Abstract

Firms engage in forecasting and foresight activities to predict the future or explore possible future states of the business environment in order to pre-empt and shape it (corporate foresight). Similarly, the dynamic capabilities approach addresses relevant firm capabilities to adapt to fast change in an environment that threatens a firm’s competitiveness and survival. However, despite these conceptual similarities, their relationship remains opaque. To close this gap, we conduct qualitative interviews with foresight experts as an exploratory study. Our results show that foresight and dynamic capabilities aim at an organizational renewal to meet future challenges. Foresight can be regarded as a specific activity that corresponds with the sensing process of dynamic capabilities. The experts disagree about the relationship between foresight and sensing and see no direct links with transformation. However, foresight can better inform post-sensing activities and, therefore, indirectly contribute to the adequate reconfiguration of the resource base, an increased innovativeness, and firm performance.

1. Introduction

Firms are competing in a so-called VUCA business environment which is characterized by high degrees of volatility, uncertainty, complexity, and ambiguity [,] as well as hypercompetition [,]. Discontinuities caused by the omnipresent digitization in most industries [,,,,,,,] but also by unforeseeable events such as the COVID-19 crisis [,] challenge firms existentially. Adapting to these changing conditions by being agile determines the success of the company [,].

Several management concepts provide specific lenses, tools, and techniques which can help firms survive and better perform under such conditions. Among them, two predominant ones are corporate foresight (CF) and the dynamic capability (DC) approach. CF explores possible future scenarios to cope with uncertainty [,,,,]. In that sense, it exceeds forecasting activities which usually aim at predicting the most probable future []. Such strategic intelligence is the basis for informed decision making and increased innovativeness [,] to create a competitive advantage [] and increase profitability [].

Similarly, DCs address the temporality of competitive advantages based on an outdating resource base that has to be renewed permanently []. More generally, DCs are a firm’s capabilities to adapt to a changing business environment in order to renew competitive advantages [,,].

While considerable research has been carried out on both concepts, the joint analysis of CF and DC is under-explored. Despite the obvious similarities in the problems they address and in their general logic, the two concepts surprisingly seem to remain almost separated in scholarly literature. Hardly any scientific paper mentions both concepts simultaneously. As an exception, Heger and Boman argue that the DC approach and CF have in common that they try to incorporate external sources []. Even though the authors integrate both concepts, they do not provide a systematic analysis of how both concepts are related. Rhisiart et al. find that a firm’s engagement in scenario planning can strengthen parts of DCs []. Fergnani argues that CF is a future-oriented firm capability which can enhance the DC framework []. Schwarz et al. conceptualize corporate foresight trainings as a microfoundation of dynamic capabilities []. Haarhaus and Liening consider foresight as an important antecedent of firms’ dynamic capabilities, fostering strategic flexibility and decision rationality [].

Therefore, systematic research on the relationships between CF and DCs is scarce. We address this research gap with our exploratory study that aims at a better understanding of the links between both concepts, by conducting qualitative interviews with foresight experts. In the absence of prior empirical research, we chose a qualitative research design to generate propositions rather than testing hypotheses [,].

Our results show that both concepts aim at an organization’s renewal to meet future challenges. CF can be regarded as a specific activity that corresponds with the sensing process of DCs. The experts disagree about the relationship between CF and seizing and see no direct links between CF and transformation. However, CF can better inform post-sensing DC activities and, therefore, indirectly contribute to the adequate reconfiguration of the resource base, an increased innovativeness, and firm performance.

Our findings contribute to both CF and DC research by linking both fields and deepening the understanding of their relationships. DC research can benefit from the in-depth knowledge about foresight processes and practices. Besides these theoretical contributions, the results can help firms to better integrate their strategic intelligence with pursued change processes.

The paper is structured into three main sections. In the second section, a theoretical overview of CF and DCs is presented. However, we deliberately dispensed with a thorough literature review because, in accordance, with the qualitative research setting, we wanted to enter the expert interviews with as little prior theoretical knowledge as possible. We therefore limit our focus on the two concepts’ practical purpose, working definitions, and sub-concepts in order to structure the interviews. In the third section, the research methodology is presented, followed by the findings in the fourth section derived from the data analysis. Subsequently, these results are critically discussed. Finally, the managerial implications, limitations, and suggestions for future research are pointed out.

2. Theoretical Background

The characteristic of qualitative research is to not have a high level of prior knowledge, which is why only a brief literature review was carried out before conducting the interviews in order to gain a general understanding of the concepts and to structure the interview questions based on this basic knowledge. The academic research databases Web of Science as well as EBSCOhost were selected to execute a structured keyword search. The search aimed at the identification of state-of-the-art review articles and highly cited seminal papers, preferably published in the year 2000 or later. For CF, the keywords “foresight”, “strategic foresight”, and “corporate foresight” were searched for in the title. The use of truncations helped to include all possible forms of spellings as well as singular and plural forms of the keyword. Other synonyms, for instance “futures studies” or “futures research”, were not included in the search string, as they are associated with another research tradition which is not only focused on business and management. Subsequently, the abstracts and articles were manually screened for their relevance to our study. The literature search on DC was conducted similarly, only using the keyword “dynamic capability” or “dynamic capabilities”. Overall, more high-quality research exists on DC.

2.1. Corporate Foresight

Rather than a mere process, CF, sometimes also ‘strategic foresight’ [] or just ‘foresight’, is considered as a firm capability [,] that comprises a set of future-oriented activities like scenario planning, road mapping or Delphi studies, only to mention some key activities, with the aim of handling environmental uncertainty []. For this purpose, the market environment is scanned and monitored to detect and analyze relevant drivers of change in order to identify discontinuous change, as well as possible technological changes and trends which shape the firm’s evolving future context. The challenge is not only to recognize what is changing but also to evaluate the impact of this change for one’s own firm [,]. The implications for the business and corporate strategy on how to respond to future events are evaluated resulting in knowledge which helps top managers to lead the company into the future []. This knowledge is integrated into strategic decisionmaking processes to be able to anticipate these emerging threats and opportunities at an early stage by altering the organization’s strategy [,,].

CF exceeds forecasting []. While natural processes often can be forecasted because they are based on causal links, social changes are based on human intentions, social interactions, and coincidence [,]. In contrast to forecasts with the goal of a clear future prediction, the term CF stands for the consideration of multiple possible futures. Hence, CF is conceptualized as a firm’s capability to use a set of practices which is concerned with what possible future scenarios might look like. They enable firms to sense trends faster than competitors and to gain a deeper understanding about the effects of these trends []. From these probable scenarios, the most effective options for action and design are derived. In this way, the risk of short-sightedness is to be reduced. In addition, it is intended to foster the ability of companies to anticipate events before they actually occur and, at best, to actively shape their development, thus strengthening the firm’s ability to learn and innovate ahead of its competitors.

In brief, firms should learn from the multiple futures, make strategic decisions and, with the help of these decisions, secure their long-term competitiveness and survival. Firms must exploit the environmental changes in the long run, which is why CF has a strategic character [,,,,].

2.2. Dynamic Capabilities

Teece et al. are regarded as the founders of the DC approach, having extended the resource-based view (RBV) through a dynamic perspective []. The RBV states that companies can create and maintain a sustainable competitive advantage in stable environments from resources that are valuable, rare, inimitable, and organized []. In contrast, the DC approach describes the adaptation of the resource portfolio in turbulent environmental conditions. It thus describes the potential of companies to adapt to changing environmentals by tailoring and further enhancing internal resources as well as integrating external resources to seize opportunities [,,]. Due to the characteristics of the VUCA world, a firm’s resource base has to adapt to changed conditions to create value and generate a competitive advantage [].

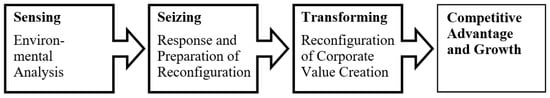

In his later work, Teece extended this view by refining the DC conceptualization through a three-step approach []. First, opportunities and threats are sensed by scanning the external environment to obtain market, technological, and competitive information from outside and inside the company (sensing). Second, a strategic response to the detected opportunities has to be formulated (seizing). Third, the firm carries out the implications for action, which involves enhancing, combining, reallocating, and reconfiguring the tangible and intangible assets (transforming) in order to sustain profitable growth and maintain competitiveness (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Dynamic Capabilities [].

However, the creation of a strategic competitive advantage is not based on having DCs alone but in using the capabilities earlier than competitors to create resource configurations that provide superiority over the competition [,,].

In summary, DC include the functions of identifying market and technological change, anticipatipating these developments, and implementing means of action at an early stage with the aim of altering the resource base [,]. DCs enable organizations to “continuously create, extend, upgrade, protect, and keep relevant the enterprise’s unique asset base” ([] p. 1319), constituting “the firm’s ability to integrate, build, and reconfigure internal and external competences to address rapidly changing environments” ([] p. 516). Hence, DCs are decisive for the survival of a firm [].

3. Research Methodology

The objective of our research is to obtain an ‘understanding’ [] about the links between CF and DCs as organizational phenomena in the real world []. Since this constitutes an unexplored topic, qualitative expert interviews were conducted. This explorative approach can inductively gain additional primary material, discover new facts, and generate propositions which can be examined for their validity in subsequent studies [,]. Therefore, this open-ended approach can extend the existing theory [,,], especially by filling theoretical gaps and connecting previously unconnected theories []. The present study does not formulates propositions. The individual insights from the interviews are not of interest for the research but the conclusions that can be drawn from the data are. Therefore, our methodology—building on rudimentary prior theoretical knowledge and searching fo rnew analytical insights []—is in the tradition of ‘theory elaboration’, as coined by Lee et al. and Maitlis [,], meaning a partly deductive and partly inductive approach [,,].

Qualitative studies are particularly suitable for in-depth analyses of organizational processes [,,,] and thus capabilities associated with these processes. In particular, we were able to closely capture foresight experts’ subjective experiences and interpretations of CF, DCs, and their links. Since these concepts are rather abstract categories, the interviews could also add vividness, concreteness, and richness to the phenomena and their relations [,,].

3.1. Sample and Data Collection

We employed a purposive sampling technique for in-depth analyses [,,]. We selected seven foresight experts from Germany (Table 1). We collected and analyzed the data right after collection and continued until reaching a saturation point, i.e., no substantial additional insights could be gained [,]. A similar, recent investigation—exploring the links between CF and effectuation—was based on interviews with seven futurists and four entrepreneurs []. We aimed for maximum variation while following the principles of appropriateness and adequacy [,]. This sampling approach allows us to find information not only about general trends among the respondents but possibly also about contrasting data [].

Table 1.

Sample Overview.

Two interviews were carried out by telephone and five face-to-face, all in German. They lasted between 25 and 60 min.

A semi-structured interview form was chosen which covered a framework of themes along an interview guideline with predetermined open questions [,]. This interviewing technique is favored to gain insights from individuals who are affected by the research phenomenon []. It constitutes the most frequently used qualitative research method []. The interview guideline standardizes the interviewer’s actions, since the questions are basically the same for each interview. The involvement of the interviewer therefore is rather minimal. The respondents’ statements potentially enable the researcher to find new concepts instead of affirming existing ones [].

The open-ended questions allowed the interviewees to answer with their own words and did not provide them with predefined answers. The questions had to be answered in each interview but both the order and the wording of the questions depended on the course of the conversation in order to create a natural conversation situation [,,]. By using an interview guideline, it is ensured that all relevant information is collected in a similar way to enable a better data analysis thereafter. Moreover, the guideline helped to focus on the answering of the research questions as time was limited. All questions were re-examined in terms of their relevance and focus on the research question and tested in an initial interview. The pre-test confirmed that the questions were comprehensible, in a useful order, and answerable.

As an opening to the interview, the objective of the study was presented, explaining that the aim was to examine the relationships between DCs and CF. The interviewees were guaranteed anonymity of the given responses to ensure that no conclusions on individual respondents or companies can be drawn and that personal data are protected. The initial questions on the background of the participants and their typical activities in foresight served as a start to the conversation because they could easily be answered and ideally made each respondent comfortable about the interview situation. Using a question about typical activities of foresight experts, the respondents were asked what precisely they understand the term CF to mean. The second question addressed the respondents’ understanding of the concept of DCs. In several cases, the interviewees had their own interpretation of the term but were not familiar with the scholarly understanding of it. In these cases, the interviewer gave a short explanation about the concept. The two subsequent questions focused on the impact of CF on the renewal of competitiveness and the renewal of the firm’s resource. Successively, the interview participants were open-endedly asked about their views on the relationships between the three DC sub-processes (sensing, seizing, and transforming) and CF. The final question addressed the abstract relationship between the two concepts.

3.2. Data Analysis

Data analysis was employed by a constant, comparative method [,] which consisted of data comparison, deduction, conclusions, and verification [].

In the first step, the interviews were transcribed with the software f5transkript. Colloquial langue was adjusted to standard spelling whilst retaining the sentence form. In addition, word and sentence breaks (“/”) as well as pauses (“…”) were marked. Comprehension signals of the currently non-speaking person are not captured unless the answer consists only of an affirmative or negative “mhm” without further expression. Non-verbal expressions were only transcribed if they account for a change in the meaning of a statement. Illustrative quotes in the following sections were translated to English staying as close to the literal meaning as possible. The texts were anonymized.

In the next step, the texts were coded by the interviewer using the same software and following the Gioia approach []. The 2nd order themes were already given as they corresponded to the interview questions. Relevant text passages which can be assigned to the corresponding 2nd order themes were marked in order to get a broad overview and to highlight the structure of the text without adhering to any existing theory or a priori hypotheses []. The marked text passages were then condensed into keywords, which represent the more precise 1st order themes []. As a result, a list of 1st order concepts that closely correspond to the terms the interviewees used was extracted. We then analyzed whether the respective keywords were mentioned by multiple respondents. Subsequently, all text passages with the same codes were compared and evaluated in the sense of inductive theory formation. The final interview question about the understanding of the abstract relationships between DCs and CF is not listed as a separate 2nd order theme but is intended to illustrate the interviewees’ summarizing view of the links.

4. Findings and Proposition Generation

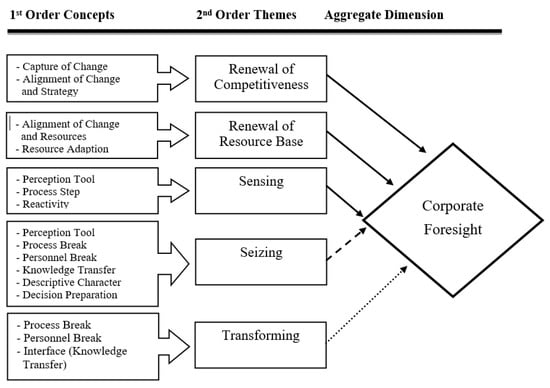

The main finding of the study is that the concept of dynamic capabilities partly corresponds with foresight and partly has only lose relationships. Figure 2 provides a comprehensive overview of the findings.

Figure 2.

Coding.

4.1. Renewal of Competitiveness

The first interview question aimed to find out what contribution CF makes to renew competitiveness. The background to this question is that firms with DCs can adapt to changing environmental conditions ahead of their competitors and thus gain competitive advantages. As a result, competitiveness is renewed in two ways: on the one hand through a temporal advantage over the competition in which the organization has “to try to understand in every area what the relevant change trends are and at an early stage not only has to react but has to align [the] portfolio, [the] organization” (I7, 2019, 04:29, para. 8). On the other hand, a competitive advantage can be achieved when the firm not only reacts faster to the changes but, if possible, actively shapes these changes with the competitors being forced to adapt to the proactively operating company (I1, 2019, 35:09, para. 55). Consequently, a positive contribution of DCs to the renewal of competitiveness can be concluded.

However, the objective of this question was to find out whether also CF contributes to renewing competitiveness. Four out of seven interviewees reported that CF contributes to the renewal of competitiveness. One respondent explained that this is possible through “a deep and systematic understanding [...] of the market environment” (I7, 2019, 03:29, para. 8) by capturing and interpreting the changes and the emergence of new challenges in the markets, consumer wishes and technologies (I2, 2019, 06:25, para. 12; I4, 2019, 21:14, para. 24; I7, 2019, 04:29, para. 8). Therefore, CF can be seen as an antecedent of competitive advantages:

P1: CF fosters a firm’s better understanding of change in the business environment in such a way that strategic competitive advantages can be generated.

Additionally, firms can recognize and sense rather uncertain opportunities that derivate from the previous path. One respondent interpreted CF as the firm’s “playing leg” (I5, 2019, 13:23, para. 9–14.16; para. 21):

P2: CF empowers companies to identify opportunities beyond their previous horizons, which can increase their competitiveness.

On the basis of this capture of change, an alignment of change and strategy can be initiated to define the corporate strategy and positioning (I2, 2019, 06:45, para. 12). The firm continuously evaluates whether the chosen strategy is still the right one or a strategic adjustment is needed (I1, 2019, 17:55, para. 31). If the firm succeeds in addressing the opportunities and challenges earlier than the competition, then it can renew its competitiveness (I4, 2019, 21:21, para. 24). A respondent mentioned that “the most important contribution to maintaining the competitiveness of CF [...] is not to be too strongly or exclusively involved in one driver or a few trends from only one sub-sector but to always try to look at all social sub-systems” (I7, 2019, 04:00, para. 8). Firms must perceive the major change trends in each relevant area and must align the organization accordingly in “good times” (I7, 2019, 04:29, para. 8). As one expert reflected, CF represents “the spearhead of competitiveness” (I4, 2019, 23:16, para. 24). Hence, a clear link between CF and the renewal of competitiveness can be derived:

P3: Firms conducting CF activities show better-informed strategic decisions, which can result in higher competitiveness.

4.2. Renewal of Resource Base

With the increasing complexity and turbulence of the environment, the need for companies to quickly anticipate changing environmental conditions by adapting their resources increases. The answers to the second interview question revealed that five out of seven interviewees observe a positive contribution of CF to firms’ capability to permanently change their resource base so that it does not become obsolete. Firms identify the need for a resource base adjustment in “good times” and subsequently identify which resources are required to meet these changes (I1, 2019, 22:00, para. 37; I3, 2019, 11:33, para. 24; I6, 2019, 07:25, para. 12; I7, 2019, 06:34, para. 12). Hence, companies adopt an outside-in perspective (I2, 2019, 11:26, para. 24):

P4: Companies conducting CF activities adopt an outside-in perspective that fosters a renewal of the resource base.

One foresight expert usually conducts a SWOT analysis after the scenario analysis, which addresses the external opportunities and threats identified in the scenarios, the strengths, in which “the resources are essentially present” (I1, 2019, 21:04, para. 37), and the weaknesses of the firm. The analysis can contribute to the resource adaptation, the second identified concept. Firms must clarify whether the opportunities can be addressed and the threats can be avoided with the available resource base. If this is not the case, an enhancement of strengths and a reduction and compensation of weaknesses in core areas that prevent the company from seizing opportunities and avoiding risks are required (I1, 2019, 22:00, para. 37):

P5: The renewal of the resource base is determined by the future positioning identified through CF.

4.3. CF and Sensing

In the main part of the interview, the interviewees were asked about the relationships of DCs on CF. Sensing revealed three concepts regarding CF. In particular, all interview participants believed that there exists a clear connection between sensing and CF (I1, 2019, 25:06, para. 45; I2, 2019, 17:53, para. 24; I3, 2019, 20:41, para. 40; I4, 2019, 37:43, para. 40; I5, 2019, 23:31, para. 31; I6, 2019, 10:23, para. 22; I7, 2019, 12:25, para. 20). CF is considered a “perception tool” that detects changes in the corporate environment (I3, 2019, 36:52, para. 38; I5, 2019, 22:19, para. 29; I7, 2019, 12:38, para. 20). An environmental analysis is carried out in the sensing process. “Foresight is [therefore] a tool for sensing” (I3, 2019, 20:37, para. 38). For this reason, sensing constitutes a process step of CF (I1, 2019, 25:34, para. 45), as one expert described: “CF is the only instrument used to sense environmental changes” (I5, 2019, 21:43, para. 29). In the perception part, CF should therefore play the decisive role (I7, 2019, 12:38, para. 20) since “it is the only instrument [...] that [...] can increase the perceptiveness of the firm” (I5, 2019, 22:19, para. 29):

P6: The purpose of CF is to sense environmental changes.

Sensing constitutes a reactive action of the firm, as it perceives changes after they have already occurred (I2, 2019, 19:45, para. 26). Thus, the reactivity represents the third identified concept, meaning that many firms do not operate proactively.

4.4. CF and Seizing

As much as the interviewees agreed on the relationship between sensing and CF, their opinions on seizing differed to some extent. While four participants said that they do not see a relationship between CF and seizing and that the “process break” for them occurs after the sensing phase, two other experts stated they see a rather partial relationship, and one mentioned a clear relationship. A total of six concepts were identified, the first being a perception tool. This further illustrates that the majority of the participants considered CF primarily as a perception and observation tool and less as an implementation tool (I3, 2019, 21:21, para. 44; I7, 2019, 14:58, para. 24). For this reason, a “process break” emerges, since seizing is not integrated in the CF process (I1, 2019, 27:50, para. 47; I3, 2019, 21:09, para. 44; I5, 2019, 25:38, para. 35, 26:07, para. 35). The lack of integration is often related to a “personnel break” in firms (I1, 2019, 28:52, para. 47). External foresight consultants often are engaged to conduct future-oriented environmental analyses but are not involved in the further decisionmaking process (I7, 2019, 13:34, para. 22). Rather, the firm’s executives decide on the strategic direction (I1, 2019, 29:21, para. 47). For this reason, an “interface”, which may lead to a lack of common future understanding, is required to transfer the gained knowledge from the sensing process (I1, 2019, 30:12, para. 47; I7, 2019, 13:30, para. 22). CF ultimately has the task of collecting the relevant knowledge during the sensing process and then operationalizing it in a way so it can be transferred to decisionmaking (I7, 2019, 13:30, para. 22). The prepared knowledge is passed on to the management via a functioning interface. Consequently, a key finding is that CF has a descriptive character (I3, 2019, 23:51, para. 46) and is regarded as a decision preparation, but not as decision making (I7, 2019, 13:30, para. 22). Most of the participants shared this view:

P7: Knowledge generated in the CF process can inform and therefore improve the seizing process.

4.5. CF and Transforming

Six out of seven foresight experts did not see a clear relationship between CF and transforming. Due to the fact that foresight experts often are external consultants, they do not participate in the reconfiguration and transformation of the business (I3, 2019, 24:17, para. 48; I3, 2019, 24:36, para. 50). Although CF is not integrated in the transformation process, it can give the impetus for a change process (I5, 2019, 28:53, para. 37). However, it is necessary that transforming was induced by insights from CF in order to be competitive in the long-run:

P8: Knowledge generated in the CF process can generate an impetus and improve the transforming process

In summary, it can be concluded that four out of seven interviewees saw a clear process break after the sensing phase, while two others saw only a partial relationship between CF and seizing. Interestingly, these participants work as external foresight consultants. Only one of the experts is an internally employed foresight manager. He had an entirely different view to the consultants. For him, all dynamic capability activities are part of the CF process. In his company, all three sub-activities are handled and implemented in the same way as they are described in the working definition for this research project (I4, 2019, 41:20, para. 48). These divergent views between consultants and internal employees represent an important and interesting insight, which will be discussed in greater detail in the following chapter.

In the last interview question, the participants were asked about their view on the abstract relationship between DCs and CF. The majority of respondents considered the two concepts to be related and coexistent (I2, 2019, 51:46, para. 50; I6, 2019, 19:41, para. 40). They are part of each other (I1, 2019, 42:31, para. 63) and mutually strengthen each other (I1, 2019, 42:59, para. 63). Two other interviewees argued that CF can be described as a special type of DC (I2, 2019, 50:59, para. 48; I6, 2019, 17:18, para. 36). One of the observations made is “that it must actually be an equilibrium” (I5, 2019, 29:19, para. 39). This means that CF triggers the observation of a need for change but DC processes put the change process into action. Therefore, DCs must already be present in the company to a certain extent since they cannot be triggered by CF alone (I5, 2019, 30:19, para. 39) as one expert described it: “Both must exist in the company and they must always somehow be managed together” (I3, 2019, 32:15, para. 60). In addition, it needs the openness of the company for both, DCs and CF (I1, 2019, 12:37, para. 21; I3, 2019, 32:55, para. 62):

P9: The more balanced the joint integration of CF and DCs is, the higher the future orientation will be.

This proposition leads to the assumption that companies with a higher future orientation can perform better. Both concepts are interdependent and support each other.

The time perspective of both concepts also related both concepts to each other. While CF takes a mere future perspective as perception tool, DCs as the adaptability require each company to remain in the market and take on a present perspective (I3, 2019, 33:26, para. 62–34:53, para. 66). CF supports DCs to the extent that DC processes can use methods from CF, and probably also the other way around (I6, 2019, 18:36, para. 38–19:56, para. 42).

The three-part approach of perceiving, prospecting, and probing represents the superordinate process steps of CF, as it is designed in the company of one interviewee (I6, 2019, 04:22, para. 6). Perceiving is the process by which companies become aware of external change. Prospecting enables firms to understand the drivers and direction of change and to bring it into the context of their own organization. Probing refers to actions which are derived for implementation (I6, 2019, 04:22, para. 6). This approach helps to understand how a firm’s capabilities and resources need to be changed in order to remain competitive (I6, 2019, 06:25, para. 10–07:25, para. 12). These future preparation activities show parallels to the three-part approach of DCs.

5. Discussion

The results revealed that CF primarily corresponds to sensing activities, while transforming is not integrated in the CF process. This is in congruence with the findings by Heger and Boman, who investigated the use of foresight knowledge in firm networks and found that mainly sensing rather than initiating activities are subject of foresight knowledge []. Similarly, Rhisiart et al. argue that firms engaging in scenario planning can strengthen their sensing capabilities but no other DC subtypes [].

The experts in our study disagreed on seizing. With regard to the first two interview questions, there is also a positive connection with CF. Firms must continuously renew their resource base if they are to survive with DCs being employed because they aim at removing resources that prevent the company from seizing opportunities as well as recombining old resources in new ways []. When using DCs earlier and more efficiently than competing firms, it has an impact on competitiveness.

Our study showed that all experts saw a positive significant relationship between CF and the renewal of the resource base on the one hand and the renewal of competitiveness on the other. Hence, not only DCs can be used to explain how companies leverage their resource base, but also CF enables a firm to detect a need to renew its resource portfolio with the long-term goal of sustaining firm performance and competitiveness. One can argue that, in the VUCA world, knowledge as a resource is considered one of the most important sources of competitive advantage [,]. This future-oriented knowledge is crucial for renewal processes and gained through CF activities.

CF can be regarded as a DC as mentioned by one interviewee (I6, 2019, 17:18, para. 36), since it represents the specific capability to gain knowledge about the environment and how it is changing in the future (sensing). The expert answers to the first two interview questions crystallized a link between the two concepts. Collectively, the renewal of the resource base and therefore competitiveness lead to the renewal of the strategy, which is the main goal of DCs and can therefore can be considered a goal of CF. The objective of strategic renewal is the long-term competitiveness of a firm through aligning internal capabilities and resources as well as the change in the external environment []. For a renewal approach to strategy, the resource base has to be updated in order to secure the long-term competitiveness. This has to happen as early as possible, bringing DCs and CF into the game as powerful lenses to examine technological and market change. In short, CF activities stimulate processes that lead to resource adjustment. Adapting the resource base to changes in the business environment generates competitive advantages and thus ideally leads to an edge over competitors and increased business performance.

In close connection with the partly inconsistent opinions among the experts is the issue of difference between external foresight consultants and internal foresight managers. During the interviews, it became obvious that the only interviewee who pursues CF activities for internal purposes and not for external clients takes a strinkingly different view of the integration of CF in the three DC sub-processes. One possible explanation for this result could be the mentioned lack of uniform definitions. Thus, the range of CF is perceived differently between consultants and activities are thus embedded and integrated in different ways. This may also be the case depending on the individual firm. In this context, the firm size can also have a considerable influence on the integration of CF. On the one hand, a positive relationship between the firm size and the execution of environmental analyses can be derived. Consequently, CF is used more frequently in large companies than in smaller ones, since the latter are more dynamic (I4, 2019, 43:05, para. 50). Additionally, larger companies are more likely to engage in CF since they have more financial resources than smaller companies (I4, 2019, 31:22, para. 34). On the other hand, in large companies a personnel break can often be observed, which prevents a deep integration of CF. However, the difference between external and internal consultants is not only a matter of job title but also depends on the respective firm. Thus, an internal foresight manager from another firm may assess the situation differently than the interviewed foresight manager.

A central element of qualitative research is openness. Accordingly, the interviewer approached the investigation without a predefined theoretical lens but rather a high level of openness towards the research objective. Nevertheless, it was formerly expected that all DC sub-processes would be somewhat related to CF. However, this expectation was refuted during the evaluation of the interviews.

The authors’ expectation is in line with the respondents’ view: CF and DC should be further integrated in order to ensure a solid foundation for strategic decisionmaking. The division of work, i.e., the separation of information gathering by CF and decisionmaking based on this information might have adverse effects. It can lead to misunderstandings and misinterpretations. Therefore, CF should be further integrated into all DC sub-processes. CF creates orientation knowledge by an intense engagement with (possible) changes in the environment (I7, 2019, 14:18, para. 22). This knowledge triggers processes of resource adaptation. Accordingly, CF can be considered as a perception and observation tool, but not as an implementation tool. This result does not correspond to the authors’ expectation either.

Openness is not only a central aspect of qualitative research but is also important for the development of a firm. Firms must possess this attribute in order to gain experience. The data indeed points toward this fact. Several interview participants stated that companies should not hesitate if a scenario does not develop as expected. A key part of this is to be open in dealing with mistakes and to learn from them. In line with this is a statement from the interviews: “this openness in dealing with future options is, in my view, the crux” (I1, 2019, 12:37, para. 21). In this context, managers have a distinctive role in the DC process. Capturing new strategic opportunities is a managerial function. However, it is not possible for a manager to have a concrete idea of DCs, since a uniform, generally accepted definition of the complex construct of dynamic capabilities does not exist yet.

6. Conclusions

The aim of this paper was to explore the links between CF and DCs, two concepts considered to be important for companies to generate competitive advantages by dealing with future opportunities. For this reason, seven foresight experts with different functions and backgrounds were interviewed. The main finding of the study is that CF is not clearly integrated in all subcategories of DCs. However, they cannot be managed independently if a firm wants to build a superior position in future markets. At present, it can be concluded that there exists a relationship between CF and DCs regarding the sensing process but CF is hardly involved in the subsequent steps.

A first important step for a deeper integration of seizing and transforming is a firm’s reformulated understanding of both concepts which broadens them in order to create a common conceptual understanding. In this way, different conceptual perceptions between internal and external foresight experts as well as between companies can be reduced.

The findings have several managerial implications. When major environmental changes are underestimated or not recognized, firms may risk a strategic drift and lose their competitive position. In the VUCA world, firms cannot rely on static processes and rigid resources bases as the environment is ever-evolving dynamically. The resource base has to be renewed appropriately to renew competitive advantages. To handle environmental uncertainty, it is important for companies to possess DCs. CF itself can be regarded as a specific DC that enables a firm to detect the need to renew its portfolio of resources. Hence, management needs to understand the relevance and meaning of both concepts. In the propositions, a positive relationship between the two concepts was deduced. A joint consideration can therefore lead to a superior firm performance. Therefore, management should consider CF and DCs collectively.

It is obvious that it is better for firms to be proactive in order to gain advantages over competitors. If this is not possible, they have to be reactive at least and do not ignore occurring changes. Otherwise, the firm may not stay in the market. For this reason, there must be an awareness for the changing conditions, as well as the necessity for CF.

Finally, the results should sensitize companies to be aware of the relevance of the personnel break in the DC approach. A strong focus on the involvement during environmental scanning is recommended for management. If this is not possible, then the consultants conducting the environmental analysis should be integrated in the decisionmaking process. Management should not underestimate the loss of information when different individuals are involved in the information gathering and decisionmaking process, as strategically unfavorable decisions may be made because the accuracy of the information decreases during the knowledge transfer.

There are several limitations associated with this research that have to be acknowledged. It is intended to give a first indication about the relationships between CF and DCs. Nevertheless, more research should be conducted to gain specific insights.

Due to the limited number of interviews, the study lacks the means to analyze the results quantitatively and make statistical generalizations. Due to the small sample, representativeness and a high level of generalizability could not be achieved. Future research should test our qualitatively generated propositions and consider moderators and mediators.

Similarly, mainly external consultants were interviewed, which may exclude deeper insights from internal foresight experts. As pointed out before, the conceptual perception differed between the respondents. A recommendation for further research is therefore to interview a larger sample. Interesting insights could be provided by variations across industries and professions of the respondents. Future studies could also address the differences between internal foresight managers and external foresight consultants that were observed. It may be important to achieve a balance between both among the sample. Another possibility would be to consider small and large enterprises separately in order to achieve specific results for different company sizes. At this point, it would be interesting to examine whether the respondents’ assumption that the integration of CF depends on the size of the company is correct or can be refuted. In need for further investigation is the statement of one interviewee saying that it is important to not only look at the company and its resources singularly, but rather in relation to other companies and stakeholders (I6, 2019, 07:45, para. 12). Often companies alone do not dispose of sufficient resources to execute CF effectively, which is why they have to be considered in relation to other companies in order to dispose of sufficient resources (I6, 2019, 08:23, para. 14). In addition, this may point future research towards the relevance of jointly considering both topics.

Additionally, we adopted a rather narrow DC lens focusing on the purpose and sub-processes of DCs. For an exploratory study, this procedure is adequate. However, DC research reveals a complex field with many more conceptualizations. An example of this is learning as the basis for DCs, or path-dependencies indicating that DCs depend on a firm’s previous decisions and routines, which have not been included in the study. Future research should expand on the DC conceptualization.

Despite these limitations, this explorative study offers a first analysis and encourages future research towards a joint consideration.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.-M.S. and V.T.; methodology, L.-M.S. and V.T.; software, L.-M.S.; formal analysis, L.-M.S.; investigation, L.-M.S. and V.T.; writing—original draft, L.-M.S. and V.T.; writing—review and editing, V.T.; funding acquisition, V.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The research project received no funding.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the respondents’ engagement in the study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare there is no conflict of interest with regard to this manuscript.

References

- Bennett, N.; Lemoine, G.J. What a difference a word makes: Understanding threats to performance in a VUCA world. Bus. Horiz. 2014, 57, 311–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaivo-oja, J.R.L.; Lauraeus, I.T. The VUCA approach as a solution concept to corporate foresight challenges and global technological disruption. Foresight 2018, 20, 27–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Aveni, R.A.; Dagnino, G.B.; Smith, K.G. The age of temporary advantage. Strateg. Manag. J. 2010, 31, 1371–1385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volberda, H.W. Toward the flexible form: How to remain vital in hypercompetitive environments. Organ. Sci. 1996, 7, 359–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, C.; Agarwal, R. The Digitization of Healthcare: Boundary Risks, Emotion, and Consumer Willingness to Disclose Personal Health Information. Inf. Syst. Res. 2011, 22, 469–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouncken, R.B.; Kraus, S.; Roig-Tierno, N. Knowledge- and innovation-based business models for future growth: Digitalized business models and portfolio considerations. Rev. Manag. Sci. 2019. In Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Höhne, S.; Tiberius, V. Powered by blockchain: Forecasting blockchain use in the electricity market. Int. J. Energy Sect. Manag. 2020. In Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loebbecke, C.; Picot, A. Reflections on societal and business model transformation arising from digitization and big data analytics: A research agenda. J. Strateg. Inf. Syst. 2015, 24, 149–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreau, F. The Disruptive Nature of Digitization: The Case of the Recorded Music Industry. Int. J. Arts Manag. 2013, 5, 18–31. [Google Scholar]

- Niemand, T.; Coen Rigtering, J.P.; Kallmünzer, A.; Kraus, S.; Maalaoui, A. Digitalization in the financial industry: A contingency approach of entrepreneurial orientation and strategic vision on digitalization. Eur. Manag. J. 2020. In Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiberius, V.; Hirth, S. Impacts of digitization on auditing: A Delphi study for Germany. J. Int. Account. Audit. Tax. 2019, 37, 100288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiberius, V.; Rasche, C. FinTechs: Disruptive Geschäftsmodelle im Finanzsektor; SpringerGabler: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Kraus, S.; Clauß, T.; Breier, M.; Gast, J.; Zardini, A.; Tiberius, V. The economics of COVID-19: Initial empirical evidence on how family firms in five European countries cope with the corona crisis. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2020. In Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuckertz, A.; Brändle, L.; Gaudig, A.; Hinderer, S.; Morales Reyes, C.A.; Prochotta, A.; Steinbrink, K.M.; Berger, E.S.C. Startups in times of crisis—A rapid response to the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Bus. Ventur. Insights 2020, 13, e00169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brand, M.; Tiberius, V.; Bican, P.M.; Brem, A. Agility as an innovation driver: Towards an agile front-end of innovation framework. Rev. Manag. Sci. 2019. In Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charinsarn, T. Capabilities in the VUCA Market. 2017. Available online: https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/capabilities-vuca-market-tanai-charinsarn (accessed on 20 April 2020).

- Ayres, R.U.; Axtell, R. Foresight as a survival characteristic: When (if ever) does the long view pay? Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 1996, 51, 209–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuhls, K. From forecasting to foresight processes—new participative foresight activities in Germany. J. Forecast. 2003, 22, 93–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iden, J.; Methlie, L.B.; Christensen, G.E. The nature of strategic foresight research – a systematic literature review. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2017, 116, 87–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohrbeck, R.; Schwarz, J.O. The value contribution of strategic foresight: Insights from an empirical study of large european companies. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2013, 80, 1593–1606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiberius, V. Scenarios in the strategy process: A framework of affordances and constraints. Eur. J. Futures Res. 2019, 7, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohrbeck, R.; Gemünden, H.G. Corporate foresight: Its three roles in enhancing the innovation capacity of a firm. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2011, 78, 231–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von der Gracht, H.A.; Stillings, C. An innovation-focused scenario process—A case from the materials producing industry. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2013, 80, 599–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J. Technology foresight for competitive advantage. Long Range Plan. 1997, 30, 665–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohrbeck, R.; Kum, M.E. Corporate foresight and its impact on firm performance: A longitudinal analysis. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2018, 129, 105–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenhardt, K.M.; Martin, J.A. Dynamic capabilities: What are they? Strateg. Manag. J. 2000, 21, 1105–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barreto, I. Dynamic Capabilities: A review of past research and an agenda for the future. J. Manag. 2010, 36, 256–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teece, D.J. Explicating dynamic capabilities: The nature and microfoundations of (sustainable) enterprise performance. Strateg. Manag. J. 2007, 28, 1319–1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teece, D.J.; Pisano, G.; Shuen, A. Dynamic capabilities and strategic management. Strateg. Manag. J. 1997, 18, 509–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heger, T.; Boman, M. Networked foresight - The case of EIT ICT Labs. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2015, 101, 147–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhisiart, M.; Miller, R.; Brooks, S. Learning to use the future: Developing foresight capabilities through scenario processes. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2015, 101, 124–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fergnani, A. Corporate foresight: A new frontier for strategy and management. Acad. Manag. Perspect. 2020. In Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarz, J.O.; Rohrbeck, R.; Wach, B. Corporate foresight as a microfoundation of dynamic capabilities. Futures Foresight Sci. 2019. In Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haarhaus, T.; Liening, A. Building dynamic capabilities to cope with environmental uncertainty: The role of strategic foresight. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2020, 155, 120033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gioia, D.A.; Corley, K.G.; Hamilton, A.L. Seeking qualitative rigor in inductive research: Notes on the Gioia methodology. Organ. Res. Methods 2013, 16, 15–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, A.; Sainsbury, P.; Craig, J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 2007, 19, 349–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vecchiato, R.; Roveda, C. Strategic foresight in corporate organizations: Handling the effect and response uncertainty of technology and social drivers of change. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2010, 77, 1527–1539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilar, F.J. Scanning the Business Environment; MacMillan: New York, NY, USA, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Tiberius, V. Towards a ‘Planned Path Emergence’ View on Future Genesis. J. Futures Stud. 2011, 15, 9–24. [Google Scholar]

- Tiberius, V. Zukunftsgenese—Theorien des Zukünftigen Wandels; SpringerVS: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Rohrbeck, R. Corporate Foresight. Towards a Maturity Model for the Future Orientation of a Firm; Physica: Heidelberg, Germany, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Barney, J.B. Looking inside for competitive advantage. Acad. Manag. Executive 1995, 9, 49–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambrosini, V.; Bowman, C. What are dynamic capabilities and are they a useful construct in strategic management? Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2009, 11, 29–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Outwaite, W. Understanding Social Life: The Method Called Verstehen; George Allen and Unwin: London, UK, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Cassell, C.; Symon, G. Essential Guide to Qualitative Methods in Organizational Research; Sage: London, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Bansal, P.; Corley, K. Publishing in AMJ—Part 7: What’s different about qualitative research? Acad. Manag. J. 2012, 55, 509–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bluhm, D.J.; Harman, W.; Lee, T.W.; Mitchell, T.R. Qualitative research in management: A decade of progress. J. Manag. Stud. 2011, 48, 1866–1891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graebner, M.E.; Martin, J.A.; Roundy, P.T. Qualitative data: Cooking without a recipe. Strateg. Organ. 2012, 10, 276–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, T.W.; Mitchell, T.R.; Sablynski, C.J. Qualitative research in organizational and vocational psychology, 1979-1999. J. Vocat. Behav. 1999, 55, 161–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobides, M.G. Industry change through vertical disintegration: How and why markets emerged in mortgage banking. Acad. Manag. J. 2005, 48, 465–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maitlis, S. The social processes of organizational sensemaking. Acad. Manag. J. 2005, 48, 21–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denis, J.L.; Lamothe, L.; Langley, A. The dynamics of collective leadership and strategic change in pluralistic organizations. Acad. Manag. J. 2001, 44, 809–837. [Google Scholar]

- Ferlie, E.; Fitzgerald, L.; Wood, M.; Hawkins, C. The nonspread of innovations: The mediating role of professionals. Acad. Manag. J. 2005, 48, 117–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pajunen, K. Stakeholder influences in organizational survival. J. Manag. Stud. 2006, 43, 1261–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doz, Y. Qualitative research for international business. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2011, 42, 582–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denzin, N.K.; Lincoln, Y.S. Introduction: The discipline and practice of qualitative research. In Handbook of Qualitative Research, 2nd ed.; Denzin, N.K., Lincoln, Y.S., Eds.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2000; pp. 1–28. [Google Scholar]

- Guest, G.; Bunce, A.; Johnson, L. How many interviews are enough? An experiment with data saturation and variability. Field Methods 2006, 18, 59–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morse, J.M.; Barrett, M.; Mayan, M.; Olson, K.; Spiers, J. Verification strategies for establishing reliability and validity in qualitative research. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2002, 1, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, R.S. Purposive sampling. In Encyclopedia of Quality of Life and Well-Being Research; Michalos, A.C., Ed.; Springer: Dordrecht, Holland, 2014; pp. 5243–5245. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenhardt, K.M. Building theories from case study research. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1989, 14, 532–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djuricic, K.; Bootz, J.P. Effectuation and foresight—An exploratory study of the implicit links between the two concepts. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2019, 140, 115–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaskell, G. Individual and group interviewing. In Qualitative Research with Text, Image and Sound; Bauer, M.W., Gaskell, G., Eds.; A practical handbook for social research; Sage: London, UK, 2000; pp. 38–56. [Google Scholar]

- Seawright, J.; Gerring, J. Case selection techniques in a menu of qualitative and quantitative options. Political Res. Q. 2008, 61, 294–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, S.Q.; Dumay, J. The qualitative research interview. Qual. Res. Account. Manag. 2011, 8, 238–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dicicco-Bloom, B.; Crabtree, B.F. The qualitative research interview. Med. Educ. 2006, 40, 314–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corbin, J.; Strauss, A. Grounded theory research: Procedures, canons, and evaluative criteria. Qual. Socioliol. 1990, 13, 3–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glaser, B. The constant comparative method of qualitative analysis. Soc. Probl. 1965, 12, 436–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miles, M.B.; Huberman, M. Qualitative Data Analysis: An Expanded Sourcebook, 2nd ed.; Sage: London, UK, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Strauss, A.; Corbin, J. Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Grant, R.M. Toward a knowledge-based view of the firm. Strateg. Manag. J. 1996, 18, 109–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nickerson, J.; Zenger, T. A knowledge-based theory of the firm: The problem-solving perspective. Organ. Sci. 2004, 15, 617–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, R.; Helfat, C.E. Strategic renewal of organizations. Organ. Sci. 2009, 20, 281–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).