Abstract

Although climate finance tools like green bonds have been gaining popularity in academia, the research has been limited to examining the financial viability and performance of this market. We explore a different research avenue related to institutional dynamics that are driving this market at the country level and shaping its adaptive capacity to climate change. Our paper introduces a new conceptual framework by linking institutional isomorphism with adaptive capacity dimensions in the green bond market. Using a mixed methods exploratory approach, we apply our institutional pressure-adaptive capacity framework to India’s green bond market. Our results show that different social actors, ranging from formal institutions like regulators and investors to informal ones like advocacy groups, can play a key role in shaping the legitimacy of this market. By highlighting ‘invisible’ social norms such as awareness about climate finance, changing regulatory priorities and the institutional strength of social actors, we contribute to the literature on this topic. We also introduce the concept of a high priority social actor and conclude that varying degrees of institutional pressure from such actors will ultimately decide the growth and legitimacy of this integral climate finance market at the country level as well as influence its adaptive capacity response to climate change.

1. Introduction

For centuries, institutions in their various forms including markets, governments and even civil society, have played an integral role in how societies have evolved. They have done so through shared expectations, beliefs, values, and even formal rules among social actors about “how the world should and does operate” [1] (p. 1). With climate change being one of the biggest collective action problems in society, it brings up the need to understand how institutions affect the transition towards climate adaptation and mitigation. One such institution that demands further study has been that of climate finance markets, given its growing legitimacy within the global financial market setting.

Climate finance is not only able to transcend global borders, but also creates economic incentives for behaviour change at both the public and private sector level [2]. However, an academic gap exists in not only documenting changing financial norms, but also in whether the threat of climate change and pressure from social actors could be a driving force in guiding institutional transitions. This paper addresses the gap on institutional transition in the financial markets through its analysis of a popular climate finance tool known as the green bond. By examining the institutional pressures on the social actors participating in this market, we further assess the adaptive capacity of the green bond market to respond to climate risks.

In line with the literature, we define social actors as those based in an institutional setting (i.e., capital or financial markets), who can further directly or indirectly influence the institution and its regime change [2]. In the green bond market, social actors can either have a direct role and be primary social actors (i.e., issuers, investors, regulators, rating agencies, and so on), or be secondary and have a more indirect role (i.e., governments, industry associations, academic researchers, and so on)—both of which ultimately have varying degrees of influence on the market. Therefore, depending on their power distribution and legitimacy in the institutional setting, social actors can create economic, behavioural or social incentives [3] and hence ultimately change an institution’s ‘business-as-usual’ or current pathways [4]. The opposite can also be true, where institutional isomorphism (referred to as institutional pressure from here on) can change due to internal or external factors that are felt by social actors, depending on how directly associated they are to the existing institutional regime [5].

Although the literature on both institutional theory and adaptive capacity is still evolving to address the role of institutions in the climate change era, our paper seeks to fill the gap in terms of analyzing new and evolving ethical institutions like the green bond market. So far, the green bond market literature has addressed financial aspects and motivations, such as its positive corporate performance [6], pricing differential [7,8], market liquidity [9,10], comparative financial returns [11,12], investor risk perception [13,14,15], impact and reactions from other types of financial markets like credit [16], treasury, energy [17] and the stock market [18]. However, only a few papers have sought to address the institutional dynamics that play a role in this market from a developing or emerging economy standpoint [10,19], with most focusing on the voluntary governance aspects of this market [20,21]. Our exploratory study contributes to the literature in terms of a country-level analysis of this market, with implications for institutional impact in an emerging economy.

In order to further explain institutional isomorphism or pressure in this market, we use institutional theory due to its ability to explain evolving legitimacy of institutions in relation to the established regime or norms [5]. As supported by this theory, institutional transition and regime change occur only when there is greater agreement among formal and informal social actors [5]. Typically, such transitions are also brought about by certain institutional pressures categorized as coercive, normative and mimetic drivers [5] of change. Our paper uses these aspects of institutional theory to create a new analytical framework around the green bond market and highlight the institutional pressures being felt by integral primary and secondary social actors. Our institutional pressure framework is then supplemented with the literature on adaptive capacity and uses Gupta, Termeer, Klostermann, Meijerink, van de Brink, Jong, Nooteboom and Bergsma’s Adaptive Capacity Wheel (ACW) [22] to understand which criteria and dimensions of institutional strength are most influenced by the institutional pressure being exerted on social actors of this market.

With most management and sustainable finance research having a strong Western focus, a South Asian perspective might be beneficial due to the urgent need for new governance models that could help hasten the low-carbon climate resilient (LCR) transition. We seek to fill this literature gap by applying our institutional pressure and adaptive capacity framework to an important and emerging South Asian economy like India. Since previous academic literature has mainly centered on the financial performance of this market, our focus is on a different aspect that looks to link the financial value-add of green bond markets in South Asia and its existing institutions to address the adaptive capacity to climate change. Doing so allows us to explore the perceptions of involved actors in relation to the institutional norms currently governing this market in the South Asian context [23]. By focusing on South Asia’s biggest green bond market in India, we are able to highlight transferrable lessons for other emerging economies that might face similar growing pains when trying to engage with their own green bond markets. Hence, our research questions focus on first identifying the type of institutional pressure along with the subsequent impact on adaptive capacity dimensions, as well as on understanding the Indian green bond market’s stage of institutionalization and overall adaptive capacity.

By using a mixed methods exploratory approach, we start with the descriptive quantitative data of the Indian green bond market from 2015 to 2017 and link different institutional pressures to it, such as regulation and stakeholder advocacy. We supplement this with detailed interviews of high-level market participants to fill the gap regarding market perception and its institutionalization within the Indian economy. Using our conceptual framework, we analyze our findings to show that although India’s green bond market is evolving, its growth is hampered by factors like the lack of awareness about climate finance, changing regulatory priorities and overall institutional strength of Indian social actors. We also introduce the concept of a high-priority social actor and conclude that varying degrees of institutional pressure from such actors will ultimately decide the future of this market and its adaptive capacity in response to climate change.

Background

The green bond market has not only been successful over the last decade, but it has also been the most ‘public face’ of climate finance. Unlike a traditional bond market, it raises specific debt capital for climate-friendly projects and assets in order to provide investors with financial returns and to support the transition towards a low-carbon economy [24]. Green bonds also provide risk-adjusted financial returns on par with regular or vanilla bonds, which is a main attraction for various types of investors (including niche green and socially responsible investors) as well as other stakeholders (such as governments, regulators, public and private issuers, environmental non-governmental organizations and even rating agencies) to participate in this market [2]. Its popularity is visible in yearly exponential growth, which crossed $200 billion in 2019 alone [24] and is twice the annual amount being committed by developed countries through official development aid (ODA) [25].

Globally, the green bond market is one of the most advanced forms of climate finance that is currently addressing both climate risks and financial opportunities related to addressing climate change [2]. However, with the market still not standardized, the fear of greenwashing persists among various stakeholders [25]. Therefore, in order to dispel these fears, there is a need for greater institutional support and oversight from social actors in the market. Since the support and acceptability for any market is driven by its institutional legitimacy [5,25], the broader focus of this research has been on understanding institutional dynamics or pressures that are driving the growth of this market. Although the green bond market has various social actors, this study will focus on a mix of primary and secondary social actors that hold a high degree of power and legitimacy in the market, namely institutional investors, both public and private issuers, national governments and financial market regulators (including securities regulator or central banks)—and evaluate their role in contributing to the market’s overall adaptive capacity or its ability to adapt to impacts of climate change.

This research has a three-fold contribution in the field of green bonds research, institutional theory, as well as organizational models surrounding South Asian economies. Firstly, it contributes to the academic literature on the green bond market by providing a conceptual framework for the drivers of the market, especially in terms of the various institutional pressures faced by its social actors. Secondly, it connects literature on adaptive capacity of institutions with management literature by examining the adaptive capacity of the green bond market and its social actors to climate change. Thirdly, it uses the case study of India’s green bond market to test the conceptual framework as well as provides some guidelines to apply this framework in the context of other South Asian countries that are trying to nurture their own green bond market growth.

2. Literature Review and Conceptual Framework

The adaptive capacity of institutions can be defined as the “inherent characteristics of institutions that empower social actors to respond to short and long-term [climate] impacts…and encourage these actors to change these institutions to cope with climate change” [22] (p. 461). By missing out on the implementation of climate-sensitive measures, the adaptive capacity of institutions gets shaped as a reaction to the socioecological changes occurring at that point [3]. In literature, “institutions” are usually seen to be synonymous with “organizations” [22] (p. 460). Although organizations are formalized patterns of rules and decision-making, institutions represent much more than that, given their underlying ideological values and norms [22]. Based on this, we define institutions as a system of rules or decision-making space, that can further influence organizations and vice-versa. In the context of the green bond market, institutions are seen as the organizations represented by social actors (like investors, issuers, regulators, governments and service agencies) that create the primary decision-making space for formal and informal rules of this market, but with the ultimate purpose of influencing the flow of traditional capital. Therefore, we regard the green bond market as not just an institution, but an underlying bridge for institutional regime change that can also provide a space for traditional financial market actors to interact and create new norms or rules about climate finance as an overarching institution.

As mentioned by Gupta et al. (2010), institutions can be seen as “inherently conservative due to their ability to come to collective agreement based on long debates over time” [22] (p. 460) and because of their tendency to be path-dependent [26] as well as reinforce current institutional logics. This makes institutions slow in reacting to change and leading to slower institutional transitions, which is ultimately a barrier for addressing evolving climate impacts and adaptation needs [22]. To understand the various drivers of institutional transition and its adaptive capacity, this section first outlines the various types of institutional isomorphisms or pressure. Examining these pressures can be an important foundation to map institutional regime change in the context of climate uncertainties, based on their ability to predict and explain the motivations behind institutional transitions.

If we look at the green bond market, a driver of its inclusion in the mainstream financial market discourse can be attributed to the institutional pressure experienced by various social actors. Some of the primary social actors that have a direct role in transacting in this market can include financial market regulators (like securities market regulator or central banks), various types of issuers and investors as well as market service providers (e.g., third-party auditors or second opinion providers). Secondary social actors can be seen as those having a more indirect role in the functioning of the market—such as national governments that contribute to climate policy and economic transition, industry associations that recommend best practices and others that are market advocates but do not have a primary role. This paper examines how some of these actors are influenced by the three types of institutional pressures within the green bond market and further impact its overall adaptive capacity.

Based on recent literature on the green bond market, the following sub-section outlines how institutional pressures can influence social actors of the market. The next sub-section introduces the concept of the adaptive capacity wheel [22] and explains which criteria are most applicable to the green bond market. Finally, it sets out a conceptual framework showing how to apply the institutional pressure-adaptive capacity response analysis in the context of a specific green bond market by using the case study of India.

2.1. Types of Institutional Isomorphisms

Institutional isomorphism or the process to gain homogeneity in the face of future uncertainty like environmental change, can be driven by both formal and informal norms and dynamics that govern institutional transitions [5]. According to institutional theory, institutional transitions can occur due to coercive pressure from formal or informal rules exerted by one institution on another—in our case, this can be categorized as formal regulations or informal communication by a primary social actor in the green bond market [20,27]. The most formal and direct coercive pressure in this market can be through formal and targeted regulations like green bond disclosure norms or green taxonomy frameworks, which are usually provided by governments or regulators based on the country or region [20,28]. Indirect but formal coercive pressure can also be felt due to climate-related government fiscal policies like the green credit guidelines in China [28] or financial incentives for greater renewable energy investments [29] at the regional or local level [19]—which may or may not have a direct impact on the market, but end up creating incentives for greater green investment flows [2,16]. On the other hand, direct but informal coercive pressure might entail institutional investors demanding climate-related disclosures for green bond investments by using shareholder activism or proxy voting [30]—which influences the underlying rules and norms about climate finance at the institutional level [31].

If an institution changes due to socially accepted common norms and practices, then the transition is driven by normative pressure [32,33]. However, social practices or norms are not only useful in shaping institutions, but they can also be shaped by them in return [22]. This is visible in the green bond market, with normative pressure coming from secondary social actors such as international organizations like relevant United Nations (UN) agencies that have a specific financial market mandate. For instance, UN Environment Programme’s Financial Inquiry (UNEP FI) or UN Principles of Responsible Investment (UNPRI) are both regarded as relevant organizations by market players in the global climate finance markets [10,34]. Furthermore, normative pressure can also come from globally accepted industry associations and their guidelines, like the International Capital Market’s Association (ICMA)’s Green Bond Principles (GBP) or investor-focused associations like Climate Bonds Initiative (CBI). Not only do these secondary actors create the social pressure necessary in helping legitimize green bonds within their traditional spheres of influence, but they in turn get influenced by how this market evolves based on their institutional mandates to address climate-related financial risks and opportunities [10,13,16].

At some point, various social actors can even work together to influence the creation of new rules or social practices in this market [14]. For example, ICMA’s GBP process involved collaboration from various market players or having several countries come together to create a region-specific taxonomy like that by EU’s Technical Expert Group on Sustainable Finance or have sector-specific taxonomies like those seen in the Climate Bonds Taxonomy 2020. The innovative nature as well as the threat of greenwashing in this market have led to new market rules around authentication of the use-of-proceeds, with issuers using green bond certifications or verification schemes and audits being conducted through third-party firms or CBI-approved green bond verifiers [10]. Similarly, social actors are also working together on regional and international efforts around market standardization, as seen in the Association for Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN)’s Green Bond Standard or in International Organization for Standardization (ISO)’s 14030 Standard on green debt instruments [19,35].

In other cases, an institution can also change proactively in a way that follows imitation of other institutions in order to cope with uncertainty [5]; this is known as mimetic pressure. In the green bond market, imitation can mean undertaking innovative activities or initiatives by primary social actors (who are most likely also newcomers to the market) to reduce future uncertainties. For example, primary social actors like regulators can follow industry-established guidelines like the GBP or CBI taxonomy to create their country-tailored regulations or definitions for green bonds [20]. Other indicators of mimetic pressure can be when secondary social actors such as traditional government ministries like Finance or Environment start getting involved in novel areas like green bonds or sustainable finance [20,36].

However, social actors that face the highest carbon risks or are in need of access to capital, are most likely to face this type of pressure. In terms of issuers, these can include emerging and developing countries or oil-dependent economies, provinces or states as well as municipalities that are based in high-risk regions (like flood zones or coastal regions) and have carbon-intensive business models that are resource-based like those of fossil fuel companies. Such social actors might start looking to issue green bonds or even transition-linked bonds [37] in order to cope with future climate risks [6,9,38,39,40]. In terms of investors that face the most mimetic pressure, it can include those that have an asset–liability mismatch, such as those seen in pension funds having long-term fiduciary duties, as well as those that have high risk of stranded assets, especially due to exposure to carbon-intensive portfolios [41]. In order to cope with this type of institutional pressure, institutional investors might start conducting climate stress testing of their portfolios (as recommended by the Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosure (TCFD) report) or applying Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) criteria to screen or diversify investments [27].

The following table (see Table 1) summarizes the relevant literature on institutional pressure as well as on the green bond market, to create a conceptual framework of how social actors in this market respond to institutional pressures. The different types of institutional pressure may work in various settings or in tandem, for instance, coercive pressure like climate regulations or policy (or a lack of) can have a compounding impact on mimetic pressures by motivating the green bonds market to reduce climate uncertainty by issuing more green bonds or following international voluntary standards in the absence of climate policy. Hence, this framework should be seen as that which applies contextually based on the green bond market in question.

Table 1.

Key literature with examples of application to the green bond market and its social actors.

This paper looks to “explain core characteristics and behaviors of [important and relevant social] actors in the emergence and diffusion of [green bond market] practice by pointing to the relevance of higher-order principles like rules, norms, taken-for-granted assumptions or cultural belief systems” [3] (p. 774). Financial aspects that have been discussed in the literature are not addressed in this study to be able to focus on institutional aspects of the green bond market. In order to explain the growing legitimacy of a green bond market within the current global financial regime, we provide a unique insight into the relationship between the social actor, institutional pressure and adaptive capacity of this market.

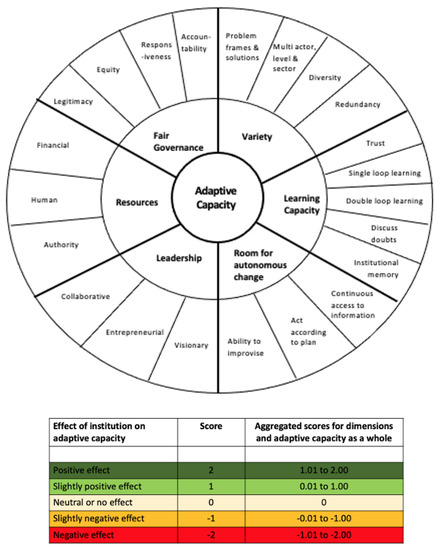

2.2. Assessment Tool: Adaptive Capacity Wheel

In order to assess the green bond market perception of the institutional regime change in the traditional financial markets, our paper uses an adaptation assessment tool known as the Adaptive Capacity Wheel (ACW) by Gupta et al., (2010) (see Figure 1). As defined in the literature, the following six dimensions are the main indicators of adaptive capacity: having a variety in perspectives, improving learning capacity through trust and institutional memory, making room for autonomous change through capacity building, encouraging visionary and collaborative leadership, implementing adaptation measures through use of resources (legitimate, financial and human) and encouraging overall fair governance [22]. These dimensions further consist of twenty-two criteria that can be connected to institutional literature on governance, international relations, organizational behaviour and earth-systems governance [22].

Figure 1.

Original Adaptive Capacity Wheel from Gupta et al., 2010 (p. 464).

Over the past few years, the ACW has been applied to assess the resilience of different institutional settings, including water management governance in the Netherlands [42], EU and China [43] as well as examining urban planning institutions in the Netherlands [44]. However, it has not yet been applied to the context of a financial market, let alone a climate finance market like the green bond market. Our paper is the first to identify the relevant ACW dimensions for the green bond market, by focusing on the criteria that would reinforce growth and legitimacy at the global level. It then moves on to assess the particular climate resiliency and adaptive capacity of a country-level market.

However, as mentioned by Gupta et al. [22] and presented in Figure 1 a few points need to be kept in mind when applying ACW—certain dimensions and criteria can be reinforcing as well as create tensions (e.g., between strong leadership and high variety), some criteria can make others less relevant (e.g., sufficient entrepreneurial may not require visionary leadership), dimensions and criteria are not independent of each other (e.g., resources and fair governance can have broad impacts) or of their contexts (e.g., what is applicable for green bonds in one country context, might not work in another country due to varying institutional dynamics) and lastly, even if financial markets showcase adaptive capacity, it does not mean that it will go into a greener direction (p. 465).

2.3. Conceptual Framework

In this paper, we use an adapted conceptual framework to reflect the relevant institutional pressures and their adaptive responses within ACW. Firstly, the institutional space of interest is the green bond market and the isomorphic pressures being experienced and exerted by its social actors. Although there are 22 criteria outlined, not all can be applicable or complementary to the green bond market context, because the market involves a variety of social actors being influenced by institutional pressures (as seen in Table 1).

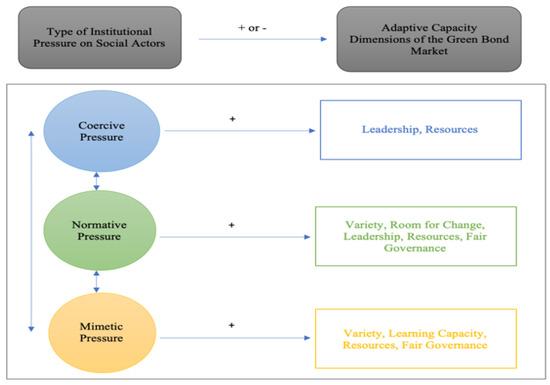

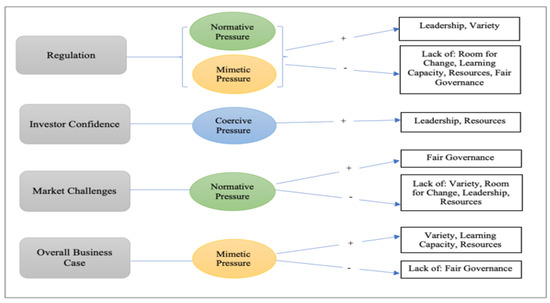

In order to identify the most relevant dimensions and their impact on the green bond market, we scored the adaptive capacity criteria using the scale provided and then cumulatively showed the positive or negative impact on each dimension (see Figure 2). Although we acknowledge that adaptive dimensions and criteria could have both positive and negative impacts based on the type of institutional pressure, for the purposes of our conceptual framework we focused on the ones that had the most positive impact on this market. The question we asked to ascertain the relevant criteria was: Based on the type of institutional pressure (e.g., coercive, normative or mimetic) on the social actor, which adaptive capacity criteria is most likely to have a positive response in the green bond market? This allowed us to identify the overall dimensions that were ultimately the most positively influenced by the three types of institutional pressures. We then created the following conceptual framework based on the type of institutional pressure and its preferred adaptive capacity dimension:

Figure 2.

Conceptual framework: Connecting the three type of institutional pressure and their relevant adaptive capacity dimension for the green bond market.

Based on the two chosen literatures, i.e., institutional theory and adaptive capacity response, our hypothesis was that different types of institutional pressure on social actors reinforce certain but not all adaptive capacity dimensions of the green bond market positively. For instance, coercive pressure in this market can be based on direct formal, direct informal and indirect formal rules set out by primary social actors like investors, regulators or governments (see Table 1). The result of this is that coercive pressure will encourage primary social actors to increase internal or external communication about climate change and its impact on their role or business. In this case, having dimensions like strong visionary leadership through public–private collaborations and partnerships might be seen as being a proactive solution on integrating climate risks. Furthermore, by encouraging efficient use of resources based on greater redirection of authoritative, human and financial power, it would also help positively reinforce the green bond market growth. Hence, leadership and resources are seen to be important dimensions for coercive pressure in this market.

Normative pressure in this market (see Table 1) are based on social norms exerted by secondary social actors, such as industry associations like ICMA or CBI as well as international agencies like the UNEP FI or UNPRI among others. In this case, dimensions that would be reinforced by this pressure included having a greater variety, multiple problem frames or stakeholder views, diversity in solutions being enforced, and a redundancy from having multiple secondary social actors involved. This allowed greater room for autonomous change, based on the use of continuous access to new or evolving information like an international green taxonomy, green bond standard or market best practice like verifications, which ultimately helps address the market’s capacity to improvise in a time of change or crisis. Due to such enterprising social norms being established by secondary social actors, it means certain primary social actors exhibit leadership aspects by engaging in innovative initiatives and showing greater visionary, entrepreneurial and collaborative efforts within the market. This aspect is visible in greater collaborations among both types of social actors to create new standards, guidelines or best practices for the market.

Furthermore, having resources due to the involvement of industry associations like the UNPRI or at the government level also meant that trillions of dollars in financial power were being represented, which further contributes to market legitimacy and governance. In order for normative pressure to impact the green bond market, our framework indicates that fair governance aspects like greater social and collective legitimacy, responsiveness to market challenges and accountability continue to play an important role in this market. Hence, dimensions like variety, room for change, leadership, resources and fair governance are seen to be important for normative pressure.

Mimetic pressure in this market allowed non-traditional primary and secondary social actors (see Table 1) to address climate uncertainty and imitate other successful initiatives and activities. In this context, dimensions like learning capacity, variety, resources and fair governance are seen to be positively reinforcing for this market. For example, in order to better adapt to climate change impacts, an investor might experience mimetic pressure due to uncertainty of climate impacts and use their learning capacity to take up new best practices like certifications or third-party audits of their green bonds. Doing so could also involve improving single and double loop learning in terms of better organizational routines (or establish an internal process for subsequent green bond issuances or evaluations) and questioning traditional investment criteria within decision-making processes, respectively. Learning capacity also means that institutional memory of a non-traditional social actor, including the Ministry of Finance or Environment and high-risk social actors (like fossil fuel companies or investors having stranded assets), can be improved due to the imitation of initiatives undertaken by other successful social actors in the market.

In terms of the variety of solutions, problem frames and diversity criteria, were seen as important for mimetic pressure because they provided the flexibility for social actors to choose the most relevant imitation strategies. On the other hand, having a greater number of financial, human and authoritative resources, such as those found in multinational issuers, institutional investors or developed country governments, might enable any newcomers of this market to implement their chosen solutions or strategies more effectively. Lastly, fair governance was seen as being beneficial in order to encourage legitimacy of this market due to greater responsiveness from different types of social actors in addressing climate impacts. This also allowed greater accountability in terms of measuring or tracking greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions as well as increasing participation from non-traditional social actors like institutional investors or fossil fuel issuers. Hence, dimensions like variety, learning capacity, resources and fair governance are seen as being important for mimetic pressure in the market.

Similar to the functioning of the institutional pressure, dimension and criteria of the adaptive capacity wheel are seen to be reinforcing to each other or working in tandem, as well as changing based on the context, i.e., evolving aspects of climate impacts or different political systems of a country. Therefore, it is important to use our framework in a manner that keeps in mind these specific caveats and apply it using a case study method. Our paper showcases how to do this in the Indian green bond market, and further delves into how institutional isomorphic pressure can create or hamper institutional transition. An important aspect to keep in mind is that in most cases, as a response to one or more types of institutional pressures, social actors of this market are likely to perceive an action in a reactionary sense. In order to examine the reactionary outcomes, this paper uses our institutional pressure-adaptive capacity response framework to provide answers to the degree of climate resilience that Indian social actors and their institutions will face through this market.

Based on our literature analysis and conceptual framework building, the objective of this paper is to apply institutional isomorphism in the green bond market of India and understand the relevant adaptive capacity dimensions that are either contributing or hampering its market potential. Therefore, our study asks the following research questions:

- How do various institutional pressures influence the adaptive capacity of the green bond market?

- What are the different types of institutional pressures present in the Indian green bond market and what is its overall adaptive capacity?

3. Materials and Methods

This section further breaks down our data collection aspects as well as our data analysis process.

3.1. Data Collection

By analyzing the green bond market using an exploratory lens and mixed methods approach, we used descriptive market statistics to examine India’s green bond market growth. The gaps in the quantitative data further motivated the in-depth qualitative inquiry using stakeholder interviews. To answer our research questions, we used data from ten key interviews conducted during May–June 2018, with various high-level stakeholders in the Indian and international green bond market. Our pool of interviews included two types of Indian financial regulators, one Indian and one international financial industry association, two Indian green bond issuers, one international underwriter and one multilateral financial institution operating in India—all of whom had tangible experience within the Indian green bond market (See Table A1 in Appendix A). The interviews were semi-structured and conducted with individuals at the executive or senior policy levels within their organizations. Based on their high-level positions and subsequent ability to influence decision-making processes within their organization, our qualitative findings were seen as being robust and validated by the annual India green bond market reports issued by Climate Bonds Initiative.

Participant types of regulators, issuers, investors, bond underwriters and industry associations were chosen based on their direct interactions with the Indian green bond market as a primary stakeholder. Participants were recruited either through mutual industry connections of the authors or from their previous interactions at events like UNEP-FI India report launch and stakeholder roundtable meetings held by CBI in India. They were invited to participate in this study by an email which outlined the study’s research objective, ethics clearances and provided a broad set of questions. All participants gave their informed consent for participation in this research. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and the protocol was approved by University of Waterloo Research Ethics Committee (ORE#23082). Each interview lasted between 50–120 min and was recorded and fully transcribed, providing a rich source of contextual qualitative data and amounting to over 120 pages of transcript.

In order to set the stage for the qualitative results, detailed green bond issuance data such as use-of-proceed information, issuer name, issuance amount, date of issuance and maturity and currency of issuance, was obtained by the authors from CBI using an academic request form in April 2018. The market period analyzed is financial years of 2015 to 2017, due to the availability of complete data at the time this study was undertaken.

3.2. Data Analysis

In order to set the stage, our descriptive green bonds data for the Indian market were also related to various macro-level events affecting India’s market at that time. The macro-level events chosen for this study were based on the hypothesis that overall financial stability (of the country) and institutional legitimacy (of certain social actors like public regulators) were important factors in how social actors, such as investors and issuers, respond to climate finance. Hence, the event types chosen for this study included date of relevant regulation announcements, demonetization of Indian currency and CBI advocacy events being held for this market.

For India, a macro-level event like the demonization of certain currency in November 2016 influenced the overall stability of all financial markets negatively and hence directly affected issuances of green bonds. In terms of regulation announcements, a rise in issuances was observed after the issuance of a green bond disclosure guideline in 2017 by the Securities and Exchange Board of India (SEBI), the securities market regulator. This complemented a set of previous indirect regulations issued by the central bank, Reserve Bank of India (RBI), that allowed eligible Indian corporates to issue rupee-denominated bonds in overseas markets. Another relevant aspect that was examined were the investor advocacy events, including Climate Bonds Initiative (CBI) events held in India (data obtained from the Archives section of CBI’s website) as well as the UNEP-FI Inquiry: Delivering a Sustainable Finance System in India report launch (see Table 1 for the role of secondary social actor like UN agencies in normative pressure for this market).

The data analysis for the qualitative aspect of our study consisted of three stages; starting with detailed reading of textual analysis, including primary data from interview transcripts and peer-reviewed journal papers as well as secondary data from regulation documents and policy reports on India’s financial system. In the second stage, the primary interview data were then openly coded into various relevant ‘nodal points’ around which narratives, discourse and key words were identified in the text [45]. This resulted in 25 ‘nodal points’, each of which illustrated the relationship between the green bond market and its social actor (or primary stakeholder) interaction. The open coded nodal data were then re-analyzed around four key axial coding themes [45] and categorized to illustrate the relationship between institutional isomorphism and the green bond market—for instance, regulation, investor confidence, market challenges and business case of the green bond market. By using our conceptual framework, we further connected the 25 open codes (and in extension their four axial codes) with the three types of institutional pressures (namely coercive, normative and mimetic).

In the third and last stage, the data from the results section were then categorized in terms of their relevant adaptive capacity dimensions in the Indian green bond market. By using the qualitative findings in conjunction with the Adaptive Capacity Wheel, institutional pressures driving the green bond market in India are analyzed in the discussion section. It also applied the relevant adaptive capacity dimensions (based on those identified in our conceptual framework, see Figure 2) to the qualitative findings in order to measure its overall adaptive capacity. However, in reality, within an institutional system, adaptation is unlikely to follow a direct path towards these outcomes [46]. Hence, it was important to keep in mind the contextual background of the Indian green bond market and then apply the relevant aspects of the conceptual framework. Throughout this study, standard methods of qualitative social research were used to ensure theoretical fit of the data, with a focus on ensuring construct validity as well as external validity of the results. Furthermore, the use of multiple sources of evidence, such as primary (such as interviews with key stakeholders), secondary data sources (such as policy reports and CBI database) as well as relevant peer-reviewed literature was able to provide reliability in terms of triangulation of our findings.

4. Results

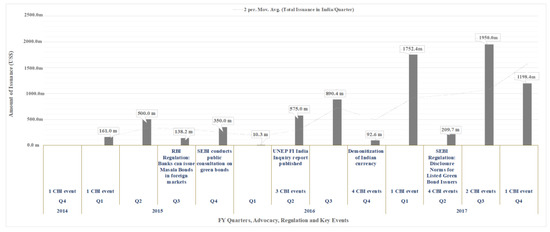

India’s green bond market was initiated in 2015 with the issuance of a green bond from a private sector bank. As the market grew in India, it became the 7th highest country issuer in 2016, the 8th highest issuer in 2017 and then fell to the 12th position in 2018 [47]. Even though its position fell globally in 2018, the total domestic issuances kept increasing quarterly and were only negatively impacted due to macroeconomic events like demonetization of certain Indian currency (see Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Quarterly green bond issuances mapped with regulation announcements, macroeconomic events and advocacy events in the Indian green bond market.

Throughout the chosen time period, India’s economy grew at a rate upwards of 7 percent annually [48]—which signaled the investment opportunity for various international and domestic investors. A unique feature of the green bond market in India was the number of certified green bonds from issuers, having the highest global certifications at the end of 2018, which according to CBI was able to attract deeper pools of capital like those held by global institutional investors [49].

4.1. Descriptive Statistics

In terms of the total issuances per year, in 2015 the market stood at approximately US$1.149 billion, US$1.568 billion in 2016 and US$5.110 billion in 2017. The cumulative total issuances for the Indian green bond market from 2015 to 2017 stood at US$7.827 billion. Quarterly issuances seem to pick up after advocacy events (held by investor associations like CBI) as well as policy support (indirect guidelines from RBI and direct disclosure norms from SEBI), and fall after macroeconomic shocks such as the demonization of certain Indian currency (see Figure 3).

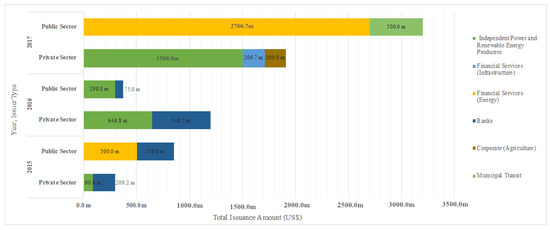

The issuers in the Indian market consisted of both public and private issuers, with six sub-categories of issuers based on their industry type. In the initial stages of this market (2015–2016) private issuers led the market growth, whereas public issuers overtook the market growth in 2017 (see Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Type of issuer and annual issuance amounts based on issuer sub-category.

One of the highest amounts issued during this period was by a public issuer called Indian Renewable Energy Development Authority Ltd. (IREDA) based in New Delhi, which issued a Green Masala Bond on the London Stock Exchange [50], worth $1.5 billion, and also had the first green-certified bonds from a public issuer. In 2017, public issuances rose almost eight-fold ($373 million in 2016, as compared to $3 billion in 2017) as compared to private issuances ($1 billion in 2016 and $2 billion in 2017)—which indicated the transition to a publicly driven green bond market in India.

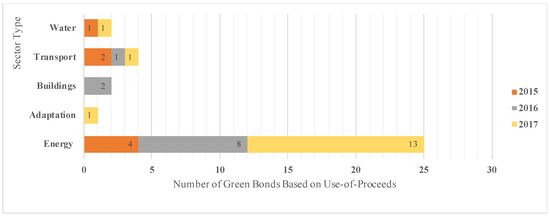

In terms of the use-of-proceeds for Indian green bonds, there were five different sectors being targeted in India—energy, water, transport, building and adaptation. The most important sector was energy (25 out of 28 bonds mentioning it in their use of proceeds) (see Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Popular sectors for Indian green bonds for 2015–2017, based on their use-of-proceeds.

4.2. Qualitative Interviews Results

The results of the qualitative interviews with 10 market participants (see Table A1) are displayed in a table form to show the axial and open coding, as well as the type of institutional pressures affecting this coding (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Axial and coding of interview quotes in relation to institutional pressure types.

The regulation aspects of the Indian green bond market are consistent with our conceptual framework for this market. For instance, regulatory capabilities and regulation creation itself was impacted by the variety of stakeholders involved, for example, SEBI held public consultations before releasing the disclosures norms and significant market growth was only achieved in 2016 after participation from public issuers. However, dimensions like autonomous room for change or the need to build capacity capabilities among social actors and resources, in terms of the greater financial and human resources needed, both had a negative impact. This was due to certain social actors now having to meet additional verification requirements, based on SEBI’s disclosure norms requiring bi-annual reporting instead of the previous market best practice of annual reporting, thereby making it more onerous for Indian issuers to label a bond as a green bond.

Regulation in India was also driven by leadership at the market level rather than at the institutional level, mainly due to the market starting off in 2015 with private sector issuances and regulation only coming after “investors demanding a regulatory stamp on the market” (P5). Given this stakeholder push for regulatory oversight, certain dimensions like having a slow learning capacity among the market participants or the time lag of market regulation being picked up, as well as overall fair governance challenges, as seen with NPA issues in the Indian banking sector, negatively impacted the effectiveness of any regulation in this market.

In terms of the investor confidence, it was clear that the market in India was affected by coercive pressures from investors and responded by showing adaptive capacity dimensions like leadership aspects among certain regulators, for instance, SEBI issued green bond market regulations, whereas RBI did not. It also tapped into the resources aspect among green bond issuers, by showing that certain issuers who were able to meet investor mandates of avoiding controversial investments (e.g., clean coal) as well as those utilizing their financial and human resources for greater reporting and getting more CBI certifications, were further able to improve investor confidence in their green bond.

In terms of the market challenges, normative pressures among market actors due to risk of greenwashing, verification needs, time lag in the market regulation and lack of other financial incentives were indicative of adaptive capacity dimensions of this market. For instance, the lack of variety in financial incentives, seen in the lack of tax incentives or high transaction costs for issuers, not only impacted the market ecosystem, but also reduced the potential for market participation from other traditional or non-green issuers. Furthermore, the limited capacity building capabilities at all levels—such as data reporting and collection gaps among issuers and regulators, respectively (P2; P3), as well as the lack of climate awareness among the Indian investors (P4)—negatively affected adaptive dimensions like room for autonomous change as well as resources. In terms of fair governance, certain issuers (based on their resources) were able to address key market challenges, like the risk of greenwashing, through greater verification and CBI certifications, which also positively impacted the overall Indian green bond market. However, if this was to be extended to other bond issuers that had lower resource capabilities, it would be harder to oversee fair governance aspects, especially due to the lack of market ecosystem that might help reduce issuer transaction costs or make reporting requirements easier.

The overall business case of the market was driven mainly due to mimetic pressures like reputational benefits, incentives to overcome market challenges and a future pricing benefit for issuers. Based on the uncertainty of mimetic pressure, the green bond market provided primary stakeholders with reputational benefits, the direction to overcome market governance challenges (through better use-of-proceed reporting and third-party verifications) as well as the potential for future pricing benefit of green products. In terms of the adaptive capacity dimensions of the business case as a response to mimetic pressure, having greater variety among investors, as mentioned by “additional SRI [socially responsible investment] investors joining the books” (P10), resources or the ability to have a high number of CBI certifications among Indian issuers in 2018, and learning capacity, seen as the ability to establish trust using third-party verifications or improving institutional memory due to re-issuances by issuers (which could potentially also lead to future pricing benefits) [11] all seem to have a positive effect. On the other hand, uncertain fair governance dimensions like time lag in regulation or even lack of consistent regulatory participation (e.g., due to SEBI’s disclosure norms only impacting publicly listed issuers and RBI having no formal participation in the market) indicated an uncertain negative effect, as it increased the risk of future non-compliance based on the parallel drawn with the ongoing NPA governance challenges within the Indian financial sector.

5. Discussion

The main results suggest that not only were Indian green bond issuances linearly increasing over the years, but they were predominantly driven by normative and mimetic pressure. For instance, we found that market regulation in India itself was predominantly driven by normative and mimetic pressure from social actors like investors. Furthermore, institutional response of the market regulators was shaped by aspects like following international best practices like the GBP, using green taxonomy frameworks as set out by the CBI, comparing what other regulators were doing (in China and elsewhere) and using a reactive approach in policy making due to evolving regulatory priorities (created by macroeconomic issues like demonetization, NPAs and other governance challenges).

In the case of India, we found that the overall institutionalization of the green bond market is still at the growing stages of social legitimacy, which is also known as the objectification stage in institutional transitions. At the objectification stage, the green bond market has some degree of social consensus among organizational decision-makers to increase adoption on the basis of collective consensus that climate targets and financing gaps can be met by growth of this market [5]. However, this type of institutionalization of the green bond market is also applicable to developed markets like the United States or Canada, as well as other Asian economies like Indonesia or South Korea. The reason being that most country level green bond markets are still evolving and trying to ascertain the official role of primary social actors, like regulators or investors, is still in its nascent stages of institutionalization. The only country that has been able to expedite this market’s institutionalization has been that of China, given its coercive institutional pressure approach in mainstreaming this market among domestic social actors [10].

However, due to the unique country-level dynamics of top-down market growth, green bond lessons from China are less applicable to other South Asian countries based on their varying political environments. On the other hand, using the case study of India, our paper highlights the similarity of diverse institutional contexts that could help other South Asian economies in growing their green bond markets. The findings for India are in line with institutional governance literature on how most public institutions in South Asian countries, and especially their regulators, usually operate. As opposed to the regulators in most developed and Western markets, there is a greater level of public embeddedness for those based in South Asian countries, especially when addressing concerns brought up by broader civil society actors as well as in terms of reacting to industry challenges [23]. Our findings suggest that given the socially connected foundations of several Indian institutions, social actors like regulators, investors, market advocates and issuers, will continue to influence how the green bond market grows in India. The following sections further highlights specific lessons that India’s green bond market can provide for South Asian countries.

5.1. Lessons from Institutional Isomorphism of India’s Green Bond Market

Our findings suggest that institutional pressure can have both positive and negative effects in the Indian green bond market, as opposed to only having a positive effect based on certain adaptive capacity dimensions (see Figure 2). For instance, our conceptual framework suggests that when coercive pressure is applied to social actors, a green bond market having greater leadership aspects and access to resources will be beneficial for its adaptive capacity. In the case of India’s market, the reaction between coercive pressure and these two adaptive capacity dimensions was true.

However, in terms of the other two institutional pressures—normative and mimetic—having certain dimensions present (or the lack thereof) led to both positive and negative effects. For example, in terms of the overall business case for the market, social actors were driven due to mimetic pressures, but the scope of this market was ultimately restricted due to a lack of fair governance and participation from other regulators or even other issuers in the Indian financial sector. However, as highlighted in our conceptual framework (see Figure 2), mimetic pressure would have also led to better fair governance in this market. This led us to conclude that the overall institutional adaptive capacity of the Indian green bond market currently stood as being limited, especially since social actors were influenced by normative and mimetic pressures, and exhibited either positive or negative adaptive capacity effects based on the axial theme being considered (see Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Key themes in relation to the type of institutional pressure faced by social actors and their subsequent impact on adaptive capacity dimensions for the Indian green bond market.

Given that normative and mimetic pressures were driving social actors of this market, as well as based on our descriptive statistics, we found that India’s green bond market grew only when there was a harmonization of social actor needs with the national priorities of the country. Almost 89% of Indian green bonds mentioned the energy sector in their use-of-proceeds (see Figure 5), and this highlighted a synchronization of international and national priorities for investing in renewable energy. Doing so not only led to financial diversification benefits and meeting investor mandates for international investors, but also filled a financing gap for national priority sectors in India.

India’s central bank regulator, RBI, usually sets the priority sector limit (PSL) to encourage lenders to finance nationally important socio-economic sectors. PSL was introduced to make it easier for sectors and segments of the Indian economy that find it hard to get access to credit. These include agriculture, small to medium-scale enterprises (MSMEs), social infrastructures, affordable housing, education, renewable energy and others that fall under the weaker sections of society (such as small-scale industries and minorities) [51]. According to these PSL limits, banks can lend up to only INR 150 million (approximately US$2.2 million) to borrowers financing renewable energy projects [51]. With the energy sector growing due to increasing demand, this PSL target becomes a handicap for banks as well as borrowers trying to finance bigger renewable energy projects. Therefore, renewable energy sector growth faces significant financial constraints like high borrowing costs in India, where interest rates are also high (7.21 percent) as compared to European (0.93 percent), US (1.84 percent) or Canadian markets (1.25 percent), and this makes debt an unattractive venture [52]. This is further exacerbated due to short-term lending and asset–liability mismatch [53] as well as the near absence of mature bond markets in India. These factors raise costs of new and unestablished sectors like renewable energy by almost 24–32 percent, as compared to the rates offered by North American or European institutions [52]. Internal financial sector investment limits of scheduled commercial banks (SCB) in India also exist to reduce risk exposure to any one market, sector or technology [52] (p. 6). These constraints highlight the need to introduce new financing instruments like green bonds which are able to leverage a large and diverse investor base, such as institutional investors [51] that are interested in various types of green investments [54].

However, as India is an emerging market, such investments come with certain market risks that international investors face, including greenwashing or a lack of compliance. Hence, creating mimetic pressure on the regulators as well, especially with SEBI being an investor-focused regulator. Based on this risk and pressure, other social actors of the Indian green bond market ended up facing coercive pressures as well; as seen with the release of SEBI’s disclosure norms, where investor push for greater oversight led to formal and direct regulation that impact issuers. This approach is seen to be in line with literature on Indian regulators—who not only play a key role in preventing “greenwashing” to keep market integrity but are also working in reaction to nationally-relevant priorities and influenced by the needs of the social actors involved [23]. In terms of the role of the regulator in the Indian market, it seems that “regulation comes after the market is established and in a supportive capacity” (P3)—which is also the case for regulators in other developing economies in South Asia, especially when looking to attract and ensure oversight on foreign direct investment (FDI) through innovative climate finance markets like the green bond.

Given the high number of investment risks in an emerging market like India, having some regulation in the market is not a surprise, and has further encouraged a rise in issuances from public sector issuers (like IREDA) as well. This also signals that it is ultimately the role of the public sector that decides the fate of a new market like the green bond, and especially for an emerging economy like India. An example of this is seen with private Indian issuers of climate-aligned bonds in the energy sector that benefitted in terms of greater investment due to the guarantees provided by India Infrastructure Finance Company Limited [53] (p. 103). This shows that credit support from public institutions is key in increasing the attractiveness of small and medium-size issuers for risk-averse international investors [53]. Hence, it is important to keep in mind that emerging and developing economies should pay further attention to not only the regulator’s role in this market, but also the type of issuers that are present and provide a helping hand to newer market participants.

5.2. Theoretical Contribution

In relating our findings back to our conceptual framework, institutions that achieve a high degree of social acceptance and legitimacy as well as having scale in terms of their reach or impact, can be considered as strong institutions [32]. Given that climate impacts are also going to test the adaptive capacity of strong institutions, it is necessary that institutional transition occur in a pro-active yet swift manner, but through a process that has wide social acceptance and legitimacy. Based on our findings, it is due to coercive pressure from social actors such as regulators or investors, that has ultimately pushed for institutional transitions within the Indian green bond market. However, in order for this transition to have social legitimacy, it is important that this push be driven by important social actors based on a combination of normative and mimetic pressures being felt through the market. Therefore, our paper puts forth the concept of a high priority social actor or an important social actor that holds a high degree of legitimacy due to having greater financial and social power. A high priority social actor in the overall green bond market can be seen as the main regulator, institutional investor or a large-scale issuer—all of whom not only have greater resources (financial, human and authoritative) at hand, but are also able to influence decision-making across various other institutional settings, including those like regulation or investment priorities. In the case of India’s green bond market, high priority social actors were the international institutional investors, mainstream financial market regulators like SEBI or RBI, as well as large-scale public issuers like IREDA—based on their ability to contribute to greater market legitimacy, create the rules of the market and help minimize the growing pains for market newcomers, respectively.

6. Conclusions

Our first contribution to the literature for ethical institutions is that social actors participating in innovative climate finance markets, like the green bond, are driven by varying degrees by coercive, normative and mimetic drivers of institutional transitions. This is not only a new lens to examine how institutional and low-carbon transitions will occur for various economies, but how they will further influence the institution’s adaptive capacity response in a changing climate. Our second contribution is that informal or formal advocacy and pressure by high priority social actors will be a key driving force in changing prevailing institutional field logic and norms. Certain high priority social actors were identified in the case of India’s green bond market, however, the legitimacy and power that these actors bring might be relevant in the case of any transformational change, especially for financial markets that face significant transition and physical risks from climate change. If a low-carbon transition is to occur in less than a decade, there is a tangible need to have global and local high priority social actors engage with climate risks and opportunities, especially given their influence over key institutions and financial markets. Hence, the practical implication of our research is that institutional pressure of some form—whether it is through coercive, normative or mimetic means—will be needed to leverage the engagement from high priority social actors as advocates of climate finance and therefore further strengthen the adaptive capacity of the green bond market.

Although our research showcases a previously unexplored aspect of the green bond market by mapping its institutional drivers and adaptive capacity responses, it faces certain limitations. For instance, institutional theory is just one lens to examine the key drivers of the green bond market; there might be others such as stakeholder theory or behavioral economics. Furthermore, at the time of this study, the Indian market had only been around for three years, which did not provide sufficiently robust data to conduct a statistical significance test for causation of variables. Therefore, the ability to analyze the long-term effects of regulatory changes or determine causality was limited.

However, rich qualitative data from our interviews were able to supplement some of these gaps, and although we recommend future research to consider qualitative content analysis and reach those key stakeholders during the interview process, the ability to do so might be limited. Another key limitation is that when applying tools like the ACW, it is not only challenging but also contextual, and hence we recommend the use of market experts to weigh in when assigning scores to dimensions and criteria. Given these limitations, we suggest that future research should test our conceptual framework with other South Asian countries and measure the adaptive capacity of their own green bond markets. We recommend that future research can also look at the impact of green bond market on a country’s financial system and its effect in attracting greater foreign direct investment through international social actors (like institutional investors). On a theoretical level, future research should engage in linking different conceptual frameworks, such as the role of boundary organizations, and do so by using a variety of empirical tools like surveys or experimentation to discover a new perspective on this market and its evolution. One limitation of our study is the focus on institutional impacts; future research should address the interaction between institutional impact and financial motivations to participate in the green bond market. This interaction has not been addressed in our study. Another limitation of the study is the dominant qualitative approach. A quasi-experimental approach using different countries with different institutional drivers could help to analyze cause and effects of institutional impacts on the green bond market. The proposed research might help countries not only improve their climate finance flows, but also allow their institutions to be more adaptative and resilient in the face of future climate impacts.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, V.S. and O.W.; methodology, V.S.; validation, O.W.; formal analysis, V.S.; investigation, V.S. and O.W.; writing—original draft preparation, V.S.; writing—review and editing, O.W.; visualization, V.S.; supervision, O.W.; project administration, V.S.; funding acquisition, O.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was partially funded by the Smart Prosperity Institute’s Economics & Environmental Policy Research Network Grant (2017–2018) and the Centre for International Governance Innovation (CIGI) grant (2018–2019).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Anonymous coding of interviewee participants.

Table A1.

Anonymous coding of interviewee participants.

| Participant | Type of Organization |

|---|---|

| P1 | Regulator A |

| P2 | Regulator A |

| P3 | Regulator B |

| P4 | Regulator B |

| P5 | Issuer A |

| P6 | Issuer B |

| P7 | Industry Association A |

| P8 | Industry Association B |

| P9 | International Underwriter |

| P10 | Multilateral Financial Institution |

References

- Wallis, J.J. What Institutions Are: The Difference Between Social Facts, Norms, and Institutions and Their Associated Rules and Enforcement; University of Maryland, NBER, and CEPR: College Park, MD, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Ameli, N.; Drummond, P.; Bisaro, A.; Grubb, M.; Chenet, H. Climate finance and disclosure for institutional investors: Why transparency is not enough. Clim. Chang. 2020, 160, 565–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bapuji, H. Individuals, interactions and institutions: How economic inequality affects organizations. Hum. Relat. 2015, 68, 1059–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuenfschilling, L.; Truffer, B. The structuration of socio-technical regimes—Conceptual foundations from institutional theory. Res. Policy 2014, 43, 772–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiMaggio, P.; Powell, W. The iron cage revisited: Institutional isomorphism and collective rationality in organizational fields. Am. Soc. Rev. 1983, 48, 147–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flammer, C. Corporate green bonds. J. Financ. Econ. 2008. under review. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zerbib, O.D. The effect of pro-environmental preferences on bond prices: Evidence from green bonds. J. Bank. Financ. 2019, 98, 39–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hachenberg, B.; Schiereck, D. Are green bonds priced differently from conventional bonds? J. Asset. Manag. 2018, 19, 371–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiesa, M.; Barua, S. The surge of impact borrowing: The magnitude and determinants of green bond supply and its heterogeneity across markets. J. Sustain. Financ. Invest. 2019, 9, 138–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, T.; Yue, Q. How the game changer was generated? An analysis on the legal rules and development of China’s green bond market. Int. Environ. Agreem. Politics Law Econ. 2020, 20, 85–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bachelet, M.J.; Becchetti, L.; Manfredonia, S. The green bonds premium puzzle: The role of issuer characteristics and third-party verification. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larcker, D.F.; Watts, E.M. Where’s the Greenium? Rock Center for Corporate Governance at Stanford University Working Paper No. 239; Stanford University Graduate School of Business: Stanford, CA, USA, 2020; under review. [Google Scholar]

- Tripathy, A. Translating to risk: The legibility of climate change and nature in the green bond market: Translating to risk. Econ. Anthropol. 2017, 4, 239–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christophers, B. Risking value theory in the political economy of finance and nature. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 2018, 42, 330–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, L. Is it risky to go green? A volatility analysis of the green bond market. J. Sustain. Financ. Investig. 2016, 6, 263–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monasterolo, I.; Raberto, M. The EIRIN Flow-of-funds behavioural model of green fiscal policies and green sovereign bonds. Ecol. Econ. 2018, 144, 228–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reboredo, J.C. Green bond and financial markets: Co-movement, diversification and price spillover effects. Energy Econ. 2018, 74, 38–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebelle, M.; Lajili Jarjir, S.; Sassi, S. Corporate green bond issuances: An international evidence. J. Risk Financ. Manag. 2020, 13, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, A.F. The BRICS’ new development bank: Shifting from material leverage to innovative capacity. Glob. Policy 2017, 8, 275–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.Y. Green bonds in China and the Sino-British collaboration: More a partnership of learning than commerce. Br. J. Polit. Int. Rel. 2019, 21, 207–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, K. Investors as regulators: Green bonds and the governance challenge of sustainable finance revolution. Stanford J. Int. Law 2018, 49, 54. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, J.; Termeer, C.; Klostermann, J.; Meijerink, S.; van den Brink, M.; Jong, P.; Nooteboom, S.; Bergsma, E. The adaptive capacity wheel: A method to assess the inherent characteristics of institutions to enable the adaptive capacity of society. Environ. Sci. Policy 2010, 13, 459–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubash, N. New regulatory institutions in infrastructure: From de-politicization to creative politics. In Rethinking Public Institutions in India; Kapur, D., Mehta, P.B., Vaishnav, M., Eds.; Oxford University Press: New Delhi, India, 2017; pp. 225–268. [Google Scholar]

- Climate Bonds Initiative. Green Bond Market Summary: 2018 at a Glance; Climate Bonds Initiative: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Weber, O.; Saravade, V. Green Bonds: Current Development and Their Future; CIGI Papers No 210; Centre for International Governance Innovation: Waterloo, ON, Canada, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Klijn, E.H.; Koppenjan, J.F.M. Institutional design: Changing institutional features of networks. Pub. Manag. Rev. 2006, 6, 141–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christophers, B. Environmental beta or how institutional investors think about climate change and fossil fuel risk. Ann. Am. Assoc. Geogr. 2019, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Y.; Geobey, S.; Weber, O.; Lin, H. The impact of green lending on credit risk in China. Sustainability 2018, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, M.; Guthrie, P. Crossing the energy efficiency chasm: An assessment of the barriers to institutional investment at scale, a UK perspective. J. Sustain. Financ. Invest. 2016, 6, 15–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, O.; Feltmate, B. Sustainable Banking and Finance: Managing the Social and Environmental Impact of Financial Institutions; University of Toronto Press: Toronto, TO, Canada, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Broadstock, D.C.; Cheng, L.T.W. Time-varying relation between black and green bond price benchmarks: Macroeconomic determinants for the first decade. Financ. Res. Lett. 2019, 29, 17–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolbert, P.S.; Zucker, L.G. Institutional sources of change in the formal structure of organizations: The diffusion of civil service reform, 1880–1935. Adm. Sci. Q. 1983, 28, 22–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doh, J.; Guay, T. Corporate responsibility, public policy, and NGO activism in europe and the United States: An institutional-stakeholder perspective. J. Manag. Stud. 2006, 43, 48–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weikmans, R.; Roberts, J.T. The international climate finance accounting muddle: Is there hope on the horizon? Clim. Develop. 2017, 11, 97–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehlers, T.; Packer, F. Green bond finance and certification. BIS Q. Rev. 2017, 9, 89–104. [Google Scholar]

- Banga, J. The green bond market: A potential source of climate finance for developing countries. J. Sustain. Financ. Investig. 2019, 9, 17–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riordan, R. Sustainable Finance Primer Series: Transition Bonds; Institute for Sustainable Finance, Queen’s University: Kingston, ON, Canada, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Febi, W.; Schäfer, D.; Stephan, A.; Sun, C. The impact of liquidity risk on the yield spread of green bonds. Finance Res. Lett. 2018, 27, 53–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, J.; Liberatore, S.; Flensborg, C. Social investing and structured products: Trends, challenges, and opportunities. J. Struct. Financ. 2013, 18, 222–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roslen, S.N.M.; Yee, L.S.; Ibrahim, S.A.B. Green Bond and shareholders’ wealth: A multi-country event study. Int. J. Glob. Small Bus. 2017, 9, 61–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horsch, A.; Richter, S. Climate change driving financial innovation: The case of green bonds. J. Struct. Financ. 2017, 23, 70–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergsma, E.; Gupta, J.; Jong, P. Does individual responsibility increase the adaptive capacity of society? The case of local water management in the Netherlands. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2012, 64, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silveira, A.R.; Richards, K.S. The link between polycentrism and adaptive capacity in river basin governance systems: Insights from the Rhine river and the Zhujiang (Pearl River) Basin. Ann. Assoc. Am. Geogr. 2013, 103, 319–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van den Brink, M.; Meijerink, S.; Termeer, C.; Gupta, J. Climate-proof planning for flood-prone areas: Assessing the adaptive capacity of planning institutions in the Netherlands. Reg. Environ. Chan. 2014, 1, 981–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corbin, J.; Strauss, A. Grounded theory research: Procedures, canons and evaluative criteria. Qual. Sociol. 1990, 13, 3–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bettini, Y.; Brown, R.R.; de Haan, F.J. Exploring institutional adaptive capacity in practice: Examining water governance and adaptation in Australia. Ecol. Soc. 2015, 20, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Climate Bonds Initiative. Bonds and Climate Change: The State of the Market India 2017; Climate Bonds Initiative: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- The World Bank. GDP Growth (Annual %)—India. The World Bank Data. 2018. Available online: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.MKTP.KD.ZG?locations=IN (accessed on 1 September 2020).

- Climate Bonds Initiative & UNEP Finance Inquiry. Scaling Up Green Bond Markets for Sustainable Development; Climate Bonds Initiative: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Climate Bonds Initiative. India Country Briefing—July 2018; Climate Bonds Initiative: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Reserve Bank of India. Frequently Asked Questions: Priority Sector Limits; Reserve Bank of India: Mumbai, India, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Kala, V.; Garg, V. Issue Paper: Green Bonds in India. Partnership to Advance Clean Energy-Deployment (PACE-D) Technical Assistance Program; United States Agency for International Development: Olympia, WA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, N.; Vaze, P.; Kidney, S. Moving from growth to development: Financing green investment in India. In Financing Green Transitions: Commitments, Capabilities and Capacities; Saran, S., Ed.; The Observer Research Foundation: New Delhi, India, 2019; pp. 98–115. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, K. Green Bond Issuers are Poised to Charge a Premium. Financial Times. Available online: https://www.ft.com/content/9396fb28-ca2b-11e7-ab18-7a9fb7d6163e (accessed on 22 November 2017).

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).