Glycometabolic Control Does Not Affect Sexual Function in a Cohort of Women with Type 1 Diabetes: Results of an Observational Pilot Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

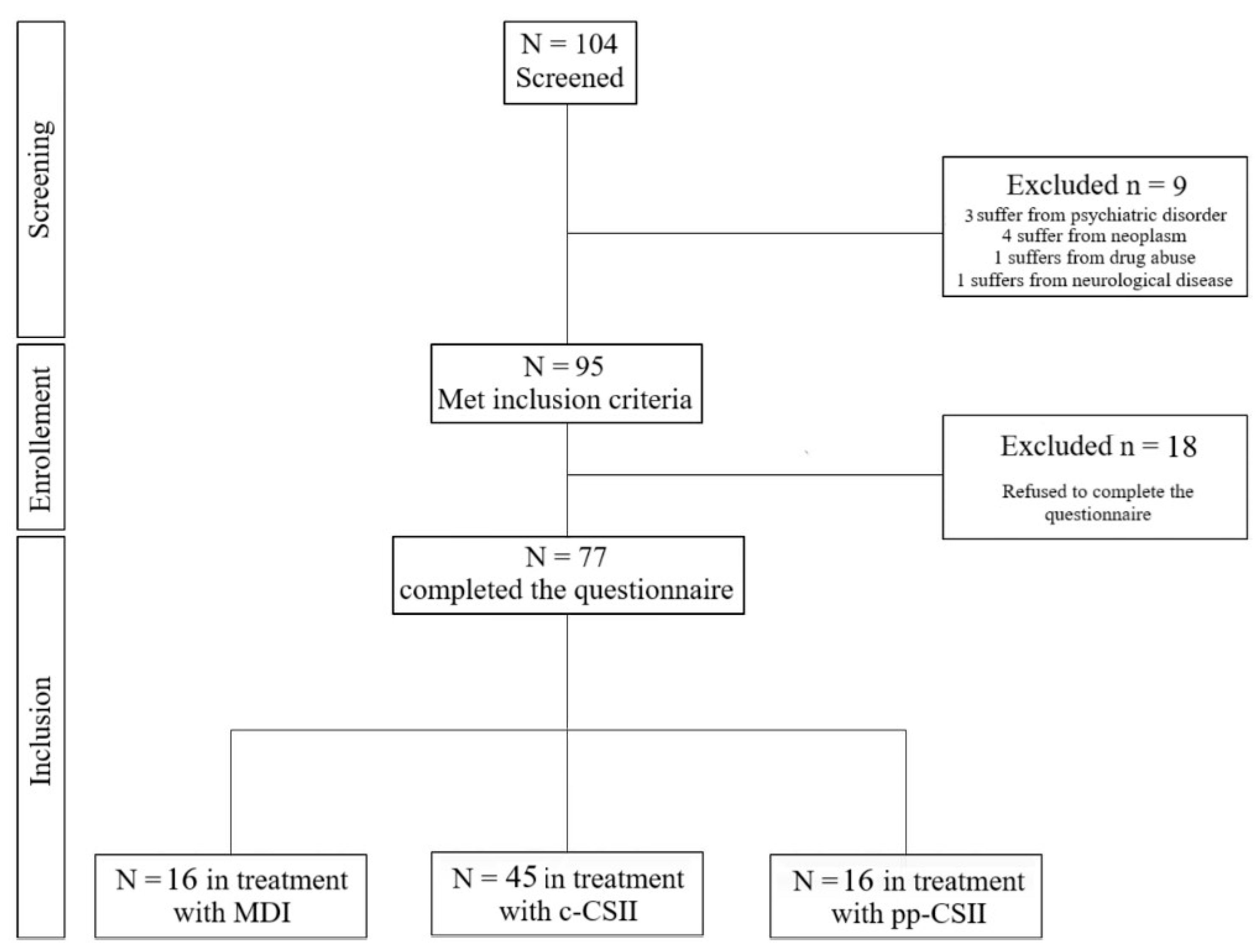

2.1. Participants

2.2. Questionnaire and Data Collection

2.3. Statistical Methods

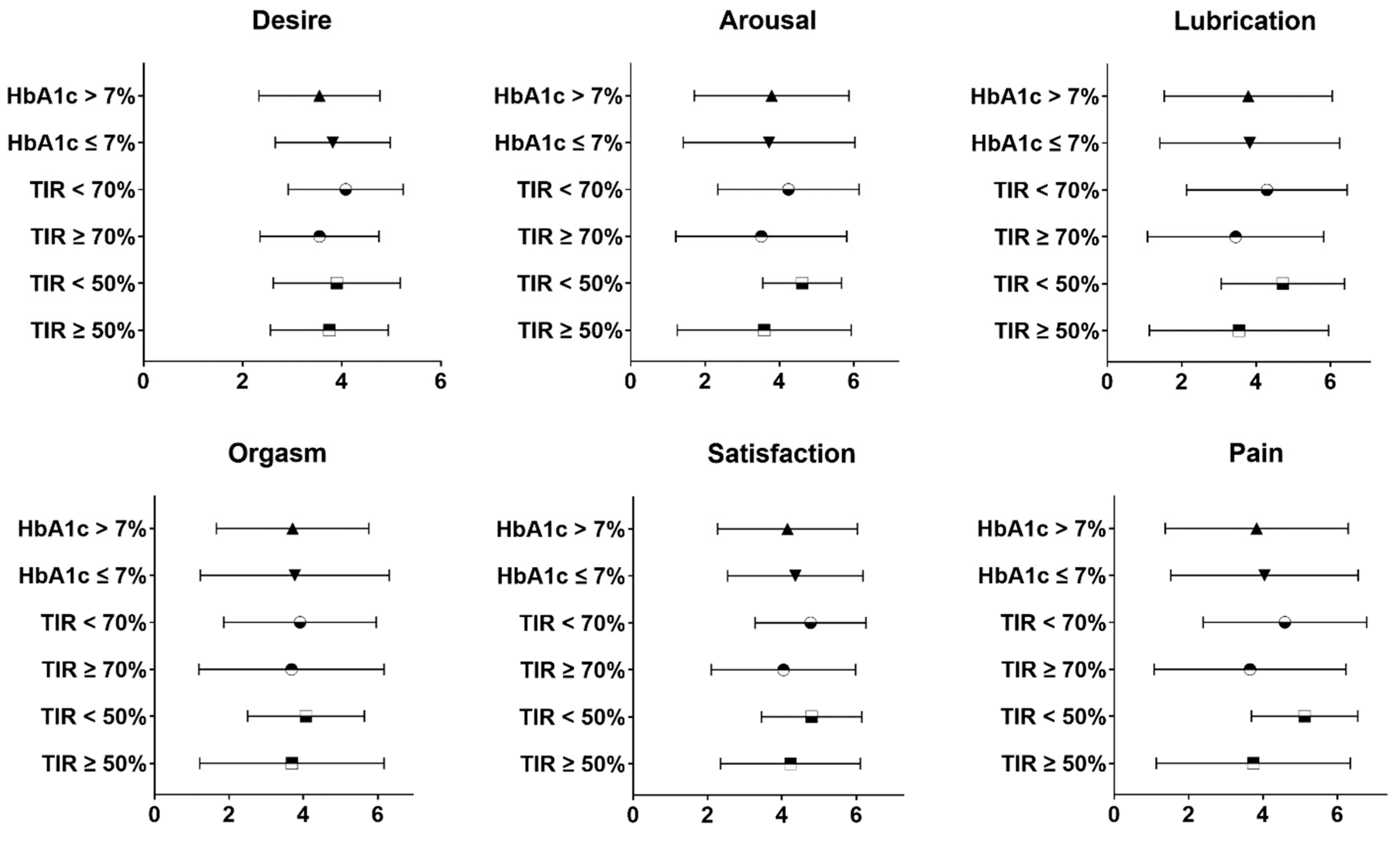

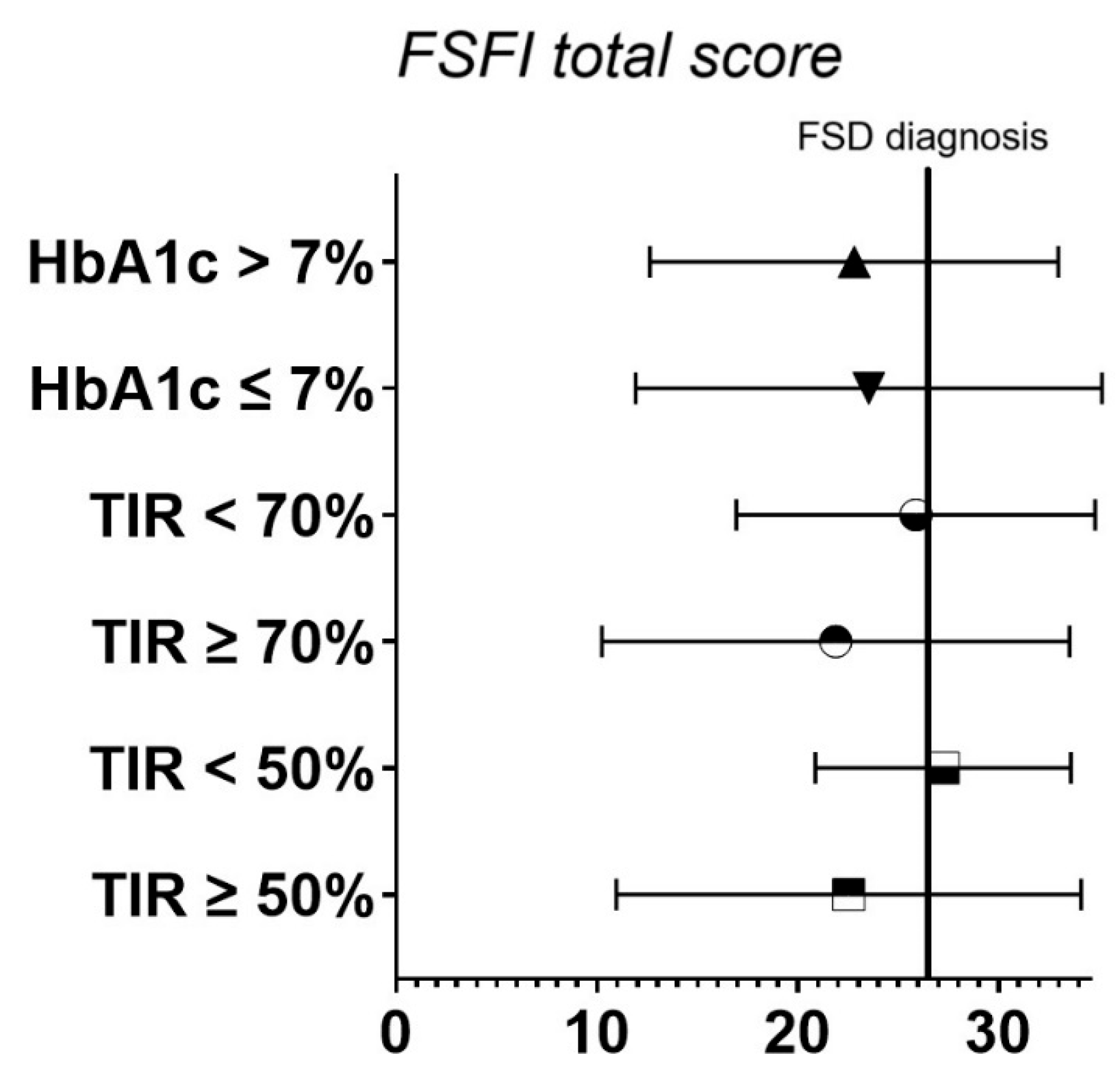

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| T1D | Type 1 diabetes |

| T2D | Type 2 diabetes |

| MDI | Multiple Daily Injection |

| CSII | Continuous Subcutaneous Insulin Infusion |

| c-CSII | Continuous Subcutaneous Insulin Infusion with catheter |

| pp-CSII | Continuous Subcutaneous Insulin Infusion with patch pump |

| AHCL | Advanced Hybrid Close Loop |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

| ADA | American Diabetes Association |

| FSFI | Female Sexual Function Index |

| FSD | Female sexual dysfunctions |

| CGM | Continuous Glucose Monitoring |

| TIR | Time In Range |

| TAR | Time Above Range |

| TBR | Time Below Range |

| HbA1c | Glycated haemoglobin |

References

- Narasimhan, M.; Logie, C.H.; Gauntley, A.; Gomez Ponce de Leon, R.; Gholbzouri, K.; Siegfried, N.; Abela, H.; Ouedraogo, L. Self-care interventions for sexual and reproductive health and rights for advancing universal health coverage. Sex. Reprod. Health Matters 2020, 28, 1778610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCabe, M.P.; Sharlip, I.D.; Atalla, E.; Balon, R.; Fisher, A.D.; Laumann, E.; Lee, S.W.; Lewis, R.; Segraves, R.T. Definitions of Sexual Dysfunctions in Women and Men: A Consensus Statement From the Fourth International Consultation on Sexual Medicine 2015. J. Sex. Med. 2016, 13, 135–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lewis, R.W.; Fugl-Meyer, K.S.; Corona, G.; Hayes, R.D.; Laumann, E.O.; Moreira, E.D.; Rellini, A.H., Jr.; Segraves, T. Definitions/epidemiology/risk factors for sexual dysfunction. J. Sex. Med. 2010, 7, 1598–1607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Stasi, V.; Maseroli, E.; Vignozzi, L. Female Sexual Dysfunction in Diabetes: Mechanisms, Diagnosis and Treatment. Curr. Diabetes Rev. 2022, 18, e171121198002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bassi, M.; Franzone, D.; Dufour, F.; Strati, M.F.; Scalas, M.; Tantari, G.; Aloi, C.; Salina, A.; d’Annunzio, G.; Maghnie, M.; et al. Automated Insulin Delivery (AID) Systems: Use and Efficacy in Children and Adults with Type 1 Diabetes and Other Forms of Diabetes in Europe in Early 2023. Life 2023, 13, 783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battelino, T.; Danne, T.; Bergenstal, R.M.; Amiel, S.A.; Beck, R.; Biester, T.; Bosi, E.; Buckingham, B.A.; Cefalu, W.T.; Close, K.L.; et al. Clinical Targets for Continuous Glucose Monitoring Data Interpretation: Recommendations From the International Consensus on Time in Range. Diabetes Care 2019, 42, 1593–1603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pantanetti, P.; Cangelosi, G.; Morales Palomares, S.; Ferrara, G.; Biondini, F.; Mancin, S.; Caggianelli, G.; Parozzi, M.; Sguanci, M.; Petrelli, F. Real-World Life Analysis of a Continuous Glucose Monitoring and Smart Insulin Pen System in Type 1 Diabetes: A Cohort Study. Diabetology 2025, 6, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzilli, R.; Imbrogno, N.; Elia, J.; Delfino, M.; Bitterman, O.; Napoli, A.; Mazzilli, F. Sexual dysfunction in diabetic women: Prevalence and differences in type 1 and type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Obes. Targets Ther. 2015, 8, 97–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, M.R.; Shaaban, M.M.; Sedik, W.F.; Mohamed, T.Y. Prevalence and differences between type 1 and type 2 diabetes mellitus regarding female sexual dysfunction: A cross-sectional Egyptian study. J. Psychosom. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2018, 39, 176–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashim, R.; Forde, R.; Ausili, D.; Forbes, A. Prevalence and associated factors of sexual dysfunction in premenopausal women with type 1 diabetes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabet. Med. 2023, 40, e15173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esposito, K.; Maiorino, M.I.; Bellastella, G.; Giugliano, F.; Romano, M.; Giugliano, D. Determinants of female sexual dysfunction in type 2 diabetes. Int. J. Impot. Res. 2010, 22, 179–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wessells, H.; Braffett, B.H.; Holt, S.K.; Jacobson, A.M.; Kusek, J.W.; Cowie, C.; Dunn, R.L.; Sarma, A.V.; DCCT/EDIC Study Group. Burden of Urological Complications in Men and Women With Long-standing Type 1 Diabetes in the Diabetes Control and Complications Trial/Epidemiology of Diabetes Interventions and Complications Cohort. Diabetes Care 2018, 41, 2170–2177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashim, R.; Forbes, A. Sexual dysfunction, an invisible complication of diabetes—An exploratory study of the experiences of premenopausal women with Type 1 diabetes. Int. Diabetes Nurs. 2022, 15, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tagliabue, M.; Gottero, C.; Zuffranieri, M.; Negro, M.; Carletto, S.; Picci, R.L.; Tomelini, M.; Bertaina, S.; Pucci, E.; Trento, M.; et al. Sexual function in women with type 1 diabetes matched with a control group: Depressive and psychosocial aspects. J. Sex. Med. 2011, 8, 1694–1700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maiorino, M.I.; Bellastella, G.; Castaldo, F.; Petrizzo, M.; Giugliano, D.; Esposito, K. Sexual function in young women with type 1 diabetes: The METRO study. J. Endocrinol. Investig. 2017, 40, 169–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamponi, V.; Mazzilli, R.; Bitterman, O.; Olana, S.; Iorio, C.; Festa, C.; Giuliani, C.; Mazzilli, F.; Napoli, A. Association between type 1 diabetes and female sexual dysfunction. BMC Women’s Health 2020, 20, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riveline, J.P.; Franc, S.; Biedzinski, M.; Jollois, F.X.; Messaoudi, N.; Lagarde, F.; Lormeau, B.; Pichard, S.; Varroud-Vial, M.; Deburge, A.; et al. Sexual activity in diabetic patients treated by continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion therapy. Diabetes Metab. 2010, 36, 229–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enzlin, P.; Rosen, R.; Wiegel, M.; Brown, J.; Wessells, H.; Gatcomb, P.; Rutledge, B.; Chan, K.L.; Cleary, P.A.; DCCT/EDIC Research Group. Sexual dysfunction in women with type 1 diabetes: Long-term findings from the DCCT/ EDIC study cohort. Diabetes Care 2009, 32, 780–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enzlin, P.; Mathieu, C.; Van Den Bruel, A.; Vanderschueren, D.; Demyttenaere, K. Prevalence and predictors of sexual dysfunction in patients with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2003, 26, 409–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skrivankova, V.W.; Richmond, R.C.; Woolf, B.A.R.; Davies, N.M.; Swanson, S.A.; VanderWeele, T.J.; Timpson, N.J.; Higgins, J.P.T.; Dimou, N.; Langenberg, C.; et al. Strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology using mendelian randomisation (STROBE-MR): Explanation and elaboration. BMJ 2021, 375, n2233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Diabetes Association Professional Practice Committee. 2. Diagnosis and Classification of Diabetes: Standards of Care in Diabetes-2025. Diabetes Care 2025, 48 (Suppl. 1), S27–S49. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosen, R.; Brown, C.; Heiman, J.; Leiblum, S.; Meston, C.; Shabsigh, R.; Ferguson, D.; D’Agostino, R., Jr. The Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI): A multidimensional self-report instrument for the assessment of female sexual function. J. Sex Marital Ther. 2000, 26, 191–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Filocamo, M.T.; Serati, M.; Li Marzi, V.; Costantini, E.; Milanesi, M.; Pietropaolo, A.; Polledro, P.; Gentile, B.; Maruccia, S.; Fornia, S.; et al. The Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI): Linguistic validation of the Italian version. J. Sex. Med. 2014, 11, 447–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American Diabetes Association Professional Practice Committee. 6. Glycemic Goals and Hypoglycemia: Standards of Care in Diabetes-2025. Diabetes Care 2025, 48 (Suppl. 1), S128–S145. [CrossRef]

- Isidori, A.M.; Pozza, C.; Esposito, K.; Giugliano, D.; Morano, S.; Vignozzi, L.; Corona, G.; Lenzi, A.; Jannini, E.A. Development and validation of a 6-item version of the female sexual function index (FSFI) as a diagnostic tool for female sexual dysfunction. J. Sex. Med. 2010, 7, 1139–1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Earle, S.; Blackburn, M. Young adults with life-limiting or life-threatening conditions: Sexuality and relationships support. BMJ Support. Palliat. Care 2021, 11, 163–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Total (n = 77) | MDI (n = 16) | c-CSII (n = 45) | pp-CSII (n = 16) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FSFI domains | ||||

| Desire | 3.69 ± 1.22 | 3.60 ± 1.10 | 3.73 ± 1.21 | 3.64 ± 1.44 |

| Arousal | 3.75 ± 2.18 | 4.22 ± 1.85 | 3.76 ± 2.24 | 3.26 ± 2.38 |

| Lubrication | 3.76 ± 2.32 | 4.27 ± 2.07 | 3.81 ± 2.36 | 3.13 ± 2.48 |

| Orgasm | 3.65 ± 2.32 | 4.12 ± 2.12 | 3.68 ± 2.37 | 3.10 ± 2.38 |

| Satisfaction | 4.25 ± 1.83 | 4.22 ± 1.55 | 4.40 ± 1.87 | 3.87 ± 2.04 |

| Pain | 3.93 ± 2.46 | 4.32 ± 2.00 | 4.11 ± 2.47 | 3.02 ± 2.76 |

| FSFI total score | 23.04 ± 10.95 | 24.77 ± 9.58 | 23.49 ± 11.23 | 20.03 ± 11.51 |

| FSD diagnosis | ||||

| Yes | 38 (49.3) | 8 (50) | 20 (44.4) | 10 (62.5) |

| No | 39 (50.7) | 8 (50) | 25 (55.6) | 6 (37.5) |

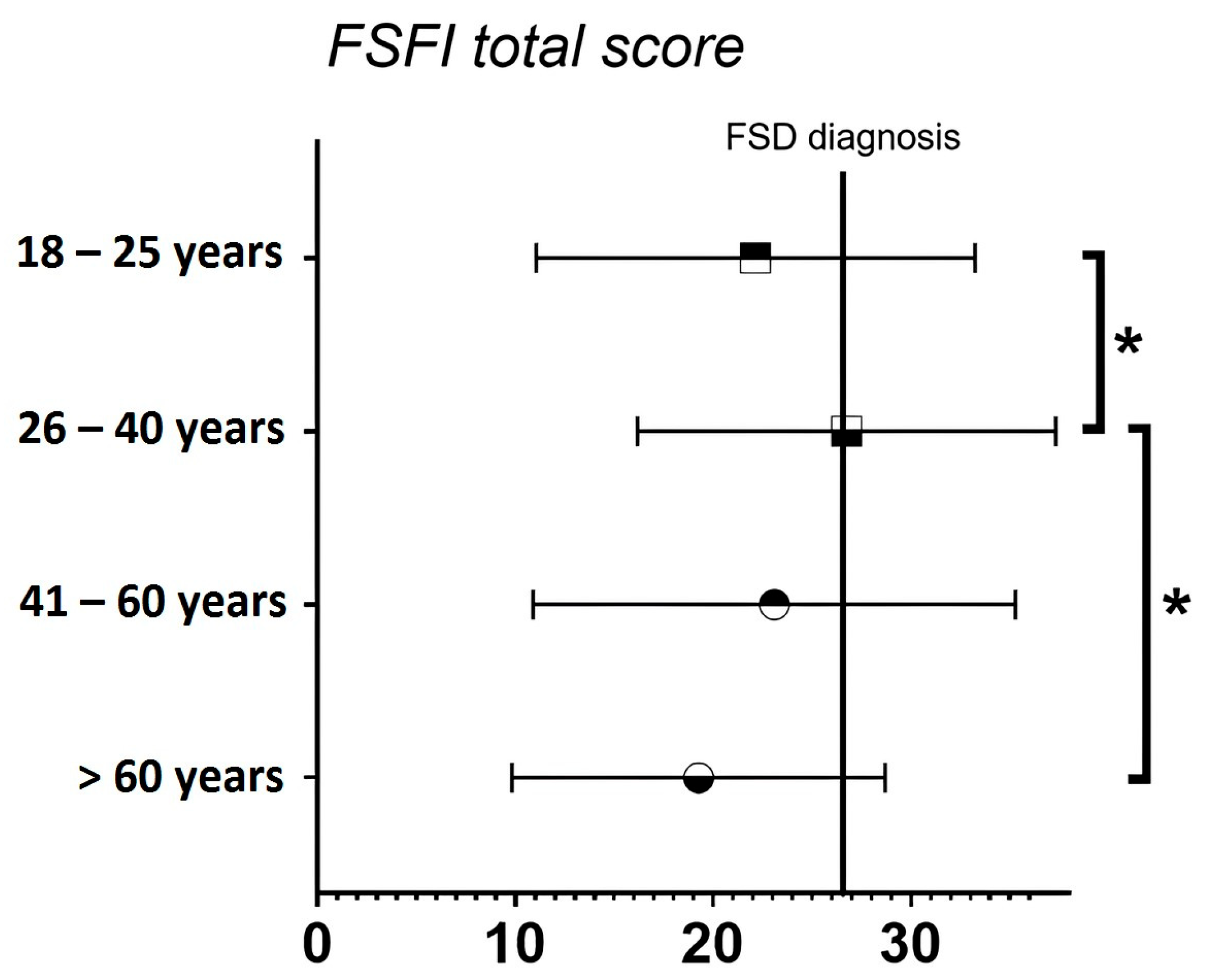

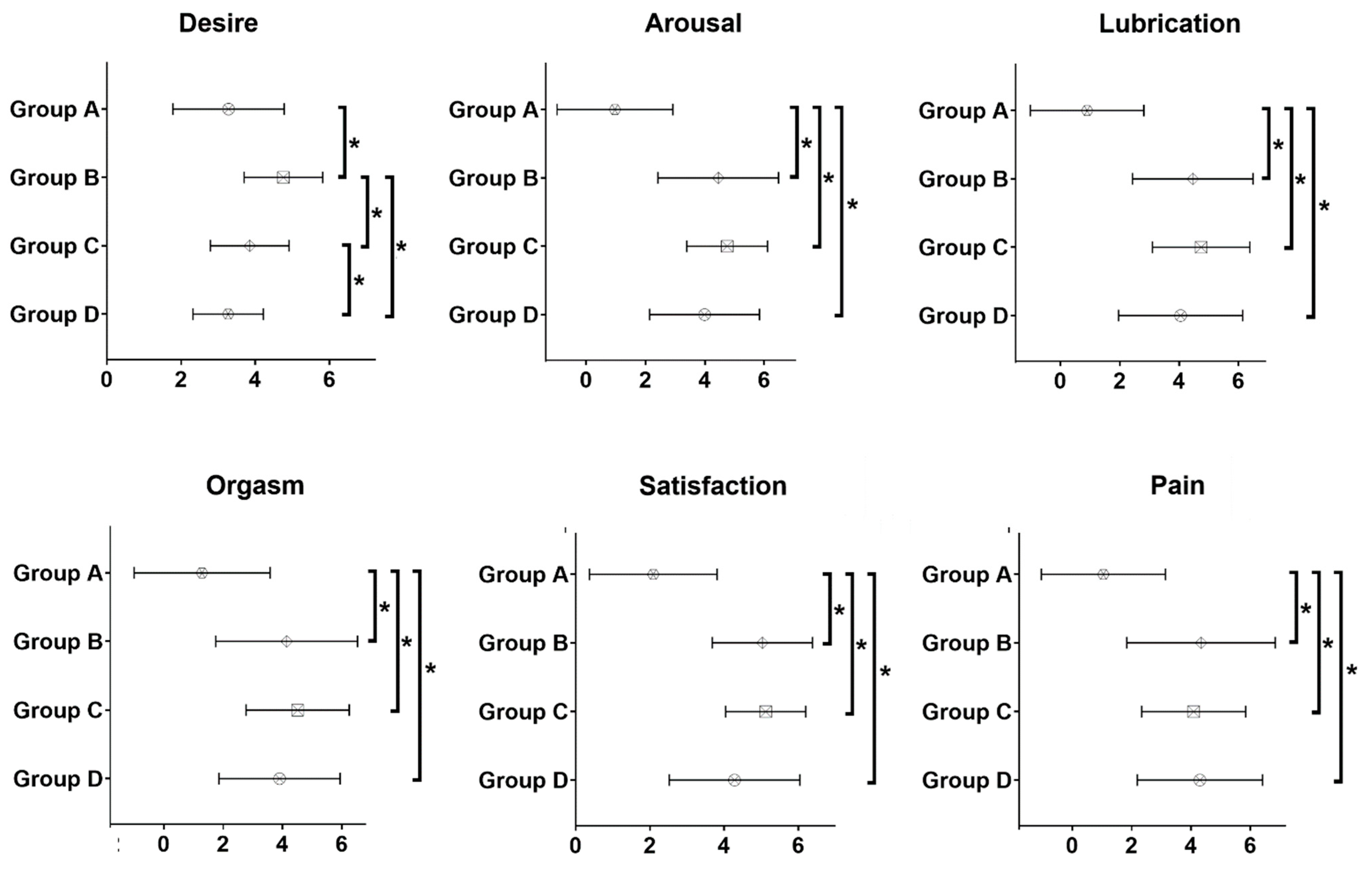

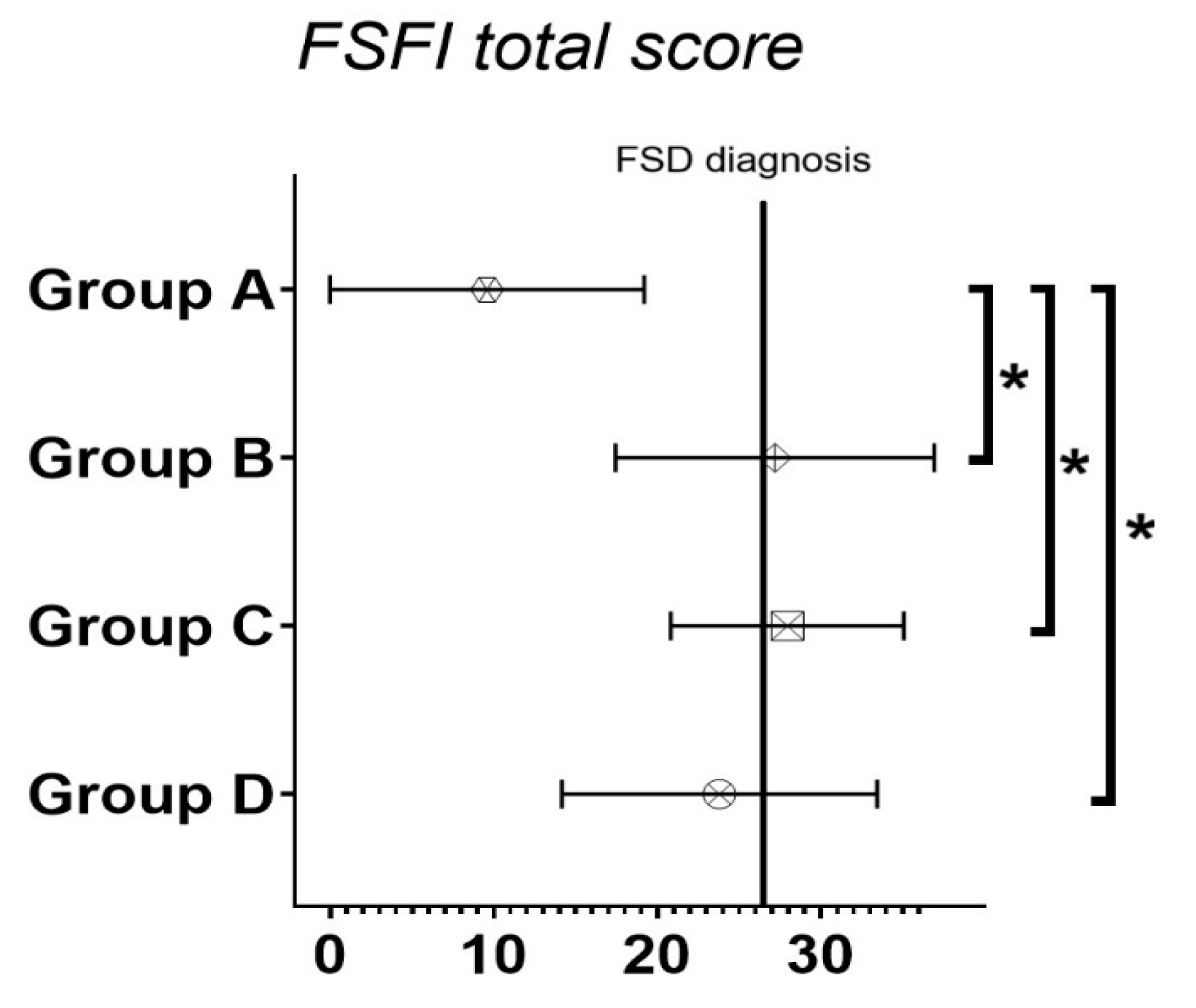

| Age 18–25 Years (n = 41) | Age 26–40 Years (n = 19) | Age 41–60 Years (n = 8) | Age > 60 Years (n = 9) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FSFI domains | ||||

| Desire *☐s | 3.94 ± 1.24 | 3.73 ± 1.32 | 3.53 ± 0.75 | 2.60 ± 0.67 |

| Arousal | 3.64 ± 2.35 | 4.29 ± 2.03 | 3.53 ± 2.26 | 3.30 ± 1.77 |

| Lubrication | 3.45 ± 2.37 | 4.48 ± 2.13 | 3.94 ± 2.54 | 3.53 ± 2.34 |

| Orgasm ☐ | 3.36 ± 2.45 | 4.51 ± 2.14 | 3.80 ± 2.43 | 3.07 ± 1.77 |

| Satisfaction ☐ | 4.30 ± 1.79 | 4.80 ± 1.73 | 3.95 ± 2.12 | 3.16 ± 1.75 |

| Pain | 3.45 ± 2.62 | 4.93 ± 1.90 | 4.35 ± 2.72 | 3.60 ± 2.15 |

| FSFI total score | 22.14 ± 11.10 | 26.74 ± 10.57 | 23.09 ± 12.19 | 19.26 ± 9.44 |

| FSD diagnosis ☐T | ||||

| Yes | 23 (56.1) | 5 (26.3) | 3 (37.5) | 7 (77.8) |

| No | 18 (43.9) | 14 (73.7) | 5 (63.5) | 2 (22.2) |

| Menopausal Status (n = 12) | No Menopausal Status (n = 65) | Use of Estro-Progestinic (n = 25) | No Use of Estro-Progestinic (n = 52) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FSFI domains | ||||

| Desire * | 2.85 ± 0.81 | 3.84 ± 1.23 | 3.48 ± 0.98 | 3.78 ± 1.32 |

| Arousal | 3.55 ± 1.60 | 3.79 ± 2.29 | 4.15 ± 1.77 | 3.56 ± 2.35 |

| Lubrication | 3.85 ± 2.11 | 3.75 ± 2.38 | 4.20 ± 1.95 | 3.55 ± 2.48 |

| Orgasm | 3.67 ± 1.80 | 3.65 ± 2.41 | 3.87 ± 2.13 | 3.55 ± 2.42 |

| Satisfaction * | 3.47 ± 1.65 | 4.40 ± 1.84 | 4.75 ± 1.22 | 4.02 ± 2.03 |

| Pain | 4.23 ± 2.14 | 3.87 ± 2.52 | 4.51 ± 1.79 | 3.65 ± 2.69 |

| FSFI total score | 21.62 ± 9.18 | 23.30 ± 11.29 | 24.97 ± 8.84 | 22.11 ± 11.80 |

| FSD diagnosis | ||||

| Yes | 7 (58.3) | 31 (47.7) | 11 (44.0) | 27 (51.9) |

| No | 5 (41.7) | 34 (52.3) | 14 (56.0) | 25 (48.1) |

| “Have You Ever Experienced a Hypoglycaemic Event During Intercourse?” | “No” (n = 24) | “Sometimes/Most of the Times” (n = 44) | “No” vs. “Sometimes/Most of the Times” * |

|---|---|---|---|

| FSFI domains | |||

| Desire | 3.13 ± 1.24 | 4.00 ± 1.15 | <0.01 |

| Arousal | 3.26 ± 2.31 | 4.19 ± 1.99 | 0.06 |

| Lubrication | 3.51 ± 2.63 | 4.17 ± 2.13 | 0.42 |

| Orgasm | 3.33 ± 2.42 | 3.94 ± 2.22 | 0.22 |

| Satisfaction | 3.68 ± 2.07 | 4.78 ± 1.54 | 0.03 |

| Pain | 3.87 ± 2.72 | 4.40 ± 2.07 | 0.78 |

| FSFI total score | 20.78 ± 12.56 | 25.48 ± 9.83 | 0.13 |

| FSD diagnosis | 0.82 | ||

| Yes | 13 (54.2) | 25 (56.8) | |

| No | 11 (45.8) | 19 (43.2) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Petolicchio, C.; Spacco, G.; Delle Chiaie, E.; Calevo, M.G.; Minuto, N.; Maggi, D.C.; Ferone, D.; Bassi, M.; Cocchiara, F. Glycometabolic Control Does Not Affect Sexual Function in a Cohort of Women with Type 1 Diabetes: Results of an Observational Pilot Study. Endocrines 2025, 6, 25. https://doi.org/10.3390/endocrines6020025

Petolicchio C, Spacco G, Delle Chiaie E, Calevo MG, Minuto N, Maggi DC, Ferone D, Bassi M, Cocchiara F. Glycometabolic Control Does Not Affect Sexual Function in a Cohort of Women with Type 1 Diabetes: Results of an Observational Pilot Study. Endocrines. 2025; 6(2):25. https://doi.org/10.3390/endocrines6020025

Chicago/Turabian StylePetolicchio, Cristian, Giordano Spacco, Eliana Delle Chiaie, Maria Grazia Calevo, Nicola Minuto, Davide Carlo Maggi, Diego Ferone, Marta Bassi, and Francesco Cocchiara. 2025. "Glycometabolic Control Does Not Affect Sexual Function in a Cohort of Women with Type 1 Diabetes: Results of an Observational Pilot Study" Endocrines 6, no. 2: 25. https://doi.org/10.3390/endocrines6020025

APA StylePetolicchio, C., Spacco, G., Delle Chiaie, E., Calevo, M. G., Minuto, N., Maggi, D. C., Ferone, D., Bassi, M., & Cocchiara, F. (2025). Glycometabolic Control Does Not Affect Sexual Function in a Cohort of Women with Type 1 Diabetes: Results of an Observational Pilot Study. Endocrines, 6(2), 25. https://doi.org/10.3390/endocrines6020025