2. Methods

Let

and

be two non-degenerate compact intervals on

, with

and

. The Cartesian product

defines a compact rectangle in

. A partition

of

R is a finite collection of non-overlapping sub-rectangles

such that

Each sub-rectangle

has the form

where the partitions of the intervals are given by

Thus, the rectangle

R is subdivided into

smaller rectangles, arranged so that adjacent subintervals align properly along both axes.

The lengths of the intervals are denoted by

with

. Clearly,

if and only if

, and

if and only if

. In such degenerate cases, the corresponding rectangle

R collapses to a line segment or a point in

. Otherwise, when both

and

are positive,

R has a nontrivial area

which represents the extent of the region covered in the plane.

Consider a rectangle

in

, and let

be a partition of

R, where each sub-rectangle is of the form

with

For each sub-rectangle

, we associate a point

, which is referred to as the

tag of

. Such a construction is called a tagged partition of

R, and is often represented as

We now define the mesh (or norm) of

is defined by

where

. This notion is used in the Riemann-style definitions that require uniformly fine partitions.

In other words, a tagged partition of R consists of ordered pairs , where forms a partition of R, and is the chosen tag of the corresponding sub-rectangle. It is clear that a given partition admits infinitely many possible tagged versions, since the tags can be chosen arbitrarily within each sub-rectangle.

We define the notion of the Riemann sum in the bivariate case, let

be a double sequence of functions defined on

, and let

be a tagged partition of

R. The corresponding Riemann sum is defined as

where

denotes the area of the sub-rectangle

.

Definition 1. Let be a compact rectangle. A double sequence of functions defined on R is said to be Riemann integrable over R with limit function g, if for all and for every there exists a number such that for any tagged partitionof R, withthe corresponding Riemann sum satisfieswhere The fundamental significance of the Riemann integral for a double sequence of functions defined on the rectangle lies in its interpretation as the limit of the associated double Riemann sums. As the tagged partitions of R become progressively finer in both variables, the corresponding sums converge in an appropriate manner to the integral value.

The key objective of this article is to move beyond the traditional Riemann framework for defining the limit of double Riemann sums associated with a sequence of functions. Instead, we adopt a generalized limit process, independently introduced by the Czech mathematician Kurzweil [

1] and the English mathematician Henstock [

1]. Although this approach is technically more involved than the classical Riemann procedure, it provides a broader and more versatile notion of integration. In particular, it significantly enlarges the class of integrable double sequences of functions defined on rectangles in

. Moreover, the method is more flexible and convenient, as it circumvents certain restrictive assumptions inherent in the Riemann theory. Thus, with only a modest increase in technical complexity, one obtains a powerful and refined integral concept, representing a noteworthy advancement in integration theory.

In the classical Riemann approach, the fineness of a partition of a rectangle

is determined by the mesh, defined as the maximum length of the subintervals in both directions. Accordingly, each sub-rectangle must have side lengths smaller than or equal to a prescribed tolerance. In contrast, the Kurzweil–Henstock methodology [

1] allows partitions with highly variable sub-rectangle sizes. In this framework, sub-rectangles in regions where the function exhibits rapid oscillations or steep gradients are chosen to be sufficiently small, while in regions of slower variation, larger sub-rectangles may be employed. This local adaptability makes the Kurzweil–Henstock integral particularly well-suited for double sequences of functions, providing a natural and refined approach to integration in two variables.

In 1957, the Czech mathematician Kurzweil [

1] introduced a new formulation of the integral that remained faithful to Riemann’s original framework. A few years later, in 1961, the English mathematician Henstock [

1] independently developed a similar construction, thereby extending the scope of the classical Riemann integral. Their contributions together gave rise to what is now known as the Henstock–Kurzweil (HK) integral [

1], a powerful generalization of the Riemann integral that has since played a significant role in modern integration theory.

In the case of functions of two variables defined over a rectangular domain

the Henstock–Kurzweil integral emphasizes the role of tags more prominently than the traditional Riemann framework. Specifically, for a tagged double partition

the fineness of the partition is not governed merely by the uniform length of subrectangles. Instead, each subrectangle is required to lie within a gauge neighborhood of its tag, namely

where

may vary from one tag to another.

This flexible control on partitions allows the HK integral in two variables (and hence for double sequences of functions) to integrate a far broader class of functions than the classical Riemann method, particularly those with local irregularities or oscillations.

We begin by introducing the following definitions:

Definition 2. Let be a compact rectangle. A mapping is called a gauge on R if, for every . For each , the gauge δ determines the neighborhoodwhich is referred to as the gauge interval centered at . In the setting of double sequences of functions, such gauge neighborhoods provide the essential mechanism for regulating the fineness of tagged double partitions of R. Definition 3. Let be a compact rectangle, and letdenotes a tagged partition of R, where each sub-rectangle is given by , and is its corresponding tag. If is a gauge on R, then the tagged partition is called -fine

if, for every pair of indices and , the sub-rectangle is contained within the gauge neighborhood In other words, each sub-rectangle must be entirely contained within the gauge interval determined by its tag .

In view of the above definitions we present an illustrative example below.

Example 1. Consider the rectangle .

Define a gauge function by

We partition into four equal sub-rectangles, The tags are chosen as the midpoints of each sub-rectangle, namely, Now, consider the sub-rectangle .

For the tag , we compute

Thus, the corresponding gauge interval is Since , the δ-fine condition holds for this sub-rectangle. A similar verification shows that the condition also holds for , , and .

Therefore, the tagged partitionis δ-fine. We now proceed to define the gauge integral (also known as the generalized Riemann integral) in the setting of a double sequence of functions defined on a rectangular domain of .

Consider a double sequence of functions

defined on the compact rectangle

. Let

denotes a tagged partition of

, where each

is a sub-rectangle of

and

serves as its tag.

If

is a gauge, then the tagged partition

is said to be

δ-fine whenever

The corresponding gauge sum of the double sequence

with respect to the tagged partition

is defined

where

denotes the area (Lebesgue measure) of the sub-rectangle

.

Definition 4. A double sequence of functions is said to be gauge integrable (or generalized Riemann integrable) over the compact rectangle if there exists a function such that for every there is a gauge defined on with the following property:

For any tagged partitionof that is -fine, the corresponding gauge sum satisfieswhereand denotes the area of the sub-rectangle . The following example illustrates the evaluation of the Kurzweil–Henstock (or gauge) integral of over with respect to a tagged partition .

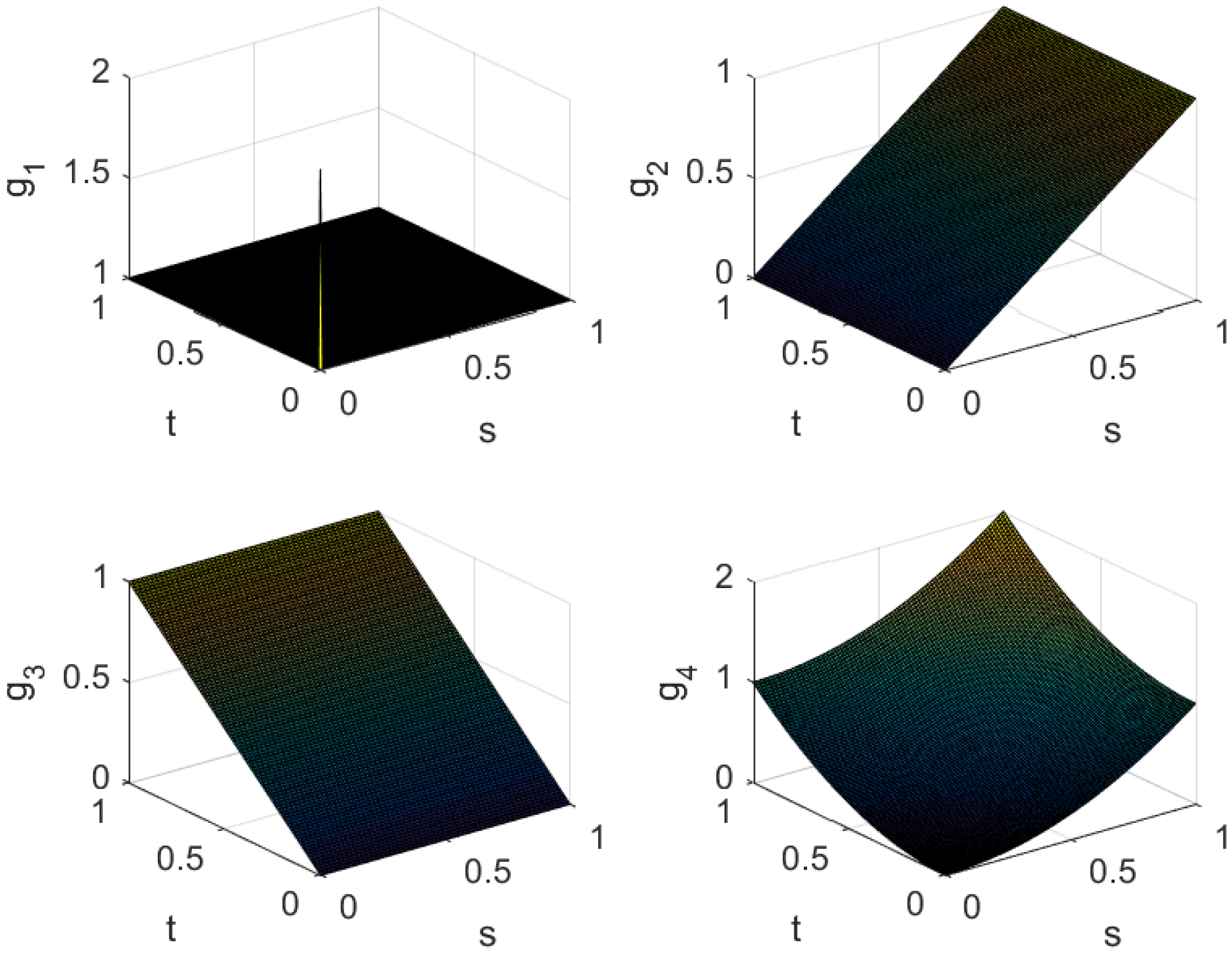

Example 2. Consider a double sequence of bivariate functions defined on the compact domain bywhere . The corresponding limit function of this double sequence is Each function represents a smooth oscillatory perturbation of the limit function, with the perturbation amplitude decreasing as .

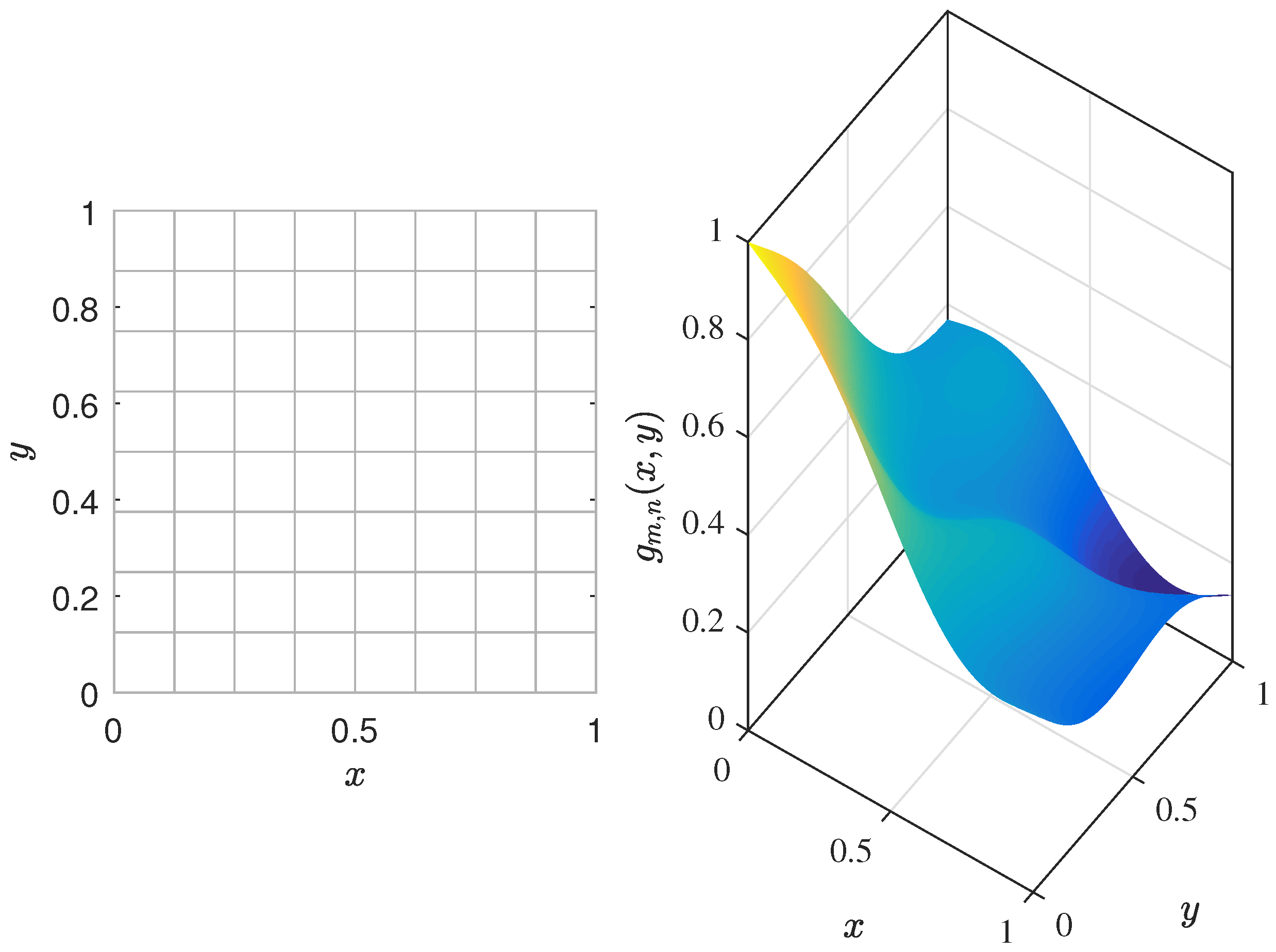

The gauge (or control) function , which determines the adaptive tagged partition of the domain, is defined byfor all . The gauge takes smaller values in regions of higher oscillation (for instance, near the center of the domain) and larger values in flatter regions. Consequently, the domain is subdivided into rectangles satisfying We denote the Kurzweil–Henstock (or gauge) double integral of byIt follows thatthat is, the double sequence of integrals converges uniformly to the exact integral of the limit function . Moreover, the double integral of the limit function over the unit square is given by In view of Example 2, we use MATLAB R2016b visualization (

Figure 1) to illustrate the geometric interpretation and convergence behavior of the gauge-tagged partition for

.

The left panel of

Figure 1 shows how the Kurzweil–Henstock (gauge) integral divides the domain

into smaller parts in an adaptive way. In regions where the function changes quickly or oscillates more, the rectangles automatically become smaller according to the gauge function

. The parameters

m and

n control how much the function oscillates and how smooth it is. Unlike the classical Riemann method, which uses subintervals of equal size, the gauge method allows variable sizes, making it more flexible for handling irregular functions while still achieving convergence. The right panel of

Figure 1 shows the function

for a specific pair

, helping to compare the function’s oscillations with the corresponding adaptive partition. Together, the two panels show that stronger oscillations lead to finer partitions, which is the main idea behind the Kurzweil–Henstock (gauge) approach.

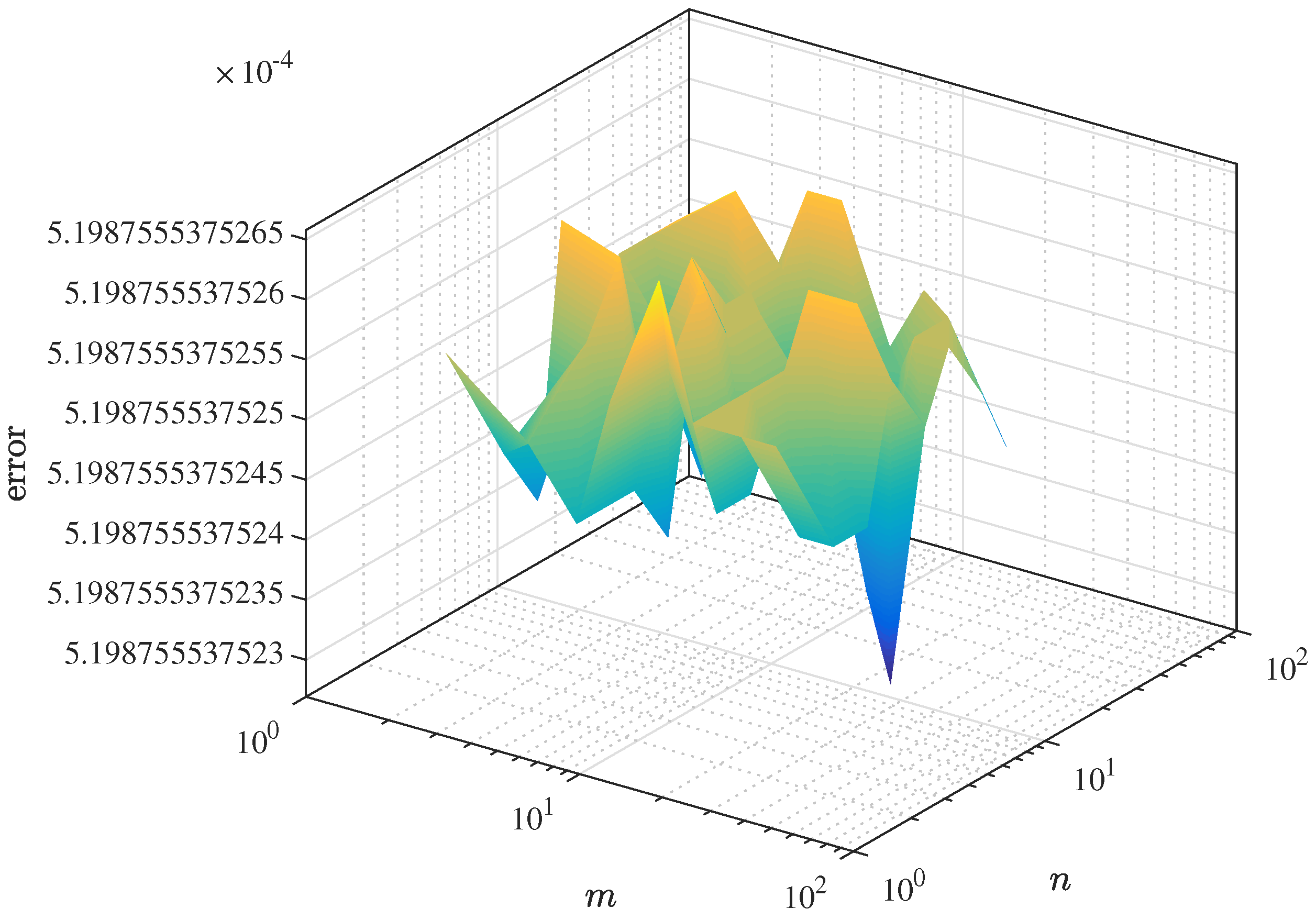

Figure 2 shows the surface plot of the absolute integration error

for different values of

m and

n. This

Figure 2 illustrates how the numerical results get closer to the exact value of the integral as both

m and

n increase. Here,

represents the numerical estimate of the two-dimensional Kurzweil–Henstock (gauge) integral for the function

, and

is the exact analytical value of the same integral.

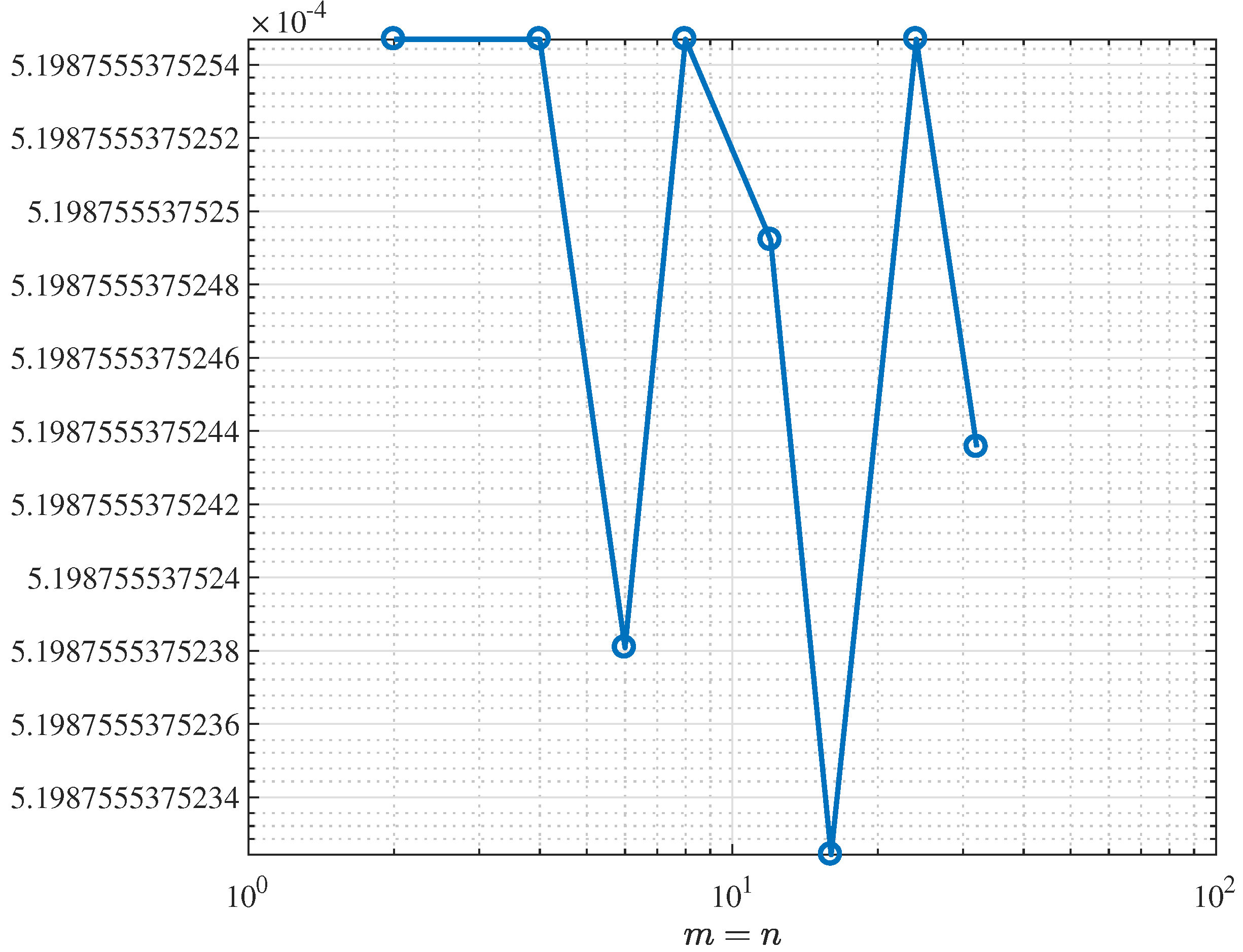

Figure 3 shows how the results converge when

m and

n are taken to be equal (that is,

). Both axes are shown on a logarithmic scale, so a straight line in the plot indicates a power-law rate of convergence. By focusing on the case

, the figure gives a simpler one-dimensional view of the convergence, instead of the full two-dimensional error surface. This makes it easier to estimate how fast the double sequence converges along its diagonal and to compare the observed numerical behavior with any available theoretical error bounds.

The classical theory of convergence forms the backbone of sequence space analysis, providing a rigorous foundation for approximation and summability methods. Building on this framework, Fast [

2] and Steinhaus [

3] independently introduced

statistical convergence, a powerful generalization of ordinary convergence that has since become an essential tool for both theoretical investigations and diverse applications.

In particular, the study of statistical convergence for double sequences of functions of two variables has developed into a powerful extension, offering a flexible framework for investigating approximation processes and summability methods. Its importance lies not only in its theoretical richness but also in its wide applicability across various branches of mathematics. In fact, it establishes strong links with engineering mathematics, computational mathematics, industrial mathematics, and financial mathematics, thereby underscoring its growing role in both theoretical research and real-world applications.

The vitality of this research area is further reflected in numerous recent contributions (see, for example, [

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12]), which demonstrate the depth and breadth of statistical convergence and its generalizations in the context of double sequences.

Definition 5. A double sequence is said to be statistically convergent to a limit α if, for every , the proportion of terms of the sequence that deviate from α by at least ϵ becomes negligible as both indices m and n tend to infinity. Equivalently, the set of index pairshas natural density zero. Formally, this condition is expressed asThus, if a double sequence is statistically convergent to α, we write In 2021, Srivastava et al. [

13] established a connection between statistically Riemann-integrable double sequences of functions, denoted

, and statistically limit-integrable sequences, denoted

, thereby proving Korovkin-type approximation theorems in this framework. This line of research was extended in 2022, when Srivastava et al. [

14] derived additional Korovkin-type results for deferred weighted statistically Riemann-integrable sequences.

Further developments include the work of Jena and Paikray [

15], who introduced a framework for statistical Riemann-Stieltjes integration and established several foundational results. Jena et al. [

16] subsequently examined statistical Riemann integrability and summability under deferred Cesàro means, while Parida et al. [

17] advanced the theory by studying deferred weighted statistically Riemann-summable sequences and formulating fuzzy Korovkin-type approximation theorems, thereby extending classical results to a broader and more flexible setting.

These contributions have inspired numerous generalizations, highlighting the richness of the subject. For further perspectives, one may consult [

16,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27], where various aspects of approximation theory, summability, and applications are explored in depth. Collectively, these works underscore both the historical development and the modern vitality of Korovkin-type results in diverse mathematical contexts.

In continuation of this line of research, we introduce two further notions for functions of two variables: statistically Riemann-integrable sequences, denoted , and statistically gauge-integrable sequences, denoted . The former provides a natural extension of the classical Riemann integral under statistical convergence in two dimensions, while the latter situates statistical integrability within the flexible Henstock–Kurzweil (gauge) framework. Together, these concepts extend classical integrability to the realm of double sequences, capture behaviors inaccessible to traditional approaches, and lay the groundwork for new Korovkin-type approximation theorems with broader applications in approximation theory and summability analysis.

Definition 6. Let be a double sequence of functions defined on the rectangle . We say that is statistically Riemann integrable (denoted by ) to a function g over if, for every and for all , there exists a number such that, for every tagged partition of with mesh size , the sethas natural density zero in . Formally, this meansIn this case, we denote the statistical Riemann integrability of by Definition 7. Let be a double sequence of functions defined on the rectangle . We say that is statistically gauge integrable (denoted by ) to a function g over if, for every , and for all there exists a gauge defined on such that, for every -fine tagged partitionof , the sethas natural density zero in . Formally, this condition is expressed asIn this case, the statistical gauge integrability of is denoted by The following theorem establishes a rigorous connection between the two concepts introduced above, namely statistical Riemann integrability and statistical gauge integrability, in the framework of double sequences of bivariate functions on the rectangle .

Theorem 1 (Connection between RIstat and GIstat). Let be a double sequence of real-valued functions defined on the rectangle , and let . Then the following hold:

- (a)

If is statistically Riemann integrable to , then it is also statistically gauge integrable to .

- (b)

Conversely, if is statistically gauge integrable to , and is classically Riemann integrable, then is statistically Riemann integrable to .

Proof. (a) Let

be given. By the definition of statistical Riemann integrability (

), there exists a mesh threshold

such that for any tagged partition

of

with mesh

, the Riemann sums

satisfy

for all

except possibly on a subset of

of natural density zero.

Now, define a constant gauge on

by

For any -fine tagged partition, the mesh is bounded above by , hence every -fine partition satisfies the same small-mesh condition required by .

Therefore, the Riemann estimate immediately extends to the corresponding gauge sums,

again for all

outside a subset of

of density zero. Moreover, the exceptional index set for the gauge integral is contained in the Riemann-exceptional set, which also has density zero. Hence,

is

whenever it is

.

(b) Conversely, assume that

is

with respect to the limit function

g. Then, for each

, there exists a gauge

such that for every

-fine tagged partition

of

,

for all

except possibly on a subset of density zero.

Since

is Riemann integrable on

, there exists

such that for any tagged partition

with mesh

, there is a

-fine refinement

satisfying

Using the triangle inequality, we obtain

The second term is controlled by the

property, and the first by the closeness of Riemann and gauge sums for fine enough partitions. Thus, the

condition is satisfied, establishing the equivalence between statistical Riemann and statistical gauge integrability. □

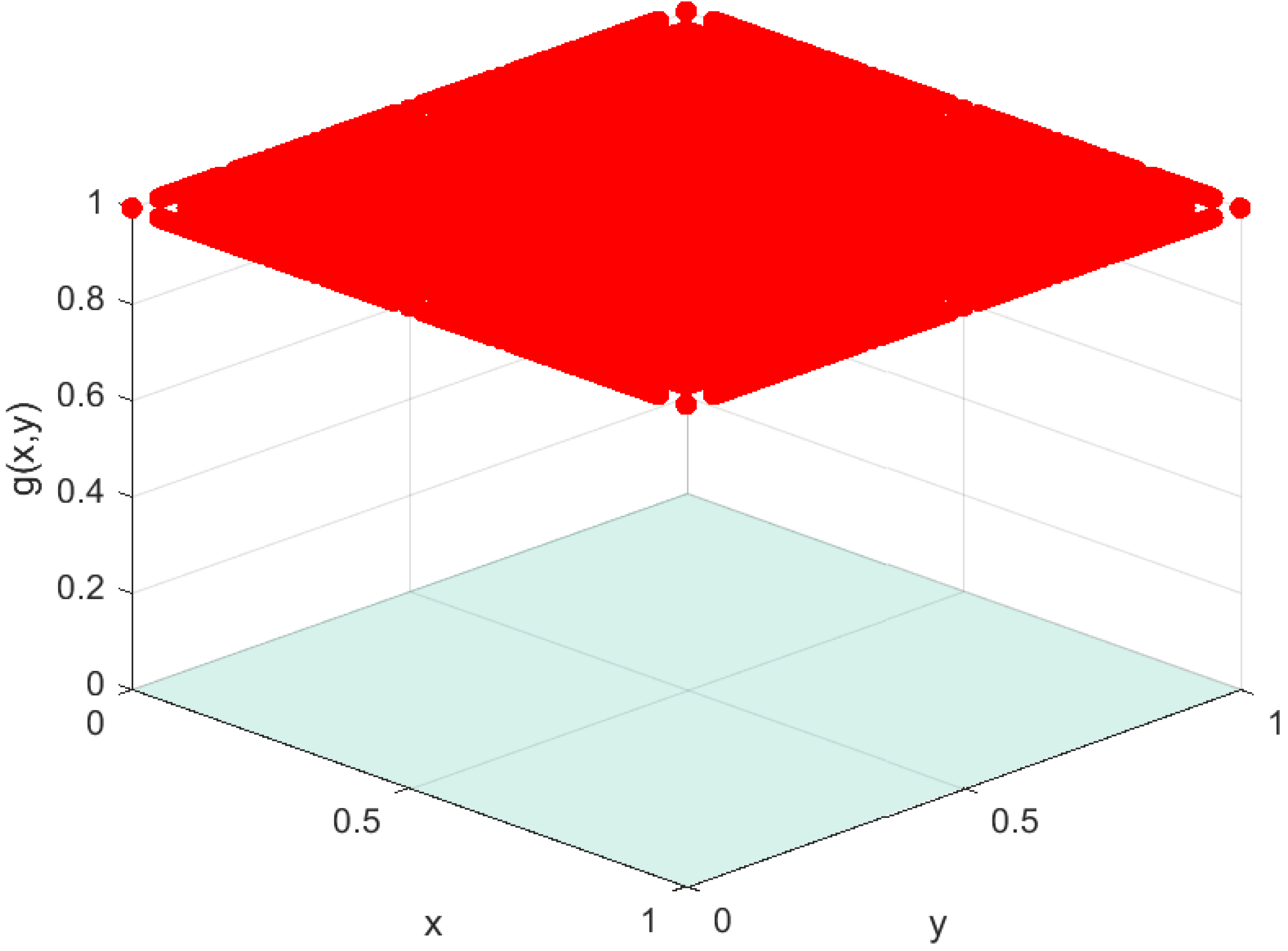

The following example demonstrates that, within the framework of double sequences of functions of two variables, the converse of Theorem 1 does not hold in general.

Example 3. Let . Define the functionwhere . Since the set of rational points has Lebesgue measure zero, it follows that g is Lebesgue integrable on R with . Consequently, g is Henstock–Kurzweil (gauge) integrable on R, and its gauge integral equals 0. On the other hand, g is discontinuous at every point of R (since every rectangle contains both rational and irrational points). Therefore, g is not Riemann integrable on R, as Riemann integrability requires the set of discontinuities to have measure zero.

For each , defineThus is the constant double sequence with each term equal to g. Since g is gauge integrable on R with integral 0, for every there exists a gauge on R such that every -fine tagged partition satisfiesFor the constant sequence the gauge sums coincide with for every . Hence, for this and for every -fine partition the exceptional index setis empty, and therefore has natural density zero. This confirms that Take . For any mesh threshold , tagged partitions with all tags chosen from rational points, and similarly, there exist γ-fine partitions with all tags chosen from irrational points. For a partition consisting solely of rational tags, the corresponding Riemann sum satisfies , whereas for a partition consisting solely of irrational tags, we obtain . Thus, no single number L can serve as a Riemann limit approximating all γ-fine Riemann sums simultaneously.

In particular, for the constant sequence and the chosen ϵ, there exist γ-fine partitions for which the exceptional index setcoincides with the whole of (and hence of density 1) for every putative limit L. Therefore, the sequence does not satisfy the condition. This example demonstrates that a double sequence may be statistically gauge integrable to a function g (in this case with gauge integral equal to 0) while failing to be statistically Riemann integrable. Thus, the converse implication in Theorem 1 does not hold, in general, without additional assumptions, such as the classical Riemann integrability of g.

To gain further insight into Example 3, Figure 4 presents a three-dimensional visualization of . Its significance may be interpreted as follows: - (i)

Red Scatter Points (): The red points represent the rational points with denominators bounded by a fixed constant. At these points, the function value is . Since the rationals are dense in , these red points appear throughout the square, even though they form only a countable set.

- (ii)

Transparent Blue/Gray Plane (): The surface at height zero corresponds to all irrational points. At these points, the function is defined as . Since the irrationals are uncountable and dense in , this plane dominates the region, showing that the function is “almost everywhere zero.”

- (iii)

Overall Interpretation: The juxtaposition of isolated red points above a continuous plane at highlights the dual nature of the function. The density of rationals causes the red points to scatter across the entire region, but their measure is zero. Thus, the integral is governed entirely by the blue/gray plane at . This provides a visual explanation of why the function is not Riemann integrable in the classical sense, yet can be treated effectively within the gauge or statistical integration frameworks.

Motivated by the above body of work and the recent developments in this area, we aim to broaden the scope of analysis by investigating the notions of gauge integrability and gauge summability within the statistical framework for double sequences of functions. In particular, we incorporate deferred weighted summability methods, which allow for a more flexible treatment of convergence phenomena. Our first goal is to formulate and prove a collection of fundamental limit theorems that reveal intrinsic connections between these enriched concepts of summability and integrability. Building upon this foundation, we then establish Korovkin-type approximation theorems for functions of two variables with respect to the standard test functions 1, s, t, and . To demonstrate the practical significance of these abstract results, we conclude by presenting an illustrative example involving a family of positive linear operators associated with the well-known Meyer-König and Zeller operators, thereby underscoring the effectiveness and applicability of our proposed theoretical framework in approximation theory.

Gauge Integrability via Deferred Weighted Mean

Let

,

,

,

be sequences in

such that

Suppose

is a double sequence of nonnegative weights and define the cumulative weight

with

sufficiently large

.

Let

be a double sequence of functions on a rectangle

and let

be a tagged partition of

R. The deferred weighted gauge mean of the gauge sums

over the delayed index rectangle

is defined by

Here denotes the gauge sum of the function with respect to the tagged partition , and represents the deferred weighted average of these gauge sums over the index window . The weight under double-sum allows flexible emphasis on particular indices and naturally extends single-index deferred weighted means to the double-sequence setting.

We now proceed to introduce the notions of statistical gauge integrability and statistical gauge summability for double sequences of functions in two variables. These concepts are developed within the framework of deferred weighted summability means, thereby providing a refined extension of classical integrability and summability techniques to the statistical setting. This formulation not only generalizes existing approaches but also establishes a versatile foundation for the study of approximation processes in the context of functions of two variables.

Definition 8. Let , , , and be sequences in satisfying and . Consider also a double sequence inA double sequence of functions is said to be statistically deferred weighted gauge integrable () to a function over the rectangle if, for every , there exists a corresponding gauge such that for any -fine tagged partitionof , the exceptional index sethas double natural density zero. Equivalently, for each ,In this case, we write Definition 9. Let , , , and be sequences in satisfying and . Further, let be a double sequence in A double sequence of functions is said to be statistically deferred weighted gauge summable (denoted ) to a function over the rectangle if, for every , one can find a gauge such that, for any -fine tagged partitionof , the exceptional sethas natural double density zero. Equivalently, for each ,In this case, we write We now turn to an inclusion theorem that reveals the intrinsic connection between the two recently introduced notions: statistical deferred weighted integrability and statistical deferred weighted gauge summability, both considered in the setting of double sequences. This result not only clarifies the interplay between these concepts but also emphasizes their potential relevance within the broader framework of approximation theory.

Theorem 2. Let be a double sequence of real-valued functions on the rectangle . Suppose is a double sequence of nonnegative weights and, for each , for all sufficiently large . ThenThat is, if is statistically deferred weighted gauge integrable to a limit function on R, then the deferred weighted gauge means of the gauge sums converge statistically to the same limit function on R. In general, however, the converse implication does not hold. Proof. Assume

is

-integrable to

on

R. Fix

. By the definition of

-integrability there exists a gauge

and an associated

-fine tagged partition

of

R such that the exceptional index set

has deferred weighted double density tending to zero. In other words, for sufficiently large

the proportion of indices in

measured with respect to the total weight, becomes negligible, i.e.,

For the same partition

, define the deferred weighted gauge mean (see (

3)) by

Splitting the double sum into the contribution from the exceptional set

and from its complement, we obtain

By construction, if

then

in the weighted formulation. However, a simpler uniform estimate follows directly from integrability. Since each

is finite and

g is fixed, there exists a global finite bound

M such that

for all relevant

. Hence, we obtain

Moreover, the contribution of the exceptional set is controlled by the definition of

. For large

,

where

C is a fixed constant, for instance

. Consequently, since the weighted density of

tends to zero, the right-hand side also vanishes as

.

Combining the two estimates, let

be arbitrary. Choose

and take

sufficiently large so that the weighted contribution of the exceptional set

is less than

. The remaining summands (on the complement) are uniformly close to

g in the deferred weighted sense by integrability, and therefore their weighted average is also arbitrarily close to

g. Consequently,

in the statistical deferred weighted sense. Hence,

is

-summable to

. This proves the first implication. □

We now present a concrete example which disproves the converse, by showing that -summability can hold while -integrability fails.

Example 4. Let and fix the functionthe indicator of rational grid points in R. As noted earlier, the gauge sums for h can take values close to 0 or 1, depending on the choice of tags. Consequently, h fails to be Riemann integrable. However, it is gauge integrable with integral equal to 0, even though the corresponding gauge sums can fluctuate between 0 and 1 for different tagged partitions. Now, define a double sequence of functions on R bywhere the index set will be specified below. Next, assign weights by If has positive natural density (e.g., , with density ), then the set of indices where the integrand equals h also has positive density, so pointwise or gauge behavior on such a density-positive set precludes -integrability, as the exceptional set contributes many indices with large gauge-sum deviations.

For the deferred window setSince outside S and inside S, the total weight contributed by indices in is uniformly bounded (geometric tails), whereas the weight from indices outside S grows like . Consequently,while the complementary contribution dominates . Thus the deferred weighted gauge meanis governed essentially by indices outside S, where and hence . Therefore, as , with convergence stable in the deferred statistical sense. It follows that is -summable to the zero function. On the other hand, since S has positive (unweighted) natural density and the members of S carry the function h, whose gauge sums fail to approximate 0 uniformly across tags, the condition for -integrability fails. The exceptional set of indices, where the gauge sums deviate from 0 by a fixed positive amount, does not have double natural density zero. Hence, is not -integrable.

The above construction shows that -summability does not imply -integrability. Hence, the converse of Theorem 2 fails in general.