Trends and Determinants of Dementia-Related Mortality in Mexico, 2017–2023

Abstract

1. Introduction

Study Aim and Hypotheses

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Statistical Analysis

2.3. Ethical Considerations

3. Results

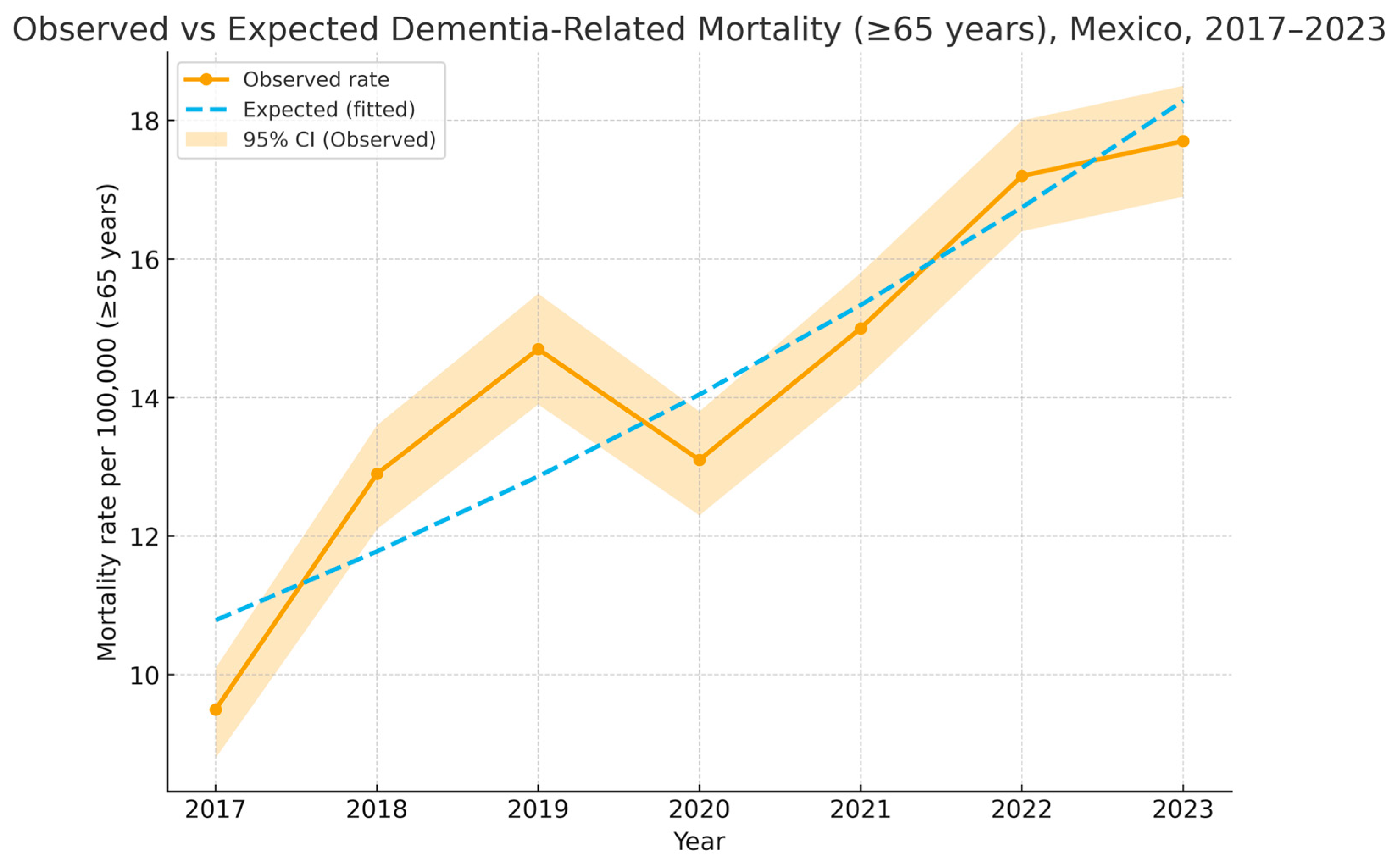

- Annual Trends in Dementia-Related Mortality (2017–2023)

- 2.

- Individual-Level Sociodemographic Associations

- 3.

- State-Clusters Analysis

4. Discussion

Limitation

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| HALE | Health-adjusted life expectancy |

| YLD | Years lived with disability |

| DALY | Disability-adjusted life-years |

| CONAPO | National Population Council |

| INEGI | National Institute of Geography and Statistics |

| OR | Odds ratios |

| CI | Confidence intervals |

References

- Prince, M.; Wimo, A.; Guerchet, M.; Ali, G.C.; Wu, Y.-T.; Prina, M. The World Alzheimer Report 2015: The Global Impact of Dementia; Alzheimer’s Disease International: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Mackenbach, J.P.; Looman, C.W.N. Life expectancy and national income in Europe, 1900–2008: An update of Preston’s analysis. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2013, 42, 1100–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marmot, M. Social determinants of health inequalities. Lancet 2005, 365, 1099–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salomon, J.A.; Wang, H.; Freeman, M.K.; Vos, T.; Flaxman, A.D.; Lopez, A.D.; Murray, C.J.L. Healthy life expectancy for 187 countries, 1990–2010: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden Disease Study 2010. Lancet 2012, 380, 2144–2162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathers, C.D.; Stevens, G.A.; Boerma, T.; White, R.A.; Tobias, M.I. Causes of international increases in older age life expectancy. Lancet 2015, 385, 540–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jagger, C.; Weston, C.; Cambois, E.; Van Oyen, H.; Nusselder, W.; Doblhammer, G.; Rychtarikova, J.; Robine, J.M.; The EHLEIS Team. Inequalities in health expectancies at older ages in the European Union: Findings from the Survey of Health and Retirement in Europe (SHARE). J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2011, 65, 1030–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yong, V.; Saito, Y. Trends in healthy life expectancy in Japan: 1986–2004. Demogr. Res. 2009, 20, 467–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, X.; Jia, W.; Zhou, J.; Xu, Y.; Zou, J.; Liu, M.; Jiang, S.; Li, X. Changes and trends in mortality, disability-adjusted life years, life expectancy, and healthy life expectancy in China from 1990 to 2021: A secondary analysis of the Global Burden of Disease 2021. Arch. Public Health 2025, 83, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyes-Beaman, S.; Jagger, C.; García-Peña, C.; Muñoz, O.; Beaman, P.E.; Stafford, B.; National Group of Research on Ageing. Active life expectancy of older people in Mexico. Disabil. Rehabil. 2005, 27, 213–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Payne, C.F.; Wong, R. Expansion of disability across successive Mexican birth cohorts: A longitudinal modeling analysis of birth cohorts born ten years apart. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2019, 73, 900–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, R.; Michaels-Obregón, A.; Palloni, A. Cohort profile: The Mexican Health and Aging Study (MHAS). Int. J. Epidemiol. 2017, 46, e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doubova Dubova, S.V.; Pérez-Cuevas, R.; Espinosa-Alarcón, P.; Flores-Hernández, S. Social network types and functional dependency in older adults in Mexico. BMC Public Health 2010, 10, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angel, J.L.; Vega, W.; López-Ortega, M. Aging in Mexico: Population trends and emerging issues. Gerontologist 2017, 57, 153–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Armenta-Paulino, N.; Wehrmeister, F.C.; Arroyave, L.; Barros, A.J.D.; Victora, C.G. Ethnic inequalities in health intervention coverage among Mexican women at the individual and municipality levels. EClinicalMedicine 2021, 36, 101228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortés-Adame, L.J.; Gómez-Dantés, O. The termination of Seguro Popular: Impacts on the care of high-cost diseases in the uninsured population in Mexico. Lancet Reg. Health Am. 2025, 46, 101078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Nuñez, J.; Domínguez, S.; Zimmermann, K.J. Characterizing uninsured population in Mexico: A multinomial analysis. Rev. Behav. Financ. 2025, 17, 83–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvarez-Aceves, M.; Palacio-Mejía, L.S.; Hernández-Ávila, M.; González-González, E.L.; Castro-Del Ángel, C.A.; Guzmán-Sandoval, L.; Hernández-Ávila, J.E. 23 years of public policy towards universal health coverage in Mexico. A cross-sectional time-series analysis using routinely collected health data, 2000–2022. Lancet Reg. Health Am. 2025, 52, 101271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Consejo Nacional de Población (CONAPO). Proyecciones de la Población de México y de las Entidades Federativas 2016–2050; CONAPO: Ciudad de México, México, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Janssen-Aguilar, R.; Erosa-Villarreal, R.A.; González-Maldonado, L.A.; Méndez-Domínguez, N.I.; Inurreta-Díaz, M.J. Epidemiological characteristics of dementia-related mortality in Mexico between 2012 and 2016. Rev. Mex. Neurocienc. 2019, 20, 222–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murata, S.; Takegami, M.; Onozuka, D.; Nakaoku, Y.; Hagihara, A.; Nishimura, K. Incidence and mortality of dementia-related missing and their associated factors: An ecological study in Japan. J. Epidemiol. 2021, 31, 361–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.; Yang, N.; He, L.; Wang, J.; Yang, Y.; Ping, F.; Xu, L.; Zhang, H.; Li, W.; Li, Y. Global burden of dementia death from 1990 to 2019, with projections to 2050: An analysis of 2019 Global Burden of Disease Study. J. Prev. Alzheimers Dis. 2024, 11, 1013–1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stephan, B.C.M.; Birdi, R.; Tang, E.Y.H.; Cosco, T.D.; Donini, L.M.; Licher, S.; Ikram, M.A.; Siervo, M.; Robinson, L. Secular trends in dementia prevalence and incidence worldwide: A systematic review. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2018, 66, 653–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirayesh, Z.; Riahi, S.M.; Bidokhti, A.; Kazemi, T. Evaluation of the effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on all-cause and cause-specific mortality, YLL, and life expectancy in the first two years in an Iranian population: An ecological study. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1259202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, K.; Stewart, S.T.; Raghunathan, T.; Cutler, D.M. Medical visits and mortality among dementia patients during the COVID-19 pandemic compared to rates predicted from 2019. BMC Geriatr. 2024, 24, 727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, R.; Charpignon, M.L.; Raquib, R.V.; Wang, J.; Meza, E.; Aschmann, H.E.; DeVost, M.A.; Mooney, A.; Bibbins-Domingo, K.; Riley, A.R.; et al. Excess mortality with Alzheimer disease and related dementias during the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States. JAMA Neurol. 2023, 80, 919–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barría-Sandoval, C.; Ferreira, G.; Navarrete, J.P.; Farhang, M. The impact of COVID-19 on deaths from dementia and Alzheimer’s disease in Chile: An analysis of panel data for 16 regions, 2017–2022. Lancet Reg. Health Am. 2024, 2, 100726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero, J.P.; Benito-León, J.; Mitchell, A.J.; Trincado, R.; Bermejo-Pareja, F. Underreporting of dementia deaths on death certificates using data from a population-based study (NEDICES). J. Alzheimers Dis. 2014, 39, 741–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morros-Serra, M.; Melendo-Azuela, E.M.; Garre-Olmo, J.; Turró-Garriga, O.; Santaeugènia, S. Sex differences in dementia diagnosis: A fourteen-year retrospective analysis using the Registry of Dementia of Girona. J. Women Aging 2025, 37, 72–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Global Status Report on the Public Health Response to Dementia; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Wimo, A.; Guerchet, M.; Ali, G.C.; Wu, Y.-T.; Prina, A.M.; Winblad, B.; Jönsson, L.; Liu, Z.; Prince, M. The worldwide costs of dementia 2015 and comparisons with 2010. Alzheimers Dement. 2017, 13, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spijker, J.J.; Calazans, J.A.; Trias-Llimós, S.; Renteria, E.; Doblhammer, G. Educational inequalities in dementia-related mortality and their contribution to life expectancy differences in Spain. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 26838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giebel, C.; Readman, M.R.; Godfrey, A.; Gray, A.; Carton, J.; Polden, M. Geographical inequalities in dementia diagnosis and care: A systematic review. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2025, 37, 100051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Souza-Talarico, J.N.; de Carvalho, A.P.; Brucki, S.M.; Nitrini, R.; Ferretti-Rebustini, R.E. Dementia and cognitive impairment prevalence and associated factors in Indigenous populations: A systematic review. Alzheimer Dis. Assoc. Disord. 2016, 30, 281–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshikawa, M.; Goto, E.; Shin, J.H.; Imanaka, Y. Regional disparities in dementia-free life expectancy in Japan: An ecological study using the long-term care insurance claims database. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0280299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolters, F.J.; Tinga, L.M.; Dhana, K.; Koudstaal, P.J.; Hofman, A.; Bos, D.; Franco, O.H.; Ikram, M.A. Life expectancy with and without dementia: A population-based study of dementia burden and preventive potential. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2019, 188, 372–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murray, C.J.L.; Lopez, A.D. Global mortality, disability, and the contribution of risk factors: Global Burden of Disease Study. Lancet 1997, 349, 1436–1442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- González Block, M.A.; Reyes Morales, H.; Cahuana Hurtado, L.; Balandrán, A.; Hernández, E.M.; Allin, S. Health Systems in Transition: Mexico; University of Toronto Press: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Alcalde-Rabanal, J.E.; Molina-Rodríguez, J.F.; Díaz-Portillo, S.P.; Hoyos-Loya, E.; Reyes-Morales, H. El sistema de salud de México: Análisis de sus logros y desafíos en el periodo 2015–2022. Salud Publica Mex. 2024, 66, 677–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waller, M.; Buckley, R.F.; Masters, C.L.; Nona, F.R.; Eades, S.J.; Dobson, A.J. Deaths with dementia in Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians: A nationwide study. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2021, 81, 1589–1599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Year Studied | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency | 761 | 1035 | 1184 | 1052 | 1211 | 1383 | 1425 |

| Age (Mean, SD) | 85.4 (7.8) | 85.6 (7.7) | 85.3 (7.6) | 85.7 (7.5) | 84.8 (7.5) | 85.4 (7.8) | 85.7 (7.6) |

| Male (%) | 317 (41.8) | 411 (39.9) | 467 (39.8) | 425 (40.4) | 458 (37.7) | 506 (36.9) | 567 (40.0) |

| Indigenous ethnicity (%) | 51 (6.7) | 77 (7.3) | 76 (6.4) | 58 (5.5) | 141 (13.3) | 81 (5.8) | 81 (5.7) |

| ≥Elementary education (%) | 100 (13.1) | 149 (14.4) | 171 (14.4) | 176 (16.7) | 192 (15.8) | 240 (17.3) | 279 (19.4) |

| Economically active (%) | 192 (25.2) | 349 (33.4) | 264 (22.2) | 237 (22.5) | 270 (22.1) | 284 (20.5) | 307 (21.5) |

| Residence < 500 k people (%) | 463 (60.7) | 608(58.4) | 687 (57.7) | 651 (61.8) | 714 (58.9) | 814 (58.6) | 797 (55.6) |

| Cohabiting with spouse (%) | 222 (29) | 309 (29.8) | 351 (29.6) | 300 (28.5) | 343 (28.4) | 364 (26.3) | 387 (26.9) |

| Medical insurance (%) | 646 (85.0) | 883 (85.5) | 992 (83.8) | 798 (75.9) | 847 (70.0) | 933 (67.8) | 977 (68.8) |

| Sociodemographic Characteristic | Odds Ratio | z | p-Value | 95% Confidence Interval | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | ||||

| Age (numeric, per year) | 1.00 | 0.08 | 0.934 | 0.99 | 1.00 |

| 65–79 years | 0.89 | −2.07 | 0.038 | 0.80 | 0.99 |

| 80–99 years | 1.11 | 2.07 | 0.039 | 1.00 | 1.32 |

| ≥100 years | 0.97 | −0.18 | 0.859 | 0.71 | 1.32 |

| Gender (Male) | 0.78 | −5.33 | <0.001 | 0.71 | 0.85 |

| Economically active | 0.62 | −8.41 | <0.001 | 0.56 | 0.70 |

| High school or higher | 1.91 | 10.69 | <0.001 | 1.70 | 2.16 |

| Cohabiting with a spouse | 0.99 | -0.10 | 0.919 | 0.90 | 1.09 |

| Medical insurance covers | 2.22 | 14.13 | 0.001 | 1.98 | 2.48 |

| Indigenous ethnicity | 0.17 | −13.29 | <0.001 | 0.13 | 0.22 |

| State/Cluster Characteristic | Coefficient | p-Value | 95% Confidence Intervals | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | |||

| Life expectancy at birth | 2.49 | 0.003 | 0.94 | 4.05 |

| Population aging | −0.21 | 0.016 | −0.38 | −0.04 |

| Medical Insurance Coverage | 0.02 | 0.877 | −0.29 | 0.34 |

| Pseudo R2 = 0.42 | Post hoc = 0.95 | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Lopez-Samayoa, D.M.; Campos-Sosa, A.M.; Bojorquez-Chan, P.A.; Martinez-Medel, S.E.; Guillermo-Herrera, J.C.; Villarreal-Jimenez, E.; Janssen-Aguilar, R.; Peres-Mitre, C.R.; Mendez-Dominguez, N. Trends and Determinants of Dementia-Related Mortality in Mexico, 2017–2023. Epidemiologia 2026, 7, 14. https://doi.org/10.3390/epidemiologia7010014

Lopez-Samayoa DM, Campos-Sosa AM, Bojorquez-Chan PA, Martinez-Medel SE, Guillermo-Herrera JC, Villarreal-Jimenez E, Janssen-Aguilar R, Peres-Mitre CR, Mendez-Dominguez N. Trends and Determinants of Dementia-Related Mortality in Mexico, 2017–2023. Epidemiologia. 2026; 7(1):14. https://doi.org/10.3390/epidemiologia7010014

Chicago/Turabian StyleLopez-Samayoa, Dennis M., Angel M. Campos-Sosa, Paola Asuncion Bojorquez-Chan, Sara E. Martinez-Medel, Jorge C. Guillermo-Herrera, Edgar Villarreal-Jimenez, Reinhard Janssen-Aguilar, Cristina Rodriguez Peres-Mitre, and Nina Mendez-Dominguez. 2026. "Trends and Determinants of Dementia-Related Mortality in Mexico, 2017–2023" Epidemiologia 7, no. 1: 14. https://doi.org/10.3390/epidemiologia7010014

APA StyleLopez-Samayoa, D. M., Campos-Sosa, A. M., Bojorquez-Chan, P. A., Martinez-Medel, S. E., Guillermo-Herrera, J. C., Villarreal-Jimenez, E., Janssen-Aguilar, R., Peres-Mitre, C. R., & Mendez-Dominguez, N. (2026). Trends and Determinants of Dementia-Related Mortality in Mexico, 2017–2023. Epidemiologia, 7(1), 14. https://doi.org/10.3390/epidemiologia7010014