Combined Effects of Speech Features and Sound Fields on the Elderly’s Perception of Voice Alarms

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

- The main effects of speech features and sound fields on older adults’ perception of voice alarms.

- (2)

- The interactive effects of speech features and sound fields on older adults’ perception of voice alarms.

- (3)

- The differences between the young and the elderly in the effects of speech features and sound fields on the perception of voice alarms.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Materials

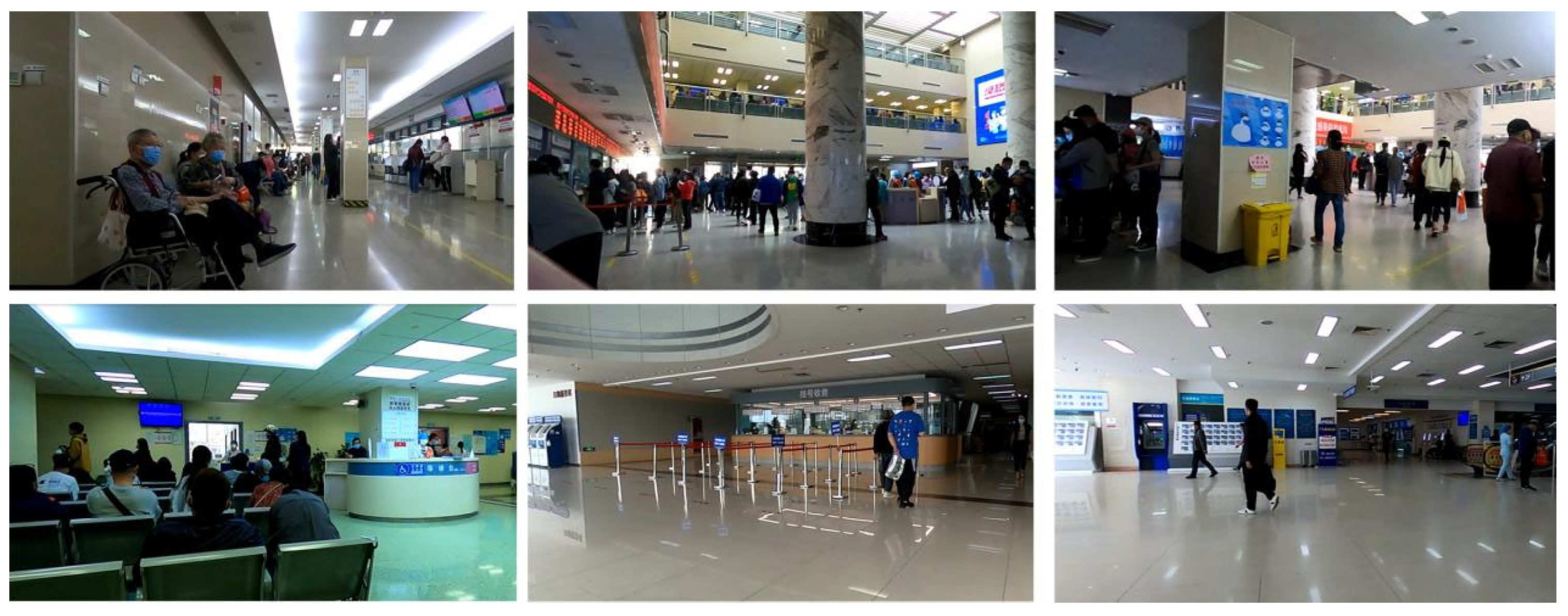

2.2.1. Visual Materials

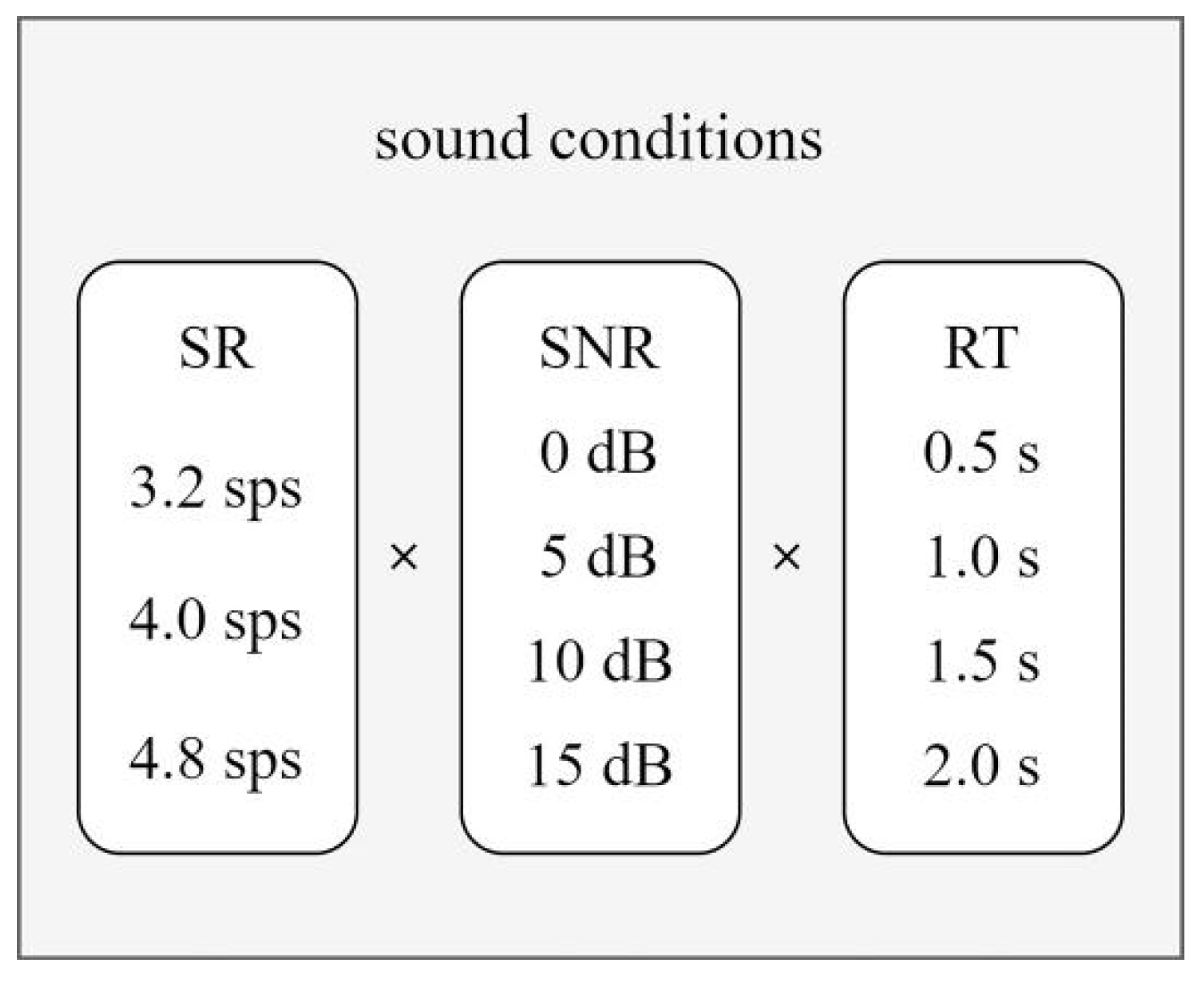

2.2.2. Sound Materials

- (1)

- Speech rate (SR)

- (2)

- Signal-to-noise ratio (SNR)

- (3)

- Reverberation time (RT)

2.3. Indicators

- (1)

- Speech intelligibility

- (2)

- Subjective assessments

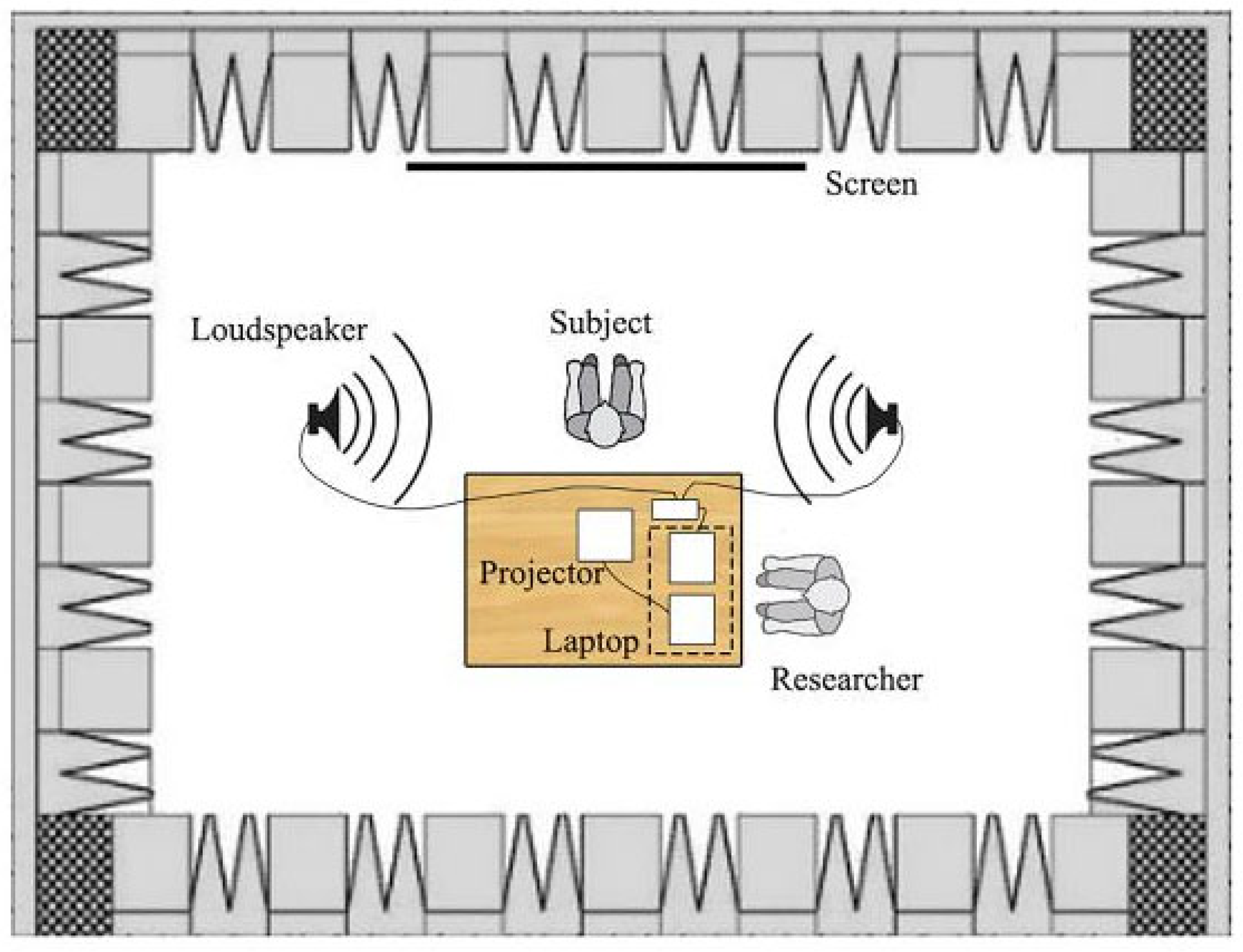

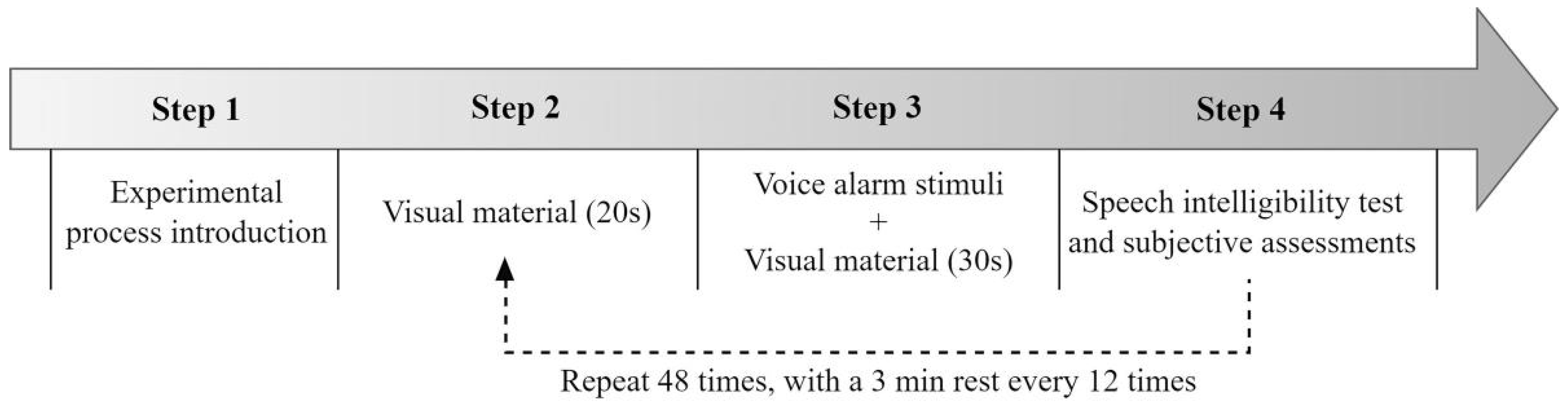

2.4. Procedures

2.5. Data Analysis

3. Results

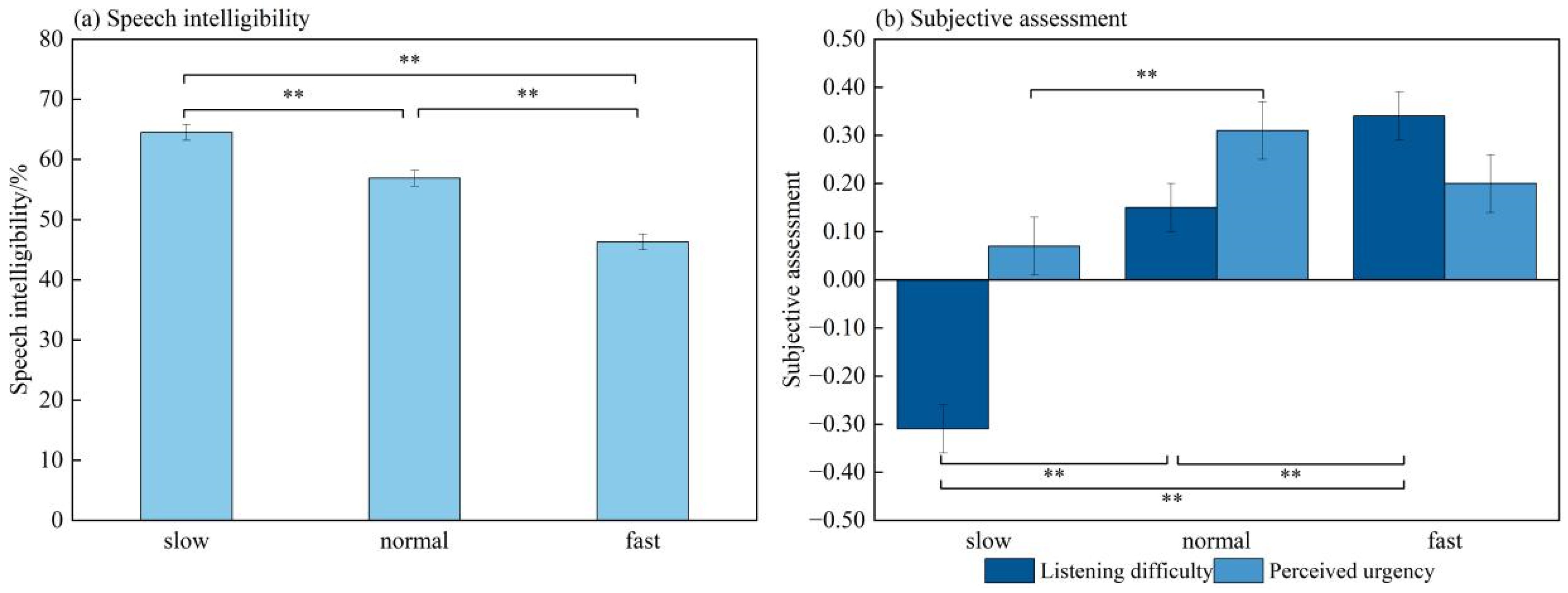

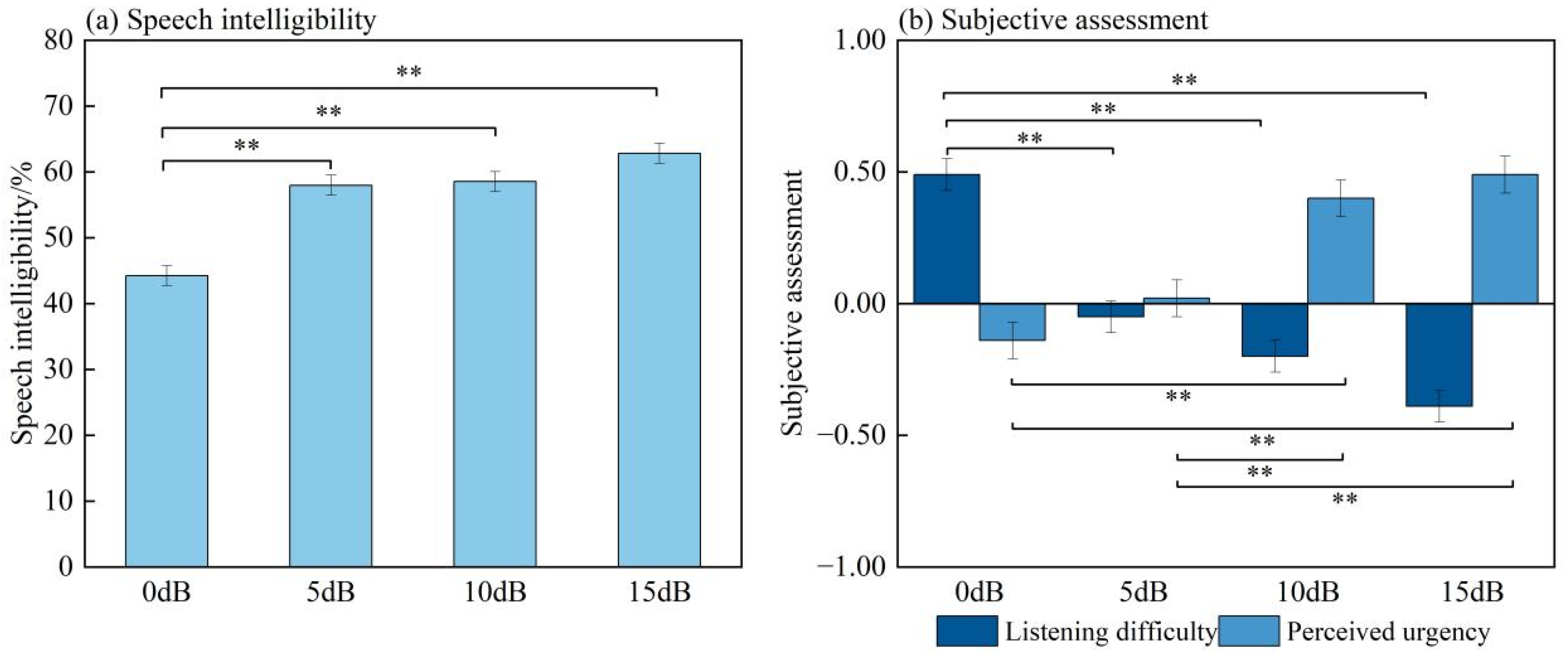

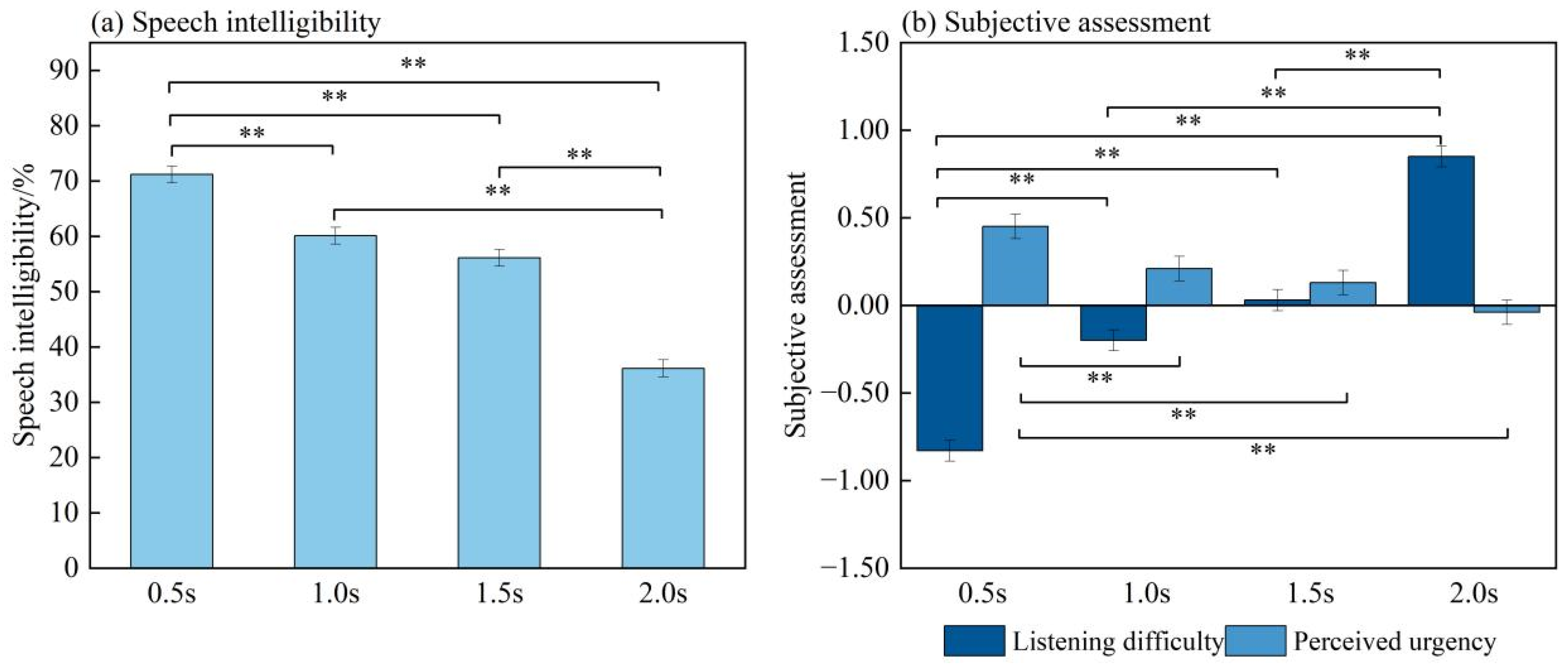

3.1. The Main Effects of Speech Features and Sound Fields

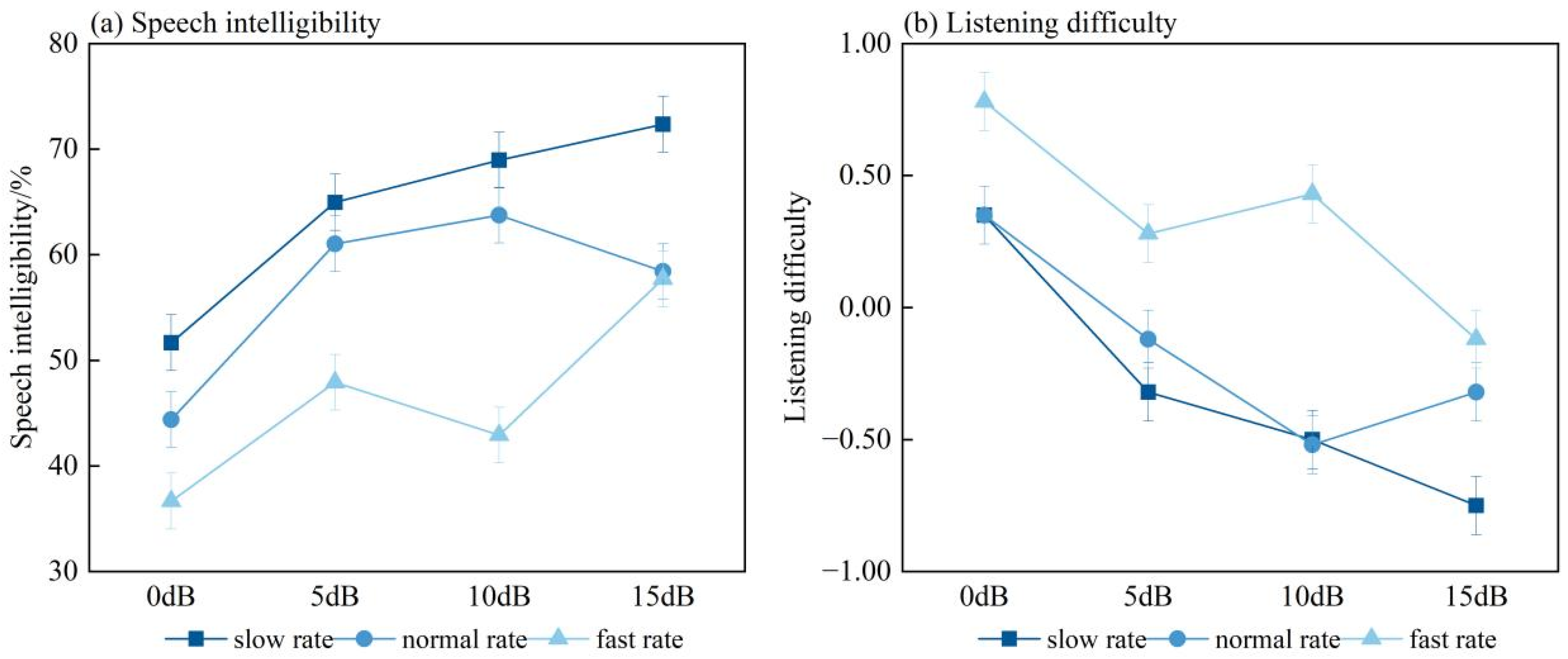

3.2. The Interactive Effects of Speech Features and Sound Fields

3.3. Differences Between Older and Young People

4. Discussion

4.1. Factors Influencing Speech Intelligibility and Listening Difficulty

4.2. Factors Influencing Perceived Urgency

4.3. Guidelines for the Design of Efficient Voice Alarms for the Elderly

4.4. Limitations and Further Research

5. Conclusions

- (1)

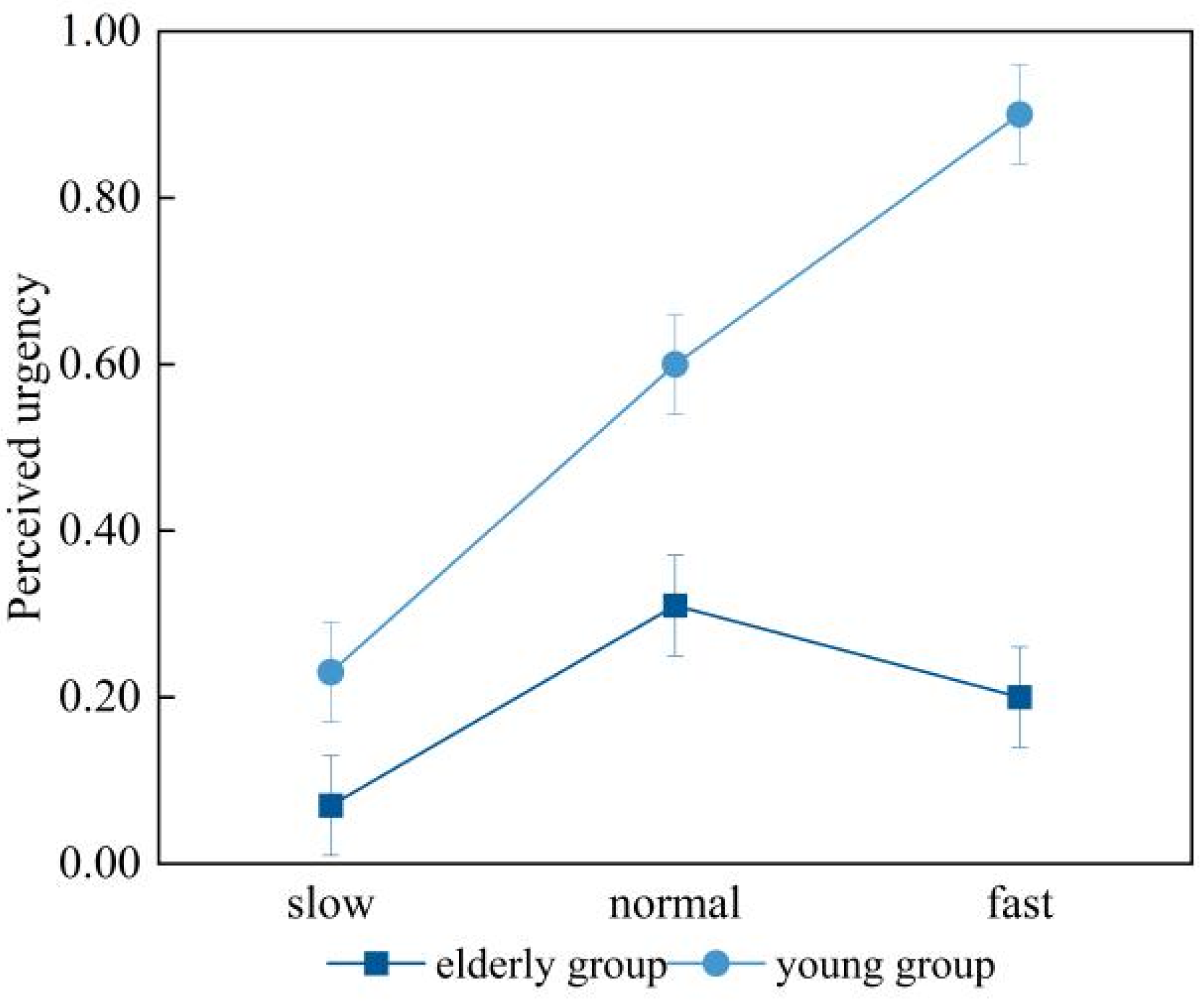

- SR had a significant main effect on speech intelligibility and subjective assessment. Speech intelligibility significantly decreased and listening difficulty significantly increased when SR increased. However, for perceived urgency, the score increased from the slow rate to the normal rate condition and then decreased in the fast rate condition, which differed from the young group, in which the perceived urgency continuously increased and was highest in the fast rate condition.

- (2)

- SNR and RT also had significant main effects on speech intelligibility and subjective assessments. With an increase in SNR, speech intelligibility and perceived urgency significantly increased, and listening difficulty significantly decreased. In contrast, with rising RT, speech intelligibility and perceived urgency significantly decreased, while listening difficulty significantly increased.

- (3)

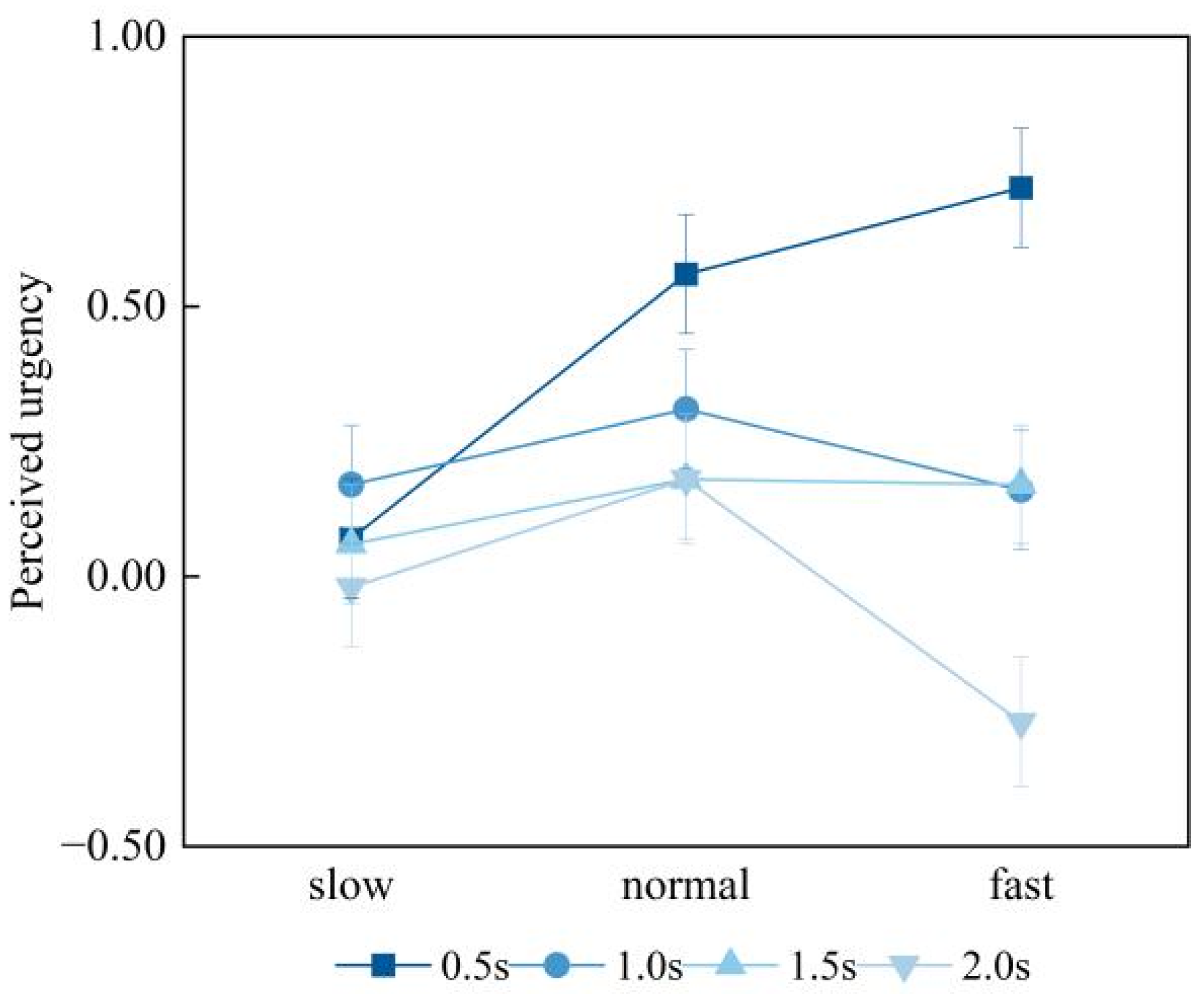

- The interactive results showed that, in contrast to the young group, there was only a significant interactive effect between SR and SNR on speech intelligibility and listening difficulty in the elderly group. RT exerted a relatively stronger independent influence on speech intelligibility and listening difficulty among older adults, and this effect tended not to be substantially moderated by SR or SNR. Regarding perceived urgency, the interactive effect of SR and RT was significant for older adults but not for young adults. In the 0.5 s RT condition, the perceived urgency significantly improved with the increase in SR, while in the higher RT conditions, the perceived urgency increased from a slow to normal rate, but decreased when the speech rate was fast.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Füllgrabe, C.; Moore, B.C.J.; Stone, M.A. Age-group differences in speech identification despite matched audiometrically normal hearing: Contributions from auditory temporal processing and cognition. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2015, 6, 347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xia, X.; Li, N.; Gonzalez, V.A. Exploring the Influence of Emergency Broadcasts on Human Evacuation Behavior during Building Emergencies Using Virtual Reality Technology. J. Comput. Civil Eng. 2021, 35, 04020065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, J.R.I.; Wogalter, M.S. Specific egress directives enhance print and speech fire warnings. Appl. Erg. 2019, 80, 57–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Purser, D. Comparisons of Evacuation Efficiency and Pre-Travel Activity Times in Response to a Sounder and Two Different Voice Alarm Messages; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2009; pp. 121–134. [Google Scholar]

- Sato, H.; Morimoto, M.; Wada, M. Relationship between listening difficulty rating and objective measures in reverberant and noisy sound fields for young adults and elderly persons. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2012, 131, 4596–4605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honghu, Z.; Jia, Y.; Jianxin, P. Chinese speech intelligibility of elderly people in environments combining reverberation and noise. Appl. Acoust. 2019, 150, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, J.; Peng, J.; Zhao, Y. Comparison of speech intelligibility of elderly aged 60–69 years and young adults in the noisy and reverberant environment. Appl. Acoust. 2020, 159, 107096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chlasta, K.; Struzik, P.; Wójcik, G.M. Enhancing dementia and cognitive decline detection with large language models and speech representation learning. Front. Neuroinform. 2025, 19, 1679664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visentin, C.; Prodi, N.; Cappelletti, F.; Torresin, S.; Gasparella, A. Using listening effort assessment in the acoustical design of rooms for speech. Build. Environ. 2018, 136, 38–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morimoto, M.; Sato, H.; Kobayashi, M. Listening difficulty as a subjective measure for evaluation of speech transmission performance in public spaces. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2004, 116, 1607–1613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, H.; Bradley, J.S.; Morimoto, M. Using Listening Difficulty Ratings of Conditions for Speech Communication in Rooms. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2005, 117, 1157–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yancey, C.M.; Barrett, M.E.; Gordon-Salant, S.; Brungart, D.S. Binaural advantages in a real-world environment on speech intelligibility, response time, and subjective listening difficulty. Jasa Express Lett. 2021, 1, 14406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dillon, H.; Gaikwad, S.; Luengtaweekul, P.; Buchholz, J.; Cameron, S. Development of the Test of Listening Difficulties-Universal and Australian Normative Data in Children and Adults. J. Speech Lang. Hear. Res. Jslhr 2025, 68, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ofuji, K.; Ogasawara, N. Verbal disaster warnings and perceived intelligibility, reliability, and urgency: The effects of voice gender, fundamental frequency, and speaking rate. Acoust. Sci. Technol. 2018, 39, 56–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaspierowicz, I.; Sato, S. Predictive models for urgency perception in railway crossing alarm signals: Development and applications for Argentina. Appl. Acoust. 2025, 240, 110926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, J.; Yan, N.; Wang, D. Chinese speech intelligibility and its relationship with the speech transmission index for children in elementary school classrooms. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2015, 137, 85–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodoshima, N. Effects of urgent speech and preceding sounds on speech intelligibility in noisy and reverberant environments. In Proceedings of the 17th Annual Conference of the International Speech Communication Association (Interspeech 2016), San Francisco, CA, USA, 8–16 September 2016; Volume 1–5, pp. 1696–1699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghasemi, M.; Fullenkamp, A.M.; Whitfield, J.A. Consistency of Order Effects in Higher Effort Speaking Styles Between Sessions. J. Speech Lang. Hear. Res. 2025, 68, 3628–3645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, A.H.S.; Lee, P.S.K. Intelligibility and preferred rate of Chinese speaking. Int. J. Ind. Ergon. 2005, 35, 217–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smiljanic, R.; Bradlow, A.R. Speaking and Hearing Clearly: Talker and Listener Factors in Speaking Style Changes. Lang. Linguist. Compass 2009, 3, 236–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yokoyama, S.; Tachibana, H. Subjective experiment on suitable speech-rate of public address announcement in public spaces. Proc. Mtgs. Acoust. 2013, 19, 015081. [Google Scholar]

- Hodoshima, N. Effects of urgent speech and congruent/incongruent text on speech intelligibility for older adults in the presence of noise and reverberation. Speech Commun. 2021, 134, 12–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rennies, J.; Schepker, H.; Holube, I.; Kollmeier, B. Listening effort and speech intelligibility in listening situations affected by noise and reverberation. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2014, 136, 2642–2653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langerak, N.C.; Stronks, H.C.; van Marrewijk, E.F.; Briaire, J.J.; Lemercier, J.; Gerkmann, T.; Frijns, J.H.M. A Novel Artificial-Intelligence-Based Reverberation-Reduction Algorithm for Cochlear Implants Enhances Speech Intelligibility and User Experience. Ear Hear 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, S.; Shubhadarshan, A.; Behera, D.; Sahoo, R. Can working memory capacity predict speech perception in presence of noise in older adult. Int. J. Multidiscip. Educ. Res. 2021, 10, 18–23. [Google Scholar]

- Nilsson, D. Design of fire alarms: Selecting appropriate sounds and messages to promote fast evacuation. In Proceedings of the Sound, Safety & Society, Lund, Sweden, 28 April 2014; Lund University: Lund, Sweden, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, W.; Ma, H.; Wang, C. The effect of characteristics of voice and sound field on the elderly’s speech intelligibility and subjective evaluation of voice alarms. J. Appl. Acoust. 2023, 42, 844–852. [Google Scholar]

- Adams, E.M.; Moore, R.E. Effects of speech rate, background noise, and simulated hearing loss on speech rate judgment and speech intelligibility in young listeners. J. Am. Acad. Audiol. 2009, 20, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moore, R.E.; Adams, E.M.; Dagenais, P.A.; Caffee, C. Effects of reverberation and filtering on speech rate preference. Int. J. Audiol. 2007, 46, 154–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fogerty, D.; Alghamdi, A.; Chan, W. The effect of simulated room acoustic parameters on the intelligibility and perceived reverberation of monosyllabic words and sentences. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2020, 147, EL396–EL402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, H.; Sato, H.; Morimoto, M. Effects of Aging on Word Intelligibility and Listening Difficulty in Various Reverberant Fields. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2007, 121, 2915–2922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon-Salant, S.; Fitzgibbons, P.J. Recognition of multiply degraded speech by young and elderly listeners. J. Speech Hear. Res. 1995, 38, 1150–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goossens, T.; Vercammen, C.; Wouters, J.; van Wieringen, A. Masked speech perception across the adult lifespan: Impact of age and hearing impairment. Hear. Res. 2017, 344, 109–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Profant, O.; Tintera, J.; Balogova, Z.; Ibrahim, I.; Jilek, M.; Syka, J. Functional Changes in the Human Auditory Cortex in Ageing. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0116692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben-David, B.M.; Tse, V.Y.Y.; Schneider, B.A. Does it take older adults longer than younger adults to perceptually segregate a speech target from a background masker? Hear. Res. 2012, 290, 55–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwak, C.; Han, W.; Lee, J.; Kim, J.; Kim, S. Effect of noise and reverberation on speech recognition and listening effort for older adults. Geriatr. Gerontol. Int. 2018, 18, 1603–1608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldwin, C.L. Verbal collision avoidance messages during simulated driving: Perceived urgency, alerting effectiveness and annoyance. Ergonomics 2011, 54, 328–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arai, K. How to transmit disaster information effectively: A linguistic perspective on Japan’s Tsunami Warnings and Evacuation Instructions. Int. J. Disaster Risk Sci. 2013, 4, 150–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kallinen, K.; Ravaja, N. Effects of the rate of computer-mediated speech on emotion-related subjective and physiological responses. Behav. Inf. Technol. 2005, 24, 365–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Ma, H.; Wang, C.; Dong, S.; Hu, W.; He, B. Impact of Echo Interference on Speech Intelligibility in Extra-Large Spaces. Buildings 2025, 15, 3690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zhao, Y. Exploring Factors Influencing Speech Intelligibility in Airport Terminal Pier-Style Departure Lounges. Buildings 2025, 15, 426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pastusiak, A.; Błasiński, Ł.; Kociński, J. Listening Effort in Reverberant Rooms: A Comparative Study of Subjective Perception and Objective Acoustic Metrics. Arch. Acoust. 2025, 50, 321–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Wal, C.N.; Robinson, M.A.; Bruine De Bruin, W.; Gwynne, S. Evacuation behaviors and emergency communications: An analysis of real-world incident videos. Saf. Sci. 2021, 136, 105121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Factors | Speech Intelligibility | Listening Difficulty | Perceived Urgency | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F | Sig. | η2p | F | Sig. | η2p | F | Sig. | η2p | |

| SR | 48.509 | <0.001 *** | 0.065 | 40.947 | <0.001 *** | 0.056 | 4.395 | 0.013 * | 0.006 |

| SNR | 28.377 | <0.001 *** | 0.058 | 38.881 | <0.00 *** | 0.077 | 21.187 | <0.001 *** | 0.045 |

| RT | 93.095 | <0.001 ** | 0.167 | 127.423 | <0.001 *** | 0.216 | 9.462 | <0.001 *** | 0.021 |

| SR × SNR | 2.923 | 0.008 ** | 0.012 | 2.761 | 0.011 * | 0.012 | 0.391 | 0.885 | 0.002 |

| SR × RT | 1.877 | 0.082 | 0.008 | 1.462 | 0.188 | 0.006 | 3.134 | 0.005 ** | 0.014 |

| SNR × RT | 0.974 | 0.460 | 0.006 | 0.842 | 0.577 | 0.005 | 1.470 | 0.154 | 0.010 |

| Factors | Speech Intelligibility | Listening Difficulty | Perceived Urgency | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Elderly Group | Young Group | Elderly Group | Young Group | Elderly Group | Young Group | |

| SR | 0.065 (***) | 0.069 (***) | 0.056 (***) | 0.104 (***) | 0.006 (*) | 0.070 (***) |

| SNR | 0.058 (***) | 0.047 (***) | 0.077 (***) | 0.207 (***) | 0.045 (***) | 0.176 (***) |

| RT | 0.167 (***) | 0.139 (***) | 0.216 (***) | 0.303 (***) | 0.021 (***) | 0.056 (***) |

| SR × SNR | 0.012 (**) | 0.008 | 0.012 (*) | 0.011 (*) | 0.002 | 0.009 |

| SR × RT | 0.008 | 0.024 (***) | 0.006 | 0.016 (**) | 0.014 (**) | 0.012 |

| SNR × RT | 0.006 | 0.026 (***) | 0.005 | 0.018 (*) | 0.010 | 0.016 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Ma, H.; Chen, Q.; Wang, W.; Wang, C. Combined Effects of Speech Features and Sound Fields on the Elderly’s Perception of Voice Alarms. Acoustics 2026, 8, 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/acoustics8010002

Ma H, Chen Q, Wang W, Wang C. Combined Effects of Speech Features and Sound Fields on the Elderly’s Perception of Voice Alarms. Acoustics. 2026; 8(1):2. https://doi.org/10.3390/acoustics8010002

Chicago/Turabian StyleMa, Hui, Qujing Chen, Weiyu Wang, and Chao Wang. 2026. "Combined Effects of Speech Features and Sound Fields on the Elderly’s Perception of Voice Alarms" Acoustics 8, no. 1: 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/acoustics8010002

APA StyleMa, H., Chen, Q., Wang, W., & Wang, C. (2026). Combined Effects of Speech Features and Sound Fields on the Elderly’s Perception of Voice Alarms. Acoustics, 8(1), 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/acoustics8010002