Orthogonal Space-Time Bluetooth System for IoT Communications

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Related Work

1.2. Contributions

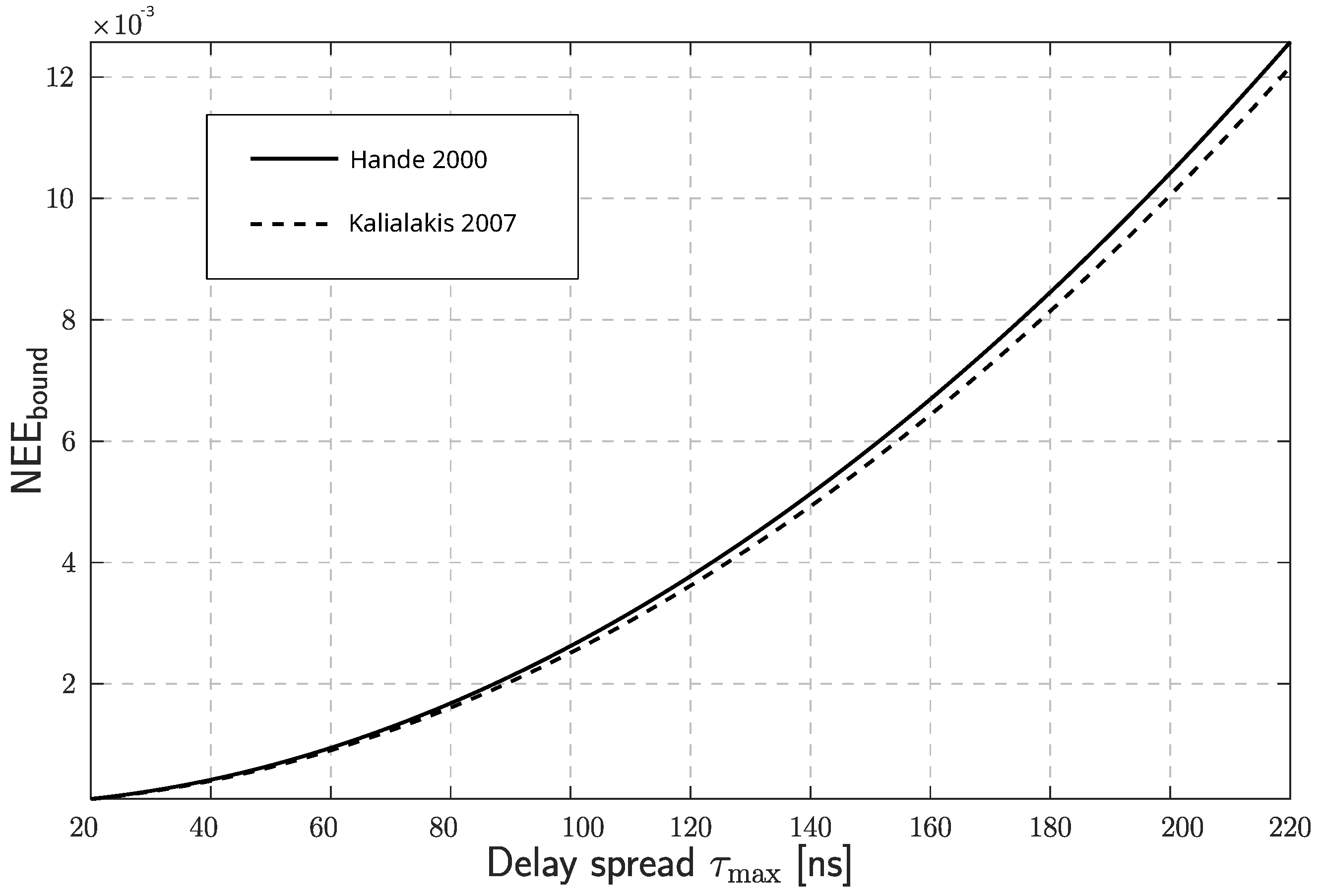

- A formal justification for the flat fading channel assumption in BLE communications is provided.

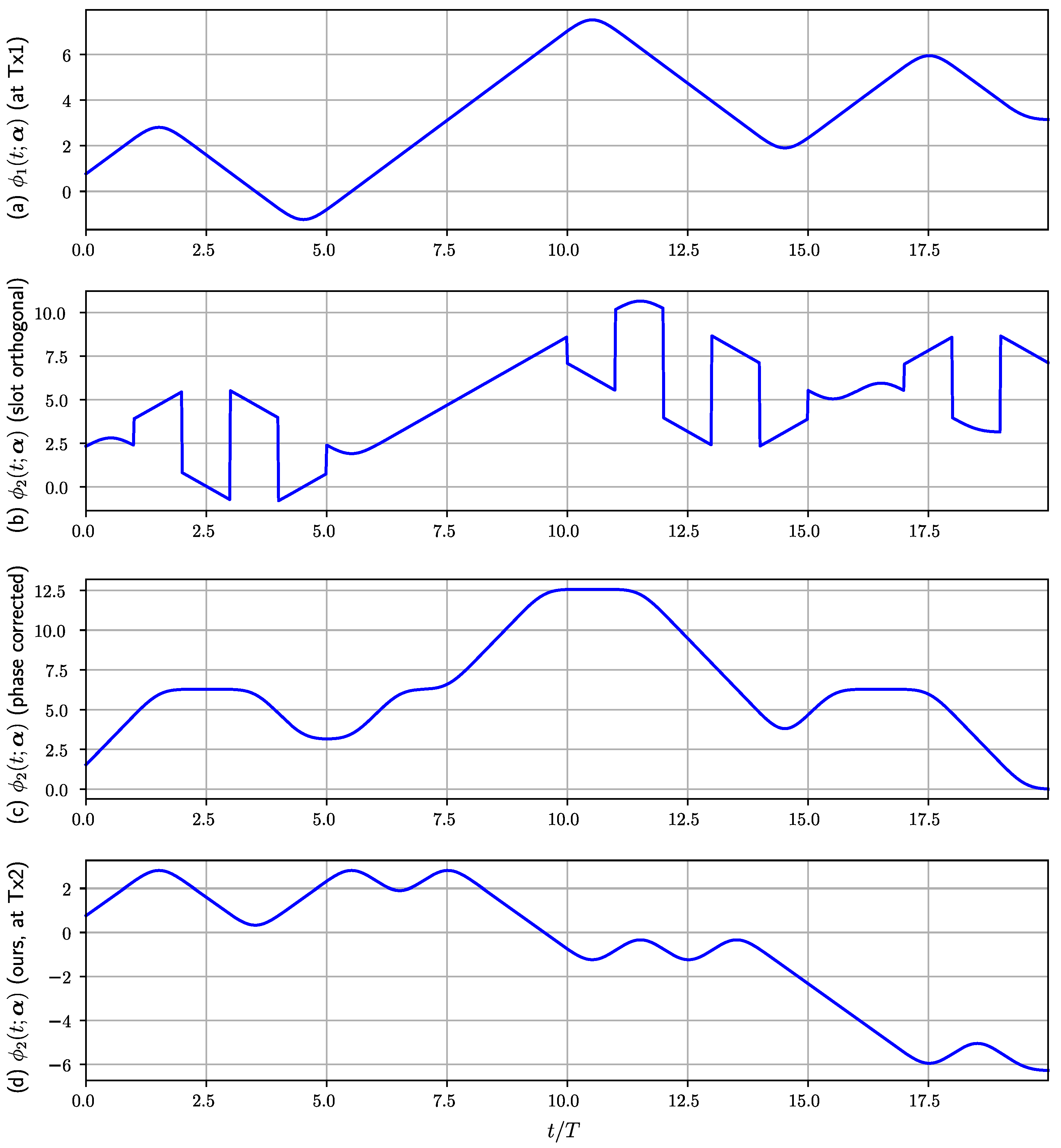

- A new OST-GFSK transmission strategy that maintains phase continuity is proposed.

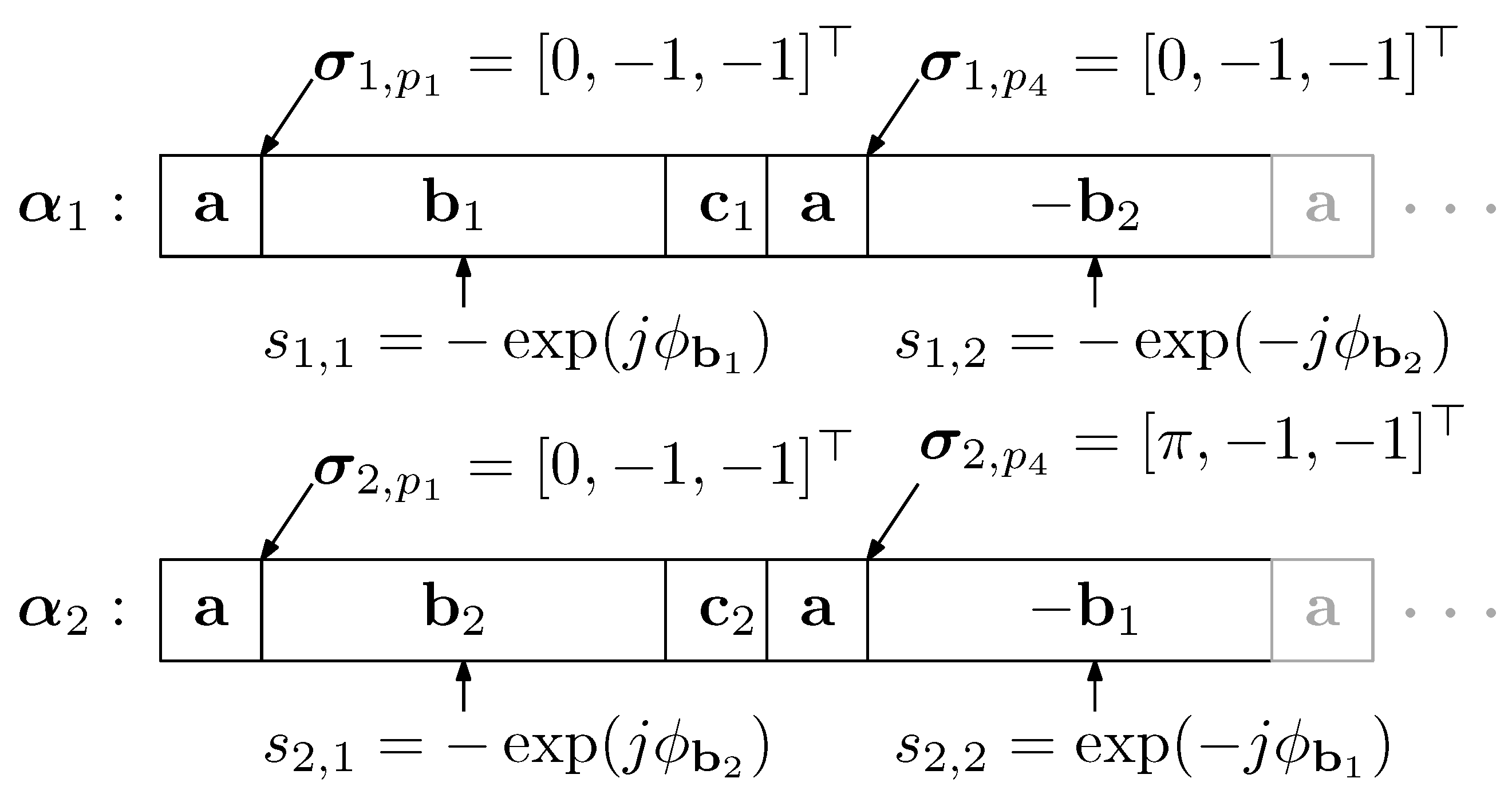

- A novel data frame format is introduced that achieves orthogonality between transmitted signals, enabling effective use of MIMO techniques.

- The design of a low-complexity signal combiner to optimize receiver performance is proposed.

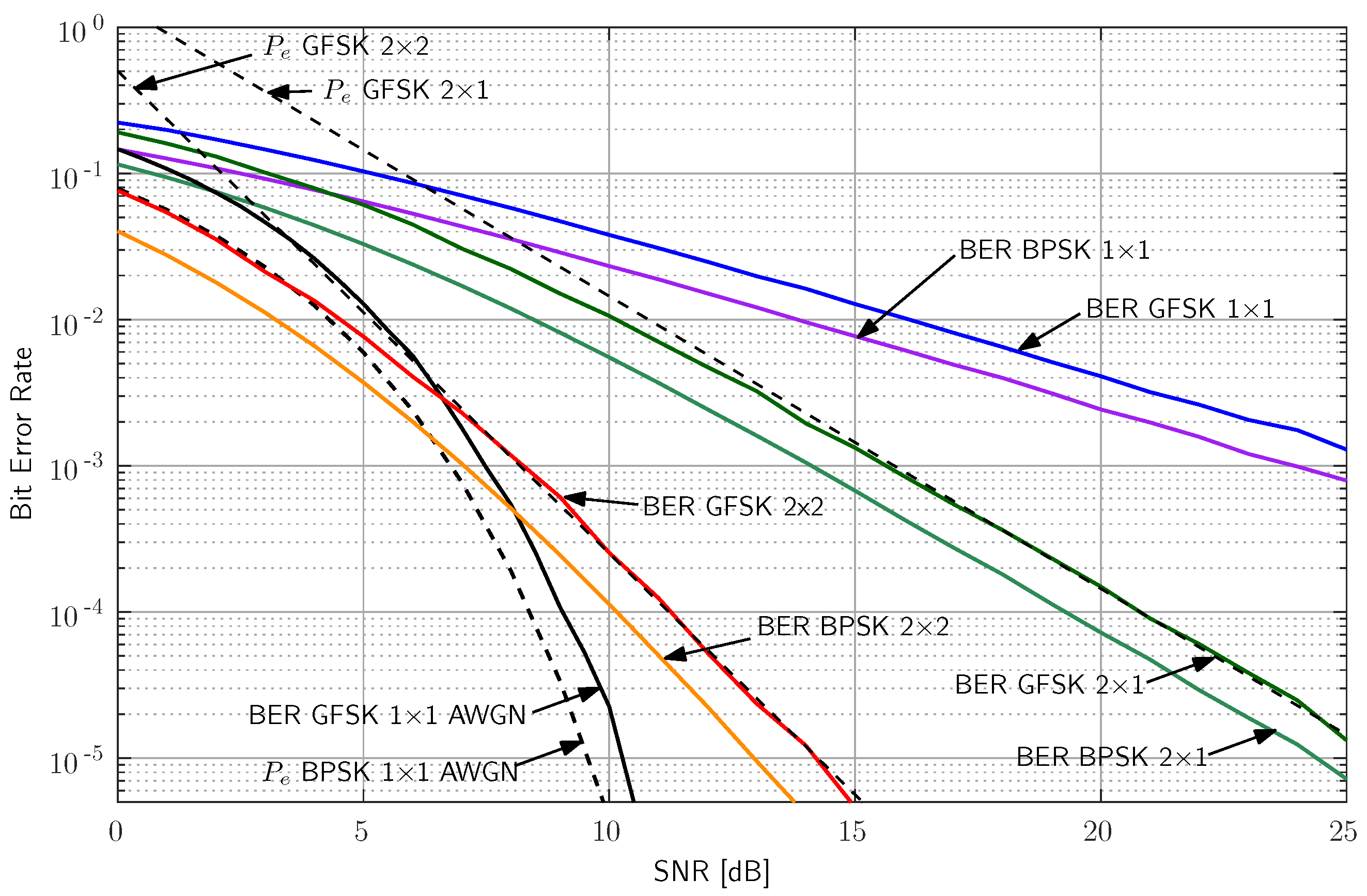

- Theoretical analysis of the bit error rate (BER) performance under Rayleigh fading channels is provided, supported by simulation results demonstrating comparable performance to linear modulation schemes under similar conditions.

2. BLE Preliminaries

2.1. Signal Model

2.2. Channel Model

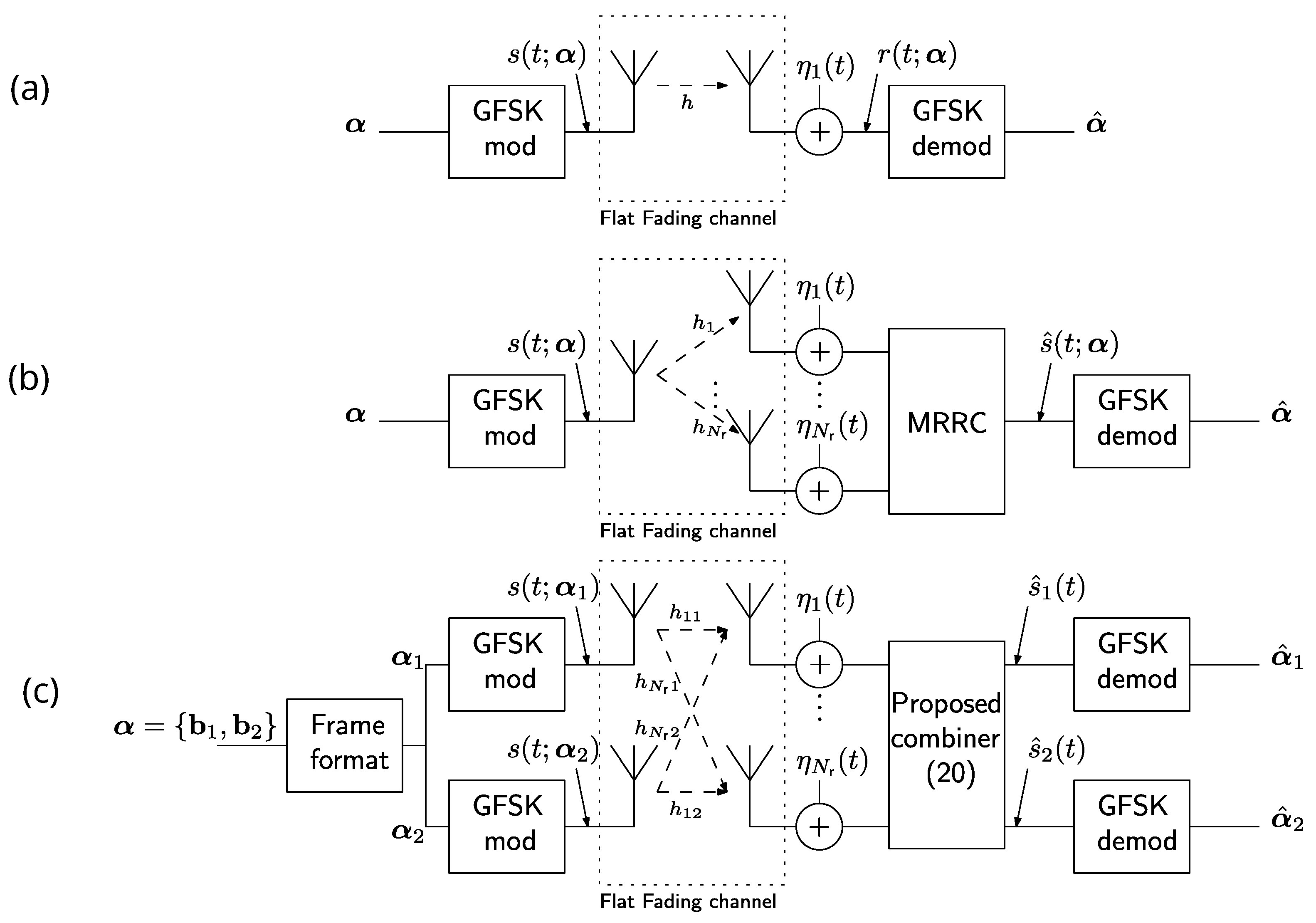

2.3. SISO System Model

3. GFSK SIMO Maximal-Ratio Receive Combining

4. Orthogonal Space-Time GFSK MIMO Communications

4.1. OST-GFSK Transmitter

- : in this case, such that leading to .

- : in this case, such that leading to .

- : in this case, such that leading to .

- : in this case, such that leading to .

4.2. OST-GFSK Receiver

4.3. OST-GFSK Receiver

5. Theoretical BER Performance

6. Simulation Results

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mansour, M.; Gamal, A.; Ahmed, A.I.; Said, L.A.; Elbaz, A.; Herencsar, N.; Soltan, A. Internet of things: A comprehensive overview on protocols, architectures, technologies, simulation tools, and future directions. Energies 2023, 6, 3465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collotta, M.; Pau, G.; Talty, T.; Tonguz, O.K. Bluetooth 5: A Concrete Step Forward toward the IoT. IEEE Commun. Mag. 2018, 56, 125–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foschini, G.J. Layered space-time architecture for wireless communication in a fading environment when using multi-element antennas. Bell Labs Tech. J. 1996, 1, 41–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alamouti, S. A simple transmit diversity technique for wireless communications. IEEE J. Sel. Areas Commun. 1998, 16, 1451–1458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarokh, V.; Jafarkhani, H.; Calderbank, A. Space-time block codes from orthogonal designs. IEEE Trans. Inf. Theory 1999, 45, 1456–1467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bluetooth SIG. The Bluetooth Core Specification, v4.2; Bluetooth SIG: Kirkland, WA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Kaleh, G.K. Simple coherent receivers for partial response continuous phase modulation. IEEE J. Sel. Areas Commun. 1989, 7, 1427–1436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Dhahir, N.; Saulnier, G. A high-performance reduced-complexity gmsk demodulator. IEEE Trans. Commun. 1998, 46, 1409–1412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svensson, A.; Sundberg, C.; Aulin, T. A class of reduced-complexity viterbi detectors for partial response continuous phase modulation. IEEE Trans. Commun. 1984, 32, 1079–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Giannakis, G. Reduced complexity receivers for layered space-time CPM. IEEE Trans. Wirel. Commun. 2005, 4, 574–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez-Pérez, A.; Aldana-López, R.; Longoria-Gandara, O.; Valencia-Velasco, J.; Pizano-Escalante, L.; Parra-Michel, R. Modular arithmetic CPM for SDR platforms. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. II Express Briefs 2022, 69, 2111–2115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldana-López, R.; Valencia-Velasco, J.; Longoria-Gandara, O.; Vazquez-Castillo, J.; Pizano-Escalante, L. Efficient optimal linear estimation for CPM: An information fusion approach. IEEE Internet Things J. 2024, 11, 8427–8439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Xia, X.-g. Orthogonal space-time coding for CPM system with fast decoding. In Proceedings of the 2002 IEEE International Conference on Communications, Conference Proceedings, ICC 2002 (Cat. No.02CH37333), New York, NY, USA, 28 April–2 May 2002; Volume 3, pp. 1788–1792. [Google Scholar]

- Aygölü, Ü; Çelebi, M.E. Space-time msk codes for quasi-static fading channels. AEU Int. J. Electron. Commun. 2004, 58, 268–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Fitz, M. Soft-output demodulator in space-time-coded continuous phase modulation. IEEE Trans. Signal Process. 2002, 50, 2589–2598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xian, L.; Punnoose, R.; Liu, H. Simplified receiver design for STBC binary continuous phase modulation. IEEE Trans. Wirel. Commun. 2008, 7, 452–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Telemetry Group, Range Commanders Council. IRIG-106 Telemetry Standards; Telemetry Group, Range Commanders Council: White Sands Missile Range, NM, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Josephson, C.; Perrins, E.; Rice, M. Space–time block-coded artm cpm for aeronautical mobile telemetry. IEEE Trans. Aerosp. Electron. Syst. 2022, 58, 342–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silvester, A.-M.; Schober, R.; Lampe, L. Burst-based orthogonal ST block coding for CPM. In Proceedings of the IEEE Global Telecommunications Conference, GLOBECOM ’05, St. Louis, MO, USA, 28 November–2 December 2005; Volume 5, pp. 5–3163. [Google Scholar]

- Pancaldi, F.; Barbieri, A.; Vitetta, G.M. Space-time block codes for noncoherent cpfsk. IEEE Trans. Wirel. Commun. 2010, 9, 1729–1737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hekrdla, M. A constellation space dimensionality reduced sub-optimal receiver for orthogonal stbc cpm modulation in a mimo channel. Acta Polytech. 2009, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arunkumar, K.P.; Murthy, C.R. Orthogonal delay scale space modulation: A new technique for wideband time-varying channels. IEEE Trans. Signal Process. 2022, 70, 2625–2638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hande, P.; Tong, L.; Swami, A. Flat fading approximation error. IEEE Commun. Lett. 2000, 4, 310–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedayat, A.; Nosratinia, A. Outage and diversity of linear receivers in flat-fading mimo channels. IEEE Trans. Signal Process. 2007, 55, 5868–5873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalialakis, C. Improved approximation error bounds when modeling WLAN signals in flat fading channels. IEICE Electron. Express 2007, 4, 351–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soltanian, A.; Van Dyck, R. Performance of the bluetooth system in fading dispersive channels and interference. In Proceedings of the GLOBECOM’01, IEEE Global Telecommunications Conference (Cat. No.01CH37270), San Antonio, TX, USA, 25–29 November 2001; Volume 6, pp. 3499–3503. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, W.; Durisi, G.; Koch, T.; Polyanskiy, Y. Block-fading channels at finite blocklength. In The Tenth International Symposium on Wireless Communication Systems (ISWCS 2013); VDE Verlag: Berlin, Germany, 2013; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Behnamfar, F.; Alajaji, F.; Linder, T. Channel-optimized quantization with soft-decision demodulation for space–time orthogonal block-coded channels. IEEE Trans. Signal Process. 2006, 54, 3935–3946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valencia-Velasco, J.; Longoria-Gandara, O.; Aldana-Lopez, R.; Pizano-Escalante, L. Low-complexity maximum-likelihood detector for iot ble devices. IEEE Internet Things J. 2020, 7, 4737–4745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson John, A.T.; Carl, S. Digital Phase Modulation; Springer Science & Business Media: New York, NY, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Tse, D.; Viswanath, P. Fundamentals of Wireless Communication; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

| Reference | Mod. Family | Orthogonality | Cont. Phase | Tx × Rx | Tailored to GFSK |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [4] | Linear | Exact | No | 2 × | No |

| [5] | Linear | Exact | No | No | |

| [13] | CPM | Exact | Yes | 2 × 1 | No |

| [14] | MSK | Exact | Yes | 2 × 1 | No |

| [19] | CPM | Exact | Yes | 2 × | No |

| [21] | CPM | Exact | Yes | 2 × | No |

| [16] | CPM | Approx. | Yes | 2 × 1 | No |

| [15] | CPM | No | Yes | 2 × | No |

| [18] | CPM | Exact | Yes | 2 × | No |

| This proposal | GFSK | Exact | Yes | 2 × | Yes |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Aldana-López, R.; Longoria-Gandara, O.; Valencia-Velasco, J.; Vázquez-Castillo, J.; Pizano-Escalante, L. Orthogonal Space-Time Bluetooth System for IoT Communications. IoT 2026, 7, 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/iot7010002

Aldana-López R, Longoria-Gandara O, Valencia-Velasco J, Vázquez-Castillo J, Pizano-Escalante L. Orthogonal Space-Time Bluetooth System for IoT Communications. IoT. 2026; 7(1):2. https://doi.org/10.3390/iot7010002

Chicago/Turabian StyleAldana-López, Rodrigo, Omar Longoria-Gandara, Jose Valencia-Velasco, Javier Vázquez-Castillo, and Luis Pizano-Escalante. 2026. "Orthogonal Space-Time Bluetooth System for IoT Communications" IoT 7, no. 1: 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/iot7010002

APA StyleAldana-López, R., Longoria-Gandara, O., Valencia-Velasco, J., Vázquez-Castillo, J., & Pizano-Escalante, L. (2026). Orthogonal Space-Time Bluetooth System for IoT Communications. IoT, 7(1), 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/iot7010002