Abstract

The aim of the present research is to analyze community participation in disaster risk management due to tailings dam failures (DRM-TDF). Conceição do Mato Dentro, Minas Gerais State (Brazil) was used as case study. The aims of the study are to help developing more effective DRM-TDF strategies and to strengthen community participation in decision making, and in mapping and categorizing vulnerabilities (criticality and support capacity) by assessing current practices and prioritizing future strategies. Semi-structured questionnaires were applied to community leaders and open interviews were carried out with DRM experts for information collection purpose. The collected responses were categorized based on vulnerabilities by taking into account criticality (communities) and support capacity (public management and mining entrepreneurs). SWOT analysis identified “Weaknesses” (criticality) and “Threats” (support capacity), whereas Pareto analysis highlighted the most critical aspects. The results indicate that public policies and the Brazilian legal framework have made limited contributions toward achieving the Sendai Framework guidelines and the Sustainable Development Goals. A review of current practices is necessary to safeguard the rights of affected communities through their meaningful participation in decision-making processes.

1. Introduction

Disasters are complex phenomena resulting from interactions between adverse events and the social system that generate long lasting socio-environmental and economic impacts [1,2,3,4]. Valêncio [4] described disaster as potentialized risk materialization linked to social failures highlighted by the interaction between adverse-event spatialization, and the exposure conditions and vulnerability of affected populations.

By bearing in mind vulnerability as essential step towards disaster risk management, it is possible to develop more effective strategies by understanding vulnerability as a multifaceted phenomenon. Vulnerability must be analyzed in an understandable fashion by taking into account quantitative and qualitative aspects regarding social, economic, institutional, and environmental factors [5,6]. Identifying and measuring these vulnerabilities allow the development of disaster risk management—DRM—approaches that, in turn, more accurately meet the population’s needs and increase community resilience to face hazardous events.

DRM is a core topic in public policy and urban development practices, especially concerning exposure and vulnerability to natural and technological disasters. Tailings dam failures (TDF) in Brazil have proven to be one of the main threats to communities due to their devastating consequences for both the environment and the lives of affected populations. The study by Bowker and Chambers [7] highlighted society’s concern about TDF accidents in research covering the period between 1960 and 2010. They found that “serious” and “very serious” failures of these structures, i.e., with consequential compromise of environmental security beyond the mine site, comprise 63% of the total incidents from 1990 to 2010. The total cost of just 7 of the very serious failures was USD 3.8 billion, with an average cost of USD 543 million per failure.

Disasters such as those witnessed in the Brazilian municipalities of Mariana [8] and Brumadinho [9] have highlighted the urgent need to implement more effective DRM strategies based on community participation [10,11,12,13]. This need becomes even more significant considering the large number of mineral tailings dams in Brazil, particularly in Minas Gerais State. According to the Mining Dam Safety Management System (SIGBM) [14], Brazil has 921 registered mineral tailings dams as of 2025, with 421 of them (approximately 47%) located in Minas Gerais State. This concentration represents a significant potential risk for families living downstream of these structures.

The relevance of inclusive and collaborative DRM approaches is emphasized by the Sendai Framework [1], which highlights the need to strengthen community resilience and ensure active participation in decision-making processes. By clearly assigning roles to communities for each priority, the Sendai Framework shifts from being a top-down policy to a practical guide for local action. Communities go from just providing data to actually making decisions, helping bridge the gap between global goals and real-life resilience. The Sendai Framework also states that local knowledge and interaction among public management, civil society, and the private sector collectively contribute to achieving more effective disaster risk reduction.

History has shown that Brazilian democracy has undergone several transformations before reaching its current representative model, in which the population exercises power indirectly by electing representatives to make decisions on its behalf. Although the representative democracy model prevails in Brazil, as in many other contemporary societies, it often faces challenges in ensuring full popular participation in political decisions [15].

The electoral process in the Brazilian political system delegates decision-making power to elected representatives, often limiting citizens’ ability to have direct influence over both public policies and governmental actions [15,16,17]. Accordingly, Brazil’s representative democracy faces persistent challenges in guaranteeing that the voices of its citizens—particularly those from the most vulnerable social groups—are consistently and effectively heard. According to Maia [15], democracy must go beyond voting and seek ways to guarantee broader and more effective public participation in political decisions to overcome inequalities and ensure the rights of all.

Thus, it is essential to implement mechanisms aimed at ensuring effective social participation in DRM-TDF, enabling communities to contribute to decision-making processes. A systematic search was carried out in the Scopus® database for articles published in the last 20 years (2004–2024) in Portuguese, English, Spanish, and French, given the relevance of the topic addressed herein. A gap was identified in the literature regarding publications that address all the selected keywords, namely “mineral tailings dams”, “disaster risk management”, “participatory management”, and “vulnerability”.

To contribute to the development of more effective DRM-TDF strategies and to strengthen community participation in decision-making processes, the main objective of the present research was to assess the effectiveness of community participation in DRM- TDF, using the municipality of Conceição do Mato Dentro, Minas Gerais (Brazil), as a case study. The research also targeted the following specific objectives:

- Mapping the impact of community vulnerability, public management, and mining enterprises on the capacity to manage risks related to mining tailings dam failures;

- Understanding the influence of internal and external vulnerability dynamics on community participation in DRM-TDF;

- Analyzing current DRM-TDF practices to determine how they encourage or hinder community participation;

- Identifying and prioritizing critical aspects in the analysis of current practices to guide the definition of future DRM-TDF strategies.

2. Study Site

Conceição do Mato Dentro (CMD), is a Serra do Espinhaço municipality located 168 km from Belo Horizonte city, close to Serra do Cipó National Park. The municipality stands out for its landscape and historical heritage, including buildings from the 18th century. Covering an area of 1720 km2, the territory has approximately 23,163 residents, as reported in the 2022 census [18]. CMD has consolidated itself as touristic destination over the years [19].

Its history dates back to the 18th century, when it experienced an intense mining cycle, which turned it into the well-known New Eldorado. In 1702, Gabriel Ponce de Leon built a chapel dedicated to Our Lady of the Conception, which launched this settlement. After the gold mining decline, the mining activity rose back in the 1950s driven by the post-World War II demand [20,21].

In 2014, an Operating License was issued to allow the Minas-Rio Project to operate; since then, CMD has suffered from severe impacts caused by the mining activity. This megaproject is expected to produce 26.5 million tons of iron ore on a yearly basis. It includes a 525-km pipeline, which is the largest in the world, in addition to its participation in a port terminal in Rio de Janeiro [21,22].

Communities located downstream the Minas-Rio Project in CDM have faced significant conflicts with the mining company. Families from Água Quente, Beco, Passa Sete, and São José do Jassém communities, for example, have reported pressure to accept inadequate resettlement proposals. They claim that the mining company does not meet their demands for fair conditions and respecting their cultural traditions [23,24].

An agreement was signed on 27 November 2024 by the mining company, the Public Prosecutor’s Office of Minas Gerais, and the affected communities in response to their demands. The Independent Technical Advisory (ATI 39, in Portuguese) was established as a condition of the Anglo American’s environmental license for the expansion and operation of the Sapo mine, and also functions as an advisory mechanism for resettlements negotiations between the communities and the mining company [25]. This agreement set the parameters for resettling approximately 400 families in the self-rescue zone (SRS) of the Minas-Rio tailings dam [24,26]. Despite this progress, the resettlement process has been marked by tensions and mistrust. According to these communities, the mining company uses resettlement as a “bargaining chip” to obtain environmental licenses, in clear disregard for previous agreements [10,11,12].

These conflicts reflect the challenges faced by CMD communities due to the socio-environmental impacts caused by the Minas-Rio Project. They highlight the need for more transparent and inclusive discussions among the mining company, authorities, and local residents to find fair solutions, promote greater community participation in decision making, and ensure sustainable conditions [19,23,24,25].

The Minas-Rio Project [22] covers the municipalities of Conceição do Mato Dentro (CMD), Alvorada de Minas (AM), Dom Joaquim, and Santo Antônio do Grama in Minas Gerais State. In addition to the mining and processing facilities, which are primarily located in Conceição do Mato Dentro and Alvorada de Minas, the project includes a 529-km pipeline that crosses 33 municipalities and connects the mine to Açu Port in Rio de Janeiro State. Water for the project is sourced from Dom Joaquim, while Serro serves as the transportation route for inputs. These locations, along with Conceição do Mato Dentro and Alvorada de Minas, make up the project’s direct influence area.

Figure 1 shows the location of 11 communities affected by the implementation of the Minas-Rio Project, which receive technical assistance from the Advisory Center for Communities Affected by Dams (NACAB, in Portuguese) [25], to comply with the requirements of the Environmental Operating License.

Figure 1.

Location of priority communities located close to Minas-Rio project (source: NACAB Website). The inset map highlights the position of the municipality of Conceição do Mato Dentro within the state of Minas Gerais.

3. Methods

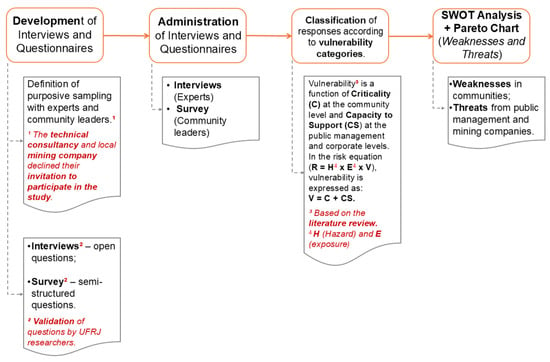

The research followed a qualitative and quantitative approach, mobilizing community leaderships (questionnaire in Appendix A) from three of the eleven communities affected by the Minas-Rio Project as well as DRM-TDF experts (interviews in Appendix A). It was divided into sequential stages to ensure the in-depth analysis of community participation in DRM-TDF. Figure 2 provides a summary of the methodological flowchart employed in the research.

Figure 2.

Methodological flowchart.

It is important to note that, currently, of the thirteen communities affected by the mining company’s activities, only ten remain unsettled. The research considered the participation of leaders from all ten remaining communities, representatives from the Independent Technical Advisory Group (NACAB), Anglo American, civil defense authorities from both affected municipalities, members of the Movement of People Affected by Dams (MAB, in Portuguese), and experts with experience in DRM-TDF who were involved in the response efforts following the Mariana and Brumadinho disasters. However, only three community leaders agreed to participate in our research, while the other invitees—with the exception of NACAB and the mining company, which both declined the invitation—chose not to participate.

3.1. Data Collection

Questionnaires were applied to community leaders, and interviews were conducted with DRM-TDF experts for the purpose of data collection. Only 3 (SAPO, Passa Sete, and São José de Jassém) of the 13 communities currently exposed to mining activities in Conceição do Mato Dentro (CMD) agreed to participate in the research. In addition to community leaders, the research encompassed a group of experts (civil defense coordinators, a consultant, a scholar, and a representative of a social movement). Table 1 shows respondents’ profile and the data collection method.

Table 1.

Respondents’ profile and data collection methods.

Data collection took place between 10 June 2024 and 24 June 2024 on the platforms Google Meet® and WhatsApp®. The questionnaire held 44 semi-open questions organized into five sections: (i) Community Features; (ii) Aspects Affecting the Community; (iii) Disaster Risk Management; (iv) Relationship between Parties; and (v) General Questions.

The participants were community leaders from Conceição do Mato Dentro. The selection process prioritized individuals recognized for their leadership roles within their communities and for their prior involvement in participatory processes related to DRM-TDF, thereby ensuring representation across diverse local segments. Digital platforms were employed to enhance participant convenience, optimize time management, and facilitate data recording and systematization. A high level of engagement was observed throughout the process, with participants dedicating an average of approximately 90 min to the activities and providing detailed, in-depth responses to each question.

Employing digital platforms proved to be an effective strategy, aligning with the research context, the study’s objectives, the characteristics of the target audience, and local constraints. The approach maintained the quality of the responses, ensuring the richness of narratives and the depth of information gathered. Thus, the methodology safeguarded the integrity of the data, strengthening the reliability of the study’s findings and analysis.

The interview was structured and based on 22 open questions distributed into 7 sections: (i) Respondents’ Identification and Profile; (ii) Public Policies; (iii) Mining Industry; (iv) Affected Communities; (v) Public Agencies, and Civil Protection and Defense; (vi) Relationship between Parties; and (vii) Final Discussion.

The collected responses were organized and filed in Microsoft Excel® spreadsheets for data analysis purpose. All interviewees received and signed the Free and Informed Consent Form, in compliance with interview propositions. Appendix A provides the questionnaires and interviews’ structure, and their association for reader’s understanding purpose.

3.2. Vulnerability Factors and Criteria

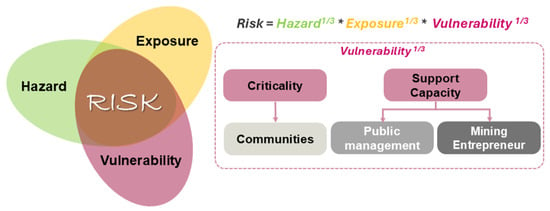

If one bears in mind that vulnerability is one of the key components of risk (Risk = Hazard × Exposure × Vulnerability), then community participation in DRM-TDF is closely linked to the degree of vulnerability of the population to these risks. Community participation—or lack thereof—can either mitigate or exacerbate local vulnerability in the event of an existing hazard.

Thus, it was possible to issue a diagnosis to qualify and quantify social vulnerability factors and criteria after gathering information from stakeholders. This process allowed for the identification of three main dimensions: vulnerability associated with community criticality, vulnerability related to the support capacity of public management, and vulnerability related to the support capacity of the mining company.

Therefore, vulnerability comprises two core aspects: (i) criticality, associated with communities, and (ii) support capacity, linked to both public management and the mining company [5,6,27,28,29], as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Components of risk and vulnerability.

Three subsystems were taken into consideration to form vulnerability, according to studies by Leone [6,27] and Zêzere [30] based on adjustments in research reality, namely: (i) Community, (ii) Public Management, and (iii) Mining Entrepreneur (Table 2). These adjustments were based on the scientific literature [5,6,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35], on the Brazilian legislation for the rights of those affected by dams [36], and on the revised National Policy for Civil Protection and Defense [37,38].

Table 2.

Main vulnerability categories and subsystems (adapted from [6,30]).

In the case of community leadership, the criterion established for categorizing vulnerability was set at a minimum threshold of 75%. Given a total sample universe of four respondents, this threshold was chosen to ensure that only categories exhibiting a perceptible consensus—namely, those mentioned by at least three of the four participants—would be classified as significantly representative within the study context. Although this criterion is influenced by the limitations of the sample size, it seeks to ensure analytical robustness by privileging relevant convergences within the group while simultaneously minimizing the impact of occasional or atypical responses.

For the analysis of the semi-structured interviews with specialists—which included six participants—a threshold of 67% was adopted, corresponding to at least four coinciding responses regarding the same thematic category. This threshold was selected according to the same principle of valuing consensus, albeit adjusted for the specific sample universe, and always aiming to maintain a balance between representativeness and the necessary flexibility for qualitative research.

It is important to note, however, that the application of such cut-off points is situated within the limitations inherent to reduced samples. On the other hand, this methodological rigor contributes to the internal consistency of the analysis and ensures methodological traceability of the findings.

The “main categories of community vulnerability” listed in Table 2 were defined with reference to the specialist literature on DRM and were adapted for the local context through a preliminary territorial analysis. Each section of the questionnaire administered to community leaders comprised groups of questions addressing specific dimensions of vulnerability, such as local support capacity, access to risk information, preventive infrastructure, and institutional linkages.

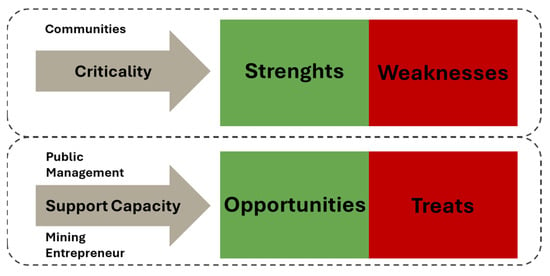

3.3. Social Vulnerability Classification According to SWOT

The SWOT method was adopted to identify communities’ main “Weaknesses” and “Strengths” in prevention, mitigation, preparation, and response, as recommended by DRM, as well as the “Threats” and “Opportunities” set to communities by Public Management and by the Mining Entrepreneur. It is worth noticing that questions in the questionnaires and interviews were designed to enable identifying vulnerability factors and criteria, as well as to allow the SWOT method application. For example, questions such as “Does the community have facilitated access to information on evacuation procedures?” or “Is appropriate rapid response equipment locally available”? were assigned to the categories of “access to information” and “response capacity”, respectively. The identification of these categories enabled the organization of responses into operational dimensions, thus facilitating subsequent comparative analysis and association with the SWOT matrix.

Vulnerability classification related to the SWOT method (Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, and Threats) enabled visualizing interrelations between strengths and weaknesses (Vulnerability of Communities) and opportunities and threats (Public Management and Mining Entrepreneurs vulnerabilities) linked to disaster risks due tailing dams’ failures (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

SWOT analysis associated with vulnerability.

After the categorization of responses (see Section 3.2), these were subsequently linked to the variables of the SWOT analysis. The categories identified as predominant, according to the percentages described, were classified as follows:

- Strength: when the response indicated the presence of a positive attribute, distinguishing feature, or community resource that contributes to local resilience.

- Weakness: when the response revealed significant gaps, deficiencies, or limitations.

- Opportunity: in cases where specialists highlighted external conditions or trends conducive to improvements in DRM.

- Threat: when testimonies converged in identifying adverse external factors or potential aggravators of vulnerability.

For instance, the recognition by community leaders of the existence of collaborative networks between the community and the local civil defense was categorized as a “strength”. In contrast, the absence of viable evacuation routes was considered a “weakness”, illustrating this process of association. Among specialists, the identification of opportunities for inter-institutional partnerships was highlighted as an “opportunity”, whereas the pressure for mining expansion into sensitive areas constituted a “threat”.

By quantifying each factor, it was possible to carry out a more objective analysis by quantifying each factor and, consequently, to identify the main strengths and weaknesses.

3.4. Pareto Analysis

Pareto Diagram was used to prioritize issues identified through SWOT analysis, which is a strategic tool to help finding the most critical issues expressed in a decreasing bar chart organized by frequency. This approach focused issues accounting for the most remarkable impacts on communities affected by tailings dams.

The Pareto Diagram methodology was applied to identify and prioritize critical “weaknesses” and “threats” linked to community vulnerability (criticality) and to the support capacity of public administration and mining enterprises. Vulnerability categories were then organized in descending order by response frequency, and the percentage and cumulative percentage of each were calculated to highlight the most significant weaknesses and threats.

This methodological approach is grounded in the premise that, in complex systems, a minority of factors accounts for the majority of undesired effects, thereby allowing efforts to be concentrated on the most relevant issues concerning community participation in DRM-TDF. The use of the Pareto Diagram not only assists in the objective visualization of priorities but also provides a robust and transparent foundation for decision making by public administrators, considering their duties and responsibilities within the scope of DRM-TDF.

Each set of issues focused on Criticality and Support Capacity is observed in the result analysis (below) and plotted in graphs—those within the 80% limit were considered the most relevant ones. Questionnaire and interview will be summarized to make the understanding of this DRM-TDF classification issue easier.

4. Results

The questionnaire and interview responses were initially analyzed to identify patterns and similarities in each group of questions answered by community leaders and experts to make subsequent research stages easier in order to avoid repetitions. When it comes to interviews, it was necessary to make an in-depth assessment of individual responses to ensure accurate common trends’ identification. According to the initial analysis, the 168 responses from community leaders and the 128 ones from experts were grouped into 42 and 103 categories, respectively, to allow a more organized and representative overview of the collected data. This process synthesized 103 responses. Table 3 summarizes the features of each group of participants.

Table 3.

Characteristics of community leaders (CL) and experts (E).

4.1. Criticality

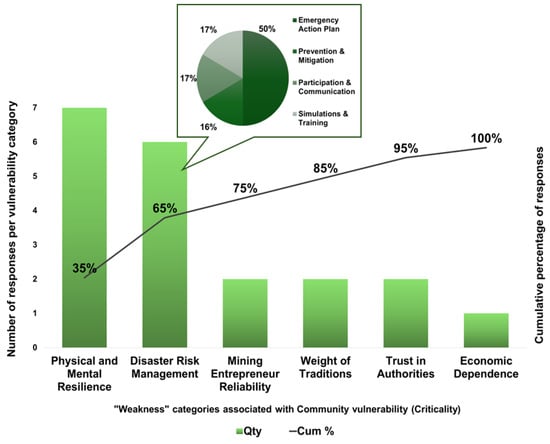

The SWOT analysis applied to criticality reveals that weaknesses, accounting for 50%, pose a significant challenge for implementing, maintaining, and continuously improving DRM-TDF.

Figure 5 presents the Pareto analysis applied to vulnerability categorization and its association with the SWOT matrix. The four aspects presenting the strongest impact on criticality were (i) physical and mental resistance, (ii) disaster risk management (DRM), (iii) trust in the mining entrepreneur, and (iv) importance of traditions.

Figure 5.

Pareto analysis of community weaknesses and detail to DRM (pie chart in balloon).

DRM, in its turn, encompasses four fundamental subaspects: emergency action plan (EAP), prevention and mitigation, participation and communication, and simulations and training (Figure 5).

Table 4 summarizes the main results of the Pareto analysis applied to criticality. The first four categories were taken into consideration. Together, they account for 85% “weaknesses”, as shown by the SWOT analysis.

Table 4.

Pareto analysis summary—community criticality (CC).

4.2. Support Capacity

According to the SWOT analysis applied to public management support capacity, 58% of answers were classified as “threats” to communities, whereas 42% of them were taken as “opportunities”.

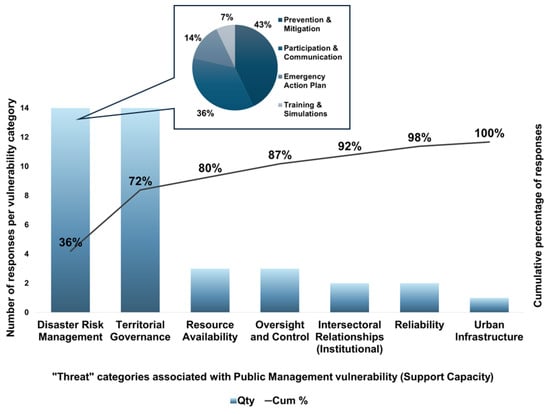

Figure 6 depicts the Pareto analysis relating vulnerability categories to the SWOT matrix in order to assess public management support capacity. The main observed factors identified as “threats” were (i) disaster risk management (DRM), (ii) territorial governance associated with municipal management, (iii) availability of resources, and (iv) monitoring and control.

Figure 6.

Pareto analysis of the government’s support capacity threats and detail to DRM category (pie chart in balloon).

Essential DRM topics are prevention and mitigation, participation and communication, emergency action plan (PAE), and simulations and training stages (Figure 6).

Table 5 summarizes information about public management support capacity (PM-SC) regarding vulnerability categories identified as “threats” to communities. Some experts who contributed to the current research were experienced in community participation in DRM-TDF in other Brazilian municipalities, mainly in Mariana and Brumadinho.

Table 5.

Pareto analysis summary—public management support capacity (PM-SC).

Some community leaders added comments to objective responses during questionnaire application in order to better illustrate their perceptions. These contributions were added to the summary table to reinforce their analyses.

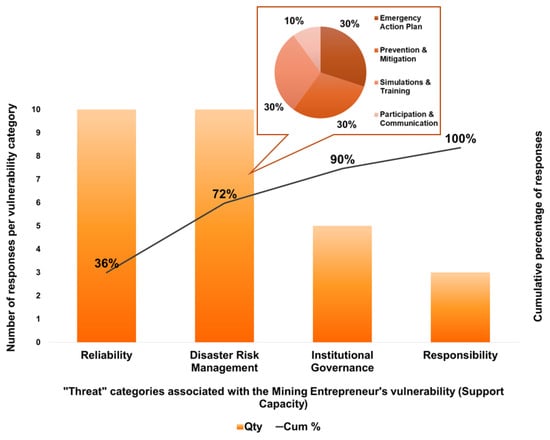

The Pareto analysis in Figure 7 highlights the prevalence of “threats” associated with the mining entrepreneur’s support capacity. SWOT matrix application pointed out that 78% of collected responses were classified as “threats” for communities, whereas only 22% of them were taken as “opportunities”. Figure 7 also highlights “threats” related to DRM (pie chart in balloon).

Figure 7.

Pareto analysis of the mining industry’s support capacity threats and details of the DRM category (pie chart in balloon).

Table 6 summarizes categories classified as “threats” to the mining industry’s support capacity (MI-SC), as highlighted by reports from experts based on experiences lived in Conceição do Mato Dentro communities and in other municipalities. These categories were identified through analysis applied to experts’ perceptions about the negative impacts of mining activities.

Table 6.

Pareto analysis summary—mining industry’s support capacity (MI-SC).

The result analysis also showed that mining entrepreneurs have more significant negative impact (58%) on communities than public management (42%) when it comes to DRM-TDF processes. However, it is important clarifying that public management is a great moderator. Therefore, it accounts for reducing its negative impacts on society and for ensuring compliance with legal duties in order to achieve a strong and democratic society.

5. Discussion

Structures such as mining tailings dams in Brazil are subject to a strict legal framework that regulates everything from research licensing regimes to mining concessions, regulatory standards, taxation, and royalties (financial compensation for mineral resource exploitation), as well as environmental licensing and even mine decommissioning [36,37,41,42,43,44]. Any mining company must obtain an operating license issued by federal, state, and municipal environmental agencies before starting operations. The environmental licensing process includes preliminary, installation, and operating licenses, which are part of the disaster risk management process. These licenses take into consideration the impacts on, and the socio-environmental vulnerability of, affected communities [45,46,47,48].

The disasters in Mariana [8] and Brumadinho [9] have shed light on society’s environmental licensing process [43,45,46,48], national civil protection and defense policies [37,38], the city statute [49], and the entire legal framework related to the mining industry, which has proven insufficient to prevent, mitigate, and prepare communities for response and recovery actions. The weakening of environmental licensing in Minas Gerais State derives from legislative changes that have increased socio-environmental vulnerability during such disasters [11,12,31,32]. Therefore, these regulations must be reviewed by public authorities across the executive, legislative, and judicial branches [12,50,51,52].

Conflicts between communities, public management agents, and mining companies have intensified since the Mariana and Brumadinho accidents due to “instability and lack of trust in the governance system” [13]. These authors also state that the relationship between public governance and mining companies “is marked by games of interest and power relations”. This political aspect was highlighted by community leaders, who noted that “municipal councilors, who have been in office for more than two terms, do not act in favor of the affected communities. The former mayor, for example, did little to implement improvement actions in the municipality and left everything on paper”.

Underprivileged communities often lack the resources to respond to and recover from disasters, which is one of the key aspects of social vulnerability [4,5,7,29,53,54,55]. It is important to note that social vulnerability (SV) refers to “specific individual characteristics, individuals’ socioeconomic relationships, and the physical environment in which they live” [28].

The increased global demand for minerals since the mid-1950s has led to a rise in the number of tailings dam constructions in Brazil and abroad [13,21,33], creating new hazards and risks. It is important to emphasize that the risk of technological disasters is increasing as societies become more dependent on complex and large-scale technologies, as noted by several researchers [52]. In a society where social vulnerability is high, as in many Brazilian municipalities, exposure to risks from technological disasters is proportionally critical, exacerbating poverty and social exclusion [12,13].

According to the Sendai Framework, reducing social vulnerability is essential to reducing disaster risks [1]. This aligns with Beck’s perspective [56], which suggests that modern society should rethink how it deals with risks and disasters to achieve a more democratic approach to social justice. Socioeconomic inequality has a direct influence on communities’ ability to anticipate, respond to, and recover from disasters. To address social vulnerability in disaster management, two key aspects must be considered: criticality and support capacity, which reflect a community’s ability to resist, absorb, and recover from adverse events [28,53,54,57].

Reports from community leaders in Conceição do Mato Dentro and Alvorada de Minas indicate that residents do not feel prepared to protect themselves from dam failures, and fear of such an event has caused physical and mental health issues in some individuals. This insecurity primarily stems from unclear communication in public assemblies mediated by the Public Prosecutor’s Office and from widespread distrust in both government actions and the mining company.

The findings of this research, based on responses from community leaders and experts, indicate that communities do not trust public policies or authorities when it comes to guaranteeing their rights or representing their interests [10,13,15,52,54]. A recent decision by the Federal Court of Ponte Nova (MG) acquitted Vale, Samarco, and BHP Billiton, along with 21 of their executives, in the Fundão dam failures case [8], dismissing charges of homicide, bodily harm, environmental crimes, dam failure, and falsified environmental reports. This ruling serves as an example of the loss of trust in public authorities [26].

Communities’ lack of trust in the Brazilian government (at the executive, legislative, and judicial levels) and in the mining industry directly impacts stakeholder relationships, making effective risk management more difficult. In a democratic state governed by the rule of law, where elected representatives are expected to advocate for the interests of the population, such instances of liability exemption reinforce the ongoing negligence toward the rights of affected communities. This is a concerning observation. The disconnect between legal provisions and their actual enforcement underscores the need to strengthen governance and oversight of the mining sector.

Public management agents and mining entrepreneurs have clearly defined roles under Brazilian legislation at all stages of risk management (prevention, mitigation, preparedness, response, and recovery). However, communities are limited to being informed about the dangers and risks associated with mining activities during public hearings held as part of the environmental licensing process. These communities are later involved in response preparation by participating in training sessions and simulation exercises [12,47,57,58].

It is worth noting that these exercises often take place only once a year. Community leaders and experts have observed that community participation in training and simulations is hindered by the technical language used in presentations, which is particularly challenging for people in precarious and socially vulnerable conditions who require more accessible teaching methods. Communication and educational approaches regarding risk are often overlooked in studies focused on disaster risk management [31,32,34,50,52,59,60].

Unclear communication and a lack of transparency discourage community participation in the DRM-TDF process. Some experts noted that “the transparency issue in providing information on real potential risks to the population is not easily accessible”, and that a lack of “interest in establishing an open and equal dialogue with the communities” further weakens stakeholder relationships. One expert stated that “communities do not understand and do not know how to engage in the risk management process because they are often rural”, which presents a barrier in Conceição do Mato Dentro and other municipalities in Minas Gerais. A report from community leaders corroborates these expert observations, noting that “the first meetings with both the government and the mining company to disclose the emergency plan used highly technical vocabulary and acronyms that we did not understand”. Another community leader added, “after a while, people from the communities stopped attending the meetings because they did not understand anything and felt excluded”.

Another critical aspect of social vulnerability in DRM-TDF is the need to accommodate people with special needs. According to the research, some individuals require additional support, such as a community leader with a motor disability who struggles to navigate escape routes and reach designated meeting points in emergency action plans. Elderly residents, on the other hand, often do not “attend simulations because they do not believe they will adequately prepare them for a failure event, given that some communities are located just 500 m from the dams”.

Financial resources allocated by the public administration to DRM-TDF are a major concern. Municipalities often lack sufficient funding for risk management resources and infrastructure, forcing them to rely on state and federal support, which creates a dependency that weakens their capacity to address hazards. This is particularly alarming for a municipality ranked as the fourth largest in Gross Domestic Product (GDP) per capita in Minas Gerais State [18]. Resource limitations, influenced by political and social factors, exacerbate institutional vulnerability and negatively impact risk management [51]. This vulnerability allows mining companies to take on roles that should be led by civil defense authorities. According to experts, “the Civil Defense Department lacks resources and various initiatives, so we see the mining industry prevailing over this process”.

Public policies related to the mining sector are still shaped by an institutional and legal hierarchy [52] that often fails to interact with other government agencies, such as municipal master plans [39,60,61,62]. Experts have pointed out that “urban planning did not integrate with public policies aimed at preventing dam failures risks before the project was installed, nor even afterward”. The connection between public policies, territorial planning, and urban planning—such as land use and occupation—has great potential for disaster risk mitigation [13].

With regards to EAP, both groups have once again agreed that communities only get information and do not participate in EAP development. According to some researchers, the Samarco [8] and Vale [9] disasters exposed serious flaws in their emergency action plans (EAP), which have underestimated the risks, presented communication failures (sirens) regarding planning escape routes and meeting points, insufficient response time and lack of community participation in EAP development, among other aspects [12,13].

The collapse of dams in Mariana and Brumadinho disclosed the urgent need for reformulating EAPs based on stricter technical rigor, transparency, and community participation. Finally, community leaders (75%) stated that “mining projects should be avoided before having the prior mapping of affected communities and populations”, since it is essential for PAEBM elaboration.

It is important to acknowledge certain methodological limitations of this study. Because data were collected through semi-structured interviews and open questionnaires, participants self-selected into the study. Therefore, the sample may over-represent individuals who are more engaged or articulate, and under-represent those with limited time, lower literacy, or differing viewpoints. Consequently, the findings reflect the perspectives of those who chose to participate and may not capture the full diversity of experiences across the wider community.

It is essential to empower the populations affected by tailings dams through educational and inclusive risk management programs as way to achieve community participation in DRM-TDF. Accordingly, it is paramount to primarily assess the specific needs of each community in order to develop appropriate educational program contents by using accessible and easy-to-understand language. This program’s implementation must be followed by periodic assessments to enable identifying opportunities to achieve improvements in it and to ensure its continuous adjustments to local demands, and compliance with legal and regulatory requirements.

6. Conclusions

The main aim of the present research was to assess communities’ effective participation in disaster risk management related to the failure of mining tailings dams (DRM-TDF), using Conceição do Mato Dentro, Minas Gerais State, Brazil, as a case study. The assessment involved mapping and categorizing social vulnerability, considering its complexity, multidisciplinary nature, and importance in the risk equation, based on two aspects: criticality (associated with communities’ vulnerability) and support capacity (related to both public management and the mining entrepreneur).

The research identified internal (criticality) and external (support capacity) dynamics affecting community participation in DRM-TDF. It also analyzed current practices, identifying how they encourage or hinder effective community participation through a SWOT analysis. Finally, critical aspects were prioritized using Pareto charts to help guide future strategies and decision making within DRM-TDF. The aim was not only to improve DRM-TDF but also to strengthen communities’ recovery capacity and active participation in decision-making processes. According to the research, social vulnerability has a direct impact on communities’ ability to manage the risks associated with mining. It makes them more dependent on external resources (public management and mining entrepreneurs) and less prepared to respond to potential disasters.

Results have shown that public policies and the Brazilian legal framework have contributed little to meeting the guidelines of the Sendai Framework and the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). The main identified challenges concern the limited role of communities as outlined in Brazilian legislation, which restricts their involvement to attending training sessions and awareness-raising activities. Consequently, they lack effective influence over decisions related to DRM-TDF. Internal factors (criticality) intrinsic to communities, combined with external factors (support capacity from public management and mining entrepreneurs), have hindered community engagement in DRM-TDF, limiting their autonomy in the decision-making process.

Thus, it can be concluded that the research objectives were met and that the observed results can contribute to future studies, strategy formulation, and improved decision making, particularly in public management, by aligning with the Sendai Framework and the SDGs. To address the identified challenges, strengthening policies for social participation and implementing more effective control and transparency mechanisms are essential actions to ensure a fairer and more inclusive disaster risk management system that upholds the rights of affected communities.

Future research is recommended to explore models and methods that enable more meaningful community involvement, evaluate comparative experiences in other mining regions, and investigate innovative participatory frameworks in line with national and international guidelines, thereby supporting both academic advances and practical improvements in DRM-TDF.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.M.L., M.B.d.M., and J.L.Z.; methodology, D.M.L., M.B.d.M., and J.L.Z.; formal analysis, D.M.L., M.B.d.M., and J.L.Z.; investigation, D.M.L.; writing—original draft preparation, D.M.L.; writing—review and editing, D.M.L., M.B.d.M., and J.L.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

D.M.L. and M.B.d.M. are grateful for the support of the National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq), the Foundation for Research Support of the State of Rio de Janeiro (FAPERJ), and MCT/INCT-REAGEO. J.L.Z. was supported by Portuguese public funds through FCT—Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia, I.P, by the Research Unit. UIDB/00295/2020 (https://doi.org/10.54499/UIDB/00295/2020) and UIDP/00295/2020.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We thank the following for participating in the information gathering for our academic research: Centre for Studies and Research in Civil Defence of the State of Rio de Janeiro—CEPEDEC (RJ); Municipal Coordination for Civil Protection and Defence of Conceição do Mato Dentro (MG); Municipal Coordination for Civil Protection and Defence of Alvorada de Minas (MG); Coordination of the Movement of People Affected by Dams—MAB (BRAZIL); Oswaldo Cruz Foundation—FIOCRUZ (RJ); and Community leadership of Passa Sete, São Sebastião do Bom Sucesso (SAPO), and São José do Jassém.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that there are no financial, commercial, or institutional conflicts of interest that could have influenced the results or interpretations presented in this study. The research was conducted independently and objectively, without any interference from organizations or entities that could compromise its impartiality.

Appendix A

The following are the questions from the semi-structured questionnaire that was answered by the community leadership of Passa Sete, São José de Jassem, and SAPO (Table A1), and the interview questions that were answered by disaster risk management experts regarding tailings dam failures (Table A2).

Table A1.

Questionnaire that was answered by the community leadership.

Table A1.

Questionnaire that was answered by the community leadership.

| Section | Question |

|---|---|

| Block 1: Community characteristics | 1. What is the total number of residents (all age groups) living in the community? (Select only one answer) a. Fewer than 50 residents | b. 51 to 100 residents | c. 101 to 150 residents | d. 151 to 200 residents | e. More than 201 residents |

| 2. What is the average household income in the community? (Select only one answer) a. 25% of the minimum wage (Approximately USD 60.00) | b. 50% of the minimum wage (Approximately USD 120.00) | c. One minimum wage (Approximately USD 240.00) | d. Above one minimum wage (More than USD 240.00) | e. I don’t know | |

| 3. Are there people in the community with difficulties walking or climbing stairs? (Select only one answer) a. Yes | b. No | c. I don’t know | |

| 4. Are there people in the community with difficulties hearing, even when using hearing aids? (Select only one answer) a. Yes | b. No | c. I don’t know | |

| 5. Are there people in the community with difficulties seeing, even when using glasses or contact lenses? (Select only one answer) a. Yes | b. No | c. I don’t know | |

| 6. Are there people in the community with chronic illnesses that require annual medical follow-ups? (Select only one answer) a. Yes | b. No | c. I don’t know | |

| Block 2: Aspects affecting the community | 7. What are the main aspects that typically affect the daily lives of families in the community? (Select all applicable options) a. Supply of potable water through a public network | b. Public education | c. Public healthcare | d. Public security | e. Sanitation (sewage and waste collection) through a public network | f. Public transport | g. Others. Which? |

| 8. What do people in the community appreciate MOST about living in this region? | |

| 9. What do people in the community appreciate LEAST about living in this region? | |

| 10. Do you currently work or have you ever worked in the mining industry in your municipality? (Select the most applicable option) a. Yes | b. No | c. I don’t know | |

| 11. Does any family member currently work or has ever worked in the mining industry in your municipality? (Select the most applicable option) a. Yes | b. No | c. I don’t know | |

| Block 3: Disaster risk management | 12. Which of the following risks are considered of LEAST concern by families in the community? (Select all applicable options) a. Road accidents | b. Landslides | c. Fire | d. Flooding | e. Dam failure | f. Others. Which? |

| 13. Which of the following risks are considered of GREATEST concern by families in the community/region? (Select all applicable options) a. Road accidents | b. Landslides | c. Fire | d. Flooding | e. Dam failure | f. Others. Which? | |

| 14. Before the dam was built, did families already live in the community/location where they currently reside? (Select only one answer) a. Yes | b. No | c. I don’t know | |

| 15. Do families in the community have any emotional connection to the location/region where they live? (Select only one answer) a. Yes | b. No | c. I don’t know | |

| 16. What is the community’s opinion on the establishment of the mining industry in the municipality? (Select only one answer) a. Very good | b. Good | c. Average | d. Bad | e. Very bad | f. I don’t know | |

| 17. How does the community view the impact of the mining industry on their daily life and quality of life? (Select only one answer) a. Very positive | b. Positive | c. Average | d. Negative | e. Very negative | f. I don’t know | |

| 18. Have families in the community noticed any changes in their routine and/or way of living due to the tailings dam activities? (Select only one answer) a. Yes | b. No | c. I don’t know | |

| 19. Before the tailings dam was built, were families informed about the mining industry and its local activities? (Select only one answer) a. Yes | b. No | c. I don’t know | |

| 20. Do you know if the mining industry poses any risk to the communities? a. Yes | b. No | c. I don’t know | |

| 21. Were the hazards and risks communicated to the community before the tailings dam was built? (Select only one answer) a. Yes | b. No | c. I don’t know | |

| 22. If YES, how were hazards and risks communicated to the communities? (Select all applicable options) a. In meetings with environmentalists | b. Schools | c. City hall | d. Community leaders/representatives | e. Representatives of the tailings dam | f. Family members, friends, or neighbours | g. Others. Which? | |

| 23. If NO, have communities ever sought to learn about potential hazards and risks related to the tailings dam? (Select only one answer) | |

| Block 4: Relationship between stakeholders | 42. How would you rate the relationship between the communities and the mining industry? (Select only one answer) a. Very good | b. Good | c. Average | d. Bad | e. Very bad | f. I don’t know |

| 43. How would you rate the relationship between the communities and Civil Defence? (Select only one answer) a. Very good | b. Good | c. Average | d. Bad | e. Very bad | f. I don’t know | |

| Block 5: Final Discussion | 44. Would you like to add any comments about community participation in disaster preparedness and response that were not addressed and that you consider important? |

Table A2.

Interview questions that were answered by disaster risk management experts.

Table A2.

Interview questions that were answered by disaster risk management experts.

| Section | Question |

|---|---|

| Block 1: Identification and Respondent Profile | 1. Could you tell us a bit about yourself and your area of expertise? |

| 2. What is your relationship with the topic of Disaster Risk Management Related to Mining Dam Failures (DRM-TDF)? | |

| Block 2: Public Policies | 3. How are communities involved in the development of public policies and land-use planning? |

| 4. Are current public policies and land-use planning effective in reducing disaster risks (DRM-TDF)? | |

| 5. What is your opinion on the importance of identifying and assessing disaster susceptibility and vulnerability? | |

| 6. After the Mariana (2015) [8] and Brumadinho (2019) [9] disasters, have public policies undergone significant reforms to reduce disaster risks? | |

| Block 3: Mining Industry | 7. What is the role of the mining industry in DRM-TDF? |

| 8. Is the DRM-TDF model adopted by the mining industry effective in disaster preparedness and response? | |

| 9. How are communities involved in “preparedness and response actions” undertaken by the mining industry? | |

| 10. How does the mining industry work to prevent communities/people from being affected by its activities and in the event of a dam failure? | |

| Block 4: Affected Communities | 11. What is the role of communities in DRM-TDF? |

| 12. Are communities aware of the risks they are exposed to, and are they prepared to act in the event of a tailings dam disaster? | |

| 13. Do communities trust the public policies related to DRM-TDF? | |

| 14. Do communities trust the risk management model adopted by the mining industry? | |

| Block 5: Public Authorities and Civil Protection & Defence | 15. What is the role of Public Authorities and Civil Protection & Defence in DRM-TDF? |

| 16. How do Public Authorities and Civil Protection act within DRM-TDF to safeguard affected communities/people? | |

| 17. How are communities involved in “preparedness and response actions” carried out by Civil Protection & Defence? | |

| 18. Do communities trust the actions of Public Authorities in reducing disaster risks? | |

| Block 6: Relationship Between Stakeholders | 19. How would you assess the relationship between communities, the mining industry, and Civil Protection? |

| 20. Is it possible to establish a “commission for disaster risk reduction” with the participation of all three groups? | |

| Block 7: Final Discussion | 21. Considering community participation in disaster risk management, how could the accidents in Mariana (2015) [8] and Brumadinho (2019) [9] have been prevented? |

| 22. What other aspect do you consider significant for DRM-TDF that has not been addressed during the interview, particularly regarding community participation? |

References

- UNISDR—The United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction. Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015–2030; UNISDR: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- UNDRR—UN Office for Disaster Risk Reduction. Report of the Open-Ended Intergovernmental Expert Working Group on Indicators and Terminology Relating to Disaster Risk Reduction. Report No.: A/71/644. 2016, p. 41. Available online: https://www.preventionweb.net/files/50683_oiewgreportenglish.pdf?startDownload=true (accessed on 23 January 2023).

- Vieira, M.S.; Alves, R.B. Interlocução das Políticas Públicas Ante a Gestão de Riscos de Desastres: A Necessidade da Intersetorialidade. Saúde Debate 2021, 44, 132–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valencio, N. Desastres, ordem social e planejamento em defesa civil: O contexto brasileiro. Saúde Soc. 2010, 19, 748–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birkmann, J. Risk and vulnerability indicators at different scales:Applicability, usefulness and policy implications. Environ. Hazards 2007, 7, 20–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leone, F. Caractérisation des Vulnérabilités aux Catastrophes “Naturelles”: Contribution à Une Evaluation Géographique Multirisque (Mouvements de Terrain, Séismes, Tsunamis, Eruptions Volcaniques, Cyclones). Université Paul Valéry-Montpellier III. 2007. Available online: https://hal.science/tel-00276636/ (accessed on 7 January 2025). (In France).

- Bowker, L.N.; Chambers, D.M. The risk, public liability, & economics of tailings storage facility failures. Earthwork Act 2015, 24, 1–56. [Google Scholar]

- IBAMA—Instituto Brasileiro do Meio Ambiente e dos Recursos Naturais Renováveis. Impactos Ambientais Decorrentes do Desastre Envolvendo o Rompimento da Barragem de Fundão, em Mariana, Minas Gerais; IBAMA: Minas Gerais, Brazil, 2015; p. 38. Available online: https://ambientedomeio.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/laudo-preliminar-do-ibama-sobre-mariana.pdf (accessed on 15 September 2022).

- BRASIL. Ministério da Economia. Rompimento da barragem B I da Vale S.A. em Brumadinho/MG em 25/01/2019. Minas Gerais. 2025; p. 240. Available online: https://www.gov.br/trabalho-e-emprego/pt-br/assuntos/inspecao-do-trabalho/seguranca-e-saude-no-trabalho/acidentes-de-trabalho-informacoes-1/relatorio_analise_acidentes_brumadinho.pdf (accessed on 4 March 2025).

- Azam, S.; Li, Q. Tailings Dam Failures: A Review of the Last One Hundred Years. Geotech. News 2010, 28, 50–54. Available online: https://ksmproject.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/Tailings-Dam-Failures-Last-100-years-Azam2010.pdf (accessed on 7 January 2025).

- Freitas, C.M.D.; Silva, M.A.D.; Menezes, F.C.D. O desastre na barragem de mineração da Samarco: Fratura exposta dos limites do Brasil na redução de risco de desastres. Ciênc. Cult. 2016, 68, 25–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Freitas, C.M.D.; Barcellos, C.; Asmus, C.I.R.F.; Silva, M.A.D.; Xavier, D.R. Da Samarco em Mariana à Vale em Brumadinho: Desastres em barragens de mineração e Saúde Coletiva. Cad. Saúde Pública 2019, 35, e00052519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Melo, T.L.; De Oliveira Guimarães, L.; Cortese, T.T.P.P. Disaster governance and the role of civil society: A study of the mining disaster in Brumadinho, Brazil. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2024, 114, 104945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ANM—Agência Nacional de Mineração. SIGBM. Sistema Integrado de Gestão de Barragens de Mineração. 2025. Available online: https://app.anm.gov.br/sigbm/publico (accessed on 5 November 2022).

- Maia, J.G.V. A Importância do Componente Cívico Para o Funcionamento Efetivo de Canais Participativos Como Instrumentos de Inclusão Democrática: Um Estudo de Caso dos Comitês Gestores de Bairro do Programa Nova Baixada. Ph.D. Thesis, Fundação Getúlio Vargas, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 2006. Available online: https://bibliotecadigital.fgv.br/dspace/handle/10438/3644 (accessed on 26 December 2024).

- Guaraná, J.; Fleury, S. Gestão participativa como instrumento de inclusão democrática: O caso dos comitês gestores de bairro do programa nova baixada. Rev. Adm. Empresas 2008, 48, 94–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clemente, M.P.; Pinto, A.G.A.; Martins, A.K.L. Gestão participativa na Estratégia Saúde da Família: Reorientação da demanda à luz do Método Paideia. Saúde Debate 2021, 45, 315–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IBGE—Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística. Cidades e Estados: Conceição do Mato Dentro (MG). 2025. Available online: https://cidades.ibge.gov.br/brasil/mg/conceicao-do-mato-dentro/panorama (accessed on 4 March 2025).

- Lara, M.S.; Lobo, C. A Atividade Minerária e a Dinâmica Demográfica/Econômica em Conceição do Mato Dentro (MG). Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais: Minas Gerais, Brazil. 2016. Available online: https://periodicos.pucminas.br/index.php/geografia/article/view/p.2318-2962.2016v26n47p759/10138 (accessed on 29 October 2022).

- Comitê Brasileiro de Brarragens. A História das Barragens no Brasil, Séculos XIX, XX e XXI: Cinquenta Anos do Comitê Brasileiro de Barragens; CBDB: Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 2011; 533p. [Google Scholar]

- Pereira, G.M. História das usinas hidrelétricas. RBGEA 2021, 11, 117–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anglo American. Projeto Minas Rio. Minário de Ferro. Available online: https://brasil.angloamerican.com/pt-pt/nossos-negocios/minerio-de-ferro (accessed on 4 March 2025).

- UFMG—Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais. Comunidades de Conceição do Mato Dentro Lutam Contra Mineradora Anglo American por Reassentamento Justo. Available online: https://conflitosambientaismg.lcc.ufmg.br/noticias/comunidades-de-conceicao-do-mato-dentro-lutam-contra-mineradora-anglo-american-por-reassentamento-justo/? (accessed on 22 November 2024).

- TJMG—Tribunal de Justiça do Estado de Minas Gerais. Comarca de Conceição do Mato Dentro Homologa Acordo que Beneficia 400 Famílias. Available online: https://www.tjmg.jus.br/portal-tjmg/noticias/comarca-de-conceicao-do-mato-dentro-homologa-acordo-que-beneficia-400-familias.htm?# (accessed on 18 December 2024).

- NACAB—Núcle de Assessoria às Comunidades Atingidas por Barragens. Projeto de Assessoria Técnica Independente (ATI 39). 2020. Available online: https://nacab.org.br/ati-39-2/ (accessed on 5 November 2023).

- TRF6—Trinunal Regional Federal da 6a Região. Sentença Sobre a Tragédia da Barragem de Fundão é Destaque na TV Justiça. 2024. Available online: https://portal.trf6.jus.br/sentenca-sobre-a-tragedia-da-barragem-de-fundao-e-destaque-na-tv-justica/ (accessed on 5 November 2024).

- Leone, F. Concept de Vulnérabilité Appliqué à L’évaluation des Risques Générés par les Phénomènes de Mouvements de Terrain, Orléans; Université Grenoble: Grenoble, France, 1996; Available online: https://theses.hal.science/tel-00721876/ (accessed on 2 October 2024).

- Mendes, J.M.; Tavares, A.O.; Cunha, L.; Freiria, S. A vulnerabilidade social aos perigos naturais e tecnológicos em Portugal. Rev. Crítica Ciências Sociais 2011, 93, 95–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wisner, B. Vulnerability as Concept, Model, Metric, and Tool. In Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Natural Hazard Science; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2016; Available online: http://naturalhazardscience.oxfordre.com/view/10.1093/acrefore/9780199389407.001.0001/acrefore-9780199389407-e-25 (accessed on 12 January 2025).

- Zêzere, J.L. Relatório do Programa de Perigosidade, Vulnerabilidade e Riscos no Território: Aplicação aos Movimentos de Vertente; Biblioteca do IGOT: Universidade de Lisboa, Instituto de Geografia e Ordenamento Territorial: Lisbon, Portugal, 2010; p. 132. [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira, E.L.D.A. Vulnerabilidade: A questão central da equação de risco. Geogr. Ensino Pesqui. 2018, 22, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roque, M.P. Social vulnerability to environmental disasters in the Paraopeba River Basin, Minas Gerais, Brazil. Nat. Hazards 2023, 118, 1191–1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuchs, S.; Birkmann, J.; Glade, T. Vulnerability assessment in natural hazard and risk analysis: Current approaches and future challenges. Nat. Hazards 2012, 64, 1969–1975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owen, J.R.; Kemp, D.; Lèbre, É.; Svobodova, K.; Pérez Murillo, G. Catastrophic tailings dam failures and disaster risk disclosure. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2020, 42, 101361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Füssel, H.M. Vulnerability: A generally applicable conceptual framework for climate change research. Glob. Environ. Change 2007, 17, 155–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BRASIL. Política Nacional de Direitos das Populações Atingidas por Barragens. Lei N° 14755 15 December 2023. Available online: https://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/_ato2023-2026/2023/lei/L14755.htm (accessed on 20 January 2025).

- BRASIL. Política Nacional de Proteção e Defesa Civil (PNPDEC). Lei N° 12608 10 April 2012. Available online: https://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/_ato2011-2014/2012/lei/l12608.htm (accessed on 20 January 2025).

- BRASIL. Aprimorar os Instrumentos de Prevenção de Acidentes ou Desastres e de Recuperação de Áreas por Eles Atingidas. Lei N° 14750 12 December 2023. Available online: https://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/_ato2023-2026/2023/lei/l14750.htm (accessed on 20 January 2025).

- Conceição do Mato Dentro. Plano de Contingência de Proteção e Defesa Civil de Conceição do Mato Dentro (MG); Prefeitura Municipal: São João del-Rei, Brazil, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Anglo American. Plano de Ação de Emergências para Barragens de Mineração (PAEBM). 2025. Available online: https://brasil.angloamerican.com/pt-pt/barragem/paebms (accessed on 15 January 2023).

- IBRAM—Instituto Brasileiro de Mineração. Gestão e Manejo de Rejeitos da Mineração; IBRAM: Brasília, Brazil, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- BRASIL. Política Nacional de Segurança de Barragens. Lei N° 12334 20 September 2010. Available online: https://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/_ato2007-2010/2010/lei/l12334.htm (accessed on 20 January 2025).

- BRASIL. Compensação financeira pela exploração de recursos minerais e outros. Lei N° 7990 28 December 1989. Available online: https://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/leis/l7990.htm (accessed on 7 January 2025).

- BRASIL. Indústrias Nucleares do Brasil S.A. (INB), Sobre a Pesquisa, a Lavra e a Comercialização de Minérios Nucleares, de Seus Concentrados e Derivados, e de Materiais Nucleares, e Sobre a Atividade de Mineração. Lei N° 14514 29 December 2022. Available online: https://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/_ato2019-2022/2022/lei/L14514.htm (accessed on 12 December 2024).

- BRASIL. Política Nacional do Meio Ambiente. Lei N° 6938 31 August 1981. Available online: https://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/leis/l6938.htm (accessed on 12 December 2024).

- BRASIL. Dispõe Sobre a Revisão e Complementação dos Procedimentos e Critérios Utilizados Para o Licenciamento Ambiental. RESOLUÇÃO CONAMA n° 237 19 December 1997. Available online: https://conama.mma.gov.br/?option=com_sisconama&task=arquivo.download&id=237 (accessed on 12 December 2024).

- BRASIL. Proteção da Vegetação Nativa. Lei N° 12651 12 May 2012. Available online: https://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/_ato2011-2014/2012/lei/l12651.htm (accessed on 12 December 2024).

- BRASIL. Dispõe Sobre as Sanções Penais e Administrativas Derivadas de Condutas e Atividades Lesivas ao Meio Ambiente, e dá Outras Providências. Lei N° 9605 12 February 1998. Available online: https://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/leis/l9605.htm (accessed on 12 December 2024).

- BRASIL. Estatuto das Cidades. Lei N° 10257 10 July 2001. Available online: https://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/leis/leis_2001/l10257.htm (accessed on 12 December 2024).

- Guimarães, V.D.O.G.; Castro, P.M.G.D.; Petesse, M.L.; Ferreira, C.M. Mining disaster in Brumadinho (Brazil): Social vulnerability from the perspective of the fisherman community. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2024, 112, 104814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, R.; Mugi, S.R.; Saleh, J.H. Accident investigation and lessons not learned: AcciMap analysis of successive tailings dam collapses in Brazil. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2023, 236, 109308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armada, C.A.S. Os desastres ambientais de Mariana e Brumadinho em face ao estado socioambiental brasileiro. Territorium 2021, 28, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blaikie, P.; Cannon, T.; Cannon, T.; Wisner, B. At Risk: Natural Hazards, People’s Vulnerability and Disasters, 2nd ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2014; 496p. [Google Scholar]

- Cutter, S.L.; Boruff, B.J.; Shirley, W.L. Social vulnerability to environmental hazards. Soc. Sci. Q. 2003, 84, 242–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villagrán de León, J.C. Vulnerability: A Conceptual and Methodological Review; United Nations University Institute for Environment and Human Security: Bonn, Germany, 2006; 64p. [Google Scholar]

- Beck, U. Sociedade de Risco; Editora: São Paulo, Brazil, 2010; Volume 34, pp. 49–53. Available online: https://www.academia.edu/download/57261018/Bueno_2011__Entrevista_Ulrich_Beck_-_Sociedade_de_risco.pdf (accessed on 20 January 2025).

- De Paiva, C.A.; Barella, C.F.; Fonseca, A. Assessing and managing safety risks to downstream communities (in hindsight): What went wrong in the licensing and impact assessment procedures of Brazil’s deadliest dam breaks? Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2024, 106, 107536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freitas, C.M.; Silva, M.A.D. Acidentes de trabalho que se tornam desastres: Os casos dos rompimentos em barragens de mineração no Brasil. Rev. Bras. Med. Trab. 2019, 17, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsuo, P.M.; Souza, S.A.d.O.e.; Silva, R.L.F.; Trajber, R. Redução de riscos de desastres na produção sobre educação ambiental: Um panorama das pesquisas no Brasil. Pesqui. Educ. Ambient. 2019, 14, 57–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lumbroso, D.; McElroy, C.; Goff, C.; Collell, M.R.; Petkovsek, G.; Wetton, M. The potential to reduce the risks posed by tailings dams using satellite-based information. The potential to reduce the risks posed by tailings dams using satellite-based information. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2019, 38, 101209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CMD—Conceição do Mato Dentro. Plano Diretor Participativo do Município de Conceição do Mato Dentro. N°—101/2020. 2020. Available online: https://leismunicipais.com.br/plano-diretor-conceicao-do-mato-dentro-mg (accessed on 11 January 2025).

- CMD—Conceição do Mato Dentro. Plano Municipal de Saneamento Básico de Conceição do Mato Dentro (MG). LEI N° 2.191/2017. 2017. Available online: https://leismunicipais.com.br/a/mg/c/conceicao-do-mato-dentro/lei-ordinaria/2017/220/2191/lei-ordinaria-n-2191-2017-institui-o-plano-municipal-de-saneamento-basico-pmsb-e-da-outras-providencias (accessed on 11 January 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).