Elliott, J.W. An Evaluation of Factors for Retaining Female Students in Construction Management Programs. Int. J. Constr. Educ. Res. 2016, 12, 18–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NSW Department of Education. NSW Job Trainer: Built for Women. 2021. Available online: https://www.training.nsw.gov.au/forms_documents/programs_services/sfr/built_for_women_flyer.pdf (accessed on 4 February 2022).

- Galea, N.; Powell, A.; Loosemore, M.; Chappell, L. Designing robust and revisable policies for gender equality: Lessons from the Australian construction industry. Constr. Manag. Econ. 2015, 33, 375–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whittock, M. Women’s experiences of non-traditional employment: Is gender equality in this area a possibility? Constr. Manag. Econ. 2002, 20, 449–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Worrall, L.; Harris, K.; Stewart, R.; Thomas, A.; McDermott, P. Barriers to women in the UK construction industry. Eng. Constr. Arch. Manag. 2010, 17, 268–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King-Lewis, A.; Shan, Y.; Ivey, M. Gender Bias and Its Impact on Self-Concept in Undergraduate and Graduate Construction Education Programs in the United States. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2021, 147, 04021155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menches, C.L.; Abraham, D.M. Women in Construction—Tapping the Untapped Resource to Meet Future Demands. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2007, 133, 701–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maurer, J.A.; Choi, D.; Hur, H. Building a diverse engineering and construction industry: Public and private sector retention of women in the civil engineering workforce. J. Manag. Eng. 2021, 37, 04021028-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afolabi, A.O.; Tunji-Olayeni, P.F.; Oyeyipo, O.O.; Ojelabi, R.A. The Socio-Economics of Women Inclusion in Green Construction. Constr. Econ. Build. 2017, 17, 70–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rosa, J.E.; Hon, C.K.; Xia, B.; Lamari, F. Challenges, success factors and strategies for women’s career development in the Australian construction industry. Constr. Econ. Build. 2017, 17, 27–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryce, T.; Far, H.; Gardner, A. Barriers to career advancement for female engineers in Australia’s civil construction industry and recommended solutions. Aust. J. Civil Eng. 2019, 17, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, R. Quotas for Men: Reframing Gender Quotas as a Means of Improving Representation for All. Am. Politi-Sci. Rev. 2014, 108, 520–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dainty, A.R.J.; Bagilhole, B.M.; Ansari, K.H.; Jackson, J. Creating equality in the construction industry: An agenda for change for women and ethnic minorities. J. Constr. Res. 2004, 05, 75–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adeyemi, A.Y.; Ojo, S.O.; Aina, O.O.; Olanipekun, E.A. Empirical evidence of women under-representation in the construction industry in Nigeria. Women Manag. Rev. 2006, 21, 567–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, H.K.; Lindsey, A.; King, E.; Hebl, M.R. Beyond sex: Exploring the effects of femininity and masculinity on women’s use of influence tactics. Gender Manag. 2016, 31, 43–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olofsdotter, G.; Randevåg, L. Doing masculinities in construction project management: “We understand each other, but she…”. Gender Manag. 2016, 31, 134–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dainty, A.R.J.; Neale, R.H.; Bagilhole, B.M. Women’s careers in large construction companies: Expectations unfulfilled? Career Dev. Int. 1999, 4, 353–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galea, N.; Chappell, L. Male-dominated workplaces and the power of masculine privilege: A comparison of the Australian political and construction sectors. Gender Work Organ. 2021, 29, 1692–1711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oo, B.L.; Liu, X.; Lim, B.T.H. The experiences of tradeswomen in the Australian construction industry. Int. J. Constr. Manag. 2020, 22, 1408–1419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Australian Government. Workplace Gender Equality Procurement Principles and User Guide: Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet. 2013. Available online: https://www.finance.gov.au/sites/default/files/2021-12/PMC-WGE-Procurement-Principles.pdf (accessed on 4 February 2022).

- Women in Power. Can the Government Do More? Gender on the Tender. 2021. Available online: http://womeninpower.org.au/can-government-gender-tender/ (accessed on 4 February 2022).

- Australian Government. Office for Women: Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet. 2021. Available online: https://www.pmc.gov.au/office-women (accessed on 4 February 2022).

- Australian Government. Workplace Gender Equality: Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet. 2021. Available online: https://www.pmc.gov.au/office-women/workplace-gender-equality (accessed on 4 February 2022).

- Australian Government. Review of the Workplace Gender Equality Act 2012 Submissions. 2021. Available online: https://www.pmc.gov.au/office-women/workplace-gender-equality/review-workplace-gender-equality-act-2012-submissions (accessed on 4 February 2022).

- United Nations. Goal 5: Achieve Gender Equality and Empower All Women and Girls: Sustainable Development Goals. 2022. Available online: https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/gender-equality/ (accessed on 4 February 2022).

- Victorian Government. Victoria’s Women in Construction Strategy. Building Gender Equality: How the Victorian Government Plans to Achieve Greater Representation of Women in Construction. 2021. Available online: https://www.vic.gov.au/victorias-women-construction-strategy (accessed on 4 February 2022).

| Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).