Abstract

Deep learning has enabled significant progress in source code generation, aiming to reduce the manual, error-prone, and time-consuming aspects of software development. While many existing models rely on recurrent neural networks (RNNs) with sequence-to-sequence architectures, these approaches struggle with the long and complex token sequences typical in source code. To address this, we propose a grammar-based convolutional neural network (CNN) combined with a tree-based representation to enhance accuracy and efficiency. Our model achieves state-of-the-art results on the benchmark HEARTHSTONE dataset, with a BLEU score of 81.4 and an Acc+ of 62.1%. We further evaluate the model on our proposed dataset, AST2CVCode, designed for computer vision applications, achieving 86.2 BLEU and 51.9% EM. Additionally, we introduce BLEU+, an enhanced evaluation metric tailored for functional correctness in code generation, which achieves a BLEU+ score of 92.0% on the AST2CVCode dataset. These results demonstrate the effectiveness of our approach in both model architecture and evaluation methodology.

1. Introduction

The task of source code generation involves creating executable code from multimodal inputs such as natural language descriptions or partial code snippets. This approach automates programming tasks, enhancing productivity and flexibility compared to traditional methods, which often struggle to capture complex dependencies in code structures. Recent developments in deep learning (DL) and natural language processing (NLP) have advanced these methods, enabling models to convert software requirements, particularly described in natural language, into accurate source code. These DL-based models significantly streamline the software development process, reducing both effort and time required.

Computer vision, a key AI domain, enables machines to interpret visual data, granting them the capability of sight. This technology has various applications, including autonomous driving, traffic analysis, medical imaging, defect detection, crop management, and intelligent surveillance. Given their critical nature, these applications demand high reliability and substantial development efforts. Leveraging advanced automated code generation techniques can significantly simplify the development of these complex systems.

Generating source code from natural language descriptions is challenging because of the structural differences between input descriptions and the required output code. The primary methods for this task are sequential and tree-based approaches [1]. Sequential models use sequence-to-sequence techniques to convert descriptions into code sequences but do not always guarantee structural correctness. Tree-based methods represent code through an Abstract Syntax Tree (AST), ensuring code accuracy by enforcing structural constraints. However, tree-based approaches can struggle with generating precise code for infrequent or complex phrases due to discrepancies in node counts between ASTs and natural language inputs.

Source code generation for computer vision systems is challenging, especially since accuracy, efficiency, and reliability are important metrics. Unlike other domains, computer vision tasks typically include high-dimensional data that needs complex data preprocessing and powerful model architectures. The source code for these systems must perform significant computational loads and feature extraction techniques, which are complex to generate correctly. Computer vision tasks require specialized architectures, such as CNNs or transformer-based models. These architectures need to set specific layers, parameters, and hyperparameters. These architectures must understand these structures and tune them correctly to meet the requirements of a given task and generate accurate source code.

Source code generation can significantly enhance computer vision applications by simplifying development, improving performance, and reducing human error. Preprocessing and data augmentation are critical in computer vision to provide powerful model performance. By generating code that performs tasks such as image resizing, normalization, and different augmentations, code generation tools can save developers time and guarantee consistency. Source code generation tools provide optimized, low-latency code that utilizes available hardware acceleration, such as CUDA for GPUs, to minimize inference times and make real-time computer vision applications feasible on edge devices. Manually implementing complex models is error-prone, but source code generation tools minimize errors that can affect model performance, reliability, or even safety in critical applications. In practice, these capabilities of source code generation produce faster development cycles, more reliable computer vision solutions, and improved model performance.

This study is guided by a set of research questions aimed at advancing the field of source code generation through deep learning techniques, with a specific application to computer vision systems. The primary research question is: Can a deep learning-based model effectively generate functionally correct and domain-relevant source code for computer vision tasks from abstract representations such as ASTs or natural language descriptions? To support this, we further investigate: (1) How can the limitations of traditional sequence-based models, such as RNNs, be addressed to improve the accuracy and scalability of code generation? and (2) What architectural enhancements, such as grammar-aware CNNs or tree-based encodings, can be introduced to better capture the structural and semantic complexity of source code? Finally, we ask: (3) Can a domain-specific evaluation metric, such as BLEU+, provide a more functionally meaningful assessment of generated code compared to conventional text similarity metrics? These research questions frame the development, application, and evaluation of our proposed model and metric.

In summary, this paper makes the following contributions: we propose that computer vision systems be enhanced by adopting a deep learning approach for source code generation to reduce the development time of these systems and enhance programming productivity. Motivated by this, we built a new specific dataset called AST2CVCode for computer vision applications; we then applied and evaluated the proposed model on this dataset. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first work that addresses the source code generation of computer vision systems. Moreover, we introduce an improved approach to enhance the computational framework of the BLEU metric, termed BLEU+. This refined method demonstrates its effectiveness in evaluating the functional correctness of generated source code.

This paper is structured as follows. Section 2 reviews and discusses the main works on deep learning-based source code generation models. Section 3 presents the proposed model architecture and its detailed design. The experimental results of the proposed model are shown in Section 4. Finally, the conclusions are outlined in Section 5.

2. Related Works

In the literature, different deep learning-based models are proposed to solve source code generation tasks. In [2], the authors introduce a neural network architecture named Latent Prediction Network. It is based on RNN and allows efficient marginalization over multiple predictors. Under this architecture, they propose a generative model for code generation that combines a character-level softmax to generate language-specific tokens and multiple pointer networks to copy keywords from the input. A novel neural network model driven by a grammar model was proposed in [3], where a data-driven model to generate a source code of a general-purpose programming language (PL) was designed. They used a tree-based approach to convert a natural language statement to an AST for the target PL. Deterministic generation tools were used to convert the AST into source code. They used neural encoder–decoder models with the syntax trees for source code generation tasks. A bidirectional Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) network was used as an encoder. At the same time, RNN is used to perform the sequential generation process of an AST. In [4], the authors introduce the Abstract Syntax Network (ASN), which extends the standard encoder–decoder model by composing submodels of the decoder to generate ASTs; each model is connected with a specific construct in the AST grammar and invoked when that construct is required in the output tree. Each input element was encoded using a bidirectional LSTM; the decoder used a vertical LSTM.

RECODE [5] is a subtree retrieval approach using an AST-based neural network model to generate general-purpose source code. This approach uses a neural network model, which consists of a bidirectional LSTM encoder and an LSTM decoder. TRANX [6], a TRANsition-based abstract syntaX parser, is used for semantic parsing and source code generation. TRANX converts natural language into formal meaning representations (MRs) based on the abstract syntax description language. It uses an RNN neural encoder–decoder network since it has recurrent connections that reflect the AST structure. Both the encoder and decoder use a standard bidirectional LSTM network.

In [7], the authors introduced a method that takes a training example using the input (e.g., natural language description) and then modifies it to produce the required output (e.g., code). A grammar-based CNN model for source code generation was presented in [8]. This model predicts the grammar rules of the programming language to generate a specific program. In [9], the authors developed a model based on AST to analyze source code. This model was implemented to generate and complete the source code; it helps software developers and programmers improve code efficiency and accelerate the process of development. This model was built using LSTM and Multiple Layer Perceptron (MLP) architectures.

A solution for code generation is proposed in [10], and it is based on the Encoder–Decoder deep learning model. This model takes the natural language form as input and generates the object code. It is based on a sequence-to-sequence approach. The encoder and the decoder are LSTMs.

CodeBERT [11] is a model trained on programming languages and natural language to support several software development tasks such as code search, code summarization, and code completion. It was built using the BERT model and trained on a dataset from GitHub repositories.

In [12], Codex was introduced; it is a fine-tuned version of GPT-3 [13], which is a transformer-based language model developed by OpenAI. It is designed to perform tasks related to programming, such as code generation, translation, and completion. It is the foundation of tools like GitHub Copilot.

In [14], a generic transformer-based seq2seq model is used based on Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers (BERT) as the encoder and a four-layer transformer decoder. A unified pre-trained encoder–decoder transformer model is presented [15], which incorporates the token type information from code.

Tree-based methods generate new AST nodes based on prior predictions of AST nodes. However, current approaches often consider both prior and subsequent predictions equally, which can be difficult for models to provide reliable subsequent predictions if the prior predictions are incorrect within the AST constraints. To address this issue, it is crucial to focus more on antecedent predictions than subsequent predictions. Consequently, a new and effective approach, called Antecedent Prioritized (AP) Loss, was proposed [16], which prioritizes earlier predictions by utilizing the position information of the generated AST nodes—it is based on LSTM.

In [17], a Seq2Seq-based framework called CODEP was introduced, which first incorporates the deduction of pushdown automaton (PDA) into deep learning for source code generation. This framework uses the PDA deduction state to help transformer-based encoder–decoder models learn the deduction process. The PDA module ensures the grammatical accuracy of the generated code. An encoder–decoder transformer model was developed in [18], where both the encoder and decoder were specifically trained to identify the syntax and dataflow in the source and target codes, respectively. The encoder is structure-aware by using the source code’s syntax tree and dataflow graph, while the decoder is aided in maintaining the target code’s syntax and dataflow through two new auxiliary tasks: AST path prediction and dataflow prediction.

The Relevance Transformer was proposed in [19]; it is a retrieval-augmented code generation model. It retrieves relevant code examples based on the input description and incorporates this context into a Transformer-based architecture to guide code generation.

AlphaCode [20] is a transformative code-generation system created by DeepMind and introduced in early 2022. Leveraging large, encoder–decoder transformer models trained on extensive competitive programming datasets (e.g., Codeforces), it generates millions of candidate programs via sampling, then filters these by execution-based validation and clustering to identify high-quality solutions. In evaluations across real Codeforces contests, AlphaCode achieved a median ranking within the top ~54% of participants—an unprecedented performance for machine-generated code, demonstrating capabilities in algorithmic reasoning and problem understanding beyond simple syntax generation. Despite some inefficiencies—such as nested loops and excess variable declarations—the generated solutions often mirror human-like coding approaches.

PolyCoder [21] and InCoder [22] approach code generation from orthogonal standpoints. PolyCoder, an open-source GPT-2–style model from Carnegie Mellon University, is trained on 249 GB of permissively licensed code across 12 languages on a single machine, totaling around 2.7 billion parameters. It notably outperforms comparably sized models (e.g., GPT-Neo, Codex) in C-language benchmarks, thanks to its multilingual diversity and open availability. InCoder, introduced in April 2022, adds bidirectional context by employing a causal-masked infilling mechanism: the model can perform left-to-right synthesis and infill arbitrary missing regions, improving performance in editing tasks such as type inference, commenting, and variable renaming in zero-shot scenarios. InCoder maintains comparable synthesis performance to traditional autoregressive models while bringing the flexibility of context-aware code editing.

A comparative analysis of the deep learning models for source code generation is illustrated in Table 1.

Table 1.

Comparative analysis of the deep learning models for source code generation.

Based on Table 1, it can be observed that the models [2,7] are based on RNN. The models [3,4,5,6,10,16] use LSTM as encoder and decoder, while the model [8] uses CNN encoder–decoder. LSTM and MLP are used as encoders in [9]. Transformer and BERT are used in [11,12,14,15,17,18]. The neural network (NN) that is used in the model affects the performance since some types of NN are more suitable for NLP tasks than others. It is observed that a program is longer than a natural language sentence, and the RNN model has a long dependency problem even with LSTM. Conversely, CNN models use sliding windows to effectively capture features in different regions.

Moreover, the models [2,7,10,11,12,14,15,17] use a sequence-to-sequence approach, while [3,4,5,6,8,9,16,18] use a tree-based approach, which proves the effectiveness in improving accuracy.

Most of the models use exact matching accuracy (EM) as a measurement, which is the fraction of correctly generated examples. However, it is a nontrivial task to generate an exact match for complex code structures. Therefore, token-level BLEU is used as another metric; it is the average BLEU score over all examples. Some models use the CodeBLEU score [23], which considers important grammar and semantic features of codes.

Based on the comparison mentioned above, we propose to use CNN because it achieves higher values of exact match accuracy (EM) and BLEU results than other models on the HEARTHSTONE dataset. Also, the proposed model uses a tree-based approach since it is effective and improves accuracy. CNN can achieve higher EM for source code generation tasks compared to other models since CNN captures local patterns and features, and it builds hierarchical representations of input data to understand complex code structures and dependencies. CNNs can benefit from specialized preprocessing and embeddings for source code, such as token embeddings or ASTs. These embeddings can help the CNNs understand the structure and semantics of the code better.

In this study, CNNs were chosen for source code generation due to their ability to efficiently capture local and hierarchical patterns in code. Source code, while sequential in structure, often exhibits strong local regularities such as recurring syntax patterns, control structures, and idiomatic usage, which CNNs are well-suited to model through their localized receptive fields. Unlike RNNs, which process input tokens sequentially and are often hindered by vanishing gradients, CNNs allow for parallel processing and are more computationally efficient, particularly on longer code sequences. Furthermore, CNNs’ architectural simplicity and capacity to learn spatially invariant features make them attractive for modeling source code, where important patterns may occur in varying contexts or locations within a snippet. While RNNs (and their variants like LSTMs) have traditionally been applied to code generation tasks, recent work shows that CNNs can achieve comparable or superior performance. These considerations support the use of CNNs as a viable and efficient alternative to RNNs in the domain of source code generation.

CNNs are often used with image processing but are increasingly applied to sequential and structured data. In [24], the authors introduced a two-stage deep learning framework that combines CNNs and RNNs for recognizing and predicting fine-grained human activities in manufacturing assembly tasks. The study employed transfer learning by utilizing pre-trained CNN models to extract scene-level features from RGB images and hand skeleton frames. Recent work [25] explored the use of CNN and transformer-based architectures for structured data modeling in human-centered computing applications, particularly in terms of activity recognition and sensory signal processing tasks. Their approach demonstrated how deep learning models can effectively handle structured, temporal, and multi-modal input, supporting the broader applicability of such architectures beyond conventional vision tasks.

In this paper, we propose a CNN-based approach for source code generation, a unique approach that can provide efficient local feature extraction and optimize computational complexity for source code generation tasks. For specific types of source code generation, CNNs can provide faster training and inference times compared to transformers and RNNs.

Since our proposed CNN-based approach is designed for computer vision applications, this represents a unique and specific field. CNNs are already foundational in computer vision; thus, exploiting their strengths to generate source code specifically for vision-related tasks (e.g., object detection, image classification) is a natural extension. This aligns our proposed model as a connection between source code generation and domain-specific requirements in computer vision, which few existing models directly address.

3. The Proposed Model Architecture

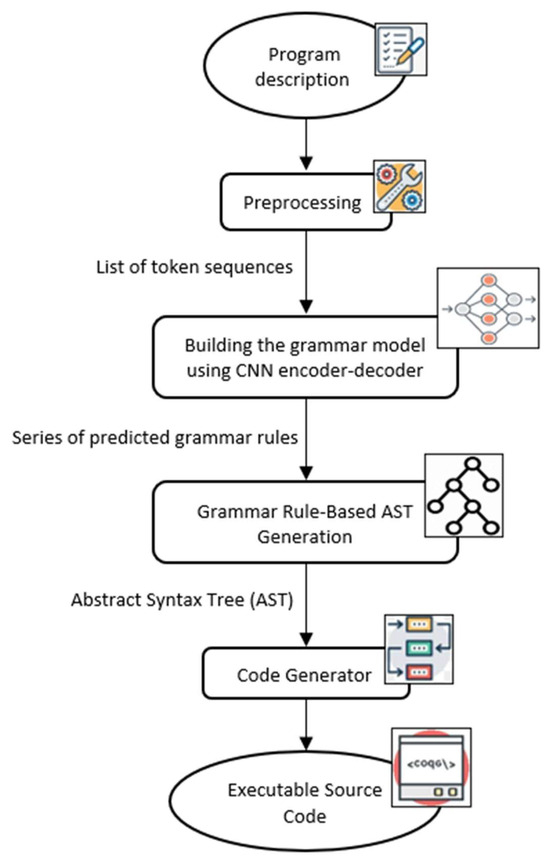

In this section, we present the proposed model architecture and its detailed design. It has four phases as shown in Figure 1: (i) preprocessing, (ii) building the grammar model using CNN encoder–decoder, (iii) grammar rule-based AST generation, and (iv) generating the source code using the back-end module of the code generator.

Figure 1.

The proposed model architecture.

The whole process consists of the following key phases:

- Preprocessing Phase: The input description is first passed through a preprocessing module that performs necessary tokenization and normalization steps to produce a list of token sequences.

- Building the grammar model using CNN Encoder–Decoder Phase (Grammar Rule Prediction): This token sequence, along with three additional inputs—(i) previously predicted grammar rules, (ii) the partially generated AST, and (iii) the list of relevant functions—is fed into the CNN-based encoder–decoder model. This phase predicts the next appropriate grammar rule at each step. The output from the second phase is a series of predicted grammar rules.

- Grammar Rule-Based AST Generation: The predicted grammar rules are parsed in a structured manner to incrementally construct the Abstract Syntax Tree (AST). Each rule contributes to expanding the AST based on its semantic definition.

- Code Generation Phase: Finally, the complete AST is passed to a language-specific back-end module that converts it into syntactically correct and executable source code.

3.1. Preprocessing

The proposed model takes the program description as input, such as “sort my list in descending order”. In the preprocessing phase, for the input description, we remove all punctuation and replace it with a space. All letters are changed to lowercase. Also, we remove redundant spaces and other meaningless characters. After cleaning, we tokenize and organize the dataset into sequences of fixed length. The following pseudocode (Algorithm 1) outlines the preprocessing steps applied to the input program descriptions.

| Algorithm 1 Preprocessing for program descriptions |

| Input: Description as a string, Sequence length Output: List of token sequences 1: Remove all punctuation from the description 2: Convert all letters to lowercase 3: Remove redundant spaces and meaningless characters 4: Tokenize the cleaned description into words 5: for each token from index i = 0 to length(tokens) − sequence_length + 1 do 6: Extract the sequence of tokens from index i to i + sequence_length 7: Append the sequence to the list of sequences |

3.2. Building the Grammar Model Using CNN Encoder–Decoder

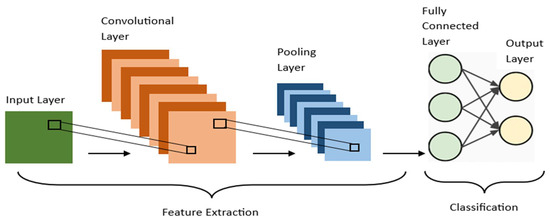

CNN is a neural network architecture in deep learning, which is used to recognize patterns from structured arrays. However, over the years, many variants of the fundamental CNN architecture have been developed, such as LeNet-5, AlexNet, ResNet, and DenseNet. CNN is a special type of feed-forward artificial neural network in which the connectivity pattern between its neurons is inspired by the visual cortex. It is very useful as it minimizes human effort by automatically detecting the features. It has high accuracy and leads to significant advances in the deep learning field. CNN applications range from image and video recognition, image classification, medical image analysis, computer vision, and natural language processing. In general, CNN has two main parts: feature extraction and classification, as seen in Figure 2. The feature extraction part has three layers: the input layer, the convolutional layer, and the pooling layer. The classification part has two layers: a fully connected layer and an output layer.

Figure 2.

Basic CNN Architecture.

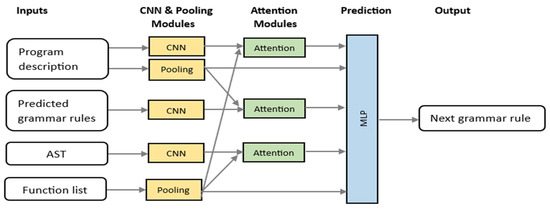

In the CNN encoder–decoder model, the encoder takes the program description input consisting of tokens and encodes them into vectorial representations. The decoder uses a CNN to model the sequential generation process of an AST. There are various grammar rules, and the CNN predicts the appropriate rule to apply at each time step. The series of predicted grammar rules constructs a complete program. These distinct grammar rules are used to generate an AST. In the proposed model, we adopt shortcut connections (i.e., DenseNets [26]) that suggest skipping some of the layers in the neural network and feeding the output of one layer as the input to the next layer. It was introduced to solve different problems in different architectures and enhance performance. Figure 3 shows the overall structure of the proposed model.

Figure 3.

Overview of the CNN encoder–decoder model.

In this model, there are four basic input types to predict the grammar rule: the natural language that describes the program to be generated, the previously predicted grammar rules, the generated AST, and the function list. In our proposed model, although we employ a CNN, which is not inherently designed for sequence modeling, we structure the input in a way that allows the network to effectively capture sequential and contextual dependencies.

The model receives four primary inputs: (1) the natural language description of the program to be generated, (2) the sequence of previously predicted grammar rules, (3) the partially constructed AST, and (4) a list of available functions. These inputs are encoded in a structured format that preserves their order and semantic relationships. For instance, the sequence of grammar rules represents a temporal progression of the derivation process, while the AST and functions list embed hierarchical and contextual information. By applying convolutional filters over these structured representations, the CNN learns local and hierarchical patterns that reflect both syntactic structure and sequential dependencies. This design enables the model to effectively consider the order of input elements and make informed predictions based on the evolving context during the grammar rule generation process. In the rest of this section, we describe each module in detail for these types of inputs.

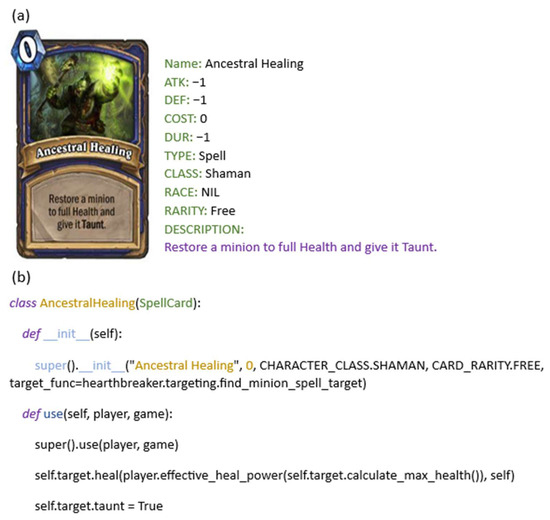

3.2.1. CNN and Pooling for Program Description

The first input of the model represents the program description; it provides important details about the program to be generated. In the context of the HEARTHSTONE dataset, this description includes semi-structured data that contains key attributes such as the card’s name, properties, and descriptive text, as shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Example card of HEARTHSTONE. (a) Input description: (b) Output program.

Initially, the program description was tokenized, converting the textual and structured input data into a sequence of tokens. These tokens were then transformed into embeddings—numerical representations that capture the semantic information of each token. The embeddings serve as inputs to subsequent layers.

To capture complex patterns in the program description, we applied convolutional and pooling layers. CNNs are effective for extracting high-level features from data sequences, allowing the model to capture relationships between tokens and to recognize important patterns in the description. Pooling layers follow each convolutional layer to downsample the output, reducing dimensionality and computational load while maintaining important features. Pooling is useful in preventing overfitting by focusing on larger patterns rather than specific details.

To improve the model’s training efficiency, we incorporated shortcut connections in every other layer. This approach is based on the DenseNet architecture, where layers are connected to facilitate the effective flow of gradients, especially in deep networks. In our implementation, we added shortcut connections parallel to a linear transformation applied before the activation function. This configuration helps prevent the vanishing gradient problem, making it easier to train deep neural networks by promoting feature reuse across layers.

3.2.2. CNN for Predicted Grammar Rules

To generate a program accurately, the model needs to consider the structure and syntax rules, which are typically defined by a formal grammar. In this model, the probability of generating the next grammar rule number is computed by considering previously predicted grammar rules.

Each previously predicted grammar rule is treated as a sequential input that captures part of the program’s structure up to the current point. These rules can include fundamental programming constructs or domain-specific rules. As the program generation advances, a growing sequence of these rules helps in guiding the model by incorporating structural dependencies across the program.

To extract significant features from this sequence of grammar rules, a deep CNN module is applied. CNNs are used to recognize patterns and hierarchies in structured sequences. The deep CNN captures local patterns between adjacent rules as well as higher-level dependencies that are critical to getting accurate predictions of the next grammar rule number in the program. CNN can learn to identify recurring patterns or sequences of rules that often occur together in valid programs. For example, if certain rules typically follow one another in the HEARTHSTONE card descriptions, CNN can capture this pattern, helping the model to understand both the syntax and typical structure of a valid program.

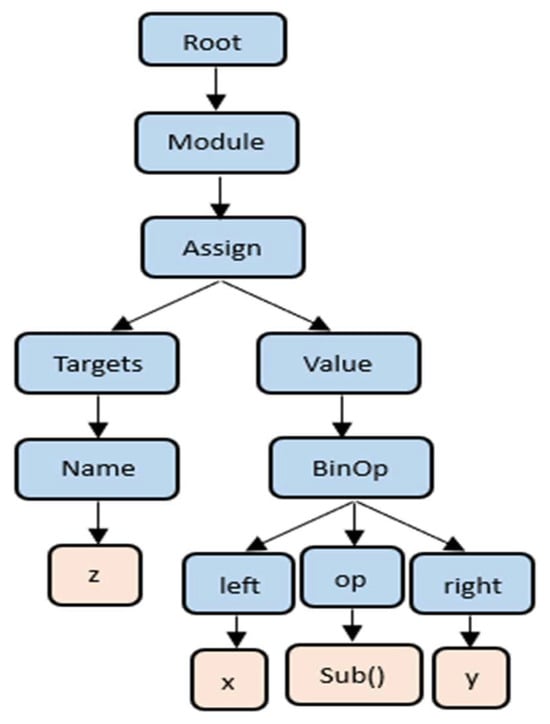

3.2.3. CNN for AST

In programming, the AST is a structured, tree-like representation that captures the syntactic structure of a program. Each node in the AST represents a language construct and indicates the hierarchical relationships within the program. The AST is a powerful representation of a program because it maintains both the order and structure of the components, allowing models to process the program at a high level of abstraction.

As illustrated in Figure 5, the AST organizes the components of a program based on its syntax and structural relationships. To efficiently process this tree structure, a depth-first pre-order traversal is applied to obtain the tree path. This tree path serves as an input to a deep CNN module to capture essential structural information of the AST. Moreover, convolutional layers in the CNN can capture both local and long-range dependencies and gain a comprehensive understanding of the AST’s hierarchical structure.

Figure 5.

The abstract syntax tree (AST) of code: z = x − y.

3.2.4. Pooling for Function List

In many programming tasks, functions are essential components to encapsulate specific operations, logic, or effects within a program. To effectively generate a program, the model requires capturing significant information about each function in the program.

To process the list of functions, we begin by creating function embeddings. Each function is represented by an embedding, a numerical vector that captures its semantic meaning and attributes (e.g., its name, parameters, or functionality).

We apply a pooling layer to the function embeddings. The pooling layer acts as a feature summarizer, reducing the dimensionality of the function list while maintaining the most critical information. To further enhance feature extraction, we apply shortcut connections parallel to the pooling layer. Shortcut connections allow the original embeddings to flow directly to later layers without modification, effectively combining the summarized features from the pooling layer with the original, detailed embeddings. Pooling with shortcut connections allows the model to efficiently capture the core patterns in the function list.

3.2.5. Attention Modules

After applying CNN and pooling layers to extract features from different components of the input (such as the program description, predicted grammar rules, or AST structure), the model obtains a set of feature representations. However, these extracted features vary in size and importance, and before making predictions, they need to be combined into fixed-size vectors that summarize the most relevant information. Fixed-size vectors are essential for using a softmax layer, which is required to make probabilistic predictions.

To effectively combine these features, we incorporate attention layers following the CNN and pooling layers. Attention mechanisms play a critical role in helping the model focus on the most informative features within the feature set. Attention layers allow the model to clarify which features contribute most to the predictions, making it easier to understand the model’s decision-making process. Attention reduces the dimensionality and complexity of the feature set, simplifying the data the model uses for final predictions and helping avoid overfitting to specific features. While attention does not reduce dimensionality in the conventional sense, such as through feature projection or selection, it facilitates effective complexity management by assigning higher weights to salient features and diminishing the influence of less relevant features. This selective weighting leads to a functional simplification of the input space, allowing the model to concentrate its capacity on the most impactful information. In our model, the attention module is designed to operate alongside the core feature extractor, guiding the learning process without discarding dimensions outright. Although this introduces additional parameters, it improves the overall performance by enhancing the model’s representational power and learning efficiency.

With the attention-compressed fixed-size vector, the model can effectively apply a softmax layer for prediction. The softmax function calculates probabilities for each possible output, allowing the model to make clear and confident predictions.

While CNNs are well-suited for capturing local and hierarchical patterns, we acknowledge that certain programming constructs, such as variable references, control flows, and nested scopes, require broader contextual awareness. To address this, our proposed model incorporates attention mechanisms alongside convolutional layers. The inclusion of attention allows the model to dynamically focus on relevant parts of the input sequence, thereby enhancing its ability to capture long-range dependencies effectively. Empirical results demonstrate that the integration of attention significantly improves performance, particularly in cases where understanding global context is crucial. This design choice enables our model to bridge the gap between local pattern recognition and global structural comprehension in source code generation.

3.2.6. MLP for Prediction

After extracting features from various inputs (program description, AST, grammar rules) using CNN, pooling, and attention layers, the model combines all this information into a set of fixed-size feature vectors. These feature vectors contain distilled representations of the program’s structural, syntactic, and semantic aspects, all of which are significant for predicting the next step in generating the program.

To make the final prediction, we use a Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP), a type of fully connected neural network. The MLP takes all the pooled and attended feature vectors as inputs and processes them to predict the next grammar rule in the sequence.

An MLP is effective for combining various types of features. With its multiple layers and non-linear activation functions, the MLP can model complex relationships between the features extracted from previous layers. This is essential for grammar rule prediction, as there are often intricate dependencies between different parts of the program.

The MLP’s fully connected structure combines information across all the dimensions of each feature vector. This representation is significant for generating syntactically and semantically correct grammar rules.

The final layer of the MLP uses a softmax activation function to produce a probability distribution over all possible grammar rules. The MLP’s capacity to learn complex, non-linear interactions means that it can adapt to diverse patterns in the data, making it robust to variations and helping to generalize to new program structures. Since softmax outputs a probability distribution, the model can choose the most likely next grammar rule, ensuring the generated program follows the correct syntax and logical sequence.

3.3. Grammar Rule-Based AST Generation

ASTs can be generated for all well-formed programs using a structured approach to parse the series of predicted grammar rules and progressively build the AST based on each rule’s semantics. In order to generate the AST, we map each grammar rule in the grammar rules sequence to a specific AST node. The structure and semantics of the AST depend on the series of predicted grammar rules.

3.4. Code Generator

ASTs can be converted to source code using a standard back-end module provided by the PL. The back-end module is a programming language-dependent module, such as the astor library, which is used to convert ASTs into Python code. There is a back-end module for each programming language. It takes the high-level intermediate representation of the code (ASTs) as input and generates the source code of the programming language, such as Python, C++, and Java. The high-level intermediate representation of the code can be converted to any programming language since they are written in pseudo-code. The keywords, operators and structure for each programming language are understood by the back-end module.

In summary, the proposed model utilizes four core inputs: (1) the natural language description of the program to be generated, (2) the previously predicted grammar rules, (3) the partially generated AST, and (4) the list of relevant functions associated with the target task. The process is organized into four distinct phases. In the Preprocessing Phase, the input description—such as “add x and y”—is passed through a preprocessing module that performs tokenization and normalization, resulting in a list of token sequences. In the Grammar Rule Prediction Phase, this token sequence, along with the previously predicted grammar rules (e.g., [0, 1]), the partially generated AST structure (e.g., [‘body_root’, ‘Module_root’, ‘root_root’]), and the relevant function list (e.g., Add_func), are provided as inputs to a CNN-based encoder–decoder model. The encoder extracts deep representations from these inputs, while the decoder predicts the next grammar rule (e.g., 178) in the sequence. The output from this phase is a complete series of predicted grammar rules that define the program’s structure. In the AST Generation Phase, the predicted grammar rules are parsed and structured incrementally to form the Abstract Syntax Tree, with each rule expanding the tree according to its semantics. Finally, in the Code Generation Phase, the fully constructed AST is passed to a language-specific code generator, producing the final executable source code—for example, z = x + y.

4. Experimental Evaluation

In this section, we introduce the experimental results of the proposed model for source code generation.

4.1. Datasets

We conducted the experiments on two datasets:

- HEARTHSTONE [2]:

This is a public benchmark dataset. It is designed for the automatic generation of code for game cards. Figure 4 illustrates that each sample consists of a semi-structured description along with a human-written program. The description includes several attributes like the card’s name and type, as well as a natural language description of the card’s effect.

- AST2CVCode [27]:

We created and prepared a domain-specific benchmark dataset. It is for source code generation to assist the development of computer vision applications, since the source code used in the computer vision domain differs from other domains. It has 65 Python code snippets for classification and recognition tasks.

In order to build AST2CVCode, we used three steps: (1) We collected Python code snippets and added an appropriate description to each code snippet. (2) Each code snippet was converted to its AST structure. (3) Based on the generated AST, we constructed the dataset, which contains five main lines. The first line represents the program description. The second line includes the depth-first pre-order tree path of the AST. The third line contains the predicted grammar rules list since each AST node is mapped to its corresponding grammar rule number. The fourth line indicates the next grammar rule number that will be used. The last line contains the functions that are used. These five lines are repeated for every node in the AST. (4) Steps (2) and (3) are repeated for each code snippet collected in step (1) to build the final dataset file.

The AST2CVCode dataset has specific characteristics, including: (1) High-quality text descriptions with specific keywords significant for programming purposes. (2) Diversity in language expressions and style.

High-quality and diverse datasets provide several benefits to real-world applications in computer vision since they produce models that generalize efficiently and perform complex tasks accurately under various conditions.

4.2. Metrics

To evaluate the effectiveness of our proposed model, we employed three widely used evaluation metrics. Moreover, we proposed an enhanced methodology to improve the computational framework of the BLEU metric, referred to as BLEU+.

- Exact match (EM):

It is the exact matching accuracy between the generated code and the reference code. EM is determined using the following expression:

where N is the total number of code samples, is the reference code for sample i, is the generated code prediction, and 1(·) is the indicator function, equals 1 if the condition is true, 0 otherwise.

However, because generating an exact match for complex code structures is nontrivial, we use the token-level BLEU score as a secondary metric. However, generating an exact match for complex code structures is challenging, and EM may be too strict to accurately reflect method performance. Therefore, we use token-level BLEU and CodeBLEU scores as secondary metrics.

We observed that some generated programs implement the correct functionality but use different variable names, and occasionally, an argument name in a function call may or may not be specified. Despite these differences from the reference program, they are obviously correct programs after manual inspection. This human-adjusted accuracy is denoted by Acc+.

- Acc+ (Human-Adjusted Accuracy):

Acc+ is a metric used to evaluate the accuracy of machine-generated programs by considering functional correctness with tolerance for non-essential differences. A program is marked as correct under Acc+ if it successfully implements the intended functionality, even if it deviates from the reference solution in ways that do not affect the outcome, such as:

- Using different variable names.

- Omitting or including argument names in function calls.

- Minor stylistic variations that preserve functionality.

In contrast to exact-match accuracy, Acc+ reflects a human evaluator’s perspective by acknowledging semantically correct but syntactically different solutions as correct.

- BLEU-4:

It is used to determine the token-level similarity between the generated code and the reference code. More precisely, it computes the -gram similarity, which can be expressed as:

where BP refers to the brevity penalty, which is applied to discourage overly short generated code. is set to 4 in our experiments. represents the -gram matching precision scores.

- CodeBLEU:

It considers syntactic and semantic matches based on the code structure in addition to the n-gram match. To calculate CodeBLEU, the following formula is applied:

are the weighting coefficients. These components are calculated independently and then linearly combined to produce the final CodeBLEU score.

- BLEU+:

BLEU+ is specifically designed to evaluate the functional correctness of generated source code. This metric offers an effective means of assessing the performance of models used in source code generation. Empirical results demonstrate that BLEU+ provides a reliable and efficient measure of functional correctness in this domain. BLEU+ is calculated using the following pseudocode (Algorithm 2):

| Algorithm 2 BLEU+ Calculation |

| Input: generated code (str), reference code (str) Output: BLEU+ score (float) 1: Normalize(code): 2: Extract variables, constants, and argument values using Regular Expression. 3: Replace variables and constants with generic placeholders. 4: Exclude language-specific keywords and built-ins from replacement. 5: return normalized code. 6: Calculate BLEU+ score between a reference code and a generated code: 7: normalizedRef ← Normalize(reference code) 8: normalizedGen ← Normalize(generated code) 9: Tokenize normalizedRef and normalizedGen 10: Apply smoothing method to ensure BLEU score does not become zero with short sequences. 11: Calculate BLEU+ score 12: return BLEU+ score |

To address the limitations of traditional text-based metrics in evaluating code generation tasks, we introduce BLEU+, a modified evaluation metric specifically designed to assess the functional correctness of generated source code. Unlike the standard BLEU metric, which focuses solely on n-gram overlap and may overlook semantic or structural correctness, BLEU+ incorporates code-aware modifications that emphasize the preservation of functional elements, such as correct API usage, control flow constructs, and syntactic validity. This makes it better suited for capturing the practical utility of generated code in real-world scenarios. To validate the effectiveness of BLEU+, we apply it to a domain-specific dataset comprising source code derived from computer vision tasks (AST2CVCode), where the correctness of algorithmic implementation is critical. Through comparative analysis, we demonstrate that BLEU+ provides a more accurate reflection of functional fidelity than standard BLEU, particularly in cases where small lexical variations lead to significant semantic differences. This enhanced sensitivity to functional correctness supports BLEU+ as a more reliable evaluation criterion for source code generation.

4.3. Baselines

To exhibit the effectiveness of our proposed method, we compared it with several proposed code generation models as baselines. They can be divided into two categories: sequence-based baselines and tree-based baselines.

The sequence-based baselines [2,7,11,15,19] treat the source code as plain text and directly generate a code token sequence:

The tree-based baselines [3,4,5,8] directly generate an AST of the source code. The generated AST is then transformed into source code.

We mainly compared our proposed method to the previous state-of-the-art models applied to the same dataset (HEARTHSTONE) to ensure the fairness of the comparison.

4.4. Results and Discussion

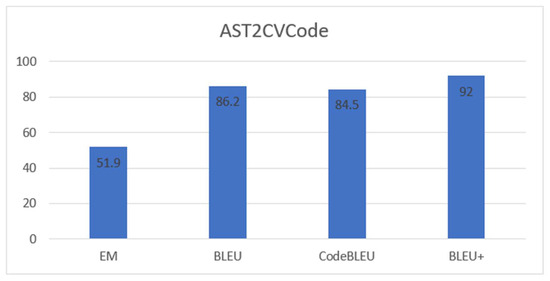

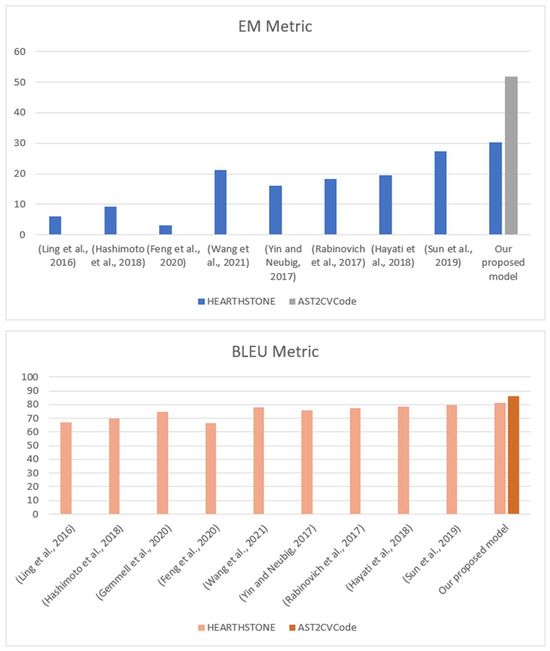

Table 2 shows the experimental results of our proposed model compared to previous state-of-the-art models. The results show that our proposed model outperforms previous models on the HEARTHSTONE dataset. We further apply and evaluate our proposed model on our computer vision dataset (AST2CVCode) as seen in Figure 6. Our proposed model achieves strong performance on the AST2CVCode dataset for source code generation, demonstrating the robustness of our model across multiple evaluation metrics. Specifically, the model attains an EM score of 51.9, indicating its high capability to generate code that exactly matches the reference implementation. Furthermore, it achieves a BLEU score of 86.2 and a CodeBLEU score of 84.5, reflecting both syntactic and semantic accuracy in the generated code. Notably, the model also obtains a BLEU+ score of 92.0. These results collectively suggest that the model is not only precise in replicating target code but also robust in preserving structural and functional correctness.

Table 2.

The performance of our proposed model in comparison with previous state-of-the-art results on the HEARTHSTONE dataset.

Figure 6.

The performance of our proposed model with the AST2CVCode dataset.

Our experiments show that BLEU+ more closely correlates with human judgments of functional accuracy compared to standard BLEU. Specifically, as illustrated in Figure 6, BLEU+ consistently assigns higher scores to functionally correct outputs that exhibit minor lexical differences, while penalizing structurally incorrect code even when surface-level overlap is high. This demonstrates that BLEU+ provides a more accurate and reliable measure of the semantic fidelity of generated code, making it a valuable evaluation criterion for source code generation systems.

Due to the complexity and challenging nature of the dataset used in our experiments, applying cross-validation (CV) or k-fold validation was not feasible in our current setup. The dataset’s size, structure, and the computational cost associated with training the proposed model made it impractical to perform such validation. Specifically, the HEARTHSTONE dataset presents significant complexity compared to conventional datasets. Each individual sample in HEARTHSTONE is composed of multiple interrelated lines of data that must be parsed, interpreted, and aligned to represent a single programmatic construct. Unlike simpler datasets where each sample is a single, self-contained line or instance, HEARTHSTONE requires a multi-step parsing process to extract structured information for each sample, including card attributes, rules, and corresponding code elements. This complexity makes data loading and splitting for cross-validation computationally intensive and impractical under current constraints.

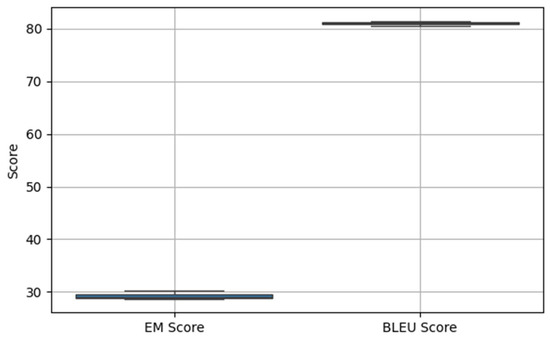

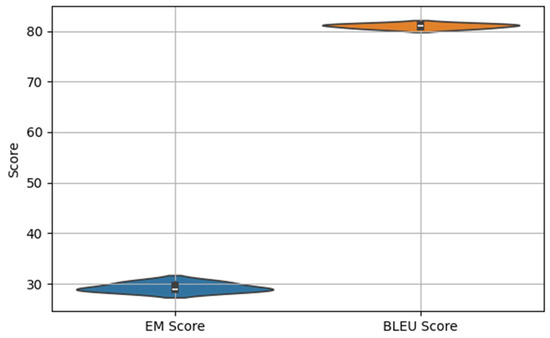

Instead of employing cross-validation, we conducted multiple independent runs of the experiment and reported the average performance across these runs to obtain a robust estimate of the model’s effectiveness. Specifically, we performed three independent runs using the same train-validation-test split but with different model initialization and training parameters. This strategy helps account for the variability introduced by stochastic training processes such as weight initialization and batch ordering. Based on this evaluation, the proposed model achieved an EM score of 29.3 and a BLEU score of 81 on the HEARTHSTONE dataset, demonstrating strong performance in terms of both strict syntactic correctness and overall generation quality. To further evaluate the robustness of our framework, we include a box plot (Figure 7) and a violin plot (Figure 8) to illustrate the distribution of EM and BLEU scores across three independent runs, capturing both the central tendency and variance.

Figure 7.

Performance Variability Across Three Independent Runs.

Figure 8.

Distribution of Performance Scores (Violin Plot).

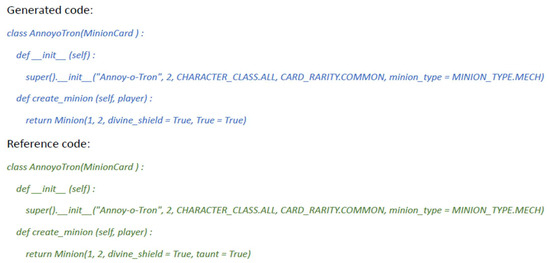

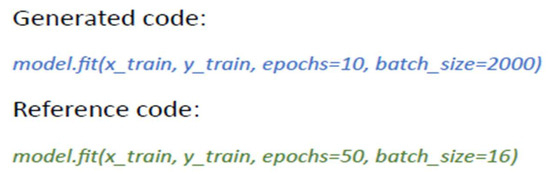

Figure 9 shows the EM and BLUE results of our proposed model compared to other state-of-the-art models. Moreover, Figure 10 and Figure 11 show examples of the generated code by our proposed model for the HEARTHSTONE dataset and AST2CVCode dataset, respectively. In comparison to the reference code, the generated code uses different variables but maintains the correct functionality.

Figure 9.

EM and BLUE results with the models.

Figure 10.

Example of the generated code for the HEARTHSTONE dataset.

Figure 11.

Example of the generated code for the AST2CVCode dataset.

An ablation study was conducted to assess the contribution of various architectural components to the performance of our source code generation model, with results summarized in Table 3. The full model achieved an EM score of 30.3, serving as the performance benchmark. Removing the CNN for predicted grammar rules led to the most significant performance drop (EM: 19.7), highlighting its critical role in capturing the syntactic structure necessary for generating valid code. The absence of the CNN for AST and the attention modules both resulted in a reduced EM of 22.7, indicating that structural representation and contextual focus are important for accurate code synthesis. Excluding pooling over the function list yielded a moderate decline in performance (EM: 25.8), suggesting its supportive role in understanding the functional context. Overall, this ablation study underscores the importance of each component, particularly grammar rule modeling, in enhancing the syntactic and semantic correctness of generated code.

Table 3.

Ablation test.

4.5. Statistical Analysis

To evaluate the effectiveness of our proposed model, two statistical tests were employed: the paired t-test and the Wilcoxon signed-rank test. The paired t-test compares the means of two related groups, assuming normality in the differences, and was used to assess whether the mean difference between the proposed model and the baseline model was statistically significant.

To assess the statistical significance of our model’s improvement in EM scores over six state-of-the-art baselines, we conducted both a paired t-test and a Wilcoxon signed-rank test. The t-test yielded a t-value of 4.56 with a p-value of 0.0060, indicating that the observed improvement (EM = 30.3) is statistically significant at the 5% significance level. To complement this, we applied the Wilcoxon signed-rank test, a non-parametric alternative that does not assume normality and is particularly appropriate given the small sample size (n = 6). This test produced a W statistic of 0.0 with a p-value of 0.0312, further corroborating the statistical significance of our results. As both tests yielded p-values below 0.05, the findings consistently demonstrate that our proposed model offers a significant and robust improvement over existing baseline models.

Additionally, we conducted both a paired t-test and a Wilcoxon signed-rank test comparing BLEU scores against the state-of-the-art models. The paired t-test yielded a t-statistic of 3.23 with a p-value of 0.0232, while the Wilcoxon signed-rank test produced a test statistic of 0.0 with a p-value of 0.0313. Both tests indicate that the improvement in BLEU score achieved by our model (81.4) over the baselines is statistically significant at the 0.05 level. These results provide strong evidence that our model offers a meaningful advancement in translation quality.

4.6. Interpretability Analysis via LIME and SHAP

To improve the interpretability of the generated code, we applied model-agnostic techniques such as SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) and LIME (Local Interpretable Model-agnostic Explanations). These tools enabled a detailed analysis of how specific input tokens influenced the inclusion of critical code attributes like taunt = True and divine_shield = True in the generated output. By attributing predictive weight to different parts of the input prompt, SHAP and LIME provided actionable insights into the decision-making behavior of the text-to-code model. This layer of transparency is especially valuable for software engineering applications, where understanding why and how certain implementation details are generated is essential for debugging, validation, and refining prompt engineering strategies.

Using SHAP and LIME, we investigated a syntactic and semantic error in the machine-generated code for a digital card game object, Annoy-o-Tron. Table 4 shows hypothetical SHAP results. SHAP analysis revealed that the incorrect assignment expression True = True had the most significant negative impact on the model’s predicted correctness, with a SHAP value of -0.65. This indicates a strong, detrimental influence due to syntactic invalidity. Conversely, the absence of the keyword argument taunt = True—present in the reference implementation—contributed negatively with a SHAP value of −0.35, suggesting that the model failed to include an essential semantic feature. LIME corroborated these findings by demonstrating that perturbing the erroneous token (True = True) led to a substantial shift in the local surrogate model’s prediction probability, reinforcing its criticality.

Table 4.

Hypothetical SHAP results.

Table 5 presents the results of a LIME-based consistency analysis across multiple prompt variations, evaluating the stability of feature importance for key attributes in card generation. The feature taunt = True demonstrated high consistency, appearing in the top explanations an average of 2.4 times per prompt and showing a top token of “taunt” with an average weight of 0.41 and a consistency score of 92%. Similarly, the feature divine_shield = True was also frequently identified, with an average top-token occurrence of 2.7 and a slightly lower average weight of 0.39, yielding an 88% consistency rate. These results suggest that LIME explanations for these domain-relevant features are relatively stable and robust to prompt variation, supporting their interpretability and relevance in model behavior analysis.

Table 5.

LIME explanation consistency across prompts.

4.7. Technical Specifications and Experimental Setup

All experiments were conducted using Google Colab with access to a CUDA 12.5 runtime environment. The system was equipped with approximately 12.67 GB of RAM and ran on a Linux-based operating system (kernel version 6.1.123+ with glibc 2.35). During the experimental phase, we utilized GPU acceleration via Google Colab, where the training sessions were executed on NVIDIA T4 and A100 GPUs. The T4 (Tesla T4) and A100 (Ampere architecture) are high-performance GPUs optimized for AI workloads, including deep learning model training and inference. When assigned by Colab, these GPUs significantly accelerate computation through CUDA support, which is leveraged by frameworks such as TensorFlow and PyTorch. Their use was essential for handling the computational load of our CNN-based encoder–decoder model.

To ensure optimal model performance and enhance the reproducibility of our results, we conducted a systematic hyperparameter tuning process using a grid search strategy. The hyperparameters tuned included the learning rate, batch size, number of convolutional layers, kernel size, dropout rate, and embedding dimension. The search space was informed by prior deep learning literature as well as preliminary exploratory runs. Specifically, the learning rate was varied logarithmically between 10−6 and 10−3, batch sizes ranged from 16 to 60, and convolutional kernel sizes of 3, 5, and 7 were tested. The number of convolutional layers was varied from 2 to 4. For regularization, dropout rates from 0.1 to 0.5 were explored in increments of 0.1.

Each configuration was trained using 80% of the dataset, with the remaining 20% reserved as a validation set. We employed early stopping to prevent overfitting, monitoring BLEU and Acc+ scores on the validation set as the primary evaluation metrics. The final hyperparameter configuration was selected based on the best combined BLEU and Acc+ performance on the validation set, balancing syntactic correctness with semantic alignment. This configuration was then used to retrain the model and report the test results. All experiments were conducted with fixed random seeds to support reproducibility, and the selected configuration details are summarized in the revised manuscript for reference.

Table 6 shows the structure of the CNN encoder–decoder model and training hyperparameters. The most important architectural components in a CNN model include convolutional layers, kernel size, activation function, pooling layers and batch normalization Layers. We use ReLU as an activation function and set the kernel size to 3. In more advanced CNN architectures, attention mechanisms are used to enhance the network’s ability and focus on the most important parts of the input data. Training hyperparameters are used to control the learning process. These parameters are set before training begins and influence the model’s behavior, accuracy, and convergence speed. The most common training hyperparameters include learning rate, batch size, number of epochs, optimizer, weight decay (L2 regularization) and dropout rate. Here, Adam is used as the optimization method. The learning rate is set to 10−6.

Table 6.

The structure of the CNN encoder–decoder model and training hyperparameters.

Table 7 shows the runtime efficiency and memory usage metrics of the proposed model. Runtime efficiency is calculated using inference time, which is the time taken by the model to process an input and produce an output. It is typically measured in seconds per inference. Memory usage is the amount of memory (RAM for CPU or VRAM for GPU) required to load the model and process an input. It includes memory for model weights, activations, and intermediate variables during computation.

Table 7.

Runtime efficiency and memory usage metrics of the proposed model.

Our proposed CNN-based model is designed to scale effectively across datasets of varying sizes, from small to large (HEARTHSTONE, AST2CVCode), demonstrating stable performance in both settings. Training time varies accordingly, ranging from approximately 2 h for smaller datasets to up to 24 h for larger datasets. While CNN architectures are known for fast inference, training on large datasets introduces computational trade-offs, including increased memory usage and longer training durations. Nonetheless, the model maintains consistent accuracy and inference efficiency, making it practical for real-world deployment.

One potential limitation of this study is the relatively small size of the computer vision dataset (n = 65), which may not fully capture the diversity and complexity required for robust deep learning model training. While this dataset offers valuable insights into the performance of the proposed BLEU+ metric in evaluating source code generated for computer vision tasks, the small sample size may limit the generalizability of our findings to larger, more complex datasets. Deep learning models typically require larger, more diverse datasets to achieve optimal generalization, and the current dataset may not provide enough variation to test the model’s full potential. Future work should involve expanding the dataset to include a broader range of computer vision tasks, which would help to validate the findings presented here and improve the robustness of the model’s performance. Acknowledging this limitation, we suggest that the results, while promising, be interpreted with caution and supplemented with further experiments on larger datasets in future studies.

While the newly introduced AST2CVCode dataset contains only 65 code snippets and serves as a focused benchmark for structured code generation tasks, we also evaluated our proposed model on a significantly larger and well-established dataset—HEARTHSTONE—to verify its generalization capabilities. This additional evaluation allowed us to assess the model’s performance across different data distributions and scales. The results on the HEARTHSTONE dataset demonstrate that our model generalizes effectively beyond small datasets, confirming its robustness and adaptability to more complex and diverse code generation scenarios. A detailed analysis of dataset augmentation techniques and their impact on performance is considered a promising direction for future research.

In the implementation of source code generation for the HEARTHSTONE dataset, there are several challenges, such as data quality limitations, computational constraints, and convergence issues.

Data quality limitations affect the model’s performance; these limitations include domain-specific language and keywords. HEARTHSTONE uses specialized terms and keywords (e.g., “Battlecry” and “Deathrattle”) that may not be well understood by general-purpose code generation models. Misinterpretation of these terms leads to code that does not reflect the intended card functionality. We resolve this issue by fine-tuning the model with HEARTHSTONE-specific terminology and syntax, so it learns to recognize and handle these terms correctly. Addressing these data quality limitations with a careful fine-tuning approach improves the accuracy and robustness of our proposed model for the HEARTHSTONE dataset, leading to better performance and consistency in real-world applications.

While our proposed model is designed for structured and well-formed input descriptions, we recognize that real-world applications often involve noisy, ambiguous, or underspecified program instructions. To address this, our approach leverages grammar-constrained decoding and tree-based structural representations, which help maintain syntactic validity even when input quality degrades. However, ensuring robustness to input uncertainty remains a significant challenge. However, in future work, we plan to systematically evaluate the model’s performance across varying levels of input perturbation and investigate techniques, such as data augmentation and uncertainty-aware decoding, to enhance its robustness in practical scenarios.

The computational constraints challenge mainly focuses on the resource-intensive nature of training and fine-tuning the models for source code generation. Training and fine-tuning source code generation models that include complex gaming logic (like the HEARTHSTONE dataset) requires intensive computational resources to support feasible training times. We address this issue by employing a GPU to accelerate the training process.

Convergence issues occur due to the difficulties in optimizing the model’s performance to generate consistent code. These issues include producing incomplete or incorrect code, overfitting training data, or failing to generalize to new data. The most common convergence challenge is overfitting to training data; the model may overfit to specific code patterns in the training data, leading to poor performance with the new code. This is particularly difficult with the HEARTHSTONE dataset, where some code patterns may appear infrequently. To avoid overfitting, we use regularization techniques such as dropout, weight decay, and batch normalization. The divergence during training is one of the convergence challenges; the model may fail to converge because the training process is unstable, where the loss fails to decrease consistently. This is typically caused by a high learning rate or improper model initialization. We address this challenge by implementing a learning rate scheduler and reducing the learning rate to improve training stability and convergence. Moreover, HEARTHSTONE source code involves long code snippets and complex sequences of actions, which can lead to poor convergence as models struggle with long-term dependencies. We resolve this issue by using attention mechanisms and CNN architectures instead of traditional RNNs; this can help manage long sequences effectively and improve convergence.

5. Conclusions and Future Work

In this paper, we adopted a deep learning approach for source code generation to enhance the performance of computer vision systems and reduce the development time of these systems. The proposed model uses a grammar-based CNN and tree-based approach to improve the accuracy of source code generation tasks.

In this study, we focus solely on the proposed CNN framework and do not include comparisons with alternative architectures such as transformers or RNNs. Evaluating training efficiency across different model families remains a direction for future work.

Moreover, we created a new specific dataset, called AST2CVCode, for computer vision applications, and then we applied and evaluated the proposed model on this dataset.

We conducted various experiments to evaluate and validate our proposed model on the HEARTHSTONE and AST2CVCode datasets. The experimental results show that we achieve substantially better performance compared to previous approaches.

For future direction, we are interested in exploring other datasets to verify the model’s ability for structural data. Also, the performance improvements in code generation models largely rely on the scaling up of both the model and the training, which requires significant computational resources. Thus, future research in this area can look into designing more efficient models that generate code conforming to certain preset standards. Moreover, a hybrid approach of merging CNNs for local patterns and transformers for global context can be a future direction that employs the strengths of both architectures.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.K.J.; methodology, W.A. and S.K.J.; software, W.A.; validation, W.A. and S.K.J.; formal analysis, W.A., S.K.J., and A.A.; investigation, W.A.; resources, W.A.; data curation, W.A.; writing—original draft preparation, W.A.; writing—review and editing, S.K.J. and A.A.; visualization, W.A., S.K.J., and A.A.; supervision, S.K.J. and A.A.; project administration, S.K.J. and A.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Deanship of Scientific Research (DSR), King Abdulaziz University, Jeddah, under Grant No. (KEP-3-612-1439). The authors, therefore, gratefully acknowledge DSR technical and financial support.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Liu, H.; Shen, M.; Zhu, J.; Niu, N.; Li, G.; Zhang, L. Deep learning based program generation from requirements text: Are we there yet? IEEE Trans. Softw. Eng. 2020, 48, 1268–1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, W.; Grefenstette, E.; Hermann, K.M.; Kočiský, T.; Senior, A.; Wang, F.; Blunsom, P. Latent Predictor Networks for Code Generation. In Proceedings of the 54th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers), Berlin, Germany, 7–12 August 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, P.; Neubig, G. A Syntactic Neural Model for General-Purpose Code Generation. In Proceedings of the 55th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 30 July–4 August 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabinovich, M.; Stern, M.; Klein, D. Abstract Syntax Networks for Code Generation and Semantic Parsing. In Proceedings of the 55th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 30 July–4 August 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayati, S.A.; Olivier, R.; Avvaru, P.; Yin, P.; Tomasic, A.; Neubig, G. Retrieval-Based Neural Code Generation. In Proceedings of the 2018 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, Brussels, Belgium, 31 October–4 November 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, P.; Neubig, G. TRANX: A Transition-based Neural Abstract Syntax Parser for Semantic Parsing and Code Generation. In Proceedings of the 2018 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing: System Demonstrations, Brussels, Belgium, 31 October–4 November 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashimoto, T.B.; Guu, K.; Oren, Y.; Liang, P. A retrieve-and-edit framework for predicting structured outputs. In Proceedings of the 32nd International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, Montréal, QC, Canada, 3–8 December 2018; Volume 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Zhu, Q.; Mou, L.; Xiong, Y.; Li, G.; Zhang, L. A grammar-based structural cnn decoder for code generation. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Honolulu, HI, USA, 27 January–1 February 2019; Volume 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiwang, R.; Oladunni, T.; Xu, W. A Deep Learning Model for Source Code Generation. In Proceedings of the 2019 SoutheastCon, Huntsville, AL, USA, 11–14 April 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, L.; Mao, X.; Zhang, Z. Language to Code with Open Source Software. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE 10th International Conference on Software Engineering and Service Science (ICSESS), Beijing, China, 18–20 October 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Z.; Guo, D.; Tang, D.; Duan, N.; Feng, X.; Gong, M.; Shou, L.; Qin, B.; Liu, T.; Jiang, D.; et al. CodeBERT: A Pre-Trained Model for Programming and Natural Languages. In Proceedings of the Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: EMNLP 2020, Online, 16–20 November 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Tworek, J.; Jun, H.; Yuan, Q.; Pinto, H.P.d.O.; Kaplan, J.; Edwards, H.; Burda, Y.; Joseph, N.; Brockman, G.; et al. Evaluating Large Language Models Trained on Code. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2107.03374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, T.B.; Mann, B.; Ryder, N.; Subbiah, M.; Kaplan, J.; Dhariwal, P.; Neelakantan, A.; Shyam, P.; Sastry, G.; Askell, A.; et al. Language models are few-shot learners. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2005.14165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sajad, N.; Tang, K.; Cao, Y. Code generation from natural language with less prior knowledge and more monolingual data. In Proceedings of the 59th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics and the 11th International Joint Conference on Natural Language Processing (Volume 2: Short Papers), Online, 1–6 August 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, W.; Joty, S.; Hoi, S.C.H. CodeT5: Identifier-aware Unified Pre-trained Encoder-Decoder Models for Code Understanding and Generation. In Proceedings of the 2021 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, Punta Cana, Dominican Republic, 7–11 November 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y.; Li, G.; Jiang, X.; Jin, Z. Antecedent Predictions Are More Important Than You Think: An Effective Method for Tree-Based Code Generation. In Proceedings of the 26th European Conference on Artificial Intelligence ECAI 2023, Kraków, Poland, 30 September–4 October 2023; pp. 565–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y.; Li, G.; Jin, Z. CODEP: Grammatical seq2seq model for general-purpose code generation. In Proceedings of the 32nd ACM SIGSOFT International Symposium on Software Testing and Analysis, Seattle, WA, USA, 17–21 July 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tipirneni, S.; Zhu, M.; Reddy, C.K. Structcoder: Structure-aware transformer for code generation. ACM Trans. Knowl. Discov. Data 2024, 18, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gemmell, C.; Rossetto, F.; Dalton, J. Relevance transformer: Generating concise code snippets with relevance feedback. In Proceedings of the 43rd International ACM SIGIR Conference on Research and Development in Information Retrieval, Virtual, 25–30 July 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Choi, D.; Chung, J.; Kushman, N.; Schrittwieser, J.; Leblond, R.; Eccles, T.; Keeling, J.; Gimeno, F.; Lago, A.D.; et al. Competition-level code generation with alphacode. Science 2022, 378, 1092–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, F.F.; Alon, U.; Neubig, G.; Hellendoorn, V.J. A systematic evaluation of large language models of code. In Proceedings of the 6th ACM SIGPLAN International Symposium on Machine Programming, San Diego, CA, USA, 13 June 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fried, D.; Aghajanyan, A.; Lin, J.; Wang, S.; Wallace, E.; Shi, F.; Zhong, R.; Yih, W.; Zettlemoyer, L.; Lewis, M. InCoder: A Generative Model for Code Infilling and Synthesis. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2204.05999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, S.; Guo, D.; Lu, S.; Zhou, L.; Liu, S.; Tang, D.; Sundaresan, N.; Zhou, M.; Blanco, A.; Ma, S. CodeBLEU: A Method for Automatic Evaluation of Code Synthesis. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2009.10297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Zendehdel, N.; Leu, M.C.; Yin, Z. Fine-grained activity classification in assembly based on multi-visual modalities. J. Intell. Manuf. 2024, 35, 2215–2233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Zendehdel, N.; Leu, M.C.; Yin, Z. A gaze-driven manufacturing assembly assistant system with integrated step recognition, repetition analysis, and real-time feedback. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2025, 144, 110076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, G.; Liu, Z.; Van Der Maaten, L.; Weinberger, K.Q. Densely connected convolutional networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshehri, W.S.; Jarraya, S.K.; Allinjawi, A.A. AST2CVCode: A New Benchmark Dataset for Source Code Generation on Computer Vision Applications. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Advanced Intelligent Systems for Sustainable Development, Tanger, Morocco, 21–23 May 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).