1. Introduction

The ill-defined phase arising from the vanishing amplitude of an optical wave has led to the development of a new field in optics called singular optics [

1,

2]. A typical study on the singular property of optical fields is to find the zero intensity regions of collective light waves. These regions can be point(s), line(s), or plane(s).

Although seemingly simple when the singular region is a point, such a structure has numerous potential applications. For example, because the phase of a wave is well-defined except for a point, a wave can have a circulating structure around that point, thus forming a vortex-like shape [

1]. In other words, a circulating light beam carrying an angular momentum typically has a vortex at its center. This angular momentum can be classically quantified in terms of (discrete) topological charges.

A similar singular behavior has also been studied in partially coherent waves [

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9]. One interesting model for air turbulence is the beam-wander model, where the beam axis fluctuates slowly and randomly, generating a partially coherent wave field. The associated topological charges of the beam were found to be quite stable during propagation until it was absorbed by air molecules [

10]. This stability leads to the conservation of the charge (angular momentum), which can be exploited in optical communications [

9]. This beam-wander model was applied to the Laguerre–Gauss beam with

and

, providing insight into vorticity [

11]. The same beam with

and

was numerically discussed in [

10]. They found that the conservation of angular momentum led to the interesting result of transforming high-order optical singularities into low-order coherence singularities by preserving the total order of singularities [

10]. Subsequently, analytical solutions for all azimuthal orders of the partially coherent Laguerre–Gauss beam of radial order zero were obtained [

12].

Recently, several interesting studies have been published on beam vortices and their applications. These include a study of manipulating the symmetry of spin splitting upon reflection using a pair of vortices of beam [

13] and its related work [

14], as well as the study of partially coherent sources with coherent modes using spatiotemporal optical vortex beams [

15]. There are also studies on the propagation of partially coherent beams in atmospheric turbulence. These include studies on scintillation properties of the beam-wander model [

16], applications of the beam-wander model to angular momentum [

17,

18], the modified Huygens–Fresnel method [

19], the vortex evolution [

20], and the beam-wander of partially coherent Gaussian Shell-model beams [

21]. In addition, there is a numerical study on the propagation of partially coherent Laguerre–Gauss beams [

22,

23] as well as a study on the propagation of partially coherent twisted Laguerre–Gaussian pulsed beam [

24].

In this work, as an explicit extension of [

11], we reexamine the model by explicitly deriving the expression in the higher order of

,

and investigate the behavior of vortices during the propagation. In

Section 2, we present an explicit representation of the Laguerre–Gauss beam for

and

. In

Section 3, we investigate the role of vortices in propagation in the order. The details of the calculation can be found in

Appendix A and we present a contour plot to verify the consistency of our calculations with the previous results in

Appendix B. In

Section 4, we examine the relation between the complex degree of coherence

and the beam-wander model parameter

, the orbital angular momentum flux density in

Section 5, and conclude in

Section 6.

2. Correlation Singularities in the Beam-Wander Model

A monochromatic scalar wave field,

with the frequency

, can be represented as

where the phase factor of the spatial dependence of the amplitude can be separated out as

However, when the amplitude vanishes, the phase cannot be well defined and the wave field becomes singular.

This singular behavior can also affect the cross-spectral density of partially coherent waves. The cross-spectral density of the scalar fields can be written as

where

is assumed to be the monochromatic realization of a partially coherent field [

5,

10].

Let us examine the cross-spectral density in the model of ‘beam wander’ in atmospheric turbulence [

25,

26] as

where the integral represents the ensemble average over the source plane on a transverse position

.

is the probability density which governs the coherence of the wave, and thus enables us to create a partially coherent field.

is the Gaussian function in terms of the position of the central vortex core,

.

where

is a diffusion scale representing the average wander of the vortex core and is related to the spatial coherence [

26].

satisfies

for the fully coherent field and

for the completely incoherent field. We refer to

as the correlation parameter.

We choose the Laguerre–Gauss beam as a scalar field,

, as performed explicitly for the low-order (

and

) in the work [

11] and implicitly for all orders in the work [

12]. The general expression of the Laguerre–Gauss beam can be written as [

25]

where

is the associated-Laguerre polynomials of orders of

n and

m, and

is the longitudinal phase delay on the transverse plane called Gouy phase. Also,

and

are the beam width and the radius of curvature of the wavefront, respectively, given as

where

is called Rayleigh length and

is the beam waist at

. They are related by

So,

k can be expressed as

In this work, we use the Laguerre–Gauss beam with

and

as the scalar field to obtain the explicit expression of the cross-spectral density,

In this section, we consider the field at the zero point (

) of the beam,

where

,

, and

as

. We express this field in rectangular coordinates

Note that the exponential part is the same as the first-order case. Performing the integration is quite lengthy but straightforward. To perform the integration, it is more convenient to change the integration variables from

and

to

and

, respectively.

and

are defined as follows:

For later convenience, we separate the real and imaginary parts in the spectral density. We keep in mind that both the real part and the imaginary part of the cross-spectral density must vanish separately to have the vanishing cross-spectral density, i.e., to have a singular behavior. The real and the imaginary parts of the non-exponential factor (denoted by []) in Equation (

13) can be written, respectively, as

After the

-integration (in practice,

), the cross-spectral density becomes

Here, we use the following values of definite integrals:

As we can see in Equation (

17), the real part is symmetric under the exchange of the subindices ‘1’ and ‘2’ while the imaginary part is antisymmetric. Note that both

and

are symmetric under the exchange. This fact verifies the Hermitian property of the cross-spectral density,

.

The non-exponent imaginary part of the cross-spectral density in Equation (

17) can be written in a more simplified form of

The imaginary part of the cross-spectral density vanishes when the first factor in Equation (

19) is zero,

This condition is met when

This relation implies

and thus

or

. Therefore, a singularity in the cross-spectral density occurs when the real part also vanishes. (Note that the real part of the cross-spectral density in Equation (

17) does not vanish when the second factor in

of Equation (

19) vanishes, i.e.,

).

To search for the vanishing real part, we rewrite the relevant factors in the real part of the cross-spectral density in terms of polar coordinates,

where

and

for the vanishing amplitude. By using the above relations, the real part of the cross-spectral density in Equation (

17) becomes

To obtain the relations between

and

satisfying

, we define the following replacement,

Then, we obtain the quadratic equation for

,

The solution to the quadratic equation is

Now, we can find the relations for

and

from the solutions and find a similar behavior that was found in the first-order case in Ref. [

11]. From the following coordinate transformation (rotation), we have

This condition yields a pair of hyperbolas for

Similar relations hold for another pair of hyperbolas with two variables of

and

,

Thus, the resulting equations for this pair of hyperbolas are

To obtain the correlation singularities of

, we need both the real and imaginary parts of

to vanish. The vanishing real part gives two pairs of hyperbolas depending on the condition in Equation (

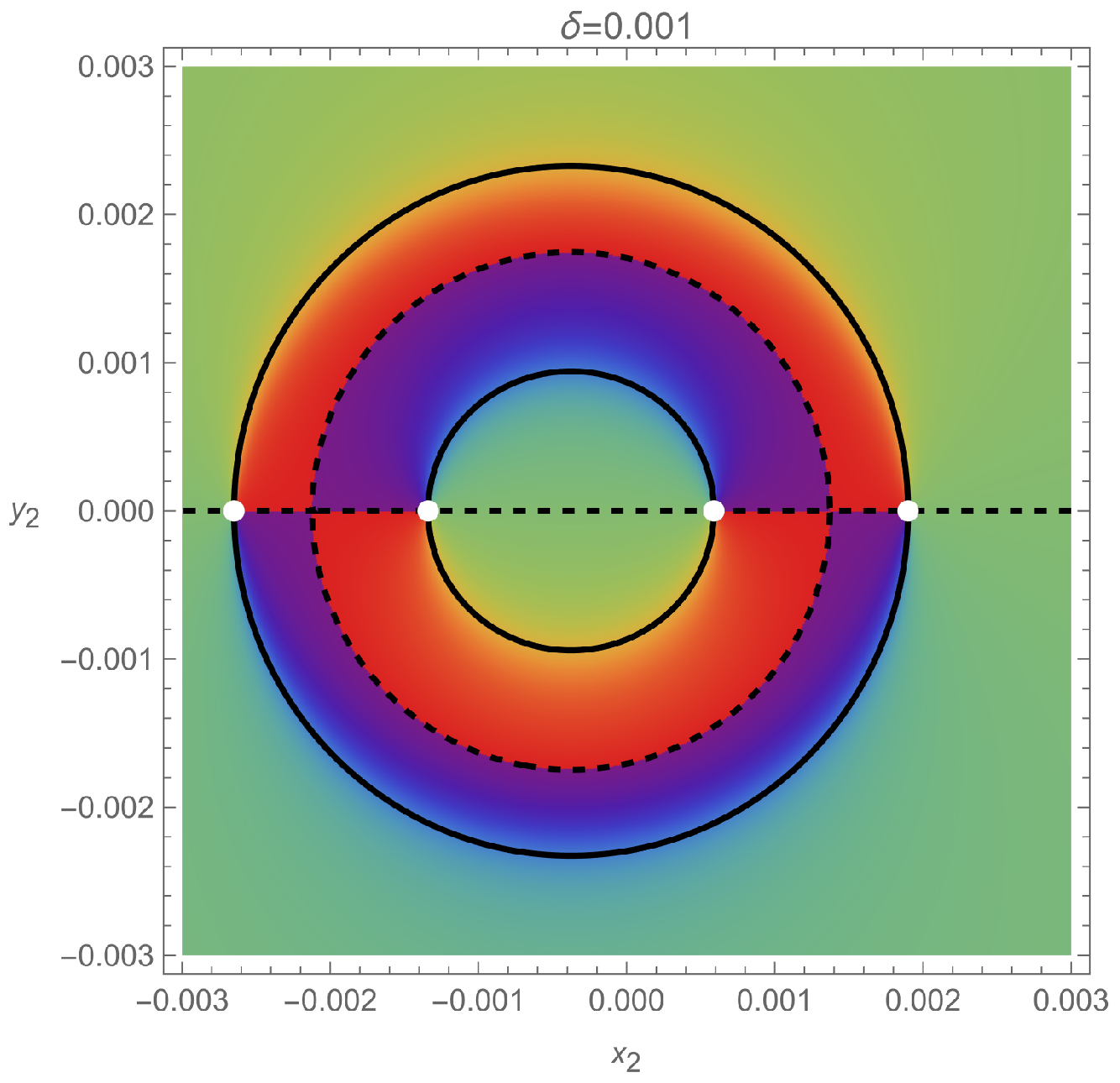

21). They are shown in

Figure 1. We use

mm for the beam waist and

nm for the wavelength of the beam. The solid (blue in color) and dot-dashed (green in color) curves represent the hyperbolas of Equation (

28) with

and

, respectively. The dashed (orange in color) and dotted (red in color) curves represent the hyperbolas of Equation (

30) with

and

, respectively. The second pair of hyperbolas can also be obtained from the first hyperbolas by rotating

. When we use modified polar coordinates

with

and

, we will have only one pair of hyperbolas of Equation (

28).

The denominator of the first term on the left-hand side of the equations in Equation (

28) or in Equation (

30) corresponds to the square of the intercept of the hyperbola. (Note that

). It is the half the distance

L between two curves in the hyperbola. Therefore, the distance becomes

For the fully coherent field,

, and for the completely incoherent field,

, the corresponding distances become

L approaches to zero when the fields are fully coherent. On the other hand, L approaches a constant proportional to the beam waist when the fields are completely incoherent. This behavior is also found in the first-order singularity of the Laguerre–Gauss beam.

3. Propagation of Correlation Singularities

The correlation of the wave changes as the beam propagates. Since the relevant cross-spectral density changes in z, the singular structure of the cross-spectral density also depends on z. The z-dependence follows as a straightforward generalization of the case.

We use the scalar field in Equation (

11) with

and

. In the calculation of the cross-spectral density, the Gouy phase does not contribute to the integration since the Gouy phase is only a function of

z while the integration in

W is over

and

. The resulting spectral density is the form of

where

is defined as

and

are defined in Equation (

7) and in Equation (

8), respectively. Since the integration variables are

and

, we arrange the exponential part in terms of manageable forms of

and

. To perform the integration, we first consider the exponential part of the integrand in Equation (

34). This exponential factor can be simplified as

where

a,

b, and

A are defined as

Therefore, a, b, and A are all dependent on z. In the limit of , the variables above become , , , , and , and thus we recover the definitions of the previous section.

As in the previous section, we can perform the similar calculations on the cross-spectral density

, as well as the hyperbolas representing correlation singularities. Detailed calculations can be found in

Appendix A. The results are presented below.

Two pairs of the hyperbolas are

where

and

are

The structure of these singularities of the order (

) of the Laguerre–Gauss beam has two pairs of hyperbolas with two values of

, while the structure of the first-order (

) singularity of the beam has only one pair of hyperbolas [

11].

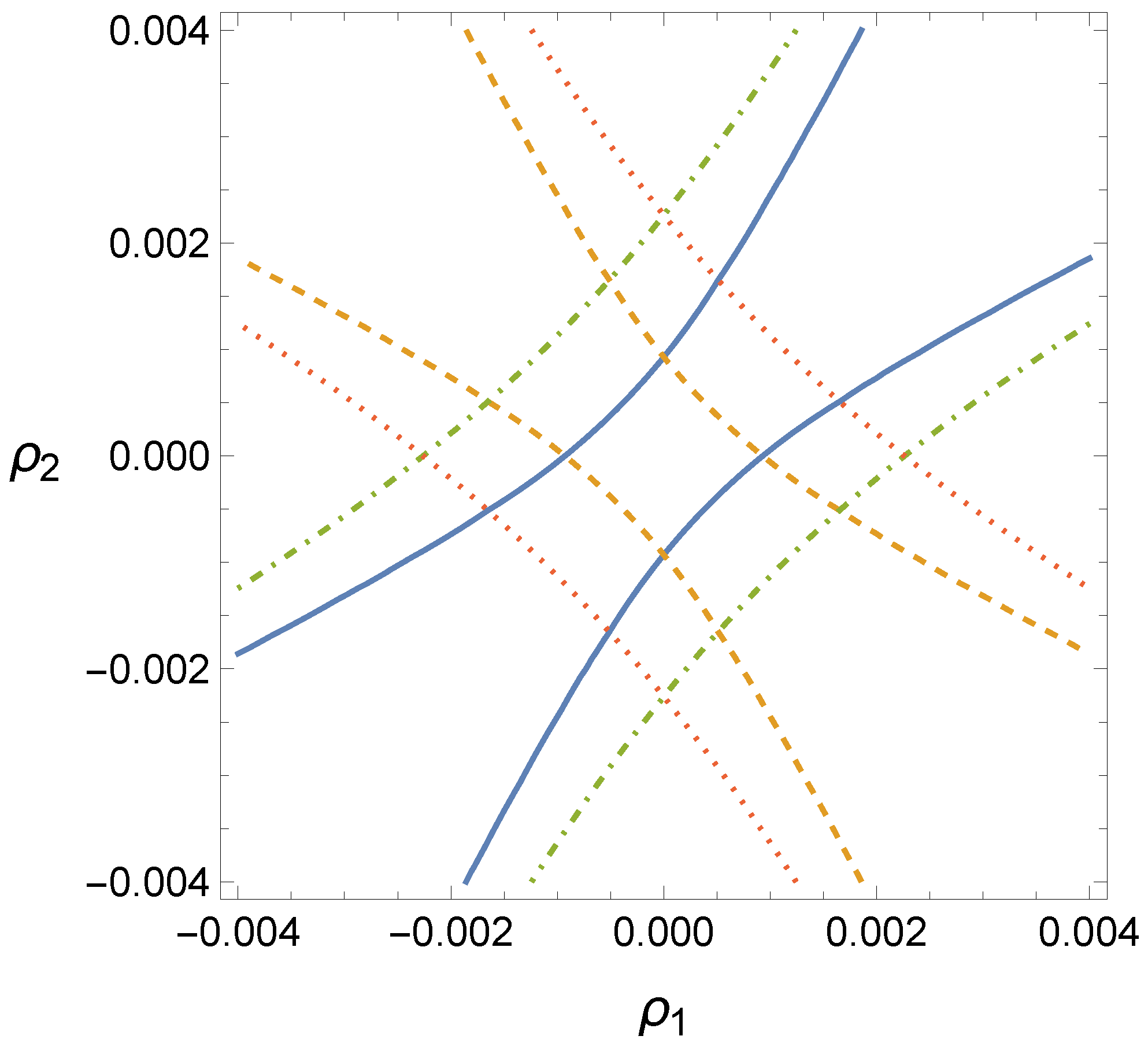

In

Figure 2, we use the same values of

mm,

mm, and the beam wavelength

nm as in Ref. [

11] for comparison. We fix three different values of

for each graph and

can be obtained from

. We use the values of

0.35 mm,

0.5 mm, and

1.5 mm for three graphs. The first graph in

Figure 2 shows that the singularities disappear around

m and

m, and then reappear around

m and

m. For some short range of

z, there is no singular behavior. In the second graph, only one of the singularities disappears near

m, and then reappears around

m. No disappearance or reappearance occurs in the third graph. Similar behaviors can also be found in Refs. [

10,

11].

The topological charges (angular momenta) associated with vortices cannot disappear or reappear. The disappearance or the reappearance of vortices only emerges due to the nature of spectral density of the two relative positions and . After the beam interacts with air molecules, the associated topological charges will eventually disappear and will not reappear. Their angular momentum is transferred to surrounding medium. Until then, the singularity representing angular momentum has propagated over considerable distances, conserving angular momentum throughout the propagation.

4. Relation Between Complex Degree of Coherence and the Parameter

In the beam-wander model, the parameter reflects the magnitude of beam wander. It is also an important parameter relating to partial coherence of the wave. When , the beam is fully coherent, and when , the beam is completely incoherent as mentioned earlier. Therefore, the parameter is related to the complex degree of coherence . We investigate how the degree of coherence depends on the parameter during the propagation of the Laguerre–Gauss beam in the cross-spectral density.

The normalized complex degree of coherence is defined as

where

with a fixed

z and

. The Hermiticity of cross-spectral density makes the expression of

simpler. From

, we know that

and

are real and nonnegative. These properties can be checked in Equation (

38). The imaginary part of the cross-spectral density in Equation (

38) vanishes when

and

. This is what we expected since

is a spectrum. In Equation (

38), we can find

where

and

for

are defined as

As we see in the previous section, the separation of the exponential and the non-exponential parts of

, and

makes the calculation of

simpler. The separated exponential factors are independently treated for the calculation of

. We will consider the absolute value of

or

. The relation between the complex degree of coherence,

, and the

parameter can be obtained from Equation (

41).

For the exponential part,

and

in Equations (

42) and (

38) contain the position variables

and

. It is more convenient to factor out the position variables from other variables in the numerical calculation of

. We also extract the exponential factors from Equations (

A9), (

A10), and (

A11), and relabel

in terms of the position variables

and

as

. Similarly, we relabel

and

in Equation (

A7) as

and

, respectively. Therefore, the overall exponential factor can be expressed in the form of

The imaginary part of the exponential in the numerator disappears in the absolute value of the exponential. The final result for a given

z becomes

The non-exponential factor can be found in Equation (

A8). The real and the imaginary parts can be clearly separated and easily identified in the equation. The form of the non-exponential factor can be written as

where

and

are

where the parenthesis,

, is canceled out by the same factor in

of Equation (

A8).

Therefore, the absolute value of the complex degree of coherence becomes

depends on

in a very complicated way in Equation (

49).

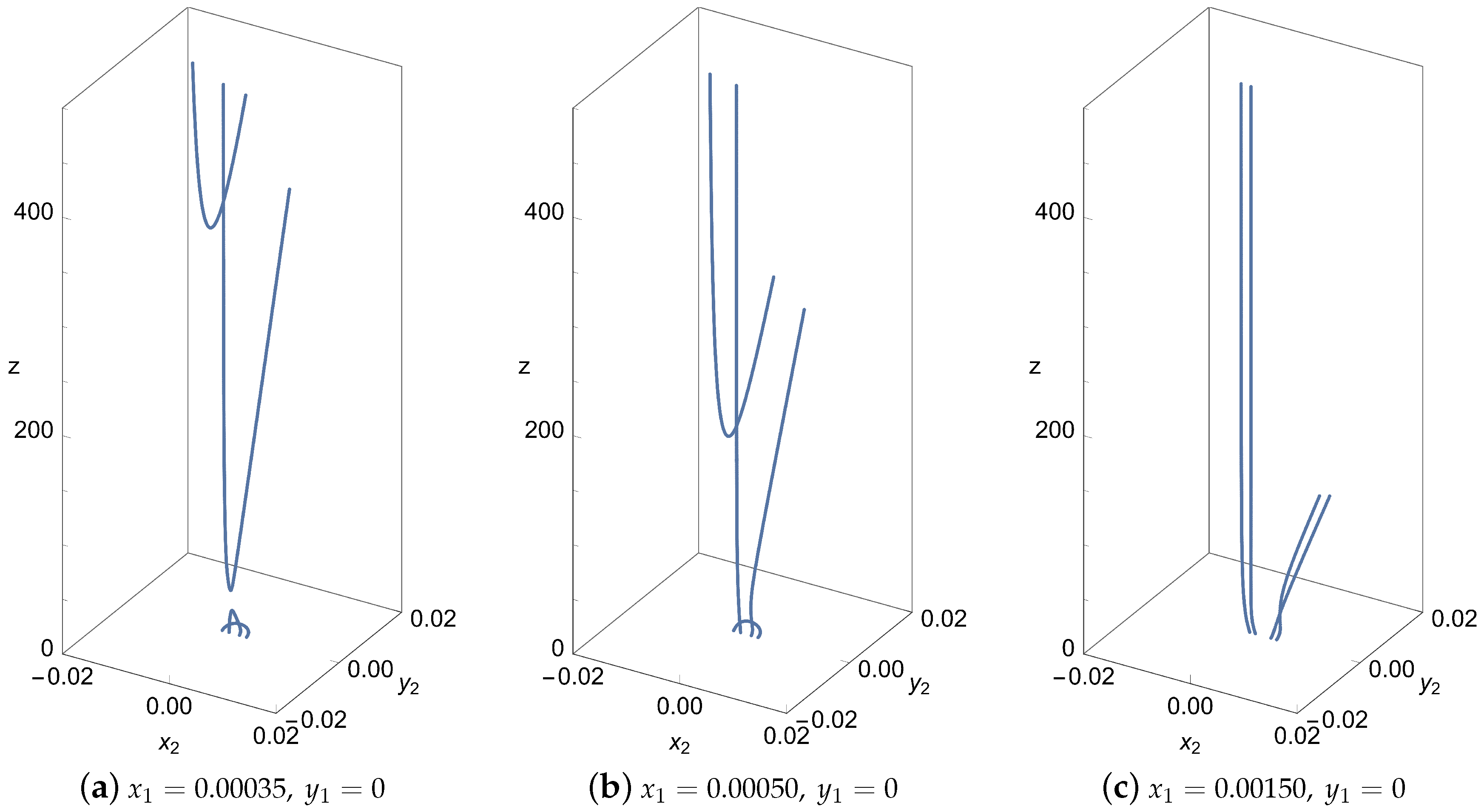

Figure 3 shows the absolute of the complex degree of coherence

in terms of the correlation parameter

for

mm and

nm. The first graph of

Figure 3 shows the relation between

and

for the fixed value of

with the

range of

. We change

for four different values of

z as

for

,

for

,

for

, and

for

, and each represented as solid (blue in color), dashed (orange in color), large-dashed (green in color), and dot-dashed (red in color) curves, respectively. The reason why we choose increasing coordinates of

is that the beam expands as it propagates. (The beam width becomes 8.4 mm at

m.) When we choose the same coordinates of

for all four plots (only four different coordinates of

z in this case), the degree of coherence becomes only slightly better in propagation (for bigger

z), although we do not include this result here.

The second graph of

Figure 3 shows the relations for four different values of

with the fixed value of

and

. When we change the coordinates of

as

,

,

, and

,

starts a flat line to gradually lowering curves as seen in the figure, and each represented as solid (blue in color), dashed (orange in color), large-dashed (green in color), and dot-dashed (red in color) curves, respectively. As

gets farther from

, the degree of coherence decreases as

increases as expected. However, the curves converge to certain values not to zero as

increases for

closer to

.

This behavior follows directly from the definition of

in Equation (

41). When

, the

-dependence cancels between the numerator and the denominator. This is due to the nature of the probability density function

, which contains

in the denominator and in the exponential function in Equation (

5). The

in the denominator of the density function cancels out because it is common to all three

W’s in the definition of

. On the other hand, the

in the exponential function of the density function does not cancel. After performing

and

integration, it is spread over all the expressions of the positions

and

as in Equation (

38). The

-dependence is implied in the expression of

A in Equation (

37). (Note that

a and

b also depend on

through

A). The effect of

is relatively smaller in

A for large

than for small

. Therefore,

stays almost constant for large

to the case of

since

W’s are canceled out in the numerator and in the denominator in the definition of

. Graphs in

Figure 3 are only for the case when

close to

. On the other hand,

approaches zero (very) fast when

increases for

far from

as expected, although we do not show it here. This coherence is related most to the relative distance between two observation points. When

, we can understand this more clearly from Equation (

17). The exponential factors in Equation (

17) can be changed to

The distance between two positions

and

is defined as

. The coherence is maximized when

, and completely disappeared when

. However, when

, the coherence is not easily understood from the exponential part of Equation (

38) because the exponential function does not have a simple dependence on the relative distance. Nevertheless, the degree of coherence

exhibits this behavior. We emphasize that the general behavior of

versus

is still valid.

(1) Checking the range of coherence

As shown in

Figure 3, the convergent value of

depends on the relative positions of two points

and

. When the two points are close, the coherence persists for a larger value of

in the turbulent atmosphere. When two positions are further apart, the degree of coherence

converges to zero very fast, although graphs are not shown here. Therefore, for a fixed point,

, we can determine the range of coherence by setting a convergent value of

.

(2) Checking the validity range of beam-wander model in turbulent air

Once an experiment is performed on the coherence, we can determine the parameter since it is the only free parameter in the expression of . A series of measurements (at different positions of at a fixed point ) of the coherence can give a series of values of . The experiments will determine whether the parameter is a constant or it has a functional dependence on positions. We may find out the validity range of the beam-wander model from the experimental results. For these reasons, we encourage experimental physicists to do relevant experiments.

5. Orbital Angular Momentum Flux Density

The correlation-singular behavior is related to the vortex structure of the beam. The vortex carries angular momentum [

17,

18,

27,

28,

29]. The conservation of angular momentum in electromagnetic waves leads to the definition of the angular momentum flux density, as described in [

29,

30]. Now, we examine the angular momentum flux density of the beam in the beam-wander model.

Consider uniformly unpolarized, partially coherent waves with vortex structures in the paraxial limit. For unpolarized waves, the spin component of the total angular momentum is considered to be zero, leaving only the orbital angular momentum. As defined in [

29], the dyadic form of the electric cross-spectral density tensor for such waves is

where

is a scalar cross-spectral density. The corresponding orbital angular momentum (OAM) flux density is [

12,

29]

Furthermore, to eliminate the effect of intensity dependence, we introduce a normalized flux density of the beam. The corresponding normalized OAM flux density is defined as [

12]

where

is the

z-component of the Poynting vector which can be expressed as

For the calculation of the OAM flux density of the Laguerre–Gauss beam in the beam-wander model, we use the cross-spectral density given in Equation (

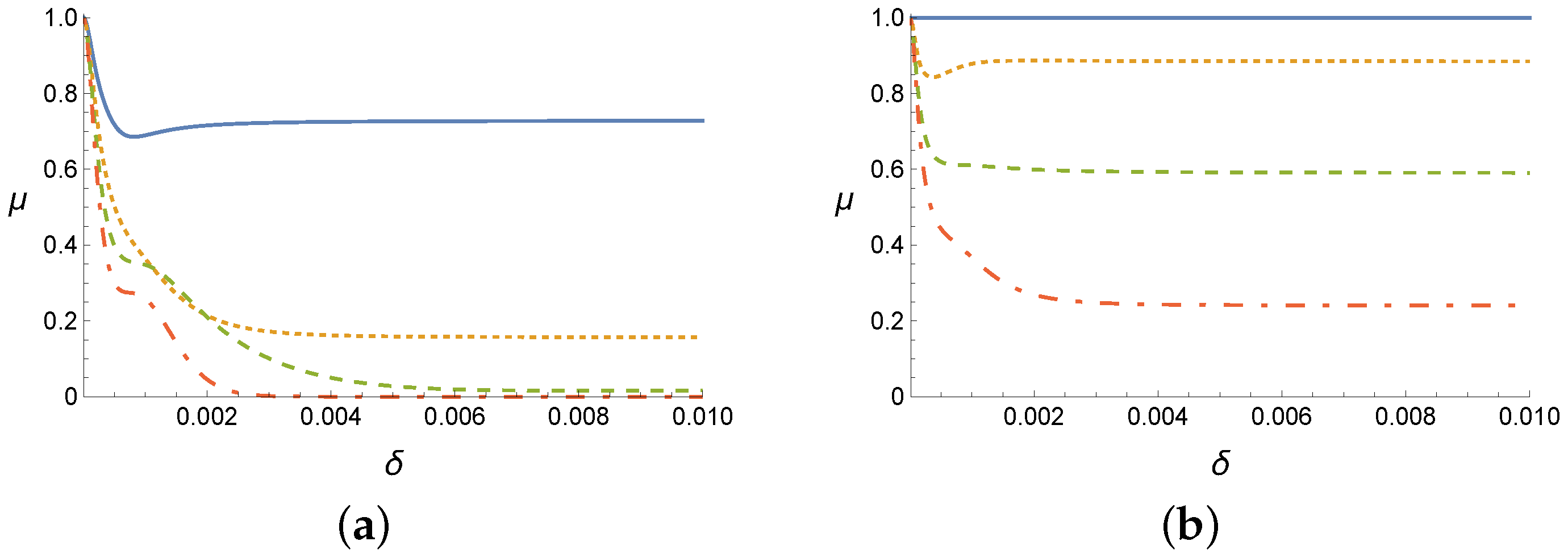

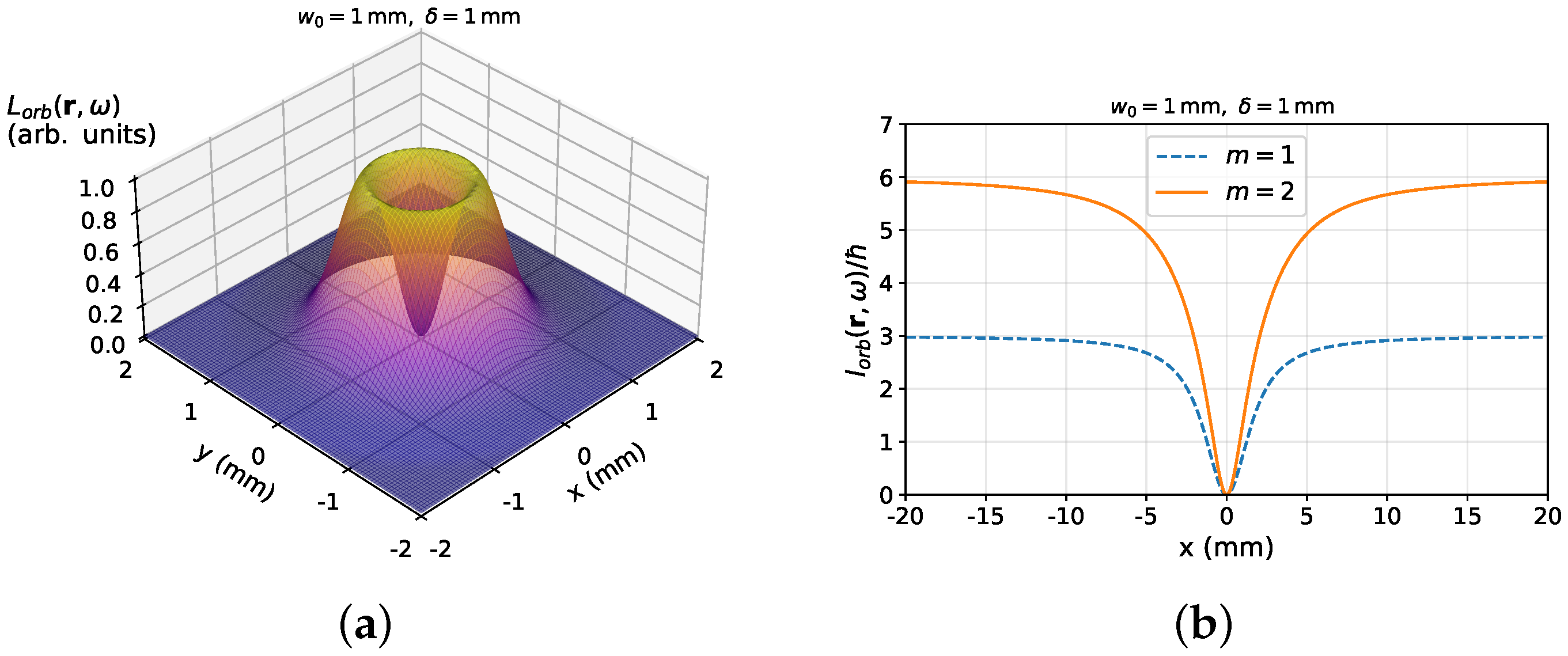

17). The OAM flux density and its normalized density are shown in

Figure 4. As shown in

Figure 4a, the OAM flux density

increases rapidly from the origin to a maximum on a circle, then decreases rapidly thereafter, similar to the previous study [

29]. The difference is that the slope of the circular peak is steeper in this study with

than in the previous study with

.

The normalized OAM flux density

is shown in

Figure 4b. The density

for the cross section of the field increases quadratically near the center of the beam, and it converges to a constant as the distance from the center increases. This behavior has also been observed in the previous study, and there is no qualitative difference. When we compare, this constant is twice the corresponding constant in [

29]. This is what we expected because this constant reflects the topological charge of

, whereas the constant in [

29] corresponds to the topological charge of

. We confirm that the normalized OAM density is proportional to the value of

m, as discussed in [

12]. The normalized OAM flux density in [

12] is expressed as

, and its convergent formula becomes

Figure 4b verifies this formula. The normalized OAM density is a useful tool for investigating the topological charge, i.e., the orbital angular momentum of the beam. The general behaviors of

and

for the field in [

12,

29] are verified here.

6. Conclusions

In this study, we derive the explicit expression for the correlation singularities of the partially coherent field of the Laguerre–Gauss beam of order and in the beam-wander model in propagation. These singularities form two pairs of hyperbolas in the - plot. These singularities can disappear and reappear during propagation. This behavior depends on several variables including the positions and , the beam-wander model parameter , and wave properties such as the beam waist and the wavelength . Although the detailed singular behavior is difficult to predict, the conservation of topological charge remain robust.

We also derive and investigate the complex degree of coherence in propagation, especially in terms of the parameter . We find that the complex degree of coherence in propagation is sensitive to all the parameters we used in this model, namely, , , , as well as the two observation positions, and . We can also determine the range of coherence for a fixed point by excluding such sensitive regions of . A series of experiments on measuring the degree of coherence will allow us to check the validity range of the beam-wander model in the turbulent atmosphere.

Lastly, we study the orbital angular momentum using the Laguerre–Gauss beam in this model. As in previous studies [

12,

29], we observed general behaviors of the orbital angular momentum density and the normalized density.