Impact of the European–Mediterranean Postgraduate Program on Organ Donation and Transplantation (EMPODaT): A Survey Analysis at 6 Years

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design and Study Population

2.2. Study Procedures

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Study Participants

3.2. Impact of the EMPODaT Project on Healthcare Professionals

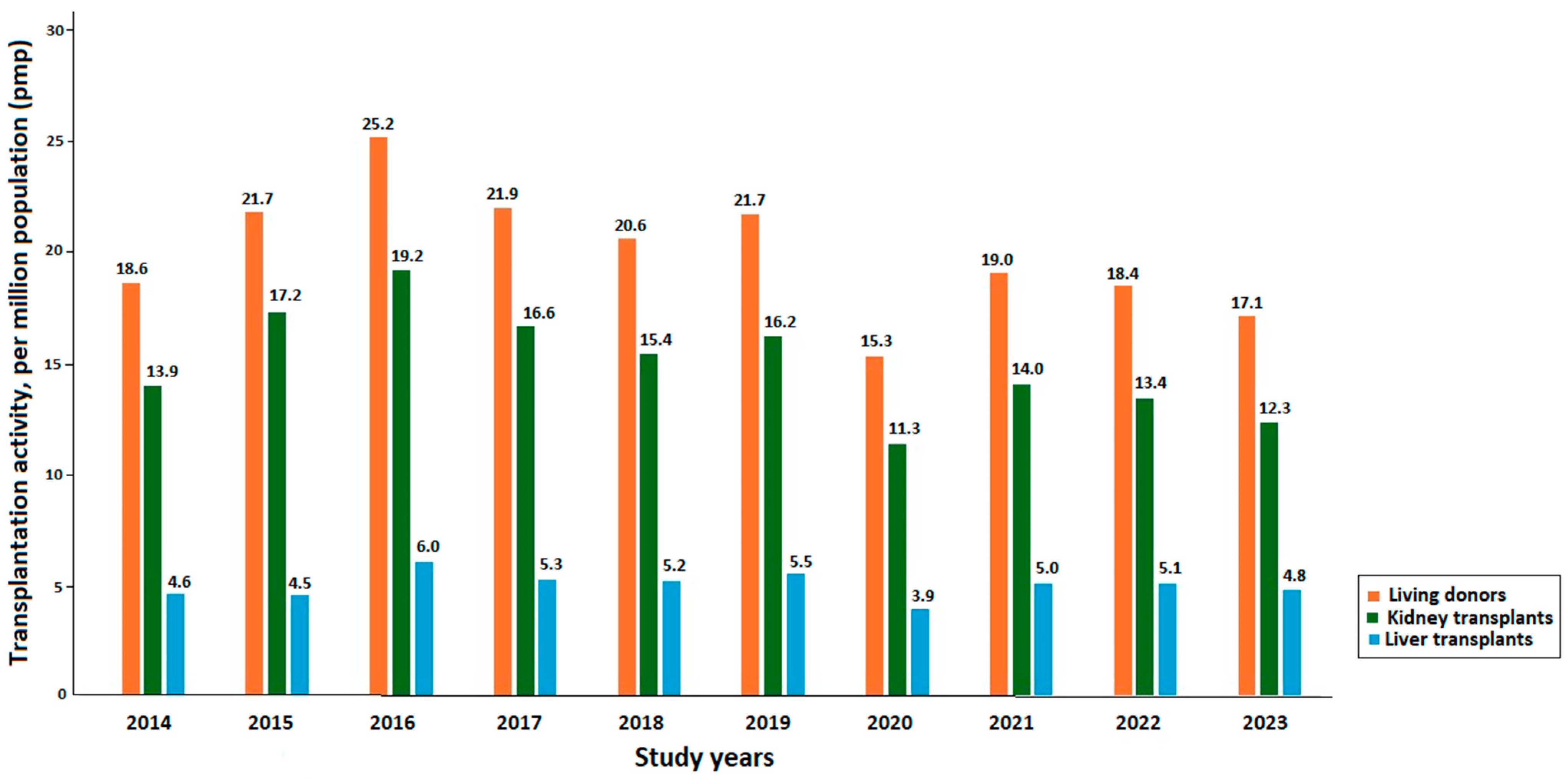

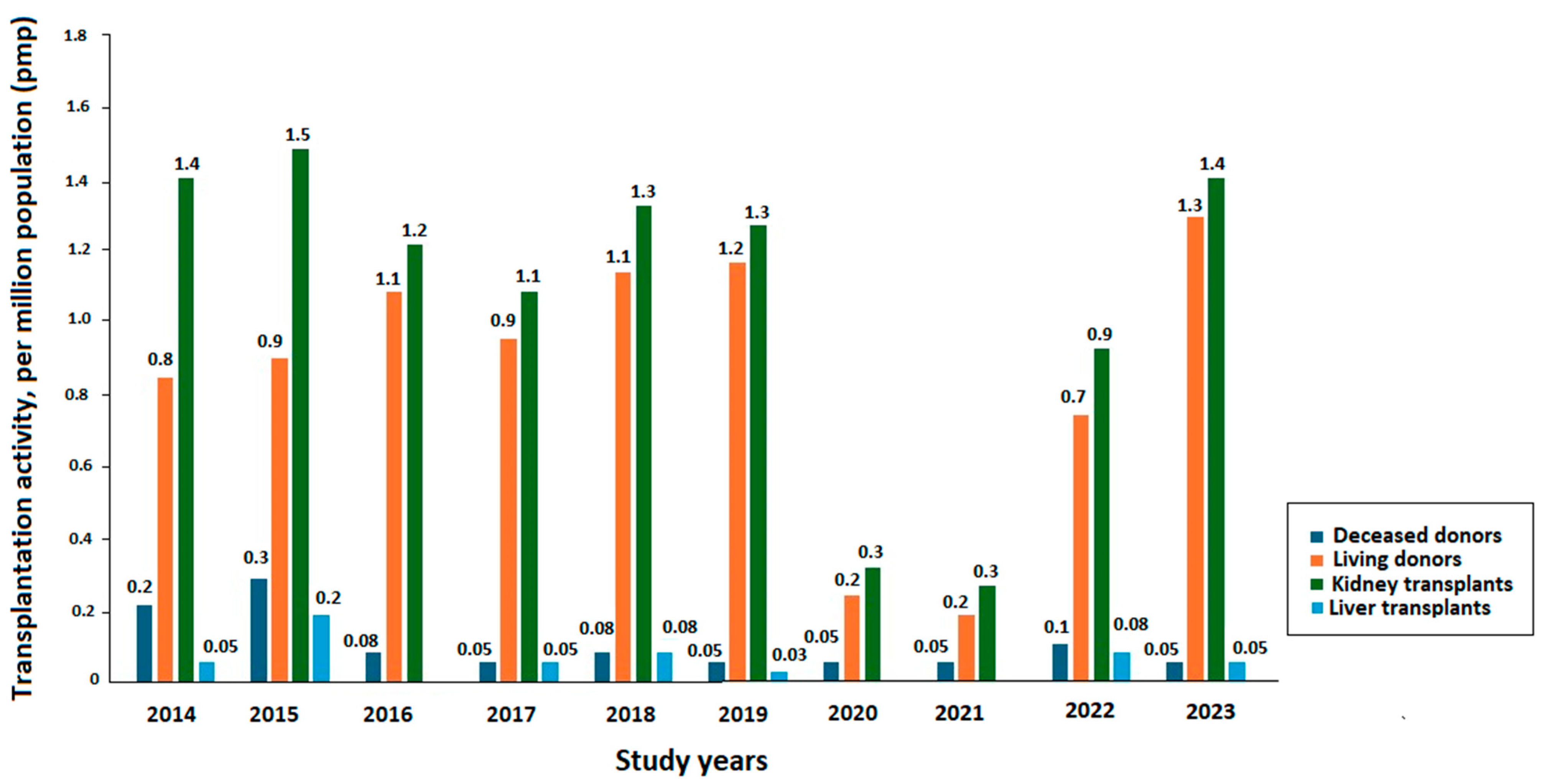

3.3. Evolution of ODT Activities at the National Level

4. Discussion

4.1. Limitations of the Study

4.2. Practical Implications and Future Research

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| EMPODaT | European–Mediterranean Postgraduate Program on Organ Donation and Transplantation |

| CCTOTH | Conseil Consultatif de Transplantation d’Organes et de Tissus Humains du Maroc |

| CI | Confidence interval |

| EACEA | Education, Audio–Visual and Culture Executive Agency |

| GODT | Global Observatory on Donation and Transplantation |

| IRODaT | International Registry on Organ Donation and Transplantation |

| MENA | Middle East/North Africa |

| MOHP | Ministry of Health and Population of Egypt |

| NOD | National Organization of Organ and Tissue Donation and Transplantation of Lebanon |

| ODT | Organ Donation and Transplantation |

| OR | Odds Ratio |

| SD | Standard Deviation |

| SPSS | Statistical Package for the Social Sciences |

| TPM | Transplant Procurement Management |

Appendix A

References

- Pullen, L.C. Creating an International Standard: Global Convergence in Transplantation. Am. J. Transplant. 2024, 24, 151–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pullen, L.C. World Health Assembly resolution: A global path forward in transplantation. Am. J. Transplant. 2024, 24, 1521–1523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnston-Webber, C.; Wharton, G.; Mossialos, E.; Papalois, V. Maximising potential in organ donation and transplantation: Transferrable paradigms. Transpl. Int. 2023, 35, 11005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, A.; Koukoura, A.; Tsianos, G.I.; Gargavanis, A.A.; Nielsen, A.A.; Vassiliadis, E. Organ donation in the US and Europe: The supply vs demand imbalance. Transpl. Rev. 2012, 35, 100585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manyalich, M.; Guasch, X.; Paez, G.; Valero, R.; Istrate, M. ETPOD (European Training Program on Organ Donation): A successful training program to improve organ donation. Transpl. Int. 2013, 26, 373–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Istrate, M.G.; Harrison, T.R.; Valero, R.; Morgan, S.E.; Páez, G.; Zhou, Q.; Rébék-Nagy, G.; Manyalich, M. Benefits of Transplant Procurement Management (TPM) specialized training on professional competence development and career evolutions of health care workers in organ donation and transplantation. Exp. Clin. Transpl. 2015, 13 (Suppl. S1), 148–155. [Google Scholar]

- Rowe, A.K.; Rowe, S.Y.; Peters, D.H.; Holloway, K.A.; Ross-Degnan, D. The effectiveness of training strategies to improve healthcare provider practices in low-income and middle-income countries. BMJ Glob. Health 2021, 61, e003229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballesté, C.; Valero, R.; Istrate, M.; Peralta, P.; Mosharafa, A.A.; Morsy, A.A.; Bakr, M.A.; Kamal Abdelkader, A.I.; Sheashaa, H.; Juvelekian, G.S.; et al. Design and implementation of the European-Mediterranean Postgraduate Programme on Organ Donation and Transplantation (EMPODaT) for Middle East/North Africa countries. Transpl. Int. 2021, 34, 1553–1565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Registry of Organ Donation and Transplantation (IRODaT). Available online: https://www.irodat.org/ (accessed on 12 January 2024).

- Global Observatory on Donation and Transplantation (GODT). Available online: https://www.transplant-observatory.org/ (accessed on 12 January 2024).

- Mery, G.; Dobrow, M.J.; Baker, G.R.; Im, J.; Brown, A. Evaluating investment in quality improvement capacity building: A systematic review. BMJ Open 2017, 7, e012431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Austin, J.M.; Kachalia, A. The state of health care quality measurement in the era of COVID-19: The importance of doing better. JAMA 2020, 324, 333–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Worsley, C.; Webb, S.; Vaux, E. Training healthcare professionals in quality improvement. Future Hosp. J. 2016, 3, 207–2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleh, A.; Bista, K. Examining factors impacting online survey response rates in educational research: Oerceptions of graduate students. J. Multidiscip. Eval. 2017, 13, 63–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, S.R.; Umbach, P.D. Student survey response rates across institutions: Why do they vary? Res. High. Educ. 2006, 47, 229–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peralta, P.; Istrate, M.; Ballesté, C.; Manyalich, M.; Valero, R.; EUDONORGAN Consortium. “Train the Trainers” program to improve knowledge, attitudes and perceptions about organ donation in the European Union and neighbouring countries: Pre- and post-data analysis of the EUDONORGAN Project. Transpl. Int. 2023, 36, 10878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khurshid, Z.; De Brún, A.; McAuliffe, E. Factors influencing measurement for improvement skills in healthcare staff: Trainee, and trainer perspectives. BMC Med. Educ. 2022, 22, 236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva e Silva, V.; Schirmer, J.; Roza, B.D.; de Oliveira, P.C.; Dhanani, S.; Almost, J.; Schafer, M.; Tranmer, J. Defining quality criteria for success in organ donation programs: A scoping review. Can. J. Kidney Health Dis. 2021, 8, 2054358121992921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Streit, S.; Johnston-Webber, C.; Mah, J.; Prionas, A.; Wharton, G.; Casanova, D.; Mossialos, E.; Papalois, V. Ten lessons from the Spanish model of organ donation and transplantation. Transpl. Int. 2013, 36, 11009c. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nulty, D.D. The adequacy of response rates to online and paper surveys: What can be done? Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 2008, 33, 301–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshikawa, M.; Yoshinaga, K.; Imamura, Y.; Hayashi, T.; Osako, T.; Takahashi, K.; Kaneko, M.; Fujisawa, M.; Kamidono, S. Transplant procurement management model training: Marked improvement in the mindset of in-hospital procurement coordinators at Hyogo Prefecture, Japan. Transplant. Proc. 2016, 48, 2437–2441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston-Webber, C.; Mah, J.; Streit, S.; Prionas, A.; Wharton, G.; Mossialos, E.; Papalois, V. A conceptual framework for evaluating national organ donation and transplantation programs. Transpl Int. 2023, 36, 11006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanholder, R.; Domínguez-Gil, B.; Busic, M.; Cortez-Pinto, H.; Craig, J.C.; Jager, K.J.; Mahillo, B.; Stel, V.S.; Valentin, M.O.; Zoccali, C.; et al. Organ donation and transplantation: A multi-stakeholder call to action. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 2021, 17, 554–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delmonico, F.L.; Domínguez-Gil, B.; Matesanz, R.; Noel, L. A call for government accountability to achieve national self-sufficiency in organ donation and transplantation. Lancet 2011, 378, 1414–1418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castillo-Angeles, M.; Li, G.; Bain, P.A.; Stinebring, J.; Salim, A.; Adler, J.T. Systematic review of hospital-level metrics and interventions to increase deceased organ donation. Transpl. Rev. 2021, 35, 100613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anhang Price, R.; Quigley, D.D.; Hargraves, J.L.; Sorra, J.; Becerra-Ornelas, A.U.; Hays, R.D.; Cleary, P.D.; Brown, J.; Elliott, M.N. A Systematic review of strategies to enhance response rates and representativeness of patient experience surveys. Med. Care 2022, 60, 910–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- West, B.T.; Zhang, S.; Wagner, J.; Gatward, R.; Saw, H.W.; Axinn, W.G. Methods for improving participation rates in national self-administered web/mail surveys: Evidence from the United States. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0289695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sammut, R.; Griscti, O.; Norman, I.J. Strategies to improve response rates to web surveys: A literature review. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2021, 123, 104058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristics | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Male | 12 (52.2) |

| Female | 11 (47.8) |

| Country of residence | |

| Egypt | 12 (52.2) |

| Lebanon | 5 (21.7) |

| Morocco | 6 (26.1) |

| Highest level of education | |

| Undergraduate | 2 (8.7) |

| PhD | 21 (91.3) |

| Specialty | |

| Nephrology | 13 (56.5) |

| Intensive care medicine/ Anesthesiology | 3 (13.0) |

| Hepatology | 2 (8.6) |

| Abdominal surgery | 1 (4.3) |

| Immunology | 1 (4.3) |

| Thoracic surgery | 1 (4.3) |

| Ophthalmology | 1 (4.3) |

| Urology | 1 (4.3) |

| Experience in ODT prior to the EMPODaT training program | |

| 0–5 years | 6 (26.1) |

| 6–10 years | 11 (47.8) |

| 11–15 years | 3 (13.0) |

| 16–20 years | 2 (8.7) |

| More than 20 years | 1 (4.3) |

| Active in ODT | |

| No | 6 (26.1) |

| Yes | 17 (73.9) |

| Questions | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Q10: What roles have you held since receiving EMPODaT training? | |

| None related to ODT | 2 (8.7) |

| Healthcare professionals related to ODT | 18 (78.3) |

| Junior donor coordinator | 1 (4.3) |

| Senior donor coordinator | 3 (13) |

| Local director/manager in ODT | 4 (14.4) |

| Q16: Have you achieved any improvements in organ donation and transplantation policies in your region or country? | |

| Yes | 15 (65.2) |

| No | 8 (34.8) |

| Q17: What kind of improvements have been achieved in terms of organ donation and transplantation policy? | |

| Changes in hospital | 16 (69.7) |

| Changes in regional | 5 (21.7) |

| Changes in national | 4 (17.4) |

| None | 6 (26) |

| Q18: Have you achieved any improvements in organ donation and transplantation practices or processes in your region or country? | |

| Yes | 15 (65.2) |

| No | 8 (34.8) |

| Q19: What kind of improvements have been achieved in terms of organ donation and transplantation practices or processes? | |

| Donor screening system | 9 (39.1) |

| Brain death diagnosis | 7 (30.4) |

| Donor maintenance | 3 (13) |

| Family interview for donation | 3 (13) |

| Donor procurement organization | 4 (17.4) |

| Organization of ODT office | 7 (30.4) |

| Setting up laws and rules of ODT | 1 (4.3) |

| None | 6 (26) |

| Q28: To what extent has your hospital, organization, or country been responsive to changes that you or others in your training group have tried to implement? | |

| Totally sensitive | 3 (13) |

| Sensitive | 9 (39.1) |

| Neither sensitive nor insensitive | 5 (21.7) |

| Insensitive | 4 (17.4) |

| Q29: Have you trained other professionals using the techniques you learned in the EMPODaT training? | |

| Yes | 16 (69.6) |

| No | 7 (30.4) |

| Questions | Degree of Perceived Impact, N (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No Influence | Very Little | Moderate | Significant | |

| Q20: Assess the degree to which you believe the EMPODaT training has impacted each of the following aspects in your hospital/organization/country | ||||

| Changes in policy | 4 (17.4) | 2 (8.7) | 7 (30.4) | 10 (43.5) |

| Donor screening system | 3 (13.0) | 4 (17.4) | 6 (26.1) | 10 (43.5) |

| Brain death diagnosis | 4 (17.4) | 3 (13.0) | 6 (26.1) | 10 (43.5) |

| Donor maintenance | 4 (17.4) | 5 (21.7) | 6 (26.1) | 8 (34.8) |

| Family interview for donation | 4 (17.4) | 5 (21.7) | 6 (26.1) | 8 (34.8) |

| Donor procurement organization | 6 (26.1) | 2 (8.7) | 8 (34.8) | 7 (30.4) |

| Organization of the ODT office | 6 (26.1) | 1 (4.3) | 10 (43.5) | 6 (26.1) |

| Q23: Rate the extent to which you believe the EMPODaT training has influenced your personal experience | ||||

| Respect from peers | - | 2 (8.7) | 10 (43.5) | 11 (47.8) |

| Advantages in career advancement | 2 (8.7) | 4 (17.4) | 9 (39.1) | 8 (34.8) |

| Technical skills for ODT | - | 3 (13.0) | 9 (39.1) | 11 (47.8) |

| Networking skills | - | 1 (4.3) | 5 (21.7) | 17 (73.9) |

| Attitude towards ODT | 1 (4.3) | 5 (21.7) | 9 (39.1) | 8 (34.8) |

| Motivation to work in the field of ODT | - | 2 (8.7) | 7 (30.4) | 14 (60.9) |

| Opportunities for collaboration in ODT | 1 (4.3) | 1 (4.3) | 5 (21.7) | 16 (69.6) |

| Ability to change ODT practices | 1 (4.3) | 6 (26.1) | 7 (30.4) | 9 (39.1) |

| Ability to change ODT policies | 2 (8.7) | 3 (13.0) | 9 (39.1) | 9 (39.1) |

| Desire to innovate in the field of ODT | 4 (17.4) | 5 (21.7) | 5 (21.7) | 9 (39.1) |

| Communication skills related to ODT | 1 (4.3) | 2 (8.7) | 6 (26.1) | 14 (60.9) |

| Q27: In what areas do you feel the EMPODaT training has helped you to influence improvement or change in the ODT process? | ||||

| Medical care | - | 3 (13.0) | 8 (34.8) | 12 (52.2) |

| Training and education | - | 2 (8.7) | 9 (39.1) | 12 (52.2) |

| Communication with family | - | 4 (17.4) | 11 (47.8) | 8 (34.8) |

| Research and development | 3 (13.0) | 5 (21.7) | 11 (47.8) | 4 (17.4) |

| Legislative changes | 7 (30.4) | 4 (17.4) | 7 (30.4) | 5 (21.7) |

| Financial changes | 6 (26.1) | 8 (34.8) | 5 (21.7) | 4 (17.4) |

| Management | 3 (13.0) | 6 (26.1) | 5 (21.7) | 9 (39.1) |

| Q38: How the following reasons have discouraged you from working in the area of ODT? | ||||

| The legislation in my country makes organ donation too difficult | 6 (26.1) | 5 (21.7) | 4 (17.4) | 8 (34.8) |

| Development of other areas of interest | 3 (13.0) | 7 (30.4) | 8 (34.8) | 5 (21.7) |

| Public attitudes toward donation are too difficult to overcome | 2 (8.7) | 7 (30.4) | 5 (21.7) | 9 (39.1) |

| Lack of hospital support for organ donation | 4 (17.4) | 8 (34.8) | 4 (17.4) | 7 (30.4) |

| Lack of resources for organ donation | 3 (13.0) | 9 (39.1) | 3 (13.0) | 8 (34.8) |

| Religious barriers make donation impossible | 5 (21.7) | 4 (17.4) | 9 (39.1) | 5 (21.7) |

| Others | 19 (82.6) | 2 (8.7) | - | 2 (8.7) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ballesté, C.; Choy, S.-H.; Galvao, M.; Alvarez, B.; Blanco, C.; Albiol, J.; Peralta, P.; Paredes, D.; Manyalich, M.; Valero, R., on behalf of The EMPODaT Consortium. Impact of the European–Mediterranean Postgraduate Program on Organ Donation and Transplantation (EMPODaT): A Survey Analysis at 6 Years. Transplantology 2025, 6, 26. https://doi.org/10.3390/transplantology6030026

Ballesté C, Choy S-H, Galvao M, Alvarez B, Blanco C, Albiol J, Peralta P, Paredes D, Manyalich M, Valero R on behalf of The EMPODaT Consortium. Impact of the European–Mediterranean Postgraduate Program on Organ Donation and Transplantation (EMPODaT): A Survey Analysis at 6 Years. Transplantology. 2025; 6(3):26. https://doi.org/10.3390/transplantology6030026

Chicago/Turabian StyleBallesté, Chloe, Seow-Huey Choy, Mauricio Galvao, Brian Alvarez, Carmen Blanco, Joaquim Albiol, Patricia Peralta, David Paredes, Martí Manyalich, and Ricard Valero on behalf of The EMPODaT Consortium. 2025. "Impact of the European–Mediterranean Postgraduate Program on Organ Donation and Transplantation (EMPODaT): A Survey Analysis at 6 Years" Transplantology 6, no. 3: 26. https://doi.org/10.3390/transplantology6030026

APA StyleBallesté, C., Choy, S.-H., Galvao, M., Alvarez, B., Blanco, C., Albiol, J., Peralta, P., Paredes, D., Manyalich, M., & Valero, R., on behalf of The EMPODaT Consortium. (2025). Impact of the European–Mediterranean Postgraduate Program on Organ Donation and Transplantation (EMPODaT): A Survey Analysis at 6 Years. Transplantology, 6(3), 26. https://doi.org/10.3390/transplantology6030026