Comparison of Tailored Versus Standard Group Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Shift Worker Insomnia: A Randomized Controlled Trial

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

- Does implicit treatment within this unique approach significantly improve the sleep of shift workers? A review of the extant literature suggests that this approach has not yet been investigated. The present study hypothesizes that a positive manipulation of mood, anxiety, worry/concern, rumination, and problem solving will result in a positive effect on sleep.

- (2)

- Do the explicitly manipulated factors also improve? As they are secondary outcomes, significant improvements in the aforementioned state- and trait-related factors, as well as attitudes and beliefs, are expected as a result of the therapeutic intervention.

- (3)

- Are these improvements stable over a three-month period? It is anticipated that the positive effects will maintain their stability over the course of the follow-up period for all examined characteristics.

- (4)

- How does the efficacy of the new treatment (CBT-I-S) compare to standard CBT-I in a sample of shift workers? The innovative approach of the implicit treatment of sleep warrants an exploratory investigation, which also examines the possibility of inferiority. By comprehensively considering the needs of shift workers and directing the focus of attention away from sleep, superiority over standard therapy would be a desirable result. Given the absence of prior research in this domain, the achievement of equivalent efficacy would be a commendable outcome, providing a solid foundation for future research.

2. Results

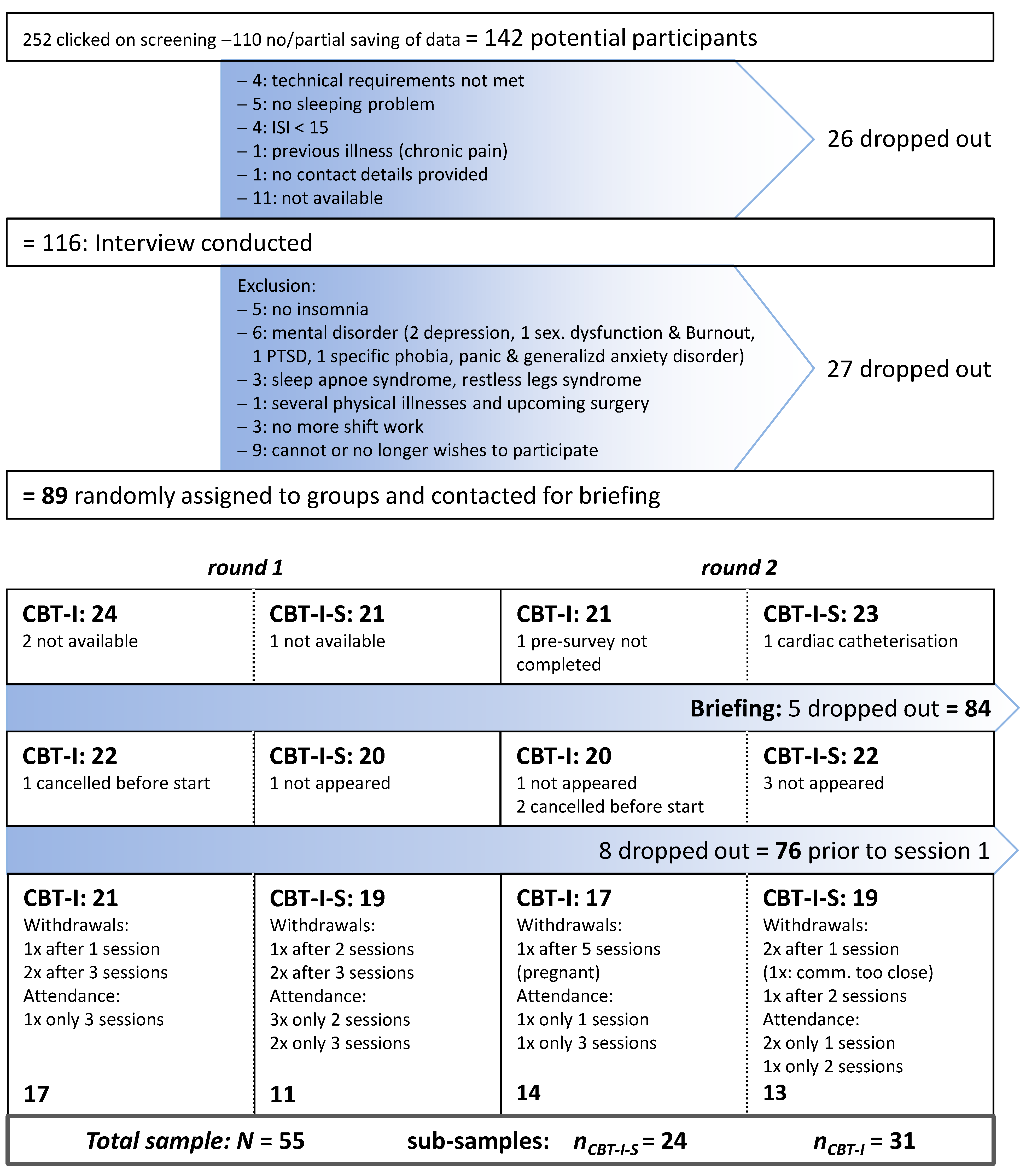

2.1. Flow of Participants and Attrition

2.2. Recruitment

2.3. Sample Characteristics: Baseline Data

2.4. Pre-Treatment Improvement

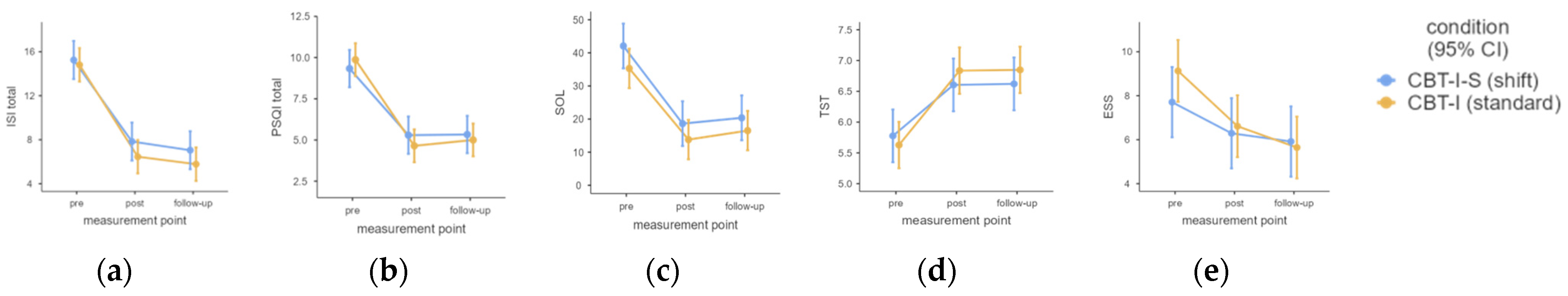

2.5. Primary Outcomes

2.6. Secondary Outcomes

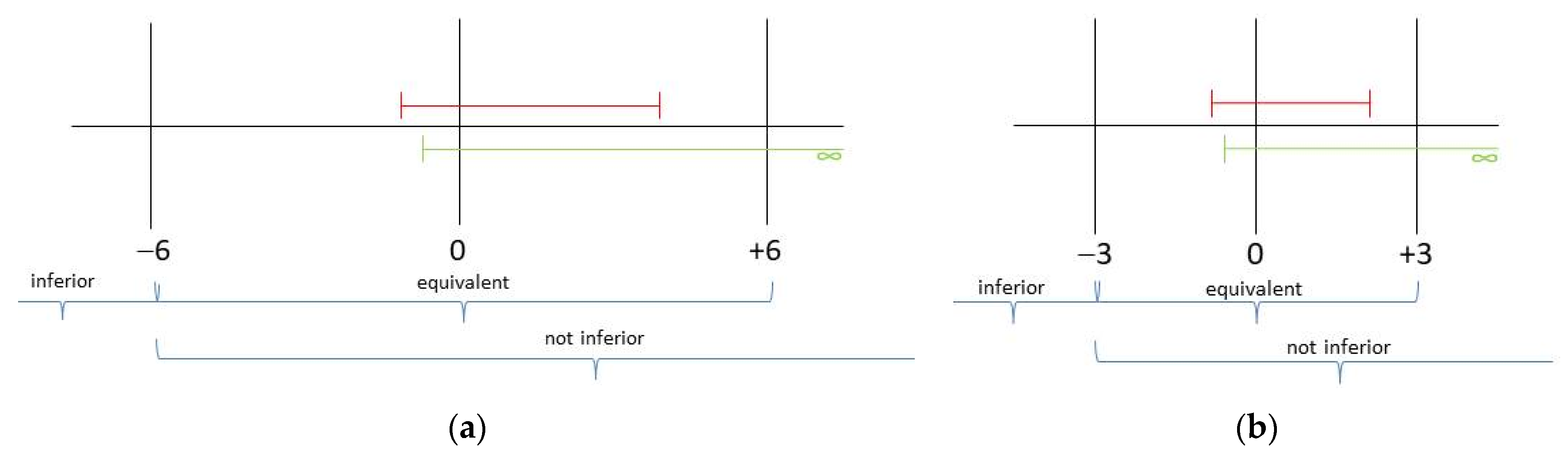

2.7. Non-Inferiority/Equivalence Tests

2.8. Number Needed to Treat (NNT)

2.9. Perceived Effectiveness

2.10. Treatment Integrity

3. Discussion

3.1. Limitations

3.2. Strengths

4. Methods and Materials

4.1. Trial Design

4.2. Participants

4.3. Setting and Conditions of Implementation

4.4. Treatment Manuals

4.4.1. CBT-I: Standard Manual

4.4.2. CBT-I-S: Shift-Specific Manual

4.5. Outcome Variables, Measurement Points, and Instruments

| Content/Outcome Variable | T0: Screening | Interview | T1: Pre | T2: Post | T3: Follow-Up | Instrument/Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Screening and interview: inclusion/exclusion criteria | ||||||

| Age, sufficient German language skills, technical requirements, previous illnesses, insomnia (for ≥3 months, ≥3×/week; ISI ≥ 15), weekly working hours ≥ 30, shift work, contact details | × | In-house developed items; ISI (Insomnia Severity Index) [47] | ||||

| Screening for mental disorders | × | Mini-DIPS (Diagnostisches Interview psychischer Störungen) [48] | ||||

| Insomnia, no other sleep disordersuch as restless legs syndrome, sleep apnea syndrome | × | SIS-D-5: diagnostic interview, in-house development based onSIS-III-R [49]; DSM-5 [50]; SCID-5-CV [51]. | ||||

| Attitude towards shift work | × | Own item: “Do you like working shifts? Yes, I don’t mind/No, but I have to” | ||||

| Chronotype | × | rCSM (Reduced Composite Scale of Morningness) [52] | ||||

| Demographics | ||||||

| Age, gender, federal state, marital status, years of shift work, profession, shift system | × | In-house developed items | ||||

| Sleep variables | ||||||

| Sleep quality (PSQI total); “subjective sleep quality” (SSQ, comp. 1); sleep-onset latency (SOL, item 2); total sleep time (TST, item 4); sleep efficiency (comp. 4) | × | × | × | PSQI (Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index) [53] | ||

| Insomnia severity (Screening: ≥15) | × | × | × | × | ISI (Insomnia Severity Index) [47] | |

| Daytime sleepiness | × | × | × | ESS (Epworth Sleepiness Scale) [54] | ||

| Dysfunctional beliefs about sleep | × | × | × | MZS (Meinungen zum Schlaf Fragebogen) [55] | ||

| Importance of sleep (categorical item 1–5) | × | × | × | Own item: “How important is your sleep to you?” | ||

| Cognitive and somatic arousal before sleep | × | × | × | PSAS (Pre-Sleep Arousal Scale) [56] | ||

| Sleep hygiene | × | × | × | SHI (Sleep Hygiene Index) [57], own translation | ||

| Psychological and personality factors | ||||||

| Anxiety, depression, mental well-being | × | × | × | HADS-D (Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale) [58] | ||

| Emotional stability (C), tension (Q4), concern (O) | × | × | × | 16 PF-R (16 Personality Factor Test, revised version), [59] | ||

| Feedback on therapy: categorical item 1–5; open feedback | × | “Please rate how helpful the training was for you overall:” | ||||

4.6. Power

4.7. Randomization and Blinding

4.8. Statistical Analyses

4.9. Planned Verification of Treatment Integrity

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| SWD | Shift work disorder |

| CBT-I | Cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia |

| CBT-I-S | Cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia in shift workers |

| TST | Total sleep time |

| SOL | Sleep onset latency |

| SSQ | Subjective sleep quality |

| DS | Daytime sleepiness |

| ISI | Insomnia severity index |

| PSQI | Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index |

| ESS | Epworth Sleepiness Scale |

| MZS | Meinungen-zum-Schlaf-Fragebogen (dysfunctional beliefs about sleep) |

| PSAS | Pre-sleep arousal scale |

| SHI | Sleep hygiene index |

| HADS-D | Hospital anxiety and depression scale |

| 16 PF-R | 16-personality traits, revised edition |

| MCID | Minimal clinically important difference |

| ARR | Absolute risk reduction |

| NNT | Number needed to treat |

References

- Pallesen, S.; Bjorvatn, B.; Waage, S.; Harris, A.; Sagoe, D. Prevalence of Shift Work Disorder: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 638252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grünberger, T.; Höhn, C.; Schabus, M.; Laireiter, A.-R. Insomnia in Shift Workers: Which trait and state characteristics could serve as foundation for developing an innovative therapeutic approach? Preprints 2024, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ell, J.; Brückner, H.A.; Johann, A.F.; Steinmetz, L.; Güth, L.J.; Feige, B.; Järnefelt, H.; Vallières, A.; Frase, L.; Domschke, K.; et al. Digital cognitive behavioural therapy for insomnia reduces insomnia in nurses suffering from shift work disorder: A randomised-controlled pilot trial. J. Sleep Res. 2024, 33, e14193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, A.C.; Sweetman, A.; Crowther, M.E.; Paterson, J.L.; Scott, H.; Lechat, B.; Wanstall, S.E.; Brown, B.W.; Lovato, N.; Adams, R.J.; et al. Is cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia (CBTi) efficacious for treating insomnia symptoms in shift workers? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep Med. Rev. 2023, 67, 101716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bastille-Denis, E.; Lemyre, A.; Pappathomas, A.; Roy, M.; Vallières, A. Are cognitive variables that maintain insomnia also involved in shift work disorder? Sleep Health 2020, 6, 399–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallières, A.; Pappathomas, A.; Garnier, S.B.; Mérette, C.; Carrier, J.; Paquette, T.; Bastien, C.H. Behavioural therapy for shift work disorder improves shift workers’ sleep, sleepiness and mental health: A pilot randomised control trial. J. Sleep Res. 2024, 33, e14162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espie, C.A. Standard CBT-I protocol for the treatment of insomnia disorder. In Cognitive-Behavioural Therapy for Insomnia (CBT-I) Across the Life Span: Guidelines and Clinical Protocols for Health Professionals; Baglioni, C., Espie, C.A., Riemann, D., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons Ltd.: Oxford, UK, 2022; pp. 19–41. [Google Scholar]

- Tout, A.F.; Tang, N.K.Y.; Sletten, T.L.; Toro, C.T.; Kershaw, C.; Meyer, C.; Rajaratnam, S.M.W.; Moukhtarian, T.R. Current sleep interventions for shift workers: A mini review to shape a new preventative, multicomponent sleep management programme. Front. Sleep 2024, 3, 1343393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Järnefelt, H.; Spiegelhalder, K. CBT-I Protocols for Shift Workers and Health Operators. In Cognitive-Behavioural Therapy for Insomnia (CBT-I) Across the Life Span: Guidelines and Clinical Protocols for Health Professionals; Baglioni, C., Espie, C.A., Riemann, D., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons Ltd.: Oxford, UK, 2022; pp. 126–132. [Google Scholar]

- Kalkanis, A.; Demolder, S.; Papadopoulos, D.; Testelmans, D.; Buyse, B. Recovery from shift work. Front. Neurol. 2023, 14, 1270043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shriane, A.E.; Rigney, G.; Ferguson, S.A.; Bin, Y.S.; Vincent, G.E. Healthy sleep practices for shift workers: Consensus sleep hygiene guidelines using a Delphi methodology. Sleep 2023, 46, zsad182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Järnefelt, H.; Lagerstedt, R.; Kajaste, S.; Sallinen, M.; Savolainen, A.; Hublin, C. Cognitive behavioral therapy for shift workers with chronic insomnia. Sleep Med. 2012, 13, 1238–1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Järnefelt, H.; Härmä, M.; Sallinen, M.; Virkkala, J.; Paajanen, T.; Martimo, K.-P.; Hublin, C. Cognitive behavioural therapy interventions for insomnia among shift workers: RCT in an occupational health setting. Int. Arch. Occup. Environ. Health 2020, 93, 535–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Booker, L.A.; Sletten, T.L.; Barnes, M.; Alvaro, P.; Collins, A.; Chai-Coetzer, C.L.; McMahon, M.; Lockley, S.W.; Rajaratnam, S.M.W.; Howard, M.E. The effectiveness of an individualized sleep and shift work education and coaching program to manage shift work disorder in nurses: A randomized controlled trial. J. Clin. Sleep Med. 2022, 18, 1035–1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, E.H.; Hong, Y.; Kim, Y.; Lee, S.; Ahn, Y.; Jeong, K.S.; Jang, T.-W.; Lim, H.; Jung, E.; Shift Work Disorder Study Group; et al. The development of a sleep intervention for firefighters: The FIT-IN (Firefighter’s Therapy for Insomnia and Nightmares) Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 8738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takano, Y.; Ibata, R.; Machida, N.; Ubara, A.; Okajima, I. Effect of cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia in workers: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Sleep Med. Rev. 2023, 71, 101839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, A.G. A cognitive model of insomnia. Behav. Res. Ther. 2002, 40, 869–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espie, C.A.; Broomfield, N.M.; MacMahon, K.M.; Macphee, L.M.; Taylor, L.M. The attention-intention-effort pathway in the development of psychophysiologic insomnia: A theoretical review. Sleep Med. Rev. 2006, 10, 215–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benjamini, Y.; Hochberg, Y. Controlling the False Discovery Rate: A Practical and Powerful Approach to Multiple Testing. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B (Methodol.) 1995, 57, 289–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frank, J.D. Persuasion and Healing: A Comparative Study of Psychotherapy; John Hopkins University Press: Baltimore, MD, USA, 1961. [Google Scholar]

- Constantino, M.J.; Vîslă, A.; Coyne, A.E.; Boswell, J.F. A meta-analysis of the association between patients’ early treatment outcome expectation and their posttreatment outcomes. Psychotherapy 2018, 55, 473–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagano, R.R. Understanding Statistics in the Behavioral Sciences, 9th ed.; Thomson Wadsworth: Belmont, CA, Australia, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Rasch, D.; Guiard, V. The robustness of parametric statistical methods. Psychol. Sci. 2004, 46, 175–208. [Google Scholar]

- Wilcox, R.R. Introduction to Robust Estimation and Hypothesis Testing, 3rd ed.; Statistical Modeling and Decision Science; Academic Press (Elsevier): Waltham, MA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, P.; Drake, C.L. Psychological impact of shift work. Curr. Sleep Med. Rep. 2018, 4, 104–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espie, C.A.; Kyle, S.D.; Williams, C.; Ong, J.C.; Douglas, N.J.; Hames, P.; Brown, J.S.L. A randomized, placebo-controlled trial of online cognitive behavioral therapy for chronic insomnia disorder delivered via an automated media-rich web application. Sleep 2012, 35, 769–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scharfenstein, A.; Basler, H.-D. Schlafstörungen. In Auf dem Weg zu Einem Besseren Schlaf. Schlaftagebuch; Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht: Göttingen, Germany, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Binder, R.; Schöller, F.; Weeß, H.-G. Therapie-Tools Schlafstörungen; Beltz: Weinheim, Germany, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Crönlein, T. Primäre Insomnie. Ein Gruppentherapieprogramm für den Stationären Bereich; Hogrefe: Göttingen, Germany, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Müller, T.; Paterok, B. Schlaftraining. Ein Therapiemanual zur Behandlung von Schlafstörungen, 2nd ed.; Hogrefe: Göttingen, Germany, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Scharfenstein, A.; Basler, H.-D. Schlafstörungen. Auf dem Weg zu Einem Besseren Schlaf. Trainerhandbuch; Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht: Göttingen, Germany, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- American Academy of Sleep Medicine. International Classification of Sleep Disorders (ICSD-3), 3rd ed.; American Academy of Sleep Medicine: Darien, IL, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baglioni, C.; Espie, C.A.; Riemann, D. (Eds.) Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy for Insomnia (CBT-I) Across the Life Span: Guidelines and Clinical Protocols for Health Professionals; John Wiley & Sons Ltd.: Chichester, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Pollmächer, T.; Wetter, T.C.; Bassetti, C.L.A.; Högl, B.; Randerath, W.; Wiater, A. (Eds.) Handbuch Schlafmedizin; Elsevier: München, Germany, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Kerkhof, G.A. Shift work and sleep disorder comorbidity tend to go hand in hand. Chronobiol. Int. 2018, 35, 219–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Åkerstedt, T.; Sallinen, M.; Kecklund, G. Shiftworkers’ attitude to their work hours, positive or negative, and why? Int. Arch. Occup. Environ. Health 2022, 95, 1267–1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Axelsson, J.; Åkerstedt, T.; Kecklund, G.; Lowden, A. Tolerance to shift work—How does it relate to sleep and wakefulness? Int. Arch. Occup. Environ. Health 2004, 77, 121–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinberg, A.; Ashkenazi, I. Internal desynchronization of circadian rhythms and tolerance to shift work. Chronobiol. Int. 2008, 25, 625–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saksvik, I.B.; Bjorvatn, B.; Hetland, H.; Sandal, G.M.; Pallesen, S. Individual differences in tolerance to shift work—A systematic review. Sleep Med. Rev. 2011, 15, 221–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schaub, A.; Roth, E.; Goldmann, U. Kognitiv-Psychoedukative Therapie zur Bewältigung von Depression. Ein Therapiemanual, 2nd ed.; Hogrefe: Göttingen, Germany, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Teismann, T.; Hanning, S.; von Brachel, R.; Willutzki, U. Kognitive Verhaltenstherapie Depressiven Grübelns; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Feld, A.; Rudy, J.M. (Paris-Lodron-Universität Salzburg, Salzburg, Austria). Coaching der Positiven Psychologie. Manual für Coaches, 2017. Unpublished Manual.

- Spiegelhalder, K.; Backhaus, J.; Riemann, D. Schlafstörungen, 2nd ed.; Hogrefe: Göttingen, Germany, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Becker, E.; Margraf, J. Generalisierte Angststörung. Ein Therapieprogramm; Beltz: Weinheim, Germany, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Pitschel-Walz, G.; Bäuml, J.; Kissling, W. Psychoedukation bei Depressionen. Manual zur Leitung von Patienten- und Angehörigengruppen; Urban & Fischer Verlag: München, Germany, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Grünberger, T.; Höhn, C.; Schabus, M.; Laireiter, A.-R. Efficacy study comparing a CBT-I developed for shift workers (CBT-I-S) to standard CBT-I (cognitive behavioural therapy for insomnia) on sleep onset latency, total sleep time, subjective sleep quality, and daytime sleepiness: Study protocol for a parallel group randomized controlled trial with online therapy groups of seven sessions each. Trials 2024, 25, 562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerber, M.; Lang, C.; Lemola, S.; Colledge, F.; Kalak, N.; Holsboer-Trachsler, E.; Pühse, U.; Brand, S. Validation of the German version of the insomnia severity index in adolescents, young adults and adult workers: Results from three cross-sectional studies. BMC Psychiatry 2016, 16, 174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margraf, J.; Cwik, J.C. Mini-DIPS Open Access: Diagnostisches Kurzinterview bei Psychischen Störungen; Forschungs- und Behandlungszentrum für Psychische Gesundheit, Ruhr-Universität Bochum: Bochum, Germany, 2017; pp. 1–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schramm, E.; Hohagen, F.; Graßhoff, U.; Berger, M. Strukturiertes Interview für Schlafstörungen nach DSM-III-R; Beltz Test GmbH: Weinheim, Germany, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed.; DSM-5; American Psychiatric Association: Arlington, VA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Beesdo-Baum, K.; Zaudig, M.; Wittchen, H.-U. (Eds.) SCID-5-CV. Strukturiertes Klinisches Interview für DSM-5R-Störungen—Klinische Version. Deutsche Bearbeitung des Stuctured Clinical Interview for DSM-5R Disorders—Clinician Version von Michael B. First, Jane B. Williams, Rhonda S; Hogrefe: Göttingen, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Randler, C. Psychometric properties of the German version of the Composite Scale of Morningness. Biol. Rhythm Res. 2008, 39, 151–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riemann, D.; Backhaus, J. Behandlung von Schlafstörungen; Psychologie Verlags Union: Weinheim, Germany, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Bloch, K.E.; Schoch, O.D.; Zhang, J.N.; Russi, E.W. German version of the Epworth Sleepiness Scale. Respiration 1999, 66, 440–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weingartz, S.; Pillmann, F. Meinungen-zum-Schlaf-Fragebogen. Deutsche Version der DBAS-16 zur Erfassung dysfunktionaler Überzeugungen und Einstellungen zum Schlaf. Somnologie 2009, 13, 29–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gieselmann, A.; de Jong-Mayer, R.; Pietrowsky, R. Kognitive und körperliche Erregung in der Phase vor dem Einschlafen. Die deutsche Version der Pre-Sleep Arousal Scale (PSAS). Z. Klin. Psych. Psychoth. 2012, 41, 73–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mastin, D.F.; Bryson, J.; Corwyn, R. Assessment of sleep hygiene using the Sleep Hygiene Index. J. Behav. Med. 2006, 29, 223–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrmann-Lingen, C.; Buss, U.; Snaith, R.P. Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale, Deutsche Version (HADS-D), 3rd ed.; Huber: Bern, Switzerland, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Schneewind, K.A.; Graf, J. Der 16-Persönlichkeits-Faktoren-Test, Revidierte Fassung. 16 PF-R—Deutsche Ausgabe des 16 PF Fifth Edition—Testmanual; Hans Huber: Bern, Switzerland, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Faul, F.; Buchner, A.; Erdfelder, E.; Lang, A.-G.; Buchner, A. G*Power3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behav. Res. Methods 2007, 39, 175–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moore, R.F. What is an effect size? Psychiatr. Times 2022, 39, 28–29. [Google Scholar]

- Hemmerich, W. StatistikGuru: Rechner zur Adjustierung des α-Niveaus. Available online: https://statistikguru.de/rechner/adjustierung-des-alphaniveaus.html (accessed on 1 February 2025).

- Wellek, S.; Blettner, M. Klinische Studien zum Nachweis von Äquivalenz oder Nichtunterlegenheit. Teil 20 der Serie zur Bewertung wissenschaftlicher Publikationen. [Establishing equivalence or non-inferiority in clinical trials—Part 20 of a series on evaluation of scientific publications]. Dtsch. Arztebl. Int. 2012, 109, 674–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, S.; Xin, B.; Yu, Y.; Peng, C.; Zhu, C.; Deng, M.; Gao, X.; Chu, J.; Liu, T. Improvement of sleep quality in isolated metastatic patients with spinal cord compression after surgery. World J. Surg. Oncol. 2023, 21, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Morin, C.M.; Schaefer, K.; Wallenstein, G.V. Interpreting score differences in the Insomnia Severity Index: Using health-related outcomes to define the minimally important difference. Curr. Med. Res. Opin. 2009, 25, 2487–2494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed.; L. Erlbaum Associates: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- IBM Corp. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows; Version 29.0.2.0; IBM Corp.: Armonk, NY, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- The Jamovi Project. Jamovi. (Version 2.3.28.0). Available online: https://www.jamovi.org (accessed on 16 October 2024).

| CBT-I-S: n = 24 | CBT-I: n = 31 | Test of a Priori Differences | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | M = 38.88, SD = 8.99 | M = 43.74, SD = 9.11 | t(53) = −1.98, p = 0.053, Cohen’s d = −0.54, CI95% = [−1.08; 0.01] | |

| Gender | f = 9 (37.50%), m = 15 (62.50%) | f = 10 (32.26%), m = 21 (67.74%) | χ2(1) = 0.16, p = 0.685, Cramer’s V = 0.055 | |

| Pre-existing mental conditions (multiple choice) | 1 generalized anxiety disorder, 1 remitted depression, 0 fear of illness, 1 moderate depression, 0 remitted PTSD, 1 remitted anorexia nervosa, 0 restless legs syndrome (independent) 1 mild hypomanic episode | 1 generalized anxiety disorder, 3 remitted depression, 1 fear of illness, 0 moderate depression, 2 remitted PTSD, 0 remitted anorexia nervosa, 1 restless legs syndrome (independent), 1 mild hypomanic episode | χ2(1) = 1.15, p = 0.284, Cramer’s V = 0.144 | |

| Federal state | 12 Salzburg 1 Vienna 2 Lower Austria 2 Upper Austria 2 Styria 1 Tyrol 0 Bavaria 1 Baden–Württemberg 3 North Rhine–Westphalia | 14 Salzburg 2 Vienna 1 Lower Austria 6 Upper Austria 3 Styria 0 Tyrol 3 Bavaria 0 Baden–Württemberg 2 North Rhine–Westphalia | χ2(13) = 13.96, p = 0.377, Cramer’s V = 0.354 | |

| Marital status | 8 single 7 in a partnership 9 married/registered partnership 0 divorced | 3 single 8 in a partnership 18 married/registered partnership 2 divorced | χ2(3) = 6.56, p = 0.088, Cramer’s V = 0.504 | |

| Waiting period (days) | M = 73.49, SD = 52.03 | M = 69.43, SD = 38.73 | t(53) = 0.32, p = 0.747 | |

| Do you like working shifts? | Yes, I don’t mind: 17 (70.83%); No, but I have to: 7 (29.17%) | Yes, I don’t mind: 17 (54.84%); No, but I have to: 14 (45.16%) | χ2(1) = 1.47, p = 0.226, Cramer’s V = 0.163 | |

| Duration of shift work (years) | M = 13.61, SD = 10.55 | M = 16.54, SD = 10.50 | t(53) = −1.02, p = 0.311, Cohen’s d = −0.28, CI95% = [−0.81; 0.26] | |

| Insomnia severity (ISI, see Section 2.4) | M = 15.25, SD = 4.32 | M = 14.81, SD = 3.54 | t(53) = 0.42, p = 0.677, Cohen’s d = 0.114, CI95% = [−0.42; 0.65] | |

| Pittsburgh sleep quality index (PSQI) | Subj. sleep quality | M = 1.75, SD = 0.68 | M = 1.77, SD = 0.50 | t(53) = −0.15, p = 0.879, Cohen’s d = −0.04, CI95% = [−0.57; 0.49] |

| Efficiency (%) | M = 78.11, SD = 9.30 | M = 74.82, SD = 11.57 | t(53) = 1.14, p = 0.261, Cohen’s d = 0.31, CI95% = [−0.23; 0.84] | |

| Sleep onset latency (min) | M = 42.08, SD = 26.54 | M = 35.29, SD = 19.58 | t(53) = 1.09, p = 0.279, Cohen’s d = 0.30, CI95% = [−0.24; 0.83] | |

| Total sleep time (hours) | M = 5.78, SD = 1.19 | M = 5.63, SD = 1.24 | t(53) = 0.45, p = 0.655, Cohen’s d = 0.12, CI95% = [−0.41; 0.66] | |

| PSQI total | M = 9.33, SD = 3.35 | M = 9.87, SD = 2.58 | t(53) = −0.67, p = 0.504, Cohen’s d = −0.18, CI95% = [−0.72; 0.35] | |

| Epworth sleepiness scale (ESS) | M = 7.71, SD = 4.34 | M = 9.13, SD = 3.96 | t(53) = −1.27, p = 0.211, Cohen’s d = −0.34, CI95% = [−0.88; 0.19] | |

| MZS | M = 81.58, SD = 20.66 | M = 76.81, SD = 26.23 | t(53) = 0.73, p = 0.467, Cohen’s d = 0.20, CI95% = [−0.34; 0.73] | |

| Pre-sleep arousal scale | Somatic | M = 12.00, SD = 4.62 | M = 11.52, SD = 3.50 | t(53) = 0.44, p = 0.660, Cohen’s d = 0.12, CI95% = [−0.41; 0.65] |

| Cognitive | M = 16.88, SD = 7.06 | M = 16.74, SD = 6.68 | t(53) = 0.07, p = 0.943, Cohen’s d = 0.02, CI95% = [−0.51; 0.55] | |

| Total | M = 28.88, SD = 10.22 | M = 28.26, SD = 8.15 | t(53) = 0.25, p = 0.804, Cohen’s d = 0.07, CI95% = [−0.47; 0.60] | |

| SHI | M = 19.33, SD = 6,50 | M = 16.90, SD = 5.80 | t(53) = 1.46, p = 0.150, Cohen’s d = 0.40, CI95% = [−0.14; 0.93] | |

| Importance of sleep | M = 3.58, SD = 0.65 | M = 3.65, SD = 0.62 | t(53) = −0.75, p = 0.455, Cohen’s d = −0.21, CI95% = [−0.74; 0.33] | |

| HADS-D | Anxiety | M = 6.25, SD = 3.17 | M = 6.68, SD = 3.29 | t(53) = −0.49, p = 0.629, Cohen’s d = −0.13, CI95% = [−0.67; 0.40] |

| Depression | M = 5.50, SD = 3.74 | M = 5.71, SD = 3.55 | t(53) = −0.21, p = 0.833, Cohen’s d = −0.06, CI95% = [−0.59; 0.48] | |

| Total | M = 11.75, SD = 6.00 | M = 12.39, SD = 6.09 | t(53) = −0.39, p = 0.700, Cohen’s d = −0.11, CI95% = [−0.64; 0.43] | |

| Personality factors: 16 PF-R | C (emo. stab.) | M = 24.83, SD = 4.28 | M = 25.30, SD = 3.22 | t(53) = −0.55, p = 0.586, Cohen’s d = −0.15, CI95% = [−0.68; 0.39] |

| Q4 (tension) | M = 21.63, SD = 6.35 | M = 22.66, SD = 5.33 | t(53) = −0.59, p = 0.560, Cohen’s d = −0.16, CI95% = [−0.69; 0.38] | |

| O (concern) | M = 23.71, SD = 6.07 | M = 23.16, SD = 6.02 | t(53) = 0.33, p = 0.740, Cohen’s d = 0.09, CI95% = [−0.44; 0.62] | |

| Shift system | 2 | 3 | Early and late shift | |

| 9 | 6 | 2 shift: day or night shift, 12 h each | ||

| 6 | 8 | 3 shift: early, late, and night shift | ||

| 0 | 2 | 3 shift: early, late, and split shift | ||

| 0 | 2 | 4 shift | ||

| 3 | 1 | Always 24 h | ||

| 3 | 1 | 12 + 24 h mixed | ||

| 0 | 3 | Regular hours + at least one 24 h per week or on-call duty | ||

| 1 | 4 | Completely irregular | ||

| 0 | 1 | Permanent night shift for 12 h | ||

| Professions | 2 | 9 | Nursing | |

| 1 | 2 | Physician | ||

| 2 | 0 | 1 midwife/1 medical field | ||

| 1 | 2 | Emergency paramedic | ||

| 2 | 0 | Fire department | ||

| 3 | 2 | Railway | ||

| 3 | 3 | Aviation | ||

| 1 | 1 | Traffic | ||

| 6 | 5 | Police | ||

| 1 | 0 | IT support | ||

| 1 | 0 | Journalist | ||

| 1 | 7 | Production/technology/industry | ||

| Variable | Measurement Point | Condition | Measurement Point × Condition | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F(2, 106) | p | η2partial [CI95%] | F(1, 53) | p | η2partial | F(2, 106) | p | η2partial | |

| Insomnia severity (ISI) | 135.02 | 0.003 | 0.72 [0.65; 1.00] | 1.18 | 0.414 | -- | 0.39 | 0.742 | -- |

| Sleep quality (PSQI total) | 80.24 | 0.003 | 0.60 [0.51; 1.00] | 0.06 | 0.843 | 1.10 | 0.470 | ||

| Sleep onset latency | 56.16 | 0.003 | 0.51 [0.41; 1.00] | 2.00 | 0.298 | 0.21 | 0.843 | ||

| Total sleep time | 39.04 | 0.003 | 0.42 [0.31; 1.00] | 0.18 | 0.742 | 1.33 | 0.408 | ||

| Daytime sleepiness (ESS) | 25.87 | 0.003 | 0.33 [0.21; 1.00] | 0.25 | 0.712 | 2.54 | 0.174 | ||

| Variable | Measurement Point | Condition | Measurement Point × Condition | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F(2, 106) | p | η2partial [CI95%] | F(1, 53) | p | η2partial [CI95%] | F(2, 106) | p | η2partial [CI95%] | |

| Subjective sleep quality (SSQ) | 51.86 | 0.003 | 0.49 [0.38; 1.00] | 0.30 | 0.707 | - | 1.60 | 0.336 | - |

| Sleep efficiency | 40.86 | 0.003 | 0.44 [0.32; 1.00] | 0.02 | 0.904 | 1.79 | 0.305 | ||

| Importance of sleep | 7.36 | 0.003 | 0.12 [0.03; 1.00] | 0.01 | 0.923 | 0.71 | 0.633 | ||

| Dysfunctional beliefs about sleep (MZS) | 64.12 | 0.003 | 0.55 [0.44; 1.00] | 1.57 | 0.341 | 0.42 | 0.742 | ||

| Somatic pre-sleep arousal (PSAS soma) | 6.50 | 0.006 | 0.11 [0.03, 1.00] | 2.49 | 0.225 | 3.56 | 0.080 | ||

| Cognitive pre-sleep arousal (PSAS cogn) | 29.69 | 0.003 | 0.36 [0.24; 1.00] | 2.59 | 0.219 | 1.61 | 0.336 | ||

| Total pre-sleep arousal (PSAS total) | 22.62 | 0.003 | 0.30 [0.18; 1.00] | 2.98 | 0.180 | 3.19 | 0.108 | ||

| Sleep hygiene (SHI) | 21.23 | 0.003 | 0.29 [0.17; 1.00] | 6.29 | 0.041 | 0.11 [0.01; 1.00] | 0.60 | 0.683 | |

| Anxiety (HADS-D anxiety) | 20.10 | 0.003 | 0.28 [0.16; 1.00] | 0.27 | 0.711 | 2.55 | 0.174 | ||

| Depression (HADS-D depression) | 15.91 | 0.003 | 0.23 [0.12; 1.00] | 0.59 | 0.592 | 3.00 | 0.125 | ||

| Psychological well-being (HADS-D total) | 26.25 | 0.003 | 0.33 [0.21; 1.00] | 0.50 | 0.633 | 4.03 | 0.055 | ||

| Emotional stability (16-PF: C) | 7.29 | 0.003 | 0.12 [0.03; 1.00] | 1.11 | 0.424 | 1.03 | 0.492 | ||

| Tension (16-PF: Q4) | 5.91 | 0.012 | 0.10 [0.02, 1.00] | 0.35 | 0.683 | 5.42 | 0.017 | 0.09 [0.02; 1.00] | |

| Concern (16-PF: O) | 8.81 | 0.003 | 0.14 [0.05; 1.00] | 1.23 | 0.408 | 2.58 | 0.174 | ||

| Variable | CBT-I-S | CBT-I | Equivalence | Non-Inferiority | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | s2 | M | SD | s2 | CI95% difference | CI95% difference | |

| Insomnia severity (ISI) | 7.83 | 4.51 | 20.32 | 6.45 | 4.68 | 21.86 | [–1.13; 3.89] | [−0.71; ∞] |

| Sleep quality (PSQI total) | 5.29 | 2.56 | 6.56 | 4.65 | 2.80 | 7.84 | [−0.83; 2.12] | [−0.58; ∞] |

| Baseline ISI ≥ 15 | Target Score < 15 | Target Score < 8 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reached | Not Reached | Reached | Not Reached | |

| CBT-I-S | 8 | 5 | 2 | 11 |

| CBT-I | 14 | 2 | 9 | 7 |

| ARR | 25.96%, CI95% = [−5.05%; 56.98%] | 40.87%, CI95% = [9.63%; 72.10%] | ||

| NNT | 3.85 = 4 | 2.45 = 3 | ||

| Baseline ISI ≥ 8 | Target Score < 8 | |||

| Reached | Not reached | |||

| CBT-I-S | 11 | 12 | ||

| CBT-I | 21 | 9 | ||

| ARR | 22.17%, CI95% = [−4.01%; 48.36%] | |||

| NNT | 4.51 = 5 | |||

| Baseline PSQI >10 | Target Score < 11 | Target Score < 6 | ||

| Reached | Not reached | Reached | Not reached | |

| CBT-I-S | 11 | 1 | 7 | 5 |

| CBT-I | 10 | 1 | 7 | 4 |

| ARR | 0.76%, CI95% = [−22.33%; 23.85%] | 5.30%, CI95% = [−34.52%; 45.13%] | ||

| NNH | 132.0 = 132 | 18.86 = 19 | ||

| Baseline PSQI > 5 | Target Score <6 | |||

| Reached | Not reached | |||

| CBT-I-S | 14 | 8 | ||

| CBT-I | 23 | 8 | ||

| ARR | 10.56%, CI95% = [−14.77%; 35.88%] | |||

| NNT | 9.47 = 10 | |||

| Baseline SOL ≥ 30 | Target Score ≤ 30 | |||

| Reached | Not reached | |||

| CBT-I-S | 16 | 1 | ||

| CBT-I | 20 | 1 | ||

| ARR | 1.12%, CI95% = [−13.30%; 15.54%] | |||

| NNT | 89.25 = 90 | |||

| Themes/Categories | CBT-I-S: 13 Open Answers | CBT-I: 17 Open Answers | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive | Negative | Positive | Negative | |

| Thanks | 10 | 10 | ||

| Helpful | 9 | 3 | 8 | 1 |

| Improvement in sleep | 6 | 9 | ||

| Improvement in well-being | 2 | 5 | ||

| Unsuitable for shift workers | 3 | |||

| Implementable into everyday life | 3 | 2 | 3 | 1 |

| Well-prepared documents | 2 | |||

| Interesting | 1 | 4 | ||

| Pleasant group atmosphere | 5 | 1 | ||

| Total training/other | 5 | 5 | ||

| scheduling | 1 | 1 | ||

| Sessions | Contents | Quoted from/Based on/Adapted from: |

|---|---|---|

| After pre-survey | Sleep diary (to keep until the last session) | [27] |

| 1. | Introduction to the program, sleep education, implementation of relaxation method | [28] (pp. 49–52, 75–78, 95–96); [7,29] |

| 2. | Introduction to sleep restriction, calculation of the first sleep window | [27]; [30] (pp. 87–97) |

| 3. | Deepened sleep restriction, repeat relaxation | [30] (pp. 101–103); [7] |

| 4. | Stimulus control, adaptation of the sleep window, repeat relaxation | [7] (pp. 22–25) |

| 5. | Sleep hygiene, sleep hygiene check; adaptation of the sleep window, repeat relaxation | [28] (pp. 135–141); [7] |

| 6. | Cognitive restructuring of dysfunctional thoughts about sleep | [28] (pp. 174–177) |

| 7. | Sharing experiences, reviewing sleep diaries, relapse prevention, goodbye | [31] (pp. 189–190) |

| Sessions | Contents | Partly In-House Development, Partly Quoted from/Based on/Adapted from: |

|---|---|---|

| After pre-survey | Reading material: education on healthy sleep, insomnia, and treatment options | [18,29,30,31,32,33,34,35] |

| 1. | Introduction to therapy Discussion of the reading material Derivation of the therapeutic rationale Effects of attitudes towards shift work | [17,18,29,36,37] |

| 2. | Presentation and discussion of the concept of “shift work tolerance“ Current recommendations for shift workers Positive activities (e.g., social, family, etc.) Daily structure for each shift (early, late, night shift): recognize opportunities “despite shift work”; find an individual relaxation method | [7,9,11,38,39,40] |

| 3. | Central methodologies are employed: systematic problem solving, acceptance, resource orientation. | [41] |

| 4. | (Depressive) rumination: gratitude/happiness diary; grumbling/worrying cessation; relaxation picture | [41,42,43] |

| 5. | Anxiety/concern: decatastrophizing, reality check | [44] |

| 6. | Mood: positive activities, success spoilers, ABC-scheme, cognitive restructuring of dysfunctional (depressive) thoughts | [40,45] |

| 7. | Sharing experiences, emergency kit, relapse prevention, feedback and goodbye | [31] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Grünberger, T.; Höhn, C.; Schabus, M.; Pletzer, B.A.; Laireiter, A.-R. Comparison of Tailored Versus Standard Group Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Shift Worker Insomnia: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Clocks & Sleep 2025, 7, 24. https://doi.org/10.3390/clockssleep7020024

Grünberger T, Höhn C, Schabus M, Pletzer BA, Laireiter A-R. Comparison of Tailored Versus Standard Group Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Shift Worker Insomnia: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Clocks & Sleep. 2025; 7(2):24. https://doi.org/10.3390/clockssleep7020024

Chicago/Turabian StyleGrünberger, Tanja, Christopher Höhn, Manuel Schabus, Belinda Angela Pletzer, and Anton-Rupert Laireiter. 2025. "Comparison of Tailored Versus Standard Group Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Shift Worker Insomnia: A Randomized Controlled Trial" Clocks & Sleep 7, no. 2: 24. https://doi.org/10.3390/clockssleep7020024

APA StyleGrünberger, T., Höhn, C., Schabus, M., Pletzer, B. A., & Laireiter, A.-R. (2025). Comparison of Tailored Versus Standard Group Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Shift Worker Insomnia: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Clocks & Sleep, 7(2), 24. https://doi.org/10.3390/clockssleep7020024