Hall Sensor-Based Detection and Prevention of Seed Misses in Long-Belt Finger-Clip Precision Metering Device

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Long-Belt Finger-Clip Precision Seed Metering Devices

Overall Structure and Operational Principles

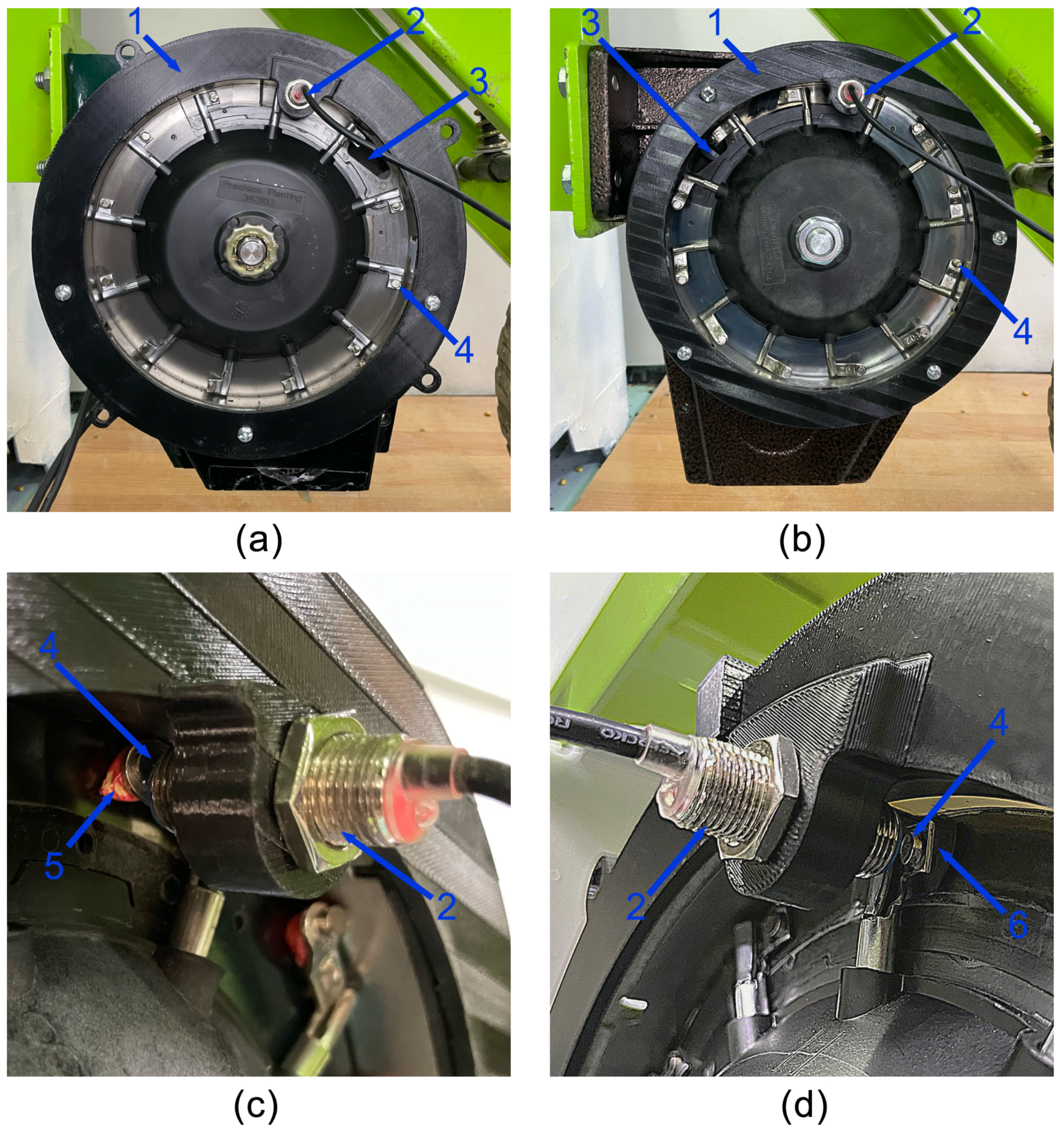

2.2. Retrofitting the Long-Belt Finger-Clip Precision Seed Metering Devices

2.2.1. Working Principle of Hall Sensor for Seed Miss Detection

2.2.2. Seed Miss Prevention System

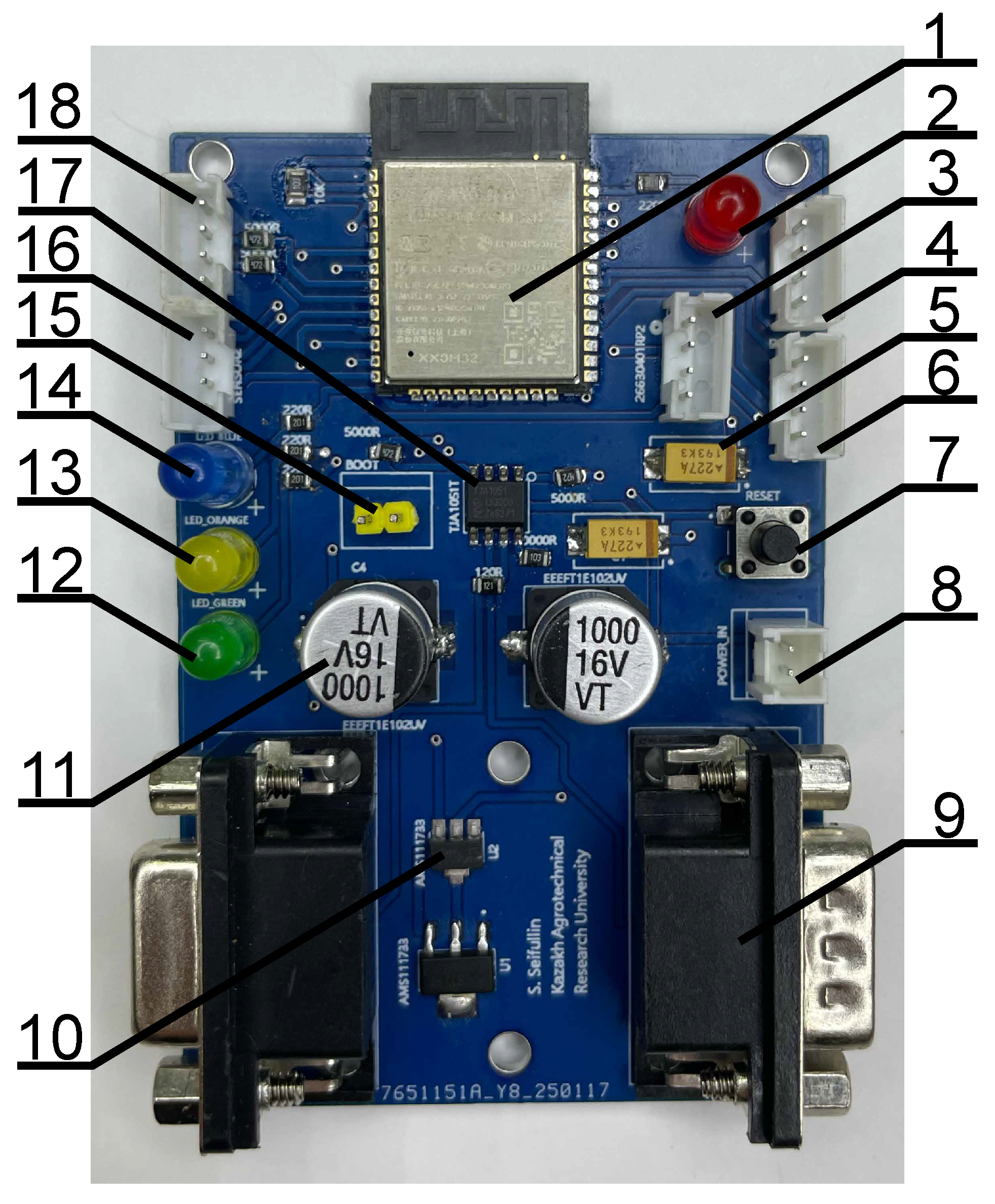

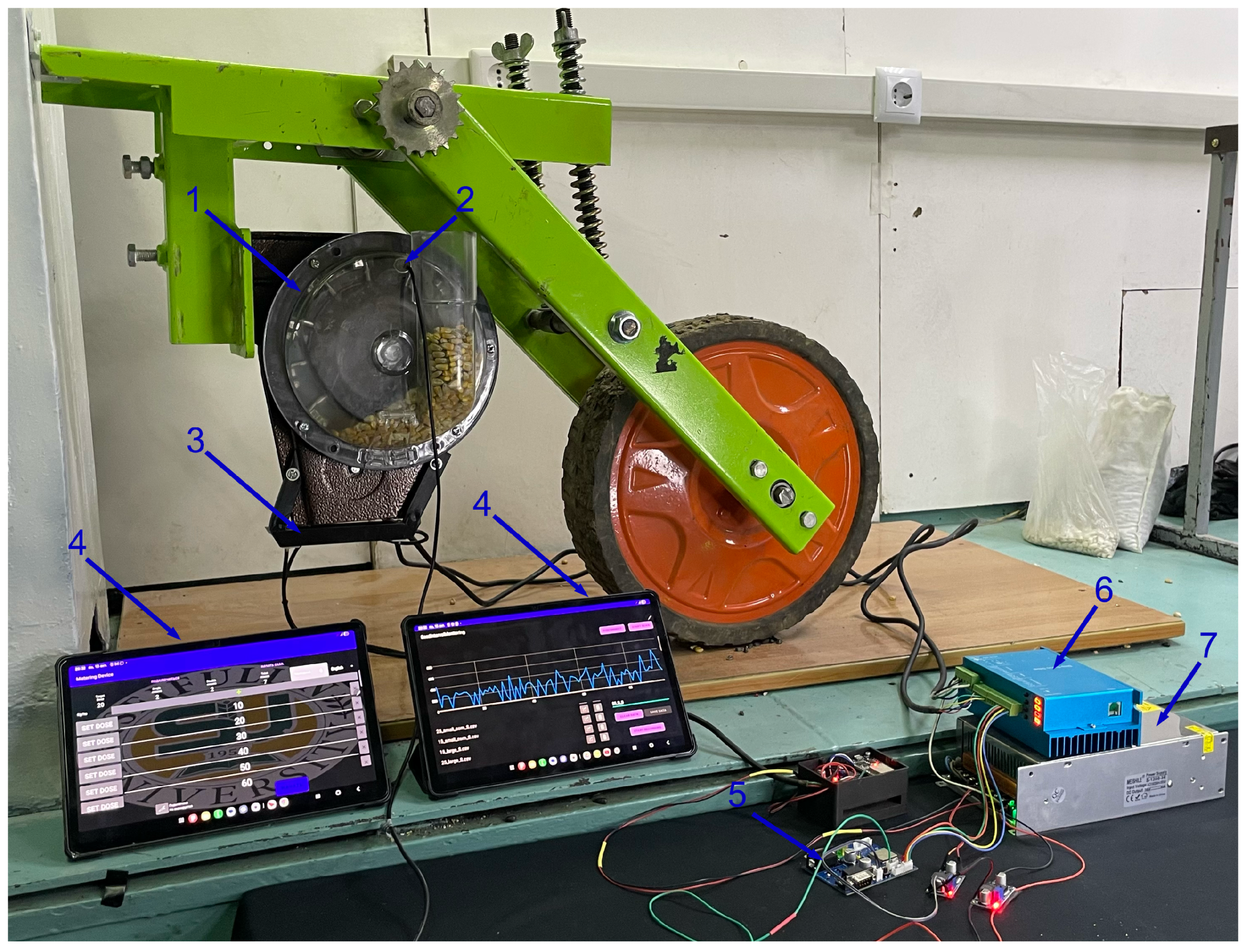

2.2.3. Control System Design and Data Acquisition

2.2.4. Retrofiring of the Device

2.3. Design Experiment

3. Results and Discussion

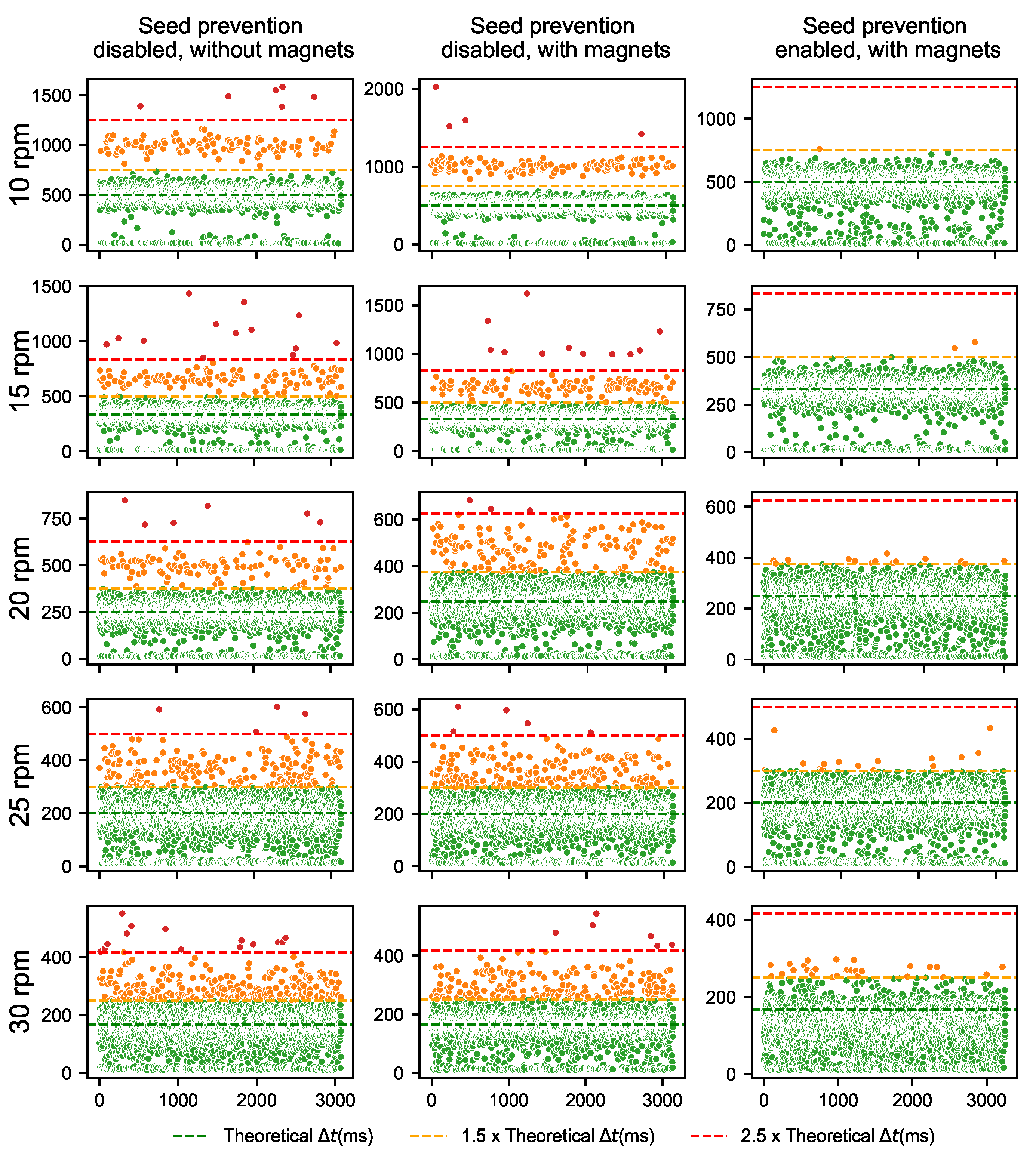

3.1. Experimental Framework and Core Performance Metrics

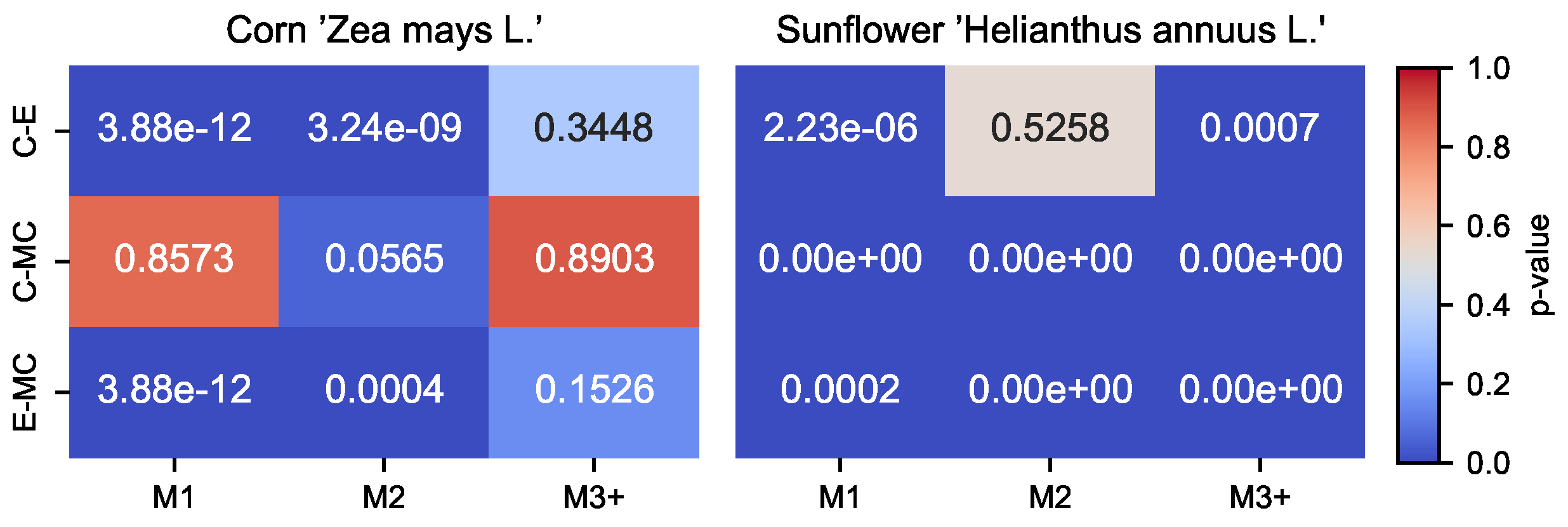

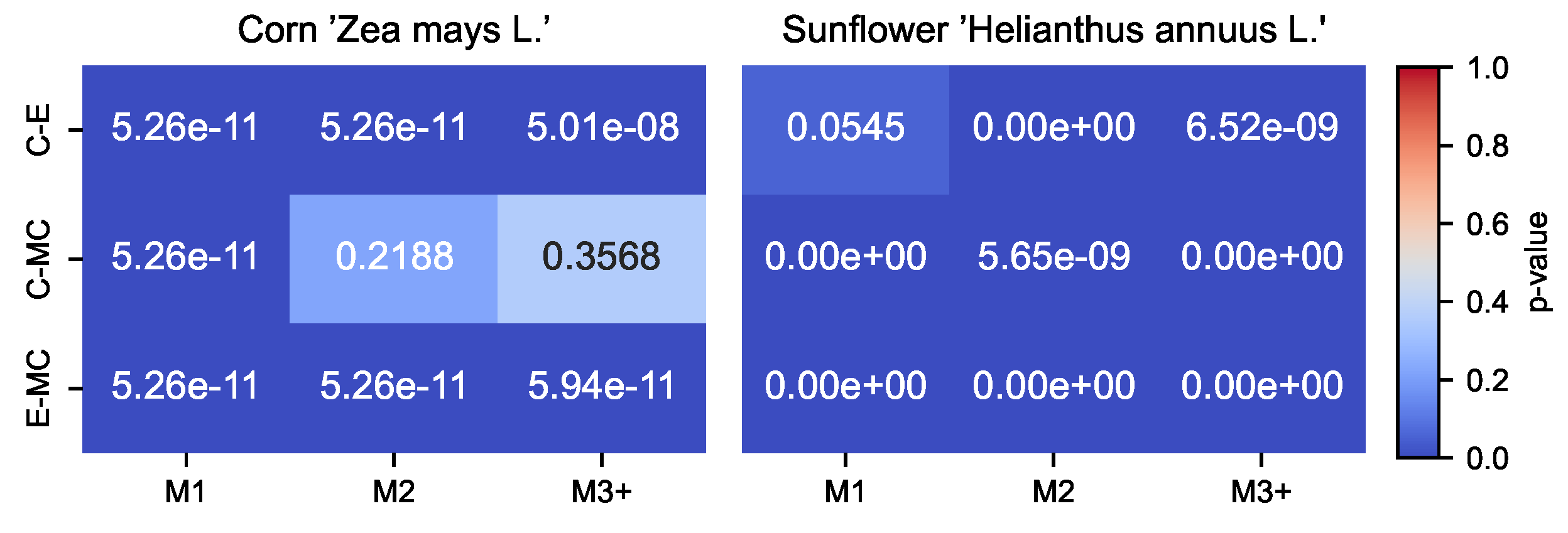

3.2. Singulation Efficacy and Miss Mitigation in Corn (‘Dekalb DKC5032’)

3.3. Singulation Efficacy and Miss Mitigation in Sunflower (‘Astana’)

3.4. Dynamic Signal Characterization from the Hall Sensor

3.5. Impact of Seed Morphology on Detection Reliability

4. Conclusions

5. Patents

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Pereyra, V.M.; Bastos, L.M.; de Borja Reis, A.F.; Melchiori, R.J.; Maltese, N.E.; Appelhans, S.C.; Vara Prasad, P.; Wright, Y.; Brokesh, E.; Sharda, A.; et al. Early-season plant-to-plant spatial uniformity can affect soybean yields. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 17128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhai, C.; Long, J.; Taylor, R.; Weckler, P.; Wang, N. Field scale row unit vibration affecting planting quality. Precis. Agric. 2020, 21, 589–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Xie, X.; Zheng, Z.; Wu, X.; Wang, W.; Chen, L. A plant unit relates to missing seeding detection and reseeding for maize precision seeding. Agriculture 2022, 12, 1634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimmelshue, C.L.; Goggi, A.S.; Moore, K.J. Single-plant grain yield in corn (Zea mays L.) based on emergence date, seed size, sowing depth, and plant to plant distance. Crops 2022, 2, 62–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celik, A.; Ozturk, I.; Way, T.R. Effects of various planters on emergence and seed distribution uniformity of sunflower. Appl. Eng. Agric. 2007, 23, 57–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zalai, M.; Bojtor, C.; Nagy, J.; Széles, A.; Monoki, S.; Illés, Á. Challenges in Precision Sunflower Cultivation: The Impact of the Agronomic Environment on the Quality of Precision Sowing Techniques and Yield Parameters. AgriEngineering 2025, 7, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olson, N.A.; Trostle, C.; Meyer, R.; Hulke, B.S. Canopy closure, yield, and quality under heterogeneous plant spacing in sunflower. Agron. J. 2024, 116, 2275–2283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yernaidu, Y.; Sreelatha, T.; Gosavi, S.V.; Tamminaina, S.K.; Nalabolu, V. Problems of Seed Setting and its Management in Sunflower. In Advanced Research and Review; Bright Sky Publications: Delhi, India, 2023; pp. 53–67. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, G.; Yang, X.; Wei, S.; Yan, L.; Wang, C.; Hua, Z.; Liu, X.; Bin, F.; Li, H. Potato seed-metering monitoring and improved miss-seeding catching-up compensation control system using spatial capacitance sensor. Int. J. Agric. Biol. Eng. 2024, 17, 255–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, H.; Wan, Y.; Zhong, P.; Lin, J.; Huang, M.; Yang, R.; Zang, Y. Design and experimental analysis of real-time detection system for The seeding accuracy of rice pneumatic seed metering device based on the improved YOLOv5n. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2024, 227, 109614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, L.; Wang, S.; Hu, B.; Li, T.; Zhao, M.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, M. Seed State-Detection Sensor for a Cotton Precision Dibble. Agriculture 2023, 13, 1515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Xia, J.; Hu, M.; Du, J.; Luo, C.; Zheng, K. Design and analysis of a performance monitoring system for a seed metering device based on pulse width recognition. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0261593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, S.; Feng, Y.; Cheng, X.; Wang, X.; Zhang, X.; Wei, Z. Disturbance analysis and seeding performance evaluation of a pneumatic-seed spoon interactive precision maize seed-metering device for plot planting. Biosyst. Eng. 2024, 247, 221–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Y.; Chen, L.; Meng, Z.; Li, B.; Luo, C.; Fu, W.; Mei, H.; Qin, W. Design and evaluation of a maize monitoring system for precision planting. Int. J. Agric. Biol. Eng. 2018, 11, 186–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Hu, J.; Zhao, X.; Pan, H.; Lakhiar, I.A.; Wang, W.; Zhao, J. Development and experimental analysis of a seeding quantity sensor for the precision seeding of small seeds. Sensors 2019, 19, 5191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zagainov, N.; Kostyuchenkov, N.; Huang, Y.; Sugirbay, A.; Xian, J. Line laser based sensor for real-time seed counting and seed miss detection for precision planter. Opt. Laser Technol. 2023, 167, 109742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Yi, S.; Zhao, B.; Li, Y.; Wang, G.; Li, S.; Sun, W. Photoelectric sensor-based belt-type high-speed seed guiding device performance monitoring method and system. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2024, 227, 109489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimi, H.; Navid, H.; Besharati, B.; Behfar, H.; Eskandari, I. A practical approach to comparative design of non-contact sensing techniques for seed flow rate detection. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2017, 142, 165–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, S.; Yuan, Y.; Niu, K.; Shi, Z.; Zhou, L.; Zhao, B.; Wei, L.; Liu, L.; Zheng, Y.; An, S.; et al. Design and experiment of a sowing quality monitoring system of cotton precision hill-drop planters. Agriculture 2022, 12, 1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, C.; Yang, L.; Zhang, D.; Cui, T.; Zhang, K.; He, X.; Du, Z. Design of smart seed sensor based on microwave detection method and signal calculation model. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2022, 199, 107178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Hou, Y.; Ji, W.; Zheng, P.; Yan, S.; Hou, S.; Cai, C. Evaluation of a Real-Time Monitoring and Management System of Soybean Precision Seed Metering Devices. Agronomy 2023, 13, 541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, H.; Xu, C.; Wang, Z.; Wang, Q.; Wang, J. Optimized Design, Monitoring System Development and Experiment for a Long-Belt Finger-Clip Precision Corn Seed Metering Device. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 814747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Wang, S.; Zhang, X.; Yuan, Y.; Zhang, J. Seed monitoring system for corn planter based on capacitance signal. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Eng. 2012, 28, 16–21. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Y.J.; Jia, H.L.; Ren, D.L.; Yan, J.J.; Liu, Y. Experimental study of capacitance sensors to test seed-flow. Appl. Mech. Mater. 2013, 347, 167–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jianguo, C.; Yanming, L.; Chengjin, Q.; Chengliang, L. Design and experiment of precision detecting system for wheat-planter seeding quantity. Nongye Jixie Xuebao/Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Mach. 2019, 50, 73–81. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, L.; Hu, B.; Li, J.; Ren, L.; Guo, M.; Mao, Z.; Cai, Y.; Sun, S. An efficient seeding state monitoring system of a pneumatic dibbler based on an interdigital capacitive sensor. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2023, 209, 107856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, D.; Jia, H.; Qi, Y.; Zhu, L.; Li, H. Seeding monitor system for planter based on polyvinylidence fluoride piezoelectric film. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Eng. 2013, 29, 15–22. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, D.; Zhu, L.; Jia, H.; Yu, T.; Yan, J. Remote monitoring system for corn seeding quality based on GPS and GPRS. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Eng. 2016, 32, 162–168. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, X.; Zhao, K.; Ji, J.; Qiu, Z.; He, Z.; Ma, H. Design and experiment of intelligent monitoring system for vegetable fertilizing and sowing. J. Supercomput. 2020, 76, 3338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, S.; Scola, I.; Bourges, G.; Šarauskis, E.; Karayel, D. Improving the seed detection accuracy of piezoelectric impact sensors for precision seeders. Part I: A comparative study of signal processing algorithms. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2023, 215, 108449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gierz, Ł.; Kruszelnicka, W.; Robakowska, M.; Przybył, K.; Koszela, K.; Marciniak, A.; Zwiachel, T. Optimization of the Sowing Unit of a Piezoelectrical Sensor Chamber with the Use of Grain Motion Modeling by Means of the Discrete Element Method. Case Study: Rape Seed. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 1594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pimentel, A.; Ferreira, S.H.; Nunes, D.; Calmeiro, T.; Martins, R.; Fortunato, E. Microwave synthesized ZnO nanorod arrays for UV sensors: A seed layer annealing temperature study. Materials 2016, 9, 299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boydas, M.G. Determination of low mass flow rate of wheat in a seed drill usinga microwave Doppler sensor. Span. J. Agric. Res. 2025, 23, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cakir, E.; Aygün, İ.; Yazgi, A.; Karabulut, Y. Determination of in-row seed distribution uniformity using image processing. Turk. J. Agric. For. 2016, 40, 874–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, W.; Ma, X.; Li, H.; Tan, S.; Guo, L. Detection of performance of hybrid rice pot-tray sowing utilizing machine vision and machine learning approach. Sensors 2019, 19, 5332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, J.; Hao, F.; Cheng, G.; Li, C. Machine vision-based supplemental seeding device for plug seedling of sweet corn. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2021, 188, 106345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Zhao, B.; Gao, S.; Ji, Y.; Zhou, L.; Niu, K.; Qiu, Z.; Jin, X. Online Recognition of Small Vegetable Seed Sowing Based on Machine Vision. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 134331–134339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borja, A.A.; Amongo, R.M.C.; Suministrado, D.; Pabico, J. A machine vision assisted mechatronic seed meter for precision planting of corn. In Proceedings of the 2018 3rd International Conference on Control and Robotics Engineering (ICCRE), Nagoya, Japan, 20–23 April 2018; pp. 183–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, G.; Balocco, S.; Mann, D.; Simundsson, A.; Khorasani, N. Intelligent agricultural machinery using deep learning. IEEE Instrum. Meas. Mag. 2021, 24, 93–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizvi, S.M.H.; Naseer, A.; Rehman, S.U.; Akram, S.; Gruhn, V. Revolutionizing agriculture: Machine and deep learning solutions for enhanced crop quality and weed control. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 11865–11878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Chen, W.; Zhang, X.; Qiu, M.; Jin, B.; He, J.; Xu, C.; Chen, L.; Wan, Y. A scene-adaptive reseeding system with missed seeding detection for double-disc air-suction seed meter based on an improved YOLOv8n algorithm. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2025, 237, 110682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, H.; Zhou, H.; Wang, X.; Chen, C. Real-time fruit recognition and grasping estimation for robotic apple harvesting. Sensors 2020, 20, 5670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maraveas, C.; Asteris, P.G.; Arvanitis, K.G.; Bartzanas, T.; Loukatos, D. Application of bio and nature-inspired algorithms in agricultural engineering. Arch. Comput. Methods Eng. 2023, 30, 1979–2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Zhang, H.; Liu, X.; Li, H.; Jia, S.; Sun, W.; Wang, G.; Quan, F.; Yang, S. Design and experiment of miss-seeding detection and preparatory seed scraper-belt compensation mechanism based on improved YOLOv5s for potato seed-metering devices. Front. Plant Sci. 2025, 16, 1686174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nikolay, Z.; Nikolay, K.; Gao, X.; Wei Li, Q.; Peng Mi, G.; Xiang Huang, Y. Design and testing of novel seed miss prevention system for single seed precision metering devices. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2022, 198, 107048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakirov, A.; Kostyuchenkov, N.; Kostyuchenkova, O.; Grishin, A.; Omarbekova, A.; Zagainov, N. Application of Seed Miss Prevention System for a Spoon-Wheel Type Precision Seed Metering Device: Effectiveness and Limitations. Agriculture 2025, 15, 1363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Seed Variety | Thousand- Grain Weight/g | Parameters | Maximum Value/mm | Minimum Value/mm | Average Value/mm |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sunflower Astana “Medium” | 95.48 | Length | 12.21 | 9.68 | 10.95 |

| Width | 5.98 | 4.30 | 5.14 | ||

| Height | 8.67 | 6.21 | 7.44 | ||

| Corn Dekalb DKC5032 | 343.2 | Length | 13.68 | 8.98 | 11.12 |

| Width | 5.95 | 3.52 | 4.74 | ||

| Height | 9.67 | 6.54 | 7.87 |

| Mode | Cultivar | Seed Prevention Disabled, without Magnets | Seed Prevention Disabled, with Magnets | Seed Prevention Enabled, with Magnets | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rpm | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 10 | 15 | 20 | 25 | 30 | 40 | 50 | 60 | 70 | 80 | 10 | 15 | 20 | 25 | 30 | 40 | 50 | 60 | 70 | 80 | 10 | 15 | 20 | 25 | 30 | 40 | 50 | 60 | 70 | 80 | ||

| Count | Corn ‘Dekalb DKC5032’ | 3078 | 3132 | 3139 | 3133 | 3075 | 3105 | 3043 | 3096 | 3068 | 3131 | 3093 | 3143 | 3100 | 3120 | 3140 | 3087 | 3043 | 3113 | 3101 | 3101 | 3131 | 3110 | 3020 | 3124 | 3253 | 3132 | 3115 | 3125 | 3193 | 3116 |

| Sunflower ‘Astana’ | 3037 | 2199 | 3018 | 3070 | 3148 | 3046 | 3144 | 3013 | 3039 | 3060 | 3019 | 3109 | 3024 | 3123 | 3029 | 3102 | 3031 | 3022 | 3035 | 3033 | 3144 | 3128 | 3137 | 3106 | 3053 | 3084 | 3056 | 3158 | 2997 | 3189 | |

| Single Misses | Corn ‘Dekalb DKC5032’ | 111 | 112 | 111 | 188 | 264 | 533 | 671 | 736 | 642 | 677 | 118 | 117 | 158 | 194 | 184 | 242 | 366 | 715 | 695 | 678 | 1 | 2 | 15 | 18 | 29 | 324 | 238 | 298 | 106 | 261 |

| Sunflower ‘Astana’ | 201 | 508 | 553 | 681 | 543 | 534 | 509 | 503 | 493 | 517 | 643 | 716 | 624 | 716 | 551 | 594 | 527 | 479 | 498 | 537 | 576 | 756 | 523 | 723 | 450 | 464 | 441 | 365 | 393 | 358 | |

| Double Misses | Corn ‘Dekalb DKC5032’ | 6 | 10 | 6 | 4 | 14 | 27 | 81 | 108 | 115 | 123 | 3 | 8 | 3 | 5 | 6 | 5 | 25 | 106 | 142 | 148 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 21 | 10 | 22 | 16 | 34 |

| Sunflower ‘Astana’ | 40 | 247 | 188 | 286 | 178 | 146 | 127 | 124 | 106 | 105 | 299 | 410 | 227 | 311 | 198 | 150 | 115 | 123 | 100 | 107 | 134 | 377 | 139 | 297 | 120 | 80 | 43 | 32 | 42 | 29 | |

| More than two Misses | Corn ‘Dekalb DKC5032’ | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 5 | 14 | 20 | 14 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 16 | 24 | 26 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 4 |

| Sunflower ‘Astana’ | 4 | 416 | 141 | 230 | 73 | 60 | 43 | 21 | 27 | 41 | 495 | 549 | 209 | 269 | 98 | 61 | 45 | 44 | 21 | 24 | 167 | 500 | 68 | 251 | 29 | 10 | 10 | 7 | 26 | 4 | |

| Miss Index | Corn ‘Dekalb DKC5032’ | 0.038 | 0.043 | 0.038 | 0.059 | 0.087 | 0.160 | 0.218 | 0.243 | 0.233 | 0.236 | 0.039 | 0.044 | 0.050 | 0.061 | 0.059 | 0.075 | 0.121 | 0.239 | 0.253 | 0.254 | 0.000 | 0.001 | 0.005 | 0.006 | 0.009 | 0.105 | 0.076 | 0.099 | 0.041 | 0.099 |

| Sunflower ‘Astana’ | 0.089 | 0.555 | 0.323 | 0.409 | 0.269 | 0.253 | 0.224 | 0.214 | 0.206 | 0.219 | 0.531 | 0.552 | 0.387 | 0.427 | 0.302 | 0.264 | 0.231 | 0.223 | 0.202 | 0.215 | 0.326 | 0.531 | 0.249 | 0.423 | 0.206 | 0.175 | 0.154 | 0.125 | 0.165 | 0.118 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kostyuchenkov, N.; Bakirov, A.; Kostyuchenkova, O.; Yerlan, S.; Zagainov, N. Hall Sensor-Based Detection and Prevention of Seed Misses in Long-Belt Finger-Clip Precision Metering Device. AgriEngineering 2025, 7, 436. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriengineering7120436

Kostyuchenkov N, Bakirov A, Kostyuchenkova O, Yerlan S, Zagainov N. Hall Sensor-Based Detection and Prevention of Seed Misses in Long-Belt Finger-Clip Precision Metering Device. AgriEngineering. 2025; 7(12):436. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriengineering7120436

Chicago/Turabian StyleKostyuchenkov, Nikolay, Aldiyar Bakirov, Oksana Kostyuchenkova, Saidalin Yerlan, and Nikolay Zagainov. 2025. "Hall Sensor-Based Detection and Prevention of Seed Misses in Long-Belt Finger-Clip Precision Metering Device" AgriEngineering 7, no. 12: 436. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriengineering7120436

APA StyleKostyuchenkov, N., Bakirov, A., Kostyuchenkova, O., Yerlan, S., & Zagainov, N. (2025). Hall Sensor-Based Detection and Prevention of Seed Misses in Long-Belt Finger-Clip Precision Metering Device. AgriEngineering, 7(12), 436. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriengineering7120436