Abstract

An effective network security requirement engineering is needed to help organizations in capturing cost-effective security solutions that protect networks against malicious attacks while meeting the business requirements. The diversity of currently available security requirement engineering methodologies leads security requirements engineers to an open question: How to choose one? We present a global evaluation methodology that we applied during the IREHDO2 project to find a requirement engineering method that could improve network security. Our evaluation methodology includes a process to determine pertinent evaluation criteria and a process to evaluate the requirement engineering methodologies. Our main contribution is to involve stakeholders (i.e., security requirements engineers) in the evaluation process by following a requirement engineering approach. We describe our experiments conducted during the project with security experts and the feedback we obtained. Although we applied it to evaluate three requirements engineering methods (KAOS, STS and SEPP) in the context of network security, our evaluation methodology can be instantiated in other contexts and other methods.

1. Introduction

Over the past years, the growing dependency of the business-critical applications and processes on network technologies and services has expanded the threat landscape to a large extent. Today networks constitute the main vector for attacks [1]. Thus, considering network security is crucial for ensuring business continuity in light of the growing threats.

Network security mainly concerns the security architectural needs that describe network segmentation (a.k.a., security zoning); security constraints of network devices connecting the communicating end user systems; and security constraints of the data being transferred across the communication links [2]. The ultimate aim boils down to preventing illegitimate access to the data assets that carry vital information and influence the decisions relating business critical operations [3]. An appropriate design of the network architecture provides many advantages (e.g., isolation of low trust systems, limitation of a security breach’s scope, costs savings) [4].

Currently, there exists numerous network security controls (e.g., firewalls, intrusion detection and prevention systems, VPNs, etc.) to implement network security [5,6,7,8]. Each time a security control (e.g., firewall or a proxy) is added or removed to the network, it will impact the applications running over the network, the quality of service of the network and also the cost of the network with new purchase and installation [9]. For instance, adding a DMZ (de-militarized zone) into an existing network provides a perimeter defense by isolating the internal network devices that are accessible from the public network. Nevertheless, the DMZ significantly alters the network architecture. In this regard, considering network security too late in the network development cycle (i.e., post deployment of network designs) would render additional costs and complexity in terms of incorporating any changes to the existing infrastructures. The difference in the return of security investments considered at early or at late stages of the system development cycle can range from 12 to 21 percent [10]. Therefore, it is necessary to examine network security at earlier stages, i.e., right from the planning stages of networks architecting. This perspective is known as security-by-design, which enforces the consideration of security right from the requirements analysis.

Therefore, network security requirements play a critical role since they impact the decisions related to the implementation of security controls [2]. Indeed, bad network security requirements can lead to ineffective and costly security or worth security holes in the network security design. An effective network security requirement engineering is needed to help organizations in capturing cost-effective security solutions that protect their networks against malicious attacks while meeting the business requirements.

Requirements Engineering (RE), in general, is a sub-discipline of system/software engineering, which subsumes the activities of gathering (a.k.a. eliciting), evaluating and documenting system/software requirements. Security requirements engineering (SRE) methods extend RE to the security context, by enabling the integration of risk analysis concepts. They help organizations in capturing security requirements by analyzing the business risk impact of potential threats. However, the diversity of SRE methodologies leads security requirements engineers to an open question: How to choose one? Utilization of various procedures and tools, choosing unsuitable RE instruments or utilization of inadequate techniques for eliciting requirements are among the most frequently reported issues [11]. Several comparative studies on SRE methodologies are available. Nonetheless, their evaluation is often based on a set of ad hoc criteria, hence these comparison criteria may not fit the SRE needs of every company. Thus, a systematic method must be proposed to properly capture the actual company’s needs regarding an SRE methodology.

In this article, we address this issue by proposing a requirements engineering-based evaluation methodology. It helps in characterizing the appropriateness of a SRE methodology by capturing the SRE needs of the stakeholders as well as the quality characteristics of good security requirements (a.k.a. quality criteria). We developed this evaluation methodology during the IREHDO2 project where we could interview security experts involved at each step of the security process. In this project, security experts of an aircraft company wanted to improve their security process in order to increase the assurance on the final security solution enforced on their aircraft networks. More precisely, they were interested in enhancing their security requirement practices. This group of security experts included security requirement engineers, risks analysts as well as security testing experts who are involved at different levels of the security process. Our task in this project consisted in proposing the best SRE methodology which will help them in writing good security requirements. However, each security expert had a different point of view on what could constitute a good SRE methodology. As consequence, setting generic evaluation criteria appropriate to any organization is not a good idea. A better approach is to develop a process to elicit these evaluation criteria and their weight from the stakeholders. We applied this methodology to our project context. This article consolidates and extends previous contributions [12,13,14,15] to provide in a single and self-contained document explaining the whole methodology. The contributions are as follows:

- The description of a whole methodology for evaluating SRE based on a set of generic evaluation criteria that shall be refined for each organizations.

- The application of this methodology to the IREHDO2 project context.

- An evaluation of three SRE methodologies based on the feedback from security experts.

The rest of the article is structured as follows. In Section 2, we provide an overview of the existing comparative studies. Next, we present our proposed evaluation methodology and its strategy in Section 3. In Section 4, we present a deep study of the characteristics of good security requirements. This work provides a basis for eliciting the characteristics of a good SRE methodology. In Section 5, we describe a process and a tool to elicit SRE methodologies evaluation criteria. Each evaluation criterion must be associated with an evaluation metric. In Section 6, we describe the implementation of our evaluation methodology in the context of IREHDO2. We present our evaluation process to evaluate three SRE methodologies (i.e., STS [16], KAOS [17] and SEPP [18]). At the end, we highlight the pros and cons of each of these three SRE methodologies elicited characteristics serving as evaluation criteria. Finally, we conclude and present our future works in Section 7.

2. Related Works

In the literature, there exists numerous works related to comparative studies that offer varying dimensions of SRE evaluation perspectives. In below, we first present an overview of the related works and later we enlist the three main issues that we identified in their evaluation perspectives. Note that, our literature review does not provide the synthesis or classification of survey studies such as in [19,20].

N. Mayer [21] provided a comparative study of the SRE methodologies based on a domain model consisting of 14 security concepts. These concepts are categorized under three groups: asset-related (e.g., business asset, system asset), risk-related (e.g., risk, impact, threat, threat agent and attack method) and risk treatment related concepts (e.g., security requirements, control).

Fabian et al. [22] proposed a conceptual framework to support the comparative study of existing SRE methodologies. When compared with the modelling framework in [21], this work highlights similar concepts related to risk analysis but also extend them with granular security analysis concepts based on the security confidentiality, integrity and availability properties. In addition, it considers the concepts related to the multi-lateral security requirements analysis that stresses on the compromise between conflicting stakeholders’ security needs [23].

Munante et al. [24] extended the previous comparison frameworks [21,22] with additional evaluation concepts related to model-driven engineering (e.g., tool support, SRE modelling language, formalism). This work concludes that KAOS [25] and secure i* [26], are the most compatible for formal SRE modelling.

Souag et al. [27] proposed a comparison framework to provide a systematic mapping of the reusable concepts and patterns within the existing SRE methodologies. Accordingly, research contributions were classified into 5 categories: security patterns, taxonomies and ontologies, templates and profiles, catalogues and generic models and miscellaneous.

Uznov et al. [28] proposed a comparative analysis of security engineering methodologies using a list of 12 characteristics of security methodologies. This work provides guidelines on the selection of methodologies upon their comprehensiveness, applicability and uniqueness from the perspective of their adaptability to an industrial use.

Mellado et al. [29] provided a systematic review of comparative studies to analyze the internal/external verification and documentation support of the SRE methodologies. The evaluation is principally based on the quality characteristics of good requirements (e.g., traceability, comprehensibility, etc.) referred from the internal standard IEEE 830 [30].

N. Mead [31] provided a comparative analysis of the requirements elicitation techniques based on some criteria such as learnability, client acceptance and durability of the requirements elicitation techniques, tools support etc.

Nhlabatsi et al. [32] proposed a comparative study of SRE methodologies in order to evaluate their support capability regarding the evolution of secure software during the change management process. Accordingly, the criteria address different perspectives such as the modularization, component architectures, change propagation and change impact analysis.

Niazi et al. [33] developed a Requirements Engineering Security Maturity Model to assist software development organizations to better specify the requirements for secure software development. They conducted a questionnaire survey based on security requirements practices derived from Sommerville’s requirements engineering practices [34] to end up with 79 practices classified into 7 categories. This work has the same approach involving stakeholders. However, they focus on assessing the maturity level of security requirements practices, while we aim at helping organizations in choosing a security requirement engineering methodology.

Although these related works discussed many interesting strategies and aspects, they are not sufficient to evaluate the goodness of SRE methodologies because:

- Issue A: Evaluation criteria coverage. SRE methodologies aim at covering the whole SRE process (i.e., elicitation, evaluation and documentation) [22]. From our study, we noted that the majority of the evaluation studies except [29] lack a full emphasis on the whole SRE process [35]. While some works [21,22,31] concentrate on evaluating the extent of support to security requirements elicitation at earlier stages; some others [27] focus on evaluating the extent of support to documentation in terms of reusable patterns or modelling initiatives.

- Issue B: Evaluation criteria affirmation. The evaluation criteria must result from a systematic process or standard method, such as [36], to facilitate reusability. However, in the majority of works, the proposed evaluation criteria were ad hoc and lack affirmation on why the criteria were good enough to be considered for the evaluation [28,31,32]. In this aspect only [29] can be noted as an exceptional case as the evaluation is based on the international standard [30].

- Issue C: Lack of stakeholders’ involvement. This issue concerns the involvement of stakeholders’ views while formulating the evaluation criteria. As highlighted in [37], the requirements process is a human endeavour, and so the requirements method or tool must be able to support the need for stakeholders to communicate their ideas and obtain feedback. In our context, stakeholders refer to the SRE methodology users (e.g., requirements engineers). However, from our observation we found that none of these comparative studies involved SRE experts while formulating the evaluation criteria for an SRE methodology. Moreover, almost all of the works acknowledge (either implicitly/explicitly) the significance of involving stakeholders’ perspectives in the SRE process. For instance, [22] includes a criterion that concerns the integration of stakeholders’ views to support multilateral security requirements analysis.

Altogether, we can conclude that there exists no generic evaluation methodology that can help in identifying the best suitable SRE methodology. Evaluation of an SRE methodology is an enduring problem. As long as new SRE methodologies keep arriving, this necessity of evaluation persists. Having this in mind, we decided to develop a generic evaluation methodology independent from the SRE context of use so that it can be instantiated to varying SRE contexts (e.g., network security, software security).

3. Our SRE Evaluation Methodology

We propose an SRE evaluation methodology that differentiates its strategy from previous comparative studies for two reasons. First, we involve in the process the security experts who are the SRE end-users. Secondly, identifying SRE evaluation criteria corresponds to identifying the characteristics of a good SRE methodology. This is similar to conventional requirements engineering problems, which deal with identifying the requirements of a system-to-be. In our case, the system-to-be is the good SRE methodology, noted the SRE-methodology-to-be. The evaluation criteria are indeed the requirements of the SRE-methodology-to-be, labelled as RM.

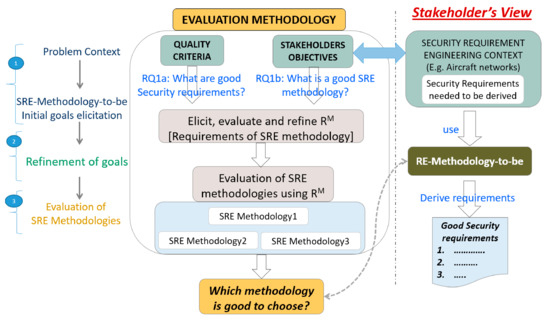

Based on this idea, we propose an evaluation methodology built on the classical idea of requirements engineering approaches. It facilitates the elicitation of the evaluation criteria of the SRE-methodology-to-be considering the SRE context of the stakeholders. Figure 1 depicts an overview of our approach. Similar to the RE process, it subsumes three steps: (1) identifying the problem context and eliciting the initial high-level characteristic goal. This is performed by coupling the stakeholder’s working SRE context with the quality criteria of good security requirements; (2) refining the high-level characteristic goals into the final requirements of the SRE methodology-to-be (RM); (3) the final step deals with the evaluation of the existing SRE methodologies using the elicited requirements (RM) from step 2.

Figure 1.

Our evaluation methodology.

The first step concerns the actual RE context of the system-to-be in which the requirements engineers intend to use the SRE-Methodology-to-be. The SRE methodology users represent the security experts who are considered as stakeholders in our approach. This involvement of security experts is mandatory to improve effective communication among them. Furthermore, works [17,38] consider the lack of people involvement to be one of the major requirement issues.

Ideally, the ultimate goal of the security experts is to derive good security requirements regardless of the SRE context [29,39]. The SRE methodology is a way to achieve this goal. Therefore, the elicitation of the initial characteristics features a brainstorming session driven by further refined two research questions: What are good security requirements? And what is a good security requirement engineering methodology?

The first sub-question helps to setup a common understanding of the characteristics of good quality security requirements. This study is independent from the SRE context and considers the evaluation criteria coverage issue (issue A). This understanding will eventually drive the second sub-question, which helps to capture common perspectives of stakeholders’ anticipations over an ideal SRE methodology-to-be in their SRE context and handle the stakeholders’ involvement issue (issue C).

Our evaluation methodology follows a pure goal-based approach for eliciting the requirements (RM) of the SRE-Methodology-to-be. We propose to use the goal modelling notation KAOS [17] to represent the goals refinement hierarchy, since it facilitates the traceability of the refined goals. From a goal-based RE approach, the root goals represent the characteristics of good security requirements. They are refined into sub-goals that ultimately represent the anticipated characteristics of the SRE-methodology-to-be, which are eventually considered as the evaluation criteria. Thus, this goal-based refinement process helps in affirming the formulation of evaluation criteria formally, which responds to the issue B.

4. How to Qualify Good Security Requirements?

The common goal of any research contribution in the SRE community is ultimately to facilitate capturing good security requirements [29,39,40,41]. If the security requirements are error-prone (i.e., ambiguous, incorrect, inconsistent) then the security design will be ineffective regardless of the successful implementation of efficient security solutions [42]. For instance, let’s take as an example the security requirement that states: “The data flow between device1 and device2 must be encrypted by a strong encryption algorithm”. This requirement is ambiguous, because it does not explicitly define what a strong encryption algorithm means. This ambiguity may lead to false assumptions concerning the rigor of security protection, which eventually impacts the decisions related to the secure solutions.

The RE literature features numerous works describing different characteristics of good security requirements (a.k.a. quality criteria) such as unambiguous, traceable, consistent, etc. These characteristics help to verify and validate the quality aspects (i.e., the goodness) of security requirements. Nonetheless, there exists no consensus on how to characterize a good security requirement. In addition, there is no one complete and consistent set of characteristics [43].

In this context, we studied 185 definitions from 17 literature works depicted in Table 1. Different sources have listed different sets of criteria defining different characteristics of good requirements. The objective of this survey was to identify and study all the concepts discussed in each of the definitions, thereby analyzing the possibility to reach a consensus.

Table 1.

Quality Criteria—consolidated sources list.

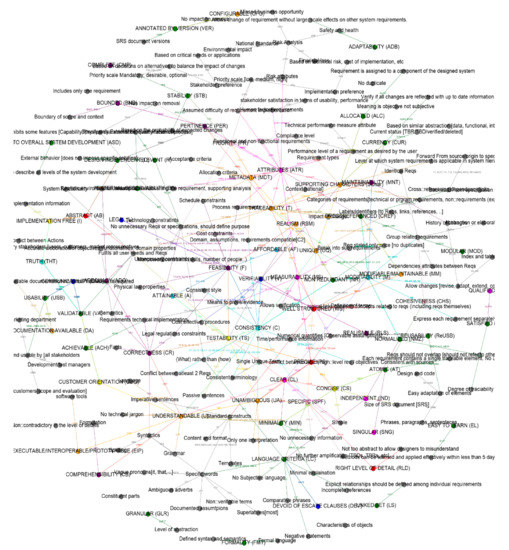

Since, the list being huge and the definitions complex, we developed a semantic graph-based analysis tool using the python graph module NetworkX [55]. This allows us to formalize the definition and analyze the similarities or differences between the definitions. The nodes in the graph represent the criterion names and the concepts concerning the respective definitions. The edges correspond to the reference links expressing the semantic relation between a criterion and its associated concepts or between some criteria. For labelling the reference links (edges), we used a standard format by associating the abbreviation of the criteria with the source ID of the respective authors in Table 1 that propose the criterion. This ensures the unique interpretation of the reference links in the graph. For instance, the edge labelled M8 from node “modifiability” and node “express each requirements separately” means IEEE 830 1998 [30] (Source ID 8) refers to expressing each requirements separately in the definition of modifiability.

Figure 2 shows the complete view of the resulting semantic graph generated using Gephi tool [56]. The first result of this analysis produced a complex graph containing 212 nodes and 278 edges. The graph projects a total of 71 criterion nodes and 141 concept nodes. Every node is connected in the graph, highlighting the complexity of the semantic dependencies between the quality criteria. Such graph exhibits similarities between criteria. Indeed, when two criteria C1 and C2 refer, respectively, to a set of concepts D1 and D2 in their definitions such that D1 ⊆ D2, thus we can conclude that criterion C2 is more generic than criterion C1. In addition, the semantic graph showed ambiguities in some definitions that make self-references. Figure 3 depicts an example of ambiguous definitions in which the definitions precise (PS), concise (CS) and clear (CL) from the authors result in a cyclic referencing. This opens a new problem that might require a proper research to analyze the semantic meaning of each criterion definition.

Figure 2.

Complete view of the criteria conceptual graph.

Figure 3.

Semantic dependencies—cyclic references.

In our evaluation methodology context, our objective is defining an exhaustive list of the existing characteristics that can be integrated within any SRE process. Suitably, we needed something simpler that can be used as a standard basis for eliciting the characteristics of a good SRE methodology. The semantic graph helped us in identifying a total of 20 distinctive criteria definitions. However, we have observed many variations in their corresponding definitions (e.g., different authors, for similar criteria, have defined different names). This entailed into defining a weaving methodology to express these variations.

The main goal of our weaving methodology is to showcase the similarities in the criteria propositions of the unified list in a tabular format that featured a weaving strategy. Table 2 consolidates our weaving results, which extends the results in [12]. Firstly, we gave a unique identifier as a reference to each class of quality characteristics. We denote the term criterion (represented as C) that gives us a list of criteria as C1 to C20 (see Table 2). In addition, we added a one-line definition to each criterion. If the characteristic is defined in ISO 29148, we use the standard definition. Otherwise, we take references from respective authors if the characteristic description is straight forward (e.g., C8). When the characteristic descriptions seemed ambiguous (e.g., C10), we provide our own interpretation.

Table 2.

Characteristics of good security requirements.

Secondly, we used colors (i.e., blue and orange) and typographical emphasis (i.e., bold, underlined and italic) to differentiate some special cases as follows: Criterion definitions are highlighted in blue color when defined by only a single author (e.g., C13). When different authors employ different names to describe similar quality characteristics (e.g., C3), then the respective criterion definition is emphasized in italic text. When a single author employs different names to describe similar quality characteristics (e.g., C3 by S13), then the respective criterion definition is emphasized in orange. Contrarily, when the same criterion name is used to describe different quality characteristics (same or different authors), then the characteristic name reflecting the uncommon mapping is underlined (e.g., C6 by S5 and C15 by S15).

Thirdly, we distinguish the applicability of a criterion. If mentioned All the Applicability column in Table 2, the respective quality characteristic requires to verify the whole set of requirements specifications document (e.g., C2). If mentioned Each, the respective quality characteristic targets only a single (or a specific set of) requirement(s) (e.g., C20). See the Applicability column in Table 2. Finally, we defined credibility scores to show the frequency of citations. We used qualitative scale high, medium and low. Credibility is given high when cited by at least 15 authors; medium with at least 8 authors; and low when at least 4 authors; very low when cited by less than 4 authors.

Altogether, Table 2 overviews our comprehensive review of the non-consensus issue concerning the characteristics definitions.

Criterion C1 ensures that final set requirement specifications sufficiently express all the needs of stakeholders, respecting all the considerable aspects and scenarios. The difficulty in fulfilling this criterion corresponds to identification of all considerable aspects such as stakeholder security and risk management objectives. In a way this criterion insists on efficient requirements elicitation and risk analysis process. The common keyword used to represent this criterion is complete with credibility high. Applicability of this requirement implies either to an entire set of requirements or to a set of requirements.

Criterion C2 ensures that all requirements are compatible and consistent with one another. Accordingly, this criterion C2 insists on verifying if there exist any conflicts in terms of contradicting requirement statements, improper representation of viewpoints or possibility of incompatible interpretations of a statement, etc. The difficulty in fulfilling this criterion corresponds to establishment the right level of trade-off. This criterion indirectly contributes to satisfaction of requirement completeness. The common keyword used is consistent with credibility as high. Applicability of this criterion concerns with either an entire set of requirements or a group of requirements.

Criterion C3 ensures that all those derived requirements within the document are accomplishable within the given constrains. ISO defines some of the considerable constraints such as time, cost and process control, financial, technical, legal and regulatory. In addition, dependency constrains and domain constraints [17] can also be considered. Constraints can be viewed in two ways, one as they are imposed by stakeholders and the other based on operational context. On the whole, this criterion insists on identifying and acquiring all the possible constraints in terms of financial or technological implementations. Applicability of this criterion concerns with either an entire set of requirements or a group of requirements or an individual requirement. Credibility of this criterion is also high. The common keyword used is feasible, affordable and other keywords are realism and legal.

Criterion C4 ensures that all requirements within the document are well categorized and well documented in a structured manner so that it is maintainable with fewer changes. Credibility of this criterion is low and common keyword used is structured.

Criterion C4 ensures that all requirements within the document are prioritized and well documented in a structured manner. Credibility of this criterion is low and common keyword used is structured.

Criterion C5 ensures that specified within the document are traceable in both forward and backward ways. Credibility of this criterion is high and common keyword used is traceable. Some sources have highlighted different aspects in the same context; hence different keywords were used accordingly. The keywords are cohesiveness, allocated, satisfied/qualified.

Criterion C6 ensures requirements derived do not specify the implementation details of the solution instead it specifies what is needed. Credibility of this criterion is medium and the keywords used are implementation free, external observability, design independent and abstract.

Criterion C7 ensures that the document containing all set of derived requirements is modifiable and adaptable to changes. It is to note that this is similar to a Meta characteristic to criterion C4 (well structured). Credibility of this criterion is medium and the keywords used are modifiable, adaptability.

Criterion C8 ensures that there is no redundancy of information corresponding requirement needs. It insists during the requirements elicitation process, one must clearly be able to distinguish between redundant stakeholder needs and non-redundant stakeholder needs. Credibility of this criterion is low and the common keyword used is non-redundant.

Criterion 9 ensures that all the requirements in the document are uniquely identifiable. This criterion helps to achieve the traceability feature (C5). Credibility of this criterion is low and the common keyword used is unique.

Criterion C10 ensures that completeness feature of an individual requirement. In a way it insists on verifying if the stakeholder need is sufficiently elicited. Credibility of this criterion is low and the keywords used are adequacy and validity.

Criterion C11 ensures that requirements are derived using simple terminology without usage of technical jargon. Technical jargon corresponds to terminology used by different teams working in different areas of business operational environments. For example, terminology used in software development environment is difficult to be understood by individuals belonging to organizational environment. Hence, this criterion enforces that the derived requirement must be comprehensible to all the readers of the document with in the business environment. Credibility of this criterion is medium and the common keyword used is comprehensibility. Some sources have highlighted different aspects in the same context; hence accordingly different keywords used. They are customer or user orientation and clear.

Criterion C12 ensures that the derived requirements are precise enough and does not lead to any misinterpretations. It is to note that this criterion is different from the previous one C11 (comprehensibility). C11 insists on the aspect that there is no difficulty in the comprehension of the text (phrase or sentence), in the way it was written (focus on terminology). In addition, C12 insists on the aspect that the content of the text maintains careful precision while expressing the idea so that it does not lead to misinterpretation of the idea. In end, this criterion emphasizes on the verification that comprehension of the text is not wrong. It focuses on punctuation and meaning of terminology or vocabulary used. In a way, this criterion can be viewed as a meta-characteristic of the criterion C11. Credibility of this criterion is high and the common keyword used is unambiguous. Another keyword used is precise.

Criterion C13, it ensures that requirements derived can be measured with some quantifiable values. For example, consider a requirement need “a service must be available to all the customers”. This need cannot be measured and while eliciting such needs, it is important to elicit measurable information. For this derived requirement for this need can say “a service must be available on an average to ‘x’ number of customers at ‘t’ units of time”. This way, the requirements can be measured. Credibility of this criterion is low and the common keyword used is measurable.

Criterion C14 ensures that the derived requirement specifies what is needed and it has not got any unnecessary information. It is to note that this criterion complements the criterion C10 (adequacy). Credibility of this criterion is medium and the common keywords used are necessary and mandatory. Some sources have highlighted different aspects in the same context; hence accordingly different keywords used. They are bounded, pertinence and relevance.

Criterion C15 ensures that requirement must possess accurate and up to date information. Credibility of this criterion is medium and the common keyword used is correct.

Criterion C16 ensures that one requirement derives one need. For example, if a requirement need says “entrance to aircraft allowed to customers with boarding pass and special emergency pass”. This is not singular or atomic in nature. It is speaking allowing customers of two different types. One can split this into two as: “entrance to aircraft allowed to customers with boarding pass” and “entrance to aircraft allowed to customer’s special emergency pass”. This way it helps to defined more precisely what does it mean by saying special or emergency. Accordingly, we can say that this criterion C16 contributes towards C13 (measured). Credibility of this criterion is low and the keywords used are singular and atomic.

Criterion C17, it ensures that each of the requirements is verifiable against the constraints, standards and regulations to ensure the correctness of the requirements. This criterion somewhere again falls between C10 (adequacy) and C15 (Accurate). Credibility of this criterion is high and the common keyword used is verifiability.

Criterion C18, it ensures the formulation of requirement must follow some standard so that they are understandable globally. Credibility of this criterion is low and the common keywords used are requirement language criteria and devoid of escape clauses.

Criterion C19, it ensures that requirements must be formulated in such a way that they are reusable. This criterion emphasizes on the using some common pattern for similar type of requirement needs. Credibility of this criterion is rare and the common keyword is usability.

Criterion C20, it ensures that every requirement should be identified with some metadata such as attributes, acceptance criteria. This way, it facilitates in their validation and evaluation. Credibility of this criterion is rare and the keyword used is Metadata.

Since the interpretation of a definition can differ between different people with varying expertise levels, the table contents can raise several questions. This implies that our weaving methodology strategy provides a way to trigger a discussion between experts. This will lead to brainstorming, which serves our purpose of initiating the elicitation process of our RE based evaluation methodology.

5. What Is a Good SRE Methodology?

Since this question depends on the SRE context, we describe the instantiation of our evaluation methodology to the network SRE context from the IREHDO2 project. The first two steps concern the elicitation of the characteristics of a good SRE methodology from the network SRE context. While the final step concerns the evaluation of the SRE methodologies with regards to the elicited characteristics.

5.1. Step1: Problem Context and Initial Requirement Analysis

The initial step of our approach consists in analysing the security problem context of the security experts. Accordingly, this step deals with interviewing the people involved in the security engineering process. We used the brainstorming technique to encourage people to exchange ideas on “the best suitable SRE methodology” that best fits their needs. However, eliciting requirements is a hard task [31]. The challenge here comes while organizing the brainstormed thoughts and ideas in a structured manner. For this, meetings/brainstorming with stakeholders must be controlled in order to be effective.

Therefore we employed the elicitation technique proposed by SABSA [9]. The SABSA framework handles this elicitation issue by proposing a list of generic high-level business security concerns, called business attributes. These business attributes might lead to several interpretations. Interpretation of business attributes is refined for a specific problem context by a security architect who interacts with the business stakeholders. These business attributes guide the interaction during the elicitation phase. Respectively, in our case, our list of 20 quality criteria characterizing good security requirements given in Table 2 are similar to business attributes in SABSA. Based on this list, we developed an elicitation tool to trigger the discussions, see Table 3.

Table 3.

Elicitation tool (sample).

The first three columns consolidate Table 2. They subsume, a unique identifier, a short one-line definition and corresponding synonyms found in the literature. The last column describes the quality criteria via a set of questions, each reflecting different perspectives of the respective criterion definitions. We also provided the references from which we extracted the sample set of questions. Altogether, each of the four columns corresponds to a different way to explain each criterion in order to facilitate the understanding as well as to ignite brainstorming. This process aims at refining the generic and abstract criteria into specific and context-dependent SRE evaluation criteria that reflect the actual needs of the stakeholders involved in the SRE process.

5.2. Step2: Refinement (RM) Requirement Analysis

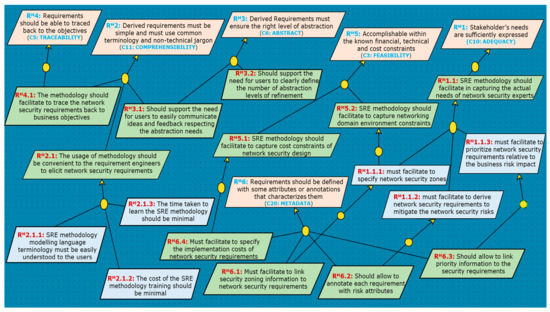

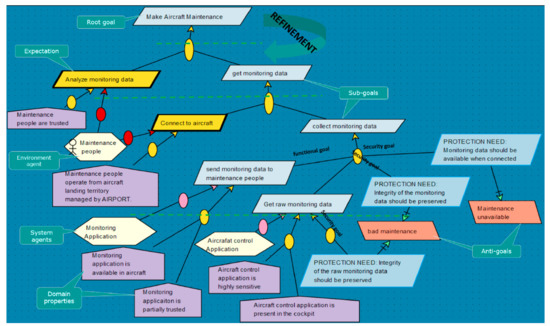

The second step of our evaluation approach deals with understanding the transformation of high-level abstract characteristic goals into verifiable evaluation criteria. Respectively, the high-level abstract goals realized in step 1 are coarse-grained and should be refined into sub-goals fitting specific demands of the security experts. This refinement process is performed in collaboration with the security experts. Figure 4 provides a sample view of the criteria refinement using KAOS goal modelling notation. This goal refinement extends the study [14,15].

Figure 4.

SRE-methodology-to-be goals refinement (Sample).

The refinement uses the AND-construct and is continued until the final refined goals are realized as objectively verifiable. Thus, the leaf goal nodes become an evaluation criteria RM. Tracing the goals refinement conforms the correctness of the final evaluation criteria RM. Since, we used natural language to describe the criteria and goal modelling notation to express the refinement, the affirmation of evaluation criteria is self-contained in the model. The high-level goals are the quality criteria from our elicitation tool (goals in orange). The elicited interpretations are the immediate sub-goals (in green). It is to note that different colouring of goals is provided solely to facilitate the understanding of the readers and this colouring is not compliant with KAOS notation.

In below, we present our arguments relative to the refinement of six quality criteria given in Table 3. It is to note that our arguments are based on our discussions and initial feedback with the security experts involved in the brainstorming process. The goal refinement is subjected to changes with varying needs of the stakeholders.

Adequacy (C10) and Metadata (C20)

The Adequacy criterion stresses that the actual needs of all the stakeholders must be captured. In our project, we refer to the security experts working in network SRE context. We refine the high-level quality goal pertaining to the adequacy quality criterion (Cf. C10 in Figure 4) into “RM1.1: The SRE-Methodology-to-be should facilitate in capturing the actual needs of network security experts”.

Since network security zoning drives the elicitation of network security requirements at early stages, we have refined this goal into three sub-goals: RM1.1.1 and RM1.1.2 to validate that the SRE-Methodology-to-be facilitates the specification of security zones and derived network security requirements to mitigate risks. However, in order to determine the rigor of security/validation measures required at each security zone, the security experts must also need to be able to prioritize the elicited security requirements based on the risk impact. This requisite of risk analysts is derived into RM1.1.3, to validate if the features allow the prioritization of network security requirements.

However, to ensure the verification these information are captured [35], describes risk related information and environment constraints to be linked as requirement attributes/metadata (see C20 in Table 2). This confirms the refinement of sub-goals RM6.1, RM6.2, RM6.3 from the quality criterion C20 (RM6) in compliance with the aforementioned sub-goals (i.e., RM1.1.1, RM1.1.2 and RM1.1.3).

Comprehensibility (C11)

The quality criterion comprehensibility (C11) has been refined into “RM2.1: The methodology usage should be convenient to the requirement engineers to elicit network security requirements”. This concern drives the main motivation for all of the model-based RE approaches because a security requirement not understood cannot be analyzed or implemented properly.

In this regard, the refined sub-goal RM2.1.1 refers to verify the ease of use of the language of the SRE-Methodology-to-be itself. That means, which language is understandable to the users? A formal language? UML? Or some natural language? This aspect completely depends on the language familiarity of the stakeholders who are going to use the SRE-Methodology-to-be. If they are familiar with formal notations then using formal languages is better. If they are familiar with UML, then it is better to choose the requirement engineering methodology accordingly. Ref. [37] argues that verifying the suitability for agreement with the end-user indicates the extent to which the notation is understandable (as opposed to ‘writeable’) by someone without formal training. Furthermore, different stakeholders, despite their familiarity, can understand the same requirements differently, which requires negotiation schemes to calculate an agreement [57]. In addition, learning and mastering a new language has a cost in terms of both money and time [28,31]. For example, a five day training course for SABSA framework costs around 3000 € [58]. In this work, we do not consider these negotiation aspects. Instead, we confine our evaluation study to understanding the notation, learnability duration and ease of SRE modelling. This perspective is covered by the sub-goals RM2.1.1, RM2.1.2 and RM2.1.3

Abstract (C6)

In practice, security requirements evolve gradually building upon the ideas/perspectives of the subject experts (e.g., business analysists, security architects and network security engineers) who work at different levels of abstraction in a network development cycle. This requires an effective communication among the subject experts and the requirement engineers. Therefore, the SRE-Methodology-to-be modelling language should support the needs of the people to easily communicate the ideas and feedback relative to the security requirements elicitation [37,45].

On the other hand, with reference to the definition of the implementation free criterion from [35], the SRE-Methodology-to-be has to ensure that the stated security requirements express only the ‘WHAT’ aspects of security needs and must avoid the ‘HOW’ aspects of describing the security solutions. This is achieved by accommodating the separation of concerns so that the readers of the requirements specification should need to find only those parts of the requirements specification that are relevant to their area of expertise and all the other details must be hidden.

Respectively, the refinement of quality criterion abstract (C6) includes two sub-goals: RM3.1 to validate that the SRE-Methodology-to-be facilitates the communication between the stakeholders and RM3.2 to guarantee that the SRE-Methodology-to-be allows the specification of a number of abstraction levels for expressing the separation of concerns.

In some cases, it is possible that a sub-goal can be refined from multiple high-level goals; e.g., RM3.1 sub-goal which states “the derived requirements must respect the abstraction level of respective stakeholders involved in designing and building aircraft network systems”. This sub-goal was initially refined from the root goal node RM3 related to the abstract characteristic criterion (see Figure 4). However, we discovered it can also be refined from RM2 concerning comprehensibility characteristic criterion with a justification stating that the requirements not respecting the abstraction requirements of the stakeholders are not comprehensible. This type of refinement patterns explains the semantic dependencies between the quality characteristics. It also explicitly reflects the merging of the different security experts’ points of views.

Traceability (C3) and Feasibility (C5)

Finally, goals RM4.1, RM5.1 and RM6.4 concern the supportability of the SRE methodology with reference to traceability and feasibility characteristics (i.e., C3 and C5 in Table 2) in network SRE context. Traceability is defined as the ability to establish the link between requirements to the source business objectives [35]. These requirements express the capability to verify which high-level network security requirement is impacted when any inconsistency or anomaly is found in network security and monitoring configurations. Feasibility characteristics, on the other hand, concern the ability to verify if the security requirements are realizable within the budget schedule and technology constraints [35]. These characteristics were one of the primary objectives of IREHDO2 project.

The refinement process is performed until the final refined goals are realized as objectively verifiable. The final sub-goals (leaf nodes) are then qualified as evaluation criteria.

Table 4 provides a sample of the final list of elicited evaluation criteria in our network SRE context within the IREHDO2 project.

Table 4.

Elicited evaluation criteria (Sample).

Finally, our approach which involves the stakeholders has shown its benefits. We elicited new evaluation criteria (namely RM3.2, RM6.1 and RM6.4) that were not proposed by previous comparison/evaluation studies.

Evaluation Methods and Metrics

An evaluation method and metric shall be associated to each evaluation criterion. The type of evaluation and respected performance metrics can differ depending on to the type of evaluation criteria. Let’s consider evaluation criterion RM6.2. Linking risk attributes to security requirements confirms the integration of risk analysis process to security requirement analysis. However, an evaluation metric shall define to what extent SRE methods can support this integration (Cf. Table 5).

Table 5.

Verification method for RM6.2.

The qualitative scale used for the performance measure expresses the degree of supportability, i.e., high—highly supportable, medium—partially supportable, low—less likely supportable and nil—not supportable. Wherein the colouring is used to enhance the understanding.

The type of measurements (i.e., nominal/ordinal/interval/ratio [59]) also vary with regards to the type of criteria. Nominal scaling uses some labels that don’t have order to differentiate between different subjects (e.g., male/female). Ordinal scaling uses rank ordering to sort the subjects (e.g., good/neutral/poor or small/big). Finally, interval and ratio scales use some quantitative numeric values, which allows the estimation of the degree of difference between the subjects in terms of some meaningful measurement units (e.g., length, duration, angles etc.). While interval scaling describes the exact and equidistant difference between the units (e.g., number of hours or number of days) allowing statistical analysis, it does not have true zero which means nothingness. A ratio scale is the most informative as it allows ranking and differences between variables, along with the information on the value of a true zero.

For instance, the measurement scale for RM6.2 reflects the ordinal scale, which verifies if each security requirement can be linked to risk attributes such as risk likelihood, control strength, threat events and risk impact with reference to FAIR taxonomy (https://www.fairinstitute.org/what-is-fair—accessed 7 August 2021). Other evaluation criteria may require different verification approach. For instance, RM2.1.1 concerns comprehensibility aspects of the terminology used by SRE-methodology. The verification metric employed for this criterion can refer to the satisfaction survey of the security experts. Respectively, RM2.1.1 uses ordinal scale, which sorts the understandability factor of SRE methods based on the degree of support required; RM2.1.3 uses interval scale, which allows the estimation of the degree of learnability of the terminology used by the SRE-methodology-to-be in terms of number of weeks. Finally, evaluation criterion RM2.1.2, related to the cost of the training -ratio scale-, requires the security experts to have knowledge on the internal budget. At the end of step 2, the verification methods and the associated metrics for each evaluation criterion is agreed (e.g., internal budget, time constraints) in accordance with the specific needs of the stakeholders (e.g., security experts) involved in the process.

Likewise, each evaluation criterion is accorded with a verification method, which will be used during the evaluation process. It is to note that these verification methods and measured metrics must be defined in compliance with the needs of the security experts who intend to use SRE methodology-to-be. This clear separation of evaluation criteria to the verification methods and respective measurement metrics permits the reusability of the evaluation criteria as well as simplifies justifying the subjectivity of the criterion interpretation and relative evaluation perspectives.

6. Evaluation of Existing SRE Approaches

This section describes the final step of our SRE evaluation methodology. It concerns the assessment of the SRE approaches against the evaluation criteria refined in step2. Our evaluation is a qualitative assessment that is performed in collaboration with the security experts. We organized two meeting sessions (i.e., precisely 3 h brainstorming and discussions for each) with a time gap of around 2 months.

We performed the evaluation in two iterations. In the first iteration, we—the authors of this article—acted as stakeholders (i.e., SRE analysts) and tested three SRE approaches, i.e., STS, Secure KAOS and SEPP using an example scenario. First, a description of the system-to-be is presented to three different persons (playing the roles of RE analysts) from our research group whose initial knowledge fits the aforementioned methodologies the best. Then, each person has been asked to elaborate the requirements for the system-to-be using the methodology that was assigned to him/her. During this process, the persons (acting as SRE analysts) were not allowed to communicate with each other during the scenario analysis phase. Each of them had come up with a different list of security requirements for the system-to-be. The resulting SRE models have been presented during a meeting that involved four security experts. Their feedback was recorded as our initial evaluation results, which enabled us to identify and select the SRE approach found interesting to the experts at first instance.

In the second iteration, the actual security experts are directly asked to test the SRE approach selected during the first iteration. The feedback of this second iteration enabled us to finalize the evaluation results. In each iteration a different use case scenario is employed in order to ensure the credibility of the capture of the evaluation experience. In below, we provide the details of the evaluation performed in two iterations.

6.1. Evaluation Iteration 1—Use Case Scenario 1

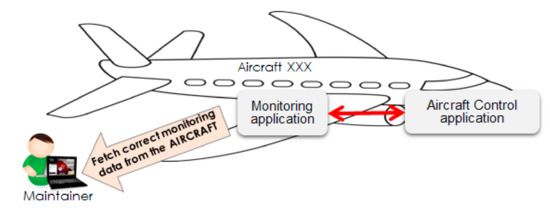

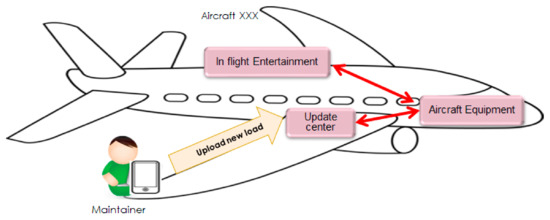

We first present the use case scenario employed in the first iteration. The scenario concerns a task related to the aircraft maintenance process ensuring compliance to some safety regulations. The objective of this task is to monitor the on-board aircraft system by verifying specific parameters (e.g., fuel indicator) in order to ensure the readiness of the aircraft prior to taking the next trip. The Onboard aircraft system consists in two applications, i.e., aircraft control application and monitoring application (Cf. Figure 5). These two applications are connected to each other via an internal avionic bus network (represented by a red double arrow line in Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Example scenario 1.

The aircraft control application captures the observed parameters from various sensors and indicators of the aircraft system and transmits them to the monitoring application. Every time the aircraft has landed, the responsible person (i.e., maintainer) must connect his/her laptop to the monitoring application in order to fetch the monitored parameters. However, there is no direct access to the monitoring application. The connection is permitted only using the secured network connection within the secured premises of the aircraft. The maintainer must carry the laptop to the airport ground in order to access the network. In this process, the maintainer is assumed to be trusted, while the laptop is untrusted.

The business risk impact of this scenario is expressed in terms of integrity and availability of the monitored parameters. These parameters influence the critical decision process that decides whether the aircraft is ready to fly again or has to be retained for further inspection. Non-availability of these parameters may delay the inspection process that may incur loss in terms of reducing the number of trips per day. While the lack of integrity may cause serious problems when the faulty aircraft is assumed as correctly functioning and permitted to take next trip.

Therefore, the aircraft network security design solutions must ensure a trusted transmission of parameters from the monitoring application to the aircraft control application and then to the laptop of the maintenance people. It should also ensure that the access to the aircraft control application is restricted and the laptop is allowed to connect to the monitoring application only. This implies network security requirements to closely monitor communication traffic between the laptop and the monitoring application. In this regard, some example security measures may include: a VPN connection with a strong encryption algorithm, configuring firewalls, authentication on the WIFI access point or router. The security experts wanted to confirm that these measures are sufficient to mitigate the risks. In addition, they wanted to verify the cost of the network security solutions to compare different choices; e.g., maintenance people can potentially connect to the aircraft using an Ethernet cable or a wireless connection.

The first iteration concerns the implementation of the aforementioned scenario using three SRE methods: Secure KAOS, STS and SEPP. The discussion part consolidates our observations on the SRE modelling experience of each method. We highlight the relative evaluation criteria in parenthesis to facilitate the understanding of which part of the observations are subjects to which evaluation criteria. Finally, we provide the initial feedback and evaluation results of the first iteration.

6.1.1. Scenario Implementation Using Secure KAOS

KAOS [17] (Knowledge Acquisition automated Specification or Keep All Objectives Satisfied), is a goal-oriented RE methodology developed as a joint collaboration of research work between the University of Oregon and the University of Louvain (Belgium) in 1990. The KAOS methodology mixes the top-down and bottom-up approaches. The goal modelling activity focuses on eliciting goals and refining them into sub-goals until they are atomic. Goal refinement is specified via AND/OR constructs. When a goal cannot be refined further, it is called as a requirement of the system-to-be and is assigned to an agent (to either environment or system agents) represented. When a requirement concerns an environment agent (e.g., human), it is called an expectation. Altogether, identifying and refining security goals and assigning them to agents are the core activities that are represented as goal and responsibility models. Authors of KAOS propose a formal specification language based on temporal logic. They also specify formal generic refinement patterns to validate goals refinements.

Our experimentation was conducted using the free trial version of Objectiver [60] the official tool maintained by Respect-IT. Figure 6 depicts a sample of the goal model specified in our example scenario context. It required some effort to become acquainted with the tool and its terminology through the help of guidelines and cited references (refer to RM2.1.1 and RM2.1.3 criteria). In particular, the security experts expressed some concerns regarding the formal temporal logic language (RM2.1.1). They prefer the textual notation even it is more ambiguous.

Figure 6.

Secure KAOS goal specification (sample).

KAOS drives the RE analyst to define agents later in the RE process. As a consequence, it does not help in expressing the relation between the agents and their interaction dependencies which is important for the network design. For instance, while defining network agents (e.g., an access control system) in our scenario analysis, we encountered issues when we needed to add a new device in the network architecture. It was difficult to express the dependencies between network agents. In this regard, a conceptual diagram of the network would have been more concise and clearer. As a consequence, we had a difficulty in specifying network security requirements on network agents, particularly relative to security zoning (RM3.1). Furthermore, KAOS provides features to express abstractions and the notation provides a good support to achieve traceability by linking goals and sub-goals (RM4.1). However, it does not guide the security requirement engineers in asking the right questions at the right time to structure the security engineering process (RM3.2).

Regarding integration of risk analysis concepts, the link between security requirements and risk information is explicitly expressed using the concepts of obstacles/anti-goals that are represented as relations such as obstruction/resolution. For example, in Figure 6, security goal “PROTECTION NEED: monitoring data should be available when connected” resolves anti-goal “maintenance unavailable”. The resolution link is expressed using green arrowhead. These anti-goals can be further refined such as ‘normal’ goals resulting in the specification of attack trees. Obstacles/Anti-goals include two risk attributes likelihood and criticality (RM6.2) while security goals are attributed with ordinal priority scale (RM6.3). However, there is no explicit relationship defined between the priority of a security goal/requirement and the risk of an associated obstacle. In addition, it helps in observing the environmental constraints upon the goals through domain properties. (e.g., physical laws). For instance, the trust assumptions on agents are expressed using the domain properties (Cf. Figure 6).

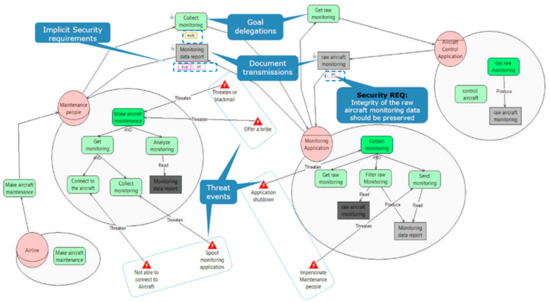

6.1.2. Scenario Implementation Using STS

STS (Secure Socio-technical Systems) [16] implements the agent-oriented approach which mainly focuses on early elicitation of security requirements based on the social dependency interaction relationships. Similar to KAOS, the STS framework offers the possibility to create composite goals via the AND/OR constructs. However, the respective goals and sub-goals are determined in the scope of each actor. An actor can be either a role or an agent. This methodology mainly defines three views: social view, authorization view and information view. The social relationships between actors are manifested by the relationships such as goal delegation and resource provision. This is modelled in the social view. Delegated goal implies the dependency of the interaction. An actor depends on another actor to achieve a goal. In addition, the social relationships between actors may also include the exchange of documents (informational resources) that contain necessary information for the achievement of a goal. STS captures this exchange via the relationship: document transmission (resource provision). The ownerships of the resources are modelled in the authorization view. This view also permits to explicitly define the authorization rules over the access permissions on the documents (resources). Another view called the information view allows to define the primitives and relationships that permit the differentiation between the information (content) and the representation of the information (document).

STS is supported by a tool of the same name. The tool is not open source but it is freely available to public use (RM2.1.2). The usage of a simple terminology as well as the user-friendly tool took less effort to become used to the overall concepts and terminology (RM2.1.1 and RM2.1.3). The security experts provided a positive feedback concerning the comprehensibility aspects during the first intermediary meeting.

Unlike KAOS, STS does not support full-fledged traceability of the security goals being refined into security requirements (RM4.1). From the STS point of view, the security needs are implicitly expressed either in the form of security constraints attributes (e.g., integrity/availability/non-repudiation, etc.) over the interaction dependencies in the social view; or in the form of constrained permissions (e.g., read/modify/produce/transmit) upon the provision of the resources in the authorization view. Figure 7 highlights the security constraints over delegated goals in blue dashed rectangles, which cannot be refined further into network security requirements (RM3.1).

Figure 7.

STS social view specification (sample).

On the other hand, STS provides a good support to express network agents and interaction dependencies. However, we had an issue in handling the number of dependencies between multiple network agents as the social view grows. Furthermore, from the STS modelling perspective, the abstractions are expressed using the three modeling views (i.e., social view, authorization view, information view). This abstraction perspective respects separation of concerns specific to authorization security problem context only. Similarly to KAOS, STS does not guide the security requirement engineers in asking the right questions at the right time to structure the security engineering process in order to build a security architecture (RM3.2).

In STS, the threat analysis can show the effects of a threating event over goal trees and goal/resource relationships. In addition, it defines attributes (implicit) to link countermeasures to threat events (RM6.2). However, the threat analysis is limited to threat event propagation. Thereby it does not facilitate the expression of security needs upon the threats related to environmental risks. In addition, it does not have a facility to prioritize goals or threats such as in KAOS (RM6.3). Figure 7 shows that the threat event “maintenance unavailable” threatens the goal “make aircraft maintenance”. Likewise, the threat event “bad maintenance” threatens three goals. When the threats are propagated, the threat impact traces back to the root objective node. Respectively, the “maintenance unavailable” threatens the business objective “run business”.

6.1.3. Scenario Implementation Using SEPP

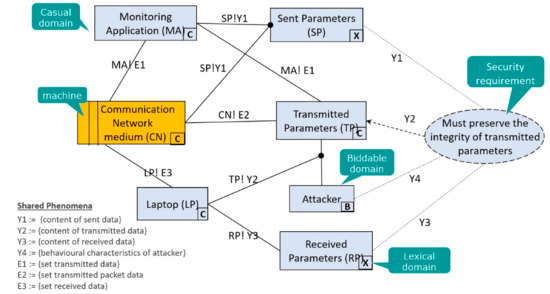

SEPP (Security Engineering Process using Patterns) [18] implements the problem frames approach. In contrast with STS and KAOS, this approach views the stakeholder’s requirements as constrained behavioral characteristics expected within the real physical world. A machine represents the system-to-be that helps to achieve the desired behavior. Problem world represents a part of the real world, in which the machine operates. Problem Domains represent different active entities (agents) in a given problem world upon which the machine operates in order to achieve the desired behavior. Casual domains (noted C in Figure 8) represent system agents. Lexical domains (noted X in Figure 8) represent data. Biddable domains (noted B in Figure 8) represent human agents. A problem is characterized as dependencies in terms of the shared phenomena (agents interaction attributes) between the machine and the problem domains, in a given problem context. A problem frame is therefore a problem pattern representing the common characteristics of a recognized class of problems. It separates the problems from its solution.

Figure 8.

SEPP SPF diagram (sample).

SEPP extends the concepts and terminology of the PF to security problem analysis in a particular SRE context. It guides the RE analyst to define security problem patterns, called as security problem frames (SPF), separately from the security solution patterns, called as concertized security problem frames (CSPF). Accordingly, they have introduced four security problem frames (SPF) and eight concretized security problem frames for authentication, confidential data transmission, distribution of secrets and integrity preserving data transmission. It is to note that, CSPF are the next abstraction level instantiations of the security problem frames which define some generic security mechanisms to solve security problems.

Figure 8 depicts a sample of our secure problem frames specification for integrity protection scheme. Security requirements are constrained on the communication network domain. The links between domains depict that there are some shared phenomena (i.e., shared attributes). The non-availability of a tool for SEPP made our experimentation hard (RM2.1.2). It took some extra effort to become acquainted with the concepts and terminology even with the help of the cited references (RM2.1.1 and RM2.1.3). As a consequence, we have designed all the SPF and CSPF patterns models (for the scenario) manually which consumed more time (RM2.1.3). In addition, there is a traceability issue (RM4.1) as well. During our experimentation, we had other issues in knowing all the acting domains in a network environment, in particular during the early stages. A network design in hand will facilitate the problem analysis.

From the SEPP perspective, security problems (security goals) are identified using the what-if analysis technique similar to the Hazard analysis [61]. However, it does not provide explicit linking between the risk and the associated security goal (RM6.2). This makes the risk definition implicit. The constraints on the security requirements are expressed in terms of pre-conditions attributes of SPF. These are the formalized conditions that must be satisfied by the problem environment “on prior”, i.e., before applying the security problem frame. Similarly, the post-conditions attributes correspond to the formal expression of the security requirements.

Furthermore, SEPP facilitates a two-level abstraction through separation of security problems from solutions in generic perspective. However, this abstraction perspective respects the separation of concerns specific to the authorization security problem context, which does not help to explicitly describe the separation of concerns of the agents/actors specific to the network security problem context (RM3.2). Lastly, similar to STS, it does not support attribute security requirements with either priority or implementation cost related information (RM6.3 and RM6.4).

6.1.4. Evaluation at Iteration 1—Results and Discussion

In Table 6, we resumed the evaluation results of the SRE methodologies to provide a consolidated view for comparison. First column displays the high-level root goals of evaluation criteria (Cf. Figure 4). Second column lists the elicited criteria that correspond to the leaf nodes in Figure 4. The remaining three columns display the respective measurement scales for each of the three SRE methods.

Table 6.

Sample of the evaluation results.

Each approach exhibits different features. STS is interesting when it concerns comprehensibility factors (i.e., RM2.1.1, RM2.1.2, RM2.1.3), Secure KAOS is interesting in terms of traceability aspects (RM4.1) as well as integration of risk analysis information. On the other hand, the modelling terminology and notation of SEPP seemed difficult to learn and adapt. Therefore, comparatively, STS and secure KAOS seem to be more suitable to our SRE context compared to SEPP. However, some of our requirements’ RM were not supported by any of the three methodologies (i.e., RM3.1, RM3.2, RM6.1 and RM6.4).

The criteria RM3.1 and RM6.1 are notably related to the network SRE context that concerns the integration of network security zoning. Without this support, it would be difficult to elicit network security requirements at early stages. Furthermore, the requirement concerning the abstraction characteristic goal cannot be respected by the three SRE methods (RM3.2). As a consequence, expressing the security problem context of all the stakeholders including the business analysts, and the security analysts of all systems connected to the network is still an issue. Finally, none of the three methodologies allows to help in considering the cost of the security requirements (RM6.4).

6.2. Evaluation Iteration 2—Use Case Scenario 2

During the first iteration of the evaluation, the authors of this article acted as stakeholders and tested the SRE models, which were then presented to the actual stakeholders (i.e., security experts) to capture their comments. The second iteration encompasses active participation of stakeholders for evaluating the STS modelling notation that holds highest rating in terms of comprehensibility aspects. The purpose of this second evaluation is capturing the direct feedback from real users’ experience of SRE modelling in STS using a new use case scenario. In below, we first provide the scenario in plain-text description as it was presented to us at the initial step.

The scenario contains two business needs (Cf. Figure 9). The first business need concerns the safety measures related to the aircraft. It implies that the aircraft needs to be updated with correct load information through a portable device. The update center is a sub-component in the aircraft equipment, which reads these load parameters and performs an auto-update. The aircraft network security design must ensure the secure transmission of these parameters between the mobile devices to the on-board update center application. In addition, the direct connectivity of the mobile devices with the aircraft equipment is forbidden.

Figure 9.

Second scenario.

The second business need concerns the in-flight entertainment services to improve passengers’ inflight condition. It describes the necessary functionalities of the aircraft equipment (e.g., passenger entertainment panel) to entertain the passengers during their flight journey. For example, one functionality is to provide the real-time flight status to the passengers. This functionality requires connectivity between the aircraft control panel, centralized on-board entertainment system component and the passengers’ equipment panels. The security needs concern the availability of the aircraft’s information (e.g., speed, altitude, temperature, distance, etc.) to the passengers accessing the respective entertainment system display panels. Respectively, the aircraft inflight network security design must ensure the availability of correct information to the passengers.

6.3. Evaluation Iteration 2—STS Modelling and Feedback Discussion

From our initial analyses, we highlighted that STS provides no support to describe separation of concerns. In this experiment, we investigate the integration of SABSA layered approach to STS modelling in order to improve the separation of concerns.

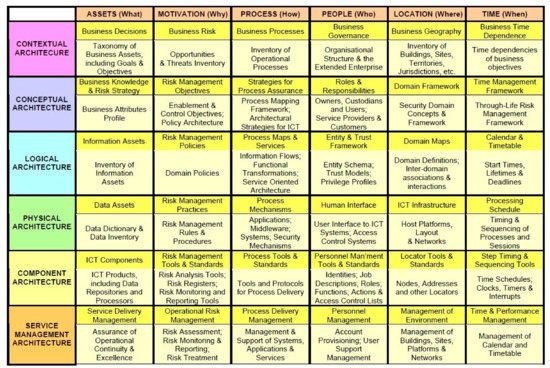

SABSA [9] (Sherwood Applied Business Security Architecture) is a methodology framework for enterprise security architecture and service management. The main intention of this framework is to guide security architects in their task. It defines a six-layered architecture model; each layer reflecting the respective stakeholder view in the process (Figure 10). The Business view and Architect’s view together correspond to the strategy and planning phases of the system engineering process. The Business view deals with the elicitation of high-level security objectives and constraints that are important to do business. It is essential to analyze the context of the business before building a secure system. This view facilitates the specification of the business security needs (e.g., reputation), operational goals and risk impacts (e.g., monetary loss) that drive the necessity of a secure system. The Architect’s view concerns the integration of protection objectives (e.g., application security services, network security services, data security services, etc.) that are necessary to secure the business security needs. The Designer’s view and builder’s view together, correspond to the designing phases of the system security engineering process. The Designer’s view deals with the specification of the security services (e.g., network entity authentication, data integrity protection, etc.) that are necessary to satisfy the control objectives. The builder’s view deals with the mapping of the technical security mechanisms (e.g., firewalls, hashing, etc.) to the logical security services. Finally, tradesman view (LV5) corresponds to the final implementation phase of the system security engineering process. The latest view called operational manager’s view corresponds to the maintenance management of the system security engineering process after the deployment.

Figure 10.

The SABSA layers.

SABSA is not strictly a security requirement engineering approach. This method provides a broad picture to understand the conventional security requirements engineering process starting from the perspective of the business system security architecture. The SABSA also includes a matrix that describes a wide variety of aspects that a modeler should be able to express (Cf. Figure 11) with the help of six interrogative questionnaires (what/why/how/who/where/when). This matrix guides the security architect in asking the right questions at the right time. Thus, it structures the security engineering process.

Figure 11.

The SABSA matrix (https://sabsa.org/—@2019 The SABSA Institute C.I.C).

In SABSA, network security requirement analysis (e.g., related to security zoning) starts from the designer’s view (i.e., LV3). Since we demonstrated in the first iteration of evaluation that STS does not support to derive network security zoning; therefore, we confine this second experiment to the first two views of SABSA only (i.e., Business view and Architect’s view). This implied that any discussion related to network security requirement analysis has been purposefully discarded. This strict confinement to the high-level abstraction improved the elicitation activity by provoking a long discussion. Indeed, this strict confinement to the SABSA abstraction has helped the team in focusing more on ‘WHAT’ perspectives of security needs rather than ‘HOW’ perspective of security needs. During this experimentation, we observed that the elicitation part of the scenario seemed clear and provoked a useful discussion.

Initially, the description of this scenario fits in just few lines. However, during the process of SRE modelling, the provoked discussion has developed the scenario details which resulted in an STS social model. In particular, new agents were introduced that were not mentioned during the textual description of the scenario. In addition, we observed that the goals of the maintainer agent were refined and improved as well. However, the second business need related to the passenger’s entertainment system remained unchanged.

The overall feedback of the STS notation from the two iterations confirms that STS modelling is interesting and easy to adapt. The overall experiment lasted 2 hours, which proves that STS modelling concepts can be learnt quickly (RM2.1.3). However, the STS modelling requires the users to know the agents and their respective initial goals before beginning the process. Our experiment shows that it is not the case because information on agents as well as their goals is evolving gradually during the elicitation process.

Although STS modelling concepts are interesting and easy to adapt, it does not help to trace the gradual growth of the social model, i.e., where to begin or how agents are introduced in the model. In addition, considering the traceability or risk analysis aspects, STS provides less support while compared to Secure KAOS (see Table 6). Indeed, the first two layers of SABSA modelling emphasize on risk analysis and risk control objectives. Therefore, STS modelling language is an interesting choice to apply together with the SABSA layering views. However, it requires some enhancements in terms of integrating risk analysis concepts and traceability attributes.

7. Conclusions