Oral Health Assessment in Prisoners: A Cross-Sectional Observational and Epidemiological Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Characteristics of the Study

2.2. Samples and Groups

2.3. Data Collection

2.4. Statistical Analysis

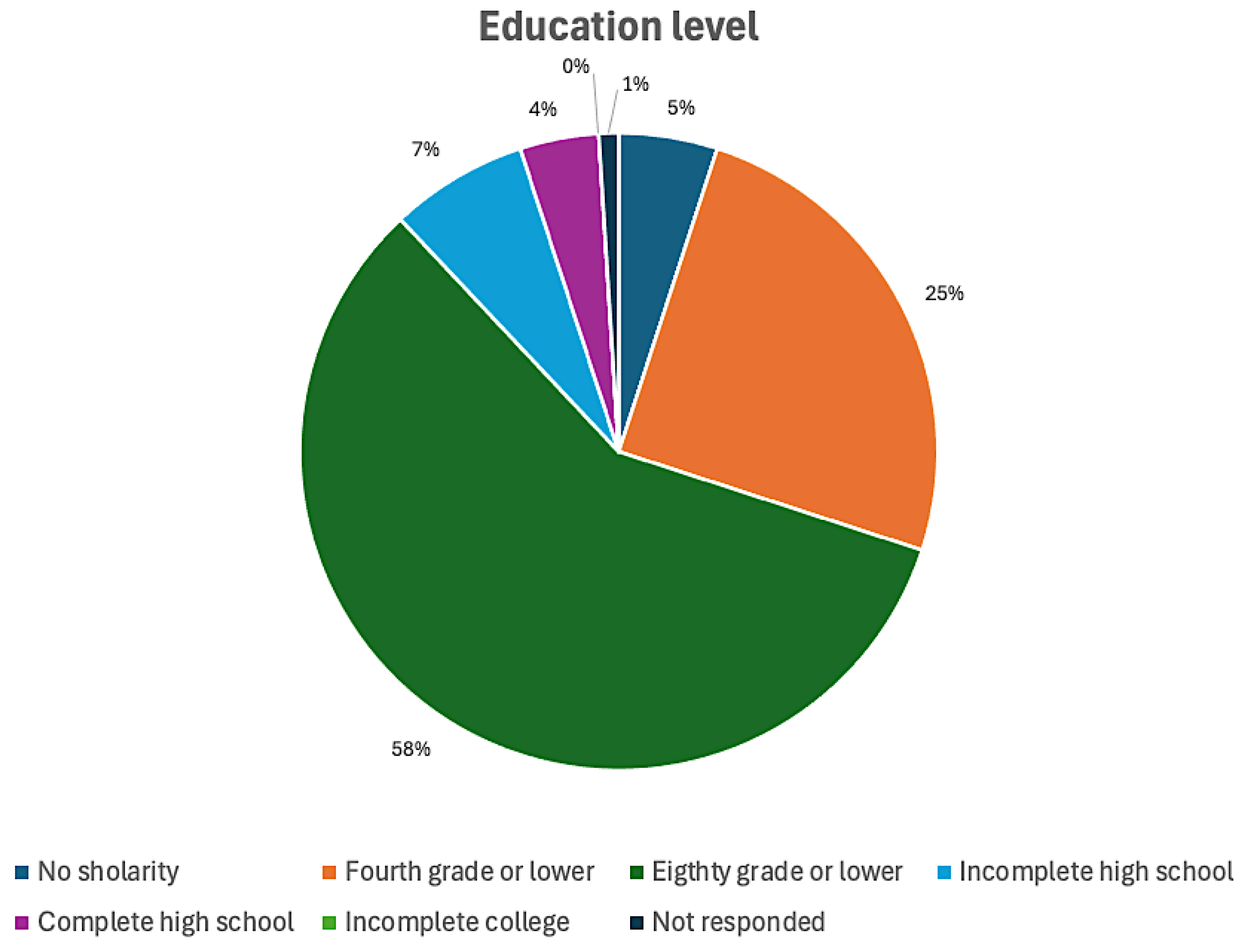

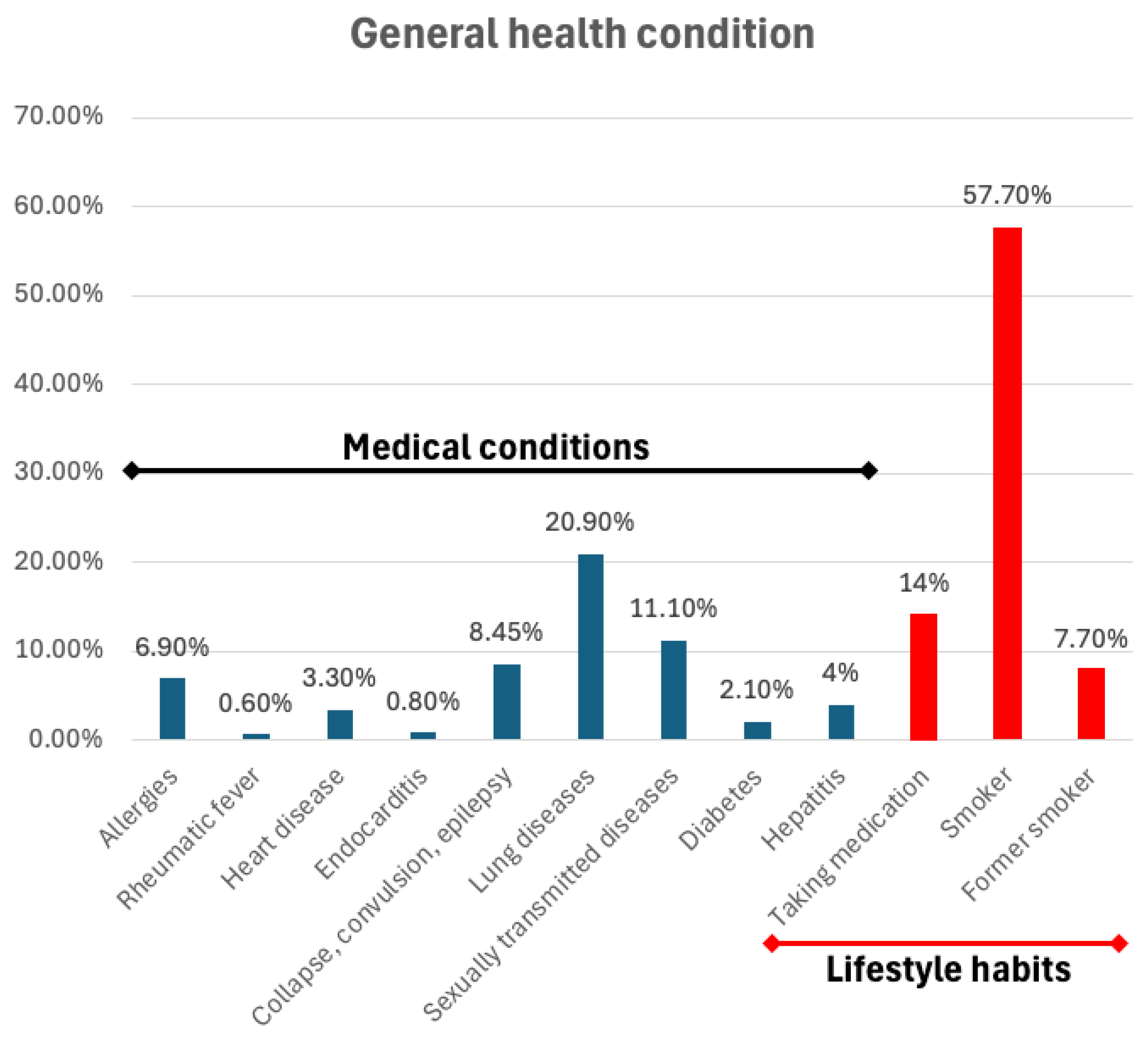

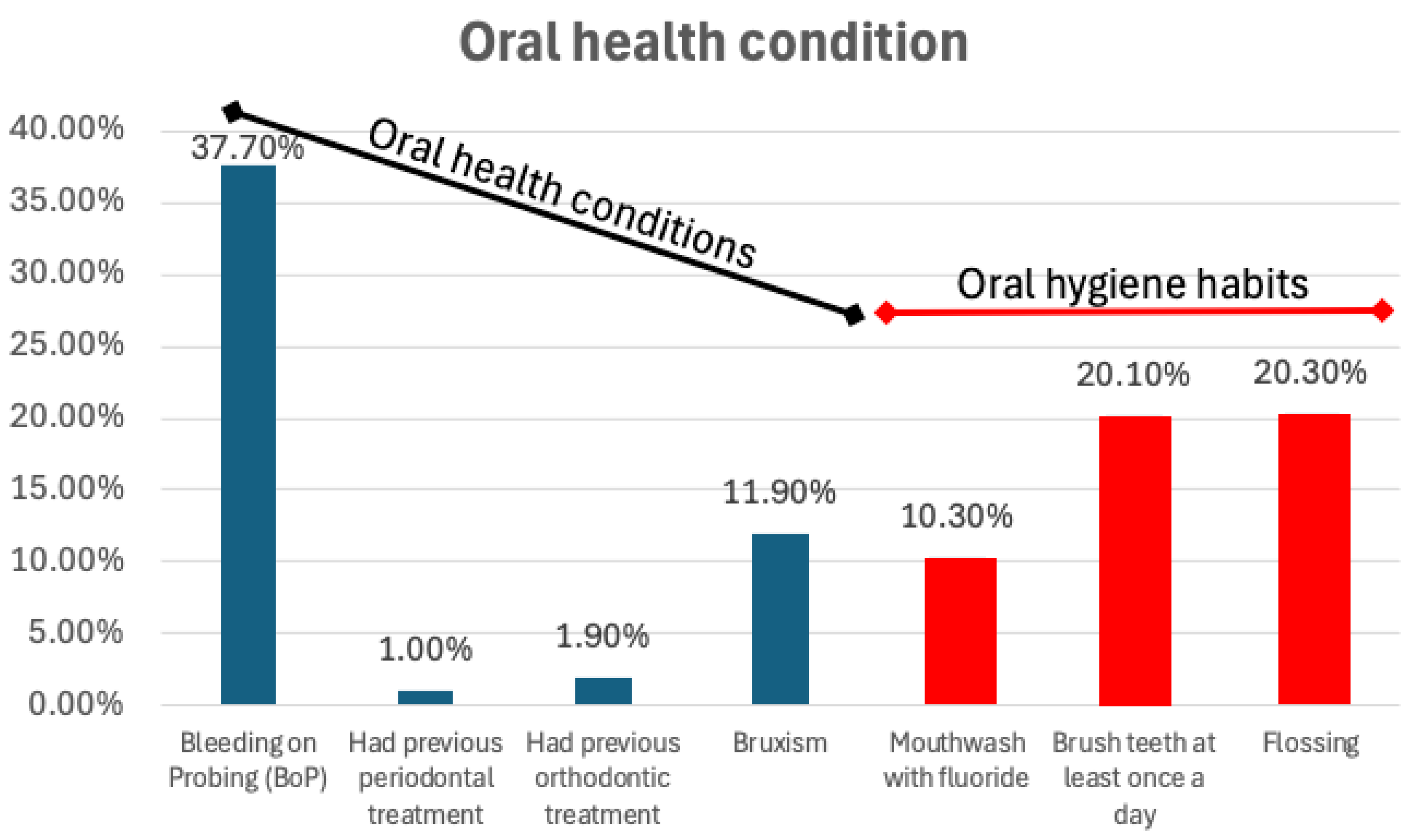

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Limitations of Oral Health Epidemiology in Adults and Inmates

4.2. Oral Health Studies in Specific Populations

4.3. Sociodemographic and Health Characteristics and Findings, and DMFT Trends

4.4. Influence of Institutional Diet on Oral and Systemic Health

4.5. Impact of Alcohol and Drug Use on Oral Health

4.6. Comparative Studies on Prisoners’ Oral Health Worldwide

4.7. Parallels with Military Populations

4.8. The Role of Education and Professional-Patient Interaction

4.9. Limitations of the Study and Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Locker, D. Oral health and quality of life. Oral Health Prev. Dent. 2004, 2, 247–253. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ribeiro, I.S.S.; Almeida, J.S.; Iglesias, J.E.; Kaizer, M.; Fernandes, J.C.H.; Inchingolo, A.M.; Dipalma, G.; Fernandes, G.V.O.; Resende, R.F.B. Herpetic Lesions Affecting the Oral Cavity-Etiology, Diagnosis, Medication, and Laser Therapy: A Literature Review. J. Basic Clin. Dent. 2025, 2, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veiga, N.; Figueiredo, R.; Correia, P.; Lopes, P.; Couto, P.; Fernandes, G.V.O. Methods of Primary Clinical Prevention of Dental Caries in the Adult Patient: An Integrative Review. Healthcare 2023, 11, 1635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, J.P.; Knupp, R.R.S. Avaliação do conhecimento dos obstetras sobre saúde oral na atenção materno-infantil. Rev. Braz. Odontol. 2000, 57, 317–320. [Google Scholar]

- Scambler, S.; Gupta, A.; Asimakopoulou, K. Patient-centred care—What is it and how is it practised in the dental surgery? Health Expect. 2014, 18, 2549–2558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petry, P.C.; Pretto, S.M. Education and Motivation in Oral Health. In ABOPREV: Promoção de Saúde Bucal, 2nd ed.; Kriger, L., Ed.; Artes Médicas: Porto Alegre, Brazil, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Schlegel, R.; Vazquez, D.A. Coercion in Disguise? A Reassessment of Brazilian Education and Health Reforms. J. Politics Latin Am. 2021, 13, 243–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, G.V.d.O.; Fernandes, J.C.H. Revisiting and rethinking on staging (severity and complexity) periodontitis from the new classification system: A critical review with suggestions for adjustments and a proposal of a new flowchart. Dent. Med. Probl. 2025, 62, 371–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doceda, M.V.; Petit, C.; Huck, O. Behavioral interventions on periodontitis patients to improve oral hygiene: A systematic review. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 2276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inglehart, M.R. Motivational Communication in Dental Practices: Prevention and Management of Caries over the Life Course. Dent. Clin. N. Am. 2019, 63, 517–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Issáo, M.; Guedes-Pinto, A.C. Manual de Odontopediatria, 8th ed.; Artes Médicas: Porto Alegre, Brazil, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Moore, R. Trusting the dentist—Expecting a leap of faith vs a well-defined strategy for anxious patients. Dent. J. 2022, 10, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magzoub, A.; Tawfig, N.; Satti, A.; Gobara, B. Periodontal health status and periodontal treatment needs of prisoners in two jails in Khartoum state. Int. J. Dent. Oral Sci. 2016, 3, 233–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dayakar, M.M.; Shivprasad, D.; Pai, P.G. Assessment of periodontal health status among prison inmates: A cross-sectional survey. J. Indian Soc. Periodontol. 2014, 18, 74–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vainionpää, R.; Peltokangas, A.; Leinonen, J.; Pesonen, P.; Laitala, M.-L.; Anttonen, V. Oral health and oral health-related habits of Finnish prisoners. BDJ Open 2017, 3, 17006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shekarchizadeh, H.; Khami, M.R.; Mohebbi, S.Z.Z.; Ekhtiari, H.; Virtanen, J.I. Oral health status and its determinants among opiate dependents: A cross-sectional study. BMC Oral Health 2019, 19, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ancely, A.; Laurencin-Dalicieux, S.; Baussois, C.; Blanc, A.; Nabet, C.; Thomas, C.; Fournier, G. Caries and periodontal health status of male inmates: A retrospective study conducted in a French prison. Int. J. Prison Health 2024, 20, 344–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shah, H.; Khan, I.; Khan, S.U.; Kershan, J.; Ahmed, S.; Ayaz, S.; Usman, G. Chewable tobacco is significantly associated with dental caries and periodontitis among incarcerated women in prison. Pak. J. Med. Dent. 2023, 12, 24–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta, V.; Tripathy, S.; Shamim, M.A.; Sarode, G.S.; Rizwan, S.A.; Mathur, A.; Sarode, S.C. Oral health status of prisoners in India: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Spec. Care Dentist 2024, 44, 1359–1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evensen, K.B.; Bull, V.H. Oral health in prison: An integrative review. Int. J. Prison Health 2022, 19, 251–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, P.; Saha, S.S.S.; Singh, S.S.S.; Jagannath, G.V. Nature of crime, duration of stay, parafunctional habits and periodontal status in prisoners. J. Oral Health Commun. Dent. 2012, 6, 131–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bush, M.M.A. An oral cavity profile in illicit- drug abusers? J. Indian Soc. Periodontol. 2019, 23, 517–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, H.; Khan, I.; Khan, M.S.U.; Kershan, J.; Ahmed, S.; Ayaz, S. Dental caries, periodontal health status, and oral hygiene related habits of women behind bars in central jail Karachi, Sindh, Pakistan. J. Bahria Univ. Med. Dent. Col. 2024, 14, 13–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavalcanti, A.L.; Rodrigues, I.S.A.A.; Silveira, I.T.M.; Oliveira, T.B.S.; Pinto, M.S.A.; Xavier, A.F.C.; Castro, R.D.; Padilha, W.W.N. Dental caries experience and use of dental services among Brazilian prisoners. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2014, 11, 12118–12128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longhi, M.T.M.; Silva, R.U.O.; Gasque, K.C.S.; Lima, D.C.; Oliveira, J.M.; Caldeira, F.I.D. Impact of oral comorbidities on incarcerated women: An integrative review. Rev. Esp. Sanid. Penit. 2022, 24, 94–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uspenskaya, O.A.; Plishkina, A.A.; Zhdanova, M.L.; Goryacheva, I.P.; Kuzmicheva, E.E. Estimation of the dental status in persons in the investigative insulator. Med. Pharmaceut J. Pulse 2021, 23, 129–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jepsen, S.; Blanco, J.; Buchalla, W.; Carvalho, J.C.; Dietrich, T.; Dörfer, C.; Eaton, K.A.; Figuero, E.; Frencken, J.E.; Graziani, F.; et al. Prevention and control of dental caries and periodontal diseases at individual and population level: Consensus report of group 3 of joint EFP/ORCA workshop on the boundaries between caries and periodontal diseases. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2017, 44 (Suppl. S18), S85–S93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieira, J.M.R.; Pereira, J.V.; Júnior, E.C.S.; Corrêa, A.C.C.; dos Santos, A.B.S.; da Silva, T.S.; Vieira, W.d.A.; Quadros, L.N.; Rebelo, M.A.B. Prevalence of dental caries, periodontal disease, malocclusion, and tooth wear in indigenous populations in Brazil: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Braz. Oral Res. 2023, 37, e094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonseca, F.A.; Jones, K.M.; Mendes, D.C.; Neto, P.E.S.; Ferreira, R.C.; Pordeus, I.A.; Martins, A.M.E.B.L. The oral health of seniors in Brazil: Addressing the consequences of a historic lack of public health dentistry in an unequal society. Gerodontol 2015, 32, 18–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, H.; Palmer, C.E. Studies on Dental Caries: X. A Procedure for the Recording and Statistical Processing of Dental Examination Findings. J. Dent. Res. 1940, 19, 243–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neves, L.T.; Costa, B.; Lauris, J.R.P.; Ciamponi, A.L.; Gomide, M.R. An evaluation of dental caries status in children with oral clefts: A cross-sectional study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mauricio, H.A.; Fávaro, T.R.; Moreira, R.S. Oral Health inequality: Characterization of the indigenous people Xukuru do Ororuba, Pernambuco, Brazil. Cien Saude Colet. 2024, 29, e06712024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopes, A.G.; Cezário, L.R.; Mialhe, F.L. The Influence of socioeconomic and behavioral factors on the caries experience of adults with mental disorders in a large Brazilian metropolis. Can. J. Dent. Hyg. 2024, 58, 149–154. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Cardoso, L.B.; Couto, P.; Correia, P.; Lopes, P.C.; Fernandes, J.C.H.; Fernandes, G.V.O.; Veiga, N.J. Impact of Digital Innovations on Health Literacy Applied to Patients with Special Needs: A Systematic Review. Information 2024, 15, 663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, E.M.; Alves, M.T.S.S.B.E.; Rudakoff, L.C.S.; Silva, N.P.; Franco, M.M.P.; Ribeiro, C.C.C.; Alves, C.M.C.; Thomaz, E.B.A.F. Consumption of ultra-processed foods and dental caries in Brazilian adolescents. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 26170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marques, V.O.; Kort-Kamp, L.M.; Souza, M.A.N.; Portela, M.B.; Castro, G.F.B.A. Oral health and behavioral management of children with autistic spectrum disorder: A 30-year retrospective study. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2025, 55, 250–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, K.; Saini, R.S.; Quadri, S.A.; Fernandes, G.V.O.; Avetisyan, A.; Mosaddad, S.A.; Heboyan, A. Bibliometric analysis of trends in dental management of the children with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD). Discov. Ment. Health 2025, 5, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gushi, L.L.; Soares, M.C.; Forni, T.I.B.; Vieira, V.; Wada, R.S.; Sousa, M.L.R. Relationship between dental caries and socioeconomic factors in adolescentes. J. Appl. Oral Sci. 2005, 13, 305–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corassa, R.B.; Silva, C.J.P.; Paula, J.S.; Aquino, E.C.; Sardinha, L.M.V.; Alves, P.A.B. Self-reported oral health among Brazilian adults: Results from the National Health Surveys 2013 and 2019. Epidemiol. Serv. Saude 2022, 31, e2021383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veiga, N.; Lopes, P.C.; Pires, B.; Couto, P.; Correia, P.; Fernandes, J.C.H.; Fernandes, G.V.O. Application of digital technologies in health literacy in situations of social isolation: A systematic review. Rev. Flum. Odontol. 2025, 68, 215–231. [Google Scholar]

- Tenani, C.F.; Silva-Junior, M.F.; Lino, C.M.; Sousa, M.L.R.; Batista, M.J. The role of literacy as a factor associated with dental losses. Rev. Saude Publica 2021, 55, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borges, R.C.; Echeverria, M.S.; Karam, S.A.; Horta, B.L.; Demarco, F.F. Use of dental services among adults from a birth cohort in the South Region of Brazil. Rev. Saude Publica 2023, 57, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borkman, M.; Campbell, L.V.; Chisholm, D.J.; Storlien, L.H. Comparison of the effects on insulin sensitivity of high carbohydrate and high fat diets in normal subjects. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 1991, 72, 432–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riccardi, G.; Rivellese, A.A.; Giacco, R. Role of glycemic index and glycemic load in the healthy state, in prediabetes, and in diabetes. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2008, 87, 269S–274S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, R.W.; Mann, J.I.; Eaton, J.; Moore, R.A.; Carter, R.; Hockaday, T.D. Improved glucose control in maturity-onset diabetes treated with high-carbohydrate-modified fat diet. Br. Med. J. 1979, 1, 1753–1756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allick, G.; Bisschop, P.H.; Ackermans, M.T.; Endert, E.; Meijer, A.J.; Kuipers, F.; Sauerwein, H.P.; Romijn, J. A low-carbohydrate/high-fat diet improves glucoregulation in type 2 diabetes mellitus by reducing postabsorptive glycogenolysis. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2004, 89, 6193–6197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Natale, C.; Annuzzi, G.; Bozzetto, L.; Mazzarella, R.; Costabile, G.; Ciano, O.; Riccardi, G.; Rivellese, A.A. Effects of a plant-based high-carbohydrate/high-fiber diet versus high–monounsaturated fat/low-carbohydrate diet on postprandial lipids in type 2 diabetic patients. Diabetes Care 2009, 32, 2168–2173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moldvai, J.; Orsós, M.; Herczeg, E.; Uhrin, E.; Kivovics, M.; Németh, O. Oral health status and its associated factors among post-stroke inpatients: A cross-sectional study in Hungary. BMC Oral Health 2022, 22, 234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheth, C.; López-Pedrajas, R.; Jovani-Sancho, M.; González-Martínez, R.; Veses, V. Modulation of salivary cytokines in response to alcohol, tobacco and caffeine consumption: A pilot study. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 16687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo Giudice, G.; Cicciù, M.; Polimeni, A.; Lizio, A.; Lo Giudice, R.; Lauritano, F.; Ierardo, G.; Alibrandi, A.; Pizzo, G. Oral and dental health of Italian drug addicted in methadone treatment. Oral Sci. Int. 2019, 16, 8–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, B.; John, J.; Saravanan, S.; Arumugham, I.M.; Johny, M.K. Dental caries status of inmates in central prison, Chennai, Tamil Nadu, India. J. Nat. Sci. Biol. Med. 2015, 6, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mthethwa, J.M.; Mahomed, O.H.; Yengopal, V. Epidemiological profile of patients utilizing dental public health services in the eThekwini and uMgungundlovu districts of Kwazulu-Natal province, South Africa. S. Afr. Dent. J. 2020, 75, 541–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkhadra, T. Prevalence of dental caries and oral hygiene status among juvenile prisoners in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. J. Contemp. Dent. Pract. 2017, 18, 991–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manna, S.; Tripathy, S.; Sah, R.K.; Padhi, B.K.; Kaur, S.; Nowrouzi-Kia, B.; Chattu, V.K. The burden of non-communicable diseases (NCDs) among prisoners in India: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Healthcare 2022, 10, 2046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, M.B.; Plana, J.M.C.; González, P.I.A. Prevalence and severity of periodontal disease among Spanish military personnel. BMJ Mil. Health 2020, 168, 132–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amaliya, A.; Pribadi, S.; Akbar, Y.M.; Sitam, S. Periodontal disease: A rise in prevalence in military troops penyakit periodontal. Odonto Dent. J. 2021, 8, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, M.B.; Plana, J.M.C.; Cagiao, G.R.; González, P.I.A. Epidemiological methods used in the periodontal health research in military personnel: A systematic review. BMJ Mil. Health 2024, 170, 72–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nutbeam, D. Health literacy as a public health goal: A challenge for contemporary health education and communication strategies into the 21st century. Health Promot. Int. 2000, 15, 259–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillam, D.G.; Yusuf, H. Brief motivational interviewing in Dental Practice. Dent. J. 2019, 7, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heidari, F.; Heboyan, A.; Rokaya, D.; Fernandes, G.V.O.; Heidari, M.; Banakar, M.; Zafar, M.S. Postbiotics and Dental Caries: A Systematic Review. Clin. Exp. Dental Res. 2025, 11, e70114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banakar, M.; Fernandes, G.V.O.; Etemad-Moghadam, S.; Frankenberger, R.; Pourhajibagher, M.; Mehran, M.; Yazdi, M.H.; Haghgoo, R.; Alaeddini, M. The Strategic Role of Biotics in Dental Caries Prevention: A Scoping Review. Food Sci. Nutr. 2024, 12, 8651–8674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ochôa, C.; Castro, F.; Bulhosa, J.F.; Manso, C.; Fernandes, J.C.H.; Fernandes, G.V.O. Influence of the Probiotic L. reuteri in the Nonsurgical Treatment of Periodontal Disease: A Systematic Review. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 1449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purpura, S.; Fernandes, G.V.O.; Oliveira, F.P.; Castro, F.C. Effects of Melatonin in the Non-Surgical Treatment of Periodontitis: A Systematic Review. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 11698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Group | Age Interval | n | Age | ± SD | Decayed (D) | ± SD | Missed (M) | ± SD | Filled (F) | ± SD | DMFT (Sum) | ± SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 18–27 | 889 | 23.21 | 2.5 | 2.94 | 2.74 | 2.84 | 2.27 | 1.09 | 2.27 | 6.89 | 4.82 |

| 2 | 28–37 | 388 | 31.04 | 2.71 | 3.38 | 2.65 | 5.82 | 3.06 | 1.7 | 3.06 | 10.87 | 6.33 |

| 3 | 38–47 | 83 | 42.3 | 2.99 | 3.11 | 2.56 | 10.5 | 7.04 | 1.92 | 4.13 | 16 | 7.64 |

| 4 | ≥48 | 25 | 53.5 | 3.89 | 3.75 | 3.1 | 18.12 | 7.71 | 0.62 | 1.18 | 22.5 | 6.71 |

| F-statistic | - | 4.69 | 363.2 | 17.07 | 147.96 | |||||||

| p-value | - | 0.0029 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | |||||||

| Outcome Variable | Coefficient (β) | Std. Error | t-Value | p-Value | 95% Confidence Interval | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Decayed (D) | 0.0065 | 0.003 | 2.52 | 0.012 | [0.001, 0.012] | Significant positive association: Older age is slightly associated with an increased number of decayed teeth. |

| Missed (M) | 0.3964 | 0.005 | 75.71 | <0.001 | [0.386, 0.407] | Strong positive association: Each year of age increases the number of missed teeth by ~0.40. |

| Filled (F) | −0.0111 | 0.003 | −4.21 | <0.001 | [−0.016, −0.006] | Negative association: Increasing age is linked to fewer filled teeth. |

| DMF (D+M+F) | 0.4910 | 0.006 | 78.38 | <0.001 | [0.480, 0.502] | Very strong positive association: Each additional year contributes ~0.49 more total DMF. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Reis, W.A.d.; Martins, B.G.d.S.; Resende, R.; Medeiros, U.V.d.; Fernandes, J.C.H.; Fernandes, G.V.O. Oral Health Assessment in Prisoners: A Cross-Sectional Observational and Epidemiological Study. Epidemiologia 2025, 6, 88. https://doi.org/10.3390/epidemiologia6040088

Reis WAd, Martins BGdS, Resende R, Medeiros UVd, Fernandes JCH, Fernandes GVO. Oral Health Assessment in Prisoners: A Cross-Sectional Observational and Epidemiological Study. Epidemiologia. 2025; 6(4):88. https://doi.org/10.3390/epidemiologia6040088

Chicago/Turabian StyleReis, William Alves dos, Bruno Gomes dos Santos Martins, Rodrigo Resende, Urubatan Vieira de Medeiros, Juliana Campos Hasse Fernandes, and Gustavo Vicentis Oliveira Fernandes. 2025. "Oral Health Assessment in Prisoners: A Cross-Sectional Observational and Epidemiological Study" Epidemiologia 6, no. 4: 88. https://doi.org/10.3390/epidemiologia6040088

APA StyleReis, W. A. d., Martins, B. G. d. S., Resende, R., Medeiros, U. V. d., Fernandes, J. C. H., & Fernandes, G. V. O. (2025). Oral Health Assessment in Prisoners: A Cross-Sectional Observational and Epidemiological Study. Epidemiologia, 6(4), 88. https://doi.org/10.3390/epidemiologia6040088