Abstract

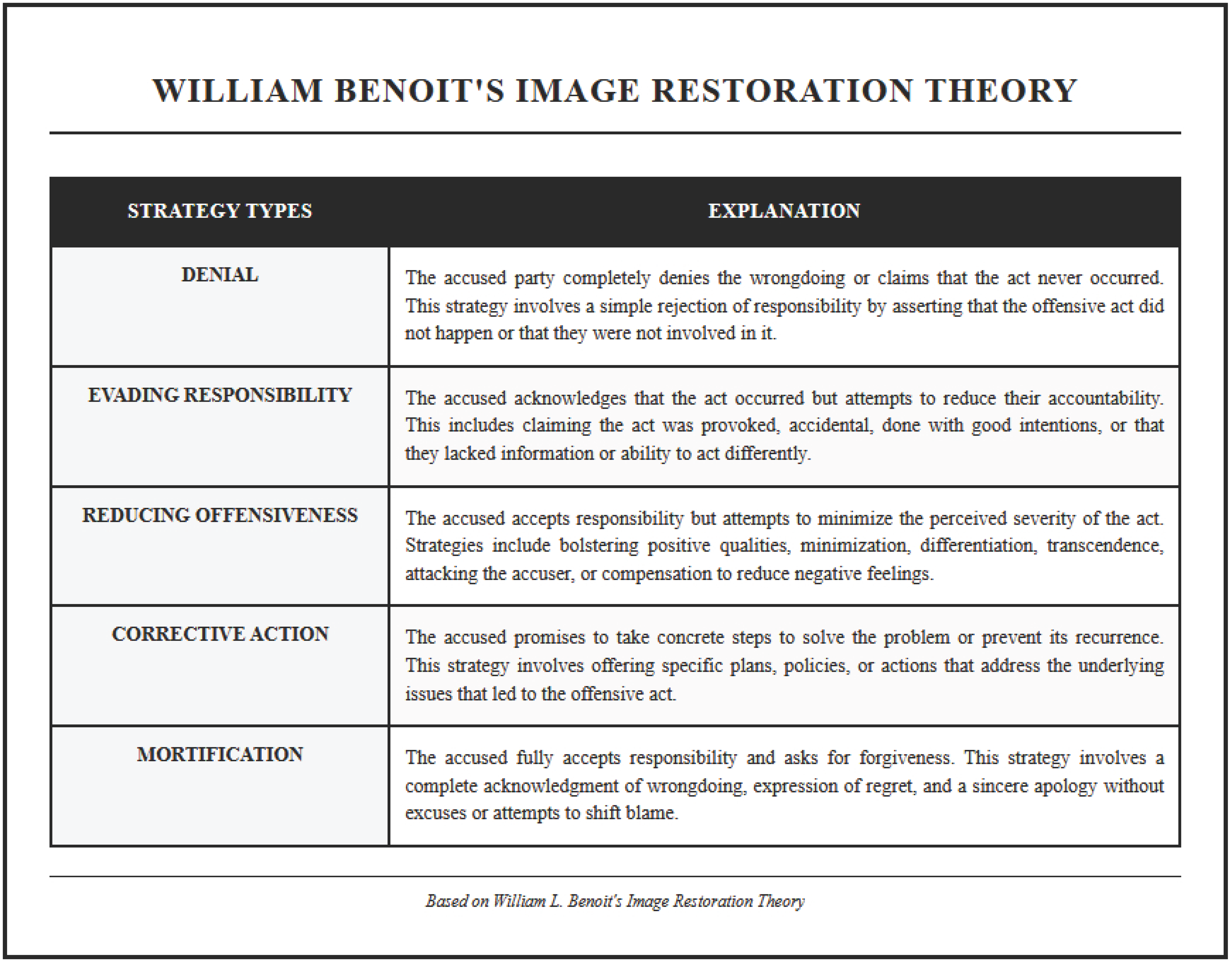

This study explores the emergent dynamics of knowledge sovereignty within organisations following data breach incidents. Using qualitative analysis based on Benoit’s image restoration theory, this study shows that employees do more than relay official messages—they actively shape information governance after a cyberattack. Employees adapt Benoit’s response strategies (denial, evasion of responsibility, reducing offensiveness, corrective action, and mortification) based on how authentic they perceive the organisation’s response, their identification with the company, and their sense of fairness in crisis management. This investigation substantively extends extant crisis communication theory by showing how knowledge sovereignty is shaped through negotiation, as employees manage their dual role as breach victims and organisational representatives. The findings suggest that employees are key actors in post-breach information governance, and that their authentic engagement is critical to organisational recovery after cybersecurity incidents.

1. Introduction

Data breaches represent increasingly prevalent and consequential organisational crises, with significant implications for both technical infrastructure and human capital management [1]. Whilst substantial scholarly attention has focused on technical remediation strategies and corporate communication approaches following breach incidents, comparatively limited research has examined the distinctive role of employees as active participants in post-breach knowledge governance processes [1,2]. This research gap is particularly significant given the unique positioning of employees as both potential victims of data compromises and simultaneous organisational representatives tasked with maintaining stakeholder relationships during periods of informational uncertainty.

The present study addresses this theoretical and empirical gap by examining how employees navigate knowledge sovereignty challenges following organisational data breaches. Drawing on [3] image restoration theory whilst extending its application to distributed agency contexts, we explore how employees actively influence knowledge governance following cybersecurity incidents. In doing so, this investigation contributes to emergent theoretical perspectives on employee-driven information governance [4] whilst simultaneously extending crisis communication frameworks to incorporate distributed agency dynamics [5].

Although many organisations implement cybersecurity frameworks such as ISO/IEC 27001 (Information security, cybersecurity and privacy protection—Information security management systems—Requirements, Standard’s Number 3, 2024) [6], The NIST Cybersecurity Framework (CSF) 2.0, published by the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) in Washington D.C., USA, on 26 February 2024, provides voluntary guidance for organizations to better manage and reduce cybersecurity risks or CIS Controls, technical compliance alone does not guarantee immunity from breaches. Organisational responses, including employee engagement in information governance, remain critical in mitigating reputational risks after incidents through the European Union Agency for Cybersecurity. This role of employees in shaping post-breach organisational narratives is still under-explored in relation to cybersecurity policies, despite the growing adoption of procedural frameworks such as ISO 27001.

This paper is structured as follows: First, we establish the theoretical foundations of knowledge sovereignty and information governance disruption within post-breach organisational contexts. Next, we outline our methodological approach, detailing data collection and analytical procedures. Subsequently, we present empirical findings organised around key dimensions of employee knowledge sovereignty practices. Finally, we discuss theoretical contributions and practical implications, concluding with limitations and directions for future research. The context of the companies that participated in the research comprises organisations located in Colombia.

2. Theoretical Background

A breach can erode public confidence in an organisation, leading to a decline in customer retention and challenges in acquiring new clients. A significant proportion of data breaches arise from the exploitation of security vulnerabilities. Among the most prevalent are as follows: Inadequate API security: Unsecured endpoints and insufficient authentication mechanisms often expose systems to unauthorised access, enabling threat actors to retrieve sensitive data. Insecure coding practices: The inadvertent inclusion of credentials within source code or the failure to encrypt confidential information may render software highly susceptible to exploitation. Weak authentication protocols: The absence of robust authentication methods—such as passkeys or two-factor authentication (2FA)—facilitates password guessing or brute-force attacks, thereby allowing unauthorised intrusion into systems and databases. Third-party dependencies: The use of vulnerable open-source libraries and external software components poses additional risks. Adversaries frequently exploit weaknesses in these dependencies to penetrate otherwise secure environments.

2.1. Knowledge Sovereignty and Employee Agency in Post-Breach Contexts

The evolving concept of knowledge sovereignty represents a critical dimension of organisational resilience following data breach incidents [7]. In contrast with traditional knowledge management paradigms that emphasise centralised institutional control, knowledge sovereignty recognises the distributed nature of informational authority across organisational ecosystems [8]. Within post-breach environments specifically, employees navigate complex dual roles as both vulnerable data subjects and organisational representatives, creating unique tensions in knowledge governance practices [1].

As [9] articulate, “The bifurcated position of employees—as both potential breach victims and institutional representatives—establishes a distinctive cognitive architecture that fundamentally shapes information dissemination practices following cybersecurity incidents” (p. 317). This duality transforms conventional understandings of employee agency, particularly in circumstances where official organisational narratives diverge from employees’ lived experiences of data vulnerability [10]

Research by [2] demonstrates that employees develop sophisticated heuristics for assessing organisational transparency following breach events, with perceived authenticity directly influencing their willingness to align with institutional response strategies. Their longitudinal study of 17 organisations across various sectors revealed that employees engage in what they term “sovereignty-asserting behaviours” when institutional responses are perceived as inauthentic or misaligned with employee security concerns. These behaviours include selective information sharing, counter-narrative development, and strategic ambiguity when discussing breach events with external stakeholders.

Recent discussions on knowledge sovereignty increasingly emphasise the importance of integrating ethical, legal, and governance considerations into post-breach information management, especially as organisations adopt advanced technologies under the Industry 4.0 paradigm [7,8]. The use of AI-driven systems for threat detection, incident response, and communication amplifies these challenges, as algorithmic decision making can introduce new forms of opacity and bias into knowledge governance [11]. Ethical data stewardship and transparency in AI-assisted processes are therefore critical dimensions of employee trust and engagement in post-breach contexts. Employees’ perceptions of procedural justice and organisational authenticity are increasingly shaped not only by human-led actions but also by how AI systems handle sensitive information during and after cybersecurity incidents [9]. Addressing these concerns requires a holistic approach that combines robust governance structures with transparent AI deployment and strong ethical safeguards.

By further expanding this theoretical framework, [12] propose that knowledge sovereignty emerges as a form of psychological self-protection in breach contexts, where employees seek to establish informational boundaries and control mechanisms that restore a sense of agency compromised by the breach itself. Their conceptualisation of “post-breach agency restoration” (PBAR) identifies four distinct patterns through which employees reclaim knowledge sovereignty: reciprocal transparency demands, information verification practices, counter-narrative development, selective disclosure strategies.

Each of these patterns represents a distinct manifestation of knowledge sovereignty that dynamically shapes organisational information governance following breach events [12].

2.2. Information Governance and Knowledge Management Disruption Following Data Breaches

The disruption of established knowledge management systems following data breaches represents a second theoretical domain essential for understanding employee-driven information governance [1]. Traditional models of organisational knowledge management emphasise structured information flows, codified knowledge repositories, and prescribed information-sharing protocols [13]. However, breach events fundamentally disrupt these systems, creating what [4] term “knowledge governance vacuums” wherein established informational authorities are temporarily suspended.

Within these governance vacuums, employees become critical nodes in reconfigured knowledge networks. As [4] explain, “Data breach incidents fundamentally alter both formal and informal knowledge flows within organisations, temporarily suspending established hierarchies of informational authority and creating spaces for emergent knowledge governance structures” (p. 83). Their comparative analysis of pre-breach and post-breach knowledge networks across 12 organisations demonstrates significant reconfigurations in information flow patterns, with employees demonstrating increased autonomy in knowledge dissemination decisions.

This governance disruption simultaneously affects both explicit and tacit knowledge domains. While explicit knowledge management disruptions manifest in altered documentation practices and information classification protocols, tacit knowledge disruptions occur within interpersonal knowledge-sharing networks [14]. As Belsis and colleagues (2022) note, “The erosion of trust following breach events disproportionately impacts tacit knowledge flows, with employees demonstrating heightened selectivity in verbal information sharing and creating informal knowledge enclaves based on perceived trustworthiness” (p. 418).

The concept of “knowledge resilience” emerges as particularly salient in this theoretical domain. [11] define knowledge resilience as “the capacity of organisational knowledge systems to maintain functional integrity while simultaneously adapting to security disruptions” (p. 236). Their framework identifies employee agency as the primary determinant of knowledge resilience following breach events, with particular emphasis on employees’ capacity to: (1) maintain critical knowledge flows during disruption, (2) identify and protect vulnerable knowledge assets, (3) distinguish between legitimate and illegitimate knowledge sharing requests, (4) re-establish trusted knowledge pathways following breaches.

Importantly, [11] distinguish between reactive knowledge governance (focused on containing information leakage) and regenerative knowledge governance (focused on rebuilding robust information flows). Their empirical findings suggest that organisations emphasising reactive governance strategies experience prolonged knowledge disruption, while those facilitating employee-driven regenerative governance demonstrate accelerated knowledge system recovery.

Building upon this distinction, [15] propose the concept of “information governance maturity” as a framework for assessing organisational capacity to manage knowledge disruptions following breaches. Their maturity model incorporates five progressive levels: (1) ad hoc responses, characterised by fragmented uncoordinated knowledge management responses; (2) defined protocols: featuring standardised but inflexible knowledge governance procedures; (3) integrated systems, demonstrating coordinated technical and human knowledge management components; (4) quantitatively managed, employing metrics to assess and optimise knowledge governance effectiveness; (5) optimising, continuously improving knowledge governance through systematic learning and adaptation.

Organisations demonstrating higher maturity levels exhibit significantly lower periods of knowledge disruption following breach events, with employee engagement in governance processes serving as the primary differentiator between high and low maturity organisations [15].

2.3. Business Reputation Management and Cybersecurity

Business reputation is a key intangible asset that directly influences the success and sustainability of organisations. According to [16], reputation is defined as the collective perception of a company by its stakeholders, which is based on the evaluation of its past performance, its behaviour in critical situations, and future expectations. Business reputation affects various aspects, from customer loyalty to access to capital and talent attraction [17].

In business environments, inadequate security practices can lead to data breaches that can have significant consequences for both the company and the entity whose data is affected. Cybercriminals take advantage of tactics such as ransomware and phishing through attack techniques such as zero-day, man in the middle, and identity theft to hijack company data and demand money through extortion for the rescue. The foregoing has led to government entities of governments such as that of the United States of America issuing a guide in 2023 to stop the ransomware-type attack through the National Security Agency [18]. Different academic studies have addressed the consequences of cybersecurity incidents in organisations [19,20,21,22].

Cybersecurity, in this context, is defined as the set of activities, processes, skills, and capabilities aimed at protecting information and communication systems, as well as the information contained therein, against damage, unauthorised uses, modifications, or exploitations [23]. A cybersecurity breach is an event that compromises the confidentiality, integrity, or availability of an information system or its security policies or procedures [24] and, depending on its magnitude, can have economic impacts, regulatory notification, repair and compensation to the client, litigation, the loss of market value or investments, regulatory fines, extortion payments, and the loss of business [25].

One of the good practices used by incident management teams is risk management, which consists of identifying and controlling vulnerabilities in information systems (IS), including risk identification, risk assessment, and risk control [26]. A risk assessment evaluates what could go wrong, the likelihood of such an incident occurring, and the damage if the incident occurs [27]). Directly addressing the security of companies to identify threats and vulnerabilities in order to prevent future events through risk assessments is an important first step that should precede financial allocations [28,29]

Cybersecurity from a data breach perspective, considering risk management, has focused on models that emphasise mitigation and recovery [30], as well as the importance of implementing business continuity and cyber incident response plans [31]. Ref. [32] provide a clear example of the above statement by putting into practice the models of protection motivation theory (PMT) by technical teams to manage data breaches and the organisation’s response strategies (ORS) to address security breaches through good corporate reputation practices.

3. Methodology

In this study, as recommended in the literature, we analysed 200 companies in highly digitised sectors that were willing to participate in this analysis [33]. We had a secondary data collection before interviewing participants who should represent multiple hierarchical levels of the organisations to reduce elite bias [34]; subsequently, the interview protocol would be applied based on previously defined theoretical categories and related to the technical aspects of cybersecurity, impact on employees, and strategies adopted in the midst of the crisis and post-crisis. After that, we performed the cross-case analysis using a first and second-level coding and categorisation system that allows for iteration between data and theory [35]

The preliminary findings will be presented to both participants and academics and experts in the area to clarify conflicts and refine the accuracy of the analysis [36]. This research is qualitative and uses case studies in organisations from different sectors of the economy in emerging countries that have suffered cyberattacks with some type of data exposure or leakage as references.

3.1. Case Selection and Research Context

Three criteria were used to select the cases: (a) the sector and size of the organisation, the case selection was carried out so that (b) illustrative cases were presented, both positive and negative or successful and failed [37,38], and (c) all cases were from Colombia, see Table 1.

Table 1.

Colombian economic sector overview.

It is important to note that the perspectives shared by participants reflect their individual professional opinions and the consensus reached among those responsible for information governance processes, and do not necessarily represent the official positions or institutional policies of their employing organisations.

3.2. Data Collection

Data collection was carried out through interviews between August 2024 and February 2025, where structured and semi-structured responses were obtained from a sample of 200 profiles from different organisations (operational, administrative, and strategic). Also, cybersecurity incident documents published in different sources between 2024 and 2025 were collected (see Table 2).The interviews focused on understanding (a) security technical aspects to identify technological gaps in the infrastructure, (b) response and impact on work teams to understand how the crisis was managed within the organisation, and (c) to know the strategies implemented to safeguard the reputation and image by the organisations; for this purpose, different frameworks categorised with questions according to the interests of the case study and the scientific literature were analysed, (see Table 3). From there, an application instrument was designed for the interviews (see Appendix A).

Table 2.

Colombian organisations that suffered cyberattacks with data leaks (2024–2025).

Table 3.

Qualitative analysis framework for organisational response to cyberattacks.

Due to the sensitive nature of cybersecurity incidents and to protect both organisational and individual participants, all company names and employee identities have been anonymised. Data are not shared in an open repository; however, interview recordings and full transcripts are securely archived. Our analysis identified patterns related to organisational size. In larger organisations, employee-driven knowledge sovereignty tends to be more formalised, with specialised roles and hierarchical structures, whereas in smaller firms it manifests through informal knowledge sharing, cross-functional responsibilities, and greater adaptability and agility.

3.3. Data Analysis, Rigor, and Transparency

Following the method implemented by previews studies (e.g., [39,40] we conducted a literature review and identified three main categories for our study. Then we combined image restoration theory, social identity theory, and procedural justice to develop interview questions shown in Table 3. These perspectives helped identify key dimensions of employee responses and guided the interpretation of emerging patterns during analysis.

To mitigate potential elite bias, at least two interviews were conducted in each participating company, one with a manager or senior executive (e.g., CISO, IT director, or business unit head), and one with an operational or administrative employee. This approach allowed us to capture diverse perspectives across organisational levels. In addition, interview data were triangulated with company reports and public disclosures to enhance the reliability of the findings.

For the analysis of the results, the responses sent in the form (Appendix A) were first taken and related to the following framework designed and proposed in Table 3 for our purpose.

During the data collection step, we paid close attention to the consistency and authenticity of participants’ responses, using triangulation across cases and sources to strengthen the validity of the finding [34]. Questions exploring emotional reactions and trust dynamics were included to capture employees’ self-reported perceptions, which are essential for understanding the social and psychological dimensions of post-breach contexts. Then, to analyse the data, coding was performed using the taxonomy developed [41] and the Atlas T.I. software version 25, which allowed for the identification of patterns in the interviews (see Table 4).

Table 4.

Coding for data analysis.

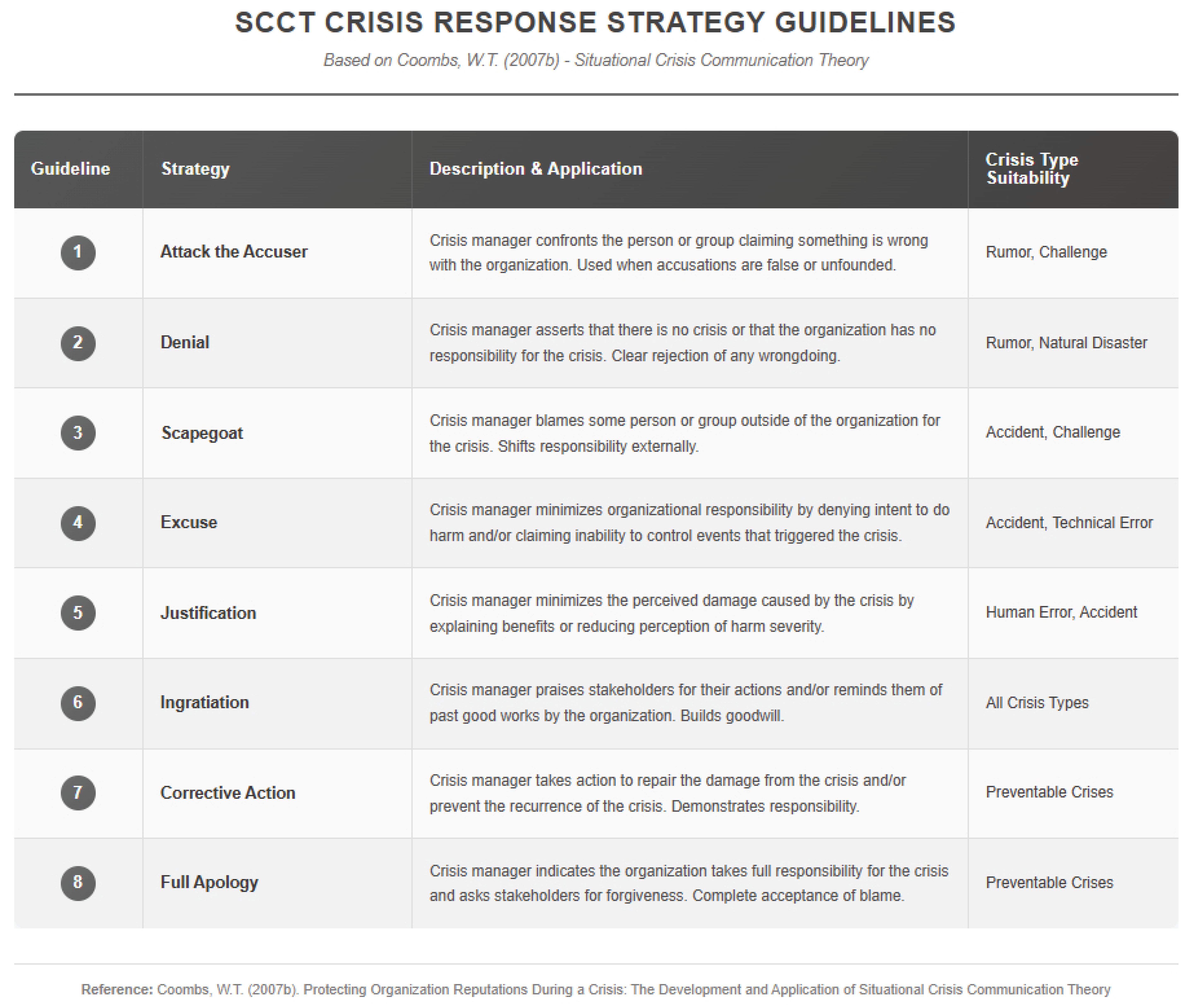

Once patterns were identified, relationships were established with the variables defined in the situational crisis communication theory (SCCT) of [42] (see Appendix B) and the image restoration theory [3] (see Appendix C) to analyse the extent to which each variable of the coded taxonomy data set was associated with a theme or factor that allows cyberattacks and data leaks to be related to the impact on employees and the reputation of organisations.

The coding allowed us to identify patterns and relationships between the different levels of analysis. Below is a summary of the frequency of the codes in each dimension (see Table 5).

Table 5.

Frequency of codes by dimension.

Table 6 summarises the research process adopted in this study.

Table 6.

Research process overview.

4. Results

The qualitative analysis allowed us to identify recurring trends and perceptions in the three dimensions analysed. The most relevant findings are summarised below:

4.1. Impact on the Technical Aspects of Cybersecurity

The data showed that most companies had vulnerabilities in updating their systems and implementing adequate security protocols. A direct relationship was observed between the lack of investment in technology and the magnitude of the cyberattack. Interviewees stated that, in many cases, the response to the incident was reactive and uncoordinated, which aggravated the reputational damage. Table 7 introduces the main attacks, their incidences, and the overview of employees’ technical responses.

Table 7.

Main attacks, incidences, and technical responses.

4.2. Impact on Employees

The reputational impact on employees was mainly manifested through high levels of stress and a significant loss of confidence, both internally and in the external perception of their professional performance. Testimonials revealed that the uncertainty generated by the exposure of personal data affected the work environment and motivation, impacting productivity and professional image. Table 8 introduces the main impact on work teams according to two main types of companies.

Table 8.

Reported impacts on work teams by type of company sector.

4.3. Communication Strategies and Restoration of Corporate Image

The review of communication strategies revealed deficiencies in transparency and speed of response. Although some organisations implemented internal communication channels to mitigate the impact, external communication proved insufficient to counteract the deterioration of the corporate image (see Table 9). The lack of established protocols for crisis management complicated the restoration of customer and partner confidence.

Table 9.

Main organisational responses and their impact on communication and image.

Regarding transparency, 45% (90 companies) decided on public acknowledgment of the incident (TR.1), while 55% (110 companies) preferred to handle the situation internally, revealing few details to avoid further erosion of the corporate image. This duality of approaches is directly related to reputational risk management and the organisation’s culture in the face of cybersecurity crises [43]. These findings suggest that, in the Colombian context, the combination of technical weaknesses and inadequate crisis management exacerbates the reputational impact on both the organisation and its employees.

5. Discussion

This qualitative study provides novel insights into employees’ responses to corporate data breaches from a reputational management perspective. The findings reveal a multi-phase process, beginning with an initial period of shock and uncertainty, influenced by concerns over personal data and organisational integrity [42]. This study confirms the importance of this phase but adds that its duration is strongly mediated by the transparency of internal communication—a factor underexplored in the prior literature. In the subsequent evaluation phase, employees assess the severity of the breach and the organisation’s response, aligning with [44]’s crisis attribution model. However, unlike external stakeholders, employees incorporate insider knowledge, complicating attribution processes. Contrary to [45], who see employees as message transmitters, our findings show they can become either reputational ambassadors or internal critics, depending on how authentic they perceive the organisation’s response to be. This study further supports [46] by suggesting that employee empowerment, particularly when coupled with technical expertise, can play an important role in strengthening organisational reputational resilience after a data breach. Drawing on [3]’s image restoration theory, this research shows that employees actively engage in strategic image defence, shifting from denial to corrective action based on evolving perceptions. These findings also intersect with [47]’s trust reconstruction model, suggesting that employee strategies vary across recovery stages depending on their trust in leadership communication. Overall, this study underscores that employees are not passive agents but co-constructors of reputational narratives, with their responses shaped by organisational identification, perceived authenticity, and procedural justice. The interaction between social identity, procedural justice perceptions, and image restoration choices emerged clearly; employees who perceived the organisation’s crisis response as fair and authentic were more inclined to act as reputational ambassadors, applying constructive restoration strategies. In contrast, those perceiving low procedural justice often resorted to defensive or distancing strategies.

As supported by recent studies [48] employee social identity and perceived procedural justice play a key role in shaping the selection of image restoration strategies after data breaches. This enriches current theories by foregrounding the active negotiated nature of internal crisis communication in the wake of data breaches.

Our findings also suggest that employees’ social identity, particularly their level of identification with the organisation, strongly influences which image restoration strategies they adopt. Employees with strong organisational identification tend to engage in corrective action or reducing offensiveness, while those with weaker identification or critical stance are more likely to adopt denial or distancing strategies. While many technical frameworks (such as ISO 27001 or NIST CSF) address organisational security, relatively little attention has been paid to how employee agency shapes knowledge governance in the sensitive post-breach phase, an area this study seeks to advance.

Knowledge management (KM) plays a pivotal role in shaping employee responses and organisational resilience following data breach incidents. In organisations affected by cyberattacks involving data leaks, robust KM practices can mitigate uncertainty by facilitating transparent communication, knowledge sharing, and the dissemination of security protocols. These mechanisms not only support employees in regaining confidence but also influence how they perceive the organisation’s reputation post-incident. When knowledge flows effectively, employees are more likely to align with the company’s recovery narrative, potentially buffering reputational damage internally and externally. Furthermore, the perception of organisational competence in managing knowledge post-breach correlates with higher levels of employee trust and engagement. Therefore, the strategic deployment of KM systems post-cyberattack is not merely operational but reputational. Empirical studies underscore the mediating role of KM in employee attitudes and corporate image restoration following cybersecurity incidents [49]. As practical implications, organisations should actively integrate employee perspectives into post-breach information governance, for example by establishing structured channels for employee input and feedback on data protection practices. Additionally, companies should encourage cross-level dialogue on data security, allowing frontline employees and managers to co-create response protocols that reflect both organisational priorities and employee concerns.

The reputational impact on organisations following cyberattacks involving data breaches is both profound and multifaceted, often extending beyond external stakeholder perceptions to significantly affect internal employee dynamics. Empirical evidence suggests that such incidents can erode trust, diminish organisational commitment, and foster a climate of uncertainty among employees, particularly when communication is perceived as insufficient or reactive rather than strategic. From a reputational standpoint, data breaches frequently lead to public scrutiny, loss of consumer confidence, and potential financial repercussions, all of which are compounded when internal actors—employees—perceive mismanagement or lack of preparedness. Effective knowledge management and transparent crisis communication have been shown to play a critical role in mitigating these effects, helping to restore both employee morale and the organisation’s external image. Thus, the reputational and employee-related consequences of cyberattacks are closely interlinked, necessitating integrated response strategies that address both human and reputational dimensions [50]. By operationalising employee involvement, through participatory design of data policies, inclusive crisis communication strategies, and transparent post-incident reviews, organisations can foster greater trust, resilience, and authenticity in their cybersecurity governance.

6. Limitations and Future Research

Our findings suggest the need to refine existing theoretical models on post-crisis reputational management to incorporate the specific dynamics of cyberattacks. Unlike other organisational crises, data breaches simultaneously position employees as potential victims (due to the exposure of their personal data) and as organisational representatives, creating a unique tension in their reputational response. This duality is not adequately captured in traditional crisis management frameworks such as Coombs’ situational crisis communication theory (SCCT) [42].

Additionally, the results indicate that the reputational impact of cyberattacks evolves through distinct temporal phases, with different mediating factors predominating in each phase. This contrasts with more static models of reputational damage and suggests the need for a more dynamic approach that recognises the evolving nature of employee perceptions following data breaches. Despite our efforts to assess the authenticity of responses, we recognise this remains a challenge in sensitive cybersecurity contexts. Future research could explore this aspect further through complementary data sources and adopting longitudinal research designs.

The present study is based on data from Colombian organisations, where legal frameworks and cultural contexts differ from those in Europe or North America (e.g., GDPR regulations). As such, the applicability of these findings to other geographies should be approached with caution. However, the Colombian context, characterised by lower regulatory development and legal gaps regarding data breach management, may also illuminate dynamics present in other emerging markets with similar institutional conditions. Future research could explore how local regulatory environments shape employee-driven information governance.

This study did not aim to systematically assess formal compliance with cybersecurity standards such as ISO 27001, which may influence organisational responses to breaches. Future research could further explore how such frameworks shape employee perceptions and knowledge sovereignty dynamics. Future research should explore organisational identification, perception of authenticity in corporate response, and assessments of procedural justice in diverse organisational contexts, examining factors such as organisational culture, as the prior history of cyber incidents and internal power structures influence employees’ willingness and ability to participate effectively in restoring corporate image after data breaches.

Subsequent research could benefit from a more detailed analysis of threats to internal and external validity, including a systematic assessment of potential biases and inherent limitations of the qualitative methods employed in the study of information governance post-data breach.

7. Conclusions

Cyberattacks involving data breaches generate a unique dynamic where employees simultaneously experience the roles of potential victims (due to exposure of their personal data) and organisational representatives (due to their identity link with the company). This duality, not sufficiently identified in the previous research, creates specific tensions in the adoption of image restoration strategies that are not present in other types of organisational crises. Resolving this tension emerges as a critical factor in employees’ willingness to participate constructively in reputational restoration.

This research shows the value of combining image restoration, social identity, and procedural justice theories to better understand employee responses to data breaches. This integration provides a more robust analytical framework for understanding complex phenomena such as employee responses to data breaches, and suggests the need for more interdisciplinary approaches in the study of reputational management in cybersecurity contexts. The experiences observed in Colombia may inform cybersecurity governance practices in other emerging economies facing similar regulatory gaps and institutional challenges.

This study identifies a previously undocumented phenomenon: the formation of micro-narratives among employee groups that may diverge significantly from the official narrative but serve as mechanisms of cohesion and shared meaning during post-breach uncertainty. These micro-narratives function as spaces for negotiating meaning where individual perceptions are reconciled with organisational positionings, mediating the final adoption of restorative strategies. By focusing on the employee-driven dynamics of knowledge sovereignty, this study offers new insights into post-breach governance practices that complement existing technical and managerial frameworks, and provides actionable guidance for enhancing organisational resilience.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.M.L. and J.V.-O. methodology, J.M.L., J.V.-O. and K.R.B.; software, K.R.B.; validation, J.M.L., J.V.-O. and K.R.B.; formal analysis, J.M.L. and J.V.-O.; investigation, J.M.L., J.V.-O. and K.R.B.; resources, J.M.L., J.V.-O. and K.R.B.; data curation, J.M.L., J.V.-O. and K.R.B.; writing—original draft preparation, J.M.L. and J.V.-O.; writing—review and editing, J.M.L. and J.V.-O.; visualization, J.M.L., J.V.-O. and K.R.B.; supervision, J.M.L. and J.V.-O.; project administration, J.M.L.; funding acquisition, K.R.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Minciencias, grant number 82299 and the APC was funded by Juan Velez-Ocampo and Jeferson Martínez Lozano.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author(s).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Opening statement: “Thank you for taking the time to speak with us today. To begin, could you please provide us with an overview of the nature and scope of the data breach that your organisation has recently faced?”

Appendix A.1. Cybersecurity and Risk in the Business Environment

- What specific vulnerabilities or weaknesses in the security systems, processes, or controls allowed the data breach incident to occur?

- Are you aware of whether confidential or sensitive company information was accessed, stolen, or compromised during the attack?

- Were the implemented security tools and technologies, such as firewalls, antivirus software, monitoring systems, etc., effective in detecting and preventing the attack? If not, what deficiencies were identified?

- What measures have been taken or are being taken to mitigate the damages caused by the cyberattack?

- Were there any failures in compliance with existing security policies and procedures that contributed to the incident? If so, what were those failures?

Appendix A.2. Impact of Data Breaches on Corporate Reputation

- How do you believe the data breach has impacted the trust and perception of clients/users, collaborators, and employees toward our organisation? Please explain in detail.

- In your opinion, which external stakeholders (suppliers, business partners, regulatory authorities, etc.) have been most affected by this incident and why?

- How has the morale, trust, and reputation of the workforce been affected following the incident?

- Have you observed any changes in the perception of clients or business partners toward the company since the data breach? How do you believe the company’s reputation has been affected in the short and long term?

- What recommendations would you suggest to prevent future data breaches and mitigate their impact?

Appendix A.3. Communication Strategies in Crisis Resulting from a Data Breach

- How do you think we could effectively communicate our efforts to address and resolve the situation in order to rebuild trust and credibility in our organisation?

- What comments or reactions have you observed on social media, in the media, or among your contacts regarding our organisation’s reputation following the cyberattack?

- How would you rate the communication strategies and actions taken by the company following the data breach? Do you consider that the company has been transparent and proactive in managing the crisis?

- What suggestions do you have for evaluating the effectiveness of crisis response plans after the incident has passed?

- What are the ethical and legal considerations that companies take into account when deciding whether or not to negotiate with cybercriminals following a data breach?

Closing statement: “Before we conclude, is there any aspect of managing this data breach that you would like to explore further?”

Appendix B

Appendix C

References

- Cram, W.A.; Proudfoot, J.G.; D’Arcy, J. When enough is enough: Investigating the antecedents and consequences of information security fatigue. Inf. Syst. Res. 2021, 32, 410–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, A.; Maynard, S.B. Employee responses to cybersecurity policy communication: A longitudinal analysis of sovereignty-asserting behaviours. Comput. Secur. 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Benoit, W.L. Accounts, Excuses, and Apologies: A Theory of Image Restoration Strategies; University of New York Press: New York, NY, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Karlsson, F.; Hedström, K.; Goldkuhl, G. Knowledge governance vacuums: Information security breaches and shifts in organisational knowledge networks. J. Strateg. Inf. Syst. 2020, 29. [Google Scholar]

- Coombs, W.T.; Holladay, S.J. The Handbook of Crisis Communication; Wiley-Blackwell: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- ISO/IEC 27001:2022; Information Security, Cybersecurity and Privacy Protection—Information Security Management Systems—Requirements. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022.

- Taddeo, M. Is Cybersecurity a Public Good? Minds Mach. 2019, 29, 349–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flyverbom, M.; Deibert, R.; Matten, D. The Governance of Digital Technology, Big Data, and the Internet: New Roles and Responsibilities for Business. Bus. Soc. 2019, 58, 3–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safa, N.S.; Maple, C.; Watson, T. Exploring the tension between employee victimhood and organisational representation following data breaches. Comput. Secur. 2023, 31, 315–329. [Google Scholar]

- Lowry, P.B.; Posey, C.; Bennett, R.J.; Roberts, T.L. Leveraging fairness and reactance theories to deter reactive computer abuse following enhanced organisational information security policies. Inf. Syst. J. 2021, 31, 309–340. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.; Sabherwal, R. Knowledge resilience during cybersecurity incidents: Linking employee agency to organisational recovery. J. Knowl. Manag. 2022, 26, 236–258. [Google Scholar]

- Renaud, K.; Flowerday, S. Post-breach agency restoration: Four strategies for psychological self-protection following data breaches. Inf. Comput. Secur. 2021, 29, 602–621. [Google Scholar]

- Nonaka, I.; Takeuchi, H. The Knowledge-Creating Company: How Japanese Companies Create the Dynamics of Innovation; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Belsis, P.; Kokolakis, S. Information security knowledge sharing after data breaches: A comparative analysis of explicit and tacit knowledge disruption. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2022, 62, 417–431. [Google Scholar]

- Stafford, T.F.; Posey, C. Information governance maturity in the post-breach era: An empirical examination of knowledge disruption and recovery. MIS Q. 2020, 44, 203–228. [Google Scholar]

- Fombrun, C.J.; Van Riel, C.B.M. Fame Fortune: How Successful Companies Build Winning Reputations; Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Barnett, M.L.; Jermier, J.M.; Lafferty, B.A. Corporate reputation: The definitional landscape. Corp. Reput. Rev. 2006, 9, 26–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Security Agency. StopRansomware Guide Released by NSA and Partners. Available online: https://media.defense.gov/2023/May/23/2003227891/-1/-1/0/CSI-StopRansomware-Guide.PDF (accessed on 30 January 2024).

- Kruse, C.S.; Frederick, B.; Jacobson, T.; Monticone, D.K. Cybersecurity in healthcare: A systematic review of modern threats and trends. Technol. Health Care 2017, 25, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.J.; Yoo, P.D.; Asyhari, A.T.; Jhi, Y.; Chermak, L.; Yeun, C.Y.; Taha, K. IMPACT: Impersonation attack detection via edge computing using deep autoencoder and feature abstraction. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 65520–65529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loukas, G.; Gan, D.; Vuong, T. A review of cyber threats and defence approaches in emergency management. Future Internet 2013, 5, 205–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulven, J.B.; Wangen, G. A systematic review of cybersecurity risks in higher education. Future Internet 2021, 13, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cybersecurity Glossary. Homeland Security. 2021. Available online: https://niccs.cisa.gov/cybersecurity-career-resources/vocabulary (accessed on 30 January 2024).

- NIST. 2021. Available online: https://www.nist.gov/itl/smallbusinesscyber/cybersecurity-basics/glossary (accessed on 30 January 2024).

- Shaikh, F.A.; Siponen, M. Information security risk assessments following cybersecurity breaches: The mediating role of top management attention to cybersecurity. Comput. Secur. 2023, 124, 102974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitman, M.E.; Mattord, H.J. Principles of Incident Response and Disaster Recovery; Cengage Learning: Boston, MA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Santos. Desarrollar programas y políticas de ciberseguridad. Publicación De TI De Pearson 2018, 3, 127. [Google Scholar]

- Shedden, P.; Smith, W.; Ahmad, A. Information Security Risk Assessment: Towards a Business Practice Perspective; Edith Cowan University: Perth, Australia, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Wangen, G. Information Security Risk Assessment: A Method Comparison. Computer 2017, 50, 52–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, F.; Kim, J.H.; Mathiassen, L.; Moore, R. DATA BREACH MANAGEMENT: AN INTEGRATED RISK MODEL. Inf. Manag. 2021, 58, 103392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerullo, V. Business continuity planning: A comprehensive approach. Inf. Syst. Manag. 2004, 21, 70–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ou, C.X.; Zhang, X.; Angelopoulos, S.; Davison, R.M.; Janse, N. Security breaches and organization response strategy: Exploring consumers’ threat and coping appraisals. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2022, 65, 102498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenhardt, K.M. Building theories from case study research. Acad Manage Rev. 1989, 14, 532–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguinis, H.; Solarino, A.M. Transparency and replicability in qualitative research: The case of interviews with elite informants. Strateg. Manag. J. 2019, 40, 1291–1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welch, C.; Piekkari, R.; Plakoyiannaki, E.; Paavilainen-Mäntymäki, E. Theorising from case studies: Towards a pluralist future for international business research. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2010, 42, 740–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plakoyiannaki, E.; Wei, T.; Prashantham, S. Rethinking Qualitative Scholarship in Emerging Markets: Researching, Theorizing, and Reporting. Manag. Organ. Rev. 2019, 15, 217–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meredith, J. Desarrollar la teoría de la gestión de operaciones a través de la investigación de casos y de campo. Rev. De Gestión De Oper. 1998, 16, 441–454. [Google Scholar]

- Suri, H. Purposeful Sampling in Qualitative Research Synthesis. Qual. Res. J. 2011, 11, 63–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandeira-de-Mello, R.; Fleury, M.T.L.; Aveline, C.E.S.; Gama, M.A.B. Unpacking the ambidexterity implementation process in the internationalization of emerging market multinationals. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 2005–2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miles, M.B.; Huberman, A.M.; Saldaña, J. Qualitative Data Analysis: A Methods Sourcebook; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Gwebu, K.L.; Wang, J.; Wang, L. The Role of Corporate Reputation and Crisis Response Strategies in Data Breach Management. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2018, 35, 683–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coombs, W.T. Protecting Organization Reputations During a Crisis: The Development and Application of Situational Crisis Communication Theory. Corp. Reput. Rev. 2007, 10, 163–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Dennis, A.R. The influence of negative online word-of-mouth on fear: A cognitive appraisal model. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 103, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Weiner, B. Social Motivation, Justice, and the Moral Emotions; Psychology Press: London, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novak, A.N.; Richmond, J.C. E-Racing together: How starbucks reshaped and deflected racial conversations on social media. Public Relat. Rev. 2019, 45, 101773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greve, H.R.; Seidel, M.L. The thin red line between success and failure: Path dependence in the diffusion of innovative production technologies. Strateg. Manag. J. 2015, 36, 475–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillespie, N.; Dietz, G. Trust Repair After An Organization-Level Failure. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2009, 34, 127–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Liao, J.; Xia, D.; Chang, T. The impact of organizational justice on work performance: Mediating effects of organizational commitment and leader-member exchange. Int. J. Manpow. 2010, 31, 660–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchanan, D.A.; Denyer, D. Researching tomorrow’s crisis: Methodological innovations and wider implications. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2013, 15, 205–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, P.; del Bosque, I.R. Sustainability Dimensions: A Source to Enhance Corporate Reputation. Corp. Reput. Rev. 2014, 17, 239–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).