Psychological Screening for Exceptional Environments: Laboratory Circadian Rhythm and Sleep Research

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Background

1.2. The Psychological Screening Process

1.3. The Clinical Interview: Details and Specific Levels of Inquiry

1.4. Disqualification Procedures

1.5. Monitoring the Psychological Wellbeing of Participants Empaneled in a Study

1.6. Psychological Care of Dis-empaneled Participants

1.7. Emergency Protocol

1.8. Repeat Participants

1.9. Screening and In-Study Data from One Example Study

2. Results

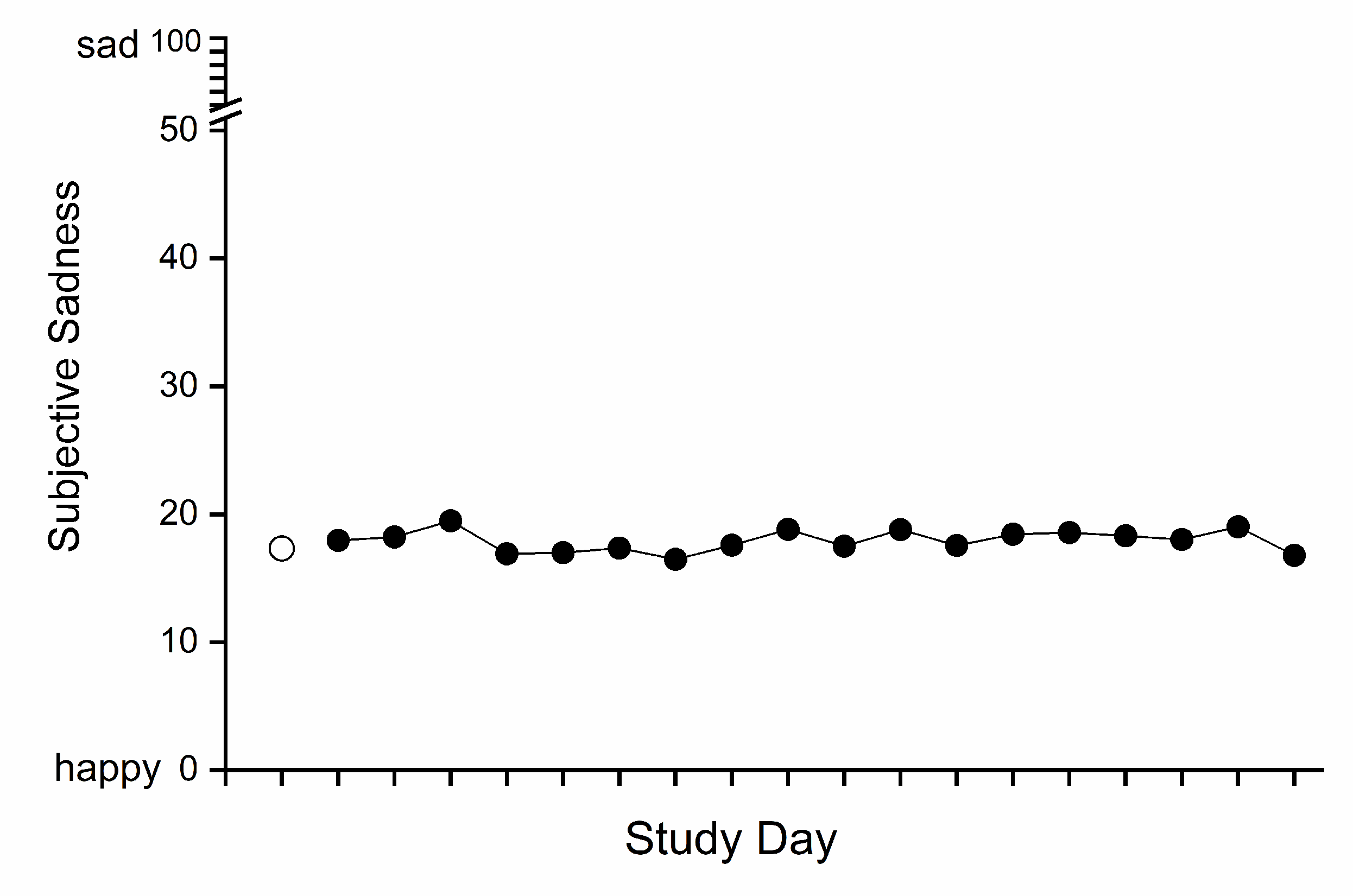

2.1. Subjective Mood

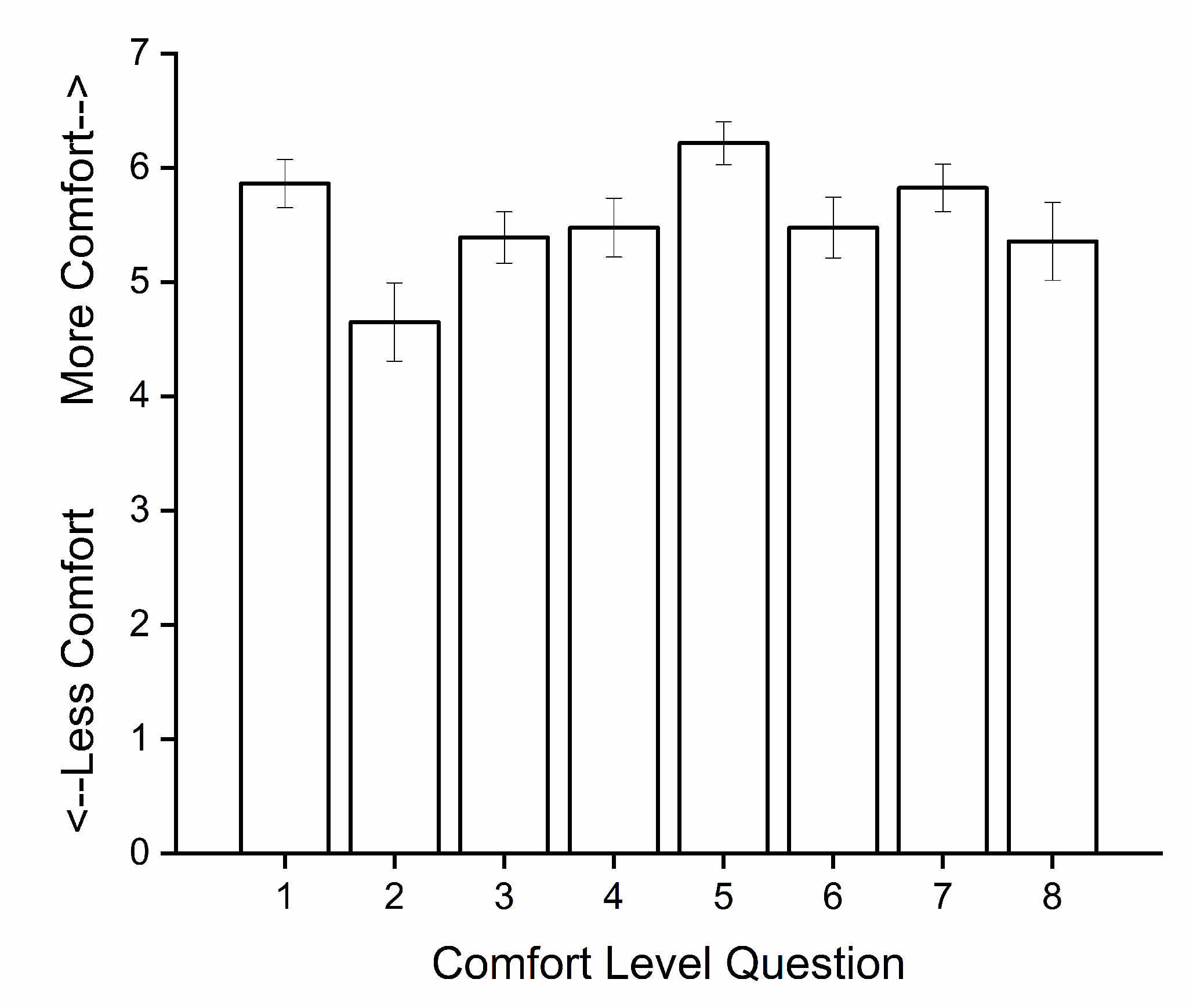

2.2. Overall Study Evaluation

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Participants and Protocol

4.2. Subjective Mood Data

4.3. Overall Study Evaluation Data

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

References

- Leach, J. Psychological factors in exceptional, extreme and torturous environments. Extrem Physiol. Med. 2016, 5, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palinkas, L.A. The psychology of isolated and confined environments. Understanding human behavior in Antarctica. Am. Psychol. 2003, 58, 353–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suedfeld, P.; Weiss, K. Antarctica. Natural laboratory and space analogue for psychological research. Environ. Behav. 2000, 32, 7–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanas, N.; Manzey, D. Space Psychology and Psychiatry; Microcosm Press and Springer: El Segundo, CA, USA, 2008; p. 240. [Google Scholar]

- Pagel, J.I.; Chouker, A. Effects of isolation and confinement on humans-Implications for manned space explorations. J. Appl. Physiol. 2016, 120, 1449–1457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plaza, J.C.; Garcés de los Fayos Ruiz, E.J.; López García, J.J.; Colodro Conde, L. Prediction of human adaptation and performance in underwater environments. Psicothema 2014, 26, 336–342. [Google Scholar]

- Slack, K.J.; Williams, T.J.; Schneiderman, J.S.; Whitmire, A.M.; Picano, J.J. Risk of Adverse Cognitive or Behavioral Conditions and Psychiatric Disorders: Evidence Report; JSC-CN-35772; National Aeronautics and Space Administration: Houston, TX, USA, 2016; p. 124.

- Grady, C. Money for research participation: Does in (sic) jeopardize informed consent? Am. J. Bioethics 2001, 1, 40–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klitzman, R. How IRBs view and make decisions about coercion and undue influence. J. Med. Ethics 2013, 39, 224–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pettersson, E.; Lichtenstein, P.; Larsson, H.; Song, J.; Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder Working Group of the iPSYCH-Broad-PGC Consortium; Autism Spectrum Disorder Working Group of the iPSYCH-Broad-PGC Consortium; Bipolar Disorder Working Group of the PGC; Eating Disorder Working Group of the PGC; Major Depressive Disorder Working Group of the PGC; Obsessive Compulsive Disorders and Tourette Syndrome Working Group of the PGC; et al. Genetic influences on eight psychiatric disorders based on family data of 4 408 646 full and half-siblings, and genetic data of 333 748 cases and controls. Psychol. Med. 2019, 49, 1166–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Butcher, J.N.; Dahlstrom, W.G.; Graham, J.R.; Tellegen, A.; Kaemmer, B. The Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory-2 (MMPI-2): Manual for Administration and Scoring; University of Minnesota Press: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Derogatis, L.R.; Lipman, R.S.; Rickels, K.; Uhlenhuth, E.H.; Covi, L. The Hopkins Symptom Checklist (HSCL): A self-report symptom inventory. Behav. Sci. 1974, 19, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maruish, M.E. (Ed.) The Use of Psychological Testing for Treatment Planning and Outcomes Assessment: General Considerations, 3rd ed.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.: Mahway, NJ, USA, 2004; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Beck, A.T.; Steer, R.A.; Brown, G.K. Manual for the Beck Depression Inventory-II; Psychological Corporation: San Antonio, TX, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Yesavage, J.A.; Brink, T.L.; Rose, T.L.; Lum, O.; Huang, V.; Adey, M.; Leirer, V.O. Development and validation of a geriatric depression screening scale: A preliminary report. J. Psychiat. Res. 1982, 17, 37–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spielberger, C.D.; Gorsuch, R.L.; Lushene, R.; Vagg, P.R.; Jacobs, G.A. Manual for the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory; Consulting Psychologists Press: Palo Alto, CA, USA, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Bellak, L.; Karasu, T.B. (Eds.) Geriatric Psychiatry: A Handbook for Psychiatrists and Primary Care Physicians; Grune & Stratton: New York, NY, USA, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Folstein, M.F.; Folstein, S.E.; McHugh, P.R. “Mini-mental state”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J. Psychiatr. Res. 1975, 12, 189–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buxton, O.M.; Cain, S.W.; O’Connor, S.P.; Porter, J.H.; Duffy, J.F.; Wang, W.; Czeisler, C.A.; Shea, S.A. Adverse metabolic consequences in humans of prolonged sleep restriction combined with circadian disruption. Sci. Transl. Med. 2012, 4, 129ra43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zitting, K.M.; Münch, M.Y.; Cain, S.W.; Wang, W.; Wong, A.; Ronda, J.M.; Aeschbach, D.; Czeisler, C.A.; Duffy, J.F. Young adults are more vulnerable to chronic sleep deficiency and recurrent circadian disruption than older adults. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 11052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cain, S.W.; Silva, E.J.; Münch, M.Y.; Czeisler, C.A.; Duffy, J.F. Chronic sleep restriction impairs reaction time performance more in young than in older subjects. Sleep 2010, 33, A85. [Google Scholar]

- Silva, E.J.; Cain, S.W.; Münch, M.Y.; Wang, W.; Ronda, J.M.; Czeisler, C.A.; Duffy, J.F. Recovery of neurobehavioral function in a group of young adults following chronic sleep restriction. Sleep 2010, 33, A103–A104. [Google Scholar]

- Pomplun, M.; Silva, E.J.; Ronda, J.M.; Cain, S.W.; Münch, M.Y.; Czeisler, C.A.; Duffy, J.F. The effects of circadian phase, time awake, and imposed sleep restriction on performing complex visual tasks: Evidence from comparative visual search. J. Vis. 2012, 12, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aitken, R.C.B. Measurement of feelings using visual analogue scales. Proc. Roy. Soc. Med. 1969, 62, 989–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bond, A.; Lader, M. The use of analogue scales in rating subjective feelings. Br. J. Med. Psychol. 1974, 47, 211–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 1. Restrictions in activity level (e.g., light stretching only, no strenuous exercise, no formal meditation as this can drive metabolic output in two directions, therefore, people must be prepared to limit these activities as these are not variables we are testing) (e.g., no exercise or activities that change heart rate, no meditation, no lying down during the daytime) |

| 2. Absence of time cues (e.g., no windows in study rooms; no clocks, watches, timers; no live television, radio, internet) |

| 3. Acute and chronic sleep loss and sleep distribution A. Acute sleep deprivation ● e.g., >18 h continuous wake periods B. Chronic sleep deprivation: ● e.g., <7 h in a 24-h period over many days C. Sleep disruption: ● e.g., sleep scheduled at times when it is difficult to fall asleep or remain asleep |

| 4. Lighting intensity and exposure variations during sleep A. Dim light (e.g., <4 lux) B. Bright light (e.g., >500–10,000 lux) C. Complete darkness (scheduled sleep episodes throughout) |

| 5. Prolonged sedentary behavior A. Specialized circadian assessment—sitting in bed for extended time periods (e.g., procedures that last 16–50 h, no vertical position as it can impact blood pressure which is one of the time cues) |

| 6. Limited autonomy A. Investigators monitor and control physiological functions according to precise schedules B. Timing and duration of meals and showers is limited by protocol demands C. Inflexibility of meal content once dietitians have prepared menu D. Frequent interruptions of free-time for study-related events |

| 7. Limited outside communication A. No direct contact with friends, family, and significant others for the extent of their study B. Limited communication in the form of letters (no email, calls, etc.) C. Regular engagement with supportive trained staff only |

| Five Select-Out/Select-In Categorical Criteria | |

|---|---|

| 1. Participant Biology | To not skew or affect results such as neuroendocrine changes |

| 2. Participant Health Risks | Where conditions may put them at risk to their physical health |

| 3. Participant Lab Risks | Character types who are difficult to manage or who may be hostile and litigious. |

| 4. Participant Completion | Those who are not likely to complete the study for physical or psychological reasons. |

| 5. Participant Incentives | Due to cachet involved (for example, the desire to participate in a NASA-funded study) or level of remuneration offered |

| Select-Out/Select-In Testing Measures | |

|---|---|

| Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory-2 (MMPI-2 [11]) (Administered by a research assistant to serve as a first-line screen prior to further psychological inquiry) | Depression scale, T > 70: excluded automatically |

| Psychopathic deviance, T > 75: excluded automatically * schizophrenia, hypomania scales | |

| L, F, and K validity scales, T > 80: excluded automatically other clinical scales | |

| L, F, and K validity scales, T > 70: held pending interview ** and other clinical scales | |

| Symptom Checklist 90-R (SCL-90-R [12,13]) | Depression scale, Distress level >1.25: excluded automatically |

| Hostility scale, >1: excluded automatically | |

| Phobic anxiety, >0.75: excluded automatically | |

| Paranoid ideation, >1.25: excluded automatically | |

| Psychoticism, >1: excluded automatically | |

| Anxiety, >1.25: excluded automatically | |

| Somatization, >1.00: excluded automatically | |

| Obsessive compulsive, >1.20: excluded automatically | |

| Interpersonal sensitivity, >1.25: excluded automatically | |

| Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II [14]) | Score of 10 or above excluded automatically |

| State–Trait Anxiety Inventory for Adults (STAI-AD [16]) | >40: excluded automatically |

| Clinical Interview by Licensed Psychologist (see Table 4 for details) | To confirm volunteer participant awareness and to determine individual study appropriateness |

| Mattis Dementia Rating Scale (DRS [17]) | <123: excluded automatically |

| Folstein test/ Mini-Mental Exam (MMSE [18]) | <27: excluded automatically |

| Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS [15]) | 10: excluded automatically |

| What Follows Here Is the Approach We Have Used for over 30 Years to Screen over Two Thousand Participants. |

|---|

| Interview Question(s)/Procedure(s) |

| ● Outlines, Objectives, Rules, and Goals ✓ Points of Interest ○ Details and Side-notes |

| Section A. Study Overview |

1. An introduction:

|

| 2.“How did you hear of our study?” |

3.“Why volunteer for something like this?”

|

4.“What is this study all about? Can you describe briefly what we are researching?”

|

5. We next describe the study in detail

|

| Section B. Medical History |

6. Review of their living situation and their past and current health status

|

| Section C. Personal History |

7. “Where were you born and where were you raised?”

|

| 8. “Thinking about the first 12 years of your life, in a sentence or two, how was that time for you? What do you remember? What was it like?” Any suggestion of difficulty is explored

|

| Section D. Mental Status |

9. Interview Behavior and Personal Appearance

|

10. Vegetative Functions Assessment

|

11. Mental Health History

|

12. Outside Interests

|

| Participant Exclusionary Examples | |

|---|---|

| 1. Exclusion Prior to Interview | A 19-year-old college student had an MMPI profile with significant elevations on 4 clinical scales (i.e.,: Pd-psychopathic deviate, Pa-paranoia, Pt-psychasthenia, and Sc-schizophrenia). In a phone call after the exclusion, the profile was interpreted at the participant’s request and the accuracy of the findings was acknowledged (e.g.,: introverted, socially withdrawn, insecure, lacking self-esteem, guilt over perceived shortcomings, etc.). The participant stated a willingness to get counseling help and was responsive to an offer of a meeting with the psychologist while securing a referral. |

| 2. In-study Psychological Intervention | The psychologist was called to visit with a participant after staff expressed concerns about her personal hygiene, attitudes toward some staff, and social skills. The participant revealed that she had taken offense that one of the techs had briefly looked at one of the books she was reading rather than immediately attending to her. She registered her upset by staring at a wall and being noncommunicative, which she acknowledged was a tactic she uses to register disapproval. Moreover, she admitted she is sensitive to slight and rejection and avoids direct confrontation by being passive. She responded well when told “We know these are exceptional circumstances. Not only do you have a right to express your needs at any time, we want and need your input and reactions.” Having discussed the situation, she felt freer to express her needs and sensitivities, and continued with the study until completion |

| 3. Dis-empaneled | The participant was a 19-year-old female who was dis-empaneled with 11 days to go in a 32-day study. This action was precipitated by a significant drop in her mood scales, indicating she was very unhappy. After initially refusing to speak with the psychologist about the change in her mood, she did ultimately admit to missing family (who were communicating with her appropriately), but more importantly, that she had not received any return e-mail communication from her fiancé. She had a nightmare that he broke off the engagement. She knew it was only a dream but for days she did not receive an e-mail from him. Our staff contacted the participant’s sister who in turn had the fiancé write. The psychologist spoke with her after she was discharged and ascertained that she was doing well. She had never indicated at screening that she was engaged. |

| To Assess How the Participant Is Faring under the Study Conditions | |

| Steps and Examples | |

| Steps | Examples/Explanations |

| 1. Staff and Chart Review | Before entering the participant’s room, the psychologist checks with the staff and reviews the chart to see if there are any issues of concern. |

| 2. Participant Interaction | Upon entering, the psychologist will typically engage in some small talk, ask how the participant is doing, what has been the greatest challenge, have there been any surprises or unexpected aspects, did they feel well prepared? |

| 3. Assess Activity Level | We want to know how they are keeping busy, and therefore try to have a discussion with them about their activities, readings, videos, etc. |

| 4. Assess Affects | They are asked about their mood in general but then asked specifically about particular affects: anxiety, fear, frustration, irritation, boredom, loneliness, sadness, anger, joy, happiness, and inquire in further detail about any they endorse. |

| 5. Assess Sleep Quality | We discuss their sleep quality and compare it to what they typically experience at home and inquire about dream frequency and whether their dreams are pleasant or unpleasant. |

| 6. Assess Appetite and Food | We also discuss their appetite and the food. Is their appetite modified based on emotions or food quality and/or lack of choices. We ask about food because that could be a control issue and appetite changes may be associated with certain psychological issues. |

| 7. Assess Outside Communications | We inquire whether they have had contacts with friends or family and how they have felt about those contacts. |

| 8. Assess Internal Communications | We also discuss their relations with the nursing and technical staff, their study project leader, and the PI of the study. |

| 9. Assess Questions, Worries, and Concerns | We use this visit to remind them that if anything is bothering them or causing them distress we want them to communicate with us, so we can do whatever we can within the constraints of the protocol to make them more comfortable (See Table 5, example 3). We emphasize that the worst thing in such an environment is holding back feelings or concerns. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Amira, S.A.; Bressler, B.L.; Lee, J.H.; Czeisler, C.A.; Duffy, J.F. Psychological Screening for Exceptional Environments: Laboratory Circadian Rhythm and Sleep Research. Clocks & Sleep 2020, 2, 153-171. https://doi.org/10.3390/clockssleep2020013

Amira SA, Bressler BL, Lee JH, Czeisler CA, Duffy JF. Psychological Screening for Exceptional Environments: Laboratory Circadian Rhythm and Sleep Research. Clocks & Sleep. 2020; 2(2):153-171. https://doi.org/10.3390/clockssleep2020013

Chicago/Turabian StyleAmira, Stephen A., Brenda L. Bressler, Jung Hie Lee, Charles A. Czeisler, and Jeanne F. Duffy. 2020. "Psychological Screening for Exceptional Environments: Laboratory Circadian Rhythm and Sleep Research" Clocks & Sleep 2, no. 2: 153-171. https://doi.org/10.3390/clockssleep2020013

APA StyleAmira, S. A., Bressler, B. L., Lee, J. H., Czeisler, C. A., & Duffy, J. F. (2020). Psychological Screening for Exceptional Environments: Laboratory Circadian Rhythm and Sleep Research. Clocks & Sleep, 2(2), 153-171. https://doi.org/10.3390/clockssleep2020013