Mitral Annular Disjunction: Where Is the Cut-Off Value? Case Series and Literature Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

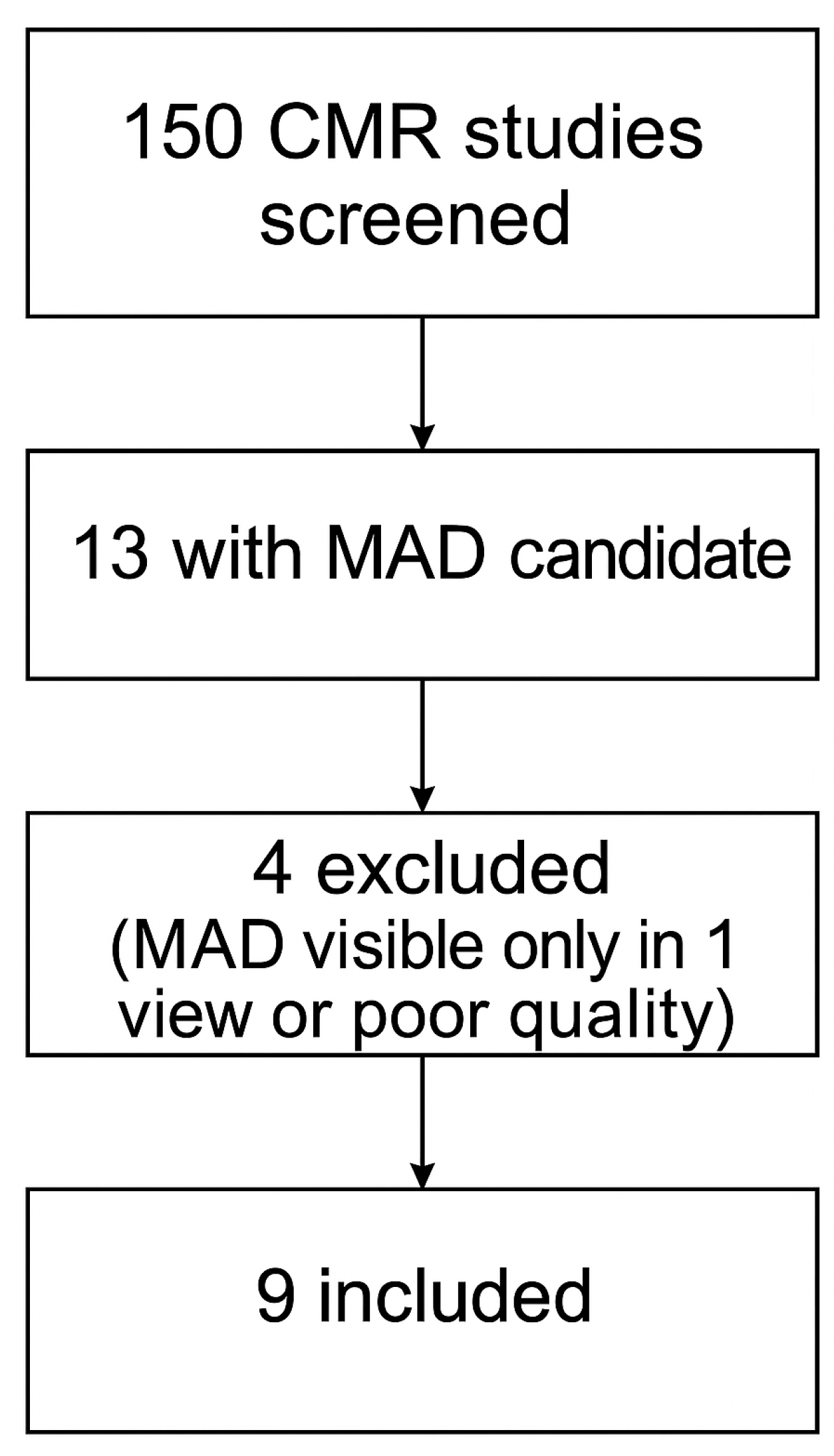

2. Materials and Methods

- Presence of MAD visible in at least two cine SSFP projections, regardless of severity;

- Adequate image quality for reliable MAD measurement and LGE assessment.

- The exclusion criteria were:

- MAD visible in only one projection;

- Significant artifacts or suboptimal image quality precluding accurate measurements.

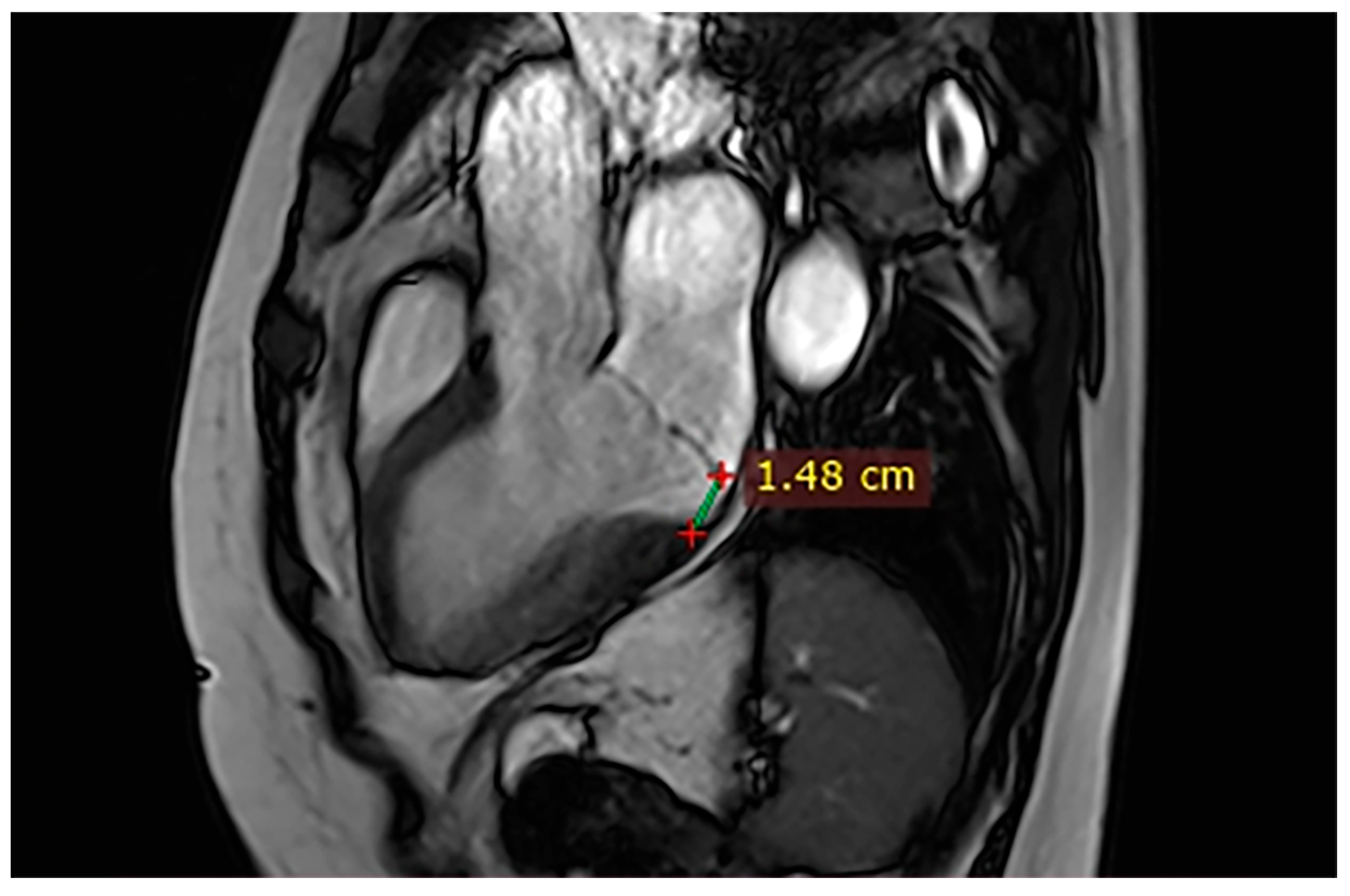

CMR Acquisition and MAD Analysis Protocol

3. Results

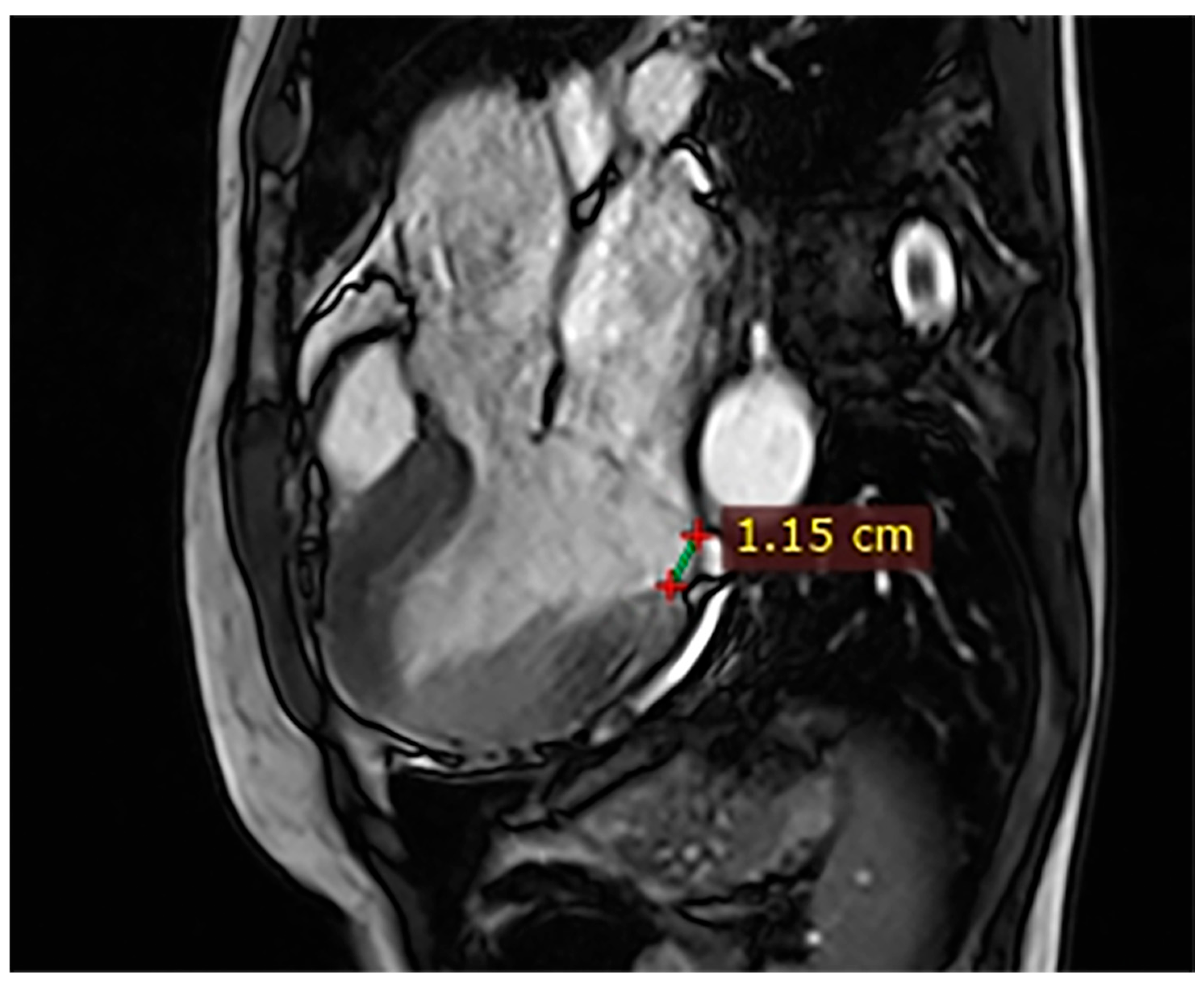

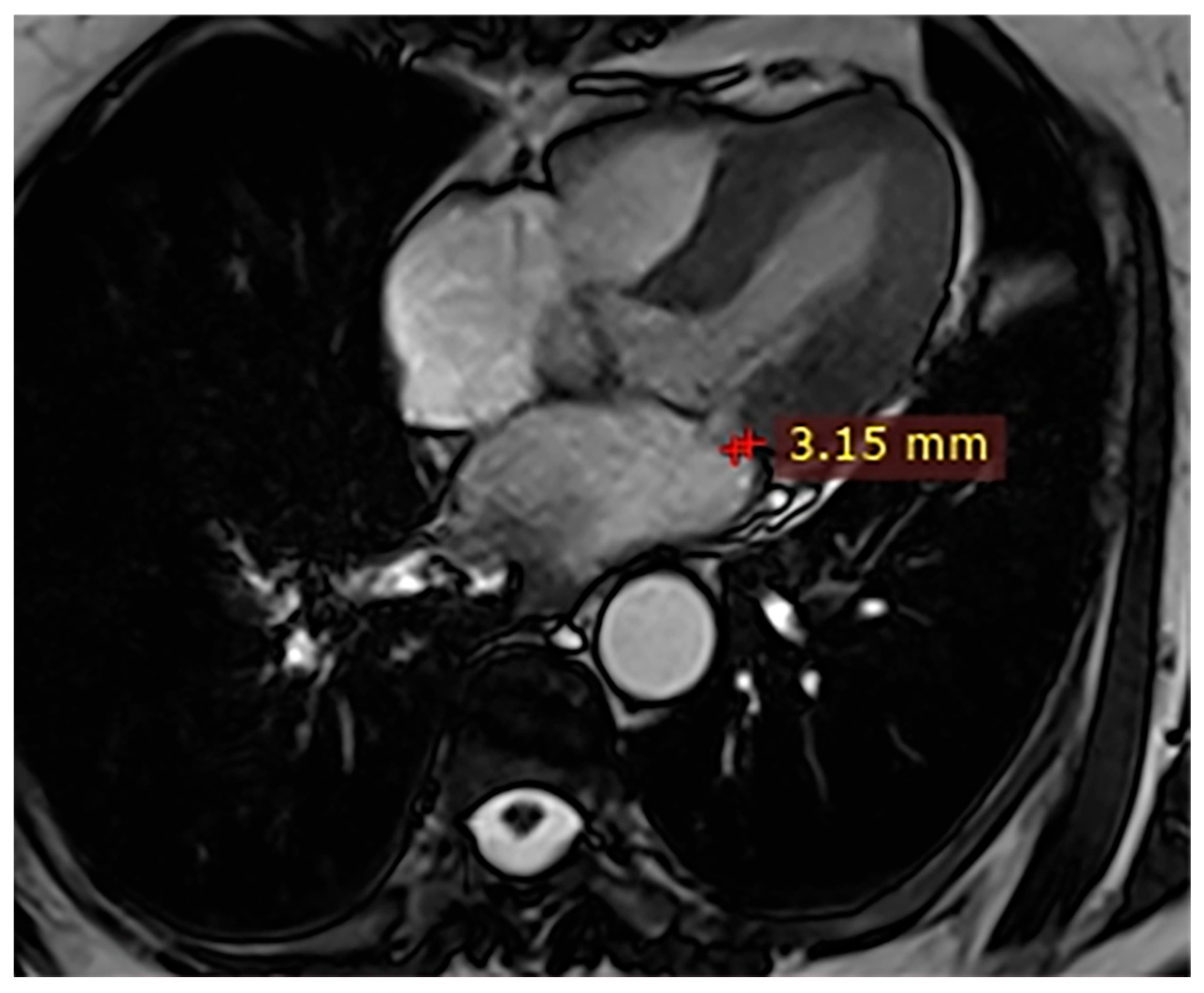

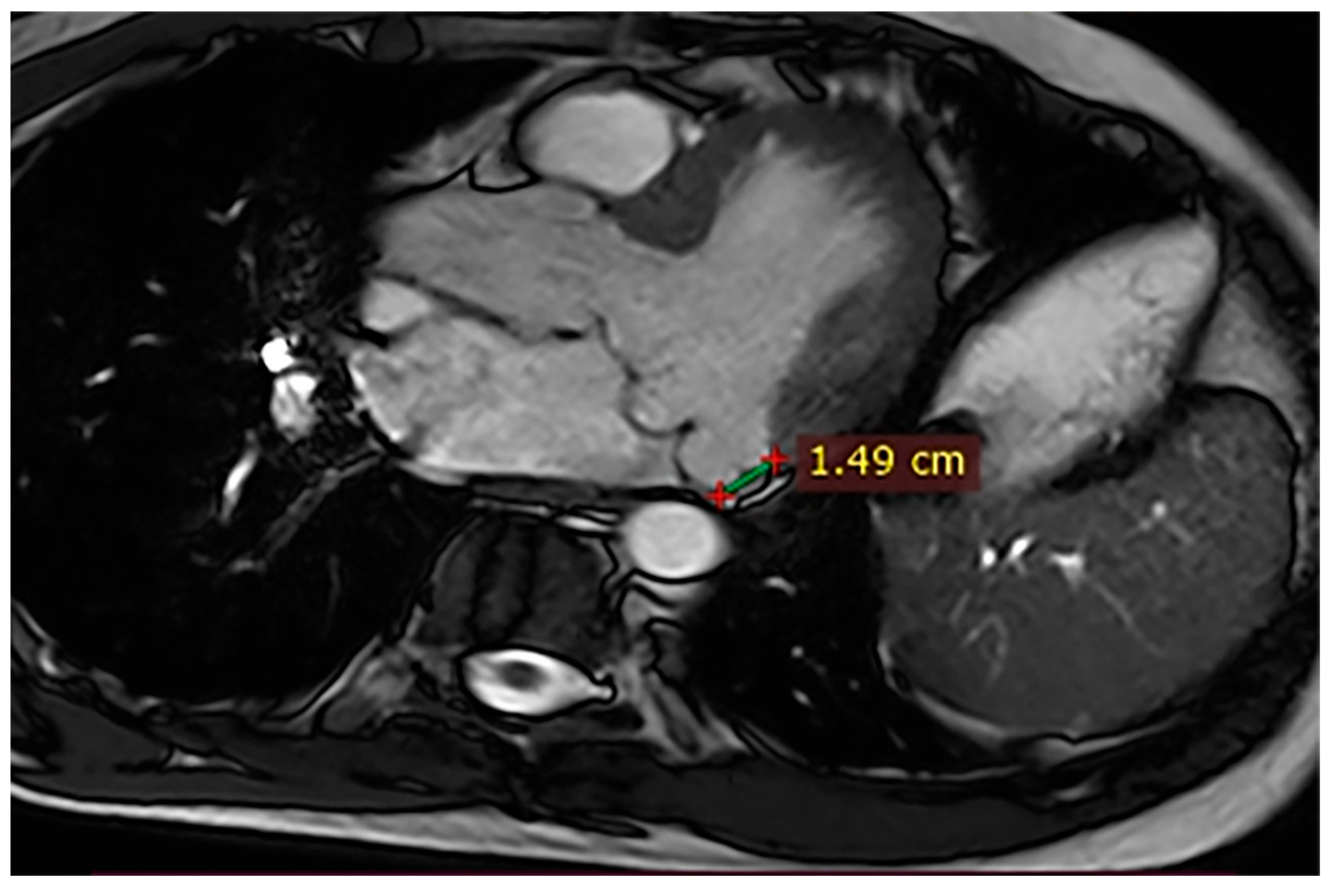

3.1. Cases

Brief Case Summary

4. Discussion

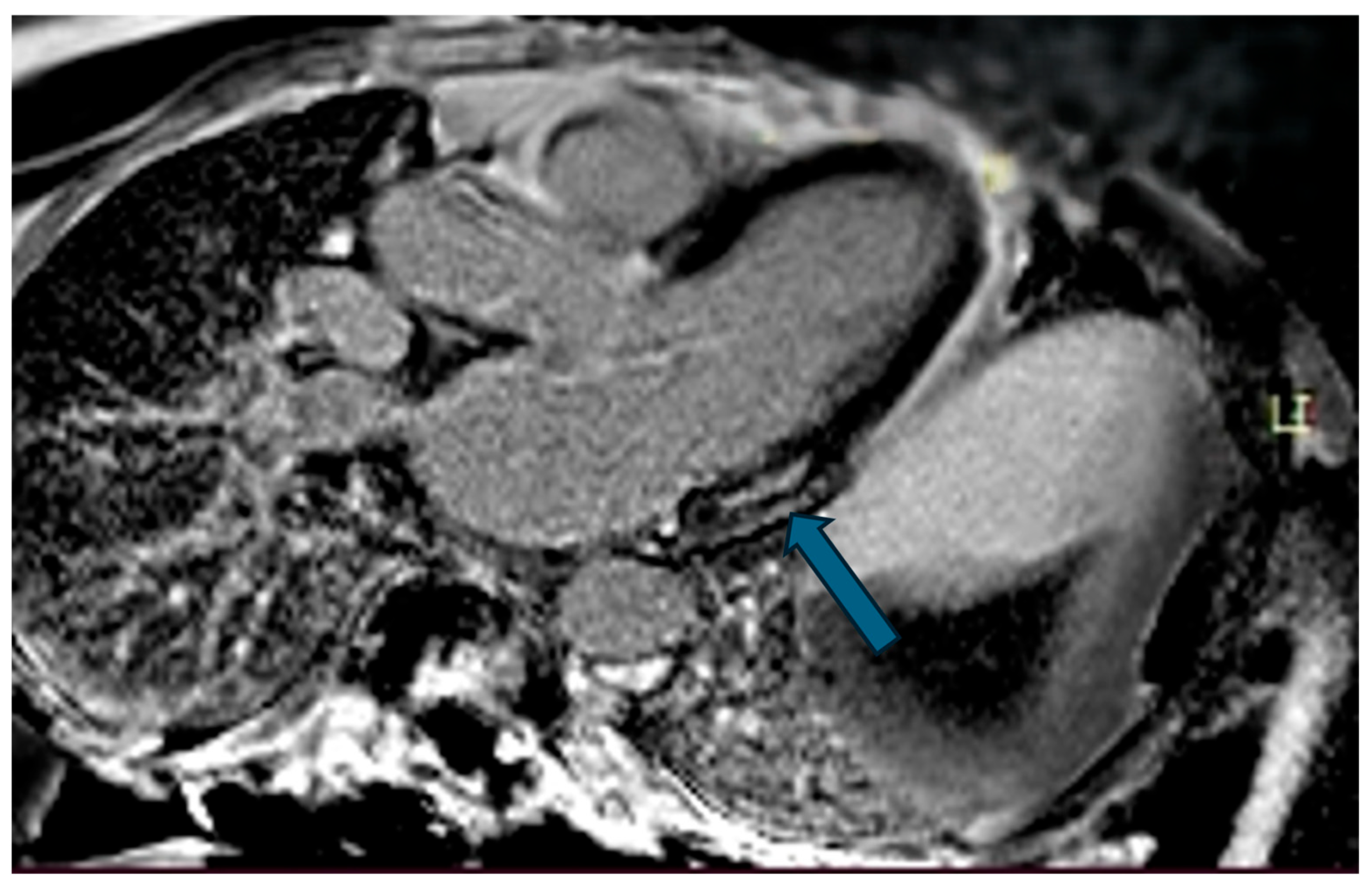

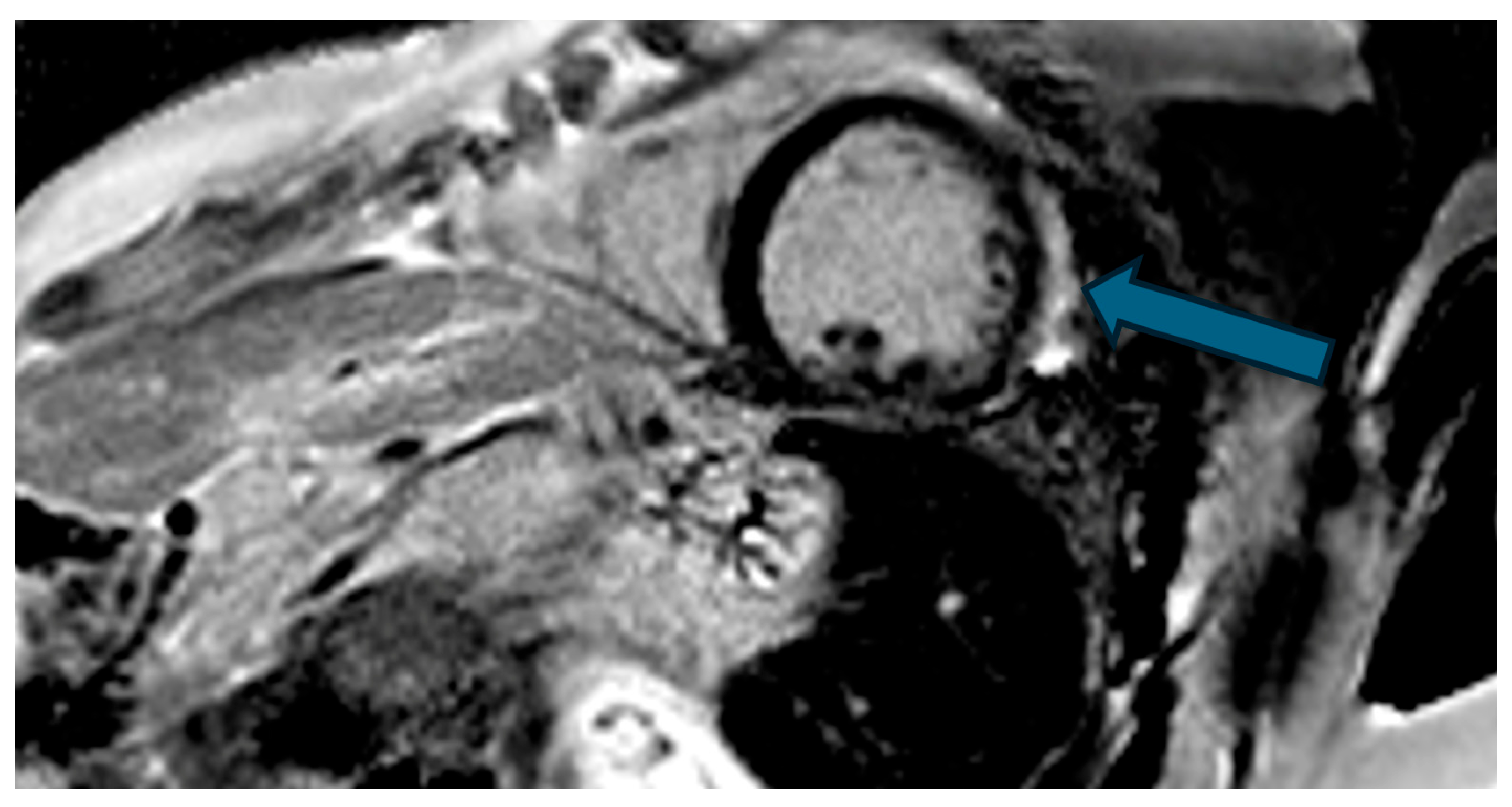

4.1. MAD Imaging

4.1.1. Imaging Techniques

4.1.2. Interplay Between Echocardiography and CMR

4.1.3. Diagnostic Aspects of CMR

4.2. Clinical Considerations

4.2.1. Associated Risks and Correlation with Ventricular Arrhythmias

4.2.2. Surgery and ICD Considerations

4.2.3. Correlation with Mitral Valve Disease

4.2.4. Management

4.2.5. Follow-Up

4.2.6. Clinical Management and Follow-Up When MAD Is First Detected on Echocardiography

4.2.7. Prognosis

4.2.8. Study Observations

4.2.9. Physiological Versus Pathological MAD

4.2.10. Pseudo-MAD, True MAD, and the Arrhythmic MVP Phenotype

4.3. Study Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MAD | Mitral Annular Disjunction |

| CMR | Cardiac Magnetic Resonance |

| CCT | Cardiac Computed Tomography |

| MVP | Mitral Valve Prolapse |

| US | UltraSound |

| OHCA | Out-of-Hospital Cardiac Arrest |

| MRI | Magnetic Resonance Imaging |

| LVEF | Left Ventricular Ejection Fraction |

| LGE | Late Gadolinium Enhancement |

| SSFP | Steady-State Free Precession |

| VT | Ventricular Tachycardia |

| VF | Ventricular Fibrillation |

| ICD | Implantable Cardiac Device |

| PSIR | Phase Sensitive Inversion Recovery |

References

- Gupta, S.; Shihabi, A.; Patil, M.K.; Shih, T. Mitral annular disjunction: A scoping review. Cardiol. Rev. 2023, 33, 145–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Troger, F.; Klug, G.; Poskaite, P.; Tiller, C.; Lechner, I.; Reindl, M.; Holzknecht, M.; Fink, P.; Brunnauer, E.-M.; Gizewski, E.R.; et al. Mitral annular disjunction in out-of-hospital cardiac arrest patients: A retrospective cardiac MRI study. Clin. Res. Cardiol. 2024, 113, 770–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musella, F.; Azzu, A.; Antonopoulos, A.S.; La Mura, L.; Mohiaddin, R.H. Comprehensive mitral valve prolapse assessment by cardiovascular MRI. Clin. Radiol. 2022, 77, e120–e129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanani, M.; Alpendurada, F.; Rana, B.S. The anatomy of the mitral valve: A retrospective analysis of yesterday’s future. J. Heart Valve Dis. 2003, 12, 543–547. [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira, D.; Srinivasan, J.; Espino, D.; Buchan, K.; Dawson, D.; Shepherd, D. Geometric description for the anatomy of the mitral valve: A review. J. Anat. 2020, 237, 209–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- McCarthy, K.P.; Ring, L.; Rana, B.S. Anatomy of the mitral valve: Understanding the mitral valve complex in mitral regurgitation. Eur. J. Echocardiogr. 2010, 11, i3–i9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stankowski, K.; Catapano, F.; Donia, D.; Bragato, R.M.; Lopes, P.; Abecasis, J.; Ferreira, A.; Slipczuk, L.; Masci, P.G.; Condorelli, G.; et al. True-and pseudo-mitral annular disjunction in patients undergoing cardiovascular magnetic resonance. J. Cardiovasc. Magn. Reson. 2025, 27, 101413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Essayagh, B.; Sabbag, A.; Antoine, C.; Benfari, G.; Batista, R.; Yang, L.T.; Maalouf, J.; Thapa, P.; Asirvatham, S.; Michelena, H.I.; et al. The mitral annular disjunction of mitral valve prolapse: Presentation and outcome. JACC Cardiovasc. Imaging 2021, 14, 2073–2087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thamman, R.; Gupta, N.; Doshi, R.; Ellahham, S.; Elkhazendar, M.; Gupta, R. Mitral annular disjunction: Wolf in sheep’s clothing? Echocardiography 2020, 37, 1710–1712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, L.; Yuan, J.; Feng, Y.; Deng, C.; Ma, H.; Chen, Y.; Peng, Y. Age-related changes in mitral annular disjunction: A retrospective analysis using enhanced cardiac CT. Int. J. Cardiol. 2024, 414, 132424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gulati, A.; Gulsin, G.; Hu, H.; Rajiah, P.; Sundaram, V. Mitral annular disjunction: Review of an increasingly recognized mitral valve entity. Radiology 2023, 5, e230131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figliozzi, S.; Stankowski, K.; Tondi, L.; Catapano, F.; Gitto, M.; Lisi, C.; Bombace, S.; Olivieri, M.; Cannata, F.; Fazzari, F.; et al. Mitral annulus disjunction in consecutive patients undergoing cardiovascular magnetic resonance: Where is the boundary between normality and disease? J. Cardiovasc. Magn. Reson. 2024, 26, 101056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Custódio, P.; De Campos, D.; Moura, A.R.; Shiwani, H.; Savvatis, K.; Joy, G.; Lambiase, P.D.; Moon, J.C.; Khanji, M.Y.; Augusto, J.B.; et al. Mitral annulus disjunction: A comprehensive cardiovascular magnetic resonance phenotype and clinical outcomes study. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging 2024, 61, 1368–1375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zugwitz, D.; Fung, K.; Aung, N.; Rauseo, E.; McCracken, C.; Cooper, J.; El Messaoudi, S.; Anderson, R.H.; Piechnik, S.K.; Neubauer, S.; et al. Mitral Annular Disjunction Assessed Using CMR Imaging: Insights From the UK Biobank Population Study. JACC Cardiovasc. Imaging 2022, 15, 1856–1866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Perazzolo Marra, M.; Basso, C.; De Lazzari, M.; Rizzo, S.; Cipriani, A.; Giorgi, B.; Lacognata, C.; Rigato, I.; Migliore, F.; Pilichou, K.; et al. Morphofunctional abnormalities of mitral annulus and arrhythmic risk in arrhythmic mitral valve prolapse. Circ. Cardiovasc. Imaging 2016, 9, e005030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chess, R.J.; Mazur, W.; Palmer, C. Stop the madness: Mitral annular disjunction. CASE 2023, 7, 116–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Punjabi, P.P.; Rana, B.S. Mitral annular disjunction: Is MAD ‘normal’? Eur. Heart J. Cardiovasc. Imaging 2021, 22, 623–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debonnaire, P.; Penicka, M.; Marsan, N.A.; Delgado, V. Contemporary imaging of normal mitral valve anatomy and function. Curr. Opin. Cardiol. 2012, 27, 455–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ho, S.Y. Anatomy of the mitral valve. Heart 2002, 88, iv5–iv10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silbiger, J.J.; Bazaz, R. Contemporary insights into the functional anatomy of the mitral valve. Am. Heart J. 2009, 158, 887–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Da Col, U.; Rinaldi, M.; Di Lazzaro, D. Posterior mitral leaflet: New insights in functional anatomy and nomenclature. J. Cardiovasc. Med. 2010, 11, 820–826. [Google Scholar]

- Tani, T.; Konda, T.; Kim, K.; Ota, M.; Furukawa, Y. Mitral annular disjunction: A new disease spectrum. Cardiol. Clin. 2021, 39, 289–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmo, P.; Andrade, M.J.; Aguiar, C.; Rodrigues, R.; Gouveia, R.; Silva, J.A. Mitral annular disjunction in myxomatous mitral valve disease: A relevant abnormality recognizable by transthoracic echocardiography. Cardiovasc. Ultrasound 2010, 8, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dejgaard, L.A.; Skjølsvik, E.T.; Lie, Ø.H.; Ribe, M.; Stokke, M.K.; Hegbom, F.; Scheirlynck, E.S.; Gjertsen, E.; Andresen, K.; Helle-Valle, T.M.; et al. The mitral annulus disjunction arrhythmic syndrome. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2018, 72, 1600–1609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Essayagh, B.; Iacuzio, L.; Civiaia, F.; Levy, F. Mitral annular disjunction in mitral valve prolapse: A cardiac magnetic resonance study. Arch. Cardiovasc. Dis. Suppl. 2019, 11, 62–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez Tijmes, F.; Chatur, S.; Murphy, D.T.; Karur, G.R. Mitral annular disjunction on cardiac MRI: Prevalence and association with disease severity in Loeys–Dietz syndrome. Int. J. Cardiol. 2023, 392, 131276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drescher, C.S.; Kelsey, M.D.; Yankey, G.S.; Sun, A.Y.; Wang, A.; Sadeghpour, A.; Glower, D.D., Jr.; Vemulapalli, S.; Kelsey, A.M. Imaging Considerations and Clinical Implications of Mitral Annular Disjunction. Circ. Cardiovasc. Imaging 2022, 15, e014243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kulkarni, A.A.; Chhabra, C.; Burkule, N.; Kamat, R. Mitral annulus disjunction: Role of cardiac magnetic resonance imaging in the workup. Indian J. Radiol. Imaging 2022, 32, 576–581. [Google Scholar]

- Bennett, S.; Thamman, R.; Griffiths, T.; Oxley, C.; Khan, J.N.; Phan, T.; Patwala, A.; Heatlie, G.; Kwok, C.S. Mitral annular disjunction: A systematic review of the literature. Echocardiography 2019, 36, 1549–1558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elikowski, W.; Małek-Elikowska, M.; Ganowicz-Kaatz, T.; Greberska, W.; Fertała, N.; Zawodna-Marszałek, M.; Baszko, A. Multimodality imaging of mitral annular disjunction. Pol. Merkur. Lek. 2020, 48, 335–338. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Silva Ferreira, M.V.; Santos, A.; Araujo-Filho, J.; Dantas, R.; Torres, A. Mitral annular disjunction at cardiac MRI: What to know and look for. RadioGraphics 2024, 44, e230156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faletra, F.F.; Leo, L.A.; Paiocchi, V.L.; Maisano, F. Morphology of mitral annular disjunction in mitral valve prolapse. J. Am. Soc. Echocardiogr. 2022, 35, 176–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaworski, K.; Firek, B.; Syska, P.; Lewandowski, M.; Śpiewak, M.; Dąbrowski, R. Malignant arrhythmia associated with mitral annular disjunction: Myocardial work as a potential tool in the search for a substrate. Kardiol. Pol. 2022, 80, 93–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sabbag, A.; Essayagh, B.; Barrera, J.D.R.; Basso, C.; Berni, A.; Cosyns, B.; Deharo, J.-C.; Deneke, T.; Di Biase, L.; Enriquez-Sarano, M.; et al. EHRA expert consensus statement on arrhythmic mitral valve prolapse and mitral annular disjunction complex in collaboration with the ESC Council on valvular heart disease and the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging endorsed by the Heart Rhythm Society, by the Asia Pacific Heart Rhythm Society, and by the Latin American Heart Rhythm Society. Europace 2022, 24, 1981–2003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Case | Patient (Sex, Age) | Symptoms | MAD (mm) | Valvular Issues | LGE | Other Details |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Female, 61 years old | Syncope | 11 | MVP, mitral regurgitation | Lateral | Holter: atrial tachycardia and ventricular ectopy; cardiology follow-up planned for possible mitral valve repair |

| 2 | Male, 52 years old | Syncope and atypical chest pain | 10 | - | Lateral | History of ventricular arrhythmias; cardiology follow-up and Holter monitoring recommended |

| 3 | Female, 74 years old | Extrasystole | 3 | - | No LGE | No LGE; patient reassured and scheduled for periodic clinical follow-up |

| 4 | Male, 34 years old | Extrasystole in Marfan syndrome | 15 | MVP, valvular regurgitation | No LGE | Marfan syndrome; MVP with regurgitation; regular cardiology follow-up advised. |

| 5 | Male, 63 years old | Heart failure | 2,5 | MVP, valvular regurgitation | No LGE | Reduced LVEF (47%) with left atrial dilatation; heart failure therapy optimized; follow-up planned. |

| 6 | Male, 68 years old | Palpitations | 5 | - | Lateral | LGE in basal lateral wall; electrophysiological evaluation and ECG monitoring recommended. |

| 7 | Female, 53 years old | Extrasystole and syncope | 15 | MVP, valvular regurgitation | Basal-lateral | Extensive MAD with MVP and LGE; increased arrhythmic risk; antiarrhythmic therapy considered. |

| 8 | Female, 63 years old | Aortic and mitral regurgitation | 11 | Aortic and mitral regurgitation | Lateral | Aorto-mitral regurgitation with septal hypokinesia; mitral valve repair performed; heart failure therapy started. |

| 9 | Male, 45 years old | Palpitations and vertigo | 10 | - | Lateral | Basal lateral LGE; regular clinical and ECG follow-up recommended |

| MAD Extent Threshold Explored | Representative References | Study Population/Imaging Method | Main Clinical Implications |

|---|---|---|---|

| ≥1 mm (any measurable MAD) | Gupta et al. [1]; Troger et al. [2]; Figliozzi et al. [7]; Custódio et al. [13]; Zugwitz et al. [14]; Gulati et al. [11] | Large echocardiographic and CMR cohorts, including general populations and patients with mitral valve prolapse. | Using any measurable MAD (≥1 mm) as the definition leads to a very high reported prevalence in both general CMR cohorts and MVP populations, with high sensitivity for detecting any disjunction but limited specificity; many individuals with small MAD and no clear arrhythmic substrate are included. |

| ≥4 mm (moderate MAD) | Figliozzi et al. [7]; Perazzolo Marra et al. [15] | Consecutive CMR cohorts and arrhythmic mitral valve prolapse populations with systematic MAD measurements. | When MAD ≥ 4 mm is examined separately, its prevalence is markedly lower (around 10–15% in consecutive CMR series), and it shows a stronger association with structural abnormalities, non-ischemic LGE in basal lateral segments, and a higher burden of ventricular ectopy or ventricular tachycardia, particularly in arrhythmic MVP cohorts. This threshold has therefore been used as a more specific marker of potentially pathological MAD compared with very small disjunctions. |

| ≥6 mm (extensive MAD) | Figliozzi et al. [7]; Dejgaard et al. [24]; Essayagh et al. [25] | High-risk arrhythmic mitral valve prolapse cohorts and selected CMR studies focusing on malignant ventricular arrhythmias and myocardial fibrosis. | Extensive MAD in the range of ≥6 mm is uncommon in unselected populations but is overrepresented in arrhythmic MVP cohorts and in patients with non-ischemic fibrosis of the basal inferolateral wall and/or papillary muscles. In CMR series, MAD ≥ 6 mm has shown a trend toward higher rates of adverse arrhythmic endpoints, and arrhythmic MVP studies consistently report longer MAD lengths in high-risk phenotypes, suggesting that this range may correspond to a truly pathological disjunction requiring closer clinical surveillance. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Balestrucci, G.; Buffa, V.; Del Canto, M.T.; Brunese, M.C.; Cappabianca, S.; Reginelli, A. Mitral Annular Disjunction: Where Is the Cut-Off Value? Case Series and Literature Review. Hearts 2026, 7, 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/hearts7010002

Balestrucci G, Buffa V, Del Canto MT, Brunese MC, Cappabianca S, Reginelli A. Mitral Annular Disjunction: Where Is the Cut-Off Value? Case Series and Literature Review. Hearts. 2026; 7(1):2. https://doi.org/10.3390/hearts7010002

Chicago/Turabian StyleBalestrucci, Giovanni, Vitaliano Buffa, Maria Teresa Del Canto, Maria Chiara Brunese, Salvatore Cappabianca, and Alfonso Reginelli. 2026. "Mitral Annular Disjunction: Where Is the Cut-Off Value? Case Series and Literature Review" Hearts 7, no. 1: 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/hearts7010002

APA StyleBalestrucci, G., Buffa, V., Del Canto, M. T., Brunese, M. C., Cappabianca, S., & Reginelli, A. (2026). Mitral Annular Disjunction: Where Is the Cut-Off Value? Case Series and Literature Review. Hearts, 7(1), 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/hearts7010002