Soil Liquefaction in Sarangani Peninsula, Philippines Triggered by the 17 November 2023 Magnitude 6.8 Earthquake

Abstract

1. Introduction

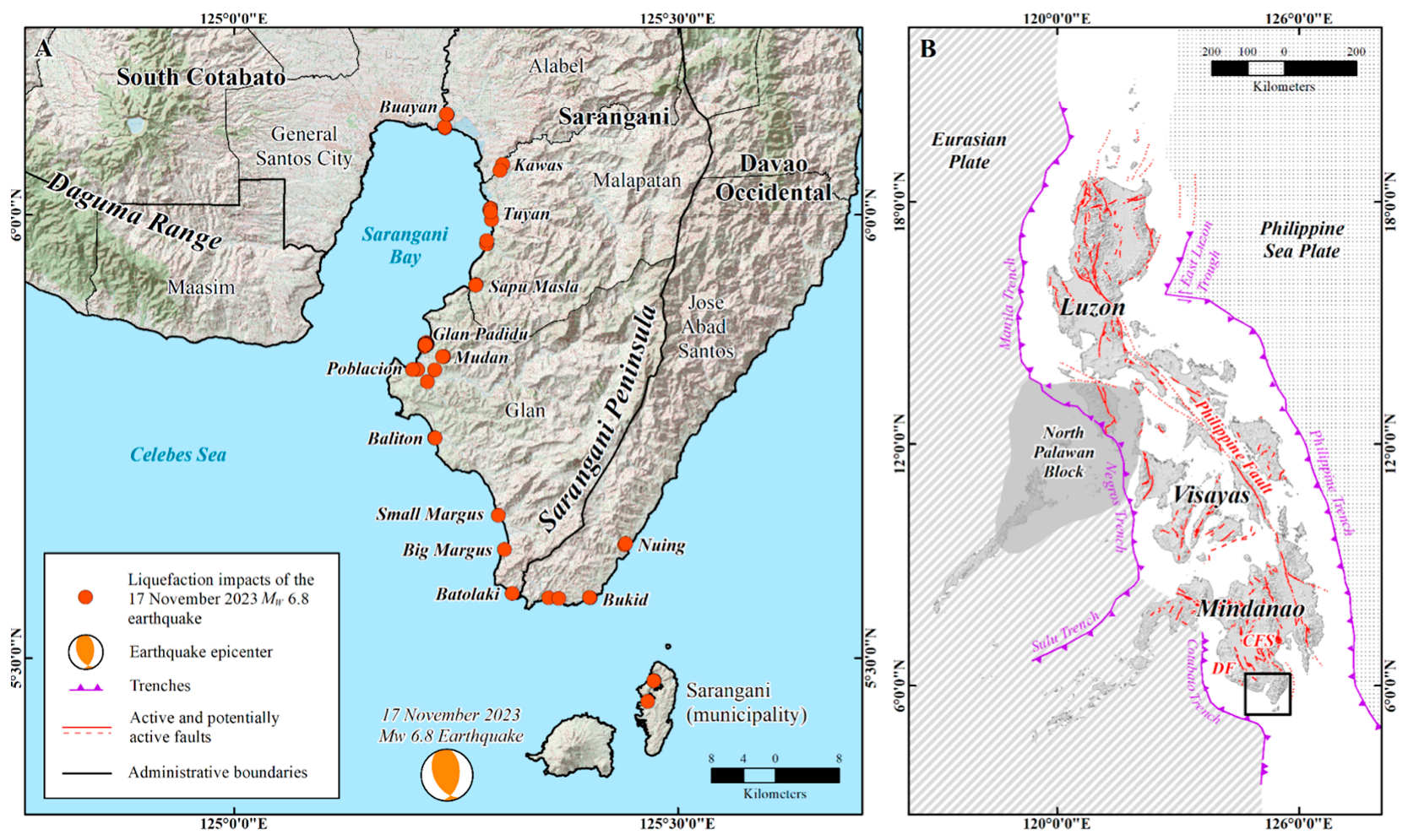

2. Tectonic Setting and Recent Seismicity

3. Methodology

4. Results and Discussion

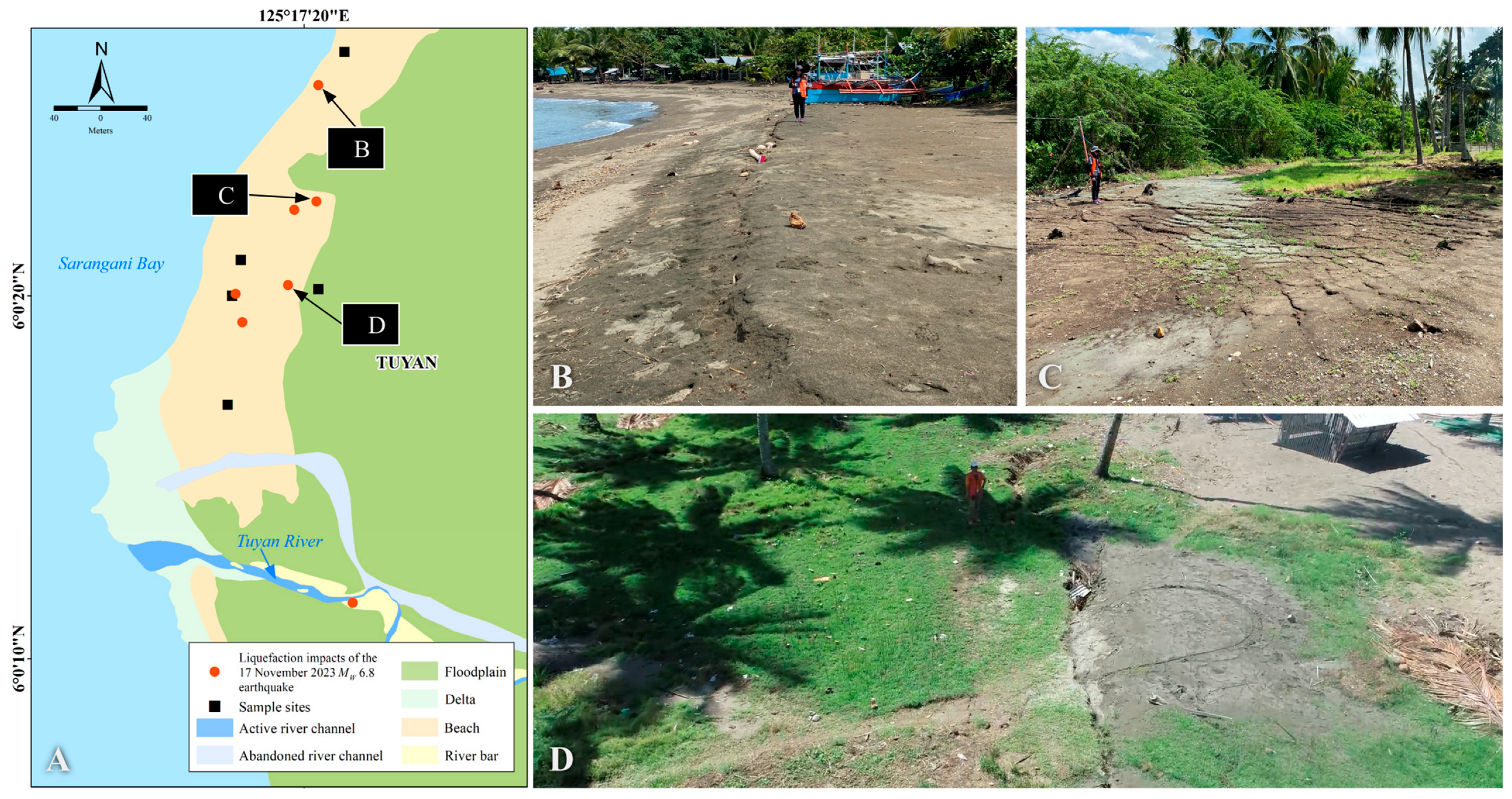

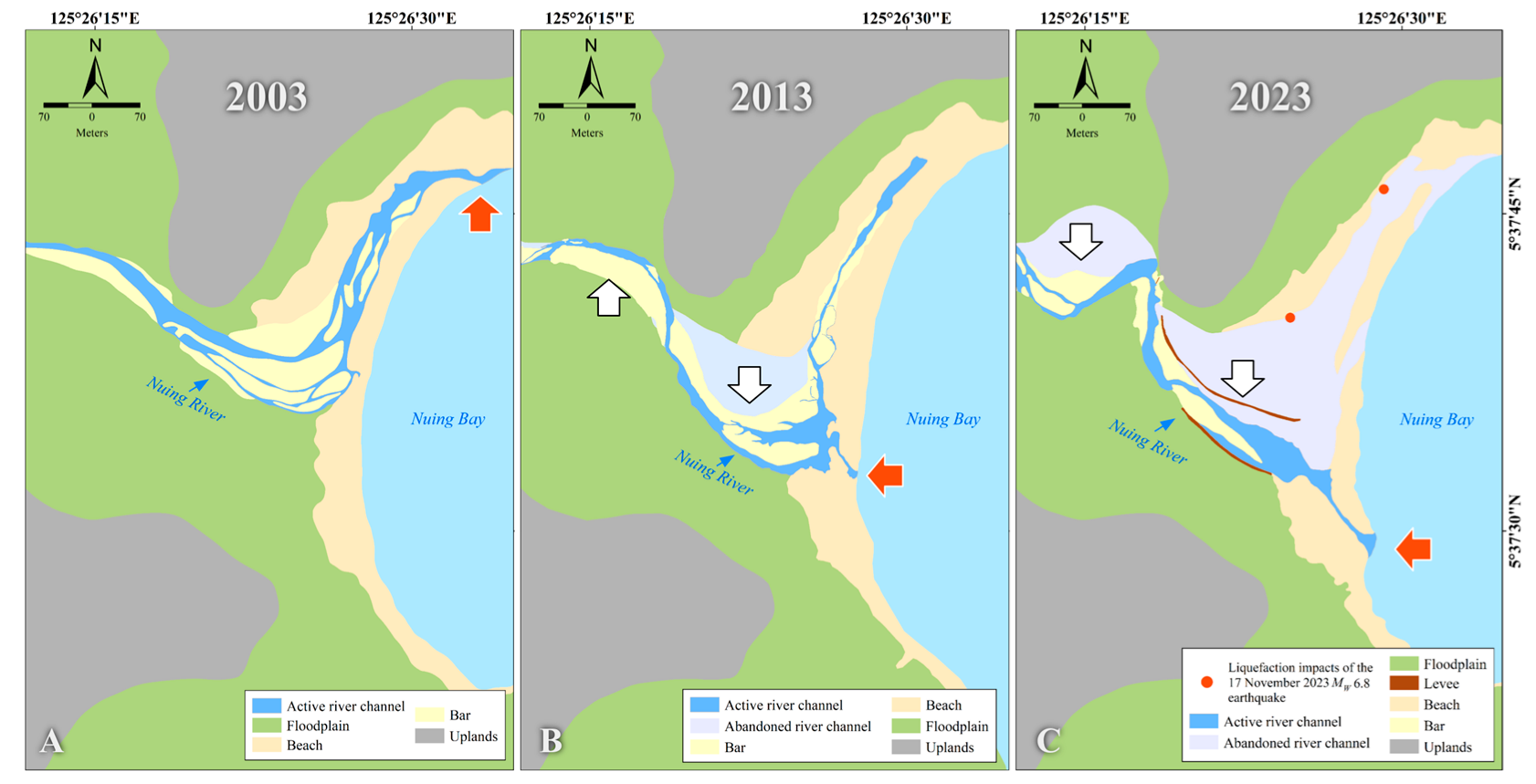

4.1. Distribution of Liquefaction Impacts

4.2. Comparison with Predictive Models

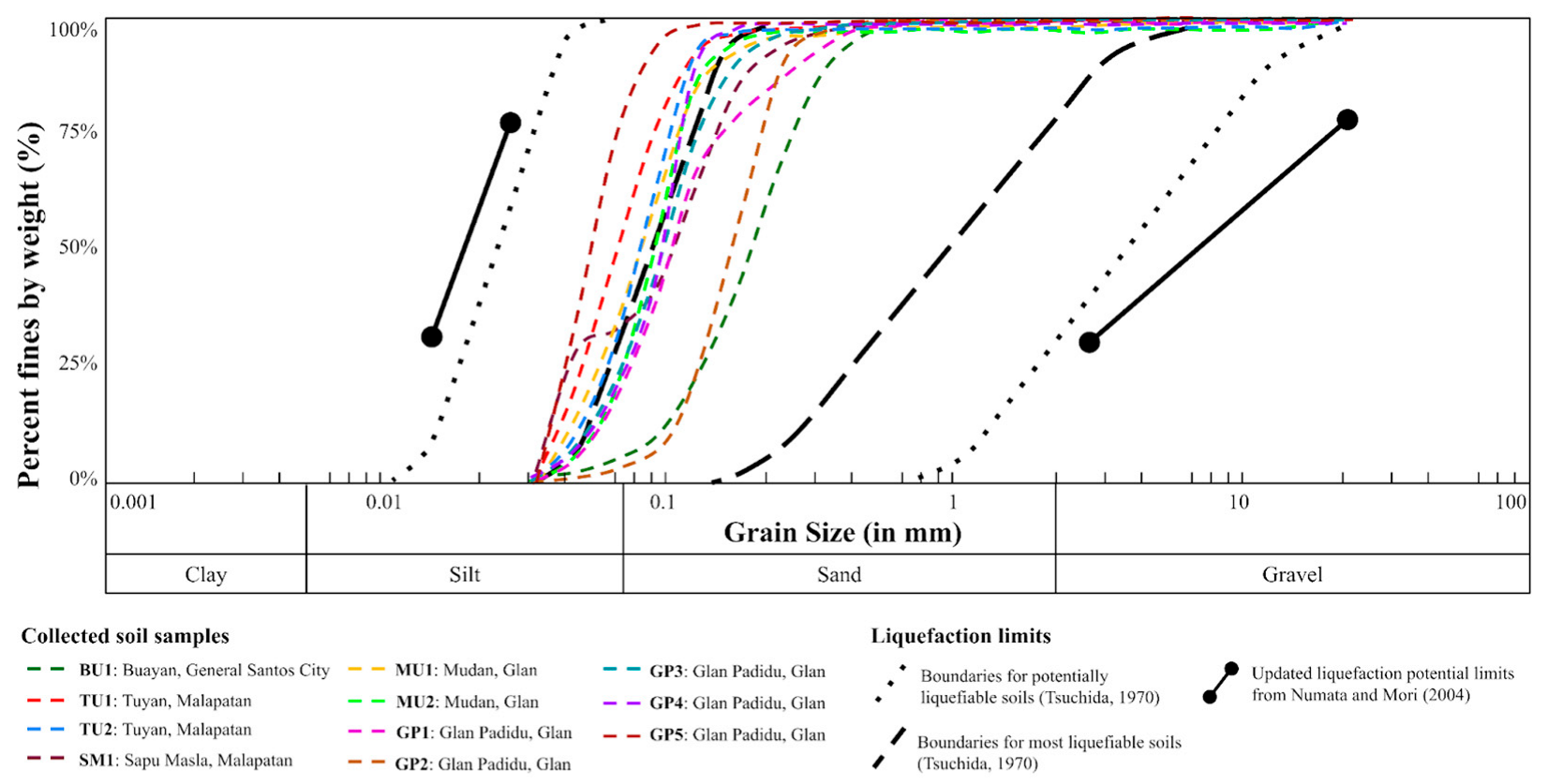

4.3. Analysis of Sediment Ejecta

4.4. Geophysical Analyses on Selected Sites

4.5. Limitations of This Study

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Province | Municipality/City | Barangay | Latitude | Longitude | Lique-Faction * | Geomorphic Unit | Soil Period (s) | Soil Thickness (m) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Davao Occidental | Jose Abad Santos | Balangonan | 5.568221 | 125.354800 | B1; C4 | Filled land | - | - |

| Davao Occidental | Jose Abad Santos | Balangonan | 5.567440 | 125.365900 | B1 | Beach | - | - |

| Davao Occidental | Jose Abad Santos | Bukid | 5.568286 | 125.400900 | B2 | Beach | 0.1027 | 3.7 |

| Davao Occidental | Jose Abad Santos | Bukid | 5.568123 | 125.401300 | A2 | Active river channel | 0.0745 | 2.9 |

| Davao Occidental | Jose Abad Santos | Bukid | 5.568393 | 125.400800 | A2; B1 | Marsh, swamp, and pond | 0.1296 | 4.5 |

| Davao Occidental | Jose Abad Santos | Nuing | 5.627803 | 125.440200 | A3 | Abandoned river channel | - | - |

| Davao Occidental | Jose Abad Santos | Nuing | 5.629489 | 125.441430 | C3 | Abandoned river channel | - | - |

| Davao Occidental | Sarangani | Camahual | 5.451015 | 125.466147 | B1 | Beach | - | - |

| Davao Occidental | Sarangani | Patuco | 5.474899 | 125.473243 | B3 | Filled land | - | - |

| Davao Occidental | Sarangani | Patuco | 5.474543 | 125.473453 | B3 | Filled land | - | - |

| Davao Occidental | Sarangani | Patuco | 5.474466 | 125.473199 | B3 | Filled land | - | - |

| Sarangani | Alabel | Kawas | 6.056900 | 125.302950 | A3; B1 | River bar | 0.0927 | 3.4 |

| Sarangani | Alabel | Kawas | 6.050000 | 125.300000 | B1 | River bar | 0.0902 | 3.3 |

| Sarangani | Alabel | Maribulan | 6.112795 | 125.240518 | B1 | River bar | - | - |

| Sarangani | Glan | Batolaki | 5.572943 | 125.313678 | A3 | Beach | 0.1691 | 5.5 |

| Sarangani | Glan | Baliton | 5.748330 | 125.226400 | A2 | Marsh, swamp, and pond | 0.8363 | 19.9 |

| Sarangani | Glan | Baliton | 5.747925 | 125.226430 | C5 | Marsh, swamp, and pond | 0.712 | 17.5 |

| Sarangani | Glan | Baliton | 5.748235 | 125.226600 | B1 | Marsh, swamp, and pond | 0.8363 | 19.9 |

| Sarangani | Glan | Big Margus | 5.622482 | 125.304700 | A3 | Beach | 0.1718 | 5.6 |

| Sarangani | Glan | Calabanit | 5.811672 | 125.218000 | B1; B3 | Alluvial plain | - | - |

| Sarangani | Glan | Glan Padidu | 5.852925 | 125.215575 | A2; B1 | Delta | 0.1432 | 4.8 |

| Sarangani | Glan | Glan Padidu | 5.852860 | 125.215560 | A2; B1 | Delta | 0.1432 | 4.8 |

| Sarangani | Glan | Glan Padidu | 5.852309 | 125.215024 | B2 | Delta | 0.1432 | 4.8 |

| Sarangani | Glan | Glan Padidu | 5.852105 | 125.215049 | A2 | Delta | 0.1432 | 4.8 |

| Sarangani | Glan | Glan Padidu | 5.851893 | 125.215078 | A3 | Delta | 0.1432 | 4.8 |

| Sarangani | Glan | Glan Padidu | 5.851262 | 125.215051 | A2 | Delta | 0.1432 | 4.8 |

| Sarangani | Glan | Glan Padidu | 5.853627 | 125.215422 | A2 | Delta | 0.1812 | 5.9 |

| Sarangani | Glan | Glan Padidu | 5.854508 | 125.215222 | B2 | Beach | 0.1618 | 5.3 |

| Sarangani | Glan | Glan Padidu | 5.855772 | 125.217036 | B1 | Delta | 0.1618 | 5.3 |

| Sarangani | Glan | Glan Padidu | 5.854038 | 125.217950 | B2 | River bar | 0.0667 | 2.6 |

| Sarangani | Glan | Glan Padidu | 5.854636 | 125.217229 | B1 | Floodplain | 0.1618 | 5.3 |

| Sarangani | Glan | Glan Padidu | 5.854279 | 125.216826 | A3; B2 | River bar | 0.0667 | 2.6 |

| Sarangani | Glan | Glan Padidu | 5.853677 | 125.216515 | A3; B2 | River bar | 0.0667 | 2.6 |

| Sarangani | Glan | Glan Padidu | 5.852530 | 125.215316 | B2 | Delta | 0.1432 | 4.8 |

| Sarangani | Glan | Glan Padidu | 5.853952 | 125.215870 | A3 | Delta | 0.1768 | 5.7 |

| Sarangani | Glan | Glan Padidu | 5.853522 | 125.215910 | A3; B2 | Delta | 0.1768 | 5.7 |

| Sarangani | Glan | Glan Padidu | 5.853708 | 125.215949 | A3 | Delta | 0.1768 | 5.7 |

| Sarangani | Glan | Glan Padidu | 5.853316 | 125.215418 | B2 | Delta | 0.1812 | 5.9 |

| Sarangani | Glan | Glan Padidu | 5.853330 | 125.215571 | A3: B2 | Delta | 0.1812 | 5.9 |

| Sarangani | Glan | Mudan | 5.840018 | 125.236300 | A3; B1; C5 | Floodplain | 0.0787 | 3.0 |

| Sarangani | Glan | Mudan | 5.840353 | 125.236268 | A1; B1 | Dry river bed | 0.0842 | 3.2 |

| Sarangani | Glan | Mudan | 5.840421 | 125.236141 | C5 | Floodplain | 0.1464 | 4.9 |

| Sarangani | Glan | Mudan | 5.839927 | 125.235117 | C5 | Floodplain | 0.1464 | 4.9 |

| Sarangani | Glan | Poblacion | 5.825780 | 125.206562 | A3, B1 | Marsh, swamp, and pond | 0.4103 | 11.3 |

| Sarangani | Glan | Poblacion | 5.825462 | 125.206933 | A3; B1; C2 | Marsh, swamp, and pond | 0.4103 | 11.3 |

| Sarangani | Glan | Poblacion | 5.825556 | 125.201111 | C4 | Filled land | 0.4103 | 11.3 |

| Sarangani | Glan | Small Margus | 5.661071 | 125.297878 | A3 | Beach | 0.2603 | 7.8 |

| Sarangani | Glan | Tapon | 5.825184 | 125.226459 | B2; C4 | River bar | - | - |

| Sarangani | Malapatan | Poblacion | 5.967178 | 125.284844 | A1; B1 | Floodplain | - | - |

| Sarangani | Malapatan | Poblacion | 5.967020 | 125.284750 | A2; B1 | Floodplain | - | - |

| Sarangani | Malapatan | Poblacion | 5.970710 | 125.284950 | B2; B3; C4 | Filled land | - | - |

| Sarangani | Malapatan | Sapu Masla | 5.920390 | 125.272530 | A2; B1 | Filled land | 0.9639 | 22.3 |

| Sarangani | Malapatan | Sapu Masla | 5.921480 | 125.272920 | A3 | Filled land | 0.8363 | 19.9 |

| Sarangani | Malapatan | Sapu Masla | 5.921490 | 125.272680 | A3; B1 | Filled land | 0.8363 | 19.9 |

| Sarangani | Malapatan | Sapu Masla | 5.920400 | 125.272530 | B1 | Filled land | 0.9639 | 22.3 |

| Sarangani | Malapatan | Tuyan | 5.994500 | 125.290500 | B1 | Beach | 0.2822 | 8.3 |

| Sarangani | Malapatan | Tuyan | 6.007170 | 125.289000 | B2 | Beach | 0.4108 | 11.3 |

| Sarangani | Malapatan | Tuyan | 6.006279 | 125.288985 | A3; B2 | Beach | 0.2576 | 7.8 |

| Sarangani | Malapatan | Tuyan | 6.005638 | 125.288766 | A3; B1 | Beach | 0.2576 | 7.9 |

| Sarangani | Malapatan | Tuyan | 6.005570 | 125.288361 | A3; B2 | Beach | 0.3184 | 9.2 |

| Sarangani | Malapatan | Tuyan | 6.005353 | 125.288413 | A3 | Beach | 0.2822 | 8.3 |

| Sarangani | Malapatan | Tuyan | 6.006214 | 125.288814 | A3 | Beach | 0.2822 | 8.3 |

| Sarangani | Malapatan | Tuyan | 6.003204 | 125.289265 | A3 | River bar | 0.2822 | 8.3 |

| South Cotabato | General Santos City | Buayan | 6.113530 | 125.239810 | B3 | Active river channel | 0.9478 | 22.0 |

| South Cotabato | General Santos City | Buayan | 6.097920 | 125.237850 | A3; B1 | Delta | 0.9967 | 22.1 |

| South Cotabato | General Santos City | Buayan | 6.098250 | 125.237970 | B1 | Delta | 1.0282 | 23.5 |

| South Cotabato | General Santos City | Buayan | 6.098080 | 125.237770 | B5 | Delta | 0.9967 | 22.9 |

| South Cotabato | General Santos City | Buayan | 6.099160 | 125.237340 | A2; B1 | Floodplain | 6.0982 | 125.2 |

| South Cotabato | General Santos City | Buayan | 6.113530 | 125.239810 | B2 | River bar | 6.0982 | 125.2 |

References

- Department of Science and Technology—Philippine Institute of Volcanology and Seismology (DOST-PHIVOLCS). Earthquake Information No. 4; Department of Science and Technology—Philippine Institute of Volcanology and Seismology (DOST-PHIVOLCS): Quezon City, Philippines, 2023. Available online: https://earthquake.phivolcs.dost.gov.ph/2023_Earthquake_Information/November/2023_1117_0814_B4F.html (accessed on 24 November 2025).

- Department of Science and Technology—Philippine Institute of Volcanology and Seismology (DOST-PHIVOLCS). Distribution of Active Faults and Trenches in the Philippines. 2023. Available online: https://gisweb.phivolcs.dost.gov.ph/gisweb/storage/hazard-maps/national/earthquake/ground-rupture-(active-fault)/aft_2023_000000000_02.png (accessed on 24 November 2025).

- National Mapping and Resource Information Authority (NAMRIA). 1:50,000-Scale Digital Topographic Map of Mindanao; National Mapping and Resource Information Authority (NAMRIA): Taguig, Philippines, 2013.

- Philippine Statistics Authority (PSA). Philippines—Subnational Administrative Boundaries; Philippine Statistics Authority (PSA): Quezon, Philippines, 2016.

- Buhay, D.J.L.; Legaspi, C.J.M.; Perez, J.S.; Lagunsad, K.D.B.; Halasan, O.P.C.; Vidal, H.A.L.; Sochayseng, K.S.; Magnaye, A.A.T.; Dizon, R.P.A.; Reyes, M.J.V.; et al. Mapping and Characterization of the Liquefaction Impacts of the July and October 2022 Earthquakes in Northwestern Luzon, Philippines. Eng. Geol. 2024, 342, 107759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albano, M.K.; Chiaradonna, A.; Saroli, M.; Moro, M.; Pepe, A.; Solaro, G. InSAR Analysis of Post-Liquefaction Consolidation Subsidence after 2012 Emilia Earthquake Sequence (Italy). Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 2364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akin, M.K.; Kramer, S.L.; Topal, T. Empirical Correlations of Shear Wave Velocity (Vs) and Penetration Resistance (SPT-N) for Different Soils in an Earthquake-Prone Area (Erbaa-Turkey). Eng. Geol. 2011, 119, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Numata, A.; Mori, S. Limits in the Gradation Curves of Liquefiable Soils. In Proceedings of the 13th World Conference on Earthquake Engineering, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 1–6 August 2004. Paper No. 1190. [Google Scholar]

- Aurelio, M.A.; Peña, R.E.; Taguibao, K.J.L. Sculpting the Philippine Archipelago since the Cretaceous through Rifting, Oceanic Spreading, Subduction, Obduction, Collision and Strike-Slip Faulting: Contribution to IGMA5000. J. Asian Earth Sci. 2012, 72, 102–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bautista, B.C.; Bautista, M.L.; Oike, K.; Wu, F.; Punongbayan, R.S. A New Insight on the Geometry of Subducting Slabs in Northern Luzon, Philippines. Tectonophysics 2001, 339, 279–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pubellier, M.; Quebral, R.; Aurelio, M.; Rangin, C. Docking and Post-Docking Escape Tectonics in the Southern Philippines. Geol. Soc. Lond. Spec. Publ. 1996, 106, 511–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohrlach, B.D.; Loucks, R.R. Multimillion-Year Cyclic Ramp-up of Volatiles in a Lower Crustal Magma Reservoir Trapped below the Tampakan Copper-Gold Deposit by Mio-Pliocene Crustal Compression in the Southern Philippines. In Super Porphyry Copper & Gold Deposits—A Global Perspective; PCG Publishing: Adelaide, SA, Australia, 2005; Volume 2, pp. 369–407. [Google Scholar]

- Middleton, C.; Buenavista, A.; Rohrlach, B.; Gonzalez, J.; Subang, L.; Moreno, G. A Geological Review of the Tampakan Copper-Gold Deposit, Southern Mindanao, Philippines. In Proceedings of the PACRIM 2004 Congress, Adelaide, SA, Australia, 19–22 September 2004; Volume 22. [Google Scholar]

- Quebral, R.D.; Pubellier, M.; Rangin, C. The Onset of Movement on the Philippine Fault in Eastern Mindanao: A Transition from a Collision to a Strike-Slip Environment. Tectonics 1996, 15, 713–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sajona, F.G.; Bellon, H.; Maury, R.C.; Pubellier, M.; Quebral, R.D.; Cotten, J.; Bayon, F.E.; Pagado, E.; Pamatian, P. Tertiary and Quaternary Magmatism in Mindanao and Leyte (Philippines): Geochronology, Geochemistry and Tectonic Setting. J. Asian Earth Sci. 1997, 15, 121–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mines and Geosciences Bureau (MGB). Geology of the Philippines; Mines and Geosciences Bureau (MGB): Quezon City, Philippines, 2010.

- Pubellier, M.; Deffontaines, B.; Quebral, R.; Rangin, C. Drainage Network Analysis and Tectonics of Mindanao, Southern Philippines. Geomorphology 1994, 9, 325–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Department of Science and Technology—Philippine Institute of Volcanology and Seismology (DOST-PHIVOLCS). Insights on the 17 November 2023 Mw 6.8 Offshore Davao Occidental Earthquake; Department of Science and Technology—Philippine Institute of Volcanology and Seismology (DOST-PHIVOLCS): Quezon City, Philippines, 2023. Available online: https://reliefweb.int/report/philippines/insights-17-november-2023-mw-68-offshore-davao-occidental-earthquake (accessed on 24 November 2025).

- Garcia, L.C.; Valenzuela, R.G.; Arnold, E.P.; Macalingcag, T.G.; Ambubuyog, G.F.; Lance, N.T.; Cordeta, J.D.; Doniego, A.G.; Cordeta, J.D.G.M.; Dabi, A.C.; et al. Southeast Asia Association of Seismology and Earthquake Engineering (SEASEE); Series on Seismology (Philippines); Government Printing Office: Washington, DC, USA, 1985; Volume 4.

- Department of Science and Technology—Philippine Institute of Volcanology and Seismology (DOST-PHIVOLCS). Palimbang Earthquake—06 March 2002; Department of Science and Technology—Philippine Institute of Volcanology and Seismology (DOST-PHIVOLCS): Quezon City, Philippines, 2002. Available online: https://www.phivolcs.dost.gov.ph/2002-march-06-ms6-8-palimbang-earthquake/ (accessed on 24 November 2025).

- National Disaster Risk Reduction and Management Council (NDRRMC). SitRep No. 04: Magnitude 7.2 Earthquake in Sarangani, Davao Occidental; National Disaster Risk Reduction and Management Council (NDRRMC): Quezon City, Philippines, 2017. Available online: https://reliefweb.int/report/philippines/ndrrmc-update-sitrep-no04-re-magnitude-72-earthquake-sarangani-davao-occidental (accessed on 24 November 2025).

- Buhay, D.J.L.; Legaspi, C.J.M.; Dizon, R.P.A.; Abigania, M.I.T.; Papiona, K.L.; Bautista, M.L.P. Development of a Database of Historical Liquefaction Occurrences in the Philippines. Earth Sci. Rev. 2024, 251, 104733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J. Empirical Relationships between Earthquake Magnitude and Maximum Distance Based on the Extended Global Liquefaction-Induced Damage Cases. Acta Geotech. 2022, 18, 2081–2095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y.; Ding, L.; Liu, J.; Chen, J. Probabilistic analysis of seismic mitigation of base-isolated structure with sliding hydromagnetic bearings based on finite element simulations. Earthq. Eng. Resil. 2023, 2, 194–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsuchida, H. Prediction and Countermeasure against the Liquefaction in Sand Deposits. In Abstracts of the Seminar in the Port and Harbor Research Institute; Ministry of Transport: Yokosuka, Japan, 1970; pp. 31–33. [Google Scholar]

- Daag, A.S.; Aque, L.E.; Locaba, O.; Grutas, R.N.; Solidum, R.U., Jr. Site Response Measurements and Implications to Soil Liquefaction Potential Using Microtremor H/V in Greater Metro Manila, Philippines. Geomat. Nat. Hazards Risk 2023, 14, 2256936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Association of Structural Engineers of the Philippines (ASEP). National Structural Code of the Philippines; Association of Structural Engineers of the Philippines (ASEP): Quezon City, Philippines, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Worden, C.B.; Hearne, M.; Thompson, E.M. USGS ShakeMap v4 Software and Documentation; U.S. Geological Survey: Reston, VA, USA, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Iwasaki, T.; Arakawa, T.; Tokida, K.-I. Simplified Procedures for Assessing Soil Liquefaction during Earthquakes. Int. J. Soil Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 1984, 3, 49–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, S.; Zhang, J.; Ye, J.; Zheng, J. Establishing Region-Specific N-VS Relationships through Hierarchical Bayesian Modeling. Eng. Geol. 2021, 287, 106105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daag, A.S.; Halasan, O.P.C.; Magnaye, A.A.T.; Grutas, R.N.; Solidum, R.U., Jr. Empirical Correlation between Standard Penetration Resistance (SPT-N) and Shear Wave Velocity (VS) for Soils in Metro Manila, Philippines. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 8067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Civelekler, E.; Afacan, K.B. Correlation between Shear Wave Velocity (VS) and Penetration Resistance along with the Stress Condition of Eskisehir (Turkey) Case. Nat. Hazards 2024, 121, 1043–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Department of Science and Technology—Philippine Institute of Volcanology and Seismology (DOST-PHIVOLCS). Liquefaction Hazard in the Philippines. 2018. Available online: https://gisweb.phivolcs.dost.gov.ph/gisweb/earthquake-volcano-related-hazard-gis-information# (accessed on 24 November 2025).

- Montgomery, D. Soil Erosion and Agricultural Sustainability. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 104, 13268–13272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wald, D.J.; Allen, T.I. Topographic Slope as a Proxy for Seismic Site Conditions and Amplification. Bull. Seismol. Soc. Am. 2007, 77, 1379–1395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Department of Science and Technology—Philippine Institute of Volcanology and Seismology (DOST-PHIVOLCS). 22 April 2019 MS 6.1 Central Luzon Earthquake; Department of Science and Technology—Philippine Institute of Volcanology and Seismology (DOST-PHIVOLCS): Quezon City, Philippines, 2020.

- Santucci de Magistris, F.; Lanzano, G.; Forte, G.; Fabbrocino, G. A Database for PGA Threshold in Liquefaction Occurrence. Soil Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 2013, 54, 17–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salcedo, J.C.; Hara, T. Earthquake Source Parameters for Subduction Zone Events Causing Tsunamis in and around the Philippines. Bull. Int. Inst. Seismol. Earthq. Eng. IISEE 2011, 45, 49–54. [Google Scholar]

- Papathanassiou, G.; Pavlides, S.; Christaras, B.; Pitilakis, K. Liquefaction Case Histories and Empirical Relations of Earthquake Magnitude versus Distance from the Broader Aegean Region. J. Geodyn. 2005, 40, 257–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, F.K.; Tsai, C.C.; Ge, L.; Lu, C.W.; Chi, C.C. Strength Variations Due to Re-Liquefaction—Indication from Cyclic Tests on Undisturbed and Remold Samples of a Liquefaction-Recurring Site. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 2022, 81, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Soil Sample | Fines Content | Cu | Cc | Mean Φ | Mean mm | Standard Deviation | Grain Sorting | Skewness | SK Tail |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A. BU1 | 3.9% | 2.55 | 1.13 | 2.37 | 0.19 | 0.85 | Moderately sorted | −0.09 | Nearly symmetrical |

| B. TU1 | 48.5% | 1.89 | 0.91 | 3.94 | 0.07 | 0.65 | Moderately sorted | 0.13 | Fine-skewed |

| C. TU2 | 28.9% | 1.93 | 1.08 | 3.73 | 0.08 | 0.58 | Moderately sorted | −0.12 | Coarse-skewed |

| D. SM1 | 32.4% | 3.52 | 0.53 | 3.52 | 0.09 | 1.03 | Poorly sorted | −0.15 | Coarse-skewed |

| E. MU1 | 35.8% | 2.16 | 0.96 | 3.74 | 0.07 | 0.74 | Moderately sorted | 0.05 | Nearly symmetrical |

| F. MU2 | 17.8% | 1.89 | 1.05 | 3.51 | 0.09 | 0.56 | Moderately sorted | −0.13 | Coarse-skewed |

| G. GP1 | 17.5% | 2.28 | 0.97 | 3.17 | 0.11 | 0.97 | Moderately sorted | 0.22 | Fine-skewed |

| H. GP2 | 3.3% | 1.95 | 1.14 | 2.68 | 0.16 | 0.62 | Moderately sorted | 0.58 | Strongly fine-skewed |

| I. GP3 | 20.6% | 2.25 | 1.02 | 3.51 | 0.09 | 0.78 | Moderately sorted | 0.001 | Nearly symmetrical |

| J. GP4 | 18.8% | 2.02 | 1.16 | 3.53 | 0.09 | 0.56 | Moderately sorted | −0.27 | Coarse-skewed |

| K. GP5 | 74.8% | 1.57 | 0.94 | 4.28 | 0.05 | 0.49 | Well sorted | 0.14 | Fine-skewed |

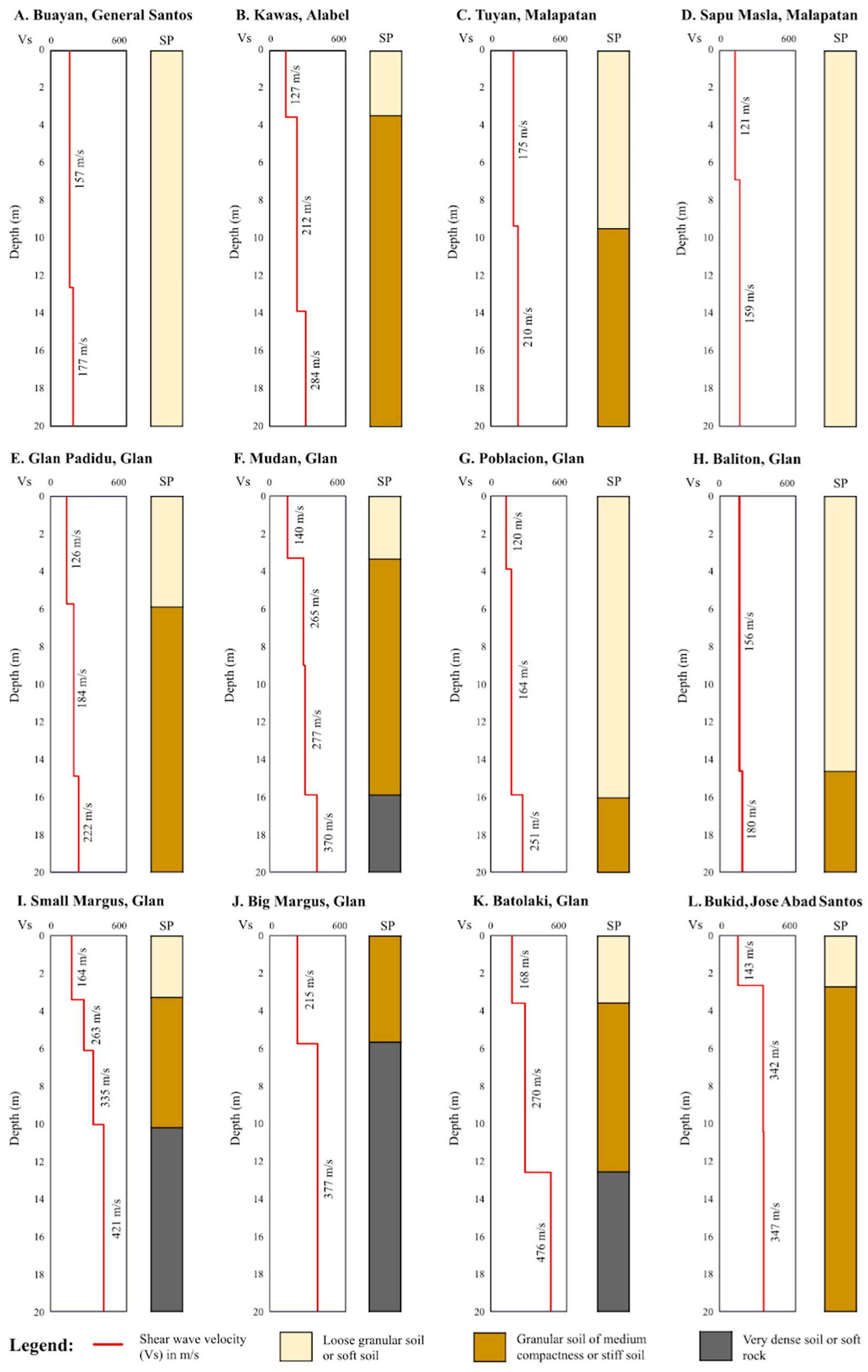

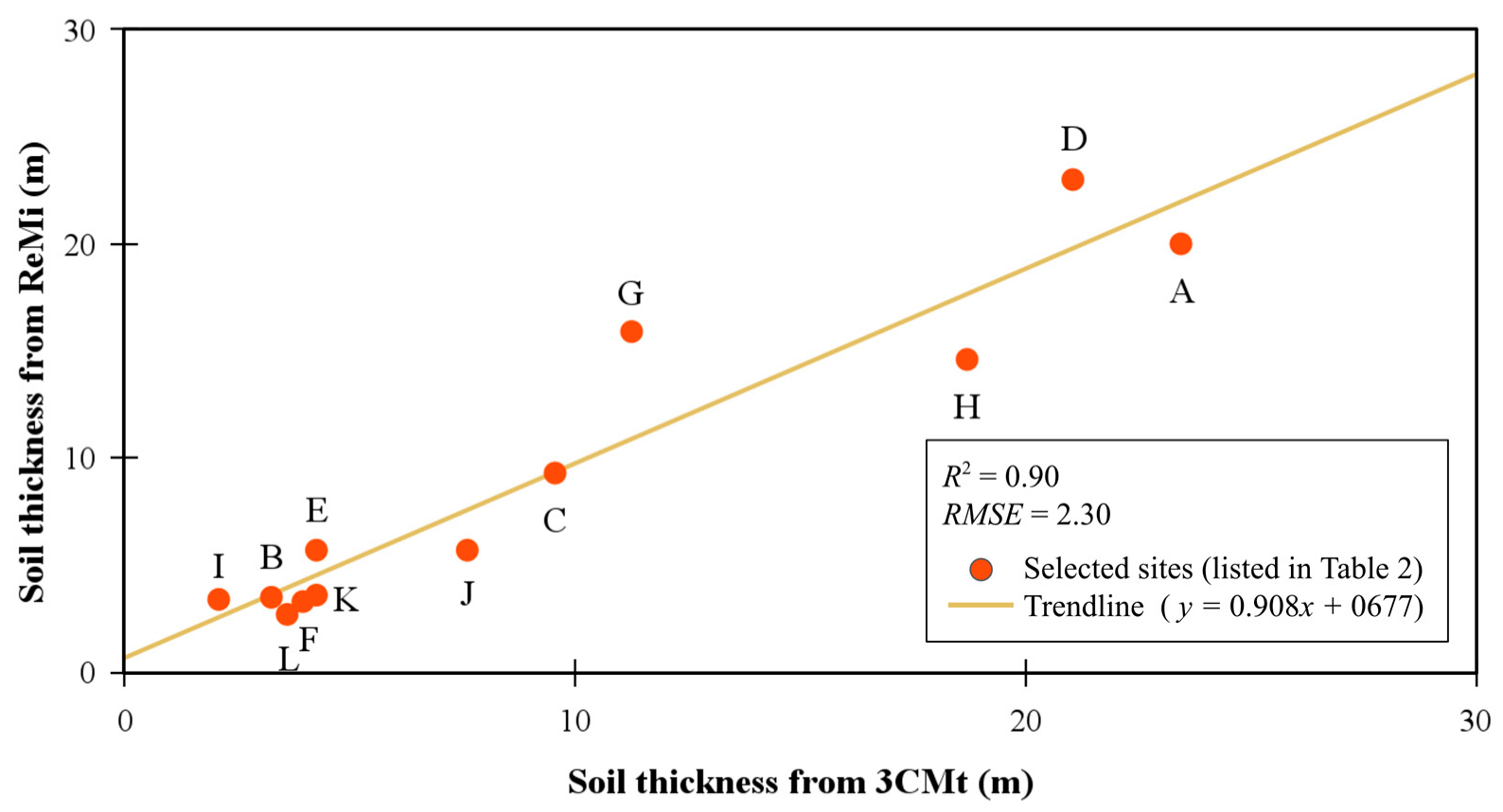

| Site | Geomorphological Unit | Topmost VS a | VS30 | Site Class b | Site Period | Soil Thickness | PGA | LPI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| from 3CMt | from ReMi | ||||||||

| A. Buayan, General Santos | Delta | 157–177 m/s | 189 m/s | SD | 0.94– 1.1 s | 22.0– 24.9 m | 20 m | 0.26 g | very high |

| B. Kawas, Alabel | River bar | 127 m/s | 253 m/s | SD | 0.08–0.09 s | 3.1– 3.4 m | 3.5 m | 0.24 g | high |

| C. Tuyan, Malapatan | Beach | 175 m/s | 221 m/s | SD | 0.25–0.41 s | 7.8– 11.3 m | 9.3 m | 0.26 g | high |

| D. Sapu Masla, Malapatan | Delta | 121–159 m/s | 170 m/s | SE | 0.81–0.94 s | 19.8– 22.3 m | 23 m | 0.27 g | very high |

| E. Glan Padidu, Glan | Delta | 126 m/s | 184 m/s | SD | 0.07–0.18 s | 2.6– 5.9 m | 5.7 m | 0.34 g | very high |

| F. Mudan, Glan | River bar | 140 m/s | 278 m/s | SD | 0.08–0.15 s | 3.0– 4.9 m | 3.3 m | 0.32 g | high |

| G. Poblacion, Glan | Marsh | 120–164 m/s | 186 m/s | SD | 0.41 s | 11.2– 11.3 m | 15.9 m | 0.36 g | very high |

| H. Baliton, Glan | Pond | 156 m/s | 198 m/s | SD | 0.71–0.84 s | 17.5– 19.9 m | 14.6 m | 0.34 g | very high |

| I. Small Margus, Glan | Beach | 164 m/s | 339 m/s | SD | 0.07–0.26 s | 2.6– 7.8 m | 3.4 m | 0.29 g | very low |

| J. Big Margus, Glan | Beach | 215 m/s | 425 m/s | SC | 0.13–0.38 s | 4.6– 10.6 m | 5.7 m | 0.26 g | very low |

| K. Batolaki, Glan | Beach | 168 m/s | 330 m/s | SD | 0.08–0.17 s | 3.0– 5.5 m | 3.6 m | 0.28 g | very low |

| L. Bukid, Jose Abad Santos | Delta | 143 m/s | 310 m/s | SD | 0.07–0.13 s | 2.7– 4.5 m | 2.7 m | 0.24 g | low |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Buhay, D.J.L.; Brusas, B.D.B.; Marquez, J.K.A.; Dajao, P.P.; Mangahas-Flores, R.Z.; Mercado, N.J.L.; Halasan, O.P.C.; Vidal, H.A.L.; Manlapat, C.J.F.C. Soil Liquefaction in Sarangani Peninsula, Philippines Triggered by the 17 November 2023 Magnitude 6.8 Earthquake. GeoHazards 2025, 6, 80. https://doi.org/10.3390/geohazards6040080

Buhay DJL, Brusas BDB, Marquez JKA, Dajao PP, Mangahas-Flores RZ, Mercado NJL, Halasan OPC, Vidal HAL, Manlapat CJFC. Soil Liquefaction in Sarangani Peninsula, Philippines Triggered by the 17 November 2023 Magnitude 6.8 Earthquake. GeoHazards. 2025; 6(4):80. https://doi.org/10.3390/geohazards6040080

Chicago/Turabian StyleBuhay, Daniel Jose L., Bianca Dorothy B. Brusas, John Karl A. Marquez, Paulo P. Dajao, Robelyn Z. Mangahas-Flores, Nicole Jean L. Mercado, Oliver Paul C. Halasan, Hazel Andrea L. Vidal, and Carlos Jose Francis C. Manlapat. 2025. "Soil Liquefaction in Sarangani Peninsula, Philippines Triggered by the 17 November 2023 Magnitude 6.8 Earthquake" GeoHazards 6, no. 4: 80. https://doi.org/10.3390/geohazards6040080

APA StyleBuhay, D. J. L., Brusas, B. D. B., Marquez, J. K. A., Dajao, P. P., Mangahas-Flores, R. Z., Mercado, N. J. L., Halasan, O. P. C., Vidal, H. A. L., & Manlapat, C. J. F. C. (2025). Soil Liquefaction in Sarangani Peninsula, Philippines Triggered by the 17 November 2023 Magnitude 6.8 Earthquake. GeoHazards, 6(4), 80. https://doi.org/10.3390/geohazards6040080