1. Introduction

More than half of the world’s population currently lives in urban areas [

1]. As projected by the United Nations, 68 percent of the world’s population is expected to live in urban areas by the year 2050 [

2]. In this rapidly urbanizing trend, 60 percent of the world’s child population is also expected to live in cities by the year 2025 [

3]. Therefore, promoting child-friendly urban development is significant in order to offer a good quality of living and accessibility to all children in cities. This particularly includes urban spaces with facilities for play, such as urban parks with playgrounds, which are among sustainable city indicators [

4,

5]. Peñalosa stated that, “children are a kind of indicator species. If we can build a successful city for children, we will have a successful city for all people.” [

6] (p. 243).

Likewise, the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC) aims to provide a basis for the focus on children. This convention identified many rights of children, including making their voices heard in all matters affecting them [

7,

8,

9]. As many countries are rapidly urbanizing and the urban children population is increasing, promoting child-friendly cities and communities is getting more attention [

10]. This agenda significantly aims to ensure that city governments pay greater attention to children and their rights while ensuring a healthy environment for children, particularly protection, education, and participation, is addressed by the policymakers [

11].

In order to provide a framework for developing child-friendly cities and communities, the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) produced a framework for action named “Building child-friendly cities”. This framework outlines the steps to build a governance system that is committed to achieving all rights of children and translates the implementation process from UNCRC to national and local governments [

12]. Furthermore, since the child-friendly cities initiative was launched to promote the rights of children in urbanized communities and cities, it has been bringing local stakeholders together with UNICEF to create cities and communities to offer safe, inclusive, and responsive conditions for children [

13,

14,

15,

16]. UNICEF also developed a child-friendly cities and communities guidebook showing good practices and addressing common challenges and lessons learned to assist city governments and relevant stakeholders in the development and implementation of the child-friendly cities and communities initiative [

17].

Accordingly, the Cambodia National Council for Children was established to coordinate and provide comments to the national government on works related to the survival, development, protection, and welfare of children. The composition and structures of this council were also reformed to establish its offices at the sub-national levels, especially to set up working groups to focus on the rights of children at relevant governmental institutions. These reforms significantly aim to further facilitate progression towards implementing the rights of children in Cambodia [

18]. Interestingly, through a collaboration between the Cambodia National Council for Children and Plan International Organization in Cambodia, a framework named “Child-friendly community initiative” was developed in 2012. This jointly developed framework aims to further improve conducive environments for children where their rights are recognized, realized, and supported [

19].

Following national and international trends on child-friendly urban development, many non-governmental organizations and relevant stakeholders have come together to build urban child-friendly communities. Likewise, the PSE (Pour un Sourire d’Enfant “smile of a child”) and STEP (Solutions To End Poverty) organizations have collaborated with relevant key partners to build a Smile Village community in Phnom Penh city [

20]. This community is firstly known as an initiative to provide “smiles” and hope to underprivileged families. Although its main vision is to build a residential community for poor urban families to achieve social and financial mobility [

21], it has facilities and programs developed for children. Jointly, the STEP organization is committed to improving the household quality and income while the PSE organization provides supports to improve child education in the community, including childcare services. It seems that the Smile Village community is a child-friendly community. Hence, this study aims to explore the Smile Village community on child-friendly dimensions and to examine whether this urban community is a child-friendly community. This study uses the international child-friendly framework and initiatives to reflect on the national child-friendly community framework through Smile Village development initiative analysis. “Has this initiative fulfilled the national child-friendly community development’s core dimensions: children’s health, protection, education, and participation?” is therefore the research question of this study.

2. Literature Review

2.1. International Child-Friendly Framework

In 2004, UNICEF developed a framework for action to build child-friendly cities and communities. This framework aims to build a governance system committed to fulfilling the rights of children and interpreted the implementation process on UNCRC to both national and local government levels [

12]. In 2018, UNICEF developed a child-friendly city and community guidebook by consolidating good practices together with a set of common challenges and lessons learned in order to assist the city governments and relevant stakeholders in implementing the child-friendly cities and communities initiative [

17]. This guidebook outlines nine building blocks as follows: children’s participation, a child-friendly legal framework, a city-wide children’s rights strategy, a children’s rights unit or coordinating mechanism, child impact assessment and evaluation, a children’s budget, a regular report on the state of the city’s children, making children’s rights known, and independent advocacy for children. These building blocks and their descriptions are shown in

Table 1.

The child-friendly cities and communities initiatives around the world, as presented by Chan et al. [

22], have been following these building blocks. They addressed these building blocks accordingly within their city and community contexts and structures. Among the nine good practices of the initiatives explored by the research, there are two from industrialized regions (Italy and Japan) and one from each of the following countries: Vietnam, Bangladesh, Ukraine, Brazil, Jordan, Nigeria, and South Africa.

The Italian initiative named “Sustainable Cities for Girls and Boys” was implemented by the Ministry of Environment. This initiative brings children to work together with professionals through a legally embedded action plan. This initiative aims to make cities more friendly for children by consulting with the children’s councils. This initiative encouraged local authorities to develop relevant policies and programs through defining their child-friendly cities framework and cultural and legislative boundaries [

23,

24].

The Japanese initiative named “Kawasaki City Ordinance on the Rights of the Child” was implemented by the Ombudsperson System for Human Eights of the Kawasaki City Council. This initiative was established by taking into account many views and opinions of the city’s citizens and children. This initiative set up a city ordinance to secure the rights of children in Kawasaki city, particularly to improve their living conditions. The initiative incorporated key provisions of the UNCRC by committing to realize the right for a meaningful participation and safe environment in various contexts [

25,

26].

The Vietnamese initiative under the Dien Bien Socio-Economic Development Plan was jointly implemented by UNICEF Vietnam, national and provincial governments, UNDP, and UNFPA. This initiative known as the provincial child-friendly programs aimed to mainstream the rights of children as well as women in provincial policies and activities. This initiative sought to mainstream the rights of children throughout all relevant departments at the national level, which includes both government official capacity building and child-friendly project implementation by local committees [

27,

28].

The Bangladeshi initiative named “Basic Education for the Hard-to-Reach Urban Children” was implemented by the Bureau of Non-Formal Education. Several non-governmental organizations (NGOs) were involved and selected to run the learning centers for children. This initiative was a collaborative project between the government and NGOs and aimed to provide urban children with a two-year informal education. This initiative was widely recognized for its independent advocacy for children [

29,

30,

31].

The Ukrainian initiative under the advocacy, information, and social policy program was implemented by UNICEF Ukraine. This initiative realized the monitoring system for children’s rights and the awareness promotion of rights among youth. This initiative incorporated the governance of the child-friendly city model. This model consists of indicators to achieve the child-friendly status that must be fulfilled by the city. This initiative also correspondingly contains a database to manage documentation [

22,

32].

The Brazilian initiative under the Children’s Participatory Budget Council in Barra Mansa was implemented by the UN Urban Management Program for Latin America. The initiative aims to provide the locally elected children aged from 9 to 15 years old with a budget to finance projects that help improve the city from the children’s viewpoints. This initiative was widely recognized for its children’s participation [

33,

34].

The Jordanian initiative under the Greater Amman Municipality was implemented by the Greater Amman Municipality and UNICEF Jordan. This initiative was first developed by an executive child-friendly agency and municipal councils for children. This initiative also produced a holistic strategic document to improve the lives of urban children and was widely recognized for its city-wide children’s rights strategy [

22,

35].

The Nigerian child-friendly city initiative was implemented by UNICEF and the Local Government Authority of Port Harcourt. This initiative built the government official capacity on the child-friendly city concept. A number of workshops were organized based on various issues to develop child-friendly projects. The initiative sought to improve the living quality of poor urban children by advancing institutional capacity, especially the connections between urban communities for raising UNCRC awareness [

22,

36].

The South African initiative named “Metropolitan Action Program for Children” was implemented by the Johannesburg city council, mayor’s office, and child-friendly cities manager. At the beginning, this initiative established an actual office for child-friendly cities to take responsibility for providing basic needs and information to children and to ask their opinions on how to make the city more friendly for them. Thus, this initiative collected the opinions from the children regarding their living conditions [

22,

37].

2.2. Cambodian Child-Friendly Framework

The above theoretical review reflects the international child-friendly cities and communities’ framework with child-friendly cities and communities initiatives from nine countries. This review shows that the internationally proposed building blocks are working well with developed or high human-development countries. For example, these building blocks have been well adopted by the Japanese Kawasaki city initiative [

25,

26]. In particular, “child-friendly legal framework” and “independent advocacy for children” are significant building blocks to realize the rights of children and child-friendly development in cities and communities, and the Japanese initiative has adapted these building blocks well. In contrast, these building blocks have not worked well with developing or low human-development countries due to the contexts and structures of those cities and communities not being ready to adapt. For example, Bangladeshi and Nigerian child-friendly initiatives have adapted only one building block for each [

22]. The Bangladeshi child-friendly initiative accordingly involved and selected several non-governmental organizations to run the learning centers for children to provide urban children with informal education, and this was recognized as independent advocacy for children [

30,

31]. The Nigerian child-friendly initiative is firstly committed to building the government official capacity on the child-friendly cities and communities’ concept by organizing a number of workshops seeking to improve living quality of poor urban children and advancing institutional capacity and connections between urban communities for raising awareness [

22,

36]. Hence, developing countries need a national child-friendly urban development framework to adapt with their city and community contexts and structures.

Consequently, Cambodia developed a national child-friendly community development framework. This framework aims to provide a conducive environment for children where their rights are recognized, realized, and supported. It highlights that all communities must be encouraged to promote child-friendliness, as most of the population in communities are children [

19]. Particularly, children pass through various developmental stages before reaching adulthood, and in every stage, children have their own characteristics, issues, and rights. Therefore, fulfilling the rights at all stages of child development will help children to realize their full potential. This is what Cambodia’s child-friendly community development framework is all about. The national child-friendly community development framework’s core dimensions are shown in

Table 2. Hence, this study will use this national framework to explore the Smile Village community on child-friendly dimensions and to confirm whether this urban community is a child-friendly community development initiative or not.

3. Study Methods

This study explored the community development initiative on child-friendly dimensions and examined whether an urban initiative is a child-friendly community or not by document review, interviews, and facility visits.

The document review is about reviewing existing reports and documents related to the Smile Village community that are available online. A reviewing method was found to be helpful in summarizing existing reports and documents [

38,

39] and an accompanying study based on existing knowledge and information was also addressed as the building block of all academic study and research activities, sometimes by validating with a consensus method, regardless of disciplines [

40,

41]. Therefore, this study reviewed existing reports and documents to preliminarily understand the Smile Village community development initiative, including its developed programs and facilities. This review was important to summarize the existing information on child-friendly dimensions of the Smile Village community, and all information was then validated during the interview.

The interview was about interviewing with the Smile Village community committee, which included the community management, children’s parents, and NGO staff. As mentioned earlier, the interview was also to validate the information gathered about the Smile Village community development focused on child-friendly dimensions. The interview focused on the community development background and was guided by a research question related to the national child-friendly community development’s core dimensions: children’s health, protection, education, and participation. The administrative procedure for having this interview was as follows. Firstly, the author requested permission to meet and interview with the community committee at the Smile Village community. After getting permission, the author went to the Smile Village community for the interview, as well as facility visits after the interview. This interview did not take much time as it mostly validated the gathered information. This interview proceeded as a focus group interview (FGI). The background of the community building project was explained again by the community committee and clarified by the NGO staff before moving to the research question related to core dimensions of the national child-friendly community development. All the community committee, including community management, children’s parents, and NGO staff, answered the questions as a group to observe that their answers were consistent and to generate a consensus. After the interview was done, facility visits proceeded.

The facility visits were important to understand the actual Smile Village community development initiative, including its developed programs and facilities, by focusing on child-friendly dimensions. Essentially, it was to verify that the child-friendly development facilities and programs found during the document review and discussed during the interview existed and were still working. This included the existing facilities; community center; playground; childcare center; and community infrastructures to education programs, kindergarten (pre-school), and primary school programs. The pre-school program caters to children from two to six years old, whereas the primary school program caters to the children from seven to twelve years old. On that day, there was a students’ campaign as well which allowed the researchers to see all students being guided by their teachers into the community center and happily gathering to play together after the school program.

Finally, this study used Cambodia’s child-friendly community framework and development’s core dimensions to examine and discuss the results. This study presents the gathered information and validated results in six sections classified based on their characterized and ordered information from

Section 4.1 to

Section 4.6 and examines the gathered information and discusses the results in

Section 4.7.

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Location and Direction

Smile Village is a community village widely known as Smile Village community, located in Phum Kom Reang, Prey Veng commune, Donkor district, Phnom Penh city, the capital of Cambodia. When seeing the word “Smile”, we feel the friendliness of this community. The Smile Village community is about 12 km from the city center and 900 m from the main street, Prey Sar (St. 2016). On this main street at the point next to Ang Metrey pagoda, there is a label showing a direction to this community (

Figure 1). The street direction label uses both Cambodian and English languages.

4.2. Development Background

Smile Village community is a community development initiative started by the three-way partnership of STEP (Solutions To End Poverty), PSE (Pour un Sourire d’Enfant), and HfH (Habitat For Humanity-Cambodia) in 2012 and later included other relevant key partners. The STEP and PSE organizations were known as the key organizations. The STEP organization is committed to improving household quality and income, while the PSE organization provides supports to improve child education in the community, such as childcare services and children’s education. As identified through the review and interview, these two organizations collaborated with many key partners, such as HfH-Cambodia, Grenzone, URBNARC, Billion Bricks, Garden and Landscape Center, and Creative O Preschoolers Bay, as well as volunteers from Singapore (Ngee Ann Polytechnic and National University of Singapore) and Malaysia (MyCorp).

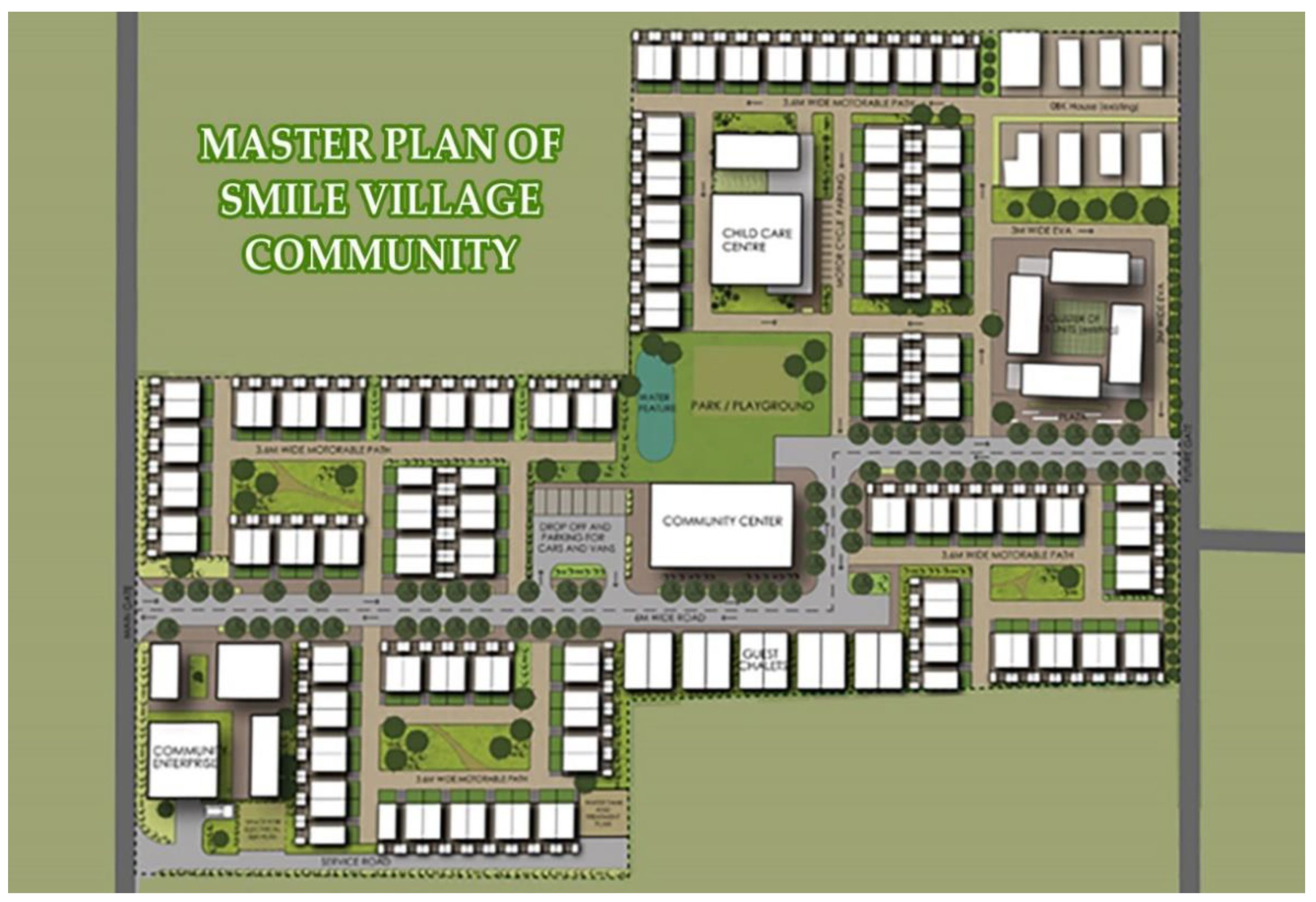

The Smile Village community development initiative planned to house 170 families relocated from various slums. This community has its own masterplan as shown in

Figure 2. With its mission to improve the livelihood of the underprivileged families, this community development initiative created three sectoral programs: (1) environment and shelter (houses and communal facilities), (2) livelihood and enterprise (income and sustainability, including enterprises within Smile Village, facilitating employment, and micro-businesses), and (3) community and education (community living and training, including children enrolled in PSE school, childcare, community health, and youth programs) [

21].

4.3. Accessibility and Communal Spaces

The Smile Village community is accessible by a local (village) road. Within a three-kilometer radius, there are markets, factories, and temples. In the middle of Smile Village community, there is a community center (hall), childcare center, and playground. As shown in its masterplan, the parks and playground are located in the middle and in between the community hall and childcare center. As observed, the Smile Village community is very accessible as well. All residential buildings are connected to each other without walls. Therefore, residents can easily access each other. Furthermore, there is no high-speed road across or next to the community; therefore, the children are safe and free to play in the community without much supervision from adults or their parents. Moreover, parents and children are also joyful because of many events and programs. For example, during a volunteer time of international students and teams, residents and volunteers joined together and shared their happiness, celebrated their new relationships, and cried together [

21]. In particular, the volunteer teams and home partners shared their talents in singing and dancing during the community event, while the children had educational campaigns with other children from PSE schools.

The Smile Village community has such a beautiful landscape with wide-open spaces, as shown in

Figure 3. There are a lot of flowers in front of the houses and greenery surrounding the houses. As mentioned earlier, the houses are connected to each other without a wall. This condition makes the interaction among the residents stronger and particularly allows children to interact easily with each other and gather to play in the community. Furthermore, they enjoy and experience an international community. For example, during summer break, a group of the National University of Singapore Department of Architecture’s students and staff came to volunteer in the Smile Village community. Moreover, the children also experience community gardening and vegetation. For example, through a collaboration with a landscape and garden center, they planned the tree nursery and prepared the ground for the nursery in the community. This program made the residents learn how to build and prepare bioswales. These activities made the children learn how to help each other, with support from the volunteers. Furthermore, volunteering activities can also make children understand how to help the community, which is a critical skill for building their sense of empathy [

42].

4.4. Playground Construction

The current playground in Smile Village was built by the architecture students from the National University of Singapore (NUS). Previously, the PSE organization installed playground equipment in their existing childcare facilities, which was made of metal, bought off the shelf, and only had one way to be used. They did not encourage creative play or challenge the children physically. Therefore, the PSE organization requested the NUS volunteer team to build new equipment for the children attending the childcare.

In 2014, a small team of NUS architecture students had a first mission to Cambodia to design and build a playground constructed from local materials at one of the PSE’s childcare centers. The design was presented to childcare teachers, children, and PSE management in the form of a physical model. Changes were made immediately after receiving feedback. Materials were then purchased, and recycled tires were also used. A year later, a larger team of the NUS architecture students came to design and build a playground at the site of the Smile Village community. A few villagers were hired to construct the playground. Art on the columns of the playground was made with thumbprints by the children. A step-by-step construction manual produced by NUS architecture students was left with Smile Village community’s workers and residents. This allows them to carry out their own maintenance and construct their own playground in other existing PSE childcare centers. The children were engaged to participate in the development of the playground from the beginning (concept planning and design), during the construction stage, and until the construction was completed (

Figure 4).

As a result, the playground is significantly fit for the children. It is quite popular, especially during holidays and weekends. An estimated 300 children from the Smile Village community and the surrounding areas play there. The playground also serves as a social gathering space as it located in the heart of the village. The parents who accompany their children to play at the playground also gather there. They are not only coming to watch and take care of their children playing but also to enjoy chit-chat with each other. This is the first time the children in this community have a local, safe playground to play in. The founder of the STEP organization, Ong Ailin, said “Never before have PSE children enjoyed such wonderful evening playtime safely in the lovely cool breeze! Thank you, NUS Architecture & the great efforts of the Smile Village Team! It’s truly a piece of heaven on earth” [

21] (p. 644).

4.5. Childcare and Education

As mentioned in previous sections, childcare services and child education in the Smile Village community are supported by the PSE organization. The PSE provides childcare services and general education, including vocational training to underprivileged children in the community. By collaborating with the STEP organization and other key partners, these childcare services and child education programs were designed with an open plan and open education concept. The childcare center was also designed with a green concept, which is being promoted by the government and green growth organizations [

43]. As shown in

Figure 5, it has wide spaces and big widows and does not need electric lamps in the daytime. Children in the community generally come to the childcare center by themselves because of closeness, accessibility, and a safe environment.

The PSE educational program is divided into pre-school (kindergarten) and primary school. The pre-school program caters to children from two to six years old. The primary school program caters to children from seven to twelve years old. As mentioned in the background information, this educational program is provided for free to the underprivileged children in the Smile Village community. With this program, every school-aged child living in Smile Village community goes to school. All families realize the importance of educational programs for their children [

44]. “Without education, they are destined to continue living in poverty” stated community committee members. The STEP organization also stated that “The proper early education for children is proven to be one of the most transformational investments one can make in their life. Besides of additionally direct benefits to children, this frees up parents to work and earn income for the family as well” [

45].

4.6. Children’s Champaign

Smile Village community is a very good place for the children’s campaign. It has a lot of green spaces and safe environments for children to learn, play, and relax. Its childcare center, playground, and community center are close and connected to each other without walls, which is a good condition for the campaign. Particularly, the community center is very useful for the children’s campaign in the rainy season. It has a wide space, so even when it is raining outside children still continue to play by moving into the hall.

The campaigns in the Smile Village community are usually held for children studying in both the community and other PSE schools. Coordinating teachers for the campaign are both Cambodians and foreigners. The foreign teachers volunteering at the PSE organization are mostly from France. Among the foreign teachers, some can speak the Cambodian language, but some cannot. However, there are still Cambodian teachers helping to translate during the campaign and to explain the activities of campaign in the community to all children, as shown in

Figure 6.

As mentioned earlier, during the rainy season children from the Smile Village community, surrounding areas, and/or campaigns are usually gathering and playing inside the community center. As shown in

Figure 7, they were likely to play inside the community center and run to or come back to play at the nearby playground if there was no rain outside. Sometimes the children living in the community played at the playground even when it was raining, but sometimes their parents did not allow them to play there because most people believe that playing in the rain is an easy, quick way to catch a cold [

46].

4.7. Discussion

The results of document review, interview, and facility visits on the Smile Village community development initiative by focusing on child-friendly dimensions showed that the community has developed a number of facilities and programs for its children. Firstly, childcare services and child education programs are very important for the children in the community. The programs cater to children from two to six years old and they have an afterschool care service from seven to twelve years old. The results also showed that the STEP organization has been playing an important role in developing facilities and improving the quality of living and household income, and the PSE organization has been playing an important role in supporting childcare services and educational programs. Therefore, the children in this community are well cared for and educated through the PSE programs. The children are also well protected by these two organizations, the community management, and the childcare teachers, as well as by their parents. Furthermore, greeneries, vegetable gardening, widely open and communal spaces, and accessibilities in the community provide very good conditions for the children’s health, play/happiness, and development. Good interaction between parents and relevant stakeholders in the community protect the children from all forms of violence. Particularly, childcare teachers have a close relationship with the children’s parents; consequently, it would be easy for teachers to investigate when the children are absent or not seen in classes during the school hours. It is also good for parents to check on the learning progress of their children. Interestingly, the community has a playground for its children located in the center of the community. The children were involved in the development of the playground during all stages, including the planning, design, and construction processes. As a result, the developed playground is significantly fit for children. It was found to be quite popular, especially during holidays and weekends. Importantly, the playground is not only the place where children come to play but is also where parents come to chit-chat with each other.

The above examination confirmed that the Smile Village community has fulfilled all the core dimensions of national child-friendly community development: children’s health, protection, education, and participation. This proved that the Smile Village community is an urban child-friendly community. However, how this community has fulfilled each dimension was found to be weak in children’s health, protection, and participation. Even though child protection conditions in the community are good because of the responsibility of the joint organizations and community management, childcare teachers, and their parents, protection procedures and systems are still needed to make sure everything is under control and to maintain the sustainability of the child protection in the community. Likewise, the community currently has its own childcare program, but it mainly focuses on the early child development stage. Therefore, the child health center and system for all children in the community are also needed to ensure children’s health is checked on time and to make sure their growth is healthy. Furthermore, the participation of children was found to be fully taken into account during the playground planning, design, and construction, but it is still needed for improving existing or future development facilities and programs. Thus, clear procedures and/or mechanism for promoting the participation of children are still necessary in the community development plan. As shown by UNICEF, children’s views are rarely considered and not really seen in the political process because the children are not among the groups to vote and take part in political activities [

47]. Therefore, “listening to children” is a simple and easy way for the government committee to develop an urban child-friendly community [

48].

Moreover, this study found that the collaborative development by joint roles and responsibilities of two or more NGOs in reducing the slums in the city can provide extensive significant results. As shown in the case of the Smile Village community development, it has provided appropriate resettlement conditions for the slum families that have helped to reduce urban slums and illegal/unplanned settlements, which is the first target of the United Nations Sustainable Development Goal 11 (UN SDG 11): Sustainable Cities and Communities [

49,

50]. Currently, there are more than 3000 NGOs in Cambodia [

51,

52]. If many more of the NGOs could jointly prioritize improving or promoting living conditions of urban slum families like this, it would greatly help to reducing slums and illegal/unplanned settlements in the cities and work towards achieving the first target of UN SDG 11. The government should also encourage this kind of collaboration in the development and improvement of urban slum areas or communities.

5. Conclusions

Many relevant stakeholders and organizations in Cambodia have come together to develop an urban community in Phnom Penh capital, called Smile Village community. Although its main vision is to build a residential community for underprivileged families to achieve social and financial mobility, various facilities and programs have been developed for children. This study objectively explored this community on child-friendly dimensions and examined whether this urban community is truly a child-friendly community or not. The results showed that Smile Village community has fulfilled all the core dimensions of the national child-friendly community development: children’s health, protection, education, and participation. Therefore, this study confirms that this urban community is a child-friendly community based on the national child-friendly community framework. However, this community was found to be weak in children’s health, protection, and participation. Therefore, this study recommends establishing a clear procedure and/or system for children’s health, protection, and participation in order to check children’s health on time, to make sure their growth is healthy, to maintain the full protection of children, and to promote the participation of children in the community. This study is limited to the child-friendly development of this community. Thus, this study did not explore in detail the income development and improvement program of this community, which is an important program to improve livelihoods by providing vocational training, setting up microbusiness, and finding markets to sell their products. Hence, future studies exploring this matter would significantly contribute to the whole development improvement and sustainability of the Smile Village community.