Exploring the Electronic Landscape of Two-Dimensional Tin Monoxide: Layer Thickness and Crystallographic Symmetry Effects

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussions

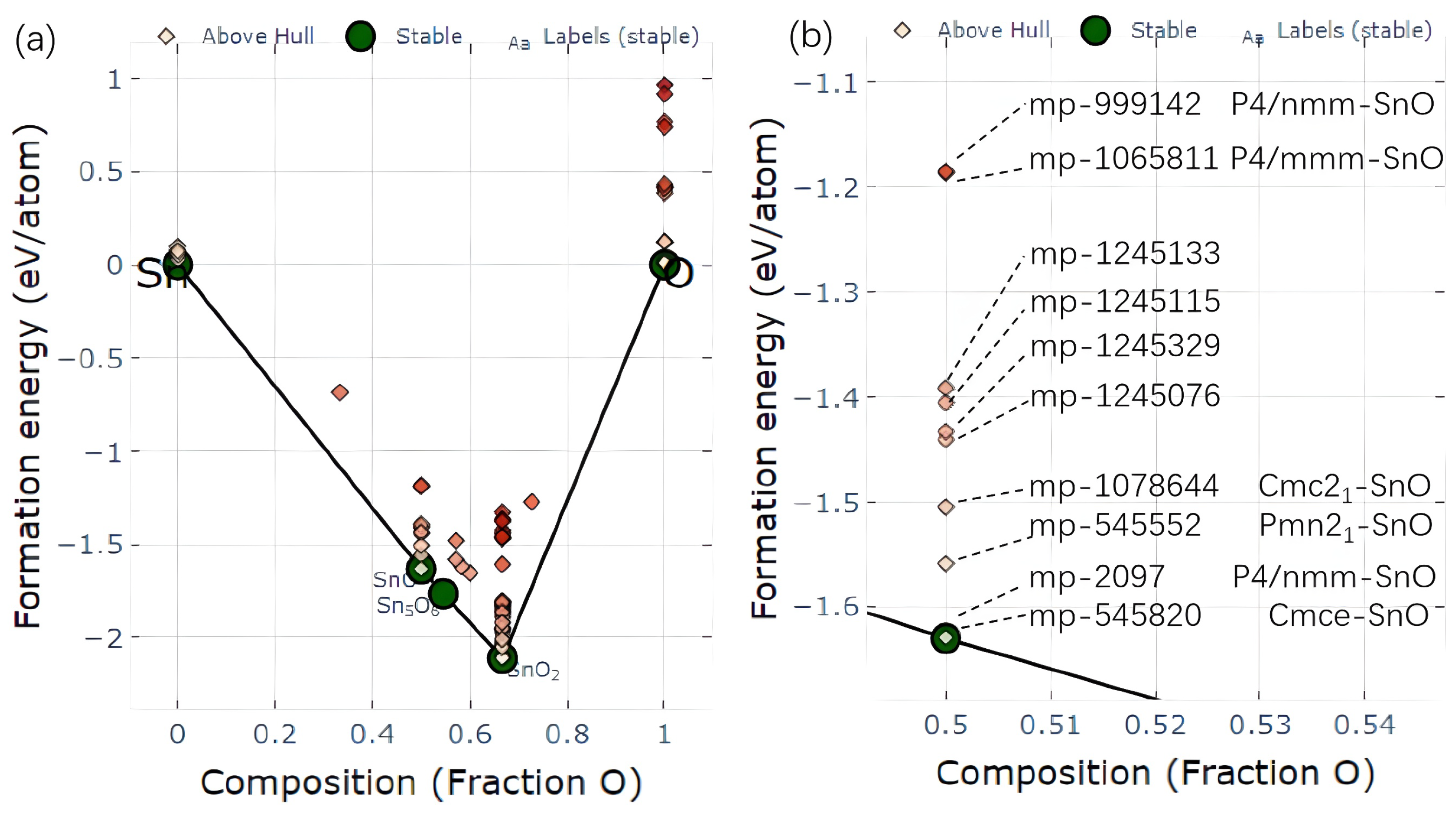

2.1. Structural Survey of SnO Polymorphs

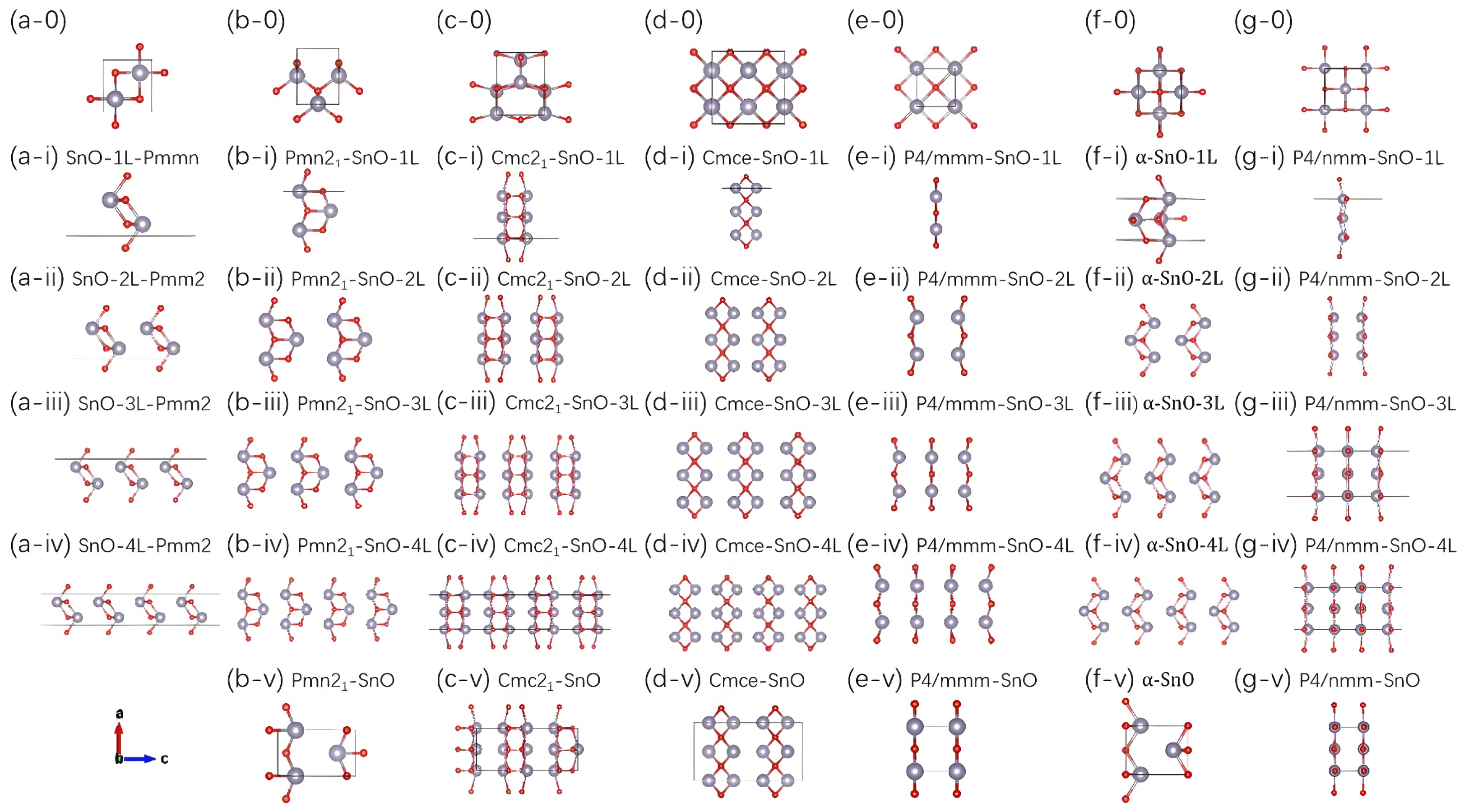

2.2. Crystal Structures of SnO Polymorphs and Their Layered Derivatives

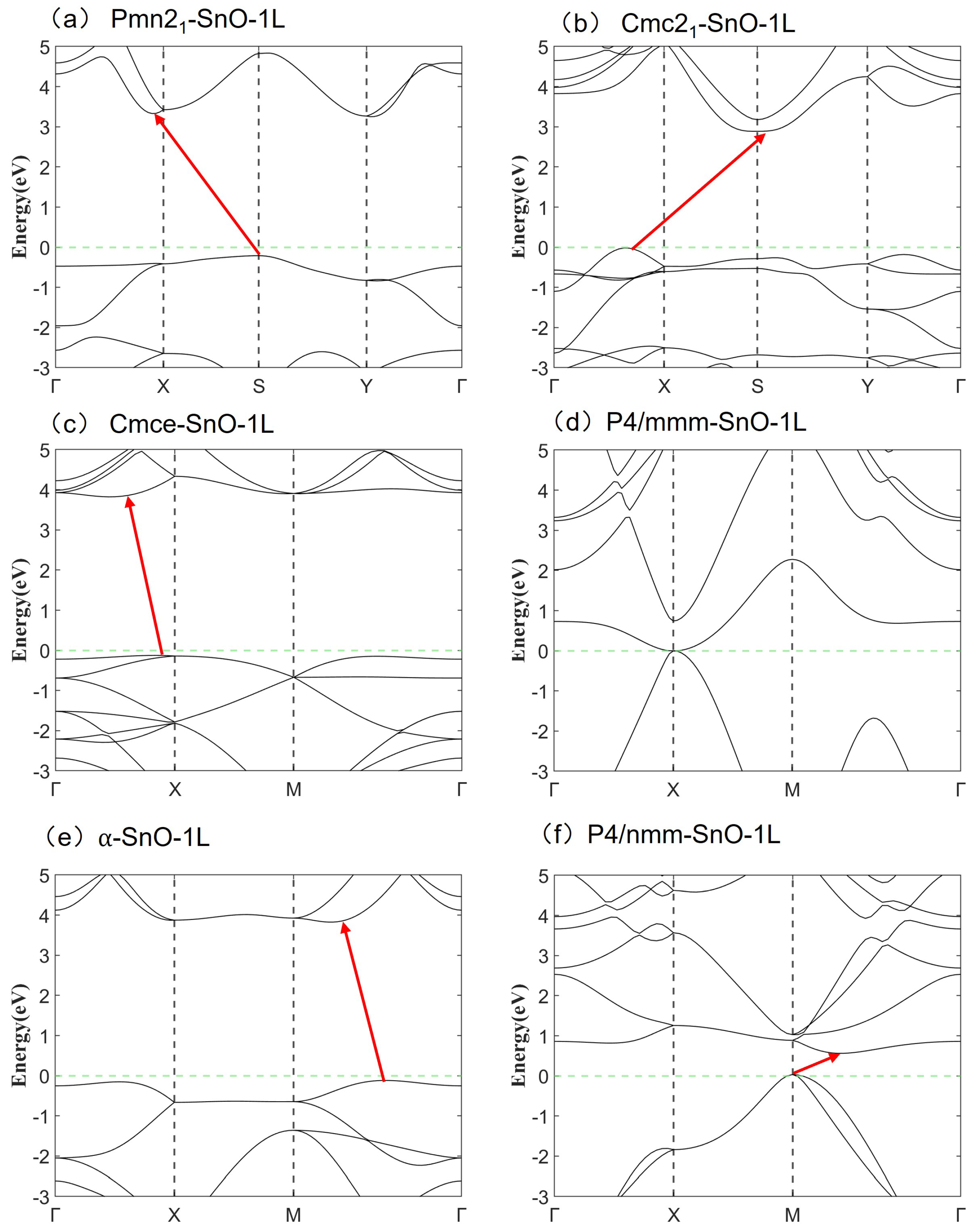

2.3. Electronic Structure and Stability

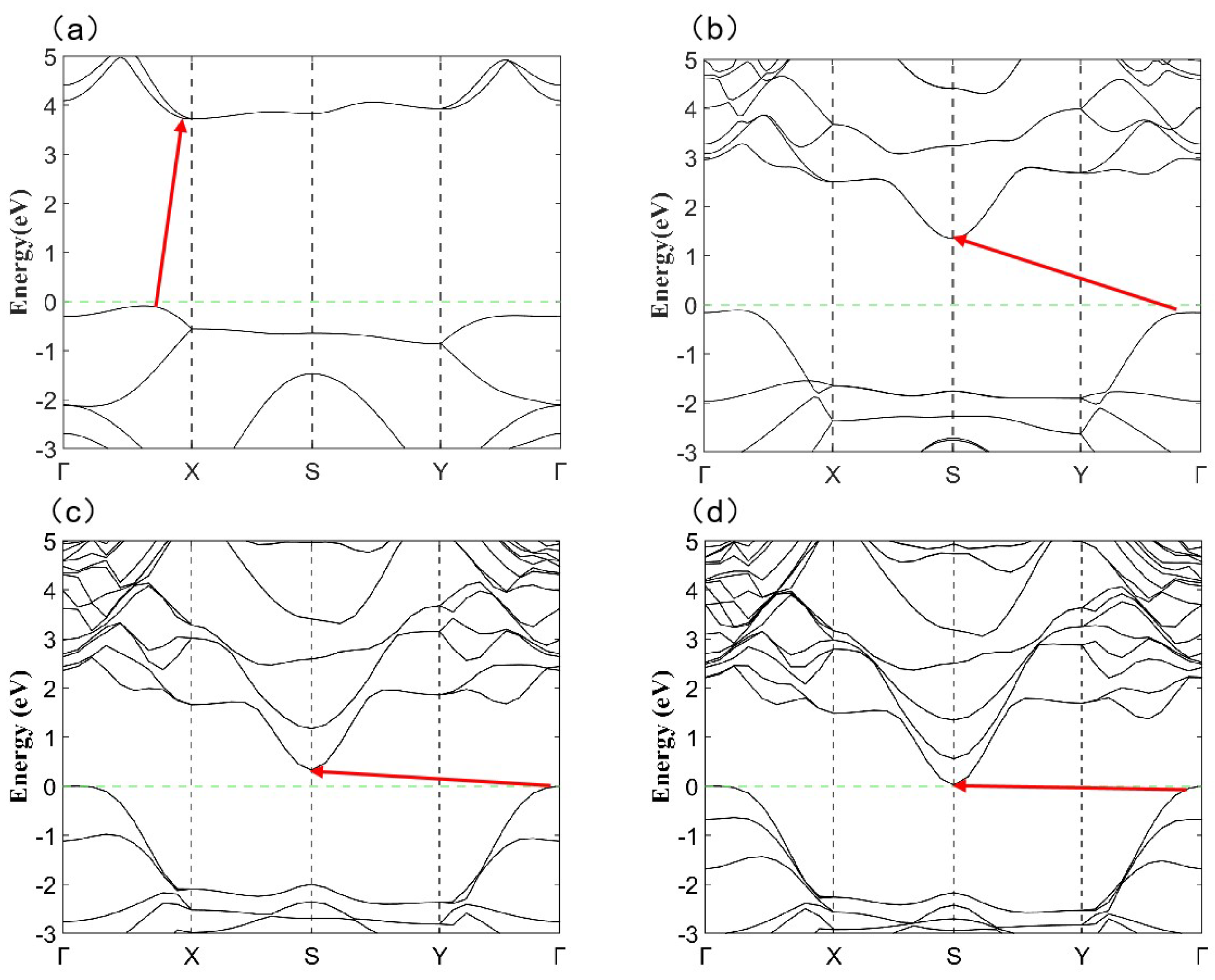

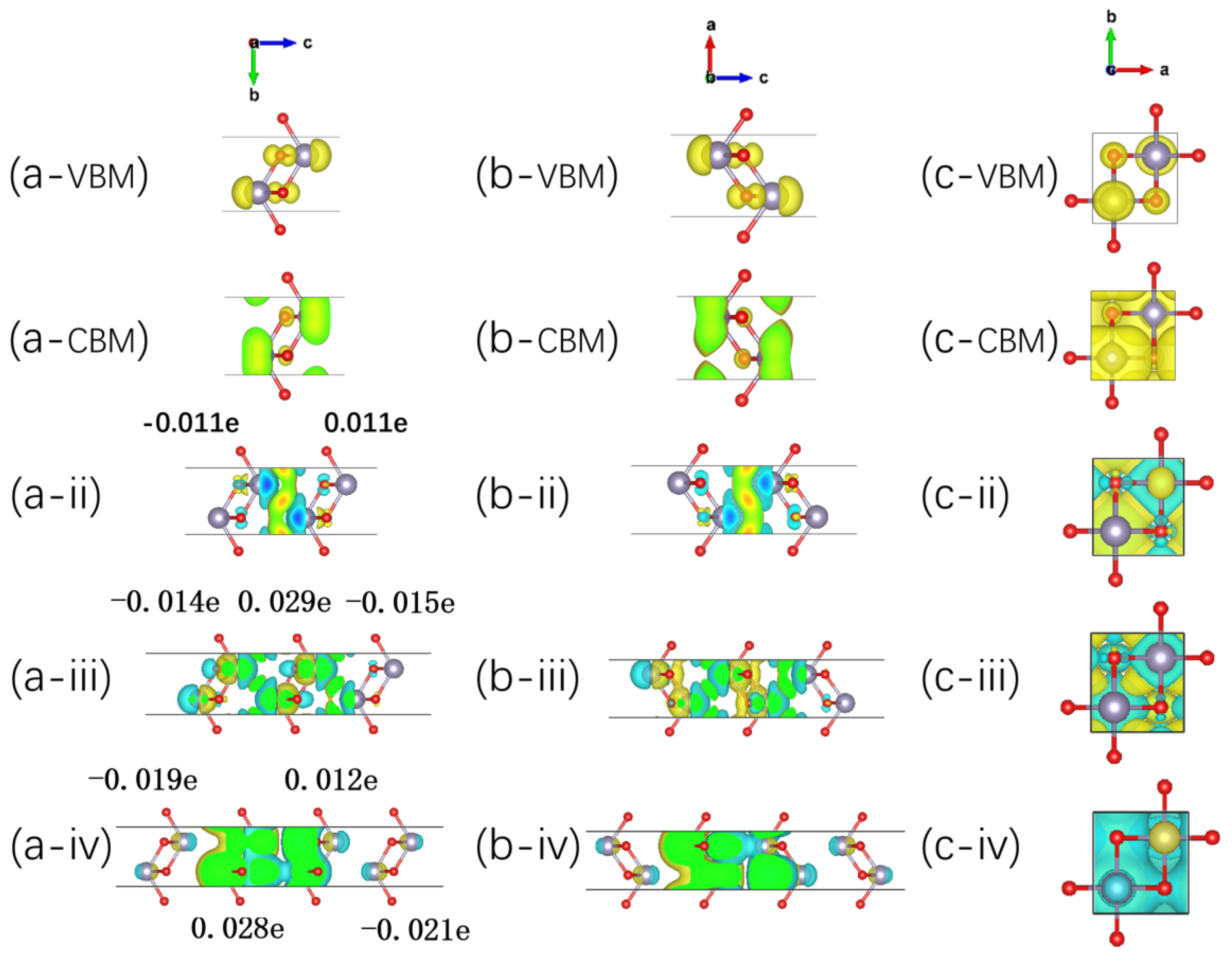

2.4. Layer-Dependent Electronic Evolution in SnO-nL-Pmmn

3. Methodology

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Grigorieva, V.; Firsov, A. Electric field in atomically thin carbon films. Science 2004, 205, 666–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castro Neto, A.H.; Guinea, F.; Peres, N.M.; Novoselov, K.S.; Geim, A.K. The electronic properties of graphene. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2009, 81, 109–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodgers, P. Nanoscience and Technology: A Collection of Reviews from Nature Journals; World Scientific: Singapore, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Kara, A.; Enriquez, H.; Seitsonen, A.P.; Voon, L.L.Y.; Vizzini, S.; Aufray, B.; Oughaddou, H. A review on silicene—new candidate for electronics. Surf. Sci. Rep. 2012, 67, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cahangirov, S.; Topsakal, M.; Aktürk, E.; Şahin, H.; Ciraci, S. Two-and one-dimensional honeycomb structures of silicon and germanium. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2009, 102, 236804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Feng, Y.; Wang, F.; Yang, Z.; Wang, J. Two dimensional hexagonal boron nitride (2D-hBN): Synthesis, properties and applications. J. Mater. Chem. C 2017, 5, 11992–12022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Zhou, J.; Wang, Q.; Chen, X.; Kawazoe, Y.; Jena, P. Penta-graphene: A new carbon allotrope. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, 2372–2377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzeli, S.; Ovchinnikov, D.; Pasquier, D.; Yazyev, O.V.; Kis, A. 2D transition metal dichalcogenides. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2017, 2, 17033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ataca, C.; Sahin, H.; Ciraci, S. Stable, single-layer MX2 transition-metal oxides and dichalcogenides in a honeycomb-like structure. J. Phys. Chem. C 2012, 116, 8983–8999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, T.; Song, T.T.; Callsen, M.; Zhou, J.; Chai, J.W.; Feng, Y.P.; Wang, S.J.; Yang, M. Atomically thin 2D transition metal oxides: Structural reconstruction, interaction with substrates, and potential applications. Adv. Mater. Interfaces 2019, 6, 1801160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, T.H.; Oh, Y.; Kim, H.; Yoon, H. Exfoliation of 2D materials for energy and environmental applications. Chem.- Eur. J. 2020, 26, 6360–6401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilá, R.; Momeni, K.; Wang, Q.; Bersch, B.; Lu, N.; Kim, M.; Chen, L.; Robinson, J. Bottom-up synthesis of vertically oriented two-dimensional materials. 2D Mater. 2016, 3, 041003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mounet, N.; Gibertini, M.; Schwaller, P.; Campi, D.; Merkys, A.; Marrazzo, A.; Sohier, T.; Castelli, I.E.; Cepellotti, A.; Pizzi, G.; et al. Two-dimensional materials from high-throughput computational exfoliation of experimentally known compounds. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2018, 13, 246–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, B.; Wang, Z.; Hung, N.T.; Oganov, A.R.; Yang, T.; Saito, R.; Zhang, Z. New two-dimensional phase of tin chalcogenides: Candidates for high-performance thermoelectric materials. Phys. Rev. Mater. 2019, 3, 013405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mannix, A.J.; Zhou, X.F.; Kiraly, B.; Wood, J.D.; Alducin, D.; Myers, B.D.; Liu, X.; Fisher, B.L.; Santiago, U.; Guest, J.R.; et al. Synthesis of borophenes: Anisotropic, two-dimensional boron polymorphs. Science 2015, 350, 1513–1516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph, T.; Ghorbani-Asl, M.; Kvashnin, A.; Larionov, K.; Popov, Z.; Sorokin, P.; Krasheninnikov, A.V. Nonstoichiometric phases of two-dimensional transition-metal dichalcogenides: From chalcogen vacancies to pure metal membranes. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2019, 10, 6492–6498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puthirath Balan, A.; Radhakrishnan, S.; Woellner, C.F.; Sinha, S.K.; Deng, L.; Reyes, C.d.l.; Rao, B.M.; Paulose, M.; Neupane, R.; Apte, A.; et al. Exfoliation of a non-van der Waals material from iron ore hematite. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2018, 13, 602–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Umezawa, N.; Hosono, H. Mixed valence tin oxides as novel van der Waals materials: Theoretical predictions and potential applications. Adv. Energy Mater. 2016, 6, 1501190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mubeen, A.; Majid, A.; Alkhedher, M.; Tag-ElDin, E.M.; Bulut, N. Structural and electronic properties of SnO downscaled to monolayer. Materials 2022, 15, 5578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Schlom, D.; Datta, S.; Cho, K. Interlayer engineering of band gap and hole mobility in p-type oxide SnO. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2022, 14, 25670–25679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogo, Y.; Hiramatsu, H.; Nomura, K.; Yanagi, H.; Kamiya, T.; Hirano, M.; Hosono, H. p-channel thin-film transistor using p-type oxide semiconductor, SnO. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2008, 93, 032113. [Google Scholar]

- Wan, W.; Ge, Y.; Liu, Y. Strong phonon anharmonicity and low thermal conductivity of monolayer tin oxides driven by lone-pair electrons. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2019, 114, 031901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahamana, M.M.; Momin, M.A.; Majumdar, A.; Rahman, M.J. DFT Based LDA Study on Tailoring the Optical and Electrical Properties of SnO and In-Doped SnO. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2307.03843. [Google Scholar]

- Reuter, H. Red and blue-black tin monoxide, sno: Pitfalls, challenges, and helpful tools in crystal structure determination of low-intensity datasets from microcrystals. Crystals 2023, 13, 1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, G.W. The origin of the electron distribution in SnO. J. Chem. Phys. 2001, 114, 758–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunanyan, A.A.; Aroutiounian, V.M.; Zakaryan, H.A. Computational Search and Stability Analysis of Two-Dimensional Tin Oxides. J. Phys. Chem. C 2022, 126, 4647–4654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, Z.W.; Hsu, H.H.; Zheng, Z.W.; Cheng, C.H. Progress and challenges in p-type oxide-based thin film transistors. Nanotechnol. Rev. 2019, 8, 422–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, L.T.; Makov, G. High-pressure phases of SNO and PBO: A density functional theory combined with an evolutionary algorithm approach. Materials 2021, 14, 6552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, K.; Ji, J.; Gong, W.; Ding, L.; Li, J.; Li, P.; Li, B.; Geng, F. Mechanical cleavage of non-van der Waals structures towards two-dimensional crystals. Nat. Synth. 2023, 2, 58–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kripalani, D.R.; Sun, P.P.; Lin, P.; Xue, M.; Zhou, K. Strain-driven superplasticity of ultrathin tin (II) oxide films and the modulation of their electronic properties: A first-principles study. Phys. Rev. B 2019, 100, 214112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daeneke, T.; Atkin, P.; Orrell-Trigg, R.; Zavabeti, A.; Ahmed, T.; Walia, S.; Liu, M.; Tachibana, Y.; Javaid, M.; Greentree, A.D.; et al. Wafer-scale synthesis of semiconducting SnO monolayers from interfacial oxide layers of metallic liquid tin. ACS Nano 2017, 11, 10974–10983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Köhler, J.; Tong, J.; Dinnebier, R.; Simon, A. Crystal structure and electronic structure of red SnO. Z. Für Anorg. Und Allg. Chem. 2012, 638, 1970–1975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wanzhong, L.; Jian, S.; Chong, D. Layer-dependent electronic and optical properties of tin monoxide: A potential candidate in photovoltaic applications. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2022, 24, 7611–7616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, A.; Ong, S.P.; Hautier, G.; Chen, W.; Richards, W.D.; Dacek, S.; Cholia, S.; Gunter, D.; Skinner, D.; Ceder, G.; et al. Commentary: The Materials Project: A materials genome approach to accelerating materials innovation. APL Mater. 2013, 1, 011002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartel, C.J. Review of computational approaches to predict the thermodynamic stability of inorganic solids. J. Mater. Sci. 2022, 57, 10475–10498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Wang, J.; Blatov, V.A.; Gong, Y.; Umezawa, N.; Tada, T.; Hosono, H.; Oganov, A.R. Crystal and electronic structure engineering of tin monoxide by external pressure. J. Adv. Ceram. 2021, 10, 565–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, V.; Tang, G.; Liu, Y.C.; Wang, R.T.; Mizuseki, H.; Kawazoe, Y.; Nara, J.; Geng, W.T. High-throughput computational screening of two-dimensional semiconductors. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2022, 13, 11581–11594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohn, W.; Sham, L.J. Self-consistent equations including exchange and correlation effects. Phys. Rev. 1965, 140, A1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kresse, G.; Furthmüller, J. Efficient iterative schemes for ab initio total-energy calculations using a plane-wave basis set. Phys. Rev. B 1996, 54, 11169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blöchl, P.E. Projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B 1994, 50, 17953–17979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perdew, J.P.; Burke, K.; Ernzerhof, M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1996, 77, 3865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heyd, J.; Scuseria, G.E.; Ernzerhof, M. Hybrid functionals based on a screened Coulomb potential. J. Chem. Phys. 2003, 118, 8207–8215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimme, S. Semiempirical GGA-type density functional constructed with a long-range dispersion correction. J. Comput. Chem. 2006, 27, 1787–1799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grimme, S.; Ehrlich, S.; Goerigk, L. Effect of the damping function in dispersion corrected density functional theory. J. Comput. Chem. 2011, 32, 1456–1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smidstrup, S.; Markussen, T.; Vancraeyveld, P.; Wellendorff, J.; Schneider, J.; Gunst, T.; Verstichel, B.; Stradi, D.; Khomyakov, P.A.; Vej-Hansen, U.G.; et al. QuantumATK: An integrated platform of electronic and atomic-scale modelling tools. J. Physics Condens. Matter 2019, 32, 15901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Orthorhombic | Tetragonal | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crystal | Notation | Pmn21-SnO | Cmc21-SnO | Cmce-SnO | P4/mmm-SnO | -SnO | P4/nmm-SnO |

| International symbol | Pmn21 | Cmc21 | Cmce | P4/mmm | P4/nmm | P4/nmm | |

| Space group number | 31 | 36 | 64 | 123 | 129 | 129 | |

| Material ID | mp-545552 | mp-1078644 | mp-545820 | mp-1065811 | mp-2097 | mp-999142 | |

| Wyckoff position for Sn2+ | 2a | 2a | 4f | 1a | 2c | 2a | |

| Experimental realization | Yes; SnO at high pressure | Yes Red SnO | No | No | Yes; Black-blue SnO | No | |

| Monolayer | SnO-1L-Pmmn (Pmmn; No. 59) | Pmn21-SnO-1L (Pmn21; No. 31) | Cmc21-SnO-1L * (Cm; No. 8) | Cmce-SnO-1L (Aem2; No. 39) | P4/mmm-SnO-1L (P4/mmm; No. 123) | -SnO-1L (P4/nmm; No. 129) | P4/nmm-SnO-1L (P4/nmm; No. 129) |

| Bilayer | SnO-2L-Pmm2 (Pmm2; No. 25) | Pmn21-SnO-2L (Pmn21; No. 31) | Cmc21-SnO-2L * (Cm; No. 8) | Cmce-SnO-2L (Aem2; No. 39) | P4/mmm-SnO-2L (P4/mmm; No. 123) | -SnO-2L (P4/nmm; No. 129) | P4/nmm-SnO-2L (P4/nmm; No. 129) |

| Trilayer | SnO-3L-Pmm2 (Pmm2; No. 25) | Pmn21-SnO-3L * (Pm; No. 6) | Cmc21-SnO-3L * (Cm; No. 8) | Cmce-SnO-3L * (Cm; No. 8) | P4/mmm-SnO-3L (P4/mmm; No. 123) | -SnO-3L (P4mm; No. 99) | P4/nmm-SnO-3L (P4mm; No. 99) |

| Tetralayer | SnO-4L-Pmm2 (Pmm2; No. 25) | Pmn21-SnO-4L * (Pm; No. 6) | Cmc21-SnO-4L * (Cm; No. 8) | Cmce-SnO-4L * (Cm; No. 8) | P4/mmm-SnO-4L (P4/mmm; No. 123) | -SnO-4L (P4mm; No. 99) | P4/nmm-SnO-4L (P4mm; No. 99) |

| Layers | Crystal | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Notation | -SnO-1L | -SnO-2L | -SnO-3L | -SnO-4L | -SnO | |

| Lattice | a(Å) = b(Å) | 3.76511 | 3.77593 | 3.78001 | 3.78060 | 3.84082 |

| c(Å) | 15 | 25 | 35 | 45 | 4.91413 | |

| Intra-layer | Sn-O(Å) | 2.24114 | 2.24057 | 2.24211 | 2.24192 | 2.25009 |

| Sn-Sn(Å) | 3.60594 | 3.59585 | 3.59502 | 3.59495 | 3.84082 | |

| O-O(Å) | 2.66234 | 2.66999 | 2.67287 | 2.67329 | 2.71587 | |

| Interlayer | O-O(Å) | - | 4.96604 | 4.91053 | 4.90900 | 4.91413 |

| Sn-Sn(Å) | - | 4.97051 | 4.92445 | 4.92280 | 3.73840 | |

| Electronic properties | Band character | Indirect | Indirect | Indirect | Indirect | Indirect |

| PBE bandgap (eV) | 3.0144 | 0.9572 | 0.3686 | 0.1432 | 0.04 | |

| HSE06 bandgap (eV) | 3.9430 | 1.5290 | 0.9391 | 0.1440 | 0.4818 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Huang, Z.; Wang, X.; Deng, X.; Deng, L.; Bo, M.; Yao, C.; Lu, H.; Long, G. Exploring the Electronic Landscape of Two-Dimensional Tin Monoxide: Layer Thickness and Crystallographic Symmetry Effects. Surfaces 2026, 9, 8. https://doi.org/10.3390/surfaces9010008

Huang Z, Wang X, Deng X, Deng L, Bo M, Yao C, Lu H, Long G. Exploring the Electronic Landscape of Two-Dimensional Tin Monoxide: Layer Thickness and Crystallographic Symmetry Effects. Surfaces. 2026; 9(1):8. https://doi.org/10.3390/surfaces9010008

Chicago/Turabian StyleHuang, Zhongkai, Xinyu Wang, Xiaodong Deng, Liang Deng, Maolin Bo, Chuang Yao, Haolin Lu, and Guankui Long. 2026. "Exploring the Electronic Landscape of Two-Dimensional Tin Monoxide: Layer Thickness and Crystallographic Symmetry Effects" Surfaces 9, no. 1: 8. https://doi.org/10.3390/surfaces9010008

APA StyleHuang, Z., Wang, X., Deng, X., Deng, L., Bo, M., Yao, C., Lu, H., & Long, G. (2026). Exploring the Electronic Landscape of Two-Dimensional Tin Monoxide: Layer Thickness and Crystallographic Symmetry Effects. Surfaces, 9(1), 8. https://doi.org/10.3390/surfaces9010008