Harmonic Suppression Method for Optical Encoder Based on Photosensitive Unit Parameter Optimization

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Analysis and Experimental Results

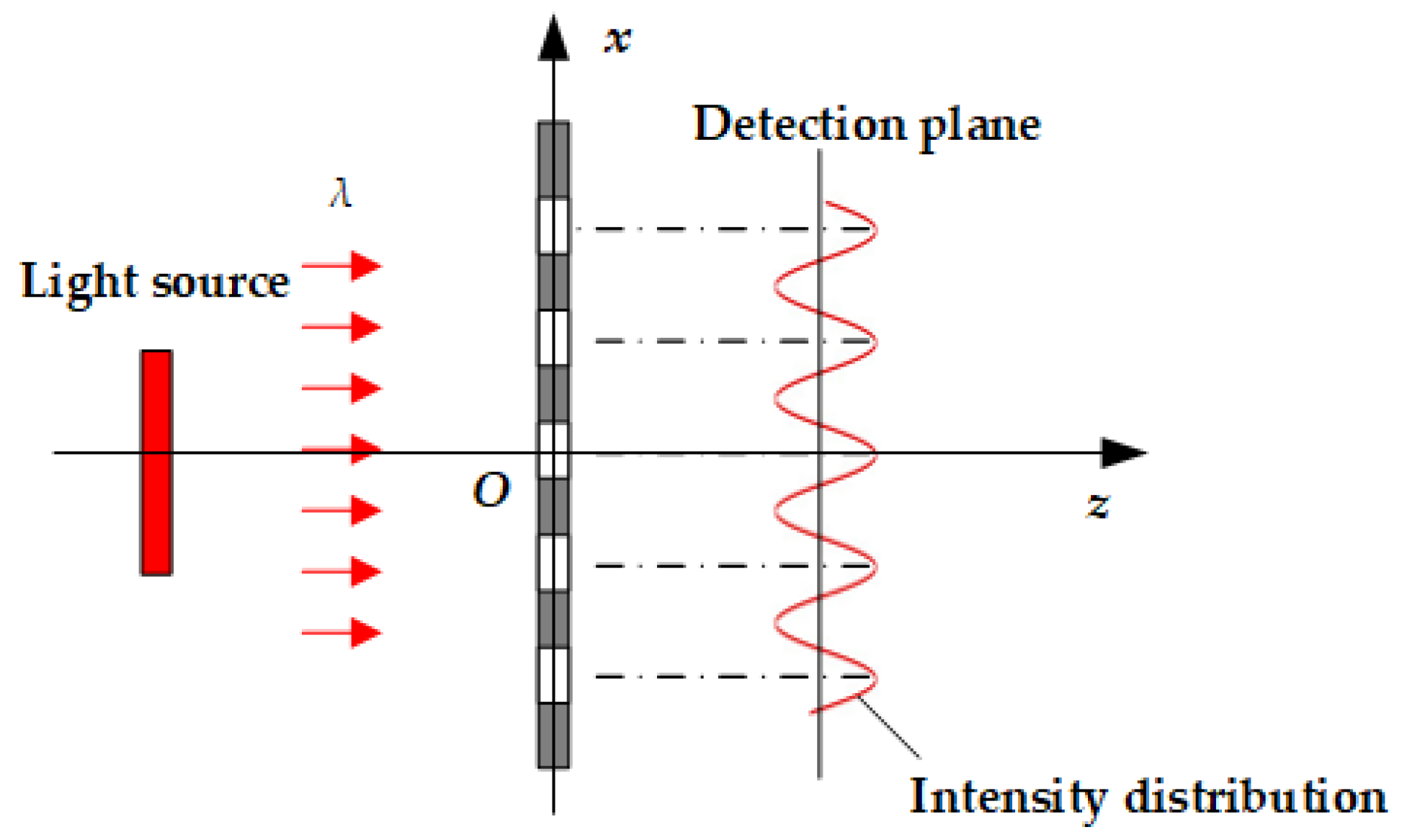

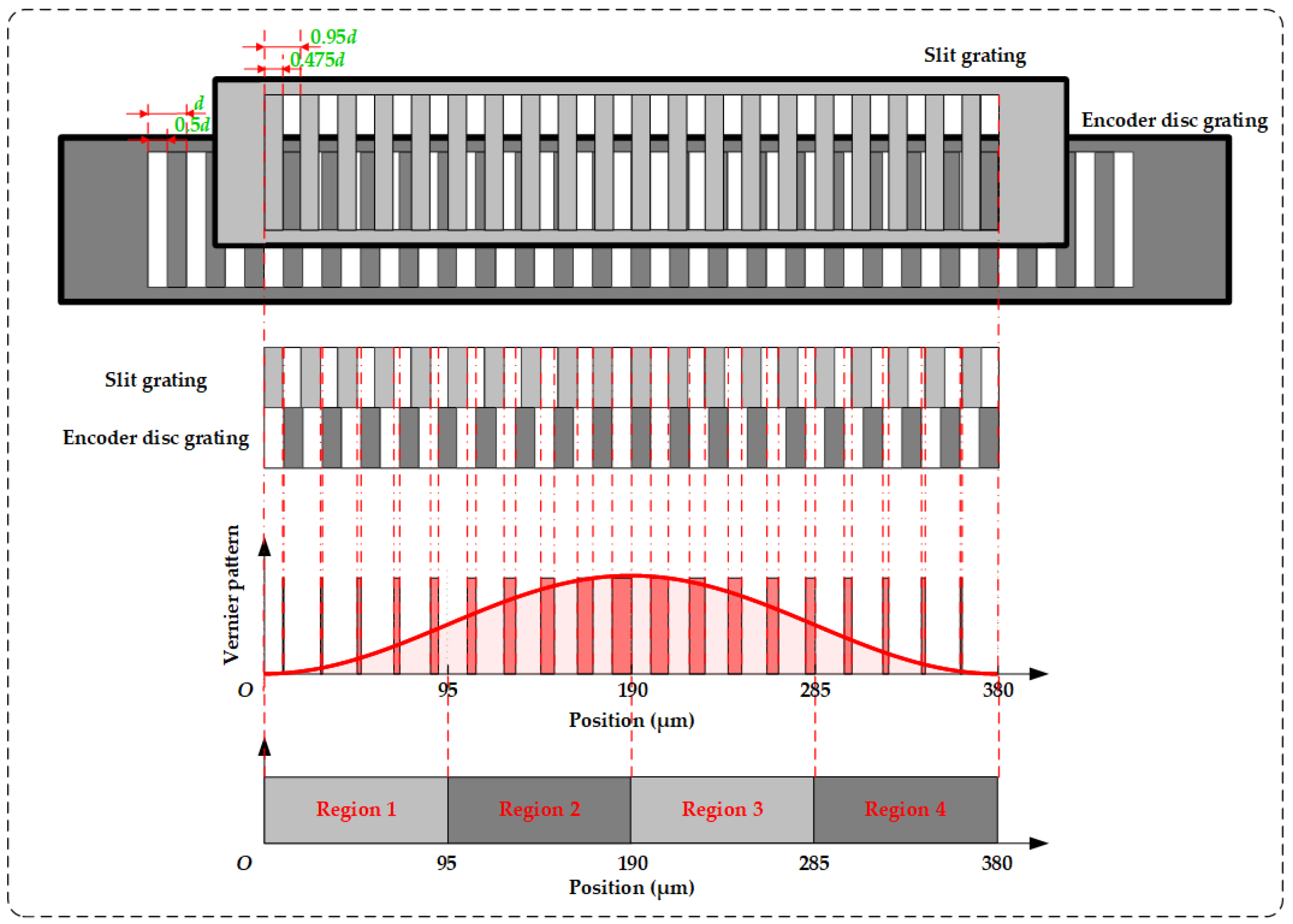

2.1. Theoretical Analysis of Grating Self-Imaging

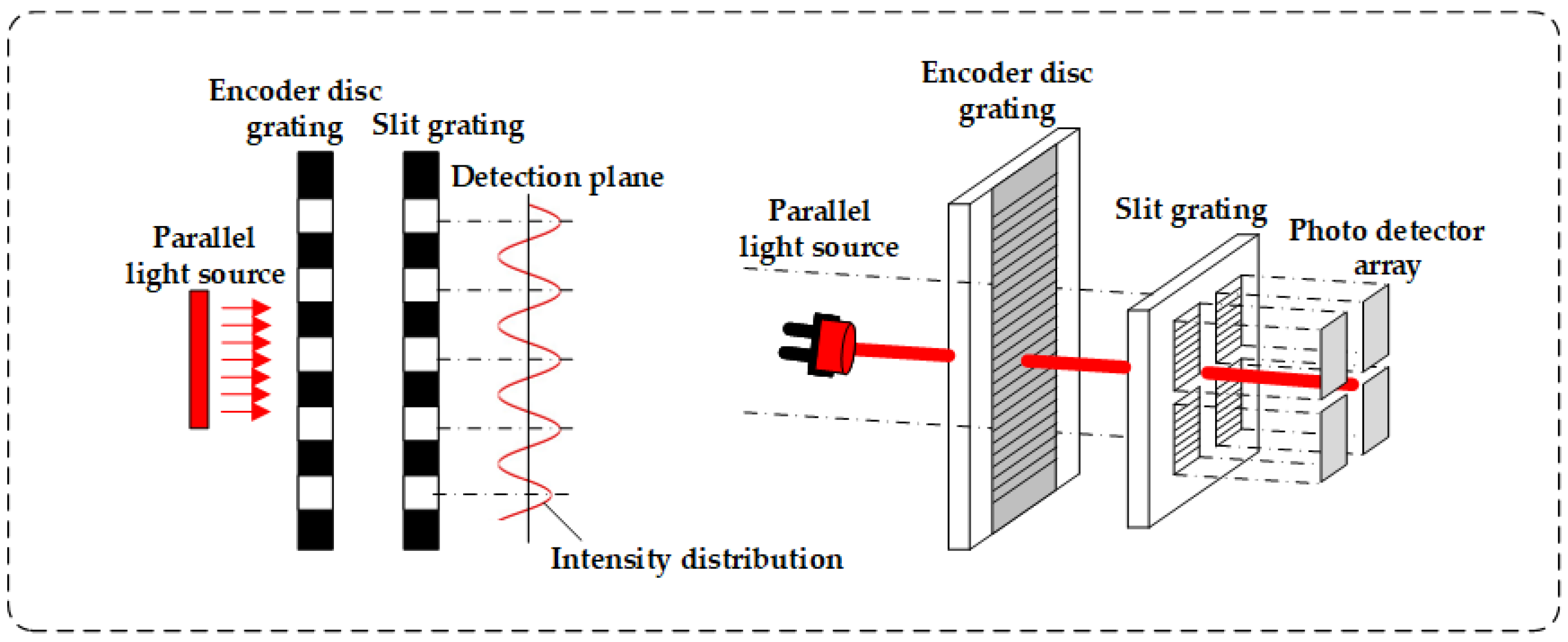

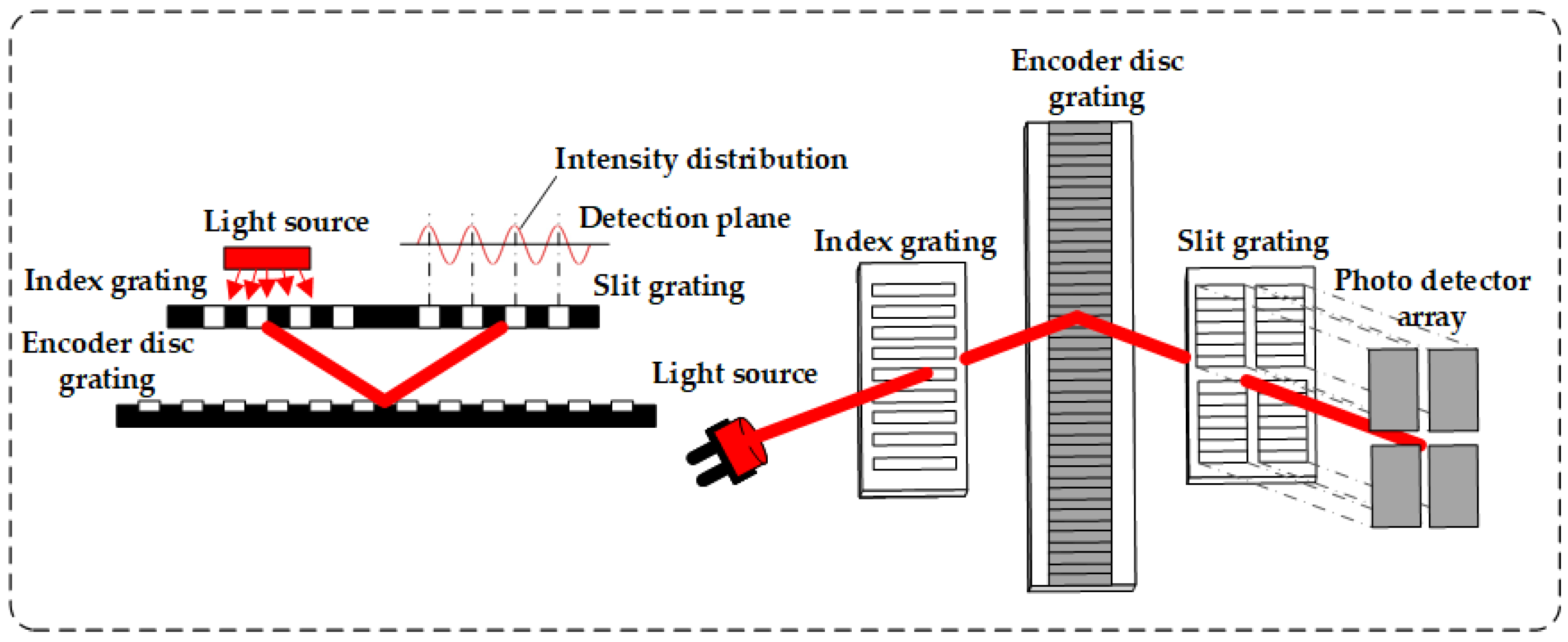

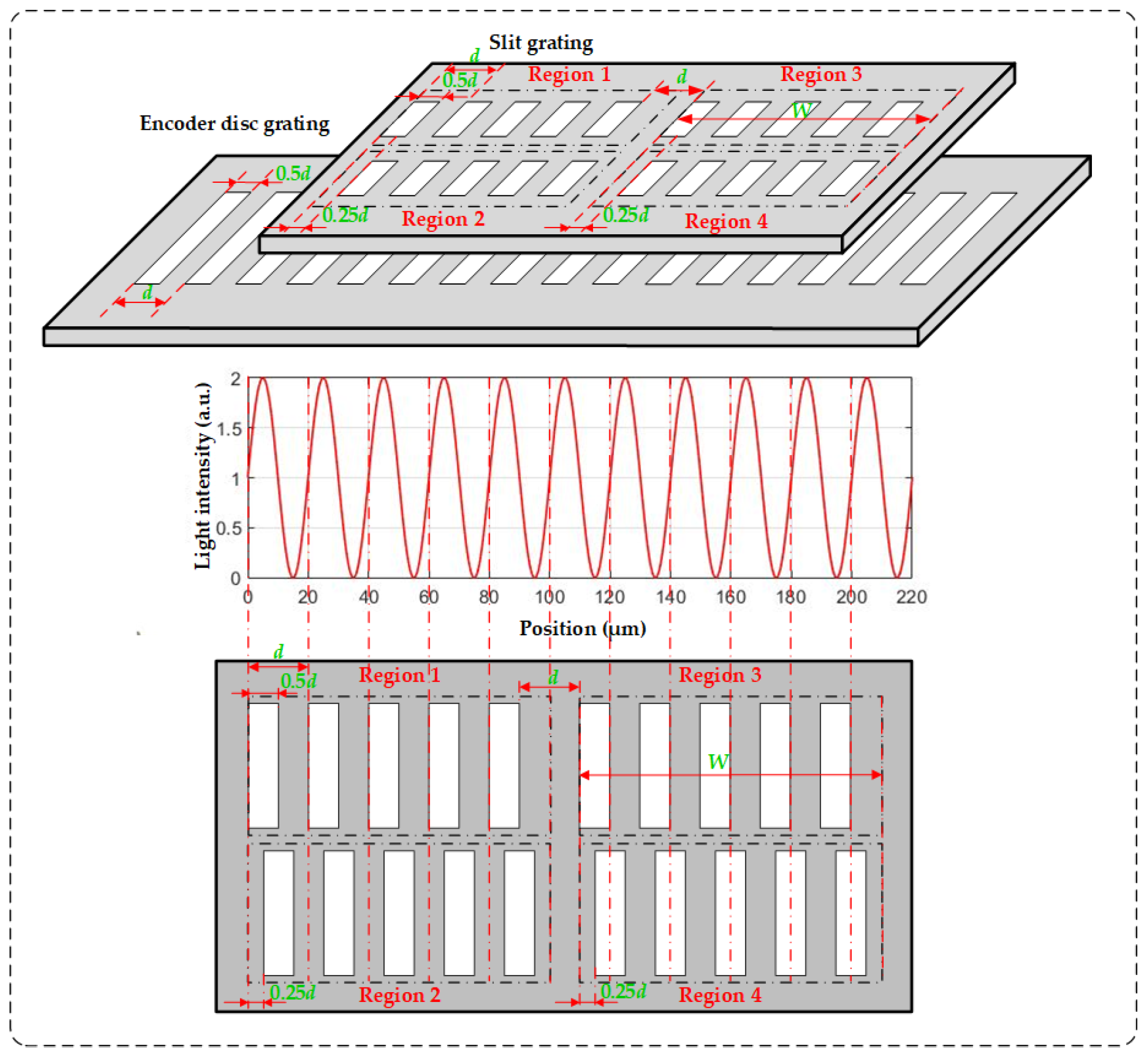

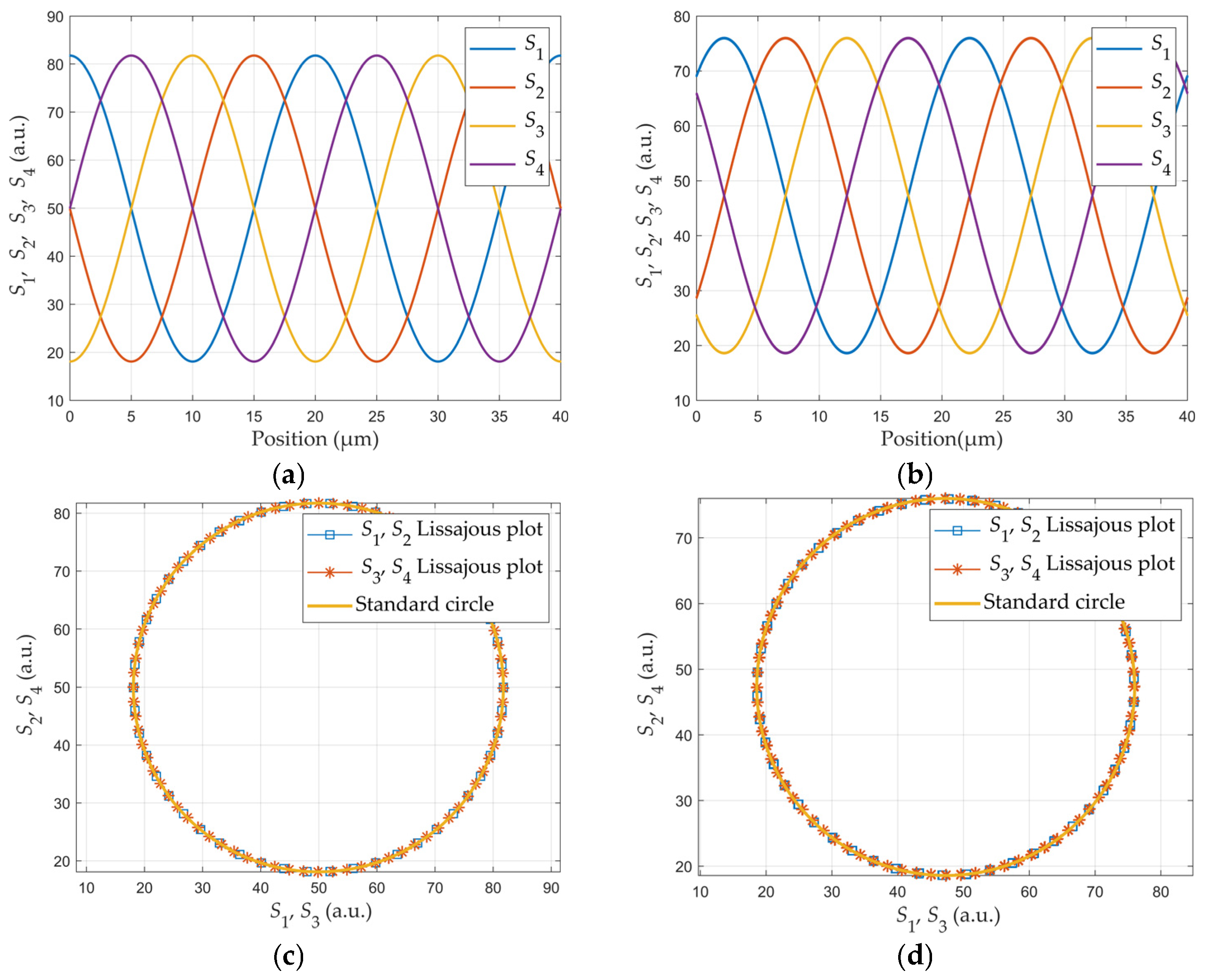

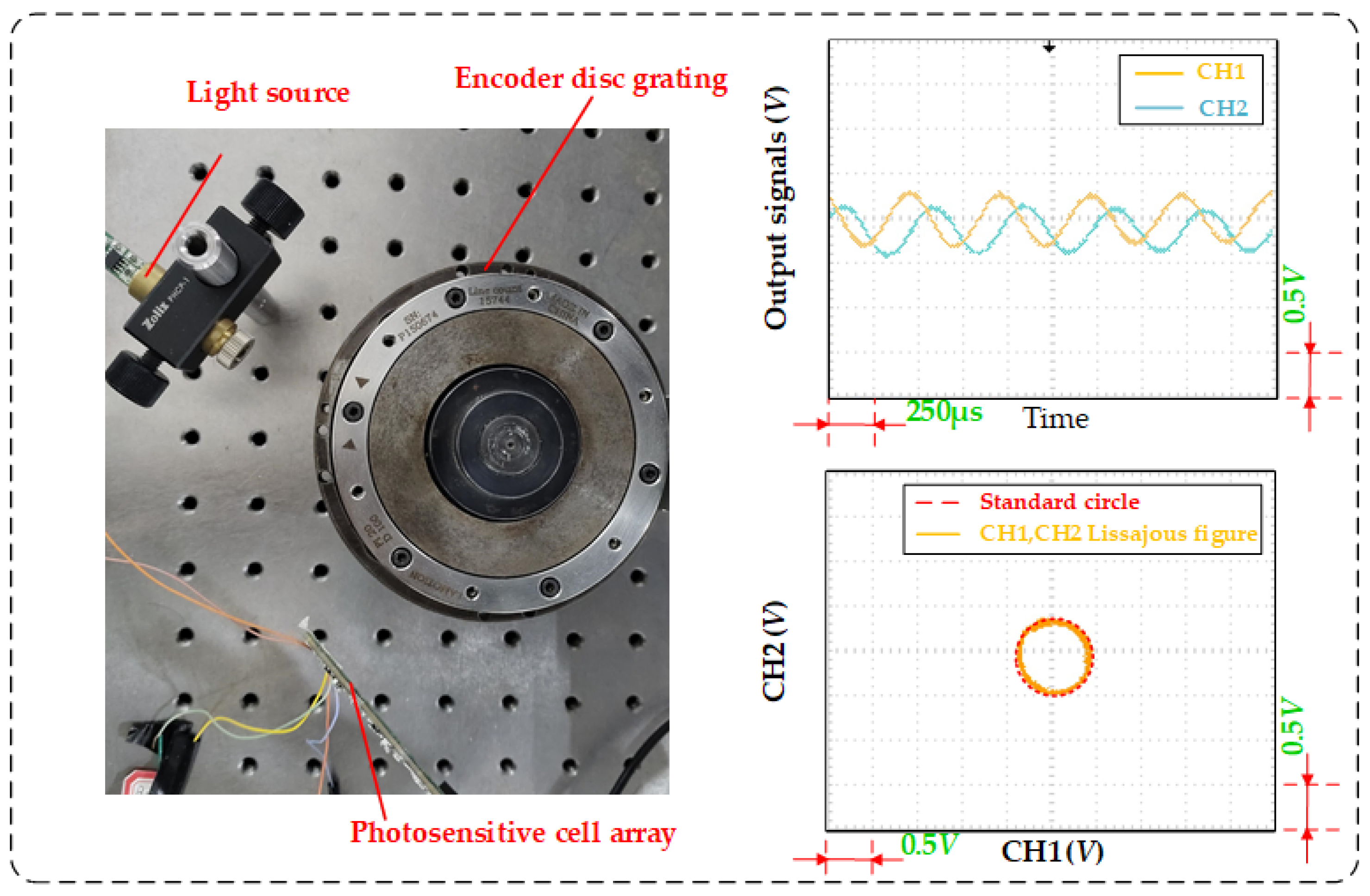

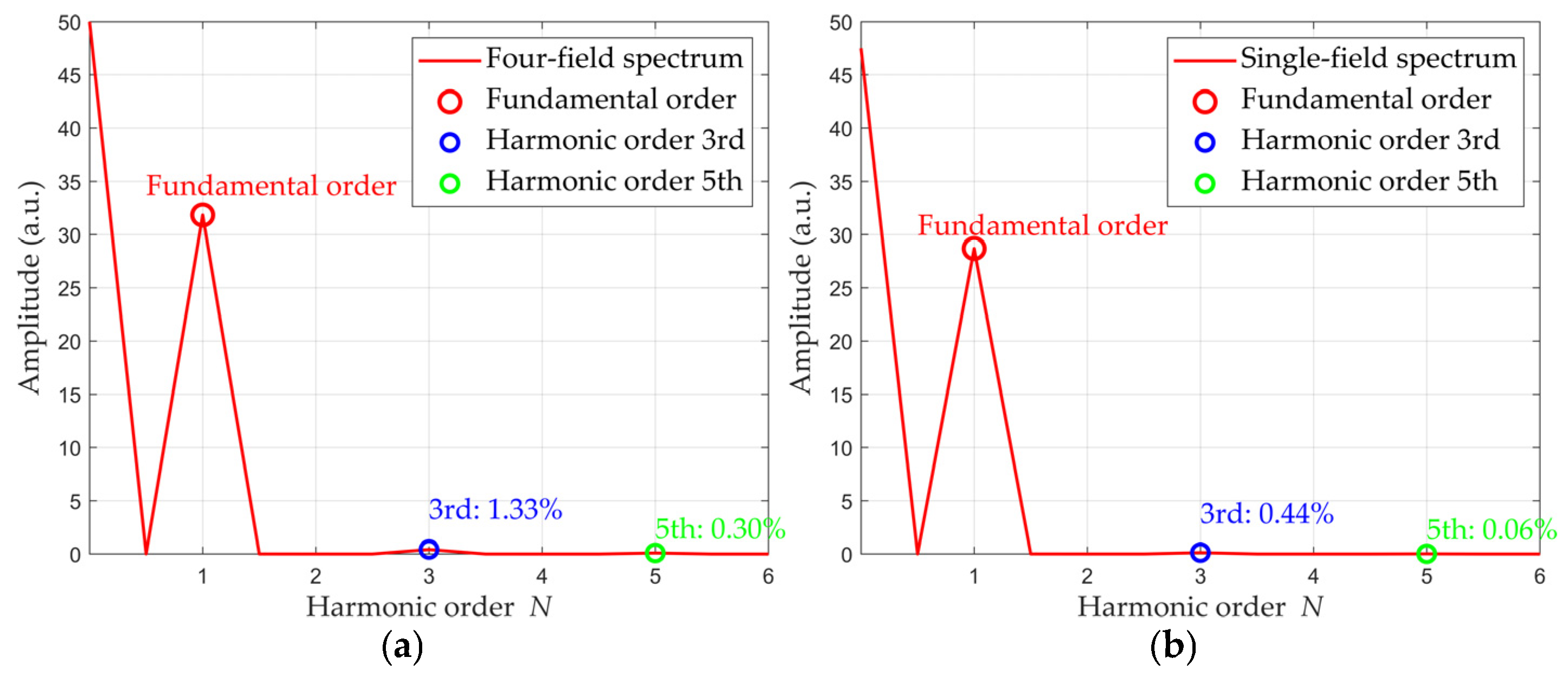

2.2. Four-Field and Single-Field Scanning Methods for Gathering Grating Self-Imaging

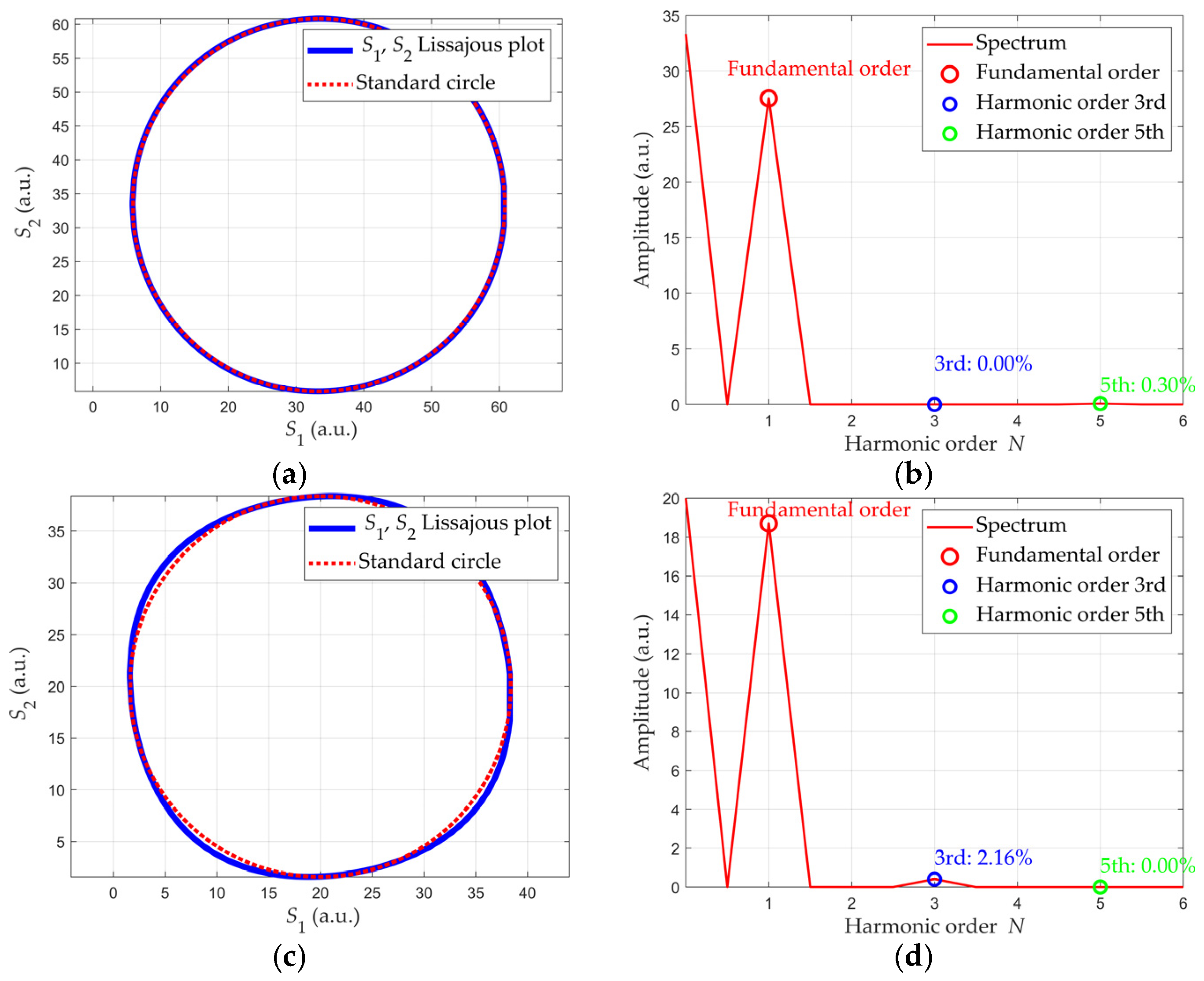

2.3. Results and Discussion

3. Improved Method

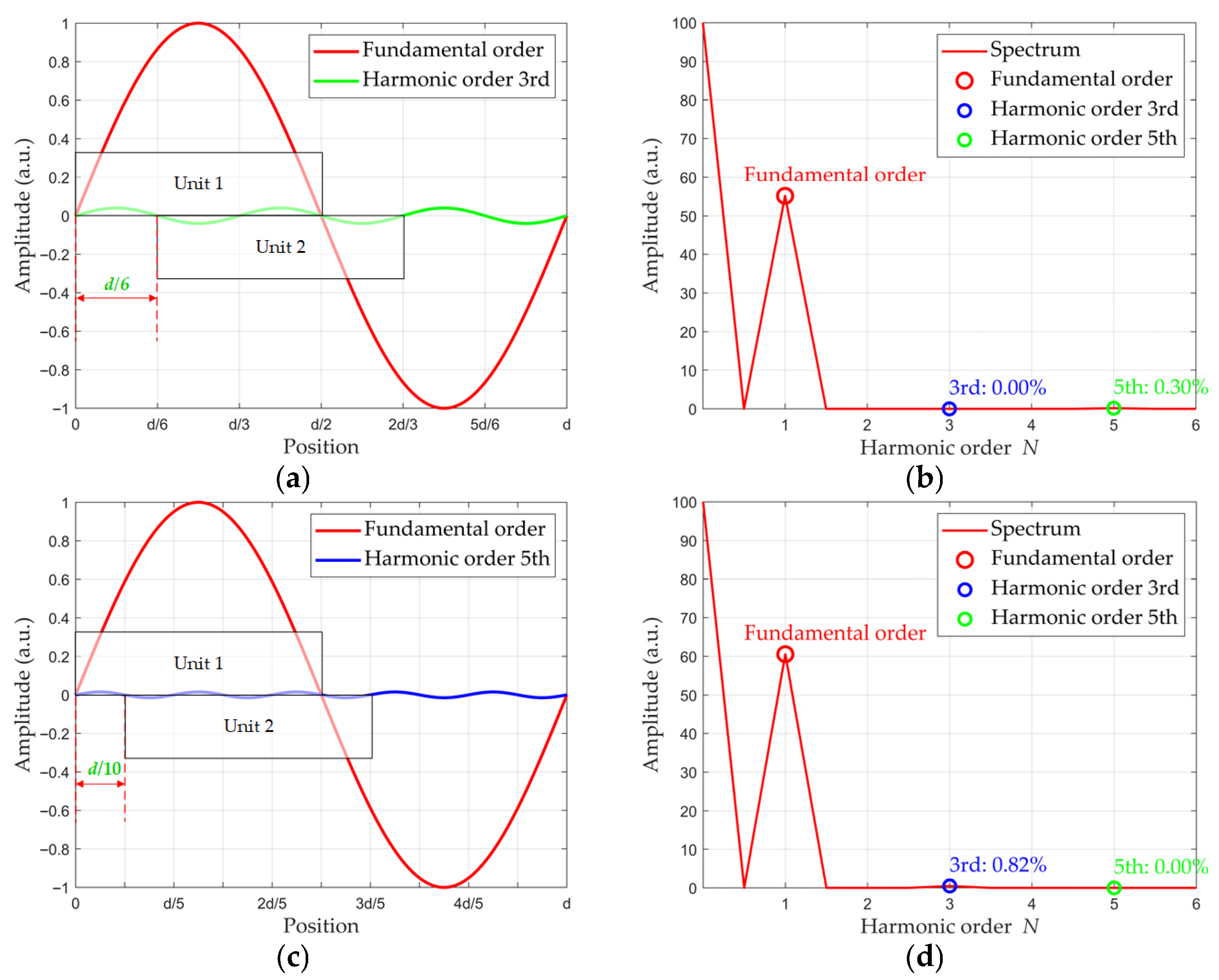

3.1. Influence of the Width of the Photosensitive Unit

3.2. Influence of the Photosensitive Unit Offset

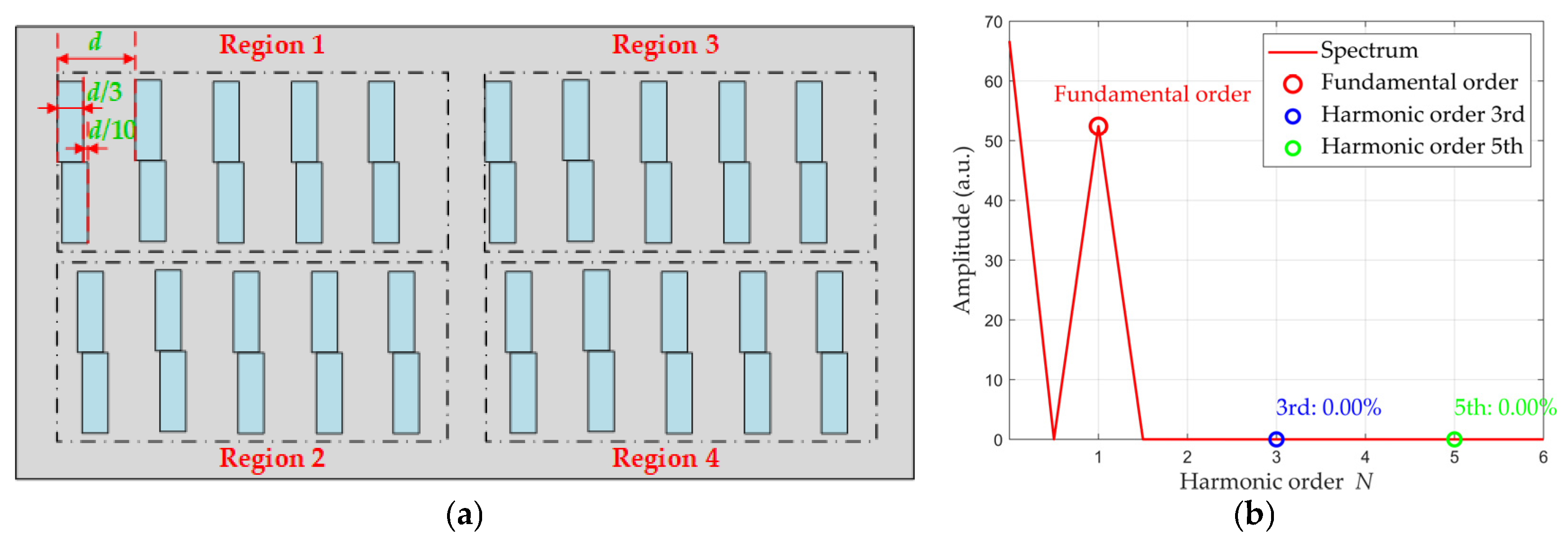

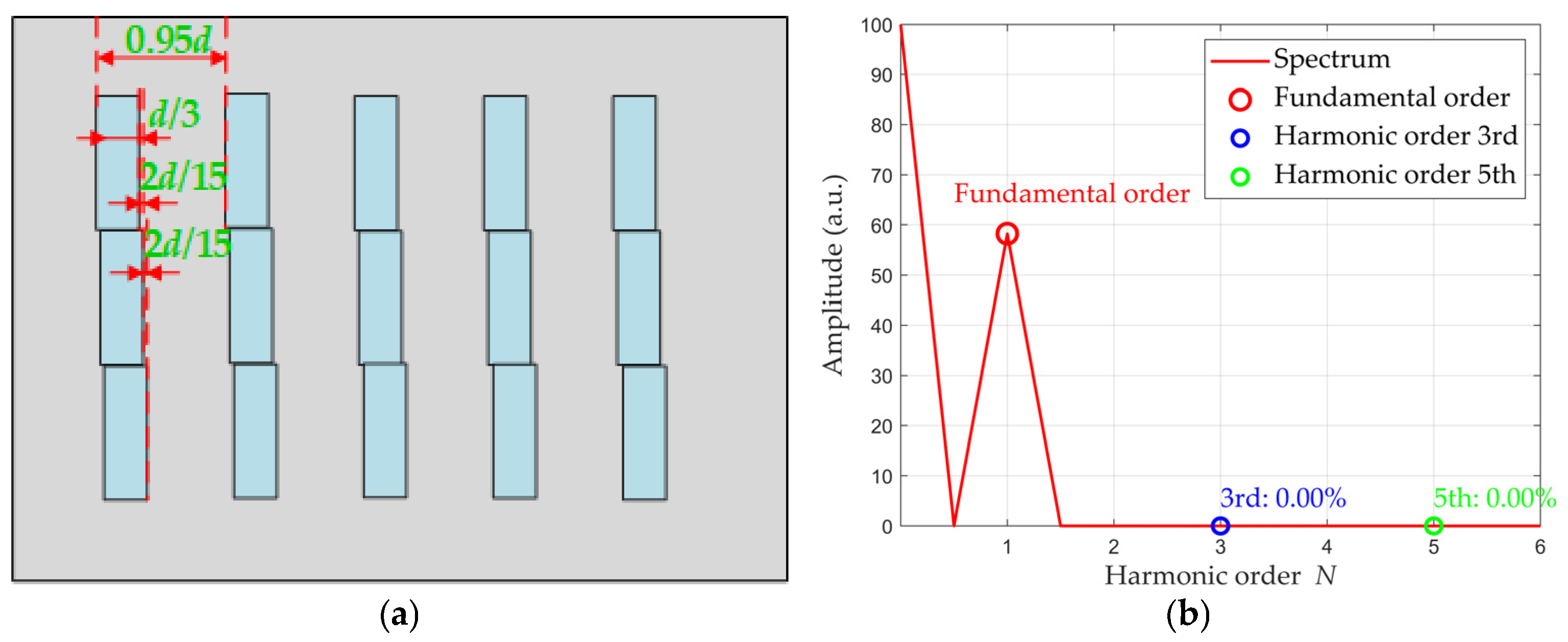

3.3. Optimization Design Based on Photosensitive Unit Width and Offset

4. Conclusions and Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kumar, A.S.A.; George, B.; Mukhopadhyay, S.C. Technologies and Applications of Angle Sensors: A Review. IEEE Sens. J. 2021, 21, 7195–7206. [Google Scholar]

- Gurauskis, D.; Przystupa, K.; Kilikevičius, A.; Skowron, M.; Matijošius, J.; Caban, J.; Kilikevičienė, K. Development and Experimental Research of Different Mechanical Designs of an Optical Linear Encoder’s Reading Head. Sensors 2022, 22, 2977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kao, C.-F.; Huang, H.-L.; Lu, S.-H. Optical encoder based on Fractional-Talbot effect using two-dimensional phase grating. Opt. Commun. 2010, 283, 1950–1955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crespo, D.; Alonso, J.; Bernabeu, E. Generalized grating imaging using an extended monochromatic light source. J. Opt. Soc. Am. A (Opt. Image Sci. Vis.) 2000, 17, 1231–1240. [Google Scholar]

- Kyvalsky, J. The self-imaging phenomenon and its applications. In Photonics, Devices, and Systems II; SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2003; Volume 5036. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, H.; Chen, X.; Liu, C.; Cai, G.; Wang, W. A survey on the grating based optical position encoder. Opt. Laser Technol. 2021, 143, 107352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez-Brea, L.M.; Morlanes, T. Metrological errors in optical encoders. Meas. Sci. Technol. 2009, 19, 115104. [Google Scholar]

- Kao, C.-F.; Lu, M.-H. Optical encoder based on the fractional Talbot effect. Opt. Commun. 2005, 250, 16–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuzoe, Y.; Tsuji, N.; Yoshizawa, T. Error dispersion algorithms to improve angle precision for an encoder. Opt. Eng. 2002, 41, 2282–2289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rozman, J.; Pletersek, A. Linear Optical Encoder System With Sinusoidal Signal Distortion Below 60 dB. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2010, 59, 1544–1549. [Google Scholar]

- Ye, G.; Liu, H.; Jiang, W.; Li, X.; Jiang, W.; Yu, H.; Shi, Y.; Yin, L.; Lu, B. Design and development of an optical encoder with sub-micron accuracy using a multiple-tracks analyser grating. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 2017, 88, 015003. [Google Scholar]

- Van Hoang, H.; Le, H.T.; Jeon, J.W. A new approach based-on advanced adaptive digital PLL for improving the resolution and accuracy of magnetic encoders. In Proceedings of the 2008 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems, Nice, France, 22–26 September 2008; pp. 3133–3660. [Google Scholar]

- Ye, G.; Xing, H.; Liu, H.; Li, Y.; Lei, B.; Niu, D.; Li, X.; Lu, B.; Liu, H. Total error compensation of non-ideal signal parameters for Moiré encoders. Sens. Actuators A Phys. 2019, 298, 111539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ieki, A.; Hane, K.; Yoshizawa, T.; Matsui, K.; Nashiki, M. Optical encoder using a slit-width-modulated grating. J. Mod. Opt. 1999, 46, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ieki, A.; Matsui, K.; Nashiki, M.; Hane, K. Pitch-modulated phase grating and its application to displacement encoder. J. Mod. Opt. 2000, 47, 1213–1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, G.; Liu, H.; Fan, S.; Li, X.; Yu, H.; Lei, B.; Shi, Y.; Yin, L.; Lu, B. A theoretical investigation of generalized grating imaging and its application to optical encoders. Opt. Commun. 2015, 354, 21–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, G.; Liu, H.; Ban, Y.; Shi, Y.; Yin, L.; Lu, B. Development of a reflective optical encoder with submicron accuracy. Opt. Commun. 2018, 411, 126–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Hoang, H.; Jeon, J.W. An efficient approach to correct the signals and generate high-resolution quadrature pulses for magnetic encoders. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2011, 58, 3634–3646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, S.-Y.; Nam, K. PMSM control based on edge-field hall sensor signals through ANF-PLL processing. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2011, 58, 5121–5129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Wang, G.; Xu, D.; Zhao, N. ADALINE-Network-Based PLL for Position Sensorless Interior Permanent Magnet Synchronous Motor Drives. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2016, 31, 1450–1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.H.; Nguyen, H.X.; Tran, T.N.-C.; Park, J.W.; Le, K.M.; Nguyen, V.Q.; Jeon, J.W. An Effective Method to Improve the Accuracy of a Vernier-Type Absolute Magnetic Encoder. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2021, 68, 7330–7340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.W.; Nguyen, H.X.; Tran, T.N.-C.; Jeon, J.W. A Linear Compensation Method for Improving the Accuracy of an Absolute Multipolar Magnetic Encoder. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 19127–19138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heydemann, P.L.M. Determination and correction of quadrature fringe measurement errors in interferometers. Appl. Opt. 1981, 20, 3382–3384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, W.; Lin, Y.; Huang, Y. Research on Sinusoidal Error Compensation of Moire Signal Using Particle Swarm Optimization. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 14820–14831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.; Dai, J.; Zhang, H.; Mu, Y.; Chang, Y. Improving the subdivision accuracy of photoelectric encoder using particle swarm optimization algorithm. Opt. Quantum Electron. 2022, 54, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, H.; Cao, G.; Ding, H.; Li, K. Research on Particle Swarm Compensation Method for Subdivision Error Optimization of Photoelectric Encoder Based on Parallel Iteration. Sensors 2022, 22, 4456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lohmann, A.; Silva, D. An interferometer based on the Talbot effect. Opt. Commun. 1971, 2, 413–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hane, J.; Komazaki, I.; Ito, T.; Kuroda, Y.; Yamamoto, E. Ultra-compact encoder using Talbot interference. In Proceedings of the MEMS 2001, 14th IEEE International Conference on Micro Electro Mechanical Systems, Interlaken, Switzerland, 25 January 2001. Technical Digest, Cat. No.01CH37090. [Google Scholar]

- Hane, K.; Endo, T.; Ishimori, M.; Ito, Y.; Sasaki, M. Integration of grating-image-type encoder using Si micromachining. Sens. Actuators A 2002, 97–98, 139–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Yuan, B.; Wang, L. New displacement measurement method based on digital Moiré fringes formed by a single grating. Hongwai Yu Jiguang Gongcheng/Infrared Laser Eng. 2014, 43, 3404–3409. [Google Scholar]

- Iwata, K. Interpretation of generalized grating imaging. J. Opt. Soc. Am. A 2008, 25, 2244–2250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Width | Fundamental Amplitude (a.u.) | 3rd-Harmonic Amplitude (a.u.) | 3rd-Harmonic Component |

|---|---|---|---|

| d/3 | 27.56269 | 0.00074 | 0.00% |

| 1.02d/3 | 27.89019 | 0.02603 | 0.09% |

| 1.05d/3 | 28.35835 | 0.06576 | 0.23% |

| 1.1d/3 | 29.07651 | 0.13061 | 0.45% |

| 1.2d/3 | 30.27108 | 0.24887 | 0.82% |

| 0.98d/3 | 27.22359 | 0.02722 | 0.10% |

| 0.95d/3 | 26.69198 | 0.06695 | 0.25% |

| 0.9d/3 | 25.74734 | 0.13171 | 0.51% |

| 0.8d/3 | 23.65022 | 0.24993 | 1.06% |

| Width | Fundamental Amplitude (a.u.) | 5th-Harmonic Amplitude (a.u.) | 5th-Harmonic Component |

|---|---|---|---|

| d/5 | 18.70334 | 0.00026 | 0.00% |

| 1.02d/5 | 19.02553 | 0.00573 | 0.03% |

| 1.05d/5 | 19.50316 | 0.01467 | 0.08% |

| 1.1d/5 | 20.28373 | 0.02924 | 0.14% |

| 1.2d/5 | 21.78408 | 0.05588 | 0.26% |

| 0.98d/5 | 18.3782 | 0.00625 | 0.03% |

| 0.95d/5 | 17.88507 | 0.01519 | 0.08% |

| 0.9d/5 | 17.04915 | 0.02974 | 0.17% |

| 0.8d/5 | 15.32767 | 0.0563 | 0.37% |

| Offset | Fundamental Amplitude (a.u.) | 3rd-Harmonic Amplitude (a.u.) | 3rd-Harmonic Component |

|---|---|---|---|

| d/6 | 55.13338 | 0.00083 | 0.00% |

| 1.02d/6 | 54.79716 | 0.02690 | 0.05% |

| 1.05d/6 | 54.28136 | 0.0668 | 0.12% |

| 1.1d/6 | 53.39073 | 0.13269 | 0.25% |

| 1.2d/6 | 51.50411 | 0.26232 | 0.51% |

| 0.98d/6 | 55.46262 | 0.02663 | 0.05% |

| 0.95d/6 | 55.94669 | 0.06653 | 0.12% |

| 0.9d/3 | 56.72395 | 0.13243 | 0.23% |

| 0.8d/3 | 58.15773 | 0.09575 | 0.16% |

| Offset | Fundamental Amplitude (a.u.) | 5th-Harmonic Amplitude (a.u.) | 5th-Harmonic Component |

|---|---|---|---|

| d/10 | 60.54953 | 0.00125 | 0.00% |

| 1.02d/10 | 60.42469 | 0.00678 | 0.01% |

| 1.05d/10 | 60.23296 | 0.01568 | 0.03% |

| 1.1d/10 | 59.90153 | 0.03049 | 0.05% |

| 1.2d/10 | 59.19442 | 0.05947 | 0.10% |

| 0.98d/10 | 60.67197 | 0.00534 | 0.01% |

| 0.95d/10 | 60.85115 | 0.01424 | 0.02% |

| 0.9d/10 | 61.13776 | 0.02906 | 0.05% |

| 0.8d/10 | 61.66566 | 0.05812 | 0.09% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lv, B.; Li, S.; Liu, J. Harmonic Suppression Method for Optical Encoder Based on Photosensitive Unit Parameter Optimization. Optics 2025, 6, 62. https://doi.org/10.3390/opt6040062

Lv B, Li S, Liu J. Harmonic Suppression Method for Optical Encoder Based on Photosensitive Unit Parameter Optimization. Optics. 2025; 6(4):62. https://doi.org/10.3390/opt6040062

Chicago/Turabian StyleLv, Bowei, Shitao Li, and Jie Liu. 2025. "Harmonic Suppression Method for Optical Encoder Based on Photosensitive Unit Parameter Optimization" Optics 6, no. 4: 62. https://doi.org/10.3390/opt6040062

APA StyleLv, B., Li, S., & Liu, J. (2025). Harmonic Suppression Method for Optical Encoder Based on Photosensitive Unit Parameter Optimization. Optics, 6(4), 62. https://doi.org/10.3390/opt6040062