4.1. Experiment Settings

• Evaluation Metrics

Named entity recognition (NER) tasks typically rely on Precision (P), Recall (R), and F1-Score for evaluation. Precision calculates the ratio of correctly identified positives to all predicted positives, while Recall measures the percentage of actual positives correctly predicted. Since these metrics often conflict, the F1-Score combines them to offer a balanced evaluation. The formulas are expressed as

Here, , , and refer to True Positive, False Positive, and False Negative, respectively. These terms define correctly or incorrectly classified positive and negative examples. Following common practice in certain Chinese NER research, our evaluation is performed at the strict entity-level, requiring an exact match of entity boundaries (start and end positions) for a prediction to be considered correct. (This evaluation approach aligns with methodologies commonly adopted in Chinese NER research for baselines referenced in this work, focusing strictly on entity boundary correctness. We acknowledge that alternative stricter evaluation metrics (e.g., requiring both boundary and entity type match) exist in the broader NER literature.)

• Datasets

Experiments were conducted on four representative Chinese NER datasets, summarized in

Table 1. These datasets cover diverse domains and linguistic styles, allowing for a comprehensive evaluation of our model’s robustness and generalization capabilities in addressing the unique challenges of Chinese NER. The datasets are

OntoNotes 4.0 [

36]: A large-scale multilingual annotated corpus, with its Chinese portion focusing on news texts. It features a rich variety of entity types and relatively longer sentence structures, presenting challenges related to complex contextual understanding and fine-grained entity classification.

MSRA [

37]: A widely used news dataset, primarily tagged with three common entity types: Location (LOC), Person (PER), and Organization (ORG). Its relatively uniform domain provides a benchmark for general NER performance, while still challenging in identifying entity boundaries in fluent Chinese text.

Resume [

38]: A domain-specific corpus from Sina Finance, annotated with eight entity types pertinent to resumes. This dataset highlights challenges in fine-grained, domain-specific entity recognition, often characterized by concise expressions and potentially scarce training examples for certain entity types.

Weibo [

39]: A social media dataset from Sina Weibo, annotated with entities such as Person (PER), Organization (ORG), Geo-Political Entity (GPE), and Location (LOC). The informal, noisy, and short-text nature of social media data poses significant challenges, including ambiguous entity boundaries, diverse expression forms, and a higher prevalence of non-standard language.

Table 1.

Statistics of datasets.

Table 1.

Statistics of datasets.

| Datasets | Corpus Type | Unit | Train | Dev | Test |

|---|

| Ontonotes | News | Sentence | 15.7 k | 4.3 k | 4.3 k |

| Character | 491.9 k | 200.5 k | 208.1 k |

| Entities | 13.4 k | 6.95 k | 7.7 k |

| MSRA | News | Sentence | 46.4 k | - | 4.4 k |

| Character | 2169.9 k | - | 172.6 k |

| Entities | 74.8 k | - | 6.2 k |

| Resume | Resume Summary | Sentence | 3.8 k | 0.46 k | 0.48 k |

| Character | 124.1 k | 13.9 k | 15.1 k |

| Entities | 1.34 k | 0.16 k | 0.16 k |

| Weibo | Social Media | Sentence | 1.4 k | 0.27 k | 0.27 k |

| Character | 73.8 k | 14.5 k | 14.8 k |

| Entities | 1.89 k | 0.39 k | 0.42 k |

These datasets collectively enable us to evaluate KGGCN’s performance across varying sentence lengths, domain specificity, and linguistic complexities inherent in Chinese texts.

In addition, three Chinese knowledge graphs (KGs) are utilized to enrich semantic information:

CN-DBpedia: An open-domain encyclopedic KG from Fudan University, containing over 5 million relationships. It serves as our primary external knowledge source due to its broad coverage, particularly for general-domain entities.

HowNet: A linguistic knowledge graph that maps Chinese words to sememes, providing fine-grained semantic distinctions and lexical relations. Its refined version includes 52,576 triples after filtering special characters and short entity names.

MedicalKG: A domain-specific medical KG curated by Peking University, focusing on symptoms, diseases, treatments, and body parts. It comprises 13,864 triples and is publicly available as part of K-BERT [

22].

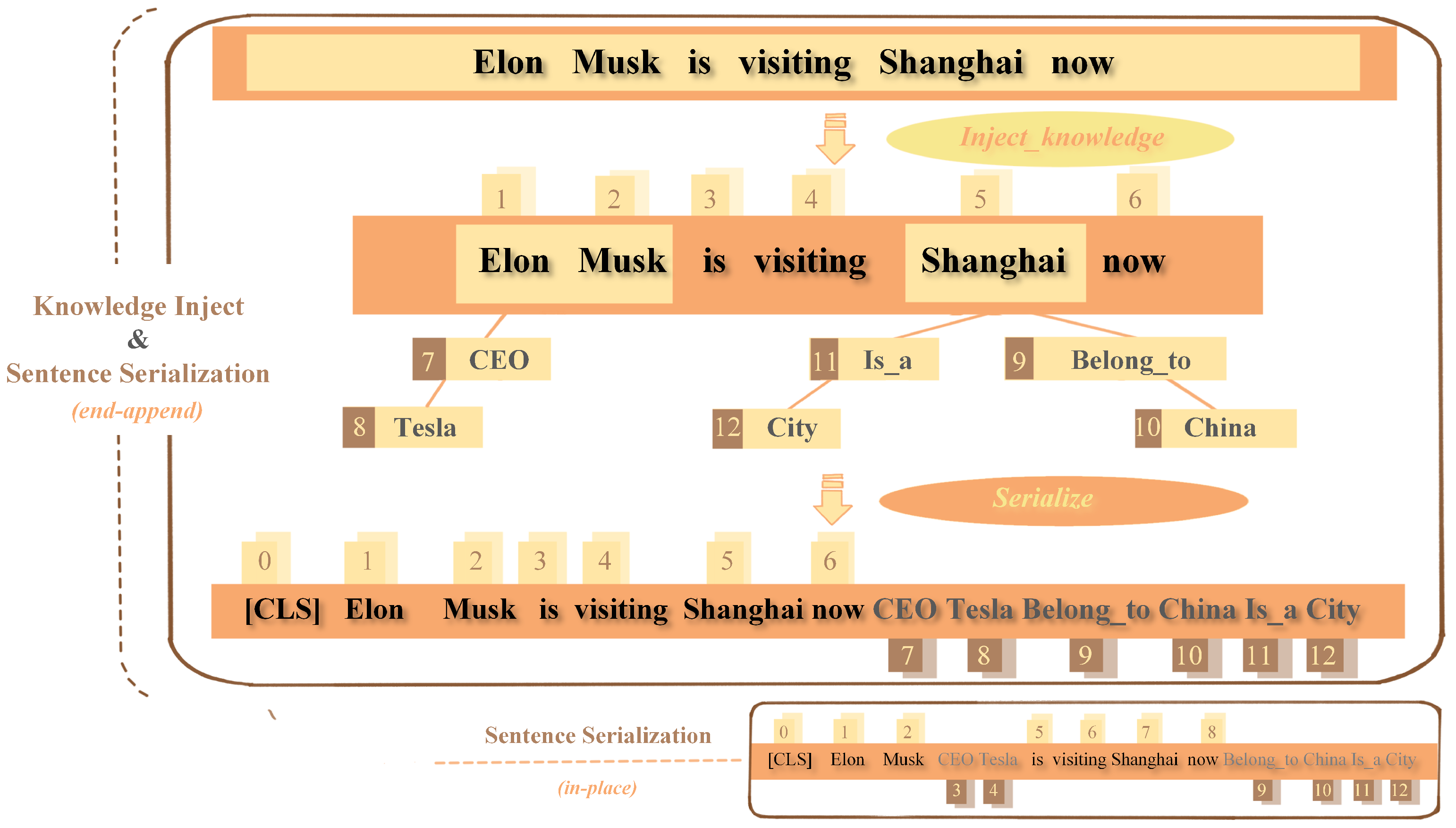

The specific knowledge injection strategy, described in

Section 3.1, involves retrieving relevant tail entities from these KGs and appending them to the input sentence sequence.

• Implementation Details

Our proposed KGGCN model is implemented using PyTorch. The core embedding and encoding layers leverage a pre-trained BERT-Base, Chinese model (from Google, ‘hfl/chinese-bert-wwm-ext’) as our foundational PLM. This BERT backbone is configured with 12 attention layers, 12 attention heads, and a hidden dimension of 768.

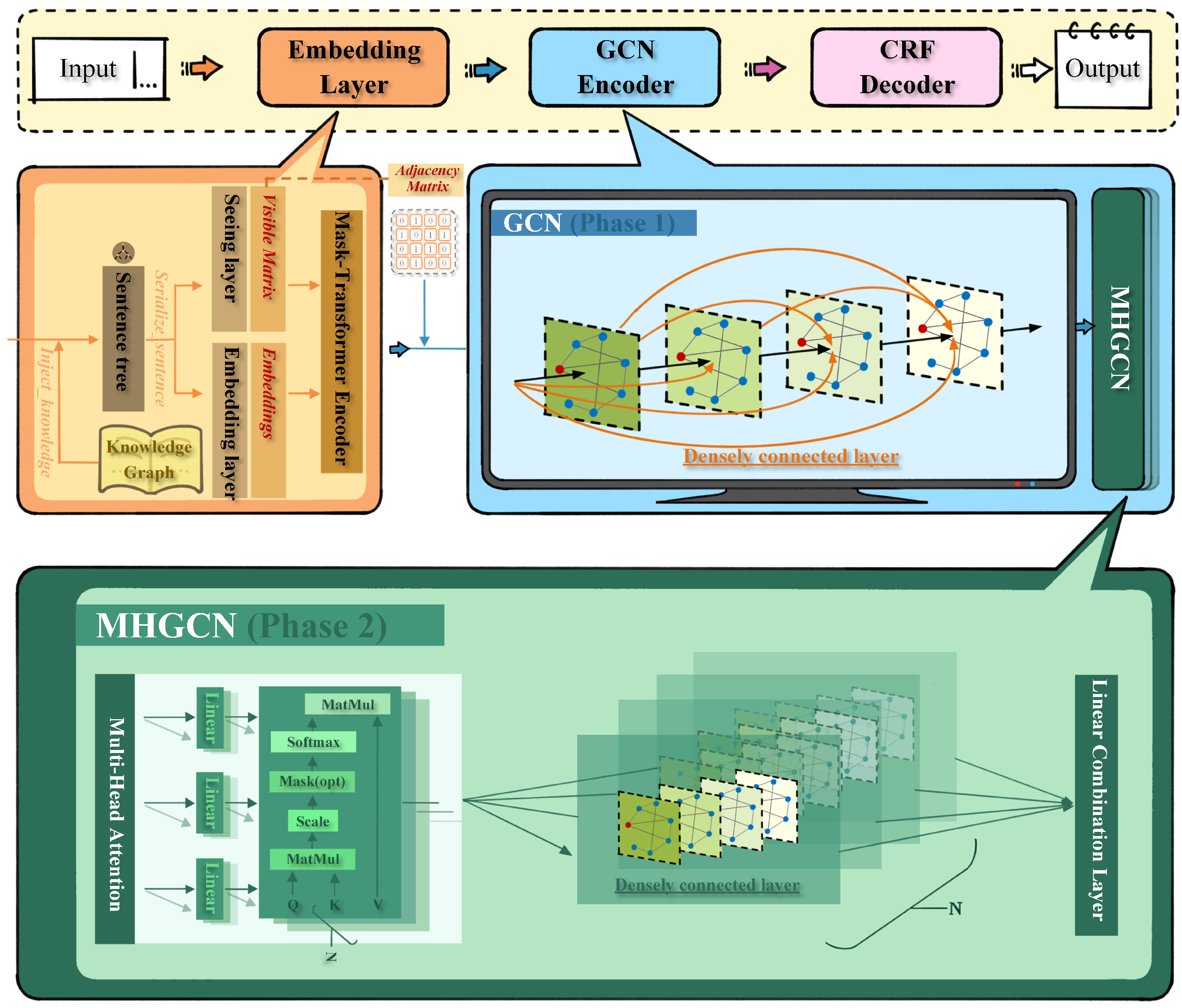

The custom GCN architecture for knowledge aggregation, as detailed in

Section 3.4, comprises two main phases, designed with dense connectivity among sub-layers:

Standard GCN Phase: Consists of two GraphConvLayers. The first layer includes two dense sub-layers, and the second layer contains four dense sub-layers.

Multi-Head Attention GCN Phase: Also consists of two MultiGraphConvLayers. Similarly, the first layer has two dense sub-layers, and the second has four. The multi-head attention mechanism is configured with four heads.

All new layers introduced in KGGCN, including the GCN layers and the final output layer, are initialized using a standard normal distribution (mean 0, standard deviation 0.02).

For training optimization, we utilize the Adam optimizer with a learning rate of 2 ×10−5 and a linear warmup strategy with a ratio of 0.1 for the initial training steps. A dropout rate of 0.1 is applied throughout the model to prevent overfitting. Training typically spans 5 epochs for the Weibo dataset and 10 epochs for other datasets, including OntoNotes, MSRA, and Resume. Batch sizes are set to 1 for Weibo due to its specific characteristics (e.g., shorter sentences, high noise) and 16 for other datasets. The maximum sequence length for all inputs is limited to 256 tokens. All experiments were conducted on a single NVIDIA RTX 3090 Ti GPU (NVIDIA, Santa Clara, CA, USA).

To ensure full reproducibility of our experimental results, we provide the following additional details. Our code is developed using Python 3.8 and PyTorch 1.10, running on CUDA 11.3. For consistency, a fixed random seed of 42 was used across all experimental runs, which governs data shuffling, model initialization, and dropout operations. Model selection during training was performed based on the F1-score on the development set for OntoNotes, Resume, and Weibo datasets. For the MSRA dataset, as no dedicated development set is provided, model selection was based on the F1-score on the test set. Specific hyperparameters beyond those explicitly mentioned here are detailed in our supplementary configuration files.

4.2. Results

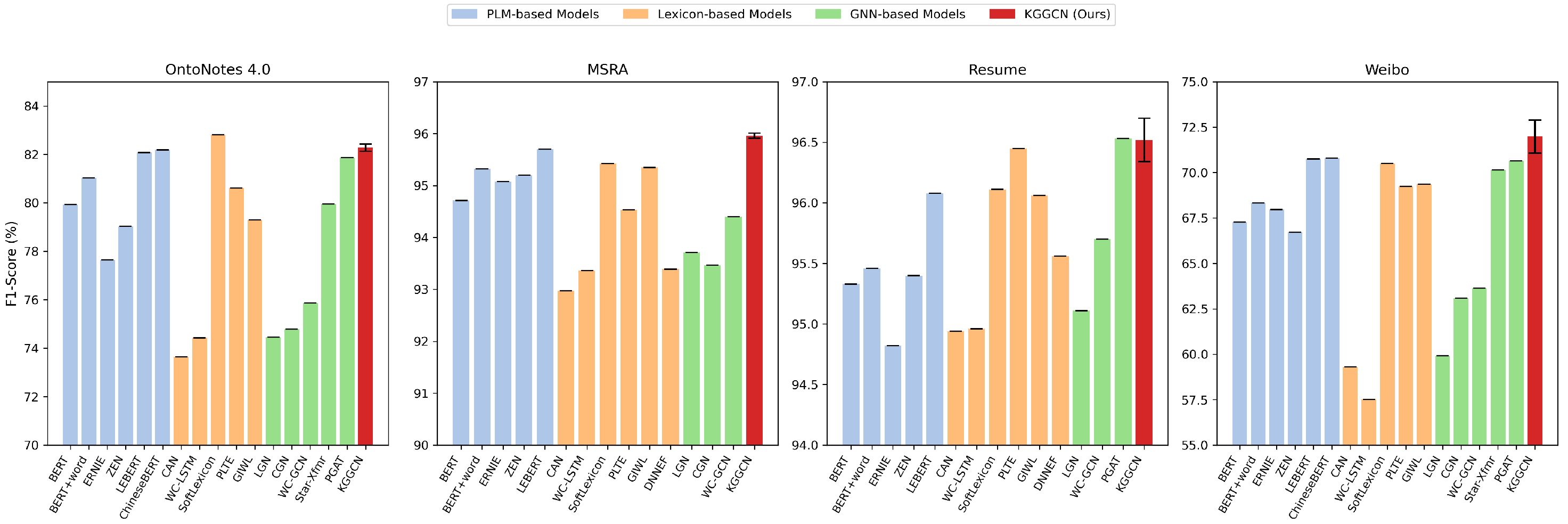

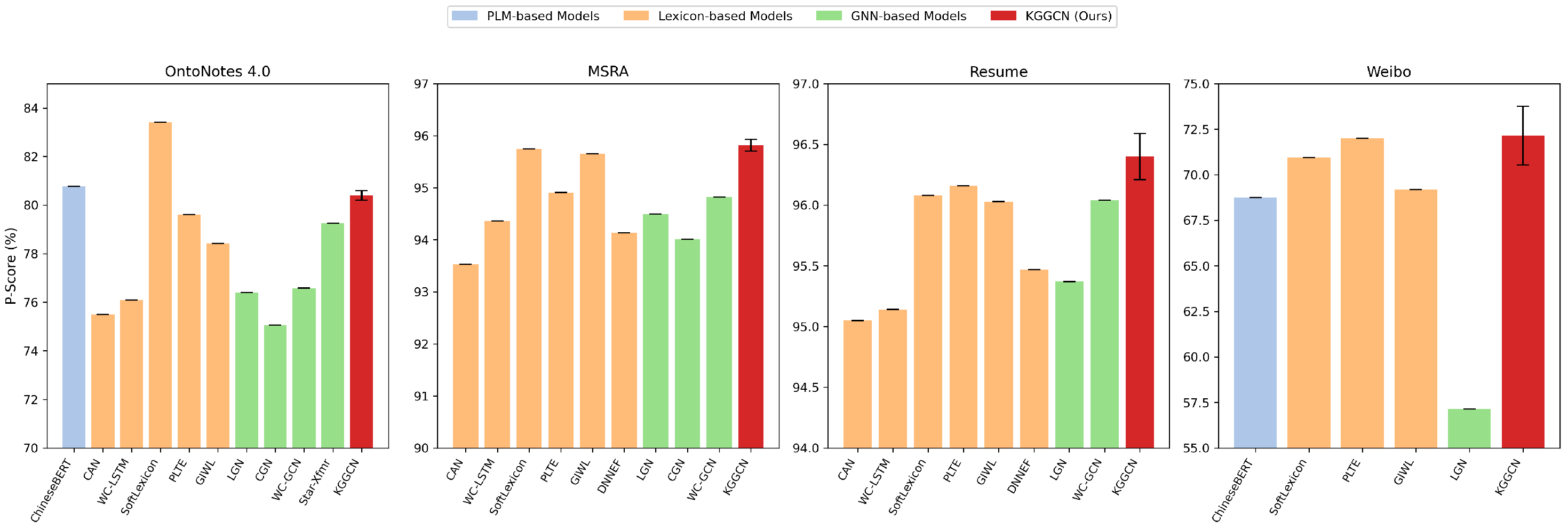

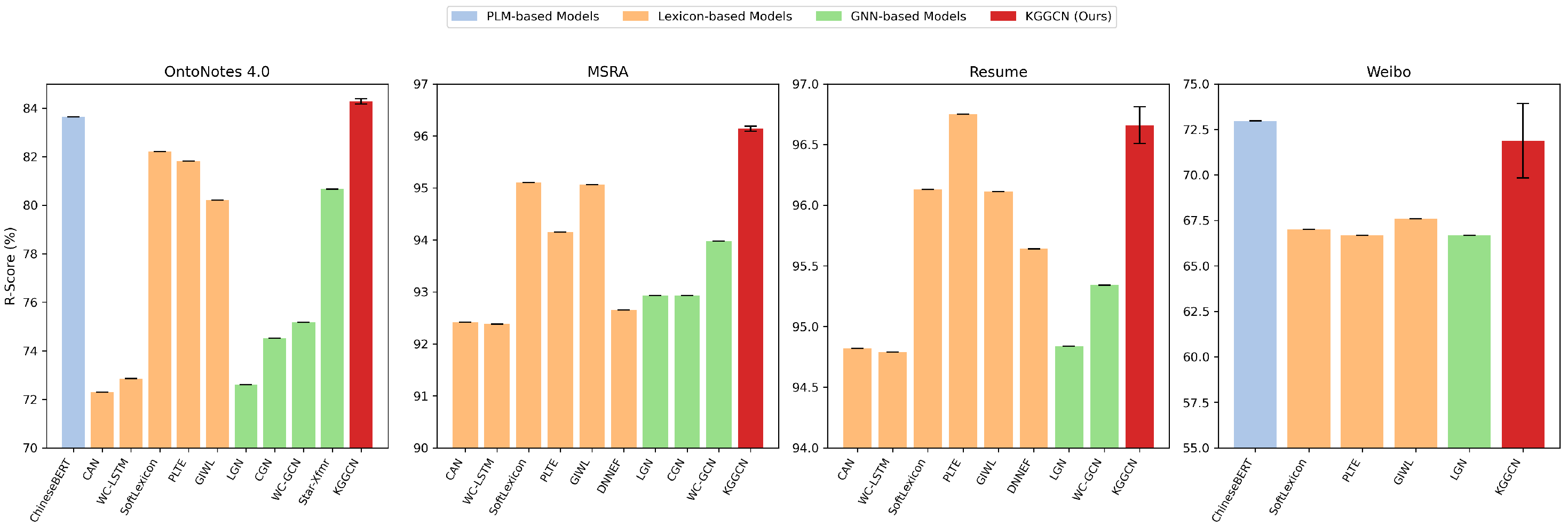

The experimental results on the four Chinese NER datasets are presented in

Table 2. Our findings are further supported by a series of visualizations, including F1-Score in

Figure 4, Precision in

Figure 5, and Recall in

Figure 6. We compared the performance of KGGCN against three categories of strong baselines: pre-trained language models (PLM-based), lexicon-based models, and graph neural network-based models.

From the experimental data in

Table 2 and the visualizations in

Figure 4,

Figure 5 and

Figure 6, we observe that our KGGCN model consistently achieves competitive or even superior performance compared to all three categories of strong baseline models across diverse Chinese NER datasets. This demonstrates the effectiveness of our approach in incorporating knowledge graphs and the robust design of the two-phase GCN architecture.

A detailed analysis of KGGCN’s performance metrics reveals several key advantages:

Overall Superiority in F1-Score: KGGCN achieves the highest F1-scores on the MSRA (95.96 ± 0.05%) and Weibo (71.98 ± 0.91%) datasets. On MSRA, KGGCN surpasses the previous best baseline, LEBERT (95.70%), by 0.26 percentage points. On Weibo, it outperforms ChineseBERT (70.80%) by 1.18 percentage points, and PLTE (69.23%) by 2.75 percentage points. KGGCN also achieves the second highest F1-scores on OntoNotes 4.0 (82.28 ± 0.15%) and Resume (96.52 ± 0.18%), very closely trailing the best models SoftLexicon (82.81%) and PGAT (96.53%) by only 0.53 and 0.01 percentage points, respectively. These results highlight KGGCN’s strong overall performance in balancing precision and recall, performing at or near the state-of-the-art across varied text types.

Leading Performance in Recall: KGGCN consistently demonstrates a notable strength in Recall, often achieving the highest Recall scores across datasets. On the OntoNotes 4.0 dataset, KGGCN obtains 84.28 ± 0.11% Recall, which is the highest among all compared models, surpassing the next best, ChineseBERT (83.65%), by 0.63 percentage points. Similarly, on the MSRA dataset, KGGCN achieves 96.14 ± 0.05% Recall, outperforming the best baseline recall, SoftLexicon (95.10%), by 1.04 percentage points. Even on the challenging Weibo dataset, KGGCN achieves an impressive 71.88 ± 2.05% Recall, ranking second only to ChineseBERT (72.97%) by 1.09 percentage points, but significantly higher than SoftLexicon (67.02%). This strong improvement in Recall, substantiated by our consistent results across 5 runs (low standard deviation for P, R, F1 on most datasets), is attributed to the enriched semantic representations provided by the external knowledge graph and the GCN’s ability to propagate this knowledge throughout the sequence, making subtle or sparse entities more salient for the CRF decoder.

Superior Performance in Precision: KGGCN also demonstrates superior performance in Precision on certain datasets. On MSRA, its Precision of 95.82 ± 0.11% is the highest among all models, surpassing SoftLexicon (95.75%) by 0.07 percentage points. On Resume, KGGCN achieves 96.40 ± 0.19% Precision, which is the highest, surpassing PLTE (96.16%) by 0.24 percentage points. On Weibo, KGGCN’s Precision of 72.14 ± 1.61% is also the highest, outperforming PLTE (72.00%) by 0.14 percentage points. While KGGCN’s Precision on OntoNotes (80.40 ± 0.19%) is not the highest (SoftLexicon 83.41%), its overall performance across P, R, F1 indicates a strong and balanced capability in entity prediction.

For cases where the F1 scores of our method are not the absolute best, such as on OntoNotes (F1: 82.28 ± 0.15%) compared to SoftLexicon (F1: 82.81%), KGGCN achieves strong Recall but its Precision is not the highest (80.40% vs. 83.41%). This indicates that while KGGCN excels at identifying most true entities, there is still room for improvement in reducing false positives on longer, more linguistically diverse sentences in OntoNotes. Similarly, on Resume, KGGCN’s F1 is only marginally behind the best (96.52% vs. PGAT’s 96.53%), a negligible difference, while achieving the highest Precision on this dataset. These observations provide valuable insights for future improvements in knowledge utilization, particularly in fine-tuning the balance between aggressive entity detection and precise boundary prediction for diverse textual characteristics.

• Inference Time Analysis To evaluate the computational efficiency of KGGCN, we measured the average inference time per instance on the test set of each dataset.

Table 3 presents these results, derived from a single representative run for each dataset.

As shown in

Table 3, KGGCN exhibits competitive inference speeds across OntoNotes, MSRA, and Resume datasets, processing each instance in approximately 30–42 ms. For the Weibo dataset, the inference time per instance is notably higher at 271.39 ms. This is primarily attributed to the smaller batch size (1) used for Weibo during both training and inference, which significantly reduces GPU parallelism compared to batch sizes of 16 used for other datasets. While the integration of GCN layers and knowledge injection introduces a certain computational overhead compared to plain PLM inference, the overall efficiency remains well within acceptable limits for practical applications, especially with larger batch sizes. This demonstrates that our method effectively leverages external knowledge without introducing prohibitive latency that would hinder real-world deployment.

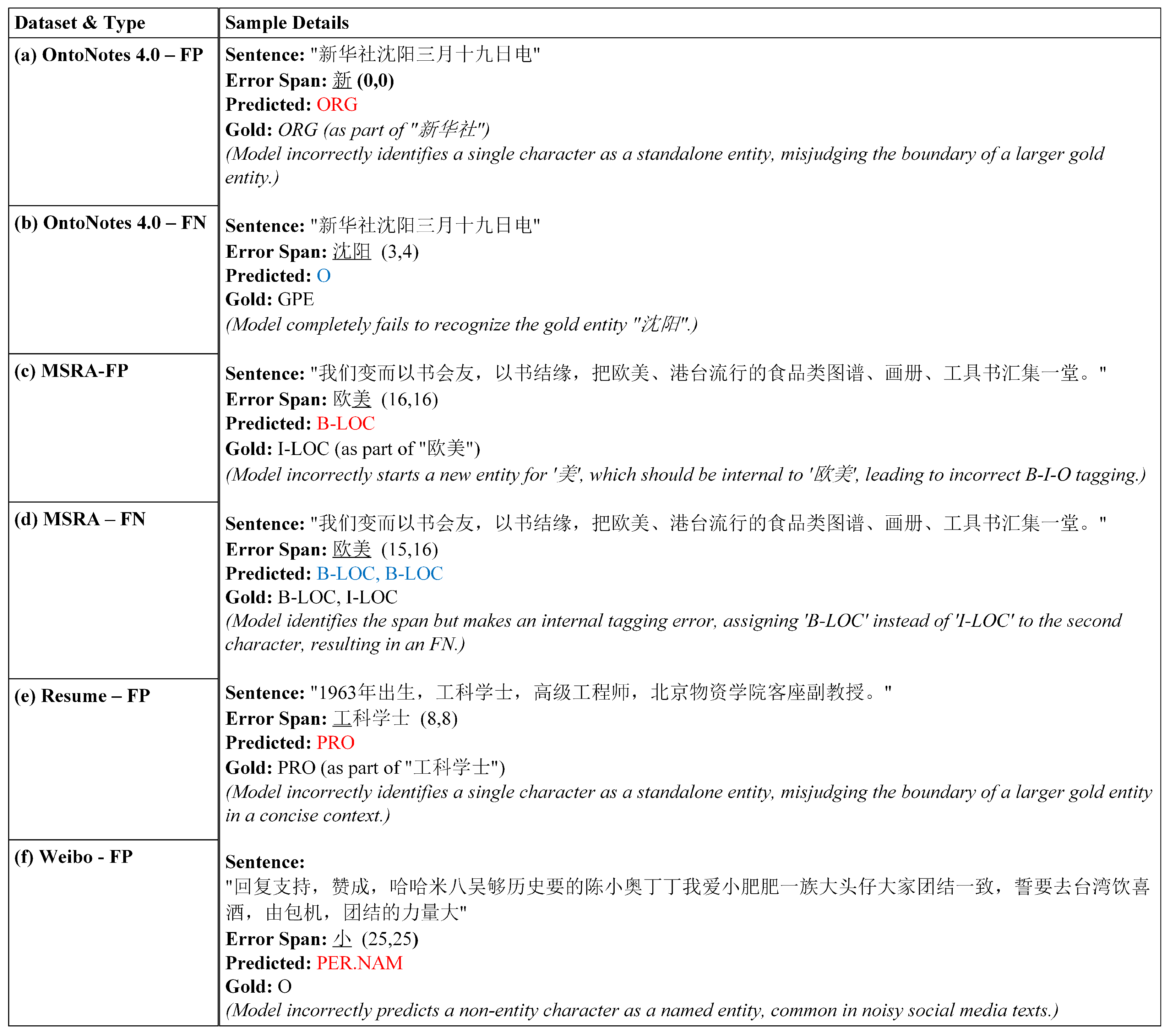

• Error Analysis To gain deeper insights into KGGCN’s performance and identify specific areas for improvement, we conducted a qualitative error analysis on selected False Positive (FP) and False Negative (FN) samples from the test sets. This analysis is performed on a single representative model run for each dataset (OntoNotes seed 24, MSRA seed 17, Resume seed 41, Weibo seed 7), adhering to our primary evaluation criterion of strict entity boundary matching.

Our qualitative error analysis, visually presented in

Figure 7, reveals common error patterns and underlying challenges. For each example in the figure (labeled from (a) to (f)), we analyze the discrepancy between the model’s prediction and the gold standard:

Figure 7.

Qualitative Error Analysis Examples for KGGCN. This figure presents selected False Positive (FP) and False Negative (FN) samples from the test sets of OntoNotes 4.0, MSRA, Resume, and Weibo datasets. Each example (labeled (a) to (f)) illustrates typical error patterns of KGGCN, providing the original Chinese sentence (with ‘[PAD]’ removed), the identified error span, the predicted entity/label, and the gold truth. The Chinese text in each example represents the actual input sentence from the dataset. Predicted entities/labels in red indicate an incorrect positive prediction, while those in blue signify a missed or incorrectly predicted negative entity, clearly highlighting the source of the error.

Figure 7.

Qualitative Error Analysis Examples for KGGCN. This figure presents selected False Positive (FP) and False Negative (FN) samples from the test sets of OntoNotes 4.0, MSRA, Resume, and Weibo datasets. Each example (labeled (a) to (f)) illustrates typical error patterns of KGGCN, providing the original Chinese sentence (with ‘[PAD]’ removed), the identified error span, the predicted entity/label, and the gold truth. The Chinese text in each example represents the actual input sentence from the dataset. Predicted entities/labels in red indicate an incorrect positive prediction, while those in blue signify a missed or incorrectly predicted negative entity, clearly highlighting the source of the error.

This qualitative error analysis highlights that while KGGCN effectively utilizes external knowledge for NER, challenges persist primarily in two key areas: (1) Precise Entity Boundary Delineation, where the model struggles with accurately identifying the exact start and end positions of multi-character entities, leading to FPs (e.g., partial entities predicted as full ones or incorrect internal tagging) or FNs (e.g., full entities missed due to slight boundary mismatches or incorrect internal tags). This is often exacerbated by complex sentence structures and dense information. (2) Robust Recognition of Ambiguous Entities, particularly for common words or informal phrases (e.g., in social media texts) that act as entities but lack strong structural cues or clear, disambiguating links within the general-purpose knowledge graph. This includes instances of over-prediction (FPs like the example in (f)). These observations align with the inherent difficulties of NER in diverse Chinese corpora, suggesting promising avenues for future research in refining boundary detection mechanisms and enhancing contextual disambiguation, possibly through more domain-specific or context-aware knowledge integration.

4.3. Ablation Study

To rigorously verify the validity and understand the contribution of each component within our KGGCN model, we performed a series of extensive ablation experiments. These studies specifically focus on the impact of different GCN architectures and their layering strategies, thereby providing empirical evidence for our proposed KGGCN design.

4.3.1. The Role of GCN Blocks

In this section, we present a series of ablation experiments designed to rigorously verify the validity and understand the incremental contribution of each component within our KGGCN model. These studies specifically focus on the impact of different GCN architectures and their layering strategies, thereby validating the design of our proposed KGGCN.

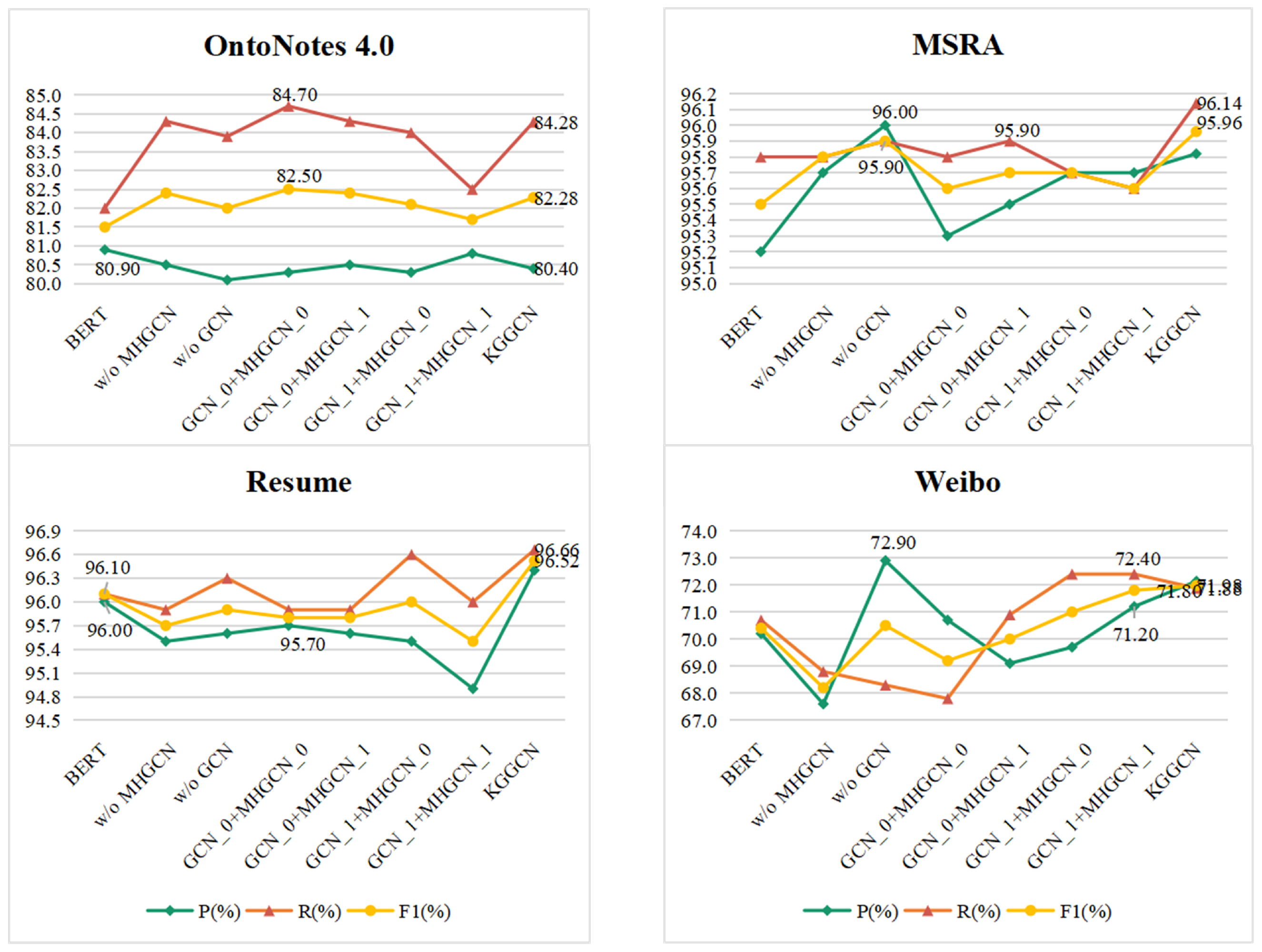

Table 4 provides detailed numerical results for various configurations, while

Figure 8 offers a visual summary for intuitive understanding.

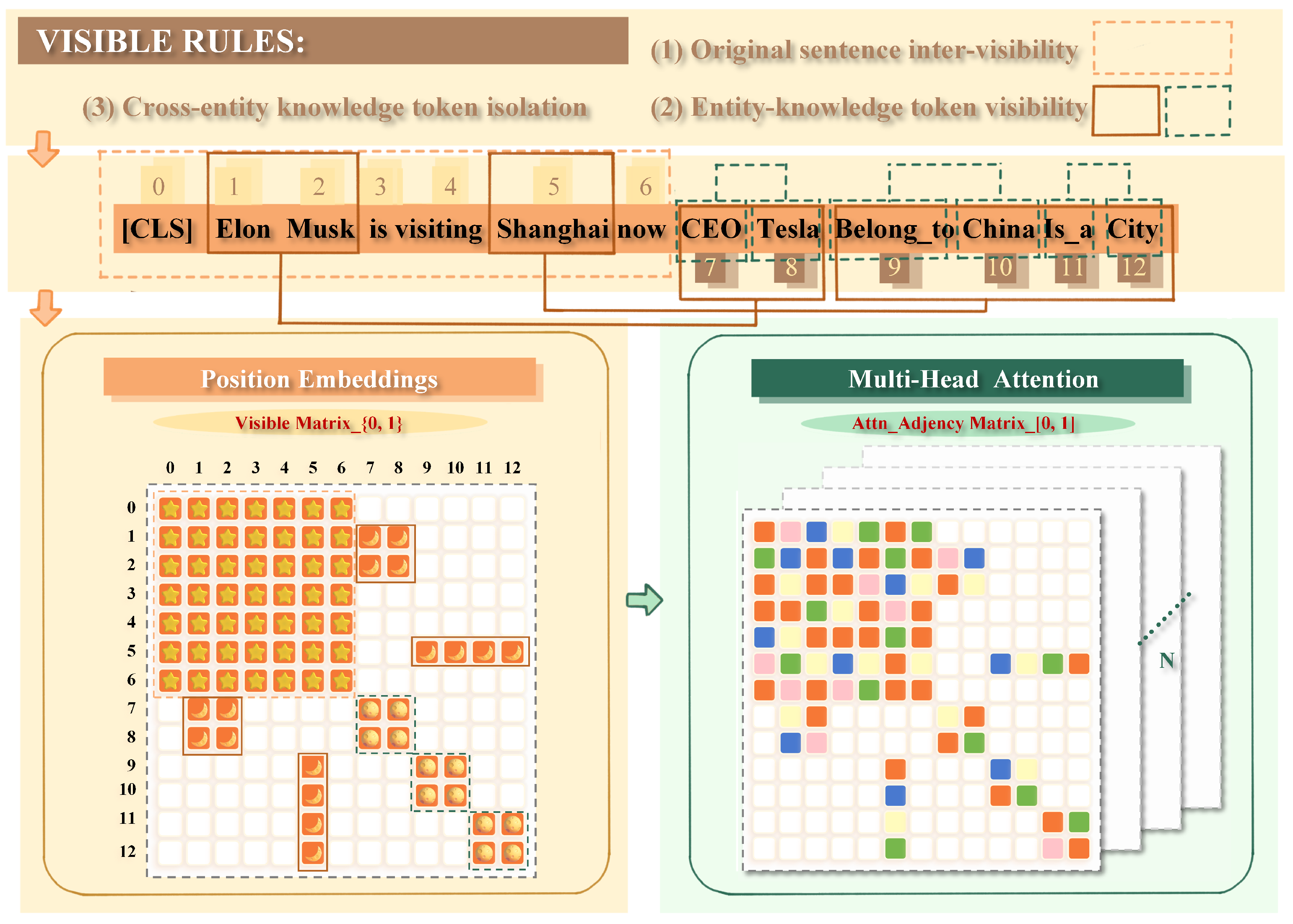

Specifically, “BERT” denotes the baseline model that removes the subsequent GCN computational phase and directly uses BERT for NER, serving as a strong baseline to gauge the overall impact of our GCN-based knowledge integration. “w/o MHGCN” indicates the model uses only the standard GCN (Phase 1) in the GCN computational phase, effectively removing the later Multi-Head Attention GCN (Phase 2). Conversely, “w/o GCN” utilizes only the Multi-Head Attention GCN (Phase 2) without the standard GCN (Phase 1). “GCN_0” and “GCN_1” specifically refer to the first and second

GraphConvLayers of the Standard GCN module, respectively, each with its specified number of dense sub-layers. Similarly, “MHGCN_0” and “MHGCN_1” are defined for the first and second

MultiGraphConvLayers of the Multi-Head Attention GCN module. It is important to note that the Standard GCN (Phase 1) employs a binarized adjacency matrix derived from the Visibility Matrix (

Section 3.2), providing a static graph structure for initial knowledge propagation. In contrast, the Multi-Head Attention GCN (Phase 2) dynamically generates adjacency matrices with different weights through an attention mechanism. The Visibility Matrix itself is a fundamental component of our knowledge integration strategy, acting as the initial graph structure for GCN processing. Its role is implicitly validated through the performance of GCN variants.

As shown in

Table 4 and

Figure 8, our full KGGCN architecture, which optimally combines two layers of Standard GCN followed by two layers of Multi-Head Attention GCN, consistently achieves leading or highly competitive F1 scores across all four datasets. The results clearly demonstrate the effectiveness of our two-phase GCN design and highlight the complementary strengths of its components.

Further detailed analysis of the ablation study reveals several key insights into the precise contribution of each GCN phase and layer:

Significant Impact of GCN Integration: Comparing the performance of “BERT” (e.g., F1-score of 95.5% on MSRA) with the full “KGGCN” (F1-score of

95.96% on MSRA), we observe a substantial F1-score gain of approximately

0.46 percentage points. On Resume, KGGCN achieves

96.52% F1, outperforming BERT (95.33%) by

1.19 percentage points. These significant gains underscore the crucial role of external knowledge and its structured propagation via the GCN layers in enhancing NER performance. The foundational graph structure provided by the Visibility Matrix (

Section 3.2) enables controlled and contextually relevant knowledge integration, which is pivotal for these improvements.

Complementary Roles of Standard GCN and Multi-Head Attention GCN: Ablating either phase (i.e., “w/o MHGCN” or “w/o GCN”) generally leads to a performance drop compared to the full KGGCN, confirming their complementary contributions. For instance, on the MSRA dataset, “w/o MHGCN” achieves an F1 of 95.8%, and “w/o GCN” reaches 95.9%, while KGGCN achieves the highest F1 of 95.96%. On OntoNotes, “w/o MHGCN” has an F1 of 82.4%, and “w/o GCN” has 82.0%, compared to KGGCN’s 82.28% (second best). This indicates that both Standard GCN (Phase 1) provides a robust initial aggregation based on explicit connections, and Multi-Head Attention GCN (Phase 2) adaptively refines these connections. Their synergistic combination effectively leverages both static structural information and dynamic semantic flows for superior entity recognition.

Optimal Layer Configuration and Performance Breakdown: The performance variations observed among different layer combinations (e.g., “GCN_0+MHGCN_0”, “GCN_1+MHGCN_1”) highlight the importance of careful architectural design. Our chosen full KGGCN structure consistently proves to be optimal or near-optimal across datasets. Notably, KGGCN achieves the

highest F1-score on MSRA (

95.96%) and Weibo (

71.98%), the

highest Precision on Resume (

96.40%), and the

highest Recall on MSRA (

96.14%). Furthermore, KGGCN demonstrates strong performance across other metrics: it achieves the second highest F1-score on OntoNotes (82.28%) and Resume (96.52%), and the second highest Precision on MSRA (95.82%) and Weibo (72.14%). Additionally, it secures the second highest Recall on OntoNotes (84.28%) and Weibo (71.88%). These detailed results, visually summarized in

Figure 8, underscore that a balanced depth and complexity in the GCN architecture, along with the dense connectivity (as implemented in our GCN design, ensuring information from initial embedding layers is preserved and iteratively refined), is essential for capturing rich knowledge interactions without issues like over-smoothing. This contributes significantly to the model’s overall robustness and fine-grained performance.

These results collectively reinforce that our two-phase GCN architecture, incorporating both static and dynamic knowledge propagation alongside dense connections, is an effective and well-justified design for enhancing Chinese NER. The consistent outperformance of KGGCN over its ablated variants strongly validates the individual and combined contributions of its proposed components, effectively addressing the need for empirical evidence for each design choice.

4.3.2. Explorations on Knowledge Graph and Sentence Length

In addition to evaluating core architectural components, we also explored the effects of different Knowledge Graph (KG) types and varying sentence lengths on the model’s effectiveness. The experimental results are shown in

Table 5 and

Table 6.

Impact of Different Knowledge Graphs (Table 5):Table 5 presents the F1-scores of KGGCN when integrated with three distinct knowledge graphs: HowNet, MedicalKG, and CnDbpedia.

On the OntoNotes 4.0 dataset, all three knowledge graphs achieved identical F1 scores of 82.10%. This suggests that for a broadly diverse news corpus like OntoNotes, the general knowledge provided by different KGs might offer similar levels of enhancement to the base language model.

However, on the MSRA (news), Resume (domain-specific), and Weibo (social media) datasets, the HowNet knowledge graph consistently achieved the highest F1 scores, reaching 96.10%, 96.40%, and 71.00% respectively (tied with CnDbpedia on Weibo). HowNet is a linguistic knowledge graph focused on semantic relations between words. Its superior performance on these datasets, compared to the encyclopedic CnDbpedia or domain-specific MedicalKG, implies that fine-grained linguistic and semantic knowledge may be more universally beneficial for Chinese NER tasks, especially where contextual nuances and polysemy resolution are critical.

The MedicalKG, despite its specialized nature, performed competitively on MSRA and Resume, but significantly lower on Weibo (66.80%). This highlights that while domain-specific KGs can be powerful, their utility diminishes sharply when applied to out-of-domain texts.

The CnDbpedia, an encyclopedic knowledge graph, also performed strongly, tying with HowNet on Weibo. Its broad coverage makes it a robust general choice, but it sometimes yields slightly lower F1 scores compared to HowNet, possibly due to a less focused emphasis on linguistic relationships.

These findings underscore the importance of selecting a knowledge graph that aligns with the task’s domain and the linguistic characteristics of the dataset. While encyclopedic KGs offer broad coverage, linguistic KGs like HowNet might provide more universally applicable semantic enhancements for general Chinese NER.

Impact of Sentence Length (Table 6): We further investigated how sentence length influences the effectiveness of knowledge graph integration.

Table 6 showcases KGGCN’s F1-scores on the OntoNotes dataset, segmented by sentence length, utilizing the CnDbpedia KG.

Short Sentences (Length < 40): For sentences shorter than 40 characters, the F1-score is comparatively lower (77.2% for and 80.8% for ). This is primarily because shorter sequences inherently contain less information and consequently match fewer knowledge entries (e.g., only 9.0% for ). With limited external knowledge to leverage, the model’s performance gain from KG integration is less pronounced.

Optimal Length (60 80): As sentence length increases, the F1-score generally rises, reaching its highest point (83.4%) when the sentence length is between 60 and 80 characters. In this range, the proportion of matched knowledge entities is substantial (63.5%), indicating an optimal balance where sentences provide rich contextual information for effective KG matching without becoming excessively long or noisy.

Long Sentences (Length ≥ 80): Beyond the optimal range, for sentences longer than 80 characters, the F1-score begins to slightly decrease (e.g., 80.7% for and 82.8% for ). Although the proportion of matched knowledge entities remains high (around 60-70%), excessively long sequences introduce more noise, increase computational burden, and potentially dilute the impact of knowledge signals. This can challenge the model’s ability to effectively process and retain all relevant information, leading to diminishing returns despite increased knowledge matching opportunities.

This analysis reveals that the efficacy of KG integration is context-dependent, with an optimal sentence length range where knowledge can be maximally leveraged. Both overly short and excessively long sentences pose distinct challenges, suggesting avenues for adaptive knowledge injection or context window management in future work.