Modeling SnC-Anode Material for Hybrid Li, Na, Be, Mg Ion-Batteries: Structural and Electronic Analysis by Mastering the Density of States

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

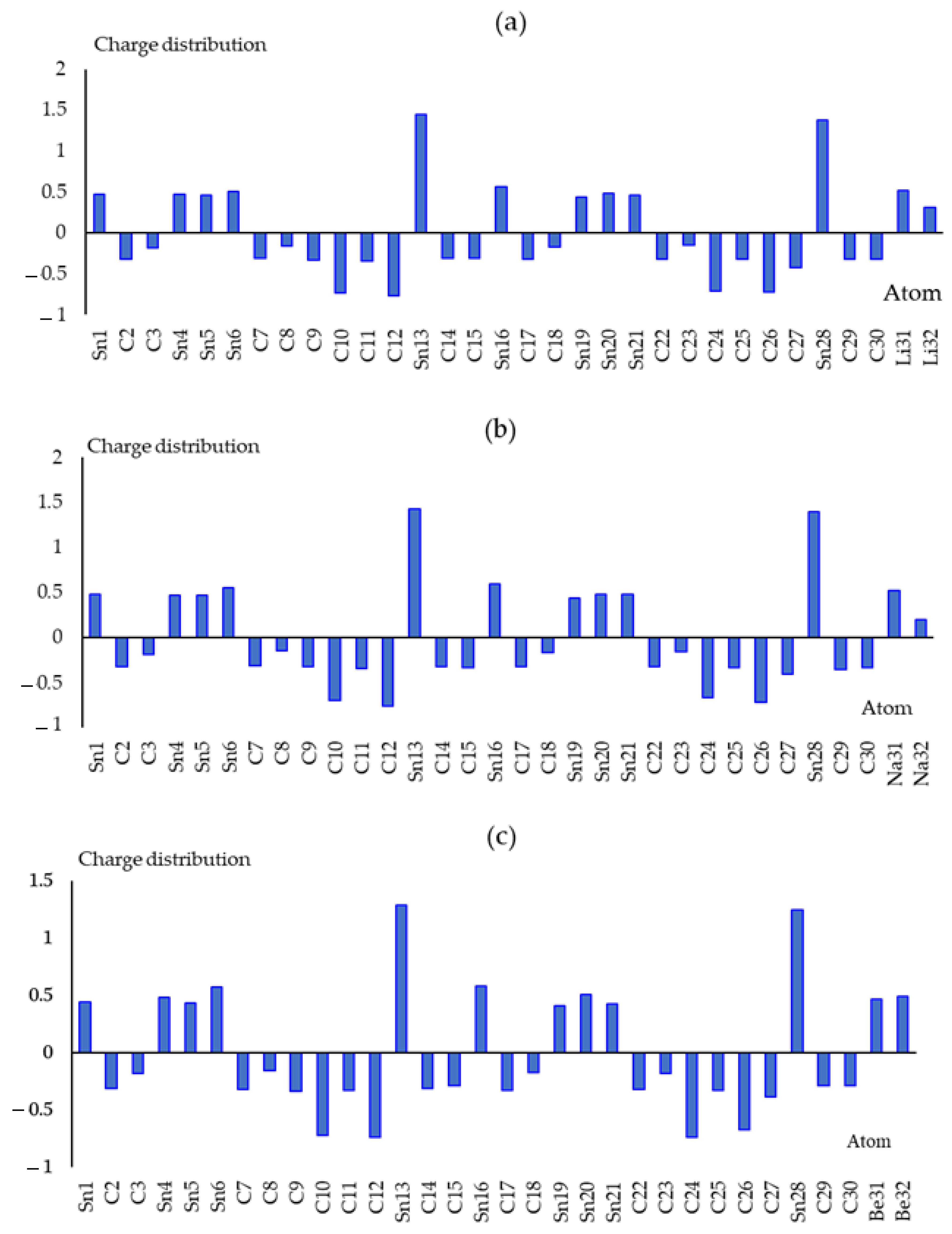

| Sn(Li2)C | Sn(Na2)C | Sn(Be2)C | Sn(Mg2)C | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

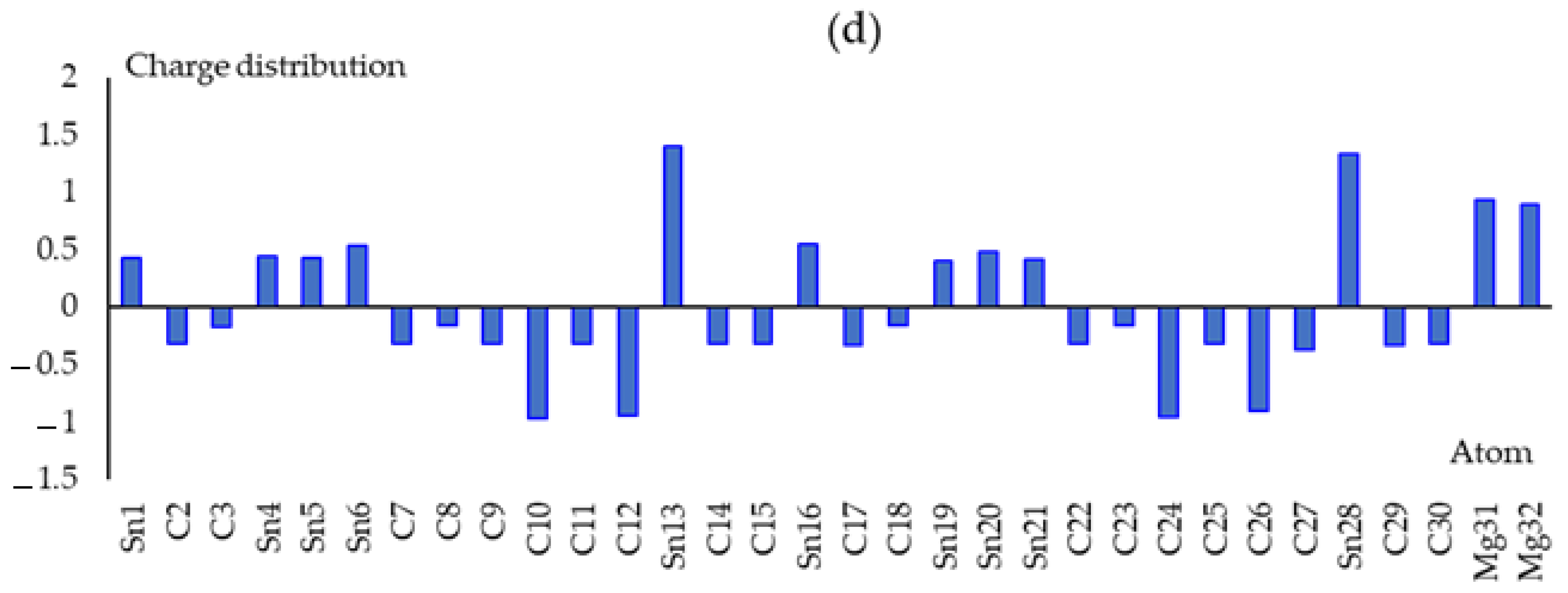

| Atom | Q | Atom | Q | Atom | Q | Atom | Q |

| Sn(1) | 0.476 | Sn(1) | 0.483 | Sn(1) | 0.443 | Sn(1) | 0.434 |

| C(2) | −0.318 | C(2) | −0.322 | C(2) | −0.313 | C(2) | −0.314 |

| C(3) | −0.179 | C(3) | −0.182 | C(3) | −0.182 | C(3) | −0.166 |

| Sn(4) | 0.470 | Sn(4) | 0.470 | Sn(4) | 0.483 | Sn(4) | 0.442 |

| Sn(5) | 0.464 | Sn(5) | 0.471 | Sn(5) | 0.440 | Sn(5) | 0.431 |

| Sn(6) | 0.511 | Sn(6) | 0.553 | Sn(6) | 0.572 | Sn(6) | 0.538 |

| C(7) | −0.310 | C(7) | −0.310 | C(7) | −0.318 | C(7) | −0.310 |

| C(8) | −0.156 | C(8) | −0.150 | C(8) | −0.157 | C(8) | −0.151 |

| C(9) | −0.335 | C(9) | −0.327 | C(9) | −0.333 | C(9) | −0.315 |

| C(10) | −0.735 | C(10) | −0.699 | C(10) | −0.720 | C(10) | −0.971 |

| C(11) | −0.344 | C(11) | −0.342 | C(11) | −0.325 | C(11) | −0.309 |

| C(12) | −0.763 | C(12) | −0.765 | C(12) | −0.733 | C(12) | −0.933 |

| Sn(13) | 1.442 | Sn(13) | 1.430 | Sn(13) | 1.285 | Sn(13) | 1.397 |

| C(14) | −0.303 | C(14) | −0.319 | C(14) | −0.306 | C(14) | −0.319 |

| C(15) | −0.311 | C(15) | −0.330 | C(15) | −0.287 | C(15) | −0.317 |

| Sn(16) | 0.558 | Sn(16) | 0.597 | Sn(16) | 0.583 | Sn(16) | 0.553 |

| C(17) | −0.321 | C(17) | −0.322 | C(17) | −0.326 | C(17) | −0.325 |

| C(18) | −0.169 | C(18) | −0.168 | C(18) | −0.168 | C(18) | −0.156 |

| Sn(19) | 0.435 | Sn(19) | 0.441 | Sn(19) | 0.409 | Sn(19) | 0.398 |

| Sn(20) | 0.484 | Sn(20) | 0.484 | Sn(20) | 0.508 | Sn(20) | 0.480 |

| Sn(21) | 0.466 | Sn(21) | 0.477 | Sn(21) | 0.428 | Sn(21) | 0.418 |

| C(22) | −0.320 | C(22) | −0.319 | C(22) | −0.320 | C(22) | −0.320 |

| C(23) | −0.149 | C(23) | −0.152 | C(23) | −0.179 | C(23) | −0.161 |

| C(24) | −0.705 | C(24) | −0.664 | C(24) | −0.736 | C(24) | −0.949 |

| C(25) | −0.323 | C(25) | −0.328 | C(25) | −0.327 | C(25) | −0.314 |

| C(26) | −0.721 | C(26) | −0.724 | C(26) | −0.668 | C(26) | −0.898 |

| C(27) | −0.418 | C(27) | −0.407 | C(27) | −0.384 | C(27) | −0.373 |

| Sn(28) | 1.379 | Sn(28) | 1.397 | Sn(28) | 1.245 | Sn(28) | 1.336 |

| C(29) | −0.323 | C(29) | −0.349 | C(29) | −0.289 | C(29) | −0.329 |

| C(30) | −0.315 | C(30) | −0.333 | C(30) | −0.289 | C(30) | −0.320 |

| Li(31) | 0.522 | Na(31) | 0.519 | Be(31) | 0.471 | Mg(31) | 0.929 |

| Li(32) | 0.311 | Na(32) | 0.194 | Be(32) | 0.494 | Mg(32) | 0.896 |

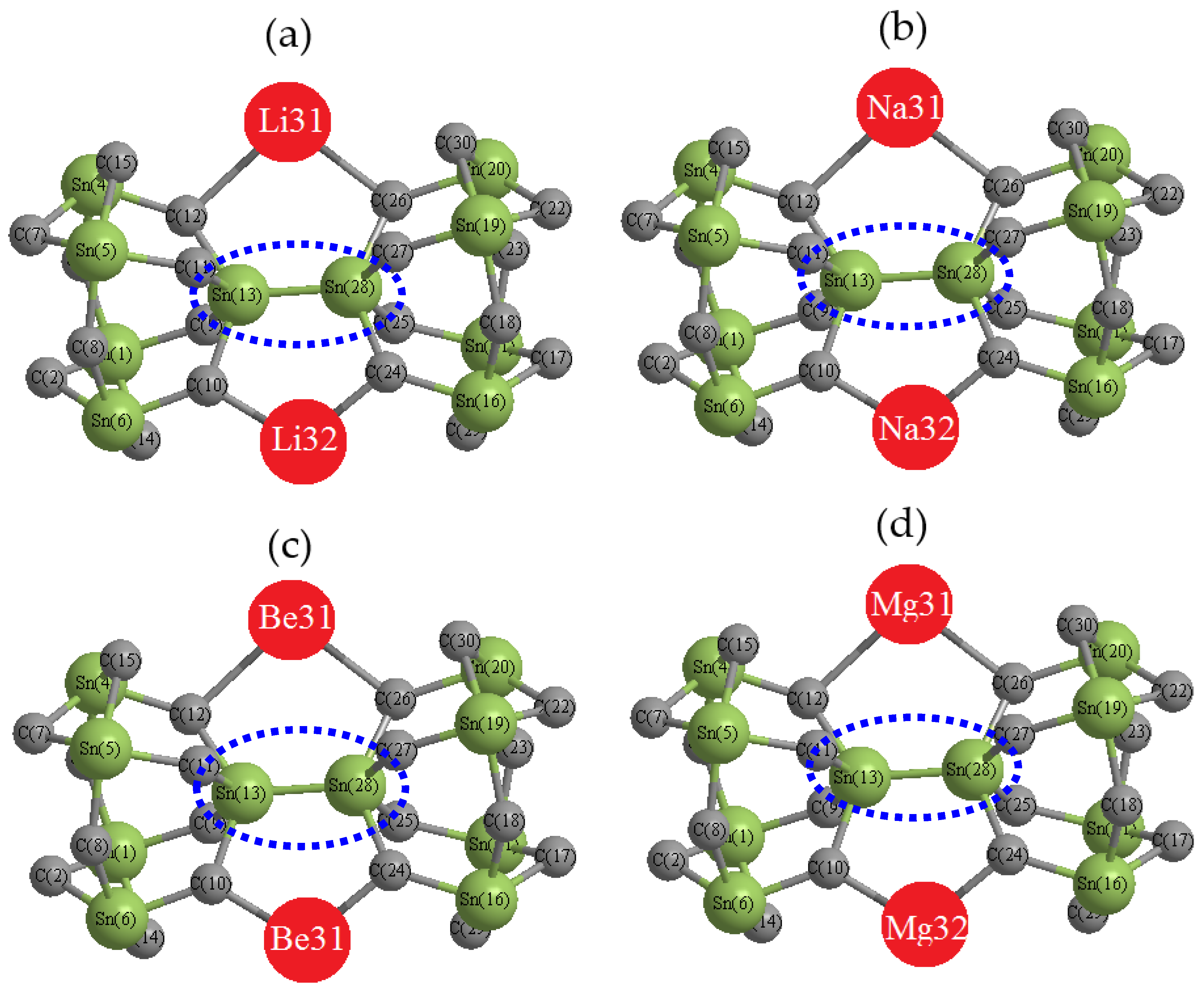

3. Results and Discussion

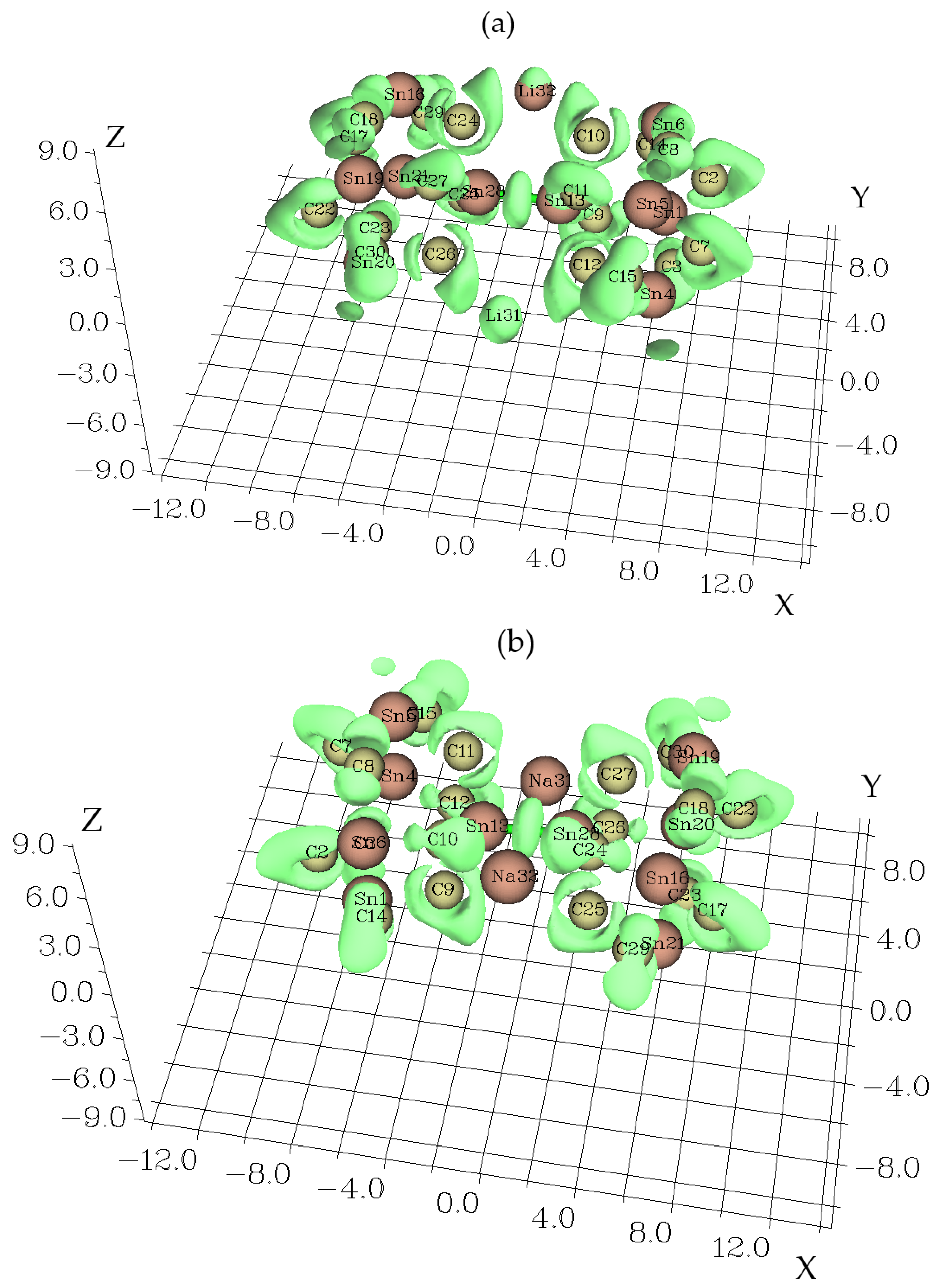

3.1. Charge Density Differences Analysis

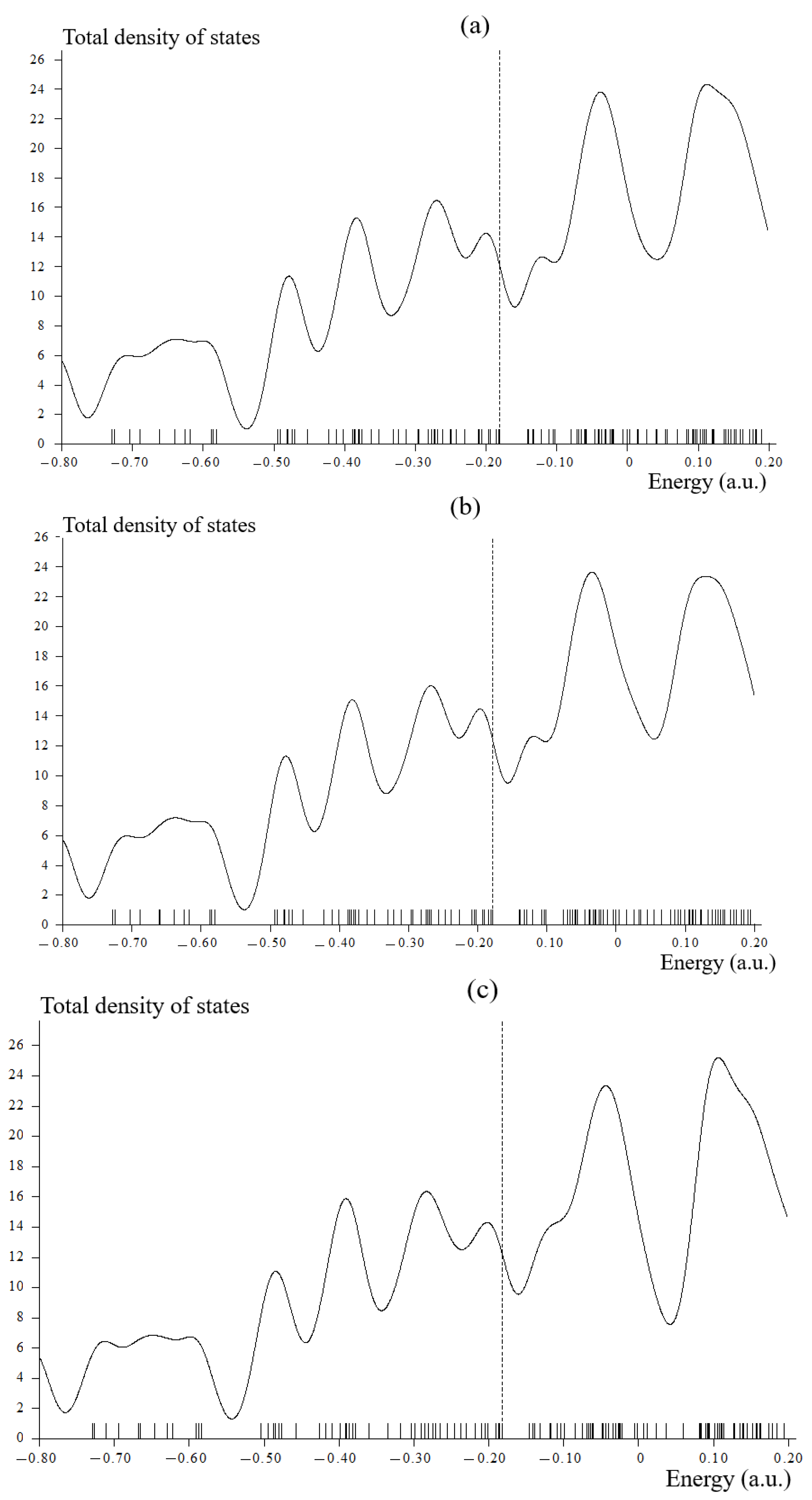

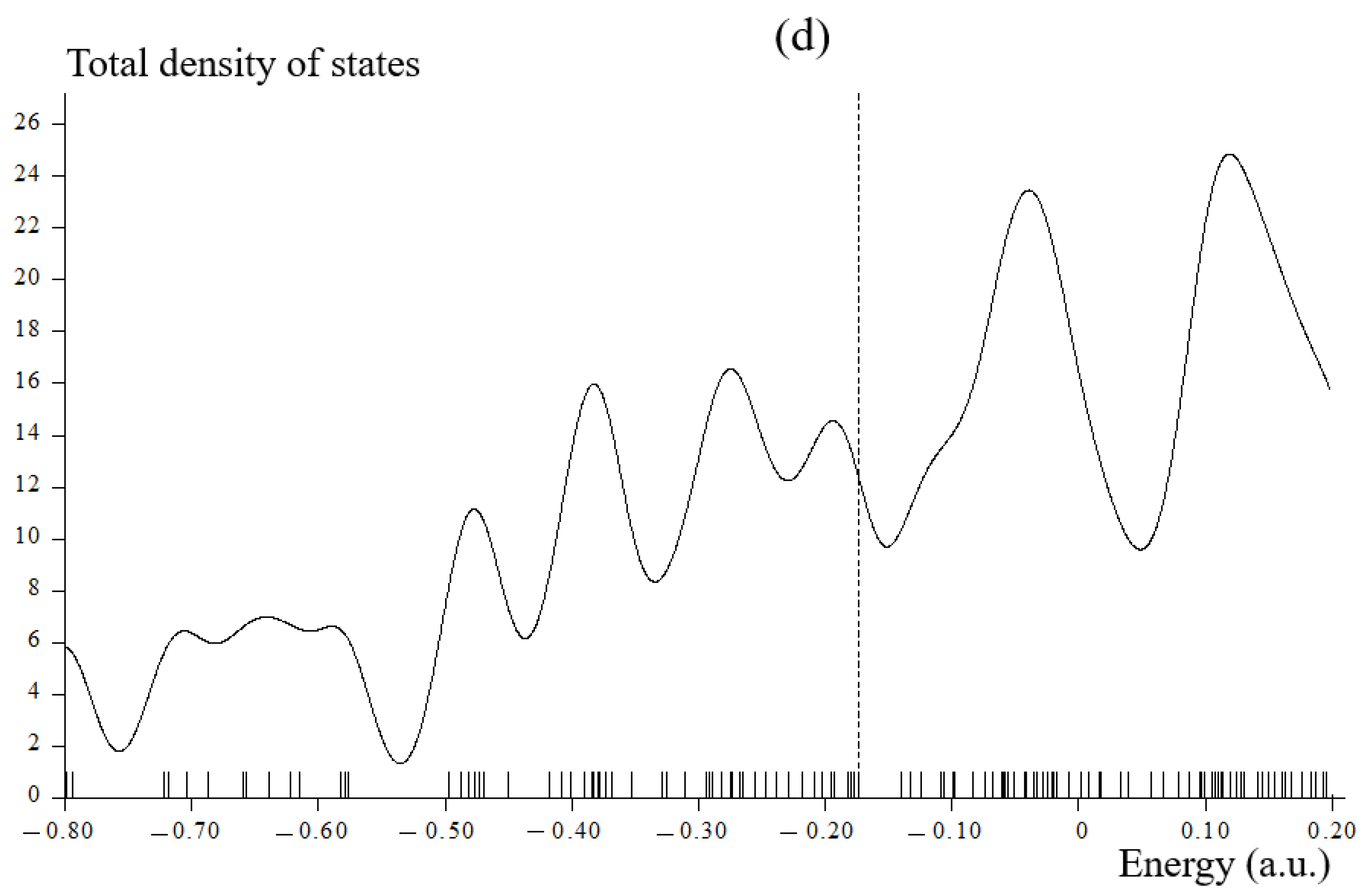

3.2. Total Density of States

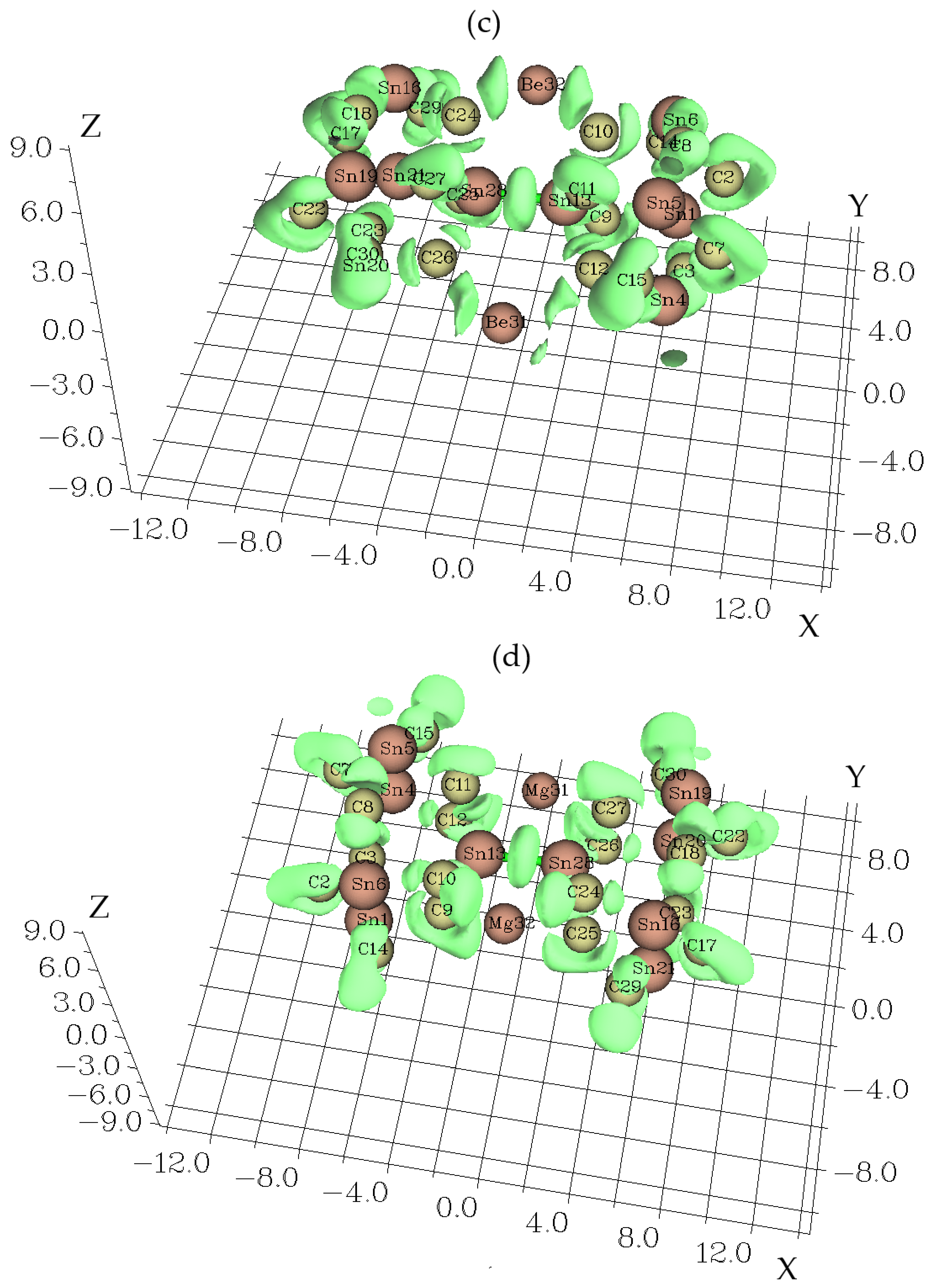

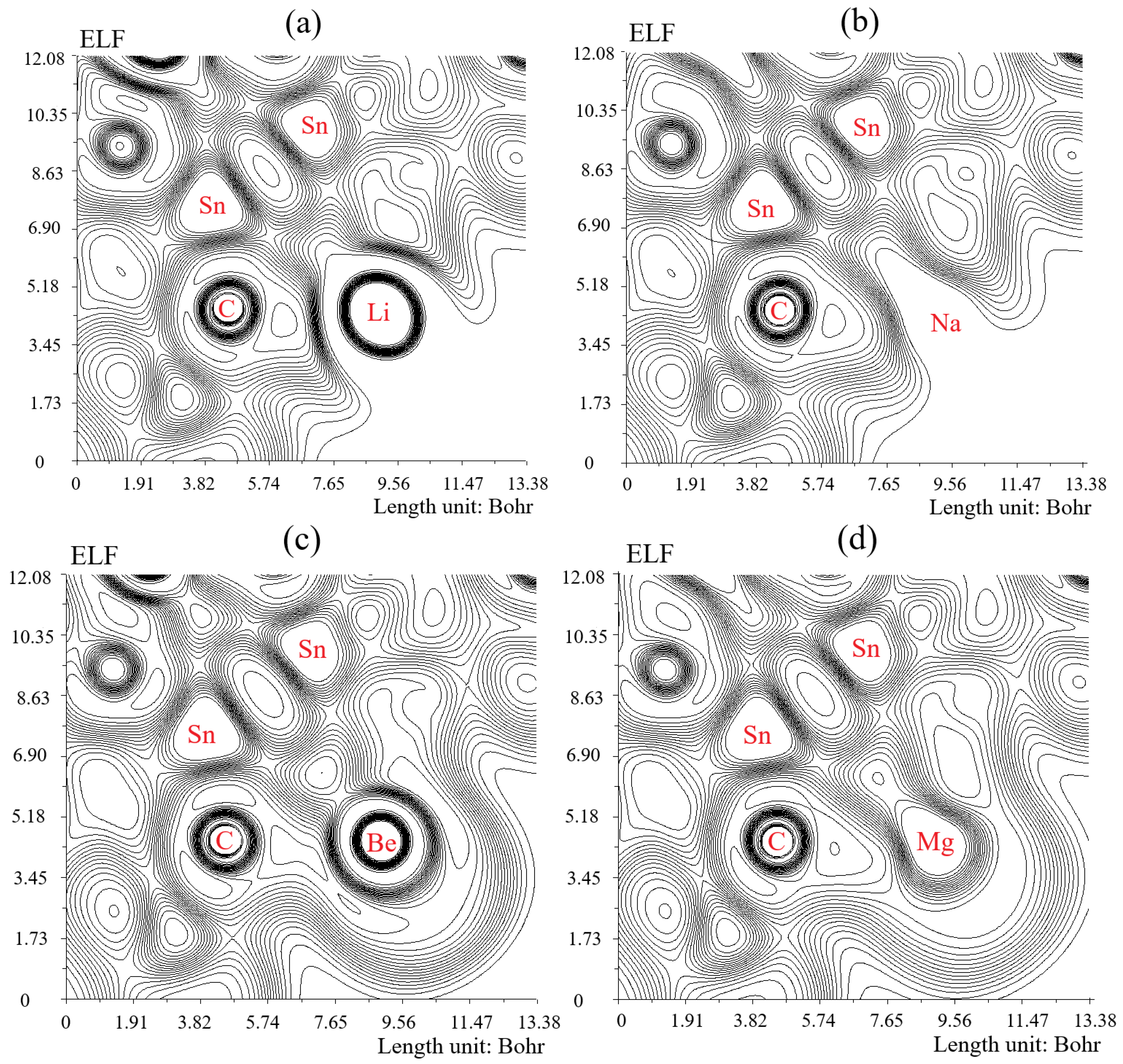

3.3. Electron Localization Function Analysis

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Xiao, W.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Fang, R.; Yuan, Z.; Miao, C.; Yan, X.; Jiang, Y. Enhanced performance of P(VDF-HFP)-based composite polymer electrolytes doped with organic-inorganic hybrid particles PMMA-ZrO2 for lithium ion batteries. J. Power Sources 2018, 382, 128–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mollaamin, F. Anchoring of 2D layered materials of Ge5Si5O20 for (Li/Na/K)-(Rb/Cs) batteries towards Eco-friendly energy storage. BMC Chem. 2025, 19, 233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qian, J.; Xiong, Y.; Cao, Y.; Ai, X.; Yang, H. Synergistic Na-storage reactions in Sn4P3 as a high-capacity, cycle-stable anode of Na-ion batteries. Nano Lett. 2014, 14, 1865–1869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, P.; Zhou, L.; Yu, Z.; Sun, Y.; Liu, Y.; Wu, F.; Jiang, Y.; Chu, D. Recent progress of surface coating on cathode materials for high-performance lithium-ion batteries. J. Energy Chem. 2020, 43, 220–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Jia, Z.; Chen, Y.; Weadock, N.; Wan, J.; Vaaland, O.; Han, X.; Li, T.; Hu, L. Tin anode for sodium-ion batteries using natural wood fiber as a mechanical buffer and electrolyte reservoir. Nano Lett. 2013, 13, 3093–3100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, S.; Ni, J.; Xu, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Li, L. Hydrogenation driven conductive Na2Ti3O7 nanoarrays as robust binder-free anodes for sodium-ion batteries. Nano Lett. 2016, 16, 4544–4551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, N.; Arthur, T.S.; Ling, C.; Matsui, M.; Mizuno, F. A high energy-density tin anode for rechargeable magnesium-ion batteries. Chem. Commun. 2013, 49, 149–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jadav, H.; Matth, S.; Pandey, H. Density Functional Investigations on 2D-Be2C as an Anode for Alkali Metal-Ion Batteries. Energy Storage 2024, 6, e70048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mou, H.; Xiao, W.; Miao, C.; Li, R.; Yu, L. Tin and Tin Compound Materials as Anodes in Lithium-Ion and Sodium-Ion Batteries: A Review. Front Chem. 2020, 8, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mollaamin, F.; Monajjemi, M. Nanomaterials for Sustainable Energy in Hydrogen-Fuel Cell: Functionalization and Characterization of Carbon Nano-Semiconductors with Silicon, Germanium, Tin or Lead through Density Functional Theory Study. Russ. J. Phys. Chem. B 2024, 18, 607–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehman, J.; Fan, X.; Zheng, W.T. 2D SnC sheet with a small strain is a promising Li host material for Li-ion batteries. Mater. Today Commun. 2021, 26, 101768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mollaamin, F. Alkali Metals Doped on Tin-Silicon and Germanium-Silicon Oxides for Energy Storage in Hybrid Biofuel Cells: A First-Principles Study. Russ. J. Phys. Chem. B 2025, 19, 722–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butt, M.K.; Zeeshan, H.M.; Dinh, V.A.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, S.; Jin, K. Monolayer SnC as anode material for Na ion batteries. Comput. Mater. Sci. 2021, 197, 110617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohn, W.; Sham, L.J. Self-Consistent Equations Including Exchange and Correlation Effects. Phys. Rev. 1965, 140, A1133–A1138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.; Yang, W.; Parr, R.G. Development of the Colle–Salvetti correlation-energy formula into a functional of the electron density. Phys. Rev. B 1988, 37, 785–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henkelman, G.; Arnaldsson, A.; Jónsson, H. A fast and robust algorithm for Bader decomposition of charge density. Comput. Mater. Sci. 2006, 36, 354–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frisch, M.J.; Trucks, G.W.; Schlegel, H.B.; Scuseria, G.E.; Robb, M.A.; Cheeseman, J.R.; Scalmani, G.; Barone, V.; Petersson, G.A.; Nakatsuji, H.; et al. Gaussian 16, Revision C.01; Gaussian, Inc.: Wallingford, CT, USA, 2016.

- Dennington, R.; Keith, T.A.; Millam, J.M. GaussView, Version 6.06.16; Semichem Inc.: Shawnee Mission, KS, USA, 2016.

- Xu, Z.; Qin, C.; Yu, Y.; Jiang, G.; Zhao, L. First-principles study of adsorption, dissociation, and diffusion of hydrogen on α-U (110) surface. AIP Adv. 2024, 14, 055114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rukelj, Z.; Kupčić, I.; Radić, D. Density of States in the 3D System with Semimetallic Nodal-Loop and Insulating Gapped Phase. Symmetry 2024, 16, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, T.; Chen, F. Multiwfn: A multifunctional wavefunction analyzer. J. Comput. Chem. 2012, 33, 580–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, T. A comprehensive electron wavefunction analysis toolbox for chemists, Multiwfn. J. Chem. Phys. 2024, 161, 082503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matta, C.F.; Ayers, P.W.; Cook, R. The Physics of Electron Localization and Delocalization. In Electron Localization-Delocalization Matrices; Lecture Notes in Chemistry; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; Volume 112, pp. 7–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bader, R. The zero-flux surface and the topological and quantum definitions of an atom in a molecule. Theor. Chem. Acc. 2001, 105, 276–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becke, A.D.; Edgecombe, K.E. A simple measure of electron localization in atomic and molecular systems. J. Chem. Phys. 1990, 92, 5397–5403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savin, A.; Jepsen, O.; Flad, J.; Andersen, O.K.; Preuss, H.; von Schnering, H.G. Electron Localization in Solid-State Structures of the Elements: The Diamond Structure. Angew. Chem. Int. 1992, 31, 187–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, I. Improved definition of bond orders for correlated wave functions. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2012, 544, 83–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mollaamin, F. Competitive Intracellular Hydrogen-Nanocarrier Among Aluminum, Carbon, or Silicon Implantation: A Novel Technology of Eco-Friendly Energy Storage using Research Density Functional Theory. Russ. J. Phys. Chem. B 2024, 18, 805–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiberg, K.B. Application of the pople-santry-segal CNDO method to the cyclopropylcarbinyl and cyclobutyl cation and to bicyclobutane. Tetrahedron 1968, 24, 1083–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, T.; Chen, F. Bond Order Analysis Based on the Laplacian of Electron Density in Fuzzy Overlap Space. J. Phys. Chem. A 2013, 117, 3100–3108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zhang, X.; Pedrycz, W.; Yang, S.-H.; Boutat, D. Consensus of T-S Fuzzy Fractional-Order, Singular Perturbation, Multi-Agent Systems. Fractal Fract. 2024, 8, 523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Heteroclusters | Es × 10−3 (kcal/mol) | Dipole Moment (Debye) | EHOMO (eV) | ELUMO (eV) | ∆E = ELUMO–EHOMO (eV) | C (C, mAh g−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sn(Li2)C | −503.708 | 1.203 | −4.931 | −3.837 | 1.094 | 370.695 |

| Sn(Na2)C | −494.456 | 1.232 | −4.855 | −3.812 | 1.043 | 303.354 |

| Sn(Be2)C | −512.717 | 1.248 | −4.969 | −3.972 | 0.997 | 720.734 |

| Sn(Mg2)C | −495.296 | 0.626 | −4.713 | −3.812 | 0.900 | 597.810 |

| Compound | Bond Type | Bond Order | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mayer | Wiberg | Mulliken | Laplacian | Fuzzy | ||

| Sn(Li2)C | Sn(13)–Sn(28) | 0.189 | 0.516 | 0.504 | 0.363 | 0.846 |

| C(10)–Li(32) | 0.521 | 0.449 | 0.624 | 0.262 | 0.313 | |

| C(12)–Li(31) | 0.289 | 0.291 | 0.306 | 0.345 | 0.156 | |

| C(24)–Li(32) | 0.482 | 0.430 | 0.556 | 0.599 | 0.297 | |

| C(26)–Li(31) | 0.323 | 0.345 | 0.355 | 0.391 | 0.200 | |

| Sn(Na2)C | Sn(13)–Sn(28) | 0.166 | 0.515 | 0.577 | 0.370 | 0.815 |

| C(10)–Na(32) | 0.568 | 0.291 | 0.854 | 0.231 | 0.470 | |

| C(12)–Na(31) | 0.283 | 0.211 | 0.379 | 0.305 | 0.280 | |

| C(24)–Na(32) | 0.554 | 0.286 | 0.736 | 0.205 | 0.461 | |

| C(26)–Na(31) | 0.329 | 0.243 | 0.456 | 0.277 | 0.334 | |

| Sn(Be2)C | Sn(13)–Sn(28) | 0.359 | 0.566 | 0.687 | 0.545 | 0.886 |

| C(10)–Be(32) | 0.918 | 0.838 | 0.939 | 0.175 | 0.595 | |

| C(12)–Be(31) | 0.619 | 0.548 | 0.524 | 0.370 | 0.361 | |

| C(24)–Be(32) | 0.881 | 0.808 | 0.900 | 0.163 | 0.572 | |

| C(26)–Be(31) | 0.704 | 0.659 | 0.592 | 0.213 | 0.454 | |

| Sn(Mg2)C | Sn(13)–Sn(28) | 0.189 | 0.516 | 0.504 | 0.363 | 0.846 |

| C(10)–Mg(32) | 0.521 | 0.449 | 0.624 | 0.262 | 0.697 | |

| C(12–Mg(31) | 0.289 | 0.291 | 0.306 | 0.345 | 0.450 | |

| C(24)–Mg(32) | 0.482 | 0.430 | 0.556 | 0.199 | 0.673 | |

| C(26)–Mg(31) | 0.323 | 0.345 | 0.355 | 0.191 | 0.556 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Mollaamin, F.; Monajjemi, M. Modeling SnC-Anode Material for Hybrid Li, Na, Be, Mg Ion-Batteries: Structural and Electronic Analysis by Mastering the Density of States. Electron. Mater. 2026, 7, 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronicmat7010002

Mollaamin F, Monajjemi M. Modeling SnC-Anode Material for Hybrid Li, Na, Be, Mg Ion-Batteries: Structural and Electronic Analysis by Mastering the Density of States. Electronic Materials. 2026; 7(1):2. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronicmat7010002

Chicago/Turabian StyleMollaamin, Fatemeh, and Majid Monajjemi. 2026. "Modeling SnC-Anode Material for Hybrid Li, Na, Be, Mg Ion-Batteries: Structural and Electronic Analysis by Mastering the Density of States" Electronic Materials 7, no. 1: 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronicmat7010002

APA StyleMollaamin, F., & Monajjemi, M. (2026). Modeling SnC-Anode Material for Hybrid Li, Na, Be, Mg Ion-Batteries: Structural and Electronic Analysis by Mastering the Density of States. Electronic Materials, 7(1), 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronicmat7010002