Abstract

The state is facing turbulent times. Financial and economic turmoil, growing inequalities, disinvestment in public and social services, and political disenchantment are but a few problems that contemporary society is facing, while traditional policies are failing to deliver the desired results. Social innovation is a possible approach to deal with emergent social needs. Research and policy experimentation on social innovation increased in the last decade, but many questions remain open. One key interrogation regards the relation of social innovation with the state. How can the state, considering the multi-level interactions that necessarily exist between different stakeholders, promote these practices? Using the case of Portugal, and the recent implementation of a pioneer public programmed dedicated to social innovation—Portugal Social Innovation—, this article contributes to the understanding of the role the state in the promotion of social innovation and the challenges, tensions, and difficulties experienced by those involved in the sector, whether as practitioners of social innovation or as heads of public institutions responsible for assisting in the development and implementation of social innovations. The article presents data gathered from a focus group involving the representatives from key third sector associations and officials responsible for public institutions that support the implementation of social innovation at the relevant levels of government (national, regional, local). Results show opportunities and tensions between the third sector and the different levels of the state, and a difficulty to adapt the processes and practices of public administration to the dynamic and creative nature of social innovation.

1. Introduction

Social innovation is a fashionable term these days. Permeating public policies, transnational institutions and governance designs, this notion quickly outgrew scientific fora, becoming a phenomenon in itself [1]. Yet, for all the buzz around the term, it still has several weaknesses and known limitations, being quite far from maturity as a scientific concept [2].

Different definitions, descriptions and interpretations of social innovation have been presented over the last two decades or so, with few often agreeing on even what the “social” or the “innovation” parts of it mean, let alone the concept itself [3], while others questioned if the term should be abandoned altogether [4].

Indeed, many cautionary remarks have been made about social innovation, how can be (better) used, how it should be employed, and how one can avoid contributing to the degradation of the scientific project behind social innovation research [5]. Nonetheless, there have been considerable advances, both theoretical and methodological [6]. While some weaknesses remain, we have a better grasp of what constitutes social innovation today than we did some years ago and the contribution it has had in shaping policies and investment programs, particularly in the EU, in such a short time span cannot be denied [7].

What we can safely say is that social innovation can provide tremendous contributions to public policies and new approaches to deal with social issue—something that is direly needed, while states struggle to fund social services and regain the trust of citizens disenchanted with current trends of government. Social innovation can serve both as an alternative approach to funding and maintaining public services and social sector initiatives [8], while promoting the participation and inclusion of individuals in its process and effectively empowering them [9].

Nevertheless, one of the several questions that requires more attention is the role of the state in promoting social innovation. While there is some fundamental agreement on generic aspects, deeper questions remain unanswered and it is not hard to figure why. Social innovation has only been seriously researched over the last two decades. Before that, there were some pioneer works, but widespread empirical research is still in its infancy [10]. Even with considerable funding from both national and supranational institutions [11], not enough time has passed for the results of many policies and initiatives to be fully understood and appreciated.

From the moment an idea is thought to the moment it is put into practice, months or perhaps even years might pass. However, for that initiative to provide knowledge that can inform social policies, there is a slow process behind it. This is especially the case of initiatives that deal with complex social issues [12,13] and suffer a long process from project to implementation and then evaluation, before that experience is ready to be assimilated by policies and the state. For this reason, it has been quite difficult to study how isolated social initiatives might inform social policies and how the state can learn from such experiences and upscale social innovations.

One of the difficulties in addressing this issue is that there are different perspectives involved when one talks about the role of the state in the promotion social innovation. Someone who holds an administrative office in the central state likely has a different view of the process of social innovation of someone who works on the field. Local public institutions also might have different understandings as well. A deeper understanding of the multi-level role of the state in social innovation is relevant for designing and implementing better policies. Since social innovation has become such an integral aspect of social policies over the last few years, detecting the differences in understanding and the issues that both practitioners and policy-makers or financing entities have when dealing with social innovation is paramount to assure that social innovation is explored to its full potential.

This idea applies to the Portuguese case with particular relevance. Portugal was one of the first countries in Europe to create, in 2014, a program using European Structural and Investment Funds (ESIF) to promote social innovation and social entrepreneurship: the Portugal Social Innovation program (Portugal Inovação Social) [14]. Not only that, but recent legal changes have been introduced in the social sector, such as the creation of the Framework Law on the Social Economy in 2013 [15]. These major events, as well as other smaller ones, have changed how the country deals with social innovation.

The goal of this article is to contribute to the understanding of the role of the state in the promotion of social innovation by exploring the different perspective of key stakeholders in the Portuguese social innovation scene. We present the major conclusions of a focus group conducted with key figures of public institutions responsible for the funding and coordination of social innovation initiatives, as well as with representatives from the major third sector organizations that work with social innovation in Portugal. The participants are principal figures in the national social innovation landscape and have influenced much of what has transpired in regard to this subject over the last few years. This article is an exploratory attempt to highlight avenues for the research on social innovation, the role of the state and the multi-level interactions.

The article is organized as follows. It starts by discussing the theoretical underpinnings of social innovation and the role of the state in its promotion. Then it delves into the EU and Portuguese social innovation contexts, stressing major transformations that affected the subject. After that, it presents the key findings from the focus group, highlighting key differences between practitioners and actors from different levels of the state. The article ends with some conclusions and future research directions.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Social Innovation: An Overview

Social innovation is difficult to describe, given the many connotations of the term. It can refer to a process, a research field, a concept, or a phenomenon, to name but a few [16]. The definitions of social innovation are also remarkably flexible, often being shaped to suit whatever the goal is at any given time, even in research.

Social innovation origins can be traced back to the late XIX century social revolutions that occurred in the awake of events such as the Liberal Revolutions, the Industrial Revolution or the rise of worker’s movements. The late XIX century and early XX century saw the term innovation and spin-offs such as social innovation and social invention be used to designate social transformations or social reforms, always in a descriptive manner, seldom being defined or used conceptually [17].

In the late 1930s, the term would go out of fashion for a few decades and return in the 1960s and 1970s. While innovation eventually became associated with technology and businesses, social innovation turned into a more obscure notion [18]. Today, it is often assumed that social innovation is a subproduct of innovation, when historically, innovation was first used to designate social processes and transformations and only later became eponymous with technology [19].

By the 1980s, there was a growing awareness of several issues that have since then become defining of our time: climate change, sustainability, new forms of migration, human trafficking, the crisis of the welfare state, the cyclical crisis of capitalism, the growth of anti-systemic movements, among others. Many of these problems have proven extremely difficult to solve or even to mitigate and have since then received a great deal of attention by the scientific community and policy-making.

It would not be until the end of the 20th century that social innovation would become a subject of interest in academia, as the notion held the promise of being able to assist in the resolution of some of the pressing issues of the time [20]. It is by no means coincidence that social innovation is associated with sustainability or the improvement of individual lives: it grew in this particular context and developed with the goal of being a problem-solving tool [21].

Since the 2000s, a prolific literature on social innovation has been developed, which warrants some caution when working with the different disciplinary traditions that pervade the field. Still, social innovation is nothing if not an interdisciplinary concept and field of research [3], given that it is often conducted by teams of individuals with different disciplinary backgrounds, integrating different perspectives, techniques, and data-sources of two or more specialized knowledge fields [22].

It is noticed that there was an evolution of the concept over time. Some authors and academics worked in order to answer the challenge of defining the concept hermeneutically and methodologically, putting it on the social, academic, and political agendas. Authors such as Mulgan et al. [23] prioritize social innovation as a new idea, working in order to respond to unmet social needs. However, the evolution of the concept led to considerations that it uses shared and co-produced knowledge, which can be innovative both in its ends and in its means [24], culminating in a process that stimulates change in social relationships involving new ways of doing, organizing, knowing, and framing social needs [25], in turn, giving rise to processes or programs that alters the basic routines and the beliefs of the social system [26].

However, while social innovation is often seen and discussed for its potential to promote inclusion, development and sustainability, as with any tool, it can be misused. There have several cautionary remarks about the potential for social innovation to support the ever-growing trend of public withdrawal from social services [3,27,28,29]. As social innovation is often used as a policy design tool to find new means to fund and support alternatives to public services, there has been a growing number of authors questioning if social innovation is not furthering neoliberal interests [30]. This side of social innovation—and, indeed, of innovation in general—is often overlooked, as the discourse on social innovation tends to stress the positive dimensions and hide the less desirable outputs [31] which has been called the pro-innovation bias of innovation [32].

The article takes the contributions of the different traditions of social innovation research and combined these perspectives, with the operationalization of the concept in mind. Social innovation is understood by the authors of this article as an idea that deliberately attempts to better satisfy explicit or latent social needs and problems, resulting in new or improved capabilities, and in the transformation of social and power relations, aiming at social change and the establishment of new social practices that positively affect the lives of individuals [1,5,33,34]. This is by no means a definitive definition of social innovation, assuming that such an ambition is even possible. Instead, it is broad enough to encompass most case studies of social innovation, while attempting to underline what the “social” part of social innovation actually means. It also does not imply that all social innovations are successful or have only positive consequences. This article is centered on the challenges of the state in the promotion of social innovation.

2.2. The Role of the State in the Promotion of Social Innovation

Social innovation was rapidly appropriated by political discourses and transnational institutions that saw its potential to deal with pressing social issues. Becoming something of a buzz-word over the last decade [35], social innovation has, nonetheless, become a staple of contemporary social policies that seek to employ sustainable and ground-breaking approaches to deal with complex social problems [10].

Some authors have also questioned if this growth in popularity within political spheres and transnational institutions is not due to its potential to promote alternatives to the state and public social services, becoming a sort of compensatory mechanism that serves as a form of “caring liberalism” [30,35,36], an argument that gained attention following the 2008 crisis and ensuing austerity measures employed in the European Union and many other countries, as reducing the weight of the state has been frequently pointed as the path to entrepreneurship and innovation [33].

Regardless of whether we subscribe to this argument or not, social innovation has proven to be a reliable approach to find alternatives to the state funded social services. It is particularly effective due to its flexibility and ability to involve multiple actors, at different levels, to provide a specific answer to local issues, hence why social innovation is often labelled as being at its best at a territorial level [25] rather than being attempted at a macro, more abstract level.

If social innovation’s goal is social change through the transformation of social and power relations at multiple levels, it is still, in itself, dependent on the larger political, social and cultural context, with the state often playing a key role in promoting, diffusing, integrating or hindering social innovation [2]. This was the case when welfare states were established in the aftermath of the Second World War, with great emphasis put on the defamiliarization and decommodification of public services [37].

There are different perspectives on the role of the state regarding social innovation. While some argue that social innovation is very much driven by individuals or organizations that work in the field, rather than by systemic factors determined by the state and governance [38], others argue that without a favorable political and legal context, social innovations are not only sparse, but can be actually hindered [39].

Nevertheless, this articulation is far from being reduced to a dichotomy between agency and structure. Often, articulation is possible through multiple formats. Hulgård and Ferreira [40] distinguish four different ways of relating public policy to social innovation: the volunteerism discourse that emphasizes the role of agents in the process of social innovation; social movement discourse, anchored on the same principles as the previous one, but where the state must create a nurturing environment so that collective action can arise; the new public management discourse seeks to fill the bureaucratic and vertical tendencies of the state through the creation of mechanisms that are oriented towards a social rationality of the markets; and the new public governance discourse that seeks to reform the state towards shared governance through inter-organizational networks.

Others emphasize the question of power and the difference between using that power to change/create something new or to reproduce what already exists [41]. A distinction is, thus, made between different types of power. The power that is reinforcive and that underlines the capacity of the structures to reproduce, the one that is innovative and that refers to the ability to create something new, and finally, the transformative power, which implies the ability to change structures and institutions.

These distinctions, however, continue to mark a tight reading and the definition of concrete roles that the state and social innovation actors are not always able to assume. Social innovation, as mentioned, must be understood as a multi-actor and multi-level process and not a static, unidimensional phenomenon. This also means that social innovation does not only depends on the will of the actors who develop and implement it, but on institutional conditions that support it. Van Wijk and colleagues [13] propose a model in three dimensions: a micro level that refers to the agents of the field, a meso level that refers to the way they articulate with others, and a macro level that refers to the institutional contexts that guide, or even discipline the dynamics of the micro and meso cycles.

This shows that, in fact, assessing the role of the state in social innovation is not an easy or immediate task. The role of the state itself depends on a historical path dependence. Different types of state assume different stances on what can and should be made to support social innovation. Post-war governments were interested in promoting welfare services, following Keynesian principles, but this changed greatly after the 70s, prompting what has been called the “crisis of the Welfare State” [42]. Since then, a trend of reducing public expenditure on social services has lived side-by-side with local bottom-up movements [37]. More recently, realizing the need to find lasting solutions, governments began working towards creating structural conditions for growing the social sector, aiming at finding alternatives to public social services.

Issues such as power [41], empowerment [43], and risk [44] gain particular prominence in this discussion because it is the actors’ perception of these dimensions that will shape the role they are predisposed to assume. The argument that the state should not only play an active role in the promotion of social innovation, but be itself an entrepreneurial state, [44] such as the idea of hybrid organizations that combine multiple organizational formats [45], has resounded well with researchers, practitioners and even with policy-makers over the last few years. This discussion is centered around the notion of the state taking risks in the promotion of social innovative approaches to deal with complex problems and fostering cooperation with private and third sector organization [46]. The difficulty of the state assuming an entrepreneurial mindset lies in the inherent risk-taking aspect of entrepreneurship [44], something that the state avoids by design.

For this reason, and also in our exploratory case study, policies that govern social innovation and social entrepreneurship tend to be rather conservative in both risk-taking and uncertainty management. This often hinders the process of innovation, forcing organizations to opt for more conventional solutions instead of novel ideas: something that is the antithesis of social innovation. It is in this sense that the third sector gains prominence, since they have the ability to function as an intermediary institutional space between the state, the market, and civil society [43], working as actors pushing for public policy design.

3. Social Innovation and Public Policy in Europe and Portugal

3.1. Social Innovation in the EU

Social innovation has taken on an increasingly relevant role in contemporary societies, which is also reflected in the European Union’s (EU) public policies and agendas. Since the early 2000s, the European Commission (EC) has sought to introduce the ideas underlying the concept of social innovation in its strategic documents. The Lisbon Strategy (2000) represented a milestone in the attempt to convert the European economy into growth based on cohesion. Subsequently, the Renewed Social Agenda (2008) sought to reconcile Europe’s productivity and economic recovery, with a focus on innovation, social and environmental renewal.

However, it was from the 2014–2020 programmatic framework that the notion of social innovation started to assume a central role in European strategic documents as a crucial dimension for social development and economic growth. This programming period was marked by the need to address the consequences of the economic crisis of 2008, mainly at the level of the social sector, due to the severe austerity policies that some member-states suffered (as was the case with Portugal). Thus, social innovation began to be seen as a tool for public policies and the Bureau of European Policy Advisors (BEPA) [47] report contributed to give form to this vision. This importance was consolidated by the Europe 2020 Strategy, underlining a multidimensional and integrated growth that is simultaneously smart, sustainable, and inclusive [48].

Among a set of key initiatives on this agenda, the Innovation Union stands out. This initiative, together with the Social Investment Package, has largely influenced the social innovation actions of the EC. The Innovation Union, with more than 30 actions, has as its main objective to redirect the research and development (R&D) and innovation policy to respond to Europe’s pressing challenges, namely, climate change, efficiency in energy consumption and resources use, health, and demographic aging. Horizon 2020 (H2020) is one of the most relevant instruments which emerges as a cornerstone of the Europe 2020 Strategy. This EU’s research and innovation program, in addition to the lines of scientific excellence and industrial leadership, is highly oriented towards overcoming social challenges, supporting innovation in its different stages of development, namely, modalities of innovation in the public sector, and social innovation [48,49].

This trajectory shows that support instruments represent the key in the promotion, diffusion, and integration of social innovation. This turned out to be successful in several ways. On the one hand, these initiatives made it possible for new ideas, practices and projects to become achievable, contributing to the maximum objective of social innovation, (i.e., that of introducing social change), on the other hand, they contributed to an opening to new perspectives and the relevance of the subject.

3.2. The Portuguese Case

The evolution of social innovation in Portugal can be understood through one overarching trend in the Portuguese State and on key event in recent years. The first concerns Portugal joining the European Union in 1986 and, since then, concentrating efforts into modernizing public administration, the state apparatus and enacting specific policies to deal with the social issues that stemmed from nearly five decades of dictatorship that lasted until 1974 [50].

One aspect of this process that has been the subject of interest over the last decade has been the growing trend of Europeanization of social policies adopted by Portugal [51], which explains, in part, why Portugal was one of the first countries to heed the recommendations of the EU regarding social innovation. It also contributes to understanding the key event that triggered the implementation of social innovation in Portugal: the 2008 financial crisis and the ensuing bail-out program enacted by the International Monetary Fund, European Central Bank, and European Commission, the lasted between 2011 and 2014.

The bail-out deal included several austerity measures that severely crippled the country’s capacity to provide social assistance to the population struggling with the effects of the recession and record unemployment values. The social sector was also affected, as public financing lines and contracts suffered cuts [44,52]. As the situation escalated, the sector began searching for alternative means of funding. Social innovation stood as the possible alternative and it is no coincidence that the Portugal Social Innovation program was launched in 2014, as the social problems caused by the recession and the bail-out deal were still felt [53].

Since 2014, the Portuguese social sector rebounded and a new generation of social policies were enacted since then, relying heavily on social innovation as a necessary component for third sector organizations to obtain funding for their activities. Furthermore, while there were several cases of social innovations promoted before 2008, the crisis served as a catalyst for the social innovation paradigm of social policies and funding for social and third sector organizations, something also demonstrated by the Framework Law of the Social Economy enacted in 2013 [27,54].

Being one of the countries most affected by the consequences of the 2008 economic crisis and by the ensuing austerity policies, it was important in Portugal to foster a social sector that was sustainable and that responded effectively to social needs. It was in this context that Portugal Social Innovation program (PIS) was created. The main objective of this initiative was to develop and stimulate the social investment market to support entrepreneurship and social innovation initiatives in Portugal, approaching the New Public Management Discourse model [40].

One of the great assets of Portugal Social Innovation, in addition to financing, is to provide a partnership relationship between investors and social entrepreneurs, also enabling direct or indirect influence on public policies. Mobilizing around 150 million euros from the European Social Fund, within the scope of the Portugal 2020 Partnership Agreement. More specifically, the mission of Portugal Social Innovation is the promotion of entrepreneurship and social innovation to generate complementary responses to solve social problems; the animation of the social investment market, through the creation of financing instruments adapted to the specific needs of the sector of the social economy and projects of innovation and social entrepreneurship; and the training of actors in the innovation and social entrepreneurship system, contributing to its economic and financial sustainability.

To achieve these objectives, the PIS was organized into four financing instruments: capacity building for social investment (oriented towards the development of skills related to effective project management); partnerships for impact (intends to offer support through the partnership, in the form of co-financing with investors regarding the creation, implementation and growth of projects); social impact titles (for projects in priority areas of public policy, such as employment, social protection, education, health, justice and digital inclusion); and the fund for social innovation (allows easier access to credit and co-invests in organizations with projects undergoing consolidation or expansion).

Although still recent, this policy experimentation has shown interesting results. Data available from Portugal Social Innovation (https://inovacaosocial.Portugal2020.pt) sums that there are currently 465 social innovation projects financed by Portugal Social Innovation, with a social investment of 21,713,177 EUR and a total of 59,061,972 EUR from Portugal 2020. These projects are distributed across the regions of Norte, Centro, Alentejo, Algarve, and multi-region, and fall into one of the following areas of intervention: citizenship and community, education, employment, social inclusion, social innovation incubators, and/or justice and health.

The Portuguese social innovation landscape has changed a great deal over the past few years. There is still a great potential to continue this process of change, mainly using this type of formal mechanisms. With the impacts of the crisis, there is a need to rethink the social sector arose and the debate on social innovation and the social economy grew in importance.

The Portuguese social and solidarity economy sector has become more significant to the national economy over the last few years as well and encompasses several types of organizations. These organizations have worked with the state in assuring the provision of welfare services, both during the late monarchy days in the 19th century and before the democratic revolution of 1974 [27]. This is more so the case of older legal forms, such as mercy houses, charitable foundations, social cooperatives, and welfare associations, which assumed a more important role after 1974.

As usual, in times of crisis, the social sector tends to renew itself and gain relevance. This was the case after the 1974 revolution and again in the aftermath of the 2008 crisis. These organizations gained a renewed interest due to political attention devoted to the social economy and the cutbacks on public spending and social services in general dictated by the financial assistance program negotiated with the European Central Bank, International Monetary Fund and European Commission [30].

Recent data provided by the Satellite Account of the Social Economy (INE/CASES, 2019) shows that the social economy sector, in 2016, represented 3% of the Portuguese Gross Value Added (GVA), 5.3% of remunerations and total jobs, and 6.1% of paid jobs. If we analyze the period between 2013 and 2016, this growth in importance becomes even clearer. The report highlights that there was an increase of 17.3% in the number of entities that comprise the social economy sector in relation to 2013, as well as increases in GVA (14.6%), total jobs (8.5%), and paid jobs (8.8%). These values grew above the national average during this period and show a clear positive evolution of the social economy sector in the country and its importance to the economy, despite the cries that the solidarity sector is in financial trouble. Health and social services were the largest contributors to these results, representing 48.89% of the sector’s GVA. Education follows as a distant third, representing 13.92%, as Table 1 shows.

Table 1.

Types of organizations in the social and solidarity economy in Portugal.

The data show the evolution of the Portuguese context. Moments of crisis also represent moments of rethinking models and paradigms, as well as providing an opportunity for deeper transformations. Europe in general and Portugal in particular have been able to make this conversion. However, this has not happened without some tensions. In fact, new contexts, new models, and new opportunities, also represent a new role that different stakeholders are asked for. In crystallized structures, with a certain path dependence, taking on and developing these roles can be a challenge.

4. Social Innovation and the Role of State

4.1. Methodological Considerations

To explore the understandings of different stakeholders about the role of the state in the promotion of social innovation, a focus group was held (Coimbra, Portugal, 9 May 2019) with several key-actors from the Portuguese social innovation landscape.

This method was chosen for two particular reasons. On the one hand, the focus group allows easier access to groups with very specific characteristics, in a relatively closed context [55] On the other hand, it is a technique that allows to understand the collective perspectives, with the objective of sharing their experiences and also allows to dilute the power imbalance between the researcher and the interviewees [56].

The selection of the group participants must follow previously defined criterion that should keep in mind that the main objective of focus group is to stimulate discussion and provide comparison between different types of actors. This is paramount to assure diversity from which contrasting experiences result, thus fostering conversation and discussion between the participants. Ideally, the researcher should seek sufficient diversity within the group to stimulate discussion and sufficient homogeneity to facilitate comparison between types of actors [57].

With these considerations in mind, three types of participants were selected: national and regional governance bodies, municipal bodies, and third sector organizations that develop social innovation projects in their territories. The participant organizations are listed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Description of the Participants.

A3S and Microninho are two of the most prominent social sector organizations that work with social innovation, having vast experience in the sector and having hundreds of experiences with specific projects, initiatives and other social and solidarity sector organizations. CCDR-Centro is one of the five CCDR that exist in the Portuguese territory, one by each mainland NUTS II, standing as autonomous sections of the state and playing major role in the implementation of European funds and working with local public, private and third sector organizations to promote development, investment and sustainability in the Centro region. CIM Ave is an intermunicipal community that represents 9 municipalities, with a population of 425,000. Often associated to NUTS III level, intermunicipal communities play an important role in the coordination of policies and pooling of resources from the partner municipalities, who use this forum to promote partnerships and territorial development strategies. PIS is the principal funding mechanism for social innovation and social entrepreneurship in Portugal, created for that sole reason in 2014 and being responsible for financing and evaluating the vast majority of social innovation initiatives in Portugal, thus being the nexus of social innovation in Portugal.

The focus group was designed in order to provide answers to three specific questions: (1) how is the sustainability of social innovation achieved? (2) how successful have been the efforts to establish networks of cooperation and coordinate between public, private and social sector organizations, that contribute to social innovation initiatives? and (3) what territorial-related restrictions have been found when promoting these initiatives?

These questions, in turn, allowed the moderation to steer the focus group in the appropriate direction, as so to keep the conversation topical and maximize relevant contributions to the subjects at hand. Still, the focus group took on a flexible character to make the participants feel comfortable, something imperative as they represented often opposite roles in the implementation of social innovation. For this reason, it was necessary to proceed with caution to avoid tensions and confrontations that could undermine the process. The focus group was carried without any issues and in a fertile climate of dialogue and mutual understanding for the different roles and responsibilities that all the participants had.

The participants were previously aware of all the questions in order to prepare their answers beforehand. Direct interpolation between the participants was allowed. The answers were transcribed and analyzed in order to identify significant differences between the perspectives of the representatives from state institutions and those of social organizations. We contrasted these differences with the theoretical underpinnings of social innovation and selected the most relevant for this article, in the awake of the Portuguese experience. Consolidation of the results was done with documental analysis. The considerations herein contained are the reflexive summary of the discussion that took place during the session.

4.2. Main Findings

The debate started from the central argument that one of the advantages of the notion of social innovation is its ability to stimulate reflection on new ways to shape and reorder state-society-market relations. However, this reorganization is embedded in a set of problems deeper than they appear. The focus group was a participatory moment around three main points, relevant to reflect on the role of the state in social innovation: sustainability, networks, and territory.

4.2.1. Sustainability

It is important to clarify that the “sustainability” dimension was mainly understood by that participants as the financial sustainability of the organizations to operate in the field. In this sense, it sought to reflect on the sustainability of practices, dynamics and activities of social innovation. Far from being an exclusive phenomenon of the business sector, social innovation, in its practical dimension, is widely conducted and operated by third sector organizations. These organizations often assume economic models based on the social economy. However, today it is possible to perceive that the social economy approach tends to fail, incapable to fulfil its initial purpose of being an economic alternative demarcated from the market and autonomous logics vis-à-vis the state. Third sector organizations tend to be overly state-dependent, reliant in public transfers, as in the case of cooperatives, and, more recently, social enterprises.

In this sense, the discussion tried to explore, on one hand, how governance actors can help social innovation to move away from this logic and function as a form of empowerment and means to promote sustainability, and on the other hand, what is the role of governments, at different territorial levels, in the internalization of the responsibility for promoting social innovation. These issues are particularly important as one of the main social innovation purposes is, precisely, the restructuring of social and power relations, and the empowerment not only of its beneficiaries but of its promoters as well [58].

One of the first conclusions of the discussion was a dichotomous understanding between the actors in the organizations that intervene in the field (Microninho and A3S) and the actors who take on more formal positions of orientation, coordination, or financing of social innovation projects (as Portugal Social Innovation and CCDR Centro). CIM Ave took a more intermediate position, mostly due to the characteristics of the entity itself, also serving as the moderating actor and bridging the two opposing perspectives. This factor may indicate that although the literature suggests that third sector organizations often are the most qualified to function as bridges [43], in this case, it is the local governance organizations that may play this role, mediating what is being the actors in the field and macro-level bodies.

The debate focused on the “push” of financial sustainability. This means that organizations are often required to develop social innovation projects to ensure their own financial stability. This has risks and distorts the mission of organizations that must respond to the challenges of their territories and let innovation emerge from the bottom-up actors, but also feel pressured by financial constraints. This prevents the process from occurring in an articulated manner. Another risk highlighted was the gap between the “time” of public policies and the “time” of social innovation. Social innovation is dynamic, and it is therefore untenable to expect public policy to be socially innovative. While this is the perception, one participant (P1) affirmed that “(…) true financial sustainability does not exist. This argument starts with the uncertainty, the dynamism of social innovation and with the gap in the involvement of various actors. Social innovation can only be done in a quadruple helix logic”.

However, this view brings another known limitation. There is a growing wave of social enterprises and social innovation strategic documents that stress its multi-actor characteristic, that must have a business component and an explicit economic value, while solving a social need [47]. In fact, one of the purposes of PIS is to promote social innovation and boost the social investment market in Portugal. However, these actors suggest that there is a confusion between what is an association and what is a social enterprise. In fact, they argue that social enterprises and associations are different things that are not at the same level, since, although both work on a logic of satisfying social needs, social enterprises seek profit and associations do not. According to a representative of a practitioner organization: “When these mixtures are generated, when all this is shuffled, it becomes a very complicated and difficult to manage climate”. These mercantile logics not only hinder the development of social innovation, but reshape its meaning altogether, paving the way for social innovation becoming a tool for public spending cutbacks and the commercialization of welfare services [26].

Conversely, the actors representing the governance sector highlight the importance of articulation and the involvement of private partners. To this end, they argue that the crucial to social innovation is to boost the social investment market and to bring about inter-sector partnerships between public and private partners. Partners such as the state, the social economy and the private sector cannot be seen only as funders, but as partners in mobilizing resources that allow a more structured bet on these initiatives.

Sustainability of the state itself was also evoked. The challenge of economic sustainability the state faces is transversal to all areas, as are the limited public funds. That is the reality public workers and administrators must face. This challenge is directly associated with evaluation and metrics. As the CCDR Centro representative underlined “On the side of those who are managing funds there are two alternatives: gaining scale, gaining size, relevance and involving different agents to work on common projects”. Furthermore, often, this articulation is neither flexible nor possible. For the Portugal Social Innovation representative, this issue of sustainability is immersed in a set of misunderstandings. Thinking only of sustainability as a financial need corrupts the very purpose of social innovation: “what is important to be sustainable is the result of the innovation that has taken place, not the organizations that have developed it.”

4.2.2. Networks

These reflections highlight another set of dimensions, directly related to cooperation and the creation of networks. It is latent that, although a series of articulation efforts have been made, in which Portugal Social Innovation serves as a reference, coordination between the different levels that constitute the social innovation landscape is still far from being easily achieved. Social innovation advocates coordination and cooperation between actors to reach its ultimate goal: the creation of social and economic value and the introduction of systemic changes. In order to achieve this goal, the state has to evolve beyond funding, particularly in promoting the introduction of systemic change or scalability of social innovation practices.

In this way, the actors on the field posed social innovation as a process of “financialization” of social policy [59]. This argument is based on the idea that innovation is more focused on specialists and metrics, and less on the people whose lives it tries to improve. This question of metrics was fundamental in the discussion and intersects with the dimension of the time gap between the public policies and the social innovation. This is because there is pressure, notably on funded programs and governance bodies, for measuring the impact of interventions in a timely manner. According to a representative of a social innovation field player: “measuring impacts is fallacious and from the methodological point of view there is no consensus on the part of the scientific community on how to measure social impacts”. Stakeholders argue that indicators of achievement are often confused with impact indicators. Public policy is responsible for giving a time window to include criteria, such as co-responsibility and participation, because, “what we see on the ground are hybrid and plural things and public policy has to go look for them”.

However, the governance sector argued around the risk of innovation. What is new and innovative has always associated risks and this is something that has also been debated as an embarrassing element of the more articulated relationship between governance bodies and social innovation initiatives. This happens because Portuguese funding structures tend to be conservative and bureaucratic, and despite these characteristics they still have to finance innovation that involves both risk and error. This represents a great paradox because it is not often possible that the financial flows respect the timings of the organizations and even if a social innovation initiative has the potential to be successful in the long run, the metrics stress more immediate results, that can demonstrate that success in a timeframe often incompatible with complex initiatives that deal with structural social issues and take years to show results, way beyond the timeframe of the financing programs.

4.2.3. Territories

Practices of social innovation are generally territorialized, of local and community origin, operating in a micro logic of responding to needs. This means that there is a high diversity of social innovation practices, as diverse as the number of social issues that can be found in any given territory. How can different levels of governance account for this diversity? Does it require more decentralization of public policies or a new way of looking at the territory and building bridges between “local” and “universal”?

The municipality is, according to all participants, the privileged place for social innovation. However, it was noticeable in the debate that there is a tension between the top-down and the bottom-up perspectives. According to the participants, a formal way of reducing this tension is to view the municipality as a space that could (and should) function as a bridge between the field and policy-making, contributing to its implementation. It is more effective to work locally than centrally, given that the needs of the territories are individual and localized. In this way, for municipalities, more important than to act as funders is to align partners and promote networking: “internalizing the role of a paradigm shift, compelling the community to reflect on what is social innovation, forms of financing are functions that CIMs (Intermunicipal Communities) have to assume” (as refereed by the CIM Ave representative). This, however, presents two main challenges: to work the innovative capacity of the people who manage the municipalities and to respond to the heterogeneity of the territories themselves.

On one the one hand, there is a set of non-governmental organizations that develop their work with the ultimate objective of meeting the needs of the territories. These associations recognize the importance of public policies, but underline that they are not on in synch with the actors and territories that must be taken into account in future discussions. On the other hand, there is the position of representatives of governance bodies and the formal instruments of support for social innovation. The major argument common to these participants is the difficulty inherent in supporting and promoting social innovation. These difficulties are mainly reflected in the fact that we are facing a new framework, a concept and a process that implies a new way of looking at territories, problems and the way we solve them. The CCDR Centro representative illustrated this difficulty in stating that “social innovation issues were consolidated in this programming period and even now, there are things we do not know how to implement. We have more familiarity working with municipalities in a traditional logic of supporting infrastructure, economy, exportations, companies”.

However, both acknowledge that while there are such misconceptions, sustainability is important so that organizations can organize themselves for the future and continue to develop their function because, as already mentioned, innovation and public policy work in different time-frames. It is in this sense that the importance of partnerships between the third sector and private companies is strengthened. This is because “it is wrong to think that the state has money and skills for all problems, as it is wrong to think that all social problems are solved with non-lucrative projects” (Portugal Social Innovation representative).

4.3. Discussion

The literature review and the results from the focus group suggest that social innovation can lead to economic growth, improved well-being and the “transformation” of societies; however, as a concept and practice, it has not been exempted from criticisms and its social, economic and institutional value varies according to the perspectives of the social actors. Despite growing attention from public strategies and policies, much of the discussion on social innovation remains vague and with some level of discrepancy, and its vision is “congested” according to the “gaze” that the different actors who intervene on the field use. For many, it is simply a new term for the study of non-profit organizations; for others, it can include almost everything, from new forms of democratic participation to the design of products accessible to low-income consumers. For a wide range of practitioners, it is nothing more than a (disguised) attempt to commercialize activities that were in the sphere of the social and solidarity economy or under the responsibility of the state. In the perspective of this article, social innovation was deconstructed and demonstrated as a willingness to transform ideas into action to respond to social needs. Thus, it can be a purely incremental solution, but it can also cause systemic change, which alters the fundamental foundations of society by reshaping social and power relations, resulting in transformative social innovation [2].

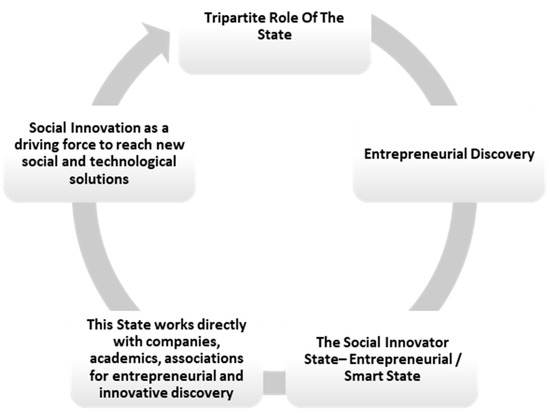

The interpretation of the exploratory investigation and the relevance and “place” that it is intended to give to social innovation within the state suggests the relevance of a hypothesis of social innovation as a possible driving force of an Entrepreneurial and Smart State [44] and vice-versa (Figure 1). Thus, it can and should be a driving force in the emergence of an Entrepreneurial and Smart state, as well as the state should play a fundamental role in the dissemination and support of social innovation projects that will lead to economic, social and technological growth. The diagram below shows the perspective and direction in which this article intends to direct future research. As suggested throughout the text the classic and old-fashioned view of the state must be open to entrepreneurial discovery [60], culminating in a new type of approach, working directly on social and economic well-being from risk-taking and innovative perspectives, where social innovation can play a prominent role. We suggest the possibility of a “Social Innovator State”.

Figure 1.

Social innovation and the role of the state. Source: own elaboration.

However, the results revealed that social innovation in policy and practice also brings more as well as new challenges. The tension resulting from the “lag of the time” between the process itself and the organizations, and governance bodies and public policies is crucial to address. The great challenge that has remained latent in this discussion is the inexistence of public mechanisms that allow the transfer of social innovation projects and outputs to public policies.

Neither social innovation nor the phenomena we describe as such are really new. Innovation refers not only to novelty, but also to the reinvention of things and/or the recombination and reframing of old things in new contexts and frameworks. The added value of social innovation is not only its outputs nor its objectives: societies have always sought to satisfy social needs, namely, through the third sector, often analyzed in the light of the social and solidarity economy. The differentiating issue is the process. Social innovation must be social in its ends and in its means (participatory, inclusive methods, with horizontal structures and representativeness). How are we ensuring, in our investigations, that the means are really innovative? Furthermore, to what extent is this a necessary condition to describe and classify a practice as social innovation?

Social innovation is described as a process, product, technology, that satisfies a social need and that ultimately leads to social transformation, to systemic change, but this change is not without risks. In this sense, to understand the transformative potential of social innovation, we must look closely at power relations. How and to what extent are problematic power relationships (inequality, oppression, exploitation, exclusion, injustice) really being challenged or reproduced by new forms of social innovation?

Furthermore, finally, the question of systemic change and social transformation that arises not only in the context of social innovation, but in the context of transformative social innovation as well. We know that the systems are diverse and can assume different scales, but what systemic change are we talking about? These questions can only be answered when this articulation between the state and social innovation obtains more definition. There is a pathway—for social innovation—that is still in its infancy and needs better understanding of its own “time”. This is a time that must be respected and internalized by all actors, in particular, to achieve the great purpose of achieving a real systemic transformative social change.

While Portugal has developed specific instruments for the purpose of fostering social innovation, notably the Portugal Social Innovation program [14], it remains to ascertain how successful the country has been in this endeavor. Portugal Social Innovation has yet to be evaluated and while the figures are seen as positive, the actors that have made use of this and other programs, both national and European, maintain contrasting perspective.

5. Conclusions

5.1. Conclusive Remarks

While social innovation research has come a long way, it still far from being the useful scientific concept academia desires or providing a clear framework for public policies and transformative change. These frailties were apparent in the opinions of the key-actors that participated in the focus group. That created an opportunity to start a conversation between key-stakeholders from the micro, meso, and macro level [13] and identify if there were, indeed, notable differences and discrepancies in how they saw and understood social innovation. The perspective from the representatives of the state differed considerably from that of representatives from third sector organizations and public institutions, which operate on the field and deal with the social problems in a more direct manner. However, this also shows internal discrepancies as different levels of the state have different perceptions about social innovation.

To begin with, how social innovation is understood varies greatly as we go from top level institutions to actors working on the field. While some degree of difference is to be expected, given the different sensibilities that different institutions and organizations have when working with social innovation, when this distance increases significantly, it becomes more difficult to find a common ground with which people can work. This, in turn, translates into different priorities and approaches to how social innovation initiatives should be implemented, measured and incorporated into legislation or scaled up.

Organizations that operate at a micro-level also find themselves depending on projects to ensure financial stability, which can lead to a dependency on specific financial determinants. If a crisis strikes, for example, implementation of national and EU programs might be affected, resulting in an overall disinvestment on funds for social innovation. This debility was acknowledged during the focus group, with the actors admitting that this might distort how organizations meet the challenges in their territories, undermining the idea that social innovation emerges in a bottom-up context.

The financial aspect becomes more relevant when we consider that strategic documents on social innovation are emphasizing the business component. The economic value aspects of social innovation projects and initiatives, fuels the argument that it is being growing closely tight with neoliberal visions of the role of the state in the promotion of welfare and wellbeing [3,25,30], in what has been described as “caring liberalism” [3].

Another aspect of interest is the measurement of the success of social innovation initiatives. Public institutions and financing bodies have very limiting time windows for evaluating initiatives, which often requires organizations to show results at several stages during the financing program and more consistent data by their end. Social change is a slow process and can hardly be fully understood in a two- or three-year interval. This is more so the case in areas that show results over long time spans, not far from one or two decades in some cases. In turn, this can lead to some social problems being neglected over others, depending on how difficult it is to present results over a short time span, which result in social innovation financing policies targeting more common and easier problems than the more wicked issues to which social innovation theory so commonly refers [46].

If defining social innovation is difficult, measuring its success is far more so. It is a deeply embedded complex social process that addresses equally complex problems. Not only that, but agreement on what or how it should be measured also greatly varies according to the point of view of the interested party, i.e., macro perspective (governing bodies, public institutions, transnational organizations, etc.), micro perspective (associations, social enterprises, local initiatives, etc.) or meso (regional institutions, local governing bodies, territories, etc.) [61].

Finally, the article discussed how social innovation understandings greatly differ between bottom-up and top-down approaches. As we argued before, both perspectives are not mutually exclusive. However, social innovation can be better understood at a meso level, understood as the local/municipal, a point made clear by all the participants of the focus group. While legislative framework is vital to support social innovation initiatives, a macro approach to social innovation can lead to some of the side effects we have been discussing. Social innovation is based on meeting specific issues and those issues are spatially bounded. In other words, we can only fully comprehend a specific social innovation by putting it into context on a specific territory, which makes the local and regional scales the favored units of analysis of this process, more specifically, the municipalities.

Considering the Portuguese case, not only do municipalities possess the greater understanding of the local territory, but they can also bridge the organizations that operate on the field with the decision-makers and national institutions that create the legislation and financing programs. This relationship should be fostered. Networking around municipalities is the key to successfully implement social innovation in response to social problems.

In conclusion, the state can assume different roles at different levels. While the top level will always be the controlling party, an overly centralized approach is not only undesirable, but counterproductive as well. Organizations working in social innovation require a different kind of resources that often go beyond financial support. Municipalities and regional institutions (like the Intermunicipal Communities in the Portuguese case) can and should assume a more active role in fostering social innovation and bridging the gap between organizations that operate in the social field, governing institutions, and private investment and support.

5.2. Future Research Directions and Policy Implications

While advances have been made regarding what role the state plays in promoting social innovation, the specificities of this process are not fully understood. Between obtaining knowledge provided by social innovation initiatives and drafting legislation that uses that knowledge there is a complex bureaucratic process. Not only that, but even after legislation takes effect, there are issues pertaining to what kind of organizations and initiatives are eligible or affected, not to mention the requirements that often imply financial or manpower resources that many organizations lack.

As this article shows, even when actors from multiple levels agree on specific issues, they disagree on the approach chosen. This was the case of the sustainability of social innovation. The state requires initiatives to have a degree of financial sustainability, but organizations tend to be more focused on their own sustainability, rather on that of the initiatives themselves. This translates into an over reliance on social innovation financing lines, which, in turn, makes social innovation initiatives not a novel approach to deal with complex issues, but rather the go-to approach, in order to obtain financial support for the social organizations themselves.

The Portugal Social Innovation program has had this side-effect that requires more research, as well as how social innovation has changed social sector organizations. While our article identifies some of these issues, the results are particularly useful to countries with similar institutional architectures. More research about the roles of state in social innovation taking into consideration the variety of socioeconomic profiles is vital to inform future financing programs and make sure that social innovation remains a creative approach that uses novel solutions, instead of the standard procedure on day-to-day operations of the social sector.

Another standout aspect is the difficulties in establishing cooperation networks. The participants of the focus group admitted that the existing policy focuses solely on financial sustainability and neglects the networking aspect, with the state not being a proactive actor in promoting cooperation practices and communication amongst organizations, whether they be from the public, private or third sector.

Researching to what amount these difficulties and what possible solutions could be found would also contribute to a greater understanding of how social innovation can be effectively improved. This would also affect the territorial dimension, since even within the state, several public entities have a hard time communicating with each other. A more effective approach to overcome these problems would improve how social innovation is implemented and how successful it becomes.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.P.; Focus Group Organization, H.P.; Methodology, H.P. and C.N.; Data Organization, C.N.; Formal analysis, C.N.; Literature review, J.A.G.; writing—original draft preparation, J.A.G. and F.S.; writing—review and editing, H.P., C.N., J.A.G. and F.S.; supervision, H.P.; Project administration, H.P. and F.S.; Funding acquisition, H.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This article is inspired by the Atlantic Social Lab (ASL), project co-financed by the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF) through the INTERREG Atlantic Area Cooperation Programme under reference EAPA_246/2016. More information of the project can be found at https://atlanticsociallab.ces.uc.pt.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and followed the Ethical Considerations document approved by the Steering Committee of the Atlantic Social Lab (July 2017, Template for Mapping Regional Needs).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Acknowledgments

Hugo Pinto is thankful to the support of the Portuguese Foundation for Science and Technology (FCT) through the Scientific Employment Support Program (DL57/2016/CP1341/CT0013). Carla Nogueira also acknowledges the FCT support (SFRH/BD/117398/2016). The authors are thankful to the participants in the focus group and to the help of Sílvia Ferreira and Paola Di Nunzio (CES, University of Coimbra) in the implementation of Atlantic Social Lab.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- McGowan, K.; Westley, F.; Tjornbo, O. The history of Social Innovation. In The Evolution of Social Innovation: Building Resilience Through Transitions; Westley, F., McGowan, K., Tjornbo, O., Eds.; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2017; pp. 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Backhaus, J.; Genus, A.; Wittmayer, J.M. Introduction: The nexus of Social Innovation, sustainable consumption and societal transformation. In Social Innovation and Sustainable Consumption: Research and Action for Societal Transformation; Backhaus, J., Genus, A., Lorek, S., Vadovics, E., Wittmayer, J.M., Eds.; Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group: New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Moulaert, F.; MacCallum, D.; Hillier, J. Social Innovation: Intuition, precept, concept, theory and practice. In The International Handbook on Social Innovation: Collective Action, Social Learning and Transdisciplinary Research; Moulaert, F., MacCallum, D., Mehmood, A., Hamdouch, A., Eds.; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2013; pp. 13–24. [Google Scholar]

- Pol, E.; Ville, S. Social Innovation: Buzz word or enduring term? J. Socio-Econ. 2009, 38, 878–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cajaiba-Santana, G. Social Innovation: Moving the Field Forward: A conceptual framework. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2014, 82, 42–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peris-Ortiz, M.; Gómez, J.A.; Marquez, P. Strategies and Best Practices in Social Innovation: An Overview. In Strategies and Best Practices in Social Innovation: An Institutional Perspective; Peris-Ortiz, M., Gómez, J.A., Marquez, P., Eds.; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2018; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Asenova, D.; Damianova, Z. The Interplay between Social Innovation and Sustainability in the CASI and other FP7 Projects. In Atlas of Social Innovation: New Practices for a Better Future; Howaldt, J., Kaletka, C., Schroder, Z., Zirngiebl, M., Eds.; Orgs.; SI Drive: Dortmund, Germany, 2019; pp. 44–47. [Google Scholar]

- Berzin, S.C.; Pitt-Catsouphes, M.; Peterson, C. Role of State-Level Governments in Fostering Social Innovation. J. Policy Pract. 2014, 13, 135–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulgan, G. The Theoretical Foundations of Social Innovation. In Social Innovation: Blurring Boundaries to Reconfigure Markets; Nicholls, A., Murdock, A., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: Hampshire, UK, 2012; pp. 33–65. [Google Scholar]

- Domanski, D.; Howaldt, J.; Kaletka, C. A comprehensive concept of social innovation and its implications for the local context on the growing importance of social innovation ecosystems and infrastructures. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2020, 28, 454–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massey, A.; Johnston-Miller, K. Governance: Public governance to social innovation? Policy Politics 2016, 44, 663–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Backhaus, J.; Genus, A.; Wittmayer, J. The nexus of social innovation, sustainable consumption and societal transformation. In Social Innovation and Sustainable Consumption—Research and Action for Societal Transformation; Backhaus, J., Genus, A., Lorek, S., Vadovics, E., Wittmayer, J., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Wijk, V.J.; Zietsma, C.; Dorado, S.; Bakker, F.G.A.; Martí, A. Social Innovation: Integrating Micro, Meso, and Macro Level Insights from Institutional Theory. Bus. Soc. 2019, 58, 887–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, F.; Santos, F. Portugal Inovação Social: Na Encruzilhada dos Tempos. Coop. E Econ. Soc. 2017, 39, 443–462. [Google Scholar]

- Meira, D.A. The Portuguese Law on Social Economy. Available online: http://www.socioeco.org/bdf_fiche-document-4127_en.html (accessed on 19 January 2021).

- Benneworth, P.; Cunha, J. Universities’ contributions to social innovation: Reflections in theory & practice. Eur. J. Innov. Manag. 2015, 18, 508–527. [Google Scholar]

- Godin, B. Innovation in Post-Revolutionary France, Project on the Intellectual; History of Innovation; INRS: Montreal, QC, Canada, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Westley, F.; McGowan, K.; Tjörnbo, O. The Evolution of Social Innovation: Building Resilience through Transitions; Edward Elgar: Cheltenham, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Godin, B. Innovation Contested: The Idea of Innovation over the Centuries; Routledge: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Cooperrider, D.; Pasmore, W. The Organization Dimension of Global Change. Hum. Relat. 1991, 44, 763–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, S.; Mehmood, A. Social innovation and the governance of sustainable places. Local Environ. Int. J. Justice Sustain. 2015, 20, 321–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerreiro, J.A. Interdisciplinary Research in Social Sciences: A two-way process? In Proceedings of the International Congress on Interdisciplinarity in Social and Human Sciences, Faro, Portugal, 5–6 May 2016; pp. 209–213. [Google Scholar]

- Mulgan, G.; Tucker, S.; Ali, R.; Sanders, B. Social Innovation: What It Is, Why It Matters and How It Can Be Accelerated; Skoll Centre for Social Entrepreneurship Working Paper; Oxford Said Business School: London, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- The Young Foundation. Social Innovation Overview: A Deliverable of the Project: “The Theoretical, Empirical and Policy Foundations for Building Social Innovation in Europe” (TEPSIE) 2012, European Commission—7th Framework Programme; European Commission, DG Research: Brussels, Belgium, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Haxeltine, A.; Pel, B.; Wittmayer, J.; Dumitru, A.; Kemp, R.; Avelino, F. Building a middle range theory of Transformative Social Innovation: Theoretical pitfalls and methodological responses. Eur. Public Soc. Innov. Rev. 2017, 2, 59–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westall, F. How Can Innovation in Social Enterprise Be Understood, Encouraged and Enabled? A Social Enterprise Think Piece for the Office of the Third Sector; Cabinet Office of the Third Sector: London, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Garrido, A.; Pereira, D. A Economia Social em Movimento: Uma História das Organizações; Tinta da China: Lisbon, Portugal, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Almeida, C.D.; Albuquerque, C.M. Welfare State in Portugal: Delegated powers or disclaims responsibility? Gigapp Estud. Work. Pap. 2020, 147, 141–157. [Google Scholar]

- Barbera, F. L’innovazione sociale: Aspetti concettuali, problematiche metodologiche e implicazioni per l’agenda della ricerca. Polis 2020, 35, 131–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerreiro, J.A.; Pinto, H. Social Innovation, Fourth Sector and the Commodification of the Welfare State: The Portuguese Experience. In Social Innovation and Entrepreneurship in the Fourth Sector: Sustainable Best-Practices from across the World; Sanchez-Hernandez, M., Carvalho, L., Rego, C., Lucas, R., Backx, A., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Segercrantz, B.; Sveiby, K.; Berglnd, K. A discourse analysis of innovation in academia management literature. In Critical Studies of Innovation: Alternative Approaches to the Pro-Innovation Bias; Godin, B., Vinck, D., Eds.; Edward Elgar: Cheltenham, UK, 2017; pp. 276–295. [Google Scholar]

- Sveiby, K. Unattended consequences of innovation. In Critical Studies of Innovation: Alternative Approaches to the Pro-Innovation Bias; Godin, B., Vinck, D., Eds.; Edward Elgar: Cheltenham, UK, 2017; pp. 137–155. [Google Scholar]

- Mulgan, G. The Process of Social Innovation. Innov. Technol. Gov. Glob. 2006, 1, 145–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nogueira, C.; Pinto, H.; Sampaio, F. Social Innovation and Smart Specialisation: Opportunities for Atlantic Regions. Eur. Public Soc. Innov. Rev. 2017, 2, 42–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grisolia, F.; Ferragina, E. Social Innovation on the Rise: Yet Another Buzzword in a Time of Austerity? Salute e Societa 2015, 1, 169–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moulaert, F.; Mehmood, A.; MacCallum, D.; Leubolt, B. Social Innovation as a Trigger for Transformations: The Role of Research; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Lévesque, B. Social Innovation in governance and public management systems: Towards a new paradigm? In The International Handbook on Social Innovation: Collective Action, Social Learning and Transdisciplinary Research; Moulaert, F., MacCallum, D., Mehmood, A., Hamdouch, A., Eds.; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2013; pp. 25–39. [Google Scholar]

- Novy, A.; Hammer, E.; Leubolt, B. Social Innovation and Governance of Scale in Austria. In Social Innovation and Territorial Development; MacCallum, D., Moulaert, F., Hillier, J., Haddock, S.V., Eds.; Ashgate: Aldershot, UK, 2009; pp. 131–147. [Google Scholar]

- Swyngedouw, E. Civil Society, Governmentality and the Contradictions of Governance-Beyond-State: The Janus-Face of Social Innovation; Ashgate: Aldershot, UK, 2009; pp. 63–78. [Google Scholar]

- Hulgård, L.; Ferreira, S. Social Innovation and Public Policy. In Atlas of Social Innovation; Howaldt, J., Kaletka, C., Schröder, A., Zirngiebl, M., Eds.; Oekom Verlag GmbH: Munich, Germany, 2019; pp. 24–29. [Google Scholar]

- Avelino, F. Power in Sustainability Transitions: Analysing power and (dis)empowerment in transformative change towards sustainability. Environ. Policy Gov. 2017, 27, 505–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habermas, J. The New Obscurity: The crisis of the welfare state and the exhaustion of utopian energies. Philos. Soc. Crit. 1986, 11, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avelino, F.; Wittmayer, J.; Pel, B.; Weaver, P.; Dumitru, A.; Haxeltine, A.; Kemp, R.; Jørgensen, M.; Bauler, T.; Ruijsink, S.; et al. Transformative social innovation and (dis)empowerment. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2019, 145, 195–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzucato, M.; Kattel, R.; Ryan-Collins, J. Challenge-Driven Innovation Policy: Towards a New Policy Toolkit. J. Ind. Compet. Trade 2019, 20, 421–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battilana, J.; Lee, M. Advancing Research on Hybrid Organizing. Acad. Manag. Ann. 2014, 8, 397–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zivkovic, S. Systemic innovation labs: A lab for wicked problems. Soc. Enterp. J. 2018, 14, 348–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BEPA. Empowering People, Driving Change: Social Innovation in the European Union; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Report from the Commission on the Mid-Term Evaluation of the European Union Programme for Employment and Social Innovation (EaSI); Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Maduro, M.; Pasi, G.; Misuraca, G. Social Impact Investment in the EU. Financing Strategies and Outcome Oriented Approaches for Social Policy Innovation: Narratives, Experiences, and Recommendations; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Rosas, F. O salazarismo e o homem novo: Ensaio sobre o homem novo e a questão do totalitarismo. Análise Soc. 2001, 35, 1031–1054. [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira, A.R.; Carolo, D.; Pereira, M.T.; Silva, P.A. Fundamentos Constitucionais da Proteção Social. Sociologia Problemas e Práticas 2016, 71–97. Available online: http://journals.openedition.org/spp/2613 (accessed on 19 January 2021).

- Hespanha, P.; Portugal, S. Welfare Cuts and Insecurity under the Rule of Austerity: The Impact of the Crisis on Portuguese Social Services. Oñati Socio-Leg. Ser. 2015, 5, 1110–1132. [Google Scholar]

- Vieira, N.S.; Parente, C.; Barbosa, A. ‘Terceiro setor’, ‘economia social’ e ‘economia solidária’: Laboratório por excelência de inovação social. Sociologia 2017, 100–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meira, D.A. A Lei de Bases da Economia Social Portuguesa: Do Projecto ao Texto Final. Rev. Jurídica 2013, 24, 1–32. [Google Scholar]

- Fern, E. Advanced Focus Group Research; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes, D.; DuMont, K. Using focus groups to facilitate culturally anchored research. In Ecological Research to Promote Social Change: Methodological Advances from Community Psychology; Revenson, T., D’Augelli, A., French, S., Eds.; Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers: New York, NY, USA, 2002; pp. 257–289. [Google Scholar]

- Barbour, R. Doing Focus Groups; SAGE Publications: London, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Haxeltine, A.; Avelino, F.; Wittmayer, J.; Kunze, I.; Longhurst, N.; Dumitru, A.; O’Riordan, T. Conceptualizing the Role of Social Innovation in Sustainability Transformations. In Social Innovation and Sustainable Consumption: Research and Action for Societal Transformation; Backhaus, J., Audley, G., Lorek, S., Vadovics, E., Wittmayer, J., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 12–25. [Google Scholar]

- Martinelli, F. Social Innovation or Social Exclusion? Innovating Social Services in the Context of a Retrenching Welfare State. In Challenge Social Innovation; Franz, H., Hochgerner, J., Howaldt, J., Eds.; Springer: Heidelberg, Germany, 2012; pp. 169–180. [Google Scholar]