How to Influence Privacy Behavior Using Cognitive Theory and Respective Determinant Factors

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review Methodology

2.1. Sampling Methodology

2.2. Exclusion Criteria

3. Theoretical Background in Experiential Learning in Other Fields

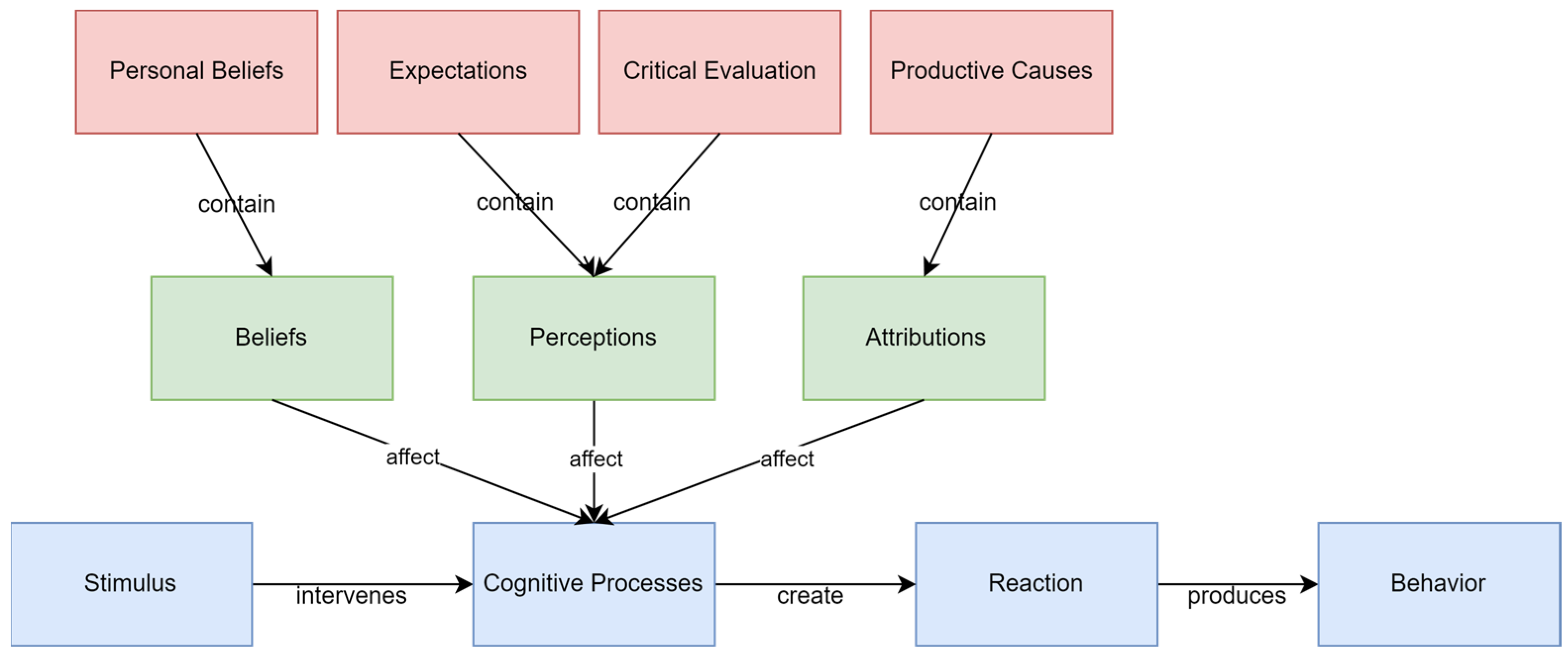

3.1. The Concept of Behavior in Psychology

- The neuropsychological theory;

- The psychoanalytical theory;

- The behavioral theory;

- The cognitive theory.

3.2. The Concept of Behavior in the Health Field

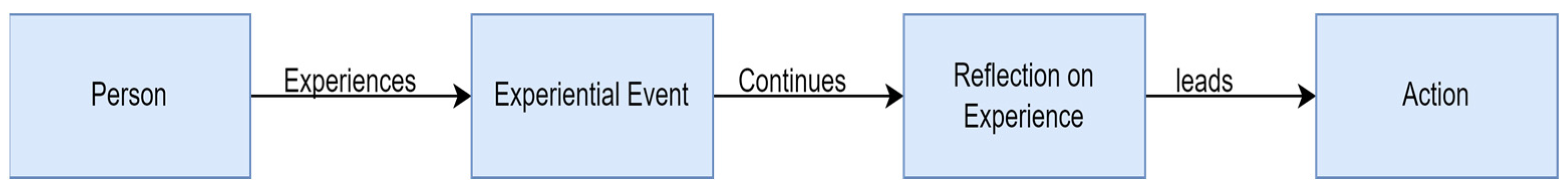

3.3. Behavior and Experiential Learning

- -

- The participants must have the will to learn through the experience they lived;

- -

- The participants should be able to reproduce the experience;

- -

- The participants must have analytical thinking and understand the experience;

- -

- The participants have the ability to make decisions and solve problems to create new ideas through the experiences they lived.

- -

- The participant reviews the events and has the ability to study the experience again, calling this review a return to the experience;

- -

- The participant recognizes the importance of the experience to third parties, through emotions;

- -

- The participant discovers the new dimensions of the experience so that through it, the change in his behavior occurs and creates a new way of thinking and new abilities.

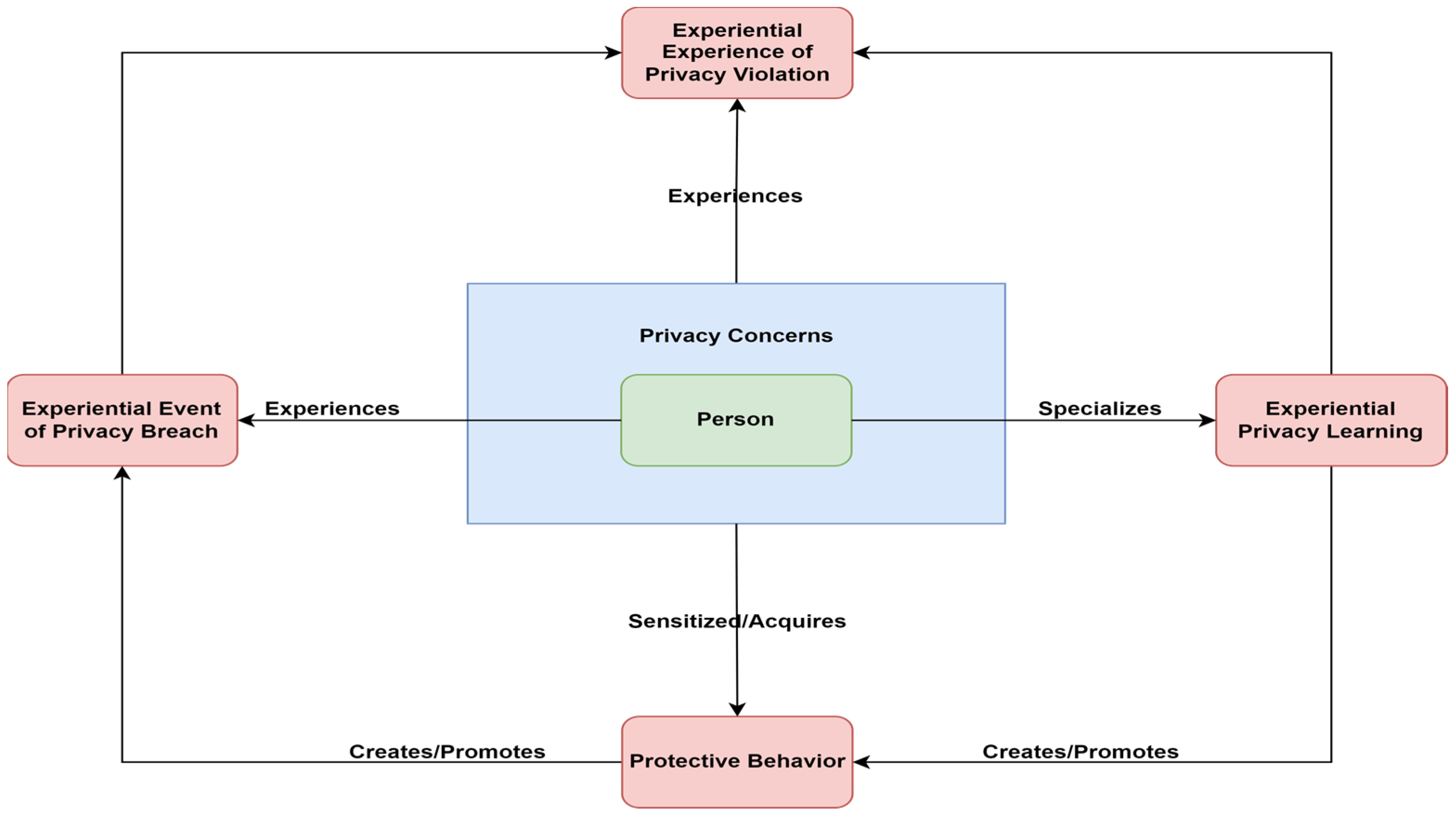

4. Adaptation of Theoretical Background for the Domain of Privacy Behavior

Practical Case Studies in the Privacy Behavior Field

5. Cognitive Theory and Privacy Behavior Factors

5.1. Conceptualizing Cognitive Theory and Privacy Behavior Factors

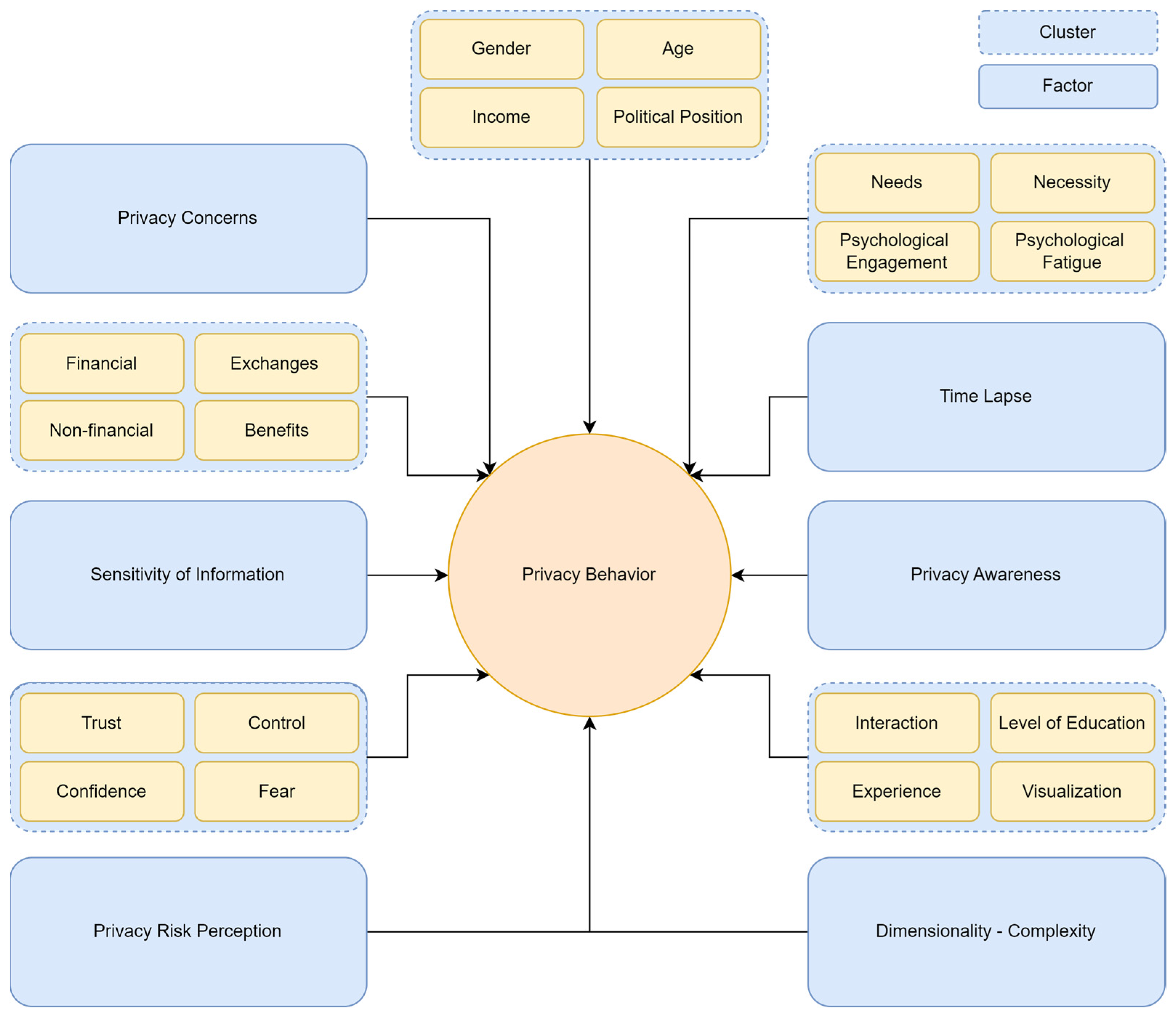

5.1.1. Privacy Behavior Factors

- The propensity score matching method was first proposed by Rosenbaum and Rubin [61] as a means of reducing selection bias in observational studies;

- Covariate matching, also known as balance matching, aims to balance the distribution of covariates between the treated and control groups in observational studies to reduce confounding bias;

- The nearest neighbor matching method is particularly useful when the number of variables is small. The method can be used in a variety of fields, including epidemiology, economics, and psychology, to estimate the similarities of the observed variables, close relationships of the observed variables, or the outcome of a statistical or medical experiment.

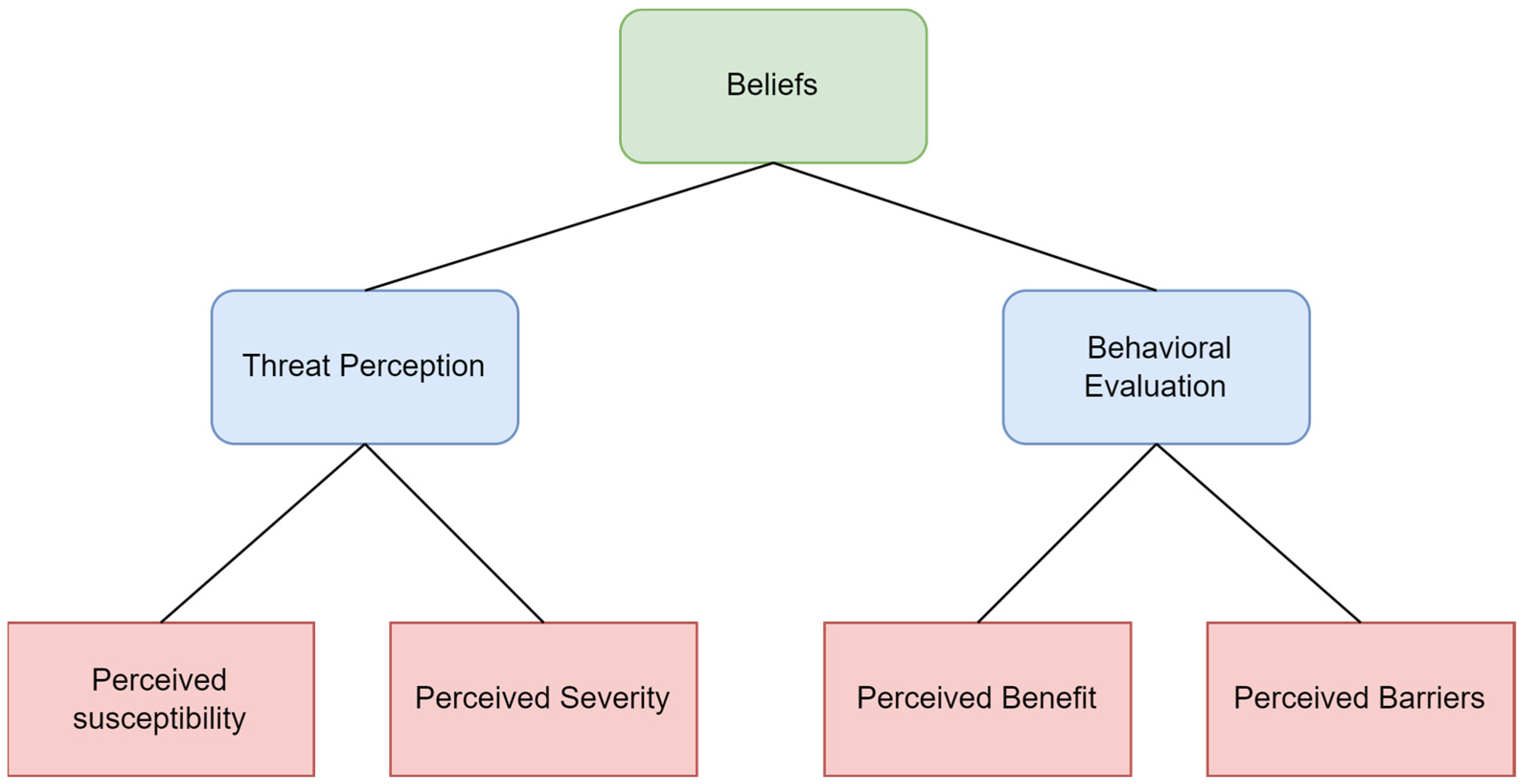

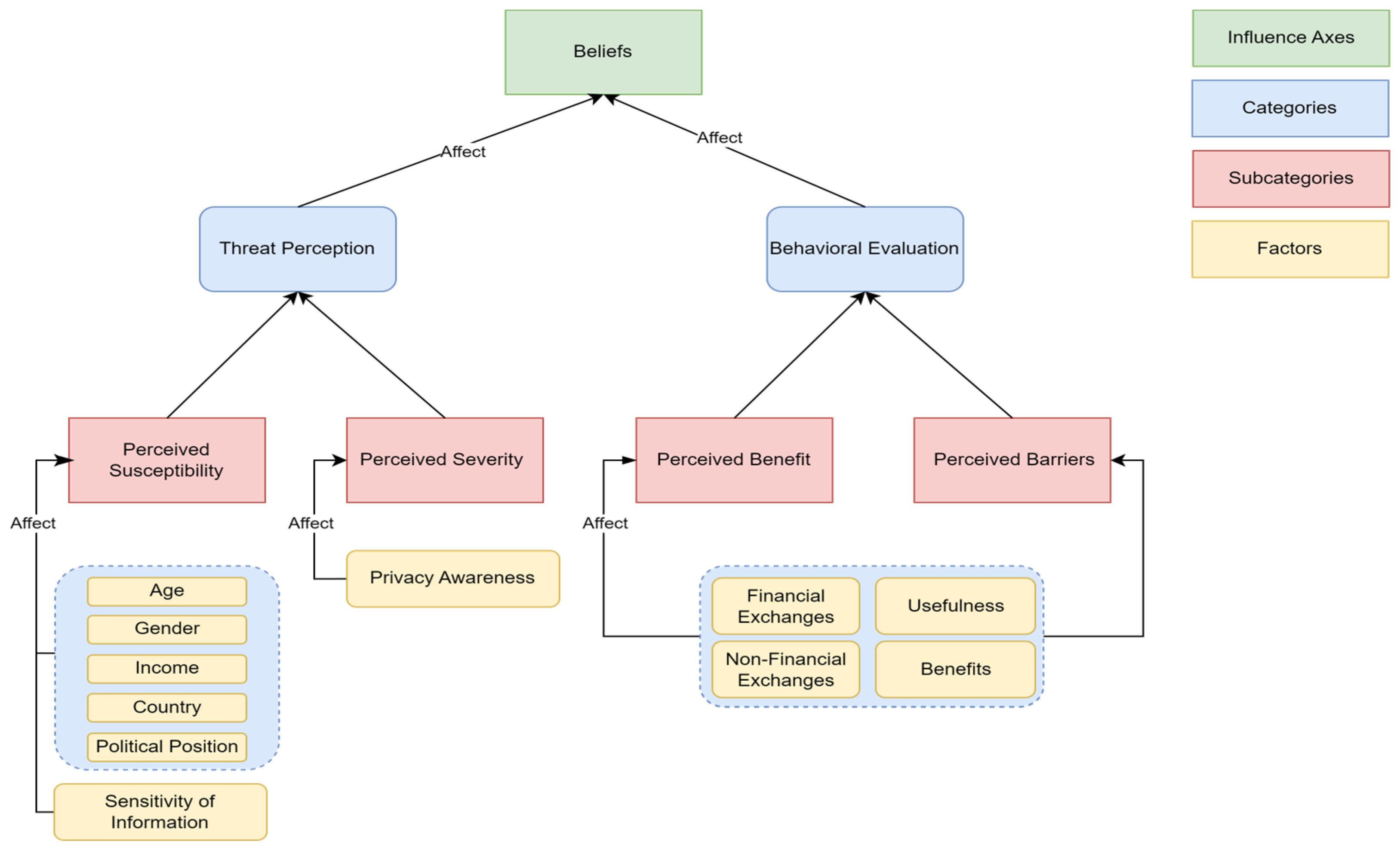

5.1.2. Beliefs

5.1.3. Perceptions

5.1.4. Attributions

6. Discussion

6.1. General Discussion

6.2. Implications

7. Conclusions and Future Work

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Menard, P.; Bott, G. Analyzing IOT users’ mobile device privacy concerns: Extracting privacy permissions using a disclosure experiment. Comput. Secur. 2020, 95, 101856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shane-Simpson, C.; Manago, A.; Gaggi, N.; Gillespie-Lynch, K. Why do college students prefer Facebook, Twitter, or Instagram? Site affordances, tensions between privacy and self-expression, and implications for social capital. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2018, 86, 276–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dhir, A.; Kaur, P.; Lonka, K.; Nieminen, M. Why do adolescents untag photos on Facebook? Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 55, 1106–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinds, J.; Williams, E.; Joinson, A. It wouldn’t happen to me: Privacy concerns and perspectives following the Cambridge Analytica scandal. Int. J. Hum. Comput. Stud. 2020, 143, 102498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathews-Hunt, K. CookieConsumer: Tracking online behavioural advertising in Australia. Comput. Law Secur. Rev. 2016, 32, 55–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palos-Sanchez, P.; Saura, J.R.; Martin-Velicia, F. A study of the effects of programmatic advertising on users’ concerns about privacy overtime. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 96, 61–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokolakis, S. Privacy attitudes and privacy behaviour: A review of current research on the privacy paradox phenomenon. Comput. Secur. 2017, 64, 122–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallam, C.; Zanella, G. Online self-disclosure: The privacy paradox explained as a temporally discounted balance between concerns and rewards. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017, 68, 217–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Luo, X.; Zhang, J.; Xu, H. Resolving the privacy paradox: Toward a cognitive appraisal and emotion approach to online privacy behaviors. Inf. Manag. 2017, 54, 1012–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerber, N.; Gerber, P.; Volkamer, M. Explaining the privacy paradox: A systematic review of literature investigating privacy attitude and behavior. Comput. Secur. 2018, 77, 226–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paspatis, I.; Tsohou, A.; Kokolakis, S. How is Privacy Behavior Formulated? A Review of Current Research and Synthesis of Information Privacy Behavioral Factors. Multimodal Technol. Inf. MTI 2023. submitted. [Google Scholar]

- Angst, C.M.; Agarwal, R. Adoption of electronic health records in the presence of privacy concerns: The elaboration likelihood model and individual persuasion. MIS Q. 2009, 33, 339–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Acquisti, A.; Grossklags, J. Privacy and rationality in individual decision making. IEEE Secur. Priv. 2005, 3, 26–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, J.Y.; Kelley, P.G. Who’s viewed you? The impact of feedback in a mobile location-sharing application. In Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Boston, MA, USA, 4–9 April 2009; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 2005–2008. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, D.G. Human-Computer Interaction: Psychology as A Science of Design. In The Human-Computer Interaction Handbook: Fundamentals, Evolving Technologies, and Emerging Applications, 3rd ed.; Jacko, J., Ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2013; pp. 3–18. [Google Scholar]

- Conner, M.; Norman, P. Pros and Cons of Social Cognition Models in Health Behaviour, in Health Psychology. Update Volume 14, pages 24–31, 1993. Available online: https://fhs.thums.ac.ir/sites/fhs/files/user31/P_R_E_D_I_C_T_I_N_G.pdf (accessed on 30 May 2023).

- Conner, M.; Norman, P. Predicting Health Behaviour. Research and Practice with Social Cognition Models; Open University Press: Buckingham, UK, 1996; pp. 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Jarvis, P. Adult Education & Lifelong Learning; RoutledgeFalmer: London, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Dewey, J. Experience and Education; Macmillan: New York, NY, USA, 1938. [Google Scholar]

- Freire, P. Teachers as Cultural Workers—Letters to Those Who Dare to Teach; Westview Press: Boulder, CO, USA, 1998; p. 100. ISBN 978-0-8133-4329-7. [Google Scholar]

- Kolb, D.A. Experiential Learning: Experience as the Source of Learning and Developmen; Pearson Education LTD: London, UK, 1984; ISBN 0-13-389240-9. [Google Scholar]

- Rogers, A. Adult Education; Metaichmio Publications: Athens, Greece, 1999; Volume 1, ISBN 978-960-566-840-2. [Google Scholar]

- Kokko, A. Adult Education Methodology: Theoretical Framework and Learning Conditions; Patras EAP: Patras, Greece, 2005; Volume A. [Google Scholar]

- Mezirow, J. Transformative Dimensions of Adult Learning; Jossey-Bass: San Fransisco, CA, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Mezirow, J. Transformative learning and social action: A response to Inglis. Adult Educ. Q. 1998, 49, 70–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mezirow, J. On critical reflection. Adult Educ. Q. 1998, 48, 185–198, American association for adult and continuing education: Sage publications. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mezirow, J. Transformative Learning; Metaichmio Publications: Athens, Greece, 2006; Volume 1, ISBN 978-960-455-226-9. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, W.E. The Theory and Practice of Transformative Learning: A Critical Review. ERIC Clearinghouse on Adult, Career, and Vocational Education; The Ohio State University: Columbus, OH, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Dacou, E. Educational Biography Influences and Determines the Career Path of Adults. The Case of Educational Institutions. Hellenic Open University. 2018. Available online: https://apothesis.eap.gr/handle/repo/39397 (accessed on 29 January 2020).

- Gluck, M.A.; Mercado, E.; Myers, C.E. Learning and Memory: From Brain to Behavior; Worth Publishers: New York, NY, USA, 2016; p. 57. ISBN 978-1-319-15405-9. [Google Scholar]

- Posner, M.I.; DiGirolamo, G.J. Cognitive neuroscience: Origins and promise. Psycho-Log. Bull. 2000, 126, 873–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Overskeid, G. Looking for Skinner and finding Freud. Am. Psychol. 2007, 62, 590–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gardner, L. Behaviorism and dynamic psychology: Skinner and Freud. Psychoana-Lytic Rev. 1979, 66, 253–262. [Google Scholar]

- Pavlov, I.P. Conditioned Reflexes: An Investigation of the Physiological Activity of the Cerebral Cortex; Translated and edited by Anrep, G.V.; Oxford University Press: London, UK, 1927. [Google Scholar]

- Weinman, J. Health Psychology: Progress, Perspectives, and Prospects, Current Developments in Health Psychology; Hardwood Academic Publishers: London, UK, 1990; pp. 9–33. [Google Scholar]

- Koulierakis, G.; Metallinou, P.; Pantzou, P. Sociological and Psychological Approach to Hospitals and Health Services; Hellenic Open University Publications: Pátra, Greece, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Abramson, L.Y.; Seligman, M.E.; Teasdale, J.D. Learned helplessness in humans: Critique and reformulation. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 1978, 87, 49–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherry, K. What Is Cognitive Psychology? The Science of How We Think. 2022. Available online: https://www.verywellmind.com/cognitive-psychology-4157181 (accessed on 28 May 2023).

- Ghosh, I.; Singh, V. Using cognitive dissonance theory to understand privacy behavior. In Proceedings of the Association for Information Science and Technology, Washington, DC, USA, 27 October–1 November 2017; Volume 54, pp. 679–681. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, A. Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioural change. Psychol. Rev. 1977, 84, 191–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, A.T. Cognitive Therapy and the Emotional Disorders; International Universities Press: New York, NY, USA, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Rotter, J.B. Generalized expectancies for internal and external control of reinforcement. Psychol. Monogr. Gen. Appl. 1966, 80, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Stroebe, W. Social Psychology and Health; Open University Press: Buckingham, UK, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Abraham, C.; Sheeran, P. The Health Belief Model in Conner and Norman, Predicting Health Behaviour. Research and Practice with Social Cognition Models; Open University Press: Buckingham, UK, 1995; pp. 23–61. [Google Scholar]

- Lewin, K. Field Theory in Social Science; Harper: New York, NY, USA, 1951. [Google Scholar]

- Krstic. Journal of the Psychological Institute of the University of Zagreb; University of Zagreb: Zagreb, Croatia, 1964; pp. 7–13. [Google Scholar]

- Hochbaum, G.M. Public Participation in Medical Screening Programs: A Socio-Psychological Study, Public Health Service; United States Government Printing Office: Washington, DC, USA, 1958.

- Rosenstock, I.M. Historical origins of the health belief model. Health Educ. Monogr. 1974, 2, 328–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, M.H.; Maiman, L.A.; Kirscht, J.P.; Haefner, D.P.; Drachman, R.H. The health belief model in the prediction of dietary compliance: A field experiment. J. Health Soc. Behav. 1977, 18, 348–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anagnostopoulos, F.; Papadatou, D. Psychology in the Field of Health; Ellinika Grammata Publications: Athens, Greece, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Jensen, C.; Potts, C.; Jensen, C.D. Privacy practices of Internet users: Self-report versus observed behavior. Int. J. Hum.-Comput. Stud. 2017, 98, 82–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, R.; Brown, L. The Nicomachean Ethics. Oxford; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Boud, D.; Keohg, R.; Walker, D. Reflection: Turning Experience into Learning; Kogan Press: New York, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Mavrogiorgos. Teacher Training: Other–Rivalry. Nicosia. Available online: https://www.pi.ac.cy/pi/files/keea/synedria/synedrio_pi_pdf_tel/7_Mavrogiorgos.pdf (accessed on 28 May 2023).

- Freud, S. Massenpsychologie und Inch Analyse; Internationaler Psychoanalytischer Verlag G. M. B. H.: Wien, Austria, 1921. [Google Scholar]

- Koester, N.; Cichy, P.; Antons, D.; Salge, T.O. Perceived privacy risk in the Internet of Things: Determinants, consequences, and contingencies in the case of connected cars. Electron. Mark. 2022, 32, 2333–2355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West, R.; Michie, S. Embedding Covid-Safe Behaviours into Everyday Life through an Enhanced Risk Management Approach. Available online: https://www.qeios.com/read/SPL9QE (accessed on 28 May 2023).

- Smith, J.; Johnson, A.; Davis, R. Privacy Lab: A Case Study of Experiential Learning in Privacy Education. J. Priv. Educ. 2018, 12, 145–162. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, M.; Anderson, L. Enhancing Privacy Education in Healthcare: A Case Study of Experiential Learning Approaches. Health Inform. J. 2019, 25, 1766–1782. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, E.; Green, H. Engaging Students in Privacy Education: A Case Study of Experiential Learning in K-12 Settings. J. Digit. Citizsh. 2020, 4, 78–94. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenbaum, P.R.; Rubin, D.B. Reducing bias in observational studies using subclassifi-cation on the propensity score. J. Am. Stat. Association. 1984, 79, 516–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubin, D.B. Estimating causal effects of treatments in randomized and nonrandomized studies. J. Educ. Psychol. 1974, 66, 688–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rubin, D.B. Estimating causal effects from large data sets using propensity scores. Ann. Intern. Med. 1997, 127, 757–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holmes, C.C.; Adams, N.M. Likelihood Inference in Nearest-Neighbour Classification Models. Biometrika 2003, 90, 99–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Reynolds, B.; Venkatanathan, J.; Goncalves, J.; Kostakos, V. Sharing Ephemeral Information in Online Social Networks: Privacy Perceptions and Behaviours. In Human-Computer Interaction–INTERACT 2011: 13th IFIP TC 13 International Conference, Lisbon, Portugal, 5–9 September 2011, Proceedings, Part III 13; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2011; pp. 204–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cherry, K. What Is Perception? Recognizing Environmental Stimuli through the Five Senses. 2023. Available online: https://www.verywellmind.com/perception-and-the-perceptual-process-2795839 (accessed on 30 May 2023).

- Cherry, K. What Is Attribution in Social Psychology? 2022. Available online: https://www.verywellmind.com/attribution-social-psychology-2795898 (accessed on 28 May 2023).

| Term | Definition |

|---|---|

| Experiential Event | An experiential event is any event experienced by a subject. |

| Experiential Learning | Experiential learning is defined as the process in which one learns or becomes specialized in a task by doing it. By extension, experiential experience is defined as the result of experiential learning, such as knowledge and feelings. |

| Event of Privacy Breach | Any data processing that takes place using a service or technology provider (or more) and is contrary to the perception of the data subject when consenting and using this service or technology (we do not mean the violation of the terms of use by the provider). Therefore, the same event can be classified as a violation of privacy, or not, depending on the person and their perception of privacy. |

| Experiential Event of Privacy Breach | Any event of privacy breach in which the subject became aware of that breach. An example of such a breach is when a data subject discloses his location on a social network by posting a photograph and, after appropriate third-party processing of that photograph, the temporal and spatial location of the subject is found, while the data subject was not aware that this is possible. |

| Experiential Privacy Learning | The process by which the subject analyzes the experiential event and learns from it. |

| Experiential Experience of Privacy Violation | The outcome for the subject of learning (knowledge, skills, and feelings) about privacy. |

| Privacy Concerns | The user’s willingness to share data and how these relation-ships in turn are affected by inter-individual differences in an individual’s regulatory focus, thinking style, and institutional trust [56]. |

| Protective Behavior | A protective behavior enacted by a person to protect them-selves or others from a threat to their health or safety [57]. |

| Factor | Description |

|---|---|

| Financial/Non-Financial Exchanges/Benefits/Usefulness | A financial exchange is defined as an action that has an economic benefit as a result. As a non-financial exchange, benefit or usefulness is defined as an action that has a non-economic benefit. |

| Privacy Risk Perception | Privacy risk perception refers to a person’s non-subjective evaluation of the likelihood of a potential privacy incident or event. |

| Trust/Control/Confidence/Fear | Trust refers to the belief in the reliability or credibility of a person, group, or party. Control refers to the ability of a person to manage situations or personal data. Confidence refers to the belief in a person of their abilities and skills. Fear refers to an emotional response to perceived danger, threat, or uncertainty. |

| Privacy Concerns | The user’s willingness to share data and how these relationships in turn are affected by inter-individual differences in an individual’s regulatory focus, thinking style, and institutional trust. |

| “Needs”/Psychological Engagement/Necessity | Psychological engagement refers to a person’s experiences when engaging in an activity or process. |

| Sensitivity of Information | Sensitivity of information of a person refers to the degree of importance, confidentiality, or information that the person requires not to be public. |

| Privacy Awareness | Privacy Awareness refers to a person’s understanding and recognition of the value and importance of the protection of personal information from disclosure. |

| Time-lapse | Time-lapse refers to the time between two or more events. |

| Education/Visualization/Interaction/Experience | Education refers to the process of acquiring knowledge and skills through an educational procedure such as school. Visualization refers to the creation of images or videos in order to represent data or information. Interaction refers to the exchange of information or sputum response between two or more persons. Experience refers to the accumulation of knowledge and skills through events, incidents, and activities. |

| Demographics (age/gender/country, political position, income, etc.) | Demographics refer to the statistical data and characteristics of a population or a group of people |

| Dimensionality/Complexity of Privacy Decision-making | Dimensionality refers to the number of variables that pull apart a phenomenon. |

| How Privacy Behavior Factors Influence Beliefs and Thus Cognitive Processes | ||

|---|---|---|

| Privacy Behavior Factor | Belief Element That Is Influenced | Fulfilled Criterion |

| Both Financial/Non-financial Exchanges and Benefits and Usefulness | Behavioral Evaluation: Perceived Benefits Behavioral Evaluation: Perceived Barriers | Criteria 1 and 2 |

| Demographics | Threat Perception: Perceived Susceptibility | Criterion 2 |

| Sensitivity of Information | Threat Perception: Perceived Susceptibility | Criterion 1 |

| Privacy Awareness | Threat Perception: Perceived Severity | Criterion 2 |

| How Privacy Behavior Factors Influence Perceptions and Thus Cognitive Processes | ||

|---|---|---|

| Privacy Behavior Factor | Element That Is Influenced | Fulfilled Criterion |

| Privacy Concerns | Perception | Criterion 2 |

| Privacy Risk Perceptions | Perception | Criteria 1 and 2 |

| How Privacy Behavior Factors Influence Attributes (Productive Causes) and Thus Cognitive Processes | ||

|---|---|---|

| Privacy Behavior Factor | Element That Is Influenced | Fulfilled Criterion |

| Cluster: “needs, psychological engagement, and necessity” | Attribution | Criteria 1 and 2 |

| Privacy Awareness | Attribution | Criteria 1 and 2 |

| Cluster: Interaction/Experience/Visualization | Attribution | Criterion 2 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Paspatis, I.; Tsohou, A. How to Influence Privacy Behavior Using Cognitive Theory and Respective Determinant Factors. J. Cybersecur. Priv. 2023, 3, 396-415. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcp3030020

Paspatis I, Tsohou A. How to Influence Privacy Behavior Using Cognitive Theory and Respective Determinant Factors. Journal of Cybersecurity and Privacy. 2023; 3(3):396-415. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcp3030020

Chicago/Turabian StylePaspatis, Ioannis, and Aggeliki Tsohou. 2023. "How to Influence Privacy Behavior Using Cognitive Theory and Respective Determinant Factors" Journal of Cybersecurity and Privacy 3, no. 3: 396-415. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcp3030020

APA StylePaspatis, I., & Tsohou, A. (2023). How to Influence Privacy Behavior Using Cognitive Theory and Respective Determinant Factors. Journal of Cybersecurity and Privacy, 3(3), 396-415. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcp3030020