An In-Depth Measurement of Security and Privacy Risks in the Free Live Sports Streaming Ecosystem

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Large-Scale Threat Characterization: We perform a broad analysis of security threats across hundreds of FLS sites, revealing a diverse and adaptive landscape of attacks ranging from phishing schemes to sophisticated malware delivery.

- In-Depth Behavioral Malware Analysis: We document the specific post-infection behavior of malware delivered via FLS platforms, detailing their persistence mechanisms and data exfiltration techniques.

- A Multi-Vantage Point Privacy Assessment: We conduct a multi-vantage point analysis of the FLS tracking ecosystem from four distinct geographic regions, demonstrating that invasive device fingerprinting is applied uniformly with a disregard for regional privacy laws like the GDPR.

- Co-ownership and Infrastructure Mapping: We use publisher-specific IDs to uncover eight clusters of co-owned FLS domains, revealing their consolidated and resilient illicit infrastructure.

2. Background and Related Work

3. Methodology

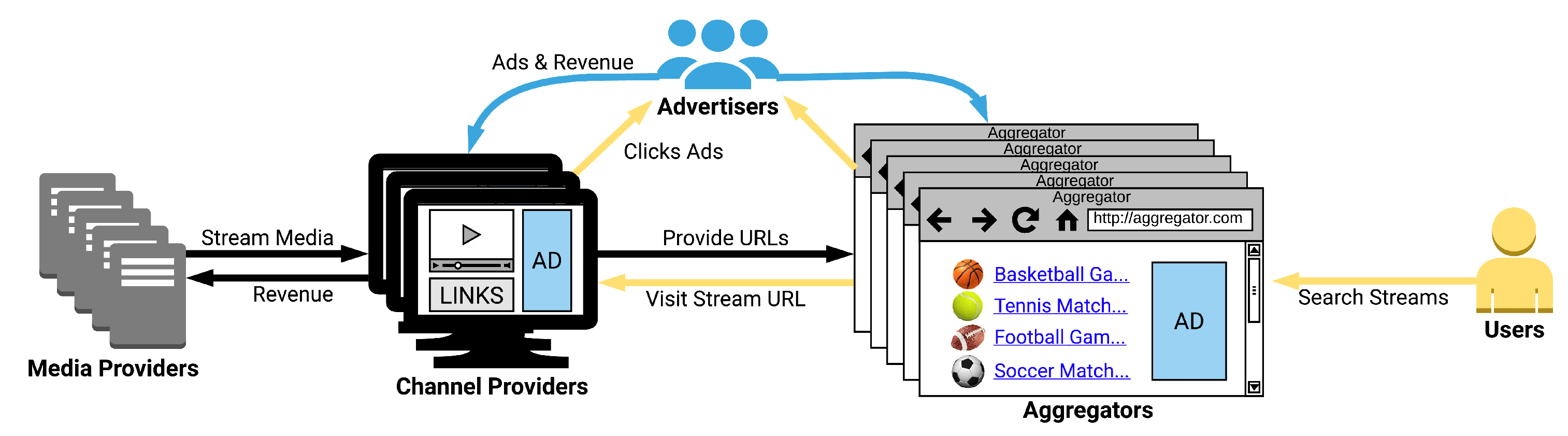

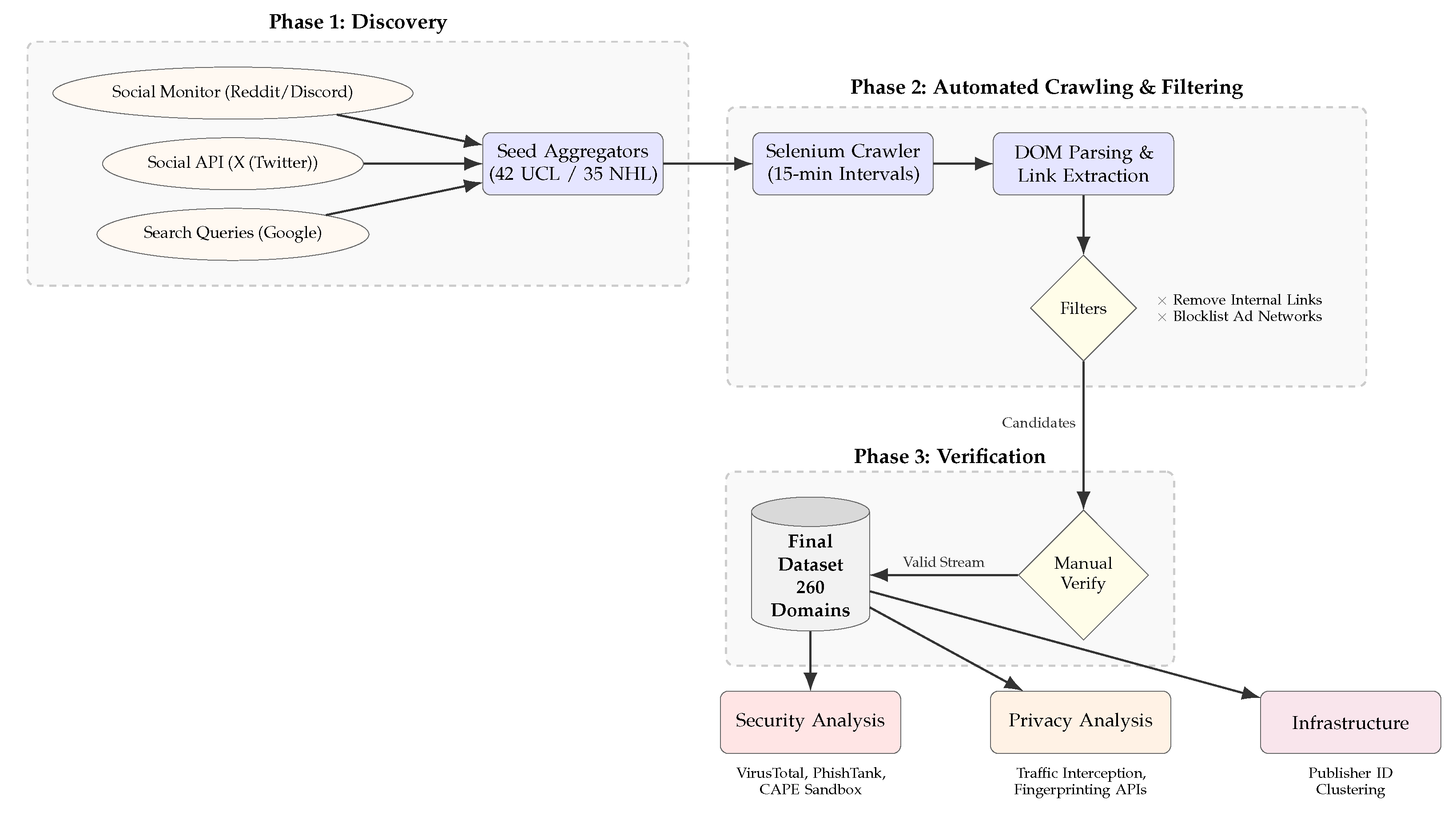

3.1. FLS Site Identification and Data Collection

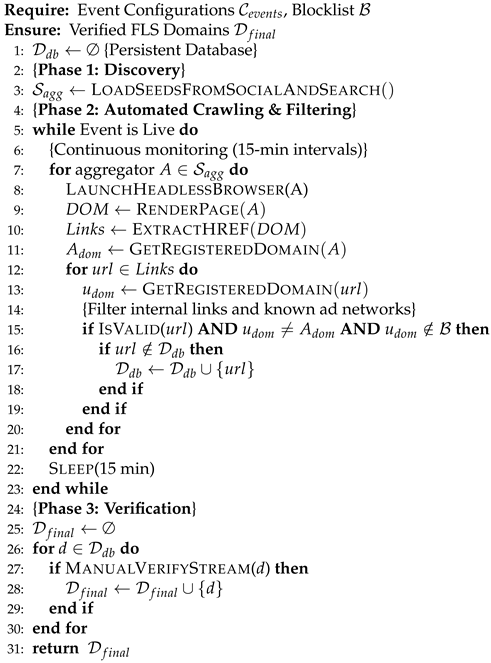

| Algorithm 1 Automated FLS Link Discovery and Filtering (Implementation: scripts/1_collect_links.py and scraper.py [22]) |

|

3.1.1. Phase 1: Discovery

3.1.2. Phase 2: Automated Crawling & Filtering

3.1.3. Phase 3: Verification

3.2. Measurement Environment and Ethics

3.3. Security Threat Analysis

3.4. Privacy Violation Analysis

4. Analysis and Findings

4.1. Security Analysis

4.1.1. Drive-By Downloads and Malware Behavior

Case Study: HD-StreamPlayer.exe

Other Malware Payloads

4.1.2. Malicious and Evasive JavaScript

4.1.3. Malvertising, Phishing, and Scams

4.2. Privacy Analysis

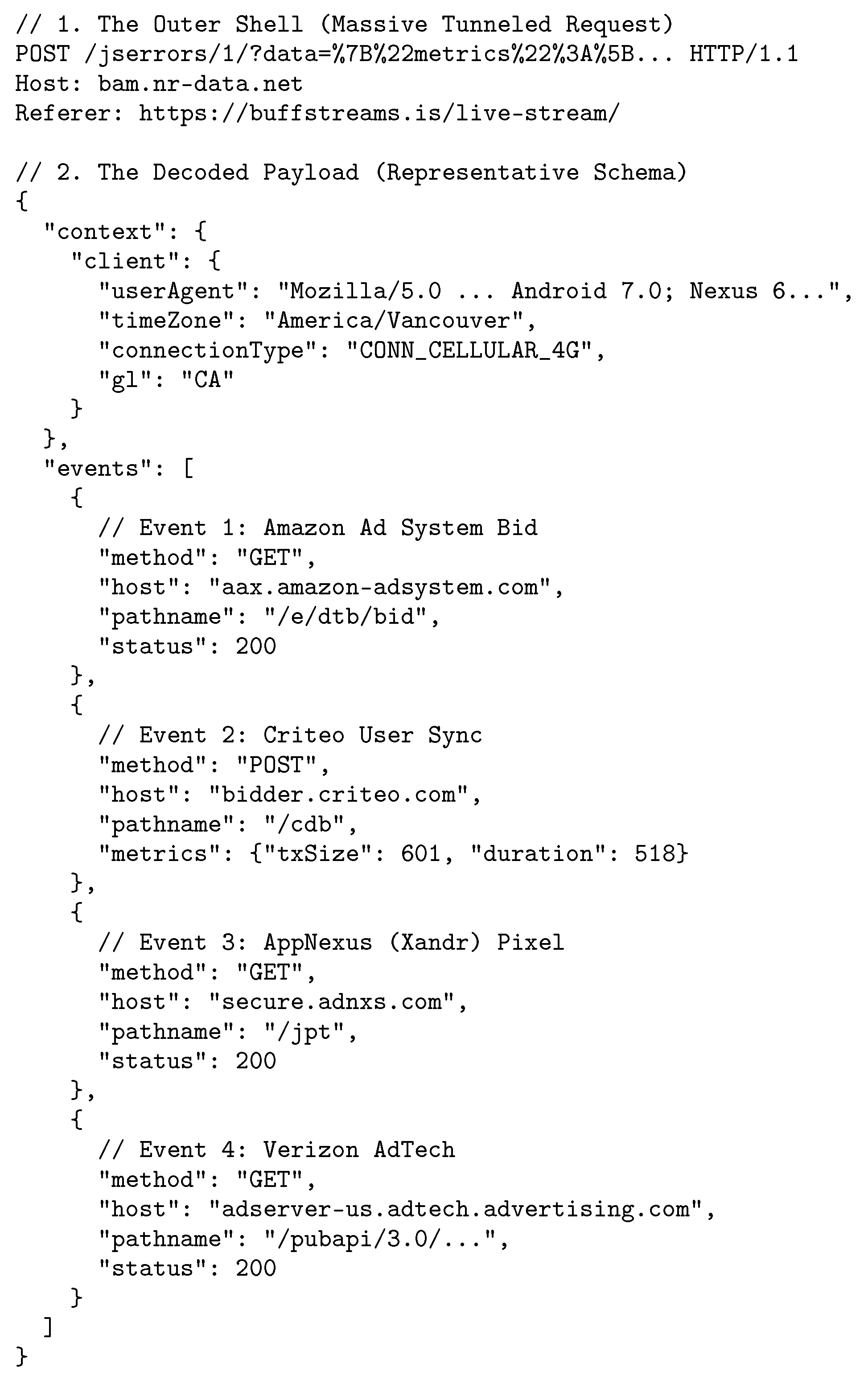

4.2.1. Unauthorized Data Collection and Tracking

4.2.2. Cookie Proliferation and Lack of Consent

4.2.3. Centralized Infrastructure and Brand Diversification

4.2.4. Web Security Posture and Safeguard Effectiveness

5. Discussion

Limitations and Future Work

6. Conclusions

- Our identification of co-owned clusters (e.g., 12 domains sharing a single AdSense ID) implies that enforcement should shift from blocking ephemeral domains to sanctioning the underlying financial identifiers. Blacklisting specific Publisher IDs across ad-tech exchanges would demonetize entire portfolios of sites simultaneously.

- The prevalence of malvertising and drive-by downloads indicates a failure in the ad supply chain. Policy interventions must enforce stricter “Know Your Customer” (KYC) protocols for ad exchanges, holding them accountable for vetting the creative content delivered through their networks.

- Since users might exhibit contextual risk displacement during live events, static blocklists (like PhishTank) are often too slow (as evidenced by the detection lag we measured). Browser vendors should implement heuristic warnings specifically for live streaming signatures, such as the simultaneous execution of high-entropy canvas fingerprinting and aggressive overlay ads, to warn users in real-time.

- To combat the drive-by downloads we observed, browser vendors should implement heuristics to detect and block invisible overlays (e.g., transparent <div> elements intercepting clicks) commonly used to hijack user interactions on video players.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lee, C.C.; Nagpal, P.; Ruane, S.G.; Lim, H.S. Factors affecting online streaming subscriptions. Commun. IIMA 2018, 16, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keshvadi, S.; Williamson, C. An empirical measurement study of free live streaming services. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Passive and Active Network Measurement, Virtual, 29 March–1 April 2021; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 111–127. [Google Scholar]

- MUSO. 2024 Piracy Trends and Insights; Technical report; MUSO: Mumbai, India, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Blackburn, D.; Eisenach, J.A.; Harrison, D. Impacts of Digital Video Piracy on the US Economy; Nera Economic Consulting, Global Innovation Policy Center: Washington, DC, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Armenia, S.; Ferreira Franco, E.; Nonino, F.; Spagnoli, E.; Medaglia, C.M. Towards the definition of a dynamic and systemic assessment for cybersecurity risks. Syst. Res. Behav. Sci. 2019, 36, 404–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acar, G.; Eubank, C.; Englehardt, S.; Juarez, M.; Narayanan, A.; Diaz, C. The web never forgets: Persistent tracking mechanisms in the wild. In Proceedings of the 2014 ACM SIGSAC Conference on Computer and Communications Security, Scottsdale, AZ, USA, 3–7 November 2014; pp. 674–689. [Google Scholar]

- Sheaib, H.; Feldmann, A.; Dao, H. Unmasking the Shadows: A Cross-Country Study of Online Tracking in Illegal Movie Streaming Services. In Proceedings of the Proceedings on Privacy Enhancing Technologies Symposium, Washington, DC, USA, 14–19 July 2025; pp. 125–139. [Google Scholar]

- Belanger, F.; Hiller, J.S.; Smith, W.J. Trustworthiness in electronic commerce: The role of privacy, security, and site attributes. J. Strateg. Inf. Syst. 2002, 11, 245–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, W.; Hur, J.; Kim, D. Beneath the phishing scripts: A script-level analysis of phishing kits and their impact on real-world phishing websites. In Proceedings of the 19th ACM Asia Conference on Computer and Communications Security, Singapore, 1–5 July 2024; pp. 856–872. [Google Scholar]

- Telang, R. Does Online Piracy Make Computers Insecure? Evidence from Panel Data; SSRN: Rochester, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Ibosiola, D.; Steer, B.; Garcia-Recuero, A.; Stringhini, G.; Uhlig, S.; Tyson, G. Movie pirates of the caribbean: Exploring illegal streaming cyberlockers. In Proceedings of the International AAAI Conference on Web and Social Media, Palo Alto, CA, USA, 25–28 June 2018; Volume 12. [Google Scholar]

- Hsiao, L.; Ayers, H. The price of free illegal live streaming services. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1901.00579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Digital Citizens Alliance; White Bullet. Breaking (B)ads: How Advertiser-Supported Piracy Helps Fuel A Booming Multi-Billion Dollar Illegal Market; Technical report; Digital Citizens Alliance: Washington, DC, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Rafique, M.Z.; Van Goethem, T.; Joosen, W.; Huygens, C.; Nikiforakis, N. It’s Free for a Reason: Exploring the Ecosystem of Free Live Streaming Services. In Proceedings of the NDSS, San Diego, CA, USA, 21–24 February 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper, S. Online Ads Supporting Copyright Piracy Need to Be Stopped. Free State Foundation: United States of America, 2021. Available online: https://coilink.org/20.500.12592/j4m8xf (accessed on 17 October 2025).

- Iqbal, U.; Shafiq, Z.; Qian, Z. The ad wars: Retrospective measurement and analysis of anti-adblock filter lists. In Proceedings of the 2017 Internet Measurement Conference, London, UK, 1–3 November 2017; pp. 171–183. [Google Scholar]

- Siby, S.; Iqbal, U.; Englehardt, S.; Shafiq, Z.; Troncoso, C. {WebGraph}: Capturing advertising and tracking information flows for robust blocking. In Proceedings of the 31st USENIX Security Symposium (USENIX Security 22), Boston, MA, USA, 10–12 August 2022; pp. 2875–2892. [Google Scholar]

- Veale, M.; Borgesius, F.Z. Adtech and real-time bidding under European data protection law. Ger. Law J. 2022, 23, 226–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouhoula, A.; Kubicek, K.; Zac, A.; Cotrini, C.; Basin, D. Automated {Large-Scale} analysis of cookie notice compliance. In Proceedings of the 33rd USENIX Security Symposium (USENIX Security 24), Philadelphia, PA, USA, 14–16 August 2024; pp. 1723–1739. [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez-Rola, I.; Bilge, L.; Balzarotti, D.; Buescher, A.; Efstathopoulos, P. Rods with laser beams: Understanding browser fingerprinting on phishing pages. In Proceedings of the 32nd USENIX Security Symposium (USENIX Security 23), Anaheim, CA, USA, 9–11 August 2023; pp. 4157–4173. [Google Scholar]

- Saha Roy, S.; Karanjit, U.; Nilizadeh, S. Phishing in the free waters: A study of phishing attacks created using free website building services. In Proceedings of the 2023 ACM on Internet Measurement Conference, Montreal, QC, Canada, 24–26 October 2023; pp. 268–281. [Google Scholar]

- Muruganandham, N.; Keshvadi, S. Code and Data for: An In-Depth Measurement of Security and Privacy Risks in the Free Live Streaming Ecosystem. 2025. Available online: https://github.com/Keshvadi/fls-paper (accessed on 17 October 2025).

- XK72 Ltd. Charles Web Debugging Proxy. Available online: https://www.charlesproxy.com (accessed on 9 July 2025).

- Regulation, P. General data protection regulation. Intouch 2018, 25, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Google. VirusTotal. Available online: https://www.virustotal.com (accessed on 9 July 2025).

- Cisco. PhishTank: Join the Fight Against Phishing. Available online: https://phishtank.org (accessed on 9 July 2025).

- The CAPE Sandbox Developers. CAPE Sandbox. Available online: https://capesandbox.com (accessed on 9 July 2025).

- Eyeo GmbH. EasyList and EasyPrivacy Filter Lists. Available online: https://easylist.to (accessed on 9 July 2025).

- Disconnect, Inc. Disconnect Malvertising and Tracking Protection Lists. Available online: https://disconnect.me (accessed on 9 July 2025).

- mrd0x. MalAPI.io: Windows API Mapping for Malware Research, 2024. Available online: https://malapi.io (accessed on 9 July 2025).

- Pennington, A.; Applebaum, A.; Nickels, K.; Schulz, T.; Strom, B.; Wunder, J. Getting Started with ATT&CK; MITRE Corporation: McLean, VA, USA, 2019; Available online: https://attack.mitre.org/resources (accessed on 17 October 2025).

| Threat Category | Prevalence | 95% C.I. | Observed Behavior/Vector |

|---|---|---|---|

| Security Threats | |||

| Malicious JavaScript | 31.5% | ±5.6% | Obfuscated scripts injecting overlay ads and redirecting to external malware sources. |

| Phishing Redirects | 51 Chains | – | Redirection chains leading to confirmed phishing pages (via PhishTank). |

| Ad-Blocker Evasion | 12.0% | ±4.0% | Scripts containing logic to detect ad-blockers and block video playback. |

| Drive-by Downloads | Observed | – | Automatic download of payloads (e.g., HD-StreamPlayer.exe) triggered by ad interactions. |

| Privacy Violations (Static Detection) | |||

| Canvas Fingerprinting | 12.0% | ±4.0% | Scripts invoking high-entropy extraction APIs (canvas.toDataURL or getImageData). |

| Font Fingerprinting | 8.0% | ±3.3% | Scripts containing keywords for font enumeration (e.g., measureText). |

| WebRTC Leakage | 5.0% | ±2.7% | Presence of RTCPeerConnection logic capable of leaking local IP addresses. |

| Tactic | Technique ID | Technique Name | Observed Evidence in FLS Ecosystem |

|---|---|---|---|

| Initial Access | T1189 | Drive-by Compromise | Malicious JavaScript in ad iframes triggering window.location.replace to force downloads without user interaction. |

| T1566.002 | Phishing: Spearphishing Link | Deceptive “Play” buttons and overlay ads tricking users into manually downloading malware. | |

| Execution | T1204.002 | User Execution: Malicious File | Users manually launching HD-StreamPlayer.exe believing it is a required codec update. |

| T1059.007 | Command and Scripting Interpreter | Obfuscated JavaScript (e.g., tag.min.js) executing in the browser to inject ads/redirects. | |

| Persistence | T1547.001 | Registry Run Keys | Malware adds entries to HKCU\...\Run to ensure execution on startup. |

| Privilege Escalation | T1055.001 | Process Injection: DLL Injection | Dropped .tmp payloads utilizing LdrLoadDll to inject malicious code into advapi32.dll. |

| Defense Evasion | T1027 | Obfuscated Files or Information | Heavily obfuscated JavaScript and packed binaries used to evade signature-based AV detection. |

| T1562.001 | Impair Defenses: Disable Tools | Scripts detecting ad-blockers and blocking content playback until protection is disabled. | |

| Discovery | T1082 | System Information Discovery | Malware profiling the victim’s OS version, Hostname, and User Name immediately upon execution. |

| T1016 | System Network Config Discovery | Scripts (WebRTC) and binaries enumerating local IP addresses and Network Context. | |

| Exfiltration | T1041 | Exfiltration Over C2 Channel | Continuous transmission of fingerprinted data to tracking APIs via HTTP GET parameters. |

| Metric | FLS Ecosystem (n = 260) | TSN (Official) | Sportsnet (Official) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mozilla Observatory Score | F (Most Sites) | F | B |

| HTTPS Implementation | 98% | Yes | Yes |

| Content Security Policy | 8% (Rare) | Missing | Present |

| Cookie Volume (Max) | ≈70 | 68 | 62 |

| Malicious Trackers | Detected | None | None |

| Malware Vectors | Present | Absent | Absent |

| Ad-Block Detection | 12% (Active Block) | None | None |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Muruganandham, N.; Sharma, Y.; Keshvadi, S. An In-Depth Measurement of Security and Privacy Risks in the Free Live Sports Streaming Ecosystem. J. Cybersecur. Priv. 2026, 6, 8. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcp6010008

Muruganandham N, Sharma Y, Keshvadi S. An In-Depth Measurement of Security and Privacy Risks in the Free Live Sports Streaming Ecosystem. Journal of Cybersecurity and Privacy. 2026; 6(1):8. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcp6010008

Chicago/Turabian StyleMuruganandham, Nithiya, Yogesh Sharma, and Sina Keshvadi. 2026. "An In-Depth Measurement of Security and Privacy Risks in the Free Live Sports Streaming Ecosystem" Journal of Cybersecurity and Privacy 6, no. 1: 8. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcp6010008

APA StyleMuruganandham, N., Sharma, Y., & Keshvadi, S. (2026). An In-Depth Measurement of Security and Privacy Risks in the Free Live Sports Streaming Ecosystem. Journal of Cybersecurity and Privacy, 6(1), 8. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcp6010008