Smart Prediction of Rockburst Risks Using Microseismic Data and K-Nearest Neighbor Classification

Abstract

1. Introduction

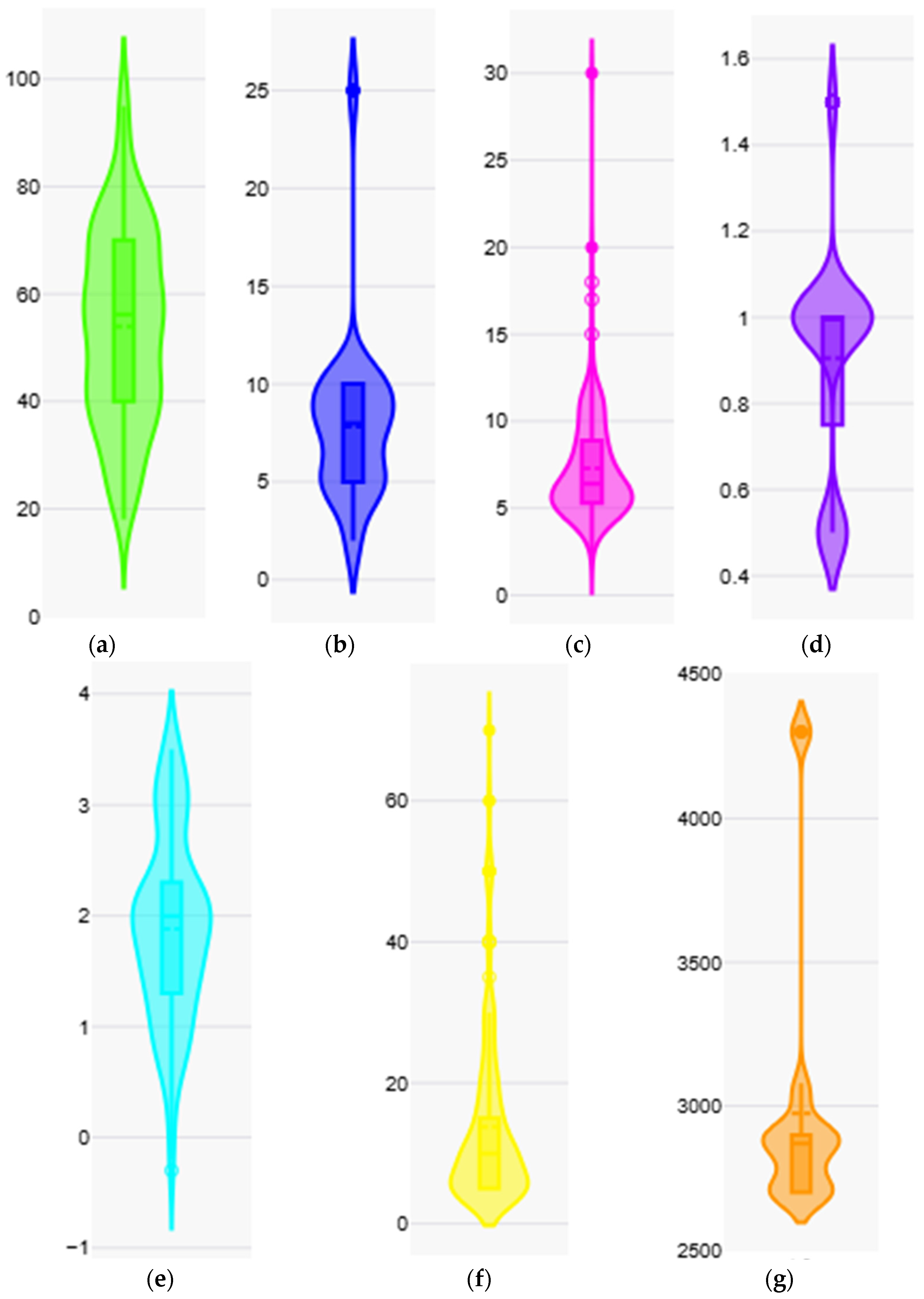

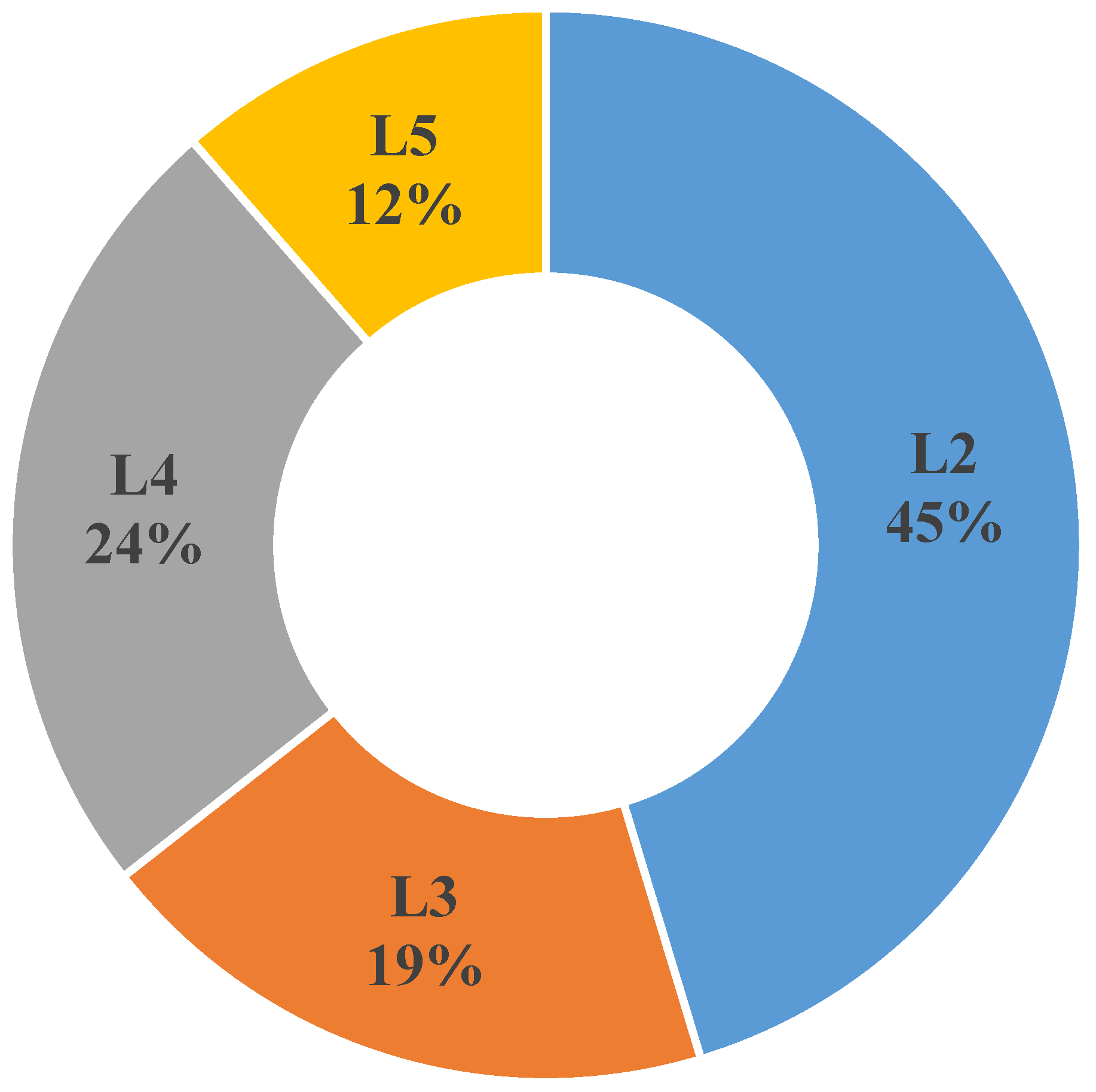

2. Data Collection and Analytics

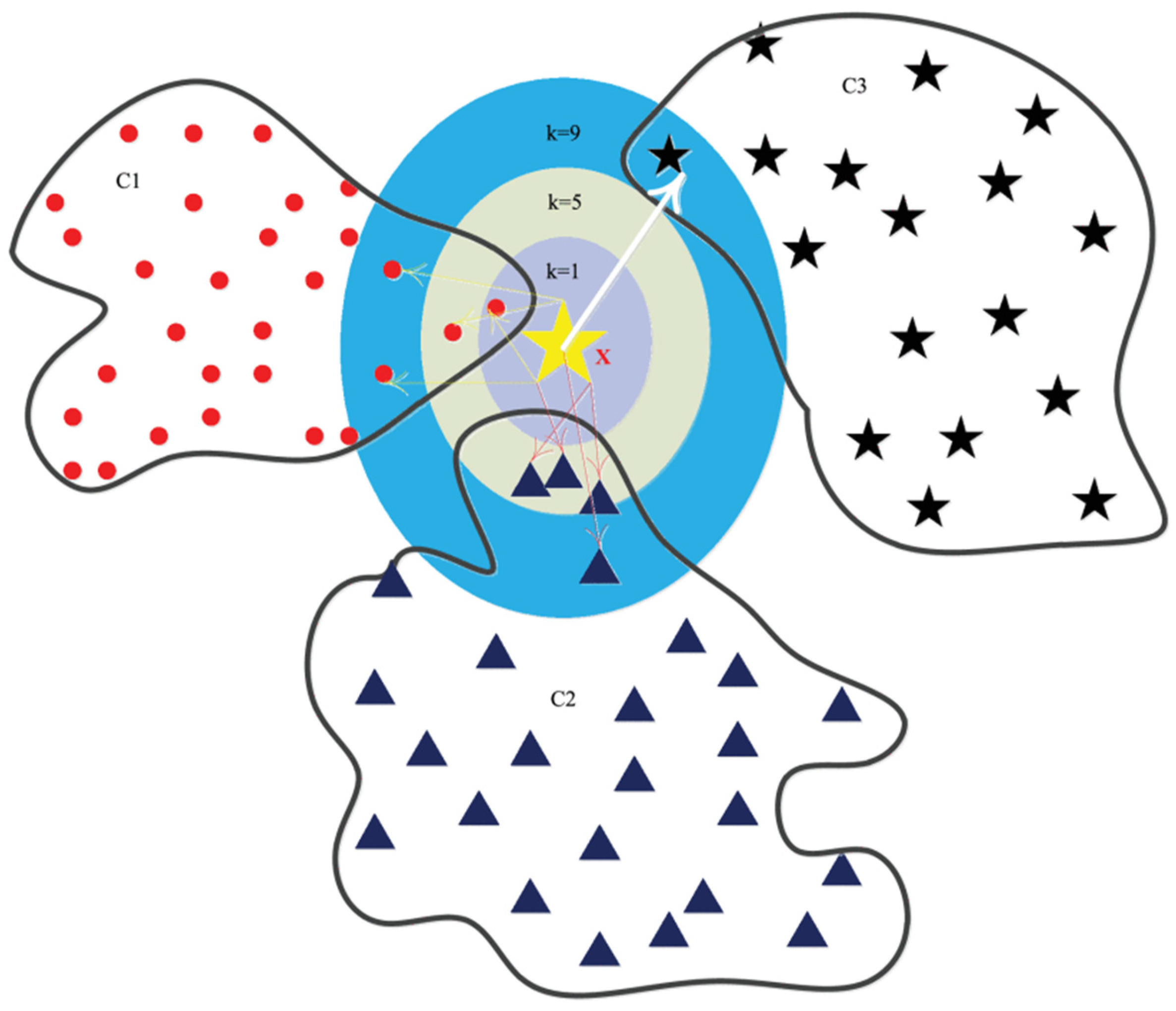

3. K-Nearest Neighbor (KNN)

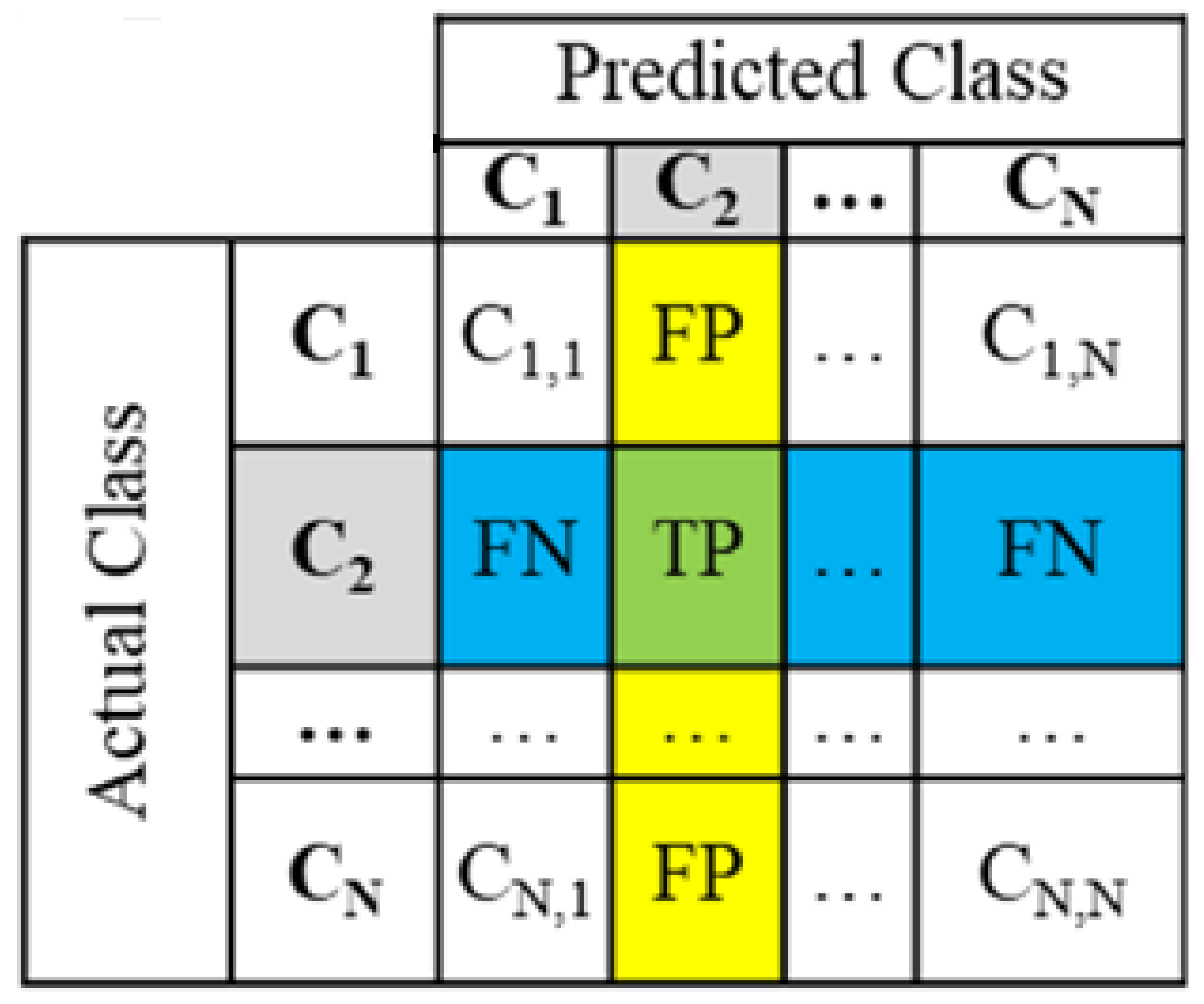

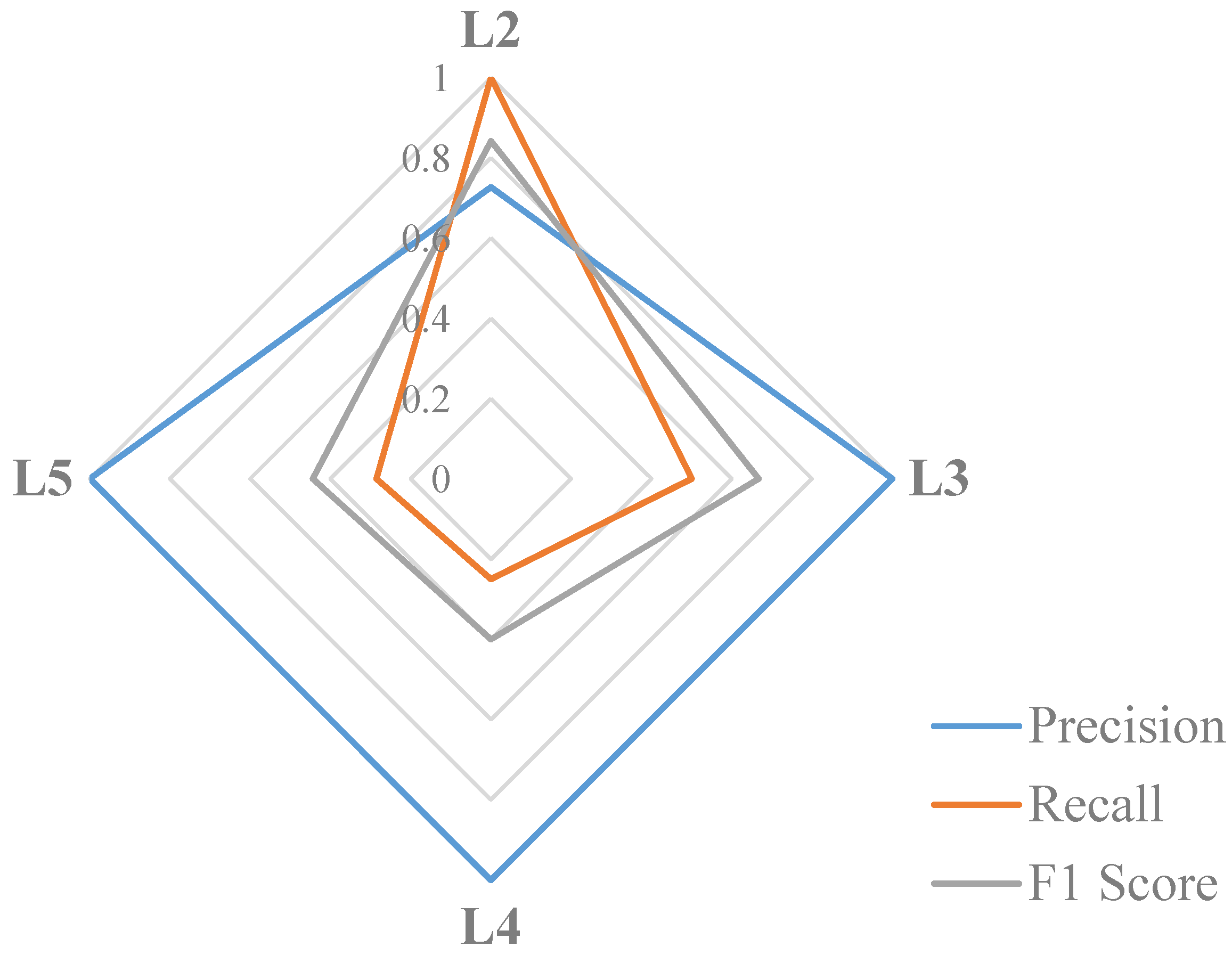

4. Performance Evaluation

5. Results and Discussion

6. Engineering Application

7. Conclusions and Future Prospect

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| S. No. | I1 | I2 | I3 (m) | I4 | I5 | I6 (m) | I8 (kg/m3) | Level |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 60 | 5 | 4.2 | 0.5 | 1.7 | 20 | 2700 | 4 |

| 2 | 60 | 8 | 4.2 | 0.5 | 1.7 | 25 | 2700 | 2 |

| 3 | 80 | 8 | 6 | 0.5 | 1.8 | 10 | 2700 | 4 |

| 4 | 80 | 5 | 6.2 | 1 | −0.3 | 5 | 2700 | 4 |

| 5 | 70 | 8 | 4 | 1 | 1.8 | 15 | 2700 | 2 |

| 6 | 40 | 5 | 3.8 | 1 | 0.4 | 5 | 2700 | 2 |

| 7 | 80 | 8 | 5.9 | 1 | 0.6 | 5 | 2700 | 2 |

| 8 | 90 | 8 | 6.8 | 1 | 0 | 5 | 2700 | 4 |

| 9 | 80 | 8 | 7 | 1 | 0 | 10 | 2700 | 2 |

| 10 | 80 | 8 | 7 | 1 | 2 | 5 | 2700 | 4 |

| 11 | 80 | 8 | 4.1 | 1 | 2 | 10 | 2700 | 4 |

| 12 | 70 | 8 | 9.5 | 1 | 2.2 | 5 | 2700 | 4 |

| 13 | 75 | 8 | 3.8 | 1 | 2.2 | 10 | 2700 | 3 |

| 14 | 75 | 8 | 4 | 1 | 2.2 | 10 | 2700 | 4 |

| 15 | 60 | 8 | 6.2 | 1 | 1.6 | 5 | 2700 | 2 |

| 16 | 60 | 10 | 10.5 | 0.5 | 1.6 | 5 | 2700 | 2 |

| 17 | 65 | 8 | 4.3 | 1 | 0.3 | 5 | 2700 | 2 |

| 18 | 60 | 5 | 5.6 | 0.5 | 1.5 | 5 | 2700 | 4 |

| 19 | 45 | 10 | 9.1 | 0.5 | 1.8 | 5 | 2700 | 5 |

| 20 | 43 | 5 | 9.3 | 0.5 | 1.8 | 5 | 2700 | 4 |

| 21 | 43 | 10 | 9.3 | 1 | 1.8 | 5 | 2700 | 2 |

| 22 | 43 | 10 | 9.4 | 0.5 | −0.2 | 5 | 2700 | 2 |

| 23 | 54 | 8 | 3.5 | 0.5 | 1.3 | 5 | 2700 | 2 |

| 24 | 45 | 8 | 3.6 | 1 | 1.3 | 10 | 2700 | 2 |

| 25 | 80 | 8 | 5.4 | 1 | 1.3 | 10 | 2700 | 2 |

| 26 | 50 | 8 | 7.8 | 1 | 1.3 | 15 | 2700 | 2 |

| 27 | 50 | 5 | 6.2 | 1 | 1 | 5 | 2700 | 3 |

| 28 | 50 | 5 | 5.1 | 0.5 | 1.2 | 5 | 2700 | 4 |

| 29 | 50 | 5 | 5.1 | 1 | 1.2 | 5 | 2700 | 2 |

| 30 | 50 | 8 | 8.3 | 1 | 0.7 | 5 | 2700 | 2 |

| 31 | 50 | 8 | 5.5 | 1 | 0.7 | 5 | 2700 | 2 |

| 32 | 60 | 10 | 8.8 | 1 | 2 | 5 | 2700 | 2 |

| 33 | 60 | 5 | 6.2 | 1 | 2 | 5 | 2700 | 2 |

| 34 | 60 | 5 | 5.2 | 1 | 2 | 5 | 2700 | 2 |

| 35 | 60 | 5 | 8.4 | 1 | 2 | 5 | 2700 | 2 |

| 36 | 60 | 5 | 6 | 1 | 2 | 5 | 2700 | 2 |

| 37 | 60 | 10 | 8.4 | 1 | 2 | 5 | 2700 | 2 |

| 38 | 60 | 5 | 5.3 | 1 | 2 | 5 | 2700 | 2 |

| 39 | 60 | 10 | 7 | 1 | 2 | 5 | 2700 | 2 |

| 40 | 60 | 10 | 5.4 | 0.5 | 2 | 5 | 2700 | 4 |

| 41 | 75 | 5 | 5.1 | 1 | 0.6 | 15 | 2700 | 3 |

| 42 | 70 | 5 | 5.1 | 1 | 0.6 | 10 | 2700 | 2 |

| 43 | 70 | 5 | 5.1 | 1 | 0.6 | 5 | 2700 | 3 |

| 44 | 75 | 5 | 5.2 | 1 | 1.3 | 10 | 2700 | 2 |

| 45 | 75 | 5 | 6.7 | 1 | 1.3 | 15 | 2700 | 2 |

| 46 | 75 | 5 | 5.1 | 1 | 1.3 | 20 | 2700 | 2 |

| 47 | 75 | 8 | 7 | 1 | 1.8 | 5 | 2700 | 3 |

| 48 | 75 | 8 | 5 | 1 | 1.8 | 10 | 2700 | 2 |

| 49 | 75 | 5 | 5.3 | 1 | 1.8 | 5 | 2700 | 3 |

| 50 | 35 | 2 | 5.3 | 1 | 3.1 | 15 | 2700 | 5 |

| 51 | 35 | 2 | 10.6 | 1 | 3.1 | 15 | 2700 | 5 |

| 52 | 35 | 10 | 10.6 | 1 | 3.1 | 20 | 2700 | 2 |

| 53 | 35 | 5 | 5.9 | 1.5 | 3.1 | 25 | 2700 | 4 |

| 54 | 35 | 2 | 10.6 | 1.5 | 3.1 | 25 | 2700 | 4 |

| 55 | 35 | 5 | 11.8 | 1.5 | 3.1 | 20 | 2700 | 2 |

| 56 | 35 | 5 | 10.6 | 0.5 | 3.1 | 25 | 2700 | 3 |

| 57 | 35 | 8 | 7.6 | 0.5 | 3.1 | 15 | 2700 | 4 |

| 58 | 41.7 | 5 | 7.6 | 1.5 | 3.1 | 15 | 2700 | 2 |

| 59 | 41.7 | 2 | 7 | 1 | 3.1 | 10 | 2700 | 4 |

| 60 | 35 | 10 | 10.6 | 0.5 | 3.1 | 15 | 2700 | 2 |

| 61 | 35 | 5 | 7 | 1 | 3.1 | 15 | 2700 | 4 |

| 62 | 40 | 2 | 14 | 1 | 2.8 | 15 | 2900 | 5 |

| 63 | 39 | 2 | 7 | 1 | 2.8 | 10 | 2900 | 4 |

| 64 | 39 | 2 | 6.5 | 1 | 2.8 | 50 | 2900 | 4 |

| 65 | 40 | 2 | 5.7 | 1 | 1.6 | 25 | 2900 | 3 |

| 66 | 42.86 | 2 | 6.4 | 1.5 | 1.6 | 20 | 2900 | 3 |

| 67 | 35.1 | 2 | 6.8 | 1.5 | 3.5 | 50 | 2900 | 2 |

| 68 | 38 | 10 | 9 | 0.5 | 3.5 | 10 | 2900 | 5 |

| 69 | 32.3 | 2 | 4.5 | 1.5 | 3.5 | 35 | 2900 | 3 |

| 70 | 43.7 | 8 | 7.7 | 0.5 | 3.5 | 20 | 2900 | 3 |

| 71 | 43.7 | 10 | 7 | 0.5 | 3.5 | 20 | 2900 | 3 |

| 72 | 43.7 | 2 | 4.2 | 1 | 3.5 | 15 | 2900 | 4 |

| 73 | 42.8 | 2 | 5 | 0.5 | 3.5 | 30 | 2900 | 5 |

| 74 | 42.8 | 10 | 10 | 0.5 | 3.5 | 30 | 2900 | 3 |

| 75 | 39.5 | 5 | 5 | 0.5 | 3.5 | 10 | 2900 | 4 |

| 76 | 44.4 | 10 | 15 | 1 | 3.5 | 15 | 2900 | 4 |

| 77 | 47.3 | 8 | 8.3 | 1 | 3.5 | 50 | 2900 | 3 |

| 78 | 47.3 | 8 | 5.5 | 1 | 3.5 | 50 | 2900 | 3 |

| 79 | 51.43 | 5 | 9.3 | 1.5 | 1.9 | 10 | 2900 | 3 |

| 80 | 39.4 | 5 | 9.5 | 1.5 | 2.1 | 15 | 2900 | 2 |

| 81 | 39.4 | 2 | 4.5 | 1 | 2.1 | 20 | 2900 | 3 |

| 82 | 39.4 | 10 | 11 | 1 | 2.1 | 25 | 2900 | 2 |

| 83 | 41.7 | 2 | 4.5 | 0.5 | 2.1 | 60 | 2900 | 3 |

| 84 | 40.8 | 10 | 10 | 0.5 | 2.1 | 30 | 2900 | 3 |

| 85 | 40.8 | 5 | 8 | 0.5 | 2.1 | 25 | 2900 | 3 |

| 86 | 44.1 | 5 | 18 | 1 | 2.1 | 50 | 2900 | 2 |

| 87 | 36 | 8 | 14 | 1 | 1.2 | 10 | 2900 | 2 |

| 88 | 36 | 8 | 6.5 | 0.5 | 1.2 | 15 | 2900 | 2 |

| 89 | 37.7 | 8 | 5.2 | 1 | 0.4 | 5 | 2900 | 3 |

| 90 | 40.8 | 8 | 4.2 | 1 | 1.8 | 5 | 2900 | 2 |

| 91 | 30 | 10 | 5.3 | 0.5 | 1.2 | 5 | 2800 | 3 |

| 92 | 30 | 8 | 5.4 | 0.5 | 1.2 | 5 | 2800 | 2 |

| 93 | 30 | 10 | 5.3 | 1 | 1.2 | 10 | 2800 | 2 |

| 94 | 30 | 10 | 5.2 | 1 | 1.2 | 10 | 2800 | 3 |

| 95 | 74 | 8 | 5.9 | 0.5 | 1.5 | 5 | 2800 | 5 |

| 96 | 74 | 8 | 5.3 | 1 | 1.5 | 10 | 2800 | 3 |

| 97 | 74 | 8 | 5.9 | 1 | 1.5 | 10 | 2800 | 2 |

| 98 | 74 | 8 | 6.5 | 1 | 1.5 | 20 | 2800 | 2 |

| 99 | 74 | 8 | 6.5 | 0.5 | 1.5 | 15 | 2800 | 4 |

| 100 | 71 | 8 | 8 | 1 | 0.9 | 5 | 2800 | 4 |

| 101 | 71 | 8 | 5.3 | 1 | 0.9 | 10 | 2800 | 2 |

| 102 | 71 | 10 | 8 | 1 | 0.9 | 10 | 2800 | 2 |

| 103 | 71 | 8 | 5.6 | 1 | 0.9 | 10 | 2800 | 2 |

| 104 | 71 | 10 | 20 | 0.5 | 2.1 | 5 | 2800 | 5 |

| 105 | 40 | 8 | 5.9 | 0.5 | 2.1 | 5 | 2700 | 4 |

| 106 | 40 | 8 | 5.3 | 0.5 | 2.1 | 5 | 2700 | 2 |

| 107 | 40 | 8 | 5.9 | 1 | 2.1 | 5 | 2700 | 2 |

| 108 | 40 | 8 | 6.5 | 1 | 2.1 | 10 | 2700 | 2 |

| 109 | 40 | 2 | 5.6 | 1 | 2.1 | 10 | 2700 | 4 |

| 110 | 40 | 2 | 5.8 | 1 | 2.1 | 5 | 2700 | 4 |

| 111 | 40 | 8 | 5.5 | 1 | 2.1 | 20 | 2700 | 2 |

| 112 | 70 | 5 | 8 | 1 | 0.8 | 5 | 2800 | 4 |

| 113 | 70 | 10 | 8 | 1 | 0.8 | 10 | 2800 | 2 |

| 114 | 70 | 10 | 5.5 | 1 | 0.8 | 10 | 2800 | 2 |

| 115 | 70 | 5 | 8 | 1 | 0.8 | 10 | 2800 | 4 |

| 116 | 70 | 8 | 5.1 | 1 | 0.8 | 10 | 2800 | 3 |

| 117 | 70 | 5 | 5.1 | 1 | 0.8 | 5 | 2800 | 2 |

| 118 | 70 | 5 | 5.1 | 1 | 0.8 | 10 | 2800 | 2 |

| 119 | 54 | 5 | 5.7 | 1 | 0.8 | 20 | 2700 | 2 |

| 120 | 54 | 10 | 9.1 | 0.5 | 0.8 | 25 | 2700 | 2 |

| 121 | 39 | 8 | 5.7 | 1 | 0.8 | 30 | 2800 | 2 |

| 122 | 84 | 5 | 7.7 | 1 | 2.9 | 10 | 2900 | 5 |

| 123 | 45 | 5 | 4.8 | 1 | 2.9 | 50 | 2900 | 2 |

| 124 | 84 | 10 | 7.4 | 1 | 2.9 | 50 | 2900 | 3 |

| 125 | 45 | 10 | 6.9 | 1 | 2.9 | 10 | 2900 | 2 |

| 126 | 45 | 5 | 7.4 | 1 | 2.9 | 10 | 2900 | 4 |

| 127 | 56 | 5 | 4.6 | 1 | 2.9 | 25 | 2900 | 2 |

| 128 | 18 | 5 | 5.8 | 0.5 | 0.4 | 10 | 3030 | 4 |

| 129 | 24 | 5 | 8.6 | 0.5 | 0.4 | 10 | 3030 | 3 |

| 130 | 95 | 10 | 6.9 | 1 | 1.5 | 5 | 2900 | 2 |

| 131 | 95 | 5 | 6.6 | 1 | 0.9 | 5 | 2900 | 5 |

| 132 | 45 | 10 | 5.1 | 1 | 1.6 | 5 | 2900 | 2 |

| 133 | 21 | 5 | 11.2 | 1.5 | 0.9 | 5 | 3030 | 2 |

| 134 | 21 | 5 | 6.1 | 1.5 | 0.9 | 5 | 3030 | 2 |

| 135 | 95 | 10 | 8 | 1 | 1.6 | 5 | 2900 | 5 |

| 136 | 39 | 10 | 5.3 | 1 | 1.6 | 15 | 2900 | 3 |

| 137 | 21 | 5 | 5.5 | 1 | 1.9 | 20 | 3030 | 3 |

| 138 | 24 | 5 | 8.7 | 0.5 | 1.5 | 10 | 3030 | 5 |

| 139 | 24 | 5 | 11 | 1 | 1.5 | 15 | 3030 | 2 |

| 140 | 67 | 10 | 5 | 1 | −0.2 | 5 | 2900 | 2 |

| 141 | 21 | 5 | 9 | 0.5 | 1.8 | 10 | 3030 | 4 |

| 142 | 21 | 10 | 9 | 1 | 1.8 | 10 | 3030 | 2 |

| 143 | 95 | 10 | 6.8 | 1 | 1 | 5 | 2900 | 4 |

| 144 | 73 | 25 | 6.8 | 1 | 1 | 5 | 2900 | 3 |

| 145 | 27 | 5 | 11.5 | 1 | 3.1 | 30 | 3030 | 4 |

| 146 | 27 | 5 | 7.6 | 1 | 3.1 | 40 | 3030 | 4 |

| 147 | 35 | 5 | 11.5 | 1 | 3.1 | 30 | 3030 | 4 |

| 148 | 50 | 25 | 4.5 | 1 | 3.1 | 40 | 2900 | 2 |

| 149 | 95 | 25 | 7.1 | 1 | 3.1 | 20 | 2900 | 2 |

| 150 | 73 | 25 | 4.7 | 1 | 3.1 | 30 | 2900 | 2 |

| 151 | 95 | 25 | 6.3 | 1 | 3.1 | 30 | 2900 | 2 |

| 152 | 73 | 25 | 4.4 | 1 | 3.1 | 40 | 2900 | 2 |

| 153 | 73 | 25 | 9.6 | 1 | 3.1 | 50 | 2900 | 2 |

| 154 | 54 | 25 | 4.8 | 1 | 3.1 | 60 | 2900 | 2 |

| 155 | 34 | 5 | 4.5 | 1 | 3.1 | 70 | 2900 | 3 |

| 156 | 25 | 10 | 11.6 | 0.5 | 1.4 | 5 | 3030 | 4 |

| 157 | 25 | 5 | 11.6 | 0.5 | 1.4 | 5 | 3030 | 4 |

| 158 | 24 | 5 | 12 | 1 | 2 | 5 | 3030 | 5 |

| 159 | 39 | 5 | 9 | 1 | 2 | 5 | 2900 | 4 |

| 160 | 25 | 5 | 5.1 | 1 | 1.3 | 5 | 3080 | 4 |

| 161 | 25 | 5 | 10.5 | 1 | 1.3 | 10 | 3080 | 3 |

| 162 | 25 | 5 | 7.8 | 1 | 1.3 | 10 | 3080 | 2 |

| 163 | 25.97 | 10 | 17 | 0.5 | 2 | 5 | 3080 | 5 |

| 164 | 25.97 | 8 | 6.2 | 0.5 | 2 | 10 | 3080 | 3 |

| 165 | 25.97 | 8 | 5.7 | 0.5 | 2 | 5 | 3080 | 4 |

| 166 | 25.97 | 5 | 5.4 | 1 | 2 | 10 | 3080 | 3 |

| 167 | 25.97 | 8 | 5.3 | 1 | 2 | 10 | 3080 | 2 |

| 168 | 25.97 | 8 | 5.6 | 0.5 | 2 | 5 | 3080 | 4 |

| 169 | 75 | 5 | 5.2 | 1 | 1.6 | 10 | 2800 | 5 |

| 170 | 75 | 5 | 5 | 1 | 1.6 | 5 | 2800 | 5 |

| 171 | 65 | 5 | 2 | 1 | 1.6 | 5 | 2800 | 2 |

| 172 | 50 | 5 | 9.1 | 1 | 1.4 | 5 | 2800 | 3 |

| 173 | 50 | 5 | 4.6 | 0.5 | 1.9 | 30 | 2800 | 3 |

| 174 | 70 | 8 | 5 | 0.5 | 1.6 | 5 | 4300 | 4 |

| 175 | 70 | 8 | 8 | 1 | 2 | 5 | 4300 | 4 |

| 176 | 70 | 8 | 6 | 0.5 | 2 | 5 | 4300 | 4 |

| 177 | 70 | 8 | 12 | 1 | 2 | 10 | 4300 | 3 |

| 178 | 67 | 10 | 11 | 0.5 | 2.5 | 15 | 4300 | 5 |

| 179 | 67 | 25 | 5 | 1 | 2.5 | 15 | 4300 | 2 |

| 180 | 67 | 5 | 5 | 1 | 2.5 | 15 | 4300 | 2 |

| 181 | 76 | 10 | 6 | 0.5 | 2.7 | 5 | 4300 | 5 |

| 182 | 40 | 10 | 9.2 | 0.5 | 1.1 | 5 | 4300 | 3 |

| 183 | 40 | 5 | 4.8 | 1 | 1.1 | 10 | 4300 | 2 |

| 184 | 40 | 10 | 11.7 | 0.5 | 2.5 | 5 | 4300 | 5 |

| 185 | 50 | 10 | 9 | 1 | 2.7 | 20 | 4300 | 4 |

| 186 | 50 | 5 | 6 | 1 | 2.1 | 5 | 4300 | 4 |

| 187 | 55 | 5 | 8 | 1 | 1.9 | 5 | 4300 | 5 |

| 188 | 55 | 5 | 6 | 1 | 2.3 | 5 | 4300 | 4 |

| 189 | 65 | 10 | 11 | 1 | 2.3 | 10 | 4300 | 4 |

| 190 | 55 | 5 | 6 | 0.5 | 0.9 | 5 | 4300 | 4 |

| 191 | 60 | 5 | 5.5 | 1 | 2.2 | 20 | 4300 | 4 |

| 192 | 50 | 5 | 5.5 | 0.5 | 1.4 | 5 | 4300 | 5 |

| 193 | 50 | 10 | 8.5 | 0.5 | 1.4 | 20 | 4300 | 2 |

| 194 | 50 | 10 | 5.5 | 0.5 | 1.4 | 40 | 4300 | 2 |

| 195 | 50 | 5 | 6 | 1 | 1.5 | 5 | 4300 | 3 |

| 196 | 50 | 10 | 30 | 1 | 1.7 | 5 | 4300 | 5 |

| 197 | 70 | 5 | 4.4 | 1.5 | 1.7 | 20 | 2700 | 2 |

| 198 | 70 | 10 | 4.6 | 0.5 | 2 | 5 | 2800 | 4 |

| 199 | 90 | 10 | 4.5 | 1.5 | 2 | 10 | 2850 | 2 |

| 200 | 70 | 5 | 5.2 | 1 | 2.1 | 5 | 2700 | 5 |

| 201 | 56.2 | 8 | 10 | 1 | 1 | 5 | 2870 | 4 |

| 202 | 56.2 | 10 | 10 | 1 | 1 | 10 | 2870 | 2 |

| 203 | 56.2 | 8 | 6 | 1 | 1 | 20 | 2870 | 2 |

| 204 | 57.8 | 8 | 6.1 | 1 | 1 | 5 | 2870 | 3 |

| 205 | 57.8 | 8 | 6.1 | 1.5 | 1 | 10 | 2870 | 3 |

| 206 | 57.8 | 8 | 6.5 | 1 | 1.5 | 5 | 2870 | 4 |

| 207 | 57.8 | 10 | 11.3 | 1 | 1.5 | 10 | 2870 | 2 |

| 208 | 57.8 | 10 | 6.5 | 1 | 1.5 | 10 | 2870 | 2 |

| 209 | 57 | 8 | 6.7 | 1 | 2.2 | 5 | 2870 | 4 |

| 210 | 57 | 10 | 9.5 | 1 | 2.2 | 5 | 2870 | 4 |

| 211 | 57 | 10 | 11.2 | 1 | 2.2 | 10 | 2870 | 2 |

| 212 | 57 | 8 | 6.4 | 1 | 2.2 | 25 | 2870 | 2 |

| 213 | 57 | 8 | 6.5 | 1 | 2.2 | 10 | 2870 | 2 |

| 214 | 57 | 10 | 11.5 | 0.5 | 1.7 | 5 | 2870 | 4 |

| 215 | 57 | 10 | 11 | 1 | 1.7 | 5 | 2870 | 2 |

| 216 | 57 | 10 | 11 | 1 | 1.7 | 10 | 2870 | 2 |

| 217 | 57 | 10 | 11.5 | 1 | 1.7 | 10 | 2870 | 2 |

| 218 | 57 | 10 | 7.4 | 1 | 1.7 | 15 | 2870 | 2 |

| 219 | 57.8 | 10 | 6.4 | 0.5 | 2.5 | 5 | 2870 | 5 |

| 220 | 57.8 | 10 | 11.2 | 0.5 | 2.5 | 5 | 2870 | 5 |

| 221 | 57.8 | 10 | 6.4 | 1 | 2.5 | 10 | 2870 | 2 |

| 222 | 57.8 | 10 | 10.6 | 1 | 2.5 | 10 | 2870 | 2 |

| 223 | 58.6 | 10 | 12.4 | 0.5 | 2.2 | 30 | 2870 | 2 |

| 224 | 58.6 | 10 | 5.9 | 1 | 2.2 | 30 | 2870 | 2 |

| 225 | 58.6 | 10 | 6.1 | 1 | 2.2 | 30 | 2870 | 2 |

| 226 | 59.3 | 8 | 8 | 1 | 2.2 | 5 | 2870 | 5 |

| 227 | 59.3 | 8 | 5.4 | 1 | 2.2 | 15 | 2870 | 3 |

| 228 | 59.3 | 8 | 10 | 1 | 2.2 | 10 | 2870 | 2 |

| 229 | 59.3 | 8 | 8 | 1 | 2.2 | 15 | 2870 | 3 |

| 230 | 59.3 | 8 | 8.4 | 1 | 2.2 | 15 | 2870 | 2 |

| 231 | 59.3 | 8 | 5 | 1 | 2.2 | 20 | 2870 | 2 |

| 232 | 70.3 | 10 | 6.9 | 0.5 | 2.3 | 5 | 2900 | 5 |

| 233 | 70.3 | 10 | 11 | 1 | 2.3 | 10 | 2900 | 2 |

| 234 | 70.3 | 10 | 5.5 | 1 | 2.3 | 15 | 2900 | 3 |

| 235 | 70.3 | 10 | 5.4 | 1 | 2.3 | 15 | 2900 | 2 |

| 236 | 72.2 | 8 | 4 | 1 | 1.6 | 5 | 2900 | 3 |

References

- Ortlepp, W.; Stacey, T. Rockburst mechanisms in tunnels and shafts. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 1994, 9, 59–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dou, L.; Chen, T.; Gong, S.; He, H.; Zhang, S. Rockburst hazard determination by using computed tomography technology in deep workface. Saf. Sci. 2012, 50, 736–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, M. Principles of rock support in burst-prone ground. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2013, 36, 46–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Shayea, N. Failure of Rock Anchors along the Road Cut Slopes of Dhila Decent Road, Saudi Arabia. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Problematic Soils (GEOPROB 2005), Famagusta, Cyprus, 25–27 May 2005; Eastern Mediterian University: Famagusta, Cyprus, 2005; Volume 3, pp. 1129–1136. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Shayea, N.A. Pullout Failure of Rock Anchor Rods at Slope Cuts, Dhila Decent Road, Saudi Arabia. In Proceedings of the 17th International Road Federation (IRF) World Meeting and Exhibition, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, 10–14 November 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser, P.; McCreath, D.R.; Tannant, D.D. Canadian Rockburst Research Program 1990–1995; Camiro Mining Division: Sudbury, ON, Canada, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad, M.; Tang, X.-W.; Qiu, J.-N.; Ahmad, F.; Gu, W.-J. Application of machine learning algorithms for the evaluation of seismic soil liquefaction potential. Front. Struct. Civ. Eng. 2021, 15, 490–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, M.; Amjad, M.; Al-Mansob, R.A.; Kamiński, P.; Olczak, P.; Khan, B.J.; Alguno, A.C. Prediction of liquefaction-induced lateral displacements using Gaussian process regression. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 1977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, F.; Tang, X.-W.; Qiu, J.-N.; Wróblewski, P.; Ahmad, M.; Jamil, I. Prediction of slope stability using Tree Augmented Naive-Bayes classifier: Modeling and performance evaluation. Math. Biosci. Eng. 2022, 19, 4526–4546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, F.; Tang, X.-W.; Ahmad, M.; González-Lezcano, R.A.; Majdi, A.; Arbili, M.M. Stability risk assessment of slopes using logistic model tree based on updated case histories. Math. Biosci. Eng. 2023, 20, 21229–21245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmad, M.; Al Zubi, M.; Almujibah, H.; Sabri, M.M.S.; Mustafvi, J.B.; Haq, S.; Ouahbi, T.; Alzlfawi, A. Improved prediction of soil shear strength using machine learning algorithms: Interpretability analysis using SHapley Additive exPlanations. Front. Earth Sci. 2025, 13, 1542291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, M.; Al-Mansob, R.A.; Ramli, A.B.B.; Ahmad, F.; Khan, B.J. Unconfined compressive strength prediction of stabilized expansive clay soil using machine learning techniques. Multiscale Multidiscip. Model. Exp. Des. 2024, 7, 217–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Zubi, M.A.; Ahmad, M.; Abdullah, S.; Khan, B.J.; Qamar, W.; Abdullah, G.M.S.; González-Lezcano, R.A.; Paul, S.; El-Gawaad, N.S.A.; Ouahbi, T. Long short term memory networks for predicting resilient Modulus of stabilized base material subject to wet-dry cycles. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 27928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, F.; Tang, X.; Ahmad, M. Predicting Rainfall-Induced Failure Potential of Highway Slopes: Taking Route T-18 in Taiwan as Case of Illustration. In Proceedings of the 1st International Conference of Climate Change and Emerging Trends in Civil Engineering, Topi, Pakistan, 12–13 February 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad, F.; Tang, X.; Hu, J.; Ahmad, M.; Gordan, B. Improved Prediction of Slope Stability under Static and Dynamic Conditions Using Tree-Based Models. CMES—Comput. Model. Eng. Sci. 2023, 1, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamran, M.; Ullah, B.; Ahmad, M.; Sabri, M.M.S. Application of KNN-based isometric mapping and fuzzy c-means algorithm to predict short-term rockburst risk in deep underground projects. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 1023890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmad, M.; Alsulami, B.T.; Hakamy, A.H.; Majdi, A.; Alqurashi, M.; Sabri, M. The Performance Comparison of the Decision Tree Models on the Prediction of Seismic Gravelly Soil Liquefaction Potential Based on Dynamic Penetration Test. Front. Earth Sci. 2023, 11, 1105610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, M.; Al-Zubi, M.A.; Kubińska-Jabcoń, E.; Majdi, A.; Al-Mansob, R.A.; Sabri, M.M.S.; Ali, E.; Naji, J.A.; Elnaggar, A.Y.; Zamin, B. Predicting California bearing ratio of HARHA-treated expansive soils using Gaussian process regression. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 13593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong-Bo, Z. Classification of rockburst using support vector machine. Rock Soil Mech. 2005, 26, 642–644. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, D.; Feng, X.; Yang, C.; Chen, B.; Qiu, S.; Xu, D. Neural network estimation of rockburst damage severity based on engineering cases. In Proceedings of the ISRM SINOROCK 2013 (the 3rd ISRM Symposium on Rock Mechanics), Shanghai, China, 18–20 June 2013; pp. 457–463. [Google Scholar]

- Gong, F.; Li, X. A distance discriminant analysis method for prediction of possibility and classification of rockburst and its application. Chin. J. Rock Mech. Eng. 2007, 26, 1012–1018. [Google Scholar]

- Gong, F.; Li, X.; Zhang, W. Rockburst prediction of underground engineering based on Bayes discriminant analysis method. Rock Soil Mech. 2010, 31, 370–377. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, J.; Shi, X.-Z.; Dong, L.; Hu, H.-Y.; Wang, H.-Y. Fisher discriminant analysis model and its application for prediction of classification of rockburst in deep-buried long tunnel. J. Coal Sci. Eng. (China) 2010, 16, 144–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Li, X.; Shi, X. Long-term prediction model of rockburst in underground openings using heuristic algorithms and support vector machines. Saf. Sci. 2012, 50, 629–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adoko, A.C.; Gokceoglu, C.; Wu, L.; Zuo, Q.J. Knowledge-based and data-driven fuzzy modeling for rockburst prediction. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 2013, 61, 86–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Shao, J.; Xu, W.; Meng, Y. Prediction of rock burst classification using the technique of cloud models with attribution weight. Nat. Hazards 2013, 68, 549–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, Q.; Feng, X. Classification and prediction of rockburst using AdaBoost combination learning method. Rock Soil Mech.-Wuhan 2008, 29, 943. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, L.-J.; Li, X.-B.; Kang, P. Prediction of rockburst classification using Random Forest. Trans. Nonferrous Met. Soc. China 2013, 23, 472–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Chen, B. Data-Driven Model for Rockburst Prediction. Math. Probl. Eng. 2020, 2020, 5735496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javadi, A.A.; Ahangar-Asr, A.; Johari, A.; Faramarzi, A.; Toll, D. Modelling stress–strain and volume change behaviour of unsaturated soils using an evolutionary based data mining technique, an incremental approach. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2012, 25, 926–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heal, D. Observations and Analysis of Incidences of Rockburst Damage in Underground Mines. Ph.D. Thesis, The University of Western Australia, Perth, Australia, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, J.; Shi, X.-Z.; Huang, R.-D.; Qiu, X.-Y.; Chen, C. Feasibility of stochastic gradient boosting approach for predicting rockburst damage in burst-prone mines. Trans. Nonferrous Met. Soc. China 2016, 26, 1938–1945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; Zare Naghadehi, M.Z.; Jimenez, R. Evaluating short-term rock burst damage in underground mines using a systems approach. Int. J. Min. Reclam. Environ. 2020, 34, 531–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbulut, Y.; Sengur, A.; Guo, Y.; Smarandache, F. NS-k-NN: Neutrosophic set-based k-nearest neighbors classifier. Symmetry 2017, 9, 179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, C.; Huang, J.; Mansaray, L.R.; Li, Z.; Liu, W.; Han, J. Estimation and mapping of winter oilseed rape LAI from high spatial resolution satellite data based on a hybrid method. Remote Sens. 2017, 9, 488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- France, S.L.; Carroll, J.D.; Xiong, H. Distance metrics for high dimensional nearest neighborhood recovery: Compression and normalization. Inf. Sci. 2012, 184, 92–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yesilbudak, M.; Sagiroglu, S.; Colak, I. A new approach to very short term wind speed prediction using k-nearest neighbor classification. Energy Convers. Manag. 2013, 69, 77–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Da, Q.; Liang, W.; Xiao, P.; Dai, B.; Zhao, G. Bagged ensemble of gaussian process classifiers for assessing rockburst damage potential with an imbalanced dataset. Mathematics 2022, 10, 3382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Level | I1 | I2 | I3 (m) | I4 | I5 | I6 (m) | I8 (kg/m3) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4 | 60 | 5 | 4.2 | 0.5 | 1.7 | 20 | 2700 |

| 2 | 60 | 8 | 4.2 | 0.5 | 1.7 | 25 | 2700 |

| 4 | 80 | 8 | 6 | 0.5 | 1.8 | 10 | 2700 |

| … | … | … | … | … | … | … | … |

| 3 | 70.3 | 10 | 5.5 | 1 | 2.3 | 15 | 2900 |

| 2 | 70.3 | 10 | 5.4 | 1 | 2.3 | 15 | 2900 |

| 3 | 72.2 | 8 | 4 | 1 | 1.6 | 5 | 2900 |

| Mean | 53.90 | 7.83 | 7.30 | 0.90 | 1.88 | 13.73 | 2974.53 |

| Standard Deviation | 17.80 | 4.20 | 3.06 | 0.26 | 0.83 | 12.08 | 449.61 |

| Sample Variance | 316.86 | 17.66 | 9.34 | 0.07 | 0.69 | 145.82 | 202,146.59 |

| Kurtosis | −0.64 | 8.28 | 13.64 | 0.08 | −0.30 | 4.50 | 4.59 |

| Skewness | 0.10 | 2.38 | 2.64 | −0.19 | 0.01 | 2.06 | 2.45 |

| Minimum | 18 | 2 | 2 | 0.5 | −0.3 | 5 | 2700 |

| Maximum | 95 | 25 | 30 | 1.5 | 3.5 | 70 | 4300 |

| Count | 236 | 236 | 236 | 236 | 236 | 236 | 236 |

| Metric | Formula |

|---|---|

| Accuracy (%) | |

| Recall of Class Ci | |

| Precision of Class Ci | |

| F1 Score of Class Ci |

| Actual | Actual/Predicted | Predicted | |||||||||

| Training Phase | Testing Phase | ||||||||||

| L2 | L3 | L4 | L5 | Total | L2 | L3 | L4 | L5 | Total | ||

| L2 | 172 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 173 | 32 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 32 | |

| L3 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | |

| L4 | 6 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 7 | 6 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 8 | |

| L5 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 7 | |

| Total | 184 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 187 | 44 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 49 | |

| Accuracy | F1 Score | Confusion Matrix | Model | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 48.98% | [0.6667, 0.4211, 0.3478, 0.1818] | Bagged ensemble of GPCs without data preprocessing | [38] | |

| 61.22% | [0.7407, 0.5333, 0.6, 0] | Bagged ensemble of GPCs without under-sampling | ||

| 57.14% | [0.7170, 0.4, 0.5714, 0] | GPC without under-sampling | ||

| 63.27% | [0.7907, 0.6, 0.5455, 0.3077] | Bagged Ensemble of Gaussian Process Classifiers | ||

| 61.22% | - | - | Stochastic gradient boosting approach | [32] |

| 75.5% | [0.842, 0.667, 0.400, 0.444] | KNN | Proposed method |

| Microseismic Event | I1 | I2 | I3 | I4 | I5 | I6 | I8 | Actual | Results Using Heal’s Method [31] | Results Using GPC [38] | Proposed Method |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 58 | 5 | 12 | 0.5 | 1.6 | 14 | 2700 | L2 | L5 | L2 | L2 |

| 58 | 5 | 12 | 0.5 | 1.6 | 22 | 2700 | L2 | L5 | L2 | L2 | |

| 47 | 8 | 6 | 0.5 | 1.6 | 29 | 2700 | L2 | L2 | L2 | L2 | |

| 2 | 47 | 8 | 10 | 0.5 | 1.8 | 10 | 2700 | L3 | L4 | L2 | L2 |

| 47 | 8 | 6.6 | 0.5 | 1.8 | 10 | 2700 | L2 | L2 | L4 | L2 | |

| 47 | 5 | 5.9 | 0.5 | 1.8 | 16 | 2700 | L3 | L3 | L4 | L4 | |

| 3 | 48 | 10 | 4.8 | 0.5 | 1.5 | 10 | 2700 | L2 | L2 | L2 | L2 |

| 48 | 10 | 10 | 1 | 1.5 | 10 | 2700 | L2 | L2 | L2 | L2 | |

| 4 | 39 | 5 | 5 | 1 | 1.8 | 13 | 2700 | L2 | L1 | L2 | L2 |

| 43 | 8 | 5 | 1 | 1.8 | 13 | 2700 | L2 | L1 | L2 | L2 | |

| 5 | 58 | 8 | 12 | 0.5 | 1.6 | 10 | 2700 | L2 | L5 | L2 | L2 |

| 6 | 58 | 8 | 11 | 1 | 2.2 | 5 | 2700 | L4 | L3 | L2 | L3 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Ahmad, M.; Ullah, Z.; Hussan, S.; Alzlfawi, A.; Omar, R.C.; Haq, S.; Ahmad, F.; Khalil, M.N. Smart Prediction of Rockburst Risks Using Microseismic Data and K-Nearest Neighbor Classification. GeoHazards 2026, 7, 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/geohazards7010005

Ahmad M, Ullah Z, Hussan S, Alzlfawi A, Omar RC, Haq S, Ahmad F, Khalil MN. Smart Prediction of Rockburst Risks Using Microseismic Data and K-Nearest Neighbor Classification. GeoHazards. 2026; 7(1):5. https://doi.org/10.3390/geohazards7010005

Chicago/Turabian StyleAhmad, Mahmood, Zia Ullah, Sabahat Hussan, Abdullah Alzlfawi, Rohayu Che Omar, Shay Haq, Feezan Ahmad, and Muhammad Naveed Khalil. 2026. "Smart Prediction of Rockburst Risks Using Microseismic Data and K-Nearest Neighbor Classification" GeoHazards 7, no. 1: 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/geohazards7010005

APA StyleAhmad, M., Ullah, Z., Hussan, S., Alzlfawi, A., Omar, R. C., Haq, S., Ahmad, F., & Khalil, M. N. (2026). Smart Prediction of Rockburst Risks Using Microseismic Data and K-Nearest Neighbor Classification. GeoHazards, 7(1), 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/geohazards7010005