1. Introduction

Among all cancer types, colorectal cancer (CRC) is the most common malignant gastrointestinal tract neoplasm. Its treatment is associated with a series of complications and risks, as well as with changes in all life aspects and side effects. Therefore, after the discharged patients return home, both the family and the patients need adaptation, information about diagnosis, and a care plan and knowledge about the health care network. For rehabilitation of a patient, care must be interdisciplinary and initiated preoperatively to provide diverse information and conditions that facilitate acceptance of the new condition [

1].

However, cancer patients in transition between services are vulnerable to discontinuity and to unsafe health care [

2]. In this sense, transitional care (TC) is an important part of this process. It is defined as a set of actions that aim at ensuring care continuity between transfers from different care levels or places [

3]. In transitional care planning and execution, effective communication among patients, family, and professionals is essential to reduce failures that frequently result in hospital readmissions [

4]. A study that tested the efficacy of TC with 707 patients subjected to surgical procedures showed a 50% reduction in the hospital readmissions of patients with CRC [

5].

In addition, another study conducted with cancer patients and a health team led to the identification of certain weaknesses in the care plan for hospital discharge preparation. Possible explanations identified by the research participants were failures in the educational process for hospital discharge, lack of care protocols, and absence of care of continuity in primary health care (PHC) [

6]. These frequent scenarios in health systems worldwide contribute to lower patient quality of life, longer hospital stays, increased demand for emergency services, and avoidable readmissions [

7].

Despite care transitions being a widely explored topic internationally, the literature remains in its early stages, as evidenced by Alberta’s first Home to Hospital to Home Transitions Guideline [

8]. Above that, despite some innovations having been made to enhance patients’ transition experiences, it remains unclear, specifically in the context of colorectal surgery, which aspects of patient education and care offer the greatest benefit to both patient experience and clinical outcomes [

9]. Therefore, significant gaps continue to exist in the practice and in the public policies, showing the need for applied research to improve transitions from the hospital to the community. No care transition strategy for patients with CRC has yet been tested in Brazil, yielding a knowledge gap with respect to evidence-based practice [

10].

In this context, it is noticed that the translation of research results into clinical practice is urgent and requires interdisciplinary efforts, with the need to reduce the distance between those who produce knowledge and those who need to apply it [

11]. To this end, Implementation Science can be used. It encompasses the scientific study of methods and strategies that facilitate the adoption of evidence-based practices. This is because it contributes to bridging the gap between knowing and doing, through identification of barriers that delay or interrupt the adoption of health interventions that have been demonstrated as being effective [

12]. By applying Implementation Science and a mixed methods approach, it becomes possible to not only evaluate the intervention’s feasibility but also identify context-specific barriers and facilitators, providing actionable insights for the health care system.

In this context, an essential strategy for translating scientific results into practice scenario results is directing research studies to the users’ needs from the beginning of their formulations. The involvement of knowledge recipients/stakeholders in the development or improvement of intervention proposals helps ensure that they are relevant to the health system [

13].

The need to evaluate complex, multifaceted, and multilevel sample data regarding the process of developing and implementing a TC intervention justified the use of a complex mixed methods research (MMR) study [

14]. These studies are useful for assessing the development of interventions and their adoption in practice, as well as for observing the patients’ response and the professionals’ perceptions regarding the implementation of programs [

14]. These studies involve the integration of data emanating via different approaches, which complement each other and express the best of each, compensating for weaknesses and avoiding the possible limitations of a single approach [

15]. Using the typology of Plano Clark and Badiee (2010) [

16], the present study aimed to address the following research questions: What are barriers and facilitating factors for the implementation of a care transition strategy for patients with colorectal cancer, from the hospital to PHC?

This study aimed to evaluate the feasibility, barriers, and facilitators of implementing a care transition strategy for colorectal cancer patients in Brazil, addressing the existing gaps in evidence-based practice and care continuity.

2. Results

2.1. Quantitative Results

As noted previously, a total of 48 patients were randomized to a CG or an IG. Of these, one patient was a follow-up loss (he evolved to death), with analysis of data from 47 patients aged between 45 and 85 years old: 24 in the IG and 23 in the CG. Most of them (n = 26 [55.3%]) were women, White (n = 37 [78.7%]), and married or in a stable union (n = 37 [78.7%]). Further, 41 (87.2%) had been diagnosed for 1 year at the most, 30 (63.8%) were in their first hospitalization, 34 (72.3%) were undergoing surgical treatment, and 12 (28.5%) were undergoing combined treatment. Most of the participants had up to 8 years of study (n = 29 [61.7%]) and incomes of up to one minimum wage (n = 26 [55.35%]). There was no statistically significant difference in the sociodemographic and clinical characteristics between the groups.

There was no statistically significant difference in sociodemographic characteristics as follows: sex (p = 0.454), race (p = 0.135), and marital status (p = 0.243). Regarding clinical conditions, time since diagnosis (p = 0.413), first hospitalization (p = 0.227), and treatment (p = 0.397) were considered. When comparing quality of life at baseline and at 90 days in the intervention group, no statistically significant differences were found between the groups in the domains of physical functioning, role functioning, cognitive functioning, emotional functioning, and social functioning. Regarding the symptoms of nausea and vomiting, there was a reduction in these symptoms at 90 days, with a statistically significant difference between the groups (p = 0.049). When the QLQ-C30 scale was compared between the two assessment time points, statistically significant differences were observed in the control group for fatigue (p = 0.013), pain (p = 0.009), dyspnea (p = 0.034), insomnia (p = 0.008), and diarrhea (p = 0.005).

The Reach dimension was unsatisfactory, scored as 0 (absent), as the planned sample of 118 patients was not achieved; only 48 patients were randomized. Eligible patients totaled 54, with 3 refusals and 3 exclusions due to not meeting inclusion criteria, corresponding to an enrollment rate of 88.9%. The COVID-19 pandemic contributed significantly to the reduced recruitment, which limited the statistical power and affected the ability to detect moderate or small effects.

Efficacy/Effectiveness also was scored as 0 (absent) because statistically significant differences between the outcomes could not be found, due to the desired sample size not being reached. Adoption of the intervention was scored as present because 100% of the professionals who were interviewed understood that transitional care is an essential health care component and that the intervention can be replicated for other target audiences. There were differences between viability of immediate adoption in the routine among the hospital and PHC workers.

Implementation was classified as absent. At the individual level, it is important to note that 50% of the patients interviewed failed to follow the guidance of preventively seeking PHC for care continuity. At the organizational level, there were countless barriers and weaknesses that were explored in the interviews and described in the qualitative results. The Maintenance domain could not be evaluated due to the time taken to conduct the study, and it is intended for it to be evaluated in the future if efficacy of the intervention is confirmed.

Table 1 shows the results of RE-AIM.

2.2. Qualitative Results

Conduction of the pragmatic trial was monitored by means of interviews and meetings with the stakeholders. We consider the following as key people who participated at this stage: Two hospital nurses with 4 years of experience, aged 27 and 30 years old, who were a specialist and an intern at the hospital attending the last year of the Nursing course, and who performed the intervention; three PHC nurses (all specialists, aged between 28 and 51 years old and having between 2 and 19 years of experience) who received the phone calls, part of the TC intervention; hospital and PHC managers (one man and one woman, aged 42 and 48 years old, who had attained Master of Sciences (MSc) and Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) degrees, with 2 to 19 years of experience working in the area); and patients (four women and two men, aged between 47 and 67 years old), all belonging to the Group that received the intervention. When reading the interviews in depth, several statements were selected, which are presented in the categories below.

Via the participants’ statements, it was possible to identify unanimously that the need to improve the transitional processes was recognized, as well as their relevance to care quality and patient safety. One interviewee stated the following: This way in which he’s being already instructed before the procedure will be preparing him for after the procedure. And also, the contact with the basic unit, it’s important to continue the care (Hosp Manager).

The stakeholders understood that the intervention devised is feasible and easy to implement in the health services, as exemplified by the following statement: It’s viable and feasible (…) it’s a matter of planning, of becoming a routine, because, if I work in the hospital and its routine, I won’t release the patient without doing it. (PHC Nur 3). It was also noticed that the PHC professionals were receptive to implementing the intervention and showed the intention of conferring continuity to this process in their job: Implementation of this protocol will help a lot, it will be very beneficial (…) for the unit it’s a much greater subsidy, for when we receive this patient, to know how he is and what care he needs (PHC Nurse 3).

PHC professionals received the TC call in a positive way because it made it possible to learn about the patient’s situation and resulted in home visits and continuity-of-care interventions, turning this receptivity into a facilitating factor to adopt the strategy. One PHC professional noted the following: It’s very interesting that the hospital refers chronic patients to the unit. Regarding us having knowledge of the case, knowing the interventions he received and what to do to continue the care process. It allows preparing a care plan (PHC Nurse 2).

The participants highlighted that the strategy has the potential to be replicated in other populations or other sectors of the hospital: I believe that the post-surgical patients should receive a discharge summary with guidelines and referral to the basic unit (Hosp Nurse1).

In addition, the interviewees considered that the intervention is low-cost, that it has the potential to improve health care, and that the managers would possibly support it. Among the patients interviewed, those who took the discharge summary to PHC, presented better quality care perception: They gave me a piece of paper to take to the health unit, to come and see me at home. I took it, and they monitored me. (…) The nurse from the health unit was attentive to everything. They would come to my house to do the dressing and see me (Paient 6).

Although the multiprofessional team members (i.e., physicians, nutritionists, psychologists, and social workers) were identified as key people in the process, they did not attend the meeting with the stakeholders, and this non-adherence by the professionals was considered an obstacle to implementing the strategy.

Another barrier identified was the nurses’ difficulty executing the protocol when communicating to the research team about the identification of eligible patients, due to work overload in face of the COVID-19 pandemic. There were also difficulties during the intervention, mainly with respect to the telephone calls to PHC, due to the few human resources available and the many duties assigned to the nurses. One hospital nurse noted the following: There’s this issue of time […] even so, it’s very busy […] you know? Difficult to handle. It’s not even about time, but maybe the number of duties we have (Hosp Nurse 2).

The following factors were identified as substantial barriers while performing the trial: difficulties making the transitional care call, lack of time to reconnect when contact was not possible on the first attempt, organization system regarding weekends and holidays (e.g., if the patient was discharged on Saturday, the phone call was not always made), lack of planning of the nurse’s work process and difficulty regarding internal communication between sectors: If the doctor came later and the patient was discharged, you can no longer make the call; so, the next day, you don’t come, you’re off work, and it gets lost. Because you are coming back on Tuesday, and you don’t remember that it happened (Hosp Nurse 2).

In the interviews with the PHC nurses, we identified difficulties related to the lack of materials, such as an insufficient number of computers and telephone lines for the workflow: Only, I think that maybe I had a little trouble, because we only have one phone in the unit. If they call once and I can’t answer, sometimes the person tries twice, three times, and they end up giving up informing us (PHC Nurse 1). Telephone communication difficulties were reported in PHC units due to limited access to phones, affecting the Implementation domain in RE-AIM. The COVID-19 pandemic and high workload further limited adherence to the intervention protocol.

Another barrier identified was the absence of a communication culture across the different health care points. It is important to note that insufficient communication was pointed out by all the professionals and managers interviewed, as well as by the patients, as exemplified by the following: Today, in fact, we’re not used to having this contact, at the time of discharge, with Primary Health Care. (Hosp Man). I think the health department may have some communication. But, with the health unit, I don’t know […] (Patient 6).

In the interviews with the patients, it was identified as a barrier that they did not take the discharge summary to their health unit at the time of the appointment, which indicates that they were possibly not sufficiently oriented, or that the intervention might not have been effective, which should be investigated further in future studies: Not even the health agent came. (…) No, no, no, no […] The right thing to do was to even offer me a nutritionist, but they didn’t offer anything. OK, I didn’t take that paper there (Patient 4).

The professionals interviewed indicated in the survey the following potential strategies to improve the applicability of the intervention: the need to train all team members for adherence, in addition to improving the means of communication, such as using institutional email messages or creating new communication channels. Furthermore, they alluded to the current workload of hospital nurses and suggested the integration of a reference nurse to act in the role of patient navigation.

3. Discussion

In this study, barriers and facilitating factors were identified to implement a TC strategy for patients with CRC. With the support of the RE-AIM tool, it became evident that, of the five items that could be scored, only one was categorized as present (Adoption) and four as absent (Reach, Efficacy, Implementation at the individual level and Implementation at the organizational level). The present investigation stands out by applying the RE-AIM framework not only as a theoretical guide for structuring the intervention and for evaluating its impact, but also as an analytical lens in the qualitative component. By embedding RE-AIM into both strands of the mixed methods research design, the study achieved greater depth in understanding the contextual and systemic facilitators and barriers to implementation—something that has been underexplored in previous transitional care interventions. This approach aligns with the Expert Recommendations for Implementing Change (ERIC) project, where barriers and facilitators identification and stakeholders’ engagement are key to promoting the effective adoption, seamless implementation, and long-term sustainability of a new, intervention, clinical program or practice [

17].

The results regarding the Efficacy domain are discussed in detail in another article that analyzed the primary and secondary outcomes of the RCT. There was difficulty following up the intervention proposed, both in terms of its implementation by the hospital nurses, and in the patients following the guidelines and continuity of care. The participants showed recognition of the need for TC strategies to improve patient care and safety and considered the intervention proposed as being feasible, of low financial cost, and with potential for replication in other areas. The study’s intervention was co-designed with stakeholders and implemented in a pragmatic trial within a public hospital in southern Brazil, where structural and staffing limitations posed real-world challenges. This context adds considerable value to literature, especially for countries with similar health system constraints. Unlike controlled efficacy trials, this pragmatic RCT involved testing the feasibility and utility of a nurse-led, stakeholder-validated care transition strategy, enhancing ecological validity and the likelihood of policy and practice uptake. Furthermore, work overload in the hospital, lack of material resources in the units, and weakness in communication between PHC and the hospital were listed as main barriers.

In relation to the nurses’ difficulty performing the intervention, a research study that addressed patient safety and nurses’ work overload led to the conclusion that work overload was the largest cause of weaknesses in the teams and a generator of possible risks for the patients. Specifically, regarding the effects produced by the COVID-19 pandemic, a study revealed that, in this context, there was intense overload and exhaustion among nurses, resulting in daily challenges and harms in the care provided, as well as in nurse–patient and nurse–team relationships [

18].

Coupled with this context, a Brazilian study on TC offered to chronic patients led to the conclusion that nurses from surgical hospitals had incipient knowledge about transitional care and that, in addition to being fast, the guidelines were focused on the surgical wound and bureaucratic aspects, not performing transitional care in its entirety. In addition, the study led to the identification of the short hospitalization period and the high demand of the units as factors that influence this fragility of care, as well as pointing to the discharge summary as a potential facilitating element of the transactional processes [

19].

These barriers, also identified in our study, hampered operationalization and execution of the intervention proposed. Regarding this difficulty, the authors assert that evidence-based practices that are poorly implemented—or not implemented at all—do not produce the expected health benefits. This is why the integration of scientific implementation knowledge in the early stages of clinical trials and early attention to possible barriers to an intervention are essential and have the potential to produce high-performance research studies, shortening the time between discoveries and their implementation when they are identified as being effective [

20,

21].

Regarding the incipience of communication, a study on the perception of professionals in the ostomy patient care line and the organization of health services revealed differences between PHC and hospital professionals, such as in the definition of the therapeutic path, absence of defined protocols, and effective communication between health teams [

22]. However, in a recent Scoping Review on transitional care management strategies for adult patients, with complex aftercare demands in hospital emergencies, it was shown that establishing effective communication among teams at different care levels is one of the fundamental factors for favorable outcomes [

23].

Lack of communication among professionals and the absence of counter-referrals make it difficult to monitor the patient’s evolution. There is consensus in the literature that, in order to support integration of health systems, it is necessary to focus on articulated and cooperative services with comprehensive planning because integration of health systems is a key component for the promotion of care quality [

4].

Some patients interviewed showed difficulty following the guidelines and continuing the treatment at their reference health unit. In this regard, the authors assert that it is fundamental that the professionals involved in TC invest in patient or caregiver education that meets the patients’ needs and safety. This is because patient involvement in TC planning is fundamental, because poor understanding of the discharge instructions increases the risk of hospital readmissions. However, the literature also indicates that the quality of communication between family members and health professionals needs to receive greater attention from educational institutions during the training of professionals and from health organizations, in the permanent education process [

4].

The participants recognized the importance of TC in the assistance provided to the patients. These data corroborate the literature because the efficacy of TC strategies has been increasingly evident. For example, a study that involved analysis of the efficacy of the hospital’s TC strategy for PHC among 707 patients undergoing CRC surgery revealed a 50% reduction in hospital readmissions among patients with CRC without an ileostomy who received TC, in addition to a reduction of one hospitalization day and lower consumption of opioid analgesics [

5]. In addition, a systematic review with meta-analysis evidenced the effectiveness of TC interventions to improve the care provided to patients with CRC, with significant results in the reduction of hospital readmissions of up to 30 days and in the reduction of hospitalization times [

7].

Regarding the suggestion of having a specific professional in the hospital service to perform TC, this can be understood as a liaison nurse. It was evidenced that, although the research participant did not specifically mention this Nursing specialty, she realized the need for this action in the practice. This can be explained by lack of knowledge about this role in the country because, in Brazil, there is no legislation or regulation on the role of navigator or liaison nurses. Although some institutions and programs have this specialty, their duties, specificities, and importance—just as in the international scope—have not yet been the target of studies and/or publications in the country [

23].

Regarding the potential of this action, a study yielding the clinical results of patient navigation performed by nurses in the Oncology scenario led to the conclusion that the presence of a navigator nurse was effective. The nurse’s performance contributed to the reduction of suffering, anxiety, and depression, to improvements in the control and management of symptoms, improvements in physical conditioning, improvements in care quality and continuity, and improvements in quality of life, as well as to a reduction in the time to initiate the treatment for cancer patients [

24]. Despite the vast literature and successful experiences in North America and Europe, Liaison Nursing or the performance of navigator nurses are still critical points, with practically no discussion and/or feasibility of implementation in the medium term in the Brazilian scenario. Recently, the Federal Nursing Council issued the Resolution COFEN No. 735 [

25], dated 17 January 2024, establishing standards pertaining to the role of nurse navigators and defining their duties and requirements in Brazil [

26]. International studies indicate that liaison nurses improve care continuity and patient outcomes; despite their effectiveness abroad, in Brazil this role remains incipient, highlighting a potential area for future implementation research.

Currently, there is a worldwide gap between the number of clinical research studies produced and the implementation of innovations discovered in public policies and routines of health services, which is referred to by Swiss authors as “Death Valley”, also known as the “Know-Do-Gap”. Using the Implementation Science in research designed to identify and to overcome barriers to knowledge translation, as in the current study, has the potential to shorten time and to lower costs, to generate high social returns and, in this way, to make it possible to build “bridges” over the “Death Valley” [

20].

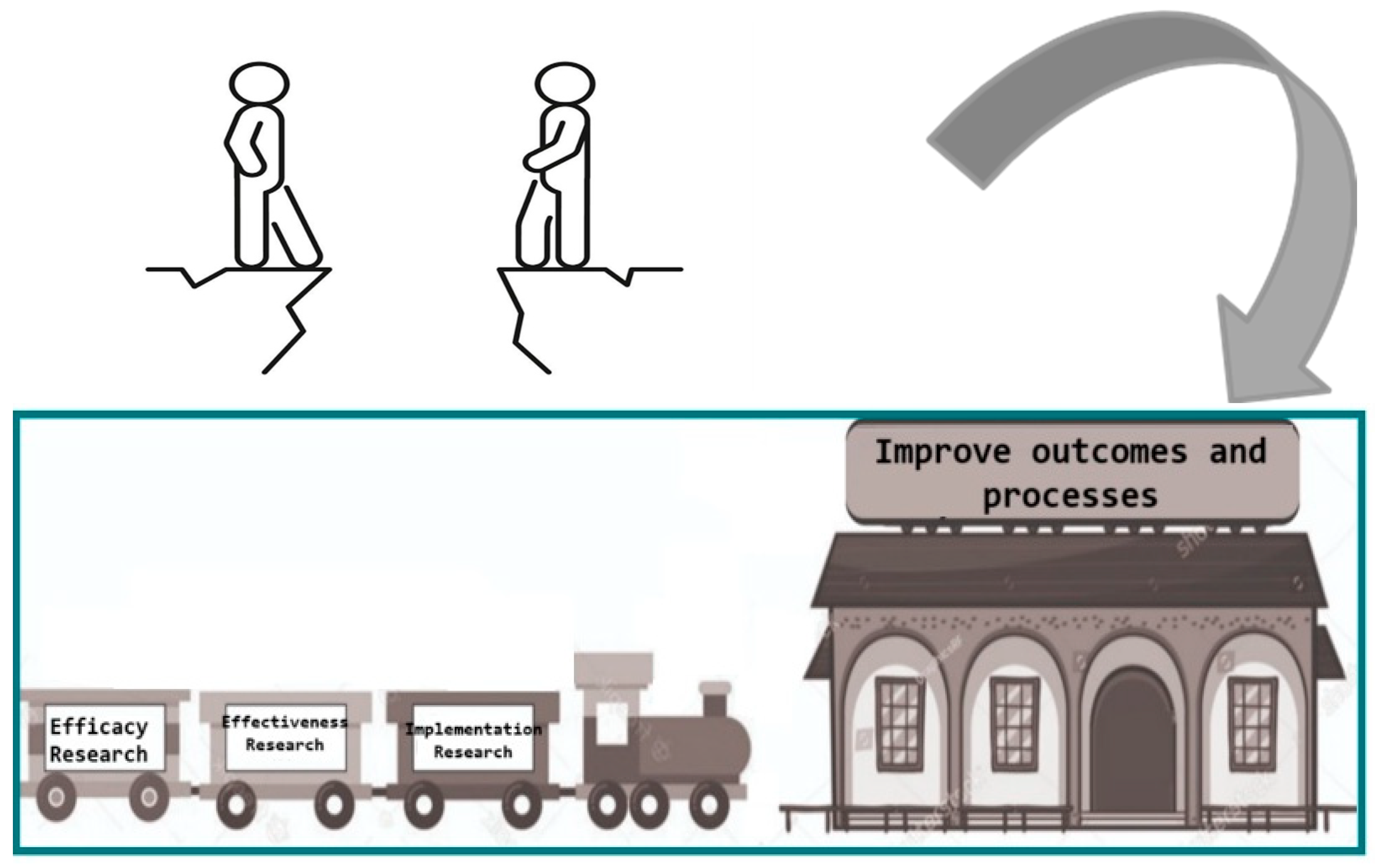

In this regard, and extending the metaphor of the “valley of death,” we propose the image of a train capable of crossing this valley, bringing producers and users of evidence-based practice (EBP) closer together. In this “train of knowledge,” the first carriage would be represented by efficacy research, which aims to improve outcomes and processes in controlled environments. Conversely, the last carriage, the one closest to the final destination, would be occupied by implementation research, such as the study presented here (as illustrated in

Figure 1, created by the authors). The terminus of this journey is the generation of evidence on applicability in real-world practice settings, with genuine potential to enhance care and local health policy. In this specific case, it aims to improve the execution of safe and effective care transition for patients with colorectal cancer (CRC).

Thus, to reduce this distance between knowledge and practice, it is imperative that researchers adopt new ways of thinking and researching, especially involving the knowledge recipients from the beginning of the research process, in order to ensure that research problems will be responsive and relevant to the users and respond to real-world problems [

13].

In addition to the cancelation of elective surgeries due to overcrowding at the hospital where the study was conducted, which potentially reduced the number of patients to be reached, it is important to highlight the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on the intense workload and exhaustion of nurses, both in hospital settings and in primary health care. This situation has resulted in daily challenges and negative impacts on the care provided, on nurse–patient relationships, and on interactions within the nursing team, often hindering communication within the team itself and even more so with other departments, thereby weakening care transition strategies [

27].

Although the sample size was insufficient to demonstrate statistically significant differences between groups, a post hoc power analysis indicated that the final sample size (n = 48) was only adequately powered to detect large effect sizes. Power was limited for detecting moderate or small effects, which might explain the lack of significant findings despite clinically relevant trends. Nevertheless, the nested qualitative study provided valuable insights into barriers and facilitating factors that could not be captured quantitatively, highlighting the complementarity of the mixed methods design. By focusing on colorectal cancer patients—a group at high risk of readmissions and poor post-discharge outcomes—the current study contributes to ongoing efforts to reduce health disparities in surgical and cancer care. The qualitative insights into systemic inequities, communication gaps, and patient experiences extend the literature on transitional care beyond clinical metrics and toward equity-driven implementation science. Moreover, this study promotes patient empowerment and co-participation, aligning with global movements toward participatory research and social justice in health care delivery.

However, as a potentiality, the relevance of having conducted a qualitative study nested in the RCT stands out. The triangulated design—linking quantitative outcomes (e.g., readmission rates, quality-of-life scores) with qualitative perspectives from patients, nurses, and managers—yielded a richly contextualized understanding of the intervention’s functioning. This integration helped validate findings across methods and stakeholder perspectives, thereby strengthening the trustworthiness, credibility, and transferability of the results to other health care settings.

This is because the hybrid method allowed utilization of the best of each approach and facilitated data integration, which took place before, during, and after execution of the TC strategy in the RCT. The integration raised the method and the research as a whole to a stage that would not be reached by executing only one of the approaches (i.e., using a monomethod research approach). This shortens the time and reduces the cost spent on research, while increasing its potential for applicability in the practice, with brevity, when its efficacy is eventually evidenced.

4. Materials and Methods

This study employed a mixed methods [

28,

29,

30] and implementation research design [

31], integrating qualitative and quantitative approaches to evaluate the development, implementation, and effectiveness of a patient-centered care transition (TC) strategy. The methodological approach included three interrelated phases: (1) a qualitative phase to understand stakeholder perspectives, refine the intervention, and ensure its feasibility; (2) a quantitative phase consisting of a randomized controlled trial (RCT) to assess the effects of the intervention on care transition outcomes; and (3) a data integration phase, where qualitative and quantitative findings were combined to explore how and why the intervention succeeded or faced barriers. All phases were conducted in real-world health care settings and guided by the RE-AIM framework, ensuring that the intervention was contextually adapted, practical, and grounded in the experiences of patients, health care professionals, and managers [

31,

32,

33].

4.1. Qualitative Phase

The purpose of an Implementation Research (IR) methodological design is to understand how and why an intervention works or not, as well as to test approaches to improve it [

20,

34,

35]. Initially, before devising the intervention, the managers of the health services and other stakeholders were contacted to identify the professionals who would take part in the study. The intervention to improve patient-centered TC was designed from the results of previous studies [

6,

7,

36,

37,

38] and presented in a meeting to the stakeholders (6 people, including PHC nurses, assistance nurses, hospital managers, and a physician from the Regional Health Coordination Office, who were working in these services for at least 6 months.

During the meeting, diverse evidence from the literature used to prepare the proposal was presented and a discussion was conducted to refine and to validate it. The stakeholders understood that the intervention devised was feasible and should be undertaken by the nurses from the hospital units to increase the chances of being adopted after the end of the trial.

The following points that were adopted in the intervention were defined:

On the first hospitalization day:

Identification of the family member/caregiver who would assist the patient;

They will inform the patient about the stages and needs identified for discharge;

They will discuss the discharge plan with the physician and the patient.

After the surgery:

The nurse will hold a discharge preparation meeting with the patient and caregiver, considering their needs and providing the necessary guidelines, making sure they are understood.

On the discharge day or the first subsequent working day:

The nurse will make a call to the patient’s reference basic health unit and pass the case on to the nurse, as well as deliver a hospital discharge plan with clinical data and a brief hospitalization history, guiding the care continuity in PHC and informing the name of the nurse and telephone number of the reference Basic Unit after discharge.

As a population, we consider stakeholders to be people who have an interest in, interfere with, or have a relationship with the subject matter in question. The sample represented a multilevel sample [

39] consisting of participants with different roles within the system (i.e., patients, family members, professionals, and managers). These professionals were chosen for their involvement with the study and interviewed in a place of their choice, thereby ensuring privacy. And the patients were those who received the intervention prepared (IG of the RCT) and interviewed via telephone calls; all the interviews were recorded and transcribed in full. The participants for the meetings were selected based on the initial contact with the hospital, PHC, and state health management areas in the region.

The data collection instrument consisted of a semi-structured interview elaborated based on the RE-AIM framework. RE-AIM was in the United States to measure the translation to clinical practice, applicability, and impact on public health [

40]. The framework proposes to evaluate Reach, Efficacy, Adoption, Implementation and Maintenance (i.e., RE-AIM); each of these dimensions can be assessed at an organizational or individual level as 0 (absent) or 1 (present) [

40]. A total of 18 interviews were conducted by the main researcher.

Before devising the intervention, four interviews over the phone, lasting 10 min, were conducted with cancer patients from a Database [

36] in order to get to know their perceptions and experiences during their therapeutic paths, so that the meeting of their preferences was ensured when designing an intervention centered on the patients’ needs. During the trial, there were four interviews with nurses at the workplace with an average duration of 20 to 30 min. It was conducted with the objective of analyzing the need for adjustments to improve implementation of the TC strategy. And after the trial, 10 interviews were conducted with the managers, hospital nurses, and patients to understand the barriers and facilitating factors experienced during execution of the intervention.

To observe the ethical precepts, the study participants were identified by letters that represented their professional category, performance locus, and number. Hospital manager (Hosp Man), PHC Nurse 1 (PHC Nur 1), Hospital Nurse 1 (Hosp Nur 1), Patient 1 (Pat 1), and so on.

The data were organized a priori, by similarity of ideas, and organized into two categories: Facilitating factors to implement the intervention and Barriers to implement the strategy.

The integration of quantitative and qualitative data took place at several points and in an interactive way—from elaboration to the evaluation of the intervention [

14,

15,

41], also using the RE-AIM planning tool. More specifically, the integration of quantitative and qualitative data was consistent with what was referred to as a 1 + 1 = 1

approach, or a

meta-mixed methods research approach, which involves the “optimal mixing, combining, blending, amalgamating, incorporating, joining, linking, merging, consolidating, or unifying of research approaches, methodologies, philosophies, methods, techniques, concepts, language, modes, disciplines, fields, and/or teams within a single study” [

27,

42,

43]. For instance, although CTM-15 scores showed minimal improvement in medication understanding, interviews revealed that patients perceived receiving inconsistent guidance from hospital staff, explaining the lack of measurable effect.

In this study, integration of data occurred in all study phases to understand how and why the intervention works or not, considering the RE-AIM dimensions, RCT results, and the interviews. Within this design, demonstrating full integration, a quantitative experimental or intervention study was conducted alongside the collection and analysis of qualitative data within the framework of a qualitative study. The qualitative data collection occurred at multiple points throughout the planning and implementation of the intervention—that is, it took place before, during, and after the intervention, as demonstrated in the CONSORT FLOW DIAGRAM (

Figure 2). First, quantitative and qualitative research approaches were integrated across multiple stages of the mixed methods research process, specifically during data collection, analysis, and interpretation. Second, both types of data were collected, analyzed, and interpreted simultaneously. Third, equal emphasis was placed on the quantitative and qualitative phases. Ensuring a more comprehensive integration of quantitative and qualitative components can enhance the overall quality of a mixed methods study and, in turn, provide valuable evidence to inform improvements in services, systems, and public policy [

44].

4.2. Statistical Analysis

Quantitative data were analyzed using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 22.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Descriptive statistics summarized participant characteristics and study variables: measures of central tendency (means, medians) and dispersion (standard deviations) were calculated for continuous variables, whereas categorical variables were summarized using absolute and relative frequencies (n, %).

For inferential analyses, four group comparisons were conducted to evaluate differences between the Intervention Group (IG) and the Control Group (CG):

Length of Hospital Stay (days)—compared using independent samples t test. The assumption of approximate normality was considered acceptable according to the Central Limit Theorem given the sample sizes.

Proportion of Hospitalizations > 4 days—analyzed using an independent sample t test on the continuous length-of-stay variable for consistency across analyses.

Transition Care Quality—mean scores on the Care Transitions Measure-15 (CTM-15) were compared between groups using an independent samples t test.

Quality of Life at 90 days post-discharge—assessed using the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire (EORTC QLQ-C30) and compared between groups via an independent sample t test. All statistical tests were two-tailed, with significance set at p < 0.05.

5. Conclusions

The strategy developed has the potential to improve care transitions (CTs) for patients from the hospital to primary health care (PHC). All stakeholders recognized that CT processes are essential for care quality and patient safety, as indicated by the “adoption” dimension of the RE-AIM framework, which scored positively. The transition strategy demonstrates potential for application and replication, with low financial cost and the support of managers, as shown in the qualitative phase of the study. However, substantial challenges in its implementation were identified, explored through interviews, and demonstrated using the framework. The dimension of institutional implementation was absent due to factors such as difficulties in service flow, lack of a communication culture across different network points, workload overload of hospital professionals, and insufficient material resources in PHC. Furthermore, at the individual implementation level, regarding health self-management, it was observed that 50% of the interviewed patients did not utilize the intervention strategies to benefit their care.

In addition, the pandemic influenced both the intervention reach and the professionals’ availability to carry it out, hindering its implementation. As suggestions for improvement, the use of an institutional email and of the WhatsApp messaging app, as well as the inclusion of the liaison nurse in the hospital setting, were pointed out as strategies for improving care transition.

The study in question sought to include knowledge users from the beginning of the intervention strategy formulation, as well as the use of an integrated way of knowledge translation strategies and clinical study performance considering the real-world scenario, to advance knowledge production and its practical applicability. The complexity of conducting mixed methods research studies is highlighted because, in addition to RCTs already representing a complex methodology and little used by researchers, nurses, and psychologists, combining them with an implementation research study constitutes a major challenge. This is because there was no funding for this study and because of the incipience of this methodological practice in Brazil.

From a theoretical perspective, this study contributes by demonstrating how the RE-AIM framework can be applied to care transitional strategies, expanding knowledge in implementation research in nursing and health sciences. Practically, it provides feasible, low-cost strategies that can be incorporated into routine services to strengthen continuity of care. The implications of this study extend beyond the Brazilian context, as many health systems worldwide face similar challenges such as resource constraints and fragmented communication. The proposed strategy shows potential for adaptation in international contexts, supporting both research and practice in the field of transitional care.

It is suggested that studies based on a trial of the implementation of TC between hospital and PHC be replicated with larger and different populations, as well as in working conditions closer to normality, outside the pandemic period.