Abstract

The commitment to improve energy and environmental performance in public administration is essential for the development models geared towards lasting sustainability. The Public Administration (PA) in Italy, in particular, plays a key role to affirm models oriented towards energy and environmental sustainability, thanks to a wider and more innovative approach. The PA has a dual consumer/user role, public heritage, and decision maker/planner, in promoting energy efficiency at the local level, in the light of specific problems and peculiarities. For several decades, initiatives have been launched at various levels to improve energy and environmental performance in the public administration. The aim of this study is to outline, from a critical perspective, the state of the art policy makers in Italy about energy efficiency measures in public administration. There are, however, many cultural, value-related, financial, technological, institutional, and operational issues in the PA sector that limit investments in energy efficiency. It should be noted that if, on the one hand, the PA shows a lack of knowledge and is unwilling to adopt practices and systemic tools for monitoring and control, and on the other, in terms of bureaucracy, the system appears to be far too complicated and costly. The multiple benefits linked to improved energy performance would therefore require that the PA rethink their organizational and functional models, put in place more flexible and less bureaucratic forms of management and a more dynamic, pervasive, and proactive approach towards initiatives that promote energy efficiency. The research is a contribution towards identifying the driving forces behind potential systems and tools for energy efficiency in the PA, highlighting both critical elements and opportunities, and in particular, the limits deriving from the technological, managerial, and organizational options available for energy efficiency enhancement in the sector of the Italian PA.

1. Introduction

The commitment to the search for an improvement of the energy performance, and therefore, the environment in PA represents a crucial step for the affirmation of the development models marked by a lasting sustainability.

In this scenario, the PA is called to assume a leading role in virtue of the changes that have characterized, in time and space, the community of reference and that which would have required the PA to adopt innovative ways of government, according to the logic of governance. A shared government, based on the interaction between state, market, and civil society to improve the effectiveness of public policies and to meet the requirements of complexity, differentiation, and dynamism resulting from the socio-economic system [1].

The PA, in its various articulations, in fact, covers the dual role of consumer/user, in an optical privatistic nature, within the framework of activities related to the management of public assets and of the maker/planner, for the promotion of energy efficiency in the territory, in the light of the knowledge of the related problems and peculiarities. For these reasons, through an enlarged and innovative vision, it is being asked to define and promote policies and actions for the improvement of energy efficiency.

For several decades, a set of initiatives have been undertaken at various levels to improve the energy and environmental performance of the public administration, shifting paradigms from the current socio-economic perspective, to review them from the “sustainable” development point of view.

For about thirty years, the debate on the sustainability of the planet has begun. In particular, already in June 1992, at the Earth Summit in Rio de Janeiro, more than 178 countries adopted Agenda 21, a comprehensive plan of action to build a global partnership for sustainable development to improve protect the environment. Then, the Johannesburg Declaration on Sustainable Development and the Plan of Implementation, adopted at the World Summit on Sustainable Development in South Africa in 2002, re-affirmed the global community’s commitments the sustainable development, and built on Agenda 21. At the United Nations Conference on Sustainable Development (Rio+20) in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, in June 2012, Member States adopted the outcome document “The Future We Want” in which they decided, inter alia, to launch a process to develop a set of SDGs to build upon the MDGs and to establish the UN High-level Political Forum on Sustainable Development. The Rio+20 outcome also contained other measures for implementing sustainable development, including mandates for future programs of work in development financing, small island developing states, and more. In 2013, the General Assembly set up a 30-member Open Working Group to develop a proposal on the SDGs. In January 2015, the General Assembly began the negotiation process on the post-2015 development agenda. The process culminated in the subsequent adoption of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, with 17 SDGs at its core, at the UN Sustainable Development Summit in September 2015. This last year was a landmark year for multilateralism and international policy shaping, with the adoption of several major agreements. The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, adopted by all United Nations Member States in 2015, provides a shared blueprint for peace and prosperity for people and the planet, now and into the future. At its heart are the 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), which are an urgent call for action by all countries—developed and developing—in a global partnership. They recognize that ending poverty and other deprivations must go hand-in-hand with strategies that improve health and education, reduce inequality, and improve economic growth—all while tackling climate change and working to preserve our oceans and forests. A contribution to the achievement of the objectives, in particular to sustainable cities and communities, could be given by the increase of the energy efficiency in profit and no profit organizations [2].

Since the United Nations Conference on Environment and Development, useful operational tools have been introduced and used by local authorities in order to ensure effective and efficient land management, based on the fundamental concept of “accountability”. Accountability is concerned not only with reporting non-financial performance, but also a set of promotional and information activities, through transparent decision-making processes [3].

Among the main initiatives adopted by the PA, there are the Environmental Accounting and Reporting Project for cities and local communities, better known as the CLEAR Project (City and Local Environmental Accounting and Reporting) and the LAKS (Local Accountability for Kyoto goalS) project. The first is based on a set of experiences and skills that look to the real needs and needs of the community, providing for the drafting and approval of “green public budgets” by local authorities of our country who participated in the project with the objective of retraining the process of local governance. The second, funded by the European Commission, focuses on two key themes for the promotion of local sustainability policy: Climate change and accountability.

In practice, the two projects—CLEAR and LAKS—are integrated, as the environmental balance and the “climate accountability” system allow the local authority to converge the policies of energy efficiency and energy and environmental sustainability with those based on transparency and reporting, to measure the results achieved, and to protect the collective interest.

In January 2008, the European Commission promoted the Covenant of Mayors as a voluntary initiative, aimed at involving European cities in the path towards energy and environmental sustainability, through the planning and implementation of measures and actions able to improve energy efficiency, increase the use of renewable sources, stimulate energy savings, and the rational use of energy. The adhesion to the Covenant of Mayors represents a challenge to achieve the objectives of reducing greenhouse gas emissions by more than 20% by 2020 in its territory and is the tool through which to disseminate best practices and activate a sort of “Domino effect”, able to involve a multiplicity of organizations.

In fact, it offers local administrators the precious opportunity to confront and create synergies, networks and virtuous partnerships, offering visibility for the promotion of local actions. Local authorities undertake to draw up a Basic Inventory of CO2 Emissions (EIB) on the municipal territory, to draw up a Sustainable Energy Action Plan (SEAP), containing the policies and shared initiatives to be adopted and presented, every two years, a report on the implementation of the plan.

The Sustainable Energy Action Plan (SEAP) is the key document in which local authorities define energy policies to pursue planned energy and environmental objectives. It is not only a compulsory instrument under the Covenant of Mayors, but is a very important element of operation in that it outlines the actions to be implemented. The SEAPs represent, therefore, an opportunity for the public sector to play an exemplary role in defining and implementing measures and interventions for energy efficiency and saving on public building structures (offices, schools, health, etc.), the mobility, public lighting, and other energy services.

The aim of this paper is to make a critical analysis of the policies and strategies defined at the national level for the improvement of the energy performance of PA in Italy. This is the awareness of the growing attention in the New Public Management toward patterns of green production and purchasing decisions based on a more sustainable socio-environmental issue.

Consequently, a brief initial analysis is carried out of the main initiatives taken at various levels to optimize energy and environment performance in the PA. Subsequently, the detecting and measurement systems currently in use that provide the data necessary to evaluate potential areas for improvement are set out, and finally, the problematic nature and potential for integration of the concept of energy efficiency in management practice in the sector of the Italian PA is explored.

The research is a contribution towards identifying the driving forces behind potential systems and tools for energy efficiency in the PA. It emphasizes the primary role of the PA at the local level in ensuring and educating to meet the challenges of sustainability. Innovation and change are only possible if participatory processes are really activated. This approach must become the practice and not the exception, definitively overcoming the traditional model that sees, on the one hand, the PA, and on the other, the citizens and businesses.

It is therefore necessary for a shared strategy by all the local actors and a wide use by the PA of emerging technologies, as well as tools for participation and collaboration, to help build sustainable social and economic development.

2. Methodological Approach

The goal of the paper was achieved using secondary qualitative and quantitative data, as they are taken from published literature, from the database, etc., and tertiary data.

First, it was a review of public administration literature involving the topics of energy efficiency policy, including aspects of sustainability, with some keywords. This is in order to define the state of the art regarding the implementation of measures to improve energy efficiency in the PA, and on the role played by the PA in the implementation of sustainable local development. As is known, being part of a qualitative methodology or context sensitivity, the narrative literature review provides a more “open” and flexible research design, where the emphasis is on an in-depth understanding of the topic. The results and their relevance depend on the degree of analysis and are not always generalizable. Despite the risk related to the possibility of not analyzing part of the literature, the methodology adequately identifies the impact of the main categories that influence the aspects considered.

In this way, the essential knowledge base was set up in order to focus research on the main initiatives on energy efficiency in Italy. This in order to highlight the main critical elements that did not make it possible to integrate, in management practice, the concept of energy efficiency in the Italian PA.

Secondary data sources were, predominantly, annual reports, articles published in scientific journal in the last decades and regulatory acts.

Tertiary data, derived from estimates, average values, etc., were used to make appropriate comparisons and support the working hypotheses through comparative analysis of the sector.

The quality level of the data and information collected was assessed and defined with an acceptable degree of approximation. It is based on the following indicators: Reliability of the source; completeness and representativeness of the data; temporal correlation between the study and the collection of the data; and geographic correlation between the context analysis and the reference conditions of the data.

Subsequently, data and information were organized and classified in order to provide understandable and comparable results to support assumptions and work results.

3. Framework

The search for increasing efficiency in the use of energy resources has long been one of the fundamental objectives of European energy policy, and therefore, also of the national one, in consideration of the strategic role it plays in order to start a real transition to the long-awaited low carbon economy. Energy savings and the improvement of energy efficiency are an extraordinary lever, able to contribute to the synergistic achievement of traditional energy policy objectives [4], among which security of supply, the reduction of dependence on imports of hydrocarbons [5], and the reduction of climate-altering emissions [6,7] generating positive effects on competitiveness, technological innovation, and the creation of new jobs.

Energy efficiency is considered a pillar of local sustainability initiatives that promote environmental and particularly economic benefits [8]. It is recognized as one of the most important issues in local sustainability efforts [9,10,11].

Recent public administration literature has been focusing increasingly on the impact of the energy challenges and of the concept of sustainable development on the local governments.

The need to deal with specific energy and environmental challenges, types of decision-making processes, and accessibility of resources have all been cited in the literature as the aspects influencing local governments’ sustainability policies [12,13,14].

Many cities have developed different initiatives to improve their image by reducing their carbon footprint and pursuing the principles of sustainable development [15]. Local action requests for improving energy performance have intensified and have become part of local government agendas [11,16].

Nonetheless, financial resources and a sound financing system are critical to the success of energy efficiency measures [17,18,19].

Financial incentives to reduce energy consumption are often provided as part of utility demand-side management (DSM) programs [20,21].

Several studies include among the main funding measures those that finance buildings and building materials at the local level [10,22,23,24] and their significant environmental, social, and economic benefits [25].

Some researchers claim that cities with a resilient mayor form of government may be more interested in funding energy efficiency because they are more inclined to influences of organized environmental interest groups [26].

Surely, as it emerges from the existing literature the success of sustainability projects and of energy efficiency initiatives depends on specific characteristics of the city/municipality and on the efforts and capacities of local governments in sustainability [10,11,21].

4. Energy Efficiency Initiatives in Italy

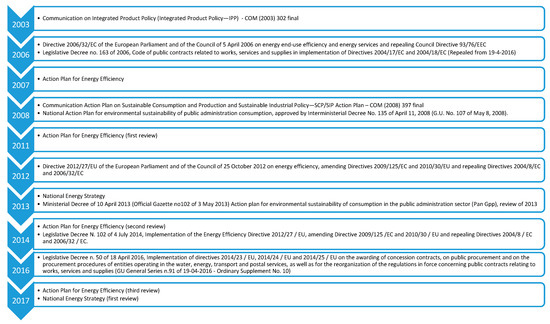

The attention of policy makers has long focused on monitoring programs and energy demand management, defining tools, aims, and objectives (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Main documents for the promotion of energy efficiency in Italy.

On the thrust of the various initiatives undertaken at European level, Italy has adopted, in 2007, the Action Plan for Energy Efficiency—subsequently revised in 2011, in 2014, and in 2017—and, in 2013, the National Energy Strategy (SEN), revised in 2017.

In the first, were defined programs and measures to achieve the goal of energy savings required by Directive 2006/32/EC on end-use efficiency of energy and in energy services—recently replaced by Directive 2012/27/EU.

The national energy efficiency targets for 2020, already indicated in the Action Plan for Energy Efficiency 2014, envisage an energy efficiency improvement program that aims to save 20 Mtoe/year of primary energy, equal to 15.5 Mtoe/year of final energy [27].

The SEN, address and programming tool of the national energy policy established the priorities for the development of the energy sector [28]. Energy efficiency is the first among those identified, thanks to its ability to offer a significant contribution to the achievement of all the main energy policy objectives identified, i.e., the competitiveness, sustainability, security, and economic growth.

The measures taken at national level to achieve these ambitious targets are diversified, some already in place for some time, other in via deployment, articulated on the basis of individual areas of interest and based on a regulatory framework perhaps too wide and articulated.

However, the most important instrument used in our country for the promotion of energy efficiency, transverse and adaptable in all economic sectors (residential, tertiary, industry, and transport) is constituted by the Energy Efficiency Certificates (EEC), also known as White Certificates (WC). The WC mechanism is based on quantitative obligations to increase energy efficiency to the load of the distributors of electricity and gas, which must be achieved through the use of a market mechanism such as that of tradable certificates. The latter are exchanged between operators or on the basis of bilateral contracts, or in a market which is specially established and regulated by the manager of the energy markets (GME), through the rules laid down by the Authority for Electricity and Gas (AEEG) [29].

This mechanism has helped to stimulate the emergence of a market for energy services and has put in place the necessary conditions for a wider spread between economic operators and citizens of the culture of energy efficiency and the rational energy use, an essential element for a greater diffusion of more efficient technologies [30].

The many initiatives in Italy have had effects, leading in the course of the last decade to a progressive improvement of energy efficiency in different sectors, although with significant differences in the specific contributions.

In the industry, the improvement of energy efficiency has been constant and significant: 1.7% per year in the period 2000–2015. Progress in the transport sector has been constant (1% per year). The residential sector has recorded steady progress in energy efficiency, but lower than in the 1990s due to changes in living standards and living comfort: 0.7% per year in the period 2000–2015 [31].

Italy has a final energy consumption per capita among the lowest in Europe, to equality of industrial development, equal to 2.4 tep/per capita. The energy intensity, which represents the synthetic indicator more significant of the interrelationship between energy consumption and dynamics of economic development of a country—expressed by the ratio between the physical energy demand and the GDP—presents, in Italy, values well below the average of the 28 states of the European Union [32]. Obviously, this result derives not only from the structural characteristics and socio-cultural traditions, but also from technological solutions made widely in place by the Italian industrial sector, first in response to the world energy crises from the 1970s, and in more recent times, to the economic-financial crisis.

However, as already pointed out, there are still wide margins for energy efficiency in Italy, with respect to which an important role will have the Legislative Decree N. 102 of 4 July 2014, which transposed, with slight delay, Directive 2012/27/EU. It provides for the promotion of energy efficiency through a variety of measures, even prescriptive. In particular, promotes the energy auditing—to realize, compulsorily and periodically, by 2015 in large enterprises, in a structured and systematic way, by assessors objectives, competent, and impartial—as a crucial tool in strategies to reduce energy consumption.

Particular emphasis also is given to the PA for the nodal role that can play in promoting energy efficiency at national level. In fact, Legislative Decree no. 102/2014 imposes on the PA the annual preparation of a program for energy-saving real estate interventions formulated as a result of the mapping of the heritage public building and related information on energy consumption. This program must be drawn up on the basis of appropriate energy diagnosis and monitored with the support of the National Agency for new technologies, energy, and sustainable economic development [33] and the Manager of Energy Services (GSE), in order to monitor progress. The Decree also consolidates for the PA the use of Green Public Procurement (GPP), which determines the constraints of purchasing products and services through the integration of social and environmental criteria in the procurement procedures of PA products and services. The latter is the main consumer-user in Italy, where purchases made from PA represent a significant item of expenditure, amounting to approximately 17% of GDP, compared to a share on average equal to 18% of GDP in other EU countries.

The adoption of green procurement practices in the PA gives rise not only to a process of rethinking the procurement system, but contributes to rationalizing the steps of use, disposal, and recycling of products, with positive effects in terms of environmental sustainability. Since 2003, the European Commission, within the framework of the Communication on Integrated Product Policy (Integrated Product Policy—IPP)—COM (2003) 302 final, is committed to inserting in the suggested criteria for public procurement, and also to environmental criteria, besides those purely technical-economic, in order to facilitate, as much as possible, the diffusion of products and services that are compatible with the environment. This communication is part of a broader Communication on Sustainable Consumption and Production and Sustainable Industrial Policy—SCP/SIP Action Plan—COM (2008) 397 final—which provides a set of integrated tools to be taken to implement the paths to improve the energy performance and environmental characteristics of products and services used and/or provided by public bodies [33].

In Italy, the process of adoption of the Green Public Procurement policy has been quite gradual, scanned in time from the issuing of several provisions, which impose on Public Administrations the purchase of “green” products. In 2006, was issued the Legislative Decree no. 163, while, in 2008 with the Interministerial Decree of 11 April 2008 no. 135 (Official Gazette no. 107 of 8 May 2008), was enacted on the Action Plan for sustainable consumption in the Public Administration (PAN GPP), and subsequently updated with the Ministerial Decree of 10 April 2013 (Official Gazette no102 of 3 May 2013).

The latter provides for the definition of “Minimum Environmental Criteria” (CAM), for certain “product categories”, which represent the point of reference at the national level in the field of green public procurement.

These criteria have the purpose to support public administrations in the realization of the purchasing procedures that minimize the environmental impacts of products/services along the entire life cycle, i.e., in a Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) perspective.

The inclusion of the CAM in the tender documents became mandatory following the issuing of the new procurement code, Legislative Decree n. 50 of 18 April 2016, which in Article 34 provides for the application of CAM in public tenders.

Therefore, for the Italian public administration, it becomes compulsory to make green purchases, for the products and services for which the Ministry of the Environment has issued the relative CAMs, inserting in the tender documentation at least the technical specifications and the contractual clauses contained in the CAM.

5. Results

Since the 1990s, the Italian organism public administration, consuming more than 1000 tons, have been obliged to appoint an Energy Manager (EM) to promote and spread a culture of energy efficiency within the organization.

However, in spite of regulatory constraints, to date, the Italian PA has appointed very few Energy Managers and remains distinguished by much inefficiency.

In 2017, about 2350 Energy Managers were appointed, of whom only 180 within the PA. While it is impossible for us to make a more accurate estimate, the regulation appears to have been widely disregarded, since only half of the metropolitan cities have sent the nomination, the metropolitan cities of Cagliari, Messina, Palermo, Bari, Florence, Bologna and Genoa are absent. The provincial capitals that have appointed an energy manager are 34 out of 116. There are 57 non-capital municipalities, compared to 1094 in total, which have more than 10,000 inhabitants. The nomination rate for the regions is very low and similar to that of the provinces, 6 out of 20 for the first 23 out of 93 for the latter. Finally, as regards the Ministries, it is not easy to evaluate the rate of non-fulfillment of the appointment for the various Italian Ministries due to the complex organizational chart that characterizes them. Certainly at least one energy manager for each Ministry would be desirable considering that, in 2017, only two appointments of energy managers were received by the Ministry of the Interior [34].

Therefore, it is a well-known fact that the PA’s commitment to improve energy performance is long overdue even if recent studies have estimated that by 2020 the PA could save electricity and thermal energy equal to 0.8 TWh and 1.5 TWh, respectively, through intervention capable of generating substantial investments valued at approximately €1000 billion per year [35].

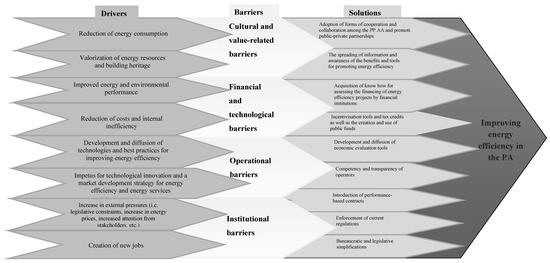

The driving forces for implementing systems and tools to improve energy efficiency range from economic and organizational oriented incentives to those related to environmental and social dimensions. The high cost of energy makes it essential to rapidly identify the most appropriate technological and organizational interventions for reducing the energy costs of the PA and its exposure to volatile energy prices.

In order to improve energy performance, the energy management practices of the PA must be in synchrony with the concept of energy efficiency, effective detection systems have to be implemented and suitable data and information must be available for evaluating the results obtained in order to identify possible areas of improvement.

There are however many cultural, value-related, financial, technological, institutional, and operational issues in the public administration sector that could limit investments in energy efficiency, as shown in Figure 2. It is particularly important to note that if, on the one hand, the PA shows a lack of knowledge and unwillingness to adopt practices and systemic tools for monitoring and control, on the other, it appears to be too complicated and costly. In fact, specific skills and high technical and organizational capabilities are required when implementing programs aimed at efficient and sustainable energy management.

Figure 2.

Streamlining energy efficiency in the Public Administration.

There are also other problems such as the persisting limited availability of financial resources, which discourages the PA from making plans and investments that could yield returns in the medium-long term, that call for the realization of effective energy efficiency improvement strategies.

In addition, the lack of awareness of the benefits and opportunities related to the improvement of energy performance does not permit the development of a “culture” of shared energy efficiency.

Culture in this case expressed both in “socio-environmental” terms (e.g., environmental protection, enhancement of energy, and renewable resources, etc.) and in “individualistic” terms (e.g., everyday use energy conscious, lifestyle, buying patterns, etc.) depends on the degree of sharing of objectives, strategies, and values that the PA can spread internally and among the various external stakeholders. Internally, through the virtuous cycle of strategic sharing and co-responsible design, using communication and training to “contaminate” vertically and across the organization and stimulate feedback flows; externally, through the enhancement in a communicational key, of what has been achieved and the involvement of all stakeholders, whatever their title of relationship with the organization.

From a technical and operational perspective, the complexity of the planning, technical, and financial aspects of energy efficiency measures, as well as the lack of commitment, also relational, of the individuals responsible for their implementation, magnifies and reinforces the barriers to energy efficiency.

Additionally legislative instability and the long and tortuous bureaucratic procedures required by global operations are factors that induce the PA to opt for simple technologies to implement rapidly, but characterized by a short-term vision.

It is therefore necessary to outline innovative approaches, designed specifically for the PA, in order to avoid the spread of “standard practices” and to promote “behaviors” capable of effectively combining responsibility and competitiveness. First, they will have to provide an information and awareness-raising action, capable of highlighting its potential and its impact on economic and social performance. This creates a stable, systematic, and planned link between social and environmental commitment, stakeholder involvement, and communication enhancement of what has been achieved.

Greater diffusion, transparency and communication of good practices and socially responsible behavior could represent an important multiplier, capable of generating a sort of “domino effect”, in a context, such as that of the PA, in which imitation and interpretation are important modalities of management and organizational innovation.

Providing financial incentives is a strategy to stimulate energy saving, which has been shown to be an effective policy tool to promote energy efficiency [36]. Funding for energy efficiency actions can be delivered straight by governments or energy end users. For example, an energy service company (ESCO) can provide funding support to end users whose energy savings are guaranteed by the ESCO. In some cases, and possibly increasingly significantly, local funding is reinforced by incomes generated from the financial savings of energy efficiency projects [36,37], and through user charge programs in which energy end users pay for installation [38].

Furthermore, the debate on its learning capacity through which the problems of past policies must help to rectify future strategies appears to be of fundamental importance.

The suggestion is therefore a joint action in order to foster and accompany the initiatives that arise from below, involving local communities, through an improvement of the institutional context and an investment in human capital.

6. Discussion

Particularly profitable for overcoming knowledge barriers, but also for reducing technical and economic information asymmetries, could be an enforcement of the obligations currently in force, and therefore, the appointment of an energy manager who, in addition to identifying the technological and organizational solutions that are more suitable for optimizing energy resources, able to interface and relate to service providers and energy efficiency solutions.

The adoption of network-based approaches, that is to say, forms of collaboration, but also of aggregation among public administrations, for example, between small neighboring municipalities, could remove both financial obstacles—through the subdivision of transaction costs and the exchange of know-how and best practices currently available—and further limits the implementation of local development models based on the exploitation of endogenous energy, environmental, and socio-economic resources.

There also seems to be an agreement in the literature that stakeholder engagement and participatory processes play a significant positive role in developing and implementing sustainability policies at the local level [39,40,41,42,43]. Portney and Berry [44] have found that the cities most committed to sustainability tend to be more participatory places.

The theoretical perspective of Wang et al. [45]. is based on extant research suggesting that engaging institutional actors and stakeholders is important to generate support for local environmental sustainability initiatives.

A decision-making process that is judicious and that correctly involves stakeholders undergirds the decision with popular acceptability and administrative authority [46], and the results in a more responsible and accountable administration [47]. Moreover, participation grows the probability of the stakeholder accepting the decision [48]. It improves social learning [49], increases project design [50], supports and integrates various interests and opinions [51], and therefore, simplifies project implementation [52].

Understanding attitudes and perceptions of stakeholders is important to decision making and comprehensive environmental policy [53]. At the national level, but also at the Community level, multiple tools have been defined and funds have been allocated to encourage energy efficiency measures in the PA. Among these it is worth mentioning the main projects such as the European Local Energy Assistance (ELENA), the European Energy Efficiency Fund (EEEF), and the Italian Kyoto Fund.

ELENA is a program that aims to provide assistance to local governments for the development of investment programs aimed at improving energy performance at the local level through the provision of grants.

EEEF is an innovative public-private partnership that supports, through the disbursement of contributions, small-scale investments made in the fields of energy efficiency and renewable energy.

Recent research shows that only international collaboration and a networked system of stakeholder interaction can meet the needs of the new development agenda. In more and more countries, governments are forming effective partnerships and strategic alliances with private sector and civil society organizations to confront challenges the public sector cannot tackle alone [54]. However, in the future, we hope for a simplification of the bureaucratic procedure for obtaining funds, at the same time promoting the mechanisms currently in force and implementing innovative methods for obtaining financial resources already in use in other countries. Consider the model of the state of Delaware (USA), introduced in 2011, consisting in the establishment of a private company with public capital, the Sustainable Energy Utility, which assists the PA in the energy audit of its buildings, in the selection of service providers and energy efficiency solutions, and in the related negotiation, as well as in the obtainment of the capital, by issuing a bond placed later on the stock market (NYSE).

To this end, the pressing request by the parties operating in the energy efficiency market to introduce performance-based contractual forms, which are effective and standardized, that guarantee the achievement of the planned savings targets in the feasibility study phase, spreading the best practices related to their use.

Within the broader mix of currently existing instruments, Energy Performance Contracts (EPCs) appear to be particularly innovative, making it possible to share the risks and savings associated with energy efficiency measures with the entity that implements them. The flexibility of these forms of negotiation makes it possible to carry out interventions dimensioned and commensurate with the real capabilities of the actors involved and is able to offer a valid contribution to the PA in achieving more efficient economic, environmental, and energy performances, encouraging the introduction of innovations, not just in technology, but also with organizational and management value [55].

7. Conclusions

The affirmation of energy paradigms is geared towards greater efficiency and sustainability, which is an interesting challenge and presents new opportunities for the Italian PA, which should play a leading role in the complex economic scenario, which is emerging for some years.

The achievement of the multiple benefits linked to the implementation of interventions aimed at improving energy performance requires, on the part of the PA, a rethinking of organizational and functional models, looking for more flexible and less bureaucratic forms of management, and a more dynamic, pervasive approach. and proactive towards initiatives that promote energy efficiency.

The current energy efficiency approach of the Italian PA stems from a strategically unstructured vision, governed by legislation and highly fragmented planning that result in occasional activities rather than medium-long term planned initiatives, enacted after a careful measurement and assessment of the results obtained.

Although the adoption of dimension tailored interventions and, more in general, the diffusion of a solid culture of energy efficiency highlight, as we have seen, numerous problems and barriers, it is essential to move towards new governance systems. The latter, borrowing managerial logics, must allow the formulation of structured energy plans on the results-objective of management, the preparation of an operational program and the systematic verification of the energy performance achieved with the objectives set, with the consequent provision of corrective actions led by the feedback.

There are, in fact, ample margins for the improvement of energy efficiency in the Italian PA, both in relation to the internal dimension—primarily in the management of human resources, in terms of training information and awareness, making these issues more familiar and highlighting their potential and the repercussions on the overall performance of the organization—both in relation to the external dimension, through, for example, the involvement of all those who interact with the PA, such as suppliers, local communities, energy service companies, organizations, and market operators for energy efficiency.

Therefore, it appears that the boundaries of the PA require redefining in order to reconsider the relationships between the public and private sectors and the public institutions in terms of cooperation, collaboration, and partnership, based on reliable and long-lasting relationships, integration of public funds and private resources, and the resultant risk allocation. Moreover, it is essential to exchange experiences and best practices with the aim of guiding the PA and especially local bodies towards lasting sustainability and economic growth through competitiveness, environmental protection, and social development.

Finally, it is necessary to highlight that a governance for sustainability requires a well-functioning public administration with effective organizations and highly qualified, committed staff. Effective organizations have the capacity to deliver results while making change happen. They are able to successfully tackle issues such as performance, risk management, uncertainty, partnerships, assets, human capital, etc.

The research constitutes the conceptual basis for a future paper aimed at mapping the organizations that have implemented energy management models and tools in Italy and the paths followed in terms of horizontal, vertical and diagonal, or mixed progression. Routes influenced by the degree of sharing and involvement of local communities, companies operating in the sector, and assessing whether these behaviors have effectively constituted a lever of qualitative and quantitative differentiation, able to increase the wealth of tangible and intangible resources. Among these, an important role is played by the improvement of economic and environmental performance, the best reputation among social partners, and more generally, a renewed image of the organization, accompanied by an enriched system of values characterized by credibility and good reputation, in which the environmental, economic, and social commitment represents a key factor in competitiveness and differentiation

Author Contributions

The work illustrated in this paper was coordinated by O.M. D.S. designed the research and wrote the paper. S.S. provided advice and suggestions and improved language. All of the authors contributed in equal parts to the writing of the paper.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Jackson, P.M.; Stainsby, L. Managing public sector networked organizations. Public Money Manag. 2000, 20, 11–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nation. The Sustainable Development Agenda. 2018. Available online: https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/development-agenda/ (accessed on 15 October 2018).

- Consiglio Nazionale dei Dottori Commercialisti e Degli Esperti Contabili—Cndcec. Contabilità e Rendicontazione di Sostenibilità del Sistema Della Pubblica Amministrazione e Degli Enti Locali. Policy Statement. 2011. Available online: http://www.cndcec.it/Portal/Default.aspx (accessed on 12 June 2018).

- Oikonomou, V.; Becchis, F.; Steg, L.; Russolillo, D. Energy saving and energy efficiency concepts for policy making. Energy Policy 2009, 37, 4787–4796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geller, H.; Harrington, P.; Rosenfeld, A.H.; Tanishima, S.; Unander, F. Policies for increasing energy efficiency: Thirty years of experience in OECD countries. Energy Policy 2006, 34, 556–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). Summary for policymakers. In Climate Change 2007: Mitigation. Contribution of Working Group III to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Metz, B., Davidson, O.R., Bosch, P.R., Dave, R., Meyer, L.A., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). Summary for policymakers. In IPCC Special Report on Renewable Energy Sources and Climate Mitigation; Edenhofer, O., Pichs-Madruga, R., Sokona, Y., Seyboth, K., Matschoss, P., Kadner, S., von Stechow, C., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- American Council for an Energy-Efficient Economy. The Twin Pillars of Sustainable Energy: Synergies between Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy Technology and Policy; ACEEE Report Number E074; American Council for an Energy-Efficient Economy: Washington, DC, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Portney, K.E. Taking Sustainable Cities Seriously: Economic Development, the Environment, and Quality of Life in American Cities, 2nd ed.; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Saha, D.; Paterson, R.G. Local government efforts to promote the “three E’s” of sustainable development. J. Plan. Educ. Res. 2008, 28, 21–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Hawkins, C.; Lebredo, N.; Berman, E. Capacity to sustain sustainability: A study of U.S. cities. Public Adm. Rev. 2012, 72, 841–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feiock, R.C.; Bae, J. Politics, institutions and entrepreneurship: City decisions leading to inventoried GHG emissions. Carbon Manag. 2011, 2, 443–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krause, R.M.; Feiock, R.C.; Hawkins, C.V. The administrative organization of sustainability within local government. J. Public Admin. Res. 2016, 26, 113–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mar, K.L.; Feiock, R.C.; Handy, S. City adoption of environmentally sustainable policies in California’s central valley. J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 2009, 75, 293–308. [Google Scholar]

- Conroy, M.M.; Berke, P. What makes a good sustainable development plan? An analysis of factors that influence principles of sustainable development. Environ. Plan. 2004, 36, 1381–1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krause, R.M. Policy innovation, intergovernmental relations, and the adoption of climate protection initiatives by U.S. cities. J. Urban Aff. 2010, 33, 45–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buntin, J. Desert storm. Governing 2009, 5, 31–36. [Google Scholar]

- Eyraud, L.; Clements, B.; Wane, A. Green investment: Trends and determinants. Energy Policy 2013, 60, 852–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, A.; Singh, J. Financing energy efficiency in developing countries—Lessons learned and remaining challenges. Energy Policy 2010, 38, 5560–5571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillingham, K.; Newell, R.G.; Palmer, K. Energy Efficiency Economics and Policy; Resources for the Future: Washington, DC, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, J. Trends in Energy Efficiency Investments in China and the US; Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory Publication: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Conroy, M.M. Moving the middle ahead: Challenges and opportunities of sustainability in Indiana, Kentucky, and Ohio. J. Plan. Educ. Res. 2006, 26, 18–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jepson, E.J. The adoption of sustainable development policies and techniques in U.S. cities: How wide, how deep, and what role for planners? J. Plan. Educ. Res. 2004, 23, 229–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leuenberger, D.Z.; Bartle, J.R. Sustainable Development for Public Administration; M.E. Sharp: Armonk, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Zuo, J.; Zhao, Z.Y. Green building research-current status and future agenda: A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2014, 30, 271–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharp, E.B.; Daley, D.M.; Lynch, M.S. Understanding local adoption and implementation of climate change mitigation policy. Urban Aff. Rev. 2011, 47, 433–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministero dello Sviluppo Economico. Piano d’Azione Italiano per l’Efficienza Energetica 2017. Available online: http://www.sviluppoeconomico.gov.it (accessed on 12 September 2018).

- Ministero dello Sviluppo Economico. Strategia Energetica Nazionale: Per un’energia più Competitiva e Sostenibile. 2017. Available online: http://www.sviluppoeconomico.gov.it (accessed on 9 September 2018).

- Supino, S.; Malandrino, O.; Sica, D. Il contributo dei certificati bianchi al miglioramento dell’efficienza energetica in Italia. Esperienze D’impresa 2012, 1, 93–105. [Google Scholar]

- De Paoli, L.; Bongiolatti, L. The promotion of energy efficiency in Italy. Econ. Policy Energy Environ. 2006, 3, 29–68. [Google Scholar]

- Odysee-Mure. Energy Efficiency Trends and Policies. Italy, 2018. Available online: http://www.odyssee-mure.eu/publications/profiles/italy-efficiency-trends-italien.pdf (accessed on 12 June 2018).

- Autorità per l’Energia Elettrica e il Gas. Relazione Annuale sullo stato dei Servizi e Sull’attività Svolta. 2018. Available online: http://www.autorita.energia.it (accessed on 21 October 2018).

- ENEA. Rapporto Annuale Efficienza Energetica. 2018. Available online: http://www.enea.it/it/seguici/pubblicazioni/edizioni-enea/2018/rapporto-annuale-efficienza-energetica-2018 (accessed on 6 November 2018).

- FIRE. Rapporto 2018 Sugli Energy Manager in Italia: Indagini, Evoluzione del Ruolo e Statistiche. Available online: http://fire-italia.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/2018-07-rapporto-energy-manager-2018.pdf (accessed on 21 October 2018).

- Politecnico di Milano. Energy Efficiency Report. L’efficienza Energetica in Italia: Soluzioni Tecnologiche ed Opportunità di Business Nell’industria, i Servizi e la Pubblica Amministrazione. 2013. Available online: http://www.energystrategy.it/ (accessed on 5 September 2018).

- Granade, H.C.; Creyts, J.; Derkach, A.; Farese, P.; Nyquist, S.; Ostrowski, K. Unlocking Energy Efficiency in the U.S. Economy; McKinsey: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Zobler, N.; Hatcher, K. Financing Energy Efficiency Projects. Gov. Financ. Rev. 2003, 14–18. Available online: http://resources.cleanenergyroadmap.com/DMGT_F_ESCfinancing.pdf (accessed on 23 January 2019).

- De Can, S.d.l.R.; Leventis, G.; Phadke, A.; Gopal, A. Design of incentive programs for accelerating penetration of energy-efficient appliances. Energy Policy 2014, 72, 56–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansell, C.; Alison, G. Collaborative governance in theory and practice. J. Public Adm. Res. Theory 2008, 18, 543–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beierle, T.C.; Cayford, J. Democracy in Practice: Public Participation in Environmental Decisions; Resources for the Future: Washington, DC, USA, 2002; pp. 181–182. [Google Scholar]

- Calanni, J.C.; Siddiki, S.N.; Weible, C.M.; Leach, W.D. Explaining coordination in collaborative partnerships and clarifying the scope of the belief homophily hypothesis. J. Public Adm. Res. Theory 2014, 25, 901–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirk, E.; Nabatchi, T.; Balogh, S. An integrative framework for collaborative governance. J. Public Adm. Res. Theory 2012, 22, 1–29. [Google Scholar]

- Siddikki, S.N.; Carboni, J.L.; Koski, C.; Sadiq, A.A. How policy rules shape the structure and performance of collaborative governance arrangements. Public Adm. Rev. 2015, 75, 536–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portney, K.E.; Berry, J.M. Participation and the pursuit of sustainability in U.S. cities. Urban Aff. Rev. 2010, 46, 119–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Liu, C.; Hawkins, C.V. Local Government Strategies for Financing Energy Efficiency Initiatives. Am. Rev. Public Adm. 2017, 47, 672–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keeley, M. Impartiality and participant-interest theories of organizational effectiveness. Adm. Sci. Q. 1984, 29, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowndes, V.; Pratchett, L.; Stoker, G. Trends in public participation: Part 1—Local government perspectives. Public Adm. 2001, 79, 205–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrell, M.E. Citizens’ evaluations of participatory democratic procedures: Normative theory meets empirical science. Polit. Res. Q. 1999, 52, 293–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackstock, K.L.; Kelly, G.J.; Horsey, B.I. Developing and applying a framework to evaluate participatory research for sustainability. Ecol. Econ. 2007, 60, 726–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irvin, R.A.; Stansbury, J. Citizen participation in decision making: Is it worth the effort? Public Adm. Rev. 2004, 64, 55–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffin, C.B. Watershed councils: An emerging form of public participation in natural resource management. J. Am. Water Resour. Assoc. 1999, 35, 505–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konisky, D.M.; Beierle, T.C. Innovation in public participation and environmental decision making: Examples from the great lakes region. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2001, 14, 815–826. [Google Scholar]

- Burger, J. Restoration, stewardship, environmental health, and policy: Understanding stakeholders’ perceptions. Environ. Manag. 2002, 30, 631–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs. Compendium of Innovative Practices in Public Governance and Administration for Sustainable Development. United Nations Publication. 2016. Available online: https://publicadministration.un.org/publications/content/PDFs/Compendium%20Public%20Governance%20and%20Administration%20for%20Sustainable%20Development.pdf (accessed on 15 January 2019).

- Cattarin, G.; Pagliano, L.; Roscetti, A. Il Potenziale per L’efficienza Energetica in Italia e le Prospettive per i Contratti di Rendimento Energetico. Report Nazionale WP3. 2013. Available online: http://www.eerg.it (accessed on 5 September 2018).

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).