Sensing in Smart Cities: A Multimodal Machine Learning Perspective

Highlights

- Presents a detailed framework and review of multimodal machine learning (MML) approaches utilized within smart urban environments.

- Highlights the effectiveness of MML techniques and current technical limitations in modality fusion, scalability, and real-time implementation across urban domains.

- Provides essential guidance to researchers, academicians, policymakers, and developers on choosing effective MML approaches for key smart city applications.

- Identifies current challenges and practical solutions to advance the deployment of multimodal machine learning in complex urban environments.

Abstract

1. Introduction

- To classify and contextualize the types of multimodal data generated in smart cities, with a focus on sensing technologies and urban data sources.

- To provide a systematic overview of multimodal machine learning techniques such as fusion strategies, cross-modal learning, and attention mechanisms while addressing technical challenges, including alignment, scalability, and data quality.

- To review the practical applications of MML in smart city domains, including mobility, environmental monitoring, public safety, healthcare, and governance.

- To identify the current challenges related to deploying multimodal machine learning in smart city environments, including infrastructure limitations, policy constraints, and ethical considerations.

- To outline future research directions and opportunities at the intersection of MML and smart city development, aiming to inform the design of robust, ethical, and scalable intelligent urban systems.

2. Background and Foundations

3. Techniques in Multimodal Machine Learning for Smart Cities

3.1. Fusion Strategies in Deep Learning for Smart Cities

3.1.1. Early Fusion

3.1.2. Late Fusion

3.1.3. Hybrid Fusion

3.2. Deep Learning-Based Models for Fusion

- Convolutional Layer: This layer applies filters to the input image (or visual data) to detect low-level features, such as edges or corners. It produces feature maps that highlight important patterns in the data.

- Pooling Layer: After convolution, pooling is applied to reduce the spatial dimensions of the feature maps while retaining important information. This helps the model become invariant to small translations of the input data.

- Fully Connected Layer: The final layer combines the extracted features to make predictions or classifications based on the learned patterns. In multimodal fusion, these outputs are often combined with data from other sources (such as environmental sensor readings) at a later stage.

- Input Sequence: The input sequence of elements will be a mix of text tokens and image features (e.g., from CNNs for visual data).

- Query, Key, and Value Vectors: Each element in the input (text or visual) is transformed into three vectors: Query (Q), Key (K), and Value (V).

- Attention Scores: This explains how the Query (Q) is compared to all Keys (K) to compute attention scores.

- Softmax and Weighted Sum: After computing the attention scores, we will show how they are normalized (via softmax) and used to weight the Value (V) vectors.

- Output: The final output of the self-attention layer, which is a contextualized representation for each element, will be shown.

3.3. Comparative Assessment of MML Techniques and Their Performance

3.4. Core Challenges in the Multimodal Fusion

3.4.1. Multimodal Representation Learning

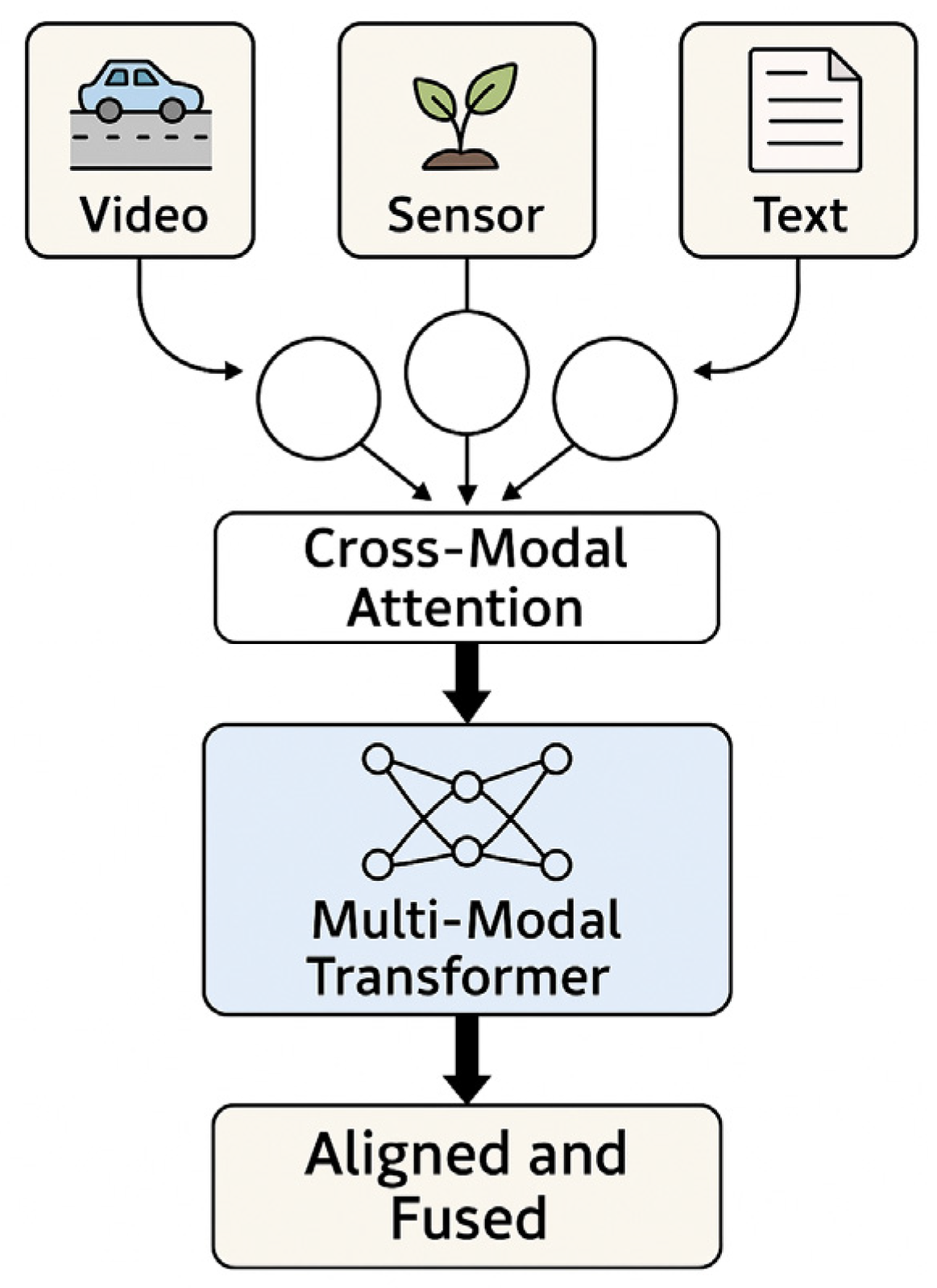

3.4.2. Cross-Modal Alignment

Temporal Misalignment

Spatial Misalignment

3.4.3. Scalability and Real-Time Constraints

3.4.4. Robustness to Missing or Noisy Modalities

3.4.5. Interpretability of Models

3.4.6. Dataset and Benchmark Limitations

4. Applications of Multimodal Machine Learning in Smart Cities

- Multimodal surveillance for event monitoring: During large public events, integrated systems that analyze live video, crowd noise levels, and social media activity help detect and manage instances of unrest or overcrowding [110].

- Healthcare and epidemiology surveillance: In response to the COVID-19 pandemic, some regions have experimented with merging data from wearable devices, public health databases, and mobility tracking to understand the spread and impact of the virus at a neighborhood level [113].

4.1. Traffic and Transportation

4.2. Environmental Monitoring

4.3. Public Safety and Surveillance

4.4. Urban Planning and Infrastructure

4.5. Citizen Engagement and Services

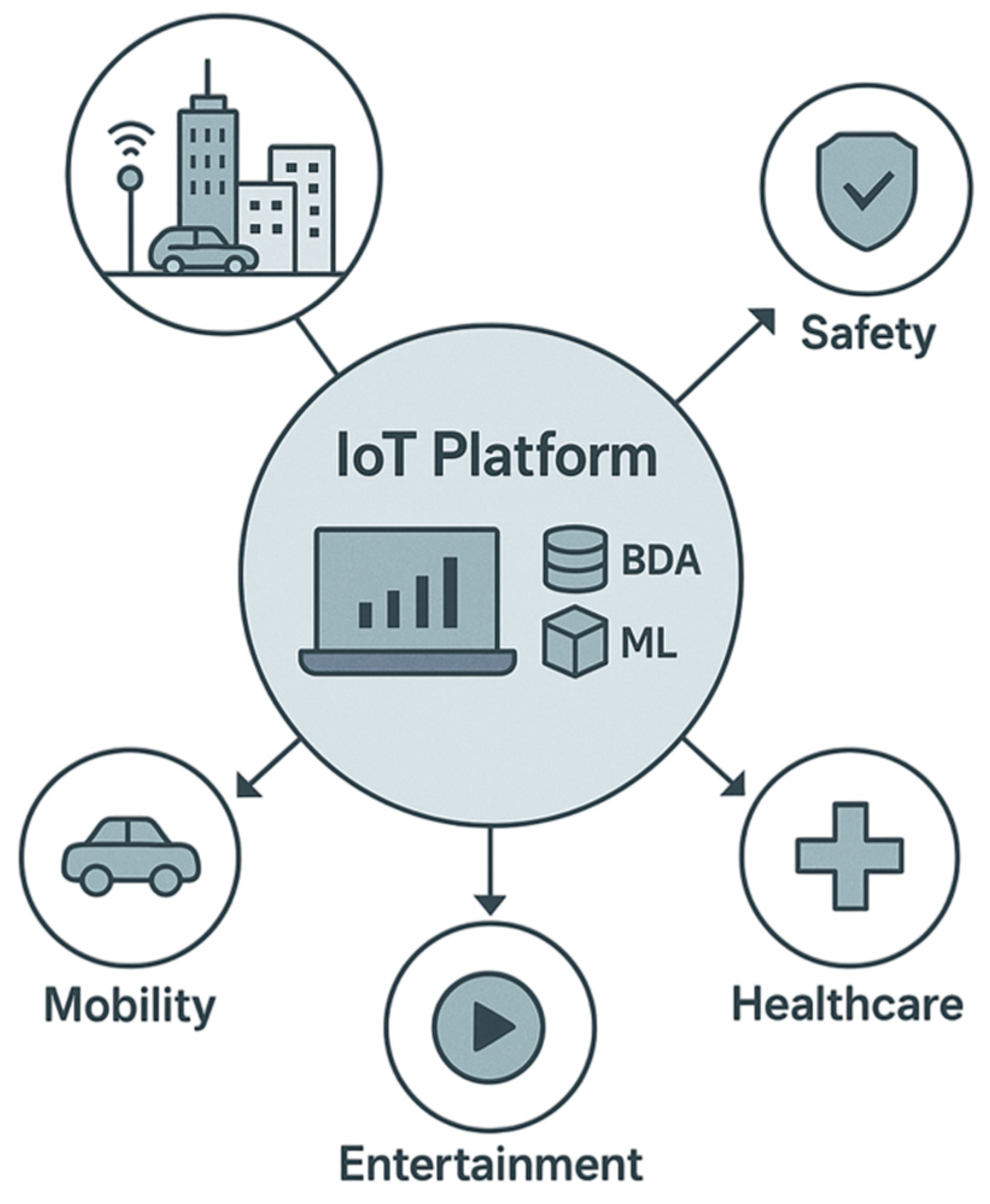

4.6. IoT Platform

4.7. Cloud Computing

4.8. Edge Computing

4.9. Healthcare and Health Monitoring

5. Challenges and Limitations of MML Deployment in Smart Cities

5.1. Privacy and Security Concerns

5.2. Ethical Considerations

6. Research Gaps and Future Directions in Multimodal Sensing for Smart City Applications

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Baltrušaitis, T.; Ahuja, C.; Morency, L.-P. Multimodal machine learning: A survey and taxonomy. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2018, 41, 423–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valet, L.; Mauris, G.; Bolon, P.; Keskes, N. A fuzzy rule-based interactive fusion system for seismic data analysis. Inf. Fusion 2003, 4, 123–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Florescu, D.; Koller, D. Using probabilistic information in data integration. In Proceedings of the 23rd International Conference on Very Large Data Bases VLDB, San Francisco, CA, USA, 25–29 August 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Buccella, A.; Cechich, A.; Rodríguez Brisaboa, N. An ontology approach to data integration. J. Comput. Sci. Technol. 2003, 3, 62–68. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, H.; Haque, A.; Blaabjerg, F. Machine learning in wireless sensor networks for smart cities: A survey. Electronics 2021, 10, 1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anwar, M.R.; Sakti, L.D. Integrating artificial intelligence and environmental science for sustainable urban planning. IAIC Trans. Sustain. Digit. Innov. (ITSDI) 2024, 5, 179–191. [Google Scholar]

- Ortega-Fernández, A.; Martín-Rojas, R.; García-Morales, V.J. Artificial intelligence in the urban environment: Smart cities as models for developing innovation and sustainability. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, Z.; Al-Turjman, F.; Mostarda, L.; Gagliardi, R. Applications of artificial intelligence and machine learning in smart cities. Comput. Commun. 2020, 154, 313–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawłowski, M.; Wróblewska, A.; Sysko-Romańczuk, S. Effective techniques for multimodal data fusion: A comparative analysis. Sensors 2023, 23, 2381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, X.; Wang, S.; Yang, D.; Hu, T.; Chen, M.; Zhang, M.; Zhang, G.; Biljecki, F.; Lu, T.; Zou, L. Crowdsourcing geospatial data for earth and human observations: A review. J. Remote Sens. 2024, 4, 0105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lahat, D.; Adali, T.; Jutten, C. Multimodal data fusion: An overview of methods, challenges, and prospects. Proc. IEEE 2015, 103, 1449–1477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, H.-W.; Kang, H.-B. Prediction of crime occurrence from multi-modal data using deep learning. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0176244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, S.; Vargas-Munoz, J.E.; Tuia, D. Understanding urban landuse from the above and ground perspectives: A deep learning, multimodal solution. Remote Sens. Environ. 2019, 228, 129–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prawiyogi, A.G.; Purnama, S.; Meria, L. Smart cities using machine learning and intelligent applications. Int. Trans. Artif. Intell. 2022, 1, 102–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, F.; Mehmood, R.; Katib, I.; Albogami, N.N.; Albeshri, A. Data fusion and IoT for smart ubiquitous environments: A survey. IEEE Access 2017, 5, 9533–9554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lifelo, Z.; Ding, J.; Ning, H.; Dhelim, S. Artificial intelligence-enabled metaverse for sustainable smart cities: Technologies, applications, challenges, and future directions. Electronics 2024, 13, 4874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasr, M.; Islam, M.M.; Shehata, S.; Karray, F.; Quintana, Y.J.I. Smart healthcare in the age of AI: Recent advances, challenges, and future prospects. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 145248–145270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myagmar-Ochir, Y.; Kim, W. A survey of video surveillance systems in smart city. Electronics 2023, 12, 3567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bello, J.P.; Mydlarz, C.; Salamon, J. Sound analysis in smart cities. In Computational Analysis of Sound Scenes and Events; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017; pp. 373–397. [Google Scholar]

- Lim, C.; Cho, G.-H.; Kim, J. Understanding the linkages of smart-city technologies and applications: Key lessons from a text mining approach and a call for future research. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2021, 170, 120893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musa, A.A.; Malami, S.I.; Alanazi, F.; Ounaies, W.; Alshammari, M.; Haruna, S.I. Sustainable traffic management for smart cities using internet-of-things-oriented intelligent transportation systems (ITS): Challenges and recommendations. Sustainability 2023, 15, 9859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mete, M.O. Geospatial big data analytics for sustainable smart cities. Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2023, 48, 141–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panahi, O. Wearable sensors and personalized sustainability: Monitoring health and environmental exposures in real-time. Eur. J. Innov. Stud. Sustain. 2025, 1, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shahzad, S.K.; Ahmed, D.; Naqvi, M.R.; Mushtaq, M.T.; Iqbal, M.W.; Munir, F. Ontology driven smart health service integration. Comput. Methods Programs Biomed. 2021, 207, 106146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, Ł.; Polosukhin, I. Attention is all you need. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2017, 30, 6000–6010. [Google Scholar]

- Driver, J.; Spence, C. Cross–modal links in spatial attention. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. Ser. B Biol. Sci. 1998, 353, 1319–1331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ektefaie, Y.; Dasoulas, G.; Noori, A.; Farhat, M.; Zitnik, M. Multimodal learning with graphs. Nat. Mach. Intell. 2023, 5, 340–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolniak, R.; Stecuła, K. Artificial intelligence in smart cities—Applications, barriers, and future directions: A review. Smart Cities 2024, 7, 1346–1389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadiq, T.; Omlin, C.W. NLP-based Traffic Scene Retrieval via Representation Learning. In Proceedings of the 9th World Congress on Electrical Engineering and Computer Systems and Sciences (EECSS 2023), London, UK, 3–5 August 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Concas, F.; Mineraud, J.; Lagerspetz, E.; Varjonen, S.; Liu, X.; Puolamäki, K.; Nurmi, P.; Tarkoma, S. Low-cost outdoor air quality monitoring and sensor calibration: A survey and critical analysis. ACM Trans. Sens. Netw. (TOSN) 2021, 17, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Ibánez, M.; Casánez-Ventura, A.; Castejón-Mateos, F.; Cuenca-Jiménez, P.-M. A review on sentiment analysis from social media platforms. Expert Syst. Appl. 2023, 223, 119862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luca, M.; Barlacchi, G.; Lepri, B.; Pappalardo, L. A survey on deep learning for human mobility. ACM Comput. Surv. (CSUR) 2021, 55, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, F.; Zhang, C.; Geng, B. Deep multimodal data fusion. ACM Comput. Surv. 2024, 56, 216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.H.; Yatskar, M.; Yin, D.; Hsieh, C.-J.; Chang, K.-W. Visualbert: A simple and performant baseline for vision and language. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1908.03557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, W.; Zhu, X.; Cao, Y.; Li, B.; Lu, L.; Wei, F.; Dai, J. Vl-bert: Pre-training of generic visual-linguistic representations. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1908.08530. [Google Scholar]

- Radford, A.; Kim, J.W.; Hallacy, C.; Ramesh, A.; Goh, G.; Agarwal, S.; Sastry, G.; Askell, A.; Mishkin, P.; Clark, J. Learning transferable visual models from natural language supervision. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning, Virtual, 18–24 July 2021; pp. 8748–8763. [Google Scholar]

- Jia, C.; Yang, Y.; Xia, Y.; Chen, Y.-T.; Parekh, Z.; Pham, H.; Le, Q.; Sung, Y.-H.; Li, Z.; Duerig, T. Scaling up visual and vision-language representation learning with noisy text supervision. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning, Virtual, 18–24 July 2021; pp. 4904–4916. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, H.; Bansal, M. Lxmert: Learning cross-modality encoder representations from transformers. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1908.07490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Batra, D.; Parikh, D.; Lee, S. Vilbert: Pretraining task-agnostic visiolinguistic representations for vision-and-language tasks. In Proceedings of the 33rd International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, Red Hook, NY, USA, 8–14 December 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.-C.; Li, L.; Yu, L.; El Kholy, A.; Ahmed, F.; Gan, Z.; Cheng, Y.; Liu, J. Uniter: Universal image-text representation learning. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision, Glasgow, UK, 23–28 August 2020; pp. 104–120. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Selvaraju, R.; Gotmare, A.; Joty, S.; Xiong, C.; Hoi, S.C.H. Align before fuse: Vision and language representation learning with momentum distillation. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2021, 34, 9694–9705. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Li, D.; Xiong, C.; Hoi, S. Blip: Bootstrapping language-image pre-training for unified vision-language understanding and generation. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning, Baltimore, MD, USA, 17–23 July 2022; pp. 12888–12900. [Google Scholar]

- Gandhi, A.; Adhvaryu, K.; Poria, S.; Cambria, E.; Hussain, A. Multimodal sentiment analysis: A systematic review of history, datasets, multimodal fusion methods, applications, challenges and future directions. Inf. Fusion 2023, 91, 424–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koroteev, M.V. BERT: A review of applications in natural language processing and understanding. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2103.11943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Gao, C.; Niu, G.; Xiao, X.; Liu, H.; Liu, J.; Wu, H.; Wang, H. Unimo: Towards unified-modal understanding and generation via cross-modal contrastive learning. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2012.15409. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, X.; Wang, Y.; He, Y.; Yang, Y.; Hanjalic, A.; Shen, H.T. Cross-modal hybrid feature fusion for image-sentence matching. ACM Trans. Multimed. Comput. Commun. Appl. (TOMM) 2021, 17, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gadzicki, K.; Khamsehashari, R.; Zetzsche, C. Early vs late fusion in multimodal convolutional neural networks. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE 23rd International Conference on Information Fusion (FUSION), Pretoria, South Africa, 6–9 July 2020; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, J.; Li, P.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, J. A survey on deep learning for multimodal data fusion. Neural Comput. 2020, 32, 829–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saleh, K.; Hossny, M.; Nahavandi, S. Driving behavior classification based on sensor data fusion using LSTM recurrent neural networks. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE 20th International Conference on Intelligent Transportation Systems (ITSC), Yokohama, Japan, 16–19 October 2017; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Rudovic, O.; Zhang, M.; Schuller, B.; Picard, R. Multi-modal active learning from human data: A deep reinforcement learning approach. In Proceedings of the 2019 International Conference on Multimodal Interaction, Suzhou, China, 14–18 October 2019; pp. 6–15. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Lyu, J.; Kim, B.-G.; Parameshachari, B.; Li, K.; Li, Q. Exploring multimodal multiscale features for sentiment analysis using fuzzy-deep neural network learning. IEEE Trans. Fuzzy Syst. 2024, 33, 28–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Touvron, H.; Cord, M.; Douze, M.; Massa, F.; Sablayrolles, A.; Jégou, H. Training data-efficient image transformers & distillation through attention. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning, Virtual, 18–24 July 2021; pp. 10347–10357. [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi, S.; Sakaguchi, Y.; Kouno, N.; Takasawa, K.; Ishizu, K.; Akagi, Y.; Aoyama, R.; Teraya, N.; Bolatkan, A.; Shinkai, N. Comparison of vision transformers and convolutional neural networks in medical image analysis: A systematic review. J. Med. Syst. 2024, 48, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, M.W.; Sadiq, T.; Rahman, H.; Alateyah, S.A.; Alnusayri, M.; Alatiyyah, M.; AlHammadi, D.A. MAPE-ViT: Multimodal scene understanding with novel wavelet-augmented Vision Transformer. PeerJ Comput. Sci. 2025, 11, e2796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shaw, P.; Uszkoreit, J.; Vaswani, A. Self-attention with relative position representations. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1803.02155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dosovitskiy, A.; Beyer, L.; Kolesnikov, A.; Weissenborn, D.; Zhai, X.; Unterthiner, T.; Dehghani, M.; Minderer, M.; Heigold, G.; Gelly, S. An image is worth 16x16 words: Transformers for image recognition at scale. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2010.11929. [Google Scholar]

- Tian, Y.; Sun, C.; Poole, B.; Krishnan, D.; Schmid, C.; Isola, P. What makes for good views for contrastive learning? Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2020, 33, 6827–6839. [Google Scholar]

- Sadiq, T.; Omlin, C.W. Scene Retrieval in Traffic Videos with Contrastive Multimodal Learning. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE 35th International Conference on Tools with Artificial Intelligence (ICTAI), Atlanta, GA, USA, 6–8 November 2023; pp. 1020–1025. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L.; Sng, D. Deep learning algorithms with applications to video analytics for a smart city: A survey. arXiv 2015, arXiv:1512.03131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, H.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, H. Predict vessel traffic with weather conditions based on multimodal deep learning. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2022, 11, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Yang, C.; Liu, K.; Chen, B.; Yao, Y. Domain adaptation transfer learning soft sensor for product quality prediction. Chemom. Intell. Lab. Syst. 2019, 192, 103813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soni, U. Integration of Traffic Data from Social Media and Physical Sensors for Near Real Time Road Traffic Analysis. Master’s Thesis, University of Twente, Enschede, The Netherlands, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Luan, S.; Ke, R.; Huang, Z.; Ma, X. Traffic congestion propagation inference using dynamic Bayesian graph convolution network. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2022, 135, 103526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, D.; Gan, V.J.; Tekler, Z.D.; Chong, A.; Tian, S.; Shi, X. Data-driven predictive control for smart HVAC system in IoT-integrated buildings with time-series forecasting and reinforcement learning. Appl. Energy 2023, 338, 120936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, C.; Sun, F.; Kong, T.; Zhang, W.; Yang, C.; Liu, C. A survey on deep transfer learning. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Artificial Neural Networks, Rhodes, Greece, 4–7 October 2018; pp. 270–279. [Google Scholar]

- Saini, K.; Sharma, S. Smart Road Traffic Monitoring: Unveiling the Synergy of IoT and AI for Enhanced Urban Mobility. ACM Comput. Surv. 2025, 57, 276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordan, S.; Chandak, Y.; Cohen, D.; Zhang, M.; Thomas, P. Evaluating the performance of reinforcement learning algorithms. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning, Virtual, 13–18 July 2020; pp. 4962–4973. [Google Scholar]

- Maadi, S.; Stein, S.; Hong, J.; Murray-Smith, R. Real-time adaptive traffic signal control in a connected and automated vehicle environment: Optimisation of signal planning with reinforcement learning under vehicle speed guidance. Sensors 2022, 22, 7501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouoba, J.; Lahti, J.; Ahola, J. Connecting digital cities: Return of experience on the development of a data platform for multimodal journey planning. In International Summit, Smart City 360°; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2015; pp. 91–103. [Google Scholar]

- Botea, A.; Berlingerio, M.; Braghin, S.; Bouillet, E.; Calabrese, F.; Chen, B.; Gkoufas, Y.; Nair, R.; Nonner, T.; Laumanns, M. Docit: An integrated system for risk-averse multimodal journey advising. In Smart Cities and Homes; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2016; pp. 345–359. [Google Scholar]

- Asgari, F. Inferring User Multimodal Trajectories from Cellular Network Metadata in Metropolitan Areas. Ph.D. Thesis, Institut National des Télécommunications, Paris, France, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Alessandretti, L.; Karsai, M.; Gauvin, L. User-based representation of time-resolved multimodal public transportation networks. R. Soc. Open Sci. 2016, 3, 160156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pronello, C.; Gaborieau, J.-B. Engaging in pro-environment travel behaviour research from a psycho-social perspective: A review of behavioural variables and theories. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, Y.; Youm, S. Multimedia application to an extended public transportation network in South Korea: Optimal path search in a multimodal transit network. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2017, 76, 19945–19957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sokolov, I.; Kupriyanovsky, V.; Dunaev, O.; Sinyagov, S.; Kurenkov, P.; Namiot, D.; Dobrynin, A.; Kolesnikov, A.; Gonik, M. On breakthrough innovative technologies for infrastructures. The Eurasian digital railway as a basis of the logistic corridor of the new Silk Road. Int. J. Open Inf. Technol. 2017, 5, 102–118. [Google Scholar]

- Young, G.W.; Naji, J.; Charlton, M.; Brunsdon, C.; Kitchin, R. Future cities and multimodalities: How multimodal technologies can improve smart-citizen engagement with city dashboards. In Proceedings of the ISU Talks #05: Future Cities, Braunschweig, Germany, 14 November 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, S.; Datta, D.; Singh, S.K.; Sangaiah, A.K. An intelligent decision computing paradigm for crowd monitoring in the smart city. J. Parallel Distrib. Comput. 2018, 118, 344–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Xiao, W.; Coifman, B.; Mills, J.P. Vehicle tracking and speed estimation from roadside lidar. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2020, 13, 5597–5608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nigam, N.; Singh, D.P.; Choudhary, J. A review of different components of the intelligent traffic management system (ITMS). Symmetry 2023, 15, 583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, P.; Zhang, Z.; Peng, X.; Wang, R. Deep learning solutions for smart city challenges in urban development. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 5176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, W.; Wu, G.; Han, J. Deep Multimodal-Interactive Document Summarization Network and Its Cross-Modal Text–Image Retrieval Application for Future Smart City Information Management Systems. Smart Cities 2025, 8, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Wang, T.; Ge, Y.; Lu, Z.; Zhou, R.; Shan, Y.; Luo, P. π-Tuning: Transferring Multimodal Foundation Models with Optimal Multi-Task Interpolation. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning, Honolulu, HI, USA, 23–29 July 2023; pp. 37713–37727. [Google Scholar]

- Bian, L. Multiscale nature of spatial data in scaling up environmental models. In Scale in Remote Sensing and GIS; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2023; pp. 13–26. [Google Scholar]

- Pang, T.; Lin, M.; Yang, X.; Zhu, J.; Yan, S. Robustness and accuracy could be reconcilable by (proper) definition. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning, Baltimore, MD, USA, 17–23 July 2022; pp. 17258–17277. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, X.; Song, Z.; King, I.; Xu, Z. A survey on deep semi-supervised learning. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng. 2022, 35, 8934–8954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alzubaidi, L.; Al-Amidie, M.; Al-Asadi, A.; Humaidi, A.J.; Al-Shamma, O.; Fadhel, M.A.; Zhang, J.; Santamaría, J.; Duan, Y. Novel transfer learning approach for medical imaging with limited labeled data. Cancers 2021, 13, 1590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barua, A.; Ahmed, M.U.; Begum, S. A systematic literature review on multimodal machine learning: Applications, challenges, gaps and future directions. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 14804–14831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kieu, N.; Nguyen, K.; Nazib, A.; Fernando, T.; Fookes, C.; Sridharan, S. Multimodal colearning meets remote sensing: Taxonomy, state of the art, and future works. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2024, 17, 7386–7409. [Google Scholar]

- Lopes, P.P. Pondiônstracker: A Framework Based on GTFS-RT to Identify Delays and Estimate Arrivals Dynamically in Public Transportation Network. Master’s Thesis, Pontifical Catholic University of Minas Gerais, Belo Horizonte, Brazil, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, R.; Wang, H.; Chen, H.-T.; Carneiro, G. Deep multimodal learning with missing modality: A survey. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2409.07825. [Google Scholar]

- Seu, K.; Kang, M.-S.; Lee, H. An intelligent missing data imputation techniques: A review. JOIV Int. J. Inform. Vis. 2022, 6, 278–283. [Google Scholar]

- Psychogyios, K.; Ilias, L.; Ntanos, C.; Askounis, D. Missing value imputation methods for electronic health records. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 21562–21574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çetin, V.; Yıldız, O. A comprehensive review on data preprocessing techniques in data analysis. Pamukkale Üniv. Mühendis. Bilim. Derg. 2022, 28, 299–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Younis, E.M.; Zaki, S.M.; Kanjo, E.; Houssein, E.H. Evaluating ensemble learning methods for multi-modal emotion recognition using sensor data fusion. Sensors 2022, 22, 5611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrario, A.; Loi, M. How explainability contributes to trust in AI. In Proceedings of the 2022 ACM Conference on Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 21–24 June 2022; pp. 1457–1466. [Google Scholar]

- Bell, A.; Solano-Kamaiko, I.; Nov, O.; Stoyanovich, J. It’s just not that simple: An empirical study of the accuracy-explainability trade-off in machine learning for public policy. In Proceedings of the 2022 ACM Conference on Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 21–24 June 2022; pp. 248–266. [Google Scholar]

- Mahbooba, B.; Timilsina, M.; Sahal, R.; Serrano, M. Explainable artificial intelligence (XAI) to enhance trust management in intrusion detection systems using decision tree model. Complexity 2021, 2021, 6634811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salih, A.M.; Raisi-Estabragh, Z.; Galazzo, I.B.; Radeva, P.; Petersen, S.E.; Lekadir, K.; Menegaz, G. A perspective on explainable artificial intelligence methods: SHAP and LIME. Adv. Intell. Syst. 2025, 7, 2400304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Wang, D.; Pedrycz, W.; Li, Z. Fuzzy rule-based local surrogate models for black-box model explanation. IEEE Trans. Fuzzy Syst. 2022, 31, 2056–2064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordts, M.; Omran, M.; Ramos, S.; Rehfeld, T.; Enzweiler, M.; Benenson, R.; Franke, U.; Roth, S.; Schiele, B. The cityscapes dataset for semantic urban scene understanding. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016; pp. 3213–3223. [Google Scholar]

- Lam, D.; Kuzma, R.; McGee, K.; Dooley, S.; Laielli, M.; Klaric, M.; Bulatov, Y.; McCord, B. xView: Objects in context in overhead imagery. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1802.07856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfeil, M.; Bartoschek, T.; Wirwahn, J.A. Opensensemap—A Citizen Science Platform for Publishing and Exploring Sensor Data as Open Data. 2018. Available online: https://opensensemap.org (accessed on 15 December 2025).

- Bui, L. Breathing smarter: A critical look at representations of air quality sensing data across platforms and publics. In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE First International Smart Cities Conference (ISC2), Guadalajara, Mexico, 25–28 October 2015; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Sahoh, B.; Choksuriwong, A. The role of explainable Artificial Intelligence in high-stakes decision-making systems: A systematic review. J. Ambient. Intell. Humaniz. Comput. 2023, 14, 7827–7843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naidu, G.; Zuva, T.; Sibanda, E.M. A review of evaluation metrics in machine learning algorithms. In Proceedings of the Computer Science on-Line Conference, Online, 3–5 April 2023; pp. 15–25. [Google Scholar]

- Anjuma, K.; Arshad, M.A.; Hayawi, K.; Polyzos, E.; Tariq, A.; Serhani, M.A.; Batool, L.; Lund, B.; Mannuru, N.R.; Bevara, R.V.K. Domain Specific Benchmarks for Evaluating Multimodal Large Language Models. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2506.12958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Gallego, G.; Lu, X.; Liu, S.; Shen, S. Event-based motion segmentation with spatio-temporal graph cuts. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2021, 34, 4868–4880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, W.; Bai, X.; Yang, D.; Yuen, K.F.; Wu, J. A deep learning approach for port congestion estimation and prediction. Marit. Policy Manag. 2023, 50, 835–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Ong, G.P. Prediction of Next-Time Traffic Congestion with Consideration of Congestion Propagation Patterns and Co-occurrence. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2025, 74, 16978–16989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wattacheril, C.Y.; Hemalakshmi, G.; Murugan, A.; Abhiram, P.; George, A.M. Machine Learning-Based Threat Detection in Crowded Environments. In Proceedings of the 2024 International Conference on Smart Technologies for Sustainable Development Goals (ICSTSDG), Chennai, India, 6–8 November 2024; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, Q.; Kresin, F.; Bregt, A.K.; Kooistra, L.; Pareschi, E.; Van Putten, E.; Volten, H.; Wesseling, J. Citizen sensing for improved urban environmental monitoring. J. Sens. 2016, 2016, 5656245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, C.C.; Kim, H.; Vilcassim, M.R.; Thurston, G.D.; Gordon, T.; Chen, L.-C.; Lee, K.; Heimbinder, M.; Kim, S.-Y. Mapping urban air quality using mobile sampling with low-cost sensors and machine learning in Seoul, South Korea. Environ. Int. 2019, 131, 105022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, T.; Wang, S.; She, B.; Zhang, M.; Huang, X.; Cui, Y.; Khuri, J.; Hu, Y.; Fu, X.; Wang, X. Human mobility data in the COVID-19 pandemic: Characteristics, applications, and challenges. Int. J. Digit. Earth 2021, 14, 1126–1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almujally, N.A.; Qureshi, A.M.; Alazeb, A.; Rahman, H.; Sadiq, T.; Alonazi, M.; Algarni, A.; Jalal, A. A novel framework for vehicle detection and tracking in night ware surveillance systems. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 88075–88085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Son, H.; Jang, J.; Park, J.; Balog, A.; Ballantyne, P.; Kwon, H.R.; Singleton, A.; Hwang, J. Leveraging advanced technologies for (smart) transportation planning: A systematic review. Sustainability 2025, 17, 2245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaib, S.; Lu, J.; Bilal, M. Spatio-temporal characteristics of air quality index (AQI) over Northwest China. Atmosphere 2022, 13, 375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Mei, L.; Lv, Z.; Hu, C.; Luo, X.; Zhang, H.; Liu, Y. Multi-modal description of public safety events using surveillance and social media. IEEE Trans. Big Data 2017, 5, 529–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alrashdi, I.; Alqazzaz, A.; Aloufi, E.; Alharthi, R.; Zohdy, M.; Ming, H. AD-IoT: Anomaly detection of IoT cyberattacks in smart city using machine learning. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE 9th Annual Computing and Communication Workshop and Conference (CCWC), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 7–9 January 2019; pp. 0305–0310. [Google Scholar]

- Islam, M.; Dukyil, A.S.; Alyahya, S.; Habib, S. An IoT enable anomaly detection system for smart city surveillance. Sensors 2023, 23, 2358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, C.; Guo, H.; Swan, I.; Gao, P.; Yao, Q.; Li, H. Evaluating trends, profits, and risks of global cities in recent urban expansion for advancing sustainable development. Habitat Int. 2023, 138, 102869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jadhav, S.; Durairaj, M.; Reenadevi, R.; Subbulakshmi, R.; Gupta, V.; Ramesh, J.V.N. Spatiotemporal data fusion and deep learning for remote sensing-based sustainable urban planning. Int. J. Syst. Assur. Eng. Manag. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, J.; Zhao, Y. Traffic Prediction with Data Fusion and Machine Learning. Analytics 2025, 4, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karagiannopoulou, A.; Tsertou, A.; Tsimiklis, G.; Amditis, A. Data fusion in earth observation and the role of citizen as a sensor: A scoping review of applications, methods and future trends. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, I.-C.; Chang, C.-C. Integrating machine learning and open data into social Chatbot for filtering information rumor. J. Ambient. Intell. Humaniz. Comput. 2021, 12, 1023–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Liu, H.; Wang, W.; Zheng, Y.; Lv, H.; Lv, Z. Big data analysis of the internet of things in the digital twins of smart city based on deep learning. Future Gener. Comput. Syst. 2022, 128, 167–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Huang, Y.; Jin, C.; Zhou, X.; Mao, Y.; Catal, C.; Cheng, L. Privacy and integrity protection for IoT multimodal data using machine learning and blockchain. ACM Trans. Multimed. Comput. Commun. Appl. 2024, 20, 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zekić-Sušac, M.; Mitrović, S.; Has, A. Machine learning based system for managing energy efficiency of public sector as an approach towards smart cities. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2021, 58, 102074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Cui, W.; Zhang, M. Exploring the causal relationship between urbanization and air pollution: Evidence from China. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2022, 80, 103783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malatesta, T.; Breadsell, J.K. Identifying home system of practices for energy use with k-means clustering techniques. Sustainability 2022, 14, 9017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilicay-Ergin, N.; Barb, A.S. Semantic fusion with deep learning and formal ontologies for evaluation of policies and initiatives in the smart city domain. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 10037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naoui, M.A.; Lejdel, B.; Ayad, M.; Amamra, A.; Kazar, O. Using a distributed deep learning algorithm for analyzing big data in smart cities. Smart Sustain. Built Environ. 2021, 10, 90–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atitallah, S.B.; Driss, M.; Boulila, W.; Ghézala, H.B. Leveraging deep learning and IoT big data analytics to support smart cities development: Review and future directions. Comput. Sci. Rev. 2020, 38, 100303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, A.; Wang, H.; Li, Y.; Dennis, S.; Hutch, M.; Xu, Z.; Wang, F.; Cheng, F.; Luo, Y. Multimodal machine learning in precision health: A scoping review. NPJ Digit. Med. 2022, 5, 171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dautov, R.; Distefano, S.; Buyya, R. Hierarchical data fusion for smart healthcare. J. Big Data 2019, 6, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazari, E.; Chang, H.-C.H.; Deldar, K.; Pour, R.; Avan, A.; Tara, M.; Mehrabian, A.; Tabesh, H. A comprehensive overview of decision fusion technique in healthcare: A systematic scoping review. Iran. Red Crescent Med. J. 2020, 22, e30. [Google Scholar]

- Haltaufderheide, J.; Ranisch, R. The ethics of ChatGPT in medicine and healthcare: A systematic review on Large Language Models (LLMs). NPJ Digit. Med. 2024, 7, 183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Demelius, L.; Kern, R.; Trügler, A. Recent advances of differential privacy in centralized deep learning: A systematic survey. ACM Comput. Surv. 2025, 57, 158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sampaio, S.; Sousa, P.R.; Martins, C.; Ferreira, A.; Antunes, L.; Cruz-Correia, R. Collecting, processing and secondary using personal and (pseudo) anonymized data in smart cities. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 3830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labadie, C.; Legner, C. Building data management capabilities to address data protection regulations: Learnings from EU-GDPR. J. Inf. Technol. 2023, 38, 16–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oladosu, S.A.; Ike, C.C.; Adepoju, P.A.; Afolabi, A.I.; Ige, A.B.; Amoo, O.O. Frameworks for ethical data governance in machine learning: Privacy, fairness, and business optimization. Magna Sci. Adv. Res. Rev. 2024, 7, 96–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, Y.; Nosouhi, M.R.; Cui, L.; Yu, S. Privacy preservation in smart cities. In Smart Cities Cybersecurity and Privacy; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019; pp. 75–88. [Google Scholar]

- Rao, P.M.; Deebak, B.D. Security and privacy issues in smart cities/industries: Technologies, applications, and challenges. J. Ambient. Intell. Humaniz. Comput. 2023, 14, 10517–10553. [Google Scholar]

- Daoudagh, S.; Marchetti, E.; Savarino, V.; Bernabe, J.B.; García-Rodríguez, J.; Moreno, R.T.; Martinez, J.A.; Skarmeta, A.F. Data protection by design in the context of smart cities: A consent and access control proposal. Sensors 2021, 21, 7154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Turjman, F.; Zahmatkesh, H.; Shahroze, R. An overview of security and privacy in smart cities’ IoT communications. Trans. Emerg. Telecommun. Technol. 2022, 33, e3677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rusinova, V.; Martynova, E. Fighting cyber attacks with sanctions: Digital threats, economic responses. Isr. Law Rev. 2024, 57, 135–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narasimha Rao, K.P.; Chinnaiyan, S. Blockchain-Powered Patient-Centric Access Control with MIDC AES-256 Encryption for Enhanced Healthcare Data Security. Acta Inform. Pragensia 2024, 13, 374–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, S.; Ahmed, I.; Kamruzzaman, M.; Saha, R. Cybersecurity Challenges in IT Infrastructure and Data Management: A Comprehensive Review of Threats, Mitigation Strategies, and Future Trend. Glob. Mainstream J. Innov. Eng. Emerg. Technol. 2022, 1, 36–61. [Google Scholar]

- Balayn, A.; Lofi, C.; Houben, G.-J. Managing bias and unfairness in data for decision support: A survey of machine learning and data engineering approaches to identify and mitigate bias and unfairness within data management and analytics systems. VLDB J. 2021, 30, 739–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Falco, C.C.; Romeo, E. Algorithms and geo-discrimination risk: What hazards for smart cities’ development? In Smart Cities; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2025; pp. 104–117. [Google Scholar]

- Le Quy, T.; Roy, A.; Iosifidis, V.; Zhang, W.; Ntoutsi, E. A survey on datasets for fairness-aware machine learning. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Data Min. Knowl. Discov. 2022, 12, e1452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herdiansyah, H. Smart city based on community empowerment, social capital, and public trust in urban areas. Glob. J. Environ. Sci. Manag 2023, 9, 113–128. [Google Scholar]

- Sarker, I.H. Smart City Data Science: Towards data-driven smart cities with open research issues. Internet Things 2022, 19, 100528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, L.; Guan, L. Interpretability of machine learning: Recent advances and future prospects. IEEE Multimed. 2023, 30, 105–118. [Google Scholar]

- Rashid, M.M.; Kamruzzaman, J.; Hassan, M.M.; Imam, T.; Wibowo, S.; Gordon, S.; Fortino, G. Adversarial training for deep learning-based cyberattack detection in IoT-based smart city applications. Comput. Secur. 2022, 120, 102783. [Google Scholar]

- Dutta, H.; Minerva, R.; Alvi, M.; Crespi, N. Data-driven Modality Fusion: An AI-enabled Framework for Large-Scale Sensor Network Management. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2502.04937. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, J.; Zhang, Z.; Zheng, S.; Qin, F.; Wang, Y. {DISTMM}: Accelerating distributed multimodal model training. In Proceedings of the 21st USENIX Symposium on Networked Systems Design and Implementation (NSDI 24), Santa Clara, CA, USA, 16–18 April 2024; pp. 1157–1171. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, D.-W.; Wang, Q.-W.; Qi, Z.-H.; Ye, H.-J.; Zhan, D.-C.; Liu, Z. Class-incremental learning: A survey. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2024, 46, 9851–9873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jafari, F.; Moradi, K.; Shafiee, Q. Shallow learning vs. Deep learning in engineering applications. In Shallow Learning vs. Deep Learning: A Practical Guide for Machine Learning Solutions; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2024; pp. 29–76. [Google Scholar]

- Bischl, B.; Binder, M.; Lang, M.; Pielok, T.; Richter, J.; Coors, S.; Thomas, J.; Ullmann, T.; Becker, M.; Boulesteix, A.L. Hyperparameter optimization: Foundations, algorithms, best practices, and open challenges. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Data Min. Knowl. Discov. 2023, 13, e1484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitt, M. Securing the digital world: Protecting smart infrastructures and digital industries with artificial intelligence (AI)-enabled malware and intrusion detection. J. Ind. Inf. Integr. 2023, 36, 100520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearson, M. Pioneering Urban Biodiversity: Using AI-Sensors, eDNA and Traditional Methods to Create a Novel Biodiversity Monitoring Toolkit and Assessment Framework. Master’s Thesis, Utrecht University, Utrecht, The Netherlands, 2024. [Google Scholar]

| Fusion Type | Example Models | Fusion Point | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Early Fusion | VisualBERT [34], VL-BERT [35] | Input-level | Joint transformers over concatenated modalities |

| Late Fusion | CLIP [36], ALIGN [37] | Output-level | Independent encoders, aligned via similarity |

| Hybrid Fusion | LXMERT [38], ViLBERT [39], UNITER [40], ALBEF [41], BLIP [42] | Mid-level/cross-modal layers | Modality-specific encoders + cross-attention |

| Architecture | Description | Applications in Smart Cities | Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) | CNNs are used for image processing but have been extended to integrate visual data with other modalities such as sensors or geospatial data. | Urban mobility prediction, environmental monitoring (analyzing traffic cameras and environmental sensor data). | Well-suited for spatial data analysis and can handle large-scale image data, which is common in traffic and environmental monitoring systems [47]. |

| Transformer-based Models | Transformer models, initially developed for natural language processing (NLP), use self-attention mechanisms to learn relationships across data modalities. | Image-text matching, video captioning, traffic event prediction (integrating visual and textual data). | Captures long-range dependencies across multiple modalities. Self-attention mechanism allows for flexible attention to relevant features across modalities [25]. |

| Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) | GNNs are designed to process graph-structured data, where relationships between entities are crucial for prediction tasks. | Traffic prediction, urban mobility, public safety (modeling road networks, sensors, and traffic flows). | Effectively models spatial dependencies and interconnected data across multiple sources, such as roads, sensors, and events [27]. |

| MML Technique | Accuracy (%) | Computational Complexity | Suitable Data Modalities | Application |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Deep Learning | ~90 | High | Audio, Video, Text | Urban video analytics [59,60] |

| Transfer Learning | ~85 | Medium | Sensor Data, Images | Sensor-to-sensor adaptation [61] |

| Ensemble Methods | ~88 | Low-Medium | Sensor Data, Social Media | Social sentiment and traffic data [62] |

| Graph-based Methods | ~82 | Medium | Spatial Data, Networks | Traffic network inference [63] |

| Reinforcement Learning | ~87 | High | IoT Data, Control Systems | IoT-based adaptive control [64] |

| Authors | Model/Approach | Pros | Cons |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ouoba et al. [69] | Multimodal Journey Planning | Addresses fragmented environments by integrating real-time data for comprehensive planning. | May require large computational resources for real-time data processing. |

| Botea et al. [70] | Risk-Averse Journey Advising | Accounts for uncertainties in public transport schedules, improving system reliability. | Does not fully address long-term dynamic changes in urban mobility. |

| Asgari et al. [71] | Multimodal Trajectories | Uses unsupervised models, effective for forecasting traffic flow without needing labeled data. | May struggle with real-time adjustments or highly dynamic urban environments. |

| Alessandretti et al. [72] | Public Transportation Networks | Leverages data-driven models to analyze complex transport networks, improving planning and efficiency. | Might be less effective in highly decentralized, less connected urban settings. |

| Pronello et al. [73] | Travel Behavior | Provides insights into behavioral shifts using multimodal data, improving transportation planning. | Requires large amounts of data to detect subtle shifts in behavior and patterns. |

| Kang and Youm [74] | Extended Public Transport | Improves route optimization, enhancing public transportation efficiency. | Complexity increases with the number of variables and real-time adjustments needed. |

| Sokolov et al. [75] | Digital Railway Infrastructure | Integrates digital frameworks to optimize railway systems and reduce urban congestion. | High computational complexity and infrastructure requirements for implementation. |

| Young et al. [76] | Smart-Citizen Engagement | Leverages multimodal data for interactive city management, improving citizen engagement. | May face challenges in data privacy and ethical concerns when dealing with citizen data. |

| Kumar et al. [77] | Crowd Monitoring | Enhances public safety through intelligent monitoring systems for crowd management. | It can be costly and difficult to scale across large urban areas without specialized infrastructure. |

| Zhang et al. [78] | Vehicle Tracking | Improves vehicle tracking accuracy in complex urban environments by combining multiple data sources. | Requires continuous data input and faces challenges in real-time tracking in highly dynamic settings. |

| Fusion Strategy | Best Used When | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Early Fusion | Modalities are tightly coupled and aligned | Traffic forecasting using CCTV + GPS |

| Late Fusion | Modalities are independent or asynchronous | Healthcare: EHR + Wearables |

| Hybrid Fusion | Task requires both individual and joint representations | Public safety: video + audio + social media |

| Challenge | Proposed Solution(s) | References |

|---|---|---|

| Multimodal Representation Learning | Feature Fusion, Transfer Learning | [1,51] |

| Cross-modal Alignment | Cross-modal Attention Mechanisms, Multi-modal Transformers | [25,53] |

| Scalability and Real-time Constraints | Distributed Computing, Cloud Infrastructure, Edge Computing | [54,55] |

| Robustness to Missing or Noisy Modalities | Data Imputation, Robust Training Methods, Noise Reduction | [56,57] |

| Interpretability of Models | Explainable AI Techniques, Model Visualization | [58,59] |

| Dataset and Benchmark Limitations | Standardized Datasets, Synchronized data, Robust Benchmarks, Composite metrics, Open Benchmarks. | [1,5] |

| Aspect | Description | Example in Smart Cities |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | Representation learning refers to the process of transforming raw data from different modalities into a shared latent space where they can be compared or combined. | In smart cities, this involves mapping data from traffic cameras and social media into a unified feature space to analyze traffic congestion in relation to weather [74,80]. |

| Goal | to create a common feature space that allows for the effective comparison and integration of different data types. | By aligning traffic images and weather data, MML models create a joint representation that helps to analyze traffic congestion during different weather conditions [60]. |

| Applications | It is widely used in cross-modal retrieval, where a system retrieves relevant data from one modality based on a query from another modality. | Cross-modal retrieval might involve retrieving relevant satellite images of an area based on textual descriptions about a traffic incident [58,81]. |

| Advantage | Learning shared representations allows for more context-aware decision-making, enabling models to integrate diverse insights more effectively. | By learning a joint representation, a smart city system can combine sensor data with social media sentiment to better respond to traffic incidents or public safety concerns. |

| Challenges | One challenge is ensuring that the representations learned are semantic and meaningful across different modalities, which require careful design and training. | In smart cities, aligning audio data (e.g., traffic sounds) with visual data (e.g., traffic cameras) may require sophisticated models to capture spatial and temporal context. |

| Aspect of Smart City | Impact of MML | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Transportation | ~20% Reduction in Traffic Congestion [78] | Achieved through traffic flow prediction, adaptive signals and incident detection. |

| Energy Management | ~15% Increase in Energy Efficiency [64] | Enabled by demand forecasting and optimized grid operations via MML. |

| Public Safety | Up to ~30% Reduction in Emergency Response Times [12] | Real-time data fusion improves emergency detection and resource dispatch. |

| Environmental Monitoring | Improved Air Quality Monitoring and Health Risk Reduction [111] | Sensor data integration helps in pollution forecasting and alerts. |

| Urban Planning | ~10% Improvement in Urban Infrastructure Efficiency [13] | Supports better zoning, infrastructure usage, and investment decisions. |

| Priority | Research Direction | Description |

|---|---|---|

| High | Handling Big Data [152] | Developing scalable MML algorithms for large datasets |

| High | Addressing Privacy and Ethical Concerns [142] | Investigating methods for preserving privacy in MML models |

| Medium | Improving Model Interpretability [153] | Exploring techniques for explaining complex MML models |

| Medium | Enhancing Robustness [154] | Researching strategies for improving the robustness of MML |

| Emerging | Exploring Novel Data Modalities [155] | Investigating the use of emerging data modalities in MML |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Sadiq, T.; Omlin, C.W. Sensing in Smart Cities: A Multimodal Machine Learning Perspective. Smart Cities 2026, 9, 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/smartcities9010003

Sadiq T, Omlin CW. Sensing in Smart Cities: A Multimodal Machine Learning Perspective. Smart Cities. 2026; 9(1):3. https://doi.org/10.3390/smartcities9010003

Chicago/Turabian StyleSadiq, Touseef, and Christian W. Omlin. 2026. "Sensing in Smart Cities: A Multimodal Machine Learning Perspective" Smart Cities 9, no. 1: 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/smartcities9010003

APA StyleSadiq, T., & Omlin, C. W. (2026). Sensing in Smart Cities: A Multimodal Machine Learning Perspective. Smart Cities, 9(1), 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/smartcities9010003