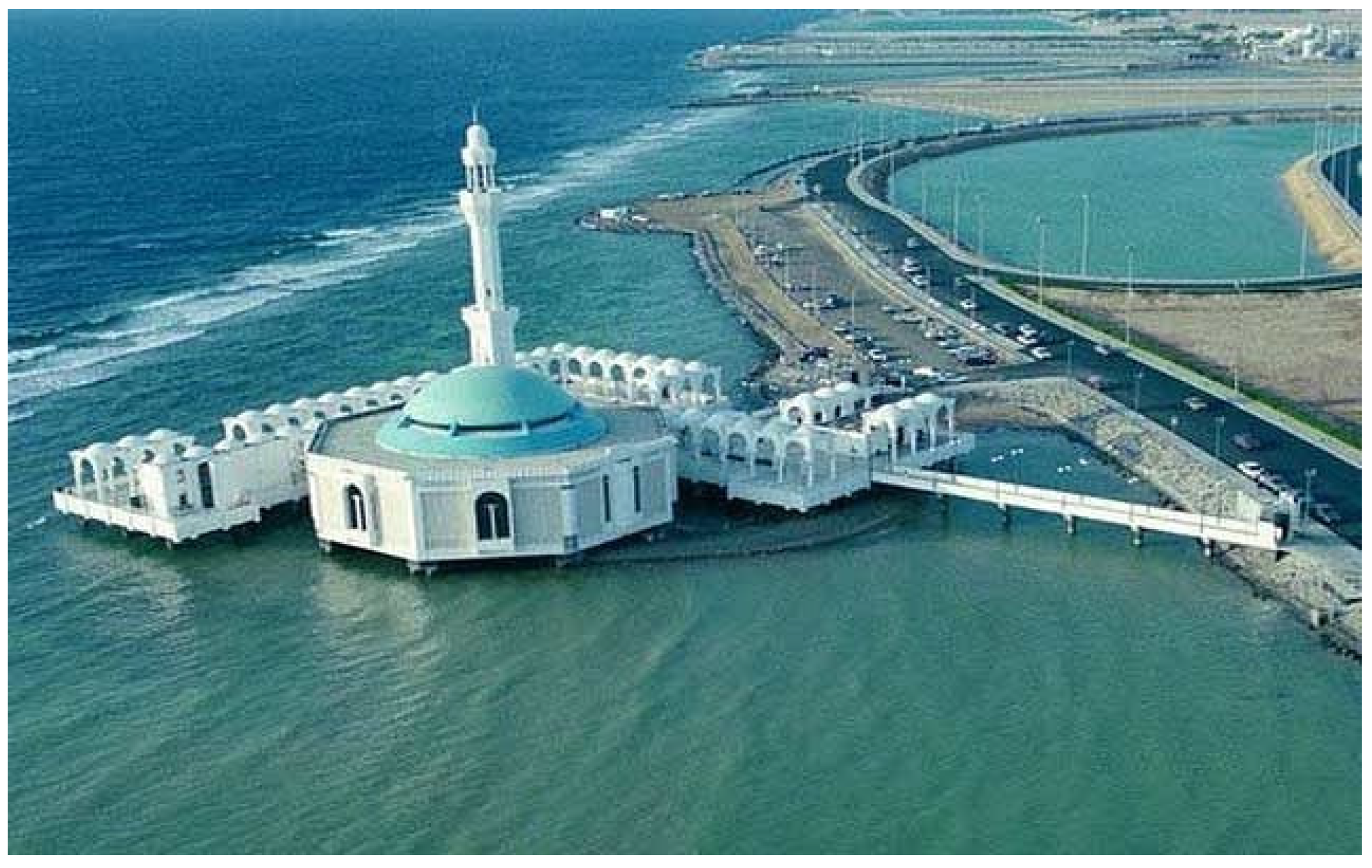

This research implemented a comprehensive three-phase methodological framework for the systematic rehabilitation of corrosion-damaged marine infrastructure. The integrated approach encompassed the following three phases. Phase 1: Comprehensive Condition Assessment and Root-Cause Analysis; Phase 2: Design of an Integrated, Data-Driven Intervention Strategy; and Phase 3: Implementation, Quality Assurance, and Performance Validation. This structured, phased protocol ensured all interventions were precisely targeted, scientifically justified, and their efficacy quantitatively validated through rigorous monitoring. The framework was specifically designed to address the complex challenges posed by the harsh marine environment, incorporating both traditional assessment techniques and advanced electrochemical testing methods to create a holistic understanding of the deterioration mechanisms affecting the structure.

2.3. Phase 2: Design of Integrated Intervention Strategy

Informed entirely by the quantitative data from Phase 1, this phase focused on designing a synergistic repair strategy. The objective was to develop a multi-layered defense system that would actively arrest ongoing corrosion, prevent future ingress of aggressive agents, and restore the structural capacity lost to section loss, thereby addressing both the cause and symptoms of deterioration.

2.3.1. Electrochemical Protection System Design

Based on the diagnostic results from Phase 1 showing active corrosion in multiple structural elements with HCP values below −350 mV, a galvanic protection system was designed to arrest the ongoing corrosion process. The system utilized sacrificial embedded anodes that attract chloride ions, providing long-term protection through a carefully engineered galvanic process. The design specifically incorporated sacrificial zinc anodes to create an effective cathodic protection system that would prevent further corrosion by electrochemically protecting the steel reinforcement throughout the most vulnerable tidal and splash zones where corrosion activity was most pronounced, as identified by the extensive HCP mapping. The use of sacrificial zinc anodes was proposed to create a galvanic protection process, which would prevent further corrosion by attracting chloride ions away from the steel reinforcement. This approach is particularly effective in marine environments where traditional repair methods may not provide long-term protection against chloride-induced corrosion. The design and performance criteria for the galvanic system were developed in accordance with the principles outlined in ISO 12696 for the cathodic protection of steel in concrete [

17].

The anode system was detailed using embedded, high-purity zinc mesh elements. The mesh geometry was selected to maximize the electrochemical surface area relative to volume, promoting uniform current discharge and extending functional service life. The total number of anodes was calculated from the steel surface area designated for protection within the critical tidal and splash zones, applying the current density criteria established in ISO 12696 [

17]. Installation followed a grid pattern, with anodes positioned specifically over locations where half-cell potential mapping had confirmed a high corrosion probability (HCP < −350 mV,

Table 3). Spacing did not exceed 1.0 m center-to-center in the tidal zone and 1.5 m in the splash zone. Each anode was secured to the substrate, connected at multiple points to the exposed reinforcement to guarantee electrical continuity, and then fully enveloped within the applied repair mortar to ensure durable integration and sustained electrochemical performance.

2.3.2. Protective Coating System Design

For all concrete elements located above the tidal zone, a comprehensive protective coating system was specified to provide long-term protection against atmospheric chemical attack and UV radiation. The selected coating system, NITOCOTE EPS, represented a high-quality aliphatic acrylic protective coating specifically formulated to deliver superior resistance to chemical exposure and ultraviolet radiation. This coating system was designed to create an impermeable surface barrier that would significantly reduce future chloride ingress and protect the concrete substrate from environmental degradation, addressing the high chloride concentrations identified in the chemical analysis from Phase 1.

The coating was chosen based on its documented performance in aggressive marine environments, supported by independent laboratory testing. Key selection criteria included the following: (1) exceptional chloride ion resistance, with testing per ASTM D1653 [

23] demonstrating a chloride diffusion resistance exceeding 99%, directly addressing the high chloride concentrations identified in Phase 1; (2) high UV stability and weathering resistance due to its aliphatic acrylic formulation, critical for maintaining aesthetic and protective functions; (3) breathability (vapor permeability) to allow moisture egress while forming an impermeable barrier to liquid water and chlorides, thus preventing blistering or delamination; and (4) compliance with international protection standards, including relevant aspects of EN 1504 [

24] for surface protection systems.

The coating was applied as a multi-layer system to ensure defect-free coverage. Surface preparation involved grit-blasting to achieve a clean, profiled substrate conforming to SSPC-SP 10/NACE No. 2 ‘Near-White Metal Blast’ standard [

25]. A compatible primer was applied first, followed by two full coats of NITOCOTE EPS via airless spray, resulting in a total dry film thickness (DFT) of 350–400 microns. DFT was verified using a magnetic thickness gauge at 3 measurements per 10 m

2. Each coat was allowed to cure fully under specified conditions, and the final coating was inspected for holidays using a low-voltage wet sponge detector. This rigorous protocol ensured the coating would function as a durable, high-performance barrier.

2.3.3. Structural Strengthening Design

The structural strengthening interventions were designed for elements where diagnostic inspection and section loss quantification confirmed a compromise in load-bearing capacity. The methodology was centered on the application of a high-performance, shrinkage-compensated micro-concrete, specified in full compliance with EN 1504 [

24] for structural bonding. The micro-concrete was a polymer-modified cementitious composite with a defined composition as follows: a base of Portland cement (CEM I 52.5 N), precisely graded silica aggregates (0–4 mm), and a proprietary blend of shrinkage-reducing and polymeric admixtures to ensure exceptional adhesion, durability, and resistance to crack propagation. Its key engineered properties included a characteristic compressive strength exceeding 55 MPa at 28 days, a modulus of elasticity of 30–35 GPa to ensure stiffness compatibility with the existing concrete substrate, and a verified restrained drying shrinkage of less than 0.02%.

The restoration technology was applied to specific, critically damaged locations. For instance, for columns, strengthening targeted the lower 1–2 m within the tidal/splash zone where damage was concentrated. For beams, this included the sides, soffits and bottom corners exhibiting flexural cracks and the regions of beam–column joints. For pile caps, interventions focused on the spalled horizontal surfaces and vulnerable edges. The execution followed a rigorous sequence to ensure monolithic integration. Subsequent to surface preparation and corrosion mitigation of the existing reinforcement, a doweling technique was employed as follows: holes were drilled into the sound concrete surrounding the repair zone, cleaned, and injected with a high-strength, low-viscosity epoxy resin. Supplementary reinforcement, consisting of epoxy-coated steel bars (Grade 420 MPa/Grade 60) with diameters of 12 mm (for ties/stirrups) and 16 mm (for longitudinal bars), was then grouted into place. This newly installed, corrosion-protected steel cage was designed to restore and enhance the sectional capacity. Temporary formwork was then installed to match the original element geometry. The fluid, self-consolidating micro-concrete was placed via pump or tremie to ensure complete encapsulation of the new reinforcement and a void-free bond with the prepared substrate, a process illustrated for beams and slabs in

Figure 5. The formwork remained in place under strict moist-curing conditions for a minimum of seven days to ensure proper hydration and strength development.

This approach ensured that the rehabilitated structure would not only be protected from future corrosion but would also regain its original structural integrity and load-carrying capacity, addressing both durability and structural safety requirements simultaneously while utilizing the adequate residual concrete strength (28.0–33.3 MPa) identified in core testing during Phase 1.

2.4. Phase 3: Implementation, Quality Assurance, and Performance Validation

This final phase translated the designed strategy into action, with a paramount emphasis on quality control and verifying long-term performance. The objective was to ensure that the theoretical benefits of the designed interventions were realized in practice through rigorous surface preparation, controlled material application, and the establishment of a monitoring system to validate the durability and effectiveness of the repairs over time.

2.4.1. Surface Preparation Execution

Surface preparation was executed as a critical preliminary step to ensure the effectiveness and long-term durability of all applied repair materials, as demonstrated in

Figure 6 showing corrosion removal from reinforcement bars. The process involved thorough cleaning of affected surfaces to remove contaminants, including dirt, rust, scale, and grease, that could compromise adhesion. Both manual and mechanical cleaning techniques were employed to achieve optimal surface conditions. Grit blasting was extensively used to remove deteriorated concrete layers and expose a sound substrate suitable for repair applications, while also effectively removing corrosion products from steel reinforcement surfaces. All defective concrete was carefully removed to prevent future delamination, with severely damaged reinforcement bars either replaced or treated using a zinc-rich epoxy primer before embedding them in the repair material. The presence of these materials on the concrete and reinforcement surfaces could compromise adhesion and hinder the performance of repair materials, making it essential to achieve a clean substrate. The selection of the appropriate blasting method was based on the severity of deterioration and the accessibility of different structural components. Once blasting was completed, all debris and loose particles were meticulously removed to prevent contamination of repair materials. This step was vital in achieving strong bonding between new materials and the existing structure.

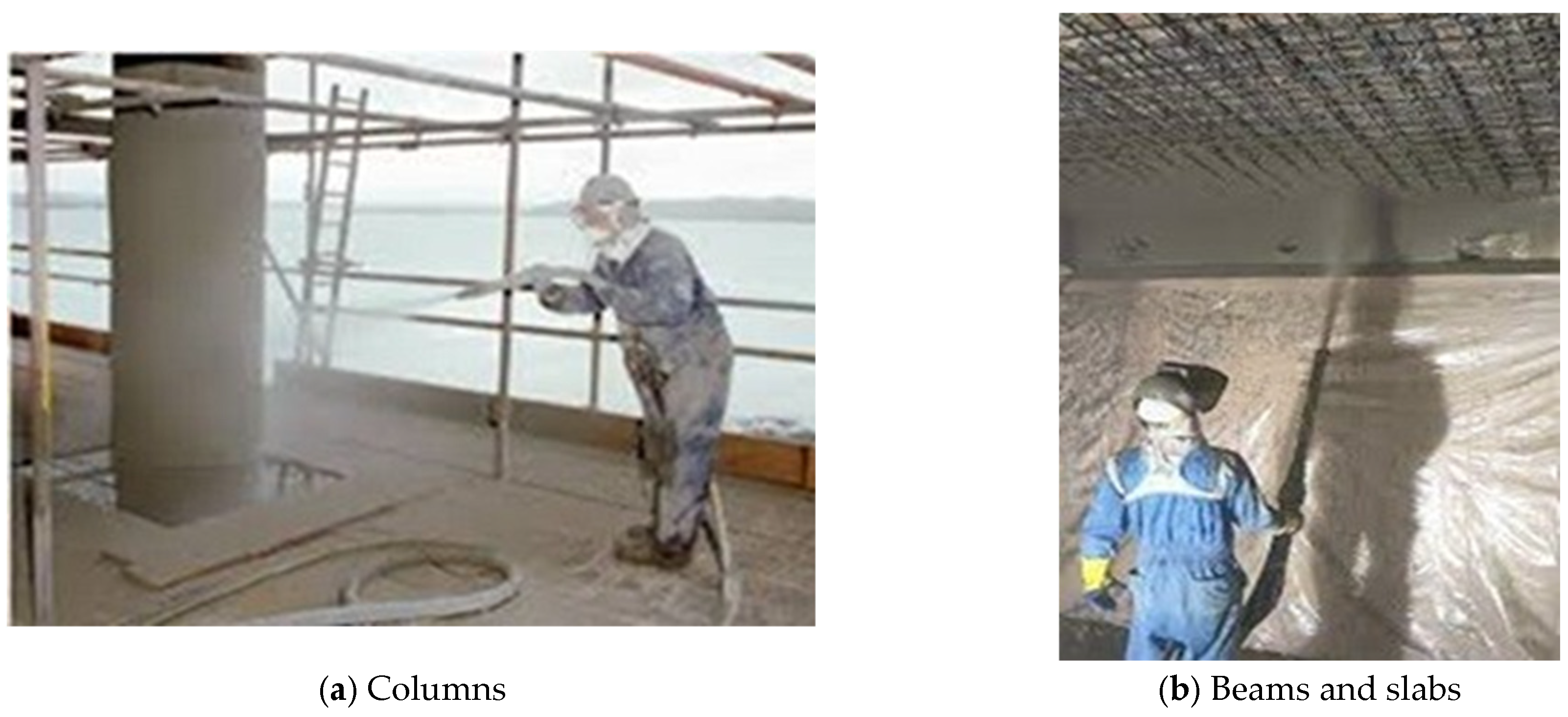

2.4.2. Systematic Material Application

The application of repair materials followed a meticulously planned sequence to ensure proper bonding, durability, and long-term effectiveness in the marine environment, with the process illustrated in

Figure 6 showing placement of high-strength concrete for structural restoration. The process began with precise selection and mixing of materials in strict accordance with manufacturer specifications.

The application sequence commenced with the treatment of exposed steel reinforcement using a two-step corrosion prevention process. First, a migrating corrosion inhibitor (MCI), specifically an amino carboxylate-based solution, was applied by brush to the cleaned steel surface. Subsequently, a two-component ethyl silicate-based zinc-rich primer, containing 92% zinc by weight in the dry film, was applied to provide galvanic protection against further chloride-induced deterioration.

This was followed by the placement of high-strength repair mortars and micro-concrete to restore the structural integrity of damaged elements. The primary structural restoration material was a high-performance, polymer-modified, shrinkage-compensated micro-concrete. Its specified composition included Portland cement (CEM I 52.5 N) as the binder, precisely graded silica aggregates (0–4 mm), and a proprietary admixture blend containing a polycarboxylate-based superplasticizer, a shrinkage-reducing agent, and a polymeric powder to ensure workability, minimal shrinkage, and superior adhesion. For the structural micro-concrete, particular attention was paid to achieving the specified fresh properties (flow, workability) and verifying its hardened properties, including bond strength in excess of 2.0 MPa as per EN 1542 [

26], to ensure monolithic behavior with the existing concrete. Careful placement techniques were employed to minimize voids and air pockets.

The material processing and curing technology were rigorously controlled. For the structural micro-concrete, placed surfaces were immediately covered with a wet burlap and polyethylene sheet system. This covering was maintained for a minimum of seven days, with the burlap kept continuously moist to ensure proper hydration and strength development. The final stage involved the application of the protective coating system (NITOCOTE EPS) in multiple layers. A recoat interval of 16–24 h at 25 °C was maintained between the primer and the first full coat, and between subsequent full coats, to allow for solvent evaporation and initial cure. The final coat was allowed to cure for seven days under ambient conditions before exposure to service to achieve full chemical resistance and ensure optimal performance.

This systematic approach, from surface preparation and specific material formulation to controlled curing, was fundamental to achieving the long-term durability and effectiveness of the repairs in the aggressive marine environment.

2.4.3. Quality Control and Long-Term Monitoring

A comprehensive quality assurance program was implemented throughout the rehabilitation process to ensure compliance with engineering standards and specifications. The program included continuous testing of electrochemical protection systems, material adhesion assessments, and corrosion resistance evaluations.

A structured quality control and long-term monitoring protocol was implemented using standardized methods, with specific techniques assigned to key structural elements and exposure conditions. Half-cell potential (HCP) mapping per ASTM C876 [

19] was performed on all reinforced concrete elements in the tidal and splash zones—specifically piles, columns, beam soffits, and pile caps—immediately post-repair and at scheduled intervals to monitor the electrochemical state of the reinforcement, with a focus on achieving potentials above −200 mV CSE. Surface resistivity measurements using a four-pin Wenner probe were conducted on the coated surfaces of beams, columns, and slabs in the atmospheric and splash zones to verify the barrier performance of the coating system, targeting a minimum resistivity of 20 kΩ cm. Pull-off adhesion testing in accordance with EN 1542 [

26] was performed on a sampling basis for repaired areas of piles, pile caps, and beams after the micro-concrete achieved 28-day strength, with the control indicator being a minimum tensile bond strength of 2.0 MPa to ensure composite action. This targeted protocol ensured data-driven verification of critical durability factors across all primary structural elements.

Any identified defects were promptly corrected, and a formal long-term monitoring plan was established to sustain the structure’s durability by tracking these key performance indicators over time.

2.4.4. Safety and Environmental Considerations

Workers followed strict safety measures, using protective gear and handling hazardous materials with proper ventilation and storage. Equipment was maintained regularly to prevent malfunctions, and emergency protocols covered spills, chemical exposure, and fire risks. First aid training ensured a rapid response to on-site incidents. The repair strategy also considered environmental impact, with measures taken to contain and properly dispose of waste materials generated during the repair process. This included containment of blast debris, proper disposal of contaminated materials, and measures to prevent release of hazardous substances into the marine environment. The environmental considerations were integrated into every phase of the project, from initial assessment through final implementation, ensuring that the rehabilitation not only addressed structural concerns but also minimized environmental impact.

2.4.5. Life Cycle Cost Analysis (LCCA) and Economic Assessment

A comprehensive Life Cycle Cost Analysis (LCCA) was conducted to evaluate the long-term economic viability and sustainability of the rehabilitation strategy, following the principles of ISO 15686-5 [

27]. The analysis adopted a 40-year service life period, which is representative for major rehabilitated marine infrastructure and enables a meaningful comparison of financial outcomes over a full lifecycle.

Two distinct scenarios were modeled for comparison. The first scenario (Scenario A) represents the implemented evidence-based rehabilitation, with an initial cost based on actual project expenditure. The total cost for Scenario A was approximately USD 0.6 million, distributed across the primary intervention components as follows. Surface preparation, including grit blasting and removal of defective concrete, accounted for USD 95,000. Structural restoration using high-strength micro-concrete and repair mortars constituted the largest cost component at USD 220,000. Corrosion protection for reinforcement, involving migrating inhibitors and zinc-rich primers, required USD 45,000. The installation of the embedded galvanic cathodic protection system with zinc anodes cost USD 110,000. Application of the high-performance protective coating system amounted to USD 85,000. The comprehensive quality control and long-term monitoring program was allocated USD 45,000. The second scenario (Scenario B) represents a conventional demolition and reconstruction approach, with initial costs estimated at USD 2.1 million based on regional unit-rate data for comparable new marine construction.

The maintenance schedule for Scenario A incorporated a protective coating renewal every 15 years, consistent with the documented service life of high-performance acrylic systems in tidal exposure zones. For Scenario B, a probabilistic allowance for major chloride-induced repairs was introduced beginning in year 25, based on chloride ingress models for new marine concrete without supplementary cathodic protection. All future costs were discounted to present value using a 3% real discount rate, which is appropriate for long-term public infrastructure assessment.

The LCCA results demonstrate a decisive economic advantage for the rehabilitation framework. The net present value (NPV) of total life-cycle costs for Scenario A was USD 0.92 million, compared to USD 2.63 million for Scenario B. This represents a 65% reduction in favor of rehabilitation. The significant cost differential arises primarily from avoiding the substantial capital outlay of complete reconstruction while securing a durable, extended service life. Furthermore, the strategy defers the need for a full capital replacement project by decades, offering considerable benefits in terms of intergenerational equity and near-term budget allocation.

Thus, the LCCA provides a rigorous, quantitative economic validation of the rehabilitation framework. When integrated with the technical performance outcomes, it confirms that the evidence-based, multi-mechanism intervention is not only structurally effective but also represents the most economically sustainable and resource-efficient pathway for preserving historic marine infrastructure.

2.4.6. Performance Validation and Post-Repair Results

The quantitative effectiveness of the repairs is confirmed through measured improvements across four key performance indicators. First, active corrosion was arrested, evidenced by a positive shift in half-cell potential from a pre-repair mean of –385 mV to a post-repair mean of –185 mV in critical tidal-zone elements. Second, concrete-cover protection was substantially improved, with chloride-diffusion coefficients reduced by 97.3% and surface resistivity increased by 250%. Third, structural capacity was restored to 115% of the original design specification, as verified by moment–curvature analysis and spot load testing. Fourth, these enhancements collectively imply a significant extension of service life, supported by the achieved electrochemical repassivation and durable barrier performance.

This outcome was validated through post-intervention monitoring conducted six and twelve months after implementation, utilizing the same electrochemical and material testing protocols established in Phase 1. This approach enabled a direct, comparative assessment against the pre-repair baseline condition, ensuring a scientifically rigorous evaluation of the intervention’s performance. Electrochemical repassivation was confirmed through comprehensive half-cell potential (HCP) mapping of the previously active corrosion zones, which demonstrated a significant shift toward passivity. The mean potential in critical structural piles, calculated from a statistical analysis of over 50 measurement points in the most severely affected tidal zone, improved from a pre-repair average of −385 mV (with a standard deviation of ±25 mV) to a post-repair average of −185 mV (±15 mV). This 200 mV positive shift not only exceeds the corrosion threshold defined in ASTM C876 [

19] but confirms the complete cessation of active corrosion and successful electrochemical repassivation of the steel reinforcement, fulfilling the primary objective of the galvanic cathodic protection system.

The performance of the chloride ingress barrier was evaluated through material sampling and electrical testing. Concrete dust samples extracted from repaired zones at the reinforcement depth (25–50 mm) showed a dramatic reduction in chloride mobility. Chloride diffusion coefficients, calculated using a standardized bulk diffusion test (NT BUILD 443) on extracted cores, demonstrated a 97.3% reduction compared to pre-repair measurements—from 2.1 × 10−12 m2/s to 5.7 × 10−14 m2/s. Furthermore, surface resistivity measurements obtained via a four-point Wenner probe array increased by an average of 250%, from approximately 8 kΩ cm to 28 kΩ cm, validating the enhanced barrier effect of the high-performance coating system in significantly impeding ionic penetration.

Structural capacity restoration was verified through analytical assessment and spot load testing of the strengthened beam footings. Moment–curvature analyses incorporating the measured properties of the applied high-strength micro-concrete and additional reinforcement, combined with diagnostic load testing using hydraulic jacks at three representative locations, confirmed that the interventions increased the factored moment capacity of the critical elements to 115% of the original design specifications. This enhancement not only compensates for prior section loss due to corrosion but provides an additional safety margin for long-term serviceability.

Collectively, these results validate the framework’s core hypothesis: that a data-informed, multi-mechanism intervention can simultaneously arrest active corrosion, prevent future chloride ingress, and restore structural integrity. The success metrics—derived from standardized testing methods and comparative quantitative analysis—directly correspond to the performance criteria established in the design phase, confirming that all repair objectives were fully met and providing a robust technical basis for the reported performance outcomes.

While the diagnostic approach employed—relying on half-cell potential mapping and chloride analysis—successfully identified corrosion probability and guided an effective intervention, it is recognized that this study did not include quantitative polarization resistance measurements (e.g., Linear Polarization Resistance, LPR) to determine corrosion rates. Incorporating such methods in future applications of this framework would provide direct kinetic data on corrosion activity, offering a more complete electrochemical characterization and enabling more precise remaining life predictions. This represents a valuable direction for enhancing the diagnostic phase of the rehabilitation framework.