Abstract

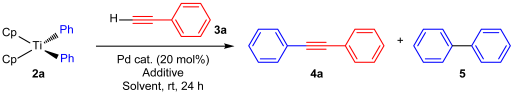

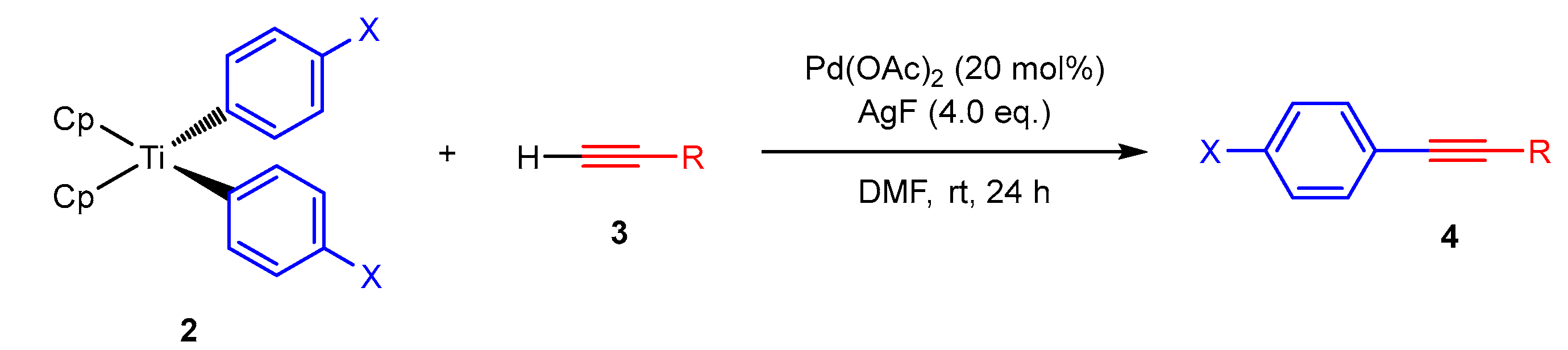

Organotitanium compounds find application in diverse reactions, including carbon–carbon bond formation and oxidation. While titanium (IV) compounds have been used in various applications, the potential of bis(cyclopentadienyl)diaryltitanium in cross-coupling reactions remains unexplored. This study focuses on Sonogashira-type cross-coupling reactions involving terminal alkynes and organotitanium compounds. Diaryltitanocenes were synthesized using titanocene dichloride with lithium intermediates derived from aryl iodide. Under open-flask conditions, reactions of diphenyltitanocenes with ethynylbenzene in the presence of 20 mol% Pd(OAc)2 in DMF produced coupling products in a remarkable 99% yield. Various diaryltitanocenes and alkynes under standard conditions yielded corresponding cross-coupling products with moderate to good yields. Notably, the Sonogashira-type alkynylation proceeds under mild conditions, including open-flask conditions, and without the need for a base. Furthermore, this cross-coupling is atom-economical and involves the active participation of both aryl groups of the diaryltitanocene. Remarkably, this study presents the first example of a Sonogashira-type cross-coupling using titanium compounds as pseudo-halides.

1. Introduction

The chemical reactivity of organotitanium compounds has received considerable attention. Organotitanium compounds are used in various applications, including carbon–carbon bond formation and oxidation reactions [1,2,3,4]. Among these, aryltitanium (IV) alkoxides [ArTi(OR)3] have been shown to act as transmetallating agents, that is, nucleophiles, in cross-coupling reactions with halides using Pd and Ni catalysts [5,6,7,8,9,10]. For example, Hayashi et al. reported that the cross-coupling reaction of 2-naphthyl triflate and ArTi(i-PrO)3 using catalyst systems of [Pd(C3H5)Cl]2 and phosphine ligands affords biaryls [5]. Gau et al. developed a reaction in which a benzyl halide was reacted with PhTi(i-PrO)3 using a Pd(OAc)2/P(p-Tol)3 system to produce the corresponding 1-benzyl-4-arylbenzenes [8]. However, the application of bis(cyclopentadienyl)diaryltitanium (Ar2TiCp2: diaryltitanocene) in cross-coupling reactions has not yet been reported.

The Sonogashira reaction is an important cross-coupling reaction used in the synthesis of natural products, biologically active compounds, and pharmaceutical intermediates [11,12,13,14]. The conventional protocol for this reaction involves the reaction of a terminal alkyne with an aryl halide or triflate as an electrophile in the presence of a Pd-phosphine complex as a catalyst and Cu salt as a co-catalyst, with a high quantity of amine as the solvent and base under an inert atmosphere. Over the past four decades, various modifications of the Sonogashira reaction have been developed. Among these, aryl donors containing typical elements, such as boron, silicon, phosphorus, antimony, bismuth, sulfur, tellurium, and iodine, have been reported to behave as alternative aryl halides and triflates as electrophilic partners in Sonogashira-type reactions [15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26].

In 2003, Zou et al. conducted a procedure for constructing internal alkynes via the cross-coupling reaction of terminal alkynes and arylboronic acids catalyzed by a Pd(dppf)Cl2-AgO system in the presence of excess K2CO3 as the base [15]. Since then, this type of reaction, with arylboronic acids and silver reagents as oxidants, has attracted considerable attention, and several groups reported improved methods [16,17,18,19]. Recently, Zhu et al. developed the reaction of terminal alkynes with hypervalent aryl iodonium salts using a PdCl2-AgI system and triethylamine [20]. Cheng et al. conducted aryl trimethoxysilanes as useful arylating agents using the Pd(dppf)Cl2-AgF system in the presence of NaHCO3 [21]. Moreover, triarylbismuthines act as arylating agents in systems comprising Pd(OAc)2-AgF and K3PO4 systems [22]. However, the Sonogashira-type reactions of terminal alkynes with organotitanium compounds under open-flask conditions have not yet been examined. Inspired by this knowledge and our continuing studies regarding this novel Sonogashira-type reaction, we present a Pd-catalyzed C(Ar)–C(sp) bond formation using silver salt and terminal alkynes, with Ar2TiCp2 as pseudo-halides, that is, electrophiles, without a base.

2. Results and Discussion

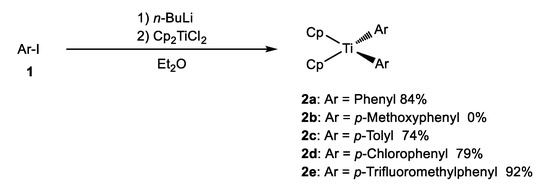

2.1. Synthesis of Bis(cyclopentadienyl)diaryltitanium

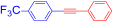

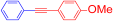

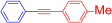

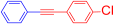

Bis(cyclopentadienyl)diaryltitanium 2 was synthesized according to the procedures specified in previous reports [27,28]. Aryl iodide 1 was treated with 1.0 equivalents of n-butyllithium in dry ether under an argon atmosphere at −30 °C, followed by dichlorobis(cyclopentadienyl)titanium (Cp2TiCl2), thus resulting in the formation of 2a–e in good-to-excellent yields (Scheme 1). Unfortunately, the use of the methoxy derivative, with a stronger electron-donating group on its benzene ring compared to the methyl group, yielded only a complex mixture, not 2b. The resulting products, whose color ranged from yellowish to dark red, were crystalline compounds that were stable at room temperature in air.

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of bis(cyclopentadienyl)diaryltitanium.

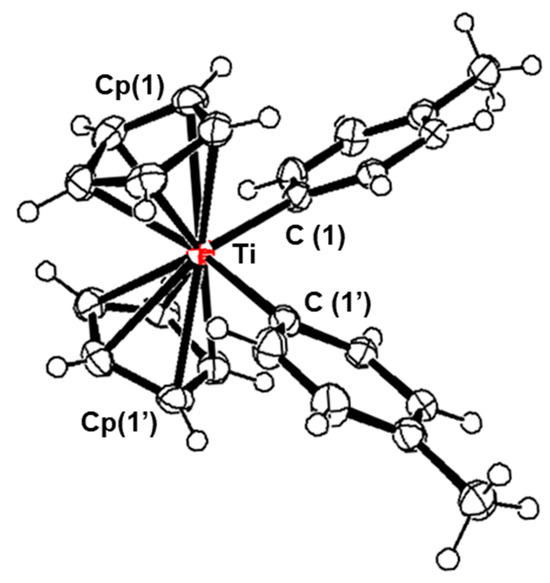

2.2. Molecular Structures of 2c

Figure 1 shows the crystal structure of 2c, and Table 1 lists the selected bond lengths and angles. The two cyclopentadienyl rings were π-bonded to titanium with an average Ti–C distance of 2.392 Å, which corresponds to the length reported for Ph2TiCp2 (2.31 Å) [29]. The C–C bond lengths in the cyclopentadienyl rings were also approximately the same as those of Ph2TiCp2, which varied from 1.397 to 1.411 Å with an average C–C bond length of 1.402 Å. The two aryl rings were σ-bonded to a titanium atom, with an average Ti–C distance of 2.21 Å. These lengths were similar to the distance of Ph2TiCp2 (2.27 Å). The arrangement of the four ligands on titanium was pseudotetrahedral, with C (1) –Ti–C (1′), C (1)–Ti–Cp (1) (center), and C (1′) –Ti–Cp (1) (center) bond angles of 98.66°, 102.44°, and 108.18°, respectively.

Figure 1.

Molecular structures of 2c with 50% probability thermal ellipsoids.

Table 1.

Selected bond lengths (Å) and bond angles (°) for 2c.

2.3. Cross-Coupling Reactions of Diaryltitanocenes with Terminal Alkynes

First, the optimal experimental conditions were determined for cross-coupling using diphenyltitanocene (2a) and phenylacetylene (3a) as model substrates. Table 2 lists the results of the screening of suitable catalysts, additives, and solvents. We first reacted 2a (0.25 mmol) with 3a (0.5 mmol) using various Pd catalysts (20 mol%) and AgF (4.0 eq.) in DMF at room temperature under open-flask conditions for 24 h (entries 1–5). This reaction could be performed with any of the Pd(II) and Pd(0) catalysts, among which Pd(OAc)2 provided the best yield of diphenylethyne 4a (entry 1). In the screening of additives, such as silver reagents and CsF, only AgF exhibited high reactivity (entries 1 and 7–10). Pd(OAc)2 and AgF were essential for this reaction, and the reaction did not proceed without their additions (entries 6 and 11). Solvent screening revealed that the reaction proceeded in DMF, DMA, DMSO, NMP, CH3CN, and CH3OH (entries 1 and 12–16), with DMF offering the best yield (entry 1). By contrast, THF, CH2Cl2, and toluene were inefficient reaction solvents (entries 17–19). When the reactions were performed under argon and oxygen atmospheres, the yield of the coupling product 4a was lower than that obtained under open-flask conditions (entries 1, 20, and 21). Decreasing the loading of Pd(OAc)2 from 20 to 10 mol% resulted in a significantly lower yield of 4a (20% yield, entry 22), thus suggesting that the reaction was sensitive to catalyst loading. Consequently, the optimal result was obtained when 2a was treated with 2.0 equivalents of alkyne 3a and 4.0 equivalents of AgF under open-flask conditions at room temperature (entry 1). The results obtained under these optimum conditions indicate that the two phenyl groups on the titanium atom of 2a are utilized in the reaction.

Table 2.

Reaction screening of diphenyltitanocene 2a with phenylacetylene 3a a.

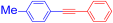

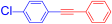

Under the optimal identified reaction conditions for this Sonogashira-type reaction, we examined the scope with respect to diaryltitanocene 2 (0.25 mmol) and terminal alkyne 3 (0.5 mmol). The results of these coupling reactions are listed in Table 3. The reaction of diaryltitanocene 2c–e with both electron-donating and electron-withdrawing groups on the aromatic ring with phenylacetylene 3a afforded the corresponding adducts 4b-d in good to moderate yields (55–76%). Then, diphenyltitanocene 2a was reacted with various terminal alkynes 3b–f to produce coupling products 4b–d and 4f, which were substituted with electron-donating or electron-withdrawing groups at the 4-position of the benzene ring, in 61–88% yields. However, contrary to the expectations, the corresponding 4e was not obtained using 4-ethynylanisole 3b. Sterically hindered acetylene compounds 3g and 3h with substituents at the ortho position of the benzene ring afforded products 4g and 4h without any difficulty. Terminal alkynes bearing vinyl 3i and alkyl 3j afforded products 4i and 4j, respectively, in fair yields. By contrast, the reaction of terminal alkyne 3k with a heteroaryl group, such as thiophene, produced the corresponding coupling product 4k in a low yield (34%), which did not confirm the effectiveness of this system.

Table 3.

Substrate scope of coupling reactions between 2 and 3 a,b.

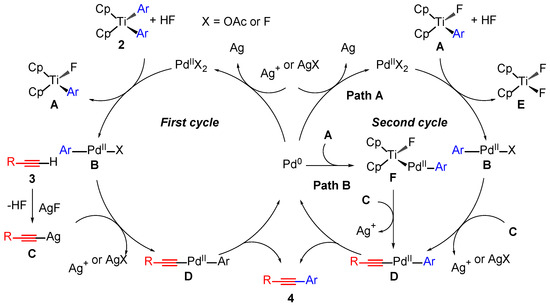

The mechanism of the Sonogashira-type reaction with diaryltitanocenes 2 is currently unclear. We considered mechanisms similar to those described in our previous study [22]. Plausible mechanisms for the reaction between terminal alkynes and diaryltitanocenes in the formation of internal alkynes are shown in Scheme 2. The first step of the reaction was the transmetallation between diaryltitanocene (2) and the PdIIX2 catalyst to form intermediates A and B. Silver acetylide C and HF were formed from terminal alkyne 3 and AgF. A second transmetallation of B with silver acetylide C afforded intermediate D, which underwent a reductive elimination to form coupling product 4 and a Pd0 species. The Pd0 species was oxidized by the silver cation or AgX to regenerate PdII (Scheme 2, first cycle). Subsequently, the ligand-exchange reaction of intermediate A with the PdIIX2 catalyst generated intermediate B, followed by the reaction of B with C to afford D. Intermediate D was converted to 4 via a reductive elimination (Scheme 2, second cycle). Another route in the second cycle is possible, in which the oxidative addition of A to Pd0 affords PdII intermediate F.

Scheme 2.

Plausible reaction mechanism.

3. Conclusions

In conclusion, diaryltitanocenes are a new class of arylating reagents for Sonogashira-type coupling reactions under open-flask conditions. This is the first example of the use of bis(cyclopentadienyl)diaryltitanium as a pseudo-halide in a cross-coupling reaction. The reaction proceeded without a base and all aryl groups on the titanium reagent participated in the reaction. The reaction afforded the corresponding cross-coupling products in satisfactory yields, even with diaryltitanocenes and terminal alkynes. On the other hand, the synthesis of diaryltitanocenes with strong electron-donating groups, such as methoxy groups, on the phenyl rings is challenging, leaving room for improvement as a general synthetic method. The Sonogashira-type reactions using diaryltitanocenes were also more electronically sensitive than the reported reactions of compounds containing typical elements, such as arylboronic acids and triarylbismuthines, with various acetylene derivatives. The studies on the mechanism of this reaction and the reactions of diaryltitanocenes with other coupling partners are ongoing.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. General Information

All reagents and solvents were purchased from commercial suppliers and used without further purification. 1H nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR, trimethylsilane: δ 0.00 ppm or CHCl3: δ 7.26 ppm as an internal standard) and 13C NMR (CDCl3: δ 77.0 ppm as an internal standard) spectroscopy were conducted using an ECZ-400S (400 and 100 MHz, respectively) spectrometer (JEOL, Zhubei, China). Melting points, which were uncorrected, were measured using a micro-melting-point hot stage apparatus (Yanagimoto, Yokohama, Japan). Gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS) (electron ionization (EI)) was performed using a 5977E Diff-SST MSD-230V spectrometer (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA), and elemental analyses were performed on an MT-5 elemental analyzer (Yanagimoto, Yokohama, Japan). Infrared (IR) spectroscopy was conducted using an FTIR-8400S (Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan), and the spectra were reported in the frequency of absorption (cm−1) with only selected IR absorbencies reported. All chromatographic separations were performed using Silica Gel 60N (Kanto Chemical Co., Inc., Tokyo, Japan), and thin-layer chromatography (TLC) was performed using Sil G25 UV254 pre-coated TLC plates (Macherey-Nagel, Hoerdt, France).

4.2. Synthesis of Bis(cyclopentadienyl)diaryltitanium

To a solution of aryl iodide (20 mmol, 2.0 eq.) in anhydrous Et2O (10 mL), added n-BuLi (22 mmol, 1.56 M solution in hexane) at −30 °C. Stir the mixture for 1 h at room temperature. Add the resulting solution of ArLi dropwise to a solution of Cp2TiCl2 (10 mmol) in anhydrous Et2O (10 mL) at −30 °C. Warm the resulting solution −30 °C to room temperature before stirring for 16 h. The reaction mixture was slowly added to methanol (4.0 mL) at −30 °C. Filter the resulting solution and volatiles removed under a high vacuum to obtain bis(cyclopentadienyl)diaryltitanium. (Copies of 1H and 13C NMR see Supplementary Materials).

Diphenyltitanocene (2a) [27]. Light-yellow prisms (2.77 g, 84%), mp 146–148 °C (from CH2Cl2-Hexane), Rf = 0.4 (Hexane: AcOEt = 20:1). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ: 6.20 (10H, s, Cp-H), 6.88 (6H, d, J = 6.8 Hz, Ar-H), 6.97 (4H, t, J = 6.8 Hz, Ar-H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ: 115.9 (CH), 123.7 (CH), 126.5 (CH), 134.9 (CH), 191.1 (C). IR (KBr/cm−1) 1639, 1411, 1356, 1236, 1049, 1016, 815, 732, 702, 669. Anal. Calcd. for C22H20Ti: C, 79.5; H, 6.07, found: C, 79.4; H, 6.17.

Di-p-tolyltitanocene (2c) [27]. Dark-red prisms (2.66 g, 74%), mp 137–139 °C (from CH2Cl2-Hexane), Rf = 0.3 (Hexane: AcOEt = 20:1). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ: 2.22 (6H, s, CH3), 6.18 (10H, s, Cp-H), 6.78–6.79 (8H, m, Ar-H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ: 21.1 (CH3), 115.8 (CH), 127.2 (CH), 133.0 (C), 135.0 (CH), 187.7 (C). IR (KBr/cm−1) 1629, 1438, 1265, 1182, 1070, 1016, 810, 721, 669, 623. Anal. Calcd. for C24H24Ti: C, 80.0; H, 6.71, found: C, 80.2; H, 6.82.

Bis-4-chlorophenyltitanocene (2d) [30]. Orange powder (3.17 g, 79%), mp 59–61 °C (from CH2Cl2-Hexane), Rf = 0.4 (Hexane: AcOEt = 8:2). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ: 6.18 (10H, s, Cp-H), 6.76 (4H, d, J = 8.4 Hz, Ar-H), 6.92 (4H, d, J = 8.8 Hz, Ar-H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ: 116.2 (CH), 126.3 (CH), 129.9 (C), 136.2 (CH), 187.9 (C). IR (KBr/cm−1) 1654, 1585, 1483, 1089, 815, 717, 669. Anal. Calcd. for C22H18Cl2Ti: C, 65.9; H, 4.52, found: C, 65.6; H, 4.61.

Bis-4-(trifluoromethyl)phenyltitanocene (2e) [30]. Brown powder (4.31 g, 92%), mp 141–143 °C (from CH2Cl2-Hexane), Rf = 0.3 (Hexane: AcOEt = 8:2). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ: 6.22 (10H, s, Cp-H), 6.96 (4H, d, J = 7.6 Hz, Ar-H), 7.19 (4H, d, J = 7.9 Hz, Ar-H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ: 116.3 (CH), 122.6 (q, 3JC,F = 3.9 Hz, CH), 124.8 (q, 1JC,F = 269 Hz, C), 126.2 (q, 2JC,F = 31.6 Hz, C), 134.8 (CH), 195.6 (C). IR (KBr/cm−1) 1587, 1381, 1246, 1153, 1074, 1024, 1006, 827, 725, 667. Anal. Calcd. for C24H18F6Ti: C, 61.6; H, 3.87, found: C, 61.7; H, 3.99.

4.3. Single-Crystal X-ray Diffraction Experiment of 2c

Single crystals of 2c were obtained from ethanol, and a suitable crystal was selected and analyzed using an XtaLAB Synergy Dualflex, HyPix diffractometer (Rigaku, Auburn Hills, MI, USA). The crystal was maintained at 100 K during the data collection. Using Olex2 (OlexSys) [31], the structure was solved with the ShelXT [32] structure solution program using intrinsic phasing. The structure of 2c was refined with the ShelXL [33] refinement package using a least squares minimization.

Crystal Data for 2c

C24H24Ti (M = 360.33 g/mol): orthorhombic, space group Pbcn (No. 60), a = 8.25760(10) Å, b = 12.4042(2) Å, c = 17.9027(3) Å, V = 1833.75(5) Å3, Z = 4, T = 100 K, μ(CuKα) = 3.942 mm−1, Dcalc = 1.305 g/cm3, 16514 reflections measured (9.882° ≤ 2Θ ≤ 154.368°), 1923 unique (Rint = 0.0467, Rsigma = 0.0250), which were used in all the calculations. The final R1 was 0.0330 (I > 2σ(I)) and wR2 was 0.0906 (all data). CCDC 2287849.

4.4. General Procedure for the Synthesis of 1,2-Disubtituted Alkyne

Cp2TiAr2 (0.25 mmol), arylacetylene (0.5 mmol), Pd(OAc)2 (11.2 mg, 0.05 mmol), and AgF (126 mg, 1.0 mmol) were added to 3.0 mL of anhydrous DMF. Then, the mixture was stirred at room temperature for 24 h. The conversions were confirmed by TLC and isolated yields were obtained after silica gel chromatography (eluting with hexane).

1,2-Diphenylacetylene (4a) [34]. Colorless prisms (87.5 mg, 98%), mp 62–63 °C (from ethanol), Rf = 0.5 (hexane). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ: 7.33–7.38 (6H, m, Ar-H), 7.52–7.55 (4H, m, Ar-H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ: 89.5 (C), 123.3 (C), 128.36 (CH), 128.44 (CH), 131.7 (CH). MS (EI) m/z (%): 178 (100, M+), 152 (11), 89 (6), 76 (7). IR (KBr) ν: 2247 (C≡C), 1599, 918 cm−1.

1-Methyl-4-(phenylethynyl)benzene (4b) [34]. Colorless plates (70.1 mg, 76% from 2c with 3a; 84.5 mg, 88% from 2a with 3c), mp 71–72 °C (from ethanol), Rf = 0.3 (hexane). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ: 2.37 (3H, s, CH3), 7.15 (2H, d, J = 8.0 Hz, Ar-H), 7.31–7.33 (3H, m, Ar-H), 7.41 (2H, d, J = 8.4 Hz, Ar-H), 7.51 (2H, dd, J = 8.0, 2.4 Hz, Ar-H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ: 21.7 (CH3), 88.8 (C), 89.7 (C), 120.3 (C), 123.6 (C), 128.2 (CH), 128.4 (CH), 129.2 (CH), 131.6 (CH), 131.7 (CH), 138.5 (C). MS (EI) m/z (%): 192 (100, M+), 165 (14), 115 (9), 95 (10). IR (KBr) ν: 2216 (C≡C), 1595, 916 cm−1.

1-Chloro-4-(phenylethynyl)benzene (4c) [35]. Colorless prisms (58.5 mg, 55% from 2d with 3a; 64.7 mg, 61% from 2a with 3d), mp 82–83 °C (from CH2Cl2-hexane), Rf = 0.5 (Hexane). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ: 7.31–7.36 (5H, m, Ar-H), 7.49 (2H, dt, J = 8.8, 2.4 Hz, Ar-H), 7.50–7.53 (2H, m, Ar-H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ: 88.4 (C), 90.4 (C), 121.9 (C), 123.0 (C), 128.5 (CH), 128.6 (CH), 128.8 (CH), 131.7 (CH), 132.9 (CH), 134.4 (C). MS (EI) m/z (%): 212 (100, M+), 176 (33), 151 (11), 88 (6). IR (KBr) ν: 2214 (C≡C), 1587, 910 cm−1.

1-(Phenylethynyl)-4-(trifluoromethyl)benzene (4d) [35]. Colorless prisms (89.5 mg, 73% from 2e with 3a; 77.5 mg, 63% from 2a with 3f), mp 95–98 °C (from ethanol), Rf = 0.5 (hexane). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ: 7.36–7.38 (3H, m, Ar-H), 7.52–7.56 (2H, m, Ar-H), 7.58–7.64 (4H, m, Ar-H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ: 88.1 (C), 91.9 (C), 122.6 (C), 124.0 (q, 1JC,F = 285 Hz, C), 125.4 (q, 3JC,F = 3.8 Hz, CH), 127.2 (C), 128.5 (CH), 128.9 (CH), 130.0 (q, 2JC,F = 32.6 Hz, C), 131.9 (CH), 132.9 (CH). MS (EI) m/z (%): 246 (100, M+), 227 (4), 176 (4), 98 (4). IR (KBr) ν: 2220 (C≡C), 1609, 845 cm−1.

1-Bromo-4-(phenylethynyl)benzene (4f) [35]. Colorless prisms (87.0 mg, 68%), mp 82–83 °C (from CH2Cl2-hexane), Rf = 0.5 (hexane). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ: 7.34–7.39 (5H, m, Ar-H), 7.46–7.53 (4H, m, Ar-H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ: 88.4 (C), 90.6 (C), 122.4 (C), 122.6 (C), 123.0 (C), 128.5 (CH), 128.6 (CH), 131.71 (CH), 131.74 (CH), 133.2 (CH). MS (EI) m/z (%): 256 (100, M+), 176 (61), 151 (22), 88 (17). IR (KBr) ν: 2214 (C≡C), 1597, 833 cm−1.

1-Methyl-2-(phenylethynyl)benzene (4g) [34]. Colorless oil (91.0 mg, 94%), Rf = 0.5 (hexane). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ: 2.52 (3H, s, CH3), 7.16–7.19 (1H, m, Ar-H), 7.23–7.26 (2H, m, Ar-H), 7.32–7.37 (3H, m, Ar-H), 7.50 (1H, d, J = 7.2 Hz, Ar-H), 7.53–7.56 (2H, m, Ar-H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ: 20.9 (CH3), 88.5 (C), 93.5 (C), 123.1 (C), 123.7 (C), 125.7 (CH), 128.3 (CH), 128.4 (CH), 128.5 (CH), 129.6 (CH), 131.6 (CH), 132.0 (CH), 140.3 (C). MS (EI) m/z (%): 192 (100, M+), 165 (33), 115 (19), 95 (15). IR (KBr) ν: 2214 (C≡C), 1601, 912 cm−1.

1,3,5-Trimethyl-2-(phenylethynyl)benzene (4h) [36]. Colorless needles (71.5 mg, 65%), mp 35–36 °C (from ethanol), Rf = 0.4 (hexane). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ: 2.30 (3H, s, CH3), 2.48 (6H, s, CH3), 6.89 (2H, s, Ar-H), 7.31–7.36 (3H, m, Ar-H), 7.52 (2H, dd, J = 8.4, 1.6 Hz, Ar-H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ: 21.2 (CH3), 21.5 (CH3), 87.5 (C), 97.2 (C), 120.1 (C), 124.2 (C), 127.7 (CH), 128.0 (CH), 128.5 (CH), 131.5 (CH), 137.9 (C), 140.3 (C). MS (EI) m/z (%): 220 (100, M+), 202 (76), 178 (5). IR (KBr) ν: 2211 (C≡C), 1595, 912 cm−1.

(Cyclohex-1-en-1-ylethynyl)benzene (4i) [34]. Colorless oil (50.0 mg, 55%), Rf = 0.4 (hexane). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ: 1.61–1.69 (3H, m, CH2), 2.11–2.16 (3H, m, CH2), 2.19–2.23 (2H, m, CH2), 6.19–6.22 (1H, m, CH), 7.24–7.31 (3H, m, Ar-H), 7.39–7.43 (2H, m, Ar-H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ: 21.7 (CH2), 22.5 (CH2), 25.9 (CH2), 29.4 (CH2), 86.9 (C), 91.4 (C), 120.8 (C), 123.9 (C), 127.8 (CH), 128.3 (CH), 131.6 (CH), 135.3 (CH). MS (EI) m/z (%): 182 (100, M+), 167 (61), 153 (60), 115 (43). IR (KBr) ν: 2201 (C≡C), 1597, 918 cm−1.

Hex-1-yn-1-ylbenzene (4j) [37] Colorless oil (38.4 mg, 48%), Rf = 0.5 (hexane). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ: 0.95 (3H, t, J = 7.2 Hz, CH3), 1.46–1.63 (4H, m, CH2 × 2), 2.41 (2H, t, J = 6.8 Hz, CH2), 7.26–7.29 (3H, m, Ar-H), 7.38–7.40 (2H, m, Ar-H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ: 13.8 (CH3), 19.3 (CH2), 22.2 (CH2), 31.0 (CH2), 80.7 (C), 90.5 (C), 124.2 (C), 127.6 (CH), 128.3 (CH), 131.7 (CH). MS (EI) m/z (%): 158 (34, M+), 143 (56), 115 (100), 89 (13). IR (KBr) ν: 2232 (C≡C), 1599, 912 cm−1.

2-(Phenylethynyl)thiophene (4k) [34]. Colorless needles (31.3 mg, 34%), mp 48–50 °C (from ethanol), Rf = 0.4 (hexane). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ: 7.01 (1H, dd, J = 5.2, 3.6 Hz, Ar-H), 7.27–7.29 (2H, m, Ar-H), 7.33–7.35 (3H, m, Ar-H), 7.49–7.52 (2H, m, Ar-H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ: 82.7 (C), 93.1 (C), 123.0 (C), 123.4 (C), 127.2 (CH), 127.4 (CH), 128.50 (CH), 128.54 (CH), 131.5 (CH), 132.0 (CH). MS (EI) m/z (%): 184 (100, M+), 152 (12), 139 (18), 126 (4). IR (KBr) ν: 2201 (C≡C), 1595, 853 cm−1.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/reactions4040037/s1. The crystal structures have been deposited into the CCDC with the number 2287849 and CIF files are also provided as Supplementary Materials.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed to the writing and provided approval to the final version of the manuscript. Y.M., M.M. and S.Y. designed the chemical synthesis, analyzed the results and wrote the manuscript. Y.N. and Y.M. performed the chemical synthesis experiments. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available in this article.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a research grant from the Institute of Pharmaceutical Life Sciences, Aichi Gakuin University. We would like to thank Takashi Matsumoto and Koichi Udoh (Rigaku corporation) for the single-crystal X-ray diffraction analysis.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Kulinkovich, O. Organotitanium and organozirconium reagents. In Comprehensive Organic Synthesis, 2nd ed.; Knochel, P., Molander, G.A., Eds.; Elsevier, B.V.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2014; pp. 124–158. [Google Scholar]

- Wolan, A.; Six, Y. Synthetic transformations mediated by the combination of titanium(IV) alkoxides and grignard reagents: Selectivity issues and recent applications. Part 1: Reactions of carbonyl derivatives and nitriles. Tetrahedron 2010, 66, 15–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, D.L. Applications of organotitanium reagents. Top. Organomet. Chem. 2004, 6, 37–61. [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi, T.; Yamasaki, K. Rhodium-catalyzed asymmetric 1,4-addition and its related asymmetric reactions. Chem. Rev. 2003, 103, 2829–2844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, J.W.; Tokunaga, N.; Hayashi, T. Palladium- or nickel-catalyzed cross-coupling of organotitanium reagents with aryl triflates and halides. Synlett 2002, 2002, 871–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manolikakes, G.; Dastbaravardeh, N.; Knochel, P. Nickel-catalyzed cross-coupling reactions of aryltitanium(IV) alkoxides with aryl halides. Synlett 2007, 2007, 2077–2080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.W.; Lam, F.L.; So, C.M.; Lau, C.P.; Chan, A.S.C.; Kwong, F.Y. Palladium-catalyzed cross-coupling of aryl halides using organotitanium nucleophiles. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2009, 48, 7436–7439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, C.-R.; Zhou, S.; Biradar, D.B.; Gau, H.-M. Extremely efficient cross-coupling of benzylic halides with aryltitanium tris(isopropoxide) catalyzed by low loadings of a simple palladium(II) acetate/tris(p-tolyl)phosphine system. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2010, 352, 1718–1727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.-H.; Liao, J.-W.; Huang, Y.-L.; Chiang, R.-T.; Gau, H.-M. Nickel-catalyzed substitution reactions of propargyl halides with organotitanium reagents. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2014, 12, 7634–7642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varenikov, A.; Gandelman, M. Organotitanium nucleophiles in asymmetric cross-coupling reaction: Stereoconvergent synthesis of chiral α-CF3 thioethers. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141, 10994–10999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonogashira, K.; Tohda, Y.; Hagihara, N. A convenient synthesis of acetylenes: Catalytic substitutions of acetylenic hydrogen with bromoalkenes, iodoarenes and bromopyridines. Tetrahedron Lett. 1975, 16, 4467–4470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Gao, S. Sonogashira coupling in natural product synthesis. Org. Chem. Front. 2014, 1, 556–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chinchilla, R.; Nájera, C. The Sonogashira reaction: a booming methodology in synthetic organic chemistry. Chem. Rev. 2007, 107, 874–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biajoli, A.F.P.; Schwalm, C.S.; Limberger, J.; Claudino, T.S.; Monteiro, A.L. Recent progress in the use of Pd-catalyzed C-C cross-coupling reactions in the synthesis of pharmaceutical compounds. J. Braz. Chem. Soc. 2014, 25, 2186–2214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, G.; Zhu, J.; Tang, J. Cross-coupling of arylboronic acids with terminal alkynes in air. Tetrahedron Lett. 2003, 44, 8709–8711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.; Wu, Y. Facile synthesis of substituted alkynes by cyclopalladated ferrocenylimine catalyzed cross-coupling of arylboronic acids/esters with terminal alkynes. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2007, 2007, 3476–3479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, M.-B.; Wei, W.-T.; Xie, Y.-X.; Lei, Y.; Li, J.-H. Palladium-catalyzed cross-coupling of electron-poor terminal alkynes with arylboronic acids under ligand-free and aerobic conditions. J. Org. Chem. 2010, 75, 5635–5642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nie, X.; Liu, S.; Zong, Y.; Sun, P.; Bao, J. Facile synthesis of substituted alkynes by nano-palladium catalyzed oxidative cross-coupling reaction of arylboronic acids with terminal alkynes. J. Organomet. Chem. 2011, 696, 1570–1573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, L.; Chellan, P.; Smith, G.S.; Zhang, X.; Yan, H.; Mao, J. Thiosemicarbazone salicylaldiminato palladium(II)-catalyzed alkynylation couplings between arylboronic acids and alkynes or alkynyl carboxylic acids. Tetrahedron 2014, 70, 5980–5985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, M.; Zhou, Z.; Chen, R. A novel Pd/Ag-catalyzed Sonogashira coupling reaction of terminal alkynes with hypervalent iodonium salts. Synthesis 2008, 17, 2680–2682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Z.; Liu, M.; Lin, B.; Wu, H.; Ding, J.; Cheng, J. Palladium-catalyzed cross-coupling reaction of aryl trimethoxysilanes with terminal alkynes. Tetrahedron Lett. 2009, 50, 530–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsumura, M.; Yamada, M.; Tsuji, T.; Murata, Y.; Kakusawa, N.; Yasuike, S. Palladium-catalyzed cross-coupling reactions of triarylbismuthanes with terminal alkynes under aerobic conditions. J. Organomet. Chem. 2015, 794, 70–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, L.K.; Na, Y.; Lee, J.; Do, Y.; Chang, S. Tetraarylphosphonium halides as arylating reagents in Pd-catalyzed Heck and cross-coupling reactions. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2005, 44, 6166–6169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Qin, W.; Kakusawa, N.; Yasuike, S.; Kurita, J. Copper- and base-free Sonogashira-type cross-coupling reaction of triarylantimony dicarboxylates with terminal alkynes under an aerobic condition. Tetrahedron Lett. 2009, 50, 6293–6297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshida, Y.; Nogi, K.; Yorimitsu, H. C–S Bond alkynylation of diaryl sulfoxides with terminal alkynes by means of a Palladium–NHC catalyst. Synlett 2017, 28, 2561–2564. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, S.; Ailneni, C.; Baqer, O.A.-M.; Lolla, M.; Mannava, B.B.; Siraswal, P.; Yen, C.; Jin, J. Diorganyl tellurides as substrates in Sonogashira coupling reactions under mild conditions. Synth. Commun. 2020, 50, 217–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Summers, L.; Uloth, R.H.; Holmes, A. Diaryl bis-(cyclopentadienyl)-titanium compounds. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1955, 77, 3604–3606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tung, H.-S.; Brubaker, C.H., Jr. Photochemical decomposition of (diphenyl)bis(η5-cyclopentadienyl) titanium, (diphenyl)bis(η5-pentamethylcyclopentadienyl) titanium and the zirconium analogs. Inorg. Chim. Acta 1981, 52, 197–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kocman, V.; Rucklidge, J.C.; O’Brien, R.J.; Santo, W. Crystal and molecular structure of (C5H5)2Ti(C6H5)2. J. Chem. Soc. D 1971, 21, 1340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beachell, H.C.; Butter, S.A. Nuclear magnetic resonance spectra of titanocene sandwich compounds. Inorg. Chem. 1965, 4, 1133–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolomanov, O.V.; Bourhis, L.J.; Gildea, R.J.; Howard, J.A.K.; Puschmann, H.J. OLEX2: A complete structure solution, refinement and analysis program. J. Appl. Cryst. 2009, 42, 339–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheldrick, G.M. SHELXT-Integrated space-group and crystal-structure determination. Acta Cryst. 2015, A71, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheldrick, G.M. Crystal structure refinement with SHELXL. Acta Cryst. 2015, C71, 3–8. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, K.L.; Kennedy, A.R.; Murray, J.; Greatrex, B.; Jamieson, C.; Watson, A.J.B. Scope and limitations of a DMF bio-alternative within Sonogashira cross-coupling and Cacchi-type annulation. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2016, 12, 2005–2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruengsangtongkul, S.; Chaisan, N.; Thongsornkleeb, C.; Tummatorn, J.; Ruchirawat, S. Rate Enhancement in CAN-promoted Pd(PPh3)2Cl2-catalyzed oxidative cyclization: Synthesis of 2-ketofuran-4-carboxylate esters. Org. Lett. 2019, 21, 2514−2517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Yang, F.; Wu, Y. Palladacycle-catalyzed decarboxylative coupling of alkynyl carboxylic acids with aryl chlorides under air. J. Org. Chem. 2013, 78, 4543–4550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alberto, G.-H.; Fady, N.; Jiufeng, W.; Frédéric, I.; Marcel, B.; Catherine, C.S.J.; Steven, P.N. Synthesis of di-substituted alkynes via palladium-catalyzed decarboxylative coupling and C-H activation. ChemistrySelect 2019, 4, 5–9. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).