1. Introduction

Recent developments in wearable and implantable devices—ranging from clinical-grade monitors to consumer health trackers—have transformed healthcare delivery models. Continuous and remote health data collection offers numerous benefits, including increased patient comfort, improved safety through early risk detection, and reduced healthcare costs [

1]. Moreover, health devices enable continuous, non-invasive monitoring of physiological parameters, such as heart rate, oxygen saturation, and glucose levels, as well as environmental conditions, such as temperature and humidity. This shift enables healthcare to extend beyond clinical settings, supporting patient monitoring at home, in the community, or in outdoor environments.

Health devices and wearables form the foundation of the Internet of Medical Things (IoMT), a specialised domain within the broader Internet of Things (IoT) [

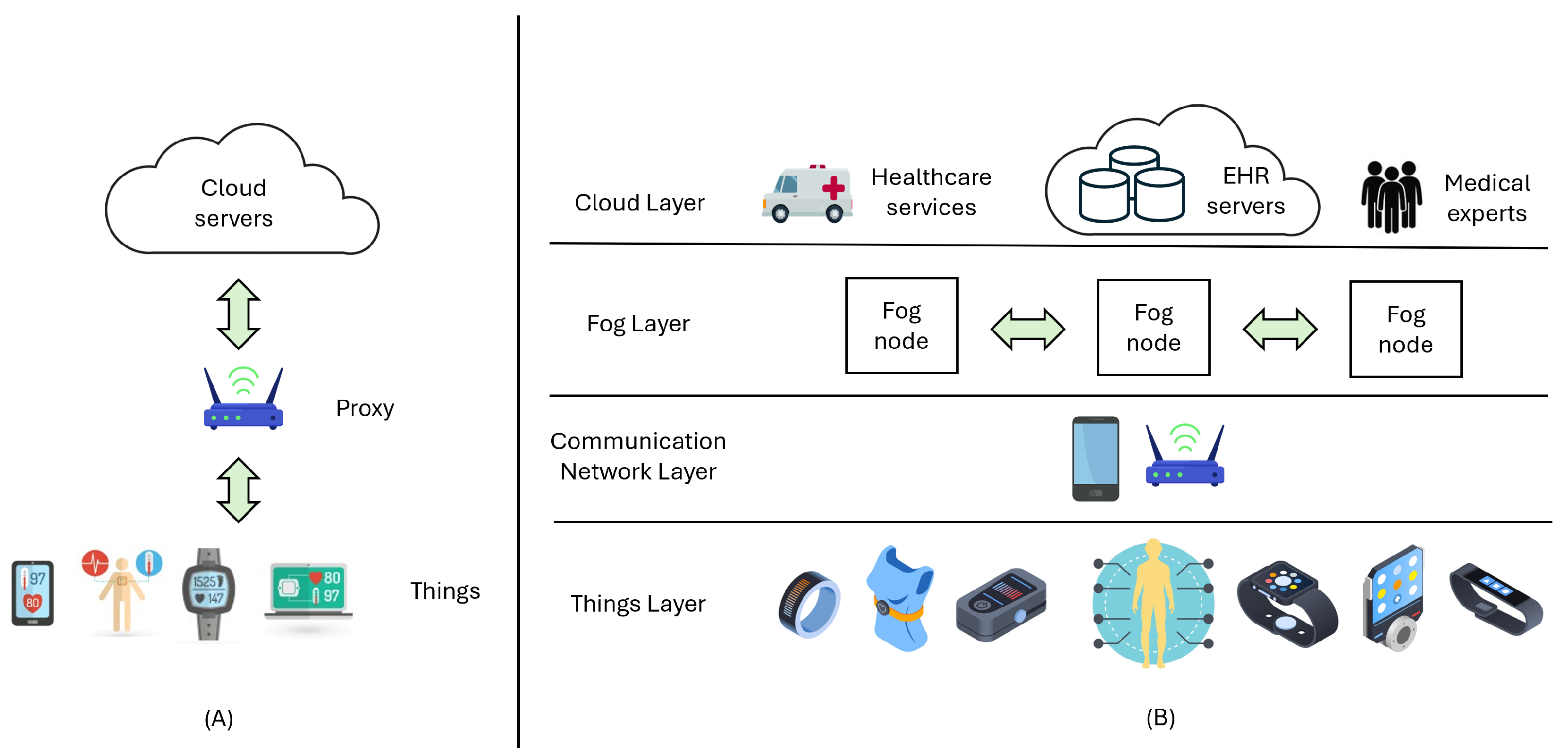

2]. The IoMT architecture typically consists of sensors that transmit data to centralised cloud-based systems—often via intermediate gateways—for storage and processing (

Figure 1A) [

3]. These systems interface with platforms, such as electronic health records (EHRs), enabling clinical integration.

While cloud-centric approaches benefit from centralised data aggregation, they introduce limitations for latency-sensitive applications such as home-monitoring programmes for patients with heart failure or early detection of respiratory deterioration in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), where rapid anomaly detection is essential. These applications require low latency, continuous availability, and efficient resource usage, even in environments with intermittent connectivity.

Moreover, as IoMT adoption grows, system scalability becomes increasingly complex [

4]. Devices vary widely in communication protocols, data formats, and transmission frequencies, depending on their capabilities and clinical purpose. Some high-frequency sensors, such as ECG and pulse oximeters, can send data every 100 ms to 1 s (1–10 Hz), whereas others, for instance blood pressure monitors or smartwatches, typically transmit data at longer intervals (0.1–1 Hz), often due to battery constraints.

The resulting challenges—high data volume, device heterogeneity, and velocity—exceed the capabilities of traditional cloud-only architectures. Fog computing (FC) is a promising alternative that introduces intermediary processing nodes between the cloud and IoMT devices (

Figure 1B) [

5]. These fog nodes allow real-time data preprocessing, local risk detection, and reduced latency and bandwidth usage by only transmitting relevant information to the cloud.

Latency and device interoperability requirements are major unresolved challenges for IoMT [

6,

7,

8]. Our proposal seeks to address these issues by combining the deployment of containerised Fog nodes, which move data processing and storage closer to the patient, shortening response time in latency-sensitive applications, and enabling the integration of heterogeneous devices via standardised data schemes.

This study proposes an FC architecture for IoMT-based remote patient monitoring that leverages the strengths of graph-based databases for managing complex and highly connected health data structures. By deploying computation and storage closer to the point of care, fog nodes reduce cloud dependency and support timely detection of risk events. When anomalies are detected, these nodes trigger alerts and forward summaries to cloud platforms for integration into patient EHR.

A proof-of-concept fog node with modest resources was implemented, and its performance in receiving real-time health data from multiple patients was evaluated. The primary contribution of this work is the development of a scalable, lightweight fog-based monitoring model that showcases the feasibility of real-time data management in massive patient-device networks using graph databases.

Related Work

The adoption of IoMT systems introduces critical challenges in terms of interoperability, data privacy, infrastructure requirements, and cost [

9]. The secure and confidential transmission of personal health data is essential for building patient trust and ensuring regulatory compliance. Additionally, the diversity of manufacturers and communication protocols complicates device integration and system scalability.

Several studies have proposed fog and edge computing models to decentralise data processing to address these issues. For example, Alam et al. [

10] integrated blockchain technology into a fog-based IoMT architecture, with fog nodes functioning as blockchain miners to ensure data integrity and traceability. Although the blockchain adds a security layer, it introduces additional computational overhead.

Asghar et al. [

11] proposed a fog-based patient monitoring system that reduces latency and network load using a dynamic load-balancing algorithm. Each IoMT device is assigned to the least-congested fog node, optimising resource distribution. However, their study focused on device-node allocation strategies and does not analyse fog node performance under increasing data load.

Other approaches use edge computing, which processes data directly at the sensor or device level [

12]. Although this can further reduce latency, edge nodes are typically deployed on-site and have limited scalability when monitoring multiple patients simultaneously [

13]. Mukherjee et al. [

14] proposed a multilayer edge fog cloud architecture to balance energy consumption and processing efficiency. Their framework analyses patient mobility to recommend nearby care centres, highlighting the advantages of layered infrastructures.

In parallel, several studies have explored the use of graph databases (GDBs) in biomedical domains. Monteiro et al. [

15] evaluated the performance of four GDBs—JanusGraph, Nebula Graph, Neo4j, and TigerGraph—across memory usage, execution time, and CPU load. Lopes et al. [

16] expanded this evaluation by including Memgraph and emphasised scalability under increasing data volumes. Both studies conclude that Neo4j offers a favourable trade-off between performance and flexibility. GDBs have been applied in various healthcare contexts, including modelling patient data structures [

17,

18], construction of diagnostic and treatment knowledge graphs [

19], simulation of inter-organ interactions [

20], identifying drug-drug interactions [

21], and epidemiological analyses of hospital-acquired infections [

22]. These applications demonstrate the adaptability of GDBs to complex medical data and support their suitability as part of IoMT systems for real-time monitoring and event detection.

Related work highlights the relevance of IoMT and the application of FC models in these settings. Nevertheless, most of the contributions focus on particular issues, such as security or resource optimisation, disregarding scalability or real-time performance. On the other hand, approaches implementing GDBs in healthcare do not have continuous patient monitoring as a use case. Our proposal represents a novel contribution by focusing the application of FC-based IoMT on real-time monitoring scenarios where latency, scalability, and Fog node performance issues are crucial. The use of Neo4j to store and process large volumes of data in real time also represents an innovative contribution, since this type of database has not been evaluated in such critical scenarios in terms of data volume, transmission frequency, and response time.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Four-Layer IoMT Architecture

The proposed remote patient monitoring system is structured as a four-layer architecture to support IoMT. These layers include sensing, communication, fog computing, and cloud computing (

Figure 1B). The sensing layer comprises the physical devices—such as physiological sensors, controllers, and actuators—deployed at the point of care. These “medical things” continuously capture patient health data (e.g., heart rate and glucose levels) and relevant environmental parameters (e.g., temperature and air quality). Operating autonomously, they form the foundation of the monitoring system by interacting directly with patients and their surroundings.

The communication network layer ensures connectivity between sensing devices and higher-level systems. It typically relies on lightweight, low-power communication protocols such as Bluetooth, ZigBee, or WiFi, optimised for mobile and wearable applications. The aggregator, which can be implemented via a WiFi access point, smartphone, or dedicated gateway, is a central component in this layer. It consolidates data from multiple sensors and forwards it to the fog computing infrastructure.

The fog computing layer is the core of real-time data processing and decision-making. It consists of one or more fog nodes that can handle input from thousands of devices across multiple care points. These nodes store and process incoming data locally, enabling the early detection of critical events, such as health deterioration, sensor malfunctions, or anomalous patterns. When risks are identified, the system can trigger alerts to promptly notify patients, caregivers, or emergency services.

An additional responsibility of the fog layer is to prepare and forward relevant data to the cloud for EHR integration. Given the impracticality of transmitting raw high-frequency sensor data, fog nodes must perform data aggregation, summarisation, and formatting to distil actionable insights suitable for long-term storage and clinical review.

Finally, the cloud computing layer hosts centralised services provided by healthcare organisations. These may include EHR systems, analytics platforms, emergency response coordination, and regulatory compliance infrastructures. The cloud ensures data persistence, remote accessibility, and system-wide orchestration.

2.2. Graph-Based Database: Neo4j

The fog computing layer must be able to receive, store, and query high-frequency data streams in real time while maintaining low latency and high availability. To meet these demands, we propose using a GDB—specifically Neo4j [

23]—as the core data management engine within fog nodes. GDBs offer distinct advantages over traditional relational databases, particularly when modelling highly interconnected data structures, such as those found in healthcare monitoring systems [

24]. Unlike relational models that rely on fixed schemas and table joins, GDBs excel at capturing complex relationships and efficiently traverse data graphs. This enables rapid insight extraction and the discovery of implicit patterns—key capabilities for personalised medicine, contextual alerts, and anomaly detection.

Neo4j is a widely adopted, open-source GDB implemented in Java. It stores data as nodes (entities) and edges (relationships), with properties attached to both. It is ACID-compliant and ensures transactional reliability. Neo4j uses Cypher, a domain-specific query language optimised for graph operations. It enables expressive and intuitive data manipulation, allowing developers to efficiently model real-world interactions among patients, devices, events, and alerts.

The key features that make Neo4j particularly suited for fog-based IoMT systems include horizontal scalability, allowing seamless growth as new devices and patients are added; disk-based persistence, ensuring efficient and durable storage; intuitive user interface and developer-friendly environment that supports rapid prototyping and analysis; and efficient graph traversal algorithms, enabling the identification of complex patterns (e.g., symptom clusters, device correlations, temporal trends) that are computationally expensive in relational systems [

25,

26].

Given these capabilities, Neo4j is a strong candidate for real-time health monitoring within fog nodes, offering both the performance and flexibility required for scalable, data-intensive IoMT applications.

2.3. Secured Fog Nodes

Fog nodes in IoMT architectures face significant cybersecurity challenges because they process critical medical data. These nodes handle sensitive, real-time patient information and act as aggregation points between IoMT devices and cloud services. As intermediaries, they are prime targets for cyberattacks that can compromise healthcare data integrity, confidentiality, and availability in IoMT systems [

27].

When implementing security measures in fog nodes, balancing cybersecurity requirements with the latency and availability constraints of medical data is essential. Delays or interruptions in data availability can directly affect patient care quality.

A defining characteristic of IoMT systems is the decentralised distribution of fog nodes, which often operate with limited storage and computational resources. These conditions increase their vulnerability to attacks that target authentication, authorisation, or data privacy [

28]. Healthcare systems must comply with international regulatory frameworks such as HIPAA, GDPR, and ISO 27001 [

29] to mitigate such risks [

30,

31]. These frameworks recommend strategies, including comprehensive risk management, firewall deployment to secure communications with cloud services, and rigorous access control through identity and access management tools. For instance, implementing Role-Based Access Control (RBAC) ensures that only qualified medical personnel can access specific patient records, whereas Attribute-Based Access Control (ABAC) provides more granular control based on context (e.g., time of day or location) [

32]. They also emphasise the importance of encrypting stored and transmitted data, such as using Transport Layer Security (TLS) 1.3 for data in transit and the Advanced Encryption Standard (AES-256) [

33] for data at rest [

34], as well as deploying intrusion detection and anti-malware systems, and ensuring resilience through replication and backup mechanisms.

2.4. Implementation and Experimental Methodology

To evaluate the proposed fog-based IoMT architecture, we implemented a fog node and assessed its performance under various conditions. The experiments focused on latency, data throughput, and scalability—key factors in real-time patient monitoring applications.

2.4.1. Fog Node Implementation and Local Database

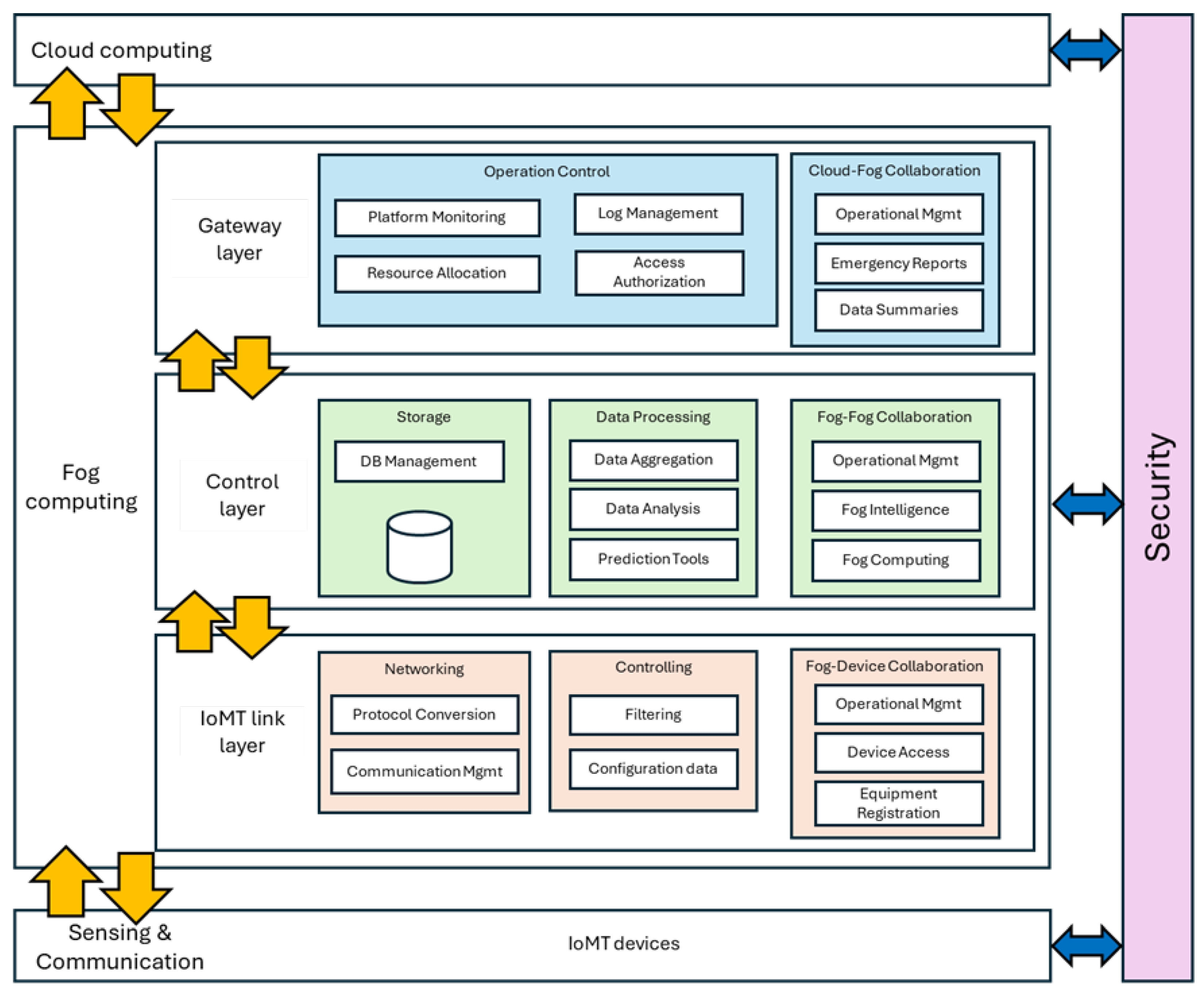

Fog node deployment was containerised to facilitate portability and simplify distribution. The fog node architecture comprises three internal layers: the IoMT link, control, and gateway layers (

Figure 2).

Containerisation of fog nodes provides multiple benefits with respect to cybersecurity. One of the most significant advantages is the ability to isolate services within independent containers. This allows critical services—such as ECG processing, blood glucose data analysis, and real-time medical alert management—to coexist on the same device without interfering with one another. Furthermore, service isolation enables the independent management of operational requirements, such as defining criticality levels, latency constraints, and compliance with specific regulatory standards.

Medical applications rely on specialised cryptographic libraries, communication protocols, such as HL7 FHIR [

35], and clinical data analytics frameworks. Containerisation simplifies version management, thereby avoiding conflicts between applications and libraries. In addition, container-based version control supports maintenance teams in detecting and correcting the use of libraries with known vulnerabilities, reducing the risk of cyberattacks that could exploit these weaknesses. Finally, access control remains a key consideration for services executed on fog nodes.

Containerisation facilitates the deployment of solutions that regulate access to different services hosted within containers. It also enhances traceability by generating independent log records for each container. These logs can be analysed by intrusion detection systems or leveraged during security audits, thus supporting compliance with applicable cybersecurity regulations and standards.

The IoMT link layer manages direct communication with the sensing devices. It collects data using various protocol drivers, performs initial filtering and integrity checks, and supports real-time bidirectional control. Given the heterogeneity of IoMT devices, this layer is designed to support multiple communication standards and device types. It also handles device registration, access control, and security, enabling the fog node to act as a versatile gateway.

The control layer houses the data persistence engine—Neo4j. Sensor data are aggregated and stored in a schema designed for efficient analysis and anomaly detection. This layer also enables local alert generation in response to risk events and supports inter-node services within the fog network, such as load balancing, failure detection, and routing strategies.

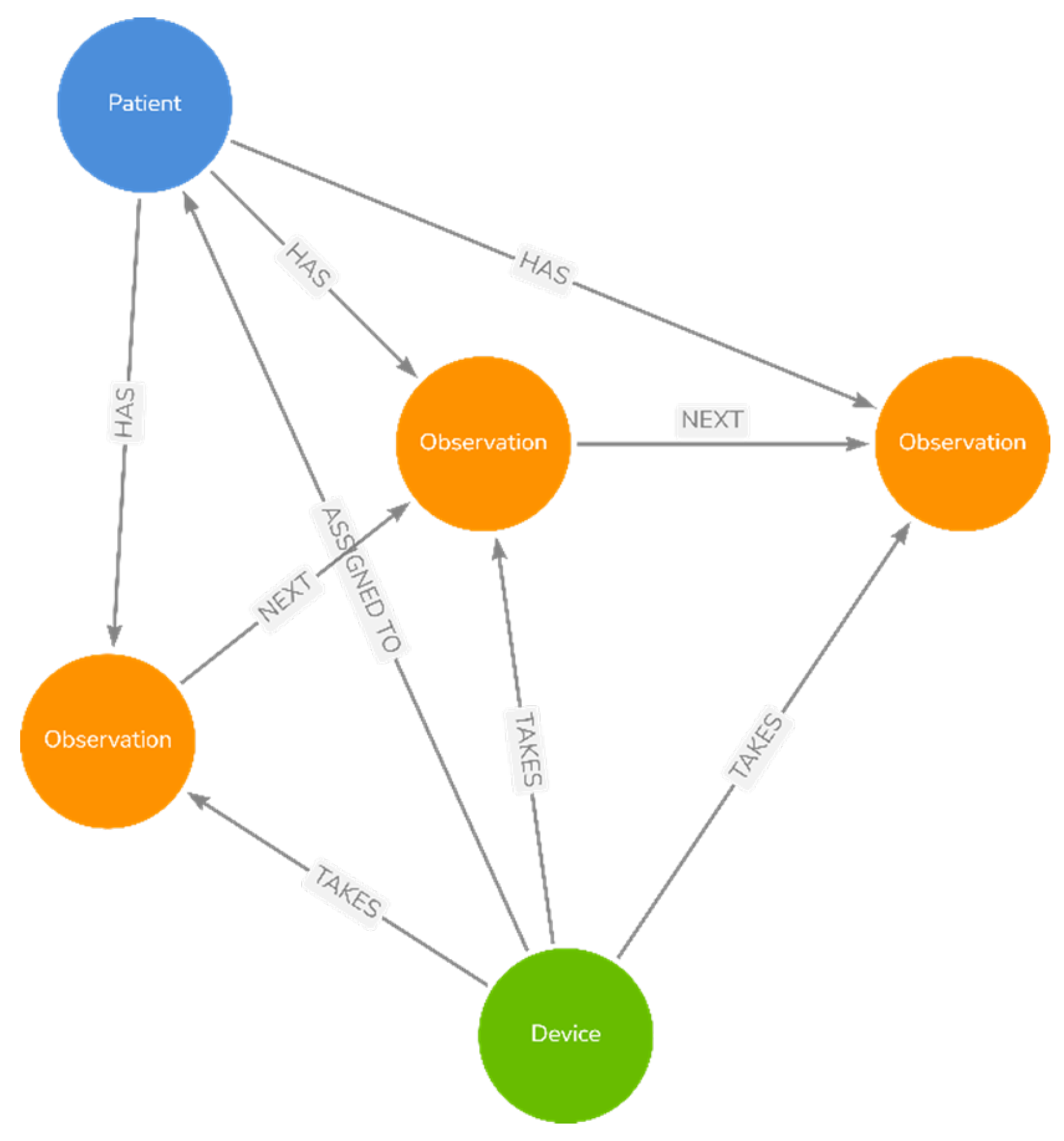

The data model includes three node types:

Patient with attributes such as ID, name, age, gender, and birthdate;

Device capturing sensor metadata, such as type, manufacturer, and operational status;

Observation representing individual measurements with timestamps and links to the corresponding patient and device.

Observations are chronologically connected to form time-series chains. The system supports five device categories: heart rate monitors (HRM), blood pressure monitors (BPM), glucose monitors (GM), temperature monitors (TM), and oxygen saturation monitors (OSM).

Figure 3 shows the data model and its relationships.

The gateway layer manages the overall operation of the fog node and facilitates communication with cloud services. It transmits summarised data and risk reports and serves as an interface through which cloud-based services can issue commands to IoMT devices.

2.4.2. Experimental Setup

The fog node was deployed on a modest single-node yet realistic hardware platform to test its practical feasibility. The setup involved running a single Neo4j database instance inside a container on a conventional laptop.

The hardware used in this evaluation was as follows:

Processor: Intel Core i7-9750H @ 2.60 GHz;

Memory: 32 GB DDR4 RAM;

Storage: 1 TB SSD;

Operating System: Windows 10 Pro (64-bit);

Software: Neo4j Enterprise Edition 5.20.0, Neo4j Desktop 1.6.0.

The use of Neo4j Desktop allowed flexible configuration and monitoring of database performance under different test conditions. This setup enabled the controlled evaluation of key performance metrics relevant to real-time healthcare environments.

2.4.3. Evaluation Methodology

The fog node’s ability to handle high-throughput and real-time processing under increasing workload conditions was evaluated. The following key factors were considered:

Data volume: IoMT systems continuously generate large volumes of physiological data;

Latency: Timely patient data access is critical for clinical decision-making;

Scalability: The system must accommodate a growing number of devices and patients;

Security and compliance: Although not the focus of this evaluation, regulatory requirements (e.g., HIPAA, GDPR) necessitate robust data protection mechanisms;

Interoperability: The seamless integration of cloud services and EHRs is essential.

Data volume handling, latency under load, and scalability were the primary focus. We simulated different numbers of IoMT devices transmitting data at different rates. CPU and memory usage were monitored under stress conditions, including high-frequency transmissions. The query latency was measured to determine the performance thresholds and identify potential bottlenecks.

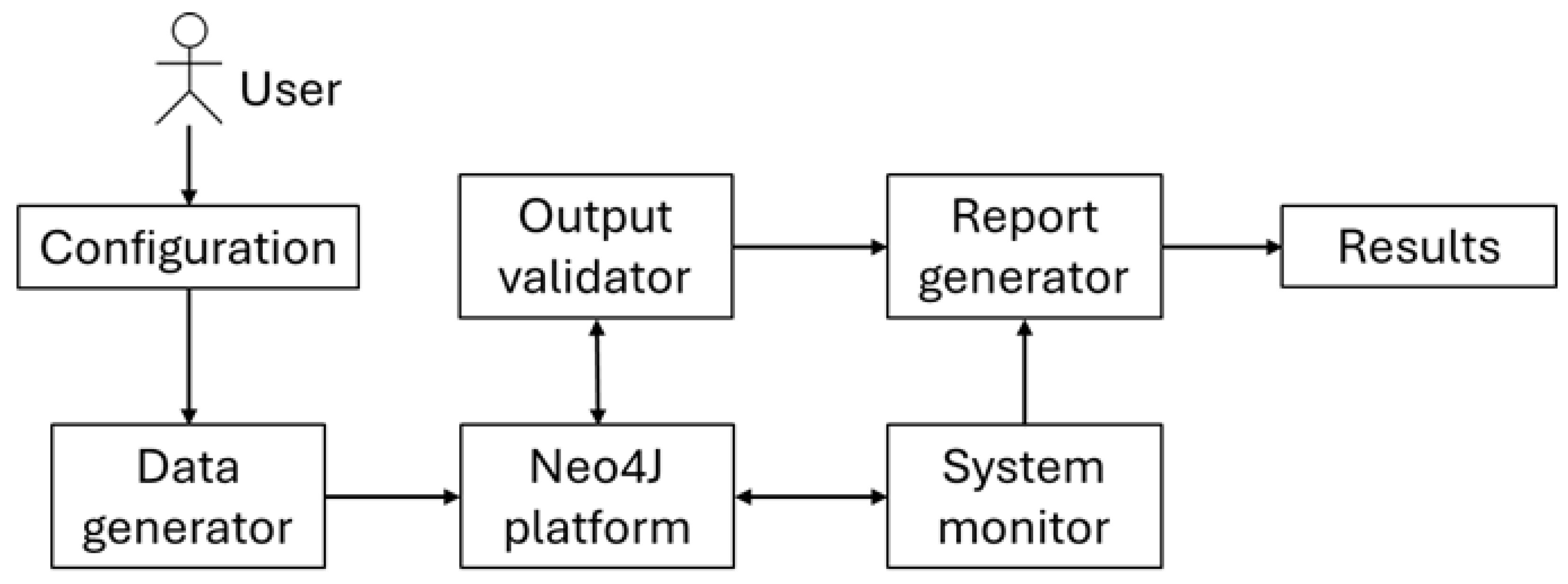

All simulations and performance measurements were conducted using Jupyter Notebook 2.17 with Python 3.13.9 scripts. These scripts executed Cypher queries, retrieved and analysed data, and recorded performance metrics in real time. To simulate real-world scalability, multithreading was used to generate concurrent data streams. The resource consumption was monitored throughout the experiments.

Figure 4 illustrates the experimental process.

2.4.4. Experimental Scenarios

Eleven experimental scenarios were simulated, each defined by a different number of IoMT devices (

Table 1). Each device generated 1000 observations in each scenario. All relevant Patient and Device nodes were created in the Neo4j database before simulation, and appropriate relationships were established between them.

Data transmission frequency varies in healthcare applications—from every 100 ms in continuous monitoring devices (e.g., ECG, pulse oximeters) to several seconds. Our simulations covered transmission rates from 5 to 0.1 s, capturing a spectrum of clinical use cases and enabling system performance evaluation under variable data ingestion loads.

With the aim of using real data in the experiments, the BIG IDEAs Lab Glycemic Variability and Wearable Device Data (version 1.1.2), freely available on PhysioNet repository [

36] was utilised. It includes physiological data (e.g., tri-axial accelerometry, electrodermal activity, temperature, etc.) collected by wearable devices from individuals (9 women and 7 men) aged 35–65 years with elevated glucose levels, ranging from normal to pre-diabetic during 10 days. The following variables were used: interstitial glucose concentration (mg/dL), skin temperature (ºC), heart rate (beats per minute), blood pressure (mmHg), and oxygen saturation (%). The data files contained a two-column frame format with the timestamp in the first column and the related measured values in the second one. The data did not require any preprocessing to be used in the experiments.

2.4.5. Performance Metrics

Three key performance indicators were assessed in each scenario (

Table 2):

- 1.

Average CPU usage;

- 2.

Memory footprint;

- 3.

Query execution latency.

After data ingestion was completed for each scenario, five distinct Cypher queries were executed on the Neo4j database (

Table 3). These queries were designed to test retrieval speed and database responsiveness. The query latency was recorded as the primary performance metric.

CPU and memory metrics provide insight into the scalability and resource use of the system. Latency measures the system’s ability to respond to clinical queries in real time. The acceptable latency for patient monitoring systems typically ranges from 500 ms to 2 s.

3. Results

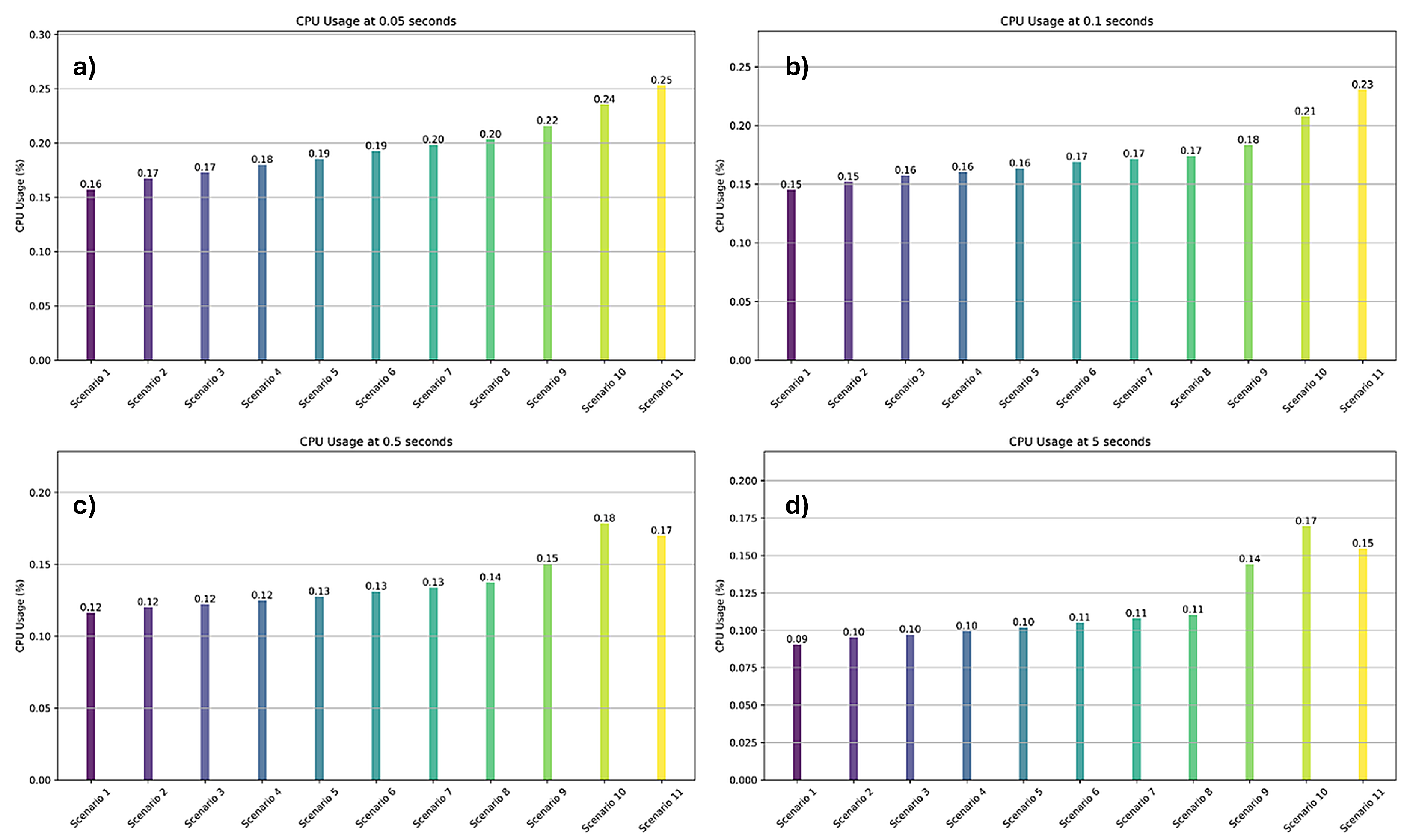

3.1. CPU Usage

Figure 5 illustrates the average CPU usage across the 11 scenarios, showing the performance under varying device counts and data rates. Even in the most demanding configuration (Scenario 11 with 12,500 devices transmitting every 0.05 s), Neo4j maintained CPU usage under 0.25% of the system capacity.

The CPU load increased with the transmission frequency, confirming that higher update rates require greater processing power. This test range (5–0.05 s intervals) helped identify optimal update frequencies that balance real-time responsiveness and resource efficiency.

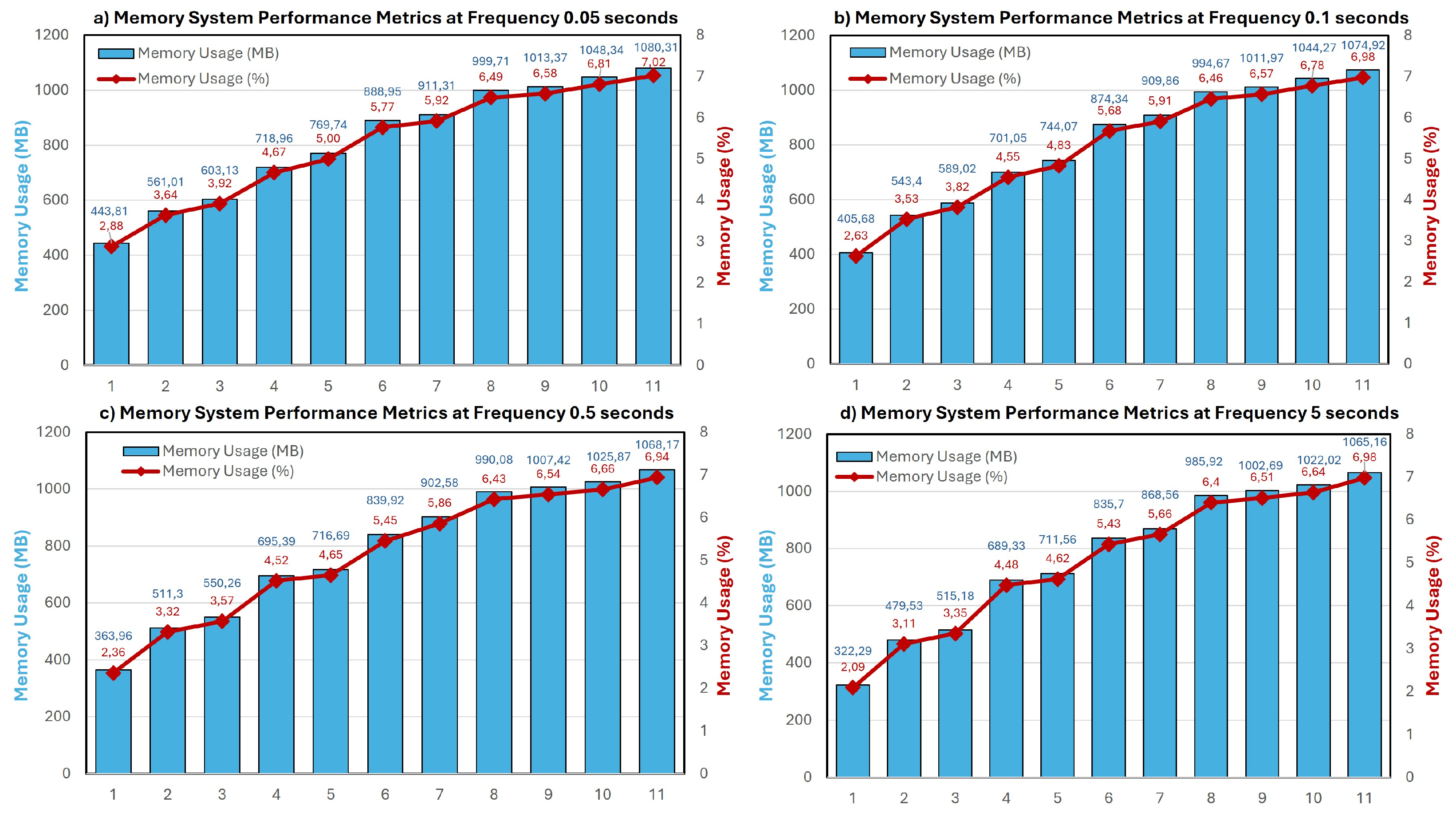

3.2. Memory Footprint

Figure 6 shows the memory consumption measured in megabytes and as a percentage of the total RAM. As expected, the memory usage scaled with the number of devices and transmission frequency. Higher ingestion rates require more memory to buffer and process data within a shorter time window.

This scaling behaviour highlights the system’s temporary memory demands under high-throughput conditions and informs real-world memory allocation planning.

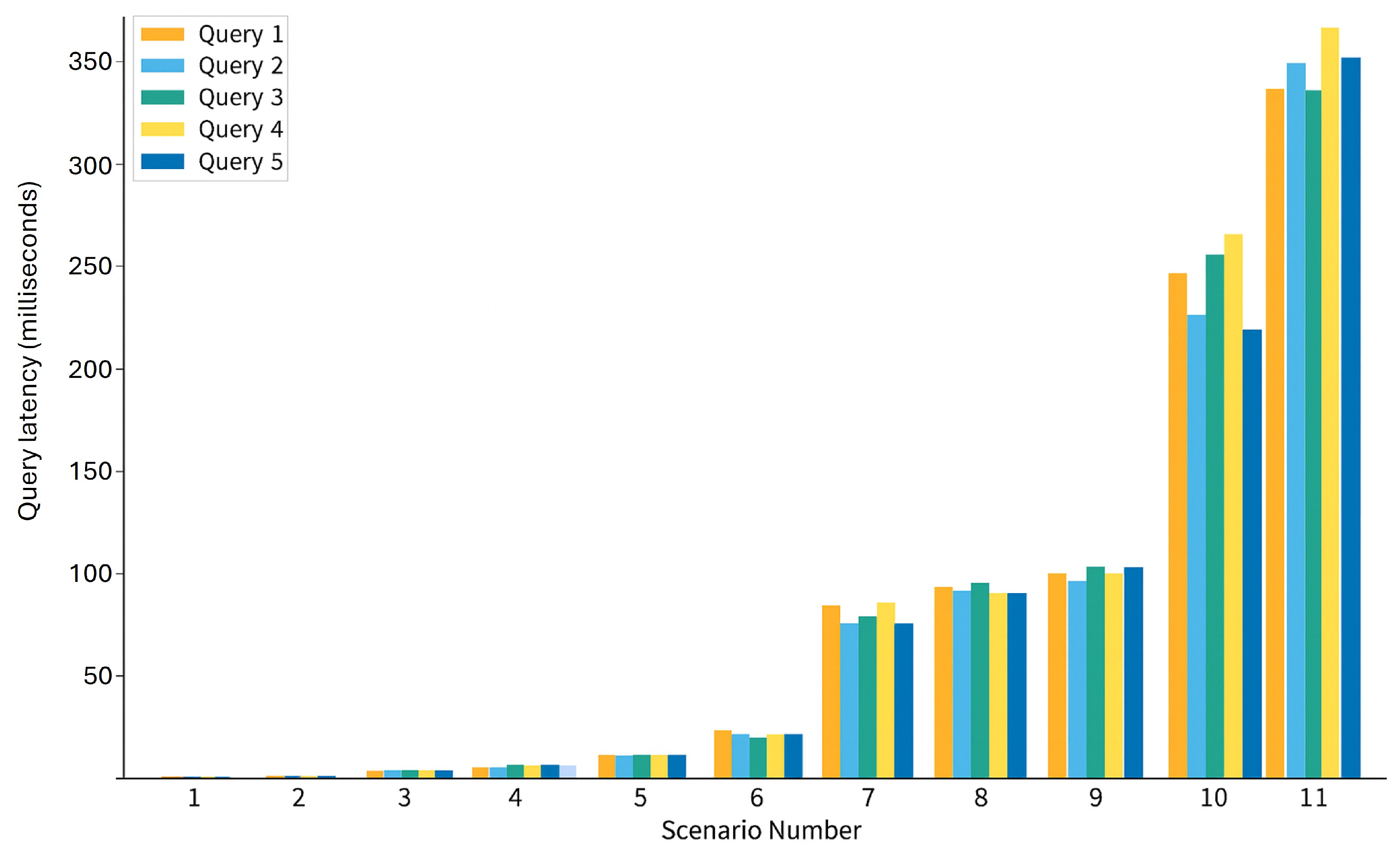

3.3. Latency of the Query Execution

Table 4 and

Figure 7 present the results of query latency. The query execution time increased with the dataset size across all scenarios. The latency increased by up to two orders of magnitude between Scenarios 1 and 11. This is expected given that scenario 1 has 5000 stored nodes and scenario 11 has 12 million nodes. This increase in nodes and relationships is responsible for the increased response time of Neo4j. Nevertheless, all queries were executed in less than 500 ms, meeting the latency requirements for real-time clinical applications.

Interestingly, the latency remained consistent across all five queries within each scenario, indicating that data volume primarily influenced performance but not query complexity. This consistency indicates stable and predictable system behaviour, a crucial attribute for time-sensitive healthcare environments.

These results demonstrate the feasibility of using Neo4j as the core data engine in fog-based IoMT architectures, even under substantial workloads. Maintaining low latency and stable resource use ensures reliable operation for continuous remote monitoring systems, especially in critical care settings where real-time data access is vital.

4. Discussion and Conclusions

The convergence of medical devices, communication technologies, and modern data infrastructure has made remote patient monitoring a transformative pillar of healthcare. However, deploying such systems at a scale—across thousands of patients and IoMT devices—demands robust, low-latency, and scalable storage systems.

Fog computing addresses these challenges by bringing computation closer to the data source. Fog nodes reduce network load, minimise latency, and enable near-instantaneous reactions to critical health events. Such nodes must reliably collect, process, and store real-time data from tens of thousands of heterogeneous devices operating at different frequencies.

This study evaluated Neo4j as the core data engine for fog nodes in healthcare IoMT environments. Simulations involving increasing numbers of devices and varying transmission rates were used to assess CPU usage, memory consumption, and query latency.

The results demonstrated Neo4j’s strong scalability and efficiency, handling millions of observations and complex node relationships with minimal resource use. The low query latency (<500 ms) even in extreme scenarios involving over 12,000 devices transmitting data every 50 ms supports Neo4j’s suitability for supporting real-time triage in home-monitoring programmes for patients with heart failure, continuous gait and tremor tracking in Parkinson’s disease, or early detection of respiratory deterioration in COPD, where rapid anomaly detection is essential. Additionally, Neo4j demonstrated consistent response times even as query complexity increased, a highly relevant factor when aiming to identify patterns and risk events in highly correlated health data. Given Neo4j’s versatility as a healthcare data warehouse, future work will explore the deployment of ML algorithms for the automated exploitation of monitoring data.

The resource consumption remained well below the critical thresholds, highlighting the appropriateness of this approach for Fog nodes running on modest hardware with Neo4j. This finding indicates that this architecture could run on cost-effective Fog nodes placed in community clinics, emergency transport units, or long-term care facilities without requiring specialised hardware.

In summary, our work represents a novel and promising approach that combines FC and Neo4j to meet IoMT environments’ latency and real-time data ingestion requirements. Furthermore, the use of Neo4j to store and process large volumes of data in real time also represents an innovative contribution, since this type of database has not been evaluated in such critical scenarios in terms of data volume, transmission frequency, and response time. Finally, the observed low resource consumption makes this approach suitable for large-scale, population-level deployments.

Limitations and Future Work

This work represents an initial exploration of the application of Neo4j in fog-based remote patient monitoring systems and has several limitations:

Scope of simulation: Although extensive, the simulations focused on realistic transmission rates and device counts. Future studies should test larger-scale deployments and higher data frequencies;

Schema complexity: The data model used was intentionally simple. Although this allowed us to isolate performance metrics under controlled conditions, it does not fully reflect the complexity of real-world clinical graphs. Future assessments should incorporate richer schemas, even those based on medical ontologies, to validate Neo4j’s performance under more heterogeneous and densely connected data;

Query complexity: The evaluation focused on basic Cypher queries. Advanced graph operations, such as multi-hop traversals and pattern matching, should be explored in future research to assess the system’s analytical depth;

Hardware constraints: The experiments were conducted on a single laptop. Although performance was strong, results may vary with different configurations. Clustered deployments of Neo4j should be studied for improved scalability, resilience, and fault tolerance;

Data sources: Health monitoring devices have been simulated in this work because the scope of the proposal was Fog nodes. The use of real IoMT devices as data sources may impose new requirements, which will be addressed in future work.

Integration with streaming systems: Under high-throughput conditions, real-world applications may require buffering to prevent data loss. Integrating Neo4j with streaming platforms, such as Apache Kafka [

37]—which Neo4j supports—could provide robust solutions for data ingestion and flow control;

ML and analytics integration: This study focused on data collection and query performance. The next step is to evaluate the integration of Neo4j with ML pipelines to support risk detection, anomaly monitoring, and predictive clinical decision-making.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.A.Y. and J.C.-A.; methodology, J.C.-A.; software, K.A.Y.; validation, K.A.Y. and J.C.-A.; formal analysis, K.A.Y.; investigation, K.A.Y. and J.C.-A.; writing—original draft preparation, J.C.-A.; writing—review and editing, J.C.-A. and A.W.L.-R.; supervision, J.C.-A. and A.W.L.-R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ACID | Atomicity, consistency, isolation, and durability |

| BPM | Blood Pressure Monitor |

| COPD | Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease |

| ECG | Electrocardiogram |

| EHR | Electronic Health Record |

| FC | Fog Computing |

| FHIR | Fast Healthcare Interoperability Resources |

| GDB | Graph-based Database |

| GM | Glucose Monitor |

| HRM | Heart Rate Monitor |

| IoT | Internet of Things |

| IoMT | Internet of Medical Things |

| ML | Machine Learning |

| OSM | Oxygen Saturation Monitor |

| TM | Temperature Monitor |

References

- Abdulmalek, S.; Nasir, A.; Jabbar, W.A.; Almuhaya, M.A.M.; Bairagi, A.K.; Khan, M.A.-M.; Kee, S.-H. IoT-Based Healthcare-Monitoring System towards Improving Quality of Life: A Review. Healthcare 2022, 10, 1993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akilan; Hariharan, U.; Prakash, I.B.; Rajkumar, K. Exploring the Impact and Potential of the Internet of Medical Things (IoMT): A Comprehensive Review. In Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Advances in Computing, Communication Control and Networking (ICAC3N), Greater Noida, India, 15–16 December 2023; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2023; pp. 967–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aman, A.H.M.; Hassan, W.H.; Sameen, S.; Attarbashi, Z.S.; Alizadeh, M.; Latiff, L.A. IoMT amid COVID-19 Pandemic: Application, Architecture, Technology, and Security. J. Netw. Comput. Appl. 2021, 174, 102886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, S.F.; Alam, M.S.B.; Afrin, S.; Rafa, S.J.; Rafa, N.; Gandomi, A.H. Insights into Internet of Medical Things (IoMT): Data Fusion, Security Issues and Potential Solutions. Inf. Fusion 2024, 102, 102060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Industry IoT Consortium. OpenFog Reference Architecture for Fog Computing. Available online: https://www.iiconsortium.org/pdf/OpenFog_Reference_Architecture_2_09_17.pdf (accessed on 8 September 2025).

- Islam, U.; Alatawi, M.N.; Alqazzaz, A.; Alamro, S.; Shah, B.; Moreira, F. A hybrid fog-edge computing architecture for real-time health monitoring in IoMT systems with optimized latency and threat resilience. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 25655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shah, B.; Junaid, M.; Rustam, H.; Habib, M.; Anwar, S. AI-Driven Fog-Edge Computing for IoMT Systems: Architecture and Use Cases. In Proceedings of the AAAI Symposium Series, Dubai, United Arab Emirates, 20–22 May 2025; Geib, C.W., Petrick, R., Ullah, A., Eds.; The AAAI Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2025; pp. 42–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallo, G.D.; Micucci, D. Internet of Medical Things Systems Review: Insights into Non-Functional Factors. Sensors 2025, 25, 2795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-deep, S.E.; Abohany, A.A.; Sallam, K.M.; El-Mageed, A.A.A. A Comprehensive Survey on Impact of Applying Various Technologies on the Internet of Medical Things. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2025, 58, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, S.; Shuaib, M.; Ahmad, S.; Jayakody, D.N.K.; Muthanna, A.; Bharany, S.; Elgendy, I.A. Blockchain-Based Solutions Supporting Reliable Healthcare for Fog Computing and Internet of Medical Things (IoMT) Integration. Sustainability 2022, 14, 15312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asghar, A.; Abbas, A.; Khattak, H.A.; Khan, S.U. Fog Based Architecture and Load Balancing Methodology for Health Monitoring Systems. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 96189–96200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fazeldehkordi, E.; Grønli, T.M. A Survey of Security Architectures for Edge Computing-Based IoT. IoT 2022, 3, 332–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Open Edge Computing Inititative. Available online: http://openedgecomputing.org (accessed on 8 September 2025).

- Mukherjee, A.; Ghosh, S.; Behere, A.; Ghosh, S.K.; Buyya, R. Internet of Health Things (IoHT) for Personalized Health Care Using Integrated Edge-Fog-Cloud Network. J. Ambient. Intell. Humaniz. Comput. 2021, 12, 943–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteiro, J.; Sá, F.; Bernardino, J. Experimental Evaluation of Graph Databases: JanusGraph, Nebula Graph, Neo4j, and TigerGraph. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 5770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, A.; Rodrigues, D.; Saraiva, J.; Abbasi, M.; Martins, P.; Wanzeller, C. Scalability and Performance Evaluation of Graph Database Systems: A Comparative Study of Neo4j, JanusGraph, Memgraph, NebulaGraph, and TigerGraph. In Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference On Smart Technologies For Smart Nation (SmartTechCon), Singapore, 18–19 August 2023; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2023; pp. 537–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondal, S.; Mukherjee, N. Efficient NoSQL Graph Database for Storage and Access of Health Data. In Computer Communication, Networking and IoT, Proceedings of ICICC 2020; Bhateja, V., Satapathy, S.C., Travieso-Gonzalez, C.M., Flores-Fuentes, W., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2021; pp. 135–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freedman, H.; Miller, M.A.; Williams, H.; Stoeckert, C.J. Scaling and Querying a Semantically Rich, Electronic Healthcare Graph. In Proceedings of the 11th International Conference on Biomedical Ontologies, Bolzano, Italy, 17 September 2020; CEUR Workshop, 2807. pp. 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, Y.; Li, G.Z.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, M.; Zhang, L. Study on Construction and Application of Knowledge Graph of TCM Diagnosis and Treatment of Viral Hepatitis B. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE International Conference on Bioinformatics and Biomedicine (BIBM), Virtual Event, 9–12 December 2021; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2021; pp. 3906–3911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trevena, W.; Lal, A.; Zec, S.; Cubro, E.; Zhong, X.; Dong, Y.; Gajic, O. Modeling of Critically Ill Patient Pathways to Support Intensive Care Delivery. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2022, 7, 7287–7294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivas, A.; Vidal, M.E. Capturing Knowledge about Drug-Drug Interactions to Enhance Treatment Effectiveness. Proceedings of 11th Knowledge Capture Conference (K-CAP’21), Virtual Event, 2–3 December 2021; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pujante-Otalora, L.; Campos, M.; Juarez, J.M.; Vidal, M.E. Comparison Between Graph Databases and RDF Engines for Modelling Epidemiological Investigation of Nosocomial Infections. In Proceedings of the 17th International Joint Conference on Biomedical Engineering Systems and Technologies (BIOSTEC), Rome, Italy, 21–23 February 2024; Scitepress: Setúbalm, Portugal, 2024; Volume 2, pp. 23–36. [Google Scholar]

- Neo4j. Available online: https://neo4j.com/ (accessed on 2 September 2025).

- Besta, M.; Gerstenberger, R.; Peter, E.; Fischer, M.; Podstawski, M.; Barthels, C.; Alonso, G.; Hoefler, T. Demystifying Graph Databases: Analysis and Taxonomy of Data Organization, System Designs, and Graph Queries. ACM Comput. Surv. 2023, 56, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, I.; Webber, J.; Eifrem, E. Graph Databases: New Opportunities for Connected Data; O’Reilly Media: Sebastopol, CA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Van Bruggen, R. Learning Neo4j; Packt Publishing: Birmingham, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, P.; Saini, H.; Kalia, A. SURETY-Fog: Secure Data Query and Storage Processing in Fog Driven IoT Environment. Sustain. Comput. Inform. Syst. 2025, 46, 101113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burhan, M.; Alam, H.; Arsalan, A.; Rehman, R.A.; Anwar, M.; Faheem, M.; Ashraf, M.W. A Comprehensive Survey on the Cooperation of Fog Computing Paradigm-Based IoT Applications: Layered Architecture, Real-Time Security Issues, and Solutions. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 73303–73329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO/IEC 27001:2022; Information security, cybersecurity and privacy protection — Information security management systems — Requirements. ISO/IEC: Geneve, Switzerland, 2022.

- Said, A.; Yahyaoui, A.; Abdellatif, T. HIPAA and GDPR Compliance in IoT Healthcare Systems. In Advances in Model and Data Engineering in the Digitalization Era, Proceedings of the International Conference on Model and Data Engineering (MEDI), Sousse, Tunisia, 2–4 November 2023; Mosbah, M., Kechadi, T., Bellatreche, L., Gargouri, F., Guegan, C.G., Badir, H., Beheshti, A., Gammoudi, M.M., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 198–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alegría, B.; Wong, L.; Bedriñiana, D. Model for Implementing an IoMT Architecture with ISO/IEC 27001 Security Controls for Remote Patient Monitoring. In Proceedings of the 32nd Conference of Open Innovations Association (FRUCT), Tampere, Finland, 9–11 November 2022; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2022; pp. 38–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atlam, H.F.; Yang, Y. Enhancing Healthcare Security: A Unified RBAC and ABAC Risk-Aware Access Control Approach. Future Internet 2025, 17, 262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FIPS-197; Advanced Encryption Standard. National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST): Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 2001.

- Das, S.; Namasudra, S. A Novel Hybrid Encryption Method to Secure Healthcare Data in IoT-enabled Healthcare Infrastructure. Comput. Electr. Eng. 2022, 101, 107991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- HL7. HL7 FHIR. Available online: https://www.hl7.org/fhir/ (accessed on 2 September 2025).

- Cho, P.; Kim, J.; Bent, B.; Dunn, J. BIG IDEAs Lab Glycemic Variability and Wearable Device Data, Version 1.1.2; PhysioNet: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2023; Available online: https://physionet.org/content/big-ideas-glycemic-wearable/1.1.2/ (accessed on 2 September 2025).

- Neo4j. Neo4j Connector for Kafka. Available online: https://neo4j.com/docs/kafka/current/ (accessed on 2 September 2025).

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).