Low Internet Penetration in Sub-Saharan Africa and the Role of LEO Satellites in Addressing the Issue

Abstract

1. Introduction

- We discuss the problem of low Internet penetration in SSA and analyse the factors responsible for the low Internet penetration.

- We present visible LEO business models in SAA with practical examples.

- We analyse the opportunity and challenge of LEO satellite services in SSA and proffer possible solutions.

2. Review Methodology

3. The Problem of Low Internet Penetration in Sub-Saharan Africa

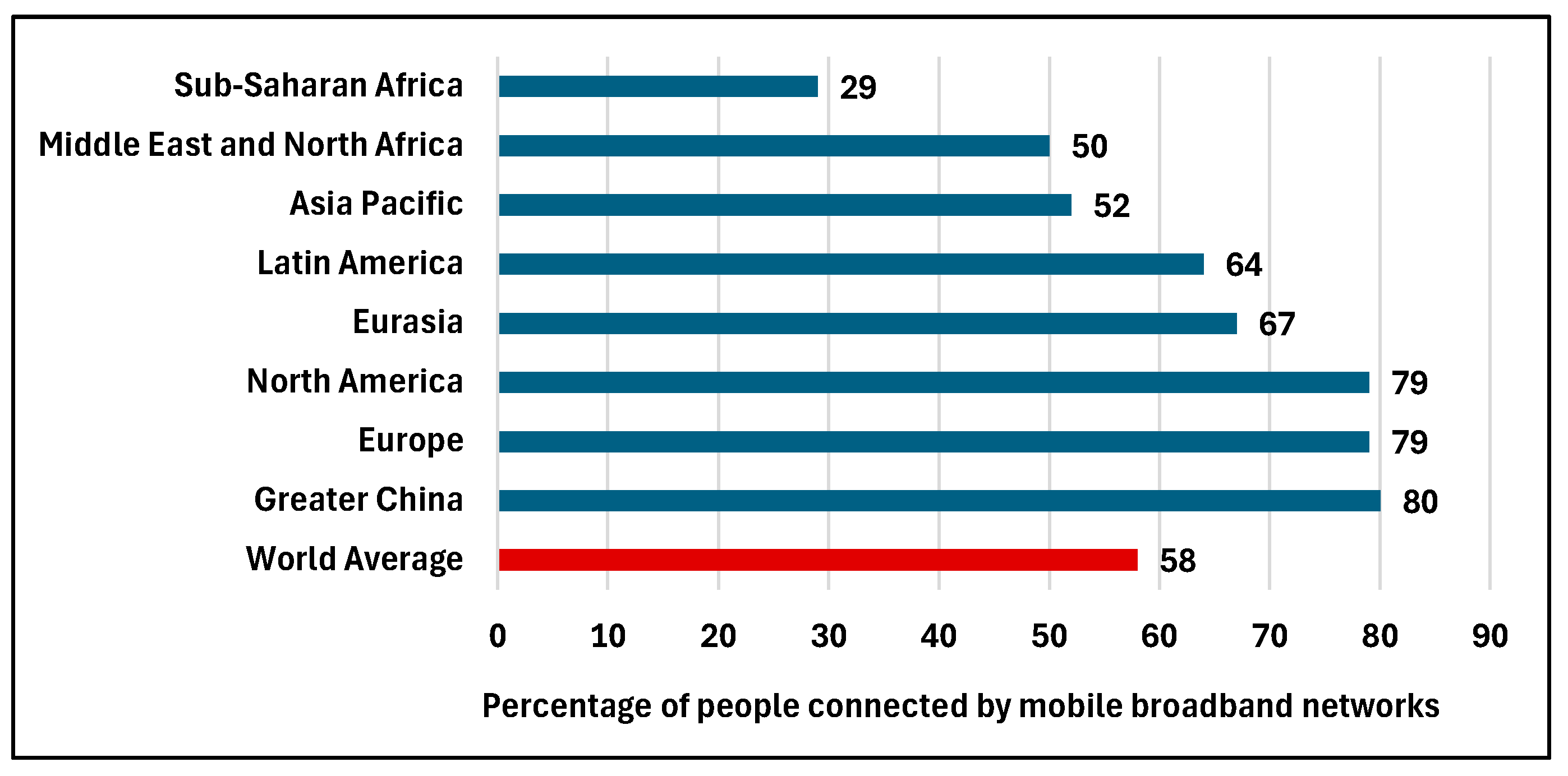

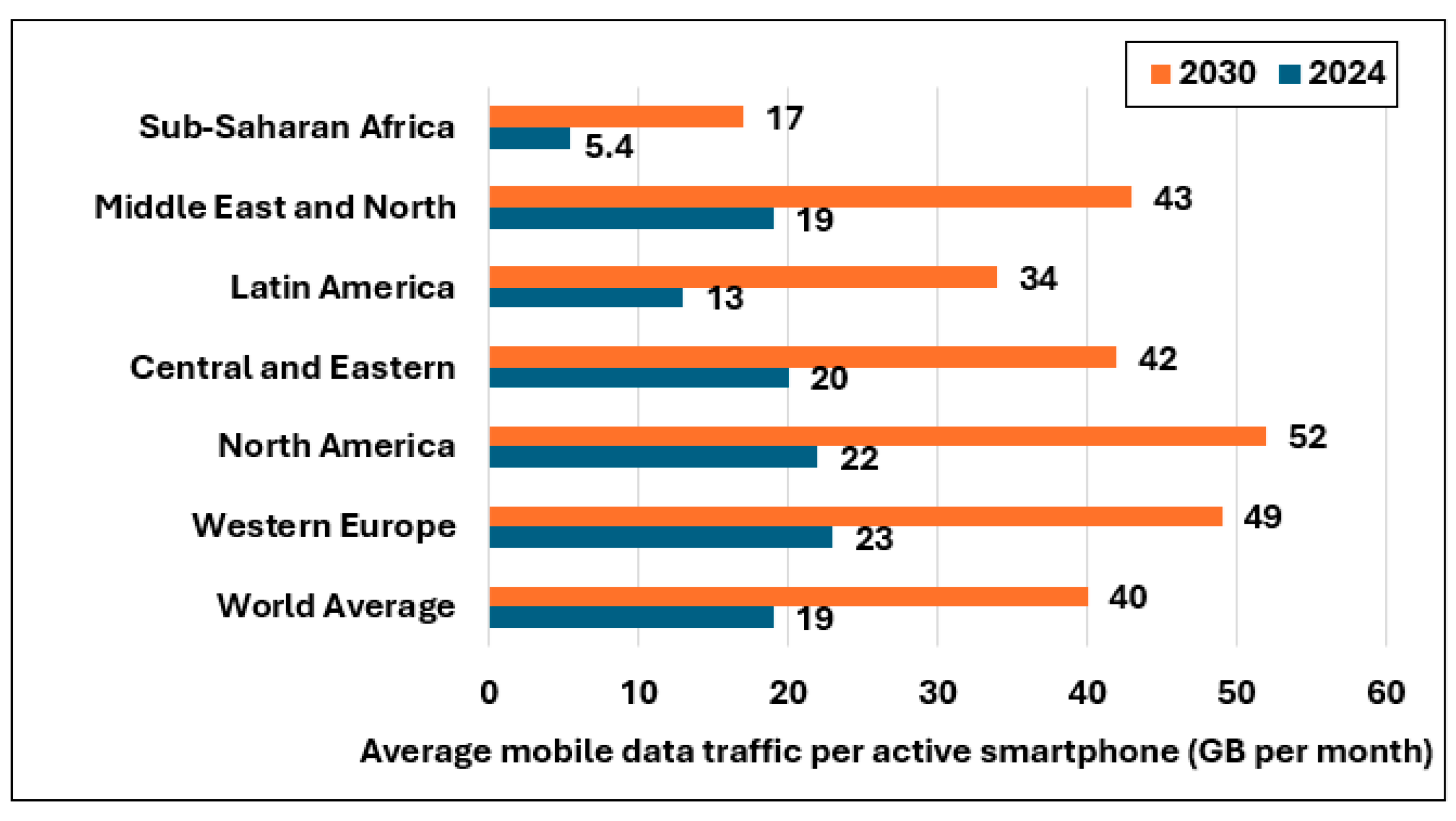

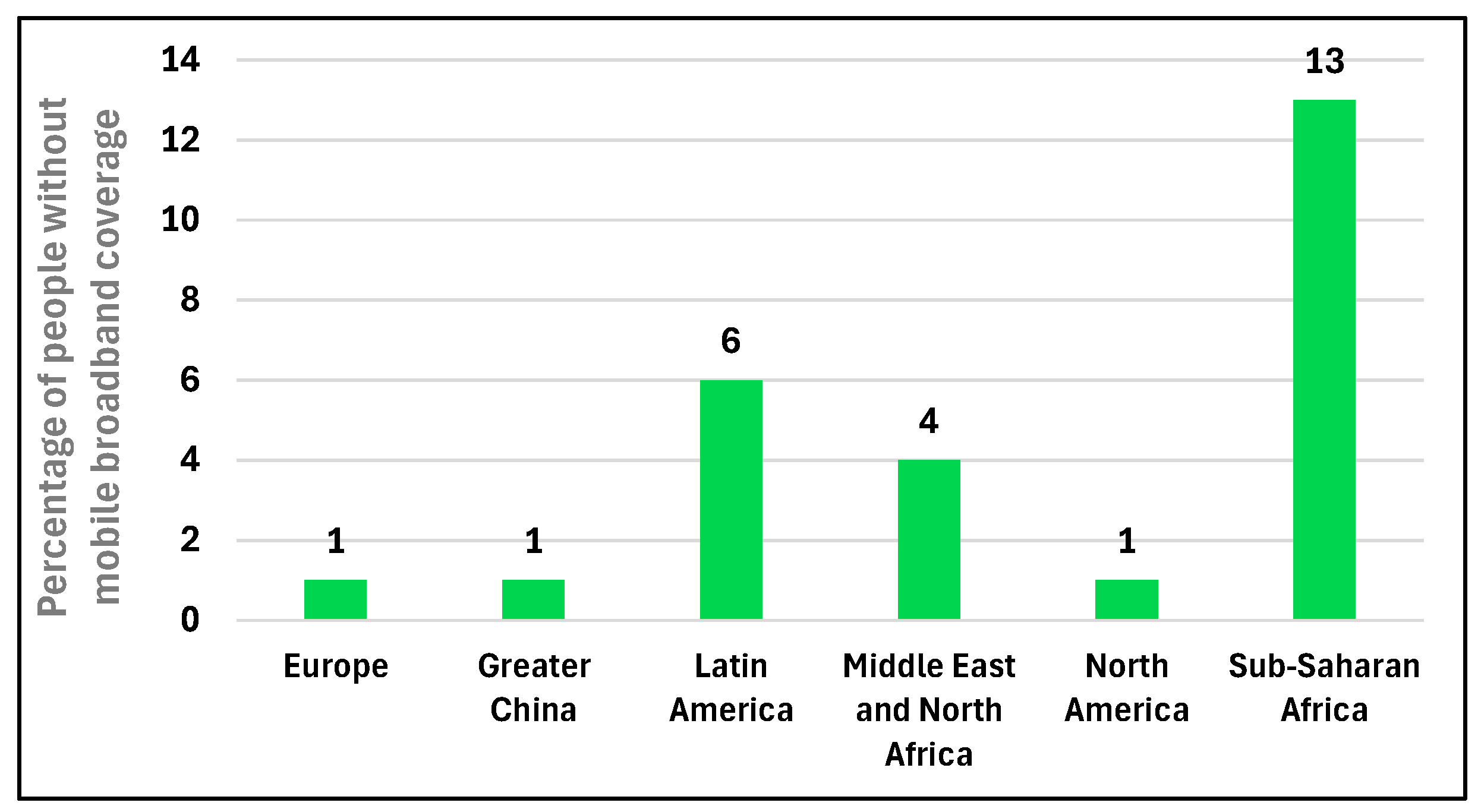

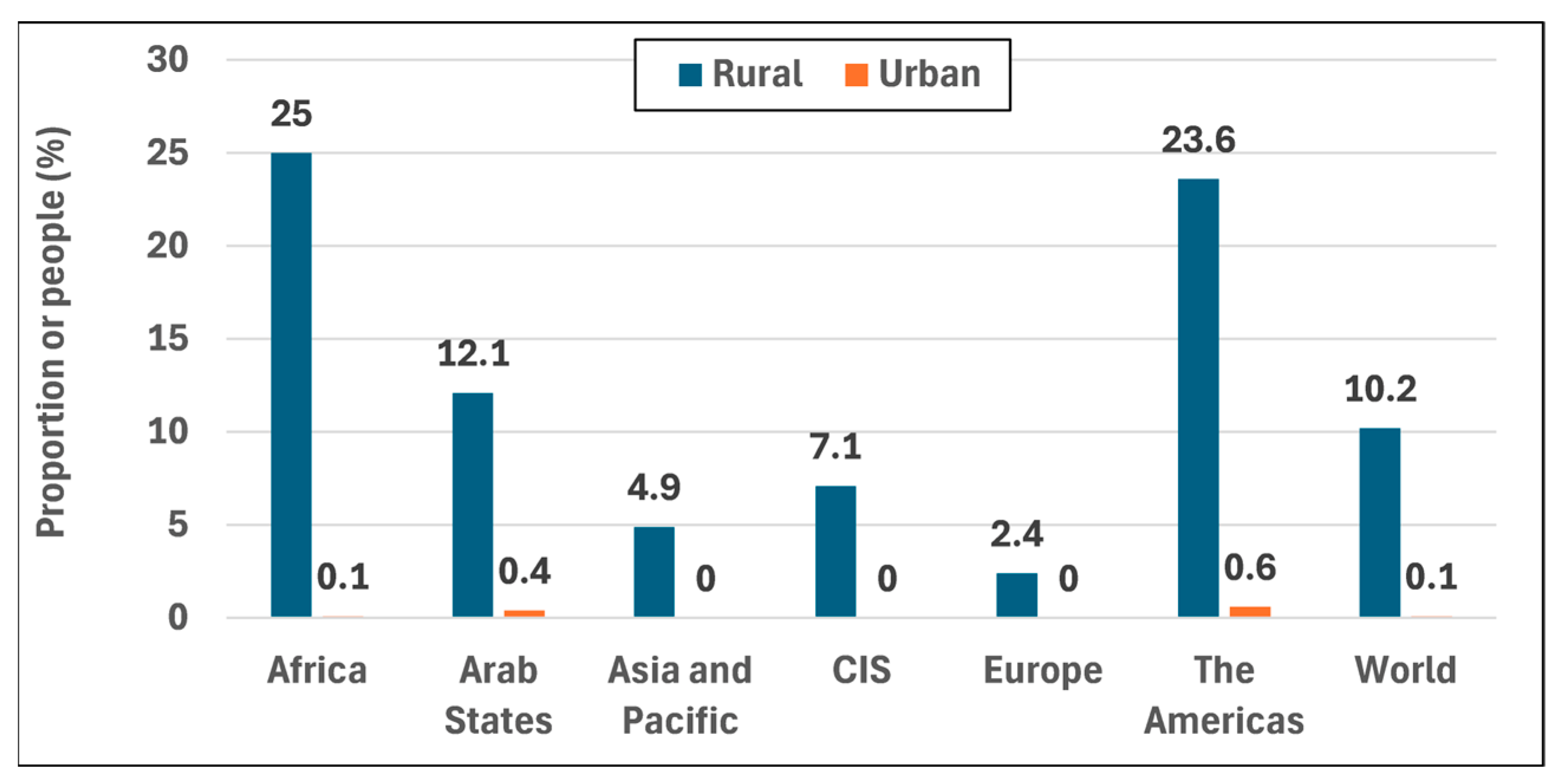

3.1. Availability of Broadband Network Service

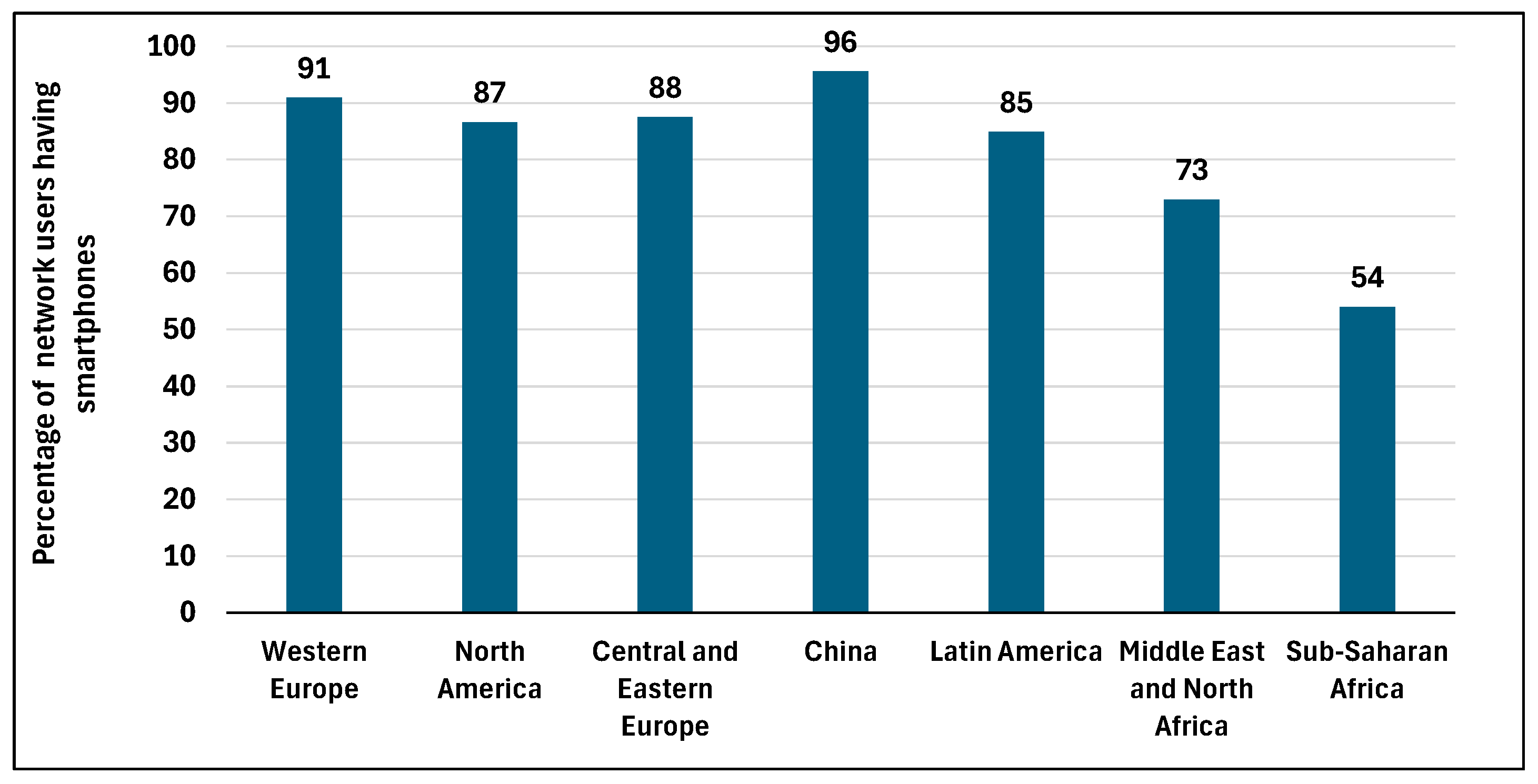

3.2. Mobile Device Affordability

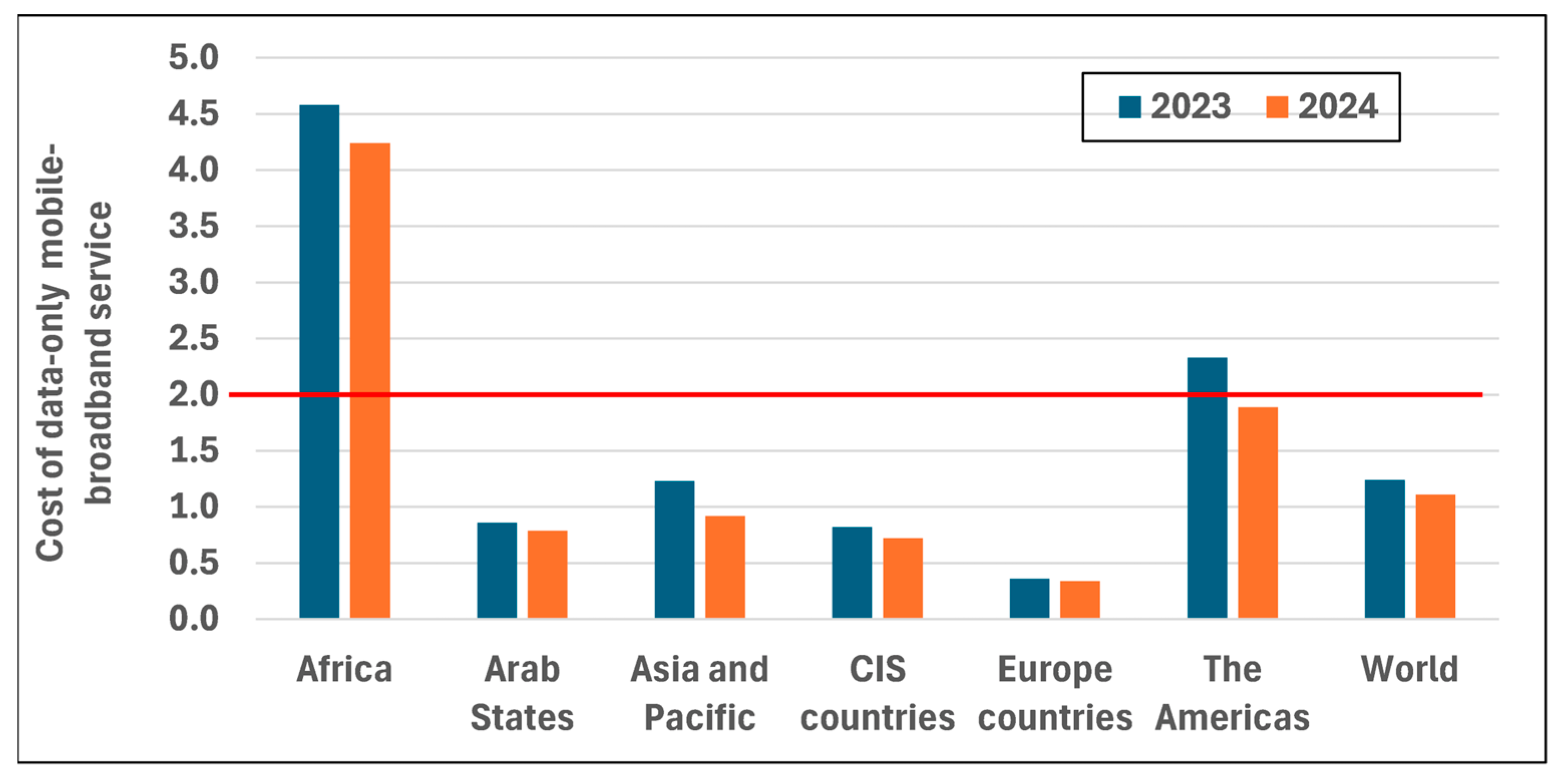

3.3. Internet Service Affordability

3.4. Digital Ability

3.5. Government Regulation Policy

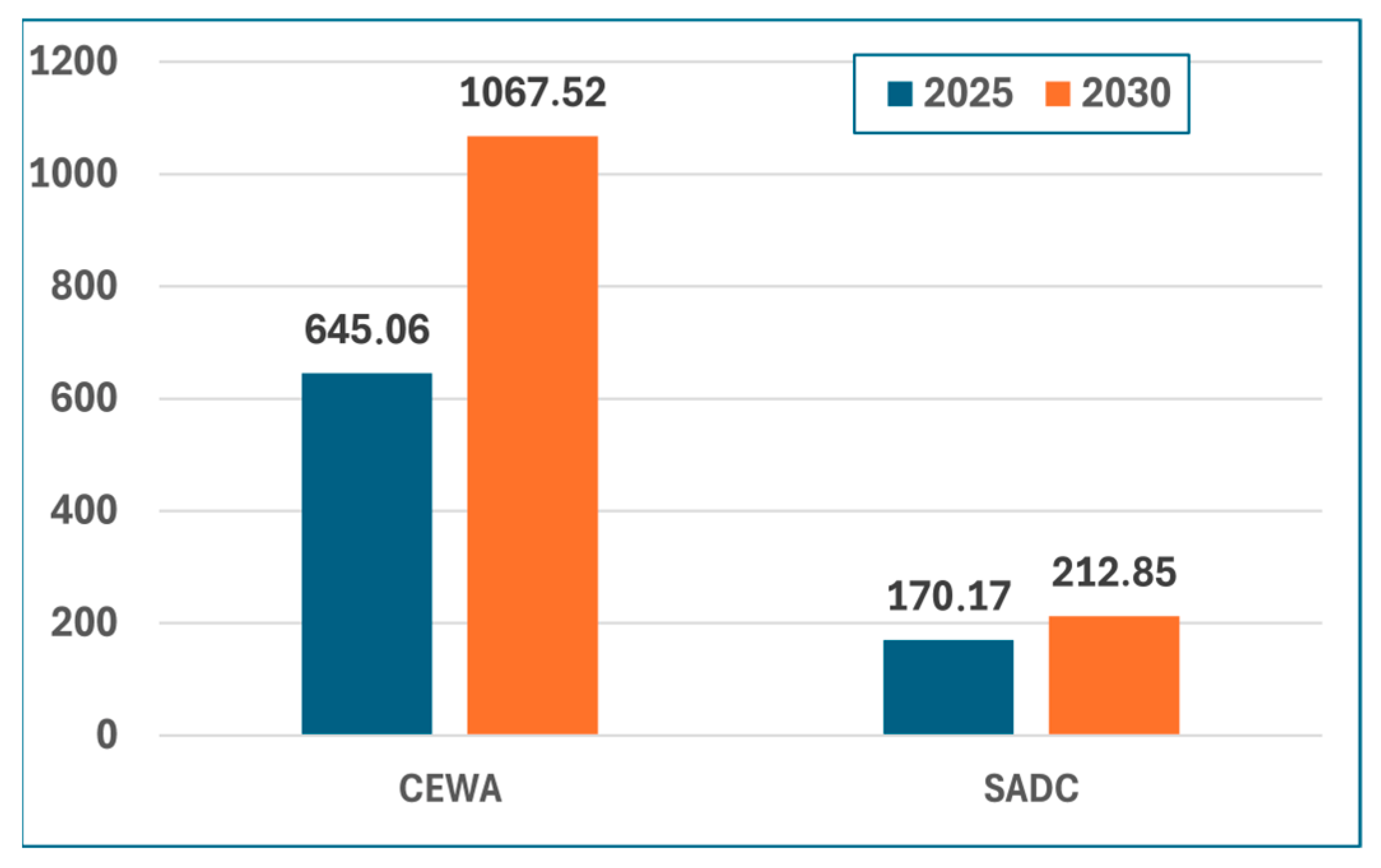

3.6. Deficit of Network-Supporting Infrastructure

4. Popular Internet Access Networks in Sub-Saharan Africa

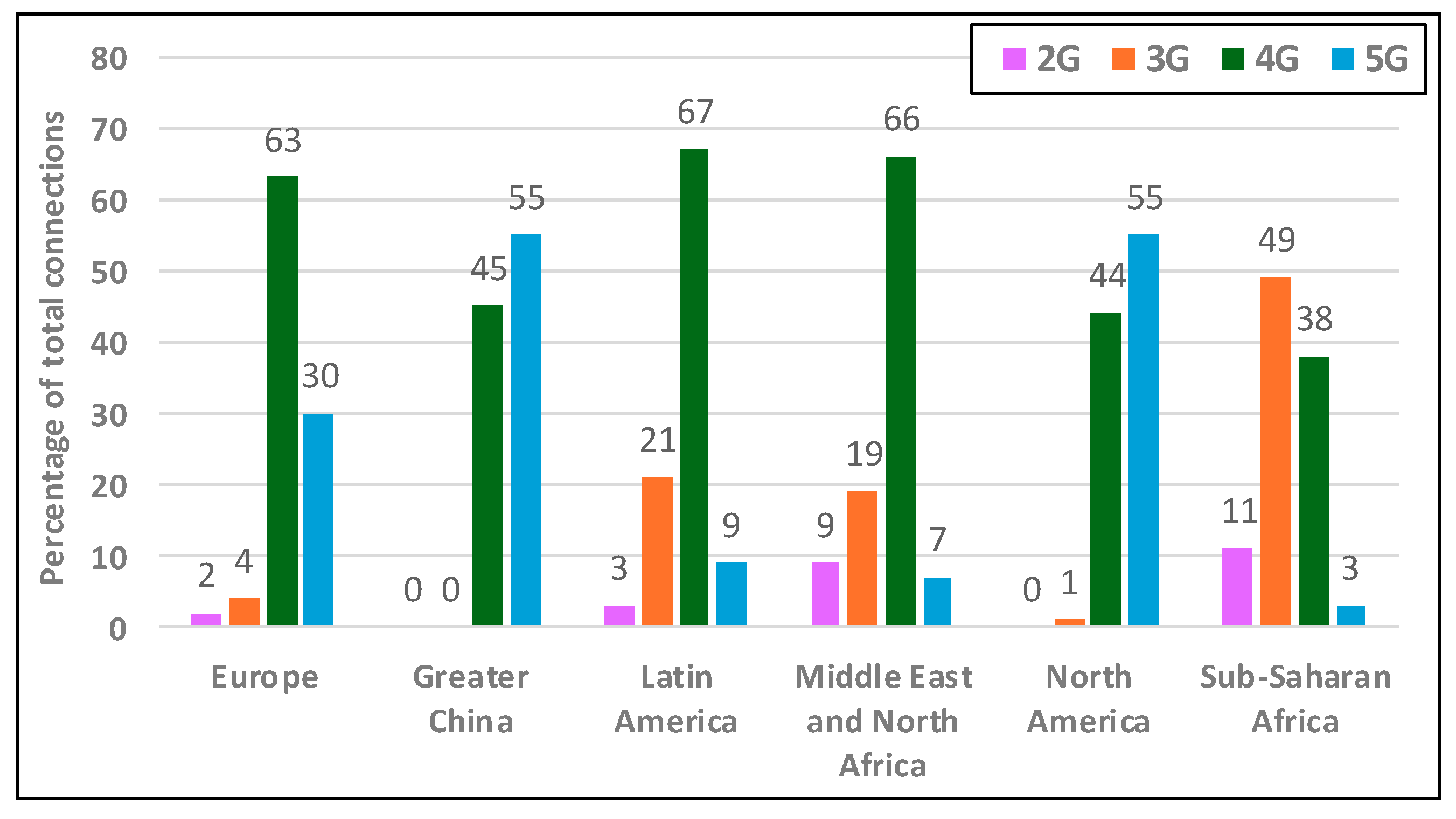

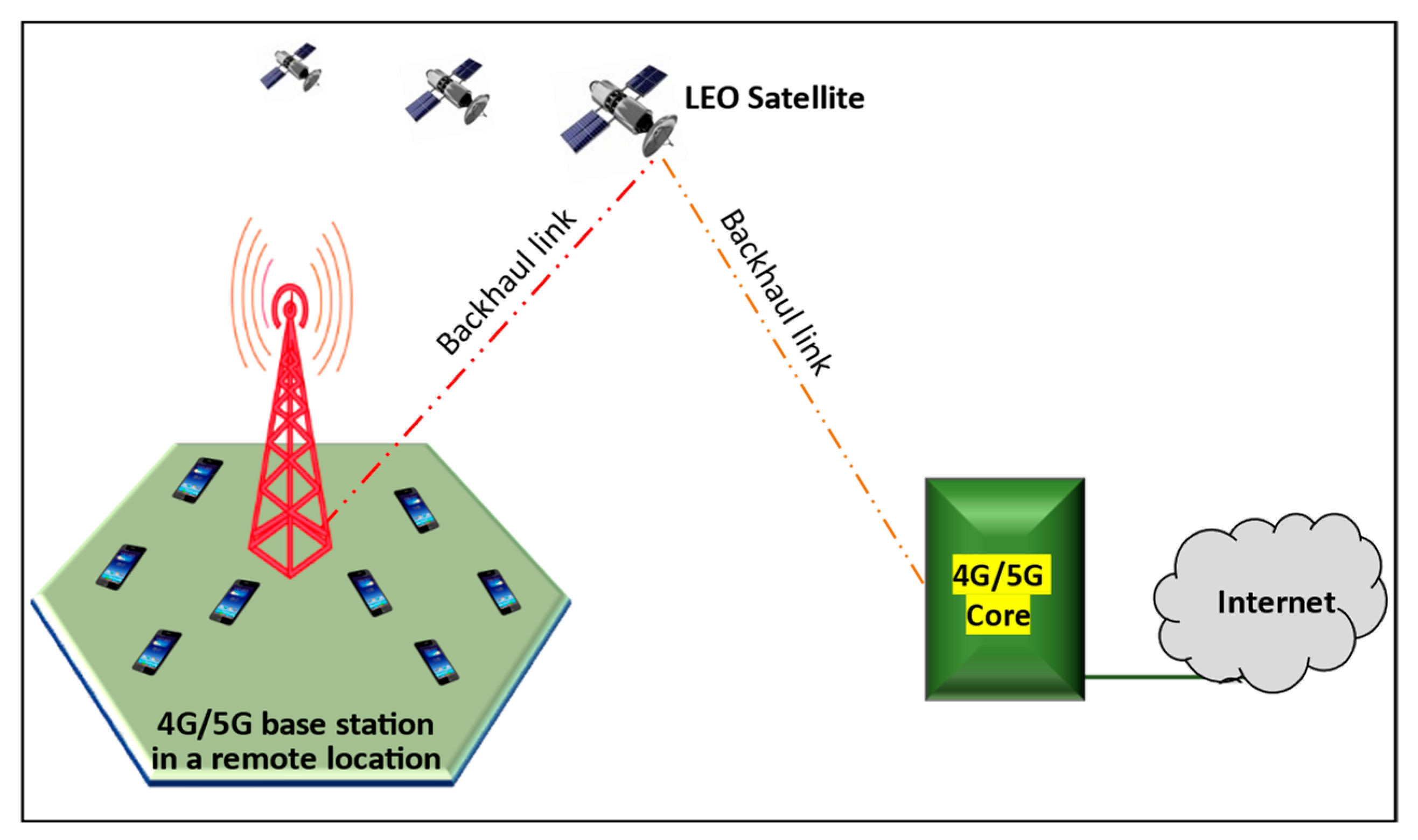

4.1. Mobile Broadband Network

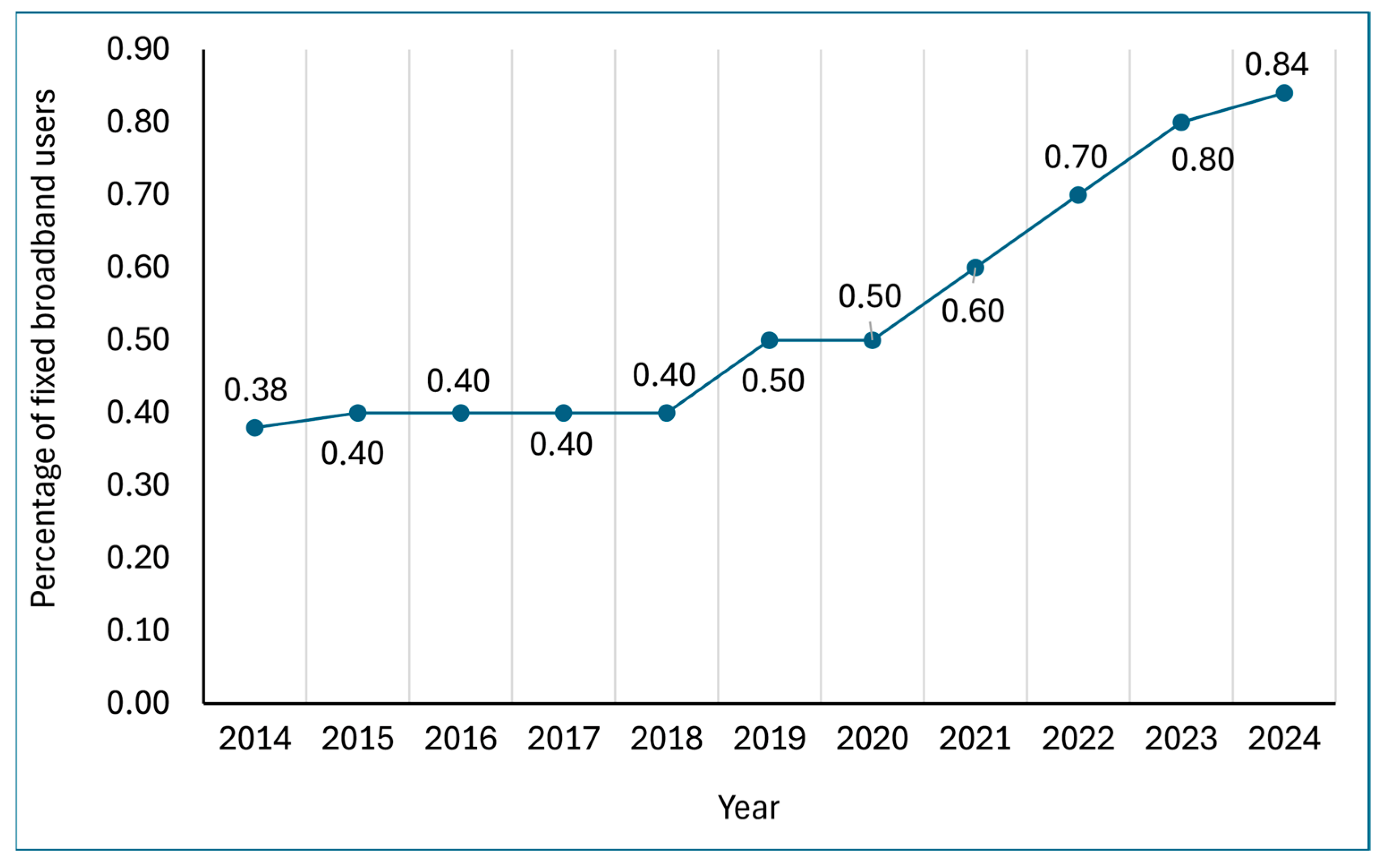

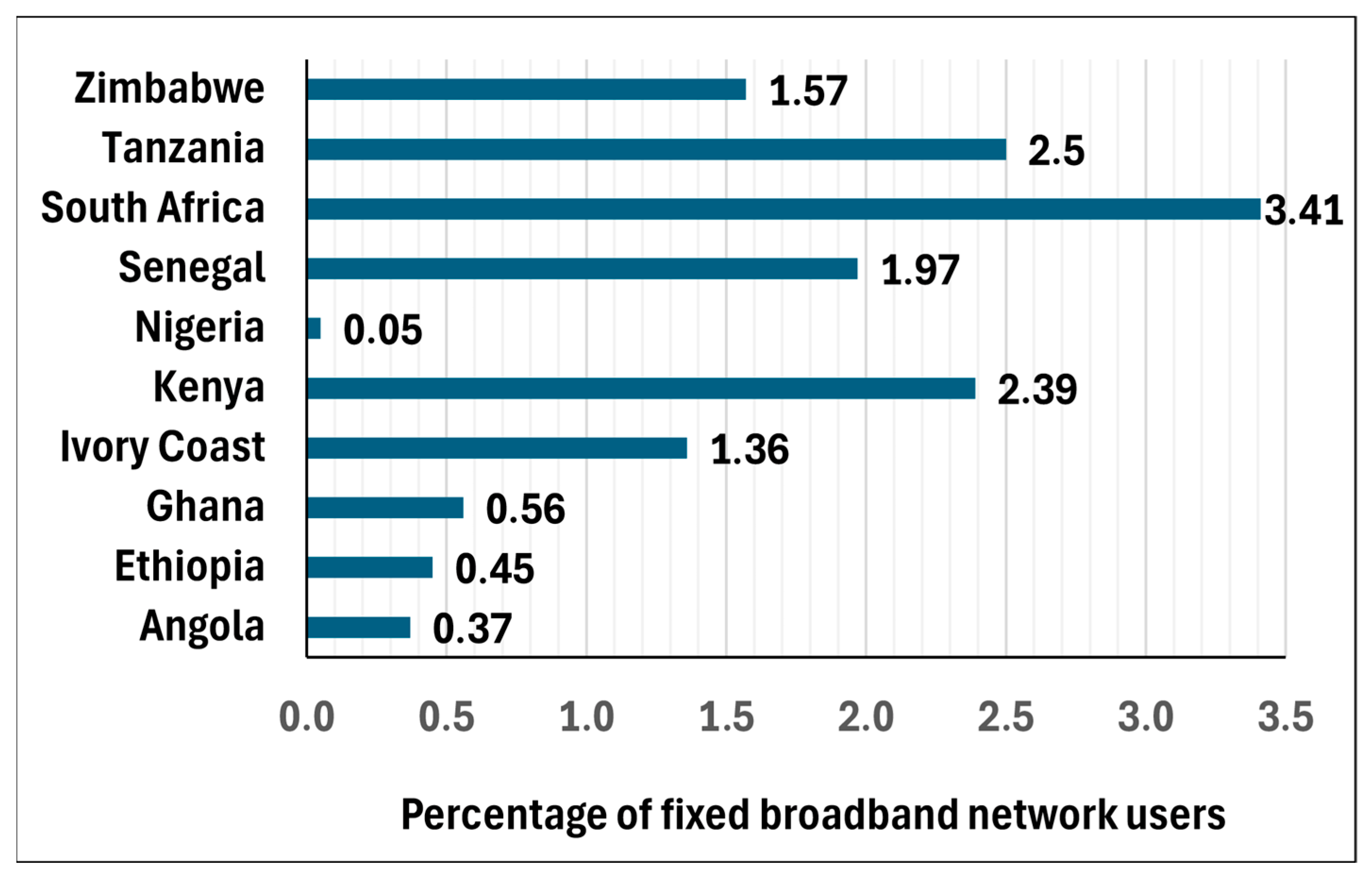

4.2. Fixed Broadband Network (FTX, DSL, FWA)

4.3. Wi-Fi

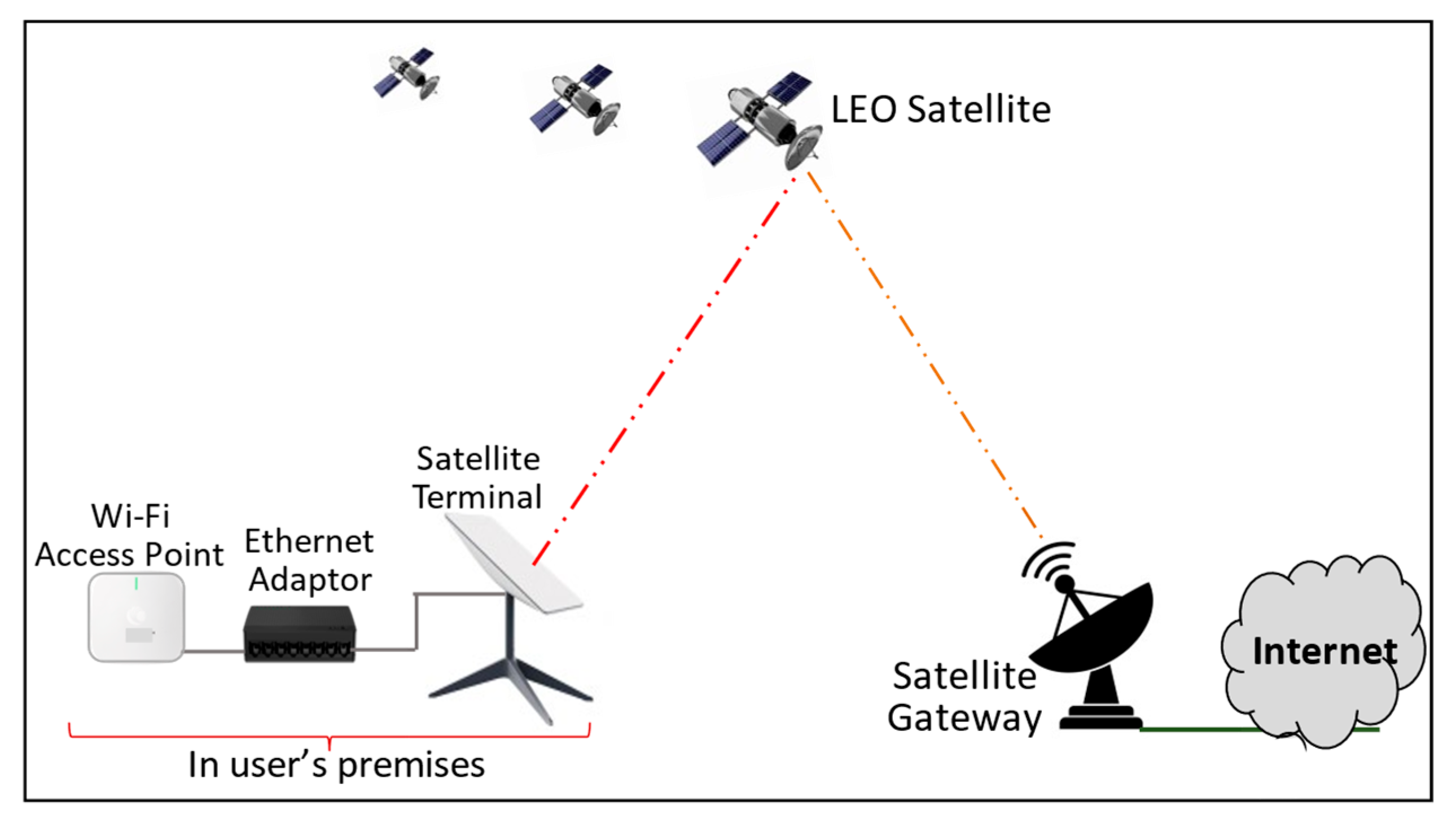

4.4. Satellite Network

5. LEO Satellite Opportunities for Enhancing Internet Penetration

- Low latency, which make them suitable for supporting real-time services.

- Low power consumption because of short distance and low propagation loss between LEO and user devices.

- High capacity and throughput per unit area because frequency reuse is more effective in LEO satellite networks than in MEO and GEO networks due to the smaller beam footprints of LEO satellites. This allows for greater spatial reuse of frequencies, which enhances cell densification in LEO networks, and thus enables higher capacity and throughput per unit area, particularly with multi-beam antennas.

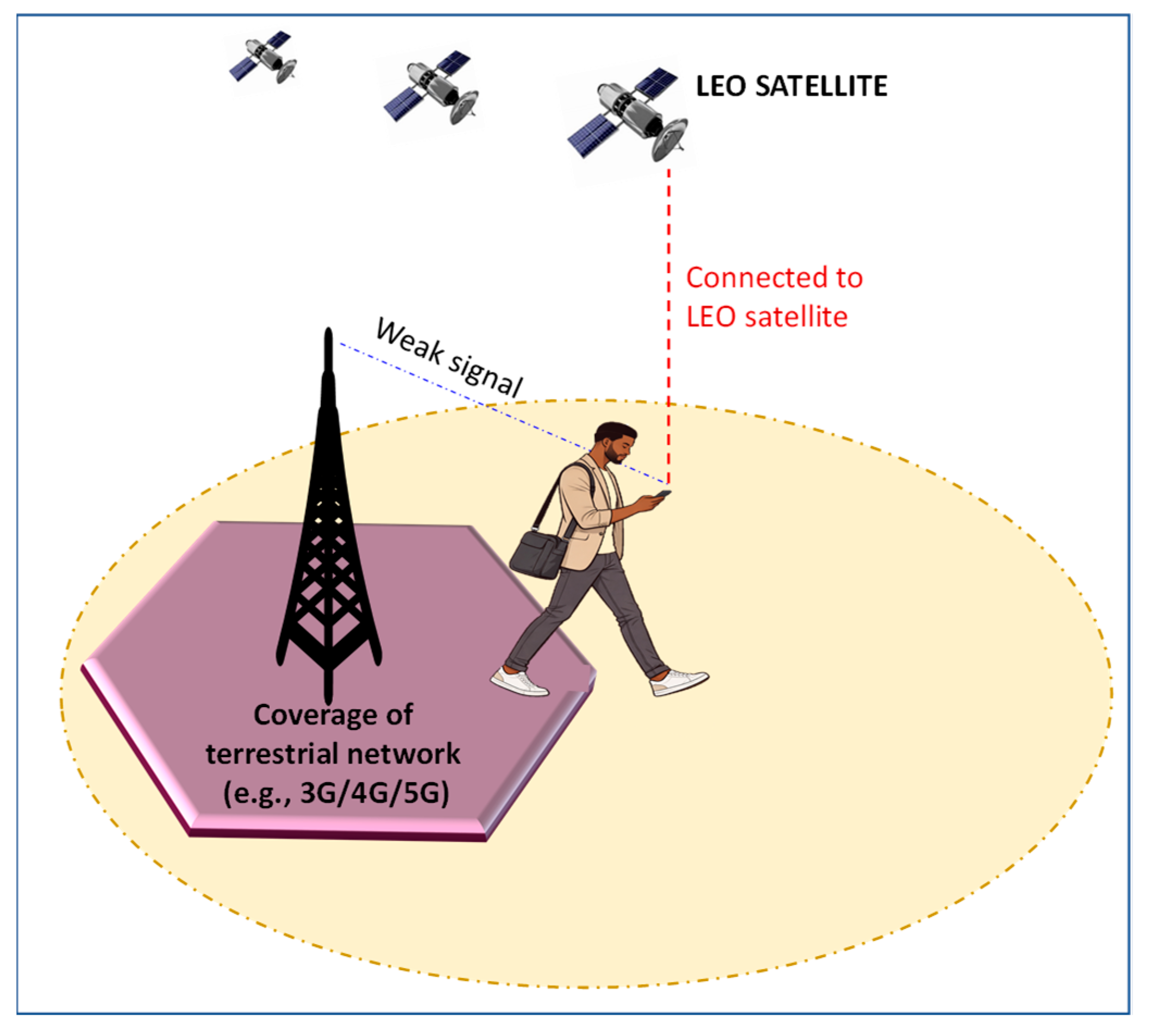

- Consistent capacity and QoS in urban, rural, and remote areas. Unlike terrestrial networks (e.g., 4G and 5G mobile networks) where network operators usually deploy more capacity in urban areas than in rural areas because the cost of deploying network increases as population density decreases, the LEO satellite network can provide the same capacity and QoS in urban, rural, and remote areas because the satellites are in constant motion around the globe. Thus, the LEO satellite network can augment the capacity of terrestrial networks in urban areas while meeting the capacity need in underserved rural and unserved remote areas.

- Global coverage with a constellation of LEO satellites. Thus, LEO satellites can be used to provide coverage in rural and remote locations.

- Resilience to natural and manmade disasters. LEO satellites can improve network resilience in zones prone to natural and man-made disasters.

- High frequency of handover and handover complexity because a large number of LEO satellites are required to provide global and continuous coverage. Therefore, each LEO satellite has short visibility time, and frequent handovers from one LEO satellite to another are required to ensure users’ devices are continuously connected to the Internet.

- Problem of interference as a result of the large constellation of LEO satellites required to provide global connectivity. There is a need to mitigate interference and optimise spectrum utilisation across different nations and regions by performing frequency switching. This involves dynamically switching between frequency bands to avoid interference with other satellites, ground stations, or terrestrial networks, particularly when LEO satellites cross geographic boundaries or experience changes in orbital position.

- High cost of launching and maintaining LEO satellites and the ground stations. It is highly capital intensive to launch and maintain LEO satellites and the ground stations. Moreover, LEO satellites have a limited operational lifespan, and therefore, there is a need for regular replacement of LEO satellites in orbit.

6. LEO Satellite Business Models in SSA

6.1. Business to Consumer

6.2. Business to Business

6.3. Business to Government

7. Challenges of LEO Satellite Service Penetration in SSA and Possible Solutions

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lappalainen, A.; Rosenberg, C. Can 5G fixed broadband bridge the rural digital divide? IEEE Commun. Stand. Mag. 2022, 6, 79–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GSM Association. The Mobile Economy 2023. Available online: https://www.gsma.com/solutions-and-impact/connectivity-for-good/mobile-economy/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/270223-The-Mobile-Economy-2023.pdf (accessed on 2 July 2025).

- GSM Association. The Mobile Economy 2025. Available online: https://www.gsma.com/solutions-and-impact/connectivity-for-good/mobile-economy/wp-content/uploads/2025/02/030325-The-Mobile-Economy-2025.pdf (accessed on 2 July 2025).

- Ericsson Mobility Report (2025, June). Available online: https://elements.visualcapitalist.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/1750752177192.pdf (accessed on 27 June 2025).

- Ahmmed, T.; Alidadi, A.; Zhang, Z.; Chaudhry, A.U.; Yanikomeroglu, H. The digital divide in Canada and the role of LEO satellites in bridging the gap. IEEE Commun. Mag. 2022, 60, 24–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Homssi, B.; Al-Hourani, A.; Wang, K.; Conder, P.; Kandeepan, S.; Choi, J.; Allen, B.; Moores, B. Next generation mega satellite networks for access equality: Opportunities, challenges, and performance. IEEE Commun. Mag. 2002, 60, 18–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cariolle, J. International connectivity and the digital divide in Sub-Saharan Africa. Inf. Econ. Policy 2021, 55, 100901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ericsson. Ericsson Mobility Report—November 2024. Available online: https://www.ericsson.com/en/reports-and-papers/mobility-report/reports (accessed on 8 December 2025).

- ITU. Measuring Digital Development: The Affordability of ICT Services 2024. ITU, ISBN: 978-92-61-40541-0. Available online: https://www.itu.int/itu-d/reports/statistics/affordability2024/ (accessed on 4 June 2025).

- Ferro, E.; Helbig, N.C.; Gil-Garcia, J.R. The role of IT literacy in defining digital divide policy needs. Gov. Inf. Q. 2011, 28, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dupoux, P.; Dhanani, Q.; Oyekan, T.; Rafiq, S.; Yearwood, K. Africa’s Opportunity in Digital Skills and Climate Analytics. Boston Consulting Group 2022. Available online: https://www.bcg.com/publications/2022/africas-opportunity-in-digital-skills (accessed on 12 June 2025).

- Pick, J.B.; Sarkar, A. The Global Digital Divides: Explaining Change; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2015; pp. 275–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaoub, A.; Giordani, M.; Lall, B.; Bhatia, V.; Kliks, A.; Mendes, L.; Rabie, K.; Saarnisaari, H.; Singhal, A.; Zhang, N.; et al. 6G for bridging the digital divide: Wireless connectivity to remote areas. IEEE Wirel. Commun. 2021, 29, 160–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MTN Group. Quarterly Update for the Period Ended 31 March 2025. Available online: https://www.mtn.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/MTN-Group-Q1-25-results-JSE-SENS-1.pdf (accessed on 4 June 2025).

- Airtel Africa. Airtel Africa plc Results for Quarter Ended 30 June 2025. Available online: https://www.zawya.com/en/press-release/companies-news/airtel-africa-plc-results-for-quarter-ended-30-june-2025-bdqviahd (accessed on 4 August 2025).

- Vodacom Group Limited. Fact Sheet as at 31 March 2025. Available online: https://vodacom.com/pdf/about-us/fact-sheet/2024/vodacom-fy2024_-fact-sheet.pdf (accessed on 7 August 2025).

- Orange, a Multi-Service Operator in Africa and the Middle East. Available online: https://www.orange.com/en/africa-and-middle-east (accessed on 13 August 2025).

- Ethio Telecom. Ethio Telecom 2024/25 Semi-Annual Business Performance Report. 12 February 2025. Available online: https://www.ethiotelecom.et/ethio-telecom-2024-25-semi-annual-business-performance-report/ (accessed on 13 August 2025).

- Nokia. Nokia MEA Mobile Broadband Index 2025: Accelerating 5G Investments in MEA Fuels Data Demand and Digital Revolution; Nokia: Espoo, Finland, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank Group. Fixed Broadband Subscriptions (per 100 People)—Sub-Saharan Africa. 2025. Available online: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/IT.NET.BBND.P2 (accessed on 13 August 2025).

- ICASA. Independent Communications Authority of South Africa. The State of the ICT Sector Report of South Africa. 31 March 2025. Available online: https://www.icasa.org.za/uploads/files/The-State-of-the-ICT-Sector-Report-of-South-Africa-2025.pdf (accessed on 29 July 2025).

- NCC. Nigeria Communications Commission. Industry Statistics. 26 August 2025. Available online: https://www.ncc.gov.ng/market-data-reports/industry-statistics (accessed on 10 September 2025).

- CA. Communication Authority of Kenya. Third Quarter Sector Statistics Report for the Financial Year 2024/2025. 2025. Available online: https://www.ca.go.ke/sites/default/files/2025-06/Sector%20Statistics%20Report%20Q3%202024-2025.pdf (accessed on 29 July 2025).

- INACOM—Instituto Angolano das Comunicações. INACOM Apresenta o Relatório Anual Estatístico 2024. 12 June 2025. Available online: https://inacom.gov.ao/2025/06/12/o-inacom-apresenta-o-relatorio-anual-estatistico-2024/ (accessed on 29 July 2025).

- TCRA. Tanzanian Communications Regulatory Authority Communication Statistics Report, Quarter Ending December 2024. 2025. Available online: https://www.tcra.go.tz/uploads/text-editor/files/Communication%20Statistics%20Report%20-%20December%202024_1736975031.pdf (accessed on 30 July 2025).

- ITU. Measuring Digital Development. State of Digital Development and Trends in the Africa Region: Challenges and Opportunities. Available online: https://www.itu.int/dms_pub/itu-d/opb/ind/D-IND-SDDT_AFR-2025-PDF-E.pdf (accessed on 25 August 2025).

- Westphal, C.; Han, L.; Li, R. LEO satellite networking relaunched: Survey and current research challenges. ITU J. Future Evol. Technol. 2023, 4, 711–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Population Division, via World Bank (2025)—Processed by Our World in Data. Available online: https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/share-of-population-urban (accessed on 13 August 2025).

- Starlink. 2025. Available online: https://www.starlink.com/ (accessed on 13 August 2025).

- Starlink Terminals Sold Out in Five African Countries as Demand Soars—The Mail and Gurdian, 4 November 2024. Available online: https://mg.co.za/business/2024-11-04-starlink-terminals-sold-out-in-five-african-countries-as-demand-soars/?utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed on 25 August 2025).

- AMN. Africa Mobile Networks. Our Coverage. 2025. Available online: https://amn.com/our-coverage/ (accessed on 18 August 2025).

- Vodacom Group. Media Releases. Vodafone and AST SpaceMobile Unveil Launch Plans for Space-Based Mobile Network Initially Reaching 1.6 Billion People. 17 December 2020. Available online: https://www.vodacom.com/news-article.php?articleID=7592 (accessed on 10 August 2025).

- LYNK. FCC Grants Lynk First-Ever License for Commercial Satellite-Direct-to-Standard Mobile-Phone Service. 16 September 2022. Available online: https://lynk.world/news/fcc-grants-lynk-first-ever-license-for-commercial-satellite-direct-to-standard-mobile-phone-service/ (accessed on 18 August 2025).

- Connecting Africa. Airtel, SpaceX Partner to Expand Starlink Across Africa. Available online: https://www.connectingafrica.com/connectivity/airtel-spacex-partner-to-expand-starlink-across-africa (accessed on 18 August 2025).

- ESA. Satellite Way for Education 2. 13 July 2015. Available online: https://connectivity.esa.int/projects/sway4edu2 (accessed on 18 August 2025).

- DO4AFRICA. Satellite to Provide Internet Access to Rwandan Rural Schools. 11 July 2019. Available online: https://www.do4africa.org/en/projets/icyerekezo-2/ (accessed on 18 August 2025).

- Connecting Africa. Nigcomsat, Eutelsat Partner for LEO Services in Nigeria. 20 January 2025. Available online: https://www.connectingafrica.com/connectivity/nigcomsat-eutelsat-partner-for-leo-services-in-nigeria (accessed on 18 August 2025).

| Mobile Broadband Operator | Number of Active Data Subscribers in Millions (Year) | Countries of Operation in SSA |

|---|---|---|

| MTN Group [14] | 161.7 (2025) | South Africa, Nigeria, Ghana, Uganda, Rwanda, Zambia, South Sudan, Cameroon, Côte d’Ivoire, Benin, Guinea-Conakry, Congo-Brazzaville, Liberia, Guinea-Bissau, Sudan, Botswana, eSwatini |

| Airtel Africa [15] | 75.6 (2025) | Nigeria, Kenya, Malawi, Rwanda, Tanzania, Uganda, Zambia, Chad, DRC Congo, Gabon, Madagascar, Niger, Republic of the Congo, Seychelles. |

| Vodacom Group [16] | 63.218 (2025) | South Africa, DRC, Lesotho, Mozambique, Tanzania, Ethiopia, Kenya, |

| Orange Africa [17] | Not available | Cameroon, DRC, Senegal, Mali, Sierra Leone, Guinea, Guinea Bissau, Côte d’Ivoire, Burkina Faso, Liberia, Central African Republic, Madagascar, Botswana |

| Ethiopian Telecom [18] | 43.5 ( 2024) | Ethiopia |

| Country | Total Fixed Broadband Network | Cable Modem | FTTX | DSL | Others |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| South Africa [21] | 2,735,968 | - | 2,465,453 | 241,947 | 28,568 |

| Nigeria (2025) [22] | 75,884 | - | - | - | - |

| Kenya [23] | 1,718,679 | 188,541 | 1,066,972 | 137 | 958 |

| Angola [24] | 137,466 | - | - | - | - |

| Tanzania [25] | 84,674 | - | 83,201 | - | 1473 |

| Country | Major Satellite Internet Service Providers (Type of Satellite Used) | Number of Subscribers | Type of Subscribers |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nigeria [22] | Starlink (LEO), Eutelsat Konnect (GEO), Hyperia/YahClick (GEO), Phase3/YahClick (GEO) | 65,500 | Homes, small businesses, remote communities |

| South Africa [21] | Eutelsat Konnect (GEO), MorClick YahClick/Hughes (GEO), Paratus (GEO), SEACOM Satellite (GEO and LEO), Vox and Q-Kon (LEO, GEO) | 13,667 | Homes, small businesses, corporate and remote offices |

| Kenya [23] | Starlink (LEO), Eutelsat Konnect (GEO), NTvsat (GEO), Vizocom (GEO), GlobalTT/IPSEOS (GEO), Intersat Africa (GEO), | 19,403 | Homes and businesses in cities, SMEs, rural areas, industrial/government clients, NGOs, corporate, maritime. |

| Angola [24] | AngoSat 2 (GEO), Eutelsat Konnect (GEO), BusinessCom (GEO), | - | Homes, corporate institutions, NGO, maritime, educational and healthcare institutions |

| Tanzania [25] | Eutelsat Konnect (GEO), NTvsat (GEO), NTvsat (GEO), GlobalTT/OneWeb (GEO and LEO) | 1080 | Homes and small businesses, remote sites, enterprises, government, maritime, industry, NGOs |

| Satellite Type | VLEO | LEO | MEO | GEO |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Altitude (km) | 160–450 | 500–2000 | 2000–20,000 | ~35,786 |

| Visibility time with a minimum of 100 elevation (minutes) | 3.5–7 | 7–14 | 45–420 | 1440 |

| Round trip latency (ms) | 5–10 | 20–50 | 100–250 | 400–600 |

| Orbital period (hours) | ~1.5 | 1.5–2 | 2–12 | 24 |

| Handover requirement | very high | high | low | almost zero |

| Propagation loss | very low | low | medium | high |

| Energy consumption | very low | low | medium | high |

| Capacity scalability | very high | high | moderate | limited |

| Number of satellites required for global coverage | >80 | 40–80 | 5–40 | 3 |

| Network complexity | high | high | medium | low |

| Country (Data Cap) | Mini Package | Standard Package | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kit (USD) | Monthly Fee (USD) | Kit (USD) | Monthly Fee (USD) | |

| Nigeria | 207 | 37 | 385 | 37 |

| Zimbabwe | - | - | 389 | 50 |

| Zambia | 226 | 50 | 442 | 50 |

| Ghana | 303 | 73 | 568 | 73 |

| Kenya | 208 | 50 | 384 | 50 |

| Rwanda | 179 | 28 | 378 | 28 |

| Mozambique | 199 | 29 | 341 | 29 |

| Madagascar | 202 | 51 | 393 | 51 |

| Burundi | 194 | 33 | 367 | 33 |

| South Sudan | 200 | 50 | 389 | 50 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Falowo, O.; Falowo, S. Low Internet Penetration in Sub-Saharan Africa and the Role of LEO Satellites in Addressing the Issue. Telecom 2026, 7, 7. https://doi.org/10.3390/telecom7010007

Falowo O, Falowo S. Low Internet Penetration in Sub-Saharan Africa and the Role of LEO Satellites in Addressing the Issue. Telecom. 2026; 7(1):7. https://doi.org/10.3390/telecom7010007

Chicago/Turabian StyleFalowo, Olabisi, and Samuel Falowo. 2026. "Low Internet Penetration in Sub-Saharan Africa and the Role of LEO Satellites in Addressing the Issue" Telecom 7, no. 1: 7. https://doi.org/10.3390/telecom7010007

APA StyleFalowo, O., & Falowo, S. (2026). Low Internet Penetration in Sub-Saharan Africa and the Role of LEO Satellites in Addressing the Issue. Telecom, 7(1), 7. https://doi.org/10.3390/telecom7010007