Availability and Adequacy of Facilities in 15 Minute Community Life Circle Located in Old and New Communities

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Literature Review

2.2. Methodology

2.2.1. Study Area

2.2.2. Data Collection

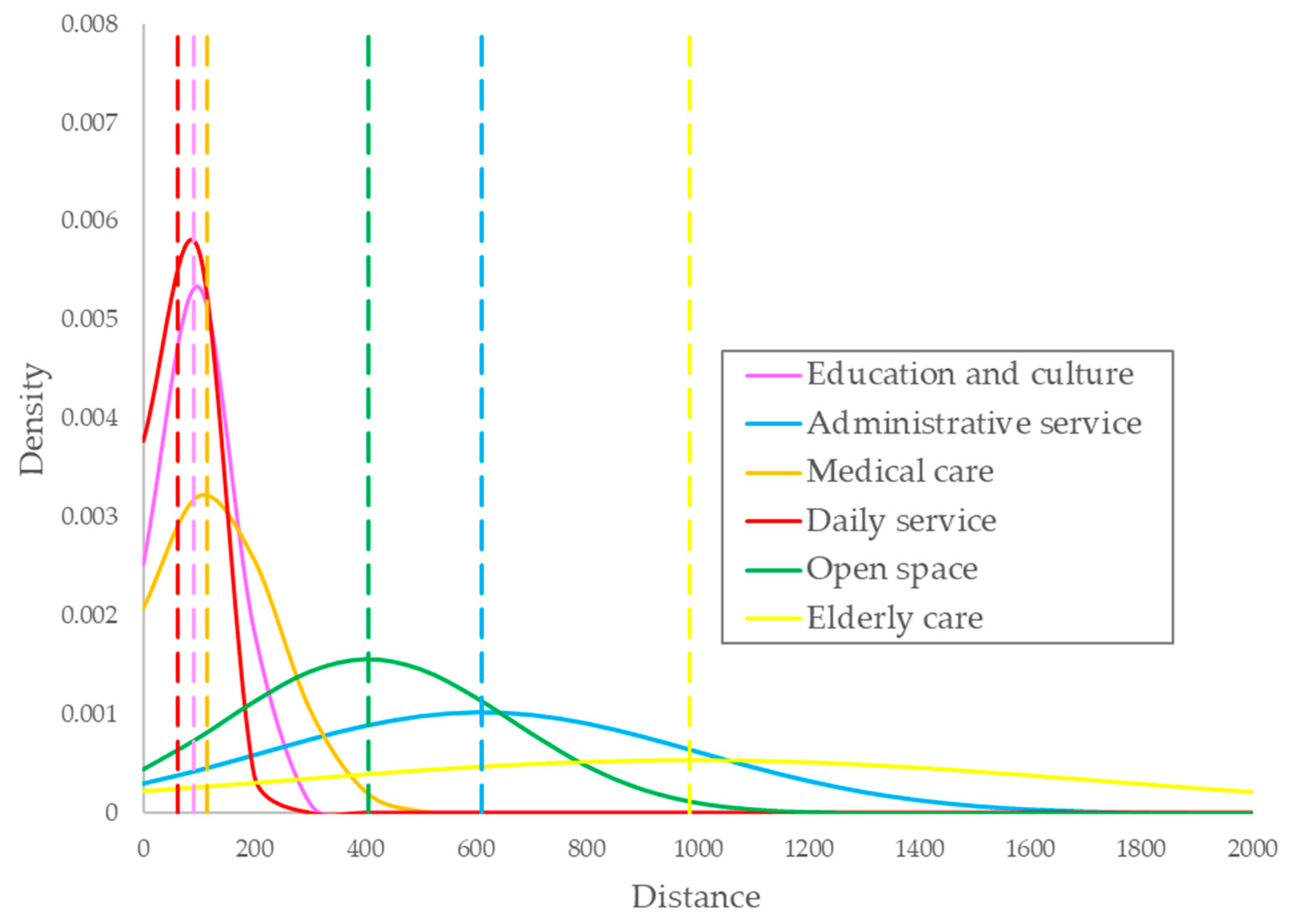

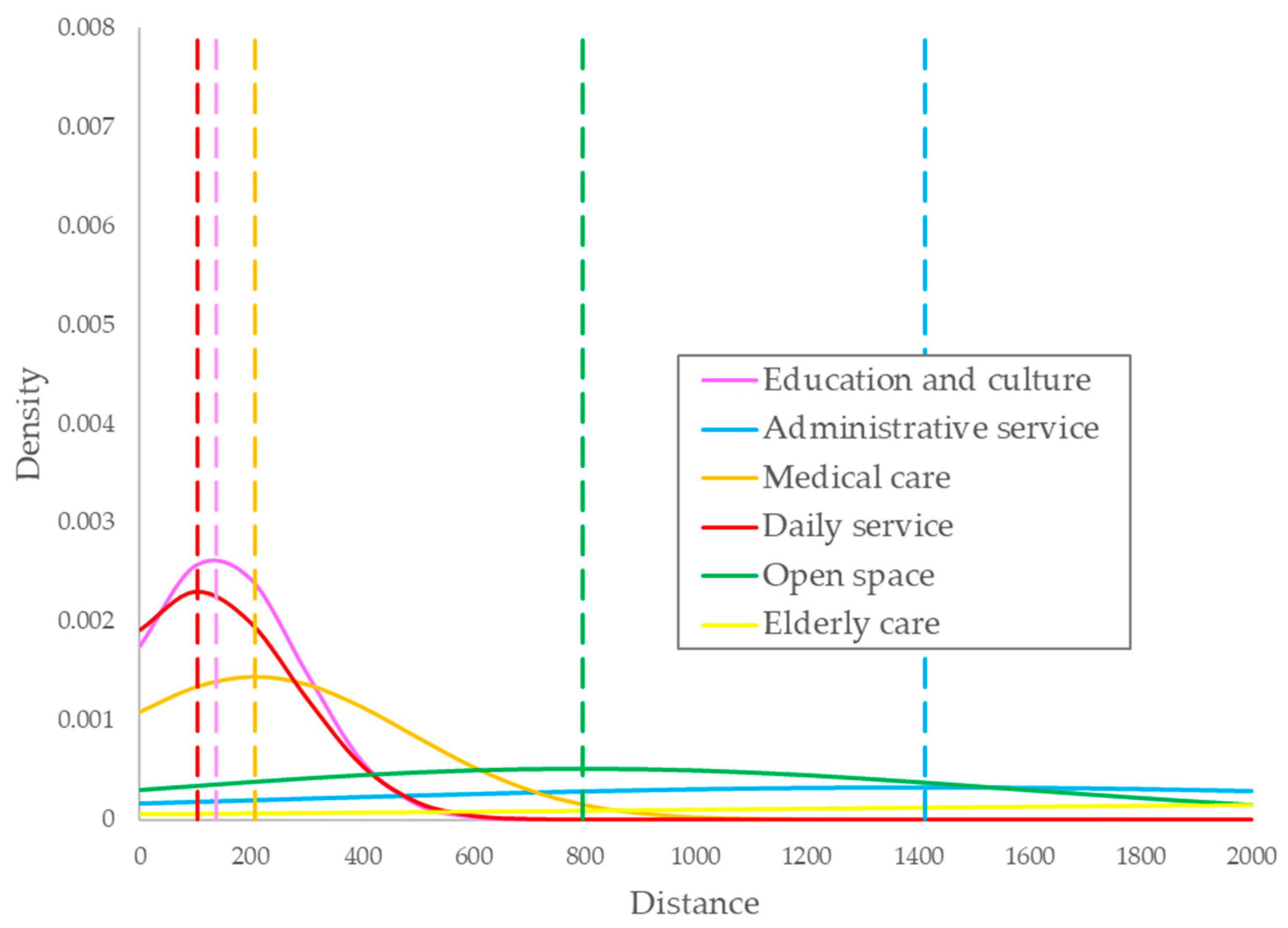

2.2.3. Analysis of Facilities Distribution in the Old and New Communities

2.2.4. Evaluation of Facilities Distribution in Each 15 min-CLC

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. The Distribution of Various Facilities in the Old and New Communities

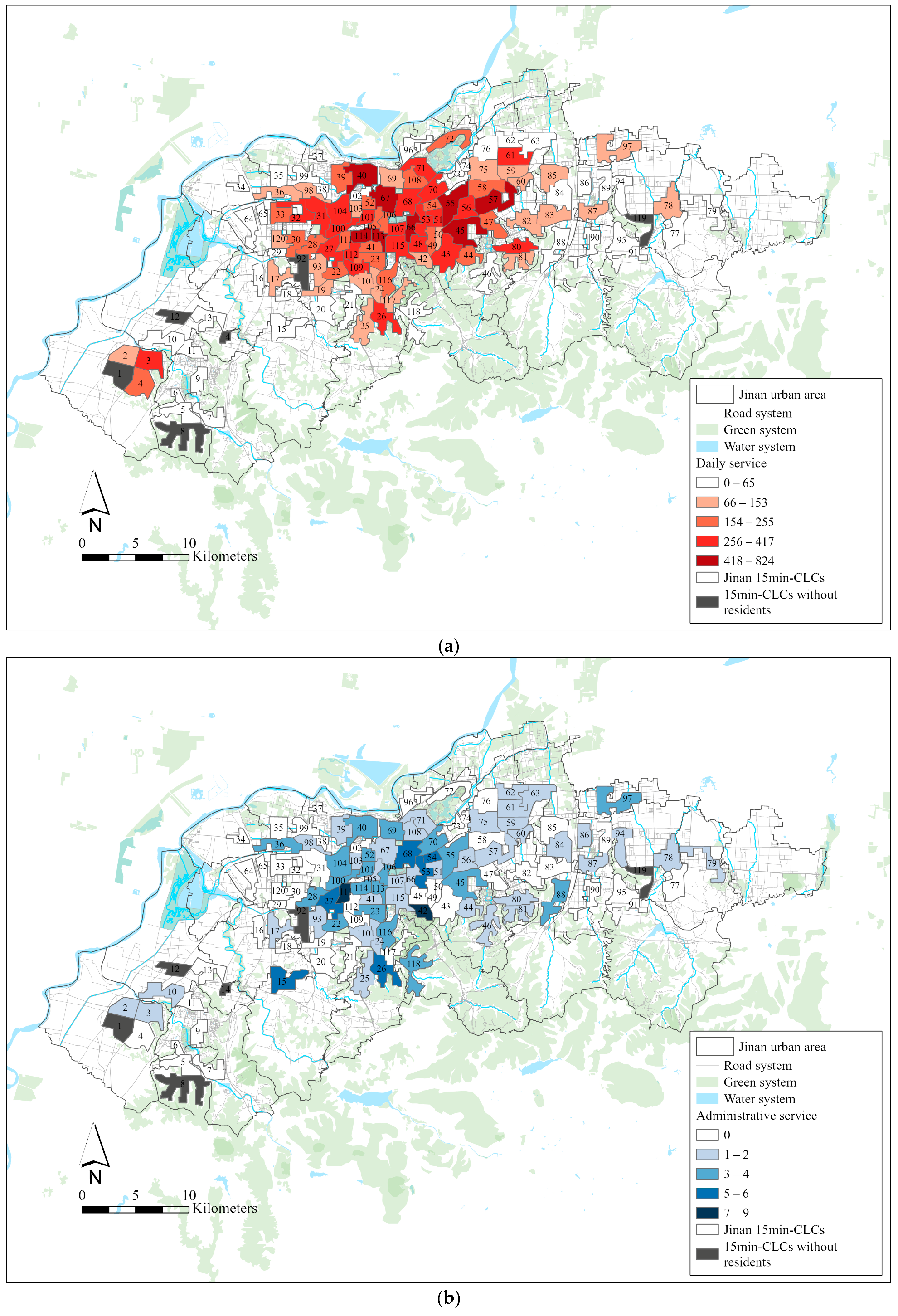

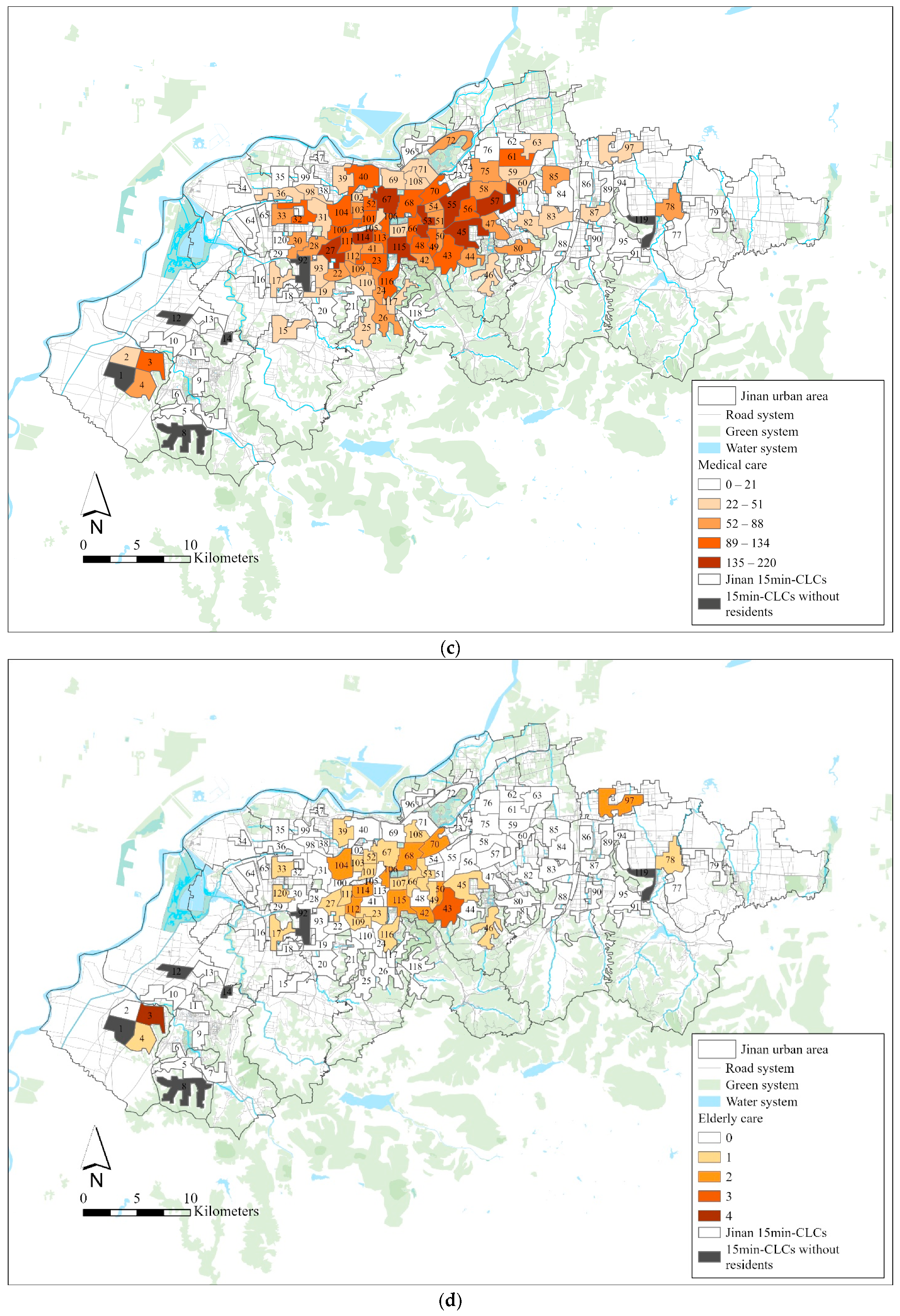

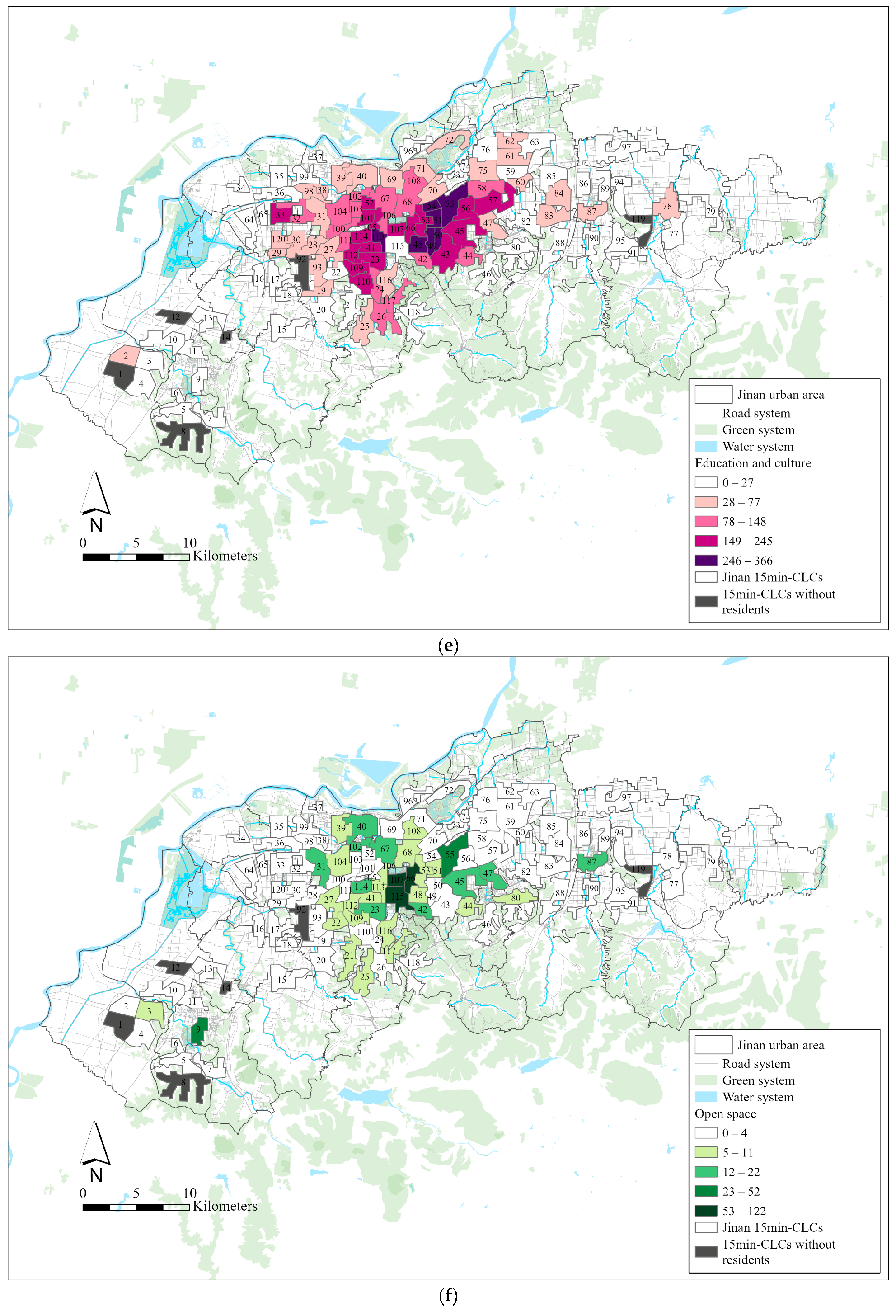

3.2. The Distribution of Facilities in the Each 15 min-CLC

3.3. The Selection of the Underdeveloped 15 min-CLCs

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dameri, R.P. Searching for smart city definition: A comprehensive proposal. Int. J. Comput. Technol. 2013, 11, 2544–2551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tobler, W.R. A computer movie simulating urban growth in the Detroit region. Econ. Geogr. 1970, 46 (Suppl. S1), 234–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulloa-Leon, F.; Correa-Parra, J.; Vergara-Perucich, F.; Cancino-Contreras, F.; Aguirre-Nuñez, C. “15-Minute City” and Elderly People: Thinking about Healthy Cities. Smart Cities 2023, 6, 1043–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, M.; Ding, N.; Li, J.; Jin, X.; Xiao, H.; He, Z.; Su, S. The 15-minute walkable neighborhoods: Measurement, social inequalities and implications for building healthy communities in urban China. J. Transp. Health 2019, 13, 259–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno, C.; Allam, Z.; Chabaud, D.; Gall, C.; Pratlong, F. Introducing the “15-Minute City”: Sustainability, resilience and place identity in future post-pandemic cities. Smart Cities 2021, 4, 93–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pozoukidou, G.; Angelidou, M. Urban planning in the 15-minute city: Revisited under sustainable and smart city developments until 2030. Smart Cities 2022, 5, 1356–1375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanghai Urban Planning and Land Resources Administration. Shanghai Planning Guidance of 15-Minute Community-life Circle, 2016. Available online: https://hd.ghzyj.sh.gov.cn/zcfg/ghss/201609/P020160902620858362165.pdf (accessed on 27 September 2022).

- Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development of China: Standard for the Planning and Design of Urban Residential Areas, 2018. Available online: https://www.mohurd.gov.cn/?medium=01 (accessed on 10 October 2022).

- Guo, X.; Deng, M.; Wang, X.; Yang, X. Population agglomeration in Chinese cities: Is it benefit or damage for the quality of economic development? Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chivakul, M.; Lam, M.W.W.; Liu, X.; Maliszewski, W.; Schipke, M.A. Understanding Residential Real Estate in China; International Monetary Fund: Washington, DC, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Liu, Y.; Chen, Y.; Long, H. The process and driving forces of rural hollowing in China under rapid urbanization. J. Geogr. Sci. 2010, 20, 876–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, W.; Wang, B.; Tian, L.; Niu, X. Spatial deprivation of urban public services in migrant enclaves under the context of a rapidly urbanizing China: An evaluation based on suburban Shanghai. Cities 2017, 60, 436–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Zheng, J.; Zhang, Y. Study on the Layout of 15-Minute Community-Life Circle in Third-Tier Cities Based on POI: Baoding City of Hebei Province. Engineering 2019, 11, 592–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, L.; Liu, Y. Life circle construction in China under the idea of collaborative governance: A comparative study of Beijing, Shanghai and Guangzhou. Geogr. Rev. Jpn. Ser. B 2017, 90, 2–16. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, X.; Gong, P.; White, M.; Zhang, B. Research on Spatial Distribution Characteristics and Influencing Factors of Pension Resources in Shanghai Community-Life Circle. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2022, 11, 518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.R.; Hui, E.C.M.; Sun, J.X. Population migration, urbanization and housing prices: Evidence from the cities in China. Habitat Int. 2017, 66, 49–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Li, L.; Hui, E.C.M.; Li, V. Comparisons of the relations between housing prices and the macroeconomy in China’s first-, second-and third-tier cities. Habitat Int. 2016, 57, 24–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- C40 Cities Climate Leadership Group, C40 Knowledge Hub. 15-Minute Cities: How to Create Connected Places. Available online: https://www.c40knowledgehub.org/s/article/15-minute-cities-How-to-create-connected-places?language=en_US (accessed on 22 October 2022).

- C40 Cities Climate Leadership Group, C40 Knowledge Hub. 15-Minute Cities: How to Ensure a Place for Everyone. Available online: https://www.c40knowledgehub.org/s/article/15-minute-cities-How-to-ensure-a-place-for-everyone?language=en_US (accessed on 22 October 2022).

- C40 Cities Climate Leadership Group, C40 Knowledge Hub. 15-Minute Cities: How to Create ‘Complete’ Neighbourhoods. Available online: https://www.c40knowledgehub.org/s/article/15-minute-cities-How-to-create-complete-neighbourhoods?language=en_US (accessed on 22 October 2022).

- Calafiore, A.; Dunning, R.; Nurse, A.; Singleton, A. The 20-minute city: An equity analysis of Liverpool City Region. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2022, 102, 103111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, G.; Thornton, L.E.; Daniel, M.; Chaix, B.; Lamb, K.E. Comparison of spatial approaches to assess the effect of residing in a 20-minute neighbourhood on body mass index. Spat. Spatio-Temporal Epidemiol. 2022, 43, 100546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gower, A.; Grodach, C. Planning Innovation or City Branding? Exploring How Cities Operationalise the 20-Minute Neighbourhood Concept. Urban Policy Res. 2022, 40, 36–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- City of Portland Bureau of Planning and Sustainability: Twenty-minute Neighborhoods, 2009. Available online: https://www.portland.gov/bps/planning/about-bps/portland-plan (accessed on 7 October 2022).

- TCPA. 20-Minute Neighbourhoods; Town Country Planning Association: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Capasso Da Silva, D.; King, D.A.; Lemar, S. Accessibility in practice: 20-minute city as a sustainability planning goal. Sustainability 2019, 12, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Logan, T.M.; Hobbs, M.H.; Conrow, L.C.; Reid, N.L.; Young, R.A.; Anderson, M.J. The x-minute city: Measuring the 10, 15, 20-minute city and an evaluation of its use for sustainable urban design. Cities 2022, 131, 103924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graells-Garrido, E.; Serra-Burriel, F.; Rowe, F.; Cucchietti, F.M.; Reyes, P. A city of cities: Measuring how 15-minutes urban accessibility shapes human mobility in Barcelona. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0250080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noworól, A.; Kopyciński, P.; Hałat, P.; Salamon, J.; Hołuj, A. The 15-Minute City—The Geographical Proximity of Services in Krakow. Sustainability 2022, 14, 7103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, G.; He, X.; Kong, Y.; Li, K.; Song, H.; Zhai, S.; Luo, J. Improving the Spatial Accessibility of Community-Level Healthcare Service toward the ‘15-Minute City’ Goal in China. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2022, 11, 436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Wang, L.; Zhang, Z.; Gao, J. Analysis and optimization of 15-minute community life circle based on supply and demand matching: A case study of Shanghai. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0256904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Bureau of Statistics of China: The Seventh National Census. Available online: http://www.stats.gov.cn/tjsj/ndsj/2021/indexeh.htm (accessed on 6 October 2022).

- Jinan City Planning Bureau Issued the Guideline: Jinan Planning Guidance of 15-minute Community. Available online: http://nrp.jinan.gov.cn/art/2019/1/31/art_43831_3510151.html (accessed on 6 October 2022).

- The History of the People’s Republic of China. Available online: http://www.hprc.org.cn/gsyj/shs/shxss/201912/t20191230_5066854.html (accessed on 10 August 2023).

- Hamama, B.; Liu, J. What is beyond the edges? Gated communities and their role in China’s desire for harmonious cities. City Territ. Archit. 2020, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, W.; Chen, T.; Li, X. A new style of urbanization in China: Transformation of urban rural communities. Habitat Int. 2016, 55, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Wu, Z. The characteristics of leisure activities and the built environment influences in large-scale social housing communities in China: The case study of Shanghai and Nanjing. J. Asian Archit. Build. Eng. 2022, 21, 825–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, B.; Li, Y.; Wang, J. The improvement strategy on the management status of the old residence community in Chinese cities: An empirical research based on social cognitive perspective. Cogn. Syst. Res. 2018, 52, 556–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Han, Y. Identification of urban functional areas based on POI Data: A case study of the guangzhou economic and technological development zone. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Li, S.; Kong, F. Association between sense of belonging and loneliness among the migrant elderly following children in Jinan, Shandong Province, China: The moderating effect of migration pattern. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 4396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, J.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, K.; Ma, C.; Sun, H.; Wang, Z.; Wu, H.; Li, M.; Zhang, L.; Tang, X.; et al. Healthy Community-Life Circle Planning Combining Objective Measurement and Subjective Evaluation: Theoretical and Empirical Research. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 5028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, T.; Lü, G.; Zhong, X.; Tang, H.; Ye, Y. Measuring human-scale living convenience through multi-sourced urban data and a geodesign approach: Buildings as analytical units. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q. The Urban Expansion Model. In China’s Development Under a Differential Urbanization Model. Research Series on the Chinese Dream and China’s Development Path; Springer: Singapore, 2020; pp. 219–241. [Google Scholar]

- Logan, T.M.; Anderson, M.J.; Williams, T.G.; Conrow, L. Measuring inequalities in urban systems: An approach for evaluating the distribution of amenities and burdens. Comput. Environ. Urban Syst. 2021, 86, 101590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, M.; Li, J.; Lv, Y.; Xing, H.; Wang, H. Functional Area Recognition and Use-Intensity Analysis Based on Multi-Source Data: A Case Study of Jinan, China. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2021, 10, 640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handy, S.L.; Clifton, K. Evaluating Neighborhood Accessibility: Issues and Methods Using Geographic Information Systems; Performing Organization Code Unclassified; University of Texas: Austin, TX, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- National Bureau of Statistics of China. Available online: http://www.stats.gov.cn/xxgk/jd/zcjd/202109/t20210930_1822661.html (accessed on 12 August 2023).

| Data Types | Measurements | Sources | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Facility Categories | Daily service (C1) | Counting the number of POIs of food markets, maintenance shops, express delivery stations, supermarkets, banks, ATMs, convenience stores, public toilets. | The website of Baidu Map. https://lbs.baidu.com/index.php?title=webapi/guide/webservice-placeapi (accessed on 28 September 2022) |

| Administrative service (C2) | Counting the number of POIs of police stations, community service centers, subdistrict offices. | ||

| Medical care (C3) | Counting the number of POIs of hospitals, clinics. | ||

| Elderly care (C4) | Counting the number of POIs of elderly care facilities. | ||

| Education and culture (C5) | Counting the number of POIs of cultural and educational facilities, fitness services. | ||

| Open space (C6) | Counting the number of POIs of parks. | ||

| Population | China population census yearbook. | The website of 15. National Bureau of Statistics of China. http://www.stats.gov.cn/tjsj/ndsj/2021/indexeh.htm (accessed on 6 October 2022) | |

| Areas | Daily Service (C1) | Administrative Service (C2) | Medical Care (C3) | Elderly Care (C4) | Education and Culture (C5) | Open Space (C6) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5 | 1.411 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| 13 | 0.434 | 0.000 | 0.193 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| 36 | 6.591 | 0.361 | 2.167 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| 20 | 5.724 | 0.000 | 2.289 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| 77 | 0.028 | 0.000 | 0.028 | 0.000 | 0.057 | 0.000 |

| 94 | 1.170 | 0.130 | 0.260 | 0.000 | 0.130 | 0.000 |

| 37 | 6.690 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.291 | 0.000 |

| 76 | 10.954 | 0.000 | 1.730 | 0.000 | 0.577 | 0.000 |

| 91 | 0.331 | 0.000 | 0.166 | 0.000 | 0.580 | 0.000 |

| 6 | 0.437 | 0.000 | 0.087 | 0.000 | 0.700 | 0.000 |

| 96 | 8.117 | 0.000 | 0.406 | 0.000 | 0.812 | 0.000 |

| 65 | 0.513 | 0.000 | 0.342 | 0.000 | 0.855 | 0.000 |

| 16 | 0.723 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.964 | 0.000 |

| 79 | 1.249 | 0.059 | 0.416 | 0.000 | 1.011 | 0.000 |

| 63 | 6.903 | 0.128 | 3.579 | 0.000 | 1.023 | 0.000 |

| 35 | 6.901 | 0.000 | 2.588 | 0.000 | 1.078 | 0.000 |

| 11 | 2.851 | 0.000 | 0.143 | 0.000 | 1.497 | 0.000 |

| 97 | 40.302 | 0.923 | 13.844 | 0.615 | 1.538 | 0.000 |

| 28 | 10.721 | 0.133 | 3.737 | 0.000 | 2.491 | 0.000 |

| 86 | 11.044 | 0.221 | 3.534 | 0.000 | 4.638 | 0.000 |

| 19 | 9.854 | 0.000 | 3.890 | 0.000 | 4.797 | 0.000 |

| 120 | 12.069 | 0.000 | 2.364 | 0.124 | 6.595 | 0.000 |

| 89 | 55.309 | 0.000 | 4.707 | 0.000 | 7.061 | 0.000 |

| 62 | 11.389 | 1.752 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 56.944 | 0.000 |

| 54 | 35.062 | 0.859 | 10.141 | 0.000 | 62.906 | 0.000 |

| 58 | 1.999 | 0.000 | 0.629 | 0.000 | 0.835 | 0.019 |

| 46 | 1.155 | 0.023 | 0.531 | 0.023 | 0.624 | 0.023 |

| 50 | 3.381 | 0.000 | 1.630 | 0.048 | 6.665 | 0.024 |

| 49 | 6.850 | 0.000 | 2.691 | 0.027 | 7.421 | 0.027 |

| 17 | 1.830 | 0.031 | 0.729 | 0.016 | 0.078 | 0.047 |

| 110 | 1.847 | 0.016 | 0.714 | 0.000 | 3.119 | 0.047 |

| 72 | 5.910 | 0.000 | 2.010 | 0.000 | 1.235 | 0.048 |

| 85 | 1.769 | 0.000 | 0.893 | 0.000 | 0.331 | 0.050 |

| 43 | 4.692 | 0.000 | 1.460 | 0.043 | 2.693 | 0.057 |

| 56 | 7.999 | 0.043 | 2.645 | 0.000 | 3.806 | 0.065 |

| 93 | 1.866 | 0.035 | 0.708 | 0.000 | 0.622 | 0.069 |

| 88 | 2.235 | 0.210 | 0.699 | 0.000 | 0.279 | 0.070 |

| 104 | 3.537 | 0.041 | 1.029 | 0.020 | 1.121 | 0.071 |

| 7 | 0.441 | 0.000 | 0.331 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.074 |

| 100 | 8.270 | 0.098 | 2.535 | 0.000 | 3.643 | 0.074 |

| 105 | 4.117 | 0.025 | 0.864 | 0.000 | 4.473 | 0.076 |

| 70 | 5.889 | 0.058 | 2.184 | 0.039 | 1.033 | 0.078 |

| 68 | 2.465 | 0.045 | 0.965 | 0.018 | 0.741 | 0.080 |

| 15 | 2.597 | 0.269 | 1.120 | 0.000 | 0.716 | 0.090 |

| 53 | 6.367 | 0.092 | 2.718 | 0.015 | 3.741 | 0.092 |

| 41 | 3.653 | 0.015 | 1.345 | 0.000 | 2.934 | 0.092 |

| 116 | 2.613 | 0.041 | 1.086 | 0.010 | 0.318 | 0.092 |

| 22 | 3.379 | 0.059 | 1.284 | 0.000 | 0.375 | 0.099 |

| 4 | 5.213 | 0.000 | 1.497 | 0.028 | 0.028 | 0.111 |

| 111 | 7.146 | 0.337 | 4.415 | 0.037 | 4.939 | 0.112 |

| 10 | 0.988 | 0.038 | 0.380 | 0.000 | 0.076 | 0.114 |

| 61 | 10.711 | 0.077 | 4.816 | 0.000 | 1.657 | 0.116 |

| 83 | 5.094 | 0.000 | 1.932 | 0.000 | 3.630 | 0.117 |

| 38 | 6.106 | 0.000 | 1.869 | 0.000 | 6.106 | 0.125 |

| 52 | 12.906 | 0.254 | 6.103 | 0.064 | 11.444 | 0.127 |

| 3 | 7.028 | 0.039 | 2.002 | 0.079 | 0.157 | 0.137 |

| 103 | 3.713 | 0.034 | 2.097 | 0.034 | 5.088 | 0.138 |

| 48 | 5.323 | 0.000 | 1.987 | 0.000 | 5.530 | 0.138 |

| 109 | 7.564 | 0.000 | 1.909 | 0.024 | 5.325 | 0.141 |

| 33 | 14.154 | 0.000 | 3.841 | 0.071 | 12.945 | 0.142 |

| 57 | 29.787 | 0.036 | 6.471 | 0.000 | 5.929 | 0.145 |

| 101 | 13.718 | 0.109 | 3.711 | 0.036 | 7.678 | 0.146 |

| 71 | 20.999 | 0.074 | 3.684 | 0.000 | 5.673 | 0.147 |

| 90 | 2.956 | 0.000 | 1.921 | 0.000 | 0.443 | 0.148 |

| 78 | 7.766 | 0.102 | 3.451 | 0.051 | 2.690 | 0.152 |

| 32 | 16.286 | 0.000 | 5.922 | 0.000 | 4.339 | 0.153 |

| 106 | 6.349 | 0.104 | 3.122 | 0.052 | 3.513 | 0.156 |

| 67 | 6.894 | 0.011 | 1.893 | 0.011 | 1.101 | 0.161 |

| 108 | 4.536 | 0.042 | 0.936 | 0.021 | 1.789 | 0.166 |

| 113 | 8.052 | 0.050 | 2.001 | 0.000 | 5.506 | 0.182 |

| 60 | 12.838 | 0.183 | 4.768 | 0.000 | 6.052 | 0.183 |

| 118 | 2.753 | 0.138 | 0.872 | 0.000 | 1.239 | 0.184 |

| 75 | 10.883 | 0.093 | 5.116 | 0.000 | 3.721 | 0.186 |

| 18 | 3.205 | 0.000 | 2.828 | 0.000 | 1.885 | 0.189 |

| 95 | 0.756 | 0.000 | 0.284 | 0.000 | 0.095 | 0.189 |

| 81 | 4.890 | 0.064 | 1.207 | 0.000 | 1.080 | 0.191 |

| 69 | 7.881 | 0.194 | 1.486 | 0.000 | 4.716 | 0.194 |

| 44 | 6.814 | 0.081 | 2.379 | 0.000 | 4.234 | 0.202 |

| 80 | 11.546 | 0.041 | 3.374 | 0.000 | 0.935 | 0.203 |

| 23 | 2.131 | 0.029 | 1.012 | 0.010 | 2.092 | 0.206 |

| 45 | 7.276 | 0.044 | 2.263 | 0.015 | 3.342 | 0.207 |

| 24 | 9.638 | 0.072 | 4.028 | 0.000 | 9.422 | 0.216 |

| 39 | 6.189 | 0.028 | 0.700 | 0.028 | 1.008 | 0.224 |

| 114 | 7.787 | 0.064 | 3.532 | 0.032 | 2.986 | 0.241 |

| 59 | 13.791 | 0.127 | 4.049 | 0.000 | 1.771 | 0.253 |

| 26 | 20.221 | 0.317 | 5.008 | 0.000 | 7.987 | 0.254 |

| 21 | 1.357 | 0.000 | 0.452 | 0.000 | 0.090 | 0.271 |

| 25 | 4.312 | 0.125 | 1.437 | 0.000 | 3.687 | 0.312 |

| 82 | 13.649 | 0.000 | 2.383 | 0.000 | 2.492 | 0.325 |

| 84 | 6.489 | 0.127 | 2.418 | 0.000 | 4.454 | 0.382 |

| 117 | 6.022 | 0.000 | 2.603 | 0.000 | 4.644 | 0.408 |

| 40 | 11.824 | 0.102 | 3.422 | 0.000 | 1.634 | 0.485 |

| 73 | 33.398 | 0.000 | 9.763 | 0.000 | 7.707 | 0.514 |

| 98 | 40.355 | 0.273 | 10.907 | 0.000 | 11.725 | 0.545 |

| 74 | 2.456 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 7.367 | 0.614 |

| 64 | 1.950 | 0.000 | 1.300 | 0.000 | 3.900 | 0.650 |

| 34 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.667 | 0.000 | 2.669 | 0.667 |

| 27 | 34.591 | 0.591 | 16.064 | 0.099 | 7.194 | 0.690 |

| 29 | 45.504 | 0.000 | 18.377 | 0.000 | 51.630 | 0.875 |

| 31 | 12.015 | 0.000 | 1.886 | 0.000 | 3.070 | 0.877 |

| 51 | 32.367 | 0.193 | 7.633 | 0.000 | 27.053 | 0.966 |

| 42 | 5.188 | 0.371 | 3.104 | 0.093 | 4.772 | 1.019 |

| 2 | 38.965 | 0.354 | 14.169 | 0.000 | 17.357 | 1.063 |

| 115 | 3.888 | 0.022 | 1.955 | 0.022 | 0.270 | 1.146 |

| 99 | 28.760 | 0.000 | 5.177 | 0.000 | 3.451 | 1.150 |

| 30 | 60.460 | 0.000 | 20.645 | 0.000 | 16.811 | 1.180 |

| 55 | 20.327 | 0.150 | 8.266 | 0.000 | 12.775 | 1.202 |

| 9 | 0.638 | 0.000 | 0.080 | 0.000 | 0.319 | 1.382 |

| 107 | 5.466 | 0.019 | 0.856 | 0.019 | 3.910 | 1.556 |

| 87 | 13.700 | 0.266 | 5.586 | 0.000 | 4.921 | 1.596 |

| 47 | 22.659 | 0.000 | 7.324 | 0.000 | 5.607 | 1.602 |

| 66 | 8.386 | 0.026 | 1.585 | 0.013 | 2.390 | 1.611 |

| 102 | 7.905 | 0.000 | 5.043 | 0.000 | 18.808 | 1.908 |

| 112 | 73.548 | 0.000 | 19.107 | 0.523 | 54.703 | 2.094 |

| Mean | 10.524 | 0.097 | 3.232 | 0.021 | 5.587 | 0.307 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wu, W.; Divigalpitiya, P. Availability and Adequacy of Facilities in 15 Minute Community Life Circle Located in Old and New Communities. Smart Cities 2023, 6, 2176-2195. https://doi.org/10.3390/smartcities6050100

Wu W, Divigalpitiya P. Availability and Adequacy of Facilities in 15 Minute Community Life Circle Located in Old and New Communities. Smart Cities. 2023; 6(5):2176-2195. https://doi.org/10.3390/smartcities6050100

Chicago/Turabian StyleWu, Wei, and Prasanna Divigalpitiya. 2023. "Availability and Adequacy of Facilities in 15 Minute Community Life Circle Located in Old and New Communities" Smart Cities 6, no. 5: 2176-2195. https://doi.org/10.3390/smartcities6050100

APA StyleWu, W., & Divigalpitiya, P. (2023). Availability and Adequacy of Facilities in 15 Minute Community Life Circle Located in Old and New Communities. Smart Cities, 6(5), 2176-2195. https://doi.org/10.3390/smartcities6050100