US Nurses’ Challenges with Personal Protective Equipment during COVID-19: Interview Findings from the Frontline Workforce

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Methods

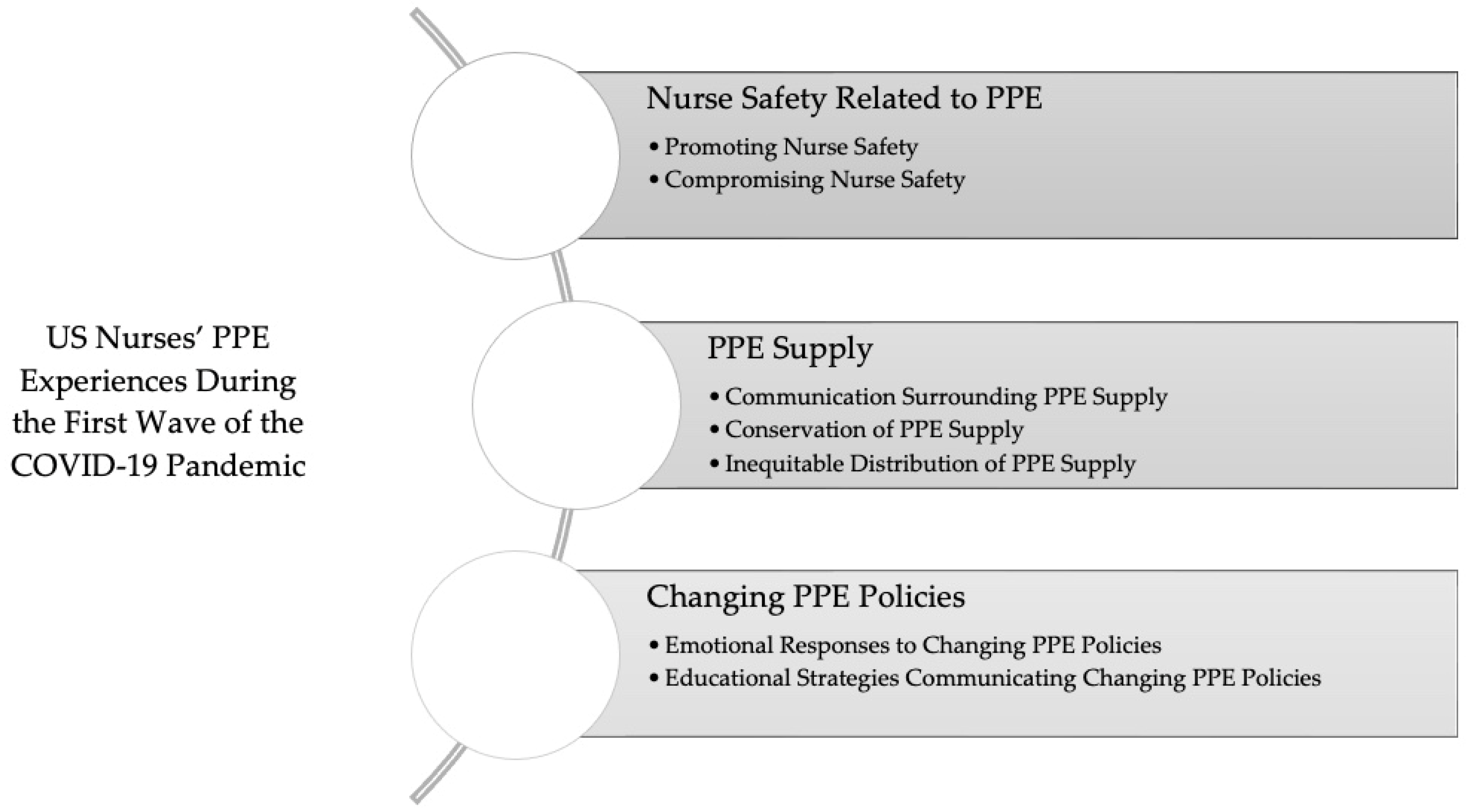

3. Results

3.1. Nurse Safety Related to PPE

3.1.1. Promoting Nurse Safety

“Your co-worker…would be your buddy and they would verify…what you’re wearing before you go in the rooms, that you’re meeting compliance and that you didn’t miss anything. And then, also, they would help you while you were in the room. So, you didn’t come out and make a mistake…get whatever you need… When you came out, when you would doff your PPE, they also checked and made sure you didn’t contaminate one of your clean sterile surfaces outside the room and make sure that you cleaned everything”.

3.1.2. Compromising Nurse Safety

3.2. PPE Supply

3.2.1. Communication Surrounding PPE Supply

“In the beginning, it seemed like everyone was so concerned about it [PPE] nationwide. And... we did get a good amount of reassurance from the hospital that we had plenty, but they never really told us… how much. And they there was unclear messaging from the hospital on whether we were supposed to wear things for an extended amount of time or reuse them… There was a lot of anxiety about PPE and there still is.”

3.2.2. Conservation of PPE Supply

“They store the N95s now in the Omnicell with the drugs and we have to count them like narcotics. So, when [the masks] broke we had to email the manager and I had to leave the broken one so [the administrators] could see that.... [the N95s are] stored in there with like Dilaudid and Valium… It’s not a dangerous thing.”

3.2.3. Inequitable Distribution of PPE Supply

“When an anesthesiologist comes in [to place an epidural in labor and delivery] ...the anesthesiologist wears an N95, any time they’re in our room. So that’s different… than how I am exposed...I feel like that’s discouraging and I feel like that is...giving a hierarchy to roles that that shouldn’t exist, you know. That’s not fair to anyone other than the anesthesiologist...it felt like we didn’t really have a hospital wide policy... So that’s been a complicated thing to deal with.”

3.3. Changing PPE Policies

3.3.1. Emotional Responses to Changing PPE Policies

“It was frustrating and…scary because we wanted to be protected. We were the ones. The nurses at the frontline one-on-one with the patients. And we wanted to know that we were protected while we did our job.”

“It was very hard…You mentally have to go in and prepare yourself, that you’re putting your life at risk. And literally months prior, you never had to reuse personal protective equipment…We were always told new gown, new mask and new gloves for every patient. Right? So, when COVID-19 started, there [wasn’t] enough. We’re locking up [PPE]. So, you better conserve what you have. And you’re using this mask for umpteen times. And so, who knows the safety of how many times using this mask it is still effective… There was so much uncertainty and it put a lot of anxiety on the work. Am I putting myself at risk? …Having to talk myself down and say, ‘I’m trying the best I can, I’m going to try to get PPE that I have, hopefully I’m doing the best that I can, hopefully I’m not spreading it or giving it to any of my family members coming home.”

3.3.2. Educational Strategies Communicating Changing PPE Policies

4. Discussion

4.1. Limitations

4.2. Implications for Clinical Practice

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- McIntosh, K.; Hirsch, M.S.; Bloom, A.J. Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19): Epidemiology, Virology, Clinical Features, Diagnosis, and Prevention, 2020. UpToDate. Available online: https://www.uptodate.com/contents/coronavirus-disease-2019-covid-19-epidemiology-virology-clinical-features-diagnosis-and-prevention/print (accessed on 1 December 2020).

- World Health Organization. Weekly Epidemiological Update on COVID-19; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022; Available online: https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/situation-reports/20220329_weekly_epi_update_85.pdf?sfvrsn=16aaa557_4&download=true (accessed on 29 March 2022).

- Iuliano, A.D.; Brunkard, J.M.; Boehmer, T.K.; Peterson, E.; Adjei, S.; Binder, A.M.; Cobb, S.; Graff, P.; Hidalgo, P.; Panaggio, M.J.; et al. Trends in Disease Severity and Health Care Utilization during the Early Omicron Variant Period Compared with Previous SARS-CoV-2 High Transmission Periods—United States, December 2020—January 2022. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2022, 71, 146–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, J.; van der Meulen Rodgers, Y. Contributing factors to personal protective equipment shortages during the COVID-19 pandemic. Prev. Med. 2020, 141, 106263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, L.; Munroe, J.; Rogers, S. Use of personal protective equipment in nursing practice. Nurs. Stand. 2019, 34, 59–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Shortage of Personal Protective Equipment Endangering Health Workers Worldwide; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020; Available online: https://www.who.int/news/item/03-03-2020-shortage-of-personal-protective-equipment-endangering-health-workers-worldwide (accessed on 3 March 2020).

- Padilla, M. ‘It Feels Like a War Zone’: Doctors and Nurses Plead for Masks on Social Media, 19 March 2020. New York Times. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/2020/03/19/us/hospitals-coronavirus-ppe-shortage.html (accessed on 1 December 2020).

- Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Pandemic Planning: Recommended Guidance for Extended Use and Limited Reuse of N95 Filtering Facepiece Respirators in Healthcare Settings; Center for Disease Control and Prevention: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2020. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/topics/hcwcontrols/recommendedguidanceextuse.html (accessed on 1 December 2020).

- Min, H.S.; Moon, S.; Jang, Y.; Cho, I.; Jeon, J.; Sung, H.K. The Use of Personal Protective Equipment among Frontline Nurses in a Nationally Designated COVID-19 Hospital during the Pandemic. Infect. Chemother. 2021, 53, 705–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ezike, O.C.; Odikpo, L.C.; Onyia, E.N.; Egbuniwe, M.C.; Ndubuisi, I.; Nwaneri, A.C.; Ihudiebube-Splendor, C.N.; Irodi, C.C.; Danlami, S.B.; Abdussalam, W.A. Risk Perception, risk Involvement/Exposure and compliance to preventive measures to COVID-19 among nurses in a tertiary hospital in Asaba, Nigeria. Int. J. Afr. Nurs. Sci. 2021, 16, 100385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tune, S.N.B.K.; Islam, B.Z.; Islam, M.R.; Tasnim, Z.; Ahmed, S.M. Exploring the knowledge, attitudes, practices and lived experiences of frontline health workers in the times of COVID-19: A qualitative study from Bangladesh. BMJ Open 2022, 12, e051893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sundararajan, K.; Bi, P.; Milazzo, A.; Poole, A.; Reddi, B.; Mahmood, M.A. Preparedness and response to COVID-19 in a quaternary intensive care unit in Australia: Perspectives and insights from frontline critical care clinicians. BMJ Open 2022, 12, e051982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Polit, D.F.; Beck, C.T. Nursing Research; Lippincott Williams & Wilkins: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Webber-Ritchey, K.J.; Simonovich, S.D.; Spurlark, R.S. COVID-19: Qualitative Research With Vulnerable Populations. Nurs. Sci. Q. 2021, 34, 13–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Webber-Ritchey, K.J.; Aquino, E.; Ponder, T.N.; Lattner, C.; Soco, C.; Spurlark, R.; Simonovich, S.D. Recruitment Strategies to Optimize Participation by Diverse Populations. Nurs. Sci. Q. 2021, 34, 235–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simonovich, S.D.; Spurlark, R.S.; Badowski, D.; Krawczyk, S.; Soco, C.; Ponder, T.N.; Rhyner, D.; Waid, R.; Aquino, E.; Lattner, C.; et al. Examining effective communication in nursing practice during COVID-19: A large-scale qualitative study. Int. Nurs. Rev. 2021, 68, 512–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simonovich, S.D.; Webber-Ritchey, K.J.; Spurlark, R.S.; Florczak, K.; Mueller Wiesemann, L.; Ponder, T.N.; Reid, M.; Shino, D.; Stevens, B.R.; Aquino, E.; et al. Moral Distress Experienced by US Nurses on the Frontlines during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Implications for Nursing Policy and Practice. SAGE Open Nurs. 2022, 8, 23779608221091059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Badowski, D.M.; Spurlark, R.; Webber-Ritchey, K.J.; Towson, S.; Ponder, T.N.; Simonovich, S.D. Envisioning Nursing Education for a Post-COVID-19 World: Qualitative Findings from the Frontline. J. Nurs. Educ. 2021, 60, 668–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Livingston, E.; Desai, A.; Berkwits, M. Sourcing Personal Protective Equipment during the COVID-19 Pandemic. JAMA 2020, 323, 1912–1914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Emanuel, E.J.; Persad, G.; Upshur, R.; Thome, B.; Parker, M.; Glickman, A.; Zhang, C.; Boyle, C.; Smith, M.; Phillips, J.P. Fair Allocation of Scarce Medical Resources in the Time of COVID-19. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 382, 2049–2055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hertel, R. The use of psychological PPE in the face of COVID-19. Nursing 2020, 29, 293–296. [Google Scholar]

- Rau, J. Federal Help Falters as Nursing Homes Run Short of Protective Equipment, 11 June 2020. Kaiser Health News. Available online: https://khn.org/news/federal-help-falters-as-nursing-homes-run-short-of-protective-equipment/ (accessed on 19 April 2021).

- American Nurses Association. PPE survey final report. Vt. Nurse Connect. 2020, 11–15. [Google Scholar]

- Humphreys, J.; Joseph, D.M. A Trauma-Informed Response to Working in Humanitarian Crises. In A Field Manual for Palliative Care in Humanitarian Crises; Waldman, E., Glass, M., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2019; pp. 133–140. [Google Scholar]

- Kellogg, M.; Scherr, S.A.; Ayotte, B. All of this was awful: “Exploring the experience of nurses caring for patients with COVID-19 in the United States. Nurs. Forum 2021, 56, 869–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- U.S. Department of Labor Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA). Guidance on Preparing Workplaces for COVID-19; OSHA: Washington, DC, USA, 2020. Available online: https://www.osha.gov/Publications/OSHA3990.pdf (accessed on 1 December 2020).

- Eldridge, C.C.; Hampton, D.; Marfell, J. Communication during crisis. Nurs. Manag. 2020, 51, 50–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Council of State Boards of Nursing. NCSBN’s environmental scan: A portrait of nursing and healthcare in 2020 and beyond. J. Nurs. Regul. 2020, 10, S1–S36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable Name | # | |

| Age | ||

| Mean | 37.9 | |

| Range | 38 | |

| Min, Max | 24, 62 | |

| Gender | ||

| Female | 84 | |

| Male | 14 | |

| Trans/Non-Binary | 2 | |

| Race | ||

| White | 57 | |

| Black or African American | 20 | |

| Asian | 14 | |

| Multiracial | 7 | |

| American Indian | 2 | |

| Ethnicity | ||

| Hispanic | 20 | |

| Non-Hispanic | 80 | |

| Education | ||

| Diploma | 1 | |

| Licensed Practical Nurse | 2 | |

| Associate’s Degree | 4 | |

| Bachelor’s Degree | 41 | |

| Master’s Degree | 42 | |

| DNP | 9 | |

| PhD | 1 | |

| Years of Nursing Experience | ||

| Mean | 11.04 | |

| Range | 41 | |

| Min, Max | <1, 42 | |

| Employment | ||

| Academic Medical Center | 36 | |

| Multi-Center Hospital System | 17 | |

| Independent Community Hospital | 16 | |

| Outpatient/Community-Based | 23 | |

| Federal Hospital System | 5 | |

| Preferred Not to Report | 3 | |

| Specialty | ||

| Emergency Department | 19 | |

| Intensive Care Unit | 13 | |

| Medical/Surgical Nursing | 13 | |

| Labor and Delivery | 22 | |

| Outpatient/Community | 14 | |

| Anesthesia | 2 | |

| Leadership | 7 | |

| Multiple Specialties | 10 | |

| 3.1. Nurse Safety Related to PPE | |

| 3.1.1. Promoting Nurse Safety | |

| “There’s definitely a certain amount of paying more attention to… what I’m doing and what am I touching, and what do I need to do when I leave this room. And making sure that the N95 that we are assigned is clean and continues to stay as clean as possible when I’m going in and leaving the room.” | |

| “We were doing something that is called ‘validating and screening.’ So, I would be put in areas to watch the nurses, watch the doctors, watch the different staff members going in and out of these rooms, making sure they were wearing the correct PPE.” | |

| “Your co-worker may have two non-COVID patients [in the same] ICU. They would be your buddy and they would verify…what you’re wearing before you go in the rooms, that you’re meeting compliance and that you didn’t miss anything. And then, also, they would help you while you were in the room. So, you didn’t come out and make a mistake…get whatever you need. And then also, when you came out, when you would doff your PPE, they also checked and made sure you didn’t contaminate one of your clean sterile surfaces outside the room and make sure that you cleaned everything. So, it was a bit of a buddy system going on at first. I would say, it went on for about a good three weeks, almost a month.” | |

| “I know that that was very important, making sure that no one had an expired fit test and then making sure that everyone was trained properly on donning and doffing. That was something that was routinely reviewed with both day and night shift.” | |

| 3.1.2. Compromising Nurse Safety | |

| “We went from using a plastic gown that helped keep out moisture, water, blood, to cloth gowns that pretty much soak up anything that can get through that [can] go into your skin.” | |

| “I think it was there was a manufacture issue because the [masks] straps kept on breaking, like every time you put it on [the mask] the straps would break.” | |

| “The N95 masks, we leave them in Tupperware containers, and then they sanitize them with UV lights. It did feel like after using the same one for months, that it was just like it felt like it. I don’t know that it really was effective. I felt like the fibers of it were almost coming apart.” | |

| 3.2. PPE Supply | |

| 3.2.1. Communication Surrounding PPE Supply | |

| “Daily, we had a list of how many days on hand that we had of gowns, regular surgical masks, N95s. Hand gel was a big one. And anything less than five days at hand, it would be…a red flag.” | |

| “They started making binders as far as a process and what to do. And then they …color coded the importance of the N95s... And if they if they had enough PPE, they would the color code red, green, yellow.” | |

| “Well, I think we tried to make sure we had the PPE we needed... In the beginning, it seemed like everyone was so concerned about [PPE] nationwide. And...we did get a good amount of reassurance from the hospital that we had plenty, but they never really told us how much. And there was unclear messaging from the hospital on whether we were supposed to wear things for an extended amount of time or reuse them. So, I think there was a lot of anxiety about PPE and there still is.” | |

| 3.2.2. Conservation of PPE Supply | |

| “I try to be conscientious of what I’m using…For example, when I’m seeing patients in clinic, my face shield…I just clean it and I try to use it for…at least about a month and then I’ll switch it out. Masks I will use one a day if possible.” | |

| “So, one of the barriers that we had was finding PPE. Enough PPE for our personnel. So, PPE was being shared amongst staff.” | |

| “We were having the shortages of PPE. [We] were reusing our N95 for three or four nights…and we’re all keeping our N95’s in a paper bag…We [had] a cleaning blue light filtration system.” | |

| “The nursing manager would keep [the PPE] in the office, and then bring it out when there was none on the unit.” | |

| “They store the N95s now in the Omnicell with the drugs and we have to count them like narcotics. So, when [the masks] broke we had to email the manager and I had to leave the broken one so [the administrators] could see that…. [the N95s are] stored in there with like Dilaudid and Valium… It’s not a dangerous thing.” | |

| 3.2.3. Inequitable Distribution of PPE Supply | |

| “They were being pretty, uh stingy at the beginning, which was pretty frustrating… We are an emergency room, [and we might] only have two COVID positive patients. [They say] ‘you don’t need that much supply…’ but we we’re seeing patients off the street…And we were getting stressed out because we have the operating room. So…we also need our normal PPE because we’re doing surgery. So that was pretty stressful because I’m sure every floor is like asking ‘we need this, we need gowns, we need this.’ [But] we have an operating room. We have to have [PPE].” | |

| “When an anesthesiologist comes in [to place an epidural in labor and delivery]...the anesthesiologist wears an N95, any time they’re in our room. So that’s different. That’s different than how I am exposed...I feel like that’s discouraging and I feel like that is...giving a hierarchy to roles that that shouldn’t exist, you know. That’s not fair to anyone other than the anesthesiologist...it felt like we didn’t really have a hospital wide policy for quite a while…as things progressed. So that’s been a complicated thing to deal with.“ | |

| “We drove to Wisconsin to purchase respirators with our own money because the hospital didn’t have enough masks.” | |

| “They would hide the PPE. Our night shift would hide it from day shift, day shift would track more PPE for night shift. But the hospital was only giving a certain amount of PPE. So physically we were hiding it. We had to hide equipment.” | |

| 3.3. Changing PPE Policies | |

| 3.3.1. Emotional Responses to Changing PPE Policies | |

| “It was sort of stressful, I don’t usually get flustered, but it was sort of stressful, it’s like, what actually are the rules?” | |

| I don’t see why we have to do it [lock N95s in Omnicell] like they [administration] don’t trust us… It’s frustrating because I have all that education and then I go to work and I’m forced to count masks.” | |

| “It was frustrating and…scary because we wanted to be protected. We were the ones. The nurses at the frontline one-on-one with the patients. And we wanted to know that we were protected while we did our job. So, at first it was very frustrating. And we just had to learn how to bypass that and then just continue to provide the care that we needed to.” | |

| “It was very hard. You know, you get stressed. You mentally have to go in and prepare yourself, that you’re putting your life at risk. And literally months prior, you never had to reuse personal protective equipment…We were always told new gown, new mask and new gloves for every patient. Right? So, when COVID-19 started, there [wasn’t] enough. We’re locking up [PPE]. So, you better conserve what you have. And you’re using this mask for umpteen times. And so, who knows the safety of how many times using this mask it is still effective… There was so much uncertainty and it put a lot of anxiety on the work. Am I putting myself at risk? …Having to talk myself down and say, ‘I’m trying the best I can, I’m going to try to get PPE that I have, hopefully I’m doing the best that I can, hopefully I’m not spreading it or giving it to any of my family members coming home.’” | |

| 3.3.2. Educational Strategies Communicating Changing PPE Policies | |

| “Hospital nursing leadership would come do rounds during the various shifts and explain like what was going on around nearby hospitals. They would print out articles about…the CDC’s guidelines…what COVID was, [and] droplet or airborne [precautions].” | |

| “The only thing they did was download YouTube videos on how to don on doff the PPE equipment. So that was helpful because for the learners that are visual, it helped reiterate the importance of having one person watching.” | |

| “We had PPE coaches in the unit. This was actually staff members from our day surgery department that was actually shut down during the pandemic when the surge was higher. So, they gave us the tools… follow with those changing recommendations that were happening and they provided us with the proper PPE. They listened to our concerns. So, I think that was main thing that they prepared us to be prepared.” | |

| “They had to make sure that everyone had watched… the CDC videos about using PPE appropriately and being really transparent about our PPE supplies and being really transparent about our processes for procuring it, having very clear guidelines for how to order [PPE] and when to use it, and conservation strategies based on our capacity… That was really helpful.” | |

| “We had frequent emails that were sent out for daily updates on COVID-19, and then they were also putting together resource binders for COVID-19 on different updates, on how to set up a room if you’re expecting it on a new admission patient on the unit who’s expecting to have COVID-19 or be ruled out, so making sure that all the proper items and PPE were stocked in the room and having that set up correctly.” | |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Simonovich, S.D.; Aquino, E.; Lattner, C.; Soco, C.; Ponder, T.N.; Amer, L.; Howard, S.; Nwafor, G.; Shah, P.; Badowski, D.; et al. US Nurses’ Challenges with Personal Protective Equipment during COVID-19: Interview Findings from the Frontline Workforce. Psych 2022, 4, 226-237. https://doi.org/10.3390/psych4020019

Simonovich SD, Aquino E, Lattner C, Soco C, Ponder TN, Amer L, Howard S, Nwafor G, Shah P, Badowski D, et al. US Nurses’ Challenges with Personal Protective Equipment during COVID-19: Interview Findings from the Frontline Workforce. Psych. 2022; 4(2):226-237. https://doi.org/10.3390/psych4020019

Chicago/Turabian StyleSimonovich, Shannon D., Elizabeth Aquino, Christina Lattner, Cheryl Soco, Tiffany N. Ponder, Lily Amer, Stephanie Howard, Gilliane Nwafor, Payal Shah, Donna Badowski, and et al. 2022. "US Nurses’ Challenges with Personal Protective Equipment during COVID-19: Interview Findings from the Frontline Workforce" Psych 4, no. 2: 226-237. https://doi.org/10.3390/psych4020019

APA StyleSimonovich, S. D., Aquino, E., Lattner, C., Soco, C., Ponder, T. N., Amer, L., Howard, S., Nwafor, G., Shah, P., Badowski, D., Krawczyk, S., Mueller Wiesemann, L., Spurlark, R. S., Webber-Ritchey, K. J., & Lee, Y.-M. (2022). US Nurses’ Challenges with Personal Protective Equipment during COVID-19: Interview Findings from the Frontline Workforce. Psych, 4(2), 226-237. https://doi.org/10.3390/psych4020019