1. Introduction

The phenomenon of urbanization has been occurring at an accelerated pace, with more than half of the world’s population now living in urban areas, a percentage that may exceed 60% by 2030 [

1]. As the Global South becomes more and more urbanized, infrastructure inequality also increases, and greenspace is lost [

2,

3]. Such growth brings with it an increase in impervious surfaces, such as concrete and asphalt, to the detriment of permeable and vegetated areas, leading to a rise in surfaces with low albedo [

4,

5,

6,

7]. This means greater absorption of solar radiation and a reduction in the shading of open spaces. These transformations are closely linked to the effects of Urban Heat Islands (UHIs), a phenomenon in which urban areas exhibit significantly higher temperatures than their rural surroundings [

7,

8,

9].

Global climate change has contributed to aggravating the effects of UHIs, since the increase in the planet’s average temperature intensifies thermal extremes in cities [

6,

7,

10]. Studies indicate that cities such as Medellín, São Paulo, and record air temperature increases in UHI regions ranging between 5 °C and 7 °C, directly impacting energy consumption, air quality, and population well-being [

8]. The occurrence of UHIs directly affects people’s health, worsening heat stress, which increases the incidence of myocardial infarction, stroke, sunstroke, heat exhaustion, and mortality during heat waves [

11,

12]. In tropical regions, where climatic conditions are naturally hot and humid, there is an urgent need to develop mitigation measures against UHI effects [

9,

10,

13].

The study of these phenomena has been expanded through the use of microclimatic simulation tools, such as the ENVI-met software 5.7, which allows modeling the interaction between buildings, soil, and vegetation [

14]. However, most research using this tool has been developed for temperate climates, with a significant shortage of studies focusing on tropical regions [

10,

11]. This gap is even more pronounced for informal settlements within these tropical cities [

13]. Slums and favelas, with their unique urban morphology—defined by high density, informal materials, and organic layouts—are critically under-researched. The inherent difficulties of conducting on-site measurements, due to safety and structural instability, make computational simulations essential for studying their microclimates [

13,

15].

In Brazil, few studies tackle the formation of Urban Heat Islands (UHIs) in favelas. As defined by the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics, favelas and poor communities are territories that lack assistance and rights, including—but not limited to—sanitation, legal titles, property rights and infrastructure, often located in areas with restricted occupation, such as environmental risk sites [

16], and have seen continuous, unregulated growth over recent decades. In Rio de Janeiro, these communities are home to a substantial part of the city’s population; the 2022 census recorded 1.3 million people living in 813 favelas, constituting 21.73% of the city’s total [

17]. Given such intense and dense development, the novel concept of thermal justice provides a crucial framework for understanding their microclimatic conditions [

18]. Analyzing their microclimate is essential not only to address issues of urban comfort but also to identify thermal patterns that could become more prevalent across the entire city.

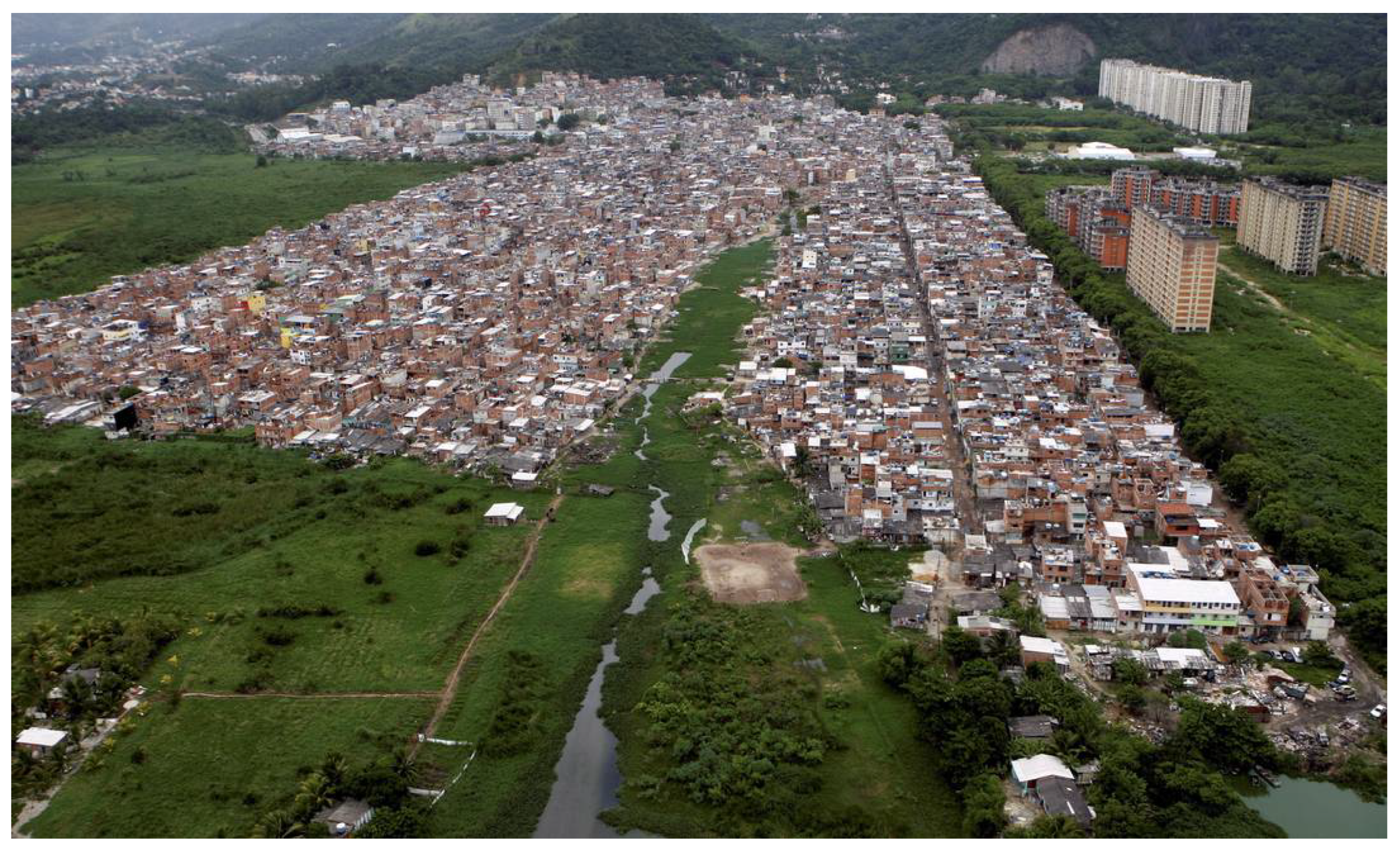

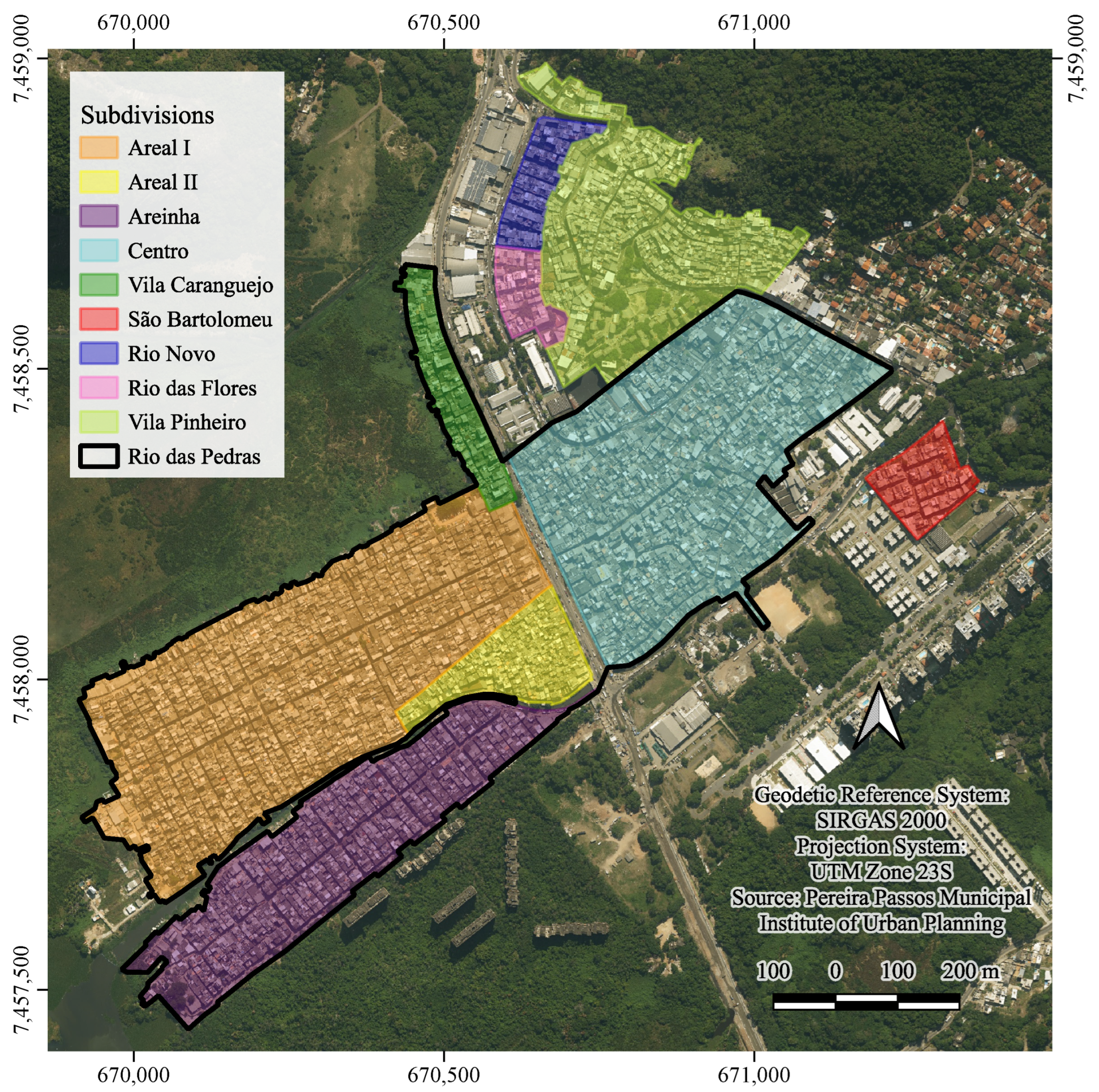

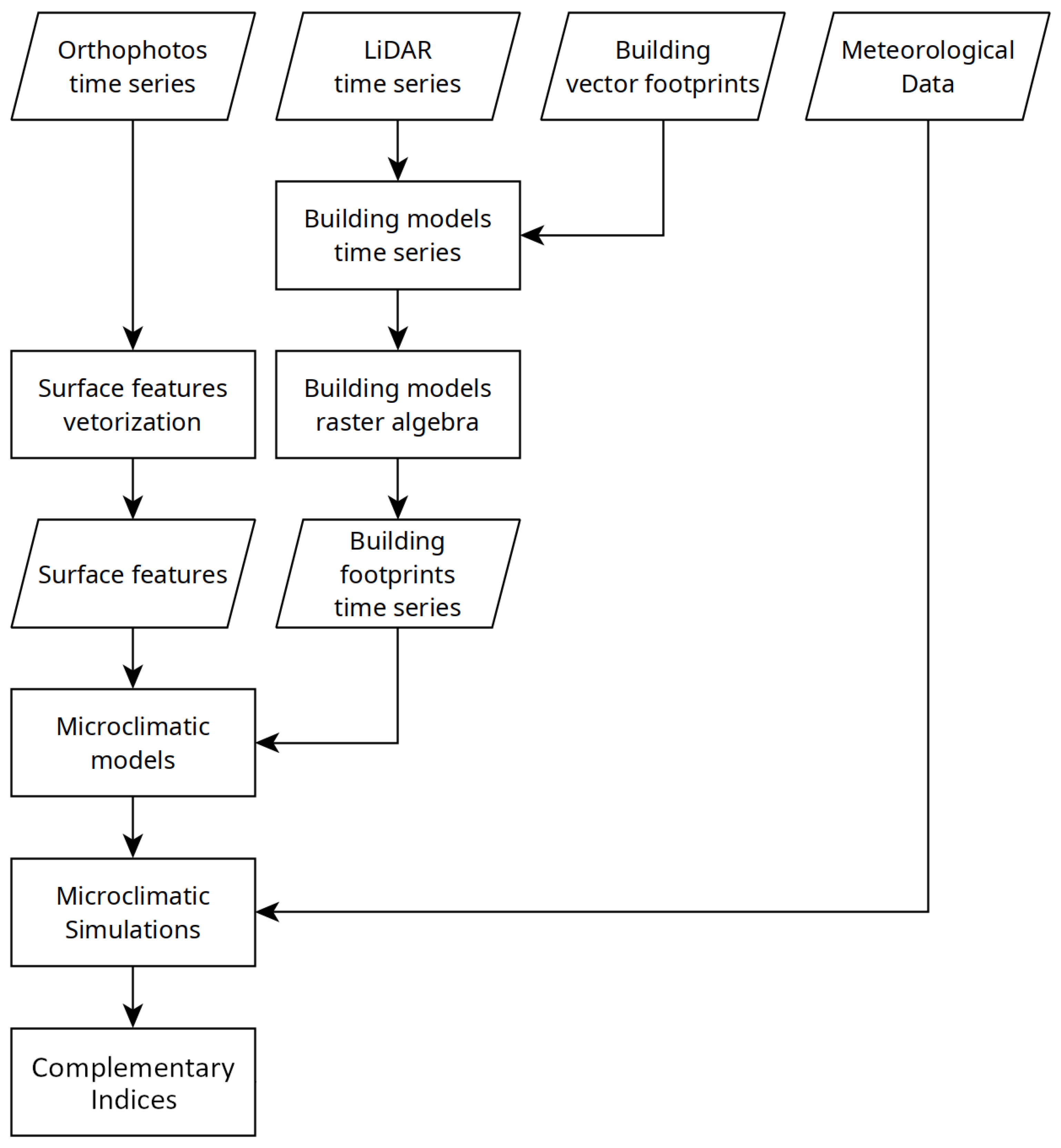

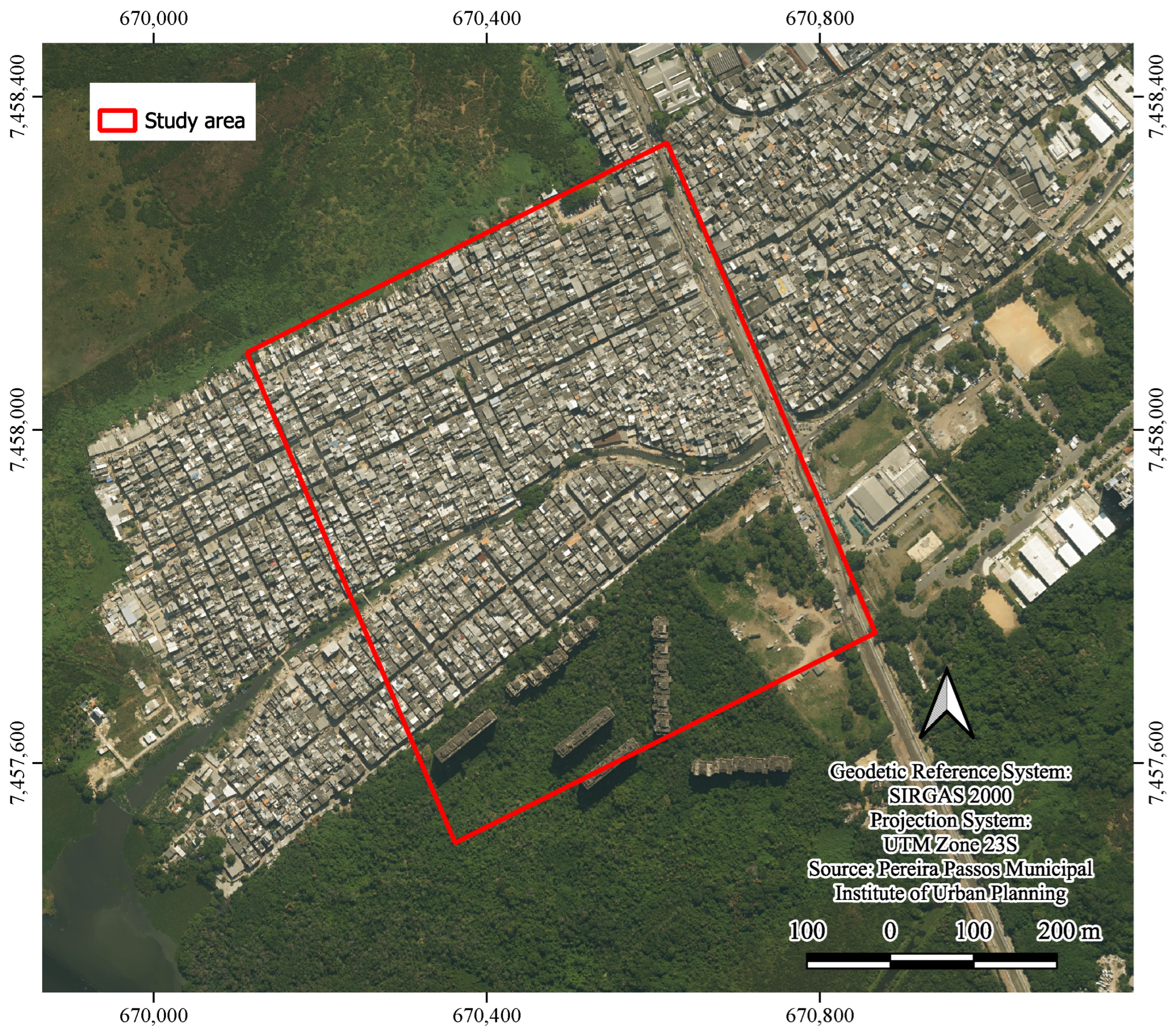

This article takes the Rio das Pedras favela in Rio de Janeiro as its study area: an environment where a tropical climate intersects with unregulated urban development. This study therefore aims to gather results from microclimate simulations for Rio das Pedras using the ENVI-met software [

19], while establishing a protocol for geospatial data input and preprocessing to produce precise microclimate-relevant maps. The site was selected due to its notable vertical growth [

20], maximizing its potential for environmental planning simulations. Additionally, abundant geospatial data, including vector bases, digital surface models, and precise orthophotos, were available, ensuring optimal conditions for the experiment.

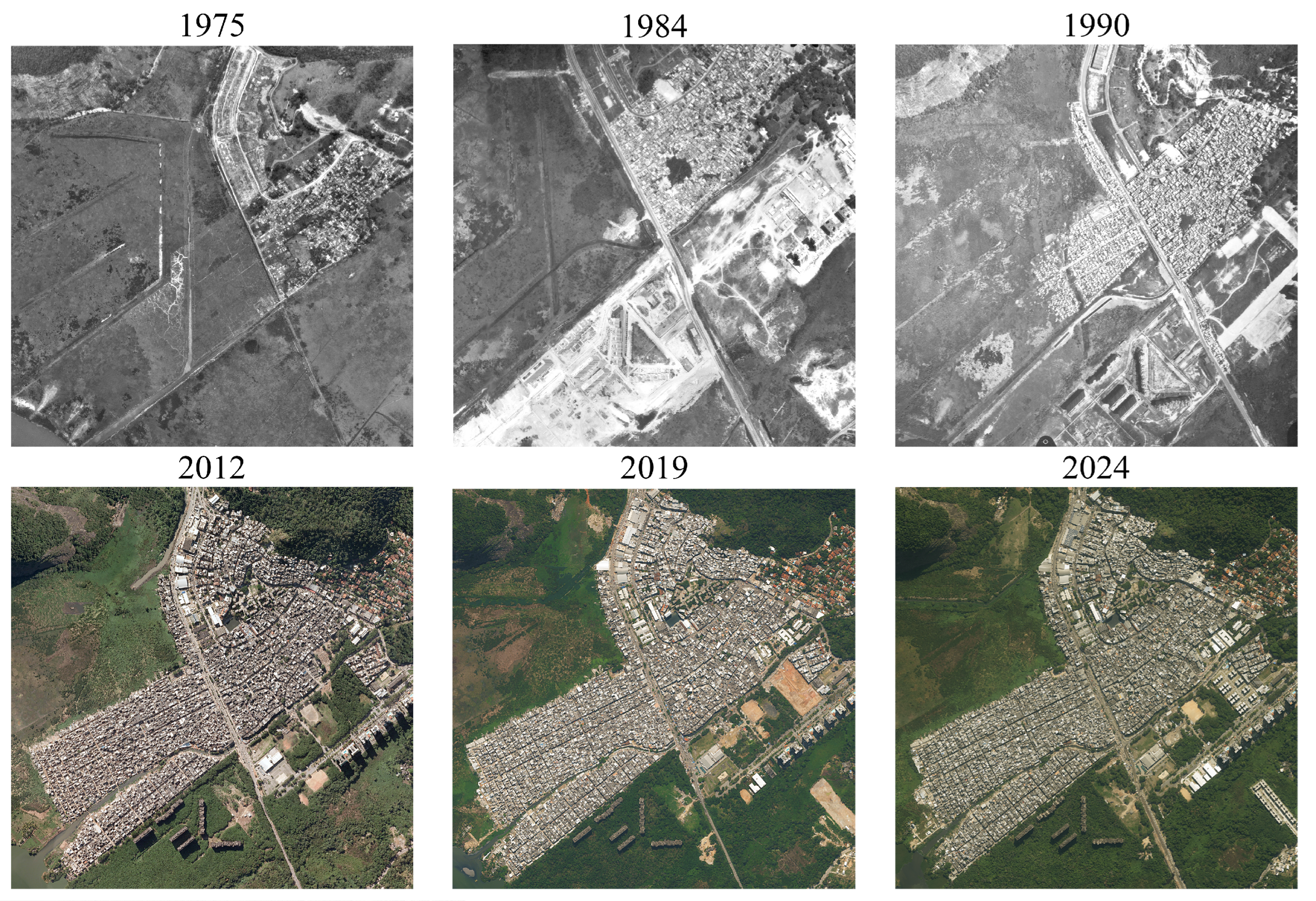

The study verified urban morphological changes in Rio das Pedras—particularly verticalization—and assessed their influence on the local microclimate, confirming the occurrence of microclimatic changes and identifying key elements contributing to temperature variations. Three temporal scenarios (2013, 2019, and 2024) were defined, with morphological data specific to each period while climatic data remained constant. To this end, Digital Surface Models were generated for all three years and converted into precise cartographic datasets, which supported the development of distinct 3D microclimatic simulation models, thereby enabling a comprehensive assessment of morphological and microclimatic changes over time.

This article aims to contribute to the debate on climate-resilient urban planning, evaluating the impact of unregulated urban growth and studying strategies to mitigate the negative impacts of UHIs in tropical climate regions. By integrating microclimatic simulations with analyses of urban morphology, it is expected to provide support for policies that promote improved habitability in cities facing microclimatic changes.

3. Results

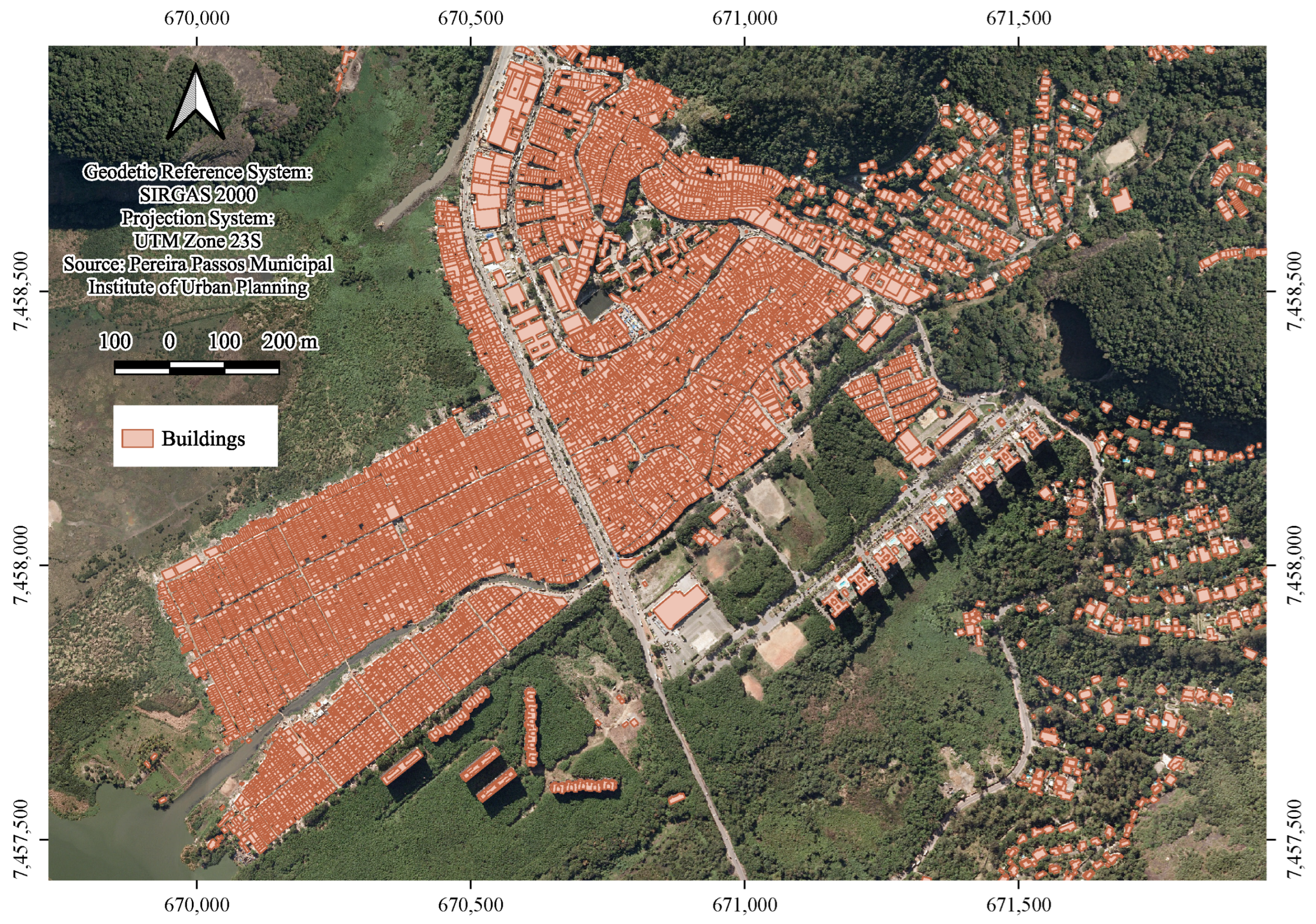

3.1. Update of the Cartographic Base and Vertical Growth

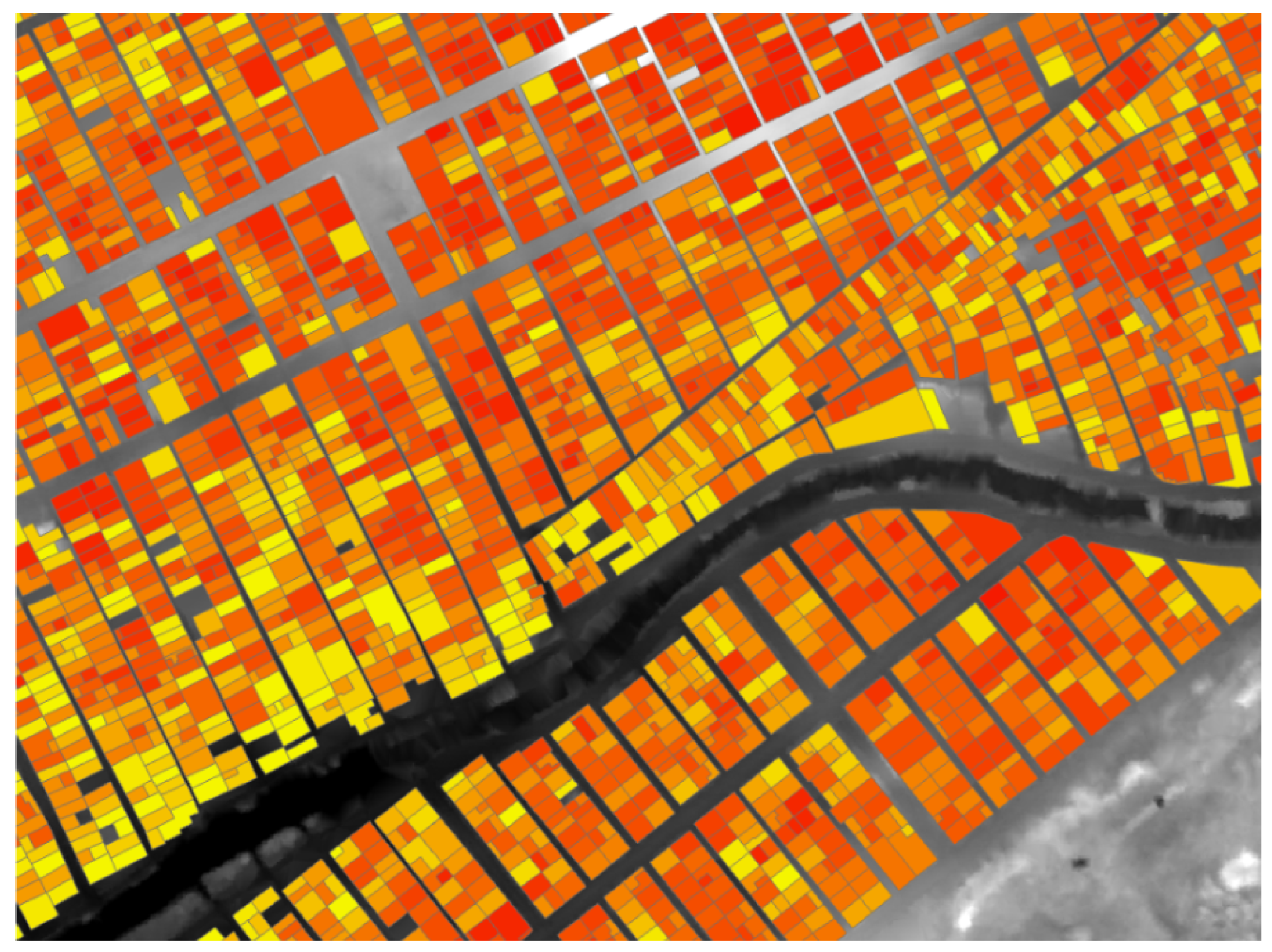

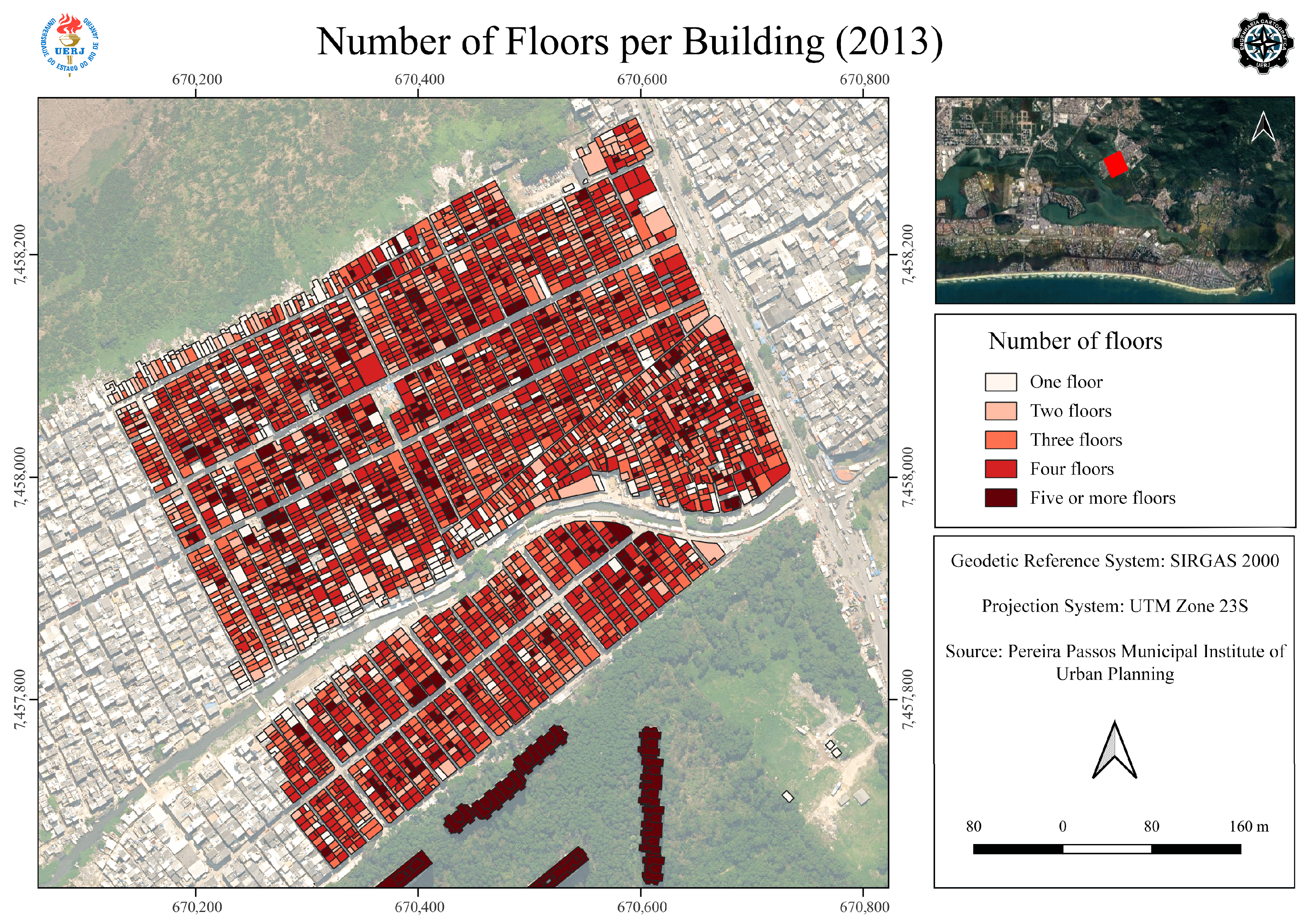

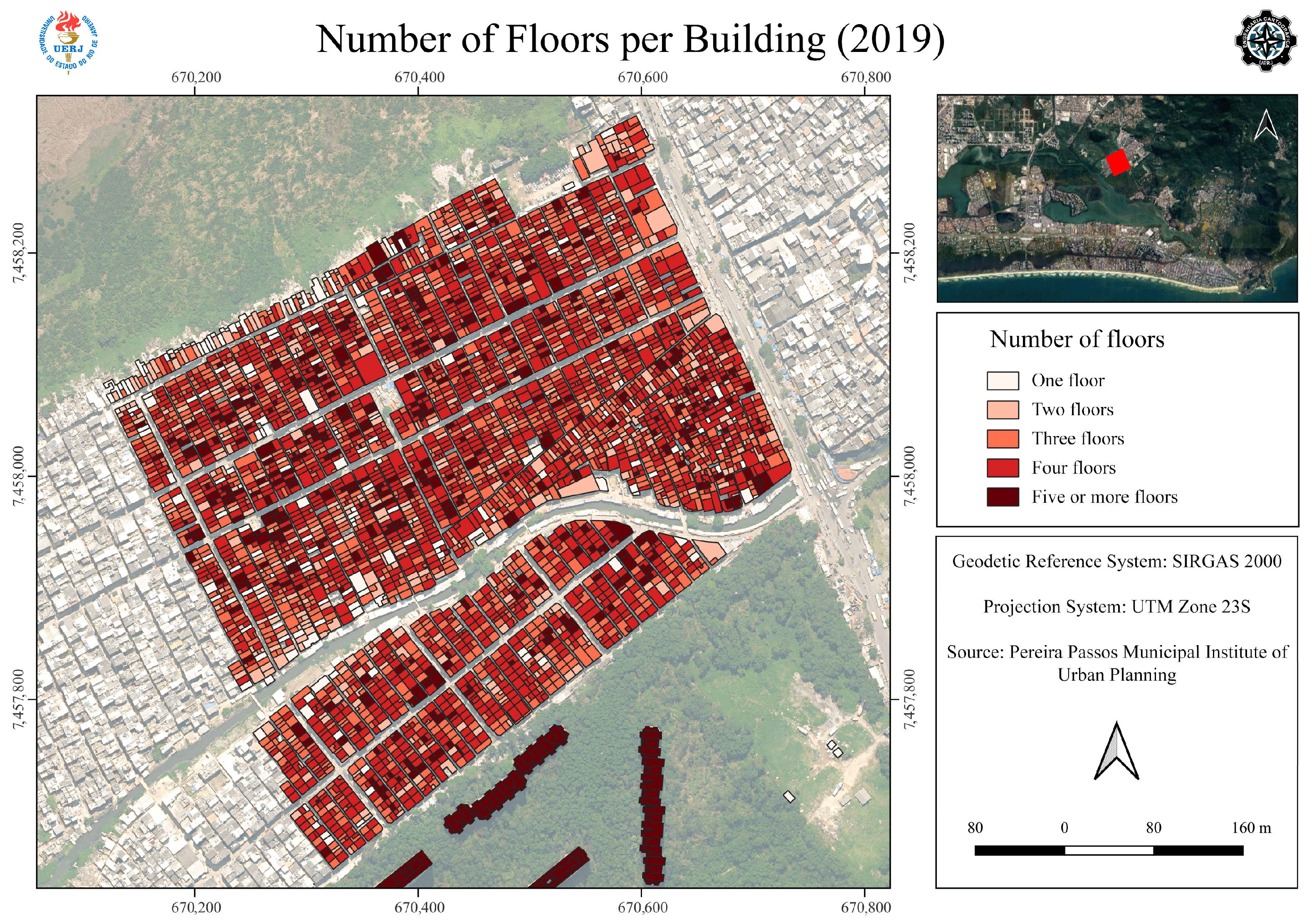

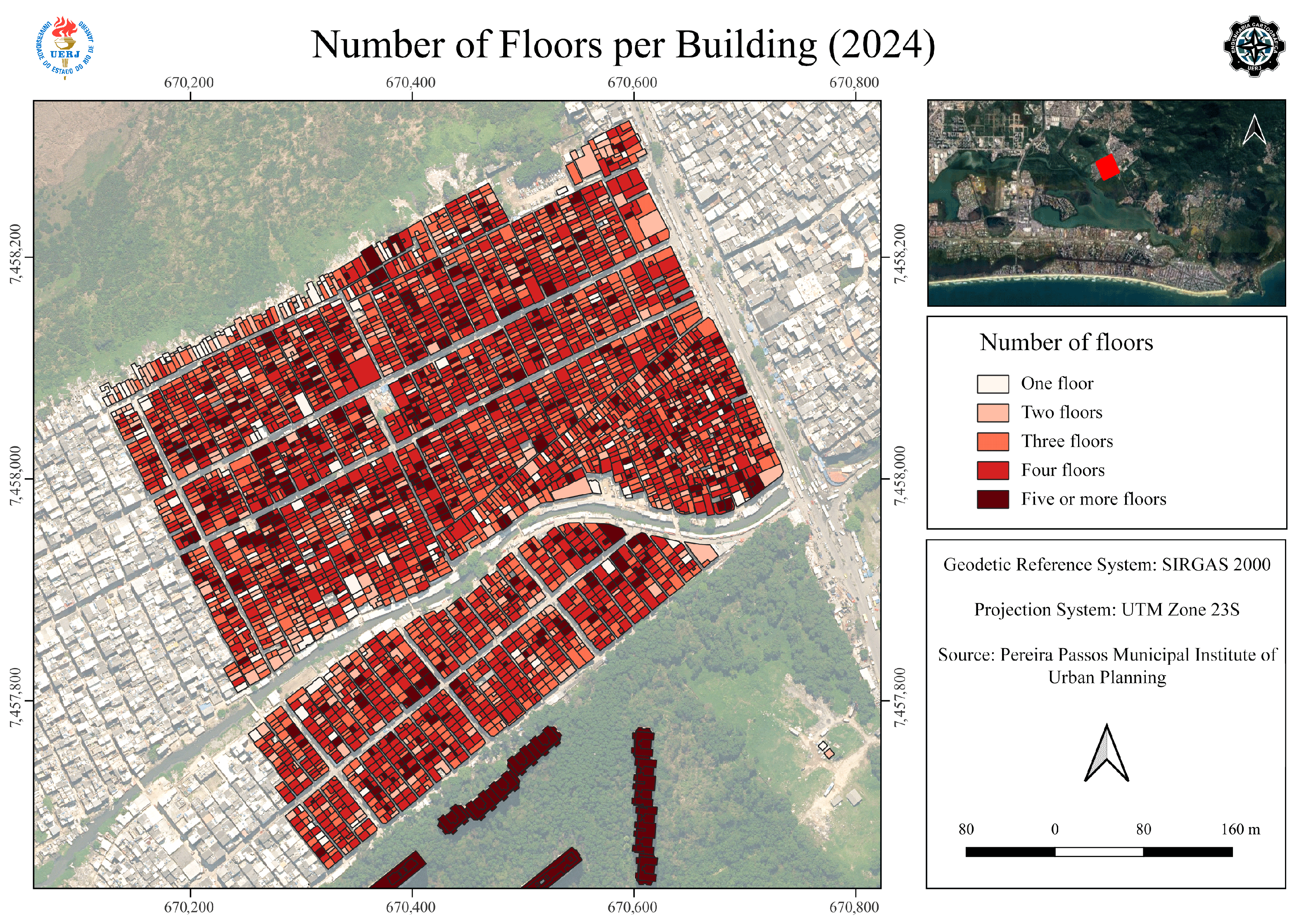

Figure 12,

Figure 13 and

Figure 14 present the results related to the update of the building cartographic base in the study area. This includes the clipping used for 2013 and the subsequent updates for the years 2019 and 2024, which were essential for the creation of the microclimate models.

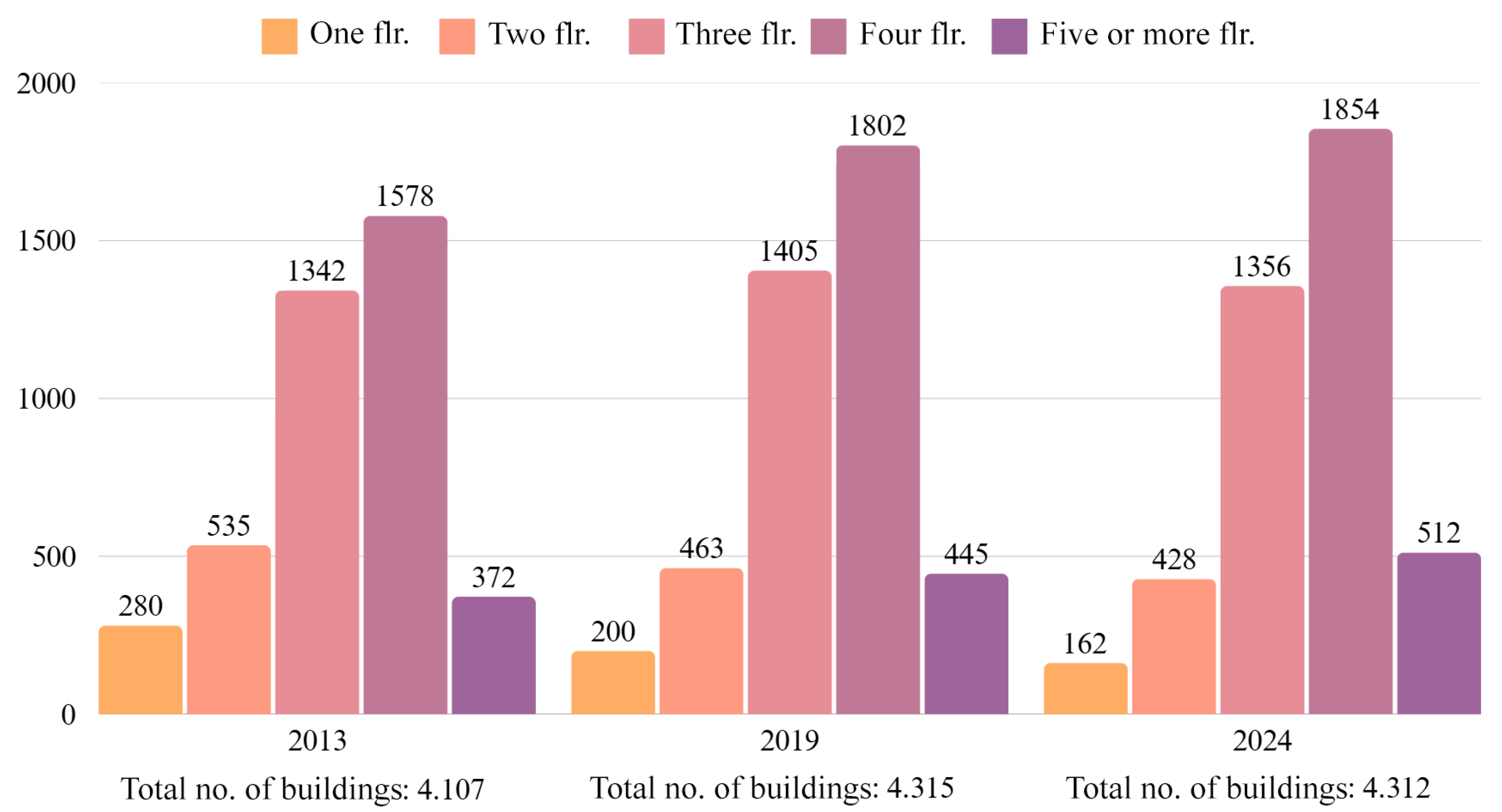

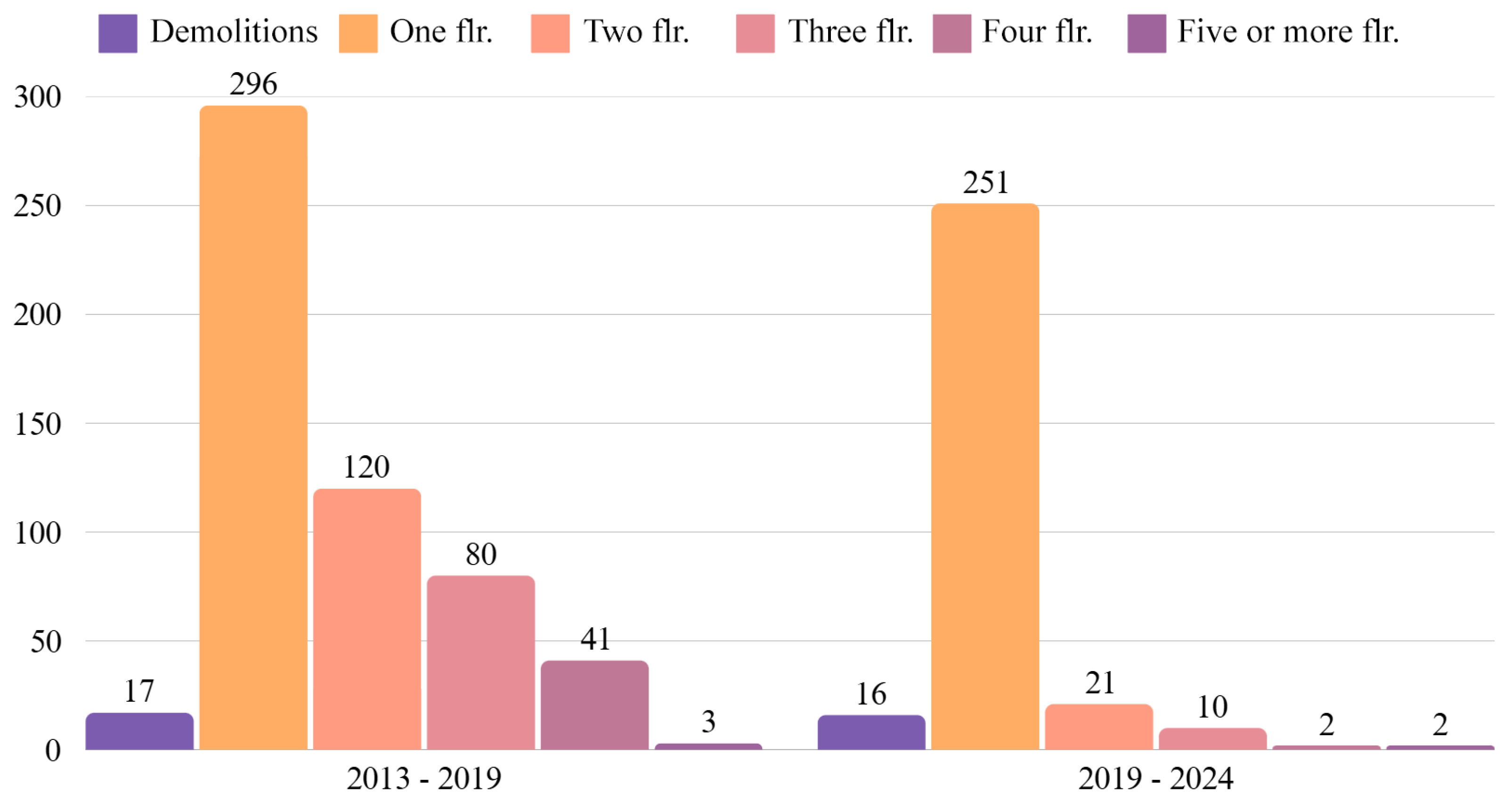

The data are categorized by the number of floors per building, with the values detailed in

Figure 15. The analysis shows a clear increase in the number of buildings between 2013 and 2019. This was follows: by a slight decrease in the total number of structures between 2019 and 2024.

However, this net decrease is compensated for by significant changes in the building stock. The period saw the construction of new, taller buildings and alterations to existing ones, where parts of structures had additions built in different forms. This resulted in many buildings now having two or more distinct height values.

It is observed that there was greater land occupation between 2013 and 2019, though still limited, as the area was already densely developed horizontally by 2013. Between 2019 and 2024, there was virtually no change in terms of horizontal expansion, but vertically, the favela grew considerably. This can be explained by the merging of smaller structures—such as houses—into larger buildings, transforming several polygons into one and resulting in fewer polygons overall, without reducing horizontal land coverage.

The growth rate of built-up area is significant. According to

Figure 15, there was a 42.14% reduction in single-story buildings and a 27.34% increase in buildings with five or more floors. These two comparisons alone already demonstrate the marked verticalization of the region over the past ten years.

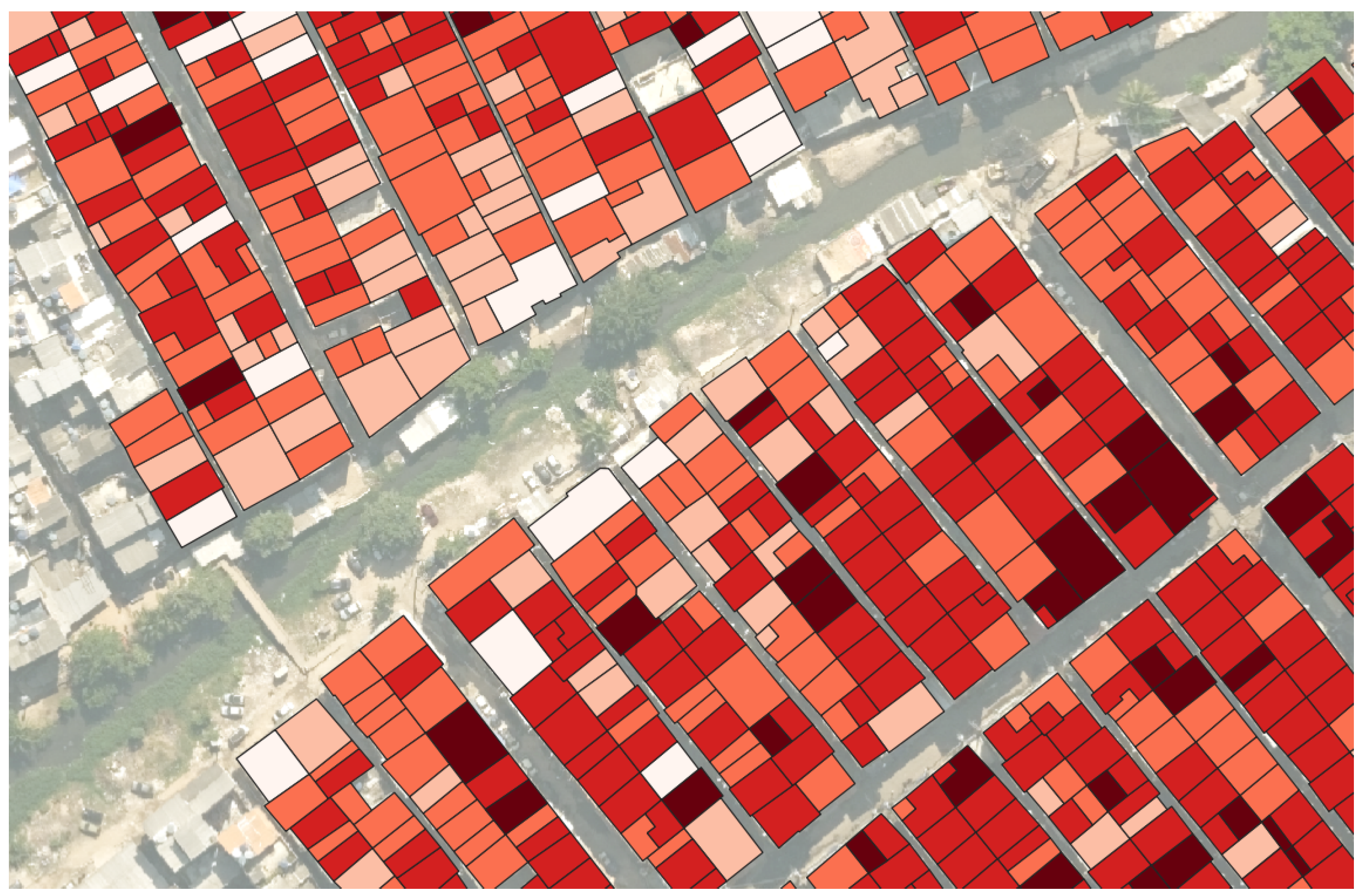

The methodology deliberately disregarded buildings less than 3 m in height. Consequently, the most precarious structures located along the riverbanks—mainly shacks, some with heights under 2 m—were not classified (

Figure 16). Therefore, while the resulting data may appear to show that the riverbanks are completely clear, the actual wind “corridor” was, in fact, a few meters narrower than the models indicate.

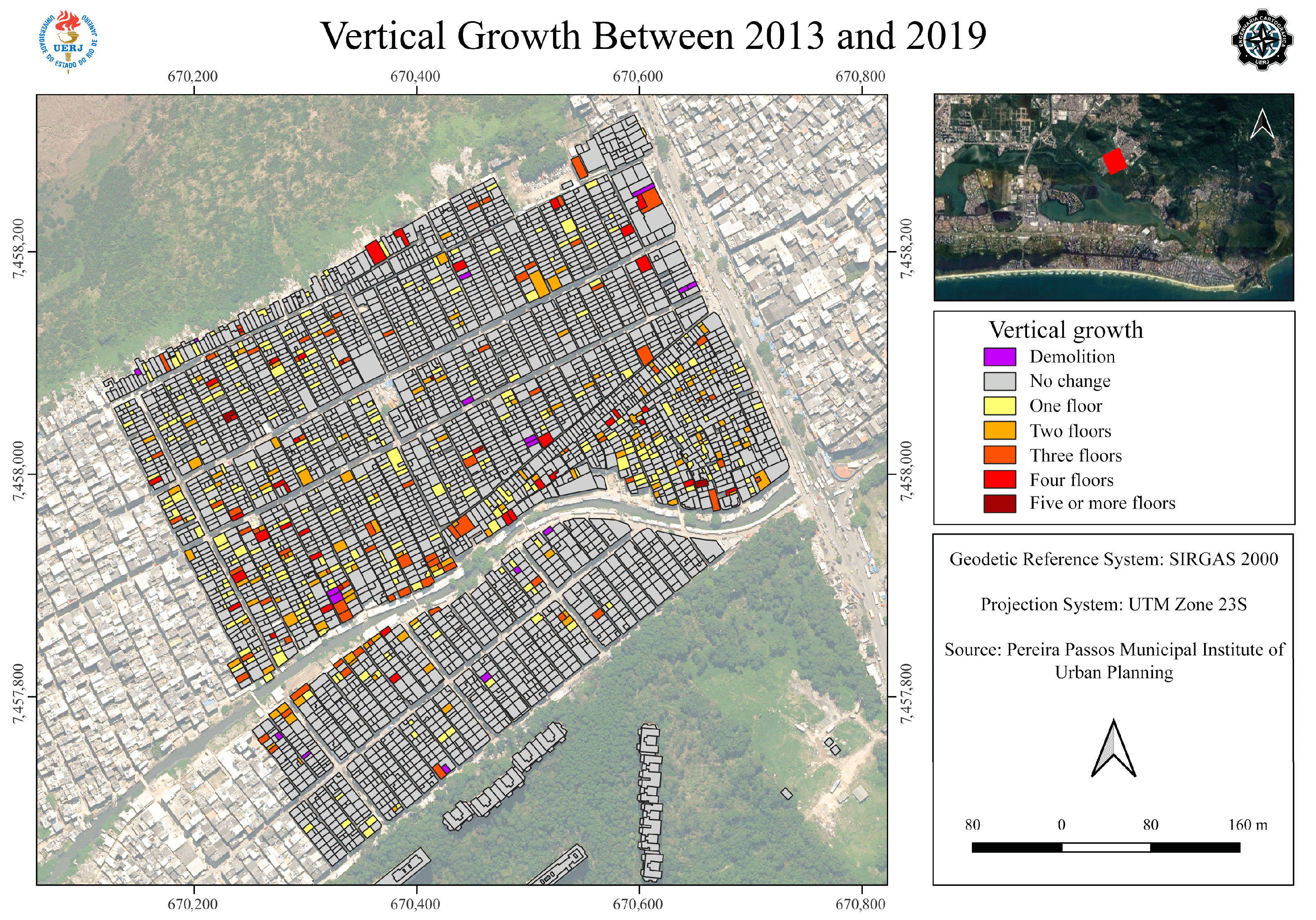

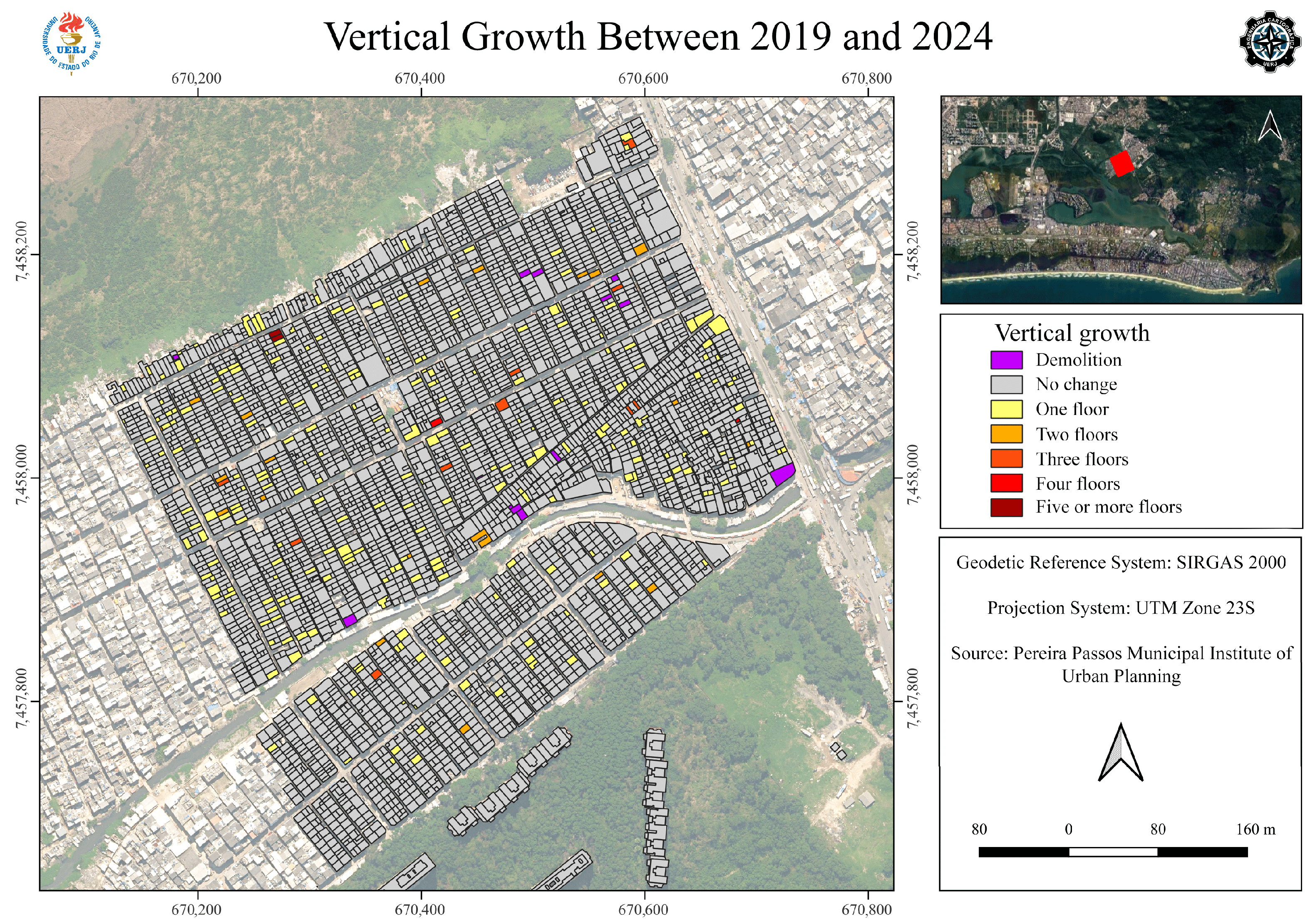

Figure 17 and

Figure 18 show the growth in buildings over time, highlighting where the main territorial changes occurred.

Figure 19 presents the numerical increase in floors between periods, indicating changes in the area’s verticalization. In the first interval (2013–2019), a significant number of buildings received one to four additional floors, notably 296 buildings with one additional floor and 120 with two floors.

In the second period (2019–2024), there was a sharp decline in vertical growth, with only 21 buildings gaining two floors, 10 gaining three, and only two gaining four. The number of demolitions remained stable, as did the number of buildings with one added floor and those unchanged, suggesting saturation or a slowdown in the verticalization process. This may be due to the Brazilian economic crisis that worsened after 2017 and continued to impact the construction sector, especially until 2023, as well as the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic from 2020 to 2022 [

53,

54].

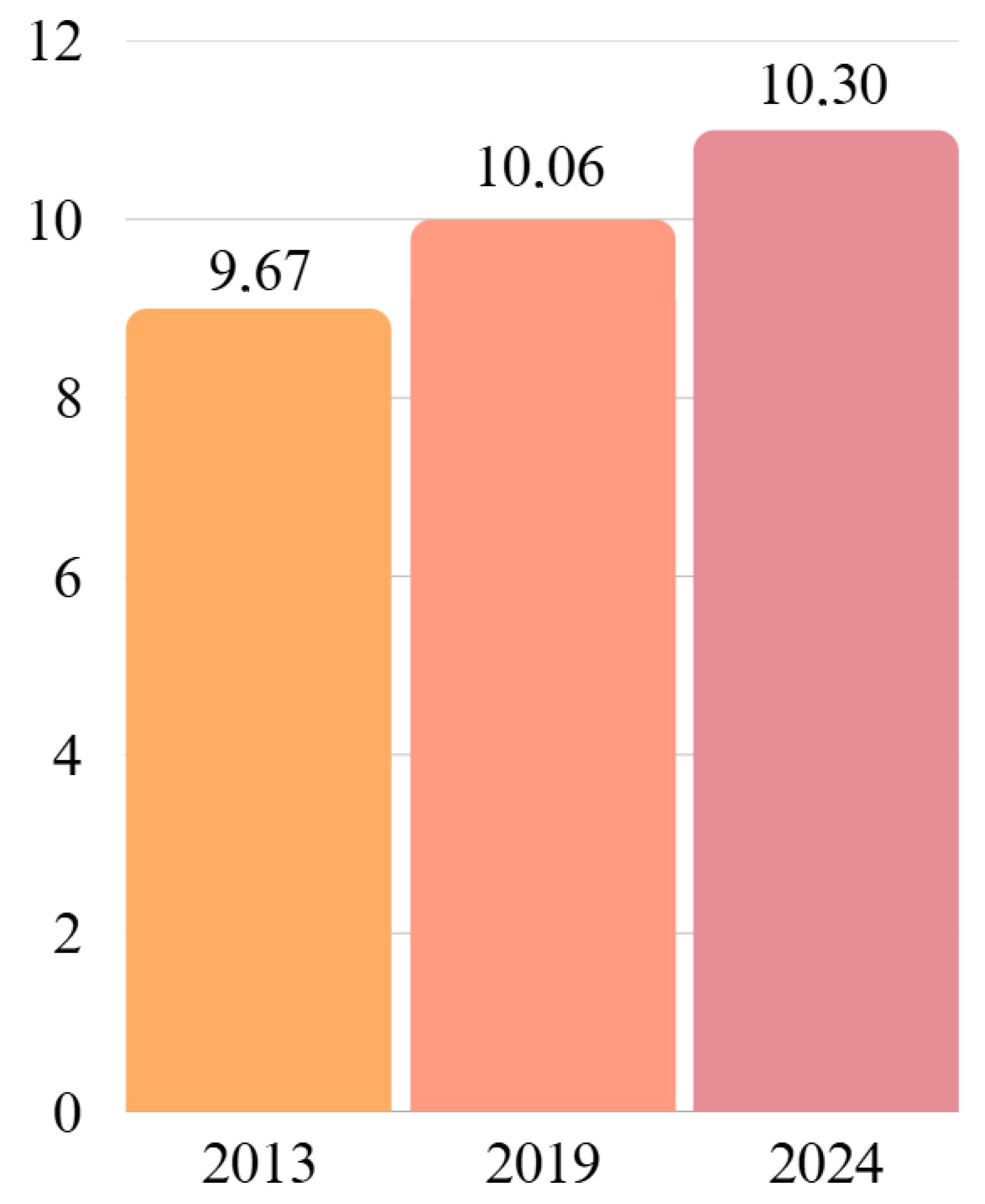

In addition, the average building heights were calculated for the three time periods (

Figure 20). The average height in 2013 was 9.67 m; in 2019 it was 10.06 m; and in 2024, it reached 10.30 m. These values indicate that the study area experienced an average height increase of approximately 0.63 m over eleven years.

Figure 17 shows that vertical changes were more concentrated on the “edges” of the territory, though still fairly spread out, especially along the northern margin of the region. A comparison of

Figure 17 and

Figure 18 reveals that most demolitions occurred in recent years (after 2019), which may indicate even greater verticalization in the coming years, as plots of land may be cleared for new construction.

3.2. Microclimatic Simulations

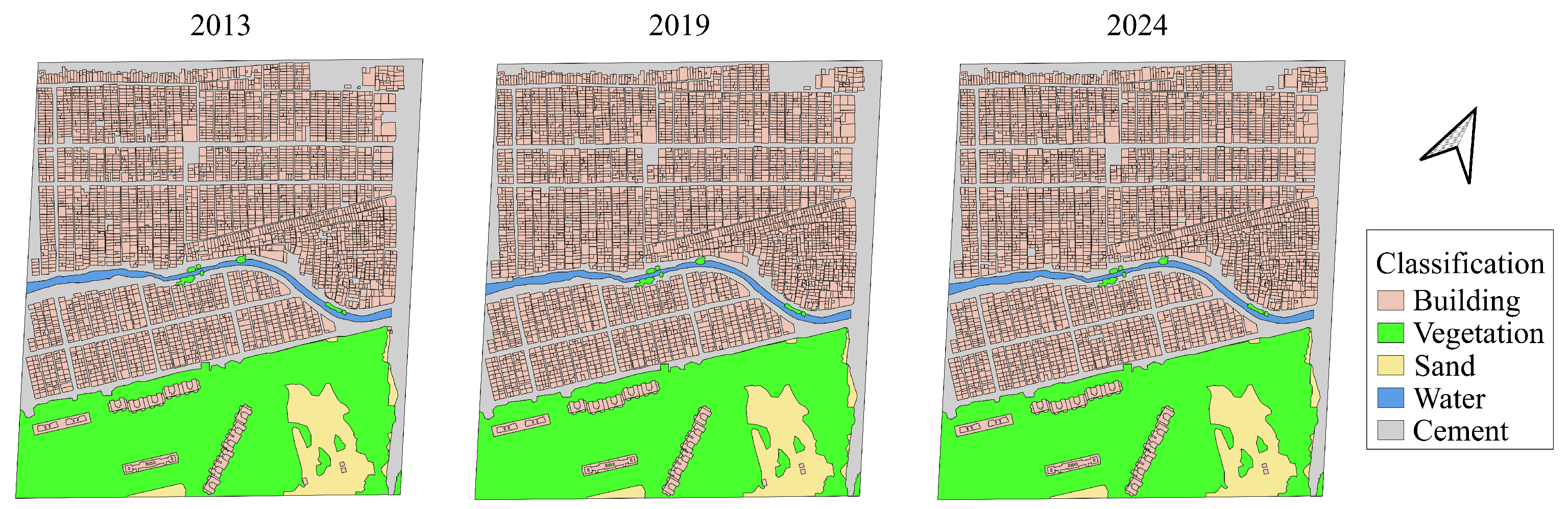

Figure 21 presents a graphical representation of the components of the microclimate models generated, which were used as the basis for the microclimatic simulations. The models included buildings and vegetation as elements, along with sand, water, and cement as terrain components. The major critical differences between models refer to the Z-value of buildings, which shows the major change between the three time periods refer to verticalization.

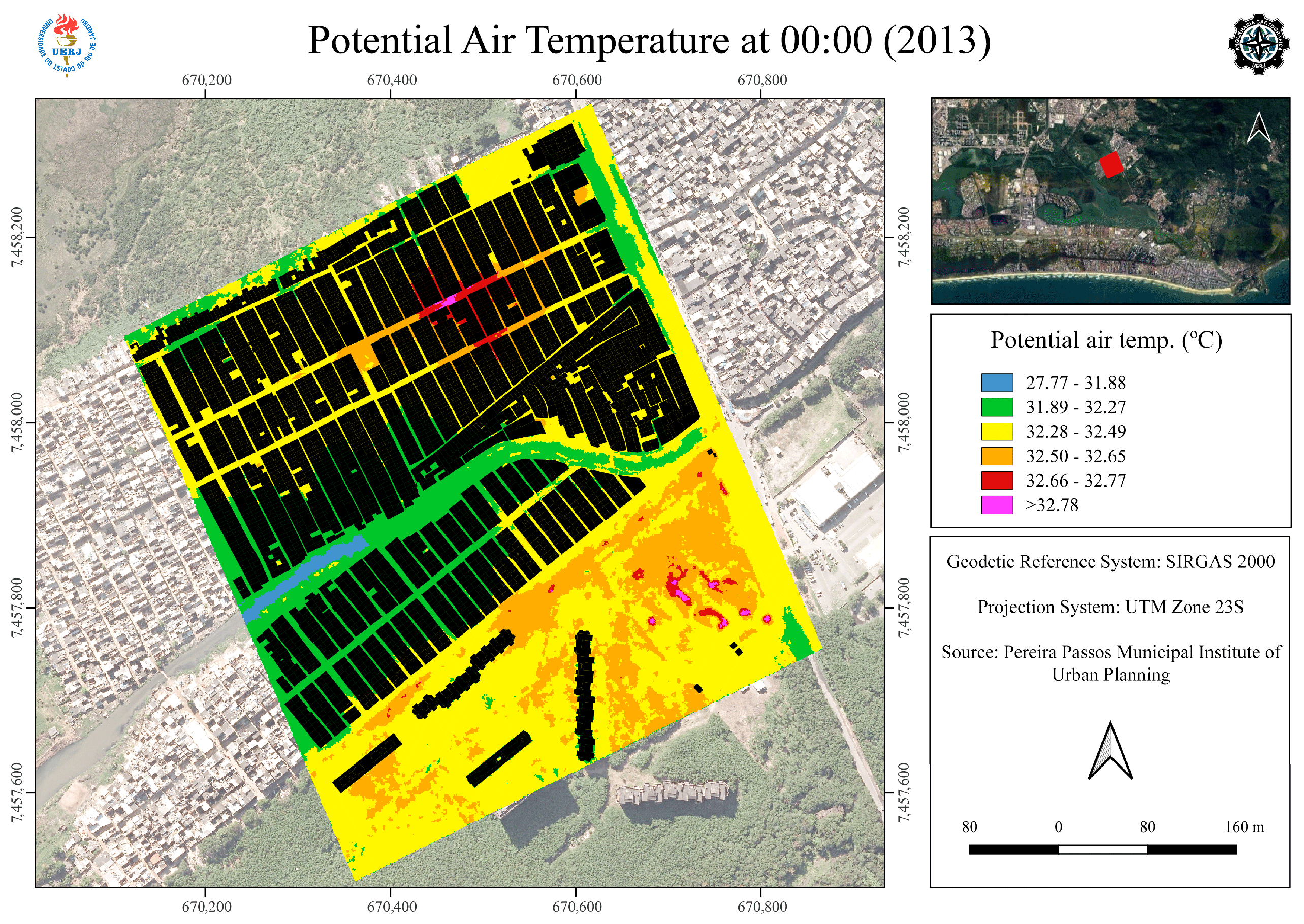

The results of the microclimatic simulations, focusing on the potential air temperatures observed during the three periods, at midnight are found in

Figure 22,

Figure 23 and

Figure 24. The models showed consistent spatial air temperature patterns throughout the years, with a notable persistence of heat islands for hours after sunset. This behavior may be associated with heat retention by construction materials, which release heat slowly over time, as well as a lack of green areas and sufficient spacing between buildings, contributing to the formation of urban heat islands [

6]. Overall, the three simulations consistently show a notably intense heat island in the northern part of the study area, with lower temperatures along the riverbank but not in the open area near the abandoned Delfim buildings.

While microclimate involves many elements (wind, humidity, solar radiation), this study uses potential air temperature at 1.5 m—a height relevant to most people—as a sensitive and socially understandable indicator of microclimatic change, despite the broader influence of other climatic elements. This height also circumvents several problems recently identified with rooftop-level strategies [

55], while producing results that demonstrate greater consistency in validation by different researchers.

3.3. Building Elevations and Potential Air Temperatures

Figure 25 presents a composite map correlating building heights with the simulated potential air temperature for 2024, where building elevation is indicated by darker shades of gray. The map reveals a distinct and intense heat island, with temperatures exceeding 32.78 °C, situated in an area characterized by a high density of the tallest buildings. This contrasts with other parts of the favela, where both the potential air temperature and average building height are lower.

This pattern underscores the significant influence of urban morphology on local climate [

56]. A visual correlation stems: the peak maximum air temperature (indicated in red/pink) coincides precisely with the region of highest elevation and the most concentrated cluster of tall buildings. Conversely, the minimum air temperature (shown in blue) is located in the topographically lowest area, corresponding to the deepest part of the stream, where natural features likely promote cooling.

Furthermore, the consistency across all three temporal simulations is notable; each shows a marked heat island effect concentrated in the same central spot. This persistent hotspot is encircled by the favela’s tallest structures and is situated considerably far from the moderating influences of the riverbank and its sparse vegetation. The thermal gradient across the study area is substantial, with a difference of nearly five degrees Celsius between the coolest and hottest regions, highlighting the extreme microclimatic variability generated by the urban form.

3.4. Simulated Microclimate Evolution over Three Time Periods

A preliminary visual inspection of the three simulations reveals a strong similarity, primarily due to their agreement on the location of the main urban heat island and a consistent overall temperature range. This suggests the foundational urban morphology [

56] has remained the dominant microclimatic force over the entire period. However, a focused contrast between the years uncovers a critical trend: from 2013 to 2024, the change is characterized by a unilateral warming. Specifically, across the whole interval (i.e., between 2013 and 2024), analysis shows isolated pockets where air temperatures increased at an average rate of up to 0.46 °C, with no observable areas exhibiting a decrease. As seen in

Figure 26, these small, yet noticeable changes, cover most of the study area.

This pattern of monotonic intensification suggests a correlation with urban development data. These warming pockets consistently align with areas that underwent vertical building expansion (represented in yellow), indicating that localized densification (even from just a few buildings) is a primary driver of microclimatic warming in this environment, layering additional heat onto the existing stable framework. The riverbank (particularly along its wid est section) was the only area where variations in building height did not increase air temperature. However, a small strip of the western riverbank constituted an exception, showing a temperature increase. This specific area has experienced particularly intense construction.

3.5. Complementary Indices for the Simulation Date

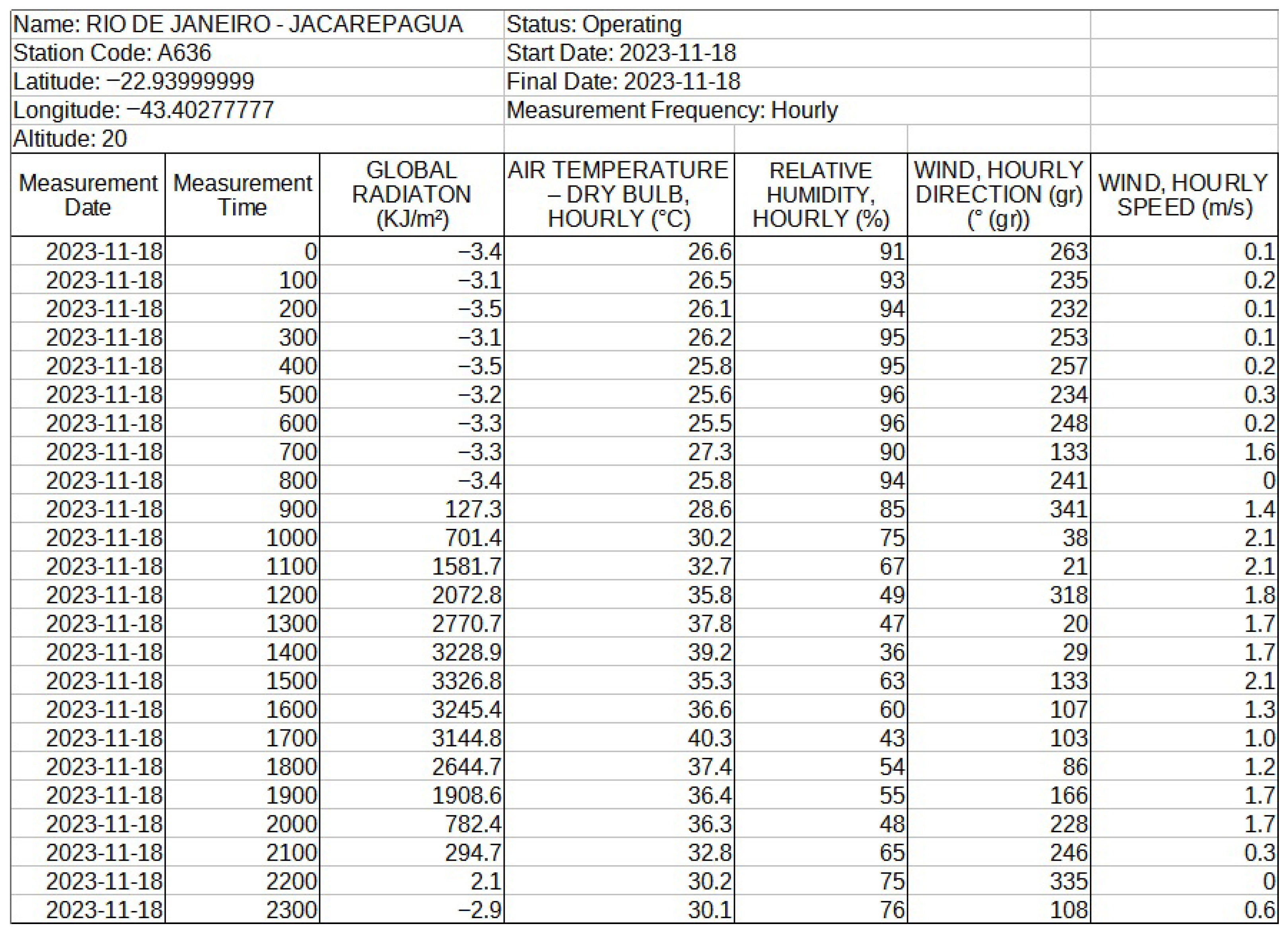

Table 5 presents the minimum and maximum values for the summer day used in the ENVI-met simulation (18 November 2023), including air temperature (Ta), mean radiant temperature (MRT), surface temperature (Ts), wind speed (V), and relative humidity (RH).

Table 6 shows the calculated PET, PMV, and UTCI values.

It can be observed that the region experiences significant thermal stress even during periods with lower air temperatures, due to very high solar radiation (MRT > Ta), which indicates moderate to strong heat discomfort. Furthermore, the thermal stress intensifies during the afternoon hours.

4. Discussion

4.1. Simulation Results

This study aimed to analyze part of the Rio das Pedras favela across three distinct periods (2013, 2019, and 2024), using digital surface models and microclimatic simulations to investigate urban morphological changes in Rio das Pedras, with a focus on its verticalization. The goal was to assess the occurrence of microclimatic alterations and identify which elements might influence the local air temperature. The results clearly indicate the intense construction dynamics in Rio das Pedras in recent years, as demonstrated by the increase in the number of floors in hundreds of buildings and by the rise in the average building height across the different periods.

The region experiences significant thermal stress, which lingers during the afternoon hours, as evidenced by indices such as PET, PMV, and UTCI. The significant thermal discomfort recorded during the early morning, driven by high mean radiant temperatures, highlights the dominant role of solar radiation and stored heat in the urban fabric.

Following the simulations, it was found that there were no drastic changes in the distribution of the heat island across the three periods, mostly due to the fact that the slum was already heavily populated in 2013. However, persistently high air temperatures were observed at midnight, several hours after sunset. The limited nighttime cooling can be attributed to the materials used in building construction and ground cover. This scenario, characterized by poor heat dissipation and limited airflow, reinforces the formation of urban heat islands, resulting in higher energy consumption due to the continuous use of air conditioning. It was also found that the riverbank showed considerably lower potential air temperatures, which can be explained by the formation of a wider corridor but should also be taken with care, as further explained in the next section.

The Delfim abandoned buildings present somewhat high potential air temperatures despite not being located in a densely populated area. This can be explained by two key factors: their structural characteristics and their immediate environment. The abandoned concrete skeleton structures retain and redistribute stored heat, a phenomenon intensified by their height. Furthermore, the building layout hinders wind circulation, which reduces heat dissipation and results in elevated air temperatures that persist even at night. Compounding this effect is the nature of the surrounding vegetation, which is composed mostly of grass and features large pockets of exposed rock and sand. This landscape provides little mitigation against solar gain and contributes to the overall heat accumulation in the area.

Another important trend is the steady rise in potential air temperature over the 11-year period. Although minimal, this increase is significant considering that global warming of 1.5 °C above pre-industrial levels occurred over two centuries [

57]. An increase of a few tenths of a degree Celsius over eleven years is therefore an alarming finding.

Finally, the reliance on simulation in this study necessitates a discussion of its empirical validation, while in situ measurements remain the essential standard for verifying microclimatic models [

13], they are often unfeasible in dense, informal settlements due to significant security risks and complex topography that hinder extensive field campaigns. This simulation-based approach therefore presents a distinct set of limitations and advantages. Its primary limitation is that it does not directly utilize a network of local in situ measurements; instead, it models the spatial distribution of air temperature based on an ensemble of topographic features, simulated materials and data from a meteorological station, among other variables. However, this very limitation reveals its core advantage: the methodology provides a viable and valuable alternative for estimating temperature variations with a reasonable degree of accuracy [

55] in areas that are otherwise inaccessible, enabling critical research in logistically challenging environments.

4.2. Adaptability of the Methodology Employed

ENVI-met has demonstrated considerable effectiveness as a predictive tool [

46,

58,

59]. However, it is important to note that the model is not entirely grid-independent, and its calculations may be less accurate in certain scenarios—such as assessing rooftop-level mitigation strategies [

55]. Despite these limitations, its findings remain reliable when applied at the urban street level, where it consistently reveals a clear correlation between high-density vertical development and localized air temperature increases.

Also, it is worth noting that although ENVI-met is suitable for tropical regions, it uses European parameters where water bodies have a significant cooling effect. ENVI-met models water based on the characteristics of temperate climates, where it exhibits a more pronounced cooling effect [

60]. In tropical regions; however, water bodies can potentially form heat islands due to high evaporation rates. Nevertheless, ENVI-met’s overall performance is appropriate for most urban studies [

55].

Furthermore, there is also a need to refine the models and microclimatic simulations by incorporating features not included in this study, such as hourly simulations, point vectors for trees and pollution sources, and optional software modules, to determine whether more accurate results can be achieved.

It is also important to acknowledge the simplifications inherent in the simulation. A primary limitation was the homogenization of building materials, where all façades were modeled as brick and all roofs as light concrete, while these are common materials in favelas, the real-world environment features a diverse array of heat-retaining and radiating materials, many of which may have thermal properties different from the modeled ones. Consequently, while the simulation successfully replicated the urban morphology, such as the dense building arrangement and narrow alleyways that restrict ventilation, it could not fully capture the complex thermal dynamics introduced by material heterogeneity. Neither the simulation considered the presence of urban pollution, which can entrap heat even more intensely [

61] A further significant simplification was the exclusion of air conditioning systems. Their pervasive use of is known to reject waste heat, inadvertently intensifying the local heat island effect [

62] and contributing to a cycle of escalating energy consumption and ambient heat. The absence of this anthropogenic heat source in the model likely results in an underestimation of actual night-time temperatures.

A major consideration for interpreting these findings involves contextualizing the case of Rio das Pedras within the broader landscape of Rio’s favelas. Unlike the archetype of informal settlements sprawling across steep hillslopes, Rio das Pedras is situated on relatively flat terrain. This key morphometric difference means that future simulations in other poor communities must incorporate more varied and complex relief patterns to model airflow. Furthermore, the study area’s extreme built density resulted in a near-total absence of vegetation, a factor not representative of all informal settlements. There are favelas which contain pockets of trees and secondary growth, thus introducing additional variables such as shading and evapotranspiration into the microclimatic model. These specific characteristics—the flat topography and lack of greenery—do not invalidate the methodological framework developed here. Rather than that, they pose specific concerns that, while not fully addressed by this single case study, are essential for a comprehensive understanding of their microclimates.

Finally, this study relied on high-resolution data, including LiDAR, aerial imagery, and accurate building footprints, which were essential for developing a realistic microclimatic model. The success of such simulations is contingent upon the availability of precise spatial data, seasonal surveys, and local climatic information to perform the necessary iterations. Nevertheless, the methodological framework is adaptable. For other cities in the Global South facing similar challenges but lacking high-resolution data, collaborative initiatives offer a viable alternative. Participatory geospatial databases, such as OpenStreetMap for building footprints, and freely available global Digital Elevation Models (DEMs) can provide the fundamental spatial data required. When combined with long-term temperature records from local weather facilities, these resources make the reproduction of this study feasible, even if at a coarser resolution, while the model’s performance is optimal with high-accuracy inputs, the methodology itself can be successfully applied using open-source data, thereby enhancing its accessibility and potential for broader application.

4.3. Mitigation Strategies

While this article has aimed to develop methodologies for estimating microclimatic changes in dense, unregulated urban environments, it is equally critical to consider potential mitigation strategies. Such strategies are essential for enhancing urban comfort and supporting the sustainable reurbanization of deprived areas, moving beyond the simplistic and disruptive approach of displacing long-established populations. Urban configuration and building typology influence the microclimate, potentially creating or preventing heat islands [

5]. Consequently, urban form directly impacts local energy consumption, connected to population and building density. The proportion of open to built-up areas, vegetation presence, solar orientation of streets, building heights and setbacks, street dimensions, and construction materials all influence urban quality and activities like mobility and land use distribution [

63,

64]. Building typology significantly affects natural lighting and ventilation, contributing to rational electricity use. Buildings are major contributors to urban energy consumption, but well-designed typologies can reduce this impact through bioclimatic principles. From a bioclimatic perspective, compact cities in humid tropical regions promote heat island formation, raising electricity consumption, excessive air conditioning use, and pollution [

65]. Favelas often exhibit such problems due to high density and unplanned growth, intensified in areas with significant verticalization, as seen in Rio das Pedras.

The urban fabric of Rio das Pedras, characterized by its intense verticalization and dense layout, exemplifies the challenges endemic to informal settlements. Here, the combination of inadequate planning and high population density significantly intensifies microclimatic effects, creating a feedback loop that worsens thermal discomfort. As observed, localized air temperature increases were associated with areas of significant vertical expansion. This correlation suggests that continued vertical growth across the favela could catalyze the formation of new urban heat islands (UHIs), further degrading urban comfort. Consequently, effective mitigation strategies must prioritize curbing informal vertical expansion as a critical measure to prevent the emergence of new UHIs.

To mitigate these effects, urban planning strategies that can be adopted include the use of surfaces with reflective materials (high albedo) and increasing vegetation cover [

11,

66]. Urban vegetation shows great effectiveness in reducing air temperatures through processes of shading, evapotranspiration, and interception of solar radiation, potentially lowering local air temperature by up to 5 °C [

8]. Therefore, interventions such as the creation of green areas, improved natural ventilation, use of more suitable building materials, and implementation of urban policies that promote more sustainable and balanced development would be necessary [

3,

15,

60,

67,

68,

69,

70], with consistent indications that a combination of cool pavements and extra trees may yield a drop of a couple degrees Celsius [

19]. These measures could enhance not only the microclimate but also residents’ quality of life.

One intervention with immediate impact is the increase in urban vegetation (usually absent from slums, but very useful in reducing UHI effects in tropical climates) [

15], where intense solar radiation and high air humidity aggravate thermal discomfort [

71,

72]. The effectiveness of vegetation is maximized by using trees with dense canopies [

73] and a high Leaf Area Index (LAI), making it a viable solution to improve thermal comfort on a microscale. Complete shading of outdoor areas combined with evapotranspiration can reduce mean radiant temperature by up to 32 °C [

9]. Ref. [

74] found canopy density as a critical factor for the effectiveness of tree planting, as overlapping tree crowns create continuous shaded zones, lowering air temperature by up to 2.8 °C. Conversely, sparse arrangements contribute less, especially during times of peak solar radiation.

In addition to tree planting, other forms of vegetation, such as green roofs and green walls, also help mitigate heat stress [

60,

66,

69,

70]. Combining these strategies with tree planting has shown a significant reduction in temperature in Colombo, Sri Lanka, approaching 2 °C during peak hours [

8]. The benefits of tree planting are notable; however, for analyses and results that are more faithful to reality, it is essential to calibrate models with on-site data, ensuring the accuracy of ENVI-met simulations. This approach efficiently supports the development of urban solutions, in addition to incorporating parameters such as crown geometry and canopy leaf density in the tree models used [

11].

Other strategies can be employed to mitigate UHI effects, such as the use of high-albedo materials (cool roofs and pavements) [

66]. However, Ref. [

10] emphasize that such a strategy is less effective in tropical climates than in temperate ones. This is due to differences in urbanization between these locations, since tropical cities are often situated in developing countries, with fewer surfaces suitable for replacement with cool materials, resulting in smaller temperature reductions in simulations. Urban ventilation is also a strategy to be considered, as it helps dissipate heat. Tropical cities, especially inland ones, tend to have lower wind speeds, which may be further influenced by local urban morphology [

56]. The orientation of buildings and streets can improve airflow, but the low wind speeds typical of these regions limit its impact [

9].

4.4. Participatory Planning and Slum Interventions

Rethinking the favela requires dialog with its residents. In this regard, the City Statute, established by Federal Law No. 10257/2001, represents a fundamental legal milestone for promoting dignified conditions in favelas by establishing guidelines for sustainable urban development and the social function of property. Through instruments such as the Master Plan, land regularization, and democratic management, the Statute seeks to ensure the right to housing, basic sanitation, and access to quality urban infrastructure, especially in historically neglected areas [

75].

According to the Statute, urban policy aims to organize the full development of the social functions of the city and urban property by guaranteeing the right to sustainable cities—that is, the right to urban land, housing, environmental sanitation, urban infrastructure, transportation and public services, employment, and leisure for present and future generations—as well as democratic management through the participation of the population and representative associations of various community segments in the formulation, implementation, and monitoring of urban development plans, programs, and projects. However, the effective implementation of these guidelines still faces challenges, such as lack of resources and the need for greater popular participation.

The integration of Geographic Information Systems (GIS) with microclimate modeling presents a transformative opportunity for data-driven urban planning [

76]. This is critically needed in informal settlements, where traditional management strategies—such as large-scale evictions and standardized high-rise projects—often ignore socio-spatial dynamics and localized microclimates, exacerbating urban heat and displacing communities. Since any modification to the urban fabric can significantly alter microclimates and induce environmental discomfort, computational simulations are essential. They allow planners to evaluate changes proactively and select optimal interventions that promote thermal comfort and livability [

47,

64].

Based on such simulations, participatory GIS (PGIS) methodologies can enable precision interventions that balance upgrading efforts with community preservation. This is critically relevant in Rio das Pedras, where a severe urban heat island has already been identified, with additional hotspots likely if current urban patterns persist. These patterns are characterized by narrow alleyways, scarce vegetation, and the widespread use of heat-retentive materials like brick and concrete. Here, microclimate simulation tools combined with participatory mapping can empower community-led mitigation strategies—such as strategic vegetation planting, creating ventilation pathways, or selective building upgrades. This approach not only respects local socio-cultural networks but also enhances climatic resilience, offering a sustainable alternative to the demolition paradigm.

This integrated methodology is fundamentally aligned with the principles of environmental justice [

77], which advocates that all communities, regardless of socioeconomic status, have the right to a healthy environment. This framework recognizes that environmental harms, such as resource scarcity and ecosystem destabilization, disproportionately affect marginalized groups, reflecting deeper political and economic asymmetries [

78]. In favelas, this historical neglect manifests as a lack of infrastructure, extreme heat, and vulnerability to disasters [

79].

Therefore, advancing environmental justice in these contexts requires policies that actively address these socio-environmental inequities, providing social cohesion and climate resilience [

80]. It means securing basic rights like clean air, safe housing, and green spaces [

69,

70], while ensuring community participation in decision-making. In this pursuit, microclimate modeling and selective urban planning are key. By objectively identifying high-heat zones and optimizing green space distribution, these data-driven tools help prioritize interventions where they are needed most. This turns the principle of environmental justice into tangible action, guiding low-impact upgrades that improve livability and resilience without displacing the very communities they are designed to serve.

4.5. Summary of Possible Future Interventions

As a final summary,

Table 7 lists the main mitigation strategies discussed herein. It also incorporates planning strategies previously discussed.

5. Conclusions

The findings of this study highlight the profound microclimatic consequences of unregulated vertical growth in Rio das Pedras, where rapid urbanization has intensified the urban heat island effect and worsened thermal discomfort for residents. The persistent high air temperatures, even after sunset, underscore the compounding effects of dense construction, heat-retentive materials, and restricted airflow: a scenario common in many informal settlements.

Microclimatic simulations revealed a rise up greater than 0.4 °C in a decade. between 2013 and 2024. This, coupled with the persistence of heat islands signals a critical threshold: the favela’s existing density had already locked in adverse thermal conditions. Consequently, any further vertical expansion is likely to intensify heat, particularly in the favela’s currently cooler areas where buildings are lower. The study further emphasizes the limitations of current modeling, underscoring the need to integrate more granular data—such as localized vegetation and pollution variables—to refine predictive accuracy.

The research underscores the urgency of rethinking urban upgrading strategies in favelas, moving beyond top-down redevelopment toward participatory, climate-sensitive solutions. Brazil provides a legal framework, through its City Statute, for such an approach, advocating for sustainable urban policies that prioritize resident well-being and environmental justice. However, translating these principles into action demands innovative tools like participatory GIS and microclimate modeling, which can identify localized heat mitigation strategies—such as strategic greening or improved ventilation—while preserving community cohesion.

Effective improvement of livability in poor Global South settlements requires proper participatory planning, through which local governments can implement a balanced mix of policies. Microclimatic simulations help identify areas where UHIs are most severe, guiding targeted urban interventions. When these strategies are combined with simulation technologies, urban spaces can be transformed into more resilient and habitable environments. Such investments not only enhance public health and reduce energy consumption, but also strengthen long-term sustainability. Ultimately, only through integrated efforts can cities break the cycle of climatic and social vulnerability in informal settlements, fostering cooler neighborhoods and more equitable futures.