Estimation of the Circadian Phase Difference in Weekend Sleep and Further Evidence for Our Failure to Sleep More on Weekends to Catch Up on Lost Sleep

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

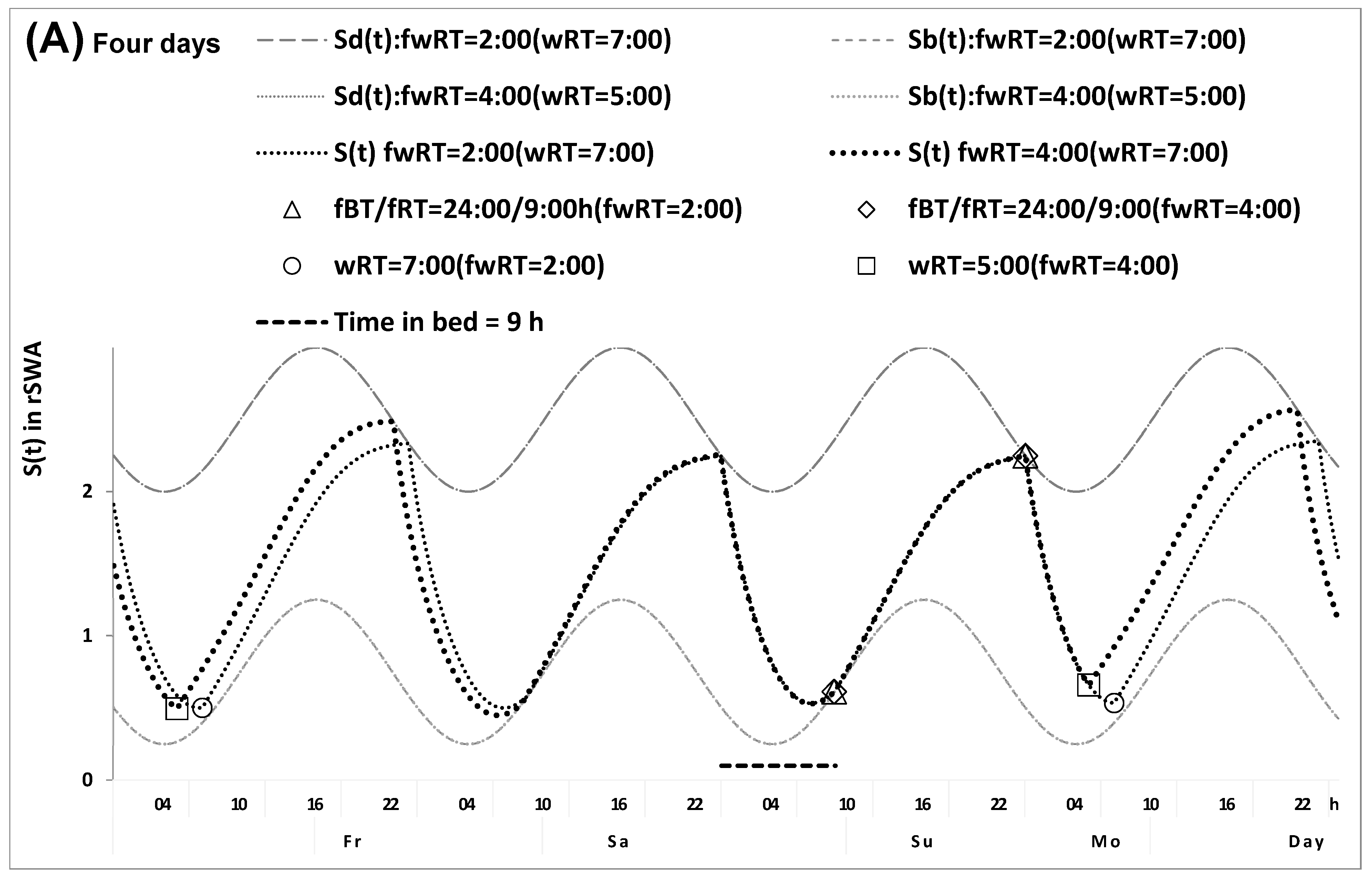

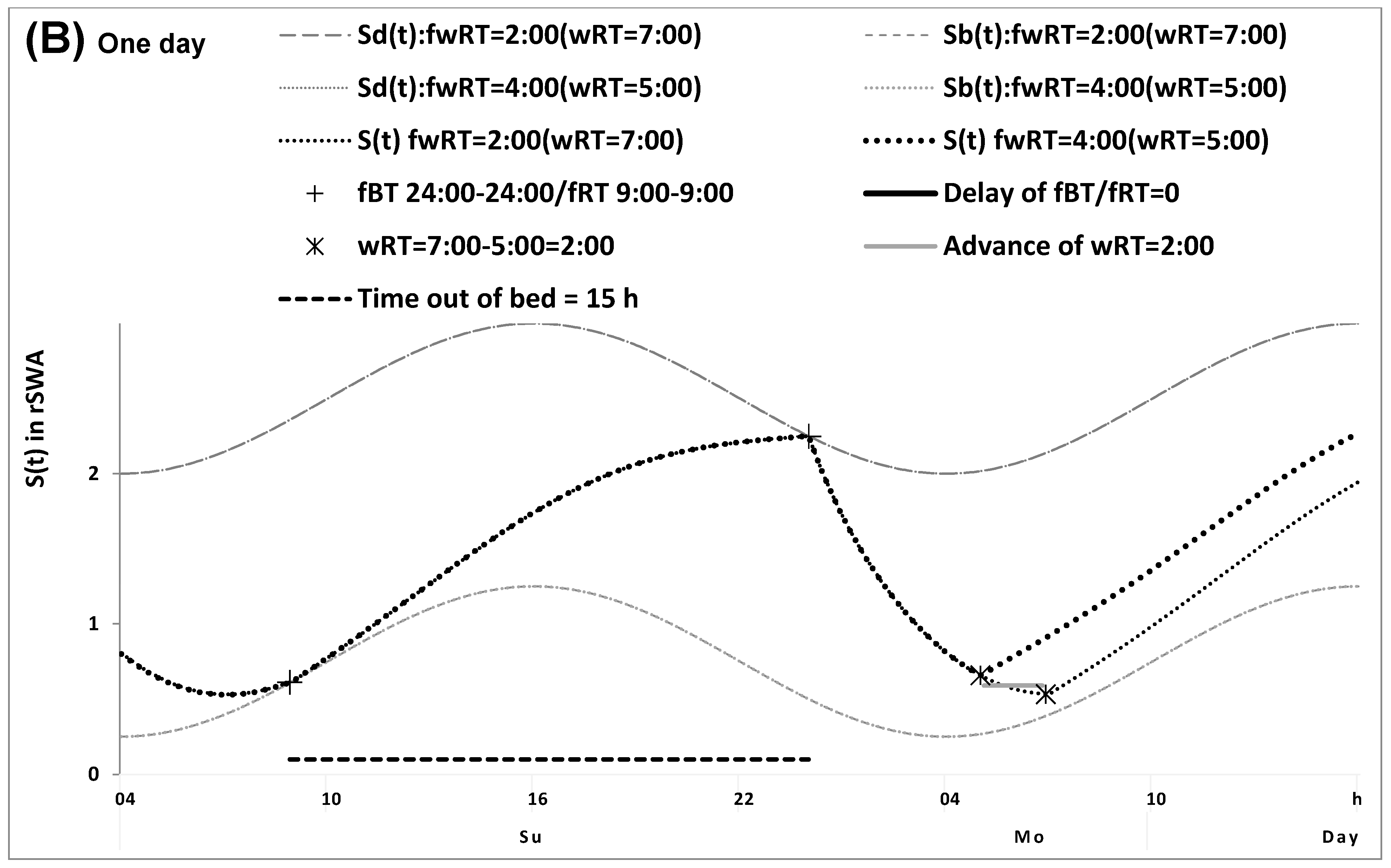

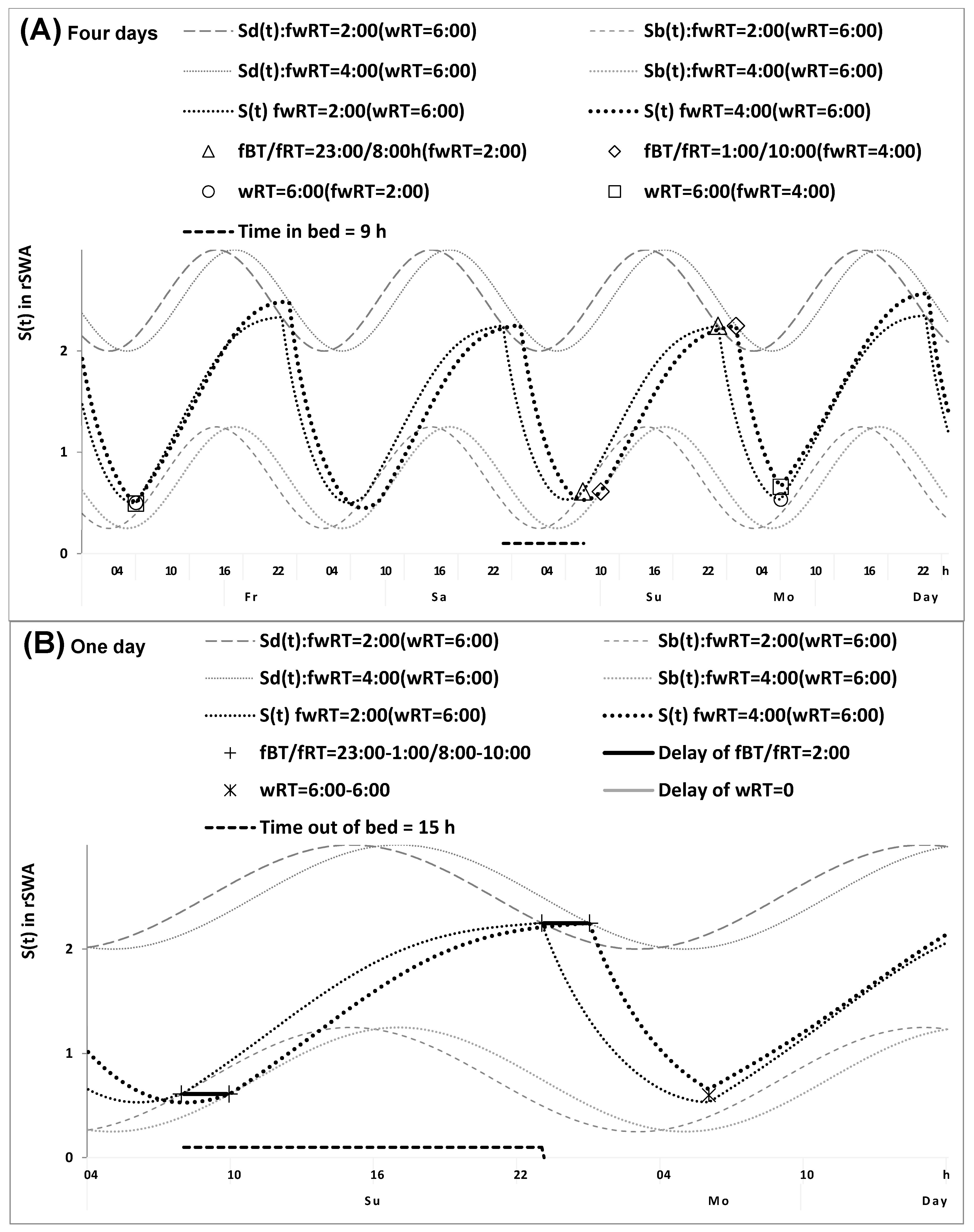

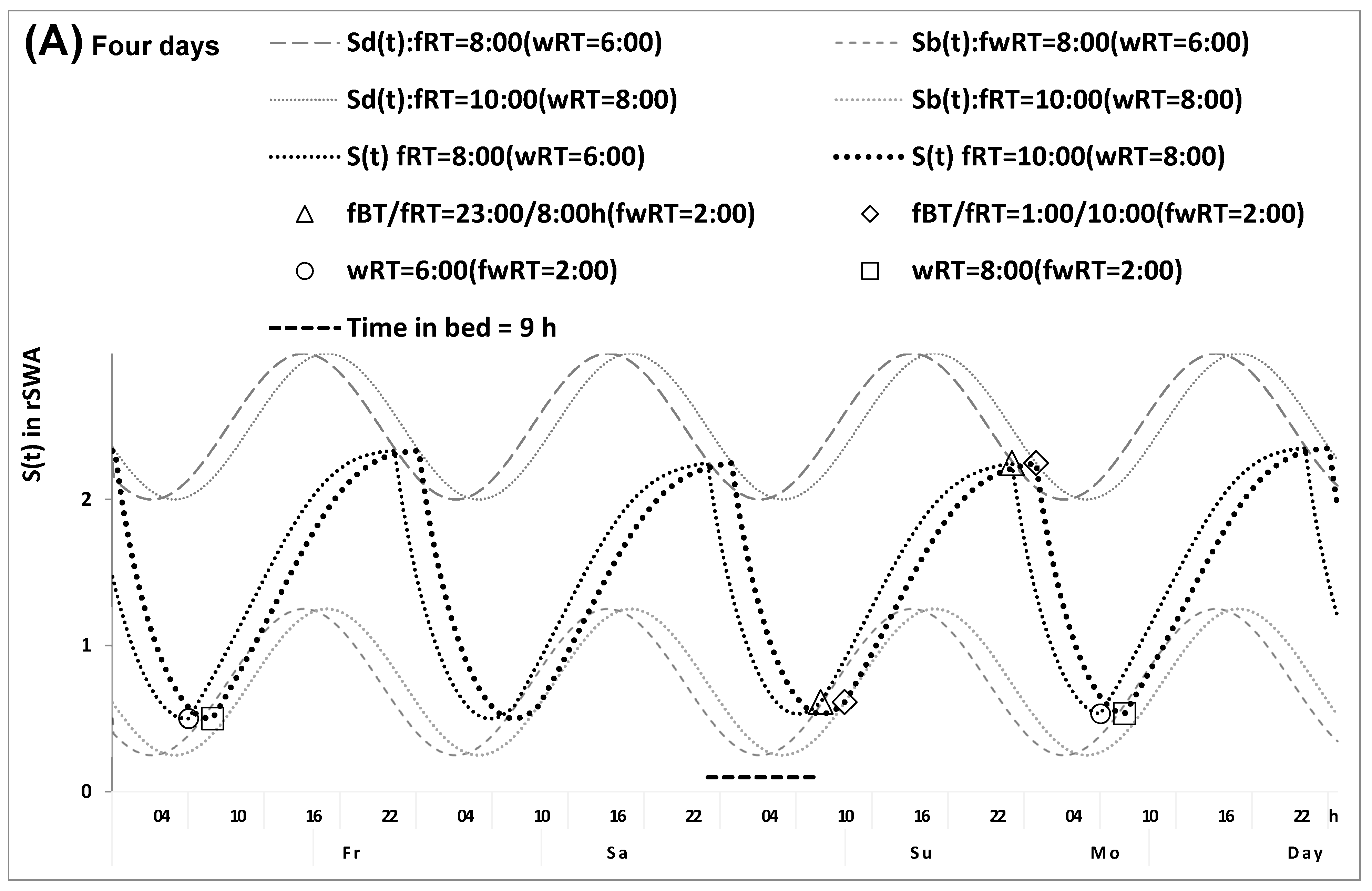

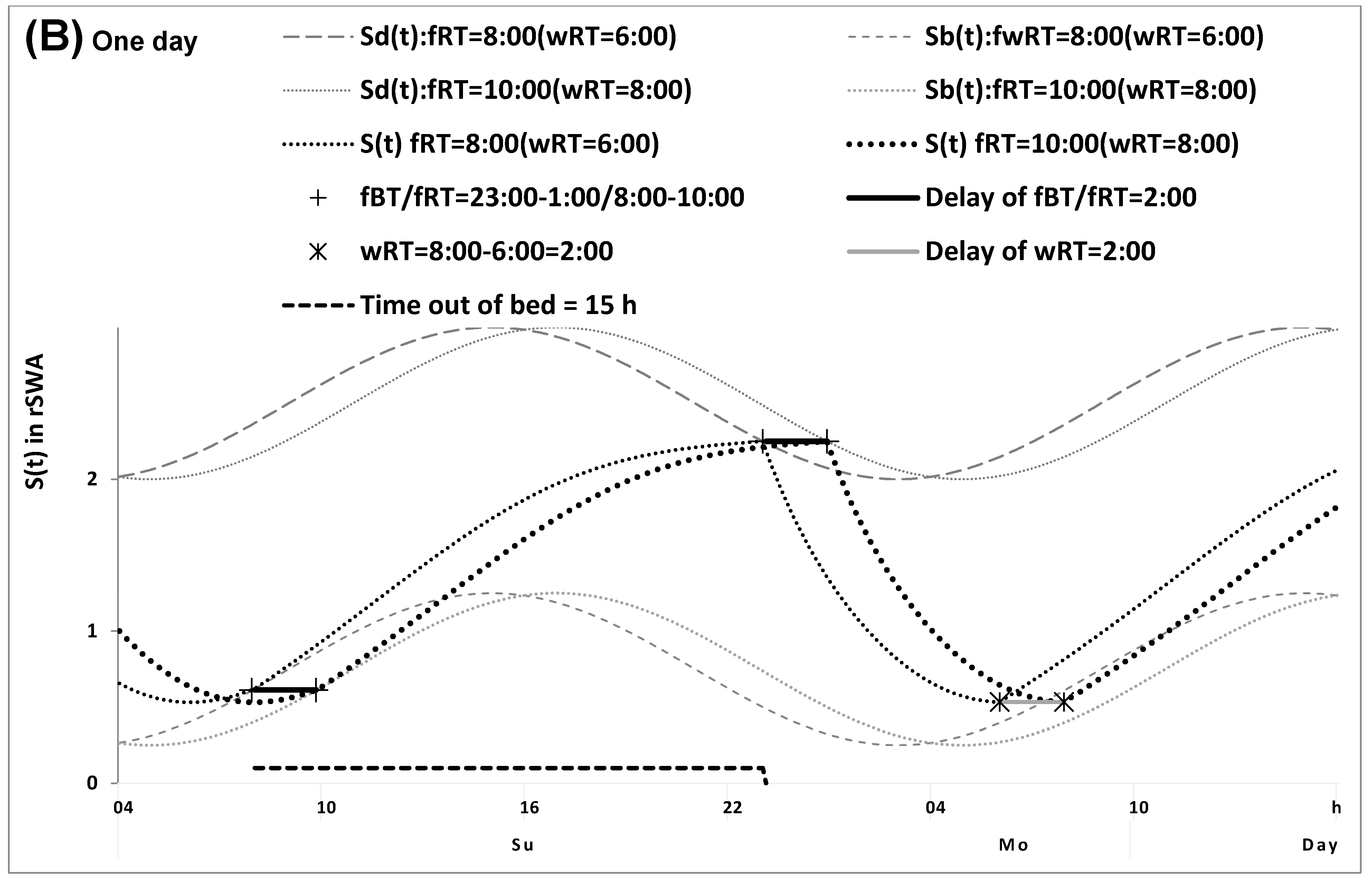

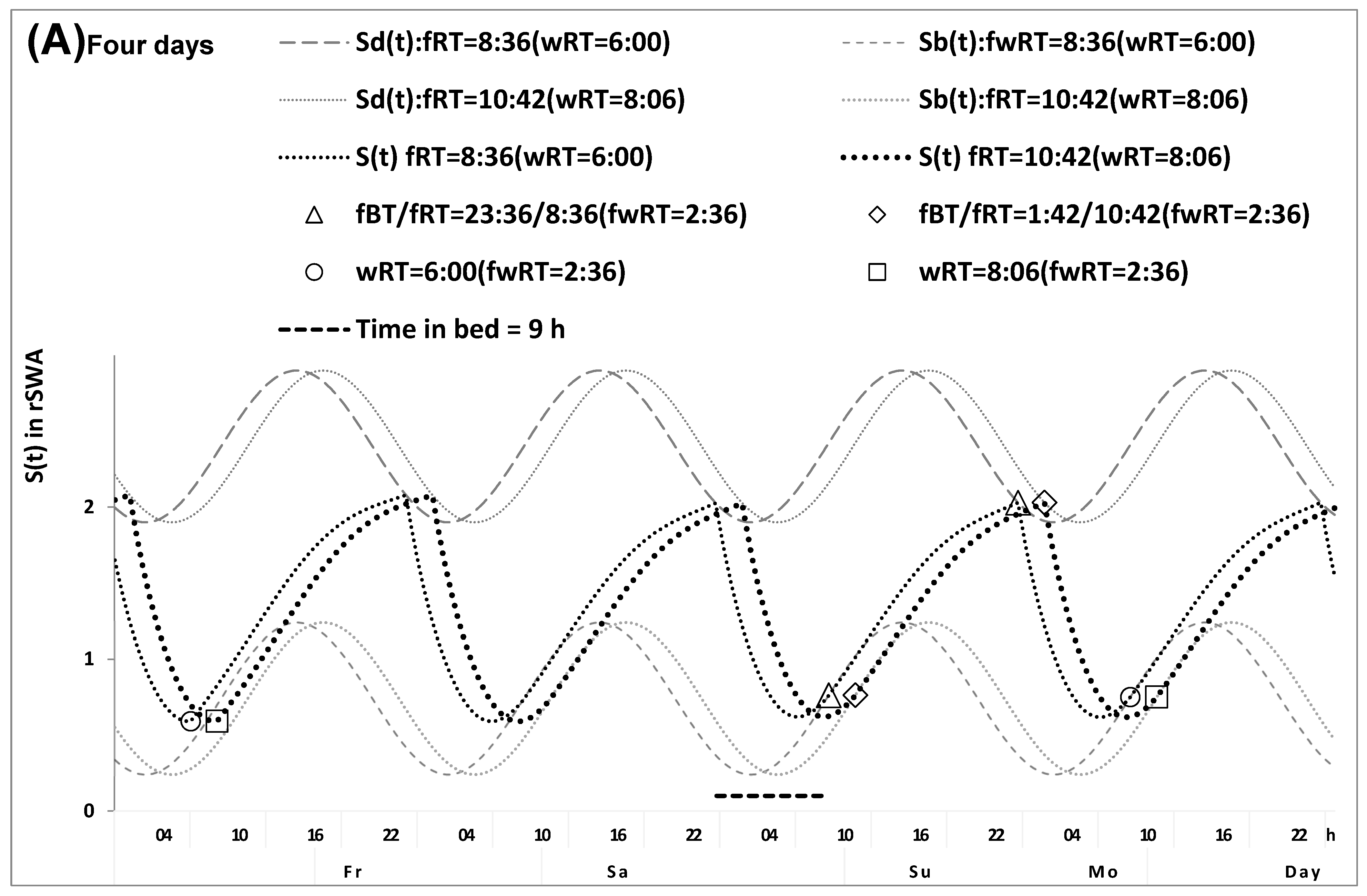

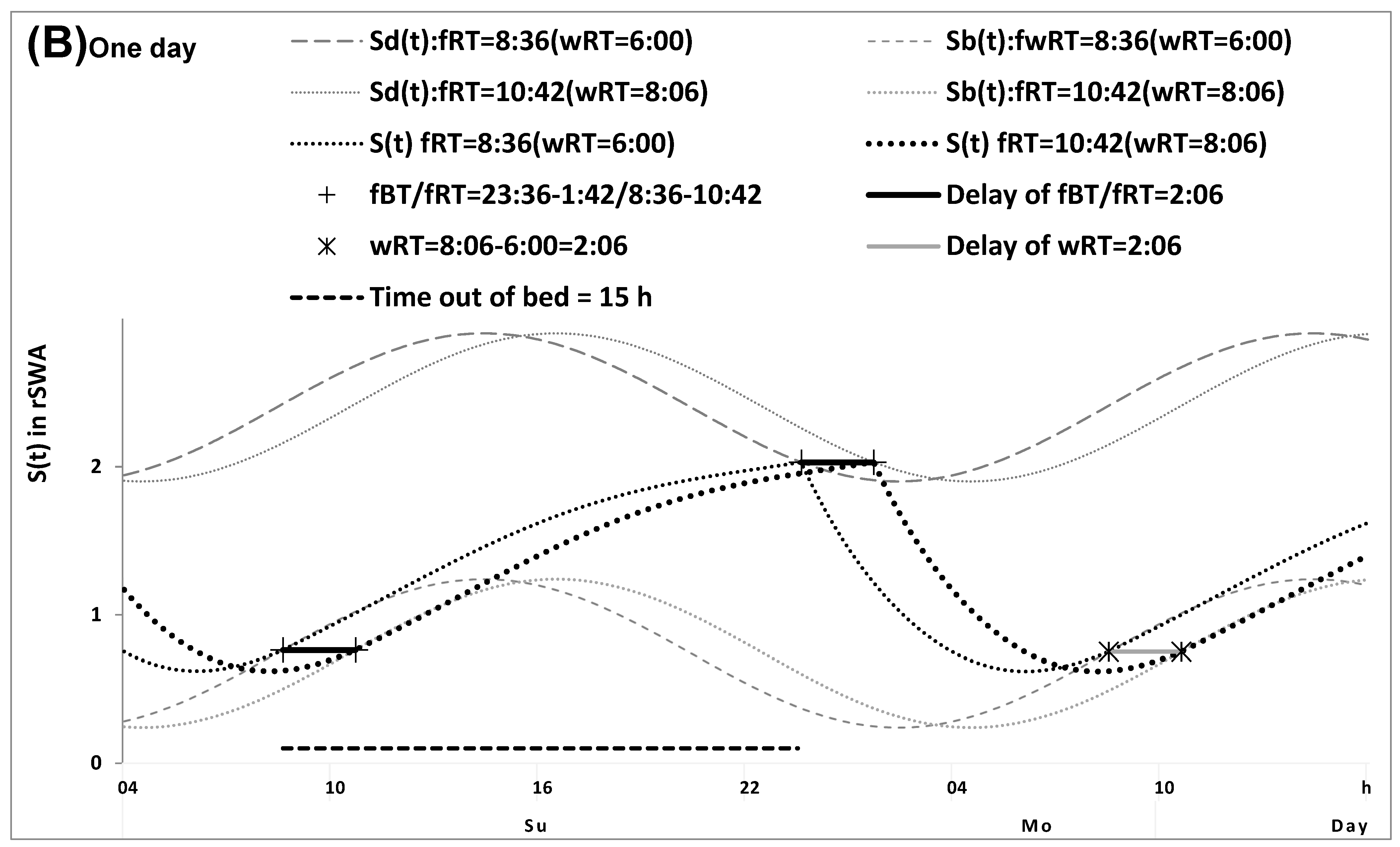

2.1. Results of the In Silico Study

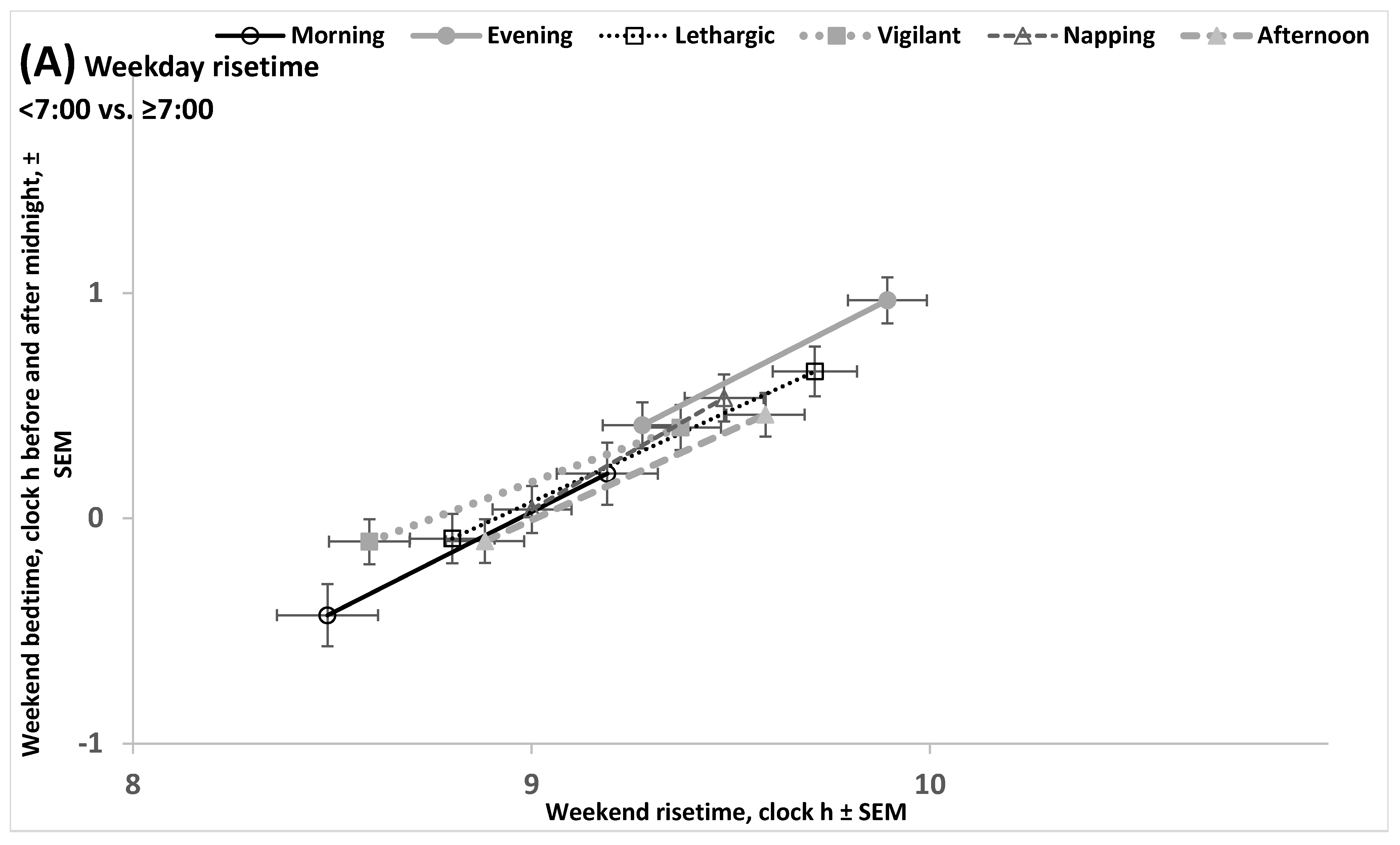

2.2. Results of the Empirical Study (Sleep Times, Sleepiness, Sleepability, and Wakeability in Various Chronotypes)

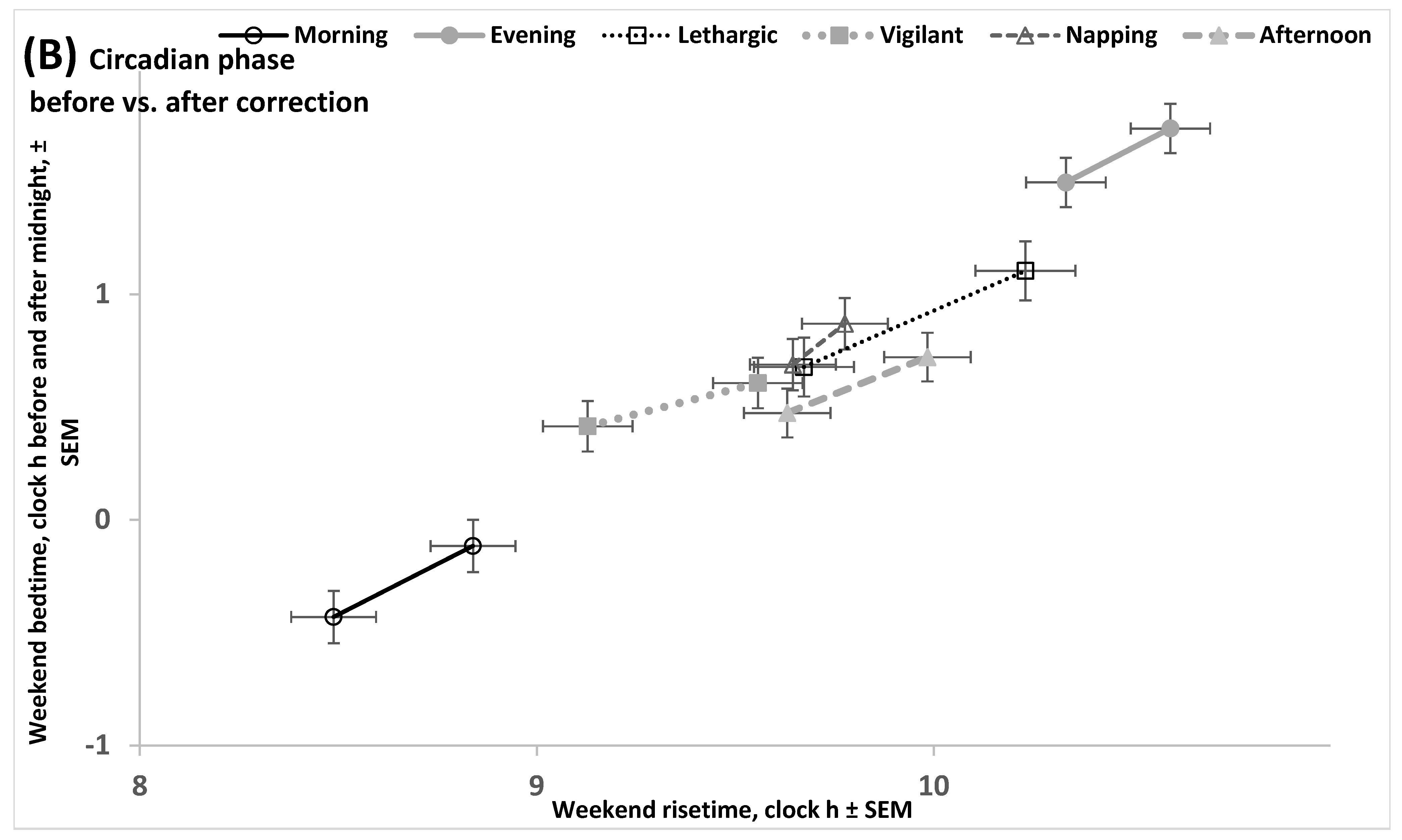

2.3. Results of the Empirical Study (Difference in Circadian Phase of Sleep Between Various Chronotypes)

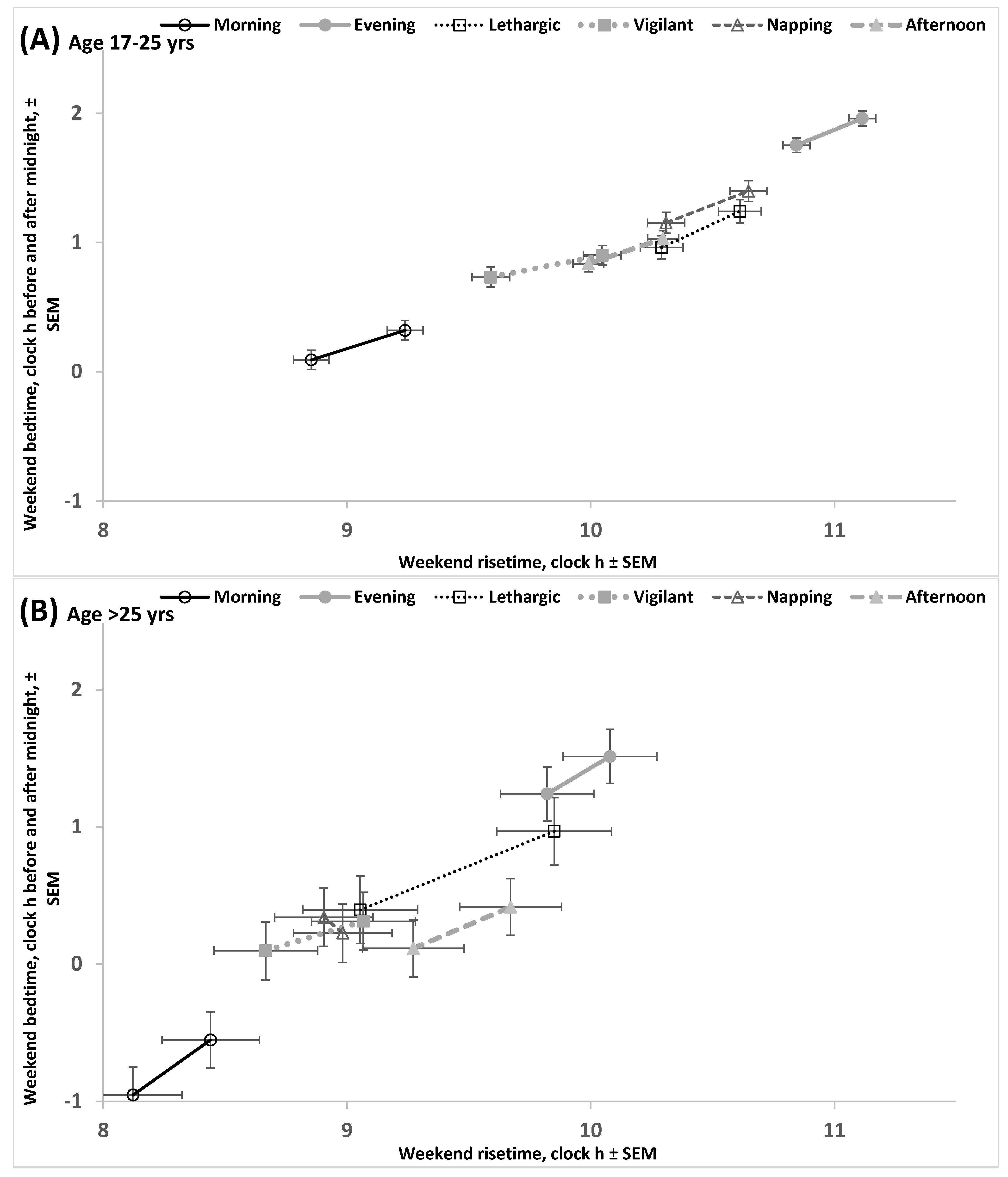

2.4. Results of the Empirical Study (Difference Between Ages in Rise- and Bedtimes)

2.5. Results of the Simulation Study

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Model-Based Computations (In Silico Study)

4.2. Survey Participants and Assessments of Chronotype (Empirical Study)

4.3. Details on Questionnaires for Assessment of Chronotype (Empirical Study)

4.4. Statistical Analysis (Empirical Study)

4.5. Model-Based Simulations (Simulation Study)

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Horne, J.A.; Ostberg, O. Individual differences in human circadian rhythms. Biol. Psychol. 1977, 5, 179–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adan, A. Chronotype and personality factors in the daily consumption of alcohol and psychostimulants. Addiction 1994, 89, 455–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duffy, J.F.; Dijk, D.J.; Hall, E.F.; Czeisler, C.A. Relationship of endogenous circadian melatonin and temperature rhythms to self-reported preference for morning or evening activity in young and older people. J. Investig. Med. 1999, 47, 141–150. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Duffy, J.F.; Rimmer, D.W.; Czeisler, C.A. Association of intrinsic circadian period with morningness-eveningness, usual wake time, and circadian phase. Behav. Neurosci. 2001, 115, 895–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerkhof, G.A. Inter-individual differences in the human circadian system: A review. Biol. Psychol. 1985, 20, 83–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adan, A.; Archer, S.N.; Hidalgo, M.P.; Di Milia, L.; Natale, V.; Randler, C. Circadian typology: A comprehensive review. Chronobiol. Int. 2012, 29, 1153–1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Milia, L.; Adan, A.; Natale, V.; Randler, C. Reviewing the psychometric properties of contemporary circadian typology measures. Chronobiol. Int. 2013, 30, 1261–1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levandovski, R.; Sasso, E.; Hidalgo, M.P. Chronotype: A review of the advances, limits and applicability of the main instruments used in the literature to assess human phenotype. Trends Psychiatry Psychother. 2013, 35, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carskadon, M.A.; Vieira, C.; Acebo, C. Association between puberty and delayed phase preference. Sleep 1993, 16, 258–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roenneberg, T.; Wirz-Justice, A.; Merrow, M. Life between clocks: Daily temporal patterns of human chronotypes. J. Biol. Rhythm. 2003, 18, 80–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monk, T.H.; Buysse, D.J.; Kennedy, K.S.; Potts, J.M.; DeGrazia, J.M.; Miewald, J.M. Measuring sleep habits without using a diary: The sleep timing questionnaire. Sleep 2003, 26, 208–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werner, H.; Lebourgeois, M.K.; Geiger, A.; Jenni, O.G. Assessment of chronotype in four- to eleven-year-old children: Reliability and validity of the Children’s Chronotype Questionnaire (CCTQ). Chronobiol. Int. 2009, 26, 992–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horne, J.A.; Ostberg, O. A self-assessment questionnaire to determine morningness-eveningness in human circadian rhythms. Int. J. Chronobiol. 1976, 4, 97–110. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, C.S.; Reilly, C.; Midkiff, K. Evaluation of three circadian rhythm questionnaires with suggestions for an improved measure of morningness. J. Appl. Psychol. 1989, 74, 728–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adan, A.; Almirall, H. Horne & Östberg morningness-eveningness questionnaire: A reduced scale. Pers. Individ. Differ. 1991, 12, 241–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baehr, E.K.; Revelle, W.; Eastman, C.I. Individual differences in the phase and amplitude of the human circadian temperature rhythm: With an emphasis on morningness-eveningness. J. Sleep Res. 2000, 9, 117–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerkhof, G.A.; van Dongen, H.P.A. Morning-type and evening-type individuals differ in the phase position of their endogenous circadian oscillator. Neurosci. Lett. 1996, 218, 153–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lack, L.; Bailey, M.; Lovato, N.; Wright, H. Chronotype differences in circadian rhythms of temperature, melatonin, and sleepiness as measured in a modified constant routine protocol. Nat. Sci. Sleep 2009, 1, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emens, J.S.; Yuhas, K.; Rough, J.; Kochar, N.; Peters, D.; Lewy, A.J. Phase angle of entrainment in morning- and evening-types under naturalistic conditions. Chronobiol. Int. 2009, 26, 474–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paine, S.J.; Gander, P.H. Differences in circadian phase and weekday/weekend sleep patterns in a sample of middle-aged morning types and evening types. Chronobiol. Int. 2016, 33, 1009–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nováková, M.; Sládek, M.; Sumová, A. Human chronotype is determined in bodily cells under real-life conditions. Chronobiol. Int. 2013, 30, 607–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrante, A.; Gellerman, D.; Ay, A.; Woods, K.P.; Filipowicz, A.M.; Jain, K.; Bearden, N.; Ingram, K.K. Diurnal Preference Predicts Phase Differences in Expression of Human Peripheral Circadian Clock Genes. J. Circadian Rhythm. 2015, 13, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wittenbrink, N.; Ananthasubramaniam, B.; Münch, M.; Koller, B.; Maier, B.; Weschke, C.; Bes, F.; de Zeeuw, J.; Nowozin, C.; Wahnschaffe, A.; et al. High-accuracy determination of internal circadian time from a single blood sample. J. Clin. Investig. 2018, 128, 3826–3839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maier, B.; Pilz Luísa, K.; Özcakir, S.; Rahjouei, A.; Abdo, A.N.; de Zeeuw, J.; Kunz, D.; Kramer, A. Hair test reveals plasticity of human chronotype. bioRxiv 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kantermann, T.; Sung, H.; Burgess, H.J. Comparing the Morningness-Eveningness Questionnaire and Munich ChronoType Questionnaire to the Dim Light Melatonin Onset. J. Biol. Rhythm. 2015, 30, 449–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reiter, A.M.; Sargent, C.; Roach, G.D. Concordance of Chronotype Categorisations Based on Dim Light Melatonin Onset, the Morningness-Eveningness Questionnaire, and the Munich Chronotype Questionnaire. Clocks Sleep 2021, 3, 342–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daan, S.; Beersma, D.G.M.; Borbély, A.A. Timing of human sleep: Recovery process gated by a circadian pacemaker. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 1984, 246, R161–R183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putilov, A.A. Reaction of the endogenous regulatory mechanisms to early weekday wakeups: A review of its popular explanations in light of model-based simulations. Front. Netw. Physiol. 2023, 3, 1285658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Putilov, A.A.; Verevkin, E.G. Can the Sun Prevent Weekend Sleep Advance After Early Weekday Wakeups? Nat. Sci. Sleep 2025, 17, 1895–1913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crowley, S.J.; Carskadon, M.A. Modifications to weekend recovery sleep delay circadian phase in older adolescents. Chronobiol. Int. 2010, 27, 1469–1492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broussard, J.L.; Wroblewski, K.; Kilkus, J.M.; Tasali, E. Two nights of recovery sleep reverses the effects of short-term sleep restriction on diabetes risk. Diabetes Care 2016, 39, e40–e41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gombert, M.; Reisdorph, N.; Morton, S.J.; Wright, K.P., Jr.; Depner, C.M. Insufficient sleep and weekend recovery sleep: Classification by a metabolomics-based machine learning ensemble. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 21123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Astill, R.G.; Verhoeven, D.; Vijzelaar, R.L.; Van Someren, E.J. Chronic stress undermines the compensatory sleep efficiency increase in response to sleep restriction in adolescents. J. Sleep Res. 2013, 22, 373–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Zhang, Y.; Huang, M.; Ma, Z.; Wang, D.; Fan, F. Associations of weekend compensatory sleep and weekday sleep duration with psychotic-like experiences among Chinese adolescents. J. Affect. Disord. 2025, 372, 627–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chamorro, R.; Garrido-González, M.; Gutierrez, M.; Santos, J.L.; Weisstaub, G. Sleep Restriction and Weekend Sleep Compensation Relate to Eating Behavior in School-Aged Children. Nat. Sci. Sleep 2025, 17, 1671–1681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leger, D.; Richard, J.B.; Collin, O.; Sauvet, F.; Faraut, B. Napping and weekend catchup sleep do not fully compensate for high rates of sleep debt and short sleep at a population level (in a representative nationwide sample of 12,637 adults). Sleep Med. 2020, 74, 278–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonetti, L.; Andreose, A.; Bacaro, V.; Grimaldi, M.; Natale, V.; Crocetti, E. Different Effects of Social Jetlag and Weekend Catch-Up Sleep on Well-Being of Adolescents According to the Actual Sleep Duration. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 20, 574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsiao, F.C.; Huang, Y.H.; Yang, C.M. The sleep paradox: The effect of weekend catch-up sleep on homeostasis and circadian misalignment. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2025, 175, 106231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Milia, L.; Folkard, S. More Than Morningness: The Effect of Circadian Rhythm Amplitude and Stability on Resilience, Coping, and Sleep Duration. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 782349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorgol, J.; Randler, C.; Stolarski, M.; Kalb, N. Beyond larks and owls: Revisiting the circadian typology using the MESSi scale and a cluster-based approach. J. Sleep Res. 2024, 34, e14403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Easton, D.; Gupta, C.; Vincent, G.; Vandelanotte, C.; Duncan, M.; Tucker, P.; Di Milia, L.; Ferguson, S.A. The relationship between circadian type and physical activity as predictors of cognitive performance during simulated nightshifts: A randomised controlled trial. Chronobiol. Int. 2025, 42, 736–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putilov, A.A.; Sveshnikov, D.S.; Puchkova, A.N.; Dorokhov, V.B.; Bakaeva, Z.B.; Yakunina, E.B.; Starshinov, Y.P.; Torshin, V.I.; Alipov, N.N.; Sergeeva, O.V.; et al. Single-Item Chronotyping (SIC), a method to self-assess diurnal types by using 6 simple charts. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2021, 168, 110353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuper, S. Overthrowing the Tyranny of the Early Birds with New Sleep Rules that Give Workers More Shuteye. Financial Post, 2 November 2021. Available online: https://financialpost.com/fp-work/overthrowing-the-tyranny-of-the-early-birds-with-new-sleep-rules-that-give-workers-more-shuteye (accessed on 26 November 2024).

- Putilov, A.A.; Verevkin, E.G.; Sveshnikov, D.S.; Bakaeva, Z.V.; Yakunina, E.B.; Mankaeva, O.V.; Torshin, V.I.; Trutneva, E.A.; Lapkin, M.M.; Lopatskaya, Z.N.; et al. Estimation of sleep shortening and sleep phase advancing in response to advancing risetimes on weekdays. Chronobiol. Int. 2025, 42, 770–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, M.R.; Eastman, C.I. Shift work: Health, performance and safety problems, traditional countermeasures, and innovative management strategies to reduce circadian misalignment. Nat. Sci. Sleep 2012, 4, 111–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misiunaite, I.; Eastman, C.I.; Crowley, S.J. Circadian Phase Advances in Response to Weekend Morning Light in Adolescents with Short Sleep and Late Bedtimes on School Nights. Front. Neurosci. 2020, 14, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crowley, S.J.; Velez, S.L.; Killen, L.G.; Cvengros, J.A.; Fogg, L.F.; Eastman, C.I. Extending weeknight sleep of delayed adolescents using weekend morning bright light and evening time management. Sleep 2023, 46, zsac202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putilov, A.A. Timing of sleep modelling: Circadian modulation of the homeostatic process. Biol. Rhythm. Res. 1995, 26, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Åkerstedt, T.; Gillberg, M. The circadian variation of experimentally displaced sleep. Sleep 1981, 4, 159–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dijk, D.-J.; Beersma, D.G.M.; Daan, S. EEG power density during nap sleep: Reflection of an hourglass measuring the duration of prior wakefulness. J. Biol. Rhythm. 1987, 2, 207–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dijk, D.-J.; Brunner, D.P.; Borbély, A.A. Time course of EEG power density during long sleep in humans. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 1990, 258, R650–R661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dijk, D.-J.; Brunner, D.P.; Borbély, A.A. EEG power density during recovery sleep in the morning. Electroencephalogr. Clin. Neurophysiol. 1991, 78, 203–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marcoen, N.; Vandekerckhove, M.; Neu, D.; Pattyn, N.; Mairesse, O. Individual differences in subjective circadian flexibility. Chronobiol. Int. 2015, 32, 1246–1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Putilov, A.A. Three-dimensional structural representation of the sleep-wake adaptability. Chronobiol. Int. 2016, 33, 169–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Putilov, A.A.; Sveshnikov, D.S.; Bakaeva, Z.B.; Yakunina, E.B.; Starshinov, Y.P.; Torshin, V.I.; Alipov, N.N.; Sergeeva, O.V.; Trutneva, E.A.; Lapkin, M.M.; et al. Differences between male and female university students in sleepiness, weekday sleep loss, and weekend sleep duration. J. Adolesc. 2021, 88, 84–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Weekend-Weekday Gap in Risetime, h | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 2 − 4 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sleep times | Time in bed | From Tuesday to Wednesday (wTiB) | 6.75 | 7.20 | 7.70 | 8.29 | 0.95 | |

| calculated | From Sunday to Monday(fRT) | 5.00 | 6.00 | 7.00 | 8.00 | 2.00 | ||

| for two | Risetime | Wednesday (with respect to) | 5.00 | 6.00 | 7.00 | 8.00 | 2.00 | |

| days of | Sunday (fRT) | 8.97 | 8.98 | 8.99 | 9.00 | 0.02 | ||

| the week | Bedtime | Wednesday (wBT) | 22.05 | 22.72 | 23.28 | 23.71 | 1.23 | |

| Sunday (fBT) | 24.00 | 24.00 | 24.00 | 24.00 | 0.00 | |||

| Parameters | Circadian | Circadian phase, clock h | φmax | 16.00 | 16.00 | 16.00 | 16.00 | 0.00 |

| of the | parameters | Circadian amplitude, rSWA | A | 0.50 | 0.50 | 0.50 | 0.50 | 0.00 |

| model | (2) | Circadian period, h | τ | 24.00 | 24.00 | 24.00 | 24.00 | 0.00 |

| (1a, 1b, 2) | Homeostatic | Highest buildup, rSWA | Sd | 2.50 | 2.50 | 2.50 | 2.50 | 0.00 |

| parameters | Lowest decay, rSWA | Sb | 0.75 | 0.75 | 0.75 | 0.75 | 0.00 | |

| (1a, 1b) | Upper asymptote, rSWA | Su | 4.51 | 4.51 | 4.51 | 4.51 | 0.00 | |

| Lower asymptote, rSWA | Sl | 0.70 | 0.70 | 0.70 | 0.70 | 0.00 | ||

| Time constant for buildup, h | Tb | 24.75 | 24.75 | 24.75 | 24.75 | 0.00 | ||

| Time constant for decay, h | Td | 2.30 | 2.30 | 2.30 | 2.30 | 0.00 | ||

| Twofold circadian impact | k | 2.00 | 2.00 | 2.00 | 2.00 | 0.00 | ||

| Type | Morning | Evening | Lethargic | Vigilant | Napping | Afternoon |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type | Difference in time in bed on weekends | |||||

| Morning | - | −0.08 | −0.30 | 0.14 | −0.20 | −0.25 |

| Evening | 0.94 *** | - | −0.22 | 0.22 | −0.12 | −0.17 |

| Lethargic | 0.42 *** | −0.52 *** | - | 0.44 ** | 0.09 | 0.05 |

| Vigilant | 0.33 * | −0.61 *** | −0.09 | - | −0.34 * | −0.39 ** |

| Napping | 0.76 *** | −0.19 | 0.33 * | 0.42 ** | - | −0.05 |

| Afternoon | 0.34 ** | −0.61 *** | −0.09 | 0.00 | −0.42 *** | - |

| Difference in time in bed on weekdays | ||||||

| Difference in weekend–weekday gap in risetime | ||||||

| Morning | −1.02 *** | −0.72 *** | −0.20 | −0.96 *** | −0.58 *** | |

| Evening | −1.22 *** | 0.30 | 0.83 *** | 0.06 | 0.44 *** | |

| Lethargic | −0.89 *** | 0.33 ** | 0.53 ** | −0.24 | 0.14 | |

| Vigilant | −0.24 | 0.98 *** | 0.65 *** | −0.77 *** | −0.39 * | |

| Napping | −0.93 *** | 0.29 ** | −0.03 | −0.68 *** | 0.38 * | |

| Afternoon | −0.72 *** | 0.51 *** | 0.18 | −0.47 *** | 0.21 | |

| Difference in weekend–weekday gap in time in bed | ||||||

| Another Type | Evening | Lethargic | Vigilant | Napping | Afternoon | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Difference between Another and Morning type (uncorrected for risetime) | ||||||

| Risetime | ΔfRT | 1.49 *** | 0.83 *** | 0.29 | 0.81 *** | 0.79 *** |

| Bedtime | ΔfBT | 1.61 *** | 0.80 *** | 0.53 ** | 0.81 *** | 0.59 *** |

| Difference between later and earlier weekday risers, ≥ 7 minus < 7 | ||||||

| Risetime | ΔfRT | 0.62 *** | 0.91 *** | 0.78 *** | 0.48 ** | 0.70 *** |

| Bedtime | ΔfBT | 0.56 *** | 0.74 *** | 0.51 ** | 0.50 ** | 0.56 *** |

| Difference between Another ≥ 7 and Morning < 7 (corrected for risetime) | ||||||

| Weekend | ΔfRT | 2.11 *** | 1.74 *** | 1.07 *** | 1.29 *** | 1.50 *** |

| Weekend | ΔfBT | 2.17 *** | 1.54 *** | 1.04 *** | 1.30 *** | 1.15 *** |

| Type | Morning | Evening | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Simulated | Time | Weekday | wTiB | 6.88 | 6.96 |

| sleep | in | Weekend | fTiB | 8.92 | 8.88 |

| time, h | bed | Gap | fwTiB | 2.04 | 1.92 |

| or clock h | Rise- | Weekday | RT | 5.99 | 8.10 |

| time | Weekend | fRT | 8.49 | 10.61 | |

| Gap | fwRT | 2.50 | 2.51 | ||

| Bed- | Weekday | wBT | 23.11 | 25.14 | |

| time | Weekend | fBT | 23.57 | 25.73 | |

| Gap | fwBT | 0.46 | 0.59 | ||

| Difference | Time | Weekday | wTiB | 0.07 | −0.14 |

| between | in | Weekend | fTiB | −0.06 | 0.01 |

| reported | bed | Gap | fwTiB | −0.01 | −0.01 |

| and | Rise- | Weekday | RT | −0.02 | −0.02 |

| simulated | time | Weekend | fRT | −0.08 | 0.10 |

| sleep | Gap | fwRT | 0.04 | −0.05 | |

| time, h | Bed- | Weekday | wBT | 0.12 | −0.15 |

| time | Weekend | fBT | −0.13 | 0.14 | |

| Gap | fwBT | −0.01 | −0.01 | ||

| Parameters | Circadian | Circadian phase, clock h | φmax | 14.40 | 16.50 |

| of the | parameters | Circadian amplitude, rSWA | A | 0.50 | 0.50 |

| model | (2) | Circadian period, h | τ | 24.00 | 24.00 |

| (1a, 1b, 2) | Homeostatic | Highest buildup, rSWA | Sd | 2.40 | 2.40 |

| parameters | Lowest decay, rSWA | Sb | 0.74 | 0.74 | |

| (1a, 1b) | Upper asymptote, rSWA | Su | 5.20 | 5.20 | |

| Lower asymptote, rSWA | Sl | 0.70 | 0.70 | ||

| Time constant for buildup, h | Tb | 39.40 | 39.40 | ||

| Time constant for decay, h | Td | 2.57 | 2.57 | ||

| Twofold circadian impact | k | 2.00 | 2.00 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Putilov, A.A.; Verevkin, E.G.; Sveshnikov, D.S.; Bakaeva, Z.V.; Yakunina, E.B.; Mankaeva, O.V.; Torshin, V.I.; Trutneva, E.A.; Lapkin, M.M.; Lopatskaya, Z.N.; et al. Estimation of the Circadian Phase Difference in Weekend Sleep and Further Evidence for Our Failure to Sleep More on Weekends to Catch Up on Lost Sleep. Clocks & Sleep 2025, 7, 67. https://doi.org/10.3390/clockssleep7040067

Putilov AA, Verevkin EG, Sveshnikov DS, Bakaeva ZV, Yakunina EB, Mankaeva OV, Torshin VI, Trutneva EA, Lapkin MM, Lopatskaya ZN, et al. Estimation of the Circadian Phase Difference in Weekend Sleep and Further Evidence for Our Failure to Sleep More on Weekends to Catch Up on Lost Sleep. Clocks & Sleep. 2025; 7(4):67. https://doi.org/10.3390/clockssleep7040067

Chicago/Turabian StylePutilov, Arcady A., Evgeniy G. Verevkin, Dmitry S. Sveshnikov, Zarina V. Bakaeva, Elena B. Yakunina, Olga V. Mankaeva, Vladimir I. Torshin, Elena A. Trutneva, Michael M. Lapkin, Zhanna N. Lopatskaya, and et al. 2025. "Estimation of the Circadian Phase Difference in Weekend Sleep and Further Evidence for Our Failure to Sleep More on Weekends to Catch Up on Lost Sleep" Clocks & Sleep 7, no. 4: 67. https://doi.org/10.3390/clockssleep7040067

APA StylePutilov, A. A., Verevkin, E. G., Sveshnikov, D. S., Bakaeva, Z. V., Yakunina, E. B., Mankaeva, O. V., Torshin, V. I., Trutneva, E. A., Lapkin, M. M., Lopatskaya, Z. N., Budkevich, R. O., Budkevich, E. V., Dyakovich, M. P., Donskaya, O. G., Shumov, D. E., Ligun, N. V., Puchkova, A. N., & Dorokhov, V. B. (2025). Estimation of the Circadian Phase Difference in Weekend Sleep and Further Evidence for Our Failure to Sleep More on Weekends to Catch Up on Lost Sleep. Clocks & Sleep, 7(4), 67. https://doi.org/10.3390/clockssleep7040067