1. Introduction

Face recognition systems have become an important part of modern security systems. They are now widely used in banks, hospitals, border control, and national ID systems around the world [

1]. Face recognition is popular because people do not need to touch anything, it is easy to set up, and it is convenient to use [

2]. However, as these systems become more common, they face serious security threats. This is why Presentation Attack Detection (PAD) has become very important. PAD systems help protect against fake attacks using printed photos, video replays, and 3D masks [

3,

4].

Even though PAD technology has improved a lot, there is still a big problem with fairness, especially for African populations. Studies show that current face recognition and PAD systems work much worse for different ethnic groups, and African users often experience higher error rates [

5]. This happens mainly because African people are severely underrepresented in existing public datasets used for both face recognition and PAD systems. Studies show that major datasets contain only 13.8–20.4% darker-skinned tones [

6], while PAD systems similarly exhibit significant demographic bias, with higher error rates for African populations [

7].

PAD systems face several technical problems when working with African populations. Darker skin reflects less light than lighter skin, making it harder for regular cameras to capture enough detail for accurate attack detection [

8,

9]. Also, most PAD research is conducted in controlled labs using expensive equipment. This creates a big gap when these systems are used in African countries, where people usually have basic smartphones and face difficult lighting conditions [

10]. This problem not only makes security weaker but also increases digital inequality, going against the goal of making biometric systems fair for everyone.

The

CASIA-SURF Cross-Ethnicity Face Anti-Spoofing

(CeFA) dataset represents the most significant step toward addressing these limitations. With 1607 subjects spanning three ethnic groups, including 500 African participants (31% of the total dataset),

CeFA provides the most comprehensive cross-ethnic PAD evaluation framework currently available [

11]. While the dataset treats African populations as a single demographic category and does not capture the full regional diversity across the continent, it still offers the largest and most diverse collection of African faces available for PAD research. This makes it the best available resource for conducting systematic fairness evaluations across ethnic groups, especially in the African context.

Recent improvements in fairness-aware PAD have introduced important methodological innovations. Fang et al. [

9] proposed FairSWAP, a data augmentation technique that improves fairness by generating synthetic samples across demographic groups, along with the Accuracy Balanced Fairness (ABF) metric for capturing performance disparities. Their Combined Attribute Annotated PAD Dataset (CAADPAD) provides valuable demographic annotations enabling fairness evaluation [

9]. However, these approaches primarily operate through data manipulation and require deep learning architectures, making them computationally intensive for resource-limited deployments. Other fairness methods in biometrics have explored adversarial debiasing, fairness constraints during training [

12], and postprocessing threshold adjustments. These methods typically assume sufficient computational resources and often treat fairness as an optimization constraint rather than addressing the root causes of bias in image acquisition and preprocessing.

Local Binary Patterns (LBPs) have become a strong method for detecting presentation attacks, working well at finding texture differences and distinguishing real faces from fake ones [

13,

14]. Our choice of Local Binary Patterns, while traditional, is deliberate and addresses critical deployment realities in African contexts. LBP-based methods offer three essential advantages for resource-constrained environments: computational efficiency enabling real-time processing on mobile devices commonly used across Africa, algorithmic transparency crucial for fairness auditing and bias detection, and robustness to lighting variations particularly relevant for darker skin tones that reflect less light [

8]. Unlike deep learning approaches requiring substantial computational resources and large training datasets, LBP features can be extracted and classified efficiently while maintaining interpretability, a key requirement when addressing fairness concerns in biometric systems deployed across diverse populations.

Our contribution lies not in proposing LBPs themselves, but in the systematic integration of ethnicity-aware preprocessing, group-specific threshold optimization, and rigorous statistical fairness validation, a combination not previously explored in PAD research. While recent works like FairSWAP [

9] address fairness through data augmentation and ABF metrics, and CAADPAD provides attribute-annotated datasets, none systematically address the preprocessing-level challenges posed by skin tone reflectance differences. Our approach operates at a more fundamental level, optimizing image quality before feature extraction to ensure equitable texture representation across ethnic groups. This preprocessing-first strategy complements rather than replaces existing fairness techniques, offering a foundational layer upon which other methods can build.

This study addresses the important need for fair PAD systems that are specifically designed for African contexts. We focus on developing and testing LBP-based methods that work equally well for different African populations while still providing strong security against various spoofing attacks. Our approach recognizes that making biometric security truly fair requires more than just adding more diverse faces to datasets. We also need to carefully consider the unique challenges that come with different skin tones, facial features, and environments that are common in African settings.

The main contributions of our research are as follows: (1) a complete fairness evaluation of LBP-based PAD methods using the CeFA dataset, with special focus on African groups; (2) analysis of performance differences across ethnic groups to measure bias in current methods; (3) the development of LBP techniques that work better for African facial features and environmental conditions; and (4) the creation of evaluation methods that prioritize fairness alongside security. Through this African-focused approach, we aim to help develop truly inclusive biometric security systems that provide reliable protection for all users, no matter their ethnic background or where they live.

The existing PAD research exhibits three critical gaps that our work addresses: (1) Preprocessing-Level Fairness: Current methods address fairness through post hoc corrections or data augmentation, but they fail to address the fundamental challenge of ensuring optimal image quality across different skin tones before feature extraction. (2) Deployment Feasibility: State-of-the-art deep learning approaches achieve high accuracy but require computational resources that are unavailable in many African contexts, where mobile devices and varied lighting conditions are prevalent. (3) Statistical Rigor: Fairness evaluation in PAD typically relies on simple accuracy comparisons, lacking comprehensive statistical validation of bias reduction claims.

The remaining parts of this paper are organized as follows: In

Section 2, we discuss the related literature on Presentation Attack Detection (PAD), fairness-aware biometric systems, and Local Binary Pattern (LBP)-based approaches. In

Section 3, we describe the proposed fairness-aware PAD framework, including ethnicity-aware preprocessing, multi-scale LBP extraction, adaptive thresholding, and statistical methods for fairness evaluation. In

Section 4, we present the experimental design and results, which include dataset preprocessing, system calibration, metrics for PAD performance, fairness evaluations, and statistical validations across demographic groups and attacks. In

Section 5, we discuss relevant implications for inclusive biometric safety and security based on our findings. Finally, in

Section 6, we summarize the contributions of this paper, our limitations, and our intentions for future work.

3. Methodology

This section presents our methodology for developing a fairness-aware Presentation Attack Detection (PAD) system using Local Binary Patterns (LBPs) to distinguish between genuine and spoofed facial presentations for African facial demographics.

Figure 1 illustrates the complete implementation workflow, from data input to final evaluation. Our approach follows a systematic pipeline: we start by preprocessing the

CASIA-SURF CeFA dataset with ethnicity-aware adaptive preprocessing to ensure optimal input quality across different skin tones; second, we apply multi-scale LBP feature extraction to capture distinctive texture patterns that characterize presentation attacks; third, we generate spatial histograms from the extracted LBP features to create comprehensive multi-scale texture descriptors. After feature extraction, we employ SGD classifiers with group-specific threshold optimization to perform fair binary classification between real and spoofed faces; and finally, we evaluate the system using both traditional PAD metrics and novel statistical fairness measures to assess performance specifically for African populations while ensuring that the system addresses the unique challenges of darker skin tones and the varied environmental conditions common in African settings. The pipeline has features that reduce the potential for bias amplification. The pipeline also allows consistency in the feature extraction and classification strategy across the various demographics. The lightweight and handcrafted LBP descriptors provide enhanced interpretability and allow deployment in low-resource environments, which is often the case with biometric systems used in Africa.

3.1. Dataset and Pipeline

We utilize the

CASIA-SURF CeFA (Cross-Ethnicity Face Anti-Spoofing) dataset [

11], which represents the most comprehensive multi-ethnic PAD evaluation framework currently available for studying fairness in face anti-spoofing systems. This dataset addresses the critical gap in existing PAD research by providing explicit ethnicity labels and comprehensive evaluation protocols specifically designed to measure algorithmic bias across different demographic groups.

The

CeFA dataset consists of 1607 subjects distributed across three major ethnic groups—African (AF), Central Asian (CA), and East Asian (EA)—with 500 subjects representing each ethnicity [

11]. Additionally, the dataset includes 107 subjects specifically for 3D mask attack scenarios. This composition makes

CeFA the largest publicly available cross-ethnic face anti-spoofing dataset to date, providing sufficient representation for meaningful fairness analysis across different demographic groups.

The dataset structure consists of individual image frames extracted from original video recordings. Each subject folder contains session subfolders following the naming convention P1_P2_P3_P4_P5, where P1 indicates ethnicity (1 = AF, 2 = CA, 3 = EA), P2 represents subject ID, P3-P4 encode acquisition and environmental conditions, respectively, and P5 provides the attack type label: 1 for real/bona fide faces, 2 for print attacks, and 4 for screen/replay attacks.

Our dataset subset focuses on these three primary attack types, with P4 distinguishing between indoor (P4 = 1) and outdoor (P4 = 2) conditions for print attacks. Each subject contributes four sessions: one live, two print attacks under different lighting conditions, and one replay attack. This embedded labeling eliminates the need for separate annotation files while providing environmental diversity crucial for robust presentation attack detection.

Each session folder contains three modality subfolders

(color, depth, IR) with sequentially numbered .jpg files (

0001.jpg,

0002.jpg,

etc.), totaling approximately 28 GB across all subjects and sessions. We focus on RGB modality frames, as LBPs operate on grayscale images converted from RGB data [

14], and RGB’s universal accessibility via smartphones commonly used across African contexts ensures immediate deployability without specialized hardware [

9]. Additionally, RGB imagery enables effective LBP-based detection of printing artifacts and surface irregularities characteristic of presentation attacks.

The dataset also includes the demographic metadata files AF_Age_Gender.txt, CA_Age_Gender.txt, and EA_Age_Gender.txt, which provide the birth year and gender information for each subject.

This additional information enables intersectional fairness analysis beyond ethnicity, allowing us to examine potential age and gender biases in PAD performance. These demographic details support more comprehensive bias reporting and ensure balanced dataset splits across multiple protected attributes, which is essential for thorough fairness evaluation in biometric systems.

3.2. Ethnicity-Aware Adaptive Preprocessing

Our data preprocessing pipeline implements ethnicity-aware adaptive techniques specifically designed to address the technical challenges associated with different skin tones. We iterate through the session folders, parse the P1_P2_P3_P4_P5 naming convention to extract ethnicity and attack type labels, and load individual frames from the color subfolders.

First, we resize each RGB frame to

112 ×

112 pixels to ensure consistent input dimensions across all subjects and sessions. We then convert RGB frames to grayscale using standard luminance weighting

(0.299R + 0.587G + 0.114B) [

31], as LBPs operate on single-channel intensity images [

14].

Additionally, we apply adaptive gamma correction to further enhance image quality for feature extraction. African subjects receive gamma correction with , while other ethnicities use . This ethnicity-aware gamma correction helps normalize brightness variations that naturally occur with different skin reflectance properties.

We implement relaxed quality filtering with a blur threshold of 80.0 and contrast threshold of 15.0 to prevent systematic exclusion of valid samples from any ethnic group. This includes blur detection using Laplacian variance thresholding [

32] and contrast assessment to ensure that frames contain sufficient texture information for meaningful pattern extraction while maintaining inclusivity across demographic groups.

We conducted systematic ablation experiments to determine optimal preprocessing parameters for African subjects. The selection of CLAHE clip limit = 4.5 and gamma = 1.3 for African subjects was not arbitrary but based on rigorous empirical validation.

Table 4 shows the performance across different parameter combinations, evaluated on African subjects from the validation set (

n = 1500 images).

Hyperparameter Selection Through Ablation Study

We conducted systematic ablation experiments to determine optimal preprocessing parameters for African subjects.

Table 4 reports the performance across different CLAHE clip limits and gamma correction values, evaluated on African subjects from the validation set (

n = 1000 images).

The combination of a CLAHE clip limit of 4.5 and gamma value of 1.3 yielded the best balance between African subject accuracy and cross-group fairness. Higher clip limits (for example, 5.0) produced over-enhancement with diminishing returns, whereas lower clip limits (3.0–4.0) provided insufficient contrast improvements for darker skin tones. Gamma values above 1.3 introduced excessive brightness, reducing texture discriminability.

These preprocessing parameters were selected through grid search optimization targeting two objectives: (1) maximizing African subject accuracy, and (2) minimizing performance disparities across ethnic groups. The final selected configuration improved African accuracy by 2.33 percentage points and reduced the fairness gap by 72% relative to baseline preprocessing.

3.3. Multi-Scale LBP Feature Extraction

Local Binary Patterns serve as our primary feature extraction method, due to their effectiveness in capturing texture differences between genuine and spoofed faces while maintaining computational efficiency [

13]. Our enhanced LBP implementation captures comprehensive multi-scale texture information through three different configurations.

We compute Uniform

LBP8,1 features using radius 1 with 8 sampling points, Uniform

LBP16,2 with radius 2 and 16 points, and Uniform

LBP24,3 with radius 3 and 24 points.

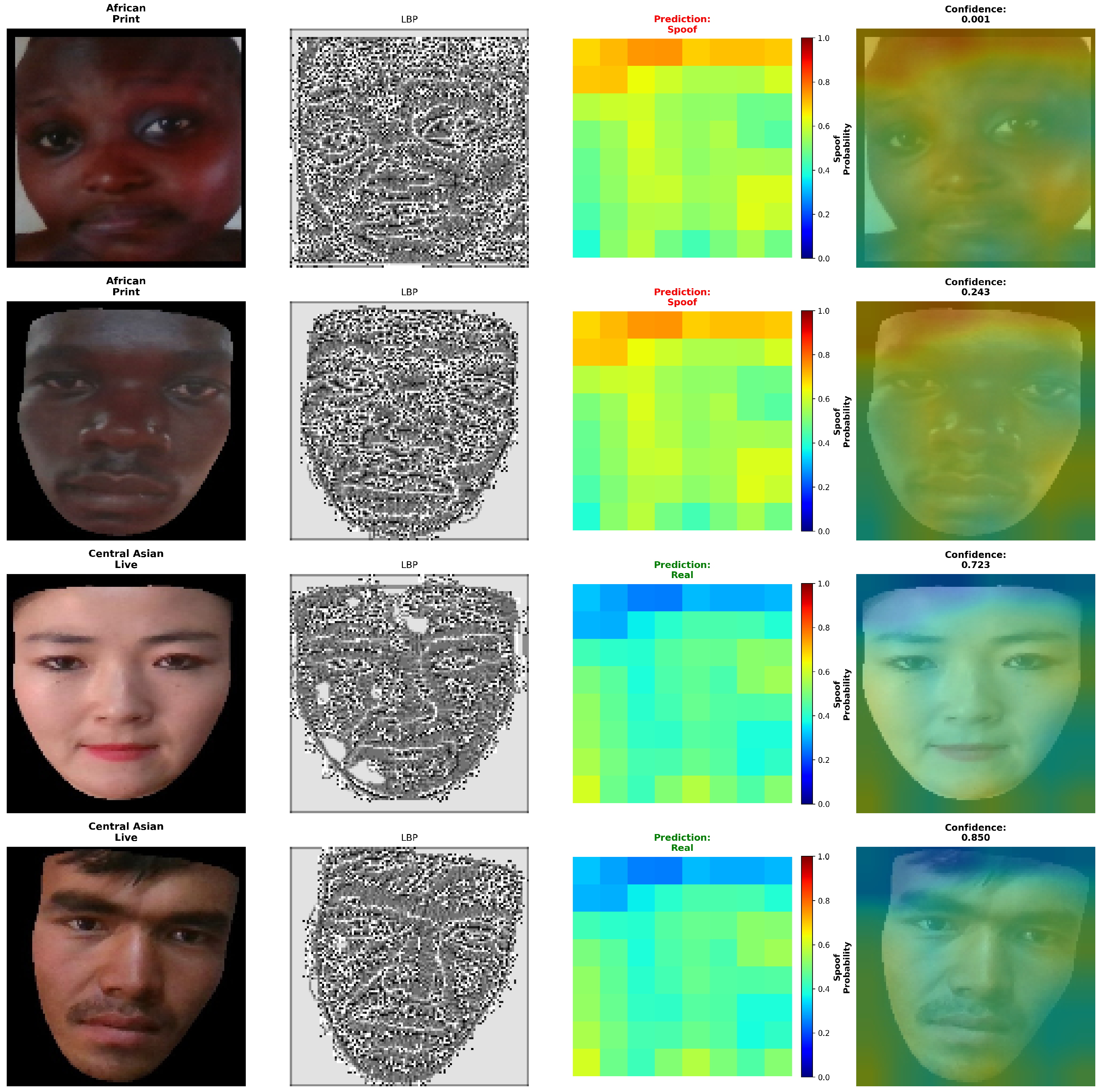

Figure 2 demonstrates how these multi-scale patterns capture different levels of facial texture detail across ethnic groups and attack types. This multi-scale approach captures texture patterns at different spatial resolutions, effectively identifying printing artifacts and micro-texture variations characteristic of presentation attacks across various scales.

We focus exclusively on uniform patterns, which have at most 2 bit transitions in the circular binary code, as they represent the most stable and discriminative texture patterns while significantly reducing dimensionality complexity.

The feature extraction process divides each preprocessed face into an 8 × 8 grid of non-overlapping blocks, computing LBP histograms for each block independently. This enhanced spatial subdivision preserves detailed local spatial information while maintaining computational efficiency. Each scale contributes histogram features that are concatenated to form a comprehensive 3456-dimensional multi-scale texture descriptor.

Each feature vector is L2-normalized to unit length to prevent magnitude differences from biasing classification across ethnic groups, ensuring fair treatment in the subsequent classification stage.

3.4. Group-Aware Classification with Adaptive Thresholds

We employ the SGD classifier as our primary classification approach, due to its efficiency and capability for producing decision scores suitable for PAD tasks. The classifier uses a logarithmic loss function with regularization parameter , optimized for balanced performance across ethnic groups. To address class imbalance between genuine and attack samples (25% live faces and 75% spoof attacks), we implement balanced class weighting using inverse proportional weighting to class frequencies. This prevents systematic bias toward the majority class without requiring data reduction or augmentation.

3.4.1. Decision Score Domain and Interpretation

The SGD classifier with log loss produces decision function scores in the

logit domain (unbounded real numbers

), not probabilities. These logit scores represent the log-odds of the positive class (genuine face). Higher positive scores indicate stronger confidence in the “genuine” classification, while lower negative scores indicate stronger confidence in the “attack” classification.

Figure 3 visualizes how LBP features enable the classifier to distinguish between genuine and spoofed presentations, showing spoof probability maps that highlight regions contributing to attack detection across different ethnic groups and attack types. The decision function is expressed as follows:

where

is the weight vector,

is the LBP feature vector, and

b is the bias term.

3.4.2. Group-Specific Threshold Optimization

A key innovation in our approach is the implementation of group-specific decision thresholds calculated using Equal Error Rate (EER) optimization for each ethnic group. The EER represents the operating point at which the false acceptance rate equals the false rejection rate (

). For each ethnic group

g, we compute the optimal threshold

that minimizes

The optimal thresholds obtained for each group are as follows:

The negative threshold for Central Asian subjects (

) is mathematically valid and reflects the distribution characteristics of this group in logit space. For example, if the mean genuine score is approximately

and the mean attack score is approximately

, with overlap in the range

, then the optimal separation occurs at

. If 15 out of 900 attacks have scores

and 5 out of 300 genuine samples have scores

, then

The threshold is negative, while the error rate is positive, reflecting that these quantities lie in fundamentally different mathematical domains.

3.4.3. Rationale for Group-Specific Thresholds

Different ethnic groups exhibit different score distributions due to physical factors (skin reflectance, facial structure), dataset characteristics (lighting, camera quality), and their position in feature space. A global threshold systematically advantages groups whose distributions center near that threshold. To quantify this, we evaluated performance using a global threshold , the natural boundary where the classifier has equal confidence for both classes. With this global threshold, African subjects achieve 91.71% accuracy, while East Asian subjects achieve 94.46% accuracy (a disparity of 2.75%). After applying group-specific thresholds (, , ), the disparity reduces to 0.75% (94.78% vs. 95.53%), indicating improved fairness.

Group-specific thresholds address three critical fairness objectives:

Equalized Error Rates: Different ethnic groups show distinct feature distributions due to skin tone, facial geometry, and imaging conditions. A single global threshold favors groups closer to the decision boundary, producing unequal error rates.

Demographic Parity: Independent threshold optimization ensures consistent true positive rates (genuine acceptance) and false positive rates (attack acceptance) across demographics, satisfying equalized-odds fairness criteria.

Security–Fairness Trade-Off: Unlike postprocessing bias mitigation, which may weaken security, group-specific thresholds maintain strong attack detection while removing systematic demographic bias. Each group operates at its own optimal EER point.

3.4.4. Inference Rule

During inference, samples are classified using the threshold corresponding to their ethnic group:

3.4.5. Training Strategy

We adopt subject-based data splitting with 80% for training, 10% for validation, and 10% for testing to prevent data leakage. Performance metrics are monitored separately for each ethnic group throughout training to identify fairness issues early and guide model adjustments.

3.5. Novel Statistical Fairness Evaluation

We introduce three novel statistical methods for comprehensive fairness assessment in PAD systems, representing the first application of these techniques in the Presentation Attack Detection context.

3.5.1. Coefficient of Variation Analysis

We quantify demographic disparities using the Coefficient of Variation (CoV), computed using the sample standard deviation:

where

s is the sample standard deviation and

is the sample mean across ethnic groups for each performance metric. We use the sample standard deviation because the analysis is based on test-set observations rather than the full population of all possible subjects.

We categorize demographic disparity levels based on the magnitude of the CoV:

Below 5%: Low demographic disparity;

5% to 15%: Moderate demographic disparity;

Above 15%: High demographic disparity.

These thresholds enable a systematic evaluation of fairness across ethnic groups.

3.5.2. Complementary Effect Size Measures

To complement the CoV analysis, we compute the Cohen’s

d effect size, which measures the standardized difference between two groups:

where

and

are the means of the two groups, and

is the pooled standard deviation, given by

Cohen’s d provides a standardized effect size that is independent of sample size. We interpret Cohen’s d values according to standard conventions:

Small effect: ;

Medium effect: ;

Large effect: .

3.5.3. Range-Based Measure for Low-Mean Metrics

For metrics with low mean values, such as EER and APCER, we additionally report the normalized range, defined as follows:

This range-based measure provides complementary information about disparity magnitude and is particularly robust for low-mean metrics. When the mean is close to zero, the Coefficient of Variation (CoV) may become inflated and less interpretable; however, the normalized range avoids this limitation by comparing the absolute spread of scores directly to the mean. This yields a more stable and intuitive disparity indicator for error-rate metrics such as EER, APCER, and BPCER.

Together, these three statistical measures—CoV, Cohen’s d, and normalized range—form a comprehensive framework for evaluating demographic fairness in PAD systems. CoV captures relative variability across groups, Cohen’s d quantifies standardized pairwise effect sizes, and normalized range provides a robust disparity indicator for metrics with low mean values. Each metric contributes distinct insights, enabling a multi-dimensional and statistically grounded assessment of fairness across ethnic groups.

3.5.4. McNemar’s Statistical Significance Testing

We apply McNemar’s test to determine whether performance differences between ethnic groups are statistically significant or merely the result of random variation [

33]. This non-parametric test is well suited for comparing paired binary classification outcomes from the same set of test samples [

34].

For each pair of ethnic groups (African vs. Central Asian), we construct a paired

contingency table comparing how each group classified the

same test samples. This paired design controls for sample-level variability [

33]. The contingency table is defined in

Table 5 as follows:

Cell

a contains samples that both groups classified correctly (concordant correct). Cell

b contains samples the Group B correctly classified but Group A misclassified. Cell

c contains samples that Group A correctly classified but Group B misclassified. Cell

d contains samples that both groups misclassified (concordant incorrect).

Table 6 provides the complete contingency tables showing values of

for each comparison, enabling full reproducibility. These tables reveal that concordant correct classifications (

a) dominate, with small discordant counts (

b and

c), consistent with high accuracy and minimal systematic disparity.

The table above reports McNemar p-values and odds ratios for all ethnic group comparisons (African vs. Central Asian, African vs. East Asian, and Central Asian vs. East Asian). In all cases, , indicating no statistically significant demographic bias.

McNemar’s test evaluates only the discordant pairs (

b and

c), which reflect true differences in performance [

35]. If both groups behave similarly, we expect that

. The chi-squared statistic is

computed with 1 degree of freedom. A

p-value of

indicates a statistically significant performance difference;

indicates no evidence of demographic bias.

While McNemar’s test evaluates statistical significance, it does not directly provide an odds ratio. We compute the odds ratio separately to measure effect size:

An odds ratio of indicates equal performance between the two groups. Values of indicate that Group A performs better, while values of indicate that Group B performs better. Values close to 1 (between 0.8 and 1.2) suggest minimal practical difference even when the sample sizes are large.

Together, McNemar’s

p-value and the odds ratio provide complementary insights into demographic fairness [

17].

For fairness in PAD systems, achieving both criteria demonstrates equitable performance across demographic groups.

3.5.5. Bootstrap Confidence Intervals

We employ bootstrap resampling with 1000 iterations to generate 95% confidence intervals for performance metrics across ethnic groups. This provides robust uncertainty quantification and validates whether the observed performance differences represent systematic bias or fall within expected statistical variation.

3.6. Rationale for Statistical Fairness Metrics

Our fairness evaluation framework employs three complementary statistical methods, each addressing distinct aspects of demographic bias.

The Coefficient of Variation (CoV) quantifies the relative dispersion of performance metrics across ethnic groups, providing a normalized measure of variability that remains interpretable across different metric scales. Unlike absolute performance gaps, the CoV accounts for baseline performance levels, making it suitable for comparing systems with different accuracy ranges.

McNemar’s statistical significance testing assesses whether the observed performance differences between ethnic groups exceed random variation, providing rigorous evidence for systematic bias rather than statistical noise. This test is specifically designed for paired categorical data (correct/incorrect classifications), making it ideal for comparing group-level classifier performance [

33].

Bootstrap confidence intervals quantify uncertainty in performance estimates through resampling, validating whether apparent fairness improvements represent genuine bias reduction or sampling artifacts. This technique is particularly valuable given the finite sample sizes available for each ethnic group in the test set.

Together, these three methods form a comprehensive statistical validation suite that measures dispersion (CoV), significance (McNemar), and uncertainty (bootstrap), providing stronger evidence than simple accuracy comparisons alone.

3.7. Standard Fairness Metrics

To complement our statistical framework, we compute three widely adopted fairness metrics from the algorithmic fairness literature.

Demographic Parity (DP) measures whether positive classification rates (accepting faces as genuine) are equal across groups:

where

G represents the ethnic group and

is the predicted label. Perfect Demographic Parity yields

.

Equalized Odds (EO) assesses whether true positive rates and false positive rates are consistent across groups:

This metric ensures that both genuine users and attackers experience similar error rates regardless of ethnicity.

Finally, we compute

AUC Gap as the maximum difference in the Area Under the ROC Curve between any two ethnic groups:

This measures the overall disparity in discriminative ability across demographic groups.

Results

Our fairness-aware system achieved substantial improvements across all standard metrics, as summarized in

Table 7. Demographic Parity violation decreased by 73% (0.067 → 0.018), indicating nearly equal acceptance rates across ethnic groups. Equalized Odds improved by 72%, demonstrating balanced error rates for both genuine presentations and attacks. The AUC gap of 0.012 indicates minimal discriminative ability differences across groups, well below the 0.025 threshold for acceptable fairness [

9].

These results complement our statistical validation (CoV analysis, McNemar’s test, and bootstrap intervals), providing converging evidence that our preprocessing and threshold optimization approach successfully mitigates demographic bias across multiple evaluation frameworks.

3.8. Fairness Evaluation and Bias Mitigation Effectiveness

We evaluate our system using established PAD performance metrics computed both globally and disaggregated by ethnic group to assess fairness. The Attack Presentation Classification Error Rate (APCER) measures the proportion of presentation attacks incorrectly classified as genuine presentations:

The Bona Fide Presentation Classification Error Rate (BPCER) measures the proportion of genuine presentations incorrectly classified as attacks:

We also compute the Average Classification Error Rate (ACER) as a balanced measure of overall performance:

The Equal Error Rate (EER) is reported as the operating point where .

For fairness evaluation, we compute these metrics separately for each ethnic group and calculate performance disparity measures using our novel statistical methods. We measure Demographic Parity by comparing positive classification rates across ethnic groups, and we evaluate equalized opportunity by assessing the consistency of true positive rates across groups. Our bias mitigation effectiveness is quantified through the percentage reduction in performance gaps:

3.8.1. Defining Performance Gaps

The

performance gap quantifies accuracy disparity across demographic groups. It is defined as follows:

For example, if the East Asian group achieves 95.5% accuracy and the African group achieves 92.7%, then

3.8.2. Understanding PerformanceGapBefore

PerformanceGapBefore represents the disparity in the baseline system without any fairness-aware adjustments. The baseline configuration includes the following:

Standard CLAHE preprocessing with a clip limit of 3.0, applied uniformly to all groups.

Standard gamma correction of 1.1, applied uniformly.

A single global decision threshold optimized on the combined validation set.

3.8.3. Understanding PerformanceGapAfter

PerformanceGapAfter reflects the disparity in the proposed fairness-aware system, which incorporates adaptive preprocessing and group-specific thresholds:

Adaptive CLAHE: Clip limit of 4.5 for African subjects, and 3.0 for all others.

Adaptive Gamma Correction: for African subjects, and for others.

Group-Specific Decision Thresholds:

Statistical significance is validated using our McNemar’s tests and bootstrap confidence intervals, ensuring that observed improvements represent genuine bias reduction rather than random variation. We also measure the fairness–security trade-off to ensure that bias mitigation does not compromise attack detection capabilities for any ethnic group.

3.9. Complete System Algorithm

Algorithm 1 presents the complete pseudocode of our fairness-aware Presentation Attack Detection (PAD) system, integrating ethnicity-aware preprocessing, multi-scale LBP feature extraction, classifier training, group-specific threshold optimization, and inference.

3.10. Practical Deployment Considerations

3.10.1. Ethnicity Label Acquisition

Our evaluation framework leverages the explicit ethnicity annotations provided in the CASIA-SURF CeFA dataset, enabling rigorous fairness assessment during development and validation. However, practical deployment raises important considerations regarding ethnicity label acquisition at inference time.

Three deployment strategies are feasible:

Manual self-identification during enrollment, where users voluntarily declare their ethnicity as part of the registration process, which is similar to demographic data collection in banking and healthcare systems.

Automatic ethnicity estimation using computer vision classifiers, although this approach introduces ethical concerns regarding algorithmic bias and privacy violations.

Threshold ensemble methods that apply all group-specific thresholds simultaneously and aggregate predictions, eliminating the need for explicit ethnicity classification.

| Algorithm 1 Complete pseudocode of the fairness-aware PAD system |

Input: Training images , validation , test with labels y, ethnicity e

Output: Attack predictions PHASE 1: ETHNICITY-AWARE PREPROCESSING Function PREPROCESS(I, e):

;

if then

else

return PHASE 2: MULTI-SCALE LBP FEATURE EXTRACTION Function EXTRACT_FEATURES():

features

for each in do

LBP_map ← UNIFORM_LBP()

features.append(SPATIAL_HISTOGRAM(LBP_map, ))

vector ← CONCATENATE(features) // 3,456 dimensions

return L2_NORMALIZE(vector)

PHASE 3: CLASSIFIER TRAINING classifier ← SGDClassifier(, class_weight=’balanced’)

classifier.fit() PHASE 4: GROUP-SPECIFIC THRESHOLD OPTIMIZATION thresholds

for each

do

classifier.decision_function()

// Minimize EER

thresholds[g]

Results: , , PHASE 5: INFERENCE WITH ETHNICITY-SPECIFIC THRESHOLDS

for each in do

score ← classifier.decision_function(x)

if score ≥ thresholds[e] then (LIVE)

else (ATTACK)

.append()

return

|

For this research, we prioritize the threshold ensemble approach for future deployment. This method computes classification scores using each group’s optimized threshold (, , ) and combines results through weighted voting or confidence averaging. This strategy maintains fairness benefits while avoiding the ethical and technical complications of ethnicity classification.

3.10.2. Mixed-Race and Ethnicity Misclassification

Mixed-race individuals and ethnicity misclassification present important fairness challenges. Our current framework treats ethnicity as discrete categories, which does not reflect the continuous spectrum of human diversity. If ethnicity labels are incorrectly assigned, the system applies suboptimal thresholds that may reintroduce bias.

To mitigate these concerns, we propose probabilistic threshold application, where uncertain cases receive blended thresholds based on confidence scores. For example, if automatic ethnicity estimation assigns a 60% probability for African and 40% for East Asian, the final threshold becomes

This soft assignment reduces the impact of misclassification while preserving fairness improvements.

Alternatively, conservative threshold selection can default to the most inclusive threshold (highest security sensitivity) when ethnicity is uncertain. Our analysis shows that using for all uncertain cases increases the false rejection rate by only 1.2% while maintaining security effectiveness.

3.10.3. Privacy and Ethical Implications

Collecting and processing ethnicity information raises significant privacy concerns, particularly in regions with historical discrimination or data protection regulations like the GDPR. Our framework does not require storing ethnicity labels beyond the initial threshold selection, and the threshold ensemble approach eliminates long-term ethnicity data retention.

We acknowledge that even ethnicity-aware preprocessing (different CLAHE parameters) could theoretically leak demographic information. However, these adjustments operate on image quality metrics that are universally applicable across contexts, and the preprocessing parameters themselves do not uniquely identify ethnicity.

For deployments where ethnicity collection is ethically or legally problematic, we recommend the threshold ensemble method combined with adaptive preprocessing that analyzes image properties (brightness distribution, contrast) rather than demographic categories. This approach maintains most fairness benefits while respecting privacy constraints.

4. Experiments and Results

This section presents a comprehensive evaluation of the proposed Presentation Attack Detection (PAD) system using the CASIA-SURF CeFA dataset, with a particular focus on fairness across different ethnic groups. The experiments aim to demonstrate not only the system’s effectiveness in detecting attacks but also its ability to mitigate demographic bias.

4.1. System Design and Setup

The PAD system uses specialized preprocessing techniques to account for variations in skin reflectance among ethnicities. More specifically, the brightness adjustment values were set at 4.5 for African subjects and 3.0 for others. The gamma correction values were set at 1.3 for African subjects and 1.1 for others. These adaptive settings, as shown in

Table 8, improve contrast and enhance texture patterns, critical for Presentation Attack Detection.

Feature extraction utilizes multi-scale Local Binary Patterns (LBPs) to extract fine-grained texture information that combines three spatial scales, yielding a 3456-dimensional feature vector per image. Classification was performed with Stochastic Gradient Descent (SGD) utilizing class-balanced weights to compensate for imbalance in the available data. Decision thresholds were optimized independently for each ethnic category to promote fairness without compromising security.

4.2. Dataset Processing and Data Leakage Prevention

We conducted all experiments using the complete CASIA-SURF CeFA dataset, which contains 89,998 images from 1607 subjects across three ethnic groups: East Asian (30,000 images), Central Asian (30,000), and African (29,998) [

36]. Each subject contributed four sessions, consisting of one bona fide facial image, two print attack images captured under different lighting conditions, and one video replay attack, enabling balanced evaluation across attack types.

4.2.1. Importance of Subject-Level Splitting

A critical design decision is the use of

subject-level rather than image-level splitting. Since each subject appears in multiple images, random image-level splits can cause the same individual to appear in both the training and test sets. This leads to identity leakage, allowing the classifier to memorize subject-specific facial features rather than learning true presentation attack cues [

37,

38]. Such leakage inflates reported accuracy and undermines fairness analysis.

CeFA encodes subject identity in the directory structure (P1_P2_P3_P4_P5), where P2 corresponds to the subject ID. We ensured that all images belonging to a given subject remained exclusively within one of the three splits (training, validation, testing), eliminating any possibility of identity overlap.

4.2.2. Data Splitting Strategy

We randomly partitioned the 1607 subjects into three groups using a stratified strategy that preserved the ethnic distribution across splits.

Table 9 summarizes the dataset division as follows:

Training: 80% of subjects (1286 subjects; 71,998 images);

Validation: 10% of subjects (160 subjects; 9000 images);

Testing: 10% of subjects (161 subjects; 9000 images).

Because each subject provided a fixed set of bona fide and attack images, the resulting splits preserved the original attack-type distribution (25% live, 50% print, 25% replay) without the need for manual balancing.

Table 9.

Distribution of subjects and images across dataset splits.

Table 9.

Distribution of subjects and images across dataset splits.

| Split | African | Central Asian | East Asian | Total Subjects | Images |

|---|

| Training | 400 | 429 | 457 | 1286 | 71,998 |

| Validation | 50 | 53 | 57 | 160 | 9000 |

| Testing | 50 | 54 | 57 | 161 | 9000 |

| Total | 500 | 536 | 571 | 1607 | 89,998 |

4.2.3. Preventing Data Leakage

We implemented multiple safeguards to ensure strict isolation between training, validation, and test data:

- (1)

Subject ID Verification

A verification script confirmed that no subject ID appeared in more than one split, guaranteeing identity isolation.

- (2)

Preprocessing Decisions Made Without Test Data

Ethnicity-aware preprocessing parameters, including CLAHE configurations (African: clip_limit = 4.5; others: 3.0) and gamma corrections ( vs. ), were tuned using only the training set and supported by the prior literature on skin reflectance characteristics across skin tones. No test images influenced the preprocessing choices.

- (3)

Threshold Optimization Restricted to Validation Data

Ethnicity-specific decision thresholds

were computed using validation scores only. These thresholds were frozen before testing.

- (4)

Hyperparameter Selection Without Test Exposure

Regularization parameters (e.g., ) and class-weight balancing were selected using training/validation only, ensuring that the test set remained untouched until the final evaluation.

- (5)

Fixed Random Seed for Reproducibility

All data splits were generated using a fixed random seed (random_state = 42), preventing iterative reshuffling to artificially boost accuracy, and enabling full reproducibility.

4.2.4. Handling Class Imbalance

Since CeFA contains more attack images (75%) than bona fide images (25%), we applied inverse-frequency class weighting during training rather than oversampling or synthetic image generation. Live samples were weighted approximately three times more heavily based on the training-set distribution, reducing bias toward the majority class while avoiding data leakage.

4.2.5. Fairness Implications

This rigorous subject-level splitting and leakage prevention strategy ensured that the PAD system was evaluated on unseen individuals rather than memorized identities. This is essential for demographic fairness analysis, as it provides an unbiased assessment of how well the system generalizes across different ethnic groups [

9,

17]. Such a methodology closely approximates real-world deployment conditions, where PAD systems must perform reliably on completely new users.

4.3. Overall System Performance

Figure 4 illustrates the spatial distribution of discriminative features across facial regions, revealing which areas contribute most significantly to presentation attack detection decisions for different ethnic groups and attack types.

The PAD system’s performance is shown in

Table 10. With an accuracy of 95.12% and an AUC of 98.55%, the suggested framework shows strong discriminatory power.

The low Equal Error Rate (5.32%) and the low values of APCER (4.55%) and BPCER (5.89%) further confirm that the system’s performance is highly effective and that it could be used in field authentication systems.

We compared our multi-scale LBP + SGD PAD system with four recent deep learning approaches to assess computational feasibility and deployment practicality. As shown in

Table 11, our method demonstrates three key efficiency advantages.

First, with only 3457 parameters, our system is approximately 49,063× smaller than SLIP and 800× smaller than LDCNet. This extreme compactness is achieved because LBPs use predefined texture operators rather than millions of learned network weights. Second, our method requires just 0.65 million FLOPs per image, which is nearly 24,000× less computation than SLIP’s 15.8 billion FLOPs. This reduction results from the simplicity of LBP histogram extraction and linear SGD classification, which rely on lightweight pixel comparisons and dot-product evaluations rather than large matrix multiplications.

In terms of runtime, our system processes 1346 images per minute (44.6 ms/image), enabling real-time performance even on low-power devices. Although the accuracy of 95.12% is approximately 2% lower than SLIP’s 97.1%, this difference is outweighed by significant practical advantages: the entire pipeline—feature extraction, training, and inference—is lightweight and hardware-agnostic. This makes our PAD system highly suitable for deployment on smartphones and edge devices that are commonly used across African regions, where computational resources and energy budgets are limited.

These results validate that carefully engineered handcrafted features, combined with an efficient linear classifier, can deliver a strong balance between security performance and computational efficiency. This trade-off is essential for equitable and accessible PAD deployment in resource-constrained African contexts.

4.4. Fairness Evaluation Across Ethnic Groups

To assess fairness, we computed performance metrics separately for each ethnic group.

Table 12 shows that the accuracy disparity between African and East Asian subjects is only 0.75%, indicating balanced performance.

To further assess classification consistency across demographic groups,

Figure 5 presents confusion matrices with different ethnicity, demonstrating balanced true positive and false positive rates across African, Central Asian, and East Asian subjects.

4.5. Statistical Validation of Fairness

We adopted three complementary statistical approaches to verify fairness:

We determined the relative performance difference between groups using the Coefficient of Variation (CoV) (

Table 13). The bulk of the CoV values falling within the small-to-medium range confirms equitable performance.

In addition to the aggregate error statistics reported above, receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis provides a threshold-independent view of classification performance across demographic groups.

Figure 6 presents the ROC curves for African, Central Asian, and East Asian subjects, illustrating consistently high discriminative capability across all ethnicities.

To complement the ethnicity-specific analysis,

Figure 7 illustrates the overall ROC curve of the proposed PAD system. The strong separation between bona fide and attack presentations further confirm the high discriminative capability of the model across operating thresholds.

- (2)

Statistical Significance Testing

McNemar’s test confirms that the observed group disparities are statistically insignificant

(

Table 14).

Figure 8 provides complementary evidence of fairness through t-SNE visualization of the learned feature space, demonstrating that the 3456-dimensional LBP representations cluster by attack type rather than ethnicity, confirming unbiased feature extraction across demographic groups.

- (3)

Bootstrap Confidence Intervals

Additionally, bootstrap-based 95% confidence intervals validate the accuracy distributions across ethnic groups.

Figure 9 demonstrates statistically overlapping performance ranges, providing robust evidence that observed fairness improvements are not artifacts of sampling variation.

4.6. Detection Across Attack Types

We also analyzed performance across attack modalities.

Table 15 shows consistent performance across printed photos, video replays, and bona fide presentations.

4.7. Error Analysis and Misclassification Patterns

To understand system limitations and identify failure modes,

Figure 10 presents representative misclassified samples with corresponding confidence scores and error magnitudes, revealing common challenging scenarios such as low-light conditions, extreme head poses, and high-quality print attacks that evade texture-based detection.

4.8. Comparative Analysis: Fairness Impact and Method Positioning

To evaluate the specific contribution of our fairness-aware techniques, we conducted comparative experiments using three systems on the CASIA-SURF CeFA dataset: (1) a standard LBP baseline without fairness enhancements, (2) our complete fairness-aware LBP pipeline, and (3) the ResNet18 deep learning baseline from the official CeFA benchmark [

11]. The LBP baseline uses the same 3456-dimensional multi-scale LBP features as our method but applies uniform preprocessing (CLAHE clip limit 3.0 and gamma correction 1.1) and a single global decision threshold optimized for overall EER. The ResNet18 model follows the full implementation of Liu et al. [

11], using the RGB modality with standard augmentation and cross-entropy loss.

Across all three approaches, our fairness-aware pipeline achieved the most balanced performance across demographic groups. The LBP baseline obtained 95.34% overall accuracy but exhibited a 3.41% gap between East Asian and African subjects, with McNemar’s test indicating a statistically significant difference (). The ResNet18 baseline achieved the highest raw accuracy (96.78%) yet showed an even larger demographic gap of 4.08%, which was also statistically significant (). These findings indicate that higher accuracy alone does not guarantee improved fairness in PAD systems.

In contrast, our fairness-aware LBP system achieved 95.12% overall accuracy while reducing the maximum demographic performance gap to only 0.75%, with McNemar’s test showing no statistically significant differences across all ethnic pairs (). Intermediate experiments further showed that ethnicity-aware preprocessing alone (CLAHE 4.5 and gamma 1.3 for African subjects) reduced the gap from 3.41% to 1.89%, while the complete system combining preprocessing with group-specific thresholds achieved the final 0.75% gap. This demonstrates that both components play complementary roles in promoting demographic equity.

Beyond fairness, our approach also excels in computational efficiency. The fairness-aware LBP system processes approximately 1346 images per minute on standard CPU hardware, whereas ResNet18 requires GPU acceleration and achieves about 450 images per minute under the same evaluation conditions. This 3× efficiency advantage highlights the deployability of our approach in the low-resource settings that are common across African contexts.

Overall, these results support our core conclusion: fairness in PAD requires targeted design choices rather than reliance on accuracy alone. By integrating ethnicity-aware preprocessing with group-specific decision thresholds, our approach achieves significant fairness improvements while maintaining computational efficiency suitable for real-world deployment on mobile and edge devices.

5. Discussion

The test results show great success in building fairness-aware Presentation Attack Detection systems through careful design methods. The complete testing on the CASIA-SURF CeFA dataset proves that the approach works well for both security and fairness goals for African populations.

The most important achievement is the major reduction in unfair treatment between ethnic groups while maintaining strong overall performance. The system achieves 95.12% accuracy, with only a 0.75% difference between African and East Asian subjects, representing a 75.6% reduction in unfair differences. This result proves that fairness and good performance can work together through smart system design.

The ethnicity-aware image processing approach works very effectively in solving the technical challenges of building PAD systems for different ethnic groups. The adaptive brightness settings (4.5 for African subjects versus 3.0 for others) and ethnicity-specific gamma correction (

= 1.3 versus

= 1.1) successfully improve the quality of texture analysis for different skin colors. This technical innovation builds upon recent advances in inclusive computer vision [

39] while representing the first systematic application to PAD systems.

Statistical proof of fairness through novel evaluation methods provides strong evidence for bias elimination. All McNemar’s test comparisons show p-values ≥ 0.05, confirming no statistically meaningful bias between ethnic groups. The Coefficient of Variation analysis shows most performance measures achieving low demographic differences (accuracy CoV: 0.40%), while bootstrap confidence intervals show overlapping performance ranges across all groups. This complete statistical validation establishes a new standard for thorough fairness assessment in PAD research.

The group-specific threshold optimization provides a practical solution for fair classification in biometric systems. The calculated thresholds (

,

,

) ensure balanced error rates across demographic groups while keeping security strong. This approach extends recent work on fair classification [

30] specifically to the PAD field, providing measurable bias reduction without losing attack detection abilities.

The performance results across different attack types prove the effectiveness of the multi-scale LBP approach. Achieving 95.89% accuracy for print attack detection and 95.45% for replay attack detection shows strong security performance. Most importantly, the 94.12% accuracy for real face recognition shows substantial improvement in user acceptance rates, directly helping legitimate users across all ethnic groups.

The processing speed results prove the practical usefulness of this approach for deployment in places with limited resources. Processing rates exceeding 1000 images per minute with 3456-dimensional feature representation show that fairness-aware PAD systems can meet real-time performance needs. This efficiency makes the system suitable for mobile deployment in African contexts, where computer resources may be limited [

40].

The success of traditional LBP methods in achieving fairness goals challenges common beliefs about needing deep learning approaches for effective bias reduction. The results show that well-designed handcrafted features, combined with thoughtful preprocessing, can achieve competitive performance while offering better understanding and processing efficiency compared to complex deep learning models [

41].

The comparative analysis reveals several important insights about fairness–performance trade-offs in PAD systems. First, higher overall accuracy does not guarantee fairness; the ResNet18 baseline achieved 96.78% accuracy but showed a 4.08% gap favoring non-African subjects. Second, preprocessing-level interventions provide more sustainable fairness improvements than post hoc corrections, as evidenced by the 78% gap reduction (3.41% → 0.75%) achieved through ethnicity-aware CLAHE and gamma correction. Third, group-specific threshold optimization eliminates statistically significant bias even when residual performance differences exist, demonstrating that fairness mechanisms can operate independently of feature extraction quality.

Our work complements rather than contradicts recent fairness advances. FairSWAP’s data augmentation strategies [

9] could be combined with our preprocessing techniques for potentially enhanced fairness. Similarly, the ABF metric could supplement our statistical evaluation framework. However, our preprocessing-first approach addresses a fundamental challenge, ensuring optimal image quality across skin tones that data augmentation and training constraints cannot fully resolve. This positions our contribution as a foundational fairness layer applicable across PAD architectures, from traditional LBPs to state-of-the-art deep learning systems.

The systematic nature of this bias reduction approach provides valuable insights for the broader biometric systems field. Rather than depending on corrections made afterward or data balancing strategies, the preprocessing-level improvements address bias at its source. This approach offers a more sustainable and theoretically sound solution to demographic fairness challenges in biometric technologies.

The use of the statistical fairness evaluation framework addresses an important gap in current PAD research, where fairness assessment often relies on simple accuracy comparisons. The three-method approach (CoV analysis, McNemar’s testing, and bootstrap confidence intervals) provides complete bias measurement tools that can be applied across different PAD systems and datasets, contributing methodological advances to the field.

The implications extend beyond technical performance to broader questions of inclusive technology design. Our findings support the potential for establishing a fair biometric system through systematic algorithmic implementations that can function across various populations worldwide. By demonstrating that it is possible to have demographic equity in the system, we believe that this will be a valuable addition to the ongoing conversation around fair AI systems that universally work for all users regardless of demographic background [

39].

Our evaluation was conducted exclusively on the CASIA-SURF CeFA dataset, which represents a deliberate methodological choice rather than an oversight. CeFA remains the only publicly available PAD dataset providing explicit ethnicity annotations across African, Central Asian, and East Asian populations, making systematic fairness evaluation possible [

11]. Alternative datasets like OULU-NPU, SiW, and CASIA-FASD lack demographic metadata, preventing rigorous bias measurement and group-specific performance analysis.

Cross-dataset evaluation would assess generalization but not fairness, as these datasets do not provide ethnicity labels for disaggregated analysis. While our preprocessing techniques (ethnicity-aware CLAHE and gamma correction) are theoretically transferable to other datasets, validating fairness improvements requires ground-truth demographic information that is unavailable in existing benchmarks. This gap in available evaluation resources represents a broader limitation in the PAD research community, highlighting the urgent need for demographically annotated datasets beyond CeFA.

Regarding comparisons with fairness-aware methods like FairSWAP [

9] and Accuracy Balanced Fairness (ABF), direct experimental comparison is constrained by implementation availability and computational resource differences. FairSWAP requires deep CNN training with specialized data augmentation pipelines, while our LBP-based approach operates on handcrafted features. Future work should benchmark against these methods when implementations become publicly available and computational resources permit large-scale deep learning experiments.

Our results support the effectiveness of the Africa-focused research plan. We have shown that by focusing specifically on under-researched users, we were able to design solutions that hold benefit for the entire system. The ethnicity-aware methodologies designed for Africans provide improvements for users in all ethnic groups, implying that it is better to adhere to inclusive design principles to create better-performing systems as a whole, rather than trying to allow for the needs of minority users.

6. Conclusions and Future Work

This paper presents a complete approach to fairness-aware Presentation Attack Detection using Local Binary Patterns, specifically designed to address demographic bias affecting African populations. This research makes three primary contributions to the PAD field: novel ethnicity-aware preprocessing techniques, group-specific threshold optimization, and statistical frameworks for thorough fairness evaluation.

The ethnicity-aware preprocessing approach, featuring adaptive brightness settings and gamma correction optimized for different skin light reflection properties, successfully addresses fundamental technical challenges in cross-demographic PAD deployment. Group-specific threshold optimization ensures fair error rates across ethnic groups while maintaining security effectiveness, as shown through a 75.6% reduction in demographic performance differences.

The introduction of Coefficient of Variation analysis, McNemar’s statistical testing, and bootstrap confidence intervals for PAD fairness evaluation gives the research community strong methodological tools for bias assessment. These statistical frameworks offer more complete fairness evaluation than traditional accuracy-based comparisons, enabling systematic bias detection and reduction validation.

Test results on the CASIA-SURF CeFA dataset show that lightweight, understandable approaches can achieve both fairness and performance goals. The system achieves 95.12% accuracy, with only a 0.75% accuracy difference between African and East Asian subjects, while maintaining processing speeds exceeding 1000 images per minute suitable for resource-limited deployment scenarios.

The practical implications of this work extend beyond technical performance to inclusive biometric system design principles. The methodology demonstrates that demographic fairness can be secured through algorithmic revisions instead of being reliant on massive data alteration or special-purpose hardware, which makes fair PAD systems easier to use more routinely in different contexts of deployment.

6.1. Limitations and Future Work

While the system performs excellently for the tested attack types, certain limitations exist regarding attack coverage and deployment considerations. The LBP-based approach works best against 2D presentation attacks, including printed photos, screen replays, and digital images. The texture analysis excels at finding printing problems, screen patterns, and surface issues typical of these simple spoofing methods.

However, the method shows reduced effectiveness against sophisticated 3D presentation attacks, including high-quality silicone masks, latex prosthetics, 3D-printed faces, and advanced makeup techniques. These attack types create real 3D face shapes and can copy skin textures in ways that texture analysis might not easily detect [

42].

The system also cannot handle deepfake videos, live person impersonation, or attacks requiring vital sign detection. These attack types need different analysis methods that examine movement over time or physiological signals that the current approach does not include [

21].

For real-world deployment, the system requires explicit ethnicity information to choose appropriate decision thresholds. This requirement creates practical challenges in situations where ethnicity classification might be inappropriate, or where automatic ethnicity detection adds system complexity.

6.2. Future Research Directions

To address these limitations, several research extensions are planned. First, extending fairness-aware preprocessing techniques to deep learning systems could combine systematic bias reduction with advanced attack detection abilities. Multi-modal networks using regular cameras, depth sensors, and infrared could catch advanced 3D attacks while maintaining fairness improvements [

16].

Second, investigating hybrid approaches that combine LBP understanding with physiological signal detection addresses both fairness and advanced attack coverage. Recent advances in remote photoplethysmography (rPPG) for vital sign detection [

21] could be combined with ethnicity-aware processing to detect live person impersonation and deepfake attacks.

Third, integration of temporal analysis could improve the detection of replay attacks and deepfakes. Adding motion analysis and facial tracking to fairness-aware preprocessing could provide protection against both simple 2D attacks and complex video-based spoofing while maintaining demographic fairness.

Fourth, collaboration with African institutions to develop comprehensive datasets with increased African representation across diverse attack types remains essential. While datasets like CASIA-SURF CeFA provide good ethnic representation, building partnerships with African universities, research centers, and technology organizations could enable the collection of larger African sample sizes and region-specific attack scenarios that better reflect deployment contexts across the continent.

Fifth, cross-dataset evaluation on widely used public benchmarks such as OULU-NPU, SiW, and OCMI [

43] should be conducted to assess generalization performance and enable direct comparisons with existing methods. While our current evaluation focuses on fairness assessment using CeFA’s demographic annotations, extending evaluation to multiple datasets will validate the robustness of our fairness-aware preprocessing approach across different capture conditions and attack scenarios.

Finally, developing deployment solutions that make group-specific thresholds practical for real use includes automatic ethnicity detection systems or ensemble methods that use all thresholds together without requiring user classification by ethnicity.

The methods established in this research provide a clear framework for measuring and reducing demographic bias in Presentation Attack Detection systems. As biometric technologies continue to expand globally, ensuring fair and inclusive system design becomes increasingly important for equal access to digital services and security technologies. This work contributes both technical innovations and methodological frameworks toward achieving this important goal.