Improved Productivity Using Deep Learning-Assisted Major Coronal Curve Measurement on Scoliosis Radiographs

Abstract

1. Introduction

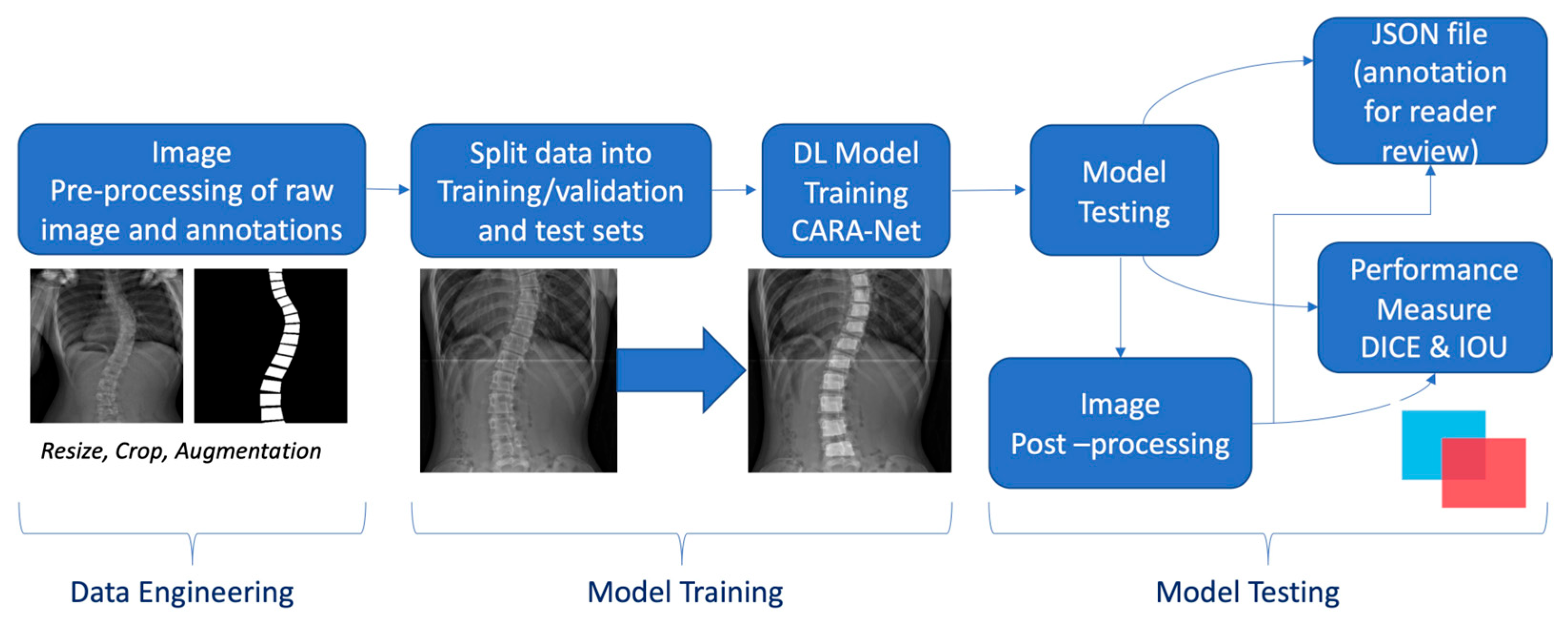

2. Materials and Methods

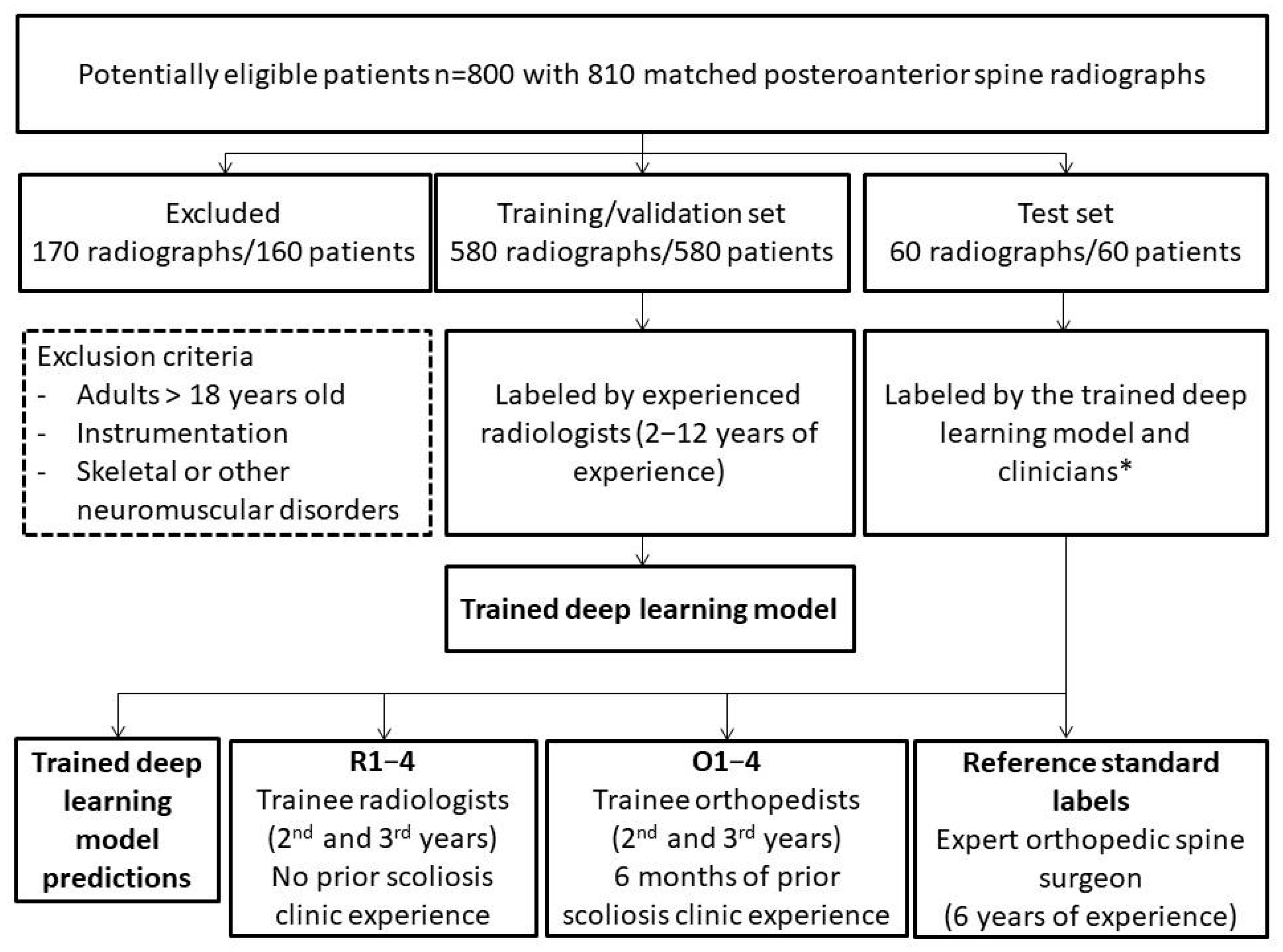

2.1. Scoliosis Dataset

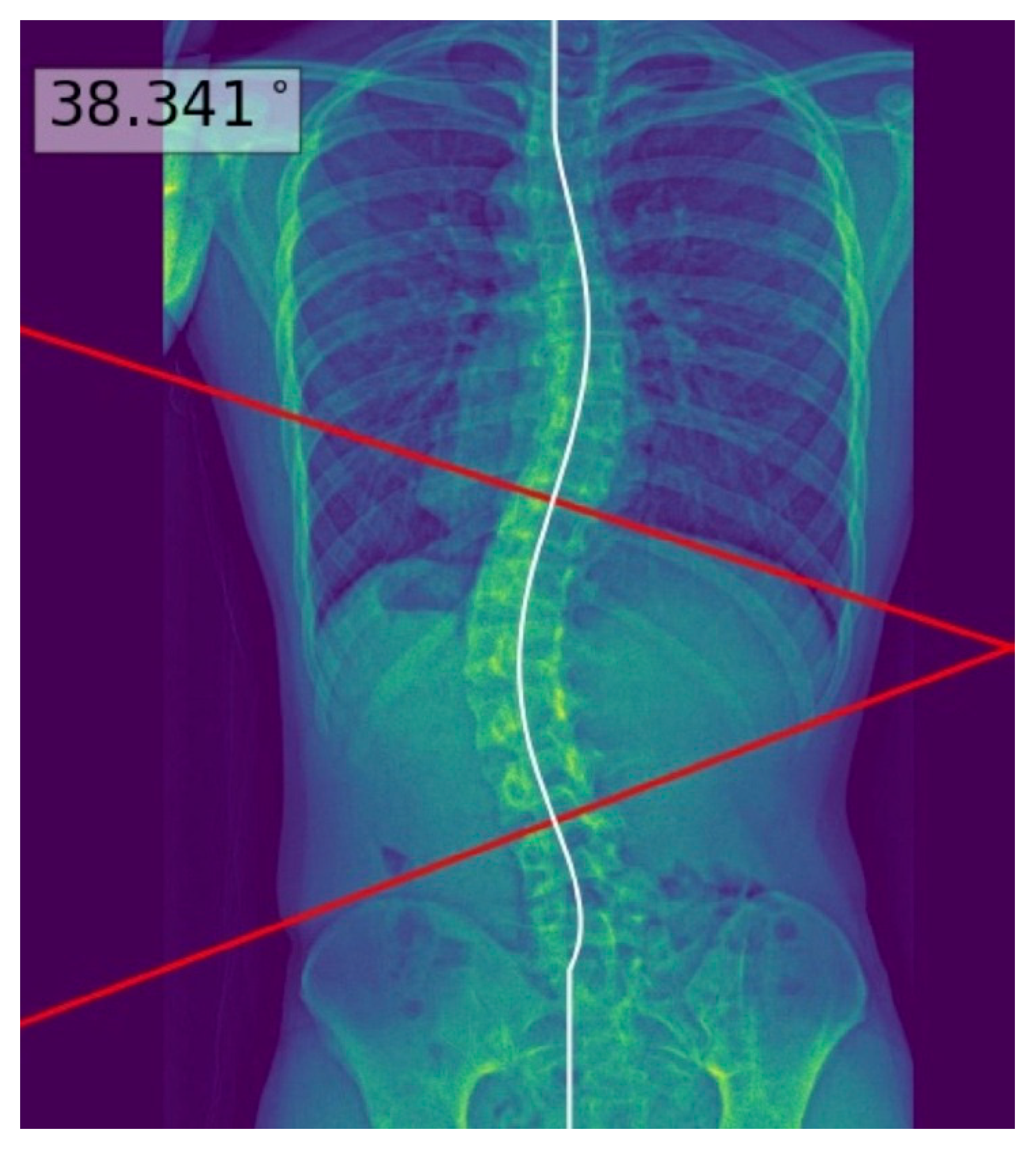

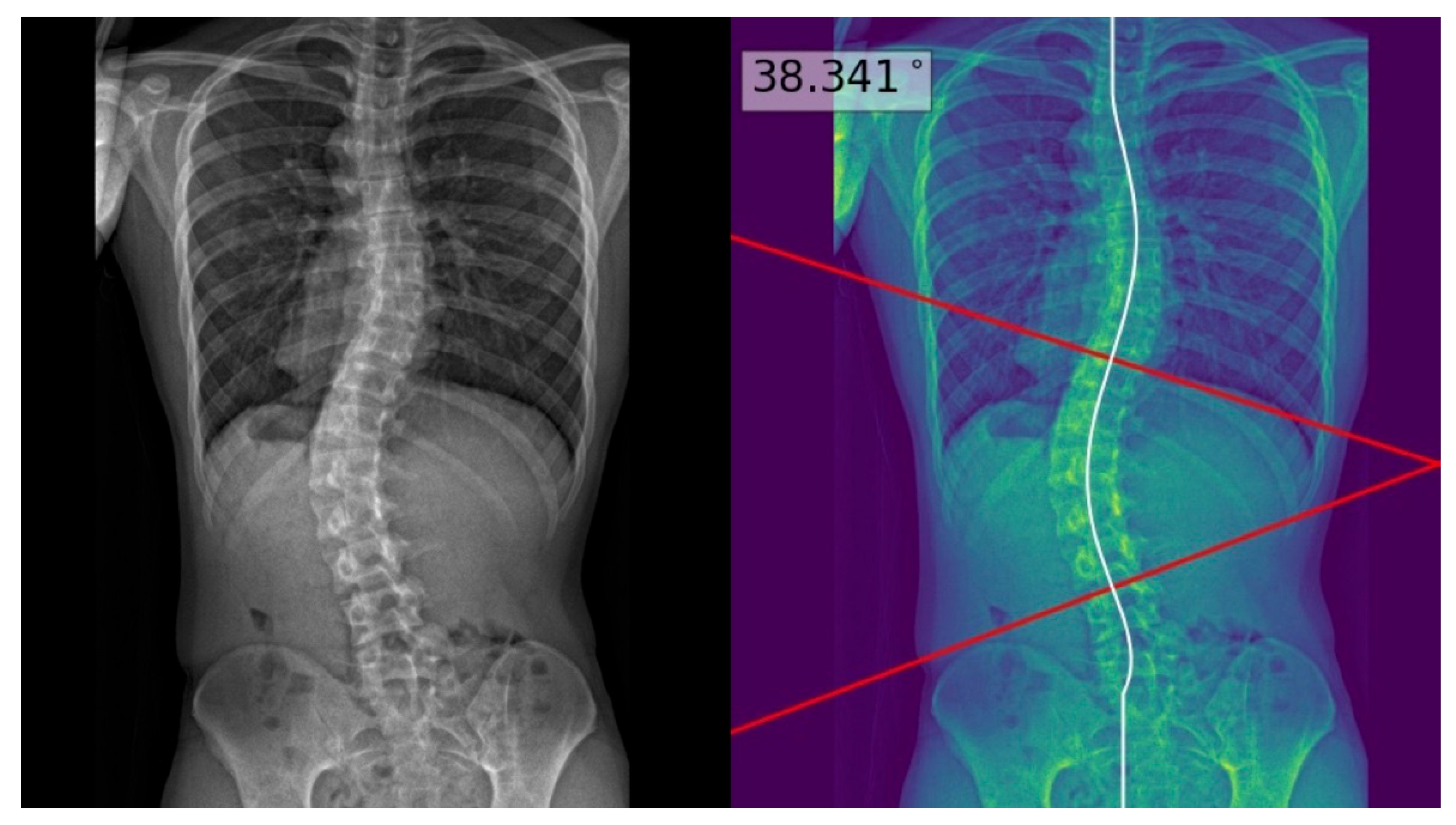

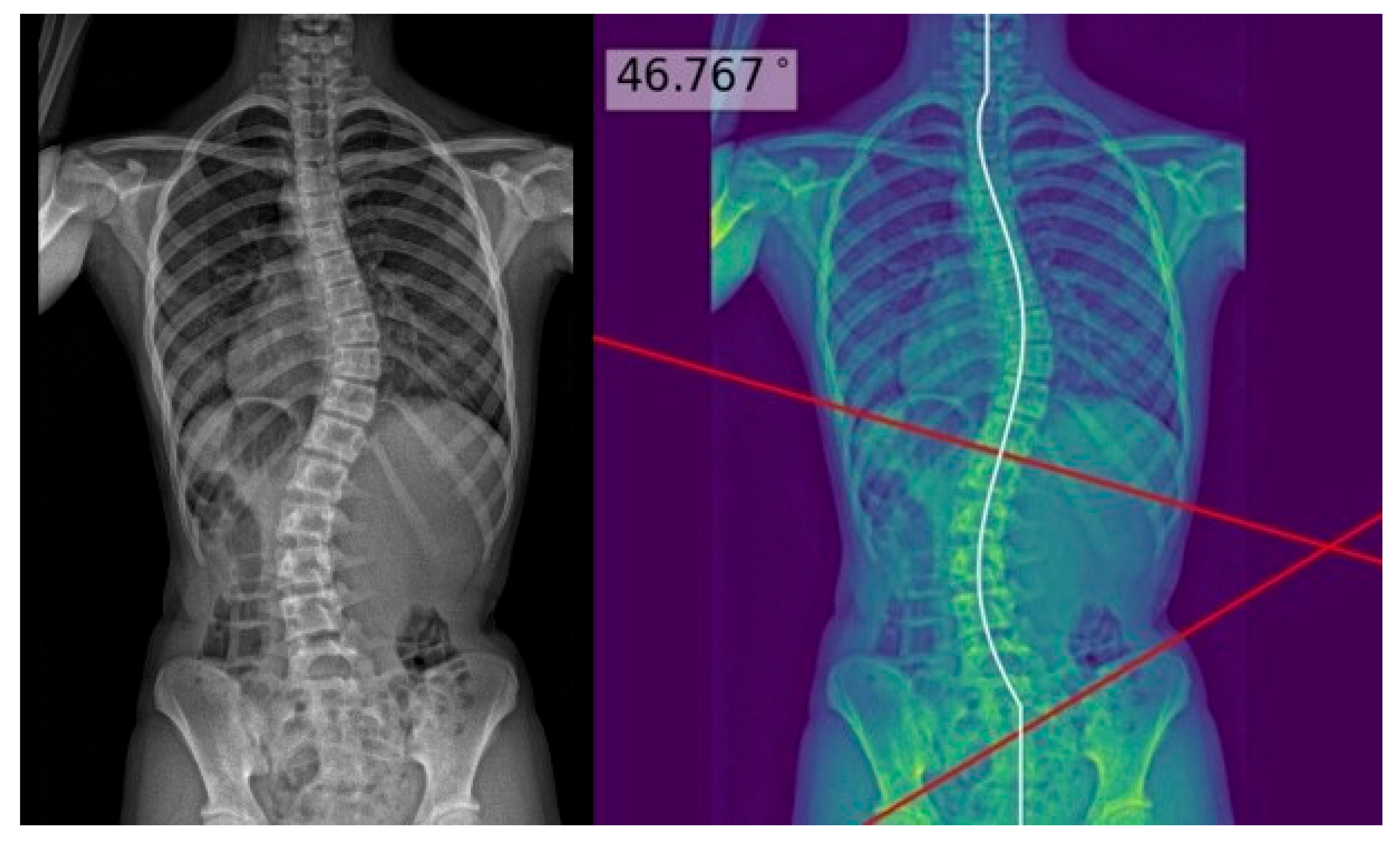

2.2. Context Axial Reverse Attention Network (CaraNet) Object Detection Model

2.3. Deep Learning Model Development

2.4. Reference Standard

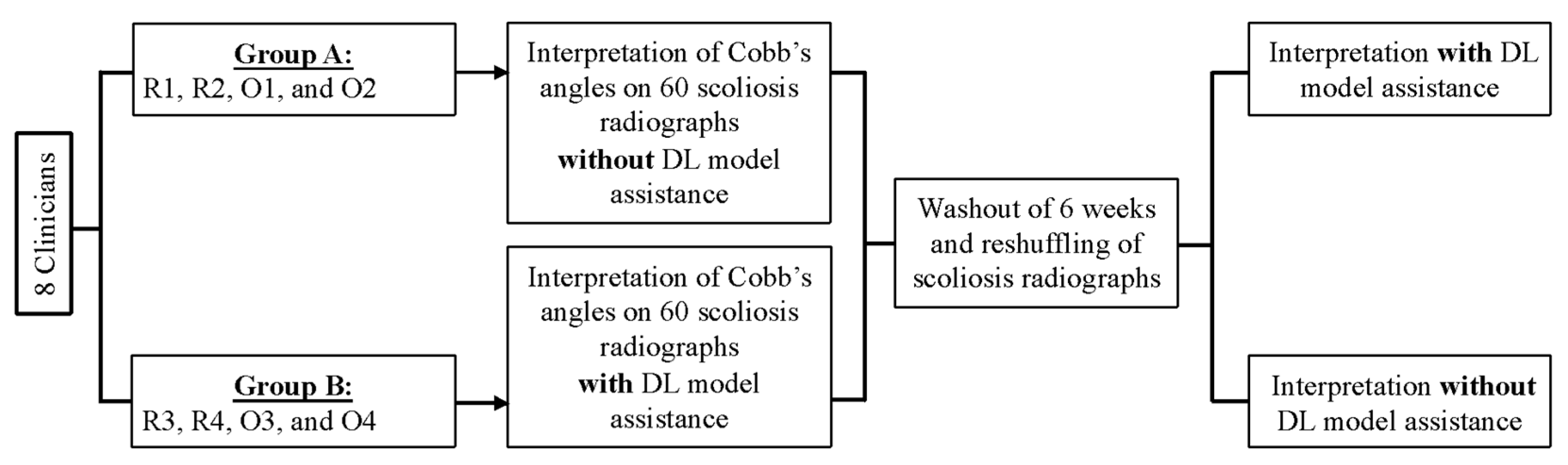

2.5. Study Design

2.6. Radiographic Assessment

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Patient Characteristics

3.2. Scoliotic Curve Characteristics

3.3. Major Coronal Curve Accuracy

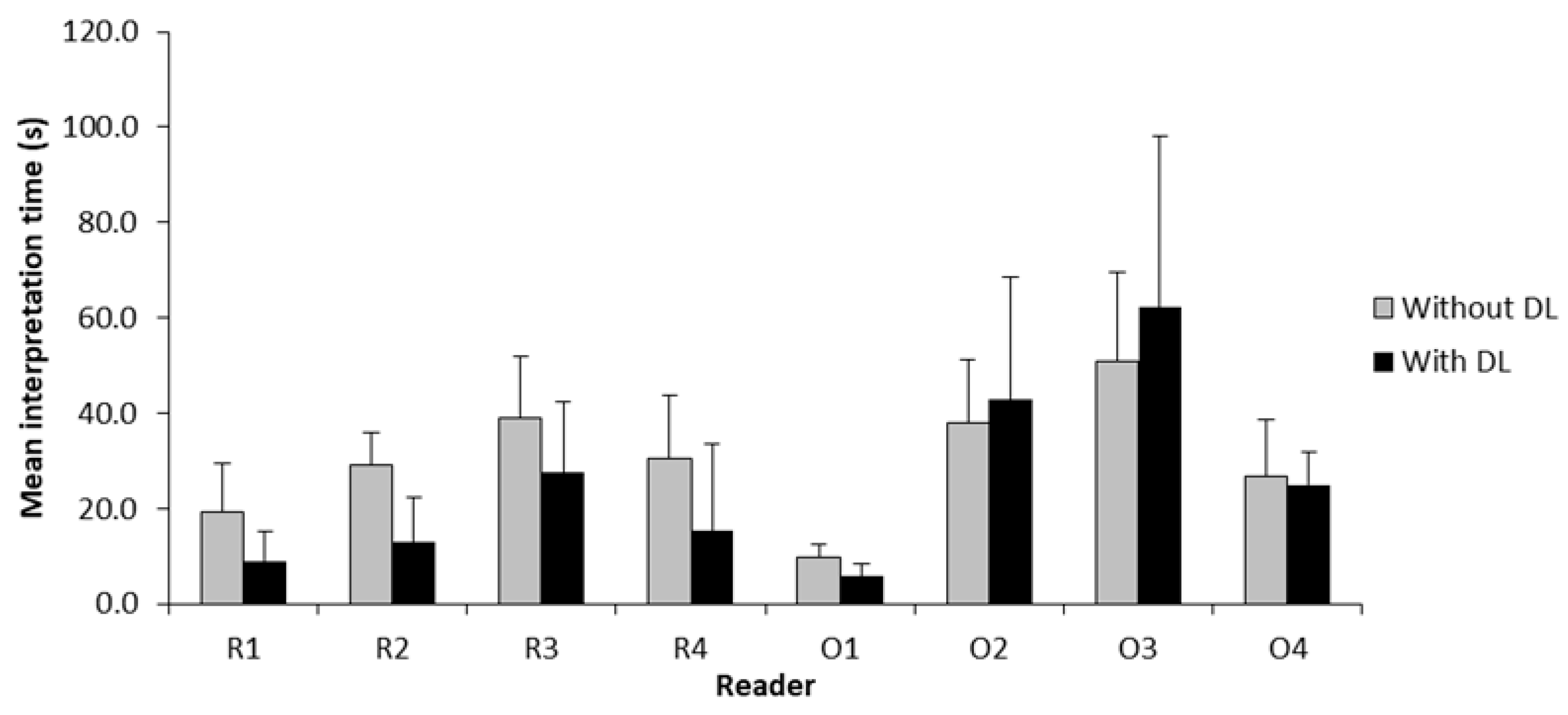

3.4. Interpretation Time

4. Discussion

4.1. Time Savings and Improved Diagnostic Efficiency

4.2. Clinical Impact and Cost-Effectiveness Thresholds

4.3. Impact of Experience Level of Readers and Clinical Implications

4.4. Study Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AIS | Adolescent idiopathic scoliosis |

| ANOVA | Analysis of variance |

| CaraNet | Context Axial Reverse Attention Network |

| CI | Confidence interval |

| CNN | Convolutional neural networks |

| DICOM | Digital Imaging and Communications in Medicine |

| DL | Deep learning |

| MRI | Magnetic resonance imaging |

| PACS | Picture Archiving and Communication System |

| SD | Standard deviation |

Appendix A

Appendix A.1. Deep Learning Model Development

References

- Dunn, J.; Henrikson, N.B.; Morrison, C.C.; Blasi, P.R.; Nguyen, M.; Lin, J.S. Screening for Adolescent Idiopathic Scoliosis: Evidence Report and Systematic Review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA 2018, 319, 173–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jinnah, A.H.; Lynch, K.A.; Wood, T.R.; Hughes, M.S. Adolescent Idiopathic Scoliosis: Advances in Diagnosis and Management. Curr. Rev. Musculoskelet. Med. 2025, 18, 54–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, J.J.; Stans, A.A.; Milbrandt, T.A.; Treder, V.M.; Kremers, H.M.; Shaughnessy, W.J.; Larson, A.N. Does School Screening Affect Scoliosis Curve Magnitude at Presentation to a Pediatric Orthopedic Clinic? Spine Deform 2018, 6, 403–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, H.K.; Hui, J.H.; Rajan, U.; Chia, H.P. Idiopathic scoliosis in Singapore schoolchildren: A prevalence study 15 years into the screening program. Spine 2005, 30, 1188–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Addai, D.; Zarkos, J.; Bowey, A.J. Current concepts in the diagnosis and management of adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. Childs Nerv. Syst. 2020, 36, 1111–1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, J.C.; Castelein, R.M.; Chu, W.C.; Danielsson, A.J.; Dobbs, M.B.; Grivas, T.B.; Gurnett, C.A.; Luk, K.D.; Moreau, A.; Newton, P.O.; et al. Adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2015, 1, 15030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oakley, P.A.; Ehsani, N.N.; Harrison, D.E. The Scoliosis Quandary: Are Radiation Exposures from Repeated X-Rays Harmful? Dose Response 2019, 17, 1559325819852810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oba, H.; Watanabe, K.; Asada, T.; Matsumura, A.; Sugawara, R.; Takahashi, S.; Ueda, H.; Suzuki, S.; Doi, T.; Takeuchi, T.; et al. Effects of Physiotherapeutic Scoliosis-Specific Exercise for Adolescent Idiopathic Scoliosis Cobb Angle: A Systematic Review. Spine Sur. Rel. Res. 2025, 9, 120–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blevins, K.; Battenberg, A.; Beck, A. Management of Scoliosis. Adv. Pediatr. 2018, 65, 249–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tambe, A.D.; Panikkar, S.J.; Millner, P.A.; Tsirikos, A.I. Current concepts in the surgical management of adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. Bone Jt. J. 2018, 100-b, 415–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elfiky, T.; Patil, N.; Shawky, M.; Siam, A.; Ragab, R.; Allam, Y. Oxford Cobbometer Versus Computer Assisted-Software for Measurement of Cobb Angle in Adolescent Idiopathic Scoliosis. Neurospine 2020, 17, 304–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Xing, Y.; Zhao, Z.; Meng, X.; Xu, G.; Hai, Y. Comparison of manual versus automated measurement of Cobb angle in idiopathic scoliosis based on a deep learning keypoint detection technology. Eur. Spine J. 2022, 31, 1969–1978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallinan, J.T.P.D.; Zhu, L.; Yang, K.; Makmur, A.; Algazwi, D.A.R.; Thian, Y.L.; Lau, S.; Choo, Y.S.; Eide, S.E.; Yap, Q.V.; et al. Deep Learning Model for Automated Detection and Classification of Central Canal, Lateral Recess, and Neural Foraminal Stenosis at Lumbar Spine MRI. Radiology 2021, 300, 130–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, D.S.W.; Makmur, A.; Zhu, L.; Zhang, W.; Cheng, A.J.L.; Sia, D.S.Y.; Eide, S.E.; Ong, H.Y.; Jagmohan, P.; Tan, W.C.; et al. Improved Productivity Using Deep Learning–assisted Reporting for Lumbar Spine MRI. Radiology 2022, 305, 160–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S.S.; Azad, T.D.; Suarez, P.A.; Ratliff, J.K. A machine learning approach for predictive models of adverse events following spine surgery. Spine J. 2019, 19, 1772–1781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeVries, Z.; Hoda, M.; Rivers, C.S.; Maher, A.; Wai, E.; Moravek, D.; Stratton, A.; Kingwell, S.; Fallah, N.; Paquet, J.; et al. Development of an unsupervised machine learning algorithm for the prognostication of walking ability in spinal cord injury patients. Spine J. 2020, 20, 213–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azimi, P.; Yazdanian, T.; Benzel, E.C.; Aghaei, H.N.; Azhari, S.; Sadeghi, S.; Montazeri, A. A Review on the Use of Artificial Intelligence in Spinal Diseases. Asian Spine J. 2020, 14, 543–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horng, M.H.; Kuok, C.P.; Fu, M.J.; Lin, C.J.; Sun, Y.N. Cobb Angle Measurement of Spine from X-Ray Images Using Convolutional Neural Network. Comput. Math. Methods Med. 2019, 2019, 6357171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Bailey, C.; Rasoulinejad, P.; Li, S. Automated comprehensive Adolescent Idiopathic Scoliosis assessment using MVC-Net. Med. Image Anal. 2018, 48, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, K.; Xu, N.; Guo, C.; Wu, J. MPF-net: An effective framework for automated cobb angle estimation. Med. Image Anal. 2022, 75, 102277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caesarendra, W.; Rahmaniar, W.; Mathew, J.; Thien, A. Automated Cobb Angle Measurement for Adolescent Idiopathic Scoliosis Using Convolutional Neural Network. Diagnostics 2022, 12, 396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, A.Y.; Do, B.H.; Bartret, A.L.; Fang, C.X.; Hsiao, A.; Lutz, A.M.; Banerjee, I.; Riley, G.M.; Rubin, D.L.; Stevens, K.J.; et al. Automating Scoliosis Measurements in Radiographic Studies with Machine Learning: Comparing Artificial Intelligence and Clinical Reports. J. Digit Imaging 2022, 35, 524–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernstein, P.; Metzler, J.; Weinzierl, M.; Seifert, C.; Kisel, W.; Wacker, M. Radiographic scoliosis angle estimation: Spline-based measurement reveals superior reliability compared to traditional COBB method. Eur. Spine J. 2021, 30, 676–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prestigiacomo, F.G.; Hulsbosch, M.; Bruls, V.E.J.; Nieuwenhuis, J.J. Intra- and inter-observer reliability of Cobb angle measurements in patients with adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. Spine Deform. 2022, 10, 79–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucasti, C.; Haider, M.N.; Marshall, I.P.; Thomas, R.; Scott, M.M.; Ferrick, M.R. Inter- and intra-reliability of Cobb angle measurement in pediatric scoliosis using PACS (picture archiving and communication systems methods) for clinicians with various levels of experience. AME Surg. J. 2023, 3, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lechner, R.; Putzer, D.; Dammerer, D.; Liebensteiner, M.; Bach, C.; Thaler, M. Comparison of two- and three-dimensional measurement of the Cobb angle in scoliosis. Int. Orthop. 2017, 41, 957–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldman, S.N.; Hui, A.T.; Choi, S.; Mbamalu, E.K.; Tirabady, P.; Eleswarapu, A.S.; Gomez, J.A.; Alvandi, L.M.; Fornari, E.D. Applications of artificial intelligence for adolescent idiopathic scoliosis: Mapping the evidence. Spine Deform. 2024, 12, 1545–1570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, W.W.-Y.; Fu, S.-N.; Zheng, Y.-P.; Parent, E.C.; Cheung, J.P.Y.; Zheng, D.K.Y.; Wong, A.Y.L. A Systematic Review of Machine Learning Models for Predicting Curve Progression in Teenagers with Idiopathic Scoliosis. JOSPT Open 2024, 2, 202–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- England, J.R.; Cheng, P.M. Artificial Intelligence for Medical Image Analysis: A Guide for Authors and Reviewers. AJR. Am. J. Roentgenol. 2019, 212, 513–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willemink, M.J.; Koszek, W.A.; Hardell, C.; Wu, J.; Fleischmann, D.; Harvey, H.; Folio, L.R.; Summers, R.M.; Rubin, D.L.; Lungren, M.P. Preparing Medical Imaging Data for Machine Learning. Radiology 2020, 295, 4–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, A.; Guan, S.; Ko, H.; Loew, M.H. (Eds.) CaraNet: Context axial reverse attention network for segmentation of small medical objects. In Medical Imaging 2022: Image Processing; SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, F.; Moehring, A.; Banerjee, O.; Salz, T.; Agarwal, N.; Rajpurkar, P. Heterogeneity and predictors of the effects of AI assistance on radiologists. Nat. Med. 2024, 30, 837–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, A.; Chute, C.; Rajpurkar, P.; Lou, J.; Ball, R.L.; Shpanskaya, K.; Jabarkheel, R.; Kim, L.H.; McKenna, E.; Tseng, J.; et al. Deep Learning–Assisted Diagnosis of Cerebral Aneurysms Using the HeadXNet Model. JAMA Netw. Open 2019, 2, e195600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eng, D.K.; Khandwala, N.B.; Long, J.; Fefferman, N.R.; Lala, S.V.; Strubel, N.A.; Milla, S.S.; Filice, R.W.; Sharp, S.E.; Towbin, A.J.; et al. Artificial Intelligence Algorithm Improves Radiologist Performance in Skeletal Age Assessment: A Prospective Multicenter Randomized Controlled Trial. Radiology 2021, 301, 692–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, J.S.; Ebrahimian, S.; McDermott, S.; Lee, S.; Naccarato, L.; Di Capua, J.F.; Wu, M.Y.; Zhang, E.W.; Muse, V.; Miller, B.; et al. Association of Artificial Intelligence-Aided Chest Radiograph Interpretation with Reader Performance and Efficiency. JAMA Netw. Open 2022, 5, e2229289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brix, M.A.K.; Järvinen, J.; Bode, M.K.; Nevalainen, M.; Nikki, M.; Niinimäki, J.; Lammentausta, E. Financial impact of incorporating deep learning reconstruction into magnetic resonance imaging routine. Eur. J. Radiol. 2024, 175, 111434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garg, T.; John, S.; Abdulkarim, S.; Ahmed, A.D.; Kirubi, B.; Rahman, M.T.; Ubochioma, E.; Creswell, J. Implementation costs and cost-effectiveness of ultraportable chest X-ray with artificial intelligence in active case finding for tuberculosis in Nigeria. PLOS Digit. Health 2025, 4, e0000894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reginster, J.Y.; Schmidmaier, R.; Alokail, M.; Hiligsmann, M. Cost-effectiveness of opportunistic osteoporosis screening using chest radiographs with deep learning in Germany. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 2025, 37, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, L.P.K.; Cheung, P.W.H.; Cheung, J.P.Y. Curve type, flexibility, correction, and rotation are predictors of curve progression in patients with adolescent idiopathic scoliosis undergoing conservative treatment: A systematic review. Bone Jt. J. 2022, 104-b, 424–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benzakour, A.; Altsitzioglou, P.; Lemée, J.M.; Ahmad, A.; Mavrogenis, A.F.; Benzakour, T. Artificial intelligence in spine surgery. Int. Orthop. 2023, 47, 457–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngo, J.; Athreya, K.; Ehrlich, B.; Sayrs, L.; Morphew, T.; Halvorson, S.; Aminian, A. Use of machine learning predictive models in sagittal alignment planning in adolescent idiopathic scoliosis surgery. Eur. Spine J. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tachi, H.; Kato, K.; Abe, Y.; Kokabu, T.; Yamada, K.; Iwasaki, N.; Sudo, H. Surgical Outcome Prediction Using a Four-Dimensional Planning Simulation System with Finite Element Analysis Incorporating Pre-bent Rods in Adolescent Idiopathic Scoliosis: Simulation for Spatiotemporal Anatomical Correction Technique. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2021, 9, 746902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Huang, C.; Wang, D.; Li, K.; Han, X.; Chen, X.; Li, Z. Artificial Intelligence in Scoliosis: Current Applications and Future Directions. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 7382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yahara, Y.; Tamura, M.; Seki, S.; Kondo, Y.; Makino, H.; Watanabe, K.; Kamei, K.; Futakawa, H.; Kawaguchi, Y. A deep convolutional neural network to predict the curve progression of adolescent idiopathic scoliosis: A pilot study. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2022, 23, 610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rainey, C.; O’Regan, T.; Matthew, J.; Skelton, E.; Woznitza, N.; Chu, K.Y.; Goodman, S.; McConnell, J.; Hughes, C.; Bond, R.; et al. UK reporting radiographers’ perceptions of AI in radiographic image interpretation-Current perspectives and future developments. Radiography 2022, 28, 881–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung, J.; Park, S.; Lee, S.M.; Bae, W.; Park, B.; Jung, E.; Seo, J.B.; Jung, K.-H. Added Value of Deep Learning–based Detection System for Multiple Major Findings on Chest Radiographs: A Randomized Crossover Study. Radiology 2021, 299, 450–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, S.; Song, H.; Shin, Y.J.; Kim, J.; Kim, J.; Lee, K.W.; Lee, S.S.; Lee, W.; Lee, S.; Lee, K.H. Deep Learning-based Automatic Detection Algorithm for Reducing Overlooked Lung Cancers on Chest Radiographs. Radiology 2020, 296, 652–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murata, M.; Ariji, Y.; Ohashi, Y.; Kawai, T.; Fukuda, M.; Funakoshi, T.; Kise, Y.; Nozawa, M.; Katsumata, A.; Fujita, H.; et al. Deep-learning classification using convolutional neural network for evaluation of maxillary sinusitis on panoramic radiography. Oral Radiol. 2019, 35, 301–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.H.; Han, S.G.; Cho, A.; Shin, H.J.; Baek, S.E. Effect of deep learning-based assistive technology use on chest radiograph interpretation by emergency department physicians: A prospective interventional simulation-based study. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 2021, 21, 311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seah, J.C.Y.; Tang, C.H.M.; Buchlak, Q.D.; Holt, X.G.; Wardman, J.B.; Aimoldin, A.; Esmaili, N.; Ahmad, H.; Pham, H.; Lambert, J.F.; et al. Effect of a comprehensive deep-learning model on the accuracy of chest x-ray interpretation by radiologists: A retrospective, multireader multicase study. Lancet Digit. Health 2021, 3, e496–e506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayashi, D.; Regnard, N.E.; Ventre, J.; Marty, V.; Clovis, L.; Lim, L.; Nitche, N.; Zhang, Z.; Tournier, A.; Ducarouge, A.; et al. Deep learning algorithm enables automated Cobb angle measurements with high accuracy. Skelet. Radiol. 2025, 54, 1469–1478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molière, S.; Hamzaoui, D.; Granger, B.; Montagne, S.; Allera, A.; Ezziane, M.; Luzurier, A.; Quint, R.; Kalai, M.; Ayache, N.; et al. Reference standard for the evaluation of automatic segmentation algorithms: Quantification of inter observer variability of manual delineation of prostate contour on MRI. Diagn. Interv. Imaging 2024, 105, 65–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Eekelen, L.; Spronck, J.; Looijen-Salamon, M.; Vos, S.; Munari, E.; Girolami, I.; Eccher, A.; Acs, B.; Boyaci, C.; de Souza, G.S.; et al. Comparing deep learning and pathologist quantification of cell-level PD-L1 expression in non-small cell lung cancer whole-slide images. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 7136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filice, R.W.; Ratwani, R.M. The Case for User-Centered Artificial Intelligence in Radiology. Radiol. Artif. Intell. 2020, 2, e190095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Characteristics | Test Set (n = 60) |

|---|---|

| Age (years), mean ± standard deviation (range) | 12.6 ± 2.0 (10–18) |

| Sex, n (%) | |

| Female | 43 (71.7) |

| Male | 17 (28.3) |

| Reference standard scoliosis grading (Cobb’s angle), n (%) | |

| Mild (10–24°) | 30 (50.0) |

| Moderate (25–40°) | 25 (41.6) |

| Severe (>40°) | 5 (8.3) |

| ANOVA (DL-Assisted V. Unassisted) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reader | DL Assistance | Mean Angle Difference (°) | 95% CI | F-Statistic | p-Value |

| DL | - | 3.9 | −5.9 to 8.8 | - | - |

| R1 | No | −2.0 | −3.1 to −1.0 | 21.65 | <0.001 * |

| Yes | 1.4 | 0.4 to 2.4 | |||

| R2 | No | 0.1 | −0.9 to 1.1 | 0.23 | 0.630 |

| Yes | 0.5 | −0.5 to 1.4 | |||

| R3 | No | −0.1 | −1.0 to 0.8 | 0.17 | 0.900 |

| Yes | −0.2 | −1.1 to 0.7 | |||

| R4 | No | −3.2 | −4.2 to −2.1 | 20.46 | <0.001 * |

| Yes | 1.0 | −0.5 to 2.6 | |||

| O1 | No | −0.5 | −1.6 to 0.6 | 1.03 | 0.310 |

| Yes | 0.5 | −1.1 to 2.0 | |||

| O2 | No | −0.9 | −1.9 to 0.2 | 0.01 | 0.940 |

| Yes | −0.8 | −1.7 to 0.1 | |||

| O3 | No | −2.4 | −4.0 to −0.8 | 4.37 | 0.039 * |

| Yes | −0.5 | −1.4 to 0.3 | |||

| O4 | No | 1.2 | 0.3 to 2.1 | 0.98 | 0.330 |

| Yes | 0.5 | −0.5 to 1.6 | |||

| Reader | Mean Difference | 95% CI | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Timing (s) 1 | Ortho | 3.9 | −2.9 to 10.6 | 0.005 |

| Radio | −13.3 | −19.6 to −6.9 | ||

| Accuracy (°) 2 | Ortho | −0.3 | −1.4 to 0.8 | >0.05 |

| Radio | −0.4 | −1.6 to 0.8 |

| Reader | DL Assistance | Interpretation Time (s), Mean ± SD | Mean Difference (s) | 95% CI | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R1 | No | 19.3 ± 10.1 | −10.4 | −13.2 to −7.6 | <0.001 * |

| Yes | 8.9 ± 6.4 | ||||

| R2 | No | 29.0 ± 6.9 | −16.0 | −18.7 to −13.3 | <0.001 * |

| Yes | 13.0 ± 9.5 | ||||

| R3 | No | 39.1 ± 12.9 | −11.5 | −16.3 to −6.8 | <0.001 * |

| Yes | 27.6 ± 14.8 | ||||

| R4 | No | 30.4 ± 13.3 | −15.1 | −21.2 to −9.0 | <0.001 * |

| Yes | 15.3 ± 18.3 | ||||

| O1 | No | 9.7 ± 2.8 | −3.9 | −4.9 to −2.9 | <0.001 * |

| Yes | 5.8 ± 2.6 | ||||

| O2 | No | 37.9 ± 13.4 | 4.9 | −2.4 to 12.2 | 0.186 |

| Yes | 42.8 ± 25.9 | ||||

| O3 | No | 50.8 ± 18.8 | 11.4 | 0.1 to 22.6 | 0.047 * |

| Yes | 62.2 ± 35.9 | ||||

| O4 | No | 26.9 ± 11.8 | −2.1 | −5.4 to 1.3 | 0.220 |

| Yes | 24.9 ± 6.9 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Low, X.Z.; Furqan, M.S.; Ng, K.W.; Makmur, A.; Lim, D.S.W.; Kuah, T.; Lee, A.; Lee, Y.J.; Liu, R.W.; Wang, S.; et al. Improved Productivity Using Deep Learning-Assisted Major Coronal Curve Measurement on Scoliosis Radiographs. AI 2025, 6, 318. https://doi.org/10.3390/ai6120318

Low XZ, Furqan MS, Ng KW, Makmur A, Lim DSW, Kuah T, Lee A, Lee YJ, Liu RW, Wang S, et al. Improved Productivity Using Deep Learning-Assisted Major Coronal Curve Measurement on Scoliosis Radiographs. AI. 2025; 6(12):318. https://doi.org/10.3390/ai6120318

Chicago/Turabian StyleLow, Xi Zhen, Mohammad Shaheryar Furqan, Kian Wei Ng, Andrew Makmur, Desmond Shi Wei Lim, Tricia Kuah, Aric Lee, You Jun Lee, Ren Wei Liu, Shilin Wang, and et al. 2025. "Improved Productivity Using Deep Learning-Assisted Major Coronal Curve Measurement on Scoliosis Radiographs" AI 6, no. 12: 318. https://doi.org/10.3390/ai6120318

APA StyleLow, X. Z., Furqan, M. S., Ng, K. W., Makmur, A., Lim, D. S. W., Kuah, T., Lee, A., Lee, Y. J., Liu, R. W., Wang, S., Tan, H. W. N., Hui, S. J., Lim, X., Seow, D., Chan, Y. H., Hirubalan, P., Kumar, L., Tan, J. H. J., Lau, L.-L., & Hallinan, J. T. P. D. (2025). Improved Productivity Using Deep Learning-Assisted Major Coronal Curve Measurement on Scoliosis Radiographs. AI, 6(12), 318. https://doi.org/10.3390/ai6120318