Spina Bifida Incidence Trends: A Comparative Study of Puerto Rico and the United States

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

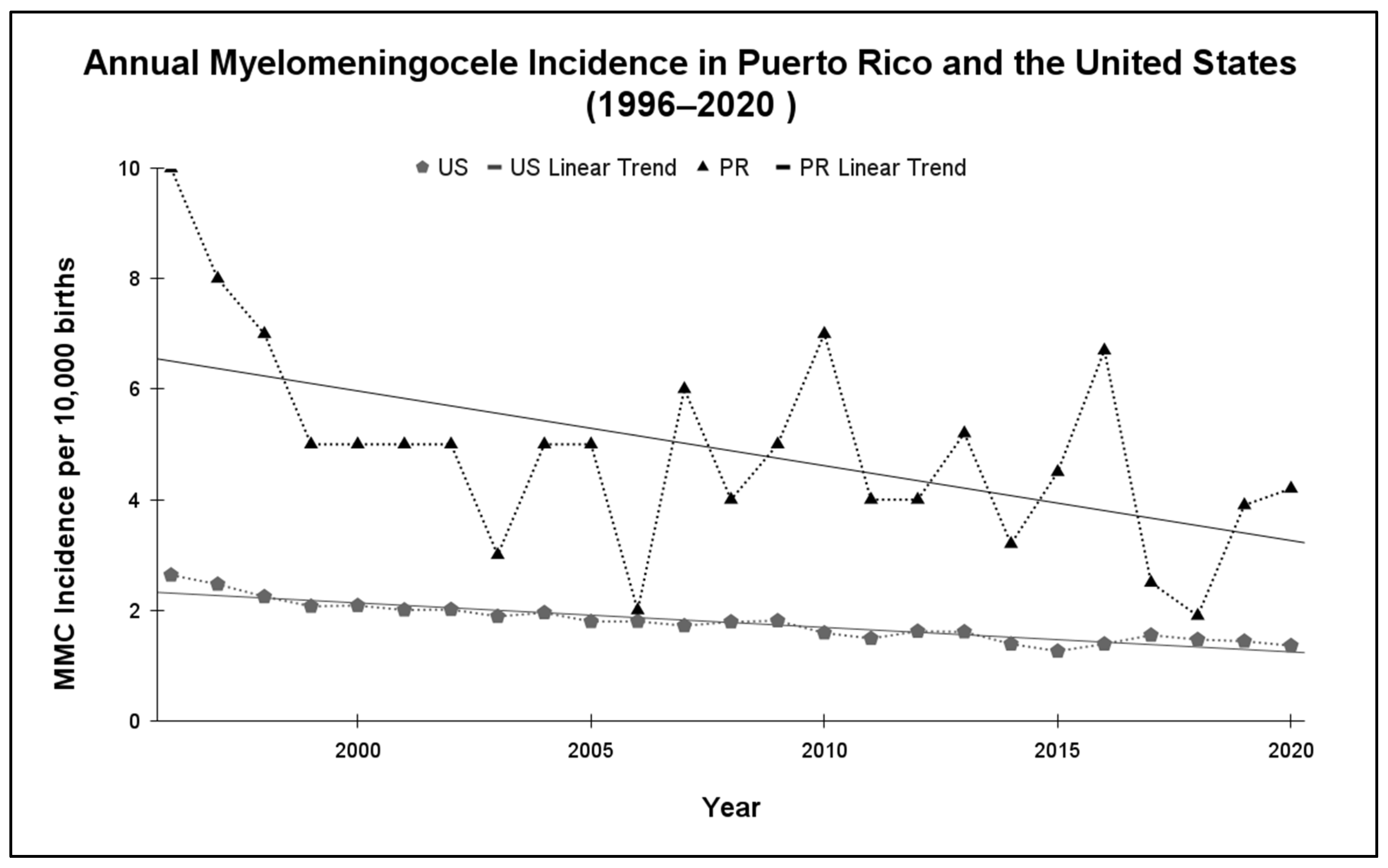

3.1. Myelomeningocele Incidence

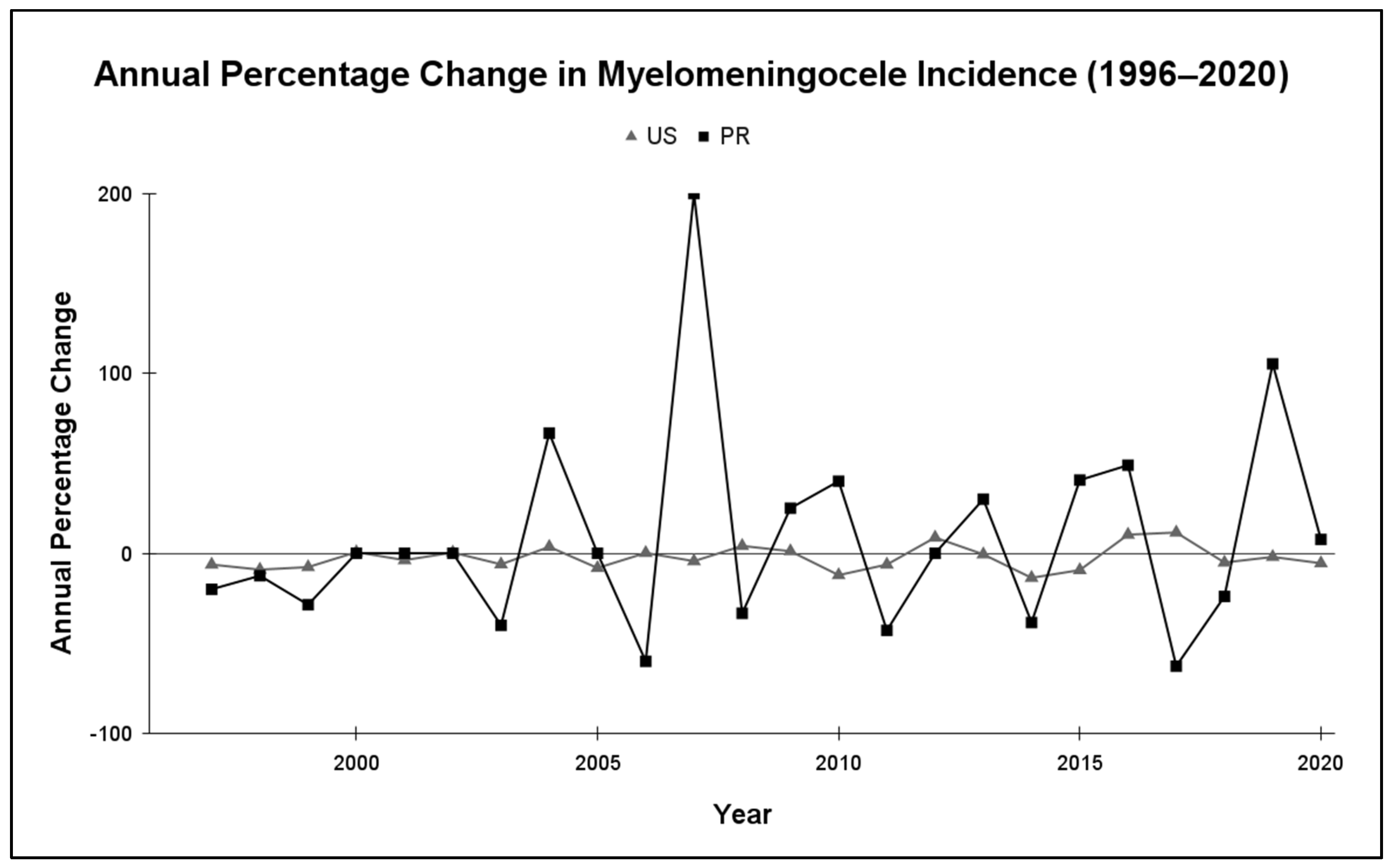

3.2. Myelomeningocele Annual Variability

3.3. 1999–2020 Subgroup Analysis

4. Discussion

4.1. Genetic Susceptibility: MTHFR C6677T Variant and NTDs

4.2. Maternal Substance Use: Alcohol and Tobacco

4.3. Maternal Metabolic Factors: Obesity, Diabetes, and Risk of MMC

4.4. Folic Acid

4.5. Sexual Education

4.6. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MMC | Myelomeningocele |

| PR | Puerto Rico |

| US | United States |

| SD | Standard Deviation |

| CI | Confidence Interval |

| NTD | Neural Tube Defect |

| APC | Annual Percent Change |

| MTHFR | 5,10-Methyltetrahydrofolate Reductase |

| PRASM | USA Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System |

| BRFSS | Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance Systems |

| DM | Diabetes Mellitus |

| GDM | Gestational Diabetes Mellitus |

| NHANES | National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey |

| USPSTF | United States Preventive Services Taskforce |

References

- Schindelmann, K.H.; Paschereit, F.; Steege, A.; Stoltenburg-Didinger, G.; Kaindl, A.M. Systematic Classification of Spina Bifida. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 2021, 80, 294–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Copp, A.J.; Adzick, N.S.; Chitty, L.S.; Fletcher, J.M.; Holmbeck, G.N.; Shaw, G.M. Spina bifida. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2015, 1, 15007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, D.; Rath, G.P.; Dash, H.H.; Bithal, P.K. Anesthetic concerns and perioperative complications in repair of myelomeningocele: A retrospective review of 135 cases. J. Neurosurg. Anesthesiol. 2010, 22, 11–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cavalheiro, S.; da Costa, M.D.S.; Barbosa, M.M.; Dastoli, P.A.; Mendonça, J.N.; Cavalheiro, D.; Moron, A.F. Hydrocephalus in myelomeningocele. Child’s Nerv. Syst. 2021, 37, 3407–3415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talamonti, G.; D’Aliberti, G.; Collice, M. Myelomeningocele: Long-term neurosurgical treatment and follow-up in 202 patients. J. Neurosurg. 2007, 107, 368–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cass, A.S. Urinary tract complications in myelomeningocele patients. J. Urol. 1976, 115, 102–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santiago-Lastra, Y.; Cameron, A.P.; Lai, J.; Saigal, C.; Clemens, J.Q.; Urologic Diseases of America Project. Urological Surveillance and Medical Complications in the United States Adult Spina Bifida Population. Urology 2019, 123, 287–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anegbe, A.O.; Shokunbi, M.T.; Oyemolade, T.A.; Badejo, O.A. Intracranial infection in patients with myelomeningocele: Profile and risk factors. Child’s Nerv. Syst. 2019, 35, 2205–2210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valença, M.P.; de Menezes, T.A.; Calado, A.A.; de Aguiar Cavalcanti, G. Burden and quality of life among caregivers of children and adolescents with meningomyelocele: Measuring the relationship to anxiety and depression. Spinal Cord 2012, 50, 553–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayri, Y.; Soylemez, B.; Seker, A.; Yuksel, S.; Tanrikulu, B.; Unver, O.; Canbolat, C.; Sakar, M.; Kardag, O.; Yakicier, C.; et al. Neural tube defect family with recessive trait linked to chromosome 9q21.12-21.31. Child’s Nerv. Syst. 2015, 31, 1367–1370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vong, K.I.; Lee, S.; Au, K.S.; Crowley, T.B.; Capra, V.; Martino, J.; Haller, M.; Araújo, C.; Machado, H.R.; George, R.; et al. Risk of meningomyelocele mediated by the common 22q11.2 deletion. Science 2024, 384, 584–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donnan, J.; Walsh, S.; Sikora, L.; Morrissey, A.; Collins, K.; MacDonald, D. A systematic review of the risk factors associated with the onset and natural progression of spina bifida. Neurotoxicology 2017, 61, 20–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iskandar, B.J.; Finnell, R.H. Spina Bifida. N. Engl. J. Med. 2022, 387, 444–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van der Windt, M.; Schoenmakers, S.; van Rijn, B.; Galjaard, S.; Steegers-Theunissen, R.; van Rossem, L. Epidemiology and (Patho)Physiology of Folic Acid Supplement Use in Obese Women before and during Pregnancy. Nutrients 2021, 13, 331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Au, K.S.; Hebert, L.; Hillman, P.; Baker, C.; Brown, M.R.; Kim, D.K.; Soldano, K.; Garrett, M.; Ashley-Koch, A.; Lee, S.; et al. Human myelomeningocele risk and ultra-rare deleterious variants in genes associated with cilium, WNT-signaling, ECM, cytoskeleton and cell migration. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 3639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kancherla, V.; Ibne Hasan, M.O.S.; Hamid, R.; Paul, L.; Selhub, J.; Oakley, G.; Quamruzzaman, Q.; Mazumdar, M. Prenatal folic acid use associated with decreased risk of myelomeningocele: A case-control study offers further support for folic acid fortification in Bangladesh. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0188726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atta, C.A.M.; Fiest, K.M.; Frolkis, A.D.; Jette, N.; Pringsheim, T.; St Germaine-Smith, C.; Rajapakse, T.; Kaplan, G.G.; Metcalfe, A. Global Birth Prevalence of Spina Bifida by Folic Acid Fortification Status: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Am. J. Public Health 2016, 106, e24–e34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puerto Rico Department of Health. Defectos Congénitos en Puerto Rico, 2016–2020: Sistema de Vigilancia y Prevención de Defectos Congénitos de Puerto Rico; Puerto Rico Institute of Statistics: San Juan, Puerto Rico, 2021; Available online: https://estadisticas.pr/files/Inventario/publicaciones/defectos%20congenitos%202016-2020.pdf (accessed on 21 January 2025).

- Food and Drug Administration. Food standards: Amendment of standards of identity for enriched grain products to require addition of folic acid. Fed. Regist. 1996, 61, 8781–8797. [Google Scholar]

- van der Put, N.M.; Blom, H.J. Neural tube defects and a disturbed folate dependent homocysteine metabolism. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2000, 92, 57–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Fragoso, L.; García-García, I.; de la Vega, A.; Renta, J.; Cadilla, C.L. Presence of the 5,10-methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase C677T mutation in Puerto Rican patients with neural tube defects. J. Child Neurol. 2002, 17, 30–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dean, L. Methylenetetrahydrofolate Reductase Deficiency. In Medical Genetics Summaries; Pratt, V.M., Scott, S.A., Pirmohamed, M., Esquivel, B., Kattman, B.L., Malheiro, A.J., Eds.; National Center for Biotechnology Information (US): Bethesda, MD, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, M.; Wang, Z.P.; Gong, R.; Zhao, Z.T. Maternal smoking during pregnancy and neural tube defects in offspring: A meta-analysis. Child’s Nerv. Syst. 2014, 30, 83–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steane, S.E.; Cuffe, J.S.M.; Moritz, K.M. The role of maternal choline, folate and one-carbon metabolism in mediating the impact of prenatal alcohol exposure on placental and fetal development. J. Physiol. 2023, 601, 1061–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kipling, L.; Bombard, J.; Wang, X.; Cox, S. Cigarette Smoking Among Pregnant Women During the Perinatal Period: Prevalence and Health Care Provider Inquiries—Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System, United States, 2021. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2024, 73, 393–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gosdin, L.K.; Deputy, N.P.; Kim, S.Y.; Dang, E.P.; Denny, C.H. Alcohol Consumption and Binge Drinking During Pregnancy Among Adults Aged 18-49 Years—United States, 2018–2020. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2022, 71, 10–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Administración de Servicios de Salud Mental y Contra la Adicción. Trastornos de Substancias y Uso de Servicios en Puerto Rico: Encuesta de Hogares—2008 (Informe Final). 2009. Available online: https://www.assmca.pr.gov/documentos#Biblioteca-Virtua (accessed on 3 July 2025).

- Puerto Rico Department of Health. Puerto Rico Health Needs Assessment Update 2023. Maternal, Child and Adolescent Health Program & Children with Special Health Care Needs Program. July 2023. Available online: https://www.salud.pr.gov/CMS/396 (accessed on 7 July 2025).

- Anderson, J.L.; Waller, D.K.; Canfield, M.A.; Shaw, G.M.; Watkins, M.L.; Werler, M.M. Maternal obesity, gestational diabetes, and central nervous system birth defects. Epidemiology 2005, 16, 87–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, W.; Ji, Y.; Dong, Z.; Liu, Z.; Chen, S.; Dai, L.; Su, X.; Jiang, Q.; Deng, H. Characterizing neuroinflammation and identifying prenatal diagnostic markers for neural tube defects through integrated multi-omics analysis. J. Transl. Med. 2024, 22, 257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, P.; Li, X.; Xu, C.; Eckert, R.L.; Reece, E.A.; Zielke, H.R.; Wang, F. Maternal hyperglycemia activates an ASK1-FoxO3a-caspase 8 pathway that leads to embryonic neural tube defects. Sci. Signal. 2013, 6, ra74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- US Preventive Services Task Force; Barry, M.J.; Nicholson, W.K.; Silverstein, M.; Chelmow, D.; Coker, T.R.; Davis, E.M.; Donahue, K.E.; Jaén, C.R.; Li, L.; et al. Folic Acid Supplementation to Prevent Neural Tube Defects: US Preventive Services Task Force Reaffirmation Recommendation Statement. JAMA 2023, 330, 454–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaer, C.M.; Chescheir, N.; Schulkin, J. Myelomeningocele: A review of the epidemiology, genetics, risk factors for conception, prenatal diagnosis, and prognosis for affected individuals. Obstet. Gynecol. Surv. 2007, 62, 471–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Liu, B.; Sun, Y.; Du, Y.; Santillan, M.K.; Santillan, D.A.; Snetselaar, L.G.; Bao, W. Association of Maternal Prepregnancy Diabetes and Gestational Diabetes Mellitus With Congenital Anomalies of the Newborn. Diabetes Care 2020, 43, 2983–2990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado-Astacio, S.; Tremblay, R.L.; Colón-Díaz, M. Prevalence of Gestational Diabetes Mellitus in Puerto Rico: A Study from 2016 to 2021. J. Diabetes Mellit. 2024, 14, 194–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, N.S.; Wang, M.C.; Freaney, P.M.; Perak, A.M.; Carnethon, M.R.; Kandula, N.R.; Gunderson, E.P.; Bullard, K.M.; Grobman, W.A.; O’Brien, M.J.; et al. Trends in Gestational Diabetes at First Live Birth by Race and Ethnicity in the US, 2011–2019. JAMA 2021, 326, 660–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eick, S.M.; Welton, M.; Claridy, M.D.; Velasquez, S.G.; Mallis, N.; Cordero, J.F. Associations between gestational weight gain and preterm birth in Puerto Rico. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2020, 20, 599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seyoum Tola, F. The concept of folic acid supplementation and its role in prevention of neural tube defect among pregnant women: PRISMA. Medicine 2024, 103, e38154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García-Fragoso, L.; García-García, I.; Rivera, C.E. The use of folic acid for the prevention of birth defects in Puerto Rico. Ethn. Dis. 2008, 18 (Suppl. S2), S2-168-71. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Trends in folic acid supplement intake among women of reproductive age—California, 2002–2006. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2007, 56, 1106–1109. [Google Scholar]

- Jun, S.; Gahche, J.J.; Potischman, N.; Dwyer, J.T.; Guenther, P.M.; Sauder, K.A.; Bailey, R.L. Dietary Supplement Use and Its Micronutrient Contribution During Pregnancy and Lactation in the United States. Obstet. Gynecol. 2020, 135, 623–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkins, D.N.; Bradford, W.D. The Effect of State-Level Sex Education Policies on Youth Sexual Behaviors. Arch. Sex. Behav. 2021, 50, 2321–2333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanger-Hall, K.F.; Hall, D.W. Abstinence-only education and teen pregnancy rates: Why we need comprehensive sex education in the U.S. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e24658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pérez-Pérez, E.; Rivera-Rivera, E.; Frontera, N.; Cedeño-Moran, A.; Carvajal-Matta, C.; González, J.; de Jesús-Espinosa, A.; Sosa-González, I.; Mayol del Valle, M. Spina Bifida Incidence Trends: A Comparative Study of Puerto Rico and the United States. Epidemiologia 2025, 6, 92. https://doi.org/10.3390/epidemiologia6040092

Pérez-Pérez E, Rivera-Rivera E, Frontera N, Cedeño-Moran A, Carvajal-Matta C, González J, de Jesús-Espinosa A, Sosa-González I, Mayol del Valle M. Spina Bifida Incidence Trends: A Comparative Study of Puerto Rico and the United States. Epidemiologia. 2025; 6(4):92. https://doi.org/10.3390/epidemiologia6040092

Chicago/Turabian StylePérez-Pérez, Eric, Esteban Rivera-Rivera, Natasha Frontera, Alejandro Cedeño-Moran, Camelia Carvajal-Matta, Jeremy González, Aixa de Jesús-Espinosa, Iván Sosa-González, and Miguel Mayol del Valle. 2025. "Spina Bifida Incidence Trends: A Comparative Study of Puerto Rico and the United States" Epidemiologia 6, no. 4: 92. https://doi.org/10.3390/epidemiologia6040092

APA StylePérez-Pérez, E., Rivera-Rivera, E., Frontera, N., Cedeño-Moran, A., Carvajal-Matta, C., González, J., de Jesús-Espinosa, A., Sosa-González, I., & Mayol del Valle, M. (2025). Spina Bifida Incidence Trends: A Comparative Study of Puerto Rico and the United States. Epidemiologia, 6(4), 92. https://doi.org/10.3390/epidemiologia6040092