Caregiver Perceptions of an Educational Animation for Mobilizing Social Support in Kidney Transplant Access: A Qualitative Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design

2.2. Setting

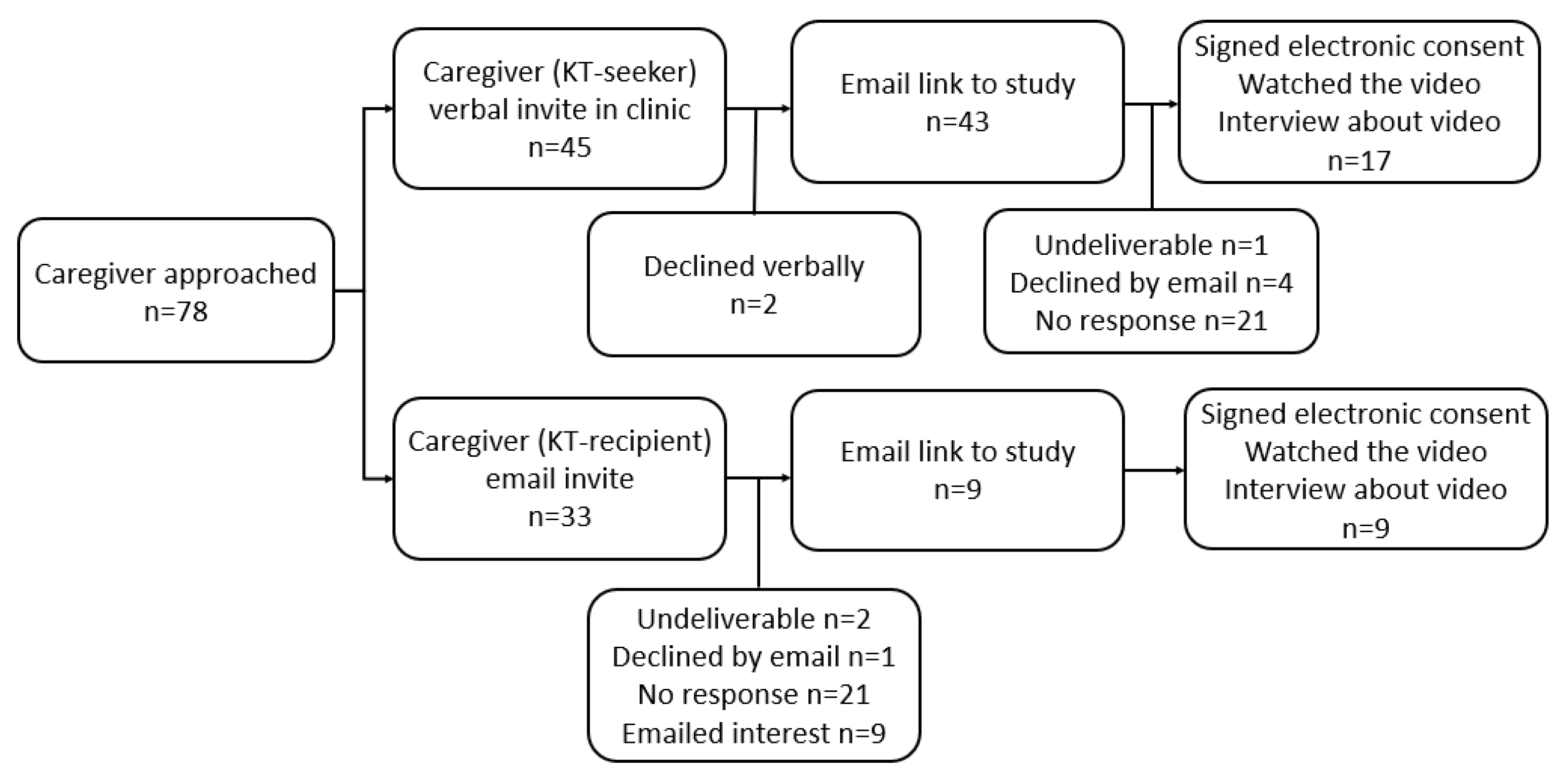

2.3. Participants

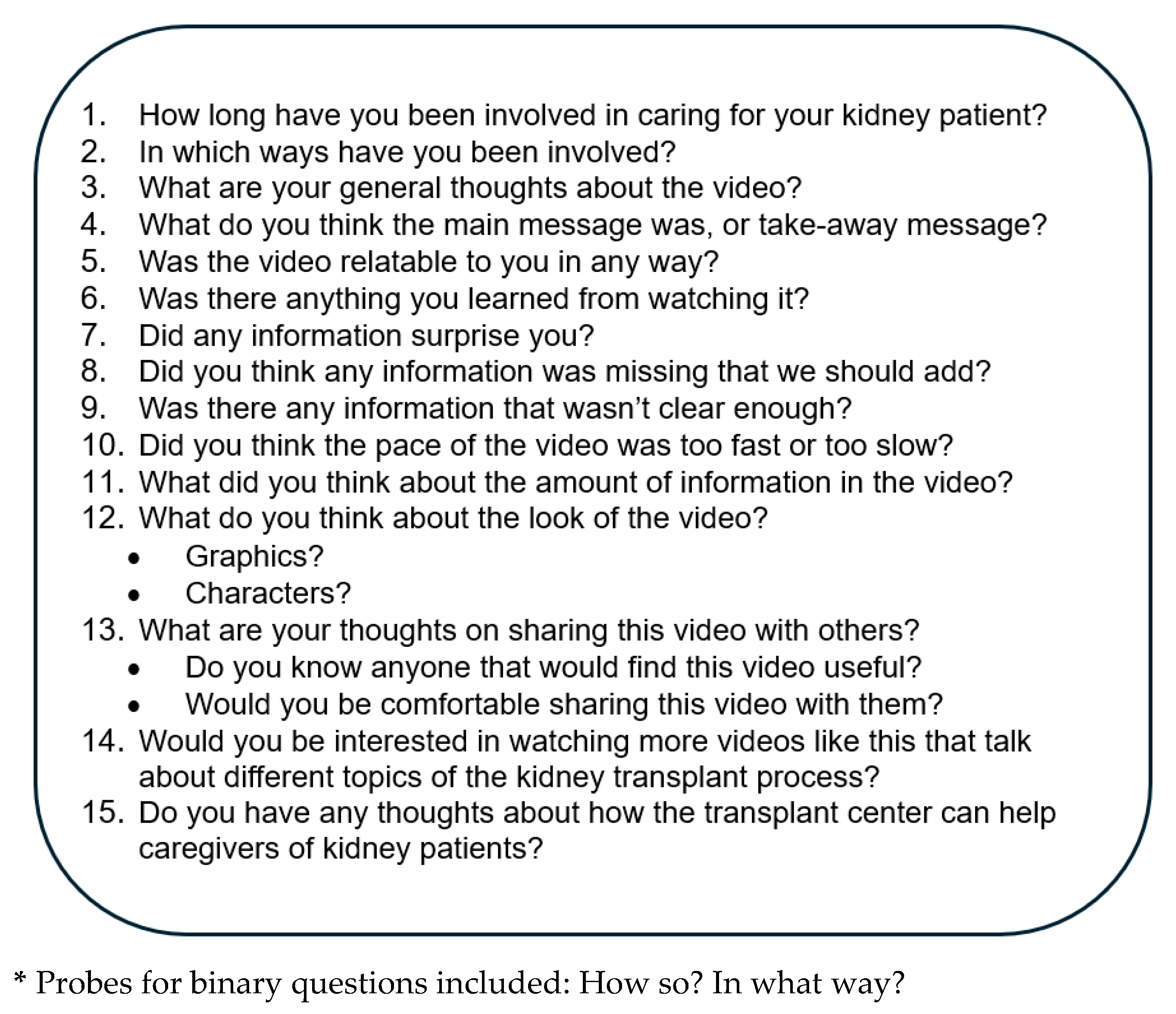

2.4. Data Collection

2.5. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Participant Characteristics

3.2. Qualitative Results

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| KT | Kidney transplant |

| CAB | Community Advisory Board |

References

- Crenesse-Cozien, N.; Dolph, B.; Said, M.; Feeley, T.H.; Kayler, L.K. Kidney Transplant Evaluation: Inferences from Qualitative Interviews with African American Patients and their Providers. J. Racial Ethn. Health Disparities 2019, 6, 917–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lewis, L.; Dolph, B.; Said, M.; Feeley, T.H.; Kayler, L.K. Enabling Conversations: African American Patients’ Changing Perceptions of Kidney Transplantation. J. Racial Ethn. Health Disparities 2019, 6, 536–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clark, C.R.; Hicks, L.S.; Keogh, J.H.; Epstein, A.M.; Ayanian, J.Z. Promoting access to renal transplantation: The role of social support networks in completing pre-transplant evaluations. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2008, 23, 1187–1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- King, E.A.; Ruck, J.M.; Garonzik-Wang, J.; Bowring, M.G.; Kumar, K.; Purnell, T.; Cameron, A.; Segev, D.L. Addressing Racial Disparities in Live Donor Kidney Transplantation Through Education and Advocacy Training. Transpl. Direct 2020, 6, e593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Locke, J.E.; Reed, R.D.; Kumar, V.; Berry, B.; Hendricks, D.; Carter, A.; Shelton, B.A.; Mustian, M.N.; MacLennan, P.A.; Qu, H.; et al. Enhanced Advocacy and Health Systems Training Through Patient Navigation Increases Access to Living-donor Kidney Transplantation. Transplantation 2020, 104, 122–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LaPointe Rudow, D.; Geatrakas, S.; Armenti, J.; Tomback, A.; Khaim, R.; Porcello, L.; Pan, S.; Arvelakis, A.; Shapiro, R. Increasing living donation by implementing the Kidney Coach Program. Clin. Transpl. 2019, 33, e13471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jesse, M.T.; Rubinstein, E.; Eshelman, A.; Wee, C.; Tankasala, M.; Li, J.; Abouljoud, M. Lifestyle and Self-Management by Those Who Live It: Patients Engaging Patients in a Chronic Disease Model. Perm. J. 2016, 20, 15–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stonnington, C.M.; Darby, B.; Santucci, A.; Mulligan, P.; Pathuis, P.; Cuc, A.; Hentz, J.G.; Zhang, N.; Mulligan, D.; Sood, A. A resilience intervention involving mindfulness training for transplant patients and their caregivers. Clin. Transpl. 2016, 30, 1466–1472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, R.D.; Killian, A.C.; Mustian, M.N.; Hendricks, D.H.; Baldwin, K.N.; Kumar, V.; Dionne-Odom, J.N.; Saag, K.; Hites, L.; Ivankova, N.V.; et al. The Living Donor Navigator Program Provides Support Tools for Caregivers. Prog. Transpl. 2021, 31, 55–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giordano, T.; Weinstock Esq., J.L.; Nathan, H.M. Assessing the Impact of an Online Support Group on the Emotional Health of Transplant Caregivers. Transplantation 2018, 102, S309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jesse, M.T.; Hansen, B.; Bruschwein, H.; Chen, G.; Nonterah, C.; Peipert, J.D.; Dew, M.A.; Thomas, C.; Ortega, A.D.; Balliet, W.; et al. Findings and recommendations from the organ transplant caregiver initiative: Moving clinical care and research forward. Am. J. Transpl. 2021, 21, 950–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pradel, F.G.; Suwannaprom, P.; Mullins, C.D.; Sadler, J.; Bartlett, S.T. Short-term impact of an educational program promoting live donor kidney transplantation in dialysis centers. Prog. Transpl. 2008, 18, 263–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boulware, L.E.; Hill-Briggs, F.; Kraus, E.S.; Melancon, J.K.; Falcone, B.; Ephraim, P.L.; Jaar, B.G.; Gimenez, L.; Choi, M.; Senga, M.; et al. Effectiveness of educational and social worker interventions to activate patients’ discussion and pursuit of preemptive living donor kidney transplantation: A randomized controlled trial. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2013, 61, 476–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Solbu, A.; Cadzow, R.B.; Pullano, T.; Brinser-Day, S.; Tumiel-Berhalter, L.; Kayler, L.K. Interviews With Lay Caregivers About Their Experiences Supporting Patients Throughout Kidney Transplantation. Prog. Transpl. 2024, 34, 21–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feeley, T.; Keller, M.; Kayler, L. Using Animated Videos to Increase Patient Knowledge: A Meta-Analytic Review. Health Educ. Behav. 2023, 50, 240–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kayler, L.K.; Nie, J.; Solbu, A.; Keller, M.; Handmacher, M. Use of Educational Animated Videos by Kidney Transplant Seekers and Social Network Members in a Randomized Trial (KidneyTIME). Kidney Dial. 2025, 5, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Booth, A.; Hannes, K.; Harden, A.; Noyes, J.; Harris, J.; Tong, A. COREQ (Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Studies). In Guidelines for Reporting Health Research: A User’s Manual; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2014; pp. 214–226. [Google Scholar]

- Lincoln, Y.S.; Guba, E.G. Naturalistic Inquiry; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- United States Census Bureau. Available online: https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/buffalocitynewyork (accessed on 19 August 2021).

- Bandura, A. Social Foundations of Thought and Action: A Social Cognitive Theory; Prentice Hall: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Reigeluth, C.M. In Search of a Better Way to Organize Instruction: The Elaboration Theory. J. Instr. Dev. 1979, 2, 8–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, R.E. Multimedia Learning; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Kayler, L.K.; Dolph, B.; Seibert, R.; Keller, M.; Cadzow, R.; Feeley, T.H. Development of the living donation and kidney transplantation information made easy (KidneyTIME) educational animations. Clin. Transpl. 2020, 34, e13830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feeley, T.H.; Kayler, L.K. Using Animation to Address Disparities in Kidney Transplantation. Health Commun. 2024, 1, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leiner, M.; Handal, G.; Williams, D. Patient communication: A multidisciplinary approach using animated cartoons. Health Educ. Res. 2004, 19, 591–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slater, M.; Rouner, D. Entertainment education and elaboration likelihood: Understanding the processing of narrative persuasion. Commun. Theory 2002, 12, 173–191. [Google Scholar]

- Dzara, K.; Chen, D.T.; Haidet, P.; Murray, H.; Tackett, S.; Chisolm, M.S. The effective use of videos in medical education. Acad. Med. 2020, 95, 970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- King, K.W.; Freimuth, V.; Lee, M.; Johnson-Turbes, C.A. The effectiveness of bundled health messages on recall. Am. J. Health Promot. 2013, 27 (Suppl. S3), S28–S35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hart, A.; Bruin, M.; Chu, S.; Matas, A.; Partin, M.R.; Israni, A.K. Decision support needs of kidney transplant candidates regarding the deceased donor waiting list: A qualitative study and conceptual framework. Clin. Transpl. 2019, 33, e13530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.H.; Lai, Y.H.; Tsai, M.K.; Shun, S.C. Care Needs for Organ Transplant Recipients Scale: Development and psychometric testing. J. Ren. Care 2021, 47, 123–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DePasquale, N.; Cabacungan, A.; Ephraim, P.L.; Lewis-Boyér, L.; Powe, N.R.; Boulware, L.E. Family Members’ Experiences With Dialysis and Kidney Transplantation. Kidney Med. 2019, 1, 171–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burges Watson, D.; Adams, J.; Azevedo, L.B.; Haighton, C. Promoting physical activity with a school-based dance mat exergaming intervention: Qualitative findings from a natural experiment. BMC Public Health 2016, 16, 609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amonoo, H.L.; Deary, E.C.; Harnedy, L.E.; Daskalakis, E.P.; Goldschen, L.; Desir, M.C. It takes a village: The importance of social support after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation, a qualitative study. Transplant. Cell. Ther. 2022, 28, e700–e701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, E.J.; Feinglass, J.; Carney, P.; Vera, K.; Olivero, M.; Black, A.; O’Connor, K.G.; Baumgart, J.M.; Caicedo, J.C. A Website Intervention to Increase Knowledge About Living Kidney Donation and Transplantation Among Hispanic/Latino Dialysis Patients. Prog. Transpl. 2016, 26, 82–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dageforde, L.A.; Petersen, A.W.; Feurer, I.D.; Cavanaugh, K.L.; Harms, K.A.; Ehrenfeld, J.M.; Moore, D.E. Health literacy of living kidney donors and kidney transplant recipients. Transplantation 2014, 98, 88–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kranenburg, L.W.; Zuidema, W.C.; Weimar, W.; Hilhorst, M.T.; Ijzermans, J.N.; Passchier, J.; Busschbach, J.J. Psychological barriers for living kidney donation: How to inform the potential donors? Transplantation 2007, 84, 965–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ladin, K.; Hanto, D.W. Understanding disparities in transplantation: Do social networks provide the missing clue? Am. J. Transpl. 2010, 10, 472–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schulz, A.J.; Williams, D.R.; Israel, B.A.; Lempert, L.B. Racial and spatial relations as fundamental determinants of health in Detroit. Milbank Q. 2002, 80, 677–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Total (n = 26) | Caregivers of KT-Seekers (n = 17) | Caregivers of KT-Recipients (n = 9) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | % (n) | % (n) | % (n) |

| Sex: Female | 73% (19) | 76% (13) | 67% (6) |

| Age (years): | |||

| 18–49 | 38% (10) | 35% (6) | 44% (4) |

| 50–60 | 27% (7) | 24% (4) | 33% (3) |

| More than 60 | 35% (9) | 41% (7) | 22% (2) |

| Race/ethnicity: | |||

| Black or African American | 23% (6) | 35% (6) | 0% (0) |

| Non-Hispanic White | 68% (18) | 53% (9) | 100% (9) |

| Hispanic or Latino | 4% (1) | 6% (1) | 0% (0) |

| Other | 4% (1) | 6% (1) | 0% (0) |

| Employment: Working | 88% (23) | 82% (14) | 100% (9) |

| Income: | |||

| Less than $30,000 | 12% (4) | 24% (4) | 0% (0) |

| $30,000 to $50,000 | 19% (4) | 24% (4) | 0% (0) |

| More than $50,000 | 46% (12) | 29% (5) | 78% (7) |

| Prefer not to answer | 23% (6) | 24% (4) | 22% (2) |

| College degree: | 62% (16) | 53% (9) | 78% (7) |

| Relationship to the patient: | |||

| Spouse | 50% (13) | 47% (8) | 56% (5) |

| Sibling | 27% (7) | 29% (5) | 22% (2) |

| Parent | 23% (6) | 24% (4) | 22% (2) |

| Time known the patient: | |||

| 1–5 years | 4% (1) | 0% (0) | 11% (1) |

| 6–9 years | 0% (0) | 0% (0) | 0% (0) |

| More than 10 years | 96% (25) | 100% (17) | 89% (8) |

| Access to a smartphone: | 96% (25) | 100% (17) | 89% (8) |

| Access to a computer: | 81% (21) | 76% (13) | 89% (8) |

| Uses email: | 96% (25) | 94% (16) | 100% (9) |

| Watches videos online: | 88% (23) | 92% (14) | 100% (9) |

| Device used in this study: | |||

| Computer | 19% (5) | 18% (3) | 22% (2) |

| Cellphone | 54% (14) | 60% (12) | 22% (2) |

| Tablet | 27% (7) | 12% (2) | 56% (5) |

| Social media frequency: | |||

| Less than once a week | 27% (7) | 35% (6) | 11% (1) |

| Once a week or more | 73% (19) | 65% (11) | 89% (8) |

| Number of close friends or others: | |||

| ≤3 | 54% (14) | 59% (10) | 44% (4) |

| 4 or more | 46% (12) | 41% (7) | 56% (5) |

| Survey Item | % (n) |

|---|---|

| Caregiver role readiness | |

| What are your thoughts about helping someone get through the kidney transplant process? | |

| I am not sure how to help someone navigate the transplant process. | 0% (0) |

| I am beginning to understand how to help someone navigate the transplant process. | 53% (9) |

| I understand how to help someone navigate the transplant process. | 24% (4) |

| I have helped someone navigate the transplant process before. | 24% (4) |

| What are your thoughts about helping someone find a living kidney donor? | |

| I am not sure how to help someone find a living kidney donor. | 18% (3) |

| I am beginning to understand how to help someone find a living kidney donor. | 47% (8) |

| I understand how to help someone find a living kidney donor. | 29% (5) |

| I have helped someone find a living kidney donor. | 0% (0) |

| The kidney patient does not want a living kidney donor. | 6% (1) |

| What are your thoughts about donating a kidney yourself? | |

| I am not thinking about being a living donor. | 76% (13) |

| I am beginning to think about being a living donor. | 0% (0) |

| I am seriously considering being a living donor. | 0% (0) |

| I am being evaluated as a possible living donor. | 24% (4) |

| I have been approved to be a donor. | 0% (0) |

| Living kidney donor communication self-efficacy | |

| I have all the information I need to start a conversation about living kidney donation. | |

| Strongly disagree | 6% (1) |

| Disagree | 12% (2) |

| Agree | 18% (3) |

| Strongly agree | 65% (11) |

| I am comfortable discussing the option of living kidney donation with people in my life. | |

| Strongly disagree | 6% (1) |

| Disagree | 0% (0) |

| Agree | 82% (14) |

| Strongly agree | 12% (2) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Keller, M.; Inoue, M.; Koizumi, N.; Meyo, S.; Solbu, A.; Handmacher, M.; Kayler, L. Caregiver Perceptions of an Educational Animation for Mobilizing Social Support in Kidney Transplant Access: A Qualitative Study. Transplantology 2025, 6, 17. https://doi.org/10.3390/transplantology6020017

Keller M, Inoue M, Koizumi N, Meyo S, Solbu A, Handmacher M, Kayler L. Caregiver Perceptions of an Educational Animation for Mobilizing Social Support in Kidney Transplant Access: A Qualitative Study. Transplantology. 2025; 6(2):17. https://doi.org/10.3390/transplantology6020017

Chicago/Turabian StyleKeller, Maria, Megumi Inoue, Naoru Koizumi, Samantha Meyo, Anne Solbu, Matthew Handmacher, and Liise Kayler. 2025. "Caregiver Perceptions of an Educational Animation for Mobilizing Social Support in Kidney Transplant Access: A Qualitative Study" Transplantology 6, no. 2: 17. https://doi.org/10.3390/transplantology6020017

APA StyleKeller, M., Inoue, M., Koizumi, N., Meyo, S., Solbu, A., Handmacher, M., & Kayler, L. (2025). Caregiver Perceptions of an Educational Animation for Mobilizing Social Support in Kidney Transplant Access: A Qualitative Study. Transplantology, 6(2), 17. https://doi.org/10.3390/transplantology6020017