Recent Advances in Arboviral Vaccines: Emerging Platforms and Promising Innovations

Abstract

:1. Introduction

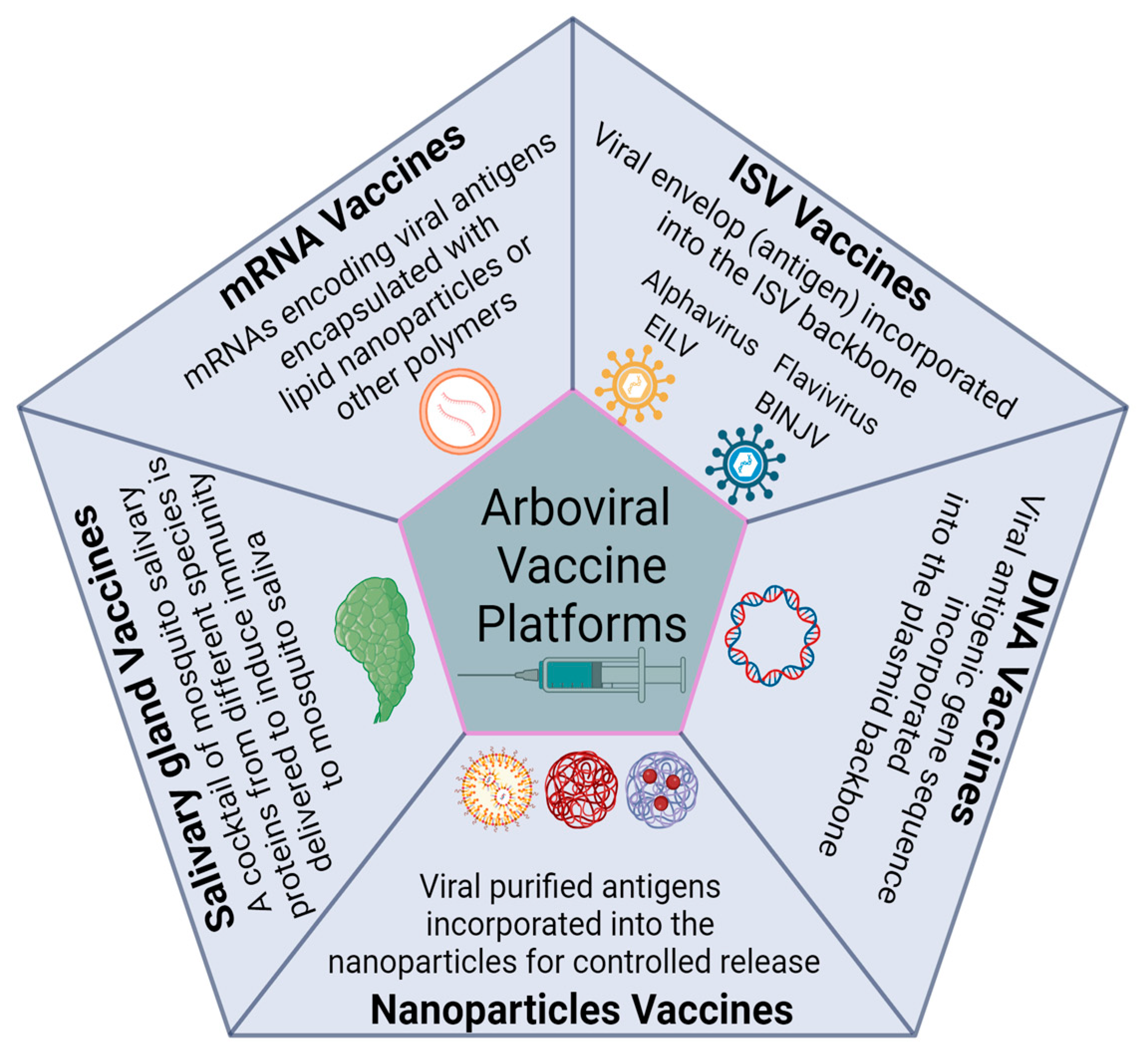

2. Arboviral Vaccine Platforms

2.1. Insect-Specific Viruses Platform

2.1.1. Eilat Virus (EILV)

2.1.2. Binjari Virus (BINJV)

2.2. DNA Vaccine Platform

2.3. Nanoparticle-Based Platform

2.4. Mosquito Salivary Protein Vaccine

2.5. mRNA Vaccine

3. Host Immune Response and Arboviral Vaccine Designing

4. Non-Vaccine Methods to Control Arboviruses

5. Conclusions and Future Perspectives

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Minta, A.A.; Ferrari, M.; Antoni, S.; Portnoy, A.; Sbarra, A.; Lambert, B.; Hauryski, S.; Hatcher, C.; Nedelec, Y.; Datta, D.; et al. Progress Toward Regional Measles Elimination—Worldwide, 2000–2021. MMWR Morb. Mortal Wkly. Rep. 2022, 71, 1489–1495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Badizadegan, K.; Kalkowska, D.A.; Thompson, K.M. Polio by the Numbers-A Global Perspective. J. Infect. Dis. 2022, 226, 1309–1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kayser, V.; Ramzan, I. Vaccines and vaccination: History and emerging issues. Hum. Vaccin. Immunother. 2021, 17, 5255–5268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mathieu, E. Coronavirus (COVID-19) Vaccinations. Available online: https://ourworldindata.org/covid-vaccinations (accessed on 19 November 2023).

- Mathieu, E.; Ritchie, H.; Ortiz-Ospina, E.; Roser, M.; Hasell, J.; Appel, C.; Giattino, C.; Rodes-Guirao, L. A global database of COVID-19 vaccinations. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2021, 5, 947–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torto, B.; Tchouassi, D.P. Grand Challenges in Vector-Borne Disease Control Targeting Vectors. Front. Trop. Dis. 2021, 1, 635356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aryaprema, V.S.; Steck, M.R.; Peper, S.T.; Xue, R.D.; Qualls, W.A. A systematic review of published literature on mosquito control action thresholds across the world. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2023, 17, e0011173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenwood, B. Treatment of malaria--a continuing challenge. N. Engl. J. Med. 2014, 371, 474–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ladzinski, A.T.; Tai, A.; Rumschlag, M.T.; Smith, C.S.; Mehta, A.; Boapimp, P.; Edewaard, E.J.; Douce, R.W.; Morgan, L.F.; Wang, M.S.; et al. Clinical Characteristics of the 2019 Eastern Equine Encephalitis Outbreak in Michigan. Open Forum Infect. Dis. 2023, 10, ofad206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pujhari, S.K.; Prabhakar, S.; Ratho, R.K.; Modi, M.; Sharma, M.; Mishra, B. A novel mutation (S227T) in domain II of the envelope gene of Japanese encephalitis virus circulating in North India. Epidemiol. Infect. 2011, 139, 849–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pujhari, S.; Brustolin, M.; Macias, V.M.; Nissly, R.H.; Nomura, M.; Kuchipudi, S.V.; Rasgon, J.L. Heat shock protein 70 (Hsp70) mediates Zika virus entry, replication, and egress from host cells. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 2019, 8, 8–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodson, B.L.; Pujhari, S.; Rasgon, J.L. Vector competence of selected North American Anopheles and Culex mosquitoes for Zika virus. PeerJ 2018, 6, e4324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pujhari, S.K.; Prabhakar, S.; Ratho, R.; Mishra, B.; Modi, M.; Sharma, S.; Singh, P. Th1 immune response takeover among patients with severe Japanese encephalitis infection. J. Neuroimmunol. 2013, 263, 133–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaythorpe, K.A.; Hamlet, A.; Jean, K.; Garkauskas Ramos, D.; Cibrelus, L.; Garske, T.; Ferguson, N. The global burden of yellow fever. Elife 2021, 10, 64670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, S.M. The current burden of Japanese encephalitis and the estimated impacts of vaccination: Combining estimates of the spatial distribution and transmission intensity of a zoonotic pathogen. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2021, 15, e0009385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, S.K.; Bhattacharjee, S. Dengue virus: Epidemiology, biology, and disease aetiology. Can. J. Microbiol. 2021, 67, 687–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torresi, J.; Ebert, G.; Pellegrini, M. Vaccines licensed and in clinical trials for the prevention of dengue. Hum. Vaccin. Immunother. 2017, 13, 1059–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osorio, J.E.; Wallace, D.; Stinchcomb, D.T. A recombinant, chimeric tetravalent dengue vaccine candidate based on a dengue virus serotype 2 backbone. Expert. Rev. Vaccines 2016, 15, 497–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freedman, D.O. A new dengue vaccine (TAK-003) now WHO recommended in endemic areas; what about travelers? J. Travel. Med. 2023, 30, taad132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clancy, I.L.; Jones, R.T.; Power, G.M.; Logan, J.G.; Iriart, J.A.B.; Massad, E.; Kinsman, J. Public health messages on arboviruses transmitted by Aedes aegypti in Brazil. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 1362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez, M.; Martinez, D.; Munoz, M.; Ramirez, J.D. Aedes aegypti and Ae. albopictus microbiome/virome: New strategies for controlling arboviral transmission? Parasit. Vectors 2022, 15, 287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanelus, M.; Lopez, K.; Smith, S.; Muller, J.A.; Porier, D.L.; Auguste, D.I.; Stone, W.B.; Paulson, S.L.; Auguste, A.J. Exploring the immunogenicity of an insect-specific virus vectored Zika vaccine candidate. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 19948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobson-Peters, J.; Harrison, J.J.; Watterson, D.; Hazlewood, J.E.; Vet, L.J.; Newton, N.D.; Warrilow, D.; Colmant, A.M.G.; Taylor, C.; Huang, B.; et al. A recombinant platform for flavivirus vaccines and diagnostics using chimeras of a new insect-specific virus. Sci. Transl. Med. 2019, 11, eaax7888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, V.L.; Long, M.T. Perspectives on New Vaccines against Arboviruses Using Insect-Specific Viruses as Platforms. Vaccines 2021, 9, 263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adam, A.; Luo, H.; Osman, S.R.; Wang, B.; Roundy, C.M.; Auguste, A.J.; Plante, K.S.; Peng, B.H.; Thangamani, S.; Frolova, E.I.; et al. Optimized production and immunogenicity of an insect virus-based chikungunya virus candidate vaccine in cell culture and animal models. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 2021, 10, 305–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erasmus, J.H.; Seymour, R.L.; Kaelber, J.T.; Kim, D.Y.; Leal, G.; Sherman, M.B.; Frolov, I.; Chiu, W.; Weaver, S.C.; Nasar, F. Novel Insect-Specific Eilat Virus-Based Chimeric Vaccine Candidates Provide Durable, Mono- and Multivalent, Single-Dose Protection against Lethal Alphavirus Challenge. J. Virol. 2018, 92, e01274-17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habarugira, G.; Harrison, J.J.; Moran, J.; Suen, W.W.; Colmant, A.M.G.; Hobson-Peters, J.; Isberg, S.R.; Bielefeldt-Ohmann, H.; Hall, R.A. A chimeric vaccine protects farmed saltwater crocodiles from West Nile virus-induced skin lesions. npj Vaccines 2023, 8, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazlewood, J.E.; Tang, B.; Yan, K.; Rawle, D.J.; Harrison, J.J.; Hall, R.A.; Hobson-Peters, J.; Suhrbier, A. The Chimeric Binjari-Zika Vaccine Provides Long-Term Protection against ZIKA Virus Challenge. Vaccines 2022, 10, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagliari, S.; Dema, B.; Sanchez-Martinez, A.; Montalvo Zurbia-Flores, G.; Rollier, C.S. DNA Vaccines: History, Molecular Mechanisms and Future Perspectives. J. Mol. Biol. 2023, 435, 168297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danko, J.R.; Kochel, T.; Teneza-Mora, N.; Luke, T.C.; Raviprakash, K.; Sun, P.; Simmons, M.; Moon, J.E.; De La Barrera, R.; Martinez, L.J.; et al. Safety and Immunogenicity of a Tetravalent Dengue DNA Vaccine Administered with a Cationic Lipid-Based Adjuvant in a Phase 1 Clinical Trial. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2018, 98, 849–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dowd, K.A.; Ko, S.Y.; Morabito, K.M.; Yang, E.S.; Pelc, R.S.; DeMaso, C.R.; Castilho, L.R.; Abbink, P.; Boyd, M.; Nityanandam, R.; et al. Rapid development of a DNA vaccine for Zika virus. Science 2016, 354, 237–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ledgerwood, J.E.; Pierson, T.C.; Hubka, S.A.; Desai, N.; Rucker, S.; Gordon, I.J.; Enama, M.E.; Nelson, S.; Nason, M.; Gu, W.; et al. A West Nile virus DNA vaccine utilizing a modified promoter induces neutralizing antibody in younger and older healthy adults in a phase I clinical trial. J. Infect. Dis. 2011, 203, 1396–1404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutta, S.K.; Langenburg, T. A Perspective on Current Flavivirus Vaccine Development: A Brief Review. Viruses 2023, 15, 860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthumani, K.; Lankaraman, K.M.; Laddy, D.J.; Sundaram, S.G.; Chung, C.W.; Sako, E.; Wu, L.; Khan, A.; Sardesai, N.; Kim, J.J.; et al. Immunogenicity of novel consensus-based DNA vaccines against Chikungunya virus. Vaccine 2008, 26, 5128–5134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallilankaraman, K.; Shedlock, D.J.; Bao, H.; Kawalekar, O.U.; Fagone, P.; Ramanathan, A.A.; Ferraro, B.; Stabenow, J.; Vijayachari, P.; Sundaram, S.G.; et al. A DNA vaccine against chikungunya virus is protective in mice and induces neutralizing antibodies in mice and nonhuman primates. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2011, 5, e928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brule, C.E.; Grayhack, E.J. Synonymous Codons: Choose Wisely for Expression. Trends Genet. 2017, 33, 283–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrau, L.; Rezelj, V.V.; Noval, M.G.; Levi, L.I.; Megrian, D.; Blanc, H.; Weger-Lucarelli, J.; Moratorio, G.; Stapleford, K.A.; Vignuzzi, M. Chikungunya Virus Vaccine Candidates with Decreased Mutational Robustness Are Attenuated In Vivo and Have Compromised Transmissibility. J. Virol. 2019, 93, e00775-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Bree, J.W.M.; Visser, I.; Duyvestyn, J.M.; Aguilar-Bretones, M.; Marshall, E.M.; van Hemert, M.J.; Pijlman, G.P.; van Nierop, G.P.; Kikkert, M.; Rockx, B.H.G.; et al. Novel approaches for the rapid development of rationally designed arbovirus vaccines. One Health 2023, 16, 100565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, A.E.; Rihn, S.J.; Mollentze, N.; Wickenhagen, A.; Stewart, D.G.; Orton, R.J.; Kuchi, S.; Bakshi, S.; Collados, M.R.; Turnbull, M.L.; et al. The antiviral state has shaped the CpG composition of the vertebrate interferome to avoid self-targeting. PLoS Biol. 2021, 19, e3001352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fros, J.J.; Dietrich, I.; Alshaikhahmed, K.; Passchier, T.C.; Evans, D.J.; Simmonds, P. CpG and UpA dinucleotides in both coding and non-coding regions of echovirus 7 inhibit replication initiation post-entry. Elife 2017, 6, e29112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharp, C.P.; Thompson, B.H.; Nash, T.J.; Diebold, O.; Pinto, R.M.; Thorley, L.; Lin, Y.T.; Sives, S.; Wise, H.; Clohisey Hendry, S.; et al. CpG dinucleotide enrichment in the influenza A virus genome as a live attenuated vaccine development strategy. PLoS Pathog. 2023, 19, e1011357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trus, I.; Udenze, D.; Karniychuk, U. Generation of CpG-Recoded Zika Virus Vaccine Candidates. Methods Mol. Biol. 2022, 2410, 289–302. [Google Scholar]

- Manokaran, G.; Sujatmoko; McPherson, K.G.; Simmons, C.P. Attenuation of a dengue virus replicon by codon deoptimization of nonstructural genes. Vaccine 2019, 37, 2857–2863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Ke, X.; Wang, T.; Tan, Z.; Luo, D.; Miao, Y.; Sun, J.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Hu, Q.; et al. Zika Virus Attenuation by Codon Pair Deoptimization Induces Sterilizing Immunity in Mouse Models. J. Virol. 2018, 92, e00701-18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nougairede, A.; De Fabritus, L.; Aubry, F.; Gould, E.A.; Holmes, E.C.; de Lamballerie, X. Random codon re-encoding induces stable reduction of replicative fitness of Chikungunya virus in primate and mosquito cells. PLoS Pathog. 2013, 9, e1003172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Fabritus, L.; Nougairede, A.; Aubry, F.; Gould, E.A.; de Lamballerie, X. Attenuation of tick-borne encephalitis virus using large-scale random codon re-encoding. PLoS Pathog. 2015, 11, e1004738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, F.; Liu, X.; Li, L.; Mallapragada, S.; Narasimhan, B.; Wang, Q. Multifunctional nanoparticles for targeted delivery of immune activating and cancer therapeutic agents. J. Control Release 2013, 172, 1020–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priyanka; Abusalah, M.A.H.; Chopra, H.; Sharma, A.; Mustafa, S.A.; Choudhary, O.P.; Sharma, M.; Dhawan, M.; Khosla, R.; Loshali, A.; et al. Nanovaccines: A game changing approach in the fight against infectious diseases. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2023, 167, 115597. [Google Scholar]

- Lv, T.; Meng, Y.; Liu, Y.; Han, Y.; Xin, H.; Peng, X.; Huang, J. RNA nanotechnology: A new chapter in targeted therapy. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2023, 230, 113533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kucuk, N.; Primozic, M.; Knez, Z.; Leitgeb, M. Sustainable Biodegradable Biopolymer-Based Nanoparticles for Healthcare Applications. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 3188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idrees, H.; Zaidi, S.Z.J.; Sabir, A.; Khan, R.U.; Zhang, X.; Hassan, S.U. A Review of Biodegradable Natural Polymer-Based Nanoparticles for Drug Delivery Applications. Nanomaterials 2020, 10, 1970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamage, A.; Thiviya, P.; Mani, S.; Ponnusamy, P.G.; Manamperi, A.; Evon, P.; Merah, O.; Madhujith, T. Environmental Properties and Applications of Biodegradable Starch-Based Nanocomposites. Polymers 2022, 14, 4578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulkarni, S.A.; Feng, S.S. Effects of particle size and surface modification on cellular uptake and biodistribution of polymeric nanoparticles for drug delivery. Pharm. Res. 2013, 30, 2512–2522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goode, E.F.; Roussos Torres, E.T.; Irshad, S. Lymph Node Immune Profiles as Predictive Biomarkers for Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor Response. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2021, 8, 674558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eygeris, Y.; Gupta, M.; Kim, J.; Sahay, G. Chemistry of Lipid Nanoparticles for RNA Delivery. Acc. Chem. Res. 2022, 55, 2–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Y.; Marioli, M.; Zhang, K. Analytical characterization of liposomes and other lipid nanoparticles for drug delivery. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2021, 192, 113642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, P.C.; Lin, S.; Wang, P.C.; Sridhar, R. Techniques for physicochemical characterization of nanomaterials. Biotechnol. Adv. 2014, 32, 711–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okamoto, S.; Yoshii, H.; Matsuura, M.; Kojima, A.; Ishikawa, T.; Akagi, T.; Akashi, M.; Takahashi, M.; Yamanishi, K.; Mori, Y. Poly-gamma-glutamic acid nanoparticles and aluminum adjuvant used as an adjuvant with a single dose of Japanese encephalitis virus-like particles provide effective protection from Japanese encephalitis virus. Clin. Vaccine Immunol. 2012, 19, 17–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Souza, G.A.P.; Rocha, R.P.; Goncalves, R.L.; Ferreira, C.S.; de Mello Silva, B.; de Castro, R.F.G.; Rodrigues, J.F.V.; Junior, J.; Malaquias, L.C.C.; Abrahao, J.S.; et al. Nanoparticles as Vaccines to Prevent Arbovirus Infection: A Long Road Ahead. Pathogens 2021, 10, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nevagi, R.J.; Khalil, Z.G.; Hussein, W.M.; Powell, J.; Batzloff, M.R.; Capon, R.J.; Good, M.F.; Skwarczynski, M.; Toth, I. Polyglutamic acid-trimethyl chitosan-based intranasal peptide nano-vaccine induces potent immune responses against group A streptococcus. Acta Biomater. 2018, 80, 278–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.U.; Keya, C.A.; Das, K.C.; Hashem, A.; Omar, T.M.; Khan, M.A.; Rakib-Uz-Zaman, S.M.; Salimullah, M. An Immunopharmacoinformatics Approach in Development of Vaccine and Drug Candidates for West Nile Virus. Front. Chem. 2018, 6, 246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kose, N.; Fox, J.M.; Sapparapu, G.; Bombardi, R.; Tennekoon, R.N.; de Silva, A.D.; Elbashir, S.M.; Theisen, M.A.; Humphris-Narayanan, E.; Ciaramella, G.; et al. A lipid-encapsulated mRNA encoding a potently neutralizing human monoclonal antibody protects against chikungunya infection. Sci. Immunol. 2019, 4, aaw6647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Filette, M.; Soehle, S.; Ulbert, S.; Richner, J.; Diamond, M.S.; Sinigaglia, A.; Barzon, L.; Roels, S.; Lisziewicz, J.; Lorincz, O.; et al. Vaccination of mice using the West Nile virus E-protein in a DNA prime-protein boost strategy stimulates cell-mediated immunity and protects mice against a lethal challenge. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e87837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nooraei, S.; Bahrulolum, H.; Hoseini, Z.S.; Katalani, C.; Hajizade, A.; Easton, A.J.; Ahmadian, G. Virus-like particles: Preparation, immunogenicity and their roles as nanovaccines and drug nanocarriers. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2021, 19, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krol, E.; Brzuska, G.; Szewczyk, B. Production and Biomedical Application of Flavivirus-like Particles. Trends Biotechnol. 2019, 37, 1202–1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urakami, A.; Ngwe Tun, M.M.; Moi, M.L.; Sakurai, A.; Ishikawa, M.; Kuno, S.; Ueno, R.; Morita, K.; Akahata, W. An Envelope-Modified Tetravalent Dengue Virus-Like-Particle Vaccine Has Implications for Flavivirus Vaccine Design. J. Virol. 2017, 91, 10–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerrero, D.; Cantaert, T.; Misse, D. Aedes Mosquito Salivary Components and Their Effect on the Immune Response to Arboviruses. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 2020, 10, 407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wichit, S.; Diop, F.; Hamel, R.; Talignani, L.; Ferraris, P.; Cornelie, S.; Liegeois, F.; Thomas, F.; Yssel, H.; Misse, D. Aedes Aegypti saliva enhances chikungunya virus replication in human skin fibroblasts via inhibition of the type I interferon signaling pathway. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2017, 55, 68–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, B.S.; Soong, L.; Coffey, L.L.; Stevenson, H.L.; McGee, C.E.; Higgs, S. Aedes aegypti saliva alters leukocyte recruitment and cytokine signaling by antigen-presenting cells during West Nile virus infection. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e11704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, B.S.; Soong, L.; Zeidner, N.S.; Higgs, S. Aedes aegypti salivary gland extracts modulate anti-viral and TH1/TH2 cytokine responses to sindbis virus infection. Viral Immunol. 2004, 17, 565–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lefteri, D.A.; Bryden, S.R.; Pingen, M.; Terry, S.; McCafferty, A.; Beswick, E.F.; Georgiev, G.; Van der Laan, M.; Mastrullo, V.; Campagnolo, P.; et al. Mosquito saliva enhances virus infection through sialokinin-dependent vascular leakage. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2022, 119, e2114309119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fong, S.W.; Kini, R.M.; Ng, L.F.P. Mosquito Saliva Reshapes Alphavirus Infection and Immunopathogenesis. J. Virol. 2018, 92, e01004-17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogt, M.B.; Lahon, A.; Arya, R.P.; Kneubehl, A.R.; Spencer Clinton, J.L.; Paust, S.; Rico-Hesse, R. Mosquito saliva alone has profound effects on the human immune system. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2018, 12, e0006439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerrero, D.; Vo, H.T.M.; Lon, C.; Bohl, J.A.; Nhik, S.; Chea, S.; Man, S.; Sreng, S.; Pacheco, A.R.; Ly, S.; et al. Evaluation of cutaneous immune response in a controlled human in vivo model of mosquito bites. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 7036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demeure, C.E.; Brahimi, K.; Hacini, F.; Marchand, F.; Peronet, R.; Huerre, M.; St-Mezard, P.; Nicolas, J.F.; Brey, P.; Delespesse, G.; et al. Anopheles mosquito bites activate cutaneous mast cells leading to a local inflammatory response and lymph node hyperplasia. J. Immunol. 2005, 174, 3932–3940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Depinay, N.; Hacini, F.; Beghdadi, W.; Peronet, R.; Mecheri, S. Mast cell-dependent down-regulation of antigen-specific immune responses by mosquito bites. J. Immunol. 2006, 176, 4141–4146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manning, J.E.; Oliveira, F.; Coutinho-Abreu, I.V.; Herbert, S.; Meneses, C.; Kamhawi, S.; Baus, H.A.; Han, A.; Czajkowski, L.; Rosas, L.A.; et al. Safety and immunogenicity of a mosquito saliva peptide-based vaccine: A randomised, placebo-controlled, double-blind, phase 1 trial. Lancet 2020, 395, 1998–2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman-Klabanoff, D.J.; Birkhold, M.; Short, M.T.; Wilson, T.R.; Meneses, C.R.; Lacsina, J.R.; Oliveira, F.; Kamhawi, S.; Valenzuela, J.G.; Hunsberger, S.; et al. Safety and immunogenicity of AGS-v PLUS, a mosquito saliva peptide vaccine against arboviral diseases: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled Phase 1 trial. EBioMedicine 2022, 86, 104375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramanathan, A.; Robb, G.B.; Chan, S.H. mRNA capping: Biological functions and applications. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016, 44, 7511–7526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thillier, Y.; Decroly, E.; Morvan, F.; Canard, B.; Vasseur, J.J.; Debart, F. Synthesis of 5’ cap-0 and cap-1 RNAs using solid-phase chemistry coupled with enzymatic methylation by human (guanine-N(7))-methyl transferase. RNA 2012, 18, 856–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kariko, K.; Muramatsu, H.; Welsh, F.A.; Ludwig, J.; Kato, H.; Akira, S.; Weissman, D. Incorporation of pseudouridine into mRNA yields superior nonimmunogenic vector with increased translational capacity and biological stability. Mol. Ther. 2008, 16, 1833–1840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reichmuth, A.M.; Oberli, M.A.; Jaklenec, A.; Langer, R.; Blankschtein, D. mRNA vaccine delivery using lipid nanoparticles. Ther. Deliv. 2016, 7, 319–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maruggi, G.; Zhang, C.; Li, J.; Ulmer, J.B.; Yu, D. mRNA as a Transformative Technology for Vaccine Development to Control Infectious Diseases. Mol. Ther. 2019, 27, 757–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polack, F.P.; Thomas, S.J.; Kitchin, N.; Absalon, J.; Gurtman, A.; Lockhart, S.; Perez, J.L.; Perez Marc, G.; Moreira, E.D.; Zerbini, C.; et al. Safety and Efficacy of the BNT162b2 mRNA Covid-19 Vaccine. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 383, 2603–2615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamb, Y.N. BNT162b2 mRNA COVID-19 Vaccine: First Approval. Drugs 2021, 81, 495–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnee, M.; Vogel, A.B.; Voss, D.; Petsch, B.; Baumhof, P.; Kramps, T.; Stitz, L. An mRNA Vaccine Encoding Rabies Virus Glycoprotein Induces Protection against Lethal Infection in Mice and Correlates of Protection in Adult and Newborn Pigs. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2016, 10, e0004746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alberer, M.; Gnad-Vogt, U.; Hong, H.S.; Mehr, K.T.; Backert, L.; Finak, G.; Gottardo, R.; Bica, M.A.; Garofano, A.; Koch, S.D.; et al. Safety and immunogenicity of a mRNA rabies vaccine in healthy adults: An open-label, non-randomised, prospective, first-in-human phase 1 clinical trial. Lancet 2017, 390, 1511–1520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, C.S.; Jenks, J.A.; Pardi, N.; Goodwin, M.; Roark, H.; Edwards, W.; McLellan, J.S.; Pollara, J.; Weissman, D.; Permar, S.R. Human Cytomegalovirus Glycoprotein B Nucleoside-Modified mRNA Vaccine Elicits Antibody Responses with Greater Durability and Breadth than MF59-Adjuvanted gB Protein Immunization. J. Virol. 2020, 94, 10–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villanueva, M.T. An mRNA universal vaccine for influenza. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2023, 22, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roth, C.; Cantaert, T.; Colas, C.; Prot, M.; Casademont, I.; Levillayer, L.; Thalmensi, J.; Langlade-Demoyen, P.; Gerke, C.; Bahl, K.; et al. A Modified mRNA Vaccine Targeting Immunodominant NS Epitopes Protects Against Dengue Virus Infection in HLA Class I Transgenic Mice. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, C.A.; August, A.; Bart, S.; Booth, P.J.; Knightly, C.; Brasel, T.; Weaver, S.C.; Zhou, H.; Panther, L. A phase 1, randomized, placebo-controlled, dose-ranging study to evaluate the safety and immunogenicity of an mRNA-based chikungunya virus vaccine in healthy adults. Vaccine 2023, 41, 3898–3906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medina-Magues, L.G.; Gergen, J.; Jasny, E.; Petsch, B.; Lopera-Madrid, J.; Medina-Magues, E.S.; Salas-Quinchucua, C.; Osorio, J.E. mRNA Vaccine Protects against Zika Virus. Vaccines 2021, 9, 1464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pardi, N.; Hogan, M.J.; Pelc, R.S.; Muramatsu, H.; Andersen, H.; DeMaso, C.R.; Dowd, K.A.; Sutherland, L.L.; Scearce, R.M.; Parks, R.; et al. Zika virus protection by a single low-dose nucleoside-modified mRNA vaccination. Nature 2017, 543, 248–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Essink, B.; Chu, L.; Seger, W.; Barranco, E.; Le Cam, N.; Bennett, H.; Faughnan, V.; Pajon, R.; Paila, Y.D.; Bollman, B.; et al. The safety and immunogenicity of two Zika virus mRNA vaccine candidates in healthy flavivirus baseline seropositive and seronegative adults: The results of two randomised, placebo-controlled, dose-ranging, phase 1 clinical trials. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2023, 23, 621–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wollner, C.J.; Richner, M.; Hassert, M.A.; Pinto, A.K.; Brien, J.D.; Richner, J.M. A Dengue Virus Serotype 1 mRNA-LNP Vaccine Elicits Protective Immune Responses. J. Virol. 2021, 95, 10–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, N.P. Moderna Scraps Lead mRNA Chikungunya Candidate after Phase 1, Slowing Push Beyond Prophylactic Vaccines. Available online: https://www.fiercebiotech.com/biotech/moderna-scraps-lead-mrna-antibody-candidate-after-phase-1-slowing-push-beyond-prophylactic (accessed on 21 November 2023).

- Forthal, D.N.; Moog, C. Fc receptor-mediated antiviral antibodies. Curr. Opin. HIV AIDS 2009, 4, 388–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawant, J.; Patil, A.; Kurle, S. A Review: Understanding Molecular Mechanisms of Antibody-Dependent Enhancement in Viral Infections. Vaccines 2023, 11, 1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katzelnick, L.C.; Gresh, L.; Halloran, M.E.; Mercado, J.C.; Kuan, G.; Gordon, A.; Balmaseda, A.; Harris, E. Antibody-dependent enhancement of severe dengue disease in humans. Science 2017, 358, 929–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Endale, A.; Medhin, G.; Darfiro, K.; Kebede, N.; Legesse, M. Magnitude of Antibody Cross-Reactivity in Medically Important Mosquito-Borne Flaviviruses: A Systematic Review. Infect. Drug Resist. 2021, 14, 4291–4299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, W.C.; Akey, D.L.; Konwerski, J.R.; Tarrasch, J.T.; Skiniotis, G.; Kuhn, R.J.; Smith, J.L. Extended surface for membrane association in Zika virus NS1 structure. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2016, 23, 865–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akey, D.L.; Brown, W.C.; Dutta, S.; Konwerski, J.; Jose, J.; Jurkiw, T.J.; DelProposto, J.; Ogata, C.M.; Skiniotis, G.; Kuhn, R.J.; et al. Flavivirus NS1 structures reveal surfaces for associations with membranes and the immune system. Science 2014, 343, 881–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barnard, T.R.; Abram, Q.H.; Lin, Q.F.; Wang, A.B.; Sagan, S.M. Molecular Determinants of Flavivirus Virion Assembly. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2021, 46, 378–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bailey, M.J.; Broecker, F.; Duehr, J.; Arumemi, F.; Krammer, F.; Palese, P.; Tan, G.S. Antibodies Elicited by an NS1-Based Vaccine Protect Mice against Zika Virus. mBio 2019, 10, e02861-18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fox, J.M.; Roy, V.; Gunn, B.M.; Huang, L.; Edeling, M.A.; Mack, M.; Fremont, D.H.; Doranz, B.J.; Johnson, S.; Alter, G.; et al. Optimal therapeutic activity of monoclonal antibodies against chikungunya virus requires Fc-FcgammaR interaction on monocytes. Sci. Immunol. 2019, 4, eaav5062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fric, J.; Bertin-Maghit, S.; Wang, C.I.; Nardin, A.; Warter, L. Use of human monoclonal antibodies to treat Chikungunya virus infection. J. Infect. Dis. 2013, 207, 319–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, J.; Liss, N.M.; Chen, D.H.; Liao, M.; Fox, J.M.; Shimak, R.M.; Fong, R.H.; Chafets, D.; Bakkour, S.; Keating, S.; et al. Neutralizing Monoclonal Antibodies Block Chikungunya Virus Entry and Release by Targeting an Epitope Critical to Viral Pathogenesis. Cell Rep. 2015, 13, 2553–2564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fox, J.M.; Roy, V.; Gunn, B.M.; Bolton, G.R.; Fremont, D.H.; Alter, G.; Diamond, M.S.; Boesch, A.W. Enhancing the therapeutic activity of hyperimmune IgG against chikungunya virus using FcgammaRIIIa affinity chromatography. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1153108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Achee, N.L.; Grieco, J.P.; Vatandoost, H.; Seixas, G.; Pinto, J.; Ching-Ng, L.; Martins, A.J.; Juntarajumnong, W.; Corbel, V.; Gouagna, C.; et al. Alternative strategies for mosquito-borne arbovirus control. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2019, 13, e0006822. [Google Scholar]

- Dusfour, I.; Vontas, J.; David, J.P.; Weetman, D.; Fonseca, D.M.; Corbel, V.; Raghavendra, K.; Coulibaly, M.B.; Martins, A.J.; Kasai, S.; et al. Management of insecticide resistance in the major Aedes vectors of arboviruses: Advances and challenges. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2019, 13, e0007615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasgon, J. Population replacement strategies for controlling vector populations and the use of Wolbachia pipientis for genetic drive. J. Vis. Exp. 2007, 5, 225. [Google Scholar]

- Rasgon, J.L. Dengue fever: Mosquitoes attacked from within. Nature 2011, 476, 407–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Yu, J.; Li, J. A Mosquito Population Suppression Model by Releasing Wolbachia-Infected Males. Bull. Math. Biol. 2022, 84, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, S.C.; Masri, R.A.; Akbari, O.S. Advances and challenges in synthetic biology for mosquito control. Trends Parasitol. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Yang, T.; Bui, M.; Gamez, S.; Wise, T.; Kandul, N.P.; Liu, J.; Alcantara, L.; Lee, H.; Edula, J.R.; et al. Suppressing mosquito populations with precision guided sterile males. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 5374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenharo, M. Dengue is spreading. Can new vaccines and antivirals halt its rise? Nature 2023, 623, 470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velez, I.D.; Tanamas, S.K.; Arbelaez, M.P.; Kutcher, S.C.; Duque, S.L.; Uribe, A.; Zuluaga, L.; Martinez, L.; Patino, A.C.; Barajas, J.; et al. Reduced dengue incidence following city-wide wMel Wolbachia mosquito releases throughout three Colombian cities: Interrupted time series analysis and a prospective case-control study. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2023, 17, e0011713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CDC Mosquitoes with Wolbachia for Reducing Numbers of Aedes aegypti Mosquitoes. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/mosquitoes/mosquito-control/community/emerging-methods/wolbachia.html (accessed on 17 December 2023).

- Meghani, Z. Regulation of genetically engineered (GE) mosquitoes as a public health tool: A public health ethics analysis. Global Health 2022, 18, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrett, A.D.T. Yellow fever live attenuated vaccine: A very successful live attenuated vaccine but still we have problems controlling the disease. Vaccine 2017, 35, 5951–5955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoke, C.H.; Nisalak, A.; Sangawhipa, N.; Jatanasen, S.; Laorakapongse, T.; Innis, B.L.; Kotchasenee, S.; Gingrich, J.B.; Latendresse, J.; Fukai, K.; et al. Protection against Japanese encephalitis by inactivated vaccines. N. Engl. J. Med. 1988, 319, 608–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yun, S.I.; Lee, Y.M. Japanese encephalitis: The virus and vaccines. Hum. Vaccin. Immunother. 2014, 10, 263–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jia, L.; Wang, Z.; Yu, Y. Protection of SA14-14-2 live attenuated Japanese encephalitis vaccine against the wild-type JE viruses. Chin. Med. J. 2003, 116, 941–943. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Erra, E.O.; Kantele, A. The Vero cell-derived, inactivated, SA14-14-2 strain-based vaccine (Ixiaro) for prevention of Japanese encephalitis. Expert. Rev. Vaccines 2015, 14, 1167–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aguiar, M.; Stollenwerk, N.; Halstead, S.B. The risks behind Dengvaxia recommendation. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2016, 16, 882–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- FDA FDA Approves First Vaccine to Prevent Disease Caused by Chikungunya Virus. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-approves-first-vaccine-prevent-disease-caused-chikungunya-virus (accessed on 21 November 2023).

- Ma, H.Y.; Lai, C.C.; Chiu, N.C.; Lee, P.I. Adverse events following immunization with the live-attenuated recombinant Japanese encephalitis vaccine (IMOJEV(R)) in Taiwan, 2017–2018. Vaccine 2020, 38, 5219–5222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kitchener, S. Viscerotropic and neurotropic disease following vaccination with the 17D yellow fever vaccine, ARILVAX. Vaccine 2004, 22, 2103–2105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callaway, E. Scores of coronavirus vaccines are in competition—How will scientists choose the best? Nature 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Vaccine Name | Target Virus | Encoded Proteins | Nucleoside Modification | Delivery Method | Animal Model | Outcome | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mRNA-1325 | ZIKV | prM/E | No | LNP | Mice | Complete protection, reduction in viral titers and fetal resorption | [94] |

| Nucleoside-modified RNA vaccine | ZIKV | prM/ENV | Yes | LNP | Macaques | Potent neutralizing antibodies, protection, prevention of congenital transmission and fetal abnormalities | [93] |

| mRNA-LNP | ZIKV | prM/E | No | LNP | Mice, Macaques | Host-protective antibodies, sterilizing immunity, prevention of vertical transmission | [92] |

| DENV1-NS | DENV | NS3, NS4B, NS5 | No | LNP | Mice | Potent T cell response, reduction in DENV1 infection | [90] |

| prM/E mRNA-LNP | DENV | prM/E | Yes | LNP | Mice | Neutralizing antibodies, CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, increased ADE levels | [95] |

| mRNA-1944 | CHIKV | CHKV-24 monoclonal antibody | Yes | LNP | Mice | Potent neutralizing antibody, prevention of viremia | [96] |

| mRNA-1388 | CHIKV | prM/E | Yes | LNP | Mice, Macaques | Potent neutralizing antibody, protection against challenge | [91] |

| Vaccine Platform | Limitations |

|---|---|

| Insect-specific viruses (ISVs) | Safety and efficacy require further research. |

| DNA vaccine | Limited immune response in humans. Delivery issues, difficulties in effective DNA delivery to host cells. Potential stability issues and genomic integration risks. Risk of triggering anti-DNA antibodies, causing autoimmune reactions. Challenging regulatory approval. |

| Nanoparticle-based vaccines | Low stability, structural heterogeneity, potential immunogenicity, high toxicity, and off-target activity. Challenges in efficient delivery to target sites. |

| Salivary protein vaccines | Ongoing research to understand biology. Vaccines derived from one mosquito species’ saliva might not be effective against different mosquito species. The approach will be ineffective for arboviral infections acquired via sexual or blood transfusion. Potential issues with allergic responses or negative effects from exposure to saliva proteins. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pujhari, S. Recent Advances in Arboviral Vaccines: Emerging Platforms and Promising Innovations. Biologics 2024, 4, 1-16. https://doi.org/10.3390/biologics4010001

Pujhari S. Recent Advances in Arboviral Vaccines: Emerging Platforms and Promising Innovations. Biologics. 2024; 4(1):1-16. https://doi.org/10.3390/biologics4010001

Chicago/Turabian StylePujhari, Sujit. 2024. "Recent Advances in Arboviral Vaccines: Emerging Platforms and Promising Innovations" Biologics 4, no. 1: 1-16. https://doi.org/10.3390/biologics4010001

APA StylePujhari, S. (2024). Recent Advances in Arboviral Vaccines: Emerging Platforms and Promising Innovations. Biologics, 4(1), 1-16. https://doi.org/10.3390/biologics4010001