Abstract

Smart devices are used in the era of the Internet of Things (IoT) to provide efficient and reliable access to services. IoT technology can recognize comprehensive information, reliably deliver information, and intelligently process that information. Modern industrial systems have become increasingly dependent on data networks, control systems, and sensors. The number of IoT devices and the protocols they use has increased, which has led to an increase in attacks. Global operations can be disrupted, and substantial economic losses can be incurred due to these attacks. Cyberattacks have been detected using various techniques, such as deep learning and machine learning. In this paper, we propose an ensemble staking method to effectively reveal cyberattacks in the IoT with high performance. Experiments were conducted on three different datasets: credit card, NSL-KDD, and UNSW datasets. The proposed stacked ensemble classifier outperformed the individual base model classifiers.

Keywords:

Internet of Things (IoT); fraud; cyberattack; machine learning; deep learning; ensemble; stacking 1. Introduction

Technology has become an integral part of our lives. Our reliance on technology, especially the Internet, is becoming more critical with the rapid advancements that make technology and the Internet interfere in every aspect of our lives, and this increased the attention toward Internet-based technologies, especially the Internet of Things (IoT). The IoT allows connected devices to communicate and interact for a specific purpose without the need for human intervention [1]. These devices include a variety of properties and qualities that facilitate machine-to-machine interactions, paving the way for a wide range of applications and technologies to arise [2]. Because of its ability to make people’s lives easier, give better experiences for customers and organizations, and improve job autonomy, the Internet of Things has become a hot topic in the last decade. Despite all of these advantages, the IoT is challenged with several constraints and barriers that could hinder its power to reach its full potential. User security and privacy are not fully considered when designing most IoT apps, which is a significant problem, according to the authors of [3]. There are two types of attacks in IoT systems: passive and active. Passive attacks do not interfere with information and are used to extract sensitive data without being identified. Active attacks target systems and carry out malicious acts that compromise the system’s privacy and integrity.

Since IoT nodes and devices are expected to support most payments, fraud attacks are among the most common. Financial fraud has become a severe problem with the rapid growth of e-commerce transactions and the development of IoT applications. According to the authors of [4], 87 percent of businesses and merchants allow electronic payments. This percentage will rise with mobile wallets and the ability of IoT devices to conduct payments, making systems more vulnerable to fraud attacks. Fraud in electronic payments can occur in several ways, but unauthorized access to a certification number or credit card information is the most common. Fraud involving credit card access can either occur physically by stealing the card and using it to make fraudulent purchases or by virtually accessing the card or payment information and making fraudulent transactions. Virtual credit card fraud is most common in IoT environments, where attacks do not require the card to be physically present. Attackers are constantly looking for new ways to gain information such as verification codes, card numbers, and expiration dates to conduct fraudulent transactions, mandating the development of systems and models that can detect and prevent fraud.

The problem of cyber and fraud attacks can lead to immeasurable damages. More than 22 billion IoT devices are expected to be connected to the Internet in the next few years, making it critical to find ways and develop models to provide secure and safe IoT services to customers and businesses [5]. Thus, various machine learning and deep learning models have been introduced to detect fraud and malicious attacks. Some models use ensemble learning, which combines multiple classifiers in aggregate to provide better overall performance compared with the used baseline models. Existing solutions were analyzed, and the main limitations found were the lack of validation of the proposed solutions and the uncertainty in generalization of the new data. Hence, this paper presents a novel stacked ensemble model that uses several machine learning models to detect different cyberattacks and fraud attacks efficiently. In our stacked ensemble approach, we tested multiple machine learning algorithms and used the best-performing as well as the worst-performing models to examine the improvement in performance when integrating the baseline models in our stacked ensemble algorithm. Our method combines different algorithms’ strong points and skills in a single robust model. In this way, we ensure that we have the best combination of models to approach the problem and improve generalization when making detections. We used three datasets to validate our ensemble algorithm. The experimental results for the Credit Card Fraud Detection, NSL-KDD, and UNSW datasets show that the proposed stacked ensemble classifier enhanced generalization and outperformed similar works in the literature.

2. Related Work

2.1. IoT Layers

Developing an IoT architecture, a framework for various hardware services, makes it possible to create a link and provide IoT services everywhere. There are primarily three layers in IoT architecture: perception, application, and network [6,7].

2.1.1. Perception or Physical Layer

The IoT architecture begins with a physical layer and a medium-access control layer, forming the perception layer [8]. The physical layer mainly deals with hardware, sensors, and devices that share and exchange data using various communication protocols, such as RFID, Zigbee, or Bluetooth. Physical devices are linked to networks in the MAC layer to enable communication [9].

2.1.2. Network Layer

IoT systems rely on the networking layer to transmit and redirect data and information through various transmission protocols. Local clouds and servers store and process information in the network layer and between the network layer and the next layer [10].

2.1.3. Application or Web Layer

The third layer of IoT systems is where users receive services through mobile and web applications. Considering the recent trends and uses of intelligent things, the Internet of Things has numerous applications in today’s technologically advanced world. Thanks to the IoT and its infinite applications, living spaces, homes, buildings, transportation, health, education, agriculture, business, trade, and even energy distribution have become more intelligent [7].

2.2. Classification of Attacks

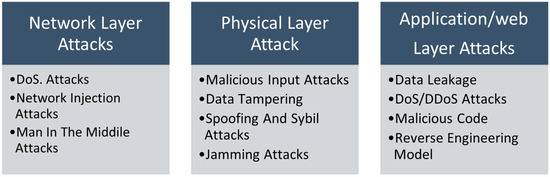

Cyberattacks and physical attacks are the two main categories of IoT security threats. In a cyberattack, hackers manipulate the system to steal, delete, alter, or destroy information from the users of IoT devices. On the other hand, a physical attack damages IoT devices physically [11]. In the following subsections, various types of cyberattacks are discussed in the three primary layers of the IoT [12,13,14]. Some common IoT attacks at different layers are shown in Figure 1:

Figure 1.

Cyberattack classification based on IoT layers.

- DoS attack: Denial of Service attacks (DoS attacks) disrupt system services by creating multiple redundant requests. DoS attacks are common in IoT applications. Many of the devices used in the IoT world are low-end, leaving them vulnerable to attacks [15].

- Jamming attacks: Jamming attacks interfere with communication channels and are a subset of DoS attacks. Wireless communication is disrupted by incoming signals, causing the network to be overloaded and affecting the users [16,17].

- Network injection: Hackers can use this attack to create their device, which acts as a sender of IoT data and sends data like it is part of the IoT network [13].

- Man in the middle attacks: In this scenario, attackers are trying to be a part of the communication system, where the attack is directly connected to another device [16]. IoT network nodes are all connected to the gateway for communication. All devices which receive and transmit data will be compromised if the server is attacked [17].

- Malicious input attacks: In this case, an attacker can inject malicious scripts into an application and make them available to all users. Any input type may be stored in a database, a user forum, or any other mechanism that stores input. Malicious input attacks lead to financial loss, increased power consumption, and the degradation of wireless networks [18].

- Data tampering: Physical access to an IoT device is required for an attacker to gain full control. This involves physically damaging or replacing a node within the device. The attackers manipulate the information of the user to disrupt their privacy. Smart devices that carry information about the location of the user, fitness levels, billing prices, and other essential details are vulnerable to these data tampering attacks [19].

- Spoofing and Sybil attacks: The primary purpose of spoofing and Sybil attacks in IoT systems is to identify users and access the system illegally. We find that TCP/IP cannot provide a strong security protocol, making IoT devices particularly vulnerable to spoofing attacks [20,21].

- Data leakage: Devices connected to the Internet carry confidential and sensitive information. If the data are leaked, the information could be misused. When an attacker is aware of an application’s vulnerabilities, the risk of data stalling increases [22].

- Malicious code: Malicious code can be uploaded if the attacker knows a vulnerability in the application, such as SQL injection or fake data injection. Code that causes undesired effects, security breaches, or damage to an operating system is maliciously inserted into a software system or web script [23].

- Reverse engineering model: An attacker can obtain sensitive information by reverse engineering embedded systems. Cybercriminals use this method to discover data left behind by software engineers, like hardcoded credentials and bugs. The attackers use the information once they have recovered it to launch future attacks against embedded systems [22].

2.3. Cyberattack Detection in IoT Systems

This section discusses several machine learning and deep learning methods as potential solutions to detect cyberattacks for IoT applications. Table 1 and Table 2 provide an overview of the machine learning and deep learning techniques used in the IoT to detect cyberattacks, respectively.

Table 1.

A summary of machine learning methods for cyberattack detection.

Table 2.

A summary of deep learning methods of cyberattack detection.

Anthi et al. [24] developed a three-layer intrusion detection system (IDS) for smart homes using supervised learning. The model detects malicious packets through collaboration among the three layers in the proposed IDS architecture. To secure healthcare data, Al Zubi et al. proposed the cognitive machine learning-assisted attack detection framework (CML-ADF) [25]. They used Extreme Machine Learning (EML) as the detection model to improve the accuracy, attack prediction, and efficiency compared with other existing methods. Another study [26] proposed an attack and anomaly detection system to detect cybersecurity attacks in IoT-based smart city applications. Another study proposed an attack detection framework for recommender systems by developing a probabilistic representation of latent variables for presenting multi-model data [23]. Comparing the proposed framework against the current models showed its superiority in detecting anomalies in recommender systems. One study introduced a linear classification incremental algorithm to classify cyberattacks from multiple sources with high accuracy and low cost. In [27], the authors used an incremental piecewise linear classifier on a multisource set of real-world cyber security data to identify cyberattacks and their sources. Cristiani et al. presented an intrusion detection system called the Fuzzy Intrusion Detection System for IoT Networks (FROST) for preventing and identifying various types of cyberattacks. Despite this, incorrect classification rates were high and needed to be improved [28]. On the other hand, Rathore et al. [29] introduced a new detection mechanism with an ELF-Based Fuzzy C-Means (ESFCM) algorithm that utilized the fog computing paradigm. This method can detect cyberattacks at the network edge and tackles the issues of distribution, scalability, and low latency. In another study, Jahromi et al. [30] offered a two-level ensemble assault detection and attribution framework for industrial control systems. The first level uses deep representational learning to detect imbalances in the control system, whereas the second level uses DNNs to assign the observed attacks. Singh et al. [31] created a Multi-Classifier Intrusion Detection System (MCIDS) based on a deep learning algorithm to detect reconnaissance, analysis, DoS, fuzzers, generic, worms, and shellcode attacks with great accuracy. Battista et al. [32] solved the problem of tampering data in communication networks compromising cyber-physical systems. They used a novel method to protect the control system by coding the output matrices using Fibonacci p-sequences and a key-based numeric sequence to construct a secret pattern. In another study, Diro et al. [33] suggested using a deep learning algorithm to uncover hidden patterns in incoming data to prevent assaults in the social Internet of Things. They believe this model is more accurate at detecting attacks than traditional ML models. Moussa et al. [34] identified cyber assaults during data transfer between the cloud and end user dew devices in the automotive industry. To accurately determine the described assaults, they employed a modified version of a stacked autoencoder. In another article, Soe et al. [35] created a lightweight intrusion detection system (IDS) based on the logistic model tree (LMT), random forest (RF) classifiers, J48, and the Hoe ding tree (VFDT). They devised a novel technique known as correlated-set thresholding on gain ratio (CST-GR), which employs just the features required for each cyberattack. Lastly, Al-Haija et al. [36] created a machine learning-based detection and classification system called the IoT-Based Intrusion Detection and Classification System using a Convolutional Neural Network (IoT-IDCS-CNN). Feature engineering, feature learning, and traffic categorization are the three subsystems that make up the developed algorithm.

2.4. Fraud Attack Detection in IoT Systems

Mishra et al. [37] introduced a k-fold-based logistic regression technique for fraud prevention and detection in IoT environments. Before implementing the logistic regression algorithm, multiple folds of bank transactions are created using the k-fold method. The authors in [38] presented an approach for anomaly detection in IoT economic environments. The model detects malicious activities like Remote-to-Local (R2L) attacks by identifying suspicious and fraudulent behaviors through a two-tier module that utilizes the certainty factor of the K-Nearest Neighbor and Naïve Bayes classifier. Another paper [39] presents a different approach to accurately detecting fraud in IoT systems which uses artificial neural networks and machine learning models to process a large amount of financial data and detect fraud. In [40], the authors implemented a Node2Vec algorithm to learn and represent financial network graph features in a low-dimensional dense vector. This allowed the proposed model to accurately predict and classify data samples from big datasets with neural networks efficiently and accurately. A deep convolution neural network model that detects fraud is categorized into three stages [41]: before model application, which includes processing the data, model application, which applies the convolutional neural network, and the post-model application, where the output is received. Another study [42] presented an unsupervised self-organized mapping algorithm trained to produce a discretized representation of the input training samples with lower dimensions. This model is built on the behavior of cardholders. The work in [43] proposed a novel approach that uses decision trees to combine Hunt’s algorithm and Luhin’s algorithm. The credit card number is validated using Luhn’s algorithm. The correct billing address is checked through the address matching rule and checks if it matches the shipping address. If the shipping and billing addresses match, then the transaction is given a high probability to be genuine. In [44], the authors used several data mining techniques such as Support Vector Machines, Feedforward Neural Networks, Logistic Regression, Genetic Programming, and Probabilistic Neural Regression. A system was developed in [45] that used agglomerative clustering of fraudulent group orders that belonged to the same category. A comparative analysis of fraud detection applications is presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Comparative analysis of fraud detection applications.

As can be seen in the comparative analysis tables for both the cyber and fraud attack detection applications, the main limitations are not using any or using only one validation metric and using a single dataset. This decreases the credibility of those applications, as it is not made clear how the models perform with the test data. Additionally, using a single dataset does not validate the model’s performance, as cyberattack and fraud data are very dynamic with high variety, making it possible that a model performs well on one dataset and does not perform well on another dataset that contains different or more features. In addition, most of the work in the literature tuned a single model to achieve the best performance on the test data. We perceived that as a gap where we could use several high-performance models to create a stronger model or combine several weak models to enhance their performance through our proposed stacked generalization algorithm.

3. Methodology

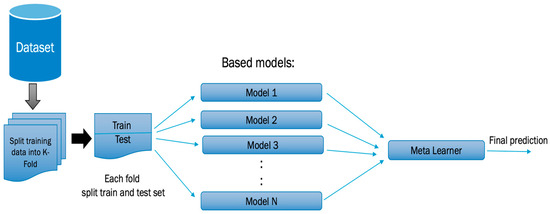

Stacking is a machine learning algorithm that combines different machine learning models to make predictions. Stacking exploits the fact that machine learning algorithms can have different skills for the same problem. Therefore, instead of trusting a single model to make predictions, stacking allows us to use different models to build a single robust model based on all the individual base models. Stacking ensemble models consist of the base models and the meta-learner. The base models are individual machine learning models that fit and make predictions on the training data. The second layer of the stacking ensemble model is the meta-learner. The meta-learner takes input from the base models’ output and learns how to make new predictions based on the predictions of the base models. The flowchart of our stacking algorithm is presented in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

The stacking algorithm flowchart.

We tested several machine learning algorithms as base models, including K-Nearest Neighbor (KNNs), Decision Trees (DTs), Gaussian Naive Bayes (GB), Support Vector Machines (SVMs), AdaBoost (AB), Gradient Boosting (GB), Random Forest (RF), Extra Trees (ET), Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP), and XGboost classifier. To choose our base models, we tested multiple machine learning algorithms on a credit card fraud dataset and two cyberattack data sets separately. On each dataset, the performance of each model was recorded, and the experiment was conducted with the best-performing models and the worst-performing models to examine the performance change when using the stacking ensemble models. Moreover, we experimented with different meta-learners to identify if this resulted in any change in performance and used the best performing meta-learner on each data set. The results of several machine learning algorithms, including MLP Classifier, XGBoost, and Gradient Boosting, were recorded, and the fastest and most accurate model was selected for each experiment as the meta learner.

In our stacking method, the computational complexity depends only on the base model with the highest computational time (i.e., Tmax). The computational cost of the stacking model is O(Tmax + t), where t is the additional linear time taken by the meta-learner. Thus, the overall stacking model scales well for large-scale datasets.

Preprocessing

We followed similar procedures to preprocess all datasets. First, the content of each dataset was visualized and analyzed to know the number of features, records, null values, and categorical features. The correlation between features was analyzed to remove redundant features from the datasets. We encoded the categorical features and applied normalization to put the features on the same scale. We had to split the data into training and testing for the fraud dataset using the 75–25% split, while the cyberattack datasets were already split. Moreover, the fraud detection dataset was highly imbalanced, in which the fraud class was significantly less than the non-fraud class in the dataset. Hence, we used undersampling to balance the number of classes in the dataset. We used 10-fold cross-validation when preparing the train set. The fold predictions from the base models were used to train the meta-model on the training datasets.

4. Experimental Results

4.1. Datasets

We trained our models using three different datasets. The ensemble model for cyberattack detection was trained on two different datasets: NSL-KDD and UNSW-NB15. On the other hand, the fraud detection ensemble model was only trained with one dataset due to the unavailability of any other dataset with sufficient records to train a complex model. All the datasets used in this paper are discussed below.

4.1.1. NSL-KDD

The NSL-KDD dataset comprises records of Internet traffic viewed by a rudimentary intrusion detection network. These records are the phantoms of traffic seen by a genuine IDS. The dataset has 43 attributes per record, with 41 relating to the traffic input and the remaining 2 being labels. One label indicates whether it is normal or an attack, and the second one indicates the traffic input’s severity. The NSL-KDD dataset is an improved version of the original KDD’99 dataset, which contained many redundant records. For the ease of the users, the NSL-KDD dataset has been split into the training and test sets by the authors. The train set comprises 125,973 records, and the test set contains 11,272 records. These data were collected as part of the Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining competition in 1999 to collect real network traffic data [46]. Moreover, the NSL-KDD train and test sets have a reasonable quantity of records, making it possible to execute the tests on the entire set without having to pick a tiny sample at random. Therefore, the assessment outcomes of various research projects will be uniform and easily comparable.

4.1.2. UNSW-NB15

The UNSW-NB15 dataset comprises raw network packets generated using the IXIA PerfectStorm tool in the University of New South Wales Canberra’s Cyber Range Lab to create a combination of real modern regular activities and synthetic recent attack behaviors. In it, 100 GB of raw traffic was captured using the tcpdump software. Fuzzers, analysis, backdoors, DoS, exploits, generic, reconnaissance, shellcode, and worms are among the nine types of attacks in this dataset [47]. There are a total of 2,540,044 records available in this dataset. A subset of the data was used as the training set, including 175,341 records. Another subset was configured as the testing set comprising 82,332 records. These sets contain records representing normal data and various types of attacks.

4.1.3. Credit Card Fraud Detection Dataset

This dataset covers credit card transactions performed by European cardholders in September 2013. There are 492 fraudulent records out of 284,807 transactions over 2 days in this dataset. Since it is a very unbalanced dataset, with fraudulent records accounting for just 0.172 percent of all transactions, we needed to preprocess the steps to balance the records between both classes. These data were collected as part of a significant data mining and fraud detection research cooperation between Worldline and the Machine Learning Group at Université Libre de Bruxelles (ULB) [48]. Due to data confidentiality issues, the data were transformed using PCA analysis and only contained the numerical values of principal components, except for two columns (“Amount” and “Time”). The “Time” column shows the elapsed time of each transaction from the first transaction, whereas the “Amount” column contains the transaction amount, which can be helpful for cost-sensitive analysis. The actual attributes and transactions data were inaccessible due to their sensitivity.

4.2. Experimental Results

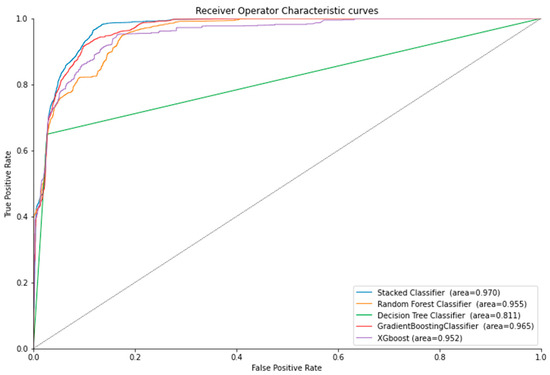

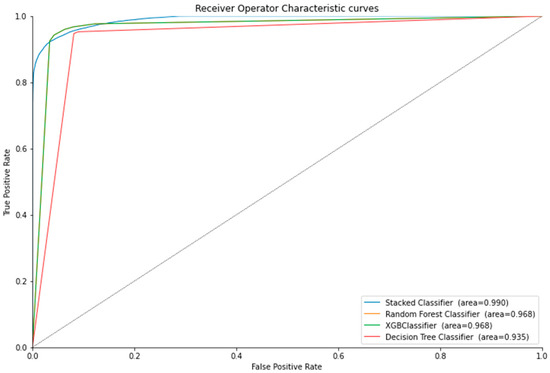

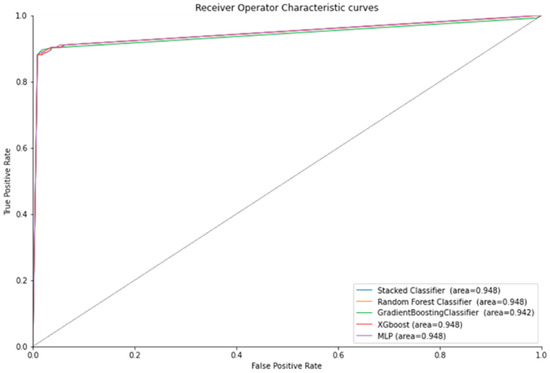

Table 4 represents the results for credit card fraud detection using ensemble stacking. The experiments were performed based on the top and poor performance of machine learning algorithms. We built different baseline models and performed 10-fold cross-validation to filter the top performing and poor performing baseline models to be used in level 0 of the stacked ensemble method. Various machine learning algorithms were chosen for different datasets as baseline models. For example, the top-performing machine learning algorithms for credit card fraud detection were Random Forest, XGBoost, MLP, and Gradient Boosting classifiers. However, for the NSL-KDD and UNSW datasets, the top-performing ML algorithms were Decision Tree, XGBoost, and Random Forest classifiers. The training time was also calculated for each individual model and ensemble stacking, as shown in Table 4, Table 5, Table 6 and Table 7. Figure 3 illustrates the ROC curves for the NSL-KDD dataset, and Figure 4 and Figure 5 illustrate the ROC curves for the UNSW, and credit card dataset, respectively. Table 4, Table 5, Table 6 and Table 7 showed higher training times for the top-performing ML algorithms than the low-performance baseline models. The ROC curve and accuracy were improved, but which method is most appropriate for a particular problem will depend on its circumstances. In the case where time is of utmost importance, we can use faster but poor-performing ML algorithms, and in the case where performance is of the utmost importance, we can use the top-performing ML algorithms.

Table 4.

Credit card fraud detection using ensemble stacking.

Table 5.

Cyberattack detection using ensemble stacking for 20% of the NSL_KDD dataset.

Table 6.

Cyberattack detection using ensemble stacking for the NSL_KDD dataset.

Table 7.

Cyberattack detection using ensemble stacking for the UNSW dataset.

Figure 3.

The ROC curve for the NSL-KDD dataset.

Figure 4.

The ROC curve for the UNSW dataset.

Figure 5.

The ROC curve for the credit card dataset.

5. Discussion

From the results in Table 4. we see that our stacked ensemble model performed better than all the base models and could detect frauds in credit card transactions with an accuracy of 93.5%. When comparing the two ensemble models based on strong and weak base models, we can see that they both performed equally, with the poor base ensemble model slightly edging out the strong base ensemble model. Moving on to the stacked ensemble models for cyberattack detection, we can see the performance of our model when trained with different datasets in Table 5, Table 6 and Table 7. The ensemble model trained with 20% of the NSL-KDD dataset performed better (81.28%) than the model trained with the entire NSL-KDD dataset (78.87%). This could be due to the overfitting problem when training with large datasets. Overfitting occurred when our machine learning model tried to cover all of the data points in a dataset or more than the required data points. As a result, the model began to collect noise and incorrect numbers in the dataset, reducing the model’s efficiency and accuracy. On the contrary, the capacity of a machine learning model to deliver an acceptable output by adapting to the provided set of unknown inputs is known as generalization. This indicates that training on the dataset can give accurate and dependable results. Therefore, we can conclude that the model trained on the entire NSL-KDD dataset overfit the training data and performed poorly on the test data, whereas the model trained on only 20% of the NSL-KDD dataset generalized well and could detect attacks accurately when tested on unknown data. When comparing the performance of our stacked ensemble model for cyberattack detection, we see that the UNSW-NB15 dataset achieved higher accuracy (95.15%) than the NSL-KDD dataset (81.28%).

Overall, we observed that the stacked ensemble models based on poor base models tended to give a higher accuracy than the ensemble model with strong base models. This could be because, with poor base models, there is more to learn for the meta-learner from each poor base model compared with the strong base models, since they are already very accurate. This pattern persisted in all the experiments except for one case. In Table 6, the ensemble stacked model with the strong base models performed slightly better than those with poor base models. We saw the same pattern in the training time of the stacked ensemble models. All the stacked models with poor base models had lower training times than the ensemble models with strong base models. Upon further observation, we concluded that the training time of the stacked ensemble model was directly correlated to the combined training time of its base models. Since the poor base models had lower training times than the strong base models in each case, the poor base stacked ensemble model also had a lower training time. Lastly, we saw from the ROC curves of each stacked ensemble model that the area under the curve (AUROC) was either higher or the same as all their respective base models. Hence, this proves that our stacked ensemble classifier performed better than the classifiers we used as base models.

6. Conclusions and Future Work

Due to the rapid growth in the development and usage of the IoT, its interconnectivity has also increased the amount of data processed [49,50,51,52,53], thus subjecting the application to being vulnerable to various kinds of cyberattacks. Cyber security continues to be a serious issue in every sector of cyberspace. Therefore, there is a strong need to protect this data from intrusion attacks and enhance the industry detection systems to ensure the end users’ safety. Our literature review shows that cyberattacks are a significant threat in all industries where IoT applications are deployed. Furthermore, we classified the primary attacks in the three major layers of the IoT, followed by different state-of-the-art methods being used in the industry today in IoT applications to detect and attribute these attacks. For this purpose, we highlighted and discussed multiple machine learning and deep learning models and identified their strengths and limitations. After reviewing the main methods from recent papers, we concluded that deep learning approaches for detecting and attributing attacks tended to perform better than traditional machine learning models. Similarly, the best and most widely used datasets to train and test one’s model for this purpose are the NSL-KDD and UNSW-NB15 datasets because they provide flexibility and comprise most of the primary attacks found in the industry. Moreover, we also highlighted various methods of detecting fraud attacks in IoT systems, because this is a growing problem in the finance industry and needs to be addressed soon. We saw a wide range of techniques used in this sector to detect fraud and summarized their strengths and weaknesses in Table 3. Therefore, we have presented a unique approach in this paper to detecting cyberattacks and credit card fraud in IoT systems. The method presented in this paper solves the problem of cyberattack detection in network traffic and can also detect fraud in credit card transactions with a high accuracy. Our most accurate model for cyberattack detection was “ensemble stacking (poor) on UNSW-NB15” with an accuracy of 95.15% and training time of 565.65 s. Similarly, our “ensemble stacking (poor) model for credit card fraud detection” performed with an accuracy of 93.50% and training time of only 8.42 s. These results show a significant improvement compared with most of the papers reviewed and discussed in Section 2. We believe that using the ensemble stacking method to solve cyberattacks and credit card fraud problems has immense potential and could be further optimized by testing different combinations of base models and the number of folds in the model. For future work, we would like to train our algorithm using distributed learning, which is expected to decrease the training duration of developing our proposed model significantly. In addition, we can test more models and analyze their performance to experiment with whether we can construct higher-performing ensemble models. Finally, we can examine the performance of different ensemble algorithms. Transfer learning is considered a future direction for this research.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.S., M.A., M.W.Q. and R.K.; methodology, R.S., M.A., M.W.Q. and R.K.; software, R.S., M.A. and M.W.Q.; validation, R.S., M.A., M.W.Q. and R.K.; formal analysis, R.S., M.A., M.W.Q. and R.K.; investigation, R.S., M.A., M.W.Q. and R.K.; resources, R.S., M.A. and M.W.Q.; data curation, R.S., M.A. and M.W.Q.; writing—original draft preparation, R.S., M.A., M.W.Q. and R.K.; writing—review and editing, R.K.; visualization, R.S., M.A. and M.W.Q.; supervision, R.K.; project administration, R.K.; funding acquisition, R.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Available in References [47,48,49].

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Rizvi, S.; Kurtz, A.; Pfeffer, J.; Rizvi, M. Securing the internet of things (IoT): A security taxonomy for iot. In Proceedings of the 2018 17th IEEE International Conference On Trust, Security and Privacy in Computing and Communications/12th IEEE International Conference On Big Data Science And Engineering (TrustCom/BigDataSE), New York, NY, USA, 1–3 August 2018; pp. 163–168. [Google Scholar]

- Miraz, M.H.; Ali, M.; Excell, P.S.; Picking, R. A review on internet of things (iot), internet of everything (ioe) and internet of nano things (iont). In Proceedings of the 2015 Internet Technologies and Applications (ITA), Wrexham, UK, 8–11 September 2015; IEEE: Manhattan, NY, USA, 2015; pp. 219–224. [Google Scholar]

- Burhan, M.; Rehman, R.A.; Khan, B.; Kim, B.-S. IoT Elements, Layered Architectures and Security Issues: A Comprehensive Survey. Sensors 2018, 18, 2796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gates, T.; Jacob, K. Payments fraud: Perception versus reality—A conference summary. Econ. Perspect. 2009, 33, 7–15. [Google Scholar]

- Radanliev, P.; De Roure, D.; van Kleek, M.; Cannady, S. Artificial Intelligence and Cyber Risk Super-forecasting. Connect. Q. J. 2020, 2, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, T. A reliable communication framework and its use in internet of things (iot). Int. J. Sci. Res. Comput. Sci. Eng. Inf. Technol. 2018, 3, 450–456. [Google Scholar]

- Alaba, F.A.; Othman, M.; Hashem, I.A.T.; Alotaibi, F. Internet of Things security: A survey. J. Netw. Comput. Appl. 2017, 88, 10–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sethi, P.; Sarangi, S.R. Internet of things: Architectures, protocols, and applications. J. Electr. Comput. Eng. 2017, 2017, 9324035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sezer, O.B.; Dogdu, E.; Ozbayoglu, A.M. Context-aware computing, learning, and big data in internet of things: A survey. IEEE Internet Things J. 2017, 5, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Payal, A.; Bharti, S. A walkthrough of the emerging iot paradigm: Visualizing inside functionalities, key features, and open issues. J. Netw. Comput. Appl. 2019, 143, 111–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geetha, R.; Thilagam, T. A review on the effectiveness of machine learning and deep learning algorithms for cyber security. Arch. Comput. Methods Eng. 2021, 28, 2861–2879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, A.H.K.; Jebamikyous, H.; Nawara, D.; Kashef, R. Iot cyber-attack detection: A comparative analysis. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Data Science, E-Learning and Information Systems, Ma’an, Jordon, 5–7 April 2021; pp. 117–123. [Google Scholar]

- Sajjad, H.; Arshad, M. Evaluating Security Threats for Each Layers of IOT System. 2019. Volume 10, pp. 20–28. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/336149742_Evaluating_Security_Threats_for_each_Layers_of_IoT_System (accessed on 25 December 2021).

- Mohanta, B.K.; Jena, D.; Satapathy, U.; Patnaik, S. Survey on IoT security: Challenges and solution using machine learning, artificial intelligence and blockchain technology. Internet Things 2020, 11, 100227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baig, Z.; Sanguanpong, S.; Firdous, S.N.; Vo, V.N.; Nguyen, T.; So-In, C. Averaged dependence estimators for DoS attack detection in IoT networks. Futur. Gener. Comput. Syst. 2020, 102, 198–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Qin, Z.; Novak, E.; Li, Q. Securing SDN Infrastructure of IoT–Fog Networks From MitM Attacks. IEEE Internet Things J. 2017, 4, 1156–1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishna, B.S.; Gnanasekaran, T. A systematic study of security issues in Internet-of-Things (IoT). In Proceedings of the 2017 International Conference on I-SMAC (IoT in Social, Mobile, Analytics and Cloud) (I-SMAC), Palladam, India, 10–11 February 2017; pp. 107–111. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, J.; Cao, Z.; Dong, X.; Vasilakos, A.V. Security and Privacy for Cloud-Based IoT: Challenges. IEEE Commun. Mag. 2017, 55, 26–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, Y.; Sengupta, S. A survey on Classification of Cyber-attacks on IoT and IIoT devices. In Proceedings of the 2020 11th IEEE Annual Ubiquitous Computing, Electronics & Mobile Communication Conference (UEMCON), New York, NY, USA, 28–31 October 2020; pp. 406–413. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, P.; Nagarajan, S.G.; Nevat, I. Secure location of things (slot): Mitigating localization spoofing attacks in the internet of things. IEEE Internet Things J. 2017, 4, 2199–2206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, M.; Peinado, A.; Ortiz, A. An extensive validation of a sir epidemic model to study the propagation of jamming attacks against iot wireless networks. Comput. Netw. 2019, 165, 106945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panchal, A.C.; Khadse, V.M.; Mahalle, P.N. Security issues in iiot: A comprehensive survey of attacks on iiot and its countermeasures. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE Global Conference on Wireless Computing and Networking (GCWCN), Lonavala, India, 23–24 November 2018; pp. 124–130. [Google Scholar]

- Aktukmak, M.; Yilmaz, Y.; Uysal, I. Sequential Attack Detection in Recommender Systems; IEEE: Manhattan, NY, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Anthi, E.; Williams, L.; Slowinska, M.; Theodorakopoulos, G.; Burnap, P. A Supervised Intrusion Detection System for Smart Home IoT Devices. IEEE Internet Things J. 2019, 6, 9042–9053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlZubi, A.A.; Al-Maitah, M.; Alarifi, A. Cyber-attack detection in healthcare using cyber-physical system and machine learning techniques. Soft Comput. 2021, 25, 12319–12332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashid, M.M.; Kamruzzaman, J.; Imam, T.; Kaisar, S.; Alam, M.J. Cyber attacks detection from smart city applications using artificial neural network. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE Asia-Pacific Conference on Computer Science and Data Engineering (CSDE), Gold Coast, Australia, 16–18 December 2020; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Taheri, S.; Gondal, I.; Bagirov, A.; Harkness, G.; Brown, S.; Chi, C. Multisource cyber-attacks detection using machine learning. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE International Conference on Industrial Technology (ICIT), Melbourne, Australia, 13–15 February 2019; pp. 1167–1172. [Google Scholar]

- Cristiani, A.L.; Lieira, D.D.; Meneguette, R.I.; Camargo, H.A. A fuzzy intrusion detection system for identifying cyber-attacks on iot networks. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE Latin-American Conference on Communications (LATINCOM), Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic, 18–20 November 2020; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Rathore, S.; Park, J.H. Semi-supervised learning based distributed attack detection framework for IoT. Appl. Soft Comput. 2018, 72, 79–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahromi, A.N.; Karimipour, H.; Dehghantanha, A.; Choo, K.K.R. Toward detection and attribution of cyber-attacks in iot-enabled cyber-physical systems. IEEE Internet Things J. 2021, 8, 13712–13722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Fernandes, S.V.; Padmanabha, V.; Rubini, P.E. Mcids-multi classifier intrusion detection system for iot cyber attack using deep learning algorithm. In Proceedings of the 2021 Third International Conference on Intelligent Communication Technologies and Virtual Mobile Networks (ICICV), Tirunelveli, India, 4–6 February 2021; pp. 354–360. [Google Scholar]

- Battisti, F.; Bernieri, G.; Carli, M.; Lopardo, M.; Pascucci, F. Detecting integrity attacks in iot-based cyber physical systems: A case study on hydra testbed. In Proceedings of the 2018 Global Internet of Things Summit (GIoTS), Bilbao, Spain, 4–7 June 2018; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Diro, A.A.; Chilamkurti, N. Distributed attack detection scheme using deep learning approach for internet of things. Future Gener. Comput. Syst. 2018, 82, 761–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moussa, M.M.; Alazzawi, L. Cyber attacks detection based on deep learning for cloud-dew computing in automotive iot applications. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE International Conference on Smart Cloud (SmartCloud), Washington, DC, USA, 6–8 November 2020; pp. 55–61. [Google Scholar]

- Soe, Y.N.; Feng, Y.; Santosa, P.I.; Hartanto, R.; Sakurai, K. Towards a lightweight detection system for cyber attacks in the iot environment using corresponding features. Electronics 2020, 9, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Abu Al-Haija, Q.; Zein-Sabatto, S. An Efficient Deep-Learning-Based Detection and Classification System for Cyber-Attacks in IoT Communication Networks. Electronics 2020, 9, 2152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, K.N.; Pandey, S.C. Fraud Prediction in Smart Societies Using Logistic Regression and k-fold Machine Learning Techniques. Wirel. Pers. Commun. 2021, 119, 1341–1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pajouh, H.H.; Javidan, R.; Khayami, R.; Dehghantanha, A.; Choo, K.-K.R. A Two-Layer Dimension Reduction and Two-Tier Classification Model for Anomaly-Based Intrusion Detection in IoT Backbone Networks. IEEE Trans. Emerg. Top. Comput. 2016, 7, 314–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, D.; Lee, K. An Artificial Intelligence Approach to Financial Fraud Detection under IoT Environment: A Survey and Implementation. Secur. Commun. Netw. 2018, 2018, 5483472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhou, H.; Sun, G.; Fu, S.; Wang, L.; Hu, J.; Gao, Y. Internet financial fraud detection based on a distributed big data approach with node2vec. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 43378–43386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ram, S.; Gupta, S.; Agarwal, B. Devanagri character recognition model using deep convolution neural network. J. Stat. Manag. Syst. 2018, 21, 593–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; You, F.; Liu, H. Behavior-based credit card fraud detecting model. In Proceedings of the 2009 Fifth International Joint Conference on INC, IMS and IDC, Seoul, Korea, 25–27 August 2009; pp. 855–858. [Google Scholar]

- Save, P.; Tiwarekar, P.; Jain, K.N.; Mahyavanshi, N. A Novel Idea for Credit Card Fraud Detection using Decision Tree. Int. J. Comput. Appl. 2017, 161, 6–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravisankar, P.; Ravi, V.; Rao, G.R.; Bose, I. Detection of financial statement fraud and feature selection using data mining techniques. Decis. Support Syst. 2011, 50, 491–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchal, S.; Szyller, S. Detecting organized ecommerce fraud using scalable categorical clustering. In Proceedings of the 35th Annual Computer Security Applications Conference, San Juan, PR, USA, 9–13 December 2019; pp. 215–228. [Google Scholar]

- Revathi, S.; Malathi, A. A detailed analysis on nsl-kdd dataset using various machine learning techniques for intrusion detection. Int. J. Eng. Res. Technol. 2013, 2, 1848–1853. [Google Scholar]

- Moustafa, N.; Slay, J. Unsw-nb15: A comprehensive data set for network intrusion detection systems. In Proceedings of the 2015 Military Communications and Information Systems Conference (MilCIS), Canberra, Australia, 10–12 November 2015; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Creditcard Fraud Dataset. Available online: https://www.kaggle.com/mlg-ulb/creditcardfraud (accessed on 23 November 2021).

- Kashef, R. A boosted SVM classifier trained by incremental learning and decremental unlearning approach. Expert Syst. Appl. 2021, 167, 114154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nawara, D.; Kashef, R. IoT-based Recommendation Systems–An Overview. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE International IOT, Electronics and Mechatronics Conference (IEMTRONICS), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 9–12 September 2020; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Kashef, R.F. Ensemble-Based Anomaly Detetction using Cooperative Learning. In KDD 2017 Workshop on Anomaly Detection in Finance; PMLR: Halifax, Canada, 2018; pp. 43–55. [Google Scholar]

- Close, L.; Kashef, R. Combining Artificial Immune System and Clustering Analysis: A Stock Market Anomaly Detection Model. J. Intell. Learn. Syst. Appl. 2020, 12, 83–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashef, R. Enhancing the Role of Large-Scale Recommendation Systems in the IoT Context. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 178248–178257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).